Susan M. Kim • Illinois State University

Asa Simon Mittman • California State University, Chico

Recommended citation: Susan M. Kim and Asa Simon Mittman, “Ungefrægelicu deor: Truth and the Wonders of the East,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010). https://doi.org/10.61302/TJOI9538

The Wonders of the East as it occurs in its two Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, Cotton Vitellius A.xv and Cotton Tiberius B.v, is a catalog of wonders, marvelous people, creatures and things to be found in “the East”: that is, men without heads, women with tails, dragons and ants as big as dogs.[1] It is easy to read these texts and illustrations—as many have—as simply imaginative, either wholly fictive (we know that there probably were not incendiary chickens anywhere near the Red Sea), or partially fictive, as narratives constructed from perception of unfamiliar cultures (the construction of the Sciopod from witnesses to the practice of yoga,[2] for example). But, as Carolyn Walker Bynum has argued with respect to later medieval texts, the genre of these texts as catalogs of wonders carries with it a claim not only to imagination and the fantastic, but also to the credible, and to truth. Bynum, following Gervais of Tilbury, concludes her survey and analysis of medieval theories of wonder with the observation that “if you do not believe the event, you will not marvel at it. You can marvel only at something that is, at least in some sense, there.”[3]That is, the very status of the Wonders as wonders implies at once the stretching of possibility, and an insistence on the viability of the same possibility, at once the incredibility and the truth of the narrative.

That the Anglo-Saxon readers and viewers of these texts probably considered them true is suggested in part by the rhetoric of the texts themselves. To begin with, the epistolary frame common to the tradition, from its earliest sources in Ctesias and Megasthenes[4] through later versions like the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, has been long lost; we have no explicit narrator to pass judgment on the wonder, and no coherent narrative. As Mary B. Campbell has noted, the text of the Wonders “is delivered in the unadorned, declarative mode proper to information. The almost total absence of context … greatly intensifies our experience of the grotesque, but at the same time the rhetorical starkness to which that absence belongs suggests for its depictions the status of fact.”[5] The “status as fact” is further reinforced on the one hand by the inclusion of similar materials in authoritative and encyclopedic texts such as Augustine’s City of God, and later Isidore’s Etymologies as well as the mappae mundi, but also by the manuscript contexts, particularly in the case of the Tiberius B.v Wonders, positioned as it is among other early medieval scientific, geographical and computistical texts.[6] But that Anglo-Saxon readers and viewers of these texts and images may also have considered their truth a problematic one is equally clear within the language of the texts.

Certainly, the text assures us that many of the wonders will flee (as do the fan-mouthed lion heads and, sweating blood, the fan-eared men); burst into flame (as do the hens and the eight-footed, two-headed creatures); or kill (the corsias serpents) or eat us (the hostes, the Donestre); if they are touched, approached, or even perceive the approach of men: the vivid reiteration of the dangerous results of contact with these wonders suggests that their existence is not to be considered open to experiential verification. Furthermore, in a world in which all created things function symbolically, and in which the monstrous as explicated by Augustine and Isidore, among others,[7] has an especially vivid association with the sign—as Lisa Vernor puts it, succinctly, “The monster is always a sign of something else”[8]—even insistence on the real existence of the monstrous also points away from the very materiality of that existence.

The Old English version of the text of the Wonders in both the Tiberius and Vitellius manuscripts suggests provocative self-consciousness of the problematic status of the truth-value of the wonders it depicts perhaps most clearly in two moments early in the text, a self-consciousness reiterated and complicated by the associate images. That is, twice, in what Andy Orchard numbers as the third and fourth episodes of the Old English text, the word ungefregelicu / ungefrægelicu is used in the conclusion of the description. The first is in the description of the red hens and the second in the episode that immediately follows it, in the description of the eight-footed, two-headed beasts. The contexts are remarkably similar. The description of the incendiary hens concludes:

gif hi hwylc mon niman wile ol>l>e hyra o æthrined l>onne forbærna hy sona eal his lic l>æt syndon ungefægelicu liblac[9]

(If any man wishes to seize or touches them, then they burn up all his body at once. Those are unheard-of witchcrafts.)

