Karen Overbey

August 31, 2018

**This post was revised on September 9 in response to a critique by Dr Sierra Lomuto that I ignored the work of medievalists of color in the original post. She’s right — I did. And I sincerely thank Dr Lomuto for bringing this to my attention.**

As I prepare for another First Day of Class, I’m thinking about the last-minute changes I made to my syllabi a year ago, after the violent events in Charlottesville, Virginia. In the unlikely case that you need a reminder: last August, protesters gathered in Charlottesville to call for the removal of the statue of Robert E. Lee from Emancipation Park. Far-right wing groups — neo-Nazis, Klansmen, and several militias, many carrying torches or rifles, shouting racist and antisemitic slogans, rallied in a counter-protest in the hopes of uniting the white nationalist movement in America. In addition to Confederate flags, the white supremacists carried shields and banners with runes, “Celtic” crosses, and “Viking” eagles. Media coverage of the riots was a catalyst for many medievalists, especially for scholars of medieval Britain, Ireland, and Scandinavia, to examine the ways in which these images came to be used by white supremacists.

Last year, spurred by Dorothy Kim’s essay, “Teaching Medieval Studies in a Time of White Supremacy,” I showed some images from Charlottesville on the first day of class, and talked to my students about dangerous misappropriation — both the “Celtic” cross and the “Viking” eagle, as the linked posts above make clear, have been distorted in the service of white supremacist ideology. (Spoiler: the eagle is really the emblem of the Theban Legion.) I also revised my syllabus for Medieval Architecture to include sessions on Africa (a discussion of Henry Louis Gates, Jr’s documentary episode on the building of Great Zimbabwe), added a third day on Islamic Spain, gave half a lecture to synagogues and another half to medieval prisons. I’ll do those things again this year, but I’m also looking for more ways to teach an inclusive, diverse, and complicated Middle Ages. I’m looking deeper, interrogating the histories that allowed ‘medieval’ to so easily mean ‘white,’ and examining my own complicity in promoting those histories. I’m being transparent about my pedagogy, and addressing this material directly and honestly with my students.

Of course, some medievalists, especially medievalists of color, have been working on this and related issues for years. Sierra Lomuto wrote in December 2016 about the role of medieval iconography in white supremacist rhetoric, and showed the dangers of an image of the Middle Ages as a “preracial space where whiteness can locate its ethnic heritage.” Dorothy Kim has written widely about medieval studies’ entanglement with white supremacy. Earlier this year, Jonathan Hsy noted the use of medieval iconography in anti-Chinese violence in the nineteenth century. And the collective Medievalists of Color has held conference workshops on Whiteness in Medieval Studies. (The crowdsourced bibliography on Race and Medieval Studies, which has been noted on this blog before, is available here.)

But there is less discussion of racism in medieval studies in my field, Art History. There’s a short bibliography here – this includes the ongoing series The Image of the Black in Western Art, which includes two volumes on the medieval period, and Madeline Caviness’ 2008 essay, “From the Self-invention of the Whiteman in the Thirteenth Century to The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly.” So I’m sharing this (long!) post, which is based on a couple of invited talks I gave this Spring, one at a conference at Harvard and the other at the Menil Collection. The first part of the essay draws on, repeats, and amplifies the work of many medievalist colleagues, including those noted above, because this is material that needs to be shared often and widely; my focus is specifically on the histories of racist appropriation of medieval images. At the end, I briefly consider some of art history’s formations, and the way whiteness underpins the discipline. This ending is just a beginning, and an issue that we (especially medieval art historians who identify as white) should continue to articulate. Use this, teach with it, talk about it. The Material Collective will continue to address this and other pedagogical issues on the blog and on Facebook over the next few months, because we need innovative pedagogies and self-reflection now more than ever.

******

My Material Collective colleague Maggie M. Williams, in a forthcoming essay, traces the context for the transformation of the so-called Celtic Cross to an image of Irish-American identity and eventually to an unlikely symbol of violent ideology in white supremacist visual discourse. She cites a 2010 post to the white nationalist website Stormfront, which explains: “Because we can’t use the swastika is why we use the Celtic Cross. It symbolizes Christendom and Christianity and also the white, pre-Christian tribes in Europe.” This is chilling — the Celtic Cross stands in for the swastika as a more covert sign, a neo-Nazi “dog whistle.” For white supremacists, medieval Europe is a fantasy of white culture and the source of an imagined, pure heritage. This is a dangerous view of a whites-only Middle Ages, a Middle Ages located primarily in England, Ireland, and Western Europe, with fair-skinned royals and valiant knights defending the borders against threats to that homogeneity. And unfortunately it’s a Middle Ages familiar from fantasy novels, video games, movies and television, as well as from textbooks and syllabi.

