Layla Seale • University of North Texas

Recommended citation: Layla Seale, “Work is Hell: Demon Laborers in Late Medieval Art,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.61302/VZTY4632.

Scholars studying labor have focused primarily on humans, but there’s a rich archive of demonic imagery yet to be analyzed particularly in late medieval northern Europe.[1] Looking closely at demons provokes new and exciting questions about our approach to medieval art and images of the working classes in particular. How do we approach images of devils working and using tools? Late medieval illuminated manuscripts are filled with demon kitchen workers, blacksmiths and construction laborers that skillfully wield knives, meat hooks, bellows, hammers, trowels and other tools. Can we analyze devils as working-class figures? Would a late medieval viewer assume that work is hell?

I argue that labor is a pivotal yet unexamined facet of visualizing infernal beings, especially within the complex, often violent, shifting of class boundaries during this time. This article examines demons using the tools of a kitchen worker, blacksmith, and builder. Though Hell and its demons are often described as a chaotic subversion of divine order, I argue images of devils as workers organize, systematize and familiarize infernal torment. Just as the human working classes were essential figures of medieval social orders, demon workers are vital to the economy of Hell.

Historical Contexts

After waves of the black death decimated the workforce throughout Western Europe, economic measures sought to minimize the cost of labor and to mobilize the laborers left standing.[2] In the mid-fourteenth century, the French monarchy passed a restrictive ordinance limiting the freedom of day laborers and requiring them to accept any job offered at the official daily wage. Though local councils regulated labor markets, the royal ordinance responded to an increasingly vocal merchant class who complained that the wage requests of day laborers were too high. Claiming the moral high ground, the merchants argued that the freedom to refuse work led to lazy men filling the tavern.[3] Such restrictive policies continued throughout the fifteenth and into the sixteenth centuries.

The regulation of labor laws in Flanders was more difficult due to the shifting economic and political issues of landowners, urban elites, and guilds.[4] Merchants and artisans in urban areas advocated for wages based on skill, rather than the uniform wage favored by agrarian noblemen. Neighboring cities competed economically by enticing skilled workers from other areas and thus rarely agreed on blanket labor regulations.[5] Furthermore, the autonomy of late medieval Flemish cities enjoyed weakened considerably under the rule of Philip the Good and his son, Charles the Bold.[6] Middle class artisans, merchants and patrician families demanded the restoration of city privileges that were undermined by the Court´s attempt to unify the Burgundian province.[7] Emerging middle classes of skilled craftsmen and merchant guilds, each with their own economic and social priorities, chafed against the restrictive policies of Burgundian rulers. When Charles died in battle in 1477, revolts continued against Mary of Burgundy. After Mary of Burgundy died in 1482, Maximilian I faced escalating protests and revolts as he sought to secure Flemish territories for the heir, Philip the Handsome, and was eventually taken hostage by protesters in Bruges in 1488.[8] These revolts were not the beginning of economic turmoil, but eruptions of built up class tensions.[9]

![[Miniature and text] Miniature in four compartments: the clergy; the nobility; Jean, Duc de Berry receiving the book; a group of workmen in an interior with their tools, including a spade, saw and an axe. Text beginning with decorated initial 'A',](https://differentvisions.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/1356/2023/05/Figure-1-1024x930.jpg)

Fig. 1. Detail: Des ca des nobles hommes et femmes malheureux, fol. 3. Courtesy British Library, Additional MS 18750.

An attitude of class discord permeated French and Flemish society, as illustrated by the frontispiece for Cas des nobles hommes et femmes malheureux (Fig.1). The manuscript is one of several fifteenth-century copies of Laurent de Premierfait’s French translation, commissioned by Jean duc de Berry, of Giovanni Boccaccio’s De casibus virorum illustrium. According to de Premierfait, conflict amongst the three orders propagated a moral collapse of virtue, the disregard of God, and perpetual civic unrest.[10] An illuminated frontispiece introducing the text is divided into four sections: the three estates of the realm (Clergy, Nobles, and Laborers) and the manuscript’s presentation to the patron. The lower right quadrant depicts two groups of laborers and craftsmen facing each other from either side of an enclosed room. They hold the tools of a shearer, tailor, mason, metalworker, smith, farmer and carpenter. The central figures are posed in a standoff with sharply protruding elbows and knees; the left figure leaning onto his shovel and pointing towards the blacksmith opposing him who holds a hammer and forging tongs in front of his torso in a posture of self-defense. The tumultuous class warfare that erupted between tradesmen and the nobility, as well as amongst laborers themselves, provides another layer of meaning for images of devils who violently wield instruments of working class labor.

Tools of Torture: Kitchen Workers

Fig. 2. Detail: Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur, fol. 82v, MS. Douce 134. Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

