Marian Bleeke • Cleveland State University

Recommended citation: Marian Bleeke, “He was a Manly Man, to be an (Arch)Bishop Able: Transi tombs and Masculinity in Fifteenth-Century England,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/YASF9916.

Rachel Dressler’s work on English knights’ effigies from the thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries broke new ground both in the study of medieval tomb sculpture and that of gender in medieval art. Prior to her work, scholarship on tomb sculpture had been dominated by Erwin Panofsky’s 1964 publication on tombs from ancient Egypt through to the Renaissance, which was shaped by two oppositions that functioned as teleologies. The first of these was between tombs with a “prospective” and those with a “retrospective” function; that is, between sculptural programs focused on the fate of the soul after death and those focused on the life of the deceased. A shift from the first of these to the second was supposed to demonstrate the transition from medieval religiosity to a Renaissance celebration of the individual.[1] Dressler’s work broke from this model in that, while recognizing that the tombs she wrote about served “prospective” functions in soliciting prayers for the dead, she emphasized their engagement with this-world concerns – specifically their construction and promotion of the deceased’s identity as knights in the face of uncertainty around the definition of knighthood.[2]

As part of this argument, Dressler highlighted the strikingly three-dimensional forms of the effigies she studied, thus breaking from the second of Panofsky’s oppositions-as-teleologies, between two and three-dimensional forms as demonstrating sculptors’ increasing mastery of their craft.[3] For Dressler, the knights’ effigies’ three-dimensionality was meaningful in that it presented their bodies as “powerful,” “robust,” “brawny,” and “vigorous,” and so marked a difference between them and both women and other types of men, specifically kings and clerics, whose effigies are dominated by heavy draperies that conceal the bodies beneath them.[4] In Dressler’s argument, these visual differences worked to construct social differences, in particular that of gender, with the differences between the knights’ effigies and those of women producing the distinction between masculinity and femininity and those among men’s effigies complicating the category of masculinity.[5]

This article expands on Dressler’s work by looking at a different group of tombs, made for a different group of men, at different moments in both the history of masculinity and the study of medieval masculinities. My interest here is in transi or cadaver tombs; that is, tombs that incorporate a sculpture of the deceased as a decaying corpse. This type of tomb appears in multiple times and places where it was used for different types and groups of people and so seems to have carried different meanings: for example, I have written elsewhere of a group of transi tombs built for French kings and queens in the sixteenth century in relationship to concerns about the continuity of the Valois line.[6] Here I am interested in transi tombs from England in the 1400s: at least seventeen such tombs have survived in whole or in part or were documented prior to their destruction.[7] Most were made for men, with three made as monuments for married couples and one for a woman, Alice Chaucer, the Duchess of Suffolk. Her tomb differs from the men’s in ways that will be discussed below. Most of these tombs are two-story monuments that have an effigy (or effigies in the case of couples’ monuments) laid out on the upper story and the transi (or transis) enclosed in the lower level.[8]

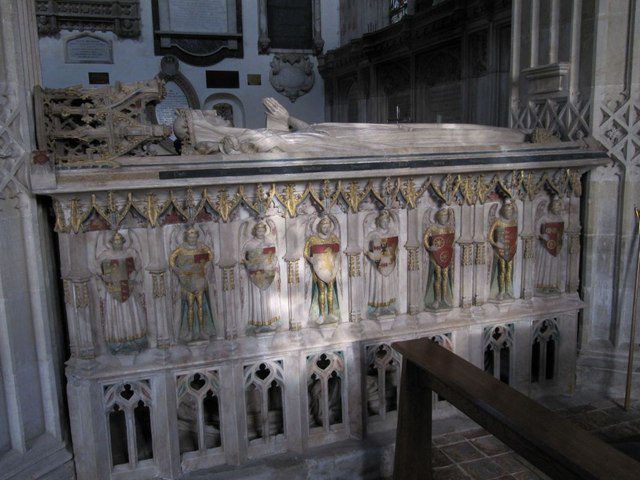

Figure 1. Tomb of Richard Fleming, Lincoln Cathedral. Photo: author.

The exceptions include a monument for John Baret that will also be discussed in detail below. Monuments with a single transi sculpture seem to have become more popular in the 1500s, suggesting a change of some sort in the way in which the transi form was understood, which is why I have limited this article to examples from the 1400s.[9]

The men memorialized in these tombs include nine members of the clergy, namely, Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury; William Derby, rector of Terrington St. Clement; Richard Fleming, Bishop of Lincoln; John Careway, rector of St. Vigors, Fulbourn, Cambridgeshire; William Sponne, Archdeacon of Norfolk; Thomas Beckington, Bishop of Bath and Wells; either William or Laurence Booth, both Archbishops of York; John Carpenter, Bishop of Worcester; and Thomas Heywood, Dean of Lichfield Cathedral. And the group also includes seven lay men, buried both singly and with their wives: John Fitzalan, John Golafre, John Baret, Sampson Meverell, John Denston, Richard Willughby, and John Barton. These tombs thus raise as a question the relationship between clerical and lay forms of masculinity, a relationship that has been a focus for scholarship on medieval masculinity in the twenty years since Dressler’s work was originally published.[10] I argue that these tombs give visual form to aspects of masculinity that were shared by these two groups of men in this time and place, in particular the values placed on the “true” man and on sexual self-control.