That of the eight-footed beasts:

gif him hwylc mon onfon wille I>onne hiera lichoman

I>æt hy onælad I>æt syndon I>a ungefrægelicu deor(If any man wishes to grasp them then they set fire to their bodies. Those are unheard-of beasts.)[10]

Both passages promise that even the desire to grasp or touch these wonders has predictably disastrous consequences for the interactant/traveler/reader and the wonder: if desire for contact is permitted, one or the other, or both, will be utterly lost, burned up completely. And the differences between the passages emphasize the increasing destruction that desire for contact will spark. The first promises destruction to the traveler for his desire to touch; the second substitutes hiera lichoman (“their bodies”) for his lic, (“his body”), moving from a single point of danger to the traveler’s body to the undifferentiated plural, “their bodies,” the bodies of the wonders, most literally, but perhaps also of the wonders and the traveler. The emphasis in the conclusions to these two episodes on both the dangers of contact and the ungefrægelicu, “unheard-of” status of these incendiary creatures suggests that if we wish to heed these warnings, to preserve the reader/viewer self as represented by the “any man,” and the wonder from which he differs (and which he might desire to grasp or incorporate), if we wish, moreover, to preserve the distinction between reader/viewer and wonder, we must also step back from the fact of their prior representations. The Old English text insists that these wonders, however represented, in both text and image, must also remain untouched, unrepresented—“unheard-of,” unknown, unassimilated.

The iterated ungefrægelicu is all the more striking given the fact that, in the most proximal Latin text, that of the parallel text in Tiberius B.v, neither of these two descriptions concludes with even a similar phrase: the description of the hens concludes simply totum corpus conburit (“it burns up [his] whole body”) and the description of the eight-footed beasts, corpora sua inarmant (“they burn up their bodies”).[11] In comparison to the Latin text, the Old English, then, seems to be expressing its own wonder at these beasts.

There are of course a number of instances in other episodes in which the Old English translation diverges from the Latin, even within the Tiberius parallel texts. The women with tusks and tails, for example, are killed by Alexander in the Latin pro sua obscenitate (“because of their foulness/uncleanness”), but in the Old English of both the Tiberius and Vitellius version for heora mycelnysse (“for their greatness”)[12]—and these divergences are certainly significant.[13] But the insertion of ungefrægelicu is the only instance we have found in which an entire phrase is present in the Old English but not the Latin text in two successive episodes.[14]

In fact, according to the Dictionary of the Old English Corpus, the word ungefregelicu occurs only in these two contexts. Its meaning is clear enough (un + gefrege + lic = “un-heard-of”, hence as Orchard translates it, “extraordinary”[15]), and ungefræge appears helpfully as a gloss for inauditum.[16] Inauditum, however, is glossed both by ungefræge (“unheard-of”) and by ungeleafulne (“incredible”).[17] That these moments of marked difference from the Latin text also voice perhaps suspicion of its truth (these creatures are incredible, not to be believed), but certainly reluctance to allow for its unimpeded representation (there creatures are unheard-of, even after their verbal description and illustration, under a kind of erasure), suggests a significant tension between the Old English and Latin texts, and a tension here focused on the truth-value of their representations.

Here it is important to remember that the three early medieval Wonders texts emphasize the coexistence of the two literary languages of Anglo-Saxon England: the later Bodley 614 is in Latin only, [18] Tiberius is in both Latin and Old English, Vitellius is in Old English only. Although we may consider the Wonders to be a sort of tissue binding together the discourses of these three manuscripts, as does Nicholas Howe, we might also argue that precisely by spanning these two languages and three manuscripts, the Wonders incorporates those differences and the tensions between them.[19]) That is, even as its iteration in the two languages across three manuscripts links the manuscripts, through its hybrid creatures and hybrid texts, its fractures and internal disjunctions, the Wonders also extends and exemplifies the tensions among those languages and manuscripts.

