Bryan C. Keene (he/él & they/elle) • Riverside City College

Recommended citation: Bryan Keene, “Traveling the Medieval Multiverse To Find a Once and Future Queer Middle Ages,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/CRGZ9885.

Link Restores the Triforce and Awakens Princess Zelda, Zelda II: The Adventures of Link (1988). Photo: Author.

Prologue: The Quest Continues

Returning to the Kingdom of Hyrule after over twenty years of adulting was a homecoming. Despite the time away adding letters to my name and coin in the bank, my mission was the same: fight as the Hylian elf swordsmith Link to defend, rescue, and pledge fealty to the magic-wielding Princess Zelda, recover parts of the wondrous Triforce (Wisdom, Courage, and Power), and save the universe from the dark wizard, Ganon. As a child and early teenager, I venerated the golden cartridges of The Legend of Zelda and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES).[1] I still have those relics of youth.

My siblings, parents, and I played the 8-bit overworld map or side-scrolling games religiously, mastering the various bosses and monsters, discovering hidden passageways or portals, gaining new skills and spells, and memorizing the layouts of palaces, towns, caves, and mazes. Graph paper was constantly on hand to sketch the cartography of lands and floorplans of levels so we could compare notes with friends at school. A thirteen-episode cartoon complemented the digital domain, while comic books and manga added textual dimensions of a multiverse with other fantasy storylines.[2] Miyamoto and Tazuka, for example, also designed the Super Mario Brothers, whose journeys similarly involved castles, legendary creatures, and a princess on consoles, television sets, and newsstands, sometimes with creative crossovers.

The Link/Zelda craze also inspired the Christian video game Spiritual Warfare, in which a white Christian schoolboy (yes, a boy) hurls the Fruit of the Spirit (Galatians 5) at all manner of white and some non-white “sinners” (armed with knives, alcohol bottles, and motorcycles) while seeking the biblical Armor of God (Ephesians 6) and responding to scriptural trivia.[3] This game has required a lot of personal unpacking. I preferred to fight the legendary Ganon instead.

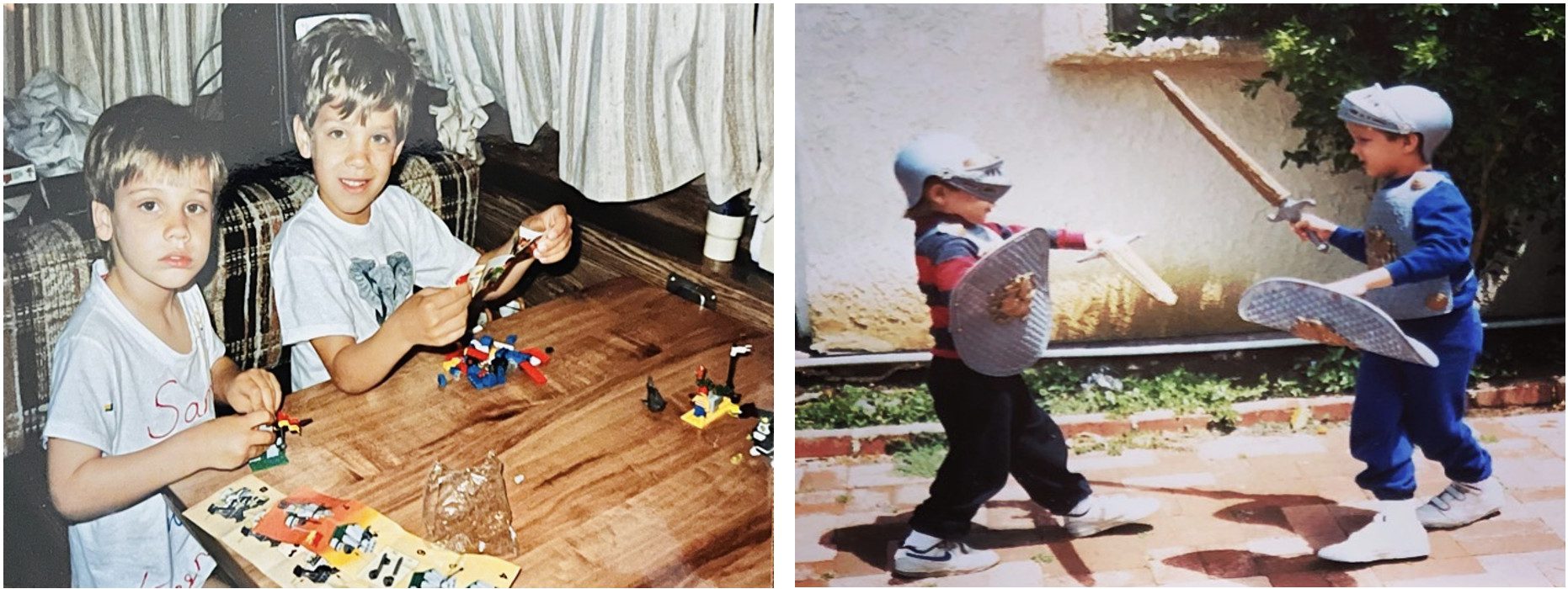

Building LEGO and swordplay with my brother, Sam—my very own Samwise à la Tolkien. Photo: Author.