Masculinity and Truth in Later Medieval England

Derek Neal has argued that truth was a key term in defining proper masculinity in later medieval England. In looking at defamation cases in diocesan courts, he identifies “thief” as a common underlying insult and so as both a common accusation among men and one that men found serious enough to bring to court for redress. In examining these court cases and other evidence, Neal argues that “thief” as an insult did not simply imply theft but also suggested deceit and deception. All thieves were by implication sneak thieves.[11] That understanding of theft and its relationship to masculinity come through in a letter from Margaret Paston to her husband, dated to 1448, where she warns him against an enemy by writing “I know well he will not set upon you manly, but will start upon you or some of your men like a thief.”[12] The implication here is that a manly or properly masculine attack would be an open one and that is opposed to an unmanly thief-like attack that will be sneaky, hidden, or deceptive in some way. In Neal’s account, this understanding of thief is sometimes made explicit by the addition of “false” and false could be added to other insulting terms: a man could insult another man by calling him a “false thief,” “false harlot,” “false extortioner,” or “false heretic” and that man could feel sufficiently insulted to bring a case court to defend himself. The emphasis on falseness in defamation cases highlights the importance for men of being regarded as “true,” understood as being open, honest, loyal, and faithful.[13]

Neal cites another letter, written in 1478, that again demonstrates the importance of truth for and among men through its opposition to thievery and falseness and introduces another term for the latter: that of a “double” man. This letter was written by Edward Hampden to Sir William Stonor to defend Hampden’s servant against an accusation of theft made by Harry Gorton and repeated by Stonor. Hampden writes “I would advise Harry Gorton to hold his tongue there, and have a worse tale proved on him, or else you may say that I am false” and “I heard that you called him a thief: by my truth, I do not know him as one, nor would I ever keep one.” And he adds “It amazes me that such a worshipful man as you would slander any poor man, for the words of such a ‘double’ man as Harry Gorton.”[14] As Phillipa Maddern points out, the idea of the “double” man also appears in the Paston family materials, as Friar John Brackley in a letter from 1460 quotes a common saying: “A man schuld not trustyn on a broke swerd, ne on a fool, ne on a child, ne on a dobyl man, ne on a drunkeman.”[15] Within the corpus of the Paston letters, “doubleness” is opposed to the idea of “oneness” in a letter from 1459 where Friar Brackley reports that John Falstoff praised John Paston I as “a feythful man and ever on man.”[16] Maddern explains that “oneness” here referred to a match between a person’s inward intentions and their outward actions, which was becoming a new standard for honorable behavior.[17] The inner and outer would be split in a “double” man, who might say or do one thing while intending something else. Neal likewise argues that “true” manliness involved a “manifest veracity” and “uncomplicated honesty” in which the “surface meaning is the only meaning.”[18] To that end he cites another Paston letter, written in 1460 by Elizabeth Clere, where she compares a man who had spoken ill of her and was seeking her forgiveness to a thief and describes him as using “untrue language” and “many crafty words.”[19]

Finally, Neal’s evidence also shows truth to have been at issue in disputes between members of the clergy and between them and lay men and women. In a defamation case from 1512, one priest was accused of saying to another “You are a false priest and a false flattering priest and a false tale teller.”[20] In two disputes, one from the 1490s and another from the 1510s, two different priests were defamed by laymen by being called “thief” with its implications of sneak-thievery, craftiness, and so falseness.[21] Likewise, in still other disputes, Richard Belby, the vicar of Winthorpe, accused Alice Birdhall of calling him a “false thief” and she admitted to calling him “an untrue priest,” and Robert Butte denied calling Robert Hardyng a “false crafty priest” and claimed to have only said that he “crafted my farmhold from me.”[22] Thus the value placed on truth by and among men crossed over the boundary between lay society and the clergy.

Truth in Transi Tombs

Concerns about truth or “honesty” also surrounded the production of tombs in fifteenth-century England. Nigel Saul cites multiple primary sources from the period in which men request “honest” memorials monuments for themselves and women request them for male relatives. Saul argues that honesty held two meanings in this context: it referred to the quality of the workmanship that went into the memorial and to the memorial as properly representing the deceased’s social status.[23] On another level, the idea of the “double” man from the discourse around true masculinity recalls the double-decker structure of most of the transi tombs under discussion here, which host two images of the deceased – the effigy above and the transi below and inside of the monument. In most cases, the two images are meant to represent the same individual, thus giving him a doubled form. The exceptions to the latter rule are two of the monuments to couples, those for Richard Willughby and his wife and John and Isabella Barton, that pair effigies for both husband and wife with a single transi; these two tombs will be discussed in more detail below.

For Panofsky in his work on tomb sculptures, the double-decker structure of these tombs and the presence of two images of the deceased was a reference to the idea of the “king’s two bodies,” as elucidated in Ernst Kantorowicz’s book of that title. In this reading, the effigy would represent the undying “dignity” or office the man held in his lifetime – as archbishop, bishop, or earl – while the transi below would represent the man himself as mortal and so subject to death and decay.[24] It was Kantorowicz himself who first linked this tomb type to his distinction between the “two bodies,” through the use of an effigy in funeral rituals to represent the immortal “body” of the dignity or office in contrast to the actual body of the deceased. An effigy was used in this way during the funeral of Edward II in 1327 and Henry Chichele’s funeral likewise featured an effigy placed on top of the coffin that contained his body. Thus, for Kantorowicz, Chichele’s two-story transi tomb was a “realistic representation of reality, rendering simply what was seen at the funerary procession: the effigy in regalia on top of the coffin which contained the almost naked corpse.”[25] Kathleen Cohen points out one problem with this understanding of Chichele’s tomb: that the tomb was constructed prior to his death and so cannot have been predicated on what happened at his funeral. However, it could have been modeled on arrangements seen at other funerals, she writes, and she accepts that the idea for the double-decker tomb may have come from the use of effigies in funerals.[26]

And yet the arrangement that Kantorowicz describes recalls a traditional effigy tomb, not the double-decker structure of these transi tombs: in both the effigy is placed above a closed form, the coffin in the funeral or the base of the tomb, that contains and so conceals the dead body.[27] The difference in the two-story transi tombs is that the lower portion is opened up to allow the dead and decaying body to be seen in the form of the transi sculpture. What is contained and concealed in both the funeral and the effigy tomb is thus placed on display in the double-decker transi tomb. For Paul Binski, such tombs formed a visual commentary on the existing tradition of the effigy tomb, as “anti-representations” or “anti-tombs” that not only made visible what the effigy tomb had worked to erase, the dead body in the form of the transi, but dramatized that new visibility by directly contrasting the two sculptures against one another. The new visibility of the transi was further heightened, he argues, by the arches that open up the lower levels of these tombs – but only partially. He compares these archways to those on saints’ shrines, for example the shrine of St. Thomas Becket at Canterbury that would have formed a direct comparison with Chichele’s tomb, into which pilgrims would insert their limbs or their entire bodies in order to come close to the saint’s relics. In the transi tombs, he argues, physical proximity is replaced by sight and sight is both frustrated and motivated by the archways. They force the viewer to peek and peer past them to see the transi inside of the lower portion of the tomb, in contrast to the effigy laid out on the surface above.[28]

