Selena Anders • University of Notre Dame

Recommended citation: Selena Anders, “Housing the Butcher, the Baker, and the Candlestick Maker: The Cultural Significance of Residential Façade Porticoes in Medieval Rome,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 23 (2023). https://doi.org/10.61302/ZJRO1603.

Many of Rome’s working-class once lived and labored in a house identifiable by an architectural element that has almost completely vanished from the city’s residential fabric—the façade portico. A portico is a structure supported by columns distributed at regular intervals across the surface of a building. In this paper, a portico refers to a covered open space on the ground floor of a structure supported by columns along a building’s façade that fronts a public street. Those facing the courtyard and situated on the upper levels of a building will be referred to as loggias, following the lexicon used to refer to these architectural elements in Roman property archives produced from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century.[1] This study briefly outlines the emergence of porticoed forms in medieval Italy and their particular use in working-class housing. It touches upon the perceived societal benefits and concerns associated with this porous element that served as an intermediate space between the public and private realms. By drawing these structures and mapping their locations, this study contributes to a better understanding of the architecture and urban character of the Eternal City in the Middle Ages. It reveals the semi-hidden remnants of medieval Rome’s domestic structures still present today.

It is not well known that residential façade porticoes were once an essential part of Rome’s medieval urban landscape. The distinct architectural feature immediately conjures images of Italian cities such as Bologna and Padua, where many of these buildings have been preserved to the present day. From the eleventh to the fifteenth century, porticoes were part of the daily life of merchants in the center of Rome as they were in countless others throughout Europe.[2] They served as a privileged place of mercantile activity and, as such, were a preferred building type of the era. They framed the socio-political values of the period ascribed to the concept of work at all levels of society, from the civic to the domestic realm.[3] They served as the threshold where public and private spheres interacted.[4]

The existing remnants of medieval façade porticoes identified in this study owe their longevity to the penchant for frugality employed in Rome’s building industry. As a result of centuries of thriftiness, many of Rome’s medieval residential façade porticoes continue to exist today, albeit immured, serving as the foundation for buildings that have been enlarged or constructed in later periods. Recent archaeological discoveries have revealed that medieval porticoes have secretly resided for centuries behind the façade of famous buildings such as Palazzo Farnese and Palazzo Alberteschi, to name a few. Both are situated less than a mile apart on the western side of the street, along the present-day Piazza Farnese, and Via Capo di Ferro.[5] The thoroughfare also includes the medieval cluster of thirteenth-century houses referred to as the Case di S. Paolo (Via di S. Paolo alla Regola and Via di Santa Maria in Monticelli) documented in this study. Saint Bridget of Sweden’s home (Via di Monserrato), where the saint is known to have lived from 1354-1373, was also located on this street and was noted as having a portico.[6] The house was situated at the present location of the Casa di Santa Brigida on the corner of Piazza Farnese but was rebuilt over the following centuries. Together these buildings paint a picture of a lively commercial street in the heart of Rome, where porticoes were a recurring architectural feature from the Ponte S. Angelo to Tiber Island. Anna Modigliani’s studies of Rome’s markets, shops, and commercial spaces from the late Middle Ages to the modern era provide further evidence that this area was home to many merchants and artisans.[7] These members of Rome’s working class are noted in archival sources as often renting or owning two-storied buildings with shops on the ground floor fronted by a portico with living spaces above (casa-bottega/house-shop). They once served as retail space for a broad spectrum of commercial activities. They were occupied by cobblers, spice merchants, butchers, barbers, bakers, textile vendors, and apothecaries, to name a few.

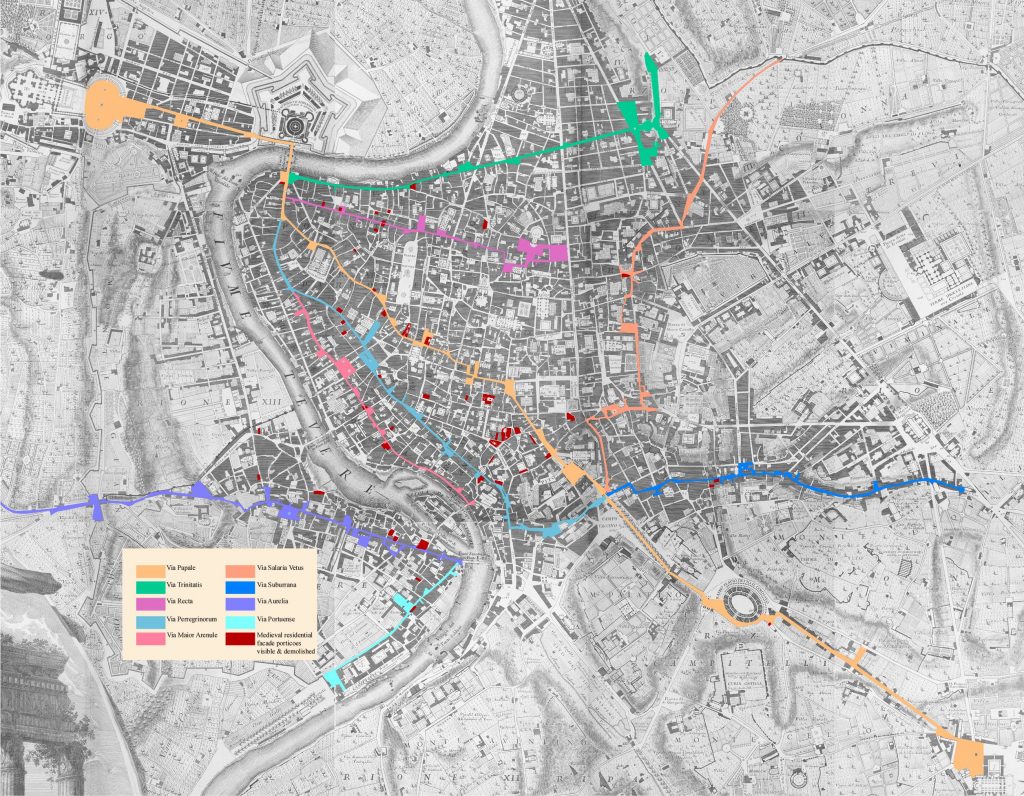

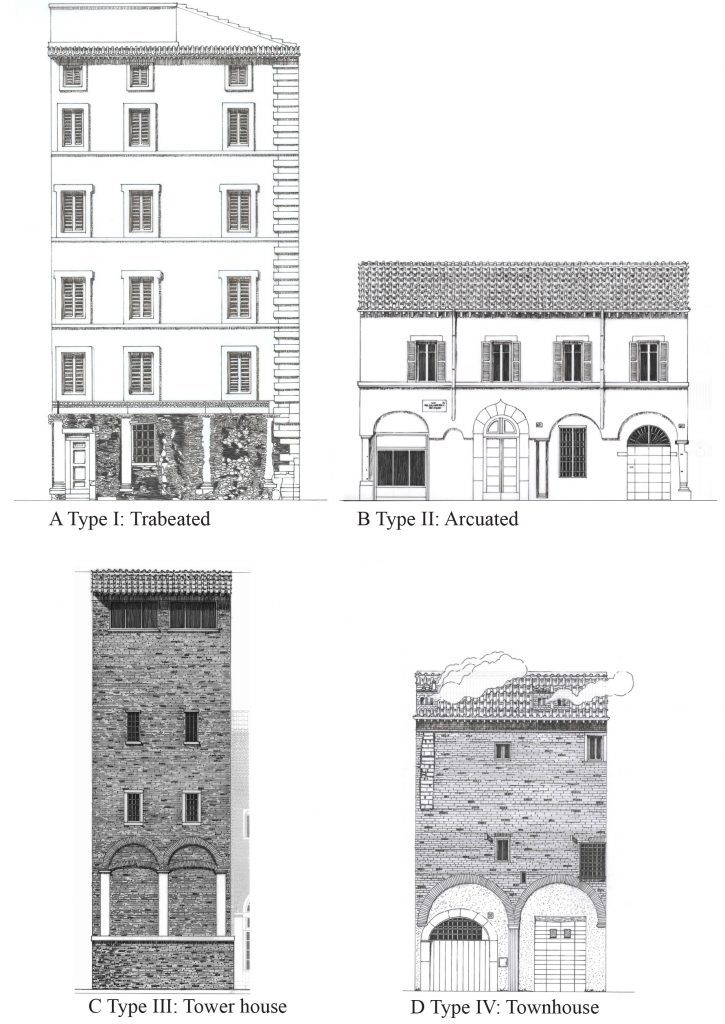

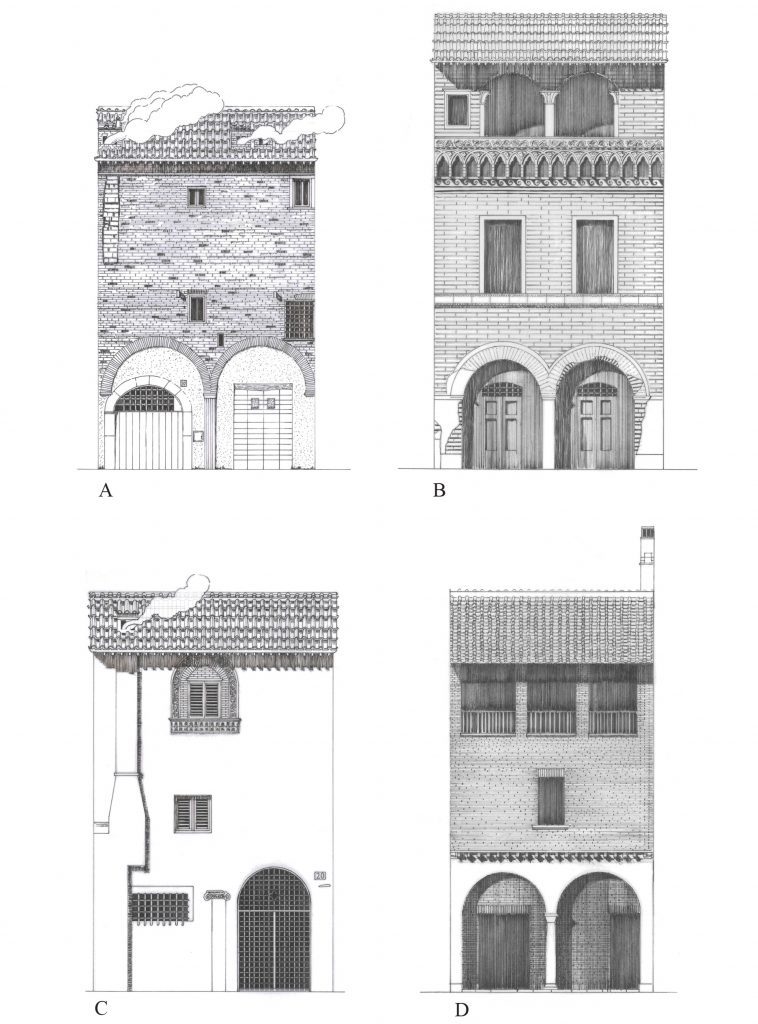

By identifying a distinct type and character of medieval buildings, such as the residential façade portico, and mapping their distribution throughout the city, this study contributes to a better understanding of the commercial character of medieval Rome,[8] which once housed the city’s working class, nobility, and even local saints.[9] I have identified fifty-six extant medieval residential porticoes within the Aurelian walls in eleven of the city’s fourteen historic rioni (districts) (Fig. 1).[10] Moreover, I have compiled a list of forty-five discussed in recent scholarship and archeological reports, along with those I have identified in archival sources, historic city plans, and vedute (views).[11] Furthermore, I discuss the four distinct subtypes of residential porticoes present in Rome, which are referred to here as 1. Trabeated 2. Arcuated 3. Tower House, and 4. Townhouse (Fig. 2). When examining the building materials employed in these structures, the reuse of ancient spolia (spoils) reworked by medieval masons and stone carvers appears to have been quite systematized. Construction patterns also emerged, revealing a medieval building culture common to residential, religious, and civic structures. Large quantities of ancient Roman materials such as grey and red granite single shaft columns, large blocks of white marble used for architraves, capitals, and column bases, and various types of marble appear to have been available locally and commonly reused by local craftspeople for their patrons. Skilled stone carvers executed the Ionic capitals employed in these buildings in multiple ways that attempted to communicate the ancient and late antique precedent from which they were taking inspiration. The Ionic capital in medieval Rome was prevalent in residential architecture and the primary one utilized by stone carvers and masons building religious structures throughout the period (Fig. 3). This tradition appears to have started in late antiquity and endured throughout the Middle Ages.

