Tirumular (Drew) Narayanan • University of Wisconsin, Madison

Recommended citation: Tirumular (Drew) Narayanan, “’The Sorcerer Has Many Names, Many Forms’: Finding Identity & ‘Crypto-Visuality’ through Thulsa Doom,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/JJJI2461.

Though I had previously held an interest in medieval fantasy, and specifically Arthuriana, watching Conan the Barbarian (1982) in 2005 at age thirteen was a watershed moment. Directed by John Milius and starring Arnold Schwarzenegger in his breakout role, the film had been a cornerstone of my father’s young adulthood, inspiring him to become an amateur bodybuilder in India. While Conan’s bronzed skin and muscled form spoke to my athletically inclined father, I was immediately drawn to the film’s villain, the evil sorcerer Thulsa Doom (James Earl Jones), whose darker hue, theatrical presence and “snaky Orientalism” resonated with me.[1] He recalled an optical silhouette that characterized familiar black-robed, Eastern-coded wizards, including Jafar from Disney’s Aladdin (1992) and Mola Ram (Amrish Puri) in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). Still, the Conan villain appeared to my young self as more legitimately “medieval” than these other two examples – the former due to its non-European context and the latter because of its temporal one. From his introductory scene, where he is wearing a lofty snake-headed helmet and black armor, Thulsa Doom provided evidence that people like me could exist in the “medieval fantasy world,” which I had narrowly defined through what I understood to be epistemologically true based on my reading Prince Valiant, and other such medievalizing stories characterized by their whiteness. In the weeks that followed, I began pursuing the source material with a growing thirst to learn more about the cinematic counterpart that I had envisioned for myself.

Fig. 1. James Earl Jones as Thulsa Doom (Conan the Barbarian, 1982).

This reflective essay focuses on my earliest memory of an effort to conduct research, as I trace the multi-textual history of Thulsa Doom, who, strictly speaking, never appeared in the “original” Conan pulp stories written by Robert E. Howard in the 1930s. In doing so, I consider my nascent encounters with themes that would later inform my scholarship: canonical authority, the slippage between text and image, and perhaps most importantly the multivarious yet ubiquitous shape of the racialized Other that echoed my own lived experience. Locating a Latin Christian version of “Thulsa Doom” in the “Master of the Assassins,” I conclude by demonstrating how tracking the various iterations and inspirations of the sorcerer actually helped me articulate the visual racializing technologies of the medieval past. Unlike the film’s character, the expected markers of racialization such as skin color, costume, and accoutrement are inconsistent and unstable categories for making these determinations in medieval manuscript illumination. Instead, it relies on what I term the “crypto-visual” qualities of medieval “race-thinking.”[2]

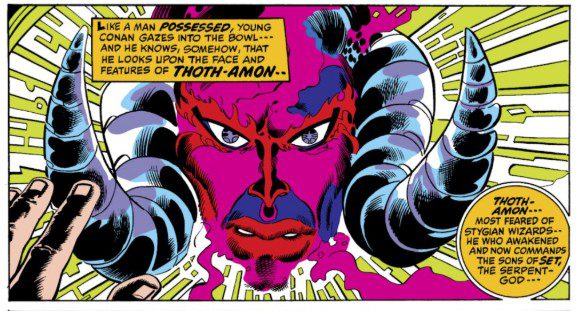

The cinematic version of Thulsa Doom is, at his core, a snake sorcerer and in one famous scene he transfigures himself into a giant serpent. Howard’s original Conan stories contained a whole series of evil Eastern wizards engaged in serpent wielding, weaponizing, worshiping or some combination thereof. Indeed, the blue-eyed barbarian could not seem to take a step without encounters with the ophidian enemy. Howard’s suicide in 1936 brought an end to the Conan stories until the 1950s when L. Sprague de Camp, his wife Catherine Crook de Camp, and Lin Carter repopularized and heavily edited the extant corpus, finishing fragments Howard had left behind and sometimes modifying entire stories.[3] During this process, these writer-editors positioned Thoth-Amon (the brown-skinned High Priest of the Serpent-God Set) as the barbarian’s main antagonist.[4] This character had only appeared in one of Howard’s original short stories, though he was mentioned in several other tales.[5] Marvel Comics’ run of Conan the Barbarian (1970-1993) and The Savage Sword of Conan (1974-1995) cemented the priest’s role as a major villain.[6] Conversely, the character Thulsa Doom originally appears as an enemy to another of Howard’s heroes, Kull of Atlantis, an early iteration of the heroic barbarian, who hailed from an even more ancient past. The character differs greatly from that imagined in the Milius film. In the Kull story “Declardes’ Cat,” Doom is described as a skull-faced sorcerer who disguises his appearance with a veil.[7] Moreover, the story featuring Doom only came to light in the 1960s as a result of de Camp’s reworkings, as Howard had been unsuccessful in publishing the story in his lifetime. Marvel also began running Kull the Destroyer and Kull the Conqueror series in the 1970s, both which featured Doom as the Atlantean’s main villain.