Turning attention to viewers’ experiences of the two-story tombs opens the question of how medieval viewers might have understood the juxtaposition they create between the two sculptures of the deceased. Ashby Kinch argues that the striking form of the transi sculpture would have first drawn viewers’ attention to the tombs and then the monuments would have drawn the viewers’ attention away: specifically, would have drawn it upwards to the effigy, whose open eyes would have directed the viewers’ gaze still higher. In the case of Chichele’s tomb, he argues that the goal of upwards movement was to direct the viewers towards heraldic shields in the canopy over the tomb that asserted the archbishop’s identity and status.[29] Jessica Barker traces a similar trajectory on John Fitzalan’s tomb, but with different beginning and end points. She argues that viewers would have been highly aware of the presence of his corpse in the vault under the tomb since it was moved there during a reburial service in 1454 (he was originally buried in France after dying there fighting for Henry VI) and that the effigy would have suggested for viewers the restoration of his body at the end of time. The transi, then, would have represented a state in-between the corpse and the resurrected body. She points to a prayer used in the reburial service that sketches out such a trajectory: “to bind together truly dry bones with sinews, to cover them with skin and flesh, and to put into them the breath of life.”[30]

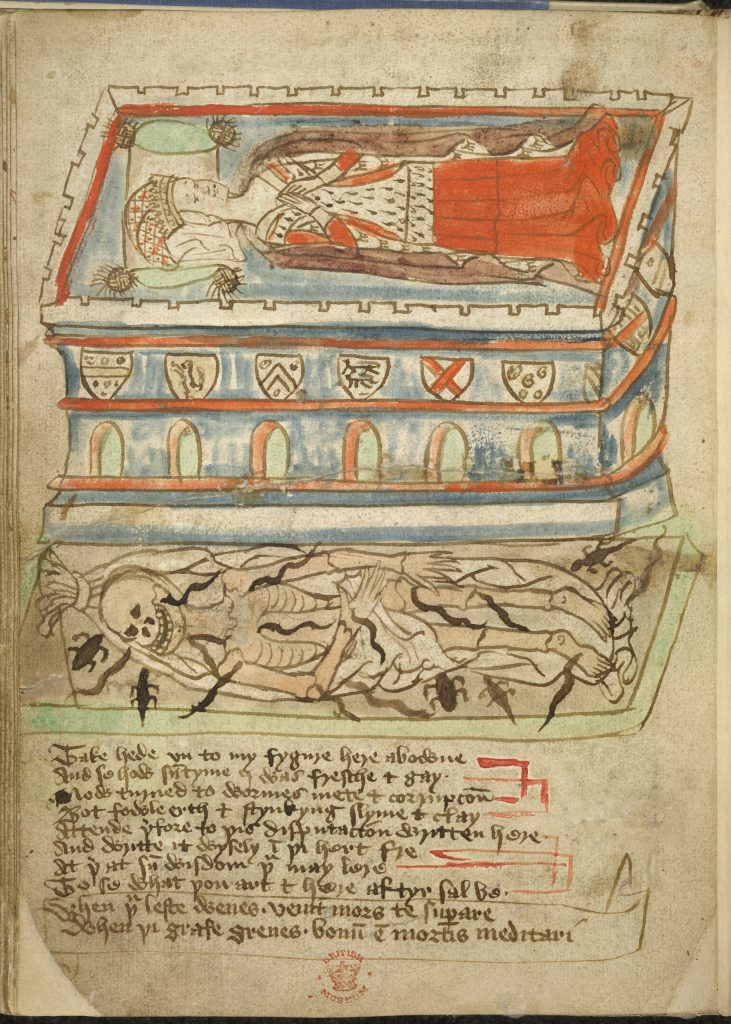

However, Panofsky, Cohen, Binski, and Barker all point to another medieval source that suggests a different trajectory for viewers encountering a double-decker transi tomb, one that leads downwards, into the grave. Images in a manuscript from the 1460s or 1470s known as the Carthusian Miscellany (British Library Additional MS 37049), accompanying the poem “A Disputation Between the Body and the Worms,” show effigy tombs of an emperor and a lady juxtaposed with images of each as a dead body decomposing in the grave.

Figure 2. Effigy tomb and open grave from “A Disputation Between the Body and Worms.” Carthusian Miscellany, northern England (c. 1460-70). © British Library Board. British Library Additional MS 37049, f. 32v.

While these are not images of two-story transi tombs, they are as Panofsky and Binski state, “optically” and “conceptually” similar forms.[31] The miniatures are spatially complex, as Barker writes, with the effigy monuments seeming to “hover” in space above the graves and the graves tilted forward to present the decomposing bodies to the viewer’s gaze.[32] There is a sense in these images of the tomb having been pushed aside in order to reveal the grave beneath it and with that to reveal the truth of death as bodily decay and dissolution, a truth that the effigy tomb sought to deny. Binski identified that sense of revelation and truth-telling in the double-decker transi tombs as well, writing that they “overcame this erasure of the body by the effigy; they performed a kind of unmasking of that which had hitherto been concealed …revealed the skeleton in the cupboard of medieval funerary art, namely its denial of the facts of decomposition.”[33] Finally, the juxtaposition of the living and dead forms of the individual that is represented in these miniatures and created in the double-decker transi tombs is associated with truth-telling in the inscription on the tomb of the Black Prince (d. 1376). Although the tomb itself is an effigy monument, the inscription contrasts the Prince in life – “Great riches here did I possess whereof I made great nobleness. I had gold, silver, wardrobes and great treasure, horses, houses, land” – with him in death – “But now a poor caitiff am I, deep in the ground lo here I lie. My great beauty is all quite gone, my flesh is wasted to the bone. My house narrow and throng” – and then states that “nothing but truth comes from my tongue.”[34]

The doubling of the deceased that takes place in the double-decker transi tomb is thus again related to truth, although in a different way than in the idea of the double man in the discourse around true masculinity. In the latter, the double man is aligned with a thief and suggests deception or deceit: the doubling split of the outer from the inner man allows the outer to present a deceptive face to the world, while concealing the inner man’s intentions. The doubled man is thus false and so not a “true” or proper man at all. The double-decker form of these tombs works instead in the service of truth, as revealing the truth of death in the form of the transi’s image of bodily decomposition. To borrow terms from the discourse on masculinity for the tombs, the effigy laid out on the tomb’s upper surface could be understood as the outer man and the transi within the monument below as the inner, but here the inner is revealed in direct juxtaposition to the outer and so the tomb disallows any deception. Indeed, what happens in the transi tombs is visually a doubling but conceptually a tripling of the man: for his actual corpse forms an unseen third term. A traditional effigy tomb would thus be the deceptive doubled form, with the outward form of the effigy replacing the dead body concealed within it. The double-decker transi tombs use the transi to reveal what such tombs had concealed. By choosing to be buried in these tombs, or by having this type of tomb chosen for them by those close to them, the men who were buried in these tombs thus showed themselves or were shown to be true men. Their commitment to truth as a masculine value was dramatized by their tombs’ truth-telling about their deaths.