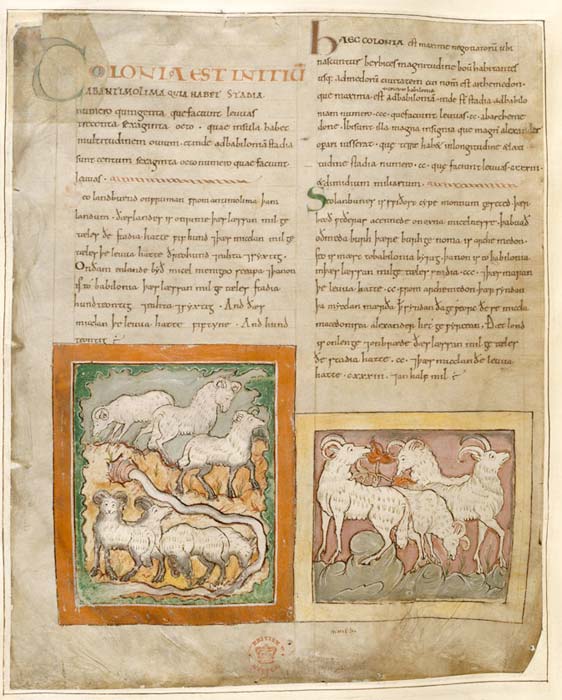

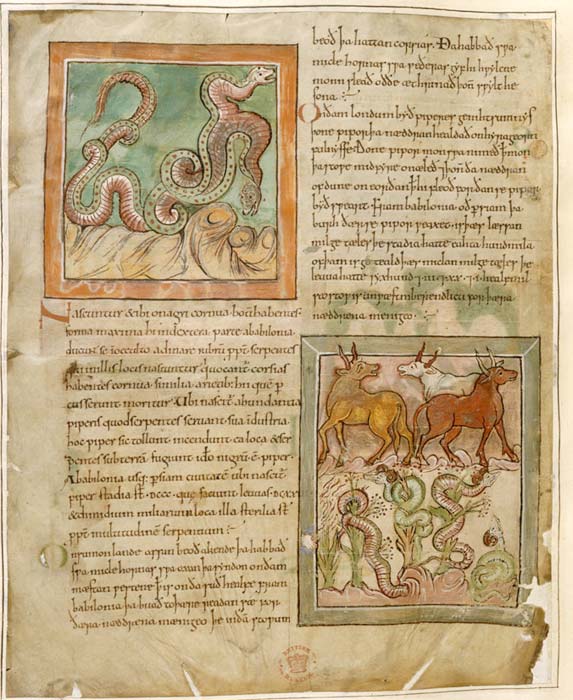

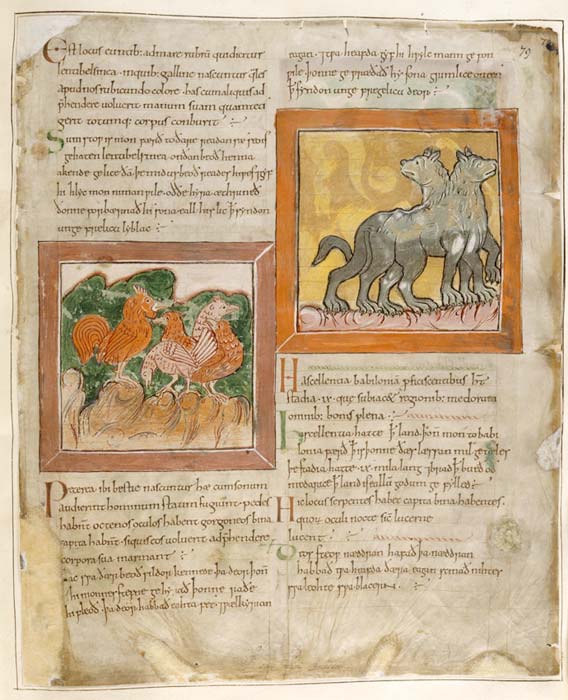

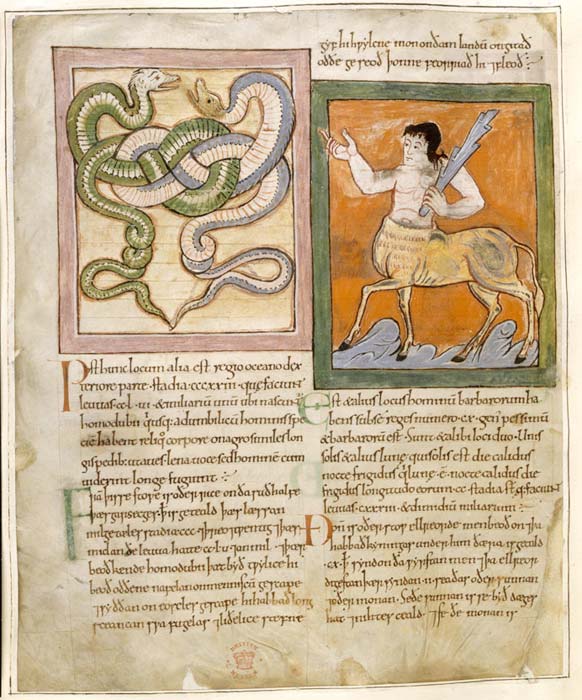

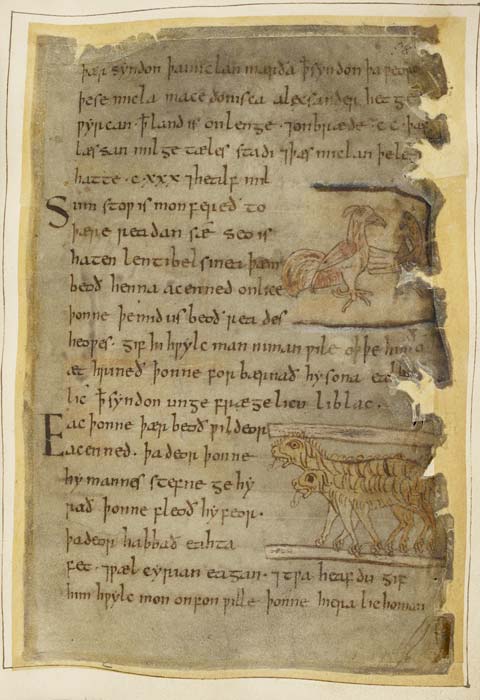

In his provocative reading of the Wonders in Tiberius B. v, Nicholas Howe notes that the text begins with the enlarged capitals in red and green for the Latin, Colonia est initiu (“A colony is at the beginning…”) (Figure 1).[20] For Howe, this opening to the Wonders prioritizes the Latin text, “both by size and position” over the Old English which appears to the right and below it; in doing so, the Tiberius Wonders text locates itself in “a geography of empire that must by its very structure have a center, that is, a capital place that bestows the category label of colonia on a distant and subordinate region.”[21] If the arrangement of the texts of Tiberius Wonders begins with such a clear prioritization, however, its images also present some discomfort with that prioritization. In the early illustration of the two-headed snake, for example, the Tiberius image splits the focus of the snake in two directions (Figure 2). One head, the head on top of the snake, points upward and to the right, towards the Old English text beside it. The other head points downward, towards the Latin text below it. Through this split focus, the wonder itself both emphasizes the co- existence of both versions of the text and points to a potential reversal of the initial positioning of the Latin over the Old English. While other images in Tiberius point less dramatically to the text in both languages, images of doubleness in this manuscript often involve either a split focus pulling the wonder in two directions, as in the illustration of the eight-footed, two headed beasts (Figure 3), or as in the case of the dragons (Figure 4), a complex entanglement of the two bodies ending in a confrontation of one with the other.

Fig. 1. Giant Sheep, Marvels of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 78v (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 2. Two-Headed Snakes; Donkeys with Horns as Big as Oxen’s; Corsias, Marvels of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 79v (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 3. Burning Hens; Inconceivable Beasts, Marvels of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 79r (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 4. Giant Serpents; Onocentaur, Marvels of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Tiberius B.v, fol. 82v (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

In Howe’s reading, the translation of the Latin text into English is a kind of ‘transplanting’ of the exotic elsewhere onto the native land: he argues, “What can be written about in the native language, this transfer insists, cannot remain entirely foreign.”[22] While the Tiberius images as well as the presentation of the text itself point to the retention of both languages, they also, in the tangled and divided bodies of the wonders, indicate resistance to such transfer, retention, that is, of the foreign and incomprehensible, in the body of the text itself. Certainly Howe argues for this kind of retention in his reading in the Donestre episode of the traveler’s head as the unconsumable remnant of the Foreign (which the Donestre weeps over).[23]