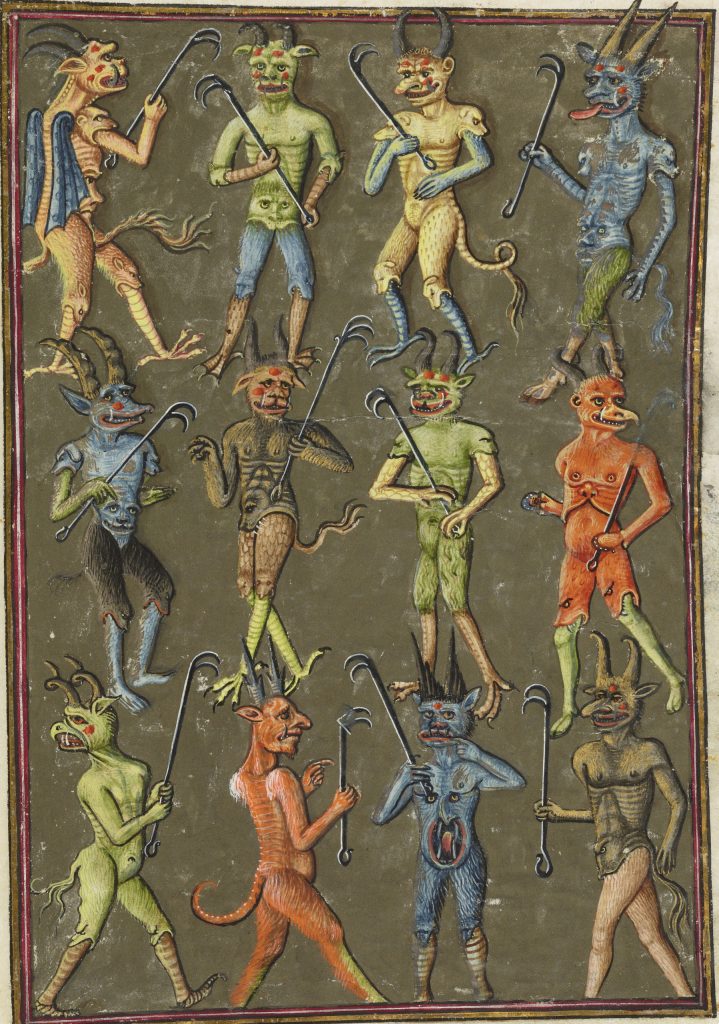

Indeed, close analysis of demon imagery reveals a critical component of the infernal workforce: tools. Here, the immaterial world of the afterlife is materialized through detailed representations of the instruments of human labor. The most common tools that appear in demonic hands are clubs, pitchforks, and fleshhooks. For example, the richly illuminated Livre de la vigne nostre Seigneur is a brightly colored catalog of devils and their implements of torture. In one half page miniature, two demons hold long pitchforks in front of a two-level furnace (Fig. 2). To our modern eye, their upturned mouths and exposed teeth convey diabolical pleasure and workplace satisfaction while simultaneously evoking fear and obscenity for a late medieval viewer. Demons on fol. 99r also face the viewer directly, striking a pose with double-pronged flesh hooks (Fig. 3). These tools were commonly used by cooks to grab and transfer pieces of meat into or out of cauldrons. This is seen in illuminations in the Luttrell Psalter, a fourteenth-century English manuscript (Fig. 4), and the Crusader Bible (also known as the Morgan Picture Bible), a thirteenth-century French manuscript (https://www.themorgan.org/collection/crusader-bible/39). Similarly, demons in the Getty Tondal, a fifteenth-century illuminated French translation of the Vision of Tondal, grab flesh with a pronged tool. Here, a demon skewers a naked human floating in a murky lake with a triple pronged flesh hook, surrounded by fire and fellow demon workers (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3. Detail: Livre de la Vigne nostre Seigneur, fol. 99r, MS. Douce 134. Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

Fig. 4. Detail: Luttrell Psalter, fol. 207r. Courtesy British Library, Add MS 42130.

Fig. 5. Detail: Les Visions du chevalier Tondal, fol. 14v. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS. 30. Digital image courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program.

