Debra Higgs Strickland · University of Glasgow

Recommended citation: Debra Higgs Strickland, “The Female Presence on the Hereford World Map,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/LZBT9907.

I wrote this study with Rachel Dressler’s interests in mind, and I am honored to include it in this special issue of Different Visions with admiration for her scholarship and with gratitude for her support over many years. I would like to thank Elizabeth Robertson for feminist inspiration and scholarly guidance, and I am grateful to Matt Strickland for his photography and valuable suggestions for improving an earlier draft. I would also like to thank the Hereford Cathedral Library staff and the Mappa Mundi Trust for generous supply of images and promotion of my research. Finally, I extend thanks to journal readers for their humane and helpful feedback on successive drafts, and to the editors for their encouragement and provision of the interactive digital image of the Hereford Map available in the online version.

Figure 1. Hereford World Map, Hereford, c. 1300, Hereford Cathedral Treasury (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

The Hereford World Map is the largest and most magnificent of the extant medieval mappaemundi (Fig. 1).[1] Measuring over five feet high and four feet across,[2] it was painted in bright colors and gold across the smoothed and whitened hide of a single hefty calf. Even in its current faded and darkened state, it still dazzles the viewer with hundreds of tiny, Gothic-style architectural icons marking the world’s cities surrounded by hundreds of other figures and topographical markers familiar to medieval Christian viewers from the ‘popular bible’, the bestiary, the Alexander tradition, the Wonders of the East, and other sources transmitted across European visual and literary cultures.[3] As on other medieval world maps, the circular space of the inhabited world, or ecumene, on the Hereford Map is surrounded by Ocean and subdivided into the three known continents of Asia, Africa, and Europe separated by the Mediterranean and other major waterways. Unlike a modern map, the top designates the direction of east. Scores of Latin inscriptions identify countries, regions, cities, peoples, animals, monsters, mountains, seas, rivers, and islands. Additional passages in Anglo-Norman French gloss three large narrative scenes positioned outside the ecumene that depict a Last Judgement extending across the top, Caesar Augustus’s command to his three surveyors in the lower left corner, and in the lower right corner, an equestrian rider with his huntsmen and one (or more) greyhounds.[4]

Figure 2. Hereford World Map with locations of figures discussed (additions by the author).

This sizable figural collective reveals a pervasive masculinity: male ecclesiastical headgear, flat chests, beards, tonsures, testicles, and penises abound. Even the rider’s prancing horse is emphatically male, and numerous other small male human and non-human figures are distributed across the world’s continents. Indeed, the Map’s entire visual field is enframed, patrolled, and occupied by males. However, on closer inspection, some twenty securely identifiable female figures can be spotted across the landmasses, with the most semiotically charged ones positioned along the Map’s main vertical and horizontal axes (Fig. 2). The most important of these is the Virgin Mary, centrally located at the Map’s summit in the gabled space of the Last Judgement, directly beneath the judging Christ, at whom she gazes imploringly while baring her breasts in a dramatic, intercessory gesture. To her right (our left), a veiled handmaiden reverently bears Mary’s golden crown. Following the Map’s vertical axis downward and moving slightly south (right) of the central, circular icon of the walled city of Jerusalem, a siren presents her mirror. Due east (up) from the siren, Lot’s wife looks back mournfully at the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah. Positioned north (left) on this same horizontal axis is Noah’s ark, with Noah’s wife on board. Further afield, on the southern periphery of Africa (far right), a headless female Epiphagus, with her eyes in her shoulders, stands beside the curved Nile with other monsters, including a female Psylli. Scattered around the Map’s waterways and across its landmasses are additional female monsters, birds, and beasts, whose gender is indicated by dress or was otherwise known from popular myths, legends, or bestiary stories. In this study, I ask: What was the function of this female collective for the Hereford Map’s contemporary medieval viewers, and how did it expand the work’s didactic utility?

