Donna L. Sadler • Agnes Scott College

Recommended citation: Donna L. Sadler, “The Nun’s Cell as Mirror, Memoir, and Metaphor in Conventual Art,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/KTDR4136.

Introduction

Between the eighteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century, nuns belonging to numerous orders, including the Cistercians, Carmelites, Carthusians, Poor Clares, Ursulines, Visitandines, Augustinians, and others throughout the east of France (namely Burgundy, the Rhone Valley, and Provence), Switzerland, Swabia, Spain, and Bavaria created models of the cells in which they prayed and slept.

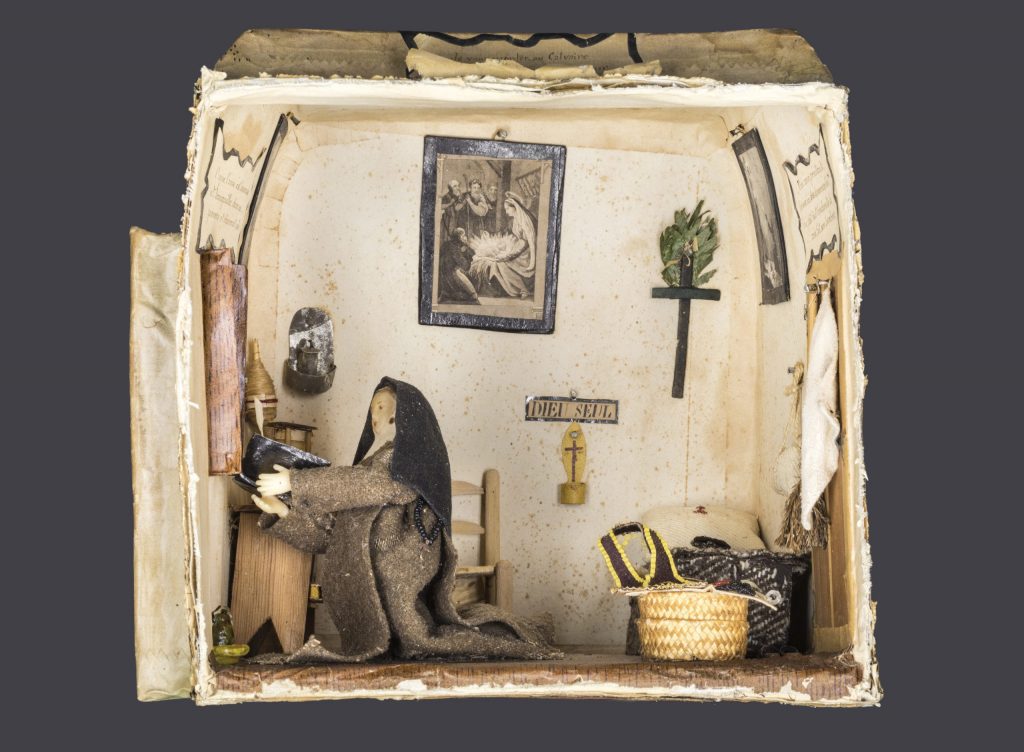

Figure 1. Vaulted Capuchin Cell from Provence, late 18th century-early 19th century, Made of breadcrumbs (Mie de pain), fabric, paper, vegetal fiber, glass, and wood. 25 x 23 x 22 cm. Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

Miniature in scale, a doll in the guise of a nun is found enacting a scene from her life: praying, reading her breviary, weaving, making a bouquet, or preparing to mortify her flesh. The nuns’ cells were either given to the families of the professed nuns as a souvenir of their monastic life, in gratitude to a wealthy benefactor, or created to commemorate a special occasion celebrated by the convent such as a jubilee.[1]

If one peers into one of these cells, say that of Sister Adélaïde, a Tertiary nun of the Franciscan order, one finds an abundance of enticing and revealing details.

Figure 2. Cell of Sister Adélaïde, a Tertiary nun of the Franciscan order, 19th century, Made of wood, fabric, paper, cardboard, vegetal fiber, wax, metal, and glass. 30.5 x 34.5 x 22.5 cm. Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

Seated in the center of the back wall, the wooden figure of Adélaïde glances up from the book she is reading to meet the viewer’s gaze. Before her feet rests a small heater beyond which is her footrest; both the window and the bed are dressed in white curtains and her bureau holds a faience cup, a sand timer, and three large books. The fine decor of her cell betrays Adélaïde’s economic status. Above the nun an inscription states “St. Adélaïde de St. Joseph/ Qu-étes vous venue/ faire ici en religion.”[2] The Crucifix also bears a moral etiquette: “Voila mon/ unique science.”[3] An additional inscription is found beside her writing implement that identifies the nun as “Madame veuve Gosset/ née B…rs/ Montoison.” The left wall of her cell is punctuated by a spinning wheel and distaff, behind which is placed a water basin with its pitcher. Her basket filled with spare wool and a work in progress fills the space between the artefacts to the left and the heater and footstool to the right. The elaborate bouquet of artificial flowers on her bed suggests that Adélaïde’s manual labor may have been the fabrication of flowers for the monastery.[4] Finally, the sandals at the foot of the bed complete this homey cell. The constellation of objects in Adélaïde’s cell creates a warmth that offers a compelling invitation to linger in this nun’s private space.

The miniature size of the nuns’ cells belies their powerful presence. The careful rendering of material props and the humble bedding capture the attention and imaginary potential each nun saw in the objects that filled her cell. The owners of cabinets of curiosities in the seventeenth century attached personal significance to each of the objects they collected; the miniatures on the shelves were signifiers of the self and formed an illustration of the owner’s life.[5] In the case of a dollhouse, another species of the miniature, the identity of the owner shifted to the doll. The model of the nun’s cell behaves in a fashion similar to that of a dollhouse, in that both objects offer the viewer the interior of the interior.[6] Indeed, European dollhouses traced their origins to the medieval crèche, where the sacred was situated within the secular landscape.[7] It is interesting to note that the objective of the earliest dollhouses from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was didactic.[8] A child could learn how to navigate a kitchen from the miniature equipment, as well as garner knowledge from the maps, globes, drawings, paintings, bas-reliefs, sculptures, and finely made clocks found in dollhouses. The 300 miniature books in the library of Queen Mary’s dollhouse were legible and intended for her royal edification.

In the nuns’ cells, the wooden, wax, papier-mâché, or porcelain effigy of the nun is the protagonist of the sacrosanct space in which she is found.

Figure 3. Carmelite Cell from Burgundy, 18th century, Made of wax, fabric, paper, cardboard, glass, and wood. 31.5 x 31.5 x 30 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

Is this not a type of self-portraiture hewn out of faith and devotion to Christ and the Virgin? At the same time, the cells constitute a mirror of the collective community. Though private in nature, the cell embodied the nun’s corporate identity. As the locus for her communion with God, the space was permeated by an aura of sanctity, yet populated with completely mundane objects, such as books, candles, and wooden slippers.

This article will take the nuns’ cells as the starting point of the narrative, considering the ways in which they expressed the values of the monastic community, the role of the individual within that community, and the intersection of private and public space in convent life. We will then consider how the models of these cells embodied an idealized experience of interiority, for their miniature scale delimits the space they occupy, but transcends temporal boundaries by capturing both a moment in time and the flux of all time.[9] As Susan Stewart and others have noted, a reduction in scale does not correspond to a diminution in significance;[10] indeed, the miniature becomes more itself, conferring on the maker and the beholder a sense of possession, compensating for the renunciation of sensible dimensions with the acquisition of intelligible dimensions.[11]

Approach to the Cells

The early modern date of the majority of the miniature cells renders their precise architectural context elusive. The contours of the monastery shifted considerably after the Middle Ages, undergoing first the reform movements of the fifteenth century, the Counter-Reformation and the Council of Trent’s enforcement of claustration, followed by the havoc wreaked by the French Revolution, and the subsequent restoration of the monastic communities.[12] Though it is possible to visually reconstruct the afterlife of monasteries in the Low Countries by using the technology of digital mapping,[13] the ad hoc nature of French convents during this post-Reformation period argues against the viability of such a strategy. What do we know about monasteries in France after the Council of Trent? Because of the often-secondhand nature of the buildings that religious communities inhabited, there is no Benedictine plan to fall back on. It seems as if the cloister was supplanted by galleries that provided access to the nuns’ choir, refectory, and parlor. The dormitory or the cells that it led to were in the most remote and inaccessible part of the convent, usually upstairs past the door of the sacristy in which the resident confessor was situated.[14] In addition to the cells, the dialectic between interior and exterior was particularly intense at the grills of both the parlor and the threshold that separated the nuns from the remainder of the congregation. Indeed, convent grills served as the site of numerous political, social, and economic transactions. As a main artery to the public sphere, the activity at the grill in conjunction with other reforms, such as institutional homogenization and centralization, helped usher in the early Modern period.[15]

Considering the elusive nature of the early Modern convents, I will examine the monastery through a medieval architectural lens, as the symbolism of its parts remained constant. The character of the small cells seems to echo the devotional works created by nuns in homage to the Virgin Mary and Christ. As Barbara Baert has demonstrated with the Enclosed Gardens made by nuns in the Low Countries, the latter functioned as a sanctuary for interiorization.[16] In the seventeenth century nuns were encouraged to work with their hands, for manual labor was not solely intended to suppress pride and willfulness, but also to foster pleasure: pleasure of the body in movement, pleasure in creating a fine piece of work and admiring it, no matter how simple its form.[17]