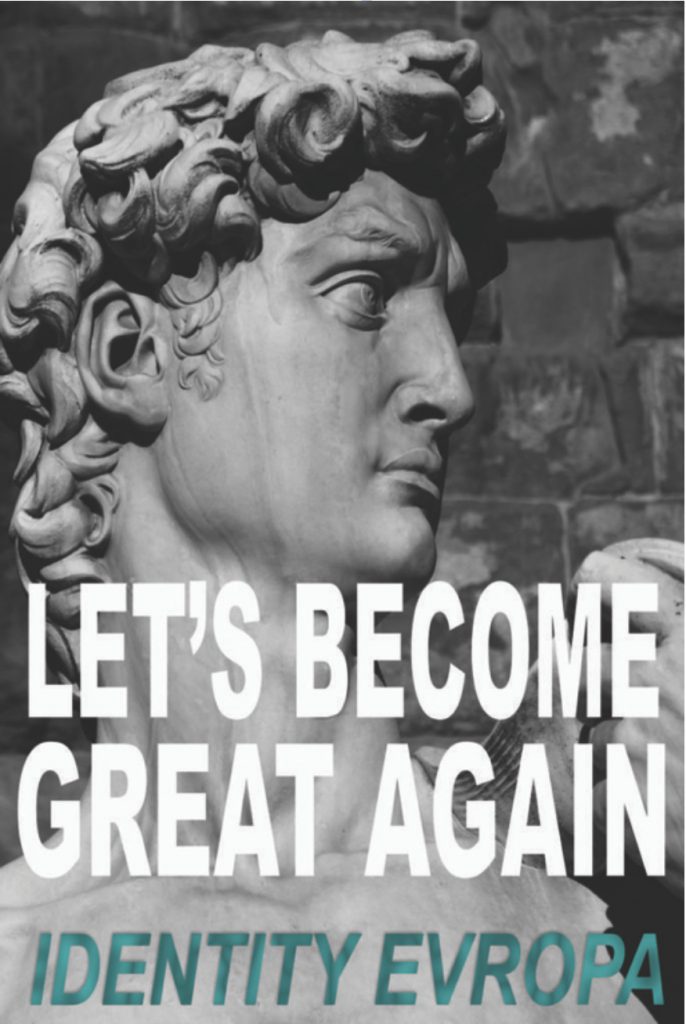

Fig. 1. Identity Evropa propaganda poster

It’s not only “Celtic” imagery that’s marshaled in defense of this whites-only Middle Ages. Identity Europa, a white nationalist, anti-immigrant group with chapters across the US, distributes flyers on high school and college campuses, with imagery of white marble classical and Renaissance sculptures that make their propaganda look like posters for Art History courses [Fig 1]. According to their website, a central point in Identity Evropa’s message is that white people should take pride in their race and resist being “ethnically cleansed.”

