Brinna Michael • Cornell University Library

Kelin Michael • Hammer Museum

Liam Michael • Full Scale, LLC

Recommended citation: Brinna Michael, Kelin Michael, and Liam Michael, “The Siblings’ Tale: Medievalism, Media, and Memories,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/AJDV4103.

The following is a conversation held between three siblings, the original recording of which lasted nearly three hours. To that end, we present, for your enjoyment, an edited version, which will lead you through a wide range of topics, including: trebuchet construction, classic literary structures, fantasy vs. reality, anti-Eurocentrism in historical study, John Calvin, video games, and what the average medieval European might think of capitalism. Without further ado, we invite you to enjoy “The Siblings’ Tale.”

Introduction

Kelin: Alright well we are here today to do this little chat about medievalism and about how all things medieval have influenced our lives. I’m the resident medievalist of this trio, Dr. Kelin Michael. I have a PhD in medieval art history. And many people will ask, what do you do with that? I talk about medievalism and how medieval stuff is really relevant to us today. And these are my siblings!

Brinna: I’m Brinna Michael. I don’t have a cool title, but I do think a Master’s degree should get you a cool title.

Kelin: You have an MLIS!

Brinna: I do. I have an MSLIS. I’m a librarian.

Liam: And I’m Liam Michael. I also do not have a fancy title, and I am also of the opinion that an undergraduate degree should get you a fancy title.

Kelin: You have letters!

Liam: Yeah, I have a BA. I studied political science, communication studies, and GIS or geographic information science. So, nothing that’s too obviously connected to medieval history. The closest is poli-sci talking about the transfer from feudalism to capitalism. Medievalism has probably impacted me the least, but I think we’ll be able to connect this to my current job. I work in industrial printing.

Kelin: I’m sure we’ll find a way. Medievalism hasn’t influenced your career path as much as mine or Brinna’s, but today we’re going to talk about how medievalism runs throughout our interests in childhood and how we’re still interested in things that are influenced by the medieval. Brinna and I have been looking for a way to collaborate professionally for a while, because a lot of our interests outside of work overlap, but also because during the pandemic we were living together and working together in very close proximity.

Brinna: So close.

Kelin: So close, and it brought us a lot closer together, both on a personal level, but also on a professional level. We’d look in on each other’s projects and advise with our areas of expertise. We found that they complemented each other really well. So, when we saw the prompt for this special edition of Different Visions, we really wanted to work together on it and we wanted to include Liam, because we have shared a lot of similar interests throughout our lives.

Pretend and Trebuchets

Kelin: We often played like we were in a castle or working in the kitchens. Or we were orphans trying to escape the evil king. We would go on adventures and use sticks as swords. Why don’t you guys talk a little bit about that?

Brinna: I immediately thought of our dress up box.

Kelin: Yes!

Brinna: Our parents wouldn’t buy us dress up clothes. They’d say, “We went to the store and we bought you some fabric.” What was so great was you could make whatever you wanted out of these pieces of fabric: lavish ball gowns, mysterious cloaks… and we’d run around with “swords.” Every stick and broom were swords and every short stick was a knife. As children we clearly had a deep understanding of the social dynamic–

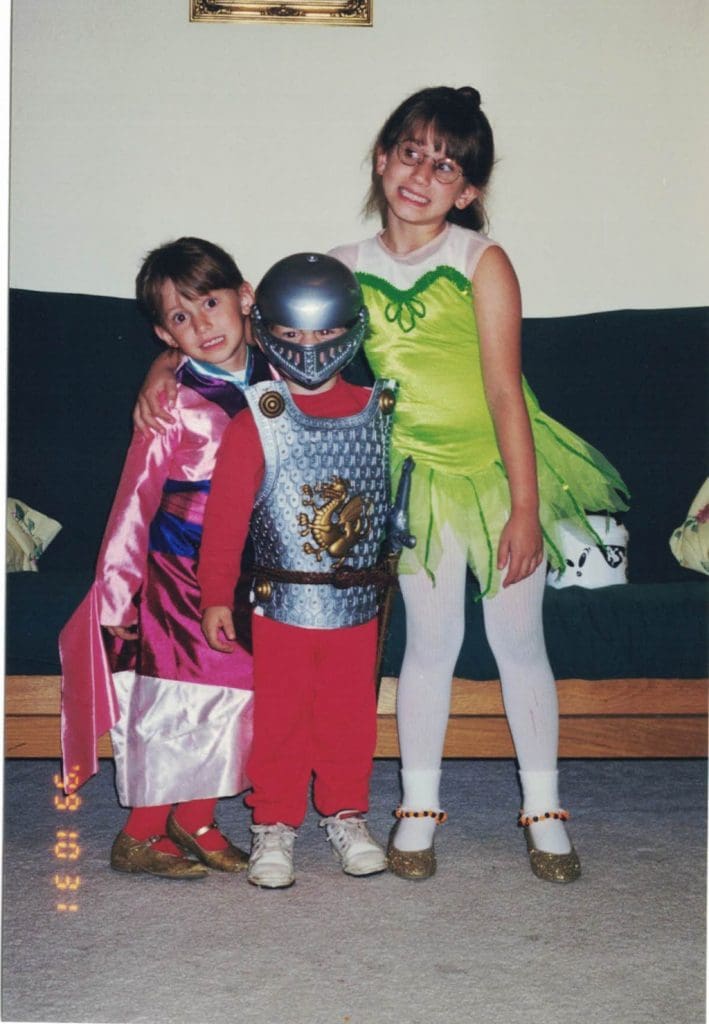

Fig. 1. Brinna and Kelin Michael playing dress up. 1996.

Kelin: …of the medieval period. What do you remember about pretending, Liam?

Liam: The most vivid memory I have is of the old cherry tree out front of our house. Eventually our dad decided it was time for that tree to go, and chopped it down. But it had a lot of really nice branches that were perfectly straight, very bendable and flexible. We built bows out of a few of those limbs using twine and dowel rods…Our mom was an archer when she was back in college, and still had her old bow and fletchings. We were able to glue fletchings to the dowel rods to make pretty good arrows. Honestly, I remember those actually being pretty accurate.

Brinna: I remember when Mom and Dad realized just how good the bows were. And they were like, “Ohh…”

Kelin: “This is dangerous.”

Brinna: “Maybe we should say you can only use those in this part of the yard and–”

Kelin: “Don’t point it at anybody.”

Liam: They set up some rules. Also, when I was in middle school, there was a Trebuchet Club and I signed up.[1] There were probably six different adults, some parents and one teacher, who coordinated the whole program. The adults got together on weekends and built a full-scale model trebuchet that could throw 90-lbs concrete balls and then all the students got to build their own mini trebuchets. It was one of the earliest experiences I had with hands-on learning, using mechanics and physics in a real-world setting. That’s one way I’d link medievalism to my current career in printing. Running a machine, understanding the mechanics of that particular system and how they all come together so that you can troubleshoot when things go wrong.

Fairy Tales and the Hero’s Journey

Brinna: We inherit certain mythologies and folklores. Kids listen to their parents tell them fairy tales, and they’re always set in this distant past. So even before you can read, before you’re really forming memories, it influences you. You feel drawn to these exciting stories, adventures with heroes and villains…they’re familiar and exciting at the same time.

Kelin: Yeah, the idea of “Once Upon a Time.” Like, when is the time? It’s obviously a long time ago.

Brinna: Their clothes don’t look like ours. Or there are mystical creatures. It’s not like our world but there are still familiar things, it feels far away and close.

