Debra Higgs Strickland • University of Glasgow

Recommended citation: Debra Higgs Strickland, “Introduction: The Future is Necessarily Monstrous,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010). https://doi.org/10.61302/FUST8967.

The future is necessarily monstrous: the figure of the future, that is, that which can only be surprising, that for which we are not prepared, you see, is heralded by species of monsters. . . .All experience open to the future is prepared or prepares itself to welcome the monstrous arrivant . . . This is the movement of culture.[1]

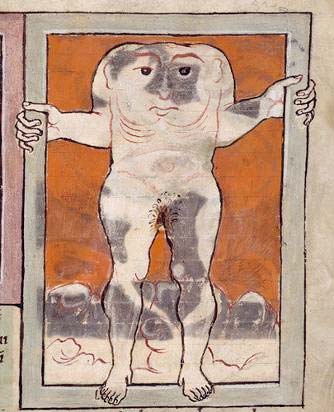

Fig. 1. Blemmye, The Wonders of the East, London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v., fol. 82r (detail) (© the British Library Board)

In May 1990, Jacques Derrida commented about culture and monstrosity during an interview in which he also observed that once we identify and attempt to explain a monster, we begin to domesticate it, which in turn forces us to change our own habits. This is the “movement of culture” to which he refers in the quotation above. With this view of monstrosity as an inevitable and perpetual process of grappling with the alien and the unknown, the Middle Ages is an especially good place to investigate its visual and verbal manifestations. It is not surprising that four of the six studies in the present collection (Kim and Mittman, Mittman and Kim, Oswald, Saunders) interrogate monstrosity in Anglo-Saxon England, a monstrous breeding ground from which sprang, among others, Beowulf, Saint Guthlac’s demons, the fallen Lucifer, the monsters described in the Liber monstrorum (Book of Monsters), and the Wonders of the East.[2] A fifth study (Strickland) shifts the monstrous focus to later medieval Germany and the tale of Herzog Ernst, and the final one (Lewis) examines diverse early medieval representations of the ultimate monster, Antichrist. From the talking serpent in the Garden of Eden to Antichrist at the end of time, the medieval world was paved with monsters. And so we aim to analyse a privileged few of them in order to continue—or in some cases, begin—their modern domestication.

This collection of essays was inspired by a series of sessions on monstrosity organized by Asa Mittman for the International Medieval Congress held at the University of Leeds in July 2008. The thematic strand that year was ‘The Natural World,’ and so these sessions were advertised under the antithetical rubric of ‘The Unnatural World.’ Three of the present studies grew from papers delivered during these sessions, and the other three were invited to complement and expand some of their major themes. Of our respective selections of medieval texts and images, we first ask, what makes them monstrous? Second, we ask more broadly, what cultural purposes did their monstrosity serve? We recognize medieval manuscripts and incunabula as especially rich cultural vehicles for the application of the range of art historical and literary critical approaches that we employ in our respective analyses. We further acknowledge that words and pictures are equal bearers of monstrosity. I would argue, however, that even contemporary literature bears witness to the fact that monstrosity is first apprehended by sight: you know a monster when you see the whites of his eyes (or eye), whether raging in the fen or painted or printed on the page of a book. It is the monster’s emphatically visual identity that always justifies analysis from the perspective of visual culture, a principle that makes the first question posed above the easier one to address.

The second question, about the cultural functions of monstrosity, is more difficult to address, but it is a difficulty aided by the application of critical theory. We draw upon insights from a variety of medieval and modern critics in order to provide the broadest possible understanding of monstrosity’s multiple meanings. The work of certain critics, such as Julia Kristeva, Jacques Derrida, and Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, run as a leitmotif across these studies—but so do Augustine’s City of God and the Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Perhaps more so in the monstrous than in other realms, medieval and modern concerns frequently converge. For example, the perceived link between inner moral corruption and external physical appearance is demonstrated as strongly in current cinema as it is in thirteenth-century Passion imagery.[3]

David Williams and Bruno Roy, among others, have constructed taxonomies of monstrosity, a goal shared by medieval theologians and bestiarists.[4]