Fig. 1. Ancient and medieval street networks with residential façade porticoes both visible and demolished in red. (author’s notes above Giovanni Battista Nolli’s, Nuova Pianta di Roma, 1748. Image of Nolli Plan: Architecture Library, University of Notre Dame).

Fig. 2. Four distinct types of residential façade porticoes in Rome (author’s drawings). A Type I: Trabeated, Via Capo di Ferro, 31. B. Type II: Arcuated, Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69. C Type III: Tower House, Case di San Paolo, at Via di S. Paolo alla Regola and Via di S. Maria in Monticelli. D. Type IV: Townhouse, Via Arco della Pace, 10.

Fig. 3. Examples of Ionic capitals identified in this study (author’s drawings).

Porticoed Streets in Rome from Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages

According to Hendrik Dey, the proliferation of porticoed streets and piazzas of the Communal Age in Italy represented the continuity of the late antique plateae (streets). These broad thoroughfares served as politically and symbolically charged centers that were also commercial nodes often, but not exclusively, flanked by trabeated and arcuated porticoes that housed an assortment of shops and market stalls that would spill out onto the public spaces they flanked.[12] As Kim Sexton points out, the profusion and evolution of the postclassical porticus in northern and central Italian cities during the Middle Ages may have also visually symbolized civic transparency and openness to the citizens of self-governing towns. A time marked by a new ruling elite who took a greater interest in shaping and maintaining the city’s political, social, economic, and urban development than the rulers and governing bodies of earlier epochs.[13]

Rome’s late antique urban fabric was covered with such porticoes, primarily along streets that served as the stage for significant processions linking important extramural Christian basilicas to city gates that led to the urban center.[14] In some cases, the appropriation of pre-existing ideologically charged networks allowed for imbuing new meaning into these significant urban armatures. The most considerable street networks were created in the fourth century AD with the portico that spanned Saint Peter’s Basilica to the Pons Aelius, referred to as the Porticus Sancti Petri. The second part of this portico connected the Pons Aelius to the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls referred to as the Porticus Maximae.[15] The plan of the Porticus Maximae was developed with its culminating point positioned at the head of the Pons Aelius that terminated at the triumphal Arch of Gratian, Valentinian, and Theodosius, highlighting a threshold to one of the most significant Catholic churches in Rome. The Porticus Maximae passed along the ancient Via Tecta, the Theater of Balbus, and continued to the Pons Aelius. Fragments of granite column shafts considered remnants of these porticoes have been found along the Via dei Cappellari near Piazza Farnese and at the Piazza del Pianto and the Via della Reginella.[16] Similar findings between the Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, the Via Sora, and Via del Pellegrino, including a sizeable Ionic capital, have been attributed to this portico (Fig. 4).[17] The name of the present Via del Pellegrino is a reference to the memory of that pilgrimage route.[18]

Fig. 4. Ionic capital that is considered to be from or a model for the Porticus Maximae (present location: Antiquarium Comunale del Celio, author’s photo).

By the early Middle Ages, these porticoed streets continued to serve as significant pilgrimage routes and marketplaces. The Porticus Maximae even came to be known as the Via Mercatoria, “Market Street,” for the assortment of shops found along its course.[19] Many medieval residential façade porticoes identified in this study were located along these routes, yet they differ from their late antique counterparts in one significant way. They did not provide a continuous stretch of covered space commissioned by a single patron for public use. They were built by individual owners, providing covered areas for their personal and professional commercial activities. However, the systematized use of ancient spolia, including ancient single shaft marble and granite columns along with Ionic capitals, demonstrates a continuity of architectural language from late antiquity into the Middle Ages, which distinguishes Rome’s porticoed residences from those of other central and northern Italian cities.

The Piazza Giudia, situated along what was once referred to as the Via Mercatoria, is said to have been surrounded by porticoes since the Middle Ages.[20] Some of these buildings were still visible in historic views produced as late as the eighteenth century, such as those of Giuseppe Vasi and nineteenth-century visual property records.[21] The Piazza housed a food market with warehouses and a variety of shops which allowed some of Rome’s merchants in the district to gain significant fortunes in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, creating a new generation of urban aristocracy, ennobled families, referred to as Romani cives. Many had homes and businesses punctuated by façade porticoes in the Middle Ages, including the Massimo and Pichi.[22]

The Significance of Porticoed Residences in Medieval Italy

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s fresco “Effects of Good Government on City Life” (1338-40) in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena underlines the importance of architectural spaces that framed commercial activity during the Middle Ages. His fresco celebrates working-class artisans and merchants, emphasizing their significant contribution to maintaining the health and well-being of society (Fig. 5). They are depicted doing their work in public view along a commercial street, enclosed by sizeable arcuated openings. Rome’s porticoed shop fronts were equally significant to its working-class population as the large arcuated openings visualized in Lorenzetti’s fresco cycle. Yet, this architectural feature that once served as the stage for Rome’s most important streets and piazzas has almost wholly disappeared. The practical erasure of their presence from the metropolis’s modern streetscape has left a significant gap in our understanding of the housing type that once framed the everyday life and labor of a substantial part of Rome’s population throughout the Middle Ages.

Fig. 5. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, The Effects of Good Government detail of the fresco in the Sala dei Nove, Palazzo Pubblico, Siena. 1338-1340 (artwork in the public domain; photograph provided by Scala/Art Resource, NY).

According to Francesca Bocchi and Enrico Guidoni, when examining the origin of porticoed streets and piazzas in European cities in the Middle Ages, it is essential to consider their practical and functional aspects and how they were rationalized, standardized, and codified over time.[23] As a protruding element along the surface of a private residence onto a public street or piazza, the construction of porticoes attracted the attention of local authorities early on in their urban development. By the late Middle Ages, their presence was either perceived as a public nuisance imposed by private owners’ intrusiveness on the public realm or as a beneficial architectural feature that could provide streets and piazzas with order and decorum.[24] Archival records dating from the beginning of the thirteenth century reveal that in the commune of Vicenza, local authorities exhibited their control of the area by mandating about one hundred porticoes and profferli (external stairs) built without the proper permission be demolished.[25] However, residential porticoes were not eradicated from the city of Vicenza. Those that conformed to the local urban regulations were maintained and are still visible today. In the same period, administrative records reveal that private houses in Bologna were required to have porticoes built for public use. They became a compulsory architectural feature that considered the regularization of pedestrian passage while providing ample space for merchants and artisans to work outdoors in front of their ground-floor botteghe (shops).[26] The local power of crafts guilds and their representation in civic matters contributed to how porticoes became such an integral and long-lasting part of Bologna’s local architectural form.

David Friedman has found in his analysis of several medieval founded towns in Switzerland, France, and Italy that systems of porticoes were not part of the original master planning schemes.[27] Porticoes were added later by individual owners and only permitted on the broadest streets and in the market piazzas, and were thus a privilege that was not afforded to every resident. The space under such porticoes remained public land and was maintained by private owners who eventually became the wealthiest citizens of these towns. They could display their goods under these porticoes to the public without paying a fee for setting up at the local market. Likewise, they gained an income from renting their porticoes to other merchants.[28] Rome’s relationship with its porticoes is less well documented; however, property sales, registered rental agreements, and land disputes related to porticoed residences do exist, providing a better understanding of their use from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century. It was not until the second half of the fifteenth century that they appeared more frequently in the accounts of urban magistrates, as permits were necessary to construct new ones, and those seen as a threat to public safety and circulation could be destroyed.[29]

The Evolution of Residential Architecture in Medieval Rome

Despite Rome’s long history and ongoing development, very little is known about the evolution of its residential architecture from late antiquity to the early Middle Ages. Almost no surviving dwellings in the city center date to this period. Before the eleventh century, the houses of Rome’s aristocracy were referred to in property sales as domus maior (principal house) or curtes (courts). Many of these homes used ancient building materials, and a significant number were built above or inside the remains of ancient structures, including temples, theaters, triumphal arches, and porticoes.[30] The earliest surviving remains of medieval residences in Rome dated to the mid-ninth century were found in the Forum of Nerva during excavations in 1995-97.[31] Two houses were revealed to have been built primarily of peperino (brown or grey volcanic tuff), brick, and other architectural materials from the surrounding ancient monuments. The houses were on either side of a street, the larger one having an arcuated portico supported by stone piers. Some additional smaller ancillary structures were attached to these houses, each with a walled plot of garden flanking them. The homes are unique in that they do not reflect housing types of antiquity or late antiquity, or even the later Middle Ages. They represent a new early form of medieval housing closer to a farmhouse rather than an urban dwelling with spaces on the ground floor that included a portico, storeroom, kitchen, servants’ quarters, garden, and outbuildings. Areas for sleeping could be found in the second story. Structures such as these represented the housing of Rome’s aristocracy or curtes.[32]

Following these two houses, Rome’s next oldest extant medieval residence is the Casa dei Crescenzi, built between 1040 and 1065 by Nicolò di Crescenzio.[33] The building has two floors, a walled-in, trabeated, engaged portico made of brick with a highly organized use of spolia taken from various ancient Roman buildings. The home’s sophisticated use of ornate ancient stone carvings indicates the patron’s conscious effort to display fragments from antiquity in a celebratory manner. The design also references ancient Roman temple architecture. Its engaged colonnade emulates the one found along the façade of the Temple of Portunus.

The Sack of Rome in 1084 also contributed to this period’s lack of housing. Henry IV’s attack is said to have destroyed the stretch of the Porticus Maximae leading to the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls, along with the portico of the Borgo of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Severe damage to the Tabularium and the Septizodium, which housed the Corsi and Frangipane families, occurred due to the same assault. The most extensive destruction was done by Robert Guiscard when he came to Rome to release Pope Gregory VII from Henry IV’s captivity. During this time, he set the entire Campus Martius on fire along with the Caelian Hill, the latter not recovering until the late nineteenth century.[34]

Despite the lacuna of physical evidence of Rome’s early medieval housing stock, Étienne Hubert has contributed substantially to the subject by examining early property sales.[35] The documents reveal that at the beginning of the twelfth century, most of Rome’s housing stock consisted of a significant number of single-story buildings referred to as domus terrinea, many of which were fronted by a courtyard facing the street with a garden behind. The documents also refer to the residence and its garden’s relationship to the street. These homes often had a vegetable garden at the back while the front was situated along a public street or piazza (domus cum orto post se or domus cum platea ante se). Houses appear to have been evenly distributed throughout the city inside the Aurelian Walls and almost always separated.[36] Hubert found no evidence of continuous rows of facades in Rome before 1200.[37] One contributing factor to the lack of physical evidence of residences in early medieval Rome is that many were made of wood, similar to other northern and central Italian towns.[38]

The population of Rome increased in the twelfth century resulting in the construction of a more significant number of new homes. Rome’s working-class lived in a house type common in towns throughout central and northern Italy in the Middle Ages, consisting of a bottega on the ground floor with living quarters above.[39] Residences with two stories such as these or domus solarata became common by the beginning of the thirteenth century. Many times, they also included a portico like the one purchased for one hundred gold fiorini (florins) by the goldsmith Petrus Tramundi in 1394 from Margherita, wife of the notary Nicolaus Spaççamaçça.[40] The house was located on the market piazza in the rione Campitelli. The two-storied home included a façade portico with additional permanent market stalls to display goods for sale. This house was fused with another two-storied porticoed home that Tramundi had purchased in 1382 for ninety gold fiorini. By 1396 Tramundi rented the market stalls in front of his second porticoed structure to women who sold terracotta vases. We know of this rental from a disturbance made to these women, their products, and to the property owner Tramundi by Mattia di Gregorio Margani in 1396.[41]

The Trecento also saw a marked increase in three-story homes, called domus solarata cum tribus solariis.[42] These houses often had a door beside the workshop leading to a stair, usually made of wood that was a single flight without a landing. Some residences had profferli often made of stone. The ground floor was frequently two cells deep, the one facing the street used as the workshop and the one behind as a living space. Based on visual evidence, corridors were not present until the sixteenth century, and many had a garden at the back of the house. A portico often fronted these mixed-use commercial/residential structures (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Plan of a house with a façade portico in Rione Monti (author’s drawing after plan in ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, Vol. 1281, Libro delle Case, 31r).