Liam: There’s the gendered aspect of it, too. What draws a lot of young boys to medieval history is the image of the knight, being heroic and having armor and weapons. At a young age, I was interested in military history and the mechanics of weapons. I can’t tell you how many hours of documentaries I’ve watched on the development of different guns.

Stories about the medieval era are also some of the earliest encounters that kids in the Western world have with the concept of the Hero’s Journey.[2] Most often, the protagonist comes from a lower station and that’s inspiring to kids. Even if they don’t have power or resources, they can still have adventures and make something of themselves. It’s also an inescapable literary trope–this is where I put on my poli-sci nerd hat. One of my favorite scholars is Dr. Richard Wolff.[3] He’s one of the only remaining Marxist scholars in America, and he argues that not much changed when feudalism transitioned to capitalism. It was simply–

Kelin: A rebranding.

Liam: Yes. Instead of having a lord and a surf relationship, there’s an employer and employee relationship. Since we haven’t gotten an actual evolution of social and economic structure, where an individual has full freedom to do what they want, people crave stories structured as a Hero’s Journey.

Kelin: Playing pretend as a kid helps you work through a lot of things. It’s a way to distance yourself from your real life. And there’s this sense of magic caught up with the understanding of the medieval period that allows you to conflate fantasy and history. Growing up, we were very middle class, maybe even lower middle class. We were never wanting for anything that was a necessity, but a lot of things that other kids our age were experiencing, like vacations and video games, we didn’t have direct access to. For us, pretending was a way to exercise our creativity.

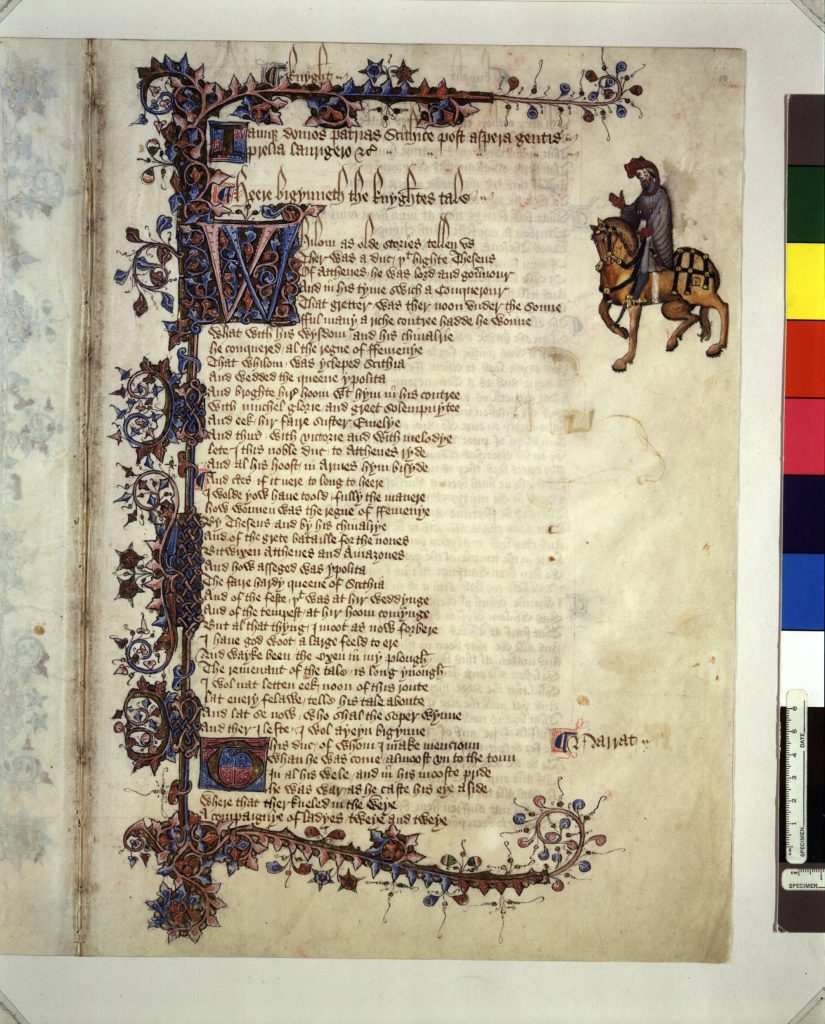

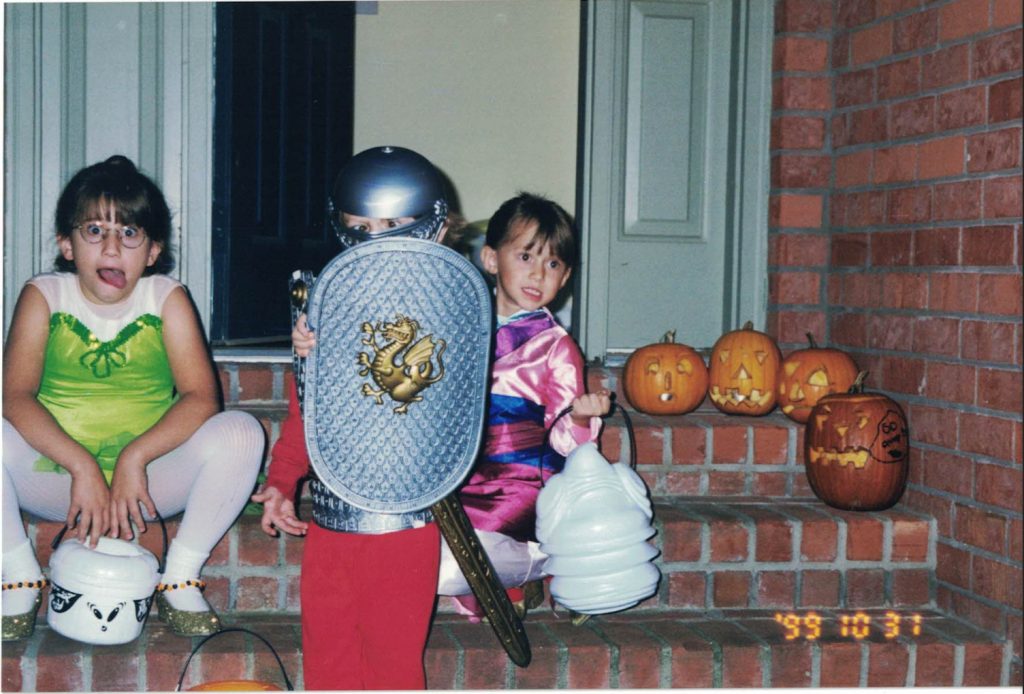

Do you remember the Halloween where I was Tinkerbell? You were Mulan, Brinna, and you were a knight, Liam? That trio of costumes perfectly encompasses the historical and magical aspects that people equate with the medieval period.

Fig. 2. Brinna, Liam and Kelin Michael dressed up as Mulan, a knight, and Tinkerbell. Halloween 1999.

But also, there is a non-Western section of medieval history that often falls through the cracks with somebody like Mulan, who’s a real historical figure but doesn’t often get recognized in Western culture.[4]

Medieval is a Real Thing™

Kelin: Another thing to look back on is what the first popular media we remember as being inspired by the medieval and what stuck with us.

Brinna: Specifically, what’s the first thing that we recognized as–

Kelin: Being medieval.

