Debra Higgs Strickland • University of Glasgow

Recommended citation: Debra Higgs Strickland, “The Sartorial Monsters of Herzog Ernst” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010). https://doi.org/10.61302/UMFN9577.

Loss of life is the usual outcome when men and monsters meet. Critics have argued that across medieval art and literature, monsters function as negative signifiers of either external or internal enemies to be averted or destroyed, but not brought back home to Mother. Yet this is exactly what happens in Herzog Ernst, a German epic romance that transgresses conventional medieval boundaries of East and West, enemy and ally, Self and Other.[1] In this spirited tale of honor, conquest, and crusade, it is true that exotic Eastern monsters frequently face off with Western knights. But while many monsters are murdered, others become friends, and a privileged few accompany the Duke back to Bavaria to begin a new life in the imperial court.

Leaving aside for the moment the jarring notion of monstrous friends, it is true that there are plenty of other late medieval tales, from Beowulf to the chansons des geste to Chaucer, that feature exotic monsters who clash with valiant knights.[2] Yet by including an entire sequence of episodes involving monsters drawn from the venerable Monstrous Races tradition, Herzog Ernst stands out from the crowd.[3] Some critics have therefore discussed the monsters against the backdrop of this tradition,[4] while others have analyzed them as embodiments of alterity and hybridity, theoretical notions of continuing concern across academic disciplines.[5] However, these types of teratological and theoretical explanations, while important and illuminating, still do not account for the full variety and richness of monstrous behaviors within the narrative structure.

Other approaches have been more historicist, taking as their cue the tale’s imperial, courtly framework and linking its main characters and their deeds to the contemporary politics and personalities of the Holy Roman Empire.[6] While such studies have identified some of the raw material available to the tale’s creator(s) which for a time could have provided it with truth value or even a satirical bent, matchups of fictional characters to real-life ones do little to advance our understanding of the fantastic elements of the story around which the plot revolves. Moreover, they cannot explain the tale’s broader cultural meanings, not only at the time of its creation, but also for later audiences reading and listening to it in different times and places. In other words, something other than references to the deeds of remembered elite individuals must have inspired the diachronic interest in the tale that caused it to be painted, printed, read and reread; in poetry and prose, and in several different versions, from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries.[7]

With previous critics, I concur that the ‘something other’ is the monsters; however, the fact that Eastern monsters end up in the Western court I believe justifies a new interpretative strategy. Because the tale is filled with ekphrasis devoted to descriptions of fancy clothing, fine silks and embroidery, glittering gems, and other forms of luxury, I propose to focus on the fantastic, clothed bodies of the monsters and their well-furnished surroundings—rich stuff for viewing through the theoretical lens of the ‘sartorial body’ as developed by E. Jane Burns in her seminal study, Courtly Love Undressed.[8] I hypothesize that in Herzog Ernst, monstrous bodies and sumptuous clothing function together as interdependent signs of the Eastern exoticism crucial to the formation of Western courtly identity, thus opening the way for a new application of Burns’ critical method of ‘reading through clothes.’[9]

In her innovative analysis of medieval French romance, Burns examines ways in which sumptuous elite clothing and furnishings fashioned from costly silks, gems, gold, and silver define courtliness, gender conventions, and social roles in courtly love scenarios. She argues that French courtly players are not simply bodies, or their clothes, nor even Westerners wearing Eastern clothes; but rather are clothed bodies— ‘sartorial bodies’—for whom costly silks, gems and precious metals imported from the East become intrinsic markers of French courtly identities, thus troubling conventional notions of an East-West dichotomy.[10] In Herzog Ernst, Eastern opulence and the sartorial bodies it helps to create follow a different geographical route that I suggest is complemented— and complicated—by the matter of the monsters. While reading through clothes in medieval French romance exposes the presence of the East in the space of the Western court, in Herzog Ernst, the monsters encountered in the East already wearing courtly garb forecasts their future occupation of this Western space, thus revealing an ideological concern with the process of formulating courtly identity. Tracing this process via the moving monsters is what I hope this brief study will facilitate.

Because monsters are necessarily scopic experiences (whether recorded visually or verbally), I will pay close attention to just a few of the pictorial illustrations that have survived in one of the few early printed copies of Herzog Ernst that contains an extensive pictorial series.[11] To do so constitutes another expansion of Burns’s method. In her study of French romance, Burns excludes contemporary illustrations from analytical consideration on the assumption that the images are less elaborately detailed than the texts.[12] But even if this is so, the fact that pictures were part of the audience’s experience alone justifies their inclusion in analysis.[13] After all, beyond simple illustration of the narrative, medieval images had other important functions, including the power to shape reader perceptions by contributing meanings not mandated by their accompanying texts. In her diachronic analysis of artistic representations of clothing, Anne Hollander persuasively argues that perceptions of clothing in literature are pre-conditioned by memories of their depictions in works of art,[14] which raises still another question about excluding the illustrations from analyses of illustrated texts.[15] In the case of Herzog Ernst, I hope to show how some of the work’s pictorial illustrations help to shape reader perception of the tale by significantly augmenting, and also redirecting, the signifying power of clothed, monstrous bodies.

* * * * *

This, in brief, is the story as recounted in the earliest version of the complete tale extant in German (known as Herzog Ernst B), which is dated to the end of the twelfth or beginning of the thirteenth century.[16] It thus postdates the historical personages it mentions by at least two centuries and predates its (extant) pictorial illustration by about the same. The action begins in Bavaria. Owing to the treachery of a jealous Count Heinrich, Duke Ernst is banished from the imperial court where he was formerly the favorite of his stepfather, Emperor Otto III, who married his widowed mother, Adelheid. In retaliation, and with the assistance of his loyal friend, Count Wetzel, Ernst murders the treacherous Heinrich, an act that unleashes six years of fierce attacks by the Emperor’s army upon the Duke’s knights, lands, and properties. Unable to hold out any longer, Ernst is forced into exile with Count Wetzel and a retinue of fifty loyal knights. With the goal of regaining the Emperor’s favour, the Duke vows to go on crusade to Jerusalem to fight against the heathen; fully one thousand knights take up the cross alongside him. Headed towards the Holy Land, they travel for several years across exotic Eastern lands where they encounter dangers and marvels, such as giant griffins and a magnetic mountain, as well as a series of fantastic races of monstrous men. Some of the latter, such as the richly dressed Crane Men of Grippia, are murderous tyrants; but others, notably the one-eyed One-Stars of Arimaspi, are peaceful and just. Less protracted confrontations with one-legged, huge-eared, gigantic, and tiny folk also take place. Between encounters of alternating violence and negotiation, the Duke accrues a small but diverse entourage of monsters who accompany him to the Holy Land by way of Ethiopia. Once they reach Jerusalem, Ernst makes a pilgrim’s offering at the Holy Sepulchre of half of his monsters along with a quantity of gold, precious stones, and fine silks. He spends the next year there, fighting against the heathen, after which he returns to Bavaria and to the imperial court, bringing with him the remainder of his monsters, by now his close companions—and paradoxically, his valued possessions. With the help of his mother, Empress Adelheid, he finally obtains Emperor Otto’s pardon. Ernst then presents his monsters at court, where the Emperor is so taken by them that he asks if he might keep a few. And so Ernst gifts to Otto three monsters, but he refuses to part with the others, especially the Giant, who is his favorite. Accompanied by the Giant and the rest of his monstrous friends, he finally returns to Bavaria. The Emperor, meanwhile, restores his lands, rule, and reputation. Thus did Duke Ernst overcome all his troubles.