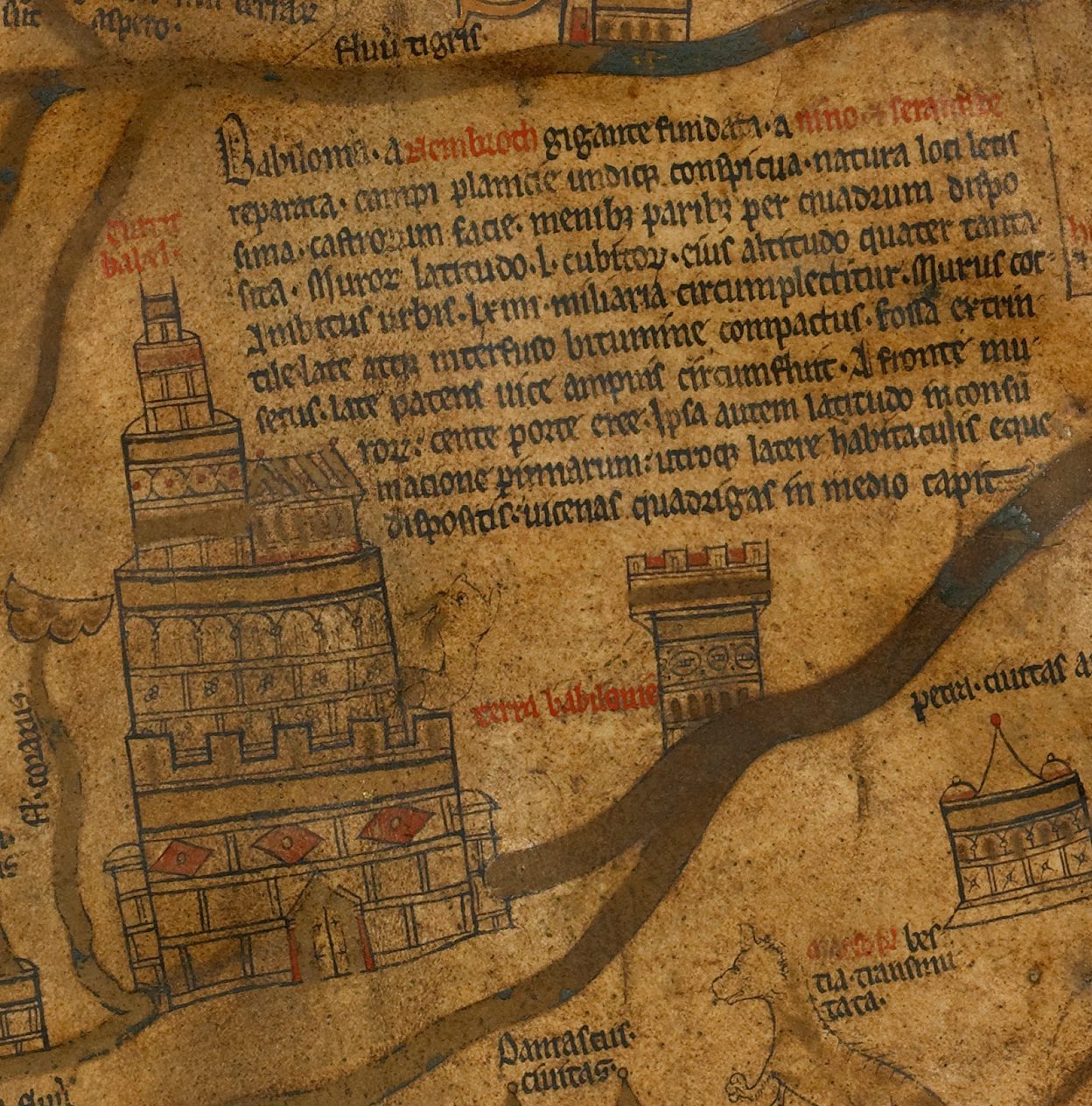

Figure 3. Tower of Babel, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

A first clue is provided by the visual fulcrum for the ecumene’s four axial females of Eve, the siren, Lot’s wife, and Noah’s wife. It is the Tower of Babel (turris babel), whose immense size casts over them the shadow of sin (Fig. 3). Positioned almost exactly between Paradise and the central Jerusalem, and just north (left) of the evil city of Babylon (babilonia), it is the largest architectural icon on the entire map and the one with the lengthiest inscription.[5] Medieval Christian exegetes interpreted this outlandish structure, ‘the top thereof may reach to heaven’ (Gen. 11:1), as a monument to human pride that prompted God to visit upon its builders linguistic confusion and geographical dispersal “upon the face of all countries” (Gen. 11:9),[6] especially well-suited to representation on a world map. In learned Christian texts, pride was routinely identified as the root of all sin,[7] a lesson reinforced for the ordinary faithful in sermon exempla.[8] More pertinent to the present study, pride was identified as a sin to which women were especially prone, manifest in their excessive concerns with appearance, dress, and possessions.[9] As a consequence, references to women’s pride and related sins of vainglory, gluttony, and avarice were woven into the fabric of both religious and secular medieval literature, including fabliaux, romance, and guides to courtly love. At the same time, patristic teachings aimed at heterosexual men extolled the virtues of virginity versus the (necessary) evil of marriage to women.[10] By 1300, a negative climate was thus fully established for reception of the Hereford Map’s female presence, whose axial biblical figures were notorious across medieval art and literature. Compared to the humility and moral perfection of the Virgin Mary towering over them, the sins of the Map’s worldly women loomed ever larger, highlighted by the female constellation organized around a primordial monument to pride.

Downplaying their moral significance, Ingrid Baumgärtner has argued that some of the female figures depicted on the Hereford Map and other medieval mappaemundi effectively ‘other’ foreign women by referencing Classical myths and contemporary travel accounts that highlight European norm-challenging female behaviors.[11] Without discounting this important aspect of contemporary reception, I nevertheless suggest in this study that the received moral meanings of the Hereford Map’s females are precisely what allow them to point beyond their individual stories to a universal Christian misogyny, which by 1300 was fully developed in all corners of cultural production. I hope to show that the Map’s female figures embody the so-called feminine traits—pride, disobedience, and sexual misconduct––whose disruptive dangers are further amplified by their relative placement and other cartographical strategies. As the divine foil for a world of sinful women, even the intercessory figure of Mary, I argue, has a role to play in the work’s misogynist agenda; and in the last section, I consider the implications of the Map’s patronage from this perspective. With reference to this best-known example, my larger art historical goal is to call attention to the gendered dimension of medieval world maps and to the power of cartography to ratify medieval misogynistic ideologies.

In recent years, the topic of medieval misogyny has received sustained scholarly attention across disciplines, including art history, providing fruitful analytical pathways that have readjusted our focus from elite male perspectives to those of wider populations inclusive of girls and women.[12] However, as Kate Manne has recently argued, the definition and philosophical parameters of misogyny are complex and contested,[13] and manifest in different ways over time. Adopting Manne’s definition of misogyny as “the system that operates within a patriarchal social order to police and enforce women’s subordination and to uphold male dominance,”[14] I interpret the Hereford Map’s female iconography as a misogynist worldview presented as a view of the world, one that earns the artistic genre of the mappaemundi a legitimate place in feminist debates. Accordingly, I identify the Hereford Map as an active agent in the medieval economy of misogyny, in which patriarchal Christian theological and social agendas were mutually reinforced.

But how would this have worked in practice? Scholars have proposed that over time, the Hereford Map’s functions were multiple: decorative, commemorative, didactic, devotional, and liturgical. Located in an important cathedral and one of England’s most popular pilgrimage sites owing to its possession of the relics of St. Thomas Cantilupe (c. 1218-1282),[15] it was encountered by an international, multilingual, and multi-gendered audience of all ages and from all walks of life. Some could read its numerous Latin and Anglo-Norman inscriptions, many others could not.[16] Its use as a didactic tool has been explored in relation to the scholastic training of the élite and the moral edification of the laity;[17] and as a form of “informal catechesis” for pilgrims.[18] It is clear from these investigations that whether the viewer was educated or unlettered, the work’s many verbal and visual complexities would have been an extremely challenging experience that required some form of mediation.

Informed by Conrad Rudolph’s ground-breaking research, I propose that this mediation took the form of cathedral guides tasked with providing medieval visitors with a range of information, from the entertaining to the instructional.[19] The assumption of guides assigned to the Hereford Map is especially warranted as a vital intellectual bridge between audiences of different knowledge levels and an artwork of immense complexity. Medieval audiences were primed to recognize many of the Map’s figures and places from prior exposure to books, sermons, plays, and church decoration, but they still would have required substantial help negotiating its many other pictorial and geographical details to gain a proper Christian understanding of their social and spiritual meanings. As Rudolph has emphasized with respect to other complex works of medieval art,[20] there were interpretative choices to be made, and ecclesiastical authorities would have had a stake in ensuring that viewers made the right ones. While necessarily speculative for Hereford Cathedral as for many other medieval pilgrimage sites, activities documented at other places indicate that on-site male guides could be ‘elite’ (highly educated) or ‘nonelite,’ and were drawn from all social levels, including clerks, priests, bishops, monks, friars, abbots, and even members of the laity.[21] At Hereford Cathedral, elite guides might have logically included the resident canons who formed the core of administration, worship activities, and hospitality.[22] In lieu of written evidence of guides here, Scott Westrem has detected traces of their activities on the Map itself: the architectural icon that once marked the city of Hereford has been almost completely rubbed away, he hypothesizes, from multiple fingers indicating that ‘we are here’.[23] In addition, one of the Map’s main inscriptions, which addresses the reader in Anglo-Norman French, begins by acknowledging such mediation: “Let all who have this history—or who shall hear, or read, or see it—pray to Jesus in his divinity…” (emphasis added).[24] I suggest, therefore, that the gap between the Hereford Map’s meanings and their reception was almost certainly bridged by masculine authorities whose theological, if not social, understanding of women and their sins was an important component of their moral landscapes that could be mapped onto the work’s female figures for explication to an international audience.