Liam: This one is hard for me. A Knight’s Tale[5] for sure, and Redwall on PBS.[6] I don’t know exactly what about Redwall, but it was pretty clear with the castles and soldiers and monks and the abbey. Then, Timeline[7]… As a kid I really liked Timeline because I love the idea of someone from modern times going back in time with the knowledge that they have. How would those interactions work?

Kelin: I love that you mentioned that Redwall was clearly medieval because there were monks. A lot of times, when people make media that’s inspired by the medieval period, things fall out. Part of what I love about Redwall is that it gives a sense of how a medieval community functioned. There’s a castle and an abbey where everybody is living together.[8] There’s nobility. There are monks. Everybody’s in the same general vicinity.

As for Timeline, it shows that even if you know what happened historically, living in that period is something completely different. People tend to look at the medieval period as the “Dark Ages,” where not a lot was happening. That’s a huge misconception, and it’s slowly being overturned, but Timeline does a really great job of showing that you can only know so much about the actual history of a time and place, especially with the lack of records and what’s kind of gotten lost over the years. The characters quickly find that they don’t know how to effectively navigate the particular period they travel to just by reading history books.

Brinna: I read the book years after seeing the movie and they didn’t include this part where one of the characters, a historian, knows how to sword fight. And when they go back in time, he gets involved in a tournament. And there is a misunderstanding of how strong these men had to be to wear plate armor and wield massive weapons.[9] This is like a guy who goes to the gym five out of seven days of the week thinking he could take on a Navy SEAL.

Kelin: I think that that’s such a great transition to talking about A Knight’s Tale. There’s this great scene where William, who is posing as a knight, has to get new armor.

Fig. 3. Liam Michael “jousts” at a Renaissance Faire in Michigan. July 2001.

This woman blacksmith, which I love, has found a “new way to temper the steel” so that it’s much lighter. When William puts it on, they laugh because they’re like, “Oh, my God, this isn’t gonna protect you against anything.” And she’s like, “Can you at least have the courage to test it?” And he’s like, “Fine…” So, she shoves this huge piece of wood at him and he’s like, “Wow, I didn’t feel anything!” So, he walks out into this tournament and the other knights are laughing about his little baby armor. But, then, he steps up and mounts his horse without help. They all shut up immediately because they’re wearing armor that’s so heavy they can’t mount a horse. I think that’s a great illustration of what you were talking about…understanding how strong you needed to be to wield all this material.

Liam: Learning about archers is insane.[10] My first exposure to this was watching the Military History Channel shows about medieval warfare, specifically one about archers. If you wanted to become an archer, you didn’t sign up to be an archer for the king. You would start at a young age, and from 10 to about 15, all you do is build your draw strength. By 15 years old, you were expected to be able to pull a full longbow, which had a draw weight of 100-185 lbs.[11] Today, there’s archers who are in their late 20s, 6’ or more, 260 to 300 lbs solid muscle, huge back muscles and struggle to pull more than 80 lbs.[12]

Kelin: There are also some great YouTube videos where professionals watch movie clips and rate their accuracy. They have a few with an archery guy.[13] I love that he shows people that archery is not just picking up a bow and magically being an amazing shot. If you want to be accurate and shoot from a distance greater than 4 meters, you really need to practice the skill, have a specific type of bow, and learn how you shoot. It’s technique- and strength-based.

Brinna: This reminds me of the Ranger’s Apprentice books.[14] They show that you have to put in work to accomplish something like being an archer or a knight, but also that your natural stature might make you better at one or the other.

Liam: Language is another thing that evolves. I’ve seen linguists who study the history of English discuss that if you went back to the 1300s, they’re speaking English, but it’s Middle English. So, you wouldn’t understand 80-90% of what they’re saying. That would have been cool in Timeline, if they all spoke Middle English when they went back.

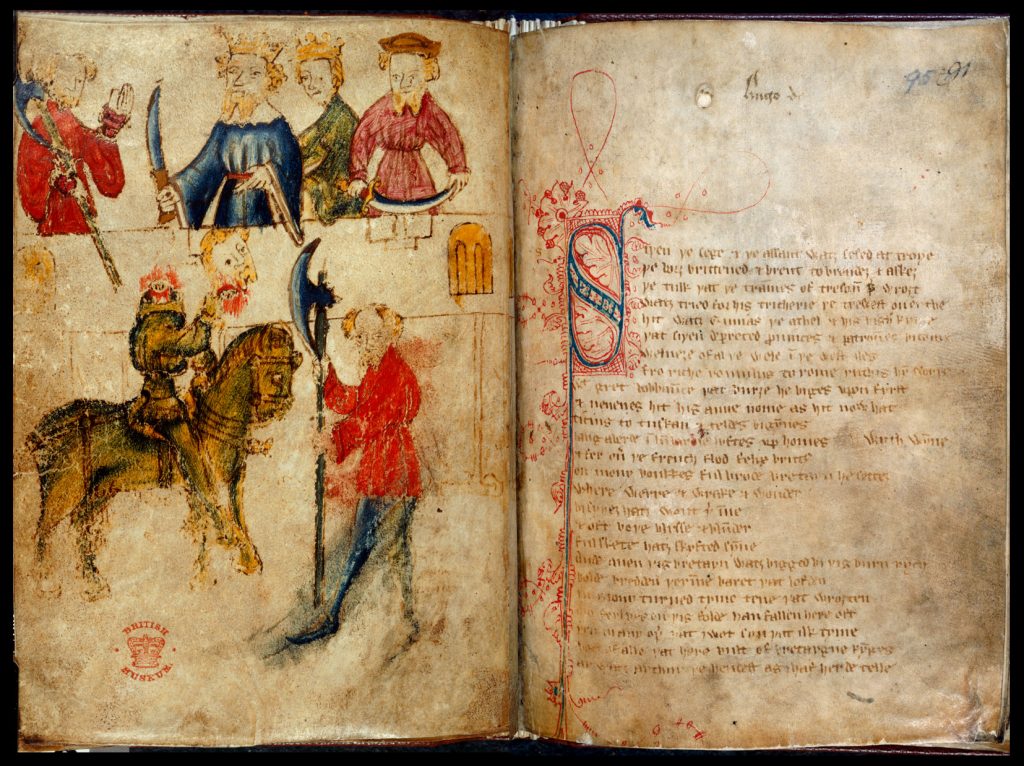

Kelin: Middle English is what Chaucer was writing in, and if you look at the words, you can mostly parse out what it’s saying, but hearing it spoken is so cool.[15]

Fig. 4. Beginning of “Knight’s Tale,” Geoffery Chaucer, Canterbury Tales, c. 1400-1410, Huntington Library and Museum, mssEL 16 C 9 (Ellesmere Chaucer), f. 10r. https://hdl.huntington.org/digital/collection/p15150coll7/id/2385.

One of my favorite things is when people do readings in Old and Middle English because the pronunciation is so different. They had sounds that we don’t use anymore, that have fallen out of the alphabet entirely.

Liam: One of the videos I’ve seen is of a British scholar who learned to speak Old English and studies the roots of the language. He said, “In theory I should be able to go up to a Friesian farmer and speak Old English, and he’ll be able to comprehend what I’m saying.” And it worked. He went up to this guy and negotiated the buying and selling of a cow.[16]

Brinna: In college, there was an English department student group that hosted an event where we traipsed through the woods, and one of the professors read Beowulf.[17] Language is an important cultural connector. In the Middle Ages, they were living in a global world, just like we are.

The Islamic Golden Age and Beyond

Liam: Also, when you mentioned how people think of the Middle Ages as the “Dark Ages,” I thought about the Golden Age in the Islamic world.[18] They made huge advances in mathematics, science, hygiene–

Brinna: Medicine.