Fig. 2. Reprint of Thoth Amon’s first appearance in Conan the Barbarian #7 by Roy Thomas (Author) & Barry Windsor-Smith (Illustrator) (Marvel Comics, 1971), In Conan the Barbarian Epic Collection: The Original Marvel Years-The Coming of Conan (Marvel Comics, 2020).

Armed with only some of the literary history of these characters I have outlined above, I began to form what I now understand to be a research question. Why did Milius make the decision to name this character “Thulsa Doom,” especially when characters such as Thoth-Amon existed in the “original” stories?[8] As I then believed, “originals” were the best, the most “correct,” the most “authoritative,” and the most “true.” The original had a special kind of power which only the initiated, the well-read, could access. In my mind, intervening iterations between the original text and the film only functioned as corruptions, and not part of a continuum of reimaginings.[9]

This thinking connected to my personal bond to the film, as the iconographic mis-match between text and image also began to trouble me. If the character Thulsa Doom, as Howard had originally envisioned, appeared as a skinless form, how legitimate, how authoritative, was my own identification with the character portrayed by James Earl Jones? Furthermore, unlike his textual counterparts, Milius’ Thulsa Doom is not persistently coded as Orientalized in his costume presentation. The character at times wears silken robes, surrounded by snakes and leopards but at other times wears fur-draped armor and a horned helm, signs that recall something more of a European “Black Knight” than an Eastern priest. Such visual inconsistencies bothered me further upon watching the sequel, which featured an evil wizard named Thoth-Amon, played by the blue-eyed and fair skinned English actor Pat Roach, wearing brilliant scarlet and gilded fingernail guards reminiscent of imperial Ming costume (zhijiatao).[10] This left me wondering: was the first, or “original,” film a legitimate representative of the source material and myself?

I would find my answer some years later in the form of an early draft of a script for the Conan film, written by Oliver Stone in 1978. The text states that Thulsa Doom was born from an egg laid by Set many eons ago. Most importantly, the script informs us that “the sorcerer has many names and many forms,” appearing differently in various generations.[11] In reading the script, I found a partial answer to my original superficial question regarding the naming of the character. Given that Stone originally conceived of this character as an immortal, it followed that he selected a name for the villain outside of Conan’s canonical temporality and from the older Atlantean Age. When John Milius took over the directing of the film, he may have simply maintained this decision. More importantly, however, the line quoted above left an impression in my thinking about the character’s recyclability. The Thulsa Doom of Stone’s draft is yet another variation, a creature possessing multiple avatars throughout the screenplay ranging from nearly bald cadaver to scaled gargoyle to red-haired demon.[12]

Curiously enough, the metatextual process of film making replicates Stone’s description of Thulsa Doom’s multi-various shape, ultimately yielding the James Earl Jones version. In every iteration from Howard’s original works, through the various pastiches, to comics, to scripts, to the cinematic adaptations, the snake sorcerer is reincarnated, shedding his skin if you will, into a new version that is, as Homi K. Bhabha might say, “almost the same but not quite.”[13] I am here playing with Bhabha’s words; my use of the quote does not accurately communicate his intention for his term “mimicry,” I nonetheless find it useful for explaining my understanding of the racializing mechanism at play here. Whereas Bhabha’s definition refers to the colonizer’s desire for a more “civilized” subject, the snake sorcerer’s multiple versions embody the recycled accusations that the colonial gaze repeats against the colonized. In other words, the caricature constantly mimics the previous iteration of itself, thrust upon it by the mind of colonial power. If Doom returns in new guises and monikers in each generation, then the character is not limited to Howard’s original creation. I came to see Doom, instead, as part of a wider cohort of undesirable “anti-Western” thaumaturges, snake-like not only in their associations but in their deceitful threats to hegemonic power, with each iteration building upon the last.