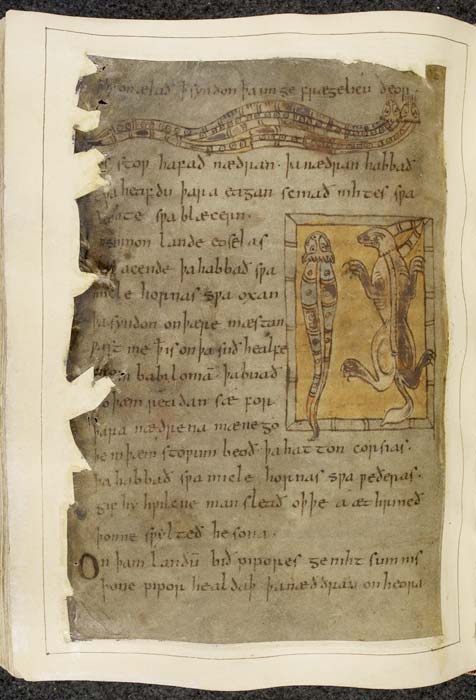

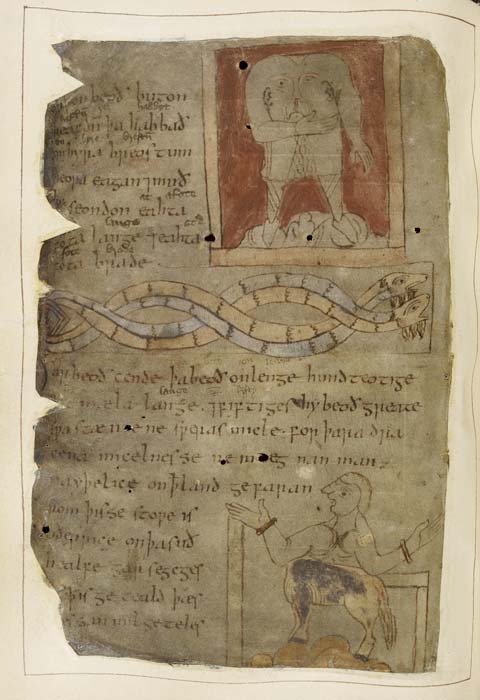

If the Tiberius manuscript locates resistance in the refusal to prioritize Latin over English and retains difference, marked by the difference between languages, then Vitellius, with its text in Old English only, one might suppose, ought to present the possibility of assimilation, familiarity, locatability. Hence, in Howe’s argument, in contrast to Tiberius, the Vitellius Wonders, with its text in Old English only, points not to the simultaneously here and there of Roman authority in England but to “the ePel,”[24] the native land. Thus, in the context of the split pointing in the Tiberius two-headed snake image, the very different Vitellius image is all the more striking (Figure 5). Here, the snake, frameless, itself horizontally divides the Old English text. Both of the snake’s two heads are upturned; its tongues, or the flames it breathes, lick the text and even merge in a sequence with the descender of the final letter of the last word of the preceding episode. Similarly, the eight-footed, two-headed beasts, which in the Tiberius image are pulled in separate directions, here look together in a single direction, tongues lolling toward the Old English text (Figure 6). The dragons, again, unlike the tangled and oppositional creatures of the Tiberius image, here point both heads in a single direction toward the text of the facing page (Figure 7).

Fig. 5. Two-Headed Snakes; Corsias, Wonders of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 2v [99v] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 6. Burning Hens; Inconceivable Beasts, Wonders of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 2r [99r] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Fig. 7. Blemmye; Giant Serpents; Onocentaur, Wonders of the East, London, British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.xv, fol. 5v [102v] (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

In one sense, the single focus of these wonders, most clearly with the two- headed snake image in Vitellius, points to the single language, the native language, and the translation of the text and its wonders to that language. Ann Knock has argued that the Vitellius Wonders was probably taken from a source which, like Tiberius, contained both Latin and Old English texts.[25] Knock explains, furthermore,

In Tiberius B.v each paragraph of the Latin is followed by the Old English translation. All Old English sections except the first four lines of §6 are followed by an illustration. The omission of these four lines in Vitellius A. xv demonstrates that the scribe who provided the first single-language copy in Old English had located the translation by working backwards from the illustrations.[26]

Following Knock, then, if the Vitellius scribe both extracted the Old English text from a manuscript with parallel Old English and Latin texts, and used the illustrations to locate the Old English text, the focus within these Vitellius images on the single Old English text clearly underscores the selection of the native literary language.

But at the same time, these images, seen again most clearly with the two-headed snake cuts across the page from margin to margin, dividing one textual episode from the next. And while the merging of the serpent tongues or flames with the last letter of the textual description does point to the singularity of the language in contrast to the differences indicated in Tiberius, that merging also binds the text to the body of the wonder: as the wonders are familiarized, brought home, translated, the text is also made monstrous.[27]

Hence it is provocative, but not surprising that the phrase the serpent licks at with both of its upturned heads is ungefrægelicu deor.