While the spacing between buildings was more open during the Middle Ages than in the dense urban layout of Rome from the mid-fourth century AD, the use of the porticoes along streets persisted. Moreover, they served as the narthex along the facades of churches, covered the surface of secular buildings such as the Palazzo dei Conservatori and Palazzo Senatorio on Capitoline Hill, and fronted private residences. Despite the difficulty in dating medieval Roman homes due to continuous restoration over the years, Patrizio Pensabene underlines the importance and necessity of drawing parallels between medieval church architecture and residential façade porticoes. First, for the uniformity of trabeated and arcuated systems supported by columns utilized in the naves of churches. Second, for the specificity of the narthex designs of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries that used horizontal trabeation and arches supported by columns. Furthermore, there was an adherence to the use of the Ionic capital, which was sometimes reused from ancient or late antique monuments but was more often of medieval design.[43] Pensabene suggests that the abundant use of the Ionic order in medieval Rome may be a continuation of the late antique practice of using it, as seen in the repair of the Temple of Saturn and, as previously mentioned, at the Porticus Maximae.[44]

Urban planning regulations in Rome resembled those of other Italian cities during the Middle Ages despite the inconsistent state of its political authority. The Codex Justinianus and other later imperial sources reveal that the offices responsible for managing the city’s streets and squares, referred to as the magistri aedificorum or maestri di strada (urban magistrates), existed in some form from late antiquity to the Middle Ages. The Codex Justinianus dedicated an entire chapter to maintaining Rome, its monuments, and its infrastructure. The city’s public buildings were to be preserved and repaired along with the banks of the Tiber, Forum, Roman harbor, and aqueducts.[45] In the centuries that followed, urban magistrates continued the ideas of Justinian to various degrees. Their primary function was to maintain public space, preventing private properties from encroaching on streets while preserving the city’s walls, river embankments, and waste disposal.[46]

A more significant number of fortified residences, including casatorre (tower houses), were built by members of the aristocracy at this time. Evidence suggests there were as many as 318 towers in medieval Rome, creating an animated skyline.[47] In the thirteenth century, under the civic administration of Brancaleone degli Andalò, the Bolognese nobleman, Republican, and lawyer, the organization and economic power of Rome’s guilds were strengthened. In contrast, the authority of the city’s local noble families was restricted. According to Torgil Magnuson, it was during Brancaleone’s administration that “no less than one hundred and forty towers belonging to the city’s various aristocratic families were demolished in 1257 before his premature death in 1258.”[48] Porticoes were not listed at this time, even though they were occasionally present at the base of these structures.

In many cases, these tower houses formed part of more substantial fortified mansions and could be found in the rioni of Monti, Ponte, Parione, Regola, Pigna, and Trastevere.[49] These compounds included a primary dwelling for the principal heads of the family and their relatives. Additional attached structures supported multiple functions, providing various housing options for working-class Romans and their businesses. These included shops and workshops with housing above, forming parts of city blocks like the smaller clusters of residential fabric surrounding the Palazzo Taverna of the Orsini family that still exists today, situated on the Monte Giardano in the rione Ponte. The Torre dei Conti and Palazzo Altemps were also once part of clusters of buildings punctuated by several towers of various heights, creating a private compound in the city’s center.[50] By the late Middle Ages, these towers and the mansions to which they were attached were seen as status symbols of the aristocratic families to whom they belonged. Porticoed structures flourished at this time. They could be found at the base of these tower houses and fortified mansions, including those belonging to the Alberteschi and Mattei on Via della Lungaretta in Trastevere.[51]

Residential Façade Porticoes in Medieval Rome

Henri Broise and Jean-Claude Maire Vigueur’s study on the social use of the house in late medieval Rome found that most Romans owned the home in which they lived—allowing for the assumption that the purchase of a home was within reach to a majority of the population. Housing records in the second half of the fourteenth century indicate that many houses were sold for less than fifty fiorini. The type of house was often small and comprised of two stories with two rooms on each level. The ground floor often had a portico, while the upper level contained a loggia or balcony.[52] Houses in the principal market piazzas were often more expensive as they provided greater visibility and profits to the homeowner. The widespread use of porticoes in Rome in the late Middle Ages is primarily demonstrated in the archival records of notarial registers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.[53] These porticoes were especially prevalent in areas with the highest concentration of commercial activities. The portico was also where notarial contracts were signed and belonged either to the notary himself or a third party. Charles Burroughs has provided greater context for how activities such as signing legally binding documents, judicial hearings, and other legal activities shaped the late medieval semi-public space in Rome and Florence. He has found that porticoes played a critical role in framing social rituals, including those related to cases of arbitration, betrothal, and marriage, amongst others.[54] Fabrizio Nevola has echoed such sentiments, finding residential porticoes situated along city streets to have fulfilled formal functions for the families they belonged to, serving as the frames of significant events such as weddings and funerals.[55] Modigliani’s research reveals that porticoed houses situated in market piazzas and those of aristocratic households near the markets most often belonged to a single owner, which is reflected in the purchase records of such homes. Joint ownership between co-heirs was also standard. The ground floor commercial space, such as the portico, was often sold separately to such family members.[56]

By the fifteenth century, porticoed houses situated along commercial streets owned by working-class residents were subdivided into increasingly smaller spaces that were either rented or sold for additional income.[57] Porticoed residences owned by the church and the city’s aristocracy also served as income-generating properties often rented to the working-class. In 1365, a two-storied house with a façade portico in rione S. Eustachio was rented annually for ten soldi (coins).[58] While during that same year, in the nearby Campo de’ Fiori, a two-storied house with a façade portico, vegetable garden, and well in the back was rented by the canons of S. Lorenzo in Damaso to a spice merchant for fourteen gold fiorini a year.[59] In 1468, the nobleman Mattia de’ Normandi of rione Colonna sold one of his properties, a terrineum or ground floor house in rione Ponte along the Via Recta (Present Via dei Coronari) in the area of Monte Giordano to a tailor. The sale was for a portion of a house. The purchase included a room, kitchen, and a part of a façade portico.[60] Not far from this sale was another rental recorded in 1401 of a building leased by the Florentine merchant Lucas Nycolai at the Canale di Ponte. The house included market stalls, a portico, a shop, and other rooms situated on two floors.[61]

What did these porticoed residences look like in medieval Rome? What characteristics distinguished those belonging to the city’s aristocracy from the working class? Upon closer examination of existing remnants of Rome’s medieval porticoes coupled with visual records in archival sources and historic views, a clear picture emerges of four distinct subtypes of porticoed facades. Type I discussed in this study is the trabeated portico and is most likely the earliest form constructed in Rome. I have identified ten extant trabeated porticoes in seven rioni (Figs. 7-8).[62] According to Pensabene and Lorenzo Quilici, the most probable precedents for the trabeated portico are the narthexes of Catholic churches in Rome that date to the twelfth and thirteenth centuries; thus, these trabeated examples can also be dated to around the same period. Precedents include the narthexes of San Giovanni e Paolo, San Giorgio in Velabro, and Saint Lawrence Outside the Walls, all dating from the twelfth century.[63] The architectural elements common to these religious structures also exist at the residential scale. They include adherence to single shaft columns with Ionic capitals that support a cornice and architrave. Of the trabeated examples identified in this study, only one does not exclusively use Ionic capitals, possibly signifying a replacement of the original column capital and shaft at the corner of the building (Via di S. Bonosa, 22).

Fig. 7. Trabeated porticoes: A. Casa Bonadies, Via del Banco di Santo Spirito, 62. B. Via Capo di Ferro, 31. C. Via dei Giubbonari, 64. D. Via di S. Bonosa, 22 (author’s drawings).

Fig. 8. Trabeated porticoes: A. Piazza Fontana di Trevi, 91-92. B. Via dell’Arco de’Ginnasi, Largo di Santa Lucia Filippini, 5. (Author’s drawings).

Classical proportions associated with using the ancient Ionic order were not found in the medieval examples noted here. Entablatures have a simplified architrave and cornice without a frieze. Column shafts lack the relationship between base diameter to the overall height of the column and entablature due to the reuse of spolia taken from various ancient sources. Horizontal blocks of white marble were taken from ancient Roman buildings and re-carved in several of the case studies examined here to provide a coherent decorative system. The cornices of late antique buildings were reused at the Casa Bonadies and Via Capo di Ferro. The white marble utilized for the Ionic capitals was taken from ancient buildings but re-carved by medieval masons. Only a few were taken directly from late antique buildings, such as those found at the Palazzo Mattei in Trastevere. The regularity and orderliness of the carving of the Ionic capitals make it clear that specific workshops in Rome were responsible for their production. Only a few examples in this study depart drastically from the standard model of the Ionic capital in medieval Rome, including those found at the Casa Bonadies and one of the capitals of the Palazzo Ginnasi (See Fig. 3). The single-shaft stone columns were taken directly from ancient monuments and carved or adjusted only slightly to meet the needs of the new buildings they adorned. The abundance of grey granite columns in this study signifies the prolific use of this material in ancient Rome. The other reused materials commonly found in the column shafts examined were red granite and cipollino marble. Ancient column bases were often used as-is from antiquity or are not visible. The carved medieval column base examples were either simple plinths or variations from antiquity.