Liam: Air conditioning.

Brinna: Architecture.

Liam: Plumbing. The Islamic world was far more advanced than Europe at that time.

Kelin: I worked as a project manager on an exhibition called Lumen: The Art and Science of Light.[19] Working on that project, I got to know a lot more about the Islamic scientists and mathematicians making these advances. During the Middle Ages, the Islamic world made a lot of progress in astronomy and in optics and the understanding of how images are formed in the brain. Their works were translated into Latin by European scholars, but these people in medieval Europe were not inventing these ideas. Hopefully that project will help correct those misconceived notions.

Fig. 5. Astrolabe inscribed in Arabic, Abd al-Karim al-Asturlabi (“The Astrolabist”), 1241/2 CE (AH 638), Ayyubid Dynasty, Turkey, Iraq, or Syria, British Museum, 1855,0709.1. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/8074001.

On that note, I’d like to talk about medievalism outside of Europe. I’m really glad, Liam, that you brought up the discoveries happening in Arab communities. The fact that you are aware of that knowledge center (Baghdad), as a non-historian, would excite a lot of medievalists who have been trying for decades to highlight the global Middle Ages in their research.

Liam: Big shout out to Hassan Piker for that one.

Brinna: One of the benefits of a globalized society is getting to interact with the media from different cultures more easily. I was really interested in manga as a kid, but it wasn’t as common to be engaging with cultural products from other countries. It was a weird, niche interest. Now, we have easy access to content from all over the world and part of that is media about their own historical periods.

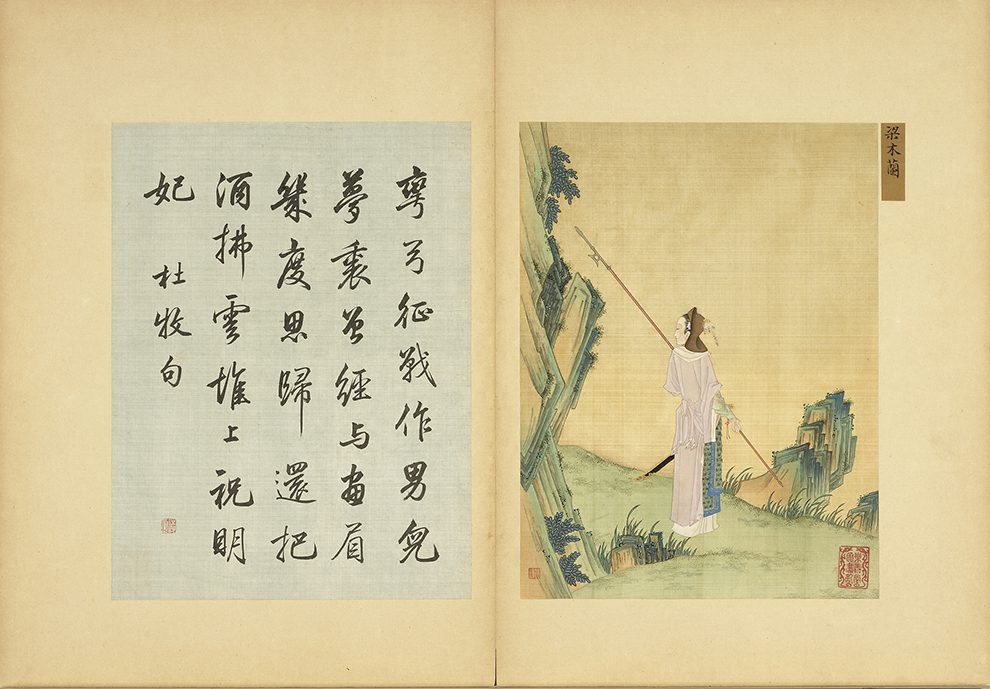

Kelin: That’s a good way to see the flip side of this fast-paced, digital world. Many cultures we are exposed to through media are technically in the Middle Ages, just not the western European Middle Ages. For example, The Emperor’s New Groove[20] is set during the Inca Empire in South America. If we’re going by the European structure of time, 500 to 1500 roughly. We have Aladdin,[21] which happens in the Middle East (a term based on a western Euro-centric idea of the world), around the fifteenth century. We have Mulan, set in China around the fourth to sixth centuries.

Fig. 6. Mulan of Liang, He Dazi (painter) and Liang Shizheng (author), from Gathering Gems of Beauty (畫麗珠萃秀) Qing Dynasty (18th century), National Palace Museum, Taipei, 故-畫-003412-00009. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

And, we have, more recently, Moana[22] (c. first century in the Polynesian islands), and Raya and the Last Dragon (c. “thousands of years ago” in a fictional land that draws from Southeast Asian cultures).[23] Most people still don’t think of those movies as “medieval.” Why do you think that is?

Brinna: I’ve talked with you guys before about my deep frustration with the US educational system. We spent, what? Three years learning about the American Revolution? You know what I never learned about in the entirety of K-12, except for maybe offhand comments? Anything about China, Japan, India, the South Pacific–none of that. The only time they’re mentioned was when Europeans or the US were involved. We didn’t have the chance to learn about 70% of the globe. Then I’d watch something like Mulan with no context because I hadn’t learned about the history of any Asian communities.

Liam: I benefited a bit from the curriculum changing to include more world history. Ancient times to the Middle Ages were mainly spent on Rome, but we also spent some time on ancient China.

Kelin: That’s good to hear.

Brinna: Yeah, and we only took about half a semester to talk about the more modern history of Africa.

Kelin: That’s a good point: on our list of movies, not one is about Africa. Africa is an entire continent and there is not a single movie that we thought of that’s set in Africa.

Liam: Netflix has a new series on African folk tales.[24] They’re like 20-minute episodes on different stories from different regions in Africa.