The physical transformation of convents was accompanied by a shift in their function, as they became the depository for social deviants, madwomen, political or religious dissenters, and after the Edict of Nantes in 1696, a refuge for Huguenot women and children.[18] In this evolution, the cell also developed from a private retreat into an oratory where the nun was to offer her Lord and Father in secret, her particular prayers.[19] Further, the majority of monastic constitutions specified that the nuns must sleep alone in their respective cells, a statement that implies a somewhat casual adherence to this rule in the past. In Fontevraud, for example, three floors were devoted to dormitories, which in the eighteenth century were divided into 230 cells.[20] The cells, according to contemporary novels such as Diderot’s La religieuse, which uses the word cellule 80 times, or Jean Barrin’s Vénus dans le cloître, are portrayed in a very different light.[21] The cells described by Diderot are equipped with antechambers, garderobes and cabinets, which are more reminiscent of the suites of a wealthy mansion, and may have been reserved for corrodians or boarders, often wealthy widows in need of comfort and spiritual guidance from the resident nuns. The corrodians, permanent paying guests, often brought their own furniture and were expected to attend services and witness the elevation of the host, though they were prohibited from entering the nuns’ choir.[22] If the miniature nuns’ cells are not a literal evocation of the private chambers of the sisters, they clearly simulate the bridal chamber where they consummated their union with the Bridegroom. Though all property in a convent was considered communal, the nuns did have possessions that were earmarked as personal. The objects surrounding the effigy of the nun in the cells seem to fall into that category, while simultaneously corresponding to the furnishings prescribed by the constitutions of each order, and thus acquired by all the sisters.[23] The space allotted to most nuns in the eighteenth century was significantly diminished; it seems as if some orders maintained individual cells, while the less affluent houses utilized dormitories. All nuns were provided with narrow, hard beds in which they slept in their habits, either sitting up or lying down, imagining that they were in the tomb of Christ.[24] In the Abbey of Saint-Paul-lès-Beauvais there was a separate room dubbed the Sepulcher where an individual nun would go for a period of four days to contemplate her celestial Spouse, to read pious books, and to meditate on the mystical death.[25]

The prevailing attitude towards monasteries, and particularly nuns, vacillated considerably during the eighteenth century. Though many families still believed in the efficacy of the prayers of their daughters who entered convents, women who willingly embraced the unnatural state of chastity were suspect in the public arena. Helen Hills discusses the absent presence of nuns, whose beautiful voices wafted from their choir and whose alluring figures could be glimpsed through the grill in the church;[26] before long, these phantoms crystallized into accommodating nuns hidden under a cloak of virtue. Indeed, much confusion existed about whether convents were inhabited by women of unattainable virtue, or those with morals more suited to a brothel.[27] The monastic climate had clearly shifted both in theory and in practice. For example, in the 1790s twenty-six Visitandines spent two years in jail with other women in the Good Shepherd convent at Nantes. One of the nuns wrote the following: “Seven hundred of us were jammed into quarters intended for 200. Twenty or 40 women were put into a single small room. The beds were so close that one often found oneself under a neighbor’s cover. The sick and dying were mixed with healthy people. I can’t count the women who were infected thus and suffered and died at my side.”[28] Concurrently, convents were used as prisons, orphanages, retirement homes, hospitals, and a refuge for unmarried or widowed women. In Paris, the latter paid rent for either a room or suite of rooms and often donned the habits of their respective orders.[29] Despite the suppression of all monasteries at the time of the Revolution, a third of the old communities in France survived illicitly. Indeed, fifteen of the imprisoned survivors of the Nantes Visitation community followed their eighty-two-year-old superior back to their cloister and renewed their vows in 1810.[30]

In the later nineteenth century, the French lois laïques imposed corporate taxes on religious communities and by 1884 all religious real estate was taxed more heavily than lay holdings. The Third Republic, which abhorred nuns because of their aberrant and subversive lifestyle, dispersed 30,000 religious (out of 200,000) in 1901.[31] Again, in the face of these hardships, communities of nuns took simple vows and maintained their hospitals, asylums, and distributed soup to four thousand prisoners daily.[32] Teaching was the most prevalent occupation of sisters, particularly after the 1850 French Falloux Law gave the clergy the authority to assign education to the religious orders.[33] Throughout this early Modern period, then, the nuns’ cells would have conserved their identity and functioned as a refuge for the members of a religious community; not only did the cell provide a retreat from the onslaught of the outside world, but it also served as the site of the their union with Christ. Theresa of Avilà, drawing from the Song of Songs, described Augustine’s “holiest of holy places” within the nun in a manner similar to her cell: “when the soul desires to enter within herself, to shut the door behind her so as to keep out all that is worldly, and to dwell in that Paradise with her God.”[34] We will turn now to the meaning of different spaces within a monastery.

Space in the Convent

Behavioral codes are tailored to architectural spaces and that was particularly true in a convent. Indeed, proponents of the archaeology of gender would even suggest that space defined the inhabitants who dwelled there.[35] For example, the walls that constituted the claustration of the convent were both physical and metaphorical, dividing public from private.[36] Indeed, enclosure was a state of mind as well as body, each nun a microcosm of the convent writ large.[37] The cloister, whether virtual or real, was at once a symbol and a proxy for paradise enclosed by walls, the latter of which kept the world out as well as circumscribed the spiritual grounding of the nuns’ lives.[38] The permeability of the claustral walls was already recognized in the medieval period, and they became even more porous during the early Modern period. Nuns had to leave their convents for all sorts of reasons ranging from the care of the sick, assuring the welfare of family members, fundraising, seeking refuge from fires, warfare or famine, to basically running the business of the monastery.[39] Similarly, many outsiders were found within the claustral walls: visits from nobles, confraternities, family members, and travelers. The permeable walls also permitted the introduction of pious writings, literature, and other works of art into the community, which would have fostered the edification of and inspiration to the nuns.[40] When the convents assumed the role of educating young girls, these books played a more active role. The Ursulines supplanted the limited curriculum of Port-Royal, until they were superseded by the convent in the Faubourg Saint-Jacques in Paris; the lessons of the latter included Latin, poetry, history, geography, zoology, botany, and the leisure arts.[41]

In truth, the idea of enclosure extended to all areas of the nuns’ lives. The convent was composed of a series of withdrawing spaces created by walls and gates, all of which contributed to the idealized notion of the “hidden treasure” of the nuns’ incorrupt bodies.[42] The longevity of the principle of enclosure from the Reformation to the Council of Trent and even into the Modern period should not be underestimated, despite the accomplishments of nuns in the fields of education and health care. There was a clear division between the active and contemplative orders; for example, the nuns were called to live for God alone and to renounce the world, both of which implicitly endorse claustration.[43] Thus, space, which is itself a message system, played an active role in negotiating the social lives of the nuns, just as the canonical hours structured their temporal existence.[44]

Physical space and convent time were inextricably linked: a nun’s visions often involved a physical location inherited from her deceased superior. In one instance, Mary Xaveria, experienced her visions in the cell, choir, and refectory once occupied by her spiritual mentor.[45] It is interesting that the key moments of a nun’s life were often recorded as being out-of-time. Convent chronicles attempt to give temporal shape to a nun’s life from her arrival, clothing, profession, change of name, and of course her spiritual union with God. Space and time were conflated in a nonlinear manner, particularly in the fugitive moments of mystical ecstasy: place, notably the cell, grounds the spiritual union of the Spouse and the Bride. The nun’s cell provided the stage for the imitation of this union of the Bride with the Bridegroom.[46]

By the early Modern period in France, convents were no longer located in remote areas; they had migrated to urban centers. As noted above, both the shortage of land and the cost of property prompted the religious orders to take over and modify existing structures in which to house their communities.[47] In Paris, the first convent of the Discalced Carmelites was founded in the seventeenth century on the site of the priory of Notre-Dame des Champs on the rue St. Jacques on the left bank and became the motherhouse of 63 monasteries. As Barbara Woshinsky points out, this building privileged domestic spaces over the cloister; the latter did not exist at the outset and when it was added, the rectangular cloister was attached to the church and claustral buildings rather than being incorporated into them as was customary.[48]

The social mores dictated by vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity professed by most of the orders, required unconditional identification with the community, expressed in collective prayer and collective works.[49] And these values were mirrored in the architectural spaces of the convent. For example, central to the nuns’ vows as brides of Christ was their contemplation of the Body of Christ. The tabernacle containing the Blessed Sacrament was found in the chapel. Though communion was historically administered through the narrow opening in the grill of the convent portal, prayers before the Host were essential to the nuns, as the closer they stood to the Monstrance, the closer they were to Christ.[50]

The medieval concept of the cloister garden, which contained a fountain, and provided both spiritual and physical refreshment for the nuns, was largely symbolic by the time the miniature cells in this collection were made. In their inhabitation of repurposed houses, the sisters had forfeited the formal parsing of spaces inherited from their medieval predecessors. Yet the cloister remained the hortus conclusus in the Song of Songs 4:12; the enclosed garden was an emblem of the mystical marriage of Christ and the Church, the Bride of Christ.[51] In her quest for monasteries that survived the French Revolution, Woshinsky discovered Ste.-Claire in Mur-de-Barrès, founded in 1651, suspended in 1792, and restored after the middle of the nineteenth century; this convent was devoid of enclosing walls and in lieu of a cloister, there was an L-shaped room with large picture windows, and parlors with no separation between the nun and her guests.[52] Yet Ste.-Claire still provided the disposition of space that was conducive for educating wealthy young women in a provincial French town, a function that most convents of this early Modern period fulfilled.