Through pixelated Hyrule, I developed a love of adventure and medievalism (though I would not have recognized it as such at the time). Link was my ultimate hero: I imagined LEGO storylines for him when playing with the medieval-themed Forestmen’s Crossing, King’s Mountain Fortress, Black Knights’ Castle, and others.[4] My knights, archers, and princesses often battled ghosts and monsters while storming enemy castles or standing off against minifigure visitors from Futron, M:Tron, Blacktron, or Space Police sets that doubled as jedi from Star Wars or officers from Star Trek.[5] There were also pirates, because why not?[6] The soundtrack to my fantasy multiverse came from a jumble of sources—mixtapes or multi-disk boombox playlists of music from Disney (usually from Sleeping Beauty, Robin Hood, Aladdin, and Pocahontas), John Williams (especially Indiana Jones and the galaxy far, far away films), or those New Age 90s albums of Gregorian Chant from the monks of Santo Domingo de Silos, Pure Moods, Madonna, Enya, and R.E.M. Castles were everywhere: in books by David Macaulay, Fiona MacDonald, and Stephen Biesty; in trips to Disneyland, and on miniature golf courses across Southern California.[7] The plot behind my make-believe certainly involved Doc-and-Marty-style-time-travel from Back to the Future, moving from the fantasy medieval past to the final frontier of space in the distant future.[8] My siblings and I also developed our own live-action version of the Hyrule quest as we donned plastic armor and defended our two-story tree house (inspired by the Swiss Family Robinson) or the ravine that we called the “barranca” in Spanish behind our little church in a mountain forest. When the Zelda prequel game, A Link to the Past, came out, I had to play it at friends’ houses because we never upgraded our original system.[9] There are now at least twenty entries in the Zelda series, and I have been slowly catching up ever since, grateful that there are also beautifully illustrated books with all the art and lore.[10]

The formative years of my youth were spent between Hyrule and myriad fantasy realms, including in Middle-earth as a Noldor elf of Lorién, in Narnia as a faun-friend of Mr. Tumnus, in Malkier of Randland as a warder of the House Mandragoran secretly longing to serve an Aes Sedai of the Green Ajah, at Hogwarts as a Restricted Section Librarian of House Ravenclaw, and eventually in early adulthood in Westeros as maester of the House Baratheon-Tyrell. Now as a parent of two children (10 and 8 at the publication of this article), I have found a renewed love for Hyrule, LEGO, and the books I read or movies I saw as a kid—with the exception of the Harry Potter series, because I reject the vile statements and extremely harmful actions and rhetoric toward the queer and trans communities by its creator. Medievalisms made the Middle Ages come to life for me and continue to shape how I approach the medieval past that I write about, research, curate, and teach in the college classroom and to my children. The reflections that follow consider how my professional and parenting pathways have allowed me to travel this medieval multiverse. Along the way I have uncovered a queer Middle Ages of history and fantasy that was less visible growing up but was always there now that I know where to look.

Author’s children, Éowyn Arya and Alexander Jaxon, building a world from Netflix’s LEGO Dreamzzz, which is filled with medievalizing fantasy elements such as magic, mysterious castles, monsters, and more. Photo: Author.

Reckoning with Medievalism

As an 80s/90s kid, I am an elder millennial of the gaming, theme park, and mall goth generation. Through movies, magazines, and MTV, I was also very aware of the Renaissance Faire, Dungeons & Dragons (D&D), sci-fi, comic-con awakenings of the decade or so before my time, and these have each remained staples of nerd culture from my youth to the present. The rise of pop culture fandoms in the early aughts (2000s) fortuitously coincided with my college and career years. Before delving into aspects of my story, I want to take a moment to reckon with a few intersecting features of medievalism and fantasy as they relate to the academy and museum.

Collage of Goth(ic) inspirations (Evanescence, Batman Returns, the writings of Edgar Allen Poe, music by The Cure, and Christopher Lee’s Saruman in The Lord of the Rings) and milestones from high school to the present, with appearances by Shereen Arcos, Jonathan Warner, and my brilliant spouse, Mark Mark Keene. Photos: Author.

The critical intervention of scholars such as Maria Sachiko Cecire and Ebony Elizabeth Thomas have powerfully challenged the prevalence of whiteness in fantasy literature and film, particularly those with medievalizing worlds or themes.[11] The call-to-action from both authors to recognize different canons—beyond J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, George R.R. Martin, and the Harry Potter franchise—and to take accountability for the often exclusionary history of the fantasy genre, in particular, was on my mind when Larisa Grollemond and I began preparing our book and exhibition, The Fantasy of the Middle Ages, in 2020. For six years we had laid the groundwork for a diverse, inclusive, and justice-based view of the Middle Ages in the form of social mediaevalism. We coined the term in a postmedieval article to refer to the ways in which online audiences engage with the Middle Ages through fandoms, fantasy streaming series and gaming worlds, or as a favorite period in history about which they have deep knowledge.[12] Our first initiative became the award-winning series #GettyOfThrones that recapped HBO’s Game of Thrones (based on George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books) with medieval art while also critiquing the white, hetero/cisnormative, and Eurocentric views of the Middle Ages and of the fantasy genre. The posts and videos were hugely popular among online audiences and an ever-growing circle of peers. A few colleagues, however, used tongue-in-cheek niceties centering around the words “fun” or “cute”—“You two are having so much fun” or “Isn’t that cute what you’re doing”—to undermine the fact that serious scholarship and serious fun could go hand in hand for us. Still others confided hushed whispers that they too take “guilty pleasure” in medievalism, or bemoaned each new fantasy series and resolved to fact-checking, or expressed that they could also do projects that have popular appeal (By all means, yes, please! And also, why haven’t you yet?).