Tombs for a Thief, a Woman, and Three Couples

Connecting the truth-telling action of the double-decker transi tombs to the idea of the true man can shed light on two exceptional tombs mentioned above, those of John Baret and Alice Chaucer. Baret’s stands out for its structure: it is not a double-decker tomb but instead consists of a transi lying on top of a sculpted base.

Figure 3. Tomb of John Baret, St Mary’s, Bury St Edmunds. Photo: © Aidan McRae Thompson.

Rather than a full-scale effigy, it includes a small-scale image of Baret in life on its base. Chaucer’s stands out for its inhabitant: it is the only one of this group of tombs that was made for a woman on her own – otherwise women were included in the three tombs that were made for married couples.

Baret’s tomb recalls Chichele’s and Richard Fleming’s in including extensive inscriptions about the deceased, but these inscriptions differ markedly in their content. The inscription on the base of Chichele’s tomb reads “I was a pauper born, then to Primate raised/now I am cut down and ready to be food for worms/Behold my grave./ Whoever you may be who passes by, I ask you to remember/You will be like me after you die;/All horrible, worms, vile flesh.”[35] The text thus emphasizes his life’s trajectory and in particular his rise to power prior to being cut down by death. A much longer inscription on Richard Fleming’s tomb first describes his life story in some detail: his education at Oxford, his appointment as Bishop of Lincoln, and then his advancement to be Archbishop of York. From there, the inscription begins to despair: what good are all these achievements in the face of death? As with the inscription on Chichele’s tomb, the emphasis is on death’s ability to bring down the highest.[36] By contrast, the inscriptions on Baret’s tomb do not mention his worldly achievements but instead emphasize his status as a sinner and ask for God’s forgiveness: “God be kind to me, a sinner” appears on one end of the base and the transi clasps a scroll that reads “Lord, do not judge me by my deeds. Nothing I have done is worthy of your sight. Therefore I beseech your Majesty that you, God, wipe away my iniquity.”[37]

As Michael Rimmer has argued, the emphasis in the inscriptions on Baret’s tomb seems to match that of the overall structure of the monument, with the absence of a full-scale effigy sculpture likewise downplaying Baret’s status in life and the placement of the transi on the top surface of the tomb emphasizing instead his death and decomposition. Rimmer argues that Baret’s tomb shows his guilt over his actions towards another man, Edmund Tabour, in his execution of Tabour’s will. Baret apparently stole silver from Tabour’s estate and used it to make one of his Lancastrian collars.[38] Baret was thus not true in his actions towards Tabour but instead acted as a false thief. Concerns around this type of deceptive behavior were common at the time and again brought concerns about truth and falseness to bear directly on tomb monuments: Saul cites a few lines of verse that appeared on multiple memorial brasses: “For widows be slothful, and children beth unkind, executors be covetos, and kepal that they find.”[39] Baret’s guilt over his actions is apparent in his will as he made provision for masses to be said for the “soulys of whoos bodies I have caused to lese (lose) sylvir” and for Tabour’s soul specifically. That guilt may also be expressed in the form of his tomb that does not use the double-decker form with its implications of truth-telling and truthfulness.

While Alice Chaucer’s monument is a double-decker transi tomb, it differs from the others in its structure and its effect. Below her effigy sculpture, instead of an open arcade, the side of her tomb has a solid surface made up of sculpted figures holding shields.

Figure 4. Tomb of Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk, Church of St Mary the Virgin, Ewelme.

Photo: Bill Nicholls, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 license.

Only at the very bottom of the tomb’s side walls are there openings, shaped like windows with interior tracery. The result is that the transi sculpture located within the lower portion of her tomb is almost invisible. To see it, one would have to get down on the floor to peer in through the windows.[40] The transi here is enclosed rather than exposed and so the tomb does not share the sense of revelation and truth-telling created by the men’s monuments. Instead, the tomb keeps Alice’s transi as almost a secret.

This difference in Alice Chaucer’s tomb connects to ways in which women are – and are not – represented in the three tombs for married couples. In two out of the three, those for Richard Willughby and his wife and for John and Isabella Barton, the lower portion of the tomb contains only one transi sculpture in contrast to the two effigies located on its top surface. Julian Luxford identifies these transis as male figures.[41] The absence of female transis in these tombs is noteworthy in relationship to hidden quality of Alice Chaucer’s. The third of these tombs, that for John Denston and Catherine Clopton, includes two transis as well as two effigies, but the two transis differ in significant ways.

Figure 5. Transis of John Denston and Catherine Clopton, Church of St. Nicholas, Denston. Photo: Julian Luxford

The male figure is very similar to the transis from the men’s monuments in being nearly naked, but the female figure is wrapped up in her shroud. The only parts of her body that are visible are her face and neck and her hands, which are crossed over her body and seem to hold her shroud closed around her.[42] Like Alice Chaucer, she is enclosed rather than exposed, although that is accomplished by her drapery rather than the structure of the monument.