Then as now, attempts at monstrous taxonomies are deeply problematic given that a key aspect of a monster, as the present studies demonstrate, is its resistance to classification and its ultimate refusal to be categorized. Suzanne Lewis’s analysis of early medieval Antichrist imagery highlights this problem in relation to demons and biblical monsters that simultaneously embody bestial and human forms, and more troubling still, changing forms. We might also remember creatures, such as the basilisk, that confounded the bestiarists (bird? beast? reptile?). Even a type of monster apparently defined by gender, such as the Bearded Woman, is not without classification problems: Dana Oswald has asked us to consider, for example, how an exclusively female race who live remotely and receive no male visitors can possibly reproduce themselves. Even more difficult to deconstruct are those monsters defined by their text descriptions as one sex but whose behavior more strongly resembles the other; and whose artistic portraits are concomitantly highly ambiguous, such as the Wonders Huntresses (analyzed by Oswald) and the seemingly hospitable Donestre (examined by Rosalyn Saunders).

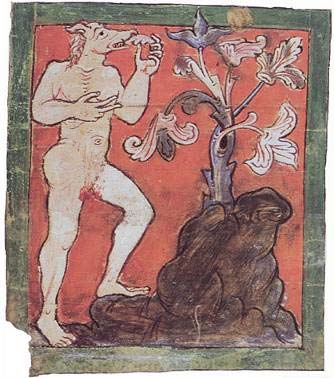

This last observation highlights the strong connections between monstrosity, the body, and gender that are well recognized in the current literature.[5] In the present collection, both Lewis and Saunders observe how nudity operates as a prominent sign of monstrosity in texts and images concerned with Antichrist and the Donestre, respectively. In the medieval world, monstrous genitalia are especially problematic, whether the carefully rendered female genitals of the headless Tiberius Blemmye (Figure 1),[6] or the gigantic phallic hat that the Morgan Beatus Antichrist wears. The Tiberius Donestre’s bright red penis similarly does not inspire comfort, but then, it is difficult to find anything comforting about a beast-headed speaker of all languages who routinely devours (except for their heads) the new acquaintances with whom it has just bonded socially. Embodied and presented by the monster, sexuality is both deviant and dangerous (Figure 2). Equally, for medieval Christians, hypersexuality rendered ordinary humans monstrous.

Beyond its application to particular types of hybrid beings, some critics have defined monstrosity temporally, as a theoretical concept applicable to the entire period of the Middle Ages, by asking us to confront directly the alien aspects of these ten centuries redolent with customs and concepts so at odds with modern-day sensibilities. Pithily expressed as “the monstrous Middle Ages,” such a project shifts scholarly attention from understanding to explaining.[7] The conviction that underlies this position is that there is little to be gained intellectually by normalizing or reshaping the Middle Ages into modern recognition. As Caroline Walker Bynum urged near the end of her seminal discussion of medieval ‘wonder’:

Not only as scholars, then, but also as teachers, we must astonish and be astonished. The flat, generalizing, presentist view of the past encapsulates it and makes it boring, whereas amazement yearns toward an understanding, a significance, that is always just a little beyond both our theories and our fears.[8]

Our goal in the present collection is to continue this type of cultural work: by explaining the monsters, we hope to come closer to understanding the societies that produced them, recalling Derrida as well as Jeffrey Cohen’s oft-quoted observation that “The monster is pure culture.”[9] But we do not expect to arrive at a complete understanding.

Because all of us are art or literary historians concerned with text-image relationships, it is appropriate to say something about the objects of our study and how they serve another important analytical trend of the past decade. Michael Camille’s call, in 1996, to ‘rethink the canon’ was not coincidentally linked to his own interests in medieval monsters. Camille saw monsters, with their contingencies and radical corporeality, their evocations of “pure sensation,” as rich potential replacements for what he saw as the comparatively antiseptic, disembodied mostly museum-bound objects that had for too long exclusively populated the conventional canon of great medieval works of art.[10] In this collection, in the footsteps of Camille, we embrace artistic anonymity when and as necessary and we identify with reader-viewers. We most definitely sidestep the canon. The drawn, painted, and printed book-images that we examine from our different theoretical perspectives are modestly and imperfectly rendered, small, multiple, and iconographically obscure. The Devil riding Behemoth, Two-Headed Snakes, Tusked Woman, Donestre, Crane Men, and above all, the Burning Hens, are unlikely to appear on Art History undergraduate lists of major monuments for memorization. And yet we do remember them because, as monsters, they show us things. In his 1990 interview, Derrida also observed,