As in the Middle Ages, the Virgin Mary sustained her part as exemplar for nuns above all others, not only because of her chastity and her participation in the suffering of her son on the Cross, but also because of her role as Christ’s spouse, the Church.[53] In her analysis of the intricate beaded and lace Enclosed Garden retables created by nuns, Barbara Baert views these works as an expression of the mystical union of the nun with Christ: “The Enclosed Garden thus becomes a metaphor for immaculacy, purity and virginity, as well as paradise, where, prior to the Fall, all was perfect……Enclosed Gardens provide a means for locating and entering the immaculate ‘place’ in one’s soul.”[54]

What function then did the nuns’ cells fulfill? Not simply a place to rest, the cell was a type of cloister within the cloister, a haven of peace; according to William of St. Thierry, “the closed door is not a hiding place but a place of retreat.”[55] Containing a bed, an altar, a kneeling stool, one chest or cabinet, a candle, holy water dispenser, a breviary and other books, the cells were for prayer, solitude, and silence.[56]

Figure 4. Large Carmelite Cell, beginning of 19th century, Made of breadcrumbs (Mie de pain), fabric, paper, cardboard, vegetal matter, wood, and glass. 24.3 x 27 x 22 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

The nuns’ cells performed a holding function, one that mirrored the Virgin’s function as a vessel for Christ, a concrete metaphor realized in the Vierge ouvrante sculptures created from the thirteenth century through the early Modern period.[57] In the nun’s visualization of herself as the bride of Christ, she prepares the house, that is herself, so that the Lord will find it beautiful, a fitting enclosed garden where only truth reigns. As Jeffrey Hamburger has demonstrated, the heart and mind were allegorized as architecture. Bernard of Clairvaux said: “Enter the bedchamber of your mind; shut out all things except God.”[58]

The nuns were to take the furnishings of their cells as a spiritual point of departure. According to the “Doctrine of the Hert” (sic) (De doctrina cordis), “near the bed is found peace and rest for the conscience; by the table penitence; by the chair a judgment of himself; and by the candlestick a confession of himself.”[59] It is through the objects that fill her cell that the nun enacts her mystical union with Christ, for these material things allow her to enter the heart of God, as well as penetrate her own soul.[60] To pray like Christ was to become Christ-like and the nun’s cell was the stage for this devotional act. Catherine of Siena urged nuns to “make Christ’s wounds your home.”[61] Indeed, it was the wound in Christ’s side that was the door to Salvation, a path to the interior of the heart where the nun sought refuge. The door was open so that the nun could consummate her mystical union with the Bridegroom.[62]

The survival of the miniature replicas of the nuns’ cells yields an intriguing object lesson in a specialized branch of nuns’ work, one that offers a vivid canvas upon which to reconfigure our knowledge about their past. These models, which were mostly destined for the nuns’ families once they professed their vows, functioned as memory boxes containing the external signs of their personal devotion and its performance, whether real or aspirational.[63] As Baert and Hamburger have demonstrated in other art works created by nuns, the space of the cells was imbued with spiritual meaning as there was a connection between physical work and spiritual labor. The fabrication of the miniature cells allies the nuns to the Virgin Mary who similarly occupied herself in meditative handiwork. Indeed, Mary was the archetype of pious labor and prayer as she labored at her spindle and thread.[64] The simulacrum of the cell was a substitute for the private chamber of the nun and serves as a ductus toward the absent site of the union of the nun and her Bridegroom.[65] The miniature size of the cell renders its meaning enhanced and its metaphoric value enlarged by the beholder’s ability to seize it with his or her eyes.[66] Because we think through solid metaphors, the model of the cell becomes the perfect locus for the nun to self-fashion her devotions to Christ within the bridal chamber prepared in her imitatio Sponsae.[67]

The diorama also possesses the power to trigger the memory of both the maker and the beholder by virtue of its miniature scale. The diminutive stature of the furnished chamber both situates detailed objects within space as well as amplifies the significance of those objects.[68]

Figure 5. Cell of an Augustinian Nun, late 18th century-early 19th century, Made of wax, fabric, paper, shells, leather, stucco, wood, cardboard, and glass. 33 x 28 x 22 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

All miniatures are inherently verbose according to Gaston Bachelard in The Poetics of Space, for every detail is essential in creating the context, which in turn, eternalizes the momentary, etching it into memory like a visual proverb.[69] As noted above, the nuns’ cells represent one moment, yet the vignette transcends time and space; the viewer finds oneself in the deep interiority of the convent in a frame of mind suggestive of nostalgia.[70] Indeed, the absorption in the delirium of descriptive detail relished on the material contents of each cell casts a spell reminiscent of reverie upon the beholder.[71] In other words, the miniature opens a privileged, atemporal, hyper-subjective space, one where memory and history occupy “a fissure in everyday space, creating a ripple in time.”[72]

In considering the following examples of miniature cells from various monastic communities, I suggest that a strong personal connection developed between the models of the cells and their creators, whether they were hewn out of pious devotion, as transitional objects that eased the passage of a novice to her professed state, as a souvenir for the sister’s family, or as a gift for an important donor. The meaning of the miniature cell, then, would have been colored by its destination. For example, if the family received the replica of their daughter’s private chamber, the effigy of the nun within would have been a substitute for their absent daughter. Immersed in prayer, reading a book, or hovering over a spinning wheel, the figure of the nun would have provided the family an image of their kin performing her prescribed rituals. If the model of the cell was intended as a gift for a benefactor of the convent, the activity of the ensconced nun may have inspired admiration and engendered subsequent donations to the monastery. Another scenario that cannot be ruled out is that the cell may have been given to a young postulant, one entering the convent at the age of five, ten, or twelve, and thereby serving as a plaything.[73]

Does the material evidence of the miniature cells provide the outsider with enough fodder to suggest the genre of self-portraiture or perhaps a type of memoir? The detail and precision of the miniature cells display a degree of immediacy to the beholder; ironically, the particularity of the nun’s performance at times seems to be eclipsed by its universality. For each nun is at once Mary and Martha, embodying the two sides of her vocation.[74] In the simulacra of the cells, the life of the nun is enshrined: the self is both the subject and object of memory. And because the self is never far removed from the social, the cells become historical documents of monastic life. The narrative of the self that emerges from this process cannot be divorced from the construal of the self, which in turn is shaped by culture. As Hazel R. Markus and Shinobu Kitayama put it: the way people initially and naturally perceive and understand the world is rooted in their self-perceptions and self-understandings, understandings that are themselves constrained by the patterns of social interactions characteristic of a given culture.[75] The self then is shaped both by memories and culture.

The individual functions either independently, where others are less implicated in one’s identity, or interdependently, where others constitute a part of one’s self-construal.[76] Nuns living in a monastery clearly fall into the second category in their responsiveness to and responsibility for their sisters. Both independent and interdependent identities see their lives tied to narratives, which in turn impose meaning on those lives.[77] These narratives convey the suppositions about both the world of the individual and the world of the social, transforming memory itself into a cultural vehicle.[78] Jens Brockmeier defines narratives as the variety of methods by which we acquire knowledge, structure action, and order experience.[79] I believe that the nuns’ miniature cells provide a glimpse of the narratives sewn by the sisters in the daily practice of their faith. The traces of individuality found in the nuns’ cells do not obviate the interplay and mutual dependence of the sisters, nor the previously separate realms of the individual and the collective, the private and public, and the timeless and historical.[80] The genre of memoir created by the nuns in the replicas of their cells, then, reflects the social embeddedness of memories: self-narratives do not attempt to recover the past, but rather they re-imagine it by their rendition of the self, immersed in history.[81]

Nuns, no matter which order, were part of a collective. The monastic community always overshadowed the status of the individual. Yet within the collective one might see these cells as the separate gifts of the nuns in the body of Christ:

For as in one body we have many members, but all the members

have not the same office;

So we being many, are one body in Christ and every one members one of

another.

And having different gifts, according to the grace that is given us. [82]

What strikes me as so useful about this understanding of the social construction of self-narratives is that there is a reciprocity in the negotiation of the meaning of lives: each nun is knitted into her sisters’ narratives, just as they are into her story.[83] The physical object of the cell offers a window onto this intersection of the whole and the parts that comprise it. As observers, we are privy to both the physical landscape and the inner landscape in which the lives of the nuns unfold. The transparent façades of the miniature cells invite us to project ourselves into the past and into the future; it is this time travel that exposes us to the interiority of the lives of the nuns and the universality of the human values that guides their lives.[84]

To see the face of the nun in the fabrication of her cell is to apprehend the power objects possess to shape our world. Not to heed the clues embedded in the cells would deprive the observer of the stories communicated by the nuns in these byproducts of their religious faith. A significant part of living in enclosure was the nuns’ inscription of Christ on their bodies.[85] The body of the nun was a figurative edifice contained within her permeable cell, always tempted by sin; yet Christ was her dovecote, its openings and streams of blood offering redemption to the nun struggling against the sins of the flesh.[86] As the locus of the nun’s encounter with Christ, her cell was endowed with the symbolism of the nuptial chamber as the spiritual exchange between Christ and his bride occurred beside the bed within the thalamus. The latter replicates the virginal womb of Mary, and in so doing conjures the Annunciation to the Virgin of the birth of Christ.[87] Indeed, the thalamus is a metaphor for the incarnation of the Son of God as a man as well as the virginal divine maternity.[88] According to Albert Châtelet, the portrayal of a bed in the depiction of an Annunciation to the Virgin, such as that of Rogier van der Weyden in the Louvre Museum of c. 1434-35, alludes to the mystical union of the Virgin with Christ.[89] The presence of a bed in each nun’s cell is clearly a necessity, yet could it also be a key to the meaning of each diorama? The Patristic writers from St. Ambrose in the fourth century through St. Lawrence Justinian in the fifteenth century invoked the purity of the thalamus or virginal womb chosen by the Word of God to dwell among us.[90]

The imprint of the sensual experience of this mystical union may be sensed in the cells that populate the collection of the Trésors de Ferveur. Did the creation of the miniature cell constitute a pious endeavor for the nun, one in which she wished to confirm the veracity of the Incarnation by her humble efforts? For each nun in her handicrafts emulated Mary with her pursuit of ora et labora.[91] The scrupulous simulation of the details of her private chamber, from the furnishings to the holy water dispenser, suggests a state of contemplation not unlike prayer that accompanied the construction of these objects. The contents of her cell—the breviary, candle, prie-Dieu, image of the Crucifixion, and the simple yet direct invocation “Dieu Seul” convey the conviction harbored by the solitary nun within her cell. Shaping a dollhouse of her monastic cell afforded the nun the opportunity to rehearse her piety in a performative fashion, staging her devotion on a miniature scale for a larger, yet still restricted audience.[92]

The nun’s daily devotions to the Passion of Christ encouraged her not only to enter the heart of Christ through his side wound, but once there to be transformed into the crucified Savior. “Fastened to the Cross by the nails of the fear of God, transfixed by the lance of the love of your inmost heart, pierced through and through by the sword of the tenderest compassion, seek for nothing else, wish for nothing else except in dying with Christ on the Cross.”[93] This transformation was reinforced by the nun’s daily routine from the chanting of the Divine Office, to the execution of her chores, to her time spent in the cloister—doing God’s work always under divine scrutiny. Even though the nun’s private engagement with Christ was relegated to her cell, this pious encounter was reified throughout the day in various parts of the monastic complex.