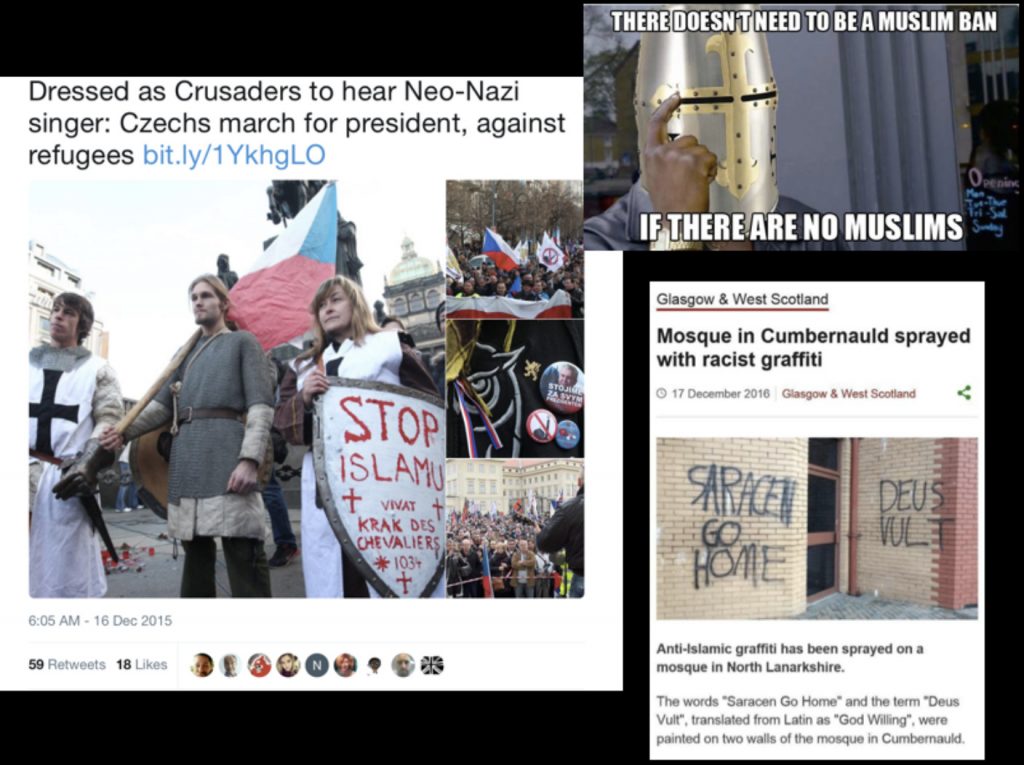

Fig 2. Screenshots of anti-Islamic slogans

Crusader imagery is popular, both in the US and in Europe, as in an image of Czech demonstrators at an anti-refugee rally in 2015 [Fig. 2, left]. In the screenshot, a tuniced “Crusader” holds a shield reading “Stop Islámu” (stop Islamicization) and “Vivat krak des chevaliers,” a reference to the 12th-century Crusader castle in western Syria that has been badly damaged during the civil war. The graffiti on the Scottish mosque, “Deus Volt” or “God Wills It,” [Fig. 2, lower right] is recorded in twelfth-century texts as a battle cry of Christian crusaders in the Holy Land. And the anti-Muslim meme featuring a helmeted Crusader [Fig. 2, upper right] was circulated online beginning in January 2017, following President Trump’s executive order of the first travel ban.

Fig. 3. (L): Harald Damsleth, Waffen-SS Propaganda poster, 1941; (R): Poster for a meeting of the Nasjonal Samling (National Union), far-right Norwegian political party.

Another source for the white nationalist imagination is Viking imagery, which has a long history in Nazi propaganda [Fig 3]. A World War 2 recruitment poster, for example, calls on the Norse legion to join with the armed wing of the SS against the Bolsheviks; another flyer for a political convention in Nazi-occupied Norway aligns modern Nazi soldiers with medieval Vikings and shows a silhouette of the 19th-century St Olaf monument commemorating his death at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030. In 1944, the monument was replaced with the NS (Nasjonal Samling) Monument, which was ‘de-nazified’ in 1945. In contemporary white supremacist use, Viking motifs project a similar sense of white identity and heritage as the appropriations of Celtic art, using Thor’s hammers, ravens, and runes.

Fig 4. National Socialist Movement marchers in Charlottesville, Virginia, August 2017.

Some of the white supremacists marching in Charlottesville last summer carried banners with the Othala rune, which is found in early Scandinavian inscriptions and in 9th century poetry in Anglo-Saxon England [Fig. 4]. In the poetry, Othala expresses the idea of “homeland” or “inheritance,” and white nationalists display this as a symbol of their claims to historical continuity of identity, as well as a threat to the ‘others’ they see as taking the land that is rightly theirs. Versions of the Othala rune have been used by several Nazi and neo-Nazi groups in Germany, South Africa, and the US since the mid-twentieth century, and in 2016, the National Socialist Movement, an American neo-Nazi political party, replaced the swastika on their regalia with the Othala. Like swapping the swastika for the Celtic Cross, this is meant to provide cover to operate in the mainstream.