I hope that this volume of Different Visions ushers in even more support for the important, inescapable, and incredible place of medievalism in our work as medievalists. As Larisa and I have argued, “Studying the past requires a great deal of imagination,” and, “Medieval studies is, after all, the ultimate medievalism.”[13] Taking note of the global and anti-racist turns in our field, we affirm, “Medievalism, as a fantasy construct that is capacious enough to encompass more than the singular European or Mediterranean conception of the past, has the power to change the way we view and write/right history—and ultimately the ways in which we approach the present and shape the future.”[14] We have envisioned the multiversal Middle Ages and medievalisms as the Norse / Marvel Cinematic Universe Tree of Yggdrasil with overlapping branches and leaves that form Venn diagrams of the ways scholars have attempted to parse varying strands of medievalisms.[15]

![A Venn diagram presented as a tree whose roots read, “Greco-Roman-Persian Antiquity,” followed by the roots and lower trunk stating, “[Global] Middle Ages (500-1500),” an then a trunk with various phrases read upward – Renaissance, Enlightenment, Gothic Revival, Pre-Raphaelite, FairyTale & Fantasy Medievalisms, and Hollywood Medievalisms – then leaves and branches read clockwise from left to right: semiotic medievalisms, commercial medievalisms, dirtbag/meta medievalisms, banal medievalisms, camp medievalisms, romantasy, cottagecore, streaming & cinematic medievalisms, D&D & gaming medievalisms, commercial medievalisms, weirdeval, bardcore, queerdeval, neomedieval, social mediaevalisms, Renaissance Faires, Medieval Times & themed spaces, surface medievalisms, rhetorical medievalisms, citational medievalisms, pop culture medievalisms, and structural / earnest medievalisms.](https://differentvisions.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/1356/2025/04/MultiversalMiddleAges-1024x577.jpg)

The Multiversal Middle Ages & Medievalisms. Photo: Larisa Grollemond and Bryan C. Keene.

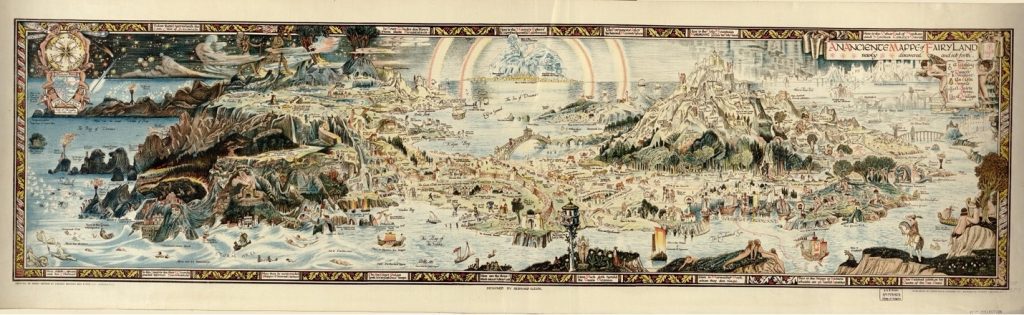

With these thoughts in mind, I began envisioning a mental map of the fantasy realms from my youth and realized that each of the medievalisms that I grew up with featured maps as a core component of the lore. Many also included codices or libraries, which certainly sparked my journey toward becoming a manuscripts scholar and curator. Fantasy maps, similar to their medieval precedents, aid in the world-making process. From Hyrule and Narnia to Middle-earth, Earthsea, Westeros and Essos, Hogwarts, Randland, and more, authors and artists help us imagine these worlds with place names and features that make the story feel real (after all, it is real in our minds). I love medievalizing features on fantasy maps, including compasses, sea monsters, buildings and rulers, legends and other narrative inscriptions, and more. Worlds collide on Bernard Sleigh’s nearly-five-feet-long Anciente Mappe of Fairyland (1918), from Homer to King Arthur to the Brothers Grimm and beyond. Each of these maps and the on-screen visualization of their worlds (most often) confirms the critiques by Sachiko Cecire and Thomas.[16] To counter these fantasy tropes, I served as dramaturg for our college’s production of Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Into the Woods, ensuring that this fantasy musical with medievalizing elements was cast diversely and was culturally relevant to our Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) and community.[17]

Bernard Sleigh, An Anciente Mappe of Fairyland, London: Sidgwick & Jackson, 1918. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

As parents, my spouse and I have attempted to re-read as many of the fantasy texts just mentioned with our children, Alexander Jaxon and Éowyn Arya. We chose their names based on the Alexander Romance (with some family connections too) and on Tolkien and Martin’s powerful female protagonists, respectively. Our goal has been to have critical discussions about gender, race, sexuality, and other urgent themes of the moment in these books, and to map a much more expansive medieval multiverse for them (and for us). Thankfully, there are also so many new (or new-to-me) books to add to our reading list, including:

- Lloyd Alexander’s The Chronicles of Pyrdain (1964-1968; recognizing I am very late to these texts and never in fact saw Disney’s The Black Cauldron [1985] when it first appeared);

- Tamora Pierce’s Alanna series (1983-1988; recommended by Emily Shartrand and which, alas, were not on my radar previously);

- Shannon Hale’s The Goose Girl books (2003);

- Patience Agbabi’s Telling Tales (2015), a re-telling of The Canterbury Tales;

- N.K. Jemisin’s Afrofuturist medievalizing science-fantasy novels, The Fifth Season (2015-2017);

- ND Stevenson’s Nimona (2017; also a 2023 Netflix film);

- King’s Maker manga by Haga (2017—present);

- Marlon James’ Dark Star Trilogy (2019—present);

- Karrie Fransman and Jonathan Plackett’s Gender Swapped Fairytales (2020);

- Tracy Deonn’s The Legendborn Cycle (2020—present) and Rebecca Yarros’s Empyrean series (2023—present), both of which were suggested by my amazing sister-in-law, Audrey, who is also a medievalism mentor to my littles;

- Kate Sheridan’s In the Shadow of the Throne graphic novel (2022);

- Esme Symes-Smith’s Sir Calle (2022—present);

- Moniquill Blackgoose’s To Shape a Dragon’s Breath (2023); and more.