The disruptive image of the two-headed serpent literally underscores the text’s description of the creatures’ incendiary untouchability, but at the same time the image actually touches the episode’s last word. The single focus of the snake heads, especially in the context of the Tiberius image, as we have noted, draws attention to the single language in which the text appears. The touch of the serpent tongues to the letter, however, also suggests what Derrida in “Des Tours de Babel” describes as the “infinitely small point of meaning which the languages barely brush” in the process of translation,[28] that is, that the interaction between image and text may figure translation. For Derrida, following Benjamin,[29] the question of translation begins—as for Isidore and other medieval geographers does the mapping of the world, including the wondrous East—with Babel. Derrida begins, “The ‘tower of Babel’ does not merely figure the irreducible multiplicity of tongues; it exhibits an incompletion, the impossibility of finishing … of completing something on the order of edification, architectural construction system and architectonics.”[30] Yet while Babel figures the impossibility of totalizing, it also promises in Benjamin’s terms the intimacy of a relation determined by “an original convergence.” Hence, for Derrida, in the transitory, or “fleeting” contact between texts during translation, the shared and “infinitely small point of meaning which the languages barely brush,” is the “promise” of another “kingdom” and the reconciliation of languages.[31] Derrida continues, “This kingdom is never reached, touched, trodden by translation. There is something untouchable, and in this sense the reconciliation is only promised. But a promise is not nothing.”[32]

As Isidore emphasizes in his discussion of the dispersal of languages and people after Babel, “The term ‘languages’ (lingua) is used in this context for the words that are made by the tongue (lingua).”[33] Here the tongues of the two heads touching the letter suggest the generation of language, in the terms of Isidore’s etymology, but also the generation of languages as dispersal from a once whole body, disruption of a once whole text. The relationship between text and image here thus reminds us that the Old English text itself as a translated text, however singly it is presented in this manuscript, carries across both its necessary difference from another language and the “fleeting” point of contact it makes with that language, both evidence of the dispersal of languages and perhaps the promise of their reconciliation. As such, it also reminds us that no translation, even into the native language can be “true,” as no language can be “true” in Derrida’s terms, a “pure language in which the meaning and the letter no longer dissociate,” or in the Augustinian sense in which:

when we speak what is true, i.e. speak what we know, there is born from the knowledge itself which the memory retains, a word that is altogether of the same kind as the knowledge from which it is born. For the thought that is formed by the thing which we know, is the word which we speak in the heart: which word is neither Greek nor Latin, nor of any tongue.[34]

At the same time, however, the Wonders text—with its acute recognition of dislocation, and the initiative of its stuttering insistence on the existence of its unheard-of creatures— also suggests the possibility, however fleeting, of a glimpse at such a truth.

References

| ↑1 | For dating and provenance of London, British Library, MS Cotton Vitellius A.xv, see Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995), p. 2; who follows David Dumville, “Beowulf Come Lately: Some Notes on the Palaeography of the Nowell Codex,” Archiv 225 (1988): 63; in dating it 997-1016. For more on the dating, see among other sources Elzbieta Temple, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles: Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts 900– 1066 (London: Harvey Miller, 1976), 72, no. 52; Colin Chase, The Dating of Beowulf (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1981); Kevin S. Kiernan, Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript, rev. ed. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 13-63; Audrey Meaney, “Scyld Scefing and the Dating of Beowulf— Again,” Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester 7 (1989): 7-40; Michael Lapidge, “The Archetype of Beowulf,” Anglo-Saxon England 29 (2000): 5-41. For the black-and-white facsimile, see The Nowell Codex: British Museum Cotton Vitellius A. XV, Second Ms., ed. Kemp Malone (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1963); and for a full color version, see Kevin S. Kiernan, Electronic Beowulf (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999). For the dating and provenance of London, British Library, MS Cotton Tiberius B.v, see Martin K. Foys, Virtually Anglo-Saxon: Old Media, New Media, and Early Medieval Studies in the Late Age of Print (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2007), 113-14. Foys dates the Cotton Map to around 1050 and locates it to Christ Church, Canterbury or perhaps Winchester. See also Temple, Survey, 104, no. 87, who dates it to the second quarter of the eleventh century and hypothesizes Winchester as its place of production. For the black-and-white facsimile, see P. McGurk, D. N. Dumville, M. R. Godden, and A. Knock, An Eleventh Century Anglo-Saxon Illustrated Miscellany (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981), 25. For further critique of the ‘rationalist’ approach, see Pamela Gravestock, “Did Imaginary Animals Exist?” in The Mark of the Beast: The Medieval Bestiary in Art, Life, and Literature, ed. Debra Hassig (New York, Garland, 1999), 119-35. |