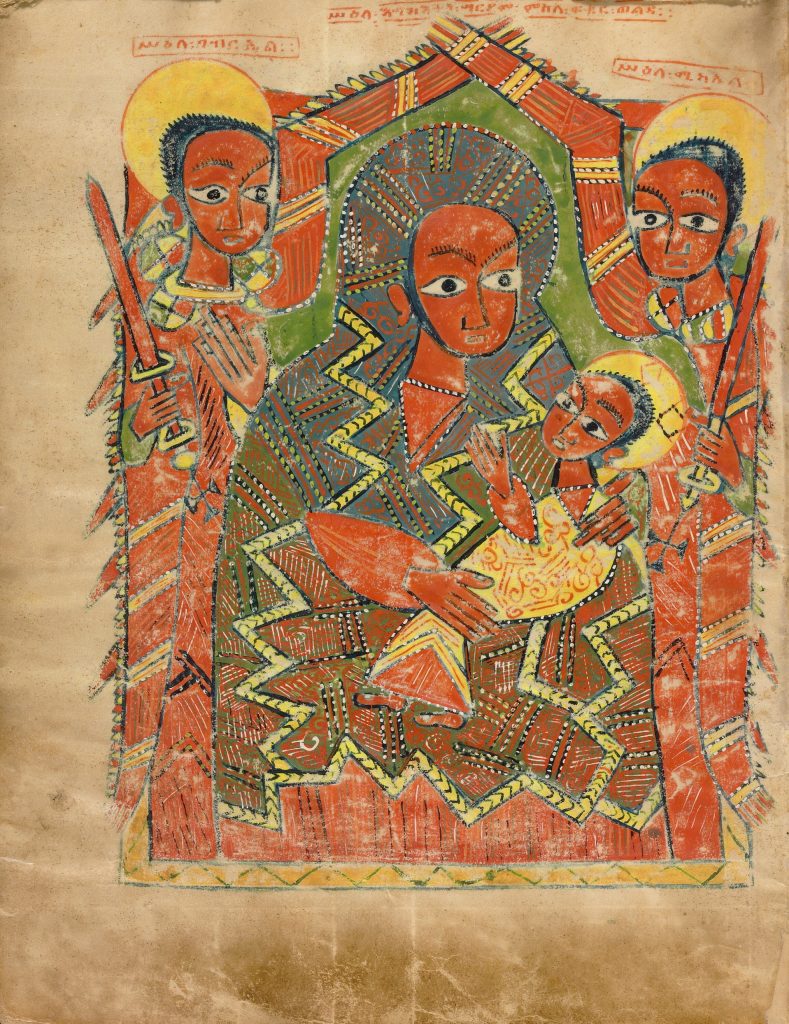

Brinna: Interestingly, I’ve learned more about parts of African history from working at the theological library than anything else. I didn’t know anything about the history of Ethiopia until I came here and talked with my Ethiopian coworker about his country.

Kelin: I didn’t know about the rich history of Ethiopia until I came to manuscript studies. At the Getty, I made a video on a medieval Ethiopian gospel book with Smarthistory.[25] Ethiopia has a very long history of Christianity that dates all the way back to the 4th century.

Fig. 7. The Virgin and Child with the Archangels Michael and Gabriel, about 1504-1505, Ethiopia, J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 102 (2008.15), fol. 19v. https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/object/109D2E.

Liam: There’s also a huge population of Ethiopian Jews.

Kelin: Exactly. It’s like a little nexus point from which you can introduce people to an area of the world. But more needs to be done. Africa is where colonialism has had one of the most extreme effects on what survives and what doesn’t. I can’t even put into words how enraging it must be for people from all regions of the continent and from the whole African diaspora.

Accuracy vs. Vibes

Kelin: Another interesting thing–sometimes painful with Disney because it can be really racist– is how they make movies with historical content that’s relevant to contemporary audiences. There’s the idea of faithfully adapting something or telling the “true” historical narrative, which I find problematic. As a medieval art historian, very rarely do we have enough evidence to say, “This is 100% truthful, exactly what happened, when, and who was involved.” What a lot of medievalism content does is strike a balance between conveying what we know historically, while trying to impart upon modern audiences how it felt to experience the events in the narrative’s original time and place.[26]

Brinna: OK, so like Robin Hood…[27]

Brinna: “Let’s tell the story in a fun, pleasant way that doesn’t involve the Crusades.”

Kelin: “We won’t talk about the Crusades in this children’s movie.”

Liam: “Where was Richard? Ohhh, we don’t talk about that.”

Kelin: “That crazy crusade. Ah ha! Ah ha!”[28] They’re Easter eggs for adults. The more history you learn and the more you experience in the world, the more you recognize. That’s why the crazy crusade joke is so funny to us now.

Liam: This is tangentially related because we’re talking about Robin Hood, but I have a Pandora station for an artist named Colter Wall,[29] who sings traditional, Appalachian, narrative-driven country music.

Fig. 8. Colter Wall at Codfish Hollow, Maquoketa, IA, October 27, 2018. Photo by Roberta, Colter Wall-9.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Colter_Wall-9_(48031452512).jpg.

And, every once in a while, “Oo-De-Lally,”[30] will play on the channel.

Kelin: I’m pretty sure that the guy that did the music for Robin Hood was a country folk artist.[31] Musicians draw upon these motifs that pop up and, even if you don’t recognize it consciously, you’re like, “There’s something familiar about this.”

Brinna: In the middle of the movie, there’s also “The Phony King of England”[32] scene. It’s essentially a hoedown. An all-American jamboree.

Liam: Really, the birth of American country music comes from Scots-Irish immigrants that settled in Appalachia.[33] They took their traditional music and then crafted or found new instruments that created similar sounds. Like the banjo sort of mimics the mandolin.

Kelin: That’s something cool about that scene Brinna mentioned in Robin Hood because people who were watching that movie when it came out in the 70s were probably like, “Oh, I get it.” They’re not thinking it’s “truly” medieval, but they got the modern vibe equivalent.

Knight’s Tale does that really well, too. At its heart it is a medieval story, but it’s set to modern music. At first, it’s kind of disruptive because you’re like, “Why are they playing Queen’s ‘We Will Rock You’ as a knight walks into the stadium?” As the movie goes on, you don’t forget it’s modern music, but you understand how the music is used to make you feel like you are participating in the story. Of course they didn’t have Queen in the medieval period, but they had fanfare, music, and entertainment during tournaments that gave a similar feeling that the soundtrack gives to modern audiences.

Liam: Like in Peaky Blinders, The White Stripes are a regular feature in the soundtrack.

Kelin: Exactly! There’s a whole spectrum. You have ridiculous, out of this world adaptations, a middle ground with something like a Knight’s Tale and then a more historically “accurate” side, with adaptations like The Green Knight[34] with Dev Patel, where they actually made medieval instruments to use in the score.

Fig. 9. The Green Knight at Camelot, c. 1377-1400, British Library MS Cotton Nero A X/2 (facsimile), f. 94v-95r.

https://bit.ly/3TDvgGX

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sggk-illustration-and-first-page.jpg.

People are often criticized for trying to be too historically accurate when you can’t be, but are also chastised when they just try to have fun and form a connection with the source material. There’s room for that whole spectrum. You just have to be upfront about what you’re doing so that audiences know what to expect.

Quest for Camelot and Female Representation

Kelin: There’s a whole slew of non-Disney animated movies, too, like Quest for Camelot![35]

Brinna: This movie is so good! First of all, it has an incredible cast. Pierce Brosnan is in this, Gary Oldman…

Kelin: Cary Elwes, Eric Idle, Jane Seymour.

Brinna: It draws on Arthurian legend, set after the founding of Camelot and the establishment of the Round Table. It centers on a young woman, Kayley, who wants to follow in her father’s footsteps and become a knight. She teams up with a blind man–Garrett, who lives alone in the woods with a magic falcon–to stop the main antagonist, Ruber, from trying to take over Camelot by stealing Excalibur. His villain songs are top notch.

It’s based on a book, The King’s Damosel, by Vera Chapman,[36] which I have yet to find a copy of.

Kelin: What I love about Quest for Camelot, besides the music, is that it has a female protagonist and she’s a knight. It was so cool as a kid. I was like, “Kayley’s awesome!” She’s fighting and she doesn’t even have any real training. But she’s got moxie, you know? And I thought, “I can be like that, too!”

Brinna: When you watch it as an adult, you realize her mom is incredible, too. Lady Juliana is–

Kelin: Awesome. After her husband dies, she keeps up her whole estate. Great female characters in that film.

Adaptations are interesting. Some of the best don’t just replicate the source material, but try something slightly different. I know not everyone agrees. A lot of people complain, “This exact detail wasn’t exactly how it was in the book. I hate it.” But, as long as the adaptation has good storytelling and the changes are logical, I appreciate the adaptation as its own creative endeavor. Especially Robin Hood and King Arthur, where the stories have been told countless times. The fact that they’re still being remade in today is a testament to the staying power of medieval history and the sustained interest in it.