The observance of a specific architectural language along the surfaces of buildings in Rome in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries appears to have been a strict priority. It is manifest in both religious and residential structures. Alberti wrote in the second half of the fifteenth century, “The portico of the highest citizen ought to be trabeated, and that of the ordinary man arched; both should preferably be vaulted.”[64] While Alberti was writing in the mid-fifteenth century, his association of trabeated porticoes to wealthier patrons would have been as accurate during his time as in previous centuries. As Pensabene notes, the cost of trabeated porticoes was higher due to the difficulty in procuring marble or stone members long enough to span the entire length of a portico uniformly. Moreover, it was difficult to find several ancient single shaft stone columns of the same height. Trabeated porticoes were thus cost prohibitive for the working-class and a luxury item for wealthy homeowners such as the noble Mattei family in Trastevere. On the other hand, the arcuated portico in brick offered a much cheaper and more accessible alternative for porticoed structures. The arches also easily absorbed the irregularities in the size of openings and heights of columns better than their trabeated counterparts.[65]

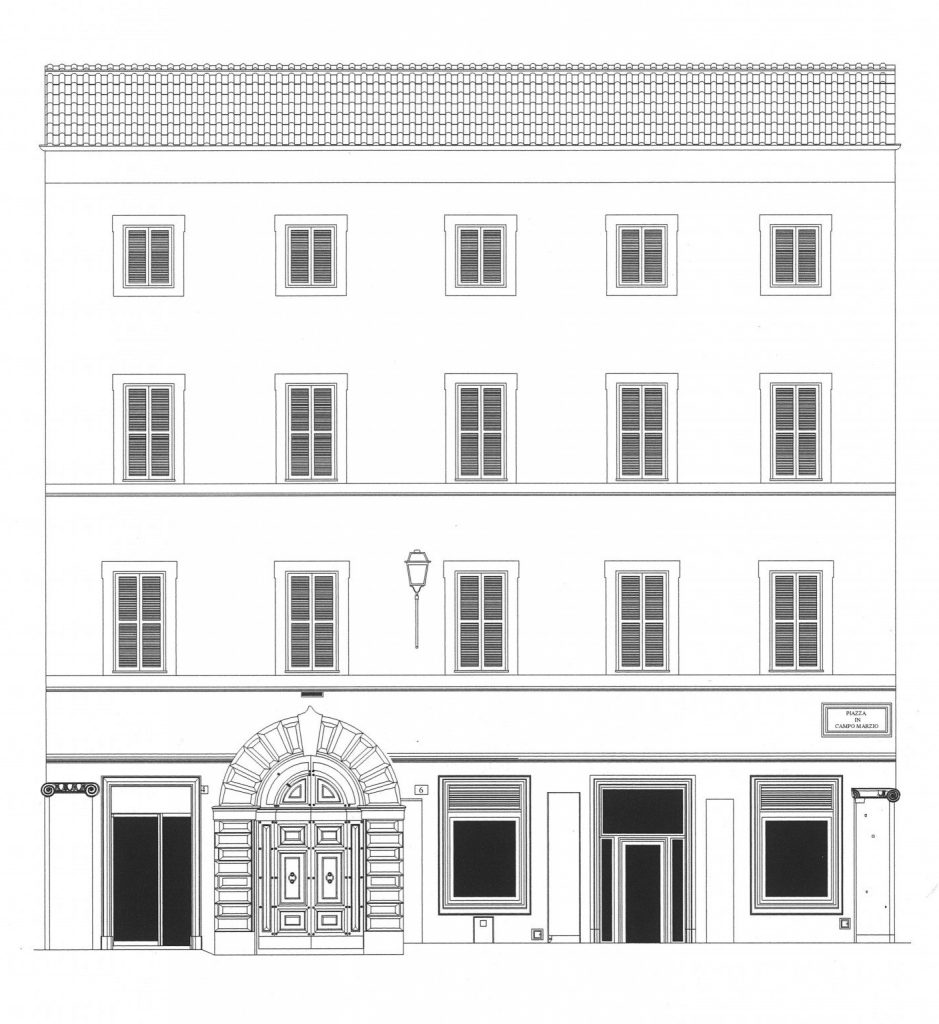

Of the ten extant trabeated porticoes identified in this study, it is possible to determine precisely when one of them was immured. In 1486, the homeowner of the palazzo presently located at Piazza Campo Marzio 5-6, Mario Alessandrini, submitted a request to the maestri di strada for permission to close the portico of his residence because vagabonds increasingly occupied it (Fig. 9).[66] Alberti voiced similar concerns about the appropriate use of porticoes earlier in the century. While praising their usefulness, he noted that they should serve all citizens and not only be a haunt for servants.[67] The request was submitted merely two years after Pope Sixtus IV’s death and indicated that the removal or closure of porticoes in the second half of the fifteenth century was executed by papal authorities and property owners alike.

Fig. 9. Remnants of medieval residential façade portico at Piazza Campo Marzio, 5-6 (author’s drawing).

Type II is referred to here as the arcuated portico. It was made of a series of brick arches that run along the façade of a residence, supported by single-shaft columns that have either Ionic capital, a carved abacus, or a combination of the two (Fig. 10). Similar to the first type, the arcuated portico has its equivalent in medieval church construction and is still visible today along the façade of Santo Stefano Rotondo. Of the medieval residences examined in this study, twenty-four existing arcuated porticoes were recognized in seven rioni.[68] The arches either spring from an Ionic capital or a simple abacus and, in some cases, an impost block. As previously noted, the arcuated system of porticoes from antiquity to the Middle Ages was a much more affordable construction method. The brick arch was thus cost-effective and flexible, accommodating irregularly sized openings. Column shafts were always made of despoiled materials, and single shaft stone columns were either short and stout or tall and slender. Ancient column bases were also employed in some buildings, while medieval builders carved new ones when needed. Columns sit directly on the ground, a carved base, or an elevated marble slab. These structures either stood alone as a single arched opening like those represented in Lorenzetti’s fresco cycle or were two bays wide. Others were eventually fused with neighboring structures to create a continuous façade. The architectural details employed in the arcuated surfaces identified in this study were generally more humble and significantly less ornate than those found along the surfaces of trabeated and tower house structures.

Fig. 10. Arcuated porticoes: A. Piazza di Santa Cecilia, 19. B. Via della Lungaretta, 160-161. C. Via Tribuna dei Campitelli, 23-23 B. D. Case di San Paolo, 4-7. (author’s drawings).

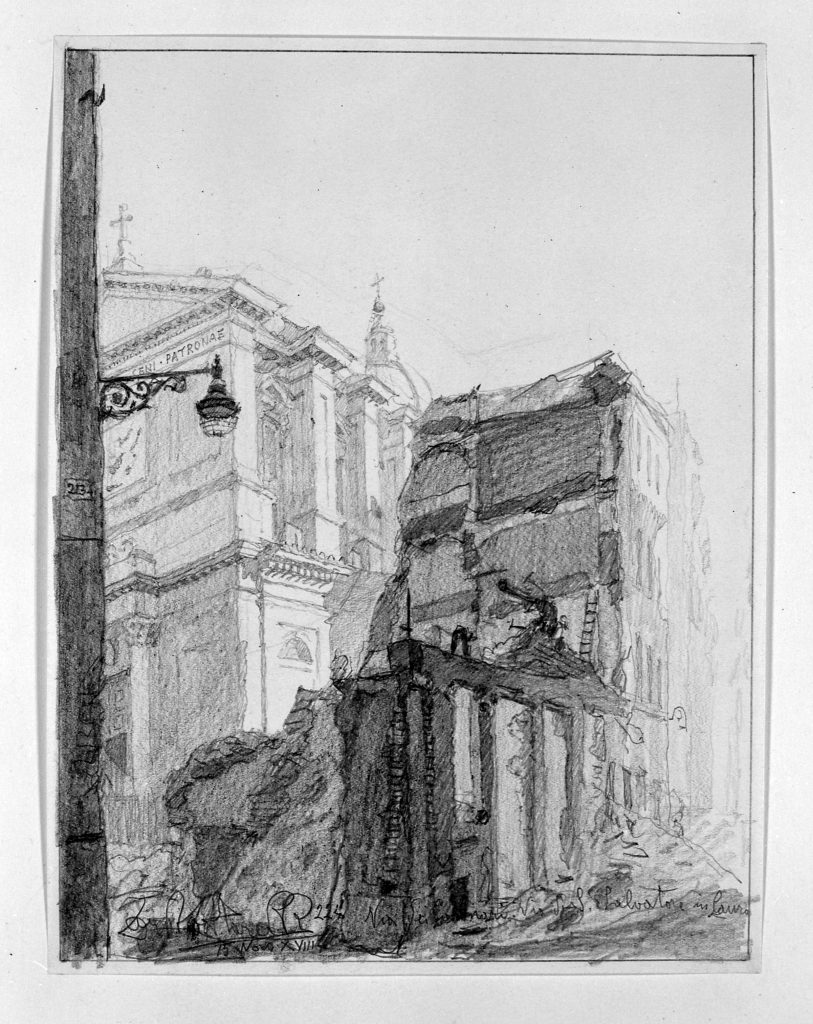

Type II appears to be one of the most commonly built in Rome and is even visible in historical views of the city. It seems to be the porticoed structure most accessible to Rome’s working class, who owned or rented these commercial spaces. Images of Rome like the one made at the Forum of Nerva through the Arcus Aurae framing the historic Argiletum; the present-day Via Madonna dei Monti captured the remnants of this medieval housing type that persisted in Renaissance Rome. These particular views are significant to this study as they depict a four-bay arcuated residential portico in an area that continued to house a functioning one to the late nineteenth century and is still home to another immured medieval structure (Fig. 11). This streetscape is represented in over 200 years of drawings and etchings found in the Codex Escurialensis, along with those made by Domenico Ghirlandaio, Marten Van Heemsckerck, Hieronymous Cock, Mathys Bril the Younger, Marco Sadler, and several others.

Fig. 11. Mathys Bril the Younger, The Ruins of the Forum of Nerva, seen from the southwest. 1570-80 (Art Resource, NY).