In many ways, what I describe here as a racialized ecdysis – a shedding of the skin, a rebirth in a new form – parallels well the concept of racial “rebooting” described by Noémie Ndiaye. She draws an analogy to the Matrix films, where the oppressive system must periodically reset, so too do racializing narratives change to the politics of its time.[14] Similarly, beyond the confines of the “legitimately” medieval, the aforementioned representatives from Agrabah (Jafar) and Pankot Palace (Mola Ram) descended from the same genealogy as Doom, their new shining scales adorning a familiar model, and all of them cinematic visualizations with which I was triangulating my own social position. The recognition that this shape-shifting yields a sort of shape-fixity assuaged my own anxiety around the canonical authority of my identification with Doom. In whatever guise he appeared, the snake sorcerer’s slippage parallelled my own experience of Otherness that drew me to him in the first place. No matter the variety of cultural accusations or colorful insults, each time a new skin foisted upon me, they always rendered my body unfavored. No matter how hard I tried to change my own shape, to reach out for Whiteness, I always came up just short. Like Thulsa, Tirumular could take any number of appearances but they all remained proscribed, unwanted, and outside. Far from simply somatic parallels or the vague trappings of the Global South, the snake sorcerer archetype and I shared a racializing experience, one which renewed itself in multiple yet persistently familiar forms.

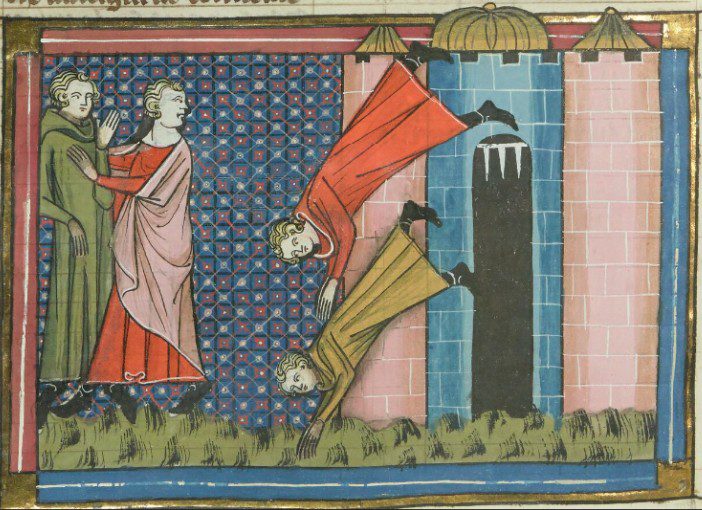

Discerning this plasticity not only clarified how I saw myself but also developed my scholarly understanding of the process of racialization. The multiple shapes of the snake sorcerer did not simply spring forth in twentieth-century American pulp fiction but had a history that connected backwards into the distant European past. Milius’ model for his Thulsa Doom, as well as that of some of Howard’s wizard-villains, participated in a long durée which we can trace back to the Latin Christian imagination of the Master of the Assassins, or Sheik al-Jebal, the historical leader of the heavily mythologized Nizari Ismaili state of Alamut founded in the eleventh century.[15] In an interview James Earl Jones gave to David Anthony Kraft for Marvel Comics in 1982, the actor states “One of the things John [Milius] suggested I do was read all I could about the Cult of Assassins.”[16] According to a French continuation of the crusade chronicle of William of Tyre, the Sheik once commanded his followers to throw themselves from a tower to demonstrate their devotion to him before the eyes of Count Henry of Champagne, who was visiting an Assassin castle.[17] An illumination from the manuscript BnF fr. 22495 depicts a fourteenth-century reimagination of this event. On the left-hand side, the Master of the Assassins, dressed in serpentine green, speaks to his followers with his left hand raised, as the red-garbed Henry clutches to him in terror. From gilded and domed battlements, two acolytes in yellow and red have flung themselves down to the grass, the black, toothy mouth of the portcullis yawning behind them.