A monster is always alive, let us not forget. Monsters are living beings. A monster is a species for which we do not have a name, which does not mean that the species is abnormal, namely the composition of hybridization of already known species. Simply, it shows itself [elle se montre] —that is what the word monster means—it shows itself in something that is not yet shown and that therefore looks like a hallucination, it strikes the eye, it frightens precisely because no anticipation had prepared one to identify this figure.[11]

Camille put it more precisely: “the monster, being unstable, crosses boundaries between human and nonhuman, mingling the appropriate and the inappropriate, showing itself in constantly novel and unexpected ways.”[12] All of the studies collected here show monsters in action, pointing the way to something, even if that something is a terrifying void. The monsters of Herzog Ernst point to the Western court; the Donestre points to gender ambiguity. The Huntresses and Tusked Women point to anxieties surrounding maternity, and most ominously, Antichrist points to the end of everything. The monsters of the Beowulf manuscript point to themselves.

Fig. 2. Cynocephalus, The Wonders of the East, London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v.,fol. 80r (detail) (© the British Library Board)

Together, our studies identify medieval monsters from Grendel to Antichrist as elusive, renegade, changeable, terrifying, attractive, escape artists. Analytically, three main themes emerge. To cop the now classic, enumerative format pioneered by Jeffrey Cohen in “Monster Culture (Seven Theses),”[13] I list these one-by-one below.

Theme 1. Monstrosity is contingent. It needs a social context, a cultural milieu, a value system, or a belief system against which, and within which, it may be perceived as aberrant. It is therefore seemingly ironic that the consistent ideological pattern among medieval Christians was to locate monstrosity ‘Elsewhere.’ Temporally, this could be the distant past or far into the future; geographically, the exotic East or the far North, however vaguely defined. In relation to the Wonders of the East and its multiple frames, Asa Mittman and Susan Kim unpack the technical specificity of the place names and locational distances, precisely enumerated, that apparently enable the would-be traveller to visit, say, the colony of giant sheep (just 115 leagues from Babylonia) in order to explain how such precision in fact dislocates the monsters. The land of Bavaria in Herzog Ernst, by contrast, is ‘Here,’ and yet what happens when the monsters arrive, I argue, overturns the very social conventions that gave rise to medieval monster tales. However, as noted, the concept of Elsewhere is not necessarily a geographical designation; as Lewis argues, it is also a temporal one, as signified by eschatological monstrosity. Where medieval monsters live, or when they materialize; how they look and what they do consistently violate cultural rules according to the particular parameters embraced by the author or artist. Even when the Donestre obligingly adopts Western social conventions—in other words, follows the cultural rules—, as Saunders demonstrates, the effect is disrupted utterly by conformity’s wicked end-goal. A further contingency is created by text and image: when medieval artists and authors did not operate in tandem, competing interpretations created additional ruptures. It is often the case in monstrous presentations that images do not always corroborate texts, or that texts are incomplete, missing entirely, or internally inconsistent. Our four Anglo-Saxon studies also show that monstrosity was expressed linguistically, that the very languages of Old English and Latin could be manipulated to create their own monstrous spaces.

Theme 2. Monstrosity resides in both presence and absence. Or, to put it another way, medieval monstrosity could be positive or negative. Positive monstrosity directly evokes the physical presence of the monster; it puts the creature before the reader-viewer eyes or mind’s eye, either visually on the page, or verbally in imaginative literature. Negative monstrosity, as understood from Lewis’s study, denies the reader-viewer a full sensory experience through incomplete or completely ‘missing’ iconography. In this form of expression, the artist omits something that signifies—and terrifies—by its absence. As Kim and Mittman identify, the horror of the not-there can be expressed through manipulation of the seemingly innocuous feature of the frame, which, far from mere decoration, operates in the Wonders section of the Beowulf Manuscript in emphatically expressive ways that shape perceptions of the monster it isolates— or fails to. In their second study of the ungefrægelicu (“unheard-of”), these two authors also explain how both rhetoric and rhetorical absence in the Wonders Old English and Latin texts can heighten the experience of the grotesque while also problematizing its ‘truth value.’