Figure 4. John Carter, drawing of Hereford Cathedral altarpiece, c. 1784, London, British Library, Add. MS 29942, fol. 148r (photo: © British Library Board).

As I have already intimated, the Hereford Map’s extraordinary figure of the Virgin Mary must stand at the forefront of any analysis of the work’s female presence. Of course, Mary’s central significance at this time and place extends well beyond the Map. Hereford Cathedral was dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin and St. Ethelbert, with an independently administered Lady Chapel and expansive liturgy,[25] and an otherwise fully developed Marian program.[26] Most significantly, as Marcia Kupfer has recently affirmed, the Hereford Map originally formed the central panel of a Marian triptych whose (now lost) side panels were painted with images of the angel Gabriel and the Virgin Annunciate, as recorded by John Carter in a drawing dated to around 1784 (Fig. 4).[27] Special devotion to Mary at Hereford was otherwise fully in tune with the burgeoning cult in late medieval England.[28]

Germane to the Map’s female landscape, Mary, the ever-virginal mother of Jesus, was consistently presented by medieval preachers and writers as an unattainable role model for all other women, and the ultimate foil for their ‘feminine sins’. As such, she was a vital, if counterintuitive, resource in the medieval misogynist’s toolkit.[29] I therefore begin with Mary, her antithetical counterpart, Eve, and two of the Map’s exotic beasts to explain how the backstories, cartographical placement, and conceptual interrelationships of these figures reaffirmed women’s proper place in medieval Christian society and encouraged men to keep them there.

AVE – EVA

Figure 5. Mary and handmaiden, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

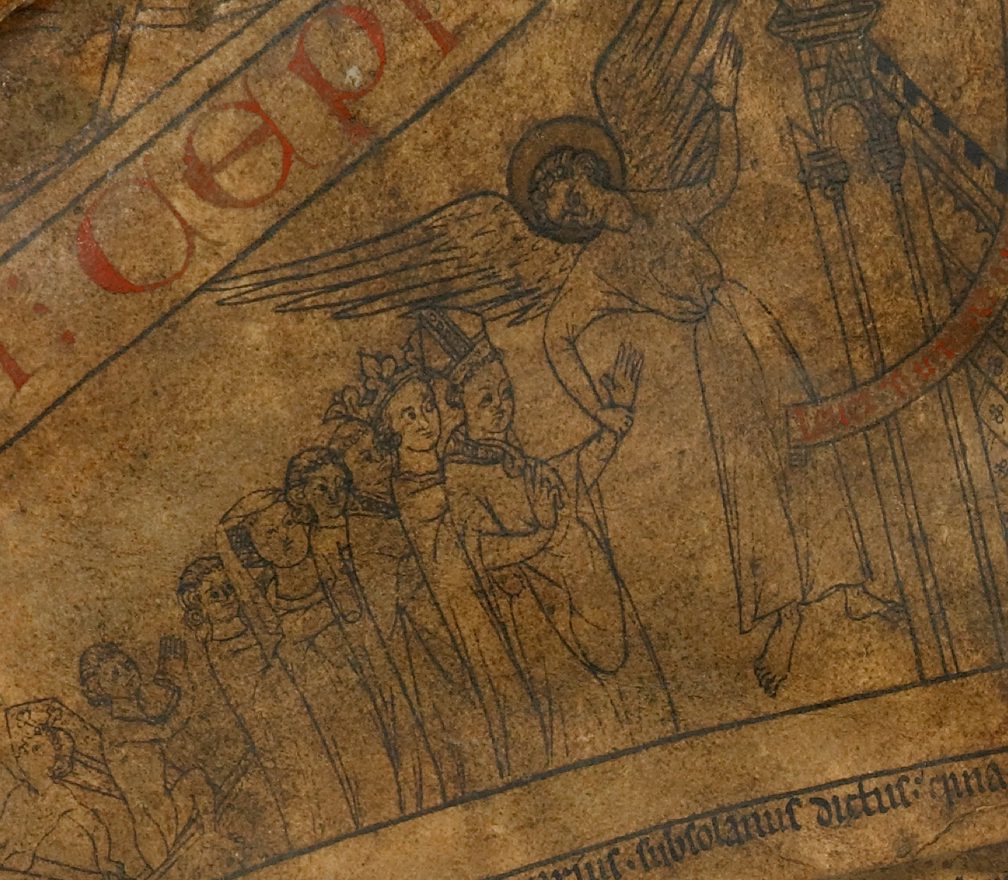

As a continuation of the Marian theme established by the Annunciation imagery on the altarpiece’s side panels, Mary is positioned at the Map’s summit, just below Jesus, surrounded by the unfolding Last Judgement. She is appealing to the hieratic figure of Jesus in an unusually eye-catching way by holding open her robe to expose both of her breasts as she voices the petition inscribed on the adjacent scroll (Fig. 5). It is true that the presence of Mary in a late medieval Last Judgement scene is entirely conventional, but it is also true that a depiction of her in this context with both breasts bared is rarely found in English art, much less on mappaemundi.[30] Meanwhile, on her left (our right), a handmaiden is holding—or perhaps offering—a crown,[31] further enlarging the female dimension of the narrative scene, which otherwise includes the requisite lineup of the hierarchically-organized, fully clothed blessed and the undifferentiated, naked damned led by angels and devils, respectively, with a bestial hellmouth yawning at the ready on the far right.

Mary’s role as intercessor in the Map’s Last Judgement scene has been thoroughly examined in relation to the familiar iconographic traditions on which it is based,[32] and so I attend here only to its unconventional aspects. Looking up at the inscrutable Christ, who does not return her gaze, Mary’s exposure of her female anatomy is glossed by the Anglo-Norman inscription on the adjacent scroll, in which her maternal bond to Jesus underwrites her plea for mercy on behalf of a sinful humanity:

See, dear son, my bosom, in which you took on flesh,

And the breasts at which you sought the Virgin’s milk;

Have mercy—as you yourself have pledged—on all those

Who have served me, since you made me the way of salvation.[33]

Medieval Christian understanding of Mary’s maternal bond was enriched by the semiotic relationship between milk and blood, with reference to Christ’s wounds, according to the belief that milk was a highly refined version of blood.[34] This relationship, however, does not fully obtain in the Hereford Map scene, where it is compromised by Mary’s self-exposure, lack of any visual reference to maternity—she is not depicted nursing the Christ child— and juxtaposition to the handmaiden holding a crown that calls attention to Marian majesty rather than motherhood. Moreover, Mary’s exposed breasts link her visually to the even more exposed Eve, to say nothing (yet) of the fully naked Lot’s wife, Epiphagus, Psylli, and the bare-breasted siren. As clarified in the petition quoted above, bare breasts are a sign of Mary’s life-sustaining powers. But because they are bared here for viewers as well as for Christ, they also signal her femininity and, I suggest, provide a catalyst for contemplation of the associated ‘female sins’ embodied by the Map’s non-virginal females organized across the world below.