Fig. 3. The Master of the Assassins commands his followers to commit suicide. Continuation of William of Tyre, Historia rerum in partibus transmarinis gestarum. France, Paris, 14th century. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Français 22495 f.249v.

Milius’ film recreates this scene, replacing the Master and the Latin Christian prince with Doom and Conan respectively, as the wizard orders a young woman to commit suicide, analogously demonstrating his superior power of flesh over steel. Unlike his modern analogue’s incarnation portrayed by James Earl Jones, whose racialization is clearly coded epidermally and sartorially (at least in this particular scene), here the Sheik appears nearly indistinguishable from his Latin Christian counterpart. Previous scholarship, when confronted with similar European depictions of Islamic leaders, argues that such image types either attempt to communicate parity with their opponents or at times suggest that medieval Europeans did not possess a concept of race.[18] Yet my observations of Thulsa Doom led me to different conclusions. If the snake sorcerer always remained coded as “non-Western” in all his versions, despite his color or costume (brown body, fur-cloaked, red hair, silken-robed, or skinless), then evidently such indicators did not always function as the axle on which the racializing wheel turned. Literary scholars such as Dorothy Kim and Sierra Lomuto are, to a certain extent, correct when they critique or deemphasize the analysis of race as a “visual” phenomena.[19] As my primary sources are still visual (afterall, I study visual art), I now approach racialization with what I term a crypto-visual lens that changes the criteria by which we interpret medieval race-making.

By “crypto-visuality,” I mean that the expected markers of racialization such as skin color, costume, physiognomy, and accoutrement, while important indicators, are inconsistent and unstable categories by which to make such determinations in premodern contexts. Instead, less-expected categories such as text-image interaction, semiotics, topography, architecture, and materiality can serve as more powerful indexes. Crypto-visuality captures the racializing experience, it reveals the mechanism of race-making beyond a taxonomy of Otherness. In the case of Figure 3, we find evidence of this process not through color or costume but through the visual narrative created by the golden dome that alludes to Islamic architectural features, as found in the Dome of the Rock or that of the Fatimid Great Iwan once in Cairo.[20] Of course, the dome does not do the racializing work as Orientalism serves as a poor marker for racialization. Rather, the architecture functions as an indicator of the religious “seat” or reason for which the acolytes commit suicide. In other words, the illumination visually allegorizes Islam as the structural basis from which its followers engage in actions antithetical to Latin Christian morality. This tableau also trades in polemics by referencing their ultimate destination. The black maw of the aperture, with the portcullis shining like teeth, opens behind the acolytes, a simplified version of the hellmouth which so often appears to consume Muslims elsewhere in contemporaneous medieval art.[21] Thus the scene positions the Sheik as a false prophet who, through the dangerous power of speech, convinces his followers to undertake their own destruction. Racialized religion here is not constructed through an isolated sign but through dynamic action, a visual experience, which encapsulates both purported behavior and punishment for those outside of normative Christian society.[22]

Thulsa Doom and his medieval predecessor, though visually rendered in different details, experience parallel optical positionings in their respective imagined worlds. The snake sorcerer’s various sheddings helped me see the multiple forms that racialization could take and so I applied this lens to my personal and professional life. The discourse surrounding medievalism can often feel one directional, as if the modern reinterpretations are valuable because of their premodern progenitors. But medievalism functions not only as a reflection of the past in the present – it can work backwards as well, as a boulevard from the present to better interpret the past. In this essay, I have sought to share how my experience of medievalism gave me an opportunity to find an analogue for myself in a time period I loved, but felt visually excluded from. Further investigation into Thulsa Doom and my own fascination with him helped me better understand my own social condition as participating in a legacy that meaningfully connected me to that “medieval” history, a history that continues to bleed into the praxis of studying the medieval. If nothing else, Thulsa Doom’s many forms have taught me the appropriate answer for when I am asked that inappropriate question accompanied by impish grins born from conference libations taken too early. In those moments, I know what shape to take as a new set of scales grows down my spine. “Tramular, Tramular – is it Indian? What does it mean?” I smile and respond, “snake sorcerer.”