Examples of Cells in the Collection of the Trésors de Ferveur

In turning to the Carmelite order of nuns, their three essential values of fraternity, service, and contemplation were fulfilled by obedience, chastity, and renunciation of ownership. Each sister was to be given a separate cell as disposed by the prioress, whose own cell stood near the entrance to the nuns’ individual cells. The nun was to ponder the Lord’s law both day and night and keep watch at her prayers unless attending to another duty. Other virtues stressed in the rule were fasting, abstention from meat, eschewing idleness, embracing silence, and following the admonition to don the word of God at all times.[94] In this square chamber of a Carmelite nun, dating from the eighteenth century and originating in Burgundy [Figure 3], one finds a wood beam ceiling and a large leaded glass window located in the left quadrant of the room.

The nun, who is fashioned out of wax clad in the brown Carmelite habit, is seated at her spinning wheel holding the distaff with her right hand and leading the wool skein with her left hand. The decoration of this cell is rather spartan with a simple bed, chair, bookshelf, and corbel on the right wall. Images of the Sacred Heart of Mary and St. Louis Gonzaga are found on the back wall divided by a wood cross; a holy water dispenser is suspended between the bed and the chair. Despite this minimalism, the shutter of the window is delineated with four panels and the exterior of the cell is a deep forest green. This example reflects both a fastidious mind and careful hand at work.

It is interesting to contrast the simplicity of the model above with that of an early nineteenth-century Carmelite cell that is more fully furnished, not only with objects for use but also words of dedication [Figure 4] « Ma fille / qu’es tu venue / faire ici ! » is above the shelf ; « O que l’ame est heureuse / et tranquille dans ce / pauvre et charmant asile » is over the window; « DIEU SEUL » located on the back wall; “Une ame pénitente / trouve ici des douceurs tout / lui plait tout l’enchante la / croix fait son bonheur » is above the door; and on the exterior of the vault is found « Je veux monter au Calvaire / Sur les pas de mon doux Sauveur / Et ainsi que le fit Therèse notre Mère / Chaque jour m’immoler pour lui / gagner des cœurs. »[95] The nun, kneeling before the window, holds a large open book in her hands and to the right is a desk with her ink and goose feather pen flanked by a large sand timer used to measure the rhythm of the hours imposed upon the nun.[96] The Adoration of the Shepherds adorns the back wall and a large cross sheathed in foliage is above the bed. The door to the cell is articulated with hinges, handle and a sliding bolt, and serves as a foil for the broom and white cloth suspended from hooks at the top. Beside the door hangs a cushion and at the foot of the bed is a basket containing a scapular and rosary beads.[97] What does this array of objects tell us about the resident Carmelite? The bowed walls of the cell seem to embrace the nun amidst the very fabric of her faith so that she too becomes an object in this tableau of devotion.

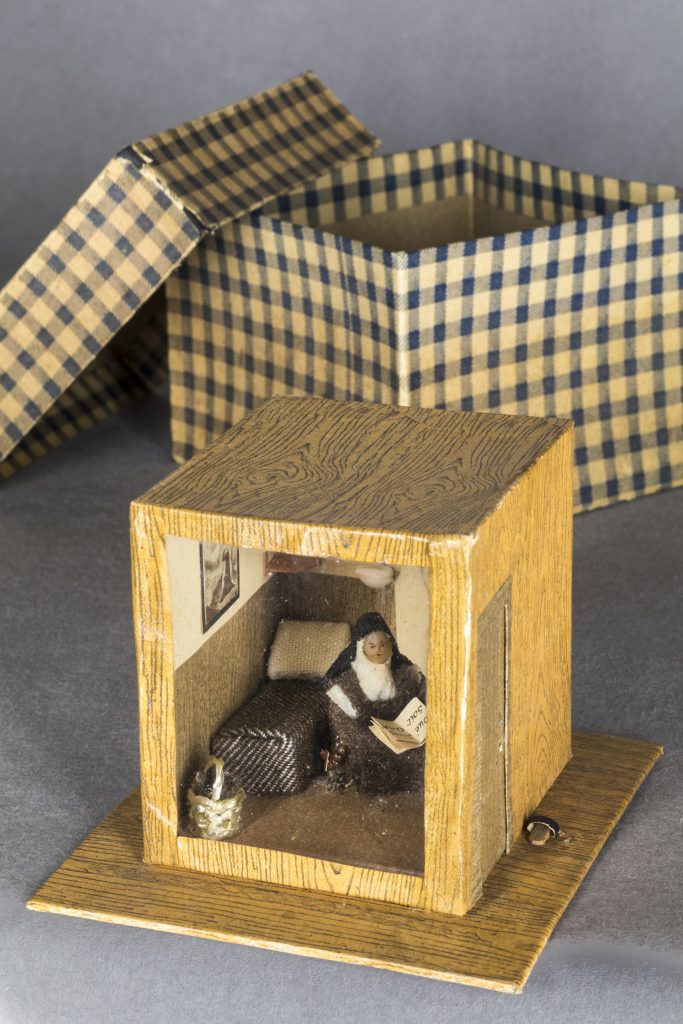

Though many of the Carmelite cells are fashioned with roofs and comparatively lavish exteriors, the third example is diminutive in scale, rests upon a socle, and is equipped with a black and yellow checkered carrying box with a matching lid.

Figure 6. Carmelite Cell with box for transport, 19th century, Made of wax, fabric, paper, cardboard, straw, shells, and glass. 7.8 x 9.7 x 10.6 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

The nun sits in the middle of her cell reading the following words on her open book: « Loué Soit / Jesus Christ ». (Praise Be [to] Jesus Christ). She is surrounded by the same unpretentious objects we have seen before, though the pseudo-wooden dado and four-part window engender an even greater intimacy in this cell. The sensible placement of her clogs outside the portal to the cell offers a subtle comment on the prudent character of this nun.

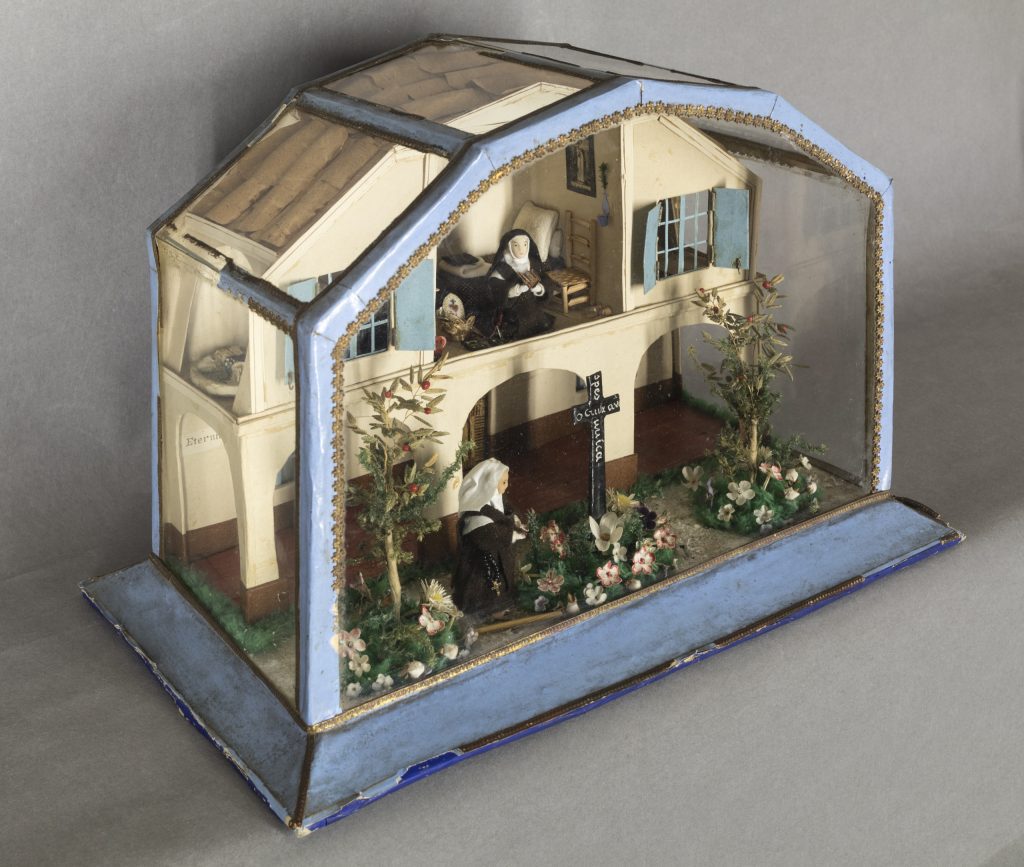

The section of a Carmelite cloister from the southwest of France, which dates to the nineteenth century, warrants comment as it invites us into the convent garden being tended by a nun as well as gives us access to the praying nun seated in the upper story.