Figure 6. Rinoceros and monoceros, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

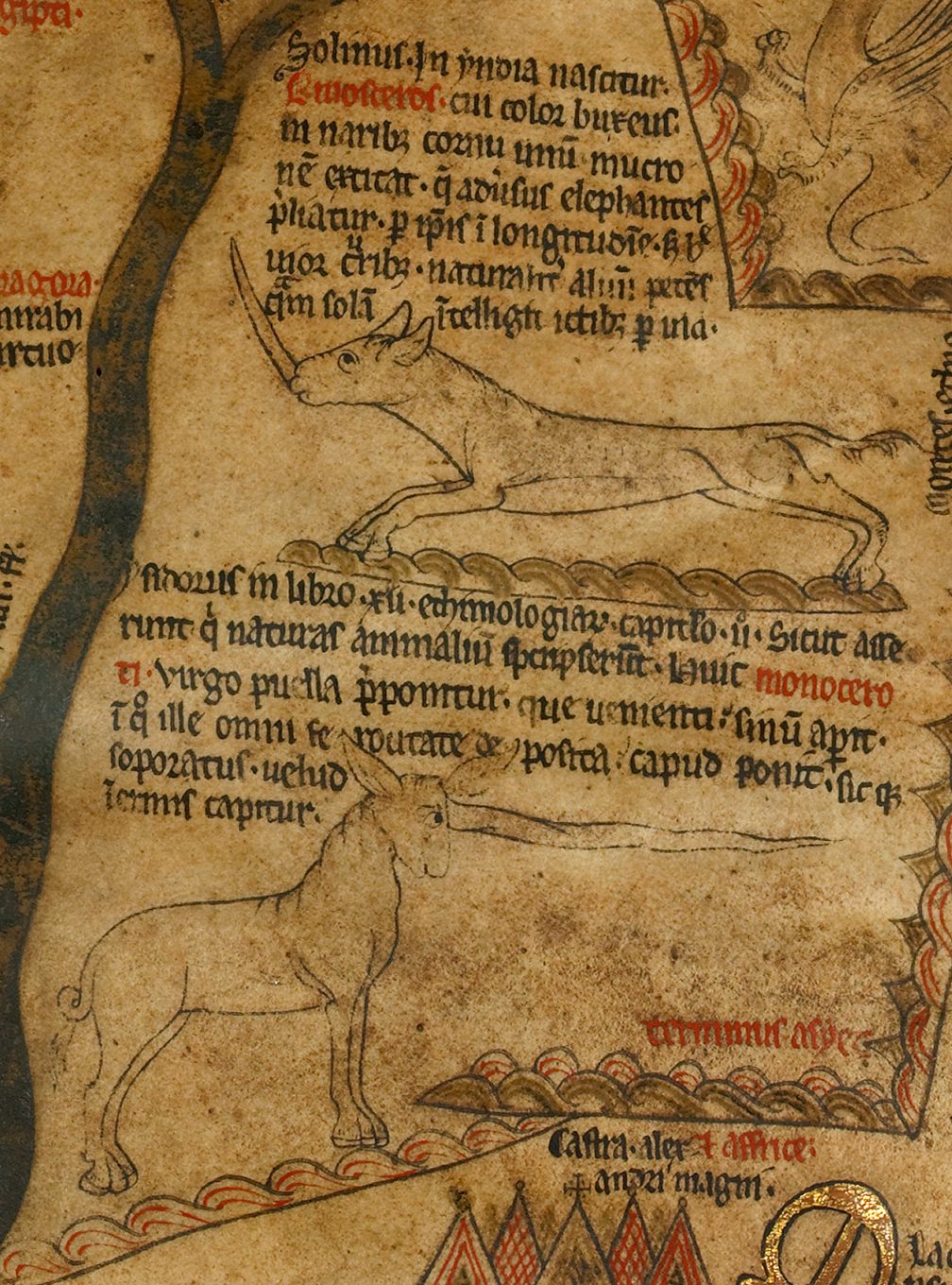

Two of the Map’s exotic animals can also be viewed in relation to Mary—and to misogyny. Positioned far southwest (below and to the right) of the Last Judgement scene, between the two branches of the Nile in Africa, two unicorns stand one above the other, rendered in profile and facing opposite directions (Fig. 6). The top one is inscribed rinosceros and the lower one, monocerti, interchangeable names for one-horned beasts described in the Latin bestiaries, with a Christological moralization normally attached to one (sometimes designated unicornis) but not the other.[35] On the Map, the monoceros, with the longer horn, is accompanied by an inscription that summarizes the familiar bestiary story but for one significant addition: “…a virgin girl is brought before this monoceros, and on his approach she bares her breast, on which he rests his head—all ferocity abandoned—so that, stupefied, he is captured like a harmless creature” (emphasis added).[36] There is no reference to breast-baring in the Latin bestiary unicorn entries, but in the Map’s inscription, it points to the breast-baring Virgin Mary at the summit. From here, it also evokes the Marian dimension of the more expansive Latin bestiary account of the unicorn / monoceros, which identifies Jesus Christ as “the spiritual unicorn” (spiritualis unicornis) who descends into a virgin’s womb “through flesh taken from her.”[37]

Beyond Mary, the Map’s monoceros could point in a misogynist direction in view of the newer meanings attached to the unicorn in the Bestiaire d’amour (Bestiary of Love), a secular reworking of the Latin bestiary composed by the Amiens canon and trouvère, Richard of Fournival (d. 1260).[38] Several vernacular translations of this work evidence its pan-European popularity,[39] and local familiarity is attested by an Anglo-Norman copy illustrated with penwork drawings made around 1300-1349 for the parish church of St. Laurence in Ludlow, about twenty-five miles north of Hereford.[40] In this patronizing bestiary-cum-love-plea aimed at an anonymous woman whose sexual favors the author hopes to obtain, the unicorn is attracted by the “sweet smell of maidenhood,” just as he, Richard, was “captured by smell, and my lady has continued to hold me since by smell, and I have abandoned my own will in pursuit of hers.”[41] However, in the feminist rebuttal to this work known as the Response du bestiaire,[42] with allusions to the horn, the author identifies the unicorn as a figure of male flattery, to be feared by women “for I know well that there is nothing so wounding as fair speech . . . nothing can pierce a hard heart like a soft and well-placed word.”[43] In this more figurative connection, the Map’s monoceros and rinoceros work together. The horn’s piercing power is the salient feature of the rhinoceros, whose inscription reminds viewers of its sharpness and ability to wound an elephant.[44] And as if to show up the rhino’s horn, the monoceros displays his much longer one, whose phallic connotations recall the thirteenth-century Rochester Bestiary’s celebrated miniature of a naked virgin cradling in her lap a unicorn sporting a horn of comparable length (Fig. 7.).[45] Finally, the cartographic placement of the Map’s two unicorns activate a misogynist message in which their extreme geographical distance from Mary (i.e., between southern Africa (far right) and the heavenly summit) mimes the moral distance between Mary and all other women—unicorn-baiting virgins not excluded—whose seductive powers are dangerous entrapments for men.