Calvinism vs. Catholicism

Liam: If we’re talking about how the medieval sticks around today…Prior to Calvinism, money was not really something that concerned most people. Most people got what they needed from subsistence agriculture or through bartering and trading. But Calvinism introduced the idea that God’s chosen are the people who have wealth.[37] Today’s hustle culture has a direct line back to Calvinism.

Brinna: Calvinism, as part of the Protestant movement, began as a response to the Catholic Church becoming ingrained in politics and economy, all the opulence.

Kelin: Specifically, Catholic indulgences, where you pay a certain amount to the church, and your sins are forgiven.

Fig. 10. Document establishing the indulgence to the faithful who visit the chapel of St. James in the parish church in Glatz, Silesia (Poland), 1500. Photo by Jacek Halicki.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dokument_odpustowy.jpg.

Brinna: This is a super simplification of the Reformation, apologies to all of my coworkers who are Reformation experts.

Liam: Don’t come at me in the comments.

Brinna: Since Calvinism was part of this movement, it’s interesting that they almost went so far theologically in one direction that they came all the way back around.

Kelin: The idea that the pendulum swings so far that it goes all the way back around is really interesting. It’s a good illustration of how things that happened centuries ago still affect our political and socioeconomic structures. Something that’s really important to me is to make sure that people understand the relevance of historical material to today’s world, because we’re getting dangerously close to saying history doesn’t matter, that the humanities don’t matter. There’s emphasis on blind trust without critical thinking. We live in a culture that’s so fast moving and inundated with sources, that it’s very easy to get lost and not understand where these ideologies, political leanings, and religious ideas came from. It’s important to keep history and critical thinking in our education system and in the minds of the people.

Liam: One way Calvinist philosophy has become embedded in Western politics is in the concept of individual moral responsibility. For example, the way the homelessness crisis is handled. Why are there so many requirements for a homeless person to get housing? They have to meet all of these prerequisites to get care from the community. This idea of the prosperity gospel is blurred with the concept of individual moral responsibility, which prompts people to ask, “Why do they deserve our help?”

Kelin: Being a human isn’t enough, you have to prove your value.

Liam: Exactly. That has had a lot of damaging effects on our society today and why we almost completely lack a sense of communalism.

Brinna: Take that idea of communalism and circle it back around to our discussion of Redwall, of this example of what communal life looked like before: the church, these abbeys, were centers where they provided health and spiritual care, food, and shelter.

Kelin: And that care preceded assessing someone as a “contributing” member to society. You didn’t necessarily have to prove your worth first, you were often automatically subsumed into the community, and then nurtured so that one day you could provide care in turn.

Brinna: We’ve been talking about accuracy a lot, and this is one of the stumbling points, telling medieval stories within a society that operates on modern social rules. When stories with an individualistic moral are told in historical settings, there’s a disconnect. We live in a society where the individual is prized above all else, but it’s anachronistic to tell a story like that in a medieval setting. Take The Witcher,[38] where a character goes through towns and everyone hates him because “he’s different.” But, if this guy came by and killed the monster that was eating half of your town, I imagine most medieval people would at least be–

Kelin: Pretty psyched.

Brinna: They would probably give you a meal and a place to stay. The books have a little more nuance in that regard than the show or games.[39]

Video Games 101

Brinna: Segueing into video games, The Witcher games are part of a genre that’s built heavily on medievalisms. They’re generally open-world, action, role-playing games, like Skyrim,[40] Dragon Age,[41] and Assassin’s Creed.[42]

Liam: There are also games like Chivalry,[43] that’s more like a first-person shooter in a medieval setting. Or 4 by 4 strategy games like Sid Meier’s Civilization Revolution,[44] where you’re focused on growing one city or settlement into a nation. Crusader Kings III[45] is similar, but is focused on diplomacy. Then there’s games like Medieval Dynasty,[46] which is a survival game. The goal of the game is to build a family name and rise to the class of nobility. Something completely different is a game called Blight: Survival,[47] a MMORPG, massive multiplayer online role-playing game, set in the Middle Ages during a zombie apocalypse. Essentially, you roam the French countryside in full plate armor hacking up zombies.

Then there’s Kingmakers,[48] where the player’s character is from the modern world and is sent back in time with modern technology and weapons to prevent something from happening in the Middle Ages. This is the dream of every military history nerd that has ever lived. You watch a King Arthur movie or one that involves a siege, and think, “Imagine how easily these people would win if they just had an M60 machine gun mounted on those walls.” In Kingmakers, you can drive a pickup truck straight through a battlefield. You get an AK-47, a grenade launcher…

Brinna: Those are such fun combinations of genres. Thinking of games that are set in more classically historical, and specifically medieval, time periods, there are games like A Plague Tale,[49] which is about a pair of siblings during the Hundred Years War in France. And I’d like to specifically discuss the Assassin’s Creed series. The first game takes place during the Crusades, but the perspective of the player character frames the European Crusaders as the antagonists.[50] For someone raised in Western, Eurocentric society, that’s an eye-opening and refreshing change. The games follow actual historical events and feature real historical figures.

Kelin: A lot of academic scholars consult on the Assassin’s Creed games, too. One that recently came out is set in the Middle Ages in the Middle East, the Arab world–

Brinna: Mirage![51] It’s in Baghdad.

Fig. 11. Promotional art for Assassin’s Creed Valhalla. © Ubisoft 2020.

Kelin: A professor at the University of Edinburgh, Dr. Glaire Anderson, consulted on the project.[52] She has a huge digital presence, loves working with digital humanities, and has a whole center in Edinburgh set up for cross-cultural work, with the Islamic world as its focus. Just one more cool area of collaboration where you can bring in real history and combine it with these cool video games.[53]

Brinna: Video games aren’t always thought of as digital humanities, but they often are. A great example is Valhalla.[54]

Fig. 12. Promotional art for Assassin’s Creed Mirage. © Ubisoft 2023.

You play as a Norse Viking who comes to England to set up a town in the 870s. You interact with the Anglo Saxons, encounter the remnants of Roman occupation, and fight alongside the Ragnarssons against Alfred the Great of Wessex. There’s a DLC where you take part in the 885 Siege of Paris, and another where you travel to Ireland and help establish Flann Sinna as the High King. There’s a whole side plot where you establish Dublin as an international trading power. Your business partner is Azar, from the Abbasid Caliphate, and you trade with the Byzantines, the Rus, Egypt, and the Iberian Peninsula.

Kelin: That comes back to this global world. Actual trade was happening between these places, it’s not fictional. We have documentation. On top of accurate or more historical medieval games, there’s games like Pentiment.[55] I haven’t played yet, but I really want to. As someone who studies medieval manuscripts, it’s made for me. You play as a manuscript artist from Nuremberg, who has to investigate a series of murders. It’s basically The Name of the Rose[56] in video game form.

Brinna: And it’s beautiful.

A Bright Side

Liam: On a more hopeful note from some of the issues we talked about before, the law of dialectic materialism is that, just like in physics, with every action there’s a reaction. There’s a lot of people coming together and pooling resources to build small communities. There’s a desire to make life simpler, to make technology and distractions a smaller part of our lives.

Kelin: Tempering them. This is why the Middle Ages are such an enticing time period because people view it as a simpler time. The amount that we’re expected to do just because we have access to the means to do it–not because we have the energy, time, or the money to do it–is exhausting. There are always memes or GIFs going around about, “Oh you thought it was bad in the feudal period. At least they had this and that provided for them….” It might have been better in some respects, but they also didn’t have modern medicine, so…people posting that content indicates to me that they are interacting with the medieval, not just on a fantasy level, but in a semi-informed way. They’re curious about the socioeconomic and political structures and if there’s any truth to their vilification. My goal with projects is to show people how the medieval period is still relevant.