Figure 7. Overall View of a Carmelite Cloister from Southwestern France, 19th century, Made of cardboard, paper, fabric, wax, plaster, and glass. 23.5 x 34 x `9.5 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

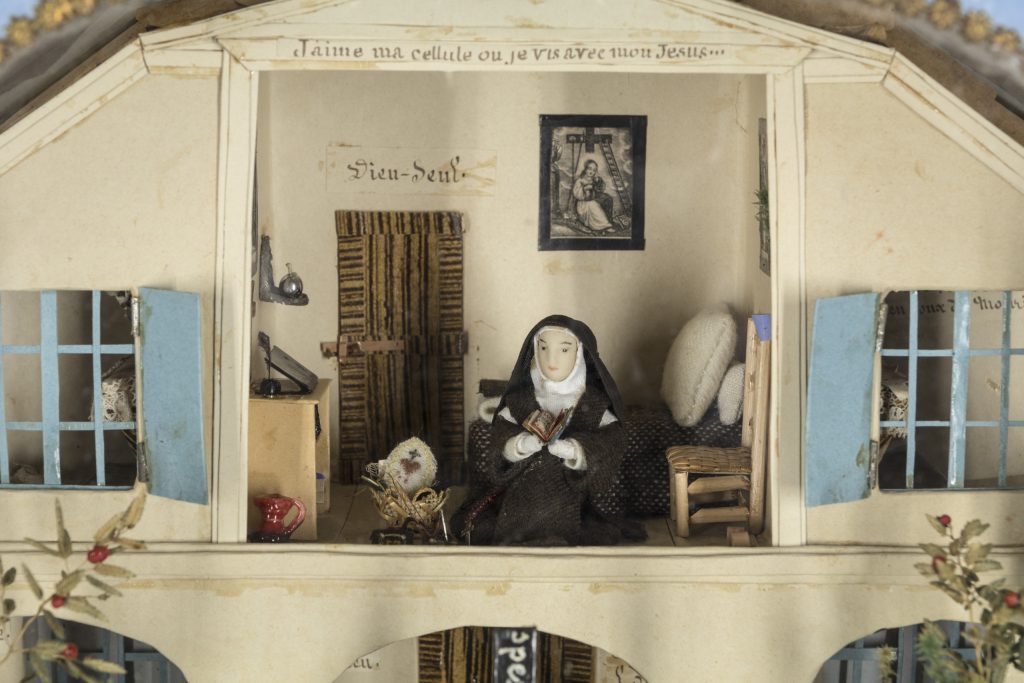

Figure 8. Upper story of Carmelite Cloister from Southwestern France, 19th century, Made of cardboard, paper, fabric, wax, plaster, and glass. 23.5 x 34 x `9.5 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

Further, a view down the corridor reveals the doors to individual cells and above, a glimpse into two oratories, one of which displays a statue of a Virgin and Child on an altar. Sentences are inscribed throughout the cloister. To the left, « Ou Souffrir ou Mourir; » to the right, « S’il est dur de vivre au Carmel / il est bien doux d’y mourir. » On the lower inner wall of the cloister are the following sentences:

« Eternité; » « Ma nourriture / est de faire la / volonté de Dieu; » « En parlant âmes / Sœurs je prête / l’oreille à Dieu; » « Silence. »[98]

The materials used to create this diorama are cardboard, paper, fabric, wax, plaster and glass; the cutaway sides and absent façade of the cloister are surmounted by a roof of tubular tiles (canal style), which create the appearance of a two-story dollhouse of another era. Housed in her cell, the nun is reading what appears to be an illuminated manuscript, surrounded by the accessories of monastic life: notably a glazed water pitcher, a bookshelf with numerous volumes, a cross, a basket containing a woven sampler decorated with the Sacred Heart surmounted by a cross and her needlework. The door to her cell is quite elaborate with linear grooves down the front and a border of shorter grooves on all four sides; it also has an elaborate latch and door handle. On the lintel above her is the statement: “J’aime ma cellule ou je vis avec mon Jesus.” This cloister is of quite high quality when compared to many of the other cells in the collection and it is intriguing to ponder its original purpose, owner, and destination. One possibility is that the cloister may have been fabricated for a wealthy donor of the monastery in which this beautiful model was produced. The gift of this precious monastery would have been a reminder to the patron of the power of donations to wield not only gratitude, but also beauty, creativity and reciprocity.

Though space does not permit an examination of the miniature cells from all the orders, it is instructive to consider examples of nuns’ cells from other convents. For example, one is struck by the distinctive touches found in the Capuchin cells, which include rather soft beds covered in white wool spreads, the quiet meditative tenor of the nuns, and the emphasis on the devotional tools and inscriptions highlighted on the walls. In the first example from the nineteenth century, the nun, composed of painted wax, holds an open book close to her heart but looks to the left; her brown habit with its knotted belt falls to the floor where one sees her bare feet shod in sandals peeking out.

Figure 9. Cell of a Capuchin, 19th century, Made of wax, fabric, paper, cardboard, wood, vegetal fiber, and glass. 35.5 x 48.3 x 28 cm. Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

Above the nun and between two engravings of the Crucifixion and St. Veronica Giuliani, a mystical Italian Capuchin, one finds this homage to the nun’s chamber: “O Ma Chère Cellule!/ O Ma/ Seule Béatitude.” The inscriptions continue on the right wall: “Tout mon Bonheur/ est en/ Dieu Seul;” and on the left wall: “O Sainteté/ de/ L’état Religieux.” Above the door is the identifying statement: “Cellule D’une Pauvre Capucine.”[99] Upon the table to the right rests a large black book and a sand timer; perhaps this Capuchin is measuring the very devotions captured in this still-life arrested in time and space.

A Capuchin cell that originated in Provence from the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, exhibits a vaulted interior and an exterior adorned in blue wallpaper embossed with floral patterns [Figure 1]. The nun within is composed of breadcrumbs (mie de pain) and clothed in fabric; she is in the process of spinning wool on a spindle, with the cross-shaped distaff held in her left hand. The cruciform distaff echoes the large silver Crucifix that terminates her prayer beads on the lower skirt of her habit; this silver cross displays a bas-relief figure of Christ. Adjacent to the corner table, which supports the standard fare, one sees the sculpted lower half of a figure of the crucified Christ. It is striking that the devotional objects are rendered in low relief in this Capuchin cell; was this a decision based on aesthetic concerns or was it a question of available funds to afford this embellishment? We will observe a similar predilection for sculptural devotional objects in the cells of the Augustinian nuns. The composite effect of this cell, from its red and yellow checkered tile floor to its ornate blue shell, to the repetition of crosses in the composition (the window panes, the distaff and the silver crucifix), is that of a personal refuge.

The orders that we have discussed thus far have followed permutations of the Rule of St. Benedict. The Augustinian nuns were based on the rule written by St. Augustine of Hippo for his sister in 423.[100] It is immediately apparent upon viewing the first of two cells from the same convent, that Augustinian nuns, whose vows did not include that of poverty, welcomed the comforts of home in the decoration and maintenance of their private chambers [Figure 5]. In the center of the cell, the wax proxy for the nun, dressed in a gray and black habit, kneels at her prie-Dieu with an open book in her hands. Her room is nothing short of cluttered with furniture and objects that forge a composite portrait of the sister. A silk embroidered bedspread covers her ample bed, which is in turn covered with a patterned silk drape; the walls are lined with pious images, her broom leans against her holy water dispenser, which is crowned by palm leaves, and her rope discipline hangs on the left wall. The sculpted Crucifix surmounts the fireplace, whose ledge is filled with pots and bowls seemingly made of clay. The bookcase in the right corner displays twelve bound volumes and is above the spindle and distaff beside the desk and chair. A covered pitcher, an inkwell and pen, a timer, and an open folio cover the surface of the desk, which is thoughtfully situated before the cell’s window. The latter features muslin curtains that are open, despite the rather somber light in the room. In the foreground, one finds sandals by the foot of the bed, a full basket of woven goods, and a water basin and pitcher. This cell speaks to the greater freedom of the Augustinian order, but also to a more robust aesthetic, which is even more apparent in the other example we will examine.

In the second Augustinian cell, which also dates to the eighteenth century, one encounters a similar disposition of furniture and artifacts, though the latter have become denser and are punctuated by pious sentences in both French and Latin.

Figure 10. Cell of an Augustinian Nun, 18th century, Made of wax, fabric, paper, shells, leather, stucco, wood, cardboard, and glass. 37 x 29 x 23 cm Photo: Jean-Michel Gobillot, Courtesy of Thierry Pinette.

One of the most deluxe features in this room is the bookcase in the right corner, which contains over twenty leather bound books; the covers of many of these volumes are embellished with gold lettering and designs. Erupting from the red floor between the basket of weaving and the water basin and pitcher are four white protuberances. Upon closer scrutiny, one recognizes the shapes as shells, a symbol of St. Augustine. According to the Golden Legend of Jacobus Voragine, Augustine encountered a small boy in Africa trying to transfer all the contents of the sea into a little pit in the sand using only a shell to convey the water. When Augustine questioned his methodology, the child replied that it was like the doctor’s own attempt to explain the mystery of the Trinity with the limited understanding of the human brain.[101]

Above the nun’s head, an inscription reminds the viewer: “Nous ne sommes pas chrétiens pour être riches et pour vivre dans les plaisirs. Il ne fallait pas pour cela faire de Christianisme; il n’y avoir qu’à laisser le monde comme il étoit. Sous l’empire de l’opinion et de la pis….”[102] “Croyons nous que le félicité confond dans les larmes, et que les riches soient malheureux? Cependant c’est un article de foi, dont la créance n’est pas moins nécessaire au salut, que celle de la Trinité et de l’incarnation.”[103] On the left wall a text labeled “de la Sainte Vierge 207 Réjouissez vous, O Vierge, Mère de Dieu, pour le plaisir que vous recevez en Paradis, parce que comme le Soleil ici bas en terre éclaire tout le monde, de même avec votre splendour vous embellissez et faites reluire tout le Paradis. Ave xx.”[104] Is it possible to see in the contemplative disorder of these two cells the humanity of St. Augustine’s philosophy [Figures 5 and 10]? Or is this merely evidence of the presence of an abbess whose code of housekeeping was more relaxed than that of say the Carmelites or Capuchins? In other words, how do we read these two cells? The occurrence of color even in the saints’ images, the embroidered bedspreads beneath a colorful silk swath of drapery, the sculpted Crucifixes and exuberant holy water dispensers, the copious manuscript holdings and weaving supplies, convey the impression of a more indulgent community of nuns. No less reverent or committed to their vows than the other sisters we have observed, the Augustinians merely exhibit the traces of a richer material existence, one infused with the ethos of their spiritual founder.