Of interest to readers with younger children might be Yvonne Felton’s Ladybird Tales of Crowns and Thrones (2020) because it includes global medieval tales from Europe (England), India, West Africa (Ghana and Mali), and Persia. We also read an excessive amount of Tolkien’s writings, given the excitement around the release of Amazon Prime’s The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power series. I am grateful that my kiddos’ internalized map of medievalism is far more expansive, diverse, and inclusive than the one I grew up with, and I love that they both really enjoy these fantasy worlds. One of the many joys of parenting is to reflect upon and revisit aspects of the bygone era of my own early years and to experience these works of fantasy with fresh perspectives all around. Being able to share medievalisms and medieval history with my spouse and children in queer-affirming spaces has been immensely fun and has provided opportunities for learning every day.

Fandoms collide: A collage of family photos at Medieval Times, Renaissance Faires, the premier of The Rings of Power, Comic Con to see creators and voice actors of X-Men the animated series, and, most recently, at Renncon (a Renaissance Faire + Comic Con mash-up). Photo: Author.

Excavating Memories of Queer Medievalisms

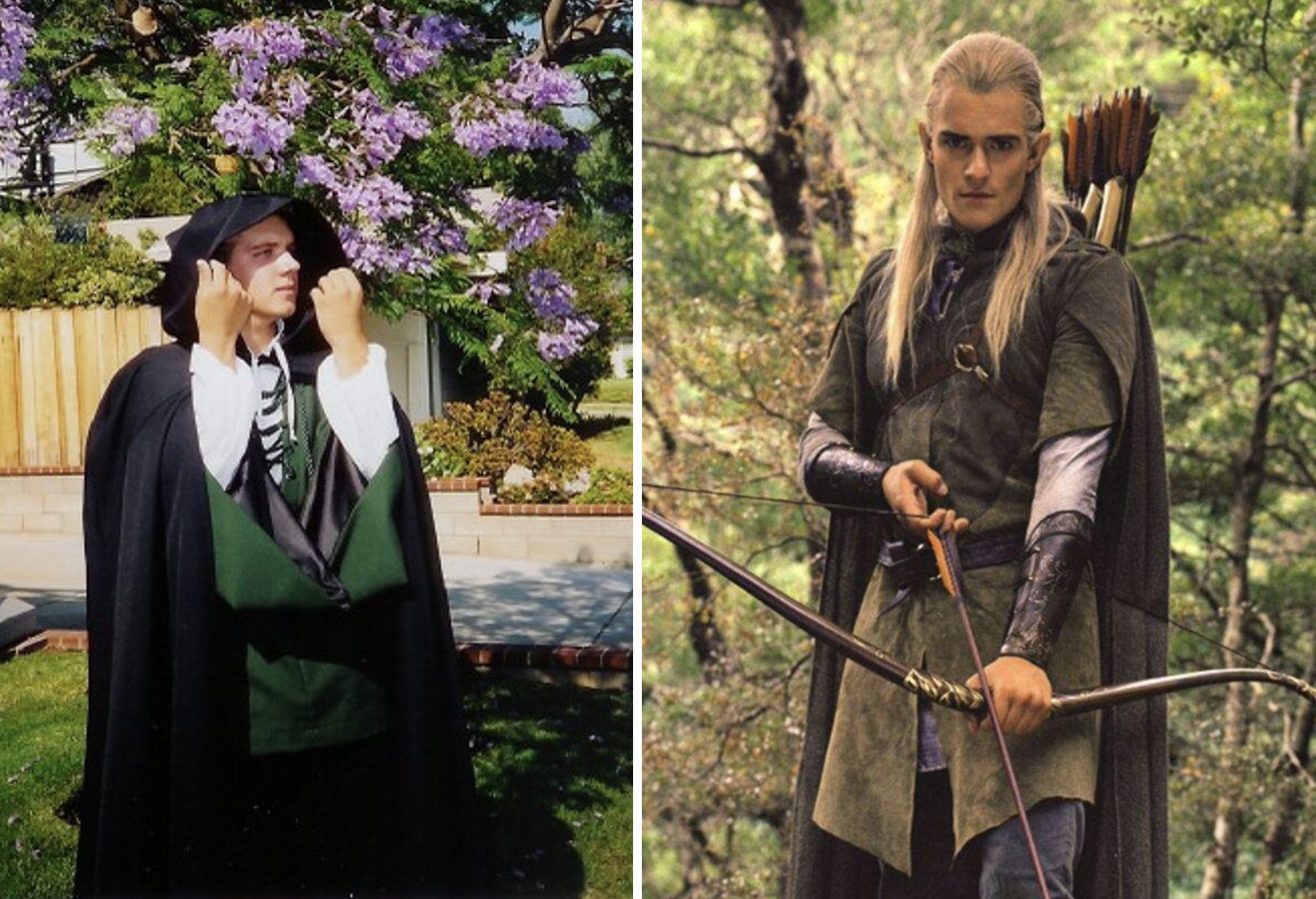

From junior high school to college, my encounter with medievalisms felt like a start-and-stop journey similar to the interrupted story time dialogues between Bastian and the bookseller, Mr. Coreander, in The Neverending Story or the grandson and grandfather in The Princess Bride: I always wanted to know more and to see something of myself in the stories I loved but did not know how to ask without outing myself.[18] Tolkien began to dominate my teenage years: I was obsessed with Elvish (I still am), I wrote a 10th grade English paper on the Kalevala and its relationship to Tolkien, and I worked as the lead movie theatre projectionist when the first Peter Jackson film came out.