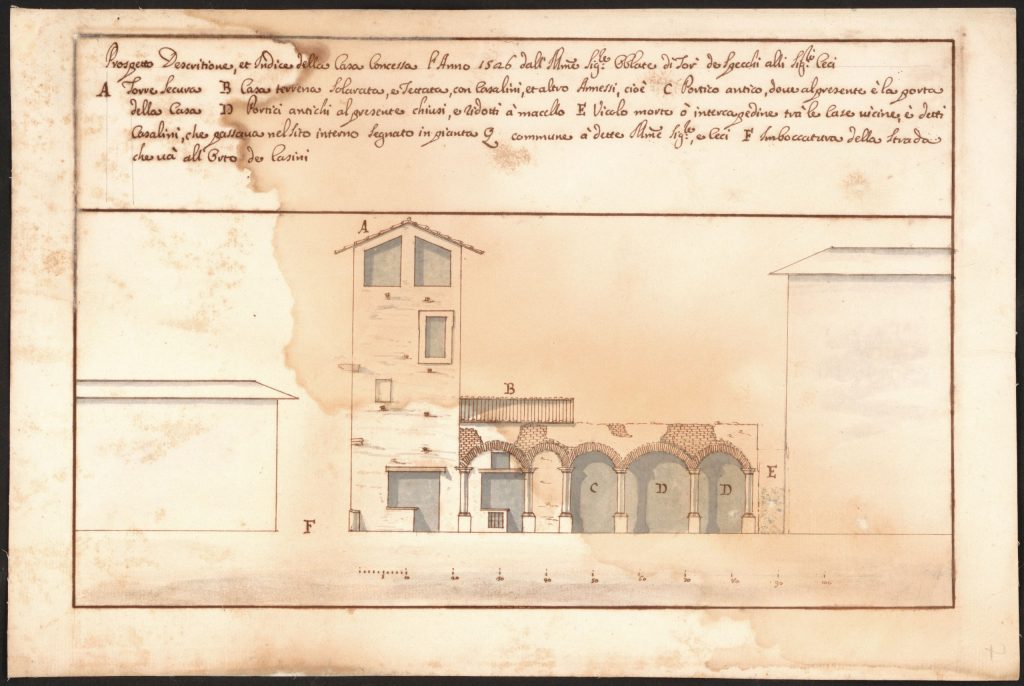

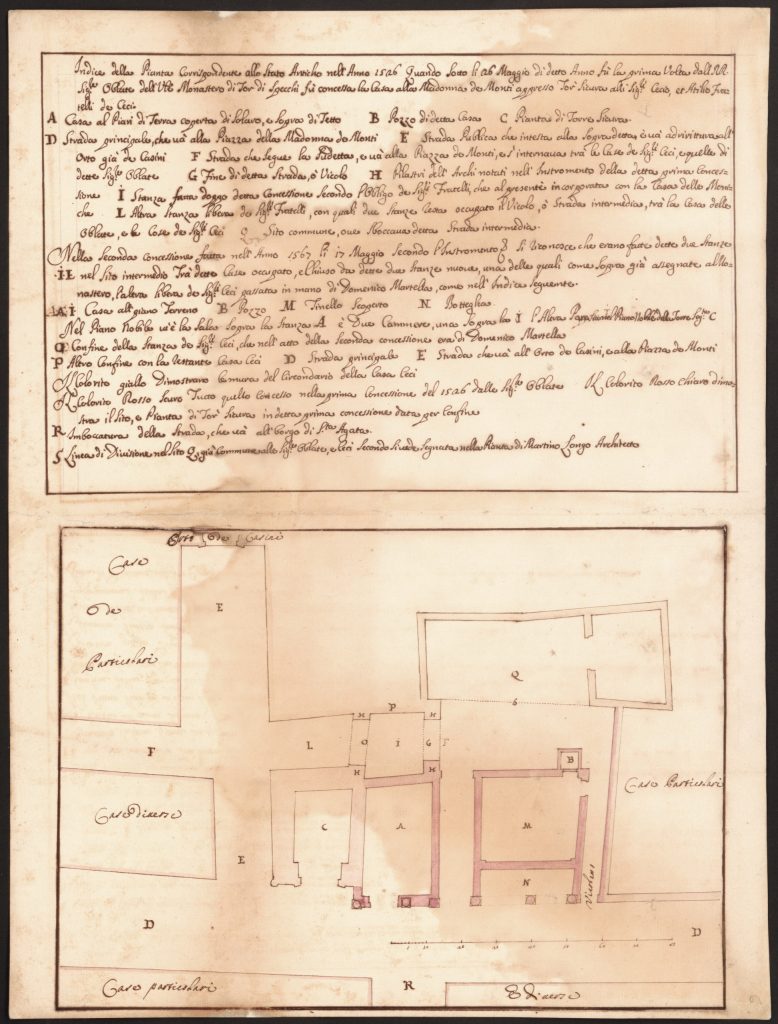

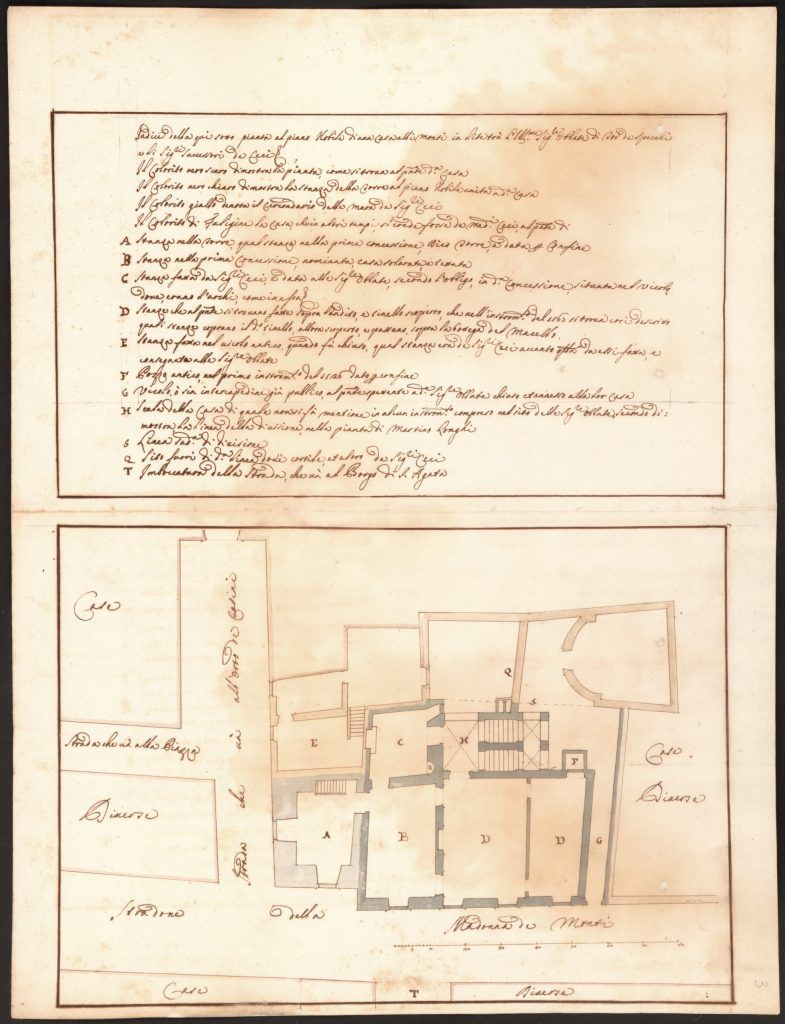

The portico is visible in similar detail and character in all of the views, appearing to be a part of the block that historically belonged to the Conti family. Inside the compound was the previously mentioned Torre dei Conti that still stands in the neighborhood of Monti today. The surrounding block to which it was attached has been demolished, leaving only the tower and a single two-story residential building. The medieval portico immortalized in these views appears to have had two floors. It is similar in size and character to an existing arcuated fourteenth-century portico on the same street facing the Church of San Salvatore in Monti, located at 67-69 (Fig. 12). The architect, Martino Longo, more commonly referred to as Martino Longhi I (the elder), visually documented the building’s long history and transformation in the second half of the sixteenth century.[69] The plans were drawn up for a lawsuit between the Oblate di Tor de Specchi and the Ceci family heirs. Two designs described the state of the house on 26 May 1526 during the first sale when it was granted by the Oblate di Tor de Specchi to the Madonna dei Monti next to the home of the Ceci family and during the second sale on 17 May 1567 (Figs. 13-16).

Fig. 12. Arcuated portico along Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69 (author’s drawing).

Fig. 13. Elevation drawn by Martino Longhi I (the elder) of the house located on Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69 describing the state of the complex in 1526. See ASR, Collezioni disegni e mappe-Collezione I, Segnatura: 83-87/1.

Fig. 14. Plan drawn by Martino Longhi I (the elder) of the house located on Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69 describing the state of the complex in 1526. See ASR, Collezioni disegni e mappe-Collezione I, Segnatura: 83-87/1.

Fig. 15. Elevation drawn by Martino Longhi I (the elder) of the house located on Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69 describing the state of the complex 17 May 1567. See ASR, Collezioni disegni e mappe-Collezione I, Segnatura: 83-87/1.

Fig. 16. Plan drawn by Martino Longhi I (the elder) of the house located on Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69 describing the state of the complex 17 May 1567. See ASR, Collezioni disegni e mappe-Collezione I, Segnatura: 83-87/1.

Longhi’s older plan represents the historic tower or torre sicura. It was attached to two other porticoed structures with a passage separating the colonnaded facades, which would eventually be the location of the staircase leading to the piano nobile added sometime between 1526 and 1567. Both sales describe the usage of the portico on the right side of the plan as a macello (slaughterhouse). As Modigliani notes, towards the late Middle Ages and well into the fifteenth century, one could find many slaughterhouses and butcher shops near the Campo Vaccino (Cow Pasture in the Roman Forum), especially in the direction of the rione Monti, near the Forum of Nerva and the Torre de Conti. These shops were often fronted by a portico that would protect the delicate merchandise from the sun.[70] The house’s façade has remained almost identical to its sixteenth-century appearance, as depicted by Longhi. The tower is slightly set back from the narrow arcuated portico that maintains the continuous property line with the Via della Madonna dei Monti.