Figure 7. Virgin and unicorn, Rochester Bestiary (Rochester? 2nd quarter, 13th c.), London, British Library, MS Royal 12.F.XIII, fol. 10v (photo: © British Library Board).

This moral distance is further enshrined in the Map’s symbolic geometry by means of other artistic and cartographical strategies, beginning with the juxtaposition of the large figure of Mary and the tiny figure of Eve (see Fig. 2). Intensified by this hierarchical scaling, the top-down axial alignment of Mary with Eve triggers the conventional theological association of AVE – EVA, a medieval shorthand for Mary as the salvific antithesis of the sinful Eve, and a popular theme in art of this period.[46] Eve is in fact depicted with Adam twice, in representations of the Transgression and Expulsion (Fig. 8). In addition to reminding viewers of Eve’s pivotal role in salvation history, this double representation inaugurates the Map’s extended misogynist messaging by calling special attention to her disobedience, which by this time, like pride, was an essentialized female trait. In contemporary plays and the popular bible, female disobedience to their male minders began with Eve, was reprised by Noah’s wife and Lot’s wife, and was the identifying behavior of at least one of the faraway Monstrous Peoples. On the Hereford Map, these figures together highlight the spiritual and social dangers of a woman’s refusal to defer to her husband.

Figure 8. Eve and Adam, inside and outside of Paradise, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

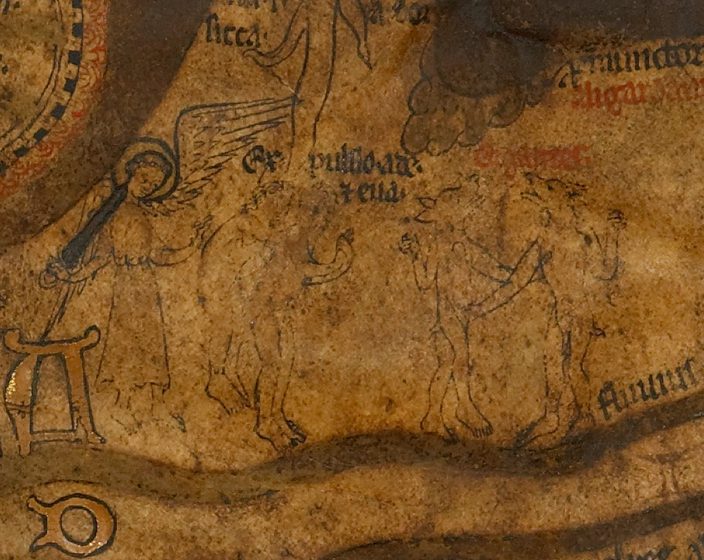

Disobedient Wives

From a misogynist perspective, Eve, the first woman—whose inferiority to Adam was established by the very circumstances of her creation,[47] —was the first disobedient wife. Close scrutiny of the Map’s heavily abraded Transgression scene inside the walled and gated space of the circular Paradise reveals a tiny, naked Eve accepting the fruit from the serpent’s mouth while a naked Adam, standing behind her, eats it.[48] That was the understood order of things: Eve sinned first, and afterward victimized Adam by persuading him to do the same. Accordingly, Eve’s culpability was greater,[49] even though in the Map’s version, only Adam is depicted actually eating the fruit. Eve appears again with Adam in the Expulsion scene situated immediately outside the Paradise walls. At the base of the legendary Dry Tree (arbor balsa id est arbor sicca),[50] an angel armed with a silver sword waves away the protoplasts, their backs bent in shame and under the weight of the words that proclaim their punishment (expulso adae et eua).[51] Although this scene is also badly abraded, Adam can be seen leading the way, looking back mournfully towards Paradise, with Eve following close behind,[52] as they make their way south (right) along the path of exile marked by the Hypanis River (fluuvius yppanis).[53]

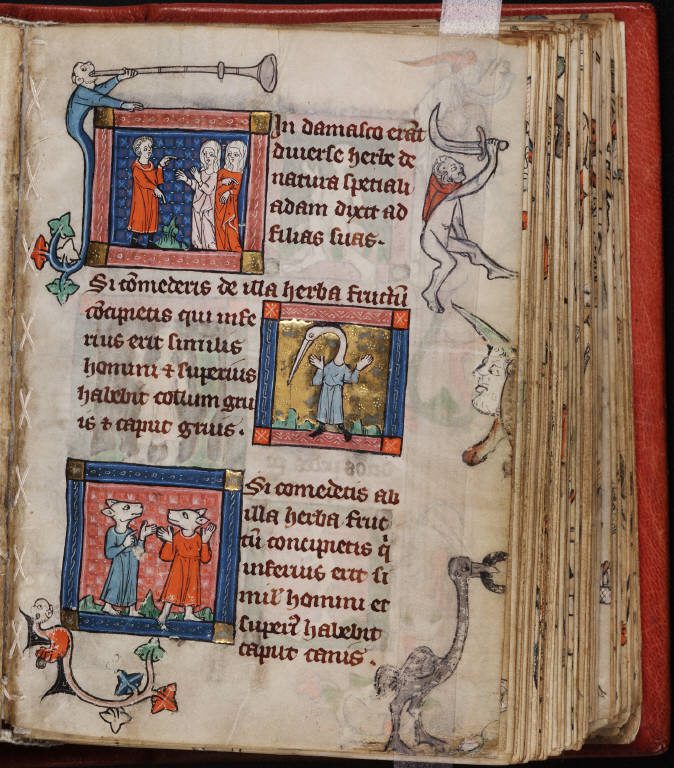

Figure 9. Adam warning his daughters; crane-headed man; dogheads, Rothschild Canticles (Flanders or the Rhineland, c. 1300), New Haven, Yale University Library, Beinecke MS 404, fol. 113r (photo: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University).