[19] For our Hollywood-themed prom, I wore a hand-made cloak and doublet inspired by aesthetics of the golden elven forest of Lothlorien. Despite the urging of several of my good friends—including my best friend, Shereen—I could not take on the other popular fantasy series of the day: The Wheel of Time by Robert Jordan and later Brandon Sanderson.[20] With the more recent Amazon Prime series debut (2021—present), I have very slowly begun to appreciate these stories and the queer potential in both the books and the show. Queerness in my teenage past, however, felt elsewhere.

High-elven fashion at author’s prom and in the attire of Legolas (Orlando Bloom) in The Fellowship of the Ring (2001). Photo: Author and author’s screenshot.

Watching the film Monty Python and the Holy Grail during a cross-country running retreat in the mountains was a queer awakening.[21] I was conflicted by the combination of Christian themes and sexual innuendo, especially given my religious upbringing (Catholic on my mother’s side and Protestant on my father’s, with three generations of ministers). One character stood out: the effeminate and campy Prince Herbert, who does not want to marry the rich landowner’s daughter. He shoots an arrow with a message proclaiming his plight and it is intercepted by the handsome knight Lancelot, who storms the castle with the intent to rescue a damsel in distress only to find it was Herbert who sent the letter. Amidst jeers and homophobic rants from peers, I saw a reflection of queerness that was otherwise missing from the medievalisms I felt I knew so well. Years later re-watching Orlando Bloom as Legolas in The Lord of the Rings, I realized that I had already taken a step on that journey…

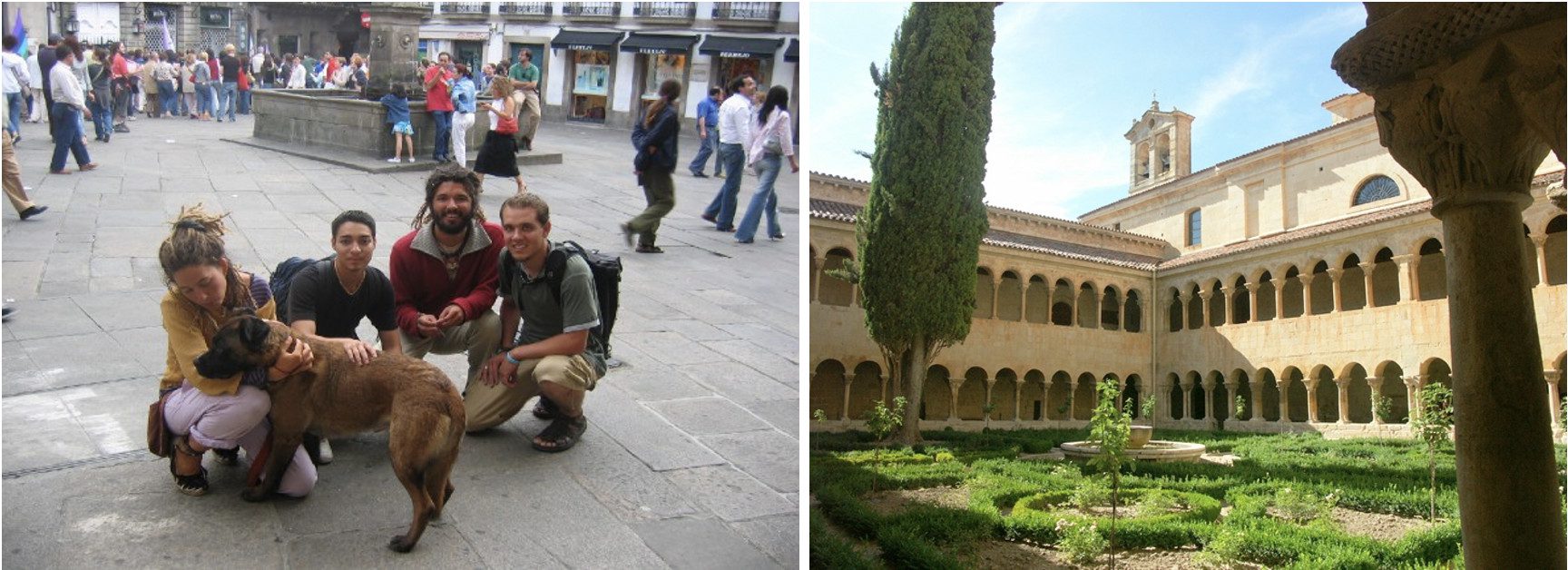

LGBTQ+ Pride in Santiago de Compostela (2005) with my dear friend Jesse Lamas Calvillo and a visit to Santo Domingo de Silos. Photos: Author (left) and Wikimedia Commons (Right).