Liam: Is it better or worse now? We have modern medicine and refrigeration and things make our lives easier, but how much of our lives are spent working? On average, a 13th-century laborer would have up to 25 weeks off.[57] Which doesn’t mean that they’re not doing any labor, but the labor that they’re doing is for themselves. I think the statistic is that modern day laborers spend 80% of their waking hours doing labor that benefits someone else.[58] It would be interesting to bring specialized medieval knowledge and modern labor movement knowledge together on something like this. Kelin, you might be interested in reaching out to academics studying labor history. The decades following the Black Plague were some of the most prosperous years for laborers. Coming out of COVID, we saw a similar phenomenon with the Great Resignation.

Brinna: Another labor comparison we can make is the role of craftsmen, which Ren Faires continue to showcase. There are blacksmiths, armorers, candlemakers, clothiers… There’s always someone selling spices and herbs. I talked to a woman selling handmade soaps and she taught me about historical cleaning products.

Fig. 13. Brinna (right) with friends Haley Jones (left) and Elijah Howard (center) in costume at the Georgia Renaissance Festival. April 2024.

These craftsmen carry a lot of knowledge that would have been commonplace in the Middle Ages. Another example is this hair stylist who recreates Roman hairstyles.[59]

Liam: Especially in an age where almost all of your work product is digital and doesn’t have an easily visible impact or a purpose. Maybe you made soap as your trade and that may not be fancy and it might not carry a high status, but you’re providing a service for the community that is essential. If people don’t have soap, disease can spread.

Brinna: There’s a tangible value.

Kelin: Even though in the digital age, you might feel like nothing you do makes an impact, I think it does. It can be very degrading and frustrating when you seem to work without purpose, recognition, or compensation. It’s hard to get over that, even when I look at a project and I think, “This is a chance for me to help people connect with history.” While the system is rigged, I have to believe it’s important work. Going back to economics, it’s assigning value based on what you can give to the community instead of supporting your community members upfront and then nurturing them to become a productive member of that community. You can see the potential for the work that you’re doing but as an individual, you are exhausted and feel undervalued. It’s hard to get those two things to work in tandem in order to reach your potential.

Liam: For any other politics nerds that may read this, we’re talking about the concept of the alienation of labor.[60]

Wrapping Up

Kelin: Do you have anything you want to end on?

Brinna: You may not think you have any interest in the Middle Ages or that it has any impact on you, but it can be subtle in how it manifests itself in your life.

Kelin: You might realize connections to it later in life. That’s what really came through talking with you, Liam. Contemporary economics and politics are so enmeshed with things that happened centuries ago. There are so many ways history lives on in our everyday lives.

Liam: When most people think about history, they think of dates, names, places, battles. And that’s an unhelpful way to frame it. Instead, consider ideas and concepts and relationships between people, how societies are structured and how certain events influenced the course of history. For me, history is a collection of stories about people and how they interact with each other. If you want to understand why people are the way they are and why they do things now, it’s helpful to look back and see how we were dealing with each other historically. Because not a lot of things have changed.

Brinna: And sometimes it’s really heartening to think, “That person in 1293, doing their best, they’re exactly like me.”

Kelin: Being able to look back and learn something about yourself or about the world around you, even though the thing you’re reading or looking at, maybe a painting or a medieval manuscript, was made 1000 years ago, and say, “Oh, I get that. I understand how this is relevant to me.” Learning something from it is a really cool experience.

Liam: One way I’ve found that makes the learning process easier is using the concept of OPVLs: origin, purpose, value, and limitation. By considering those four concepts, you can critically evaluate resources by assessing where they come from, who wrote them, and why. The most important part is the “why.” They won’t write it for no reason. They have a goal and you need to figure out what that goal is. Then consider the limitations of a source. What information did that creator author have available to them? What was not available to them? What could they be missing? What might they be purposefully leaving out?

Brinna: What you’re describing, those are information literacy techniques, ways to assess the information. That’s what libraries are secretly all about. Go to your library. Go talk to your librarian. This is my shameless plug for libraries. Libraries matter because people are still enjoying stories. They’re still looking to learn their history and the history of others.

Liam: And show up to your local government meetings because there’s a lot of censorship happening at local libraries and it is getting to the point where some libraries are having to shut down completely. So, show support for your local library.

Brinna: Don’t let the lords rule the fief without your consent. Rise up in the serf rebellion.

Kelin: Maybe to close out, focusing on the idea that everything is a story is very important. Liam, you said looking back into history, it’s like everything, including us, is just stories. And Brinna, you were saying that people are still interested in those stories today. I’m going to be really cheesy and end by saying that I have a tattoo of a quote from Doctor Who that starts with, “We’re all stories in the end…” I think I got that tattoo because the sentiment really sticks with me, and without knowing it, I think it sticks with a lot of people. It’s this urge to know where you came from, to connect with history, to understand it and to understand how it’s impacted people’s lives today. Thanks guys! This was really fun!

Fig. 14. Kelin, Liam, and Brinna Michael taking a silly photo as Tinkerbell, a knight, and Mulan. Halloween 1999.

References

| ↑1 | alex3yoyo, “The 2009 West Middle School Trebuchet Club,” YouTube Video, March 10, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bJ1rKV9gCU. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Stephen Gerringer, “The Hero’s Journey & Joseph Campbell,” Joseph Campbell Foundation, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.jcf.org/learn/joseph-campbell-heros-journey. |

| ↑3 | Richard D. Wolff, “About Richard D. Wolff,” accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.rdwolff.com/about. |

| ↑4 | Philip Naudus, “Mulanbook,” accessed July 11, 2024, https://mulanbook.com/. |

| ↑5 | “A Knight’s Tale,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0183790/. |

| ↑6 | “Redwall,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0200369/. |

| ↑7 | “Timeline,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0300556/. |

| ↑8 | “Medieval Monasteries,” School History, accessed July 11, 2024, https://schoolhistory.co.uk/notes/medieval-monasteries/. |

| ↑9 | Helena von Sadovsky, “Honor and Defense: Tournament Armor in the Late Medieval Ages,” The Trident, updated April 28, 2022, https://sites.owu.edu/trident/2022/04/28/honor-and-defense-tournament-armor-in-the-late-medieval-ages/. |

| ↑10 | Shuhua Qin, “Medieval Archery – The Longbow,” The John Moore Museum, updated August 17, 2021, https://www.johnmooremuseum.org/medieval-archery-the-longbow/. |

| ↑11 | Matthew Strickland and Robert Hardy, The Great Warbow: From Hastings to the Mary Rose (Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, Ltd., 2005). |

| ↑12 | Will Cohu, “How they did affright the air at Agincourt,” The Telegraph, updated April 3, 2005, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/3639756/How-they-did-affright-the-air-at-Agincourt.html. |

| ↑13 | Insider, “ Traditional Archery Expert Rates 10 Archery Scenes In Movies And TV | How Real Is It? | Insider,” YouTube Video, 20:24, December 21, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFleLL5zlaI; Insider, “Traditional Archery Expert Rates 11 More Archers In Movies | How Real Is It? | Insider,” YouTube Video, 21:48, December 19, 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KXxmgv_0LYc. |

| ↑14 | “Ranger’s Apprentice,” The World of John Flanagan, Penguin Random House, accessed July 11, 2024, https://worldofjohnflanagan.com/#rangers-apprentice. |