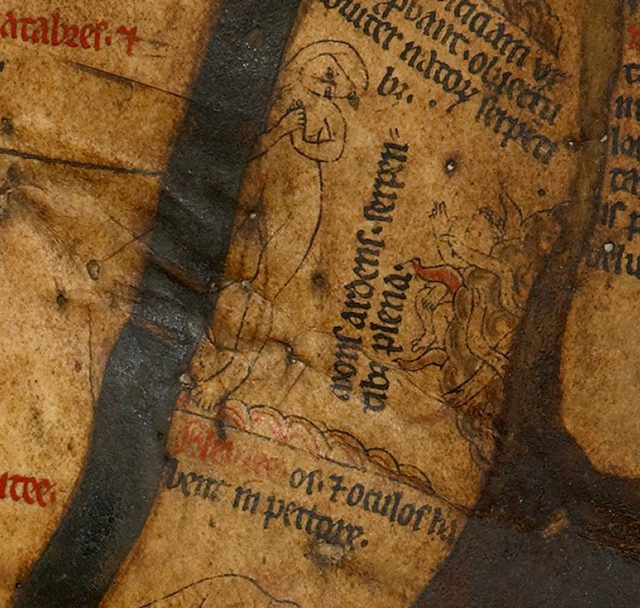

God’s commandment to Adam and Eve to “increase and multiply” (Gen. 1:28) then goes forth as a masculine project initiated by Adam and his sons (Cain, Abel, and Seth). However, by the time Adam turned 930, he had reportedly fathered additional “sons and daughters” (Gen. 5:3, emphasis added). A well-known apocryphal account of Genesis explains that these daughters, like their mother, disobeyed masculine instruction not to eat something. In this case, Adam warned his daughters not to eat certain forbidden herbs, but they ate them anyway, and were subsequently punished with misshapen offspring.[54] A pictorial series in the Rothschild Canticles, exactly contemporary with the Hereford Map, begins with a narrative scene of Adam warning his daughters followed by sequential ‘portraits’ of their monstrous children, which include a pair of clothed, conversing Dogheads (Fig. 9).[55] Could knowledge of this story have influenced contemporary interpretation of the pair of conversing Dogheads (gigantes) standing to the immediate right of the expelled Adam and Eve on the Hereford Map (Fig. 10)?[56]

Figure 10. Eve, Adam, and Dogheads, Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

This monstrous pair, in fact, can do an impressive amount of misogynist work as a visual gloss on the Adam and Eve story. Besides literally embodying the sins of Adam’s daughters, their nakedness and gender differentiation parodies the protoplasts and their postlapsarian relationship. The current state of the drawing makes it impossible to tell whether the Doghead on the left was supplied with a vulva, but the one on the right has a clearly rendered penis. Both are gesturing with open mouths, as though engaged in animated conversation––or more likely, barking––while holding round objects evocative of forbidden fruit. Both have human hands, and the male is grasping the female’s crotch, perhaps a reference to Transgression-triggered lust––or to more garden-variety male aggression. For those in the know, the male Doghead’s dominance might also have been interpreted as corroboration of learned theological opinion that the cynocephali are human, with claims to culture and civilization,[57] in which women must be controlled.

Figure 11. Lot’s wife, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

In the medieval popular bible, Eve’s disobedience is just the first installment of a recurring pattern of female insubordination. The story of Lot’s wife, whose husband was instructed by angels to not look back at the place from which he and his family were commanded to flee (Gen. 19:12-29), inspired another cartographical representation of female defiance. As indicated earlier, Lot’s wife is situated on the Hereford Map’s main horizontal axis, south (right) of the Tower of Babel on the winding path of Exodus,[58] looking back disobediently at the wicked cities of Sodom (Sodom civitas) and Gomorrah (Gomor civitas) marked by twin architectural icons (Fig. 11.).[59] The adjacent inscription, “wife of Lot, changed into a pillar of salt,”[60] forecasts her petrifying punishment. In late medieval art, Lot’s wife is usually represented as either a fully clothed woman or as a salt-colored (white or brown), inanimate statue.[61] Here, by contrast, she is depicted as a still-living, naked woman with long, loose hair, carefully rendered breasts, and a mournful expression, which keeps the focus on her disobedience rather than her punishment. Viewed in relation to the exposed and downcast state of the Eve figures at the top of the Map’s main vertical axis, the figure of Lot’s wife strengthens the association of female nakedness with disobedience and remorse that is echoed around the ecumene.[62]

Madeline Caviness has analyzed the misogynist dimensions of Lot’s Wife’s story, arguing that it served as a warning to women against the ‘transgressive gaze’, and that it also exemplifies the patriarchal gesture of not-naming women extended to Lot’s daughters and to Noah’s wife and daughters-in-law, among other biblical women.[63] From a misogynist perspective, women looking at things proscribed by men is a concerning form of female transgression because it thwarts male efforts to keep them in the dark. This is a fair assessment of what happened to Lot’s wife and before her, to Eve, both of whom gained knowledge they were not supposed to possess. Strictly speaking, both proscriptions were issued not to the women themselves but to their masculine minders—and yet for medieval exegetes, artists, authors, preachers, religious, viewers, and listeners, disobedience in both stories was always gendered female.