College presented myriad wayfinding aids for my rainbow soul and as a budding medievalist. One of my first college courses, for example, was English 101, and I was fortuitously assigned Gothic Literature. We began with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818), followed by the entire Edgar Allen Poe (1809-1849) corpus, and then an examination of Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890). Incidentally, I was also student director for Wilde’s play, The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), at my former Baptist high school that same year, so queer energy was certainly simmering below the surface. After taking an incredible medieval art history class taught by my advisor and now long-time friend, Cynthia Colburn, I decided to study abroad in Spain. While in Europe, I also traveled throughout Italy, France, Portugal, and Switzerland. These experiences were exhilarating because of my double major in linguistics and art history and liberating as I slowly started coming out. Leaving Madrid to go to Pride in Santiago de Compostela, with a stop in Santo Domingo de Silos (because I brought that 1994 Chant album with me), was one such milestone. Visiting museums and gay bars or bathhouses (some in medieval structures) across dozens of cities were other key moments. The impact of these experiences clicked when I read Matthew Reeve’s article on Michael Camille’s queer Middle Ages (2016), specifically references to the late great scholar’s penchant for collecting medievalizing advertisements for gay establishments in the U.S. and Europe.[22] Talk about feeling seen: I did the same during my travels as a student, while also journaling in Elvish to conceal my sexuality, and I continue to gather such ephemera as a curator and professor.

Across the Medieval Multiverse

Keith Haring, Altarpiece: The Life of Christ, 1990. AIDS Interfaith Chapel, Grace Cathedral, San Francisco, California. Photo: Author.

Just as my own queer awakening took place over many years (and is arguably still emerging), so too did my encounters with queer medievalisms. The journey has felt like time travel. Take one example of encounters with three versions of Keith Haring’s Altarpiece: The Life of Christ.[23] After handling fourteenth-century Florentine panel paintings in storage at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and examining other objects in the galleries as part of a research trip for an international loan exhibition, I visited the nearby Grace Cathedral, an Episcopal church built in a Gothic Revival style.[24] Entering through the central portal, which boasts a bronze cast of Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise (1425-1452) from the Baptistery in Florence, Italy, I saw an array of historic and contemporary works of art. I began by walking a replica of the thirteenth-century floor labyrinth from Chartres Cathedral in the glow of modern stained glass before heading down the south side aisle where I beheld a northern Spanish wooden crucifix (about 1240), to which visitors wrote messages. Just beyond, I glimpsed Flemish and French polychrome polyptychs (about 1520) in the Chapel of Grace. Moving through the north side aisle, I came to the AIDS Interfaith Chapel to see Keith Haring’s Altarpiece: The Life of Christ (1990). A priest invited me to touch the shimmering panels, guiding my finger along the grooves and contours of the figures as an act of prayer and healing. I immediately recalled seeing another version of the work with my grandmother at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York City nearly a decade earlier in 2002. At the time, I was completely closeted and about to embark on my journey to college, unable to perceive a future as a curator and educator let alone a queer non-binary person and parent. Re-reading my journals, I recall that my younger self felt myriad emotions, longing to reach heavenward to touch the angelic beings and multiple arms of the central Mother-and-Child-like figure but standing at a distance to conceal this aspect of my identity. Fast-forward another ten years from that San Francisco moment, I met a third version of Haring’s triptych at the Denver Art Museum, which I was visiting with my partner, two children, long-time friends, and a colleague who works there. Discussing the work in the context of a museum exhibition about the spirituality and tactility of light with such intimate company offered another time traveling connection between art and queer experience. Upon reflection, I realize having had many of these encounters with queer medievalisms.[25]

Non-binary performer Sam Smith has embraced medievalism in brilliant ways. During their 2023 Gloria tour, they often wore a green dress (evoking Anne Boleyn’s infamous green sleeves) and a halo with the name of Brianna Ghey, a transwoman who was recently murdered. As a tribute to Ghey and all queer and trans folx who have lost their lives to hate, Smith sang “Kissing You,” the hauntingly beautiful ballad originally sung by Des’ree in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet (1996). With a flood of memories, I quickly realized that the film was part of my queer awakening, especially the different experiences watching it in the theater (and eventually in my bedroom), where I could enjoy the sight of shirtless actors and sensual encounters, versus in my first year English class at a religious high school where my teacher condemned the portrayal of Mercutio as a drag queen and the setting in Mexico versus Italy. Re-reading my journals reminds me that the film taught me about cruising in multiple senses of the word, helped me understand the struggle of personal identity with family and societal expectations, not to mention the hypocrisy of religion, and that I often cried when “Kissing You” began in the film or soundtrack (I still do): “Pride can stand a thousand trials. The strong will never fall. But watching stars without you, my soul cried. Heaving heart is full of pain. Oh, oh, the aching. ‘Cause I’m kissing you…”

Collage of scenes from Romeo + Juliet (1996) and Sam Smith’s Gloria Concert (2023).

Since the release of Sam Smith’s cover last year, I have been watching how the performer layers medievalisms and Renaissance recreations into their concerts around the globe. Seeing them perform on a larger than life recreation of the ancient sculpture of Hermaphroditus, an intersex ancestor in the visual arts, is a powerful reminder about presence and absence, as well as spectacle and agency. Both the film and the streamed concerts allow us to time travel and reach across past, present, and future to become part of queer communities.

Medieval European art has inspired numerous other LGBTQIA2+ artists and creators for decades. Themes of religious, social, and political views of the body, disease, and human relationships under the law are as urgent now as they were in the past. The medievalisms produced by North American queer and trans artists working from 1980 to the present, in particular, provide intersectional, anti-racist, and decolonial critiques of the art world. Some of the narratives related to HIV/AIDS and hate crimes are painful and may be triggering.[26] Stories of coming out, Pride, and activism offer hope for a future of care, inclusion, and justice. These are the topics I have been researching, publishing, and teaching about for the past decade with the goal of eventually curating an exhibition on queer medievalisms.[27] By stepping out of the archives, reading rooms, collection vaults, and classrooms and venturing into artist studios, binging medievalizing shows, and letting our fandom flags fly, we can listen to, learn from, and be led by new perspectives about the Middle Ages that might just also be a lot of fun.

