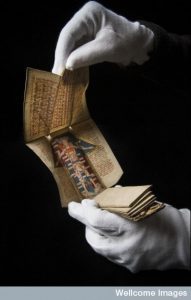

Medieval folding almanac (15th century) 5 inches by 1 ½ inches.

The paper was on physicians’ almanacs: small, folded manuscripts containing medical texts and images, produced primarily in fifteenth-century England. We had a lot of fun presenting the paper and talking to other people about it, and we were excited that it ended up generating many positive responses and engaged conversations. We had attempted to make it as compelling as possible with the use of multi-media (a video in our slideshow) and props: we printed out and constructed several “facsimiles” of a physician’s almanac to pass around the audience and to use as a demonstration piece. But as much as conference-goers were entertained by these things, the facet of our paper that garnered the most questions and comments over several days was the nature of our collaboration: When did you start working on this project? How did the collaboration come about? Have you worked together before? How did you decide who would speak when in your presentation?

And as we talked through the answers to some of these questions, we came to realize that it is still pretty unusual to work in this collaborative way in the humanities, and that many people who would like to embark on such a project are unsure what it might entail or how to go about making it happen. We also realized that many of the people who responded so well to our “finished” product – the talk we gave at the conference, which we agreed went pretty well – wanted to know more about how it got to that stage. Indeed, that process was bumpier than the final product indicated, and so it occurred to us that it might be useful to lay out our process, including what worked well, and what worked less well. We hope this post expands and deepens some of the thoughts in a group blog post on collaboration from January.

In this post, we will shift a bit between “we” and “I,” and we’ll let you know when it’s one or the other of us speaking. There will also be some strange bits of third person narrative. Most of the time, though, it’s both of us—another aspect of collaboration that is both awkward and liberating.

The Proposal

When the call for papers came out, we both had thought independently about paper ideas for what looked like a great conference. When Karen began asking around if anyone else was thinking about sending in a proposal, Jennifer replied suggesting the physician’s almanacs, and might she want to collaborate! This was a new topic that neither of us had done any real research into yet, even though it was related to other work Jennifer was doing on medieval medical imagery, and there were some overlaps with Karen’s work on relics and her interest in diagrams. But to be clear, we constructed the short proposal on GoogleDocs based only a few conversations and brainstorming sessions and no extant research. When it was accepted we were thrilled! And then it sort of hit us what we now had to do: the deadline for our paper was January 31, 2014.

Initial Research and Conversations

Karen was already planning research travel the UK in the summer of 2013, soon after we learned that our paper had been accepted. She reworked her research and conference plans so that should could visit four libraries, where she was able to examine and handle about twenty manuscripts related to the project. She assiduously took mountains of notes, made sketches, took photographs, and then uploaded them to a shared notebook on Evernote, the software we eventually relied upon very heavily as we continued our research and began writing. We had a few conversations over the summer, while both of us were traveling, but then other activities took over and it was later in the summer (or even early fall) before we were able to both look through those materials more carefully as well as begin to think about how we would work on the paper once the fall semester began.

While it was fundamentally important to the project that one of us was able to put in lots of legwork over the summer, it left the other disappointed not to have the exciting, revelatory experience of looking at the manuscripts. Jennifer began to feel a nagging sense of inequity: I felt that I wasn’t pulling my weight. It was an inevitable situation that I could do nothing to remedy, other than gush on all the amazing work Karen was able to do. In retrospect, I still find myself wondering if I should have tried harder to get myself to Europe that summer, but by the time I had these ideas, the fall semester was beginning and it was too late. At the same time, Karen knew there was imbalance: How could I avoid letting the ideas I was having about the manuscripts shape the way I would present them to Jennifer? Was it possible to be an objective gatherer of information at this point, and still learn and discover? How would my process affect our product?

Finally Looking at Almanacs Together!

We had a few conversations and Google+Hangout sessions as the fall semester began, and we began to think about when in our schedules we could carve out time to work on the project together. We discussed Jennifer visiting the East Coast from Oklahoma, so that we could work on the details of the paper and see two of the almanacs that are in American collections: the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York and the Rosenbach Library in Philadelphia. In the meantime, of course our other, more urgent commitments, deadlines, and teaching took immediate precedent. After all, we had until the end of January, right? And quickly the fall semester just slipped away…

In the end, Jennifer’s trip didn’t happen until early December, which meant we had this great flurry of productive conversations and hands-on experiences right before several weeks of activity for family commitments over the winter break. It was now sinking in that upon returning from the break, we essentially would have about a month to organize our gathered material and write the paper. Panic began to set in, for each of us.

That said, the trip was extremely productive: we were able to sit side-by-side in front of two of the manuscripts, bouncing ideas of one another and taking significant notes; we had several days of serious conversations and brainstorming; we also took some great photos and video that were essential to our work over the following several months. It reminded us both, I think, why we wanted to get involved in the project in the first place, and why we wanted to work on it together.