Meet the Monsters

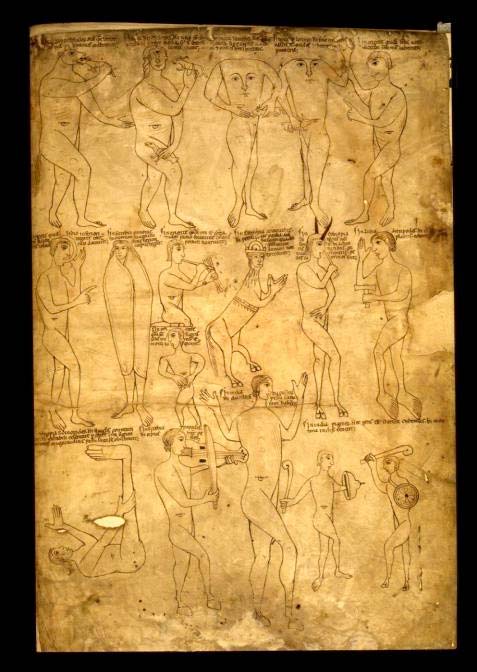

Nearly a third of Herzog Ernst is devoted to what transpires between Duke Ernst and the Crane Men of Grippia (Agrippinni) (Figure 1).[17] As we will see presently, the Crane Men live in luxurious buildings in a beautiful city, have handsome physiques, and a fine sense of fashion, all unusual traits in monsters, to be sure. However, as the tale unfolds, we also find them aggressive, tyrannical, murderous, and speaking an incomprehensible, squawking language. On balance, then, the Crane Men behave as medieval monsters ought, unlike the One-Stars (Einsterne), a type of Cyclopes living in the land of Arimaspi, who are both cultured and congenial. They do speak a strange language but the Duke and his knights master it in a year. Other monsters that adhere more strictly to the monster rules include the Flat Hoofs (Plathüeve), an arrogant people with swan feet that they use to shield themselves from the sun when not hurling missiles against their enemies, the One-Stars.[18] The other enemies of the One-Stars, known simply as Ears (Ören), are so-called because their ears hang down to their feet. They wear no clothes. Not far from the Ears, in the land of Prechami, dwell little people (kleinen liutelîn) —Pygmies—who are at continual war with cranes.[19] The final group on the Duke’s monstrous tour are the fierce, bellicose Giants (Risen) of the land of Canaan, who fight with long, thick steel rods in order to exact tribute from many lands.[20]

Fig. 1. Crane Men versus Duke Ernst and his knights, Herzog Ernst, Augsburg: Anton Sorg, c. 1477, Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek, Ink. H-296, fol. 16v (photograph by permission of the Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek)

To explain the suitability of sartorial analysis for the monsters of Herzog Ernst, it is important first to situate them in their broader artistic and literary contexts with an eye towards highlighting the significance of their clothing. Another reason for this quick survey is to demonstrate the popularity of these particular types of monsters, types with which readers and listeners would have been quite familiar. Finally, because Crane Men are something of a special case among Monstrous Races and yet receive the most extensive description in Herzog Ernst, I shall pay especially close attention to their place in this tradition.

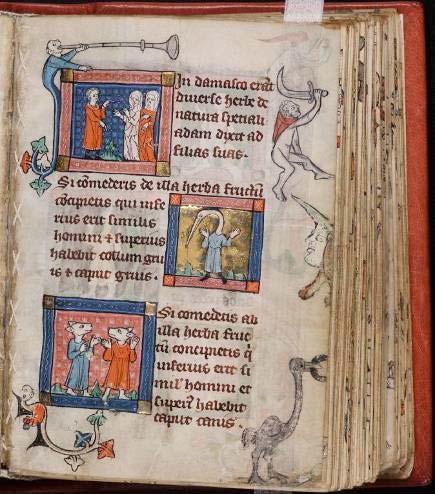

A folio included near the end of the late twelfth-century Arnstein Bible is a visual menu of the standard medieval versions of all of the Herzog Ernst monstrous types, save the Crane Men (Figure 2).[21] Besides the one-eyed Cyclopes, these include the single-footed Sciopod–the prototype of a Flat Hoof; the Panotii with enormous ears (worn here as a cloak), identified in Herzog Ernst as the Ears; a viol-playing Giant, and two tiny, clashing Pygmies holding shields. These are the creatures that Herzog Ernst readers and listeners would have envisioned in lieu of accompanying illustrations, compensated partly by a florid and ekphrasis-filled text. Could a word have spoken a thousand pictures?

Fig. 2. Monstrous Races, Arnstein Bible, c. 1172, London, British Library, MS Harley 2799, fol. 243 (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

And what of the Crane Men? This Monstrous Race receives the most attention in Herzog Ernst in which much is made of their elegant city, furnishings, and dress sense. Far less frequently illustrated in medieval art than Giants, Pygmies, Panotii or Sciopods, Crane Men are known from later medieval texts, such as the fourteenth-century Gesta Romanorum.[22] It is likely to have been the popularity of Herzog Ernst that really put them on the map, specifically the Hereford mappa mundi of around 1300.[23] Situated in the upper left quadrant in Scythia, an unclothed Crane Man beneath a large pelican’s nest leans on a walking stick, his head thrown back and large beak opened wide.[24] Apart from the Crane Man, it has gone unnoticed that the Hereford Map also includes representations of the rest of the main monstrous groups described in Herzog Ernst, a cluster of which are also located in Scythia, northeast of Germany (Germania).[25] Most of them do not wear any clothes.

The Rothschild Canticles, illuminated in Flanders and contemporary with the Hereford Map, includes a fine portrait of a Crane Man wearing black shoes and a long blue gown set against a timeless gold background that suggests symbolic, as opposed to narrative, significance (Figure 3). The accompanying text, which is concerned with the origins of the various Monstrous Races, records Adam’s warning to his unruly daughters that their dietary disobedience will cause them to give birth to human-crane hybrids.[26] Because the Rothschild Canticles manuscript has numerous links to German sources, the unusual presence in both text and image of a Crane Man among other more familiar Monstrous Races, such as the clothed pair of Cynocephali (Dogheads) pictured directly below, might support an argument for the influence of Herzog Ernst.[27] Crane Men both within and outwith Herzog Ernst enjoyed a long life, and continued to be distinguished by increasingly elaborate costumes. A fashionably dressed Crane Man appears in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle alongside portraits of other clothed and unclothed Monstrous Races;[28] and an even more splendidly attired Crane Man graces Ulisse Aldrovandi’s 1642 History of Monsters (Figure 4).[29] With its combined hybrid human – avian head, which contrasts with the Nuremberg and earlier representations that retain fully crane heads, this latter image creates a more biologically synthetic Crane Man that would be difficult to achieve with words alone.