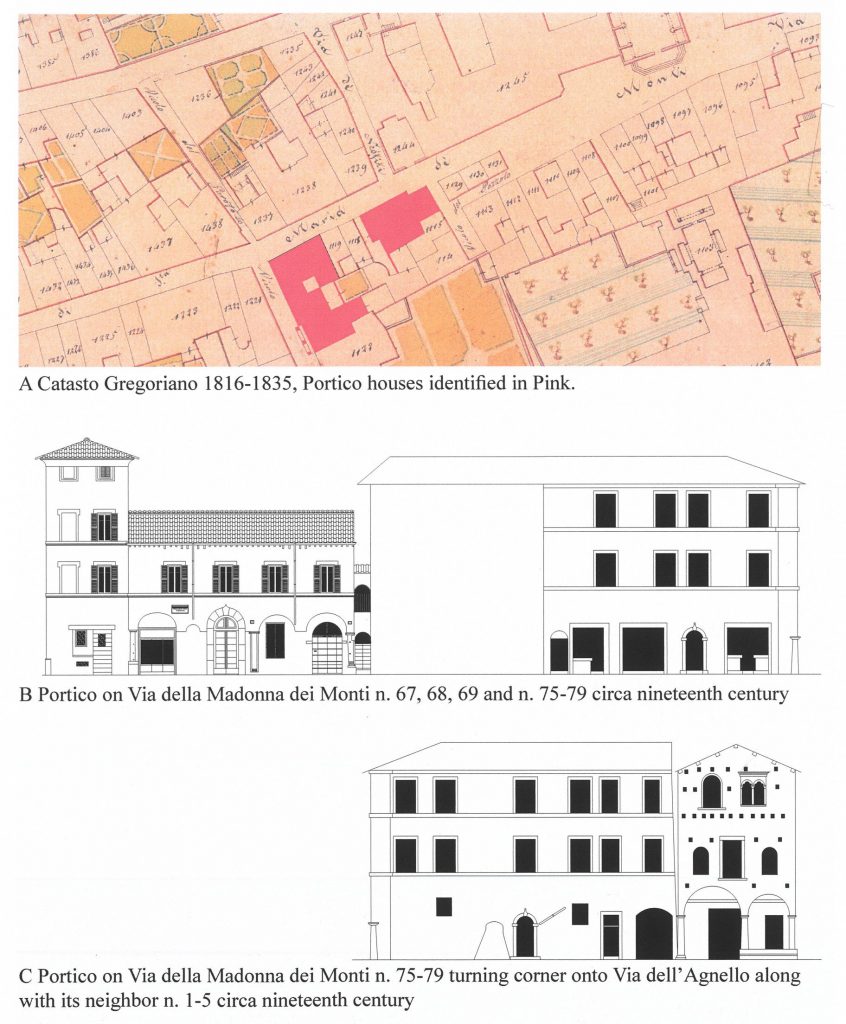

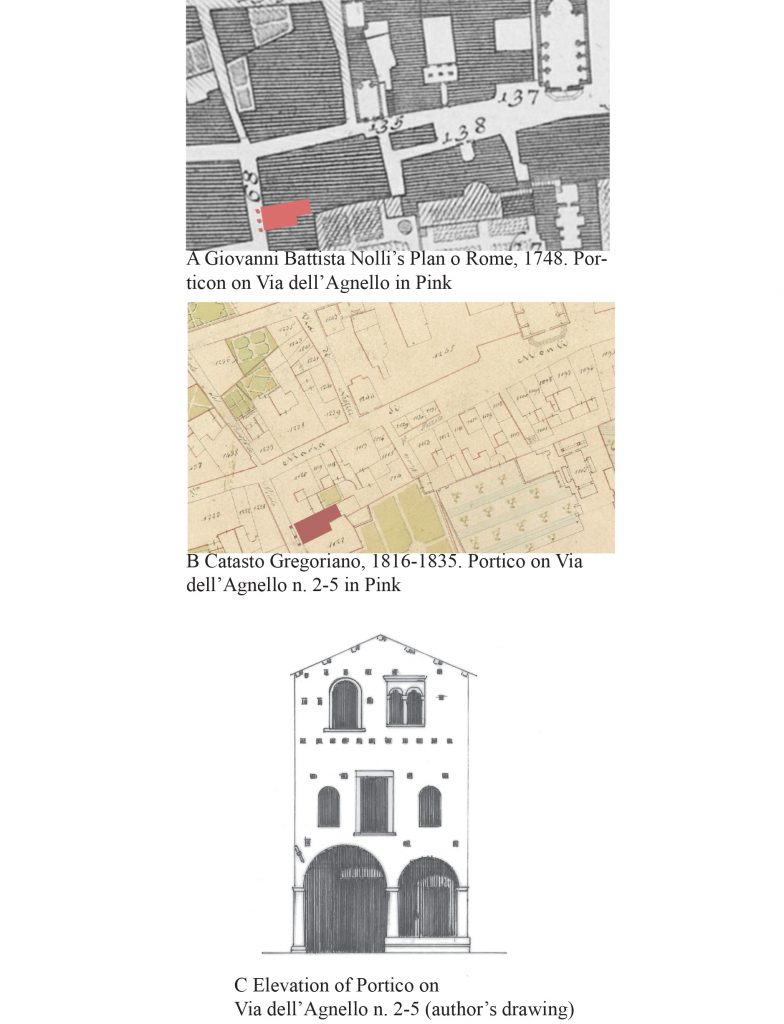

At the corner of the Via dell’ Agnello is another portico documented in the Archivio di Stato di Roma (ASR), indicating that the current residential structure at numbers 75-79 once had a portico as well. Until the 1860s, a façade portico was situated here and unique for several reasons. First, it was one of the few residential porticoes that survived closure in the center of Rome until the nineteenth century, prominently appearing in historical maps as an open portico projecting beyond the confines of the street setback. Second, unlike its companions that were slowly immured over time beginning in the second half of the fifteenth century, this portico is prominently visible in Giovanni Battista Nolli’s Nuova Pianta di Roma (1748) and the Catasto Pio Gregoriano (1819-24) (Figs. 17-18). Antonia Pugliese’s study of this residence denotes the peculiarity of its survival. It was destroyed only after the introduction of the Via Cavour in the late nineteenth century. The building’s projection into the narrow street impeded traffic movement, which was once used for the papal courts’ return from the Basilica of Saint John Lateran to Saint Peter’s Basilica.[71] It was exceptionally well documented, showing up in plans and archival sources at the ASR. Moreover, the building appears in several paintings by nineteenth-century Danish artists, including the works of Ernst Meyer. For Meyer, the building served as a backdrop for his illustrations in different locations in Rome, including Un Vicolo a Roma and Arco de Pantani; it also appears in drawings by Enrico Retrosi as the Osteria del Gatto Nero.[72]

Fig. 17. A. Catasto Gregoriano 1816-35, portico houses identified in pink (Image, Archivio di Stato di Roma). B. Portico on Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67-69 and 75-79 in the nineteenth century. C. Portico on Via della Madonna dei Monti, 75-79 turning corner onto Via dell’Agnello along with its neighbor, 1-5 in the nineteenth century (author’s drawings after originals in the Archivio di Stato di Roma, Archivio del Comune Ponteficio 1847-1870/19272).

Fig. 18. A. Giovanni Battista Nolli’s, Nuova Pianta di Roma, 1748, portico on Via dell’Agnello in pink (Image, Architecture Library, University of Notre Dame). B. Catasto Gregoriano, 1816-35, portico on Via dell’Agnello 2-5 in pink (Image, Archivio di Stato di Roma). C. Elevation of portico on Via dell’Agnello 2-5 (author’s drawings after originals in the Archivio di Stato di Roma, Archivio del Comune Ponteficio 1847-1870/19272).

Type III, the tower-house portico, is found at the base of medieval towers, creating an arcuated permeable base to an otherwise defensive and closed structure. In this study, three of this type were identified and located in two rioni (See Fig. 2).[73] Two belong to the cluster of houses in rione Regola, referred to as the Case di S. Paolo and were once part of an even larger medieval block that was destroyed in the twentieth century for the construction of the Ministero della Giustizia. The Case di S. Paolo are partially embedded in the Ministry building referred to as Palazzo Piacentini and were eventually heavily restored. The towers are located at either end of a series of five fused houses that support one another, creating a continuous porticoed façade. As mentioned above, the complex was located in an area once filled with porticoed dwellings of different sizes and characters, including a five-bay porticoed house in the area sited along Via S. Bartolomeo degli Strengari that is now demolished but known from photographs as noted by Richard Krautheimer.[74] The other tower house identified here is in rione Campitelli, which once belonged to the Margani family. It was part of a large complex in the homonymous Piazza (Piazza Margana). Records show that the family obtained multiple properties, including those with porticoes, in the area from the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries. On 13 September 1305, Giovanni di Giovanni Margani purchased a casa solorata with a portico along the façade supported by three columns for 170 gold fiorini. This building was adjacent to the properties of Giacomo di Nicola Margani. These buildings were eventually subdivided, portions of which were sold to extended family members, as was the case when Lorenzo Margani sold to his sister-in-law Caterina, wife of his brother Ludovico, half of a dining room and portico under their house. Both were shared with Lorenzo, who owned the other half of both spaces.[75] Like the trabeated and arcuated porticoes, those at the base of these towers used single shaft granite columns and marble capitals. At the Case di San Paolo, simple stone capitals are used on the tower houses. Yet, one arcuated bay in the center of the overall complex utilizes Ionic capitals of fine craftsmanship, one of which includes the carving of a snake wrapping around the volute, eating its own tail. The historic Margani tower, on the other hand, makes use of a finely carved Ionic capital.

Type IV, the townhouse portico, comprises two arched openings supported by a single-shaft column with an Ionic capital or carved abacus and appears both with or without a base (Fig. 19).[76] According to Piero Tomei, this is the residential type from which the Renaissance casa a schiera (townhouse) emerged as it is datable to the end of the fourteenth to the first half of the fifteenth century. Five examples of this type were found in two rioni. The most famous one is known as the Casa della Fornarina (the Baker’s daughter) in Trastevere on Via di S. Dorotea, 20. The house is said to have once belonged to Raphael’s muse, the beautiful Margherita Luti. Regardless of the validity of the well-known historical figure’s occupancy of this dwelling, the housing type is noted in several historic visual records dating from the sixteenth century to have housed different types of commercial activity, including bakeries, barber, and spice shops.

Fig. 19. Townhouse porticoes A. Via Arco della Pace, 10 B. Via dell’ Orso, 11 C. Casa della Fornarina, Via di Santa Dorotea, 20 D. Casa di Fiammetta, Via dei Coronari, 157 (drawing after the one made by Bruno Maria Apollonj Ghetti in 1937, when the portico was revealed) (author’s drawings).

These mercantile activities of porticoed residences often appear in plans recorded in the libro delle case, or book of houses, produced by several lay confraternities in Rome from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries.[77] These detailed inventories represent a single plan of an individual building, or sometimes numerous buildings that make up a single city block, with annotated notes, including the previous owner, (then) current renter, and the dimensions of the building. When these books were produced, street addresses were not used, making it difficult to precisely associate a building’s plan with a specific location, even though rioni are always mentioned.[78] A bakery similar to the Casa della Fornarina in Trastevere is recorded in the Case dell’Ospedale del Salvatore of 1597 in the rione Parione, the portico fronting the street of the same name.[79] The Libro delle piante di tutte le case della SS. Annunziata, produced in 1563 and 1636, represents a house in rione Parioni with its portico opened along the Via Capellari enclosed at the sides. The 1563 plan indicates the renters’ names and other distinguishing features, such as the attached medieval tower. The structure is represented as relatively simple in layout, only two cells deep, and each unit provided with a stair. The 1636 plan depicts the same building chopped up into smaller units. The portico was invaded by additional stairs leading to a lofted area built under it and flush with the street. The units on the ground floor behind the portico functioned as a warehouse and a barbershop.[80] While plans of these structures produced in the Middle Ages do not exist, those made from the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries reveal the nature of the urban transformation of these medieval houses in Rome. Increased population and higher rents resulted in the subdivision of existing structures into smaller units.

Of the fifty-six extent structures identified in this study, seventeen could not be classified under any of the subtypes mentioned due to the fragmentary nature of the visible portico elements; the rest are hidden beneath layers of stucco. The remnants of porticoes noted in visual archives held at the ASR, the Archivio Segreto Vaticano (ASV), and the Museo di Roma reveal a vibrant breadth of medieval porticoes; present in Rome from the Middle Ages to the first half of the twentieth century (Fig. 20).

Fig. 20. Examples of plans of residences with façade porticoes in Rome, ASR, Confraternita della SS. Annunziata, Vol. 920 Libro delle Piante di Tutte le Case, and ASR, Libro delle Piante delle Case della Venerabile Archiconfraternita della SS. Madonna della Portico e Consolatione di Roma, 1609, and at the Archivio Storico Capitolino, Roma in Memorio Storico Artistiche della Città di Roma, (author’s drawings based on the original plans).

Renaissance Rome: The Beginning of the End of Medieval Residential Façade Porticoes

Around the mid-fifteenth century, porticoes were inserted into the new Florentine classical language with civic examples such as Filippo Brunelleschi’s Ospedale degli Innocenti. According to Guidoni, it was most likely Leon Battista Alberti and Bernardo Rossellino that brought their innovative ideas to Rome in their unexecuted design for Nicholas V’s (r. 1446-1455) new district between St. Peter’s Basilica and Castel S. Angelo. The principal organizing feature of the area was to be defined by three streets with shops on the ground floor and housing above, each lined with a continuous stretch of porticoes on either side.[81] The streets were distinguished from one another by houses, shops, and workshops that could be found along their course.[82] The street to the right had two rows of identical houses lining either side with artisans of a medium level of specialization- the central one was reserved for the highest level of artisans with homes of the same type. The third street that ran along the length of the Tiber was to have shops of different sizes for lower-level artisans.

The design would have expressed porticoes’ unifying effect on the built environment while reminding the pontiff of cities like Bologna, where he studied and served as Bishop. Nicholas V would have been particularly interested in the power of this architectural feature in providing appropriate order for his new district facing the seat of papal authority in Rome. Like his predecessor Martin V, he also sought to bring order to the city’s existing streets by limiting the construction of new porticoes without a permit and removing any obstructions they caused to the roads they flanked.[83] As Luigi Spezzaferro suggests, these efforts aimed to redefine, improve, and rationalize an existing situation in the city center instead of creating a new one, as the pope set out to do with the Borgo scheme.