Additional Research and Writing

Eventually we both got pretty stressed out. In retrospect, it seems that it had a lot to do with our different working methods, something that it hadn’t occurred to either of us to discuss ahead of time, or even once we both started feeling some of the strain. It turns out that Jennifer is a slow thinker and writer. She outlines, fills in slowly and incompletely, plays around with ideas and add citations as she goes, then goes back to read sources, then steps away and works on something else. Then she comes back to it, and dabbles some more. She likes to start this process as far ahead of time as possible, to make room for the dabbling and so she doesn’t feel rushed. With this method, her biggest concern was getting a text written in the time that we had. Karen, on the other hand, sets aside a solid chunk of time (whether it is a week or a month) for each project and jumps into it completely — an admittedly idealistic method, but one that the post-tenure sabbatical had allowed in practice. She reads as much as possible and collects support materials, marshals it all together and then when all that is in place, writes very quickly and completely. Her main concern during our crunch time was getting a solid handle on the material and secondary sources so that we could make as strong of an argument as possible. The extreme differences in method and availability were no doubt further exacerbated by our different circumstances — Karen was not teaching, and was living in NYC with immediate access to extensive library collections, while Jennifer was ensconced in the usual semester duties and schedule, as well as parenting.

Jennifer: Unfortunately, I discovered I was still harboring some feelings of inadequacy from the previous summer, so the unexpected challenges we came up against only fueled my concern that I was not keeping up. Karen would have these fantastically productive 12-hour (more?) days, and I would have to catch up in smaller, more digestible hunks, and thinking that all I was doing was seeing what she had done, rather than making my own contribution.

Karen: At the same time, I was feeling my own inadequacies, and having a hard time making the project feel like “mine” — I had no background in late medieval medicine or science, so I was spending long (yes, 12-hour!) days reading contextual material and the scholarship-to-date on medical manuscripts, trying to catch up to Jennifer’s knowledge base. It seemed to me that the ideas that sparked the abstract were largely hers, and I was searching for the arguments I might make about the manuscripts.

We were each feeling insecure and anxious and frustrated. But with relatively little time to do all of this – read a bunch of secondary sources, fabricate our argument, write out our ideas and organize them, and decide what to include and what to leave out as we amassed much more than we needed – we never had the chance to tell ourselves to stop and talk through what we were both feeling, and whether there were some ways we could work around the tensions we were experiencing.

We both became rather protective of our ideas as they made their way into our draft, at times becoming defensive about certain changes and edits. And it turns out we both asked ourselves “can I really do this project with her?” at times during this period. We each complained to our partners; we each cried; we each lost sleep; we each considered “giving in” and just doing what the other wanted (or what we thought she wanted). Looking back now, it seems impossible that it had gotten that bad. But some sleep deprivation, poor communication, and a looming deadline can make things can seem more dramatic than perhaps they really are.

In the end, we both let a number of issues slide by and avoided bringing them up because we were in crunch time. We had to get the paper done, and we did – and it was even pretty good! – and then we both took a breather from thinking about the project for a few weeks. As a result, when we came back together to make our final changes before presenting the paper, we had both done some processing and self-realization about our own methods, and we also allowed ourselves some time to talk about the challenges of writing the first draft. That’s when we shared a lot of our frustrations; the honesty made the rest of the process possible.

Final Editing and Conference Talk Preparations

The final editing and preparations for giving the talk went much more smoothly. By then we had some sense of what had gone wrong, and we both tried to be more cognizant of each other’s concerns. We also managed to divide the remaining workload more evenly, and we also started to get really excited about what we had created. Some distance really made such a difference! We shared a room at the conference, and had a blast the night before the presentation putting together materials and talking through the performance.

Conclusions

In the end, the biggest takeaway we had from this process was that we could have avoided some of the challenges had we talked about our approaches earlier. We had both been involved in other collaborations before, and for those most part those went smoothly. As a result, it didn’t occur to us it would be quite so hard. But few of those previous collaborations had been done from the very beginning with the primary research and through every facet of the project. In a lot of those collaborations, two or more people with independently conducted projects were bringing them together in the writing process, or the collaborative work was done through editing and writing inductions. It turns out there is a big difference in the kinds of collaborations that are possible.

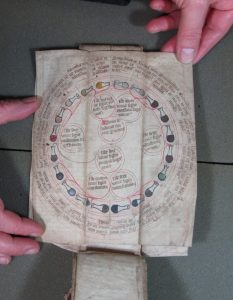

Worn cover of Rosenbach Library MS 1009/24. Photo: Jennifer Borland.

OUR TIPS

TIP 1: give yourself more time than it would take for you to do it by yourself.

TIP 2: Talk, early and frequently, about the way you like to work, write, collect your materials, take notes, and think through ideas. Get down to the nitty gritty: how do you move from earlier drafts to new ones? Do you make a new document, or you use “track changes” or different colored fonts? And so on.

TIP 3: When you feel badly or that things are going right, tell the other person. Talk about it – don’t let it fester. If you follow Tip 1, you should have time for Tip 3.

TIP 4: Don’t assume that all collaboration will work the same. Take each one on its own terms.

Now that the paper has been delivered, and as we look ahead to whatever is next for the project, we both agree that it was an incredibly fulfilling activity. We were thrilled with where we ended up, and we think we produced a better, more complex result than had either of us worked on it by ourselves. At the same time, we could have done some things differently that might have made the process smoother along the way, and we hope sharing something of that process might encourage others to embark on such adventures while avoiding some of the pitfalls along the way. Happy collaborating!