Fig. 3. Adam and his daughters; Crane Man; Doghead, Rothschild Canticles, Flanders, c. 1300, New Haven, Beinecke Library, MS 404, fol. 113 (photograph: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

Fig. 4. Crane Man, Ulisse Aldrovandi, Monstrorum historia (1642), Bologna: Giovanni Battista Ferroni, 1657 (photograph by permission of Bologna University Library; not to be reproduced without the written permission of the Library)

In late medieval and early modern pictorial contexts, then, the Crane Men mix with other and more popular Monstrous Races, but in Herzog Ernst, they stand apart in significant ways. Returning to the twelfth-century monstrous menu (Figure 2), it is notable that all of the figures are naked, a visual sign of their lack of civilization that complements their monstrous behaviour.[30] That is, reader-viewers knew from contemporary sermons, literature, and other pictorial imagery that besides being physically deformed, Monstrous Races go about either naked or at best, wearing a crude loincloth or animal skin. They eat strange things, such as raw meat, humans, rodents (as here), and each other. If they speak at all, they do so in cacophonous and incomprehensible ways.[31] The Crane Men of Herzog Ernst do not entirely fit this template because they wear luxurious clothing, they live in expensive and sophisticated dwellings embellished by tasteful furnishings, and they dine on dainty delicacies. Still, they do not speak but rather squawk loudly; no human can understand them. By interesting contrast, the heroic and cultured Duke Ernst is highly skilled in the languages and customs of foreign peoples (vv. 66-81). Although these skills are not very useful in Grippia, where he fails to learn the Crane Men’s language, they serve him well during his next monstrous encounter. It takes him only a year to master the fiendishly difficult language of the kindly One-Stars (vv. 4629-4631), whose king, out of gratitude for the Duke’s defense against the enemy Flat Hoofs, enfeoffs him with extensive lands (vv. 4762-4778).

A colored woodcut image from Anton Sorg’s c. 1477 Augsburg edition of Herzog Ernst provides some additional details about the Crane Men alongside a lengthy description of the major military clash between the Crane Men and Duke Ernst and his knights in the land of Grippia (vv. 3605-3883) (Figure 1).[32] It is notable that opponents wear the same type of short tunic, wield similar swords, and stand at the same height. In fact, the only sartorial differences between them are the helmets worn by the knights. At an earlier point in the narrative, Count Wetzel predicts that the vulnerability of the Crane Men’s long, thin necks will afford the Bavarians a strategic advantage (vv. 2990-2994). The artist has dramatized this weakness in an image that juxtaposes unprotected crane necks perilously close to very sharp swords. Indeed, over the body of one of the fallen, the foremost Bavarian grasps a Crane Man by his thin neck, his sword raised to deliver a decapitating blow. It is an image that calls to mind the conceptual rupture identified by Burns in French courtly narrative that occurs when armored knights become suddenly vulnerable once their armor is damaged and their skin is exposed.[33] Full body armor—an occluding and masculinizing ‘garment’—is not worn by the Crane Men, who instead show up for battle in flashy, bejewelled, silk and embroidered garments and carry ornamental bows, quivers, and shields, as we shall see presently. By contrast, the narrator repeatedly admires the manly shining mail, gleaming hauberks, and shining greaves worn by the Duke and his knights.[34] In the Augsburg image, however, the Crane Men do not fight with the bows and arrows the narrator claims they possess, and the only pieces of armor worn by the knights are rather unimpressive helmets that leave their faces exposed. Thus the artist has created far less of a disparity between opponents than the text would have us believe.

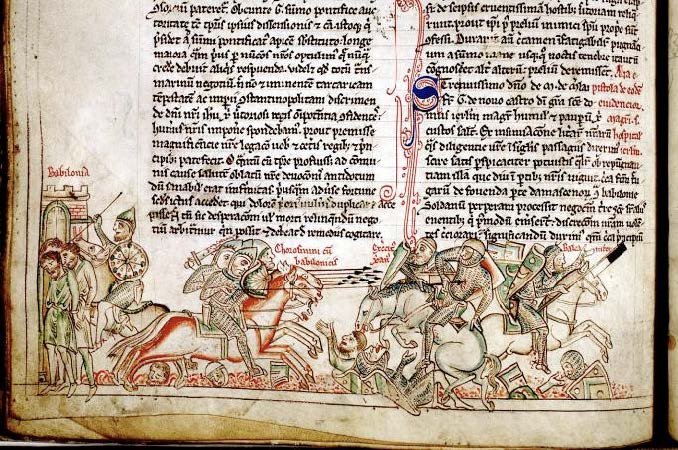

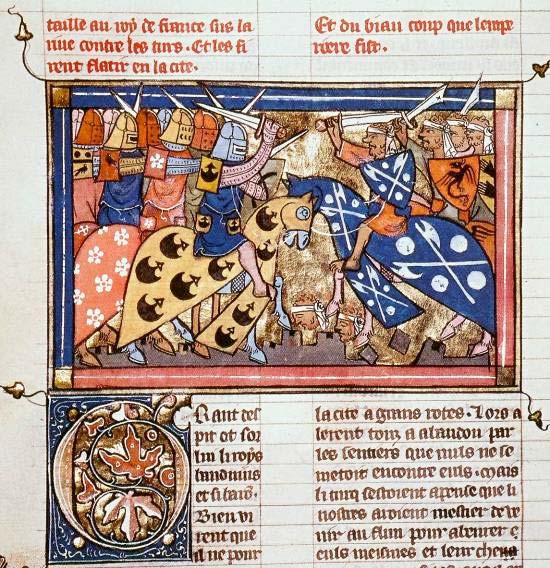

Such visual similarities between human and monstrous armies suggest well-matched adversaries, recalling the chansons de geste and other types of manuscript illuminations that feature ‘Saracens’—another exotic, enemy group— equipped with arms and armor on a par with those of their Western Christian opponents (Figure 5).[35] In this type of image, as also articulated in the chansons, armor obscures identity,[36] and sartorial resemblance signals the chivalric worthiness of non-Christian warriors. In the Augsburg woodcut, however, the Crane Men’s avian heads and necks unavoidably preserve their distinct identity, and for this reason, the image more closely recalls images of Christians versus Saracens that preserve their ‘pagan’ identity by employing visual stereotypes composed of distinctive costume, distorted physiognomy, dark skin, or some combination of these (Figure 6).[37] If we remember that the journey undertaken Land where they subsequently spend a year fighting against the ‘heathen,’ then the monstrous battle scenes emerge as episodes within a larger crusader narrative. Viewed from this perspective, monsters might have functioned for some courtly audiences as stand-ins for Saracens.[38] Indeed, boundaries sometimes blurred between Saracens and monsters in later medieval imagery in which clothing is crucial to identity. Examples include an image from a Parisian or Rouennais copy of the Romance of Alexander of Alexander the Great and his knights battling an army of Cyclopes in which the latter are rendered as one-eyed, giant, tortil-wearing Saracens (Figure 7), and the clothed Dogheads carved above the tympanum of the church of La Madeleine in Vézelay depicting Christ’s Mission to the Apostles that were gazed upon by the crucesignati of the Second and Third Crusades.[39] However justifiable a reading of the Herzog Ernst monsters as allegorical ‘Saracens’ might be in this particular context, though, it does not fully account for their multiple and seemingly mutually exclusive roles as adversaries, allies, friends, gifts, and courtiers.