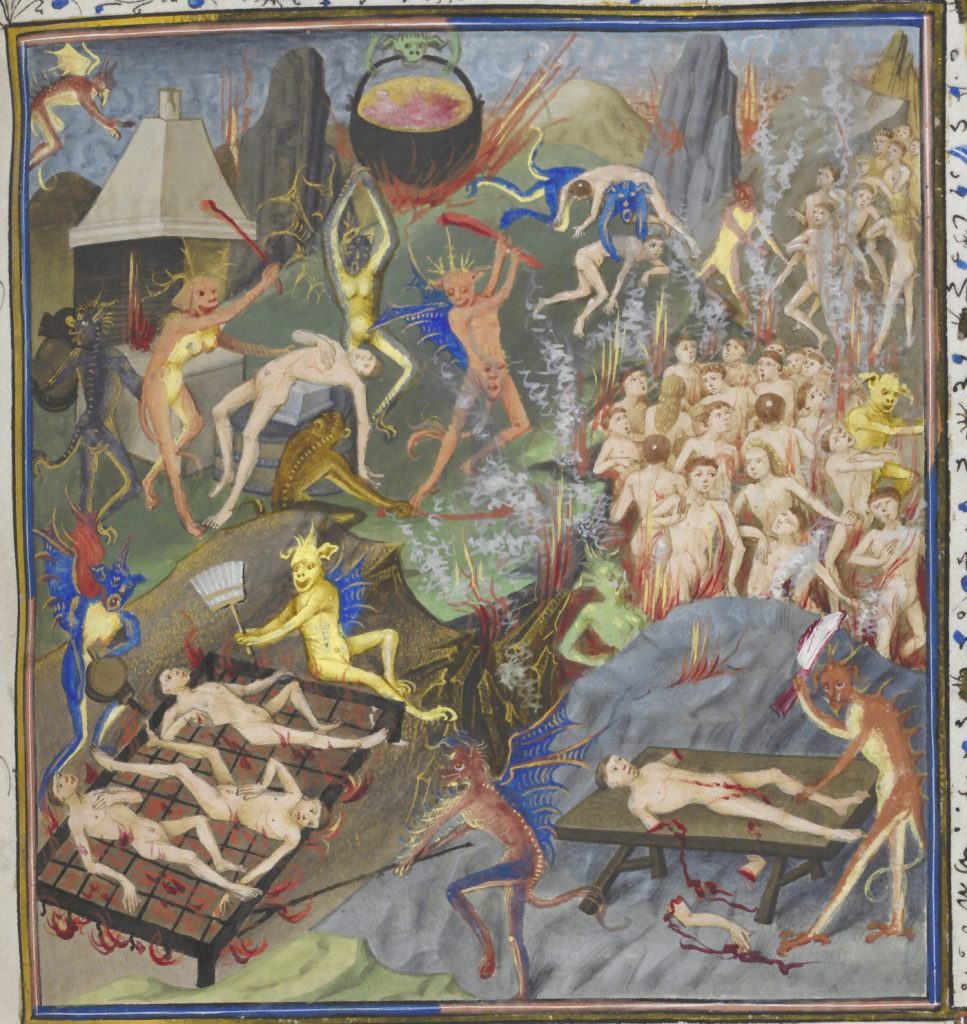

Since hell is a busy workplace, we rarely see devil workers by themselves. Other French and Flemish illuminations of hell resemble infernal workshops with tasks and tools assigned accordingly. For example, different tortures are visually divided into stations in the Traité des quatre dernières choses, c. 1455-67; devils use sticks, knives, pitchforks, and cauldrons to torment and punish the damned on tables, grills, and stone blocks (Fig. 6). Once again the demons eerily resemble human kitchen workers. In the lower right quadrant, a devil wields a large knife and stands before a bleeding human on a long table. The pose imitates that of a kitchen worker in the margins of the Luttrell Psalter (Fig. 7). Each demon and human worker raises a large knife in one hand and holds onto their fleshy target with the other.

Fig. 6. Detail: Traité des quatre dernières choses, fol. 90. Copyright KBR-MS. 11129.

Fig. 7. Detail: Luttrell Psalter, fol. 207v. Courtesy British Library, Add MS 42130.

Such demon-human comparisons find precedence in medieval and early modern visionary literature, which paints a picture of Hell by outlining specific demonic tasks. For example, an Irish seventh-century text, Saint Patrick’s Purgatory, describes souls that are “basted by the demons with liquid metal, while others were baked in ovens and fried in frying pans.”[11] Dante’s Inferno, written in Florence in the fourteenth century, compares the diligent activity of demons to scullery boys shoving meat into a cauldron and Venetian shipyard laborers, plugging leaks with pitch. Dante writes “The Demons did the same as any cook who has his urchins force the meat with hooks deep down into the pot, that it not float.”[12]

Tools of Torture: Blacksmiths

Alongside allusions to cooking are descriptions of demon metalworkers and blacksmiths. A fifteenth-century vision of purgatory by an anonymous English nun provides an elaborate simile comparing demons to smiths:

and these devils cast oil and grease on them and blew vigorously with powerful bellows, so that I could see nothing of them. And then soon after, it seemed these devils laid them on anvils, as smiths do burning iron, and struck them with hammers…

and then it seemed the devils took long iron goads, all aflame, and put them through the barrels, and as fast as they could, they turned them about as men do to clean metal gear in barrels of sand.”[13]

Fig. 8. Detail: Les Visions du chevalier Tondal, fol. 27. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, MS. 30. Digital image courtesy of Getty’s Open Content Program.