Of course there were people of color in medieval Europe, and we have lots of visual, archaeological, and textual evidence to refute bad medievalism and claims of pure whiteness, or racial isolationism. The Viking-age Norse and Swedes, for example, had frequent and peaceable relations with Muslim traders, and displayed Islamic coins on their jewelry as signs of wealth, taste, and worldliness. And it doesn’t take a medievalist to know that David, as in (the early 20th-century replica of) Michelangelo’s sculpture reproduced on Identity Evropa posters, was a Middle Eastern Jew. (For more analysis of the sources of Identity Evropa propaganda, read this essay by Ben Davis.)

Calling out the ironic historical inaccuracies of white supremacists’ dangerous, ideological misappropriations of the Middle Ages is not, however, an end goal in itself. These incidents — and so many more, which have been made visible through social media, podcasts, and blogs — have been a call to action for historians of antiquity and the Middle Ages, making clear that we need to reshape our view of the past, in order to reshape the public’s view.

This is imperative not only because it is the medieval history we should be teaching and researching and exhibiting, but because young neo-Nazis and white supremacists may be taking our classes. Nathan Damigo, the founder of Identity Evropa, is a student at a Cal State campus. One of the Charlottesville tiki-torch wielding aggressors was a student at University of Nevada-Reno, taking medieval history courses and, according to his classmates, often making racist comments. If we are – inadvertently or through habit – presenting in classes and textbooks and museum displays a mostly or unproblematically white Middle Ages, a Middle Ages that is Christian-by-default, or a Eurocentric Middle Ages, we must do better. As Asa Mittman recently pointed out in a podcast interview, “we have provided a space where these narratives could thrive, if our work did not directly challenge them.”

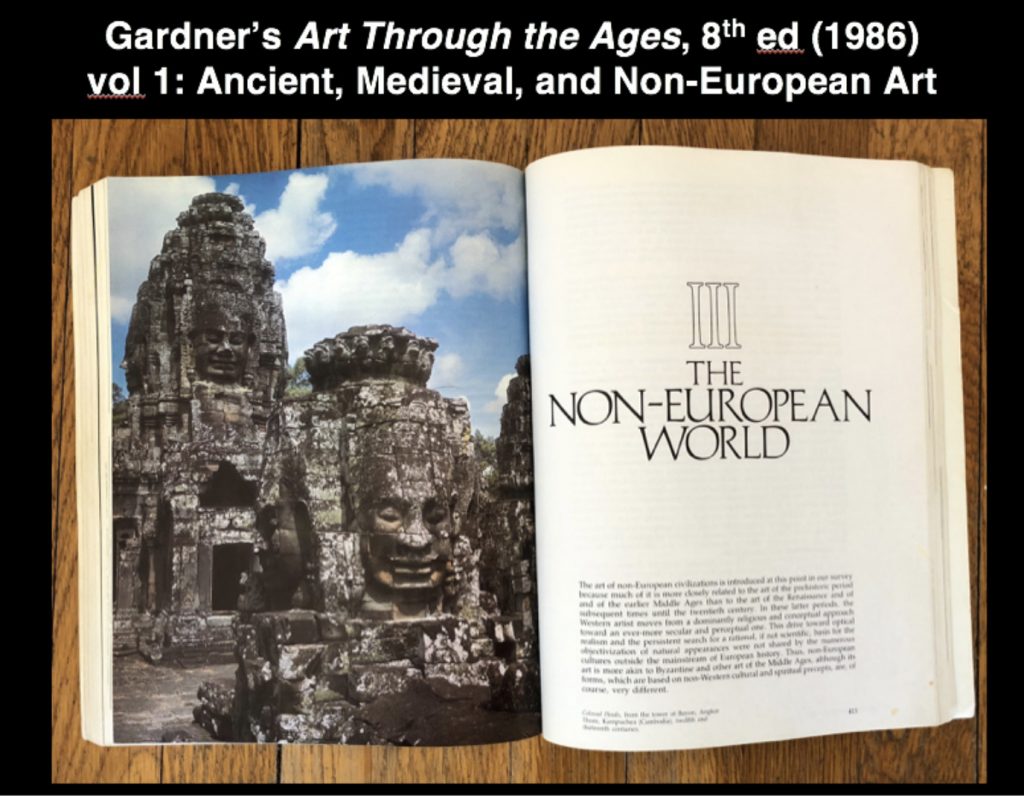

Fig 5. My undergraduate art history survey textbook.