Fig. 5. Battle between Crusaders and Khorezmians, Matthew Paris, Chronica majora, St Albans, ca 1240-53 and later, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, MS 16, fol. 170v (detail) (photograph by permission of the Master and Fellows of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge)

Fig. 6. French versus Saracens, William of Tyre, History of Outremer, Paris, c. 1337, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, MS fr. 22495, fol 154v (detail) (photograph by permission of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France)

Fig. 7. Alexander’s army versus the Cyclopes, Romance of Alexander, Paris or Rouen, c. 1425, London, British Library, MS Royal 20.B.xx, fol. 79v (detail) (© British Library Board, All Rights Reserved)

Reading through Monstrous Clothes

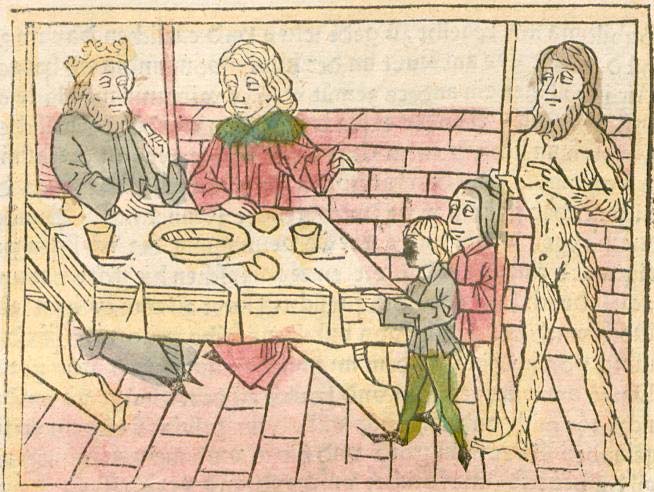

Fortunately, our understanding of the multiple meanings of the monsters is greatly aided in later copies of Herzog Ernst by the text’s accompanying pictorial imagery. Especially in view of the tale’s more positive monster-human relationships, I believe these meanings pertain not to the battlefield but rather to the court. A courtly encounter between the Duke, his monsters, and the King of Egypt (Babilonia) is captured in another image from the Augsburg blockbook (Figure 8). Here, Duke Ernst presents three members of his monstrous entourage. The image includes some significant details that transcend the accompanying narrative. As the central figure, Ernst, by now skilled in monstrous languages, functions as a mediator between king and monsters, and the figures’ pointing gestures indicate reciprocal social exchange. It is also notable that while the two smaller monsters (a Prechami and an Ears) wear Western courtly clothing, the Giant—who will go home with the Duke to Bavaria—appears au natural, his modesty preserved only by his extreme hairiness. This is especially interesting given that in another image, which depicts the arrival of the Giant emissary at the court of the Arimaspi (One-Star) king, the Giant wears full courtly garb, including even a stylish hat and soft leather shoes (Figure 9).[40] Such a dual depiction of monstrosity mirrors the dual narrative function of the monsters in this tale as both subjects and as objects.[41] They are subjects (or antagonists) when they fight against or make friends with Duke Ernst and his knights. But once the Duke takes possession of some of them, they become commodities—objects—that are gifted, first in Jerusalem and again in Germany. Like the sumptuous silks and ‘dressed-up women’ that Burns traces throughout medieval French romance, as commodities, the monsters may be traded or assimilated at court.

Fig. 8. Duke Ernst and his monsters at court, Herzog Ernst, Augsburg: Anton Sorg, c. 1477, Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek, Ink. H-296, fol. 32 (photograph by permission of the Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek)

Fig. 9. Giant emissary at the Arimaspi court, Herzog Ernst, Augsburg: Anton Sorg, c. 1477, Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek, Ink. H-296, fol. 33v (photograph by permission of the Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek)

It is to the exotic stuff that I finally turn. As the menu image attests (Figure 2), lack of clothing is an important, conventional iconographical indicator of the monsters’ barbarity, implying that clothing itself is a sign of civilization. More fundamentally, nakedness makes the monster: it is a sign of subhumanity because like beasts, monsters have no need for clothes.[42] Nevertheless, in Herzog Ernst, the monstrous Crane Men wear elaborate clothing and live in elegant dwellings. These are not just incidental, interesting details but rather the subjects of extended ekphrasis. Of the Crane Men’s city, we read:

Returning to the city, they discovered many lovely works of art made of fine gold and examined, one by one, all sort of wondrous things made from gold and precious stones. They saw stately palaces— beautiful, grand, and strangely formed—with arches and lofty doors which were more ornate than any others on earth and sparkled like stars. They saw splendid halls, and everything was planned, inside and out.[43]

Of the Crane Men’s palace:

After they had looked at these wonders, they went back to the park where they had eaten and, passing through it, saw a nearby palace which had a gold roof and skilfully fashioned emerald walls that gleamed bright green. In it Duke Ernst found a room which was gracefully decorated with jewels set in shining gold. They entered and saw a bed that—so we are told—was beautifully trimmed with gold and decorated with pearls arranged in squares and other precious stones in strange patterns. Lions, dragons, snakes, all skilfully wrought of gleaming gold, adorned the bedstead, and at the tops of the bedposts four large jewels shone like the sun and as if they were burning. They gleamed like a glowing fire, and Duke Ernst was pleased. On the bed were two quilts of fine and costly cloth, silk sheets, and an ermine counterpane which had an artfully stitched border of great value with many precious stones, and above it hung a canopy of glistening silk and gold fabric with an elegant, wide fringe. The two young knights thought the bed was wonderful.[44]

Of the Crane Men themselves:

Both young and old had well-formed hands and feet and were in every respect handsome, stately people, except that their necks and heads were like those of cranes. The watchers saw a large army of them walking and riding toward the city, armed only with shields, bows, and skilfully wrought quivers of deadly arrows. They wore clothing of satin and different kinds of fine silk which was decorated, according to each one’s taste, with silk and gold trimming. Save for their long necks, no fault could be found with their bodies, which, with both men and women, were strong and beautiful.[45]

And as noted earlier, the stylish Crane Men make an effort even when preparing for fierce battle against the Duke’s army, as described in a passage worth quoting at length:

[The Crane Men] wore fine tunics of a rare silk that were embroidered and trimmed with jewels and, over them, coats of another silk: the clothing made the men look quite handsome. Their leggings were slit in courtly style and heavily trimmed with gold thread through which the linen gleamed whiter than snow. They had on gold spurs. The two belonged to the highest rank below the king and were therefore allowed to walk in front of him, which they now did with stately and measured steps. Their necks were thin and long: indeed, from head to shoulders they were just like cranes. Each wore a splendid quiver of white ivory, lined with silk and trimmed around the edges with precious stones in costly settings, and carried a well-shaped horn bow, strung with silk and a golden shield, the boss of which was a huge garnet that—so the knights thought—could not have sparkled more brightly. After the first two, they saw another pair following, who wore silk and the best satin in the world, daintily sewn with shining gold thread and gracefully ornamented down to the legs with many pearls which gleamed in a truly splendid manner. They had bows and quivers of great value and gold-studded shields too elegant to describe, as were the lovely ornaments they wore. The knights thought their appearance and manner very praiseworthy, although they were also like cranes.[46])

Given the dazzling imagery such verbal color conjures, to return to the battle image that accompanies it in the Augsburg blockbook is aesthetically disappointing, especially since this is the only image of the Crane Men in the entire Augsburg pictorial series (Figure 1). A clue to this contradictory artistic response might well lie in the last phrase of this last quoted passage (“…although they were also like cranes”) as well as one of the first in the previous one (“…except their heads and necks were like those of cranes”). Cognizant of their rich clothing and accessories, such phraseology implies that even the most glamorous getup cannot mollify monstrosity. The images similarly maintain a focus on the human-monster encounters whose cultural significance transcends the superficial delight of sartorial finery. Most importantly, both text and image make no clear distinction between East and West. In Herzog Ernst, Eastern exoticism is located not only in the Crane Men’s fine clothing—made of sumptuous Eastern materials like garments worn in the West—but also in the monsters themselves: “sartorial bodies” are monstrous bodies. Even if we observe that the clothing as described in both text and image is decidedly Western in style, as Burns has observed, Western courtly clothing is itself comprised of stuff from the East, which disrupts any strict dichotomy that might be drawn between the wearers and the origins of their clothing.[47]