The primary difference between medieval porticoes and the newly designed district for the Borgo was the attention to architectural detail and scale. Documentary sources of the period, such as Giannozzo Mannetti’s, report that the porticoes of the new Borgo scheme accommodated ample light and space, allowing safe and comfortable pedestrian passage and relief from the elements. This study identified medieval porticoes primarily situated on streets of importance during the Quattrocento, including the Via Papalis, Via dei Coronari, Via del Pellegrino, Via dei Giubbonari, and Via di Monserrato, to name a few.[84] The porticoes along these significant religious and commercial arteries differed in size and character. Variations of this specific residential type expressed the unique personalities of their owners.[85] On the other hand, the porticoes designed for the Borgo worked together as a unified urban gesture expressing the goals of an individual patron—in this case, Nicholas V.[86]

Later in the fifteenth century, Stefano Infessura reported an event in Rome following a cavalcade through the streets during the state outing of King Ferrante of Naples in 1475. After visiting Rome’s most famous monuments and churches, the king remarked to Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1471-1484) that he would never control the city until the porticoes, projecting loggias, and other obstacles rendering the streets too narrow to defend were removed.[87] However, this account does not mention the necessity of eliminating porticoes built within legitimate property lines. Infessura commented that the pope heeded the king’s advice and enforced demolitions.[88]

Sixtus IV is known for transforming the urban character of fifteenth-century Rome through numerous public works and is often referred to as Urbis restaurator et Urbis renovator. He widened the via Papalis, one of the city’s most notable processional routes and desirable streets, for the 1475 Jubilee. The famed street passed through the center of the abitato from east to west, connecting Saint Peter, the Capitoline Hill, and the Basilica of Saint John Lateran, the city’s three most important centers of religious and secular power. It was ‘the pope’s street,’ the historical route that the pontiff traversed after being elected, in the observance of the ‘possesso,’ and during ceremonies relating to the display of relics, official visits, and his general movement through the city.[89] In 1480, Sixtus IV imposed legislation that allowed the expropriation of private property for the public good and the demolition of porticoes.[90] As we have seen, not all of the porticoes in the city were demolished at this time. Especially those situated along the via Papalis, albeit a significant number were eventually immured. David Friedman’s study of the relationship between the palace and the street at the beginning of the Renaissance notes the fundamental changes between individual buildings and the avenues and piazzas they flanked. He finds the concept of the Renaissance ‘Façade’ signified a new relationship between buildings and the city, which was markedly different from the Middle Ages.[91] Based on Friedman’s finding, Sixtus IV’s new legislation was in step with urban and architectural changes occurring in other Italian cities like Florence, Siena, and Rome’s neighbor, Viterbo. Contemporary urban regulations in such cities also witnessed the demolition of projecting elements such as jetties and balconies from private properties onto public spaces. These demolitions resulted in an ever-increasing interest in widening and straightening streets.[92]

Many existing walled-in porticoes identified in this study, coupled with those found in the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century notary documents and property archives at the ASR, reveal numerous porticoes along the Via Papalis. These porous structures began at the Ponte Sant’Angelo with the Casa Bonadies, followed by another on Via del Governo Vecchio, 76, then Palazzo Bonadies Lancellotti at Via di S. Pantaleo, 34. One structure, now demolished, was located on the site currently occupied by the Palazzo Braschi, where the Orsini family once owned a property.[93] The medieval Palazzo Massimo, now occupied by the sixteenth-century redevelopment of the family’s palace, was also faced with a portico, as was their neighbor’s, the Palazzo della Valle (still visible). The palaces of the Cuccinis, Cosciari, and Pichi (all destroyed) were also identified as having porticoed façades.[94] The choice of the Massimo family to incorporate a portico along the façade of their sixteenth-century palace was deliberate. It was a visual reminder of the once prevalent architectural feature intimately associated with native Romans and the families that had made their wealth in the city as merchants. Sixtus’s urban policies demonstrated the extent of papal authority over the city while at the same time underlining his capabilities to limit the power of Rome’s local nobility, whose visible presence he gradually erased from Rome’s streetscape.[95]

By mapping these residences, it appears their distribution is far from random. Historical cartography and documentary evidence reveal that this housing type frequently appears along significant streets that have persisted from antiquity to today. These include the Via Recta (present-day Via dei Coronari), Via Papalis, Via Peregrinorum, Via Maior Arenule, Via Aurelia, Via Portuense, Via Salaria Vetus, Via Suburrana/Argelitum (present-day Via della Madona dei Monti). These streets, in particular, marked not only ancient thoroughfares but also papal processional and pilgrimage routes, making them ideal spots for commercial activity in the center of Rome. Examining these buildings within their urban environment allows one to repopulate the city of Rome in the Middle Ages and the architecture that framed the everyday life of the working class and even the city’s nobility. The watercolors produced by Maria Barosso and drawings of Carlo Dottarelli of the demolitions of residences in Rome from the 1920s-1940s provide further details of medieval porticoed houses that continued to survive discretely in the city’s historic center. The buildings captured in these images demonstrate that many porticoed complexes existed in the rione Campitelli near the base of the Capitoline Hill and in rioni Monti and Ponte. These images offer a fleeting glimpse of the extent of built heritage lost when there was little interest in preserving medieval structures (Figs. 19-20). Barosso and Dottarelli worked with a larger group of artists including Pio Bottoni, Orfeo Tamburi, Lucia Hoffmann, Vito Lombardi, Lucillio Cartocci, Giuseppe Fammilume and others. They were commissioned by the Ripartizione per Antichità e Belle Arti del Governatorato di Roma to produce a series of paintings, designs, and photographs documenting the Capital’s extensive urban and architectural transformations from the 1920s-1940s.

Fig. 21. Maria Barosso (1879-1960), Demolition of medieval houses between Via Cremona and Via delle Chiavi d’Oro, 1932. Museo di Roma-Gabinetto delle Stampe, MR 2491.

Fig. 22. Maria Barosso (1879-1960), Demolition of the so-called house of Sixtus IV on Via Alessandrina, 1929. Museo di Roma-Gabinetto delle Stampe, MR 256.

Fig. 23. Carlo Dottarelli (1897-1959), Via dei Coronari e Via di San Salvatore in Lauro and Via dei Coronari during the demolitions, 1940. Museo di Roma-Gabinetto delle Stampe, MR 9272.

This paper focuses on one specific medieval residential building type. It provides the first comprehensive study of the use of residential façade porticoes in medieval Rome and their relation to the city’s working class. Moreover, it demonstrates the importance of porticoes and their use across a broad spectrum of Roman society, which included its aristocracy, local saints, and the working class. Their use along the surfaces of civic and religious buildings of the era underlines the significance of their presence in daily life throughout the Middle Ages. This study contributes to our present-day understanding and visualization of the historic urban landscape of the Eternal City. It identifies the role of the working class in their contribution to the city’s urban character through reliance on a distinctive architectural feature similar to those painted by Lorenzetti in his fresco cycle. At the onset of the Renaissance, the dissolution of the construction and use of residential porticoes permanently altered Rome’s social and cultural relationship with semi-public space and the streets these residential buildings flanked.

APPENDIX A

| RIONE | ADDRESS | TYPE |

| I. MONTI | ||

| 1. | Via della Madonna dei Monti, 67, 68, 69 | II. Arcuated |

| II. TREVI | ||

| 2. | Piazza Fontana di Trevi, 92 | I. Trabeated |

| 3. | Piazza Fontana di Trevi, 95 | I. Trabeated |

| IV. CAMPO MARZIO | ||

| 4. | Piazza Campo Marzio, 5-6 | I. Trabeated |

| V. PONTE | ||

| 5. | Palazzetto “Albergo dell’Orso,” Via dei Soldati, 25 | IV. Townhouse |

| 6. | Via dell’Orso, 11 | IV. Townhouse |

| 7. | Casa di Fiammetta, Vicolo di San Trifone, 1 | II. Arcuated |

| 8. | Palazzetto Lancellotti, Via Maschera d’Oro, 9 | Unclassified |

| 9. | Via dei Coronari, 220 | Unclassified |

| 10. | Palazzetto dell’Arciconfraternita di S. Maria dell’Orto, Via dei Coronari, 17, 18 | |

| 11. | Casa di Fiammetta, Via dei Coronari, 156-157 | IV. Townhouse |

| 12. | Via Arco della Pace, 10 | IV. Townhouse |

| 13. | Piazza del Fico, 29 | Unclassified |

| 14. | Casa Bonadies Via del Banco di Santo Spirito, 61 | I. Trabeated |

| VI. PARIONE | ||

| 15. | Via del Governo Vecchio, 76 | Unclassified |

| 16. | Via di S. Pantaleo, 62 | |

| 17. | Vicolo Savelli, 32 | II. Arcuated |

| 18. | Via del Pellegrino, 168 | Unclassified |

| 19. | Via del Pellegrino, 53 | I. Trabeated |

| 20. | Arco di S. Margherita, 21 | Unclassified |

| 21. | Via dei Giubbonari, 64 | I. Trabeated |

| VII. REGOLA | ||

| 22. | Via Capo di Ferro, 31 | I. Trabeated |

| 23. | Case di S. Paolo, 1 | III. Tower house |

| 24. | Case di S. Paolo, 2 | II. Arcuated |

| 25. | Case di S. Paolo, 3 | II. Arcuated |

| 26. | Case di S. Paolo, 4 | II. Arcuated |

| 27. | Case di S. Paolo, 5 | II. Arcuated |

| 28. | Case di S. Paolo, 6 | II. Arcuated |

| 29. | Case di S. Paolo, 7 | III. Tower house |

| 30. | Via di S. Maria in Monticelli, 61 | Unclassified |

| VIII. SANT’EUSTACCHIO | ||

| 31. | Palazzo della Valle, Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 101 | II. Arcuated |

| 32. | Via di S. Anna, 68 | Unclassified |

| 33. | Casa di Boccamazza-Torre del Papito | II. Arcuated |

| 34. | Palazzo Ginnasi, Via dell’Arco de Ginnasi, Largo di Santa Lucia Filippini, 5 | I. Trabeated |

| X. CAMPITELLI | ||

| 35. | Vicolo Margana, 12a | Unclassified |

| 36. | Casa della Porta, Vicolo Margana, 14 | |

| 37. | ||

| XI. SANT’ANGELO | ||

| 38. | Casa e Torre del Margani, Piazza Margana, 40 | III. Tower house |

| 39. | Via del Teatri di Marcello, 2 | II. Arcuated |

| 40. | Via del Teatro di Marcello, 18-20 | Unclassified |

| 41. | Palazzo Monastero della Oblate di Tor de’Specchi, Via del Teatro di Marcello, 34 | Unclassified |

| 42. | Palazzo Patrizi (Clementini), Via dei Funari at Piazza Lovatelli | Unclassified |

| 43. | Palazzo Delfini, Via dei Delfini, 16 | Unclassified |

| 44. | Via dei Delfini, 8/9 | II. Arcuated |

| 45. | Via Tribuna di Campitelli, 23, | II. Arcuated |

| 46. | Via Tribuna di Campitelli, 23 B | II. Arcuated |

| 47. | Casa dei Vallati, Via del Portico d’Ottavia, 29 | II. Arcuated |

| 48. | Albergo della Catena, Via del Foro Piscario | II. Arcuated |

| XIII. TRASTEVERE | ||

| 49. | Via della Lungaretta, 160, 161 | II. Arcuated |

| 50. | Vicolo della Luce, 57 | II. Arcuated |

| 51. | Via di S. Bonosa, 22 | I. Trabeated |

| 52. | Vicolo della Atleta, 23 | Unclassified |

| 53. | Piazza di S. Cecilia, 19 | II. Arcuated |

| 54. | Via della Renella, 42 | II. Arcuated |

| 55. | Via della Scala, 5 | II. Arcuated |

| 56. | Casa della Fornarina, Via di Santa Dorotea, 20 | IV. Townhouse |

APPENDIX B

| RIONE | DESCRIPTION | SOURCE |

| I. MONTI | ||

| 1. | House on Via Madonna dei Monti. House with three columns along the facade. Portico enclosed on sides open along the street | ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, Libro delle Case, Vol. 1281, 031r, 1609. |

| 2. | House on Via Madonna dei Monti n. 75-79. Immured portico. With one column visible along the facade | ASR, Trenta notai capitolini-Ufficio 06 Segnatura: 632-1/1, August, 1849. |

| 3. | House on Via dell’Agnello. House with three columns along the façade open at the front and the sides. Portico projects beyond the property lines onto the street | ASR, Trenta notai capitolini-Ufficio 06 Segnatura: 632-1/1, August, 1849. |

| 4. | House in the Hemicycle of the Markets of Trajan | Archivio Segreto Vaticano, See reproduced plan in Roberto Meneghini, “I Fori Imperiali nel Quattrocento Attraverso la Documentazione Archeologica,” 211. |

| 5. | House on Via Alessandrina, 110 | See photographs, and watercolors of the house in the Collection of the Comune di Roma. Maria Barosso, Watercolor, 1929 See MR 256. See also Cesare Faraglia, Photograph, 1929, AF 19588. See also the elevation reproduced in Meneghini, “I Fori Imperiali nel Quattrocento Attraverso la Documentazione Archeologica,” 212. |

| 6. | House on Via della Madonna dei Monti, part of the Cenci family block and tower | Historic Views of Rome: Codex Escurialensis, Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1490. |

| 7. | House near Magna Napoli. Walled in Portico | ASR, Confraternita di San Salvatore, Ospedali, San Salvatore, 27. See also Henri Broise and Jean-Claude Maire Vigueur, “Strutture famigliari, spazio domestic e architettura civile a Roma alla fine del Medioevo,”132. |

| 8. | House near Magna Napoli. Four columns with portico open on front and sides. Projects beyond property lines onto the street | ASR, Confraternita di San Salvatore, Ospedali, San Salvatore, 32. Plans reproduced in Broise and Maire Vigueur, “Strutture famigliari, spazio domestic e architettura civile a Roma alla fine del Medioevo,” in Storia dell’Arte Italiana. Momenti di Architettura, 1983, 132. |

| 9. | An account made on 1 January 1422 discusses two neighboring houses with butcher shop counters in a portico in rione Monti.