One obvious explanation for the difference of Alice Chaucer’s tomb and for the ways in which women are represented on the couples’ tombs would be an interest in preserving the woman’s modesty either by concealing her transi in her tomb, concealing her body in her transi sculpture, or simply not including a transi for her.[43] However, other evidence argues against this explanation for it shows a willingness to display the female body in death. The 1439 will of Isabel Beauchamp, Countess of Warwick, includes a description of the tomb she wanted built for her that was to include “my image to be made all naked, and no thing on my hede but myn here cast backwards.”[44] Likewise, two women who died in 1485, Elisabeth Mattock and Thomasine Tendring, were both memorialized with shroud brasses – brass plaques that show the deceased as a dead body wrapped up in a shroud, a tradition similar to the transi sculpture but simpler in form that the transi tombs discussed here – that show them with an exposed breast or breasts.[45]

Figure 6. Shroud brass of Thomasine Tendring. St. Peter’s Church, Yoxford, Suffolk.

Photo: © Jean McCreanor. https://flic.kr/p/nH7uvV

A second explanation for these differences is the way truth as a virtue was gendered in late medieval England: it was considered essential to proper masculinity, but was difficult for women to claim. According to Neal, “‘true women’ existed in English culture only as special examples. The contexts in which women could defend themselves as true, or be praised in those terms, were very restricted.”[46] The common misogynistic rhetoric of the Middle Ages associated femininity with deception and deviousness and so with the opposite of truth.[47] The evidence cited above shows women from the Paston family using the language of truth and falsehood specifically in their descriptions of men and “manly” or properly masculine actions. Likewise, another court case cited by Neal features a woman, Joan Maddern, in a dispute in which truth and falseness are contested between two men. In 1527, Richard Knapton sued both Joan and her husband Roger for defamation: Joan had accused him of adultery and infanticide, while Roger had called him a “false heretic” and “false churl” and accused him “false dealings” with regard to Joan that resulted in her being suspended from church.[48] Truth and falseness were thus primarily issues about men and between men. No wonder, then, that Alice Chaucer’s tomb does not lay claim to truth for her in the same way as the majority of the men’s tombs do for their occupants and that the couple’s tombs do not treat their male and female occupants in the same way. Enclosing the woman’s transi as in John Denston and Catherine Clopton’s tomb, or not including a female transi as in the other couples’ tombs, allows these structures act like those built for men alone and claim truth for the men buried in them, but not make the same claim for the women.

Masculinity and Sexuality

In discussing the differences between John Denston and Catherine Clopton’s transi sculptures, I mentioned that she seems to hold her shroud closed around her with her crossed hands – without emphasizing the fact that she takes that action even though she is depicted in the sculpture as a dead. John Denston makes a similarly un-dead action in his transi as he uses his left hand to secure his shroud over his genitalia.[49] This gesture is shared by the majority of the transi sculptures in the tombs discussed here. Again an obvious explanation for this gesture would be a concern for preserving the modesty of the deceased’s bodies by concealing their sexual organs. However, that is not an entirely adequate explanation for the gesture, because the same end could have been achieved by simply draping their shrouds over their bodies without the use of the hand to secure it in place. Indeed, the few transi sculptures that do not make use of the arm gesture – those of Thomas Beckington and William Sponne – do just that: in both, the man lies with both arms extended straight at his sides and yet the cloth comes up to cover over his crotch. The addition of the arm gesture on the other transis thus suggests something more than simple modesty. It indicates activity on the part of these corpses and so intentionality in their covering over their genitalia. That intention can be identified as the exercise of sexual self-control: even after their deaths and as their bodies decay, these men take it upon themselves to actively cover over their genitals and so exercise control over their sexual organs.[50]

In later medieval England, sexual self-control was important in defining ideal, mature, masculinity for laymen and clerics alike. Katherine Lewis writes of how it functioned in defining the image of ideal masculinity and so ideal kingship presented by and for Henry V. Prior to ascending the throne, Henry had a reputation for excessive behavior, including sexual excesses. According to one source quoted by Lewis, the Pseudo-Elmham: “The Prince in his youth was an assiduous cultor of lasciviousness…Passing the bounds of modesty, he was a fervent soldier of Venus as well as of Mars; youthlike, he was fired with her torches, and in the midst of the worthy works of war found leisure for the excesses common to ungoverned age.”[51] However, when he became king in 1413, he became a “different” or “new” man. Lewis quotes Walsingham’s chronicles as stating that “as soon as he was invested with the emblems of royalty, he suddenly became a different man. His care now was for self-restraint and goodness and gravity” and likewise quotes the Brut chronicle as stating that “as sone as he was crowned, enonyted & sacred, Anon soddenly he was chaunged into a new man & sett all his entente to lyve vertuously.”[52] Understanding this apparent change in Henry’s behavior is complex. Lewis argues that his reputation for excess while he was prince may have been promoted by opponents who wished to discredit him and have him set aside as heir to the throne: if so, it did not work, and he was able to reuse that reputation to create this impression of a sudden change upon becoming king. And as king, Henry was apparently celibate until his marriage in 1420. His chastity was not simply a matter of personal virtue, furthermore, but functioned metaphorically in representing his qualities as a ruler: he was able to control himself and so would be able to control others and properly govern the kingdom.[53]

Likewise, Henry’s new and ideal qualities as king made him a model for other men to follow. Walsingham writes, “His conduct and behavior were an example to all men, clergy and laity alike.”[54] Lewis describes Henry’s masculinity in this regard as “hegemonic:” he was above all other men, but they were all on the same “continuum of masculinity” and so could all aspire to be like him.[55] And Henry appears to have attempted to enforce this model of masculine sexual self-control through new regulations for his armies fighting in France that stated the men were not to rape women, have prostitutes living in their camps or in conquered towns or castles, or keep concubines or be in adulterous or other irregular relationship with women. It is unclear how successful these regulations were in controlling his soldiers’ behavior, but the regulations themselves functioned to present Henry’s sexual behavior as a model for others and to show the seriousness with which he aimed to control those he led and ruled.[56]