Clothing forecasts the court in a rather different way in a final image from the Augsburg blockbook, which depicts Duke Ernst and his men arriving in Prechami, the city of the little people identified in the accompanying text as the Pygmies (Pigmennen) (Figure 10). It should be recalled that the Prechamis are defended by the Duke against their enemies, the cranes (wicked birds not to be confused with the Crane Men), with whom they were locked in perpetual gerantomachy (vv. 4896-4927).[48] In the image, we see the arrival of Duke Ernst and his knights at the city gates where they first encounter three Pygmies. Like the Crane Men, the Pygmies wear courtly costumes, including foppish hats and fashionably pointy shoes, even though, unlike that of the Crane Men, their garb is not mentioned in the text. And so in the image, clothed Pygmy bodies point beyond the immediate narrative to the popularity of dwarfs as contemporary courtly amusements.[49] Dwarfs in courtly dress visually collapse the distinction between monsters and courtiers, forecasting the milieu that some of the Prechamis will soon occupy and thus claiming a place for monstrosity in the Western court, both literally and conceptually. Once again, the boundaries between East and West blur in an image that disrupts the conventional medieval narrative of Western knights bravely confronting strange creatures who never stray beyond the confines of their exotic Eastern homelands.

Fig. 10. Duke Ernst and his knights encounter the Pygmies, Herzog Ernst, Augsburg: Anton Sorg, c. 1477, Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek, Ink. H-296, fol. 27 (photograph by permission of the Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek)

Conclusion: Bringing the Monsters Home

Near the end of the tale, after performing his tour of Christian duty in the Holy Land, Duke Ernst returns to Bavaria to seek Emperor Otto’s pardon and to present to him his monsters. As noted earlier, the emperor is so fascinated with the strange creatures that he asks if he might keep a few of them, and so Ernst gifts to him an Ears, a One-Star, and a Prechami. But he refuses to part with the others, especially the Giant, whom he will entrust to no one else (vv. 5982-5993). I suggest that this is a pivotal narrative moment because it disrupts the conventional East-West dichotomy normally upheld in monstrous tales by confining dangerous, enemy monsters faraway and Elsewhere (India, Scythia, Ethiopia, the Far North). Unlike the Hereford Map, which in accordance with authoritative written traditions keeps the Monstrous Races out of Europa,[50] including Germania, Duke Ernst collects monsters from the East and brings them back home to Germany where they are warmly received by the Christian emperor.

In more theoretically driven analyses, the monsters of Herzog Ernst have been viewed persuasively as a form of cultural expression and as signs of cultural hybridity.[51] This brief investigation reaches similar conclusions, but via a different analytical route that takes account of the clothing and oriental sumptuosity that the Duke and his knights encounter in addition to the monsters themselves. Throughout the tale, clothing and monsters work together to westernize the orientals and to orientalize the westerners, calling to mind Burns’ discussion of ‘geographic hybridity’ in the French courtly love narratives, which acknowledges the extent to which Western elite identity depends upon Eastern opulence.[52] Likewise, in Herzog Ernst, the Duke repeatedly confronts exotic eastern ‘Others,’ some of whom be brings back to the western court, where they help to shape that very court. Thus, Herzog Ernst traces the process of formulating courtly identity, and the ‘sartorial bodies’ by which we may map this process are monstrous ones. The Grippia combat episode demonstrates that in medieval romance, not only love, but also war can be structured by evocations of lavish goods that in reality moved from East to West through mercantile exchange and crusading plunder, both of which operate in the off-stage thought world of Herzog Ernst.[53]

The story of Herzog Ernst also demonstrates that monsters, so often signifiers of Otherness or of cultural conflict, can serve still other purposes. Precisely because they are monsters, they can disrupt the very conventions they uphold elsewhere in medieval art and literature. If we allow that luxurious clothing and monsters in Herzog Ernst are interdependent cultural signifiers, new questions might include: To what extent do pictorial representations and verbal descriptions of sumptuous clothing “extend the flesh of the monsters symbolically and ideologically,” to paraphrase Burns?[54] Or: How do monsters, as transferable exotic goods, function as cultural crossing places for East and West?

Besides identifying cultural syntheses of East and West, another major goal of Burns’ analytical method is to clarify how narrative evocation of clothing and other luxury stuffs might either reinforce or destabilize contemporary notions of gender. Although not pursued in the present study, this problem merits further investigation, perhaps beginning with the question: Does sumptuous garb in Herzog Ernst, such as that worn by the Crane Men during battle, carry chivalric connotations of effeminacy that might in turn signal the ‘rightful’ subordination of East to West? As Rasma Lazda-Cazers has shown, issues of gender are of clear relevance to the extensive narrative episode of the rescue of the Indian princess from the clutches of the (sumptuously dressed) Crane Men King (vv. 3095-3576), as well as to the numerous descriptions of cities that comprise the tale’s overall spatial framework. The significance of the clothing and physical beauty of Empress Adelheid should also be considered in relation to her role as mediator between her son, Ernst, and her husband, Otto, that is emphasized at the tale’s beginning (when she fails to reconcile them) and end (when she succeeds).

Finally, Burns’ method of ‘reading through clothes,’ when applied to the monsters of Herzog Ernst, requires a marked shift of focus from French to German medieval history, and from the subject of courtly love to that of courtly conflict and its resolution. The utility of this approach must be measured against other historical, philological, and comparative literary data, and must take into account other aspects of the tale not addressed here, a project I leave to the literary critics. As an art historian, I have been especially concerned with the text’s visual potential, alive in the text’s florid ekphrasis and realized from different perspectives in accompanying imagery that expands and enhances the reader’s experience of this complex and fascinating tale.

References

| ↑1 | The seminal study with critical editions of the different text versions is Karl Bartsch, Herzog Ernst (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1869). Unless otherwise noted, line designations and quotations are from Bartsch’s edition of Herzog Ernst B (pp. 15-125); English prose translations of this same edition are from J. W. Thomas and Carolyn Dussère, The Legend of Duke Ernst (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1979). On boundary-transgression as a defining characteristic of the monstrous, see Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, “Monster Culture (Seven Theses)” in Monster Theory: Reading Culture, ed. Jeffrey Jerome Cohen (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996), 12-16. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | On monstrous themes across this literature, see Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Of Giants: Sex, Monsters and the Middle Ages (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999). |

| ↑3 | On the Monstrous Races tradition, see the classic study by John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1981). See also Claude Lecouteux, Les monstres dans la literature allemande du moyen age: contribution à la étude du merveilleux médiévale, 3 vols. (Göppingen: Kümmerle, 1982). |

| ↑4 | See especially three studies by Claude Lecouteux: “Herzog Ernst, les monstres dits ‘Sciapodes’ et le problème des sources,” Études germaniques 34 (1979): 1-21; “A propos d’un episode de Herzog Ernst: La recontre des hommes-grues,” Études germaniques 33 (1977): 1-15; and “Die Kranichschnäbler der Herzog Ernst-Dichtung: eine mögliche Quelle,” Euphorion 75 (1981): 100-102. |