Reading the Language of the Miniature Cells

The similarities and differences that unite yet individualize the nuns’ cells invite speculation about their purpose, fabrication, significance, and the relationship between the miniature cell and the particular religious who realized the final form of each diorama. The nuns’ cells provide the observer with a glimpse into the warp and weft of the individual sister’s existence, the tension that characterized her life as a member of a monastic community. One of the recurring inscriptions on the walls of the cells was that this room was the nun’s refuge, her isle, her haven. It was within this refuge that the nun performed her vocation as a bride of Christ. Did the sister’s choice of images, samples of sewing, and moral precepts reflect the personal or the collective side of the nuns who created them? I would suggest these material traces do betray the individuality of the nun. The simulacrum of her cell is at once a façade and an interior, embodying the composite nature of the sister’s life. As a place of memory, the replica of the nun’s cell occupies a threshold space, one in which the creator has become a producer of meaning through the collage of artifacts she has displayed.[105] The latter serve as anchors for emotional attachment and memory and serve in piecing together each nun’s story as objects have the capacity to shape and inform identity.

Though the cells inhabited by the nuns do not approach the level of enclosure of those occupied by hermetic anchorites, I believe they share a quality of intimacy that approximates the nature of an anchorhold, such as that invoked in the writings of Julian of Norwich (1342-1416).[106] The enclosure of her cell was a potent metaphor for Julian: the immurement of her chamber not only mimicked the walls of a tomb signaling her death to the world, but also the boundaries of a womb, which announced her rebirth into the glory of God.[107] In essence, the inhabitation of an anchorhold meant a rejection of the past and the commencement of a new life.[108] Julian’s understanding of God’s redemptive love of humanity was fostered by the enclosing walls of her cell. It is my belief that the stories of the nuns who fabricated the miniature cells in the collection of the Trésors de Ferveur may similarly be revealed in charting the placement of the basin and pitcher, the vestments in the weaving basket, and the earnest etiquettes inscribed upon their walls.

What is the experience of the viewer of the miniature cells? In a way, the cells function as a metaphor of convent life. The open façades of the miniature cells offer a window onto the world, one that focuses the gaze of the viewer on the interiority of the nuns’ lives. The opening replicates the exposure of the nuns to the outer world, even though that world is both circumscribed and cloistered. At this intersection of the two halves of the nun’s world, the observer has a privileged view of the deeper context of the author of the cell: the sister becomes a part of the landscape and the landscape a part of her. The opening of the cell, the invisible fourth wall, not only constitutes the absent physical barrier, but also activates a temporal boundary allowing the nun and the viewer to travel back and forth in time. The intimacy of the private chamber frames the nun in the fullness of her monastic practice as a bride of Christ. Yet when the sister projected herself inside the humble replica of her refuge, she stood alone to meet Christ and experience a foretaste of the visio Dei.

References

| ↑1 | Thierry Pinette and Laurie Monnier (dir), Catalogue, Cellules de nonnes, of the collection of the Trésors de Ferveur (Chåtillon-Coligny: Musée du Hiéron, 2018), 5-7. These cells were on display in the Fine Arts Museum of Paray-le-Monial in 2018 and are the basis of this study. The collection, which is primarily focused on the monastic cell, also features scenes in eggs, walnut shells, and nuns’ portraits; it includes 6,816 religious objects. To date, there are 74 Carmelite cells, 55 Franciscan examples (various branches), 13 Visitation, 6 Cistercian, 5 Augustinian, 5 Chartreuse, 4 Ursuline, 3 of the Society of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, 1 Dominican, 1 of the order of the Annunciation, 1 cell of a Hospitaller of Notre Dame of Charity, and one cell of a Canoness. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “St. Adélaïde de St. Joseph / Why have you come / here for religion.” |

| ↑3 | “This is my (only) / true science.” |

| ↑4 | “Les cellules de nonnes,” 94. |

| ↑5 | The bibliography on cabinets of curiosity is extensive. See, for example, the following works: Horst Bredekamp, “Kunstkammer, play-palace, shadow theatre: Three thought loci by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,” Collection, Laboratory, Theater: Scenes of Knowledge in the 17th Century, ed. H. Schramm, L. Schwarte, and J. Lazardzig (New York and Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2005), 266–82; Beket Bukovinskà, “The Known and Unknown Kunstkammer of Rudolf II,” Collection, Laboratory, Theater, ed. Schramm, et.al., 199–227; Robert J.W. Evans, Rudolf II and his World: A Study in Intellectual History 1576–1612 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973; Eliška Fučiková, “Die Sammlungen Rudolfs II,” Die Kunst am Hofe Rudolfs II, Prague, ed. E. Fučiková, B. Bukovinskà, and I. Muchka (Prague: Aventium, 1988), 209–46; B. Gutfleisch and J. Menzhausen, “How a Kunstkammer should be formed”: Gabriel Kaltemarckt’s Advice to Christian I of Saxony on the Formation of an Art Collection, 1587,” Journal of the History of Collections 1 (1989): 3–32; Alexander Marr, “Introduction,” Curiosity and Wonder from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, ed. R. J. W. Evans, and A. Marr (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2006), 1–20; Joachim Menzhausen, “Elector Augustus’ Kunstkammer: An Analysis of the Inventory of 1587,” The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-century Europe, ed. O. Impey, and A. MacGregor (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985), 69–75; Krzysztof Pomian, Collectionneurs, amateurs et curieux: Paris, Venise: XVIe–XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Editions Gallimard, 1987); Merchants and Marvels: Commerce, Science, and Art in Early Modern Europe, ed. P.H. Smith and P. Findlen (New York and London: Routledge, 2002); Dirk Syndram, “Princely Diversion and Courtly Display: The Kunstkammer and Dresden’s Renaissance collections,” Princely Splendor: The Dresden Court, 1580–1620 (Exhibition catalogue, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden/Metropolitan Museum of Art), ed. D. Syndram and A. Scherner (Milan: Metropolitan Museum of Art and Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 2004), 54–69; and Vecchio Adriana Turpin, “The New World Collections of Duke Cosimo I de Medici and their Role in the Creation of a Kunst- and Wunderkammer in the Palazzo Vecchio,” Curiosity and Wonder, 63–86. See also Annette C. Cremer, “Utopia on a Small Scale – Female Escapism into Miniature,” Dolls, Puppets, Sculptures and Living Images from the Middle Ages to the end of the Eighteenth Century, ed. Kamil Kopania (Bialystok: The Aleksander Zelwerowicz National Academy of Dramatic Art in Warsaw and the Department of Puppetry Art in Bialystok: 2017), 126-39, esp. 127-30. Barbara Baert has compared Kunstkammers to the enclosed gardens fashioned by women in the Low Countries in the late Middle Ages. See Barbara Baert, Late Medieval Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries (Leuven: Peeters, 2016). |

| ↑6 | Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1993), 61; J. Allan Mitchell, Becoming Human: The Matter of the Medieval Child (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 94–95) does not subscribe to Gaston Bachelard’s theories about miniaturization’s power to minimize the impact of certain cult objects, such as votive effigies, reliquaries, holy dolls, etc. that are often invested with great power; for example, Mitchell suggests that the space plotted upon the mappae mundi or astrolabe remains strange and inaccessible to humans, in contradistinction to that of the dollhouse, which fosters transcendence and totalizing views. Cf. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969); Elina Gertsman, Worlds Within: Opening the Medieval Shrine Madonna (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015), 48–50, discusses the panoptic view encouraged by the Shrine Madonna’s miniaturized interior world and the effects engendered by this interior world vis-à-vis the beholder. |

| ↑7 | Stewart, On Longing, 61. |

| ↑8 | Dagmar Motycka Weston, “‘Worlds in Miniature:’ Some Reflections on Scale and the Microcosmic Meaning of Cabinets of Curiosities,” Architectural Research Quarterly 13, no.1 (March 2009): 37-48, esp. 44–46. In 1631, Anna Köferlein from Nuremberg assembled a dollhouse for public use with an accompanying pamphlet explaining how the miniature house could function as an object lesson in household management. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135913550999008X |

| ↑9 | Stewart, On Longing, 44-69. |

| ↑10 | Stewart, On Longing, 43-47. |

| ↑11 | Melinda Alliker Rabb, “Johnson, Lilliput, and Eighteenth-Century Miniature,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 46, no. 2 (2013): 281-98, esp. 289-91. https://doi.org/10.1353/ecs.2013.0013 |