Henry’s model of masculine self-control would have been important for the men buried in the tombs considered here, both laymen and clerics, for most of them had strong Lancastrian connections.[57] Indeed Pamela King has argued that transi tombs were something of a fad among those with Lancastrian ties. Among the men buried in these tombs, Henry Chichele had a particularly close relationship to Henry V. He had been involved in Henry’s affairs since he was Prince of Wales and it was likely due to Henry’s influence that Chichele was named Archbishop of Canterbury. In that role, he went abroad with the king and served on the king’s council.[58] As a celibate clergyman, Chichele would have been expected to exert a high level of control over his own sexuality. Like Henry, he also would have been expected to control the sexuality of those below him, in particular men in his household who had not taken vows of celibacy including both lay servants and young men in minor orders.[59] John Fitzalan served in France under Henry VI, who did not share his father’s reputation as an ideal man or an ideal king but was instead seen as problematically lacking in self-control and so in control over others including his wife.[60] This would have allowed Henry V to continue to act as a model man for those in the military. John Baret as a merchant had ties not to the kings but to their supporters including Thomas Chaucer and Cardinal Beaufort. Sexual self-control was important for men of his social status as well. Their own sexuality was meant to be channeled in a productive direction through marriage and fatherhood and they were expected to exercise control over the sexuality of the servants and apprentices who were part of their households.[61]

The previous paragraphs point to sexuality as drawing a line between groups of men and in definitions of masculinity. However, this was not a line between the clergy and laymen. Instead, it was a line between mature and responsible men who were capable of self-control and so of the control over others, and younger men who were not (yet) expected to exercise control over themselves – and so needed to be controlled by others. Lewis writes that the stories about Henry’s behavior prior to becoming king conform to the expected – and even to some degree accepted – behaviors of young men of his social standing: for example, his brothers were both known to have fathered children prior to their marriages.[62] His regulations for his army serving in France likewise speak to the expectation that young men serving in the military would rape women, visit prostitutes, and otherwise develop relationships outside of marriage with local women.[63] Similar behavior was expected if not entirely accepted from other young men of other social classes including servants, journeymen, and students at the universities.[64] Jennifer Thibodeaux argues that the expectation that young men would indulge in such behavior can explain the behaviors of some priests who did not conform to the rule of clerical celibacy. For some men, she argues, entering the priesthood did not constitute a transition into mature manhood – it did not act as the equivalent to marriage – and so they continued to act in the ways expected of younger men.[65] Looking at evidence from England in the 1400s, Janelle Werner sees members of clergy being accused of sexual offenses, similar to the accusations brought against their lay counterparts.[66] It is notable that the transi tombs discussed here include multiple tombs for bishops and archbishops who would have been responsible for trying to control such behaviors on the part of parish priests and other lesser members of the clergy. The use of the gesture of genital self-control in their transis may have signaled their ability to control others as well as themselves in a way similar to the rhetoric that surrounded Henry V’s kingship.

Lay Men and Clerics in the History of Masculinity

The structures of these men’s tombs and the gestures performed by their transi sculptures thus point to aspects of masculine identity that were shared by the men buried in them, members of the clergy and laymen alike. This is a very different conclusion about the relationship between clerical and lay forms of masculinity than was drawn in the early work on medieval masculinities published in the 1990s, when Rachel Dressler wrote about knights’ tombs in terms of their masculine identity. At the time, scholars instead emphasized the differences between clerical and lay gender identities and sexuality was identified as drawing a line between the two. R.N. Swanson in particular, in an article published in 1999, starts from the assumption that sexual activity – not sexual self-control – is a defining feature of masculine identity and that members of the clergy who were sworn to celibacy therefore could not be fully masculine: he went so far as to suggest that the clergy may have made up a third gender, the “emasculine.” He writes, “if masculinity is defined by the threefold activities of ‘impregnating women, protecting dependents, and serving as a provider to one’s family’ then the medieval clergy as unworldly celibates were not meant to be masculine.”[67] That is an important “if.” The quote that follows it comes from another influential article, Vern Bullough’s “On Being Male in the Middle Ages.” But when Bullough’s sources are investigated, this definition of masculinity comes from a book, David Gilmore’s Manhood in the Making: Cultural Contexts of Masculinity, that is a work of comparative anthropology based on evidence from the twentieth-century United States and from various non-European cultures.[68] There is thus no medieval basis for this definition of masculinity. The medieval evidence presented here for England in the later Middle Ages – the tombs, the transi sculptures, the texts discussed by Neal, and the evidence marshalled by other recent scholars – shows something very different. In terms of sexuality, as Neal writes, celibacy was an extreme form of the sexual self-control expected of all mature and responsible men.[69] And it was an extreme that not all members of the clergy were able or even attempted to reach: Werner’s research demonstrates the existence of a visible minority of unchaste clergy that included not only those behaving like young men by engaging in fornication but also men in long-term, marriage-like relationships with women, complete with children and shared households.[70]

This brings me, finally, to the words I appropriated from Geoffrey Chaucer for the title of this essay. These words come from the “General Prologue” to the Canterbury Tales where the host describes the monk as a “manly man, to been an abbot able.”[71] We are right to sense a joke here, I think, but not the joke we expect. If following from Swanson and Bullough, we place sexual activity at the center of masculine identity then the joke would be that, on the one hand, the monk as a man sworn to celibacy would not or should not be a very “manly man,” and on the other, that a “manly man” would not make a good abbot for a leader of monks should instead be “emasculine.” However, the text that surrounds this memorable one-liner strongly suggests that this monk is not celibate: he is “outridere” who manages his monastery’s estates and as a result is not cloistered but mixes freely with lay men and women – he does so on the pilgrimage to Canterbury as well. He also “lovede venerie,” that is, hunting but also by implication the pursuit of sexual pleasure.[72] This might make him more “manly” – again if we define masculinity in terms of sexual activity – but it would not make him an “abbot able,” for as the leader of a community of ideally celibate men an abbot would need to be reliably celibate himself. Instead, it seems the joke is that the monk’s apparent active sexuality means he is not a “manly man,” that is one able to exercise self-control, and so would not be a good abbot at all. The clergymen buried in these tombs, by contrast, show themselves to be “manly men” in the same ways as their lay contemporaries, by showing themselves to be true men and men capable of exercising self-control.