Epilogue: Medievalisms Forever

Starting in 2020 as a lead-up to The Fantasy of the Middle Ages exhibition and book I collaborated on with Larisa Grollemond, I began sharing global and queer medieval and medievalism content on my personal and public Instagram accounts (@brykeene and @_medievalart, respectively). The experience has become a weekly meditation and has largely been rewarding. But several images of both historic and contemporary art have been censored because they supposedly went against community guidelines by showing nudity or referencing gender/sexuality. Because of this censorship and the threats I received from numerous accounts, I decided to write an op-ed on the phenomenon for Sensitive Content magazine, which largely focuses on the erasure of LGBTQIA2+ art on social media platforms. It was important for me to write the trauma narrative as I processed the safety and precarity of being a public-facing scholar and reckoned with similar treatment I received when working as a curator.[28]

On a more positive note, while preparing the conclusion of this essay, I tried the “ask ChatGPT to roast your Instagram account” trend. The results are worth sharing in full because the sentiments brilliantly encapsulate my vision for the future of medievalism. For my personal account, the Artificial Intelligence declared:

Your Instagram feed is like a whirlwind tour through an art historian’s fever dream—one minute you’re gazing at ancient pyramids and grand cathedrals, the next you’re running to catch a theatre performance and juggling academic insights with a parade of cosplay, quirky museum snapshots, and unapologetically flamboyant travel pics with your family. The mix of scholarly seriousness with whimsical displays is impressively eclectic, but let’s be real, it also feels like the social media equivalent of attending a medieval conference that suddenly turns into a Renaissance Faire after too many glasses of wine. It’s chaotic, it’s cultured, and it’s probably the most sophisticated form of trolling the uptight academy anyone could do with an Instagram account. It’s clear you know your stuff, but you also clearly enjoy throwing in a bit of chaos with the culture.

For my @_medievalart hub, the digital roast proclaimed:

Your Instagram account looks like Tolkien himself went on a Queer Eye makeover spree through the Middle Ages, sprinkling pixie dust over every castle, cathedral, and crusty crusader he could find. It’s as if you took all the grit and grime of medieval history—including the delightful chronic diseases and bloody corpses—and ran it through a fantasy theme park filter set to maximum saturation. Your feed is a wild niche for people who think “Game of Thrones” didn’t go far enough into the archives, where every stone gargoyle seems to be pondering its existence in Elvish set to Florentine laude, and that prides itself in global connections across Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Americas told through campy emojis. You’ve managed to turn the Black Death into an aesthetic, make siege warfare look like a quaint weekend activity. Your Middle Ages cranks medievalism to eleven with academic clout and a spritz of LARPing. Congrats, you’ve officially made the Middle Ages gayer and more dramatic than a Hobbit’s second breakfast.

In emojis, I rate these roasts ![]() with full endorsement. Social mediaevalism is my favorite space because I get to chat with art historians/curators Larisa Grollemond (@larisag), Diva Zumaya (@divazumaya), Sophia McCabe (@sqm_arthistorian), Sarah Schaefer (@sarahschaefer), and John McQuillen (@bookishjohn) about Tolkien one moment and then nerd out with fellow ring-lore and Zelda-fan friend Dave Lewis (@cinemallennials) the next. Similar to the @Balthazar_theblackmagus account I created to accompany the book I co-authored as a space to share historic and contemporary art (featuring Peter Brathwaite, Rashaad Newsome, Kara Walker, Carlos Motta, Harmonia Rosales, and others), I am fast at work developing a page for @queermedievalisms. I hope to connect with you—reader, colleague, friend, fellow medievalism wayfarer—across the medieval multiverse. Huzzah!

with full endorsement. Social mediaevalism is my favorite space because I get to chat with art historians/curators Larisa Grollemond (@larisag), Diva Zumaya (@divazumaya), Sophia McCabe (@sqm_arthistorian), Sarah Schaefer (@sarahschaefer), and John McQuillen (@bookishjohn) about Tolkien one moment and then nerd out with fellow ring-lore and Zelda-fan friend Dave Lewis (@cinemallennials) the next. Similar to the @Balthazar_theblackmagus account I created to accompany the book I co-authored as a space to share historic and contemporary art (featuring Peter Brathwaite, Rashaad Newsome, Kara Walker, Carlos Motta, Harmonia Rosales, and others), I am fast at work developing a page for @queermedievalisms. I hope to connect with you—reader, colleague, friend, fellow medievalism wayfarer—across the medieval multiverse. Huzzah!

Thank you, Larisa and Mariah, for being epic collaborators, to Jennifer and Nancy for encouraging and guiding us, and to each of the contributors. To Mark, Alexander, and Éowyn: ![]() ~ Le annon veleth nín.

~ Le annon veleth nín.