| ↑5 | See especially Albrecht Classen, “Multiculturalism in the German Middle Ages? The Rediscovery of a Modern Concept in the Past: The Case of Herzog Ernst,” in Multiculturalism and Representation: Selected Essays, ed. John Reider and Larry E. Smith (Honolulu: College of Languages, Linguistics, and Literature, University of Hawaii and the East-West Center, 1996), 198-219; Elizabeth A. Andersen, “Time as a Compositional Element in Herzog Ernst (B),”in ‘Vir ingenio mirandus’: Studies Presented to John L. Flood, ed. William J. Jones, et al. (Göppingen: Kümmerle, 2003), 3-22; Stephen Mark Carey, “‘Undr unkunder diet’: Monstrous Counsel in Herzog Ernst B,” Daphnis 33 (2004): 53-77. https://doi.org/10.1163/18796583-90000900; and Rasma Lazda- Cazers, “Hybridity and Liminality in Herzog Ernst B,” Daphnis 33 (2004): 79-96. https://doi.org/10.1163/18796583-90000901 |

| ↑6 | For an overview of this literature, see Carey, “Undr unkunder diet,” 53-54. |

| ↑7 | As Stephen Mark Carey (“Undr unkunder diet,” 55) has observed, “The historical resiliency of Herzog Ernst lies in its capacity to serve as a platform for negotiating variant historical identities in the elasticity of monstrous representation.” On post-medieval literature and film based on the tale, see Thomas and Dussère, Legend of Duke Ernst, 36-52; and Carey, p. 54, n. 3. |

| ↑8 | E. Jane Burns, Courtly Love Undressed: Reading Through Clothes in Medieval French Culture (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002). |

| ↑9 | As outlined in Courtly Love Undressed, 1-16. Burns has continued her analysis of the signifying power of textiles with Sea of Silk: A Textile Geography of Women’s Work in Medieval French Literature (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009) which examines the ways in which textiles functioned as cross-cultural links. For a series of shorter studies that also pursue this theme, see Medieval Fabrications: Dress, Textiles, Cloth Work, and Other Cultural Imaginings, ed. E. Jane Burns (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). In press at the time of this writing is Monica L. Wright, Weaving Narrative: Clothing in Twelfth-Century French Romance (University Park: Penn State University Press, forthcoming 2010). |

| ↑10 | Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 12-13, 209-210. |

| ↑11 | Bartsch (as above, n. 1) identifies three complete pictorial cycles, all represented by fifteenth-century incunables in the Mainz Stadtbibliothek: Inkunabel 322 (with uncolored woodcuts) Inkunabel s.a. 665 (with colored woodcuts) and Inkunabel s.a. 666 (with colored woodcuts). Copies of the Augsburg edition with colored woodcuts on which the present study focuses are also housed in Munich (see below, n. 32 and Figures 1, 8, 9, 10) and the British Library (IB.5832). Incomplete copies and fragments are also housed in the Staats- und Stadtsbibliothek Augsburg (1 imperfect, 1 fragment), the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg (imperfect), the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (3 imperfect), and the Russian State Library in Moscow. Two manuscript copies contain but single illustrations: Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Mgo 225 (2d q., 13th-c.) and The Dresdener Heldenbuch of 1472 (Dresden, Landesbibliothek, Mscr. M 201, ff. 265-275v). |

| ↑12 | Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 2. |

| ↑13 | I have attempted to fill a similar analytical gap for Marco Polo’s book in Debra Higgs Strickland, “Artists, Audience, and Ambivalence in Marco Polo’s Divisament dou monde,” Viator 36 (2005): 493-529. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.300020 |

| ↑14 | Anne Hollander, Seeing Through Clothes (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), xi-xvi. Burns explicitly differentiates her project from Hollander’s (Courtly Love Undressed, 35 and 242, n. 39). |

| ↑15 | See the art historical analyses in Encountering Medieval Textiles and Dress: Objects, Texts, Images, ed. Désirée G. Koslin and Janet E. Snyder (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002). Margaret Scott, Medieval Dress & Fashion (London: British Library, 2007) provides an excellent survey of medieval court costume based on contemporary manuscript illumination that contains a very useful glossary of costume terms. |

| ↑16 | On the history and dating of the text redactions according to their extant witnesses from the twelfth through the sixteenth centuries, see Bartsch, Herzog Ernst, I-CLXXII. On Herzog Ernst B, see also Herzog Ernst: Die älteste Überarbeitung des niederrheinischen Gedichtes, ed. Berhard Sowinksi (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1970). |

| ↑17 | While the text repeatedly notes the physical resemblance of these men to cranes (see below), it does not contain a German compound precisely equivalent to ‘Crane Men’ but rather refers to these creatures in relation to their homeland, Grippia (‘Grippians,’ ‘men of Grippia,’ ‘king of Grippia’). ‘Crane Men’ or ‘Crane Heads’ are therefore modern appellations, the latter one likely inspired by the Cynocephali (Dogheads). |

| ↑18 | By ‘monster rules,’ I have in mind Cohen’s principles of monstrosity (“Monster Culture”). |

| ↑19 | Like the Crane Men, the specific term, ‘Pygmy’ does not appear in Herzog Ernst B— ‘little people’ is the usual term of reference—, although Pigmennen is used in the Volksbuch text (Herzog Ernst F) that accompanies the woodcuts discussed in this essay (see below). The Volksbuch text generally supplies other common Latin terms for the monsters described, such as Cyclopes for the One-Stars of Arimaspi. |

| ↑20 | On the rich history of Giants, beginning with the biblical tradition, see Walter Stephens, Giants in Those Days: Folklore, Ancient History, and Nationalism (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1989). See also Cohen, Of Giants. |

| ↑21 | London, British Library, MS Harley 2799, fol. 243r. This is the second of a two-volume bible which includes the psalms in three versions and some additional diagrams. See the British Library catalogue entry: http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/record.asp?MSID=7862&CollID=8&NStart=2799 (accessed 30 December 2009). |

| ↑22 | On the relationship of the Gesta romanorum moralizations and the monsters of Herzog Ernst, see Alexandra Stein, “Die Wundervolker des Herzog Ernst (B): zum Problem körpergebundener Authentizität im Medium der Schrift,” in Fremdes wahrnehmen – fremdes Wahrhemen, ed. Wolfgang Harms, C. Stephen Jaeger, and Alexandra Stein (Stuttgart: S. Hirzel, 1997), 40-47 (with the most extensive analysis of the monsters); and Carey, “Undr unkunder diet,” 71-72, 77. On other sources for the Crane Men, see Lecouteux: “La recontre des hommes-grues”; and “Die Kranischschnäbler.” |

| ↑23 | On the Hereford map, which has a large literature, see especially The Hereford World Map: Medieval World Maps and Their Context, ed. P. D. A. Harvey (London: British Library, 2006). On the Hereford map monsters, see Naomi Kline, Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2001), 144-64. |

| ↑24 | The legend directly above the figure, however, reads ciccone gentes and since the Latin word, ciconia, means ‘stork,’ the figure might represents a Stork Man rather than a Crane Man, although I am unaware of Stork Men as a discrete monstrous type. In his magisterial study and translation of the Hereford Map legends, Scott Westrem is equivocal on this point but does allow for the possibility that the figure represents a Crane Man. See Scott Westrem, The Hereford Map (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 74, entry no. 155. Naomi Kline (Maps of Medieval Thought, 44) skirts the issue by translating the legend as “the Ciccone people,” which is unsatisfying because it occludes their monstrosity. |