| ↑12 | Gabriella Zarri, Nuns: A History of Convent Life, 1450-1700 (New York and London: Oxford University Press, 2007); for the period of reforms in the fifteenth century and its aftermath, see Jo Ann Kay McNamara, Sisters in Arms Catholic Nuns through Two Millennia (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1996), 385-418 and 419-51, respectively. For the Council of Trent, see Patricia Ranft, Women and the Religious Life in Premodern Europe (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1996), 104-31; Cf. Claire Walker, Gender and Politics in Early Modern Europe: English Convents in France and the Low Countries (Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 45-129; for the repercussions of the Council of Trent, see Ulrike Strasser, “Early Modern Nuns and the Feminist Politics of Religion,” The Journal of Religion 94, no. 4 (2004): 529-54; Nita Choudhury, Convents and Nuns in Eighteenth-Century French Politics and Culture (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2004) explores the parameters of the French Revolution; see also Geneviève Reynes, Couvents de femmes: La vie des religieuses cloîtrées dans la France des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Paris: Fayard, 1987), esp. 201-74. For the period following 1797 through the early twentieth century, again, see McNamara, Sisters in Arms, 565-627. For an overview of this period, see Barbara R. Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces in France, 1600-1800: The Cloister Disclosed rev. ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2016). |

| ↑13 | Reinout Klaarenbeek, “The Secularization of Urban Space: Mapping the Afterlife of Religious Houses in Brussels, Antwerp and Bruges,” Mapping Landscapes in Transformation, ed. Thomas Coomans, Bieke Cattoor and Krista De Jonge (Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2019), 237-48. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjsf4w6.13 |

| ↑14 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, 161-67. |

| ↑15 | Strasser, “Early Modern Nuns,” 539-49. See also Susan E. Dinan, “Spheres of Female Religious Expression in Early Modern France,” Women and Religion in Old and New Worlds, ed. Susan E. Dinan and Debra Meyers (New York: Routledge, 2001), 71-92; Elizabeth Rapley, Dévotes: Women and Church in Seventeenth-Century France (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1990). |

| ↑16 | Baert, Late Medieval Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries, 8. |

| ↑17 | Reynes, Couvents de Femmes,106. Reynes notes that if the nun took an interest in this craft, the goal of the work would be the humiliation of the flesh. |

| ↑18 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, 161-82. |

| ↑19 | Philippe Sellier, “Port-Royal: un emblême de la réforme catholique,” Port-Royal et la Vie Monastique: actes du colloque tenu à Orval (Belgique) les 2 et 3 octobre 1987, Chroniques de Port Royal 37 (1997): 15-26. |

| ↑20 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, 219; Fontrevaud became a prison, whose last inmate died in 1985. |

| ↑21 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces; Woshinsky throughout her book compares fictional depictions of convents with what we know to be true about contemporary monasteries. |

| ↑22 | The affluent boarders may have occupied viewing galleries in the secular end of the church. See Eileen Power, Medieval English Nunneries, c. 1275 to 1535 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1922), 404. |

| ↑23 | Reynes, Couvents, 117-18; Reynes delineates the contents of the cells, although she does not see them as personalized. The appearance of a relic or faience cup in certain cells suggests otherwise to me. Cf. Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, 264-65, for a list of furnishings specified in the Constitution of Port-Royal. |

| ↑24 | Reynes, Couvents, 65, 115-19. See also Étienne Poncher, Règle de saint Benoît, avec les statuts du R,P.E. Poncher, adaptés aux religieuses et conformes à la louable pratique du présent (Paris: P. Chadière, 1646), 307-08. |

| ↑25 | Jacqueline Bouette de Blémur, Éloges de plusieurs personnes illustres en piété de l’ordre de saint Benoît I (Paris: L. Billaine, 1679), 505 as cited by Reynes, Couvents, 71, n.18. |

| ↑26 | Helen Hills, Invisible City: The Architecture of Devotion in Seventeenth-Century Neapolitan Convents (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 181. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195117745.001.0001 |

| ↑27 | Reynes, Couvents, 179-99; French kings acted as sultans, using monasteries as their harems (183). In some instances, such as Maubuisson and Montmartre, the convents were virtual houses of prostitution. |

| ↑28 | Étienne Catta, La vie d’une monastère sous l’Ancien-Régime: La Visitation Sainte-Marie de Nantes (1630-1792) (Paris: Vrin, 1954), 542, as cited in McNamara, Sisters in Arms, 560, n. 26. |

| ↑29 | Reynes, Couvents, 221-33. |

| ↑30 | Catta, La vie d’une monastère, 556 as cited in McNamara, Sisters Arms, 567, n. 2. |

| ↑31 | McNamara, Sisters Arms, 570-71; the dispersed nuns were assigned to foreign missions. McNamara suggests that the chaste nuns were targeted because they stood both for oppressive male authorities and victimized institutions. Lesbianism was also a major charge against nuns of this era, see Christopher Rivers, “Safe Sex: The Prophylactic Walls of the Cloister in the French Libertine Convent Novel of the Eighteenth Century,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 5, no. 3 (1995): 381-401. |

| ↑32 | McNamara, Sisters in Arms, 601. |

| ↑33 | Elizabeth Rapley, “Women and the Religious Vocation in Seventeenth-Century France,” French Historical Studies 18, no. 3 (1994): 613-31; as Rapley points out, nuns had the privilege of teaching in the seventeenth century as well; see Carol Baxter, “Paradoxes of Early Modern Nuns and Gender Equality: The Case of Port-Royal in Early Modern France,” Towards an Equality of the Sexes in Early Modern France, ed. Derval Conroy (Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2021), 113-34; McNamara, Sisters in Arms, 621. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429275203-8 |

| ↑34 | Theresa of Avilà, Way of Perfection, from Works 2:120 as cited in Nicky Hallett, “’So short a space of time’: Early Modern Convent Chronology and Carmelite Spirituality,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 42, no. 3 (2012): 539-66, esp. 559. https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-1720580 |

| ↑35 | This approach is embodied in the scholarship of Roberta Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women (London and New York: Routledge, 1994); Suzanne Campbell-Jones, In Habit: An Anthropological Study of Working Nuns (London and New York: Pantheon, 1979); Jane Tibbitts Schulenburg, “Strict Active Enclosure and its Effect on the Female Monastic Experience,” Medieval Religious Women, I. Distant Echoes, ed. J.A. Nichols and L.T. Shank (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1984), 51-86; Drid Williams, “The Brides of Christ,” Perceiving Women, ed. S. Ardener (London and New York: John Wiley, 1975), 155-74; Alexa G. Winton, “Inhabited Space: Critical Theories and the Domestic Interior,” The Handbook of Interior Architecture and Design, ed. Lois Weinthal and Graeme Brooker (London and New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2013), 40-49. |

| ↑36 | Jeffrey F. Hamburger, Nuns as Artists: The Visual Culture of a Medieval Convent (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California, 1992), 67-68. |

| ↑37 | Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 158-60. See also Els De Paermentier, “Experiencing Space through Women’s Convent Rules: The Rich Clares in Medieval Ghent (Thirteenth to Fourteenth Centuries),” Women’s Feminist Forum 44, no. 1 (2008): 53-68, esp. 55-57. https://doi.org/10.17077/1536-8742.1709 |

| ↑38 | De Paermentier, “Experiencing Space,” 58, n. 15; the nuns considered their cloister a paradise, a foretaste of the eternal and heavenly afterlife. Philipus Probus remarked that clausura is the faithful guardian of virginity; “a woman ought to have either a husband, or a wall” cited in Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Space, 106-07. |

| ↑39 | Penelope D. Johnson, “The Cloistering of Medieval Nuns: Release or Repression, Reality or Fantasy?” Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women’s History, ed. Dorothy O. Helly and Susan H. Reverby (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1992), 30-38. As Johnson points out, nuns also visited their lovers and children outside the convent walls. |

| ↑40 | Johnson, “The Cloistering,” 33-36. The richest abbeys had impressive libraries such as the l’abbaye-du-Bois with its 16,000 volumes and Chelles that possessed 10,000 volumes in the eighteenth century. See Reynes, Couvents, 112 |

| ↑41 | Reynes, Couvents, 238-54; the nuns of Saint-Cyr, on the other hand, reverted to the strictest religious education (249-54). |

| ↑42 | See Nicky Hallett, “Philip Sidney in the Cloister: The Reading Habits of English Nuns in Seventeenth-Century Antwerp,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 12, no. 3 (2012): 88-116, esp. 99. https://doi.org/10.1353/jem.2012.0022 |

| ↑43 | The Perfectae Caritatas was penned by the Vatican Council on the renewal of religious life in 1950. See Margaret Brennan, “Enclosure: Institutionalising the Invisibility of Women in Ecclesiastical Communities,” Women Invisible in Church and Theology, Concilium 182, ed. Elizabeth Schüssler Fiorenza and Mary Collins (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1985), 38-48, esp. 44-45. Though Brennan uses this information to build a case for the patriarchy’s enforcement of the invisibility of women, some of the evidence is quite striking. For example, in the 1980s the Vatican Council decreed that the Discalced Carmelite nuns were to revive the constitution drawn up by St. Theresa in 1581. Even the active orders were prescribed “an enclosure appropriate to the character and mission of the institute.” |

| ↑44 | Edward T. Hall, Silent Language (New York: Doubleday, 1959), 57. |

| ↑45 | “Life of Mary Xaveria of the Angels: Carmelite convent of St. Helens, 211, as cited in Hallett, “‘So short a space of time,” 539-66, esp. 549, n. 47. |

| ↑46 | Hallett, “‘So short a space of time,’” 549-59. Though Hallett is speaking primarily of the Carmelite order and the visions of St. Theresa, the author’s superimposition of St. Augustine’s notion of time upon the nuns’ experience seems applicable to other early modern convent experiences of space and time. |

| ↑47 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, 21-24. See also Margit Thefrier, Women and Gender in the Early Modern Low Countries 1500-1750 (Leiden: Brill, 2019); Rapley, “Women and the Religious Vocation in Seventeenth-Century France,” 613-31; Strasser, “Early Modern Nuns and the Feminist Politics of Religion,” 529-54. |

| ↑48 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, 22. Like most other French convents, this monastery was destroyed during the French Revolution. |

| ↑49 | Silvia Evangelisti, “Monastic Poverty and Material Culture in Early Modern Italian Convents,” The Historical Journal 47, no. 1 (2004): 1-20, esp. 4-5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X03003480 |