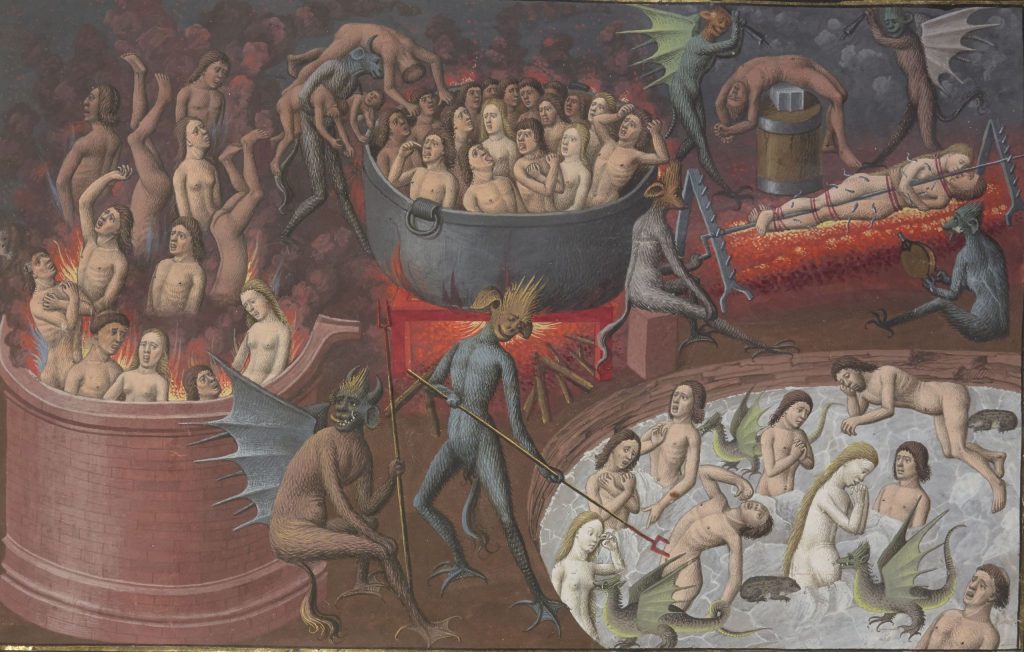

Returning to the visual, there are many examples of demons with blacksmith tools, namely bellows, hammers, anvils, and furnaces.[14] For example, within the Getty Tondal, completed for Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy in 1475, demons wield hammers and prongs while communicating with fellow devil workers (Fig.8). The Forge of Vulcan, The Pain of Those Who Add Sin to Sin, describes devils that stoke a burning fire “and pumped the bellows of the furnace in the same way as one melts iron for casting.”[15] These demon blacksmiths brandish large hammers, forge souls on anvils and “tormenting them, the devils would say, one of the other, are they forged enough?”[16] The manuscript thus presents a hellish labor force enjoying workplace camaraderie with their demon colleagues.

Original Latin translations of Tondal’s vision include longer and more descriptive accounts of demons as smiths:

The torturers ran out to meet with them with burning forceps….they threw him into the burning forge, its flames fanned with inflated bellows. Just as iron is usually weighed, these souls were weighed, until the multitude that were burned there was reduced to nothing. When they were so liquefied that they appeared to be nothing but water, they were thrown with iron pitchforks. Then placed on a forging stone they were struck with hammers until twenty or thirty or a hundred souls were reduced into one mass…The torturers spoke to the conquered saying, “This is enough, isn’t it?” And others in another workshop answered, “Throw them to us and let us see if it is enough.”[17]

The description echoes the forging process for human metalworkers and smiths. Forging iron into quality products required a complex process of heating, hammering, and reheating. Freshly mined materials required smelting before manufacturing or craftwork. Ore was washed in a sieve, burned in a kiln, and then placed in a furnace with charcoal. The material was weighed and transferred to an open forge adjacent to the smelting house where it was hammered on anvils and repeatedly heated in a burning furnace. Bellows, operated either manually or mechanically, stoked the fires with puffs of air.[18]

Demon Blacksmiths in the City of God

Fifteenth-century French translations of Saint Augustine´s De civitate Dei (La Cité de Dieu, The City of God) reproduce illumination cycles that also visualize hell as an infernal workshop. In the text, Hell and eternal torment are discussed in the last chapters (Books XXI and XXII), but they do not specifically describe hell as a busy forge, nor the demons as smiths. However, Augustine writes extensively about the miraculous phenomenon of fire, exclaiming “Who can explain the wonders of fire itself?”[19] Augustine’s eternal fires are both corporeally and psychologically painful, causing material and immaterial suffering.[20] In order to convey the unquenched and enduring fires of torment, illuminators of the Cité de Dieu manuscripts look to workers who regularly work around fire: smiths.

Fig. 9. Detail: La Cité de Dieu, fol. 290r, Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire de Strasbourg, Ms. 523, Image courtesy of Bibliothèque Virtuelle des Manuscrits Médiévaux (BVMM) – IRHT-CNRS.

Fig. 10. Detail: Opera omnia, fol. 156r. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Latin 7939A. Image Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

For example, the illumination of hell in the manuscript at the Bibliothèque nationale et universitaire in Strasbourg displays three demons holding hammers above their heads around a naked human draped across an anvil (Fig. 9). Behind them, a demon stands on top of double bellows next to a furnace. Their posture and tools correspond to depictions of human smiths, such as those within a fifteenth-century illumination of Vulcan forging the arms of Aeneas (Fig. 10). Here again, a group of workers with hammers surround an anvil with double bellows and a furnace in the background.

The hell forge motif also appears in illumination cycles originally created for Charles de Gaucourt, governor of Paris, and painted by Maître François.[21] Two of these manuscripts remain in Paris collections: one in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms. fr. 19 (Fig. 11) and the other in Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 246 (Fig. 12). Hell’s workshop is one of the last illuminations in these cycles and represents the culmination of the demonic threat visualized throughout the manuscript. These brightly illuminated miniatures display demon blacksmiths that hammer human souls on anvils, pump bellows into a furnace, and roast intertwined bodies on a turning spit. However, missing from these depictions of a hellish workshop is the physical obscenity and vulgarity often associated with demons. Though their purpose is violent, their body language, expression and gestures are significantly more muted than the humans. The demons’ facial expressions are neutral, if not somewhat satisfied, and focused on the task at hand. Raised arms convey physical exertion instead of emotional distress. Only one demon in the Sainte-Geneviève manuscript appears demonstrably fatigued under the weight of the human bodies that it carries to a fiery cauldron. Eyes cast towards the ground, its furrowed brow and bent back allude to the rigorous physicality of demon labor. Still, even this level of distress is minor compared to the wretched expressions of the damned. The emotional focus is the pain and despair of human souls, demonstrated by their wide-open mouths, outstretched arms, clawing hands, and bulging eyes.

Fig. 11. Detail: fol. 211r, La Cité de Dieu. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Français 19. Image Source: gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Fig. 12. Detail: La Cité de Dieu fol. 389. Paris, Bibl. Sainte-Geneviève, Ms. 246.

In the midst of hell’s bustling activity, both Paris miniatures highlight a demon that is not actively working and instead shown at rest. In the BnF manuscript, a demon sits on the edge of a fiery furnace, bent over with one hand resting on its knee and the other holding up a pitchfork. Similarly, the Sainte-Geneviève devil sits against a furnace with both hands on knees and a pitchfork leaning against one shoulder. Neither figure interacts with other devils or humans and thus appears disengaged from the work and activity surrounding them. Even the devils sitting on the ground remain physically engaged, roasting humans and stoking fires underneath the spit. We could interpret this as a ‘lazy’ demon or a reference to the sinful nature of idleness.[22] However, it also sparks visual interest by disrupting the narrative composition of working demons.