| ↑15 | “The Criyng and the Soun: Chaucer Audio Files,” Baragona’s Literary Resources, accessed July 11, 2024, https://alanbaragona.wordpress.com/the-criyng-and-the-soun/. |

| ↑16 | Bay Yildirim, “Talking to a Frisian farmer in Friesland with Old English,” YouTube Video, 2:42, May 2, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cZY7iF4Wc9I. |

| ↑17 | Kemp Malone, Beowulf (Complete): Read in Old English, Caedmon Records, TC 4001, 1967, LP, https://archive.org/details/lp_beowulf-complete-read-in-old-english_kemp-malone. |

| ↑18 | Ahmed Renima, Habib Tiliouine, and Richard J. Estes, “The Islamic Golden Age: A Story of the Triumph of the Islamic Civilization,” in The State of Social Progress of Islamic Societies, ed. Habib Tiliouine and Richard J. Estes (Cham: Springer, 2016), 25-52, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24774-8_2. |

| ↑19 | “Lumen: The Art and Science of Light,” PST ART, Getty Center, accessed July 11, 2024, https://pst.art/en/exhibitions/lumen-the-art-science-of-light. |

| ↑20 | “The Emperor’s New Groove,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120917/. |

| ↑21 | “Aladdin,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024,https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0105935/. |

| ↑22 | “Moana,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024,https://www.imdb.com/title/tt3521164/. |

| ↑23 | “Raya and the Last Dragon,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5109280/. |

| ↑24 | “African Folktales, Reimagined,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt27201556/. |

| ↑25 | Kelin Michael, “Gospel Book Getty Conversations,” in Smarthistory, March 28, 2022, accessed July 12, 2024, https://smarthistory.org/gospel-book-getty-conversations/. |

| ↑26 | Terry Roberts, “When Is Historical Accuracy Inaccurate?” Writer’s Digest, published July 26, 2021, https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/when-is-historical-accuracy-inaccurate. |

| ↑27 | “Robin Hood,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0070608/. |

| ↑28 | GURGEN YENOKYAN, “Robin Hood (1973) – Uh, King Richard? I’ve told you never to mention my brother’s name!” YouTube Video, 1:54-2:08, February 13, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wlW-asUei7w. https://doi.org/10.17498/kdeniz.1099186. |

| ↑29 | “Colter Wall,” Sony Music Entertainment, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.colterwall.com/. |

| ↑30 | Roger Miller, “Oo-De–Lally,” track 2 on Robin Hood (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack), Walt Disney Records, 1973. |

| ↑31 | Kelin Michael, “What Did the Middle Ages Sound Like?,” Getty, published June 22, 2022, https://www.getty.edu/news/what-did-the-middle-ages-sound-like/. |

| ↑32 | Phil Harris, vocalist, “The Phoney King of England,” by Johnny Mercer, track 4 on Robin Hood (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack), Walt Disney Records, 1973. |

| ↑33 | Connor Lee, “‘Down THese Hollers and Hills’: The Scots-Itish Influence on Appalachia Through Its Music,” Medium, published December 12, 2017, https://medium.com/@connoraidenlee/down-these-hollers-and-hills-the-scots-irish-influence-on-appalachia-through-its-music-5f6863322d78. |

| ↑34 | “The Green Knight,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt9243804/. |

| ↑35 | “Quest for Camelot,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0120800/. |

| ↑36 | “The King’s Damosel,” Goodreads, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2455496.The_King_s_Damosel. |

| ↑37 | Chip Berlet, “Calvinism, Capitalism, Conversion, & Incarceration,” The Public Eye 18, no. 3 (2004): 8-15, https://politicalresearch.org/2004/11/06/calvinism-capitalism-conversion-and-incarceration. |

| ↑38 | “The Witcher,” IMDb, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt5180504/. |

| ↑39 | “The Witcher Saga,” Sapkowski Books, accessed July 11, 2024, https://sapkowskibooks.com/pages/about-the-writer#the-witcher-saga; “The Witcher,” CD PROJEKT RED, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.thewitcher.com/us/en/. |

| ↑40 | “The Elder Scrolls,” Bethesda, ZeniMax Media Inc., accessed July 11, 2024, https://elderscrolls.bethesda.net/en. |

| ↑41 | “Dragon Age,” BioWare, Electronic Arts Inc. (EA), accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.ea.com/games/dragon-age. |

| ↑42 | “Assassin’s Creed (Series),” Ubisoft Entertainment, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/game/assassins-creed. |

| ↑43 | “Chivalry II,” Torn Banner Studios, Ontario Creates, Tripwire Presents, Canada, accessed July 11, 2024, https://chivalry2.com/. |

| ↑44 | “Sid Meier’s Civilization,” Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. 2K, accessed July 11, 2024, https://civilization.2k.com/. |

| ↑45 | “Crusader Kings III,” Paradox Interactive AB, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.paradoxinteractive.com/games/crusader-kings-iii/about. |

| ↑46 | “Medieval Dynasty,” Toplitz Productions GmbH, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.toplitz-productions.com/medieval-dynasty-lp.html. |

| ↑47 | “Blight: Survival,” And Behavior, accessed July 11, 2024, https://blightsurvival.com/. |

| ↑48 | “Kingmakers,” Redemption Road, tinyBuild, accessed July 11, 2024, https://store.steampowered.com/app/2109770/Kingmakers/. |

| ↑49 | “A Plague Tale: Innocence,” Focus Entertainment, Asobo Studio, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.focus-entmt.com/en/games/a-plague-tale-innocence. |

| ↑50 | “Assassin’s Creed (Game),” Ubisoft Entertainment, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/game/assassins-creed/assassins-creed. |

| ↑51 | “Assassin’s Creed: Mirage,” Ubisoft Entertainment, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/game/assassins-creed/mirage. |

| ↑52 | “Edinburgh art historian helps build new Assassin’s Creed video game,” Edinburgh College of Art, The University of Edinburgh, published July 5, 2023, https://www.eca.ed.ac.uk/news/edinburgh-art-historian-helps-build-new-assassins-creed-video-game. |

| ↑53 | “All Discovery Tour Curriculum Guides,” Discovery Tour: A Ubisoft Original, Ubisoft Entertainment, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/game/assassins-creed/discovery-tour/curriculum-guide. |

| ↑54 | “Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla,” Ubisoft Entertainment, accessed July 11, 2024, https://www.ubisoft.com/en-us/game/assassins-creed/valhalla. |

| ↑55 | “Pentiment,” Obsidian Entertainment, Inc., Xbox Game Studios, accessed July 11, 2024, https://pentiment.obsidian.net/. |

| ↑56 | “The Name of the Rose,” Goodreads, accessed July 14, 2024, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/119073.The_Name_of_the_Rose. |

| ↑57 | Jan Lionsnest, “Do You Work More Than A Medieval Peasant?: An Addendum,” Ye Olde Tyme News, published June 22, 2022, https://www.yeoldetymenews.com/p/do-you-work-more-than-a-medieval. |

| ↑58 | U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “American Time Use Survey Summary,” June 27, 2024, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/atus.nr0.htm. |

| ↑59 | The Wall Street Journal, “Hair Archaeologist? She’s Real,” YouTube Video, 1:36, February 7, 2013, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rajp9T33WMY. |

| ↑60 | Karl Marx, “Estranged Labour,” trans. Martin Milligan, in Economic & Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1959), https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1844/manuscripts/labour.htm. https://doi.org/10.2307/2550890. |