| ↑50 | The nuns’ cells in this study are post-medieval so that the grill was a permanent feature dividing the sisters from the outside world, which included the administration of the sacraments. Campbell-Jonas, In Habit, 100, 166; McNamara, Sisters in Arms, 27-30, 342-63. |

| ↑51 | See Barbara Baert, “Echoes of Liminal Spaces: Revisiting Late Medieval Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries (A Hermeneutical Contribution to Chthonic Artistic Expression),” Antwerp Royal Museum Annual 2012 (2014/15): 9-45; Baert, Late Medieval Enclosed Gardens, esp. 7-37. See also Fiona J. Griffiths, The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), 134-63. |

| ↑52 | Woshinsky, Imagining Women’s Conventual Spaces, xi-xii. |

| ↑53 | McNamara, Sisters in Arms, 341-44. As McNamara notes, the affective meditation of the Cistercians was grounded in their identification with Christ’s humanity, which was the basis for their practice of compassion. Mary’s role in the redemptive agony of Christ made her the leading mediatrix between God and humanity; similarly, wealthy patrons called upon the nuns to intercede on their behalf with their prayers. |

| ↑54 | Baert, Late Medieval Enclosed Gardens, 4-19, n. 25; a threefold union occurs in the Enclosed Garden, that of God and flesh, the Church and Christ, and the nun and Christ. |

| ↑55 | “Lectio divina, Study, Meditation,” Service de Moniales, https://www.service-des-moniales.cef.fr/en/lectio-divina-study-meditation/ accessed 18 February 2020. |

| ↑56 | Evangelisti, “Monastic Poverty,” 5-7. |

| ↑57 | Melissa Katz, “Behind Closed Doors: Distributed Bodies, Hidden Interiors, and Corporeal Erasure in ‘Vierge ouvrante’ Sculpture,” Anthropology and Aesthetics 55/56 “Absconding” (2009): 194-221; Gertsman Worlds Within, 19-42, 149-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/RESvn1ms25608844 |

| ↑58 | Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 154-60, n. 58, citing Bernard of Clairvaux and Hugh of St. Victor, On the Cloister of the Soul. The heart and mind of the nun are identified with monastic enclosure. |

| ↑59 | Guido Hendrix, ed., Hugo de Santo Caro’s Traktaat ‘De doctrina cordis,’ 1 (Leuven: Peeters, 1995), 14 as cited in Baert, “Enclosed Gardens,” 15, n. 28. |

| ↑60 | Baert, “Enclosed Gardens,” 14-16. See also Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 88-125. |

| ↑61 | Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 116, n. 38, citing Raymond of Capua as cited by Richard Kieckhefer, Unquiet Souls: Fourteenth-Century Saints and their Religious Milieu (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 109. |

| ↑62 | Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 114-36; 150-60. |

| ↑63 | My thinking is deeply influenced by the scholarship of Baert on the Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries. See Barbara Baert and Hannah Iterbeke, “Revisiting the Enclosed Gardens of the Low Countries (Fifteenth Century Onwards): Gender, Textile, and the Intimate Space as Horticulture, Textile 1 (2017): 1-26, esp. 11-13. |

| ↑64 | Baert and Iterbeke, “Revisiting the Enclosed Gardens,” 8-16; Hamburger, Nuns as Artists, 181-90; Marc Libert, “Le travail dans les couvents contemplatifs féminins,” Revue belge de Philologie et d’Histoire 79, no. 2 (2001): 547-55; Marie Lezowski and Laurent Tatarenko (dir.), Façonner l’objet de devotion chrétien. Fabrication, commerce et circulation (XVIe-XIXe siècle), Archives de sciences sociales des religions 183, 2018, https://journals.openedition.org/assr/38797. https://doi.org/10.3406/rbph.2001.4531 |

| ↑65 | Mary Carruthers, “The Concept of Ductus, or Journeying Through a Work of Art,” Rhetoric beyond Words: Delight and Persuasion in the Arts of the Middle Ages, ed. Mary Carruthers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 190-213. See also Baert, “Echoes of Liminal Spaces,” 18-19. |

| ↑66 | Sheenagh Pietrobruno, “Technology and its Miniature: The Photograph,” Belphégor (Littérature populaire et culture médiatique) 15, no. 1 (2017): 1-16. https://doi.org/10.4000/belphegor.896 |

| ↑67 | See Jeffrey Hamburger, “The Visual and the Visionary: The Image in Late Medieval Monastic Devotions,” Viator 20 (1989): 161-82, esp. 171. Further, structural metaphors emphasize our shape of experience of the material world. See Stephanie Downes, Sally Holloway, and Sarah Randles, “A Feeling for Things, Past and Present,” in Feeling Things: Objects and Emotions through History (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 8-23. |

| ↑68 | Stewart, On Longing, 44-54; See also Simon Garfield, In Miniature: How Small Things Illuminate the World (Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2018), 1-63. |

| ↑69 | Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, 160. See also Stewart, On Longing, 43-47. |

| ↑70 | Stewart, On Longing, 44-54. |

| ↑71 | Stewart, On Longing, 65 |

| ↑72 | Julian Yates, Error, Misuse, Failure: Object Lessons from the English Renaissance (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 47-48. |

| ↑73 | This plaything would have had pedagogical benefits, in that the habit and mores of the order were exhibited in the miniature cells. See Rapley, “Women and the Religious Vocation,” 613-31. The practice of recruiting such young girls to monasteries was harshly criticized in the eighteenth century and culminated in Diderot’s La Religieuse. |

| ↑74 | As the abbot Musson observed about the roles of Mary and Martha: “de crainte que l’esprit ne soit diverti par l’entretien du corps, et que la solicitude de Marthe aux choses de la terre ne détourne Marie de sa contemplation.” Abbé Musson, Les Ordres monastiques: Histoire extraite de tous les auteurs qui ont conservé `a la postérité ce qu’il y a de plus curieux en chaque ordre, 3 (Berlin, 1751), 259 as cited in Reynes, Couvents, 106. |

| ↑75 | Hazel R. Markus and Shinobu Kitayama, “Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation,” Psychological Review 98, no. 2 (1991): 224-53, esp. 246. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.98.2.224 |

| ↑76 | Markus and Kitayama, “Culture and the Self,” 225-31, 245-48. |

| ↑77 | Katherine Nelson, “Meaning in Memory,” Narrative Inquiry 8, no. 2 (1998): 409-18, esp. 412-13. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.8.2.12nel |

| ↑78 | Jens Brockmeier, “Introduction: Searching for Cultural Memory,” Culture & Psychology 8, no. 1 (2002): 5-14, esp. 7-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X02008001616 |

| ↑79 | Brockmeier, “Introduction,” 12. |

| ↑80 | Brockmeier, “Introduction,” 9. |

| ↑81 | Kenneth J. Gergen, “Mind, Text, and Society: Self-memory in Social Context,” The Remembering Self: Construction and Accuracy in the Self-narrative, ed. Ulric Neisser and Robyn Fivush (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 78-104. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511752858.007 |

| ↑82 | Romans 12:4-6. |

| ↑83 | Gergen and Gergen, “Narrative and the Self,” 35-40. |

| ↑84 | Sue Williams Silverman, “Memoir with a View: The Window, as Motif and Metaphor, in Creative Nonfiction,” The Writer’s Chronicle (Oct./Nov. 2014): 1-9. |

| ↑85 | Jocelyn Wogan-Browne, “Chaste Bodies: Frames and Experiences,” Framing Medieval Bodies, ed. Sarah Kay and Miri Rubin (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1994), 24-42. |

| ↑86 | Wogan-Browne, “Chaste Bodies,” esp. 28-30. Although the author is referring to an anchoress, the body metaphor applies to all nuns. The anchoress, however, would have submitted to bloodletting four times a year as part of her regime. |

| ↑87 | José Maria Salvador-Gonzalez, “The Symbol of Bed (Thalamus) in Images of the Annunciation of the 14th-15th Centuries in the Light of Latin Patristics,” International Journal of History and Cultural Studies 5/4 (2019): 49-70. https://doi.org/10.20431/2454-7654.0504005 |

| ↑88 | Salvador-Gonzalez, “The Symbol of Bed,” 49. |

| ↑89 | Albert Châtelet, Rogier van der Weyden (Rogier de le Pasture) (Paris: Gallimard, 1999), 43, n. 24. The same author proposes that the presence of the bed signifies the mystical union of the Virgin and the Holy Spirit in another publication. Cf. Albert Châtelet, Rogier van der Weyden: Problèmes de la vie et de l’œuvre (Strasbourg: Presses Universitaires, 1999), 97. |

| ↑90 | Salvador-Gonzalez, “The Symbol of Bed,” 62-68. See Psalm 18. |

| ↑91 | Hamburger, Artists as Nuns, 177-211. |

| ↑92 | The audience for the miniature cells is assumed to have been the nuns’ families, special patrons, or members of the upper echelon of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. |

| ↑93 | Bonaventure cited by Longpré, “La théologie,” VI.2, 70, as cited by Jeffrey F. Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1990), 72-73, n. 21. |

| ↑94 | For the history of the individual orders, see my longer study of the cells in the collection of the Trésors de Ferveur: The Nun’s Cell: Mirror, Metaphor, and Memoir in Convent Art (forthcoming). https://www.sistersofcarmel.org/carmelite-order-history/. |

| ↑95 | My daughter, what have you come to do here! Oh how happy and tranquil is the soul in the poor and charming refuge; Only God; A penitent soul finds her sweetness here, everything pleases, everything enchants her. The cross is her bliss; I wish to climb the Calvary in the steps of my sweet Savior as did our mother Theresa to sacrifice my life for him every day to win over our hearts. |

| ↑96 | The time keeping device, a sablier in French, is found in many of the cells and assumes a number of different configurations. |