Demon Builders

Fig. 13. The Haywain Triptych, Hieronymus Bosch. Copyright ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

The diabolical hybrids of Hieronymus Bosch also resemble human workers using tools. Of particular interest for this study is the right panel of The Haywain triptych, 1512-1515, which depicts the infernal fate of the avaricious humans chasing the hay cart in the center (Fig. 13). Scholars generally agree that Bosch´s Haywain presents the pitfalls of human folly, vanitas, and the fleeting nature of earthly possessions. Specifically, the center panel references a Flemish Proverb: “The world is like a cartload of hay and each grabs what he can.”[23] Eric de Bruyn and Walter Gibson suggest religious and literary interpretations for the demonic building in the Haywain, but this infernal construction crew deserves continued inspection and visual comparison.[24]

Fig. 14. Detail: Right panel, The Haywain Triptych, Hieronymus Bosch. Copyright ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

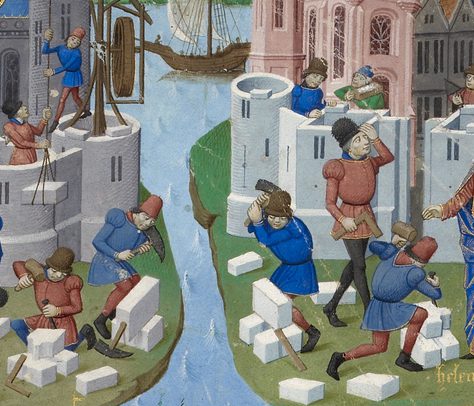

Curiously, the right panel displays a group of demons constructing a stone building (Fig. 14). Two devils stand atop the structure on wood scaffolding; one holds a trowel and lays bricks, while the other bends over a shallow mixing barrel, or hod. A third stands on a windlass that lifts additional materials to the demon bricklayers, as a fellow devil climbs a ladder carrying a bag of mortar or sand. The tools and activities of these demons are strikingly similar to those seen in images of the construction of cathedrals and elite homes in late medieval illuminated manuscripts. Secular architecture under construction is a common motif in historical chronicles such as the Chronicle of the Bouquechardière, c. 1450-75 (Fig. 15). Similar to the Bosch panel, the miniature of “The Construction of Venice, Sycambria, Carthage and Rome” features workers laying stone bricks onto a circular tower with double lancet window, and masonry blocks are hoisted from the ground using a pulley or windlass (Fig 16).

Fig. 15. Chronicle of the Bouquechardière, fol. 150. Courtesy British Library, Harley Ms. 4376.

Fig. 16. Detail: Chronicle of the Bouquechardière, fol. 150. Courtesy British Library, Harley Ms. 4376.

Scaffolding, hoisting contraptions, and bricklayers are also seen in Des profits ruraux des champs, a late fifteenth-century French translation of the Liber Ruralium Commodorum (Fig. 17).[25] Analogous to demon workers in The Haywain, a figure climbs a ladder, while another worker mixes building materials, most likely mortar, in a shallow basin.[26] Another worker cuts and shapes beams using an ax, surrounded by small pieces of wood. Des profits also features a man carrying a jug of water up a ladder, possibly for keeping brickwork and mortar damp before setting.[27] A similar jug appears next to the trowel-wielding demon atop the structure in the Haywain. Both human and demon workplaces contain an array of both skilled and unskilled laborers. Workers tasked with carrying heavy loads convey more arduous physical labor, while those using specialized tools for cutting stone or laying bricks exhibit skills of a trained builder.

Fig. 17. Detail: Des profits ruraux des champs, Fol. 27. Courtesy British Library, Additional MS 19720.

Devils that build contemporary structures with modern tools bring an immediacy and proximity to judgment and hell. They are unnervingly familiar, for both human laborers and the wealthy, influential patrons that oversee building projects. In Bosch’s The Haywain, the hard-working devils focused on construction are visually opposed to the greedy and crazed behavior of humans in the center panel. These demons offer a religious commentary on the incessant sinful nature of humans; hell is a growing metropolis in need of sufficient housing for the damned.[28] Bosch´s realistic portrayal of building materials and tools contrasts with the dark, smoldering ruins seen in the background. While the follies of mankind led to apocalyptic destruction, industrious demons efficiently construct the architecture of Hell.

Demonic Order and Purpose

Working devils create an ordered vision of hell’s society, alluding to division of labor and a social economy of eternal torment. How might we compare the organization of hell’s workers to those of medieval human society? As early as the ninth century, elite medieval thinkers constructed the three orders: those who pray (oratores), those who fight (bellatores) and those who labor (laboratories).[29] For much of the middle ages, laboratores referred almost exclusively to agricultural peasant workers (agricolari-laborare, rusticus) who farmed land in support of their feudal lords and soldiers, or as tenth-century English abbot Ælfric of Eynshan defined: “those who by their labor provide our means of subsistence…”[30] As the urban economy flourished in the high and late middle ages, this category expanded to include tradesmen, merchants and craftsmen, such as masons and blacksmiths.[31] In return for their service, laboratores received spiritual and physical protection from the oratores and bellatores, respectively. These idealized (and subsequently unrealistic) expectations of mutuality amongst the three orders fueled the discourse on labor for centuries, eventually contributing to uprisings and revolts.[32]