References

| ↑1 | I have previously discussed my “disidentification” (to use José Esteban Muñoz’s term) with the sorcerer in part due to his association with Indian-coded snake iconography. See: Tirumular (Drew) Narayanan, “‘Why is he Indian?’: Missed Opportunities for Discussing Race in David Lowery’s The Green Knight (2021),” Arthuriana 33 no. 3 (2023): 47-49. See also: José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, vol. 2 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), 10-15. See also: Rahul Bhaumik, “Indian Snakes and Snaky India: British Orientalist Construction of a Snake-Ridden Landscape during the Nineteenth Century,” Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities 9 (2016): 233-242. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Here I am using Cord Whitaker’s deployment of “race-thinking.” See: Cord Whitaker, Black Metaphors: How Modern Racism Emerged from Medieval Race-Thinking, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), 14. |

| ↑3 | For a good historiography of de Camp’s and Carter’s contributions to the Conan Mythos as well as the developments made in comics discussed later in this section see: Paolo Bertetti, “Conan the Barbarian: Transmedia Adventures of a Pulp Hero,” in Transmedia Archaeology Storytelling in the Borderlines of Science Fiction, Comics and Pulp Magazines ed. Carlos A. Scolari , Paolo Bertetti & Matthew Freeman, (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014): 24-30. |

| ↑4 | Sprague de Camp openly admits his insertion of Thoth-Amon into Howard’s existing in at least one essay see: L. Sprague de Camp “The Trail of Tranicos,” in Conan: The Treasure of Tranicos, (New York Ace Books, 1980), 174-175. |

| ↑5 | For Thoth-Amon’s appearances in Howard’s Conan stories see “The Phoenix on the Sword,” “The God in the Bowl,” & “The Hour of the Dragon,” in Robert E. Howard, The Complete Chronicles of Conan (London: Gollancz, 2006), 23-43, 733-750, 575-732, respectively. |

| ↑6 | Roy Thomas, Barbarian Life: A Literary Biography of Conan the Barbarian, Volume Two, (Pulp Hero Press, 2018), 91. |

| ↑7 | Robert E. Howard, “Declardes’ Cat,” in King Kull ed. Glenn Lord (London: Sphere Books Limited, 1976), 85-86. Story originally published in 1967 by Lancer Books. |

| ↑8 | I am evidently not alone in my posing of this question about the slippage between Thulsa Doom and Thoth-Amon. For one discussion see: as by internet fans. For one discussion see: “Thoth-Amon,” The Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe, Revised 11/26/2023, http://www.marvunapp.com/Appendix/thotha.htm. |

| ↑9 | This notion of a continuum of reimaginings is in dialogue with Hillel Schwartz’s discussion of “duplication.” See Hillel Schwartz, The culture of the copy: Striking likenesses, unreasonable facsimiles (Princeton University Press, 1996), 175. |

| ↑10 | While these accouterments were used by historical Chinese elites, their transmission into the West resulted in their transformation into an Orientalized trope. Not only did such objects become popular curios, they also informed ballet pointing gestures to communicate a character’s “Chinese” identity. See: Anna Mouat and Melissa Mouat, “European Perceptions of Chinese Culture as Represented on the Eighteenth-Century Ballet Stage,” Music in Art 38, no. 1-2 (2013): 53-59. See also: Michela Fontana, Matteo Ricci: Jesuit in the Ming Court (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2011), 50. |

| ↑11 | Oliver Stone, “Conan: Based on the Stories of Robert E. Howard with Later Additions by L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter,” Unpublished screenplay, August 1st, 1978, typescript, 39. https://web.archive.org/web/20190801083838/http://apolitical.info/teleleli/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/ConanByOliverStone.pdf. |

| ↑12 | Stone, “Conan: Based on the Stories of,” 68 133, 134. https://web.archive.org/web/20190801083838/http://apolitical.info/teleleli/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/ConanByOliverStone.pdf. It appears that Stone’s multi-form Thulsa Doom also drew on Howard’s character Thoth-Amon as the former utters a modified version of the latter’s enchantment which begins with “Blind your eyes, mystic serpent.” See: Stone, “Conan: Based on the Stories of,” 114. See also: Howard, Complete Chronicles of Conan, 32. |

| ↑13 | See Homi K. Bhabha, Location of Culture, (Oxon: Routledge, 1994), 122. Edward Said makes a similar observation of the recycled nature of the Orientalized body. See also: Edward W. Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon Books, 1978), xx. |