References

| ↑1 | Erwin Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture: Four Lectures on its Changing Aspects from Ancient Egypt to Bernini (New York, Henry Abrams, 1992 reprint), 38-9, 62-3, 67, 69, 73. For reassessments of Panofsky’s work see Ann Adams and Jessica Barker, eds., Revisiting the Monument: Fifty Years Since Panofsky’s Tomb Sculpture (London: Courtauld Books Online, 2016) https://courtauld.ac.uk/research/courtauld-books-online/revisiting-the-monument. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rachel Dressler, “Steel Corpse: Imaging the Knight in Death” in Conflicted Identities and Multiple Masculinities: Men in the Medieval West, ed. Jacqueline Murray (New York: Garland, 1999), 141-48; Rachel Dressler, Of Armor and Men in Medieval Europe: The Chivalric Rhetoric of Three English Knight’s Effigies (Burlinton: Ashgate, 2004), 3-4, 11, 60-64. |

| ↑3 | Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture, 27, 47, 49, 52-3. |

| ↑4 | Dressler, “Steel Corpse,” 148-154; and “Cross-Legged Knights and Signification in English Medieval Tomb Sculpture,” Studies in Iconography 21 (2000): 102-106; Of Armor and Men in Medieval Europe, 106-13. |

| ↑5 | Dressler, “Steel Corpse,” 154-8; “Cross-Legged Knights,” 106-15; Of Armor and Men in Medieval Europe, 106-115. |

| ↑6 | “The Monster, Death, Becomes Pregnant: Female Transi Tombs in Renaissance France” in Gender, Otherness, and Culture in Medieval and Early Modern Art, eds. Carlee A. Bradbury and Michelle Mosley-Christian (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 151-78. |

| ↑7 | These tombs are those for Henry Chichele (tomb 1420, d. 1443), William Derby (d. 1438), Richard Fleming (d. 1433), John Fitzalan (d. 1435), John Golafre (d. 1442), John Careway (d. 1443), William Sponne (d. 1448), Thomas Beckington (tomb 1450, d. 1465), John Baret (d. 1467), Sampson Meverell (d. 1462), William or Laurence Booth (d. 1464 or 1480), John Denston (d. 1463) and his wife Catherine Clopton, Alice Chaucer (d. 1475), John Carpenter (1476), Richard (d. 1472) and Anne Willughby, John (d. 1491) and Isabella Barton, and Thomas Heywood (d. 1492). On these tombs see Pamela King, “The Contexts of the Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth-Century England,” 2 vols. (PhD dissertation, University of York, 1987); Julian Luxford, “The Double Cadaver Tomb at Denston, Suffolk: A Unique Object of European Significance,” The Ricardian 26 (2016): 99-112; and Sally Badham and Simon Cotton, “A lost ‘double-decker’ cadaver monument from Terrington St. Clement (Norfolk) in context,” Church Monuments 32 (2017): 28-48. There is also a transi tomb at York Minster that has long been associated with Thomas Haxey but could also have been for John Newton: see Pamela King, “The Treasurer’s Cadaver in York Minster Reconsidered” in The Church and Learning in Later Medieval Society: Essays in Honour of R.B. Dobson, eds. Caroline M. Barron and Jenny Stratford (Donington: Shaun Tyas, 1999), 196-209. |

| ↑8 | A few tombs use brasses for the effigies on the upper level, namely those of William Derby, Sampson Meverell, John Denston and Catherine Clopton, and Richard and Anne Willughby. On these tombs see King, “The Contexts of the Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth-Century England, vol. 1, 89, 97-8, 303-4, 330-332; Luxford, “The Double Cadaver Tomb at Denston,” 102, 105; and Badham and Cotton, “A lost ‘double-decker’ cadaver monument,” 32-38. |

| ↑9 | Badham and Cotton list sixteen surviving examples from 1500-1558 only four of which are two story or double-decker monuments: see “A lost ‘double-decker’ cadaver monument,” 44-45. |

| ↑10 | See, for example, P.H. Cullen and Katherine J. Lewis, eds., Holiness and Masculinity in the Middle Ages (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005); Jennifer D. Thibodeaux, ed., Negotiating Clerical Identities: Priests, Monks, and Masculinity in the Middle Ages ( Palgrave Macmillan, 2010); Jennifer D. Thibodeaux, The Manly Priest: Celibacy, Masculinity, and Reform in England and Normandy, 1066-1300 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015); and P.H. Cullum and Katherine J. Lewis, Religious Men and Masculine Identity in the Middle Ages Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2013 |

| ↑11 | Derek G. Neal, The Masculine Self in Late Medieval England (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 30-41. |

| ↑12 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 41; Norman Davis, ed., Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971), vol. 1, 225. |

| ↑13 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 41-2. |

| ↑14 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 87. |

| ↑15 | Phillipa Maddern, “Honour among the Pastons: gender and integrity in fifteenth-century English provincial society,” Journal of Medieval History 14 (1988), 367. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4181(88)90033-4; Norman Davis, ed., Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), vol. 2, 207. |

| ↑16 | Maddern, “Honour among the Pastons,” 367. Davis, Paston Letters and Papers, vol. 2, 186. |

| ↑17 | Maddern, “Honour among the Pastons,” 366-368. |

| ↑18 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 43. |

| ↑19 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 44. Davis, Paston Letters and Papers, vol. 2, 199-200. |

| ↑20 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 93. |

| ↑21 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 97. |

| ↑22 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 97, 100. |

| ↑23 | Nigel Saul, English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages: History and Representation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 90-1, 321. |

| ↑24 | Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture, 64-5 |

| ↑25 | Ernst H. Kantorowicx, The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Medieval Political Theology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957), 419-437, esp. 434. |

| ↑26 | Kathleen Cohen, Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol: The Transi Tomb in the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973), 38-42. |

| ↑27 | Jessica Barker argues that, even though the base of an effigy tomb did not necessarily contain the corpse – it could have been buried instead in a vault under the tomb or near it – the tomb base would have been understood as containing the body. Jessica Barker, “Stone and Bone: The Corpse, the Effigy, and the Viewer in Late-Medieval Tomb Sculpture,” in Revisiting the Monument, 119-20. |

| ↑28 | Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1996), 147-9. |

| ↑29 | Ashby Kinch, Imago Mortis: Mediating Images of Death in Late Medieval Culture (Brill, 2013), 175. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004245815 |

| ↑30 | Barker, “Stone and Bone,” 130. |

| ↑31 | Panofsky, Tomb Sculpture, 65; Binski, Medieval Death, 144. See also Cohen, Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol, 29-30. |