Do demons fit in the three orders? Jonathan J.G. Alexander writes that “the process of visualization thus adds gender and class specificity to the verbal indeterminacy of laborantes.”[33] If we combine this interpretive elasticity with the richness of demon iconography, we may expand traditional conceptions of the three orders and transfer feudal mentalities from human to non-human. Indeed, both peasant and demon are subservient figures who provide necessary labor for a higher power. Cast out of heaven to the earth below, devils are “lower” class figures both spiritually and physically. In this sense, we might also envision hell as a feudal society. Mark Bloch defines feudalism as “the rigorous economic subjection of a host of humble folk to a few powerful men.”[34] Although medieval devils may not be “humble folk,” they are imaged as a laboring mass subject to a few powerful figures: God/Christ or Satan, sometimes called the Prince of Devils. For example, groups of working demons surround a crowned devil standing atop a crenelated tower in a fourteenth-century La Cité de Dieu illumination (https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:13556180$64i). The figure’s elevated position and crown convey authority and dominance while the arm and hand gesture suggest speech, perhaps directing the action of the demons below.[35] But, what are the demons producing? In the “fields” of Hell, devils’ labor reaps pain, suffering and eternal torment but this emotional and physical commodity (Hell’s harvest) is ultimately paid to God. Heaven exploits the labor-power of Hell in order to fulfill divine sentencing. However, unlike human workers or indentured serfs, devils cannot buy their freedom or redeem their sins through earthly toil, nor do they fall under the protection of higher powers.

If medieval labor was defined, in part, by ideals of communal support and necessary service, what do demons provide and for whom? According to Christian theologians, Hell´s workers torture human souls that are judged and sentenced by God. Before reaching Hell, humans on earth are tempted or terrorized by the Devil and his demons with the explicit permission of God. Fifth-century theologian Augustine of Hippo declared that “…no demon or man acts unrighteously except by the permission of the same Divine and altogether righteous judgment.”[36] In the sixth century, Pope Gregory the Great admitted that Satan and his demons were perpetually in conflict with God and the pursuit of piety, but remained enforcers of holy judgment.[37] Similarly, in the thirteenth century, Thomas Aquinas explained that demons were deputized by God, who was ultimately responsible for demonic assaults.[38] Sixteenth-century French demonologist Jean Bodin reiterated that the Devil was sent by God and that all infernal punishment stemmed from heavenly judgment.[39] Though demons are irredeemable heavenly outcasts, they perform labor that is assigned by Heaven and spiritually necessary. In this sense, demons’ labor is both damned and divine.

This dialectical tension is intrinsic to art historical approaches to laboring demons. Are demons with anvils, bellows, hammers and trowels a deliberate demonization of blacksmiths and construction laborers? Iconographically, it’s not that straightforward. Bellows alone carry both sacred and diabolical meanings. They are described as increasing the devil´s fire and, conversely, as a means to enflame the fires of devotion and purity within private meditation.[40] Human blacksmiths and metalworkers were prominent urban figures and integral to the medieval social landscape. In late medieval daily life, smiths provided vital services to royal courts and urban centers, fashioning armor, shoeing horses, and forging arms. Metalworkers and smiths recognized and celebrated patron saints; Saint Eloi (alternatively known as Eloy, Eligius) was popular in France with a well celebrated feast day during which the Dukes of Burgundy reportedly gave gifts of silver to the court’s blacksmiths.[41] Tools of construction and carpentry also defy easy interpretation. For instance, the Christian gospels describe Jesus Christ and Joseph as carpenters. Masons and builders were held in high esteem, particularly by clergy leaders who sought the construction of grand cathedrals.[42]

What about viewer reception? On the one hand, when placed in a specifically religious context, such as a spiritual treatise or book of hours, demon workers in hell contribute to purposeful spiritual meditation and prayer. These detailed images bring an immediate materiality to the otherworldly nature of demons and eternal punishment. Dense theology is thereby translated and clarified into a visual vernacular, a common theme within late medieval patronage.

However, the intended audiences for the illuminations in this article would not have experienced the backbreaking labor of a smith or construction laborer. Devils in luxurious illuminated histories or texts by early church fathers were commissioned by wealthy bibliophiles of the French and Burgundian courts. They lived in luxury and comfort, overseeing their estates and engaging in court activities. In some respects, the daily grind of a human worker was just as alien to this audience as those of a demon. A precise rendering of working class labor may have resonated with illuminators in a workshop rather than nobility. Following that point, it is tempting to extrapolate a subversive attempt by the illuminators to satirize the imagined horrors of wealthy patrons.[43] Perhaps, for a pampered aristocracy, work is hell.[44]

Regardless, these images offer complicated networks of class identification and the question of how privileged patrons interacted with images of demon workers remains, especially since these depictions develop during a tumultuous period of civic uprisings.[45] Echoing the violent loosening of class structures, do demon workers represent a new hierarchy over formerly elite souls now damned to eternal torment? On the other hand, these images may further dehumanize and demonize lower status workers by placing their tools in the hands of violent and evil devils. Perhaps it is easier to argue that depicting demons with tools was an artistic strategy to visualize the unseen, in line with the trend towards realism and naturalism in early Netherlandish painting in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Among fifteenth-century illumination workshops, depictions of demons using tools were repeated and commonly used models possibly stemmed from an intellectual exchange among illuminators. Much was indirectly or unconsciously understood by the viewer because of the repetition of these motifs and the prevalence of demonic imagery in Northern Europe at this time.[46] The uncanny materiality of bellows, furnaces, hammers, scaffolding and construction helps demonstrate the proximity and reality of eternal torture in hell. Still, I argue that images of demons are not merely an exercise in realism. They are also ideological presentations that culturally interpret and contextualize these liminal otherworldly figures.