| ↑3 | Caroline Walker Bynum, “Wonder,” American Historical Review 102 (1997): 1-26; idem, Metamorphosis and Identity (New York: Zone Books, 2001): 73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2171264 |

| ↑4 | William Latham Bevan and H. W. Phillott, Mediæval Geography. An Essay in Illustration of the Hereford Mappa Mundi (1873; rprt. Amsterdam: Meridian Publishing, 1969), 159; and Friedman, Monstrous Races, 5, among others. See Friedman, Monstrous Races, 212, n. 2, for detailed references. |

| ↑5 | Mary B. Campbell, The Witness and the Other World: Exotic European Travel Writing, 400-1600 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988), 73. |

| ↑6 | For example, Ælfric’s De temporibus anni, the Aratea, genealogies, the account of Sigeric’s journey to Rome, Priscian’s translation of Periegesis, the calendar. For the context of Tiberius, see McGurk, An Eleventh Century Anglo-Saxon Illustrated Miscellany, 15-24. |

| ↑7 | These passages are widely cited. See for example, Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Of Giants: Sex, Monsters, and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), xiv; and Lisa Verner, The Epistemology of the Monstrous in the Middle Ages (New York: Routledge, 2005), 2-5. |

| ↑8 | Vernor, Epistemology of the Monstrous, 156. |

| ↑9 | Wonders, fol. 2r. According to the foliation of Kevin Kiernan (Electronic Beowulf), the Vitellius Wonders of the East begins on fols. 95r-97r and continues through fol. 103v. In the foliation of Stanley Rypins, the Wonders begins on fol. 98b (97b) and continues through fol. 106b (Stanley Rypins, Three Old English Prose Texts in MS. Cotton Vitellius A.XV, Early English Text Society, o.s. 161 [London: Oxford University Press, 1924, 1971]). Given the confusion caused by the several different foliations of the manuscript, we will simply label the folios of the Wonders independently, beginning with the first, which we will identify as fol. 1v. Figure captions also include in square brackets the foliation numbers currently used by the British Library. Old English texts are from our own transliteration and translation of the entire Wonders of the East in the Beowulf Manuscript, under review). Stanley Rypins provides an edition of the Wonders in the Beowulf Manuscript. Stanley Rypins, ed. Three Old English Prose Texts in MS Cotton Vitellus A.xv, Early English Text Society, OS 161 (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 1924, unaltered reprint, 1998). For a more recent edition of the Wonders see Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995). English translations of the text are our own unless otherwise noted. Figure captions also include in square brackets the foliation numbers currently used by the British Library. |

| ↑10 | Wonders, fol. 2r. |

| ↑11 | Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 176. |

| ↑12 | Ibid., 180, 200. |

| ↑13 | On the tusked women, see the article by Dana Oswald in this volume. |

| ↑14 | Ann Knock notes that while pæt syndon ungefrelicu lyblac does not correspond to the Latin of the Bodley or Tiberius versions of the text, there are equivalents in the “untraced” Epistola Parmoenis ad Trajanum Imperatorem printed by J. B. Pitra and in the Old French version. Knock argues that given that “Pitra’s text shows the reading quia veneficae sunt and the Old French car eles son enuenimees,” the Old English of Vitellius “can thus reasonably be supposed to derive from the Latin original from which the translation was made” (Ann Knock, “The Text,” in McGurk, An Eleventh Century Anglo-Saxon Illustrated Miscellany, 94). |

| ↑15 | Orchard, Pride and Prodigies, 187. |

| ↑16 | The Dictionary of Old English Corpus (hereafter DOC) cites the Latin-Old English glossaries: John Quinn, “The Minor Latin-Old English Glossaries in MS Cotton Cleopatra A. III” (Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1956 ); with corrections by Manfred Voss, “Quinns Edition der kleineren Cleopatraglossare: Corrigenda und Addenda,” Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 14 (1989): 127-39. The DOC also cites the Latin-Old English glossaries: William Garlington Styker, ”The Latin-Old English Glossary in MS Cotton Cleopatra A. III” (Ph.D. diss., Stanford University, 1951), 28-367; with corrections by Manfred Voss, “Strykers Edition des alphabetischen Cleopatraglossars: Corrigenda und Addenda,” Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 13 (1988): 123-38. |