Theme 3. Monstrosity is defiant. This is arguably its most fundamental characteristic. From classification to physical integrity (Lewis) to gender roles (Oswald, Saunders); from location and control (Mittman and Kim) to contemporary literary conventions (Strickland), monsters defy everything, and everything about them is mutable, from their appearances to their very names. Based on their analysis of the Wonders of the East text and images, Kim and Mittman put it most succinctly: monsters are inconceivable. In these six studies, we have nevertheless tried to conceive of just a few, and thereby to domesticate them. In the discussion of the last of his seven theses, Jeffrey Cohen warns that monsters always return,[14] and so we all look forward to a necessarily monstrous future.

References

| ↑1 | Jacques Derrida, “Passages—from Traumatism to Promise,” in Points …: Interviews, 1974-1994, ed. Elisabeth Weber, trans. Peggy Kamuf, et al. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1995), 386-87. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503622425 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England (New York: Routledge, 2006). |

| ↑3 | This problem has been addressed recently by Madeline Caviness, “From the Invention of the Whiteman in the Thirteenth Century to The Good, the Bad, the Ugly,” Different Visions 1 (2008): 1-32. https://doi.org/10.61302/YOTW3684 |

| ↑4 | Bruno Roy, “En marge du monde connu: les races de monstres,” in Aspects de la marginalité au Moyen Age, ed. Guy-H. Allard (Montreal: L’Aurore, 1975), 70-81; David Williams, Deformed Discourse: the Function of the Monster in Mediaeval Thought and Literature (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), 107-76. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780773565883 |

| ↑5 | See especially Caroline Walker Bynum, “Why All the Fuss about the Body? A Medievalist’s Perspective,” Critical Inquiry 22 (1995): 1-33; Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, On Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999); and Suzanne Lewis, “Medieval Bodies Then and Now: Negotiating Problems of Ambivalence and Paradox,” in Naked Before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Benjamin C. Withers and Jonathan Wilcox (Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press, 2003), 15-28. |

| ↑6 | As discussed by Asa Simon Mittman and Susan M. Kim,“The Exposed Body and the Gendered Blemmye: Reading the Wonders of the East,” in Fundamentals Of Medieval And Early Modern Culture, vol. 3, The History of Sexuality in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, ed. Albrecht Classen and Marilyn Sandidge (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2008), 171-215. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110209402.171 |

| ↑7 | Paul Freedman and Gabrielle M. Spiegel, “Medievalisms Old and New: The Rediscovery of Alterity in North American Medieval Studies,” American Historical Review 103 (1998): 677-704. See also Bettina Bildhauer and Robert Mills, “Introduction: Conceptualizing the Monstrous,” in The Monstrous Middle Ages, ed. Bettina Bildhauer and Robert Mills (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2003), 1-27. |

| ↑8 | Caroline Walker Bynum, “Wonder,” American Historical Review 102 (1997): 26. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171264 |

| ↑9 | Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture: Seven Theses,” in Monster Theory: Reading Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 4. |

| ↑10 | Michael Camille, “Prophets, Canons, and Promising Monsters,” Art Bulletin 78 (1996): 198-201. https://doi.org/10.2307/3046172 |

| ↑11 | Derrida, “Passages,” 386-87. |

| ↑12 | Camille, “Prophets, Canons,” 200. On the medieval understanding of “monster” in relation to monstrare (to show), but also monere (to warn), see Asa Simon Mittman and Susan M. Kim, “Monsters and the Exotic in Early Medieval England,” Literature Compass 6 (2009): 6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4113.2008.00606.x |

| ↑13 | As in n. 9, above. |

| ↑14 | Cohen, “Monster Culture,” 20. |