Fig 18. “Work is Hell” infographic, Workfront Inc., 2013. AtTask Enterprise Work Management.

Though twenty-first century society describes itself as modern and enlightened when compared to the so-called “dark ages,” the relationship between work and Hell remains. For instance, a 2013 Workfront Inc infographic boldly proclaims “WORK IS HELL” in large block letters that hover over a hellish landscape littered with papers, computer monitors and keyboards (Fig. 18). A dejected man in a gray suit sits on a rock, his torso bent forward and head hung low. The visual parallel between the demon worker resting by the furnace in the Cité de Dieu and this browbeaten capitalist evokes Augustine’s descriptions of the shared experiences of both devils and humans, “…the life of the demons in our heaven of air and the life of men on earth is most wretched, abounding as it does with mistakes and anxieties.”[47]

This article demonstrates how examining the demonic daily grind complicates traditional art historical analysis of the working classes, highlighting the interpretive possibilities offered by images of demons and devils. Though texts seek to codify demons and devils, visual images convey a broad ideology that describes how these beings looked, behaved, and thought. They are not simply evil, unknowable beings; they are the everyday laborers in an infernal workshop.

References

| ↑1 | See Georges Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Jacques le Goff, Time, Work and Culture in the Middle Ages, trans. Arthur Goldhammer, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982); Jonathan J. G. Alexander, “Labeur and Paresse: Ideological Representations of Medieval Peasant Labor,” The Art Bulletin 72, 3 (September 1990); and Paul Freedman, Images of the Medieval Peasant (Stanford University Press, 1999). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Theories that the black death specifically affected Dutch proto-industry are debated. See Peter Hoppenbrouwers, and J. L. Van Zanden, Peasants into Farmers? The Transformation of Rural Economy and Society in the Low Countries (Middle Ages-19th Century) in Light of the Brenner Debate (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001). |

| ↑3 | Catharina Lis and Hugo Solis, “Labor Laws in Western Europe, 13th -16th Centuries,” in Working on Labor: Essays in Honor of Jan Lucassen, ed. Marcel van der Lindon and Leo Lucassen (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 371. |

| ↑4 | Lis and Solis, Working on Labor, 317. |

| ↑5 | Lis and Solis, Working on Labor, 317. |

| ↑6 | Jan Dumolyn, “‘Our land is only founded on trade and industry.’ Economic discourses in fifteenth-century Bruges” Journal of Medieval History 36 (2010), 375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2010.09.003 |

| ↑7 | Dumolyn, 375. |

| ↑8 | Thomas Kren and Scott McKendrick, Illuminating the Renaissance: The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2003), 4-6. |

| ↑9 | Dumolyn, 374–89. |

| ↑10 | Nigel Mortimer, John Lydgate’s Fall of Princes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 36. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199275014.001.0001 |

| ↑11 | “Saint Patrick’s Purgatory” in Eileen Gardner, ed. and trans., Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante (Italica Press, 1989), 140. |

| ↑12 | Dante Alighieri and Allen Mandelbaum, The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Inferno: A Verse Translation, with an Introduction by Allen Mandelbaum (New York, N.Y.: Bantam Books, 1988), Canto 21.55–57, Canto 21. 7–18, Accessed through https://digitaldante.columbia.edu/dante/divine-comedy/inferno/inferno-21/. |

| ↑13 | “…And pese deuelles keste oyle and greishe to ham and blew fast with stronge belyes pat I might se no-thyng of ham. And pan sone aftyr me pozt deuelles leid ham on anyvelles as smythes done brennyng iren and smothen on ham with hameres.” “..And oe deuelles were eure rakynge on ham with strange hokes as me pynke womnne drawen wolle with cambes.” “…and pan me thozt pe deuelles tok lange gaddys of iren al brennynge and put progh-out pe barailles, and as fast as pay myzt, pay turned ham about as men don harneis in barrailles” (A revelation of purgatory by an unknown, fifteenth-century woman visionary, ed. Marta Powell Harley [Michigan: E. Mellen Press, 1985], 124, 127, and 128). |

| ↑14 | See also, Jérôme Baschet. Les Justices de l’Au-Delà: Les représentations de l’enfer en France et en Italie (XIIe-XVe siècle) (Paris: École française de Rome, 1993); and Petra van Boheemen and Paul Dirkse. Duivels en demonen: De duivel in de Nederlandse beeldcultuur (Utrecht: Museum Het Catharijneconvent, 1994). |

| ↑15 | Roger Wieck and Madeleine McDermott, The Visions of Tondal: From the Library of Margaret of York (Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1992), 50. |

| ↑16 | Roger Wieck and Madeleine McDermott, The Visions of Tondal: From the Library of Margaret of York (Malibu: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1992), 50. |