This is a tough challenge to take up, in part because the concept of the Middle Ages itself is premised on the chronological development of a geographically-bounded western Europe. In the art history textbook I used as an undergraduate, the chapters on medieval art covered only England, France, Germany, and Italy, and were followed by “Non-European Art,” a 100-page section on India, China, Japan, Africa, the Americas, and the South Pacific from 3000 BCE to the twentieth century [Fig 5].

There’s much to discuss here, but what I want to stress is the separation of medieval western Europe from the rest of the world — a separation that generations of students internalized, and that is as inaccurate and distorted as it is tenacious in the public imagination. As Marianne O’Doherty writes in the Public Medievalist series Race, Racism and the Middle Ages, “When medieval people viewed their world, they envisaged it as stretching from the ‘land of Darkness’ (as Marco Polo calls it) of northern Asia, to Madagascar and Sumatra in the south, and as far east as Japan.” O’Doherty continues: “Our horizons, when we think about the Middle Ages, need to stretch across these distances and cultures, too.”

Europe was not the center of the world in the medieval period; we (here I mean American and European medievalists, many of whom identify as white) have made it so. Let’s change that. We must shift the focus, and unequivocally counter the fantasy of a white Middle Ages by including histories of race, ethnicity, cultural interaction, and multiple artistic and literary traditions in our courses. (Here’s one place to start: put Geraldine Heng’s new book on your syllabus. In particular, Chapter 4, on the politics of color in the Middle Ages, is an important read for art historians. Heng explores constructions of both whiteness and blackness, and the role of images such as the 13th-century sculpture of St Maurice at Magdeburg Cathedral in medieval views of “epidermal race.”)

From long before Charlottesville, many medieval art historians have turned their focus to sites of cultural exchange, such as medieval Sicily and Spain; to the movement of materials and resources across global trade routes; and to the reuses and multiple, often contradictory, receptions of art works. All of these are strategies that can subvert notions of purity. Such work can disrupt the narratives that center France, England, and Germany, and that further reify borders and identities that were, in the Middle Ages, fluid and often contentious.

In my own research on jewelry and metalwork in early medieval England, Ireland, and Scandinavia, I’ve looked at the circulation and reuse of materials, including gemstones. The garnets in 7th-century Anglo-Saxon metalwork, for example, were mined in India, Sri Lanka, and in the Czech Republic; they were imported through the Frankish kingdom, which maintained trade partnerships with the Byzantine empire, who in turn sourced goods from Silk Road merchants. I was surprised to learn the extent of trade networks and travel routes, especially in relation to my current research on Kentish disc brooches. The white material on a number of examples, usually assumed to be ivory or bone, is in fact shell — specifically the shells of large marine gastropods, such as conch, abalone, and large whelks — species that biologists have shown were too large to have grown in the cool waters around Britain. These were imports from the Red Sea, the Indo-Pacific, and the Mediterranean, passing through the hands of traders to end up as decorative material in the jewelry of elite Anglo-Saxon women — and sometimes whole, as valuable objects themselves: cowrie shells have been found in seventh-century women’s graves, alongside other personal items and heirlooms. Although there are no texts specifically describing attitudes to these oceanic treasures, the Anglo-Saxons did write extensively about the sea, and about sea-travel. The presence of these shells can help us to understand some of the ways that early medieval people saw their world reaching further than their own shores.

My study of jewelry materials isn’t going to make Anglo-Saxon England look less white, but I hope it will, in some small way, reveal it to be less inward-focused. And in any case, reorienting my own inquiries, considering the materiality of medieval objects in relation to global trade, seafaring economies, and the reception of materials, has prompted me to reflect on what it is that I desire when looking at medieval objects, and on how my desire shapes my students’ views of the past.

What, then, should be our individual or collective responsibility when we teach medieval art history? As Roland Betancourt has recently written, “If art historians believe that their work has any meaning or function outside of the academy, then they are implicitly acknowledging that their work has ethical consequences.” This can be, Betancourt suggests, “as simple as constructing interpretations of pasts… for communities which set the foundations for their presents and potential futures.”

When we imagine the past, we have, I believe, an ethical imperative to expand our field of vision, to redress the 19th-century imperialist perspective of homogeneity and rightful dominance, a view that claims ancestral heritage in medieval Europe. Whether or not we are medievalists or art historians or both, we can work toward this. We can, as Betancourt urges, make ethics a methodological imperative.