| ↑32 | Barker, “Stone and Bone,” 114. |

| ↑33 | Binski, Medieval Death, 149. |

| ↑34 | “Monument of the Month: Edward, the Black Prince, d. 1376.” The Church Monuments Society, May 2015. https://churchmonumentssociety.org/monument-of-the-month/edward-the-black-prince-d-1376-canterbury-cathedral-kent. Accessed December 7, 2021. |

| ↑35 | Cohen, Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol, p. 16 note 9 |

| ↑36 | Cohen, Metamorphosis of a Death Symbol, p. 17-18, note 12. |

| ↑37 | Michael Rimmer. “Silver and Guilt: The Cadaver Tomb of John Baret of Bury St. Edmunds,” Journal of the British Archaeological Association 172 (2019): 135-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00681288.2019.1642013 |

| ↑38 | Rimmer. “Silver and Guilt,” 142-46 |

| ↑39 | Saul, English Church Monuments, 97, 113. |

| ↑40 | Kinch, Imago Mortis, 76-7; Jessica Barker, Stone Fidelity: Marriage and Emotion in Medieval Tomb Sculpture (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2020), 169-71. On Alice Chaucer’s tomb see King, “My Image to be Made all Naked,” 304-308 |

| ↑41 | Julian Luxford, “John and Johanna Ormond’s Grave,” in Tributes to Paul Binski, Medieval Gothic: Art, Architecture, and Ideas, ed. Julian Luxford (London: Harvey Miller, 2021), 155. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.HMTRIB-EB.5.129939 |

| ↑42 | Luxford, “The Double Cadaver Tomb at Denston,” 105. |

| ↑43 | On modesty in transi tombs see Christina Welch, “Late Medieval Carved Cadaver Memorials in England and Wales,” in Death in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Times: The Material and Spiritual Conditions of the Culture of Death, ed. Albrecht Classen (Boston: De Gruyter, 2016), 373, 375-6, 379-81. Welch specifically contrasts Alice Chaucer and Catherine Clopton’s transis on this point: see “Exploring Late-Medieval English Memento Mori Carved Cadaver Sculptures,” in Dealing with the Dead: Mortality and Community in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, ed. Thea Tomaini (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 339-343. |

| ↑44 | King, “The Contexts of the Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth-Century England,” vol. 1, 60, 81, 255-6; King, “My Image to be Made all Naked,” 309 |

| ↑45 | King, “The Contexts of the Cadaver Tomb in Fifteenth-Century England,” vol. 1, 112-13, vol. 2 figures 31-2; King, “My Image to be Made all Naked,” 299-300. |

| ↑46 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 50. |

| ↑47 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 50. There is an extensive scholarly literature on medieval misogyny. For one its founding texts see R. Howard Bloch, “Medieval Misogyny,” Representations 20 (1987): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928500 |

| ↑48 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 52-54. |

| ↑49 | On the un-dead quality of transi sculptures see my “The Monster, Death, Becomes Pregnant,” 151-3, 163-4, 172-4; and Welch, “Exploring Late-Medieval English Memento Mori,” 331, 342, 347-9. |

| ↑50 | Alice Chaucer’s transi makes the same gesture and sexuality may have been at issue in her tomb well. The inner chamber in which her transi is located is decorated with paintings including one of the reformed sexual sinner, St. Mary Magdalene. Likewise, in her description of her tomb in her will, Isabelle Beauchamp included an image of the Magdalene. King, “My Image to be Made all Naked,” 307, 309; and Barker, Stone Fidelity, 171-3. There is no indication that the two men whose transis do not include the gesture covering the genitals lacked sexual self-control: it may simply have been less important to them or to those who acted as patrons for their tombs. |

| ↑51 | Kathrine J. Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity in Late Medieval England (New York: Routledge, 2013), 84-5. |

| ↑52 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 84-6. |

| ↑53 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 88-91, 96. |

| ↑54 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 84. |

| ↑55 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 120 |

| ↑56 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 127-131. |

| ↑57 | Pamela King, “The English Cadaver Tomb in the Late Fifteenth Century: Some Indications of a Lancastrian Connection,” in Dies Illa: Death in the Middle Ages, Proceedings of the 1983 Manchester Colloquium (Liverpool: Francis Cairns, 1984), 45-57. |

| ↑58 | Jacob, Archbishop Henry Chichele, 6-7, 14-15, 20, 90, 101-3. |

| ↑59 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 91-2, 94, 105-7. |

| ↑60 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 45, 158-60, 234-5. |

| ↑61 | Isabel Davis, Writing Masculinity in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 2-3, 20-27. |

| ↑62 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 86-7. |

| ↑63 | Lewis, Kingship and Masculinity, 130-1. |

| ↑64 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 156-166; Ruth Mazzo Karras, From Boys to Men: Formations of Masculinity in Late Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 80-2. |

| ↑65 | Jennifer D. Thibodeaux, “From Boys to Priests: Adolescent Masculinity and the Parish Clergy in Medieval Normandy” in Negotiating Clerical Identities: Priests, Monks, and Masculinity in the Middle Ages (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 138-154. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230290464_7 |

| ↑66 | Janelle Werner, “Promiscuous Priests and Vicarage Children: Clerical Sexuality and Masculinity in Late Medieval England” in Negotiating Clerical Identities, 159-167. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230290464_8 |

| ↑67 | R.N. Swanson, “Angels Incarnate: Clergy and Masculinity from Gregorian Reform to Reformation,” in Masculinity in Medieval Europe (London: Longman, 1999), 160-1. |

| ↑68 | Vern L. Bullough, “On Being Male in the Middle Ages,” in Medieval Men: Regarding Men in the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 34, note 17, and 44. For similar critiques see Neal, The Masculine Self, 89-91, 118-9; Jennifer Thibodeaux, “Introduction: Rethinking the Medieval Clergy and Masculinity” and Derek Neal, “What Can Historians Do With Clerical Masculinity: Lessons from Medieval Europe,” both in Negotiating Clerical Identities, 1-2, 16-17, 25-7. |

| ↑69 | Neal, The Masculine Self, 100-1 |

| ↑70 | Werner, “Promiscuous Priests and Vicarage Children,” 166-9. |

| ↑71 | Geoffrey Chaucer, The Tales of Canterbury, ed. Robert A. Platt (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1966), p. 7, line 167. |

| ↑72 | Chaucer, The Tales of Canterbury, p. 6, line 166. |