| ↑17 | “Appropinquantes autem occurrerunt eis tortores cum ignitis forcipibus et angelo nihil dicentes ceperunt animam , que sequebaturj et tenentes projecerunt in caminum ignis ardentem, et sic follibus sufflantes, sicut solet examinari ferrum, ita examinabantur, donec ad nihilum redigeretur illa multitudo animarum, que ibi urebantur. Gumque ita liquefierent, ut nil aliud nisi aqua apparerent, jugulabantur tridentibus ferreis, et positi super incudem percutiebantur malleis, donec vicene vel tricene vel centene anime in unam massam redigerentur, et tarnen, quod est gravius, non ita perirent; desiderabant enim mortem et invenire non poterant. Loquebantur vero tortores ad invicem dicentes: Nonne eufficit? Et alii in alia domo respondebant: Proicite nobis, ut videamus, si sufficit” (Albrecht Wagner, ed., Visio Tnugdali lateinisch und altdeutsch [Erlangen: Deichert, 1882], 81). See also, “Vision of Tundale,” in Eileen Gardner, ed. and trans., Visions of Heaven and Hell Before Dante (Italica Press, 1989), 172. |

| ↑18 | Patricia Basing, Trades and Crafts in Medieval Manuscripts (London: British Library, 1990), 62. |

| ↑19 | Augustine of Hippo, City of God, Volume I: Books 1-3, trans. George E. McCracken, Loeb Classical Library 411 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 17. “De ipso igne mira quis explicet, quo quaeque adusta nigrescunt, cum ipse sit lucidus, et paene omnia quae ambit et lambit colore pulcherrimus decolorat atque ex pruna fulgida carbonem taeterrimum reddit?” |

| ↑20 | Augustine, 65. |

| ↑21 | Sharon Dunlap Smith, “New Themes for the City of God around 1400: The Illustrations of Raoul de Presles’ Translation,” Scriptorium 36, 1 (1982): 68–82, 79. https://doi.org/10.3406/scrip.1982.1245 |

| ↑22 | For more on the ‘lazy’ peasant worker, see Alexander, “Labeur and Paresse,” 445-447. See also Siegfried Wenzel, The Sin of Sloth: Acedia in Medieval Thought and Literature (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960). |

| ↑23 | Isidro Bango Torviso, Bosch: Reality, Symbol, and Fantasy (Spain: Silex Pub, 1982), 155-156. See also “Cat. 35: The Haywain Triptych” Bosch: The 5th Centenary Exhibition (Madrid: Museo Nacional del Prado, 2016), 287. |

| ↑24 | Eric de Bruyn, De vergeten beeldentaal van Jheronimus Bosch:de symboliek van de Hooiwagen-triptiek en de Rotterdamse Marskramer-tondo verklaard vanuit Middelnederlandse teksten (Adr. Heinen, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, 2001), 154-156; Walter Gibson, Hieronymus Bosch (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973), 76-77. |

| ↑25 | Basing, 12. |

| ↑26 | For more on workers and mortar, see article by Barbara Crostini in this volume. |

| ↑27 | Basing, 73. |

| ↑28 | De Bruyn, 155. See also Charles de Tolnay, Hieronymus Bosch, trans. Michael Bullock and Henry Mins (London: Metheun, 1966) 404. |

| ↑29 | See Andrew Rabin, ed., The Political Writings of Archbishop Wulfstan of York (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2015). See also Duby, The Three Orders: Feudal Society Imagined (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982). |

| ↑30 | Aelfric, Abbot of Eynsham, Aelfric’s Lives of saints being a set of sermons on saints’ days formerly observed by the English church (London : N. Trübner for the Early English Text Society, 1881-1900), 2:120-24. |

| ↑31 | Freedman, 37. |

| ↑32 | Freedman, 27. |

| ↑33 | Jonathan J. G. Alexander, “The Butcher the Baker, the Candlestick Maker: Images of Urban Labor, Manufacture and Shopkeeping in the Middle Ages,” in Material Culture and Cultural Materialisms (Belgium: Brepols Publishers, 2001), 90. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.ASMAR-EB.3.1360 |

| ↑34 | Marc Bloch, Feudal Society, trans. L.A. Manyon (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1961). |

| ↑35 | For more on the iconography of gesture see François-Joseph Garnier, Le Langage De L’image Au Moyen Âge (Paris: Le Léopard D’Or, 1982). |

| ↑36 | Augustine of Hippo, City of God, Volume I: Books 1-3, trans. George E. McCracken, Loeb Classical Library 411 (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 253. |

| ↑37 | Philip C. Almond, The Devil: A New Biography (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2014), 55. https://doi.org/10.7591/9780801471872 |

| ↑38 | Almond, 64. |

| ↑39 | Jean Bodin, On the Demon-Mania of Witches, Translated by Randy A. Scott (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 1995), 169. |

| ↑40 | See Margery Kemp, The Book of Margery Kemp, trans. Anthony Bale (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 249n83. |

| ↑41 | Ronald Webber, The Village Blacksmith (London: David and Charles Publishers, 1971), 25. |

| ↑42 | Lis and Solis, Working on Labor, 371. |

| ↑43 | Andre Leguai “Les revoltes rurales dans la rouyamme de France du milieu du XIVe siecle a la fin du XVe,” Le Moyen Age 88 (1982): 49–76. |

| ↑44 | While many aristocrats performed tasks and worked to maintain estates or expand territories, rarely did that involve the daily grind of physical manual labor. |

| ↑45 | Jan Dumolyn, “‘Our land is only founded on trade and industry.’ Economic discourses in fifteenth-century Bruges” Journal of Medieval History 36 (2010), 374–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2010.09.003 |

| ↑46 | Alexander, “Labor and Paresse,” 455. |

| ↑47 | Augustine, City of God, Volume IV: Books 18.36-20, Trans. by George E. McCracken, Loeb Classical Library 411 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 251. |