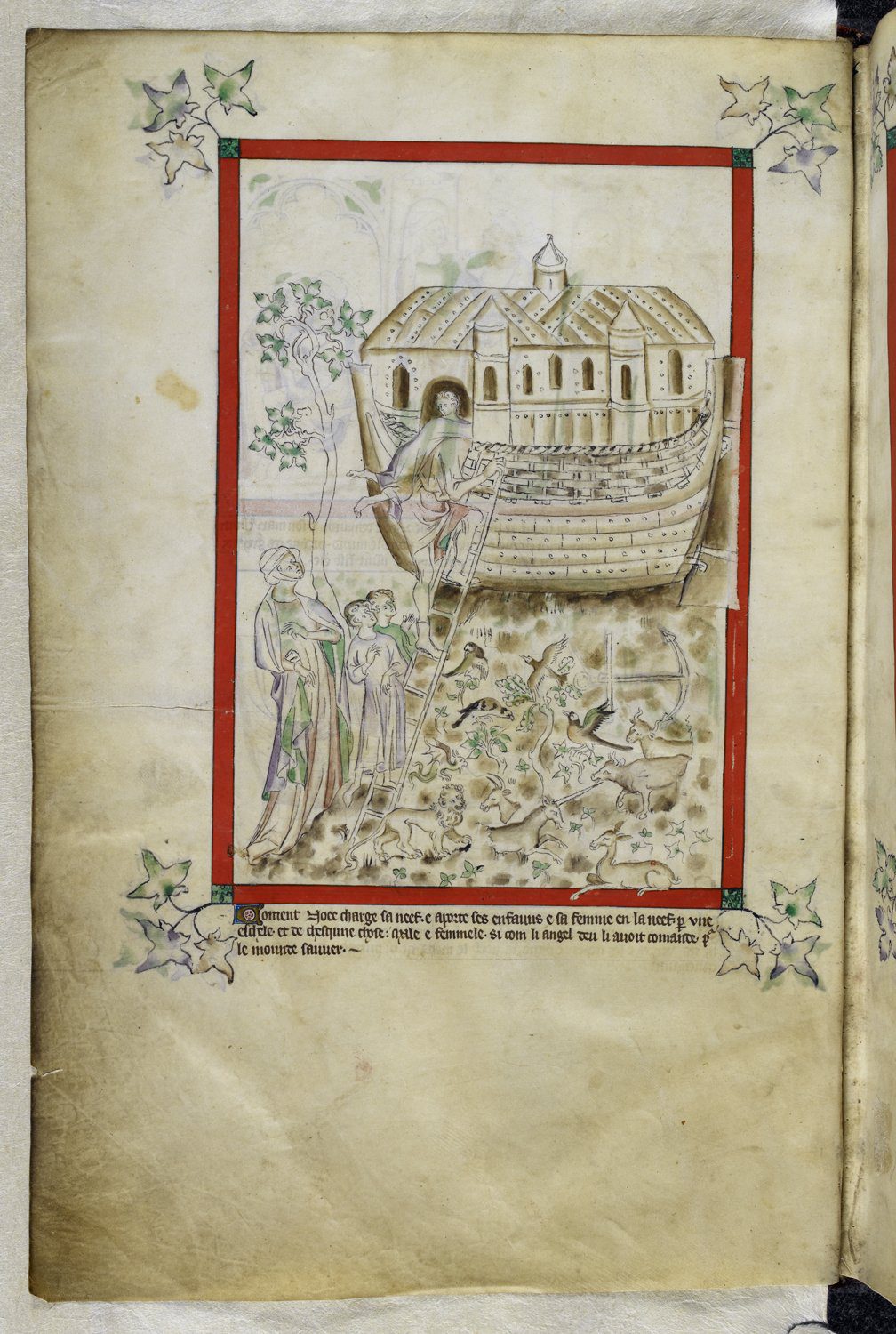

Figure 12. Noah’s ark, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

To the north (left) of Lot’s wife, on the same horizontal axis, the viewer encounters the anchored vessel that houses a third biblical woman defined by her husband and by her disobedience, this time of a more domestic sort (Fig. 12). In Genesis, Noah’s wife is mentioned only as part of the ark’s cargo (Gen. 6:18, 7:7, 7:13); we learn more about the dove and the raven (Gen. 8:6-13) than we do of her. However, during the later Middle Ages, her character was substantially developed in Christian apocrypha and especially in the Flood plays performed in England from at least the mid-fourteenth century.[64] In these later reimaginings, Noah’s wife is transformed into a major protagonist, occasionally as the unwitting means by which the Devil tries to sabotage Noah’s mission, but more consistently as a disobedient, loud, disruptive, and sometimes physically violent scold who refuses to board the ark, either out of concern for her friends or because she is preoccupied with her spinning. In her critical analysis of the Flood plays, Jane Tolmie has suggested that for medieval audiences, spinning identified Noah’s wife as a high-status working woman, with the dangerous social implication that her work was just as important as Noah’s.[65] In the Chester and York plays, she has to be dragged on board by two of her sons,[66] and in the Towneley Play, her challenging behavior transforms her husband into a frustrated wife-beater, an image that troubles Noah’s exemplary status as God’s handyman and custodian of Creation, and also chimes with modern feminist readings of male violence against women as an exercise of control.[67]

Identifications of the figures inside Noah’s ark on the Hereford Map cannot be confirmed with absolute confidence owing to their abraded state, but Scott Westrem has identified Noah’s wife and daughter-in-law among them.[68] Although I read the one figure as Noah rather than the daughter-in-law,[69] I support the identification of the other figure as Noah’s wife on visual grounds and in view of her popularity in late medieval England, and by the logic of incorporating her into the Map’s axial female presence. In English art, there is iconographical precedent from the eleventh century onward for inclusion of Noah’s wife in narrative scenes of building or loading up the ark,[70] and contemporary with the Hereford Map are her appearances in ark scenes in the Ramsey Abbey Psalter and the Queen Mary Psalter (Fig. 13).[71]

Figure 13. Noah’s wife refusing to board the ark? Queen Mary Psalter (London / Westminster or East Anglia? between 1310 and 1320), London, British Library, MS Royal 2 B VII, fol. 6v (photo: © British Library Board).

On the Map, Noah’s ark is located in the Armenian Mountains in Asia Minor, accompanied by an inscription affirming that it came to rest here, as recorded in Genesis (Gen. 8:4).[72] I identify the profile figures visible in its five windows, from left to right, as: (1) two birds of prey, (2) Noah and Noah’s wife (3) a lion, (4) a sheep and two other mammals, and (5) three snakes.[73] Although Noah’s head is the only one fully visible, consistent with her larger-than-life reputation, his wife’s partially visible one is substantially bigger and she wears a larger and more elaborate headdress.[74] As the stories and plays attest, she may be subordinate to Noah, but she is no shrinking violet.

Like Lot’s wife, Noah’s wife was not given a name by the Genesis author, but the perceived need for one is confirmed by the more than one hundred names she was assigned by later writers![75] For example, Peter Comestor in his Historia named her Phuarphara.[76] Another popular name was Noema, whose closeness to ‘Noah’ suggests that Noah and his wife were understood to be brother and sister, thus ensuring the ‘purity’ of postdiluvian incest.[77] In the Flood plays, however, she is referred to simply as uxor or uxor Noe, and the evidence of performance practice indicates that she, like other female characters, was portrayed by a male actor dressed as a woman. This tradition has been identified as an important mediating factor in the audience’s responses to dramatic presentations of misogynistic abuse, especially when the actors addressed the audience directly.[78] In the Towneley Play, for example, the man playing Noah warns the men in the audience of the need to control their wives’ wayward tongues.

Yee men that has wifis,

Whyls thay are yong,

If ye luf youre lifis,

Chastice thare tong.

Me think my hert ryfys,

Both levry and long,

To se sich stryfys

Wedmen emong;

Bot I,

As haue I blys,

Shall chastyse this.[79]

Performed by male actors in drag, Noah’s wife in the vernacular plays epitomized the stereotypical sharp-tongued, disobedient woman of art and literature that collapsed the distance between the biblical past and the domestic experiences of late medieval audiences. Similarly, Noah’s wife inside the ark, Eve inside and outside of Paradise, and Lot’s wife looking back toward Sodom and Gomorrah provided opportunities for viewers of the Hereford Map to contemplate these figures’ negative roles in salvation history as the direct result of their defiance of male authority, and to consider the enduring risks of this sinful behavior in the here-and-now of the fourteenth century.

Monstrously Disobedient Wives

The example of the Dog-headed, potential alter-egos of Adam and Eve discussed above demonstrates that the Map’s evocations of disobedient females reach beyond Scriptural authority and the medieval popular bible to the world of monsters. That these disparate traditions should share common ideological ground becomes more plausible in view of medieval religious and secular writings that identify women with—or even as— monsters. Authoritative Classical teachings about women’s supposed biological inferiority were expanded in medieval medical and pseudo-scientific treatises that defined menstruation as Eve’s punishment, declared female libido uncontrollable, viewed the womb as a voracious animal with a mind of its own, and promoted gynophobic views of the female body as a monstrous and (to men) dangerous aberration, if not a card-carrying monster.[80] Today, a growing body of scholarly work has examined the special signifying powers of female monsters qua monsters and as instruments of ‘othering’ women and nonbinary people in medieval Christian societies.[81] Less attention has been paid to female monsters as embodied medieval ideas whose multivalent anatomical features point beyond the bodies of women to the behavioral traits women supposedly embody. I suggest that the latter function is performed by at least two of the Map’s female monsters, both popularized by Pliny and Isidore of Seville, and otherwise familiar to medieval audiences from bestiaries, sermons, travel accounts, and other types of artworks.