| ↑17 | The DOC cites, among others, Aldhelm, De laude virginitatis (prose) and Epistola ad Ehfridum: Louis Goosens, The Old English Glosses of MS Brussels, Royal Library 1650, Letteren en schone Kinsten van Belgie, Klasse der Letteren, 36 (Brussels: Verhandelingen van de koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, 1974); corrections by Hans Schabram, “Review of Louis Goosens, The Old English Glosses of MS Brussels Royal Library 1650,” Anglia 97 (1979): 232-6. |

| ↑18 | Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 614. C. M. Kauffman, A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles: Romanesque Manuscripts, 1066-1190 (London: Harvey Miller, 1975), 77, no. 38, dates this manuscript to 1120-1140. More recently, Alun Ford, “The ‘Wonders Of The East’ in its Contexts: A Critical Examination Of London, British Library, Cotton Mss Vitellius A.xv And Tiberius B.v, and Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms Bodley 614” (Ph.D. diss., University of Manchester, 2009), chapter 3, locates it to the Abbey of St. Martin, Battle, where it could have been copied from the Tiberius manuscript, which was sent there in the 1150s. |

| ↑19 | Nicholas Howe suggests, of the Tiberius and Vitellius Wonders, “This shared text encourages one to envision the two manuscripts as forming a discursive continuum that has the factual lore of Tiberius B v at one end and the narrative forms of Vitellius A xv at the other—in which the Wonders of the East occupies a midpoint that allows it to be read in differing ways depending on its manuscript context” (Nicholas Howe, Writing the Map of Anglo-Saxon England: Essays in Cultural Geography [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008], 155. |

| ↑20 | Ibid., 170. |

| ↑21 | Ibid. |

| ↑22 | Ibid., 176. |

| ↑23 | Ibid., 172-3: “The need to incorporate the outsider by eating its body and leaving the head to be mourned over suggests an extreme version of the ambivalence that characterizes many works that depict elsewhere: the foreign must be assimilated in an almost physical way so that it can be made part of the traveler’s body, and yet that act of incorporation can never be complete—the head remains—and becomes the object of regret to the traveler and so, by extension, to the reader as surrogate traveler.” Howe’s reading, to which we will return, problematically identifies the traveler, and the “reader as surrogate traveler” not with the traveler as represented by the text and image, but with the Donestre, the monster who eats the most obvious traveler figure. If we follow the text and illustration in their most explicit identifications, it is not the traveler who cannot incorporate the foreign, but the foreign which cannot wholly consume the traveler, although it can kill him. On the Donestre, see also the article by Rosalyn Saunders in this volume. |

| ↑24 | Ibid. |

| ↑25 | Ann Knock, “Analysis of a Translator: The Old English Wonders of the East,” in Alfred the Wise, ed. Jane Roberts, Janet Nelson, and Malcolm Godden (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1997), 123. |

| ↑26 | Ibid., 123, n. 9. |

| ↑27 | The Wonders further emphasizes the association of the monstrous with the foreign, and the foreign with language difference in its pejoration of the elreordig (6.6-15): “Donne is oI>er stow elreordge men beoo on. 7 I>a habbao cyni gas under I>ara is geteald. c. I>æt syn don I>a wyrstan men 7 I>a elreodegestan….” (Then is another place in which there are foreign-speaking men. And they have kings under them, the number of which is 100. They are the worst men, and the most foreign-speaking…) |

| ↑28 | Jacques Derrida, “Des Tours de Babel,” trans Joseph F. Graham, Difference in Translation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985), 189. |

| ↑29 | See Walter Benjamin, Essais: 1922-1934, trans. Maurice de Gandillac (Paris: Denoël, 1983). |

| ↑30 | Derrida, “Des Tours de Babel,” 165-207. |

| ↑31 | Ibid., 191. |

| ↑32 | Ibid. |

| ↑33 | Etymologies 9.1.2. See The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach, and Oliver Berghof (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 191. |

| ↑34 | Augustine, De Trinitate 15.10.18; “Necesse est enim cum verum loquimur, id est, quod scimus loquimur, ex ipsa scientia quam memoria tenemus, nascatur verbum quod ejusmodi sit omnino, cujusmodi est illa scientia de qua nascitur. Formata quippe cogitatio ab ea re quam scimus, verbum est quod in corde dicimus: quod nec graecum est, nec latinum, nec linguae alicujus alterius” (Patrologia Latina, ed. J. P. Migne [Paris: Gamier, 1844-55] 42:1071). English translation from Ruth Morse, Truth and Convention in the Middle Ages: Rhetoric, Representation, and Reality (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 179. |