|

Archivio Storico Capitolino (ASC), Notarile, Sez. I, 785 bis/8, cc. IIIv-Viv. notaio Nardus Pucci de Venectinis. See Anna Modigliani, “Artigiani e Botteghe nella Città,” in Alle Origini della Nuova Roma, 460. See also Modigliani, Marcati, Botteghe e Spazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 78. |

| V. PONTE | ||

| 10. | 22 October 1468 the nobleman Mattia de Normandi of rione Colonna sold to a tailor in rione Ponte the ground floor of a house on the via Recta near Monte Giordano that included a bedroom, a kitchen and part of a colonnaded portico on the façade. | ASR, Coll. Not. Cap., 1763, cc. 145r-146r, ad annum. See also Modigliani, Marcati, Botteghe e Spazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 227. |

| 11. | 1401, a house with two rooms (sale), bedrooms (camere), portico, market stands (banche), and cantina (basement) was rented to the Florentine merchant Lucas Nycolai at Canale di Ponte near the bridge of Sancti Petri. | Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (BAV), Vat.lat. 2664, cc. 3r-10v. See also Modigliani, Marcati, Botteghe e Spazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 129. |

| VI. PARIONE | ||

| 12. | Bottega in Palazzo Orsini at the Pasquino, present day Palazzo Braschi | ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, Libro delle case, Vol. 1281, 156r, 1609. |

| 13. | House on Via dei Cappellari belonging to Giovanni Battista Spetia and Giacomo Muti, façade facing Via dei Cappellari. Portico closed at the sides and open along the street. | ASR, Confraternita della SS. Annunziata, Libro delle Piante di Tutte le Case, Vol. 920, 24r, 1563. See also same plan represented in ASR, Confraternita della SS. Annunziata, Libro delle Piante di Tutte le Case, Vol. 921, 74r, 1636. |

| 14. | House with a bakery on Via di Parione and the Vicolo that goes to Via alla Pace and del Fico | ASR, Ospedale di SS. Salvatore ad Sancta Sanctorum, 385, c. 91r. See also Anna Modigliani, “L’Approvvigionamento Annonario e i Luoghi del Commercio Alimentare,” 58. |

| 15. | 1365-1525 House or colonnaded palace also referred to as a merchant’s warehouse on Campo de’ Fiori | BAV, Archivio del Capitolo di S. Pietro, case e vigne, 19. Parione c. 14-v; Censuali, 4, 1416, c. 29v; Censuali 4, 1422, c 35v; Censuali, 4, 1436, c. 10r.). See also Anna Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 216-217. |

| 16. | Spice Shop, 1365. House on two floors with a portico on the front and a vegetable garden behind and a well. Located in the area of San Lorenzo in Damaso and Campo de’ Fiori rented to the spice merchant Stefanello di Cecco Vangoli. | See Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 217.; See also Il Protocollo notarile di “Anthonius Goioli Petri Scopte,” 157-159. |

| 17. | January 6, 1407, A house with a portico that had a delicatessen, of which the confines are not clear belonged to Petris Lelli Iohannis Pauli | ASR, Coll. Not. Cap., 848 cc. 124v-125r. See Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 218. |

| 18. | The house of the Società del Salvatore was rented to the shoemaker Lellus Nucii for 6 fiorini a year. The two storied house had a portico along its façade. | ASR, Ospedale del SS. Salvatore ad Sancta Sanctorum, 381, c. XXXIIIr). Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 221. |

| 19. | A casa-bottega with a butcher shop, on the ground floor with a portico on the front that the barber Martinus Fuscini rented to the butcher Marcello Corsini from Firenze and to Domenico di Lorenzo de Portico de Romagna. 29, December 1424 | ASR, Coll. Not. Cap., cc. 268r-v. See also Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 223. |

| 20. | A casa-bottega with two floors, rooms, a portico and a well in Campo de’ Fiori, rented to a spice merchant and used as a spice shop. | ASR, Coll. Not. Cap., 848, cc. 206v-207r. and c. 189v, 1412. See Modigliani, Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 182. |

| VII. REGOLA | ||

| 21. | Via S. Bartolomeo degli Strengari, 29. | Identified by photographs and Richard Krautheimer in Rome Profile of a City, 312-1308, 295. |

| 22. | House of Saint Bridget at the corner of Piazza Farnese, at the present Vicolo del Gallo and Via di Monserato | A. Anderson, La casa e la chiesa di Santa Brigida nella storia, 14. |

| 23. | Medieval Portico Underneath Palazzo Farnese | See Broise and Hanoune, “Eléments Antiques Situés Sous le Palais Farnèse,” 738. |

| 24. | Palazzo Alberteschi | See Rosella Motta, “Note Sull’Edilizia Abitativa Medioevale a Roma,” 32. |

| IX. PIGNA | ||

| 25. | House on Via Palombella | ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, Libro delle Case, n. 1281, 157r., 1609 |

| VIII. SANT’ EUSTACCHIO | ||

| 26. | Rental agreement made in 1412 of a house belonging to Caterina, the wife of Paolo Catangnia (De Calvis) in rione S. Eustachio, with a portico on the façade | ASR, Coll. Not. Cap., 848, cc. 248r-249r. See also Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 223. |

| 27. | A house (terrinea et solarata) with a façade portico in rione S. Eustachio was rented in 1365 for an annual price of only 10 soldi (coins). | See Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 50 |

| X. CAMPITELLI | ||

| 28. | House of Cristoforo Ardicio near Tor de’Specchi n. 30 | ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, Libro delle Case, n. 1281, 263 r, 1609. |

| 29. | House A on Via della Pedacchia | Memorie Storico Artistiche della Città di Roma I: Plan of houses A, B, and C on Vie di S. Marco and Via della Pedacchia (Roma: Casa Virgino, 1902. |

| 30. | House B on Via della Pedacchia and Via di S. Marco | Memorie Storico Artistiche della Città di Roma I: Prospetti Sulle Via di S. Marco n. 12 (Roma: Casa Virgino, 1902. |

| 31. | House C. Via di S. Marco | Memorie Storico Artistiche della Città di Roma I: Prospetti Sulle Vie di S. Marco n. 10 and 11 (Roma: Casa Virgino, 1902. |

| 32. | 1493 a two storied house with a façade portico and a marble stone under the same portico in rione Campitelli was rented to a barber “in foro sive mercato” next to the stairs of Aracoeli. | ASR, Coll. Not. Cap., 927, cc. 154r-v and 175 r-v, notaio Iohannes Baptista de Iaiis. See also Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 87. |

| 33. | House facing the market piazza in rione Campitelli, sold by Margherita to the roman goldsmith Petrus Tramundi for the price of one hundred gold florins “unam domum…terrineam, tegulatam et solaratam cum lovio ante se discoperto et porticali ante se et cum certis locis sive statiis existentibus ante dictam domum, super quibus venduntur vasa terrinea ea die qua fit forum, de quibus statiis sive locis unus sive unum vadit usque ad duos lapides fisos in terries inter alios lapides ante domum Neapuleoni Bucciaroni seu Bucciaroni eius filii, sitam in regione Campitelli in contrata Mercati, in parocchia S. Iohannis de Mercato, inter hos fines: ab uno latere tenet Petrus Tramundi aurifex, ab alio latere tenant heredes quondam Iacobelli Crapoli, ante et a latere sunt vie publice.” | ASR, Ospedale del SS. Salvatore ad Sancta Sanctorum, cass. 509, arm. VIII, mazzo VII, n. 5. See also Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 46. |

| 34. | 3 October 1474 Lorenzo Margani sold to his sister-in-law Caterina, wife of his brother Ludovico, a tinello (dining room) under the house where the same Ludovico resided with half of the portico on the façade. | ASR, Ospedale del SS.mo Salvatore ad Sancta Sanctorum, cass. 467, arm. V, mazzo IV, n. 55. See also Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 47. |

| 35. | A house with a portico belonging to the Società del Salvatore in 1410 was subdivided into four parts. The notary described the subdivision as “secundum vero locum dictorum porticcalium…videlicet a secunda trabe usque ad. tertiam” | ASR, Ospedale del SS. Salvatore ad Sanctorum, 381, cc. Lv-Lr. See also Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 48. |

| 36. | 13 September 1305 a deed of sale made by the spice merchant Andrea di Pietro Mellini to Giovanni di Giovanni Margani for a house solerata with a portico comprised of three columns along the façade for a price of 170 gold fiorini. The house that was in the contrata Mercati, was adjacent to the property of Giacomo di Nicola Margani | ASR, Ospedale del SS. Salvatore ad Sancta Sanctorum, cass. 467, arm. V, mazzo IV, n. 37. See Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 51 |

| 37. | House at the corner of present day Via dei SS. Quattri and Piazza del Colosseo | Nuova Pianta di Roma, Giovanni Battista Nolli, 1748 |

| XI. SANT’ANGELO | ||

| 38. | House located on the street that leads to the gate of the Ponte Quattro | ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, n. 1281, Libro delle Case, 237r, 1609 |

| 39. | Casa Modigliani, Via di Pescheria n. 66-68 near the Portico di Ottavia | ASR, Archivio del Comune e Pontificato 1847-1870, 09 Febbraio 1866-12 Maggio 1866. |

| 40. | House on Vicolo Passattore del Torretto, on the site called Porticale. Filippo Prioni, architetto delle strade, deputato per rione. S. Angelo | ASR, Archivio dei Notai delle Acque e Strada della R.C.A., VOL. 148, c. 750 |

| 41. | Medieval houses demolished between Via Cremona and Via delle Chiavi d’Oro, 1932, | Museo di Roma, Maria Barosso, Watercolor, 1932, MR 2491 |

| 42. | House on Via Marforio, Forum of Caesar, demolished 1931 | Museo di Roma-Archivio Fotografico (1931), AF 22035 |

| 43. | House on Via Rua, photographed between 1888-1900 | Museo di Roma-Archivio Fotografico (post-1888, pre-1900), AF 3167 |

| 44. | On the piazza next to the church of S. Leonardo there was at the beginning of the Quattrocento a two storied house with a portico and a mignano (external balcony) on the front, that the spice merchant Iohannes Nini of rione Ponte donated to the Società del Salvatore, that was then rented to an ironworker. | ASR, Ospedale del SS.mo Salvatore ad Sancta Sanctorum, 381 (catasto del 1410), c. LVIr. See Modigliani, Mercati, Botteghe e Sapazi di Commercio a Roma Tra Medioevo ed Età Moderna, 170. |

| XIII. TRASTEVERE | ||

| 45. | House at the Ospedale di Genovesi on the other side of building on Via Anicia | ASR, Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione, Libro delle Case, n. 1281, 400r 1609 |

References

| ↑1 | The same terminology is used to describe these architectural elements in the historic property records housed in the Archivio di Stato di Roma’s (ASR) Libro delle Case of SSma Annunziata, Vol. 920 (1563), and Vol. 921. (1636), and those found in the Libro delle Case of Ospedale di S. Maria della Consolazione Vol. 1281 (1609), and Vol. 1283 (1726). |

|---|---|