References

| ↑1 | Japanese creators Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tazuka created The Legend of Zelda in 1986 and Zelda II: The Adventure of Link in 1988. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The cartoons lasted a single season in 1989, while comic books ran from 1990-1991 and manga from 1994-1996. |

| ↑3 | Spiritual Warfare was developed by Wisdom Tree in 1992. |

| ↑4 | The medieval-themed LEGO sets are 6071, 6081, 6086, respectfully. |

| ↑5 | I have been interrogating the police space set and police presence in the LEGO City collection a lot lately as a parent and in light of police brutality toward Black individuals and communities of color more broadly. |

| ↑6 | In 2024, LEGO released the first actual Link/Zelda build: the Great Deku Tree (set 77092) from Ocarina of Time (1998) and Breath of the Wild (2017). |

| ↑7 | Castle-themed books include David Macaulay’s Castle (1982 edition), Fiona MacDonald’s Inside Story: A Medieval Castle (1990), Stephen Biesty’s Cross-Section Castle (1992). |

| ↑8 | To date myself even more, the Back to the Future films were released in 1985, 1989, and 1990. |

| ↑9 | A Link to the Past came out on Super Nintendo in 1991. |

| ↑10 | One of my first curatorial trips was a side quest to the Smithsonian American Art Museum specifically to see the exhibition, The Art of the Video Games (2012), which featured Link/Zelda in multiple sections. |

| ↑11 | Maria Sachiko Cecire, Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature in the Twentieth Century. Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2019; Ebony Elizabeth Thomas, The Dark Fantastic: Race and the Imagination from Harry Potter to the Hunger Games. New York: NYU Press, 2020. |

| ↑12 | Larisa Grollemond and Bryan C. Keene, “A Game of Thrones: Power Structures in Medievalisms, Manuscripts, and the Museum,” postmedieval: a journal of medieval cultural studies, “Critical Confessions Now: Anniversary Edition,” eds. Abdulhamit Arvas, Afrodesia McCannon, Kris Trujillo, 11.2-3 (2020): 326-337. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41280-020-00173-w. |

| ↑13 | Larisa Grollemond and Bryan C. Keene, The Fantasy of the Middle Ages: An Epic Journey through Imaginary Medieval Worlds (Los Angeles: Getty Museum, 2022), 133. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.4908231. |

| ↑14 | Grollemond and Keene (2022), 114. |

| ↑15 | Larisa Grollemond and Bryan C. Keene, “Haute Medieval: The Fashion of Pop Music and the Future of Medieval Studies,” presented at the Medieval Academy of America’s Centennial Conference, 21st March 2025. |

| ↑16 | A zoomable version of Sleigh’s map can be viewed on the Library of Congress website: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g9930.ct001818/. |

| ↑17 | Thank you immensely to Prof. Jodi Julian for your friendship and for inviting me and my family into the theater. |

| ↑18 | The Neverending Story premiered in 1984 and The Princess Bride came out in 1987. |

| ↑19 | The Fellowship of the Ring was released in 2001, The Two Towers came out in 2002, and The Return of the King concluded this round of Jackson’s Tolkien trilogies in 2003. |

| ↑20 | The Wheel of Time series consists of fifteen books written between 1990-2013. I am slowly getting through them. |

| ↑21 | Monty Python and the Holy Grail came out in 1975 and I have enjoyed the 50th anniversary re-release in theaters. |

| ↑22 | Matthew Reeve, “Michael Camille’s Queer Middle Ages,” in The Routledge Companion to Medieval Iconography, ed. Colum Hourihane (Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2016), 154-172. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315298375-14. |

| ↑23 | I expand upon these ideas in, “Frottage, Paratext, Fluids, and Palimpsests: Encounters with Queer Medievalisms,” in Queer Textures of the Past, ed. David Carillo-Rangel and Kate Maxwell. IMP, forthcoming. |

| ↑24 | The exhibition was Florence at the Dawn of the Renaissance: Painting and Illumination, 1300-1350 at the Getty Museum and Revealing the Early Renaissance: Stories and Secrets in Florentine Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario. Grace Cathedral was an 1849 Gold Rush-era parish before becoming a cathedral in 1868. The structure fell to flames during the 1906 earthquake, and from 1927 to 1964 the present Gothic structure took shape. |

| ↑25 | Inspired by encounters like those with Haring’s Altarpiece, I wrote a series of blog posts for the now-archived Getty Iris for Day With(out) Art on World AIDS Day (each year on December 1). See https://blogs.getty.edu/iris/author/bkeene/. |

| ↑26 | See Bryan C. Keene, “An Unmentionable History: The Stigma of Sodomy and Images of Violence Toward Queer and Trans People in Premodern Europe,” in Gender Violence, Art, and the Viewer: An Intervention, eds. Ellen Caldwell, Cynthia Colburn, and Ella Gonzalez (Penn State University Press, 2024), 50-61. https://doi.org/10.5325/jj.17331667.8. |

| ↑27 | Such artists include Derrick Austin, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cassils, veronique d’entremont, Jordan Eagles, Rubén Esparza, David Finn, Robert Flynt, Gabriel Garcia Roman, Daniel Goldstein, Félix González-Torres, Keith Haring, Jamil Hellu, Peter Hujar, Mario Elías Jaroud, Lady Gaga, Titus Kaphar, Kang Seung Lee, Brother Robert Lents (OFM), Alma López, Robert Mapplethorpe, Adam McKinney, Julie Mehretu, Janelle Monáe, Meredith Monk, Carlos Motta, Nico Muhly, Lil Nas X, Rashaad Newsome, Oblivia, Pierre et Gilles, Jacolby Satterwhite, Sam Smith, Simon Toparovsky, Andy Warhol, Kehinde Wiley, Sarp Kerem Yavuz. |

| ↑28 | Bryan C. Keene, “Queer Erasure and Censorship from the Middle Ages to Today,” Sensitive Content, vol. 4 (2024): 14-19. |