| ↑14 | Noémie Ndiaye, Scripts of Blackness: Early Modern Performance Culture and the Making of Race (Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2022), 8. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2gz3zr2. |

| ↑15 | Juliette Wood, “The Old Man of the Mountain in Medieval Folklore,” Folklore 99, no. 1 (1988): 78-87. Farhad Daftary, “The ‘Order of the Assassins:’ J. von Hammer and the orientalist misrepresentations of the Nizari Ismailis,” Iranian Studies 39, no. 1 (2006): 71-81. Geraldine Heng, “Sex, Lies, and Paradise: The Assassins, Prester John, and the Fabulation of Civilizational Identities,” differences 23, no. 1 (2012): 1-31. One of Howard’s original evil wizards, the Master of Yimsha, resides in a mountain, sending forth his acolytes to commit political assassinations. See: Howard, The Complete Chronicles of Conan, 289-355. |

| ↑16 | David Anthony Kraft, “From Hyboria to Hollywood,” in Marvel Comics Super Special 1 no. 21 (New York: Marvel Comics Group, 1982). |

| ↑17 | Wolfgang Fleischhauer excellently lays out the various recountings of this story in different medieval texts See: Wolfgang Fleischhauer, “The “Ackermann aus Böhmen” and the Old Man of the Mountain,” Monatshefte (1953): 195. |

| ↑18 | For parity, see: Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, demons, & Jews: making monsters in medieval art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 126. For evidence of a lack of a racial concept see: Robert Bartlett, “Illustrating Ethnicity in the Middle Ages,” in The Origins of Racism in the West ed. Miriam Eliav-Feldon, Benjamin H. Isaac, Joseph Ziegler (Cambridge University Press, 2009), 132-133, 148. |

| ↑19 | See: Dorothy Kim, “Introduction to literature compass special cluster: Critical race and the Middle Ages,” Literature Compass 16 (2019): 4-5. Dorothy Kim, “The politics of the medieval preracial” Literature Compass 18, no. 10 (2021): 7. See also: Sierra Lomuto, “The Mongol Princess of Tars: Global Relations and Racial Formation in The King of Tars (c. 1330),” Exemplaria, 31 no. 3. (2019): 172-173. |

| ↑20 | While the current “golden” dome of the Dome of the Rock is modern, some textual evidence exists for the presence of a gilded dome in medieval versions of the building. For one example of this discussion see: Nasser Rabbat, “The Dome of the Rock Revisited: Some remarks on al-Wasiti’s accounts,” Muqarnas 10 (1993): 68. For the no longer extant gold dome of the Fatimid Iwan see: Nasser Rabbat, “Mamluk Throne Halls: ‘Qubba’ or ‘Iwān?’” Ars orientalis (1993): 208. https://doi.org/10.2307/1523173. |

| ↑21 | Many thanks to both Levi Sherman and Tiffany VanWinkoop for asking me why the gate here looks like a mouth which led to my thinking and explanation of this form as a hellmouth. For a discussion of hellmouths see: Sherry C. M. Lindquist & Asa Simon Mittman, Medieval Monsters: Terrors, Aliens, Wonders (New York: The Morgan Library & Museum, 2018), 67, 93. See also: Gary D. Schimdt, The Iconography of the Mouth of Hell: Eighth-Century Britain to the Fifteenth Century, (Selinsgrove, Pa., Susquehanna University Press, 1995). For example of punishment of the Prophet Muhammad in a hell mouth see: Heather Coffey, “Encountering the Body of Muhammad: Intersections between Mi’raj narratives, the Shaqq al Sadr, and the Divina Commedia in the Age before Print (1300-1500),” in Constructing the Image of Muhammad in Europe, ed. Avinoam Shalem (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013), 57-59. |

| ↑22 | Here my use of racialized religion is indebted to Geraldine Heng’s articulation of “religious race.” See: Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 20, 27-31, 124, 149. The concept of the dynamic action as opposed to isolated sign is one parallel to, though certainly informed by Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s discussion of race when he says “race cannot be reduced to any of its multiple signs. […] Although inextricably corporeal, race is also performative, a phenomenon of the body in motion […] race is embodied performance.” See: Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Race,” in A Handbook of Middle English Studies, ed. Marion Turner, (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 111-112. |