| ↑25 | Besides the Crane Man, these include the giant-eared Panotii (Phanesii) isolated on a northeast island in Ocean, a one-footed Sciopod (Monoculi) located beside the Ganges River near the very top of map; and a group of Pygmies just south of the Sciopod. Other monsters that exhibit physical features similar to the Herzog Ernst monstrosities include the swan-footed Tigolopes (akin to the swan-footed Flat Hoofs), and a one-eyed king holding a sceptre, just below the Nile, identified in the accompanying legend as an Agriophagi Ethiopian (akin to the one-eyed Arimaspi). For further discussion of the Hereford legends and their sources, see the individual entries in Westrem, Hereford Map. In light of a riveting episode in Herzog Ernst involving a narrow escape by Duke Ernst and his knights from a man-eating griffin, the rendering on the Hereford map of the Arimaspi (Carimaspi) as a trio of one-eyed knights wearing contemporary armor and battling a large griffin is particularly interesting. |

| ↑26 | New Haven, Beinecke Library, MS 404, fol. 113r: “In damasco errant diuerse herbe de natura speciali adam dixit ad filias suas, ‘Si comederitis de illa herba fructum concipietis qui inferius erit similes homini et superius habebit collum gruis et caput gruis.’” (In Damascus there used to be various plants with special properties, about which Adam said to his daughters, “If you eat of that plant, you will conceive an offspring that in its lower parts will be like a man and in its upper part will have the neck of a crane and the head of a crane”). See the Beinecke Library catalogue entry with link to digitized images: http://130.132.81.132/pre1600ms/docs/pre1600.ms404.htm (accessed 31 December 2009). On the Crane Men and the other monsters in the Rothschild Canticles, see David Blamires, Herzog Ernst and the Otherworld Voyage: A Comparative Study (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1979), 30-33. |

| ↑27 | On the German connections, see Jeffrey Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), esp. 211-12. More recently, arguments for a Low Countries place of production have been put forward; see Wybren Scheepsma, “Filling the Blanks: A Middle Dutch Dionysius Quotation and the Origins of the Rothschild Canticles,” Medium Aevum 70 (2001): 278-303. The juxtaposition of the Crane Man with the Doghead on folio 113r might reinforce the argument of a relationship between the two types of monsters put forward first by Lecouteux, “Die Kranichschnaebler,” and later by Carey, “Undr unkunder diet,” 70-72. https://doi.org/10.2307/43632680 |

| ↑28 | See The Nuremberg Chronicle: A Facsimile of Hartmann Schedel’s Buch der Chroniken Printed by Anton Koberger in 1493 (New York: Landmark Press, n.d.), fol. 12r. A larger group of Monstrous Races is depicted on the preceding folio (11v). See the Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek (Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum Digitale Bibliothek) electronic facsimile: http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0003/bsb00034024/images/index (accessed 31 December 2009). |

| ↑29 | See the electronic facsimile available on the Biblioteca Digitale dell’Università di Bologna website: http://amshistorica.cib.unibo.it/diglib.php?inv=127&term_ptnum=1&format=jpg&x=4&y=7 (accessed 31 December 2009). |

| ↑30 | Friedman, Monstrous Races, 31-32. |

| ↑31 | On these and other monstrous traits, see Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, Demons, and Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 42-46. |

| ↑32 | Heinach volgt ain hüpsche liepliche historie ains edeln fürsten herczog Ernst von bairn vnd von osterich (Munich, Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek, Ink. H-296); also available in electronic facsimile via the Bayerisches Staatsbibliothek website: http://mdzx.bib-bvb.de/bsbink/Ausgabe_H-296.html (accessed 30 December 2009). See also the printed facsimile of the uncolored woodcut edition: Ain hüpische liepliche historie ains edeln fürsten herzog Ernst von bairn und von osterich: Facksimiledruck nach der Originalausgabe von Anton Sorg, Augsburg um 1476, ed. Elizabeth Geck (Wiesbaden: Pressler, 1969). The text has been identified as Herzog Ernst F (also known as the Volksbuch), which is a c. 1450-1500 German prose version closely related to Herzog Ernst B. For a critical edition, see Bartsch, Herzog Ernst, 227-308. |

| ↑33 | Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 135-48. |

| ↑34 | Herzog Ernst, v.v 1453-1457 (trans. Thomas and Dussère, 78); vv. 2292-2294, 2338-2339 (trans. Thomas and Dussère, 87); vv. 4570-4576 (trans. Thomas and Dussère, 110). Interestingly, an absence of armor and the certain defeat this portends is also noted of the ‘heathens’ defeated by Duke Ernst and his knights in the Holy Land (vv. 5562-5564). |

| ↑35 | For numerous examples of such imagery, see Rita Lejeune and Jacques Steinnon, La Légende de Roland dans l’art du Moyen Age, 2 vols. (Brussels: Arcade, 1966). |

| ↑36 | Lucy C. Whiteley, “Touching the Hero: Bodies, Boundaries and Blood in the Old French Cycle des Narbonnais,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Glasgow, 2009), 47-48. In her analysis of chivalric arms and armor, Whiteley incorporates Burns’ sartorial theory (pp. 40-41). https://doi.org/10.1097/MPG.0b013e31816f214a |

| ↑37 | For discussion of grotesque Saracen stereotypes, see Strickland, Saracens, Demons, and Jews, 173-92. |

| ↑38 | If so, this might provide an explanation for the problem posed by Elizabeth Andersen (“Time as a Compositional Element,” 19) that the tale’s exotic elements distract from the purported aim of fighting against the Saracens in the Holy Land. On the sartorial functions of skin, see Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 121-48. |

| ↑39 | On these images, see Strickland, Saracens, Demons, and Jews, 184-86 and 159. |

| ↑40 | It is interesting to observe in this image that the Arimaspi king, a One-Star Cyclopes, is rendered as a two-eyed, conventionally dressed and crowned Western king. Compare this rendering to the one-eyed Agriophagi Ethiopian king on the Hereford map (as above, n. 25). |

| ↑41 | As observed of women in Old French epic by Burns (Courtly Love Undressed, 186) with reference to Sarah Kay, The Chansons de geste in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 25-48. |

| ↑42 | Various aspects of nudity—both monstrous and human—are explored in the essays in Naked before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Benjamin J. Withers and Jonathan Wilcox (Morgantown: University of West Virginia Press, 2003). |

| ↑43 | Dô sie wider kâmen gegân, / dô fundens in der bürge stân / manic were hêrlich, / von golde harte zierlich. / vil maniger handle wunder / sâhen sie besunder / von golde und von gesteine. / manigen palas reine / sâhen sie dar inne stân / schœne unde wol getân, / vil gar wunderlîch geworht. / ouch sâhn die helde unervorht / manic gewelbe und hôhe tür, / die lûhten sam die sternen vür, / die niender ûf der erden / baz gezieret mohten werden. / beide ûzen und innen / von meisterlîchen sinnen / was sie gebûwen über al. (Herzog Ernst, vv. 2531-2549; trans. Thomas and Dussère, 89-90). See also vv. 2212-2245 (trans. Thomas and Dussère, 86). Lazda-Cazers constructs an explicitly gendered reading of the cities in Herzog Ernst in “Hybridity and Liminality.” |

| ↑44 | Dô sie daz wunder dô gesâhen, / dô begundens dannen gâhen. / wider zer würmelâge se kâmen / dâ sie die spîse ê dâ nâmen. / dâ vür begunden sie dô gân. / dô sâhens dâ bî nâhe stân / ein vil rîchez palas / daz mit golde wol bedecked was, / von smâragde sîne wende, / wol gemacht in allem ende, / durchliuhtic grüene. / do gesach der vil küene / Ernest der vil werde man / ein kemenâten wol getân : / diu was gezieret innen / von meisterlîchen sinnen / von edelem gesteine. / die wâren algemeine / in liehtem golde schône erhaben / und meisterlîche wol ergraben. / dô sie dar în begunden gân, / ein spanbette sie sâhen stân, / als wir daz mære hœren sagen, / daz was mit golde wol durchslagen / beide schône und rîche, / und was vil meisterlîche / mit berlîn gefieret / und mit steinen wol gezieret / von vil fremden sachen. / lewen unde trachen, / nâtern unde slangen, / die lâgen an den spangen / geworht von golde, daz was lieht. / sie wâren des versûmet nieht / sin wærn geworht mit vollen. / oben ûf den vier stolen / lâgen vier edele steine. / die wâren nicht ze kleine. / die gelîchten wol der sunnen / und lûhten sam sie brunnen. / sie gla sten als ein glüendiu gluot. / des fröwete sich der helt guot, / Ernst der recke vil gemeit. / zwei bette wâren drûf geleit, / mit rîchem pheller wol bezogen, / an hôher kost vil unbetrogen. / diu lînlachen [wâren] sîdîn, / ein deckelachen hermîn, / dar umbe ein lîste wol genât, / die man in hôher koste hât, / von edeln gesteine manicvalt. / dar obe ein sîdîn blîalt, / mit guotem golde wol durchslagen, / liehte sîden drîn getragen, / ein lîste wît unde rich. / daz dûhte michel wunderlîch / die zwêne jungelinge. (Herzog Ernst, vv. 2557-2613; trans. Thomas and Dussère, 90). |

| ↑45 | die wâren an ir lîben, / sie wæren junc oder alt, / schœne unde wol gestalt / an füezen und an henden / und in allen enden / schœne liute und hêrlîch, / wan hals und houbet was gelîch / als den kranichen getân. / der sâhens rîten unde gân / gein der bürge ein michel her. / die fuorten kein ander wer / wan ir schilt unde bogen / unde kocher wol gezogen, / dar inne strâle freislîch. / das truoc umbe ir ieclîch. / rîche phelle und samît, / sumlîche von timît, / dar nâch als ieclîch wolde, / von sîden und von golde / was gezieret ir gewant./ an ir lîbe nieman vant / zer werlt deheiner slahte kranc, / wan daz in die helse wâren lanc, / ritterlîch übr al den lîp. / beide man unde wîp / wâren alle also gestalt. / sie fuorten kraft und gewalt. (Herzog Ernst, vv. 2852-2878; trans. Thomas and Dussière, 92-93). |

| ↑46 | die sâhen sie tragen an / zwei vil rîcher hemde / von sîden vil fremde / wol durchleit und genât. / zwêne rocke tribelât / die herren truogen dar obe. / die kleider stuonden wol ze lobe. / ir beider hosen ûz gesniten, / zerhouwen wol nâch hübeschen si-[ten. / dar über manic goltdrât. / dâ durch schein diu lînwât / wîzer danne kein snê. / in wârn dar über gespannen ê / zwêne guldîne sporn. / die zwêne wâren erkorn / ze den besten nâch dem künige hie. / dar umbe man sie vor im gên lie. / schœne und hêrlich was ir ganc, / ir helse small unde lanc, / gelîch den kranichen gevar / von dem houpte unz ûf den lîp gar. / dar zuo truoc ir ieclîch / einen kocher hêrlich / von wîzen helfenbeine, / mit edelem gesteine, / al umbe an den orten / gevazt mit guoten borten, / mit pheller wol underzogen. / iechlîcher truoc einen bogen / wol geworht hürnin. / diu senewe was sîdîn, / ir schilt von golde wol getân. / dâ diu buckel solde stân, / dâ stuont ein grôzer almâtin, / der niht liehter mohte sîn : / des die recken beide jâhen. / nâch den zwein sie komen sâhen / zwên ander in der selben zît. / die truogen den besten samît / der in der werlt mohte sîn. / ir kleider wâren sîdîn / diu si an ir lîbe hâten. / mit liehten goltdrâten / was er genât vil spæhe, / mit berlîn vil wæhe / geworht hin nider an diu bein. / dâ von vil hêrlîchen schein / manic edel stein vür unbetrogen. / ir beider kocher und ir bogen / die wâren tiure genuoc. / ietweder einen schilt truoc, / der was mit golde alsô beslagen / daz iu daz nieman kan gesagen / ze gelouben mit fuogen / daz si an und umbe truogen, / wie wol daz gezieret wære. / ir zuht und ir gebære / die herren dûht vil lobelîch. / sie wâren kranichen ouch gelîch. (Herzog Ernst, vv. 2998- 3056; trans. Thomas and Dussière, 94 |

| ↑47 | Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 185. |

| ↑48 | Medievals inherited the story of the gerantomachy from classical traditions. See Veronica Dasen, “Pygmaioi,” Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae 7/1 (1994): 594-601 (text); 7/2 (1994): 466-86 (plates). |

| ↑49 | See Clemens Amelunxen, Of Fools at Court, trans. Rhodes Barratt (Berlin: Walter de Guyter, 1992); and Beatrice K. Otto, Fools are Everywhere: The Court Jester Around the World (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), with extensive bibliography. On the signifying power of the figure of the Pygmy, see also the article by Suzanne Lewis in this volume. |

| ↑50 | I refer here to the land masses represented in the lower left (i.e., northwest) quadrant of the Hereford Map: it has long been observed that the land mass representing Europe is erroneously inscribed AFFRICA and concomitantly, that of Africa is erroneously inscribed EUROPA. |

| ↑51 | In her analysis of Herzog Ernst, Lazda-Cazers (“Hibridity and Liminality,” 87-88) adopts the definition of hybridity developed by Homi K. Bhabda in Location of Culture (New York: Routledge, 1994), while Burns (Courtly Love Undressed, 197) follows Robert C. J. Young, who characterizes hybridity as “the seemingly impossible simultaneity of sameness and difference” in Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture, and Race (New York: Routledge, 1995, 26). I believe Young’s definition is especially apposite in relation to the Herzog Ernst monsters. On cultural hybridity and its relationship to monstrosity, see also Asa Simon Mittmann, “The Other Close at Hand: Gerald of Wales and the ‘Marvels of the West’ in The Monstrous Middle Ages, ed. Bettina Bildhauer and Robert Mills (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2004), 97-112; and Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, Hybridity, Identity, and Monstrosity in Medieval Britain: On Difficult Middles (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). |

| ↑52 | Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 11. |

| ↑53 | For an overview of issues relevant to the tale’s contemporary German readership, see Michael Postan, “The Trade of Medieval Europe: The North,” The Cambridge Economic History of Europe, vol. 2, Trade and Industry in the Middle Ages, ed. M. M. Postan and Edward Miller, 2d ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 168-305. On the complexities of Eastern-Western commercial exchange, see also Sharon Kinoshita, “Almería Silk and the French Feudal Imaginary: Toward a ‘Material’ History of the Medieval Mediterranean,” in Medieval Fabrications, 165-76. https://doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521087094.006 |

| ↑54 | Burns, Courtly Love Undressed, 13. |