Figure 14. Psylli, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

The female Psylli (Philli), located along the Nile on the south (right) side of the Map is a member of a monstrous group notable for their immunity to snakebite (Fig. 14).[82] She is rendered naked with faintly visible female breasts, wearing only the wimple signifying a married woman.[83]) The inscription above her head explains that “the Philli test the chastity of their wives by exposing their newborns to serpents.”[84] Having just undergone (and apparently failed) this masculine-mandated ordeal, the Psylli is looking mournfully at her child under attack by multiple snakes on a burning mountain.[85] Her posture, exposure, and dejected expression closely parallel those of Lot’s wife positioned at the end of a long northeast diagonal (above and left), except while Lot’s wife covers her shame with her hands, the Psylli is wringing her hands in shame and despair. Like Adam’s wife, Lot’s wife, and Noah’s wife, the Psylli wife has defied male authority. From a misogynist perspective, her adultery is a product of her unbridled female lechery, but most importantly, her punishment—the death of her child, fathered by another man—preserves the honor of her Psylli husband.

Figure 15. Epiphagus and Blemmye, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

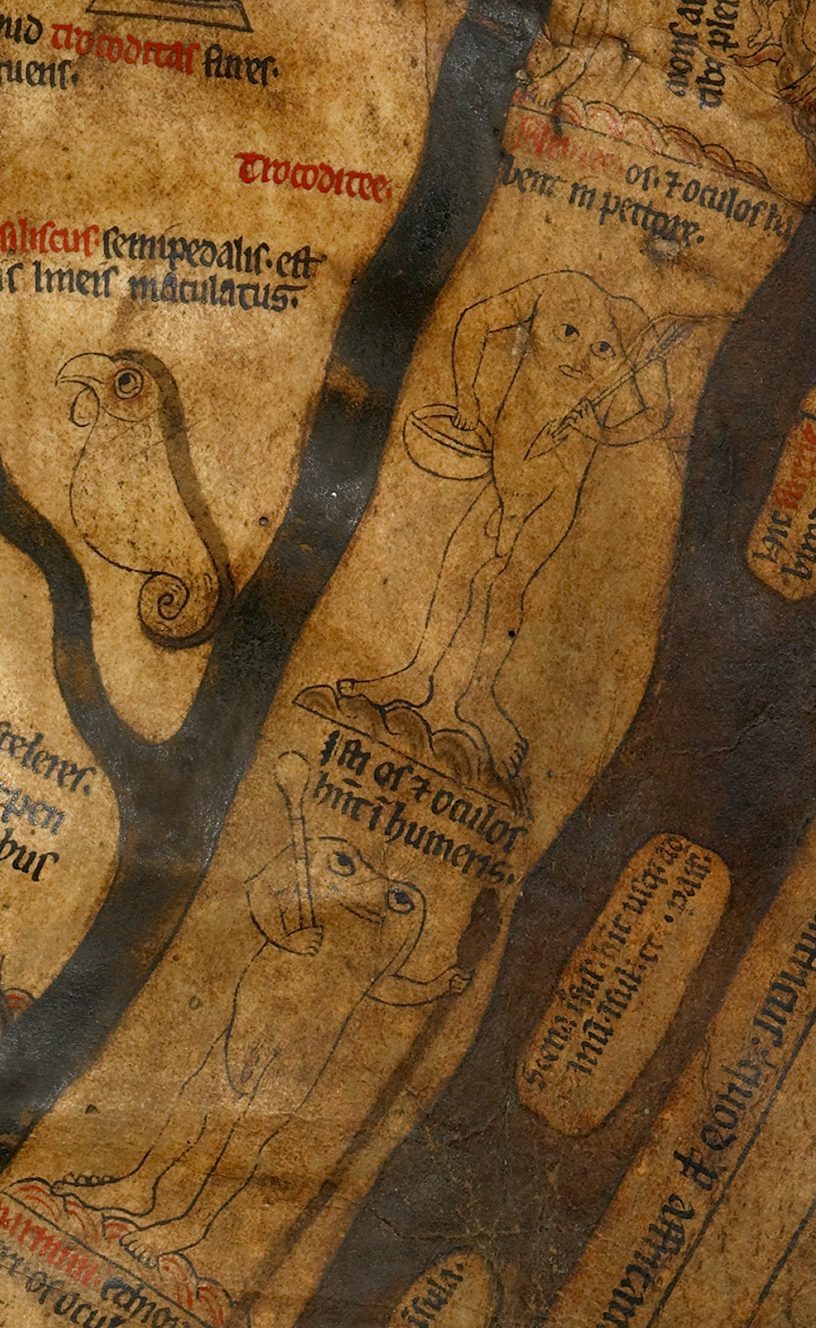

West (down) along the Nile from the unfortunate Psylli stands the headless Epiphagus with her eyes in her shoulders, representative of another monstrous people, and another wife of sorts (Fig. 15). That is, while most Epiphagi are presumed male and sometimes even supplied with a penis,[86] this one displays a carefully rendered vulva that still bears traces of the bright red pigment that would have given it high visibility.[87] In her right hand, she holds a baton and in her left hand, a distaff, the standard attribute of wives since Eve, whose first postlapsarian occupation was spinning.[88] Across medieval art, the distaff had both positive and negative connotations, depending on whether it was operated by the Virgin Mary (good), Eve (not so good), or Noah’s wife (bad); or wielded as a weapon by a female scold (very bad).[89] In the case of the Epiphagus, domestic subordination is suggested by her placement directly below a male Blemmye, her headless husband, towards whom she has fixed her shoulder-eyed gaze. The Blemmye, holding an arrow and a bowl, gazes (from the face on his chest) not at the Epiphagus but at the viewer, with his penis pointing downward to his wife’s identifying inscription, “These ones have their mouth and eyes in their shoulders.”[90] The Blemmye’s pendant inscription reads “The Blemmyes have their mouth and eyes in their chest.”[91] He gets a name, she does not; he gazes at us, she gazes at him; he stands over her.

The female Epiphagus breaks the rule, otherwise upheld on the Hereford Map, which pairs femininity with disobedience. Eve, inside Paradise, looks on as her husband, Adam, commits the fatal mistake after her example and at her urging; only after the two are cast out of Paradise do they perform their remorse. As an Adam and Eve parody, the Hereford Map’s female Doghead is the apparently irksome wife of the male, and they both owe their genesis to Adam’s disobedient daughters. The Map’s other two biblical women, Lot’s wife and Noah’s wife, also disobeyed male instruction, as did the adulterous Psylli wife. Only the fully exposed Epiphagus seems to know her place. Collectively, these figures suggest that wifely disobedience was an especially troubling behavior because it directly challenged male authority and control. Moreover, their cartographical placements bear witness to the importance of male domination in every geographical and temporal sphere, from the domestic to the exotic, on earth as in heaven; and the exceptions prove the rule: like the Epiphagus, Mary defers to her husband—a.k.a. her father, son, and masculine Creator—and like the Psylli, she wears a wife’s wimple.

The Siren’s Warning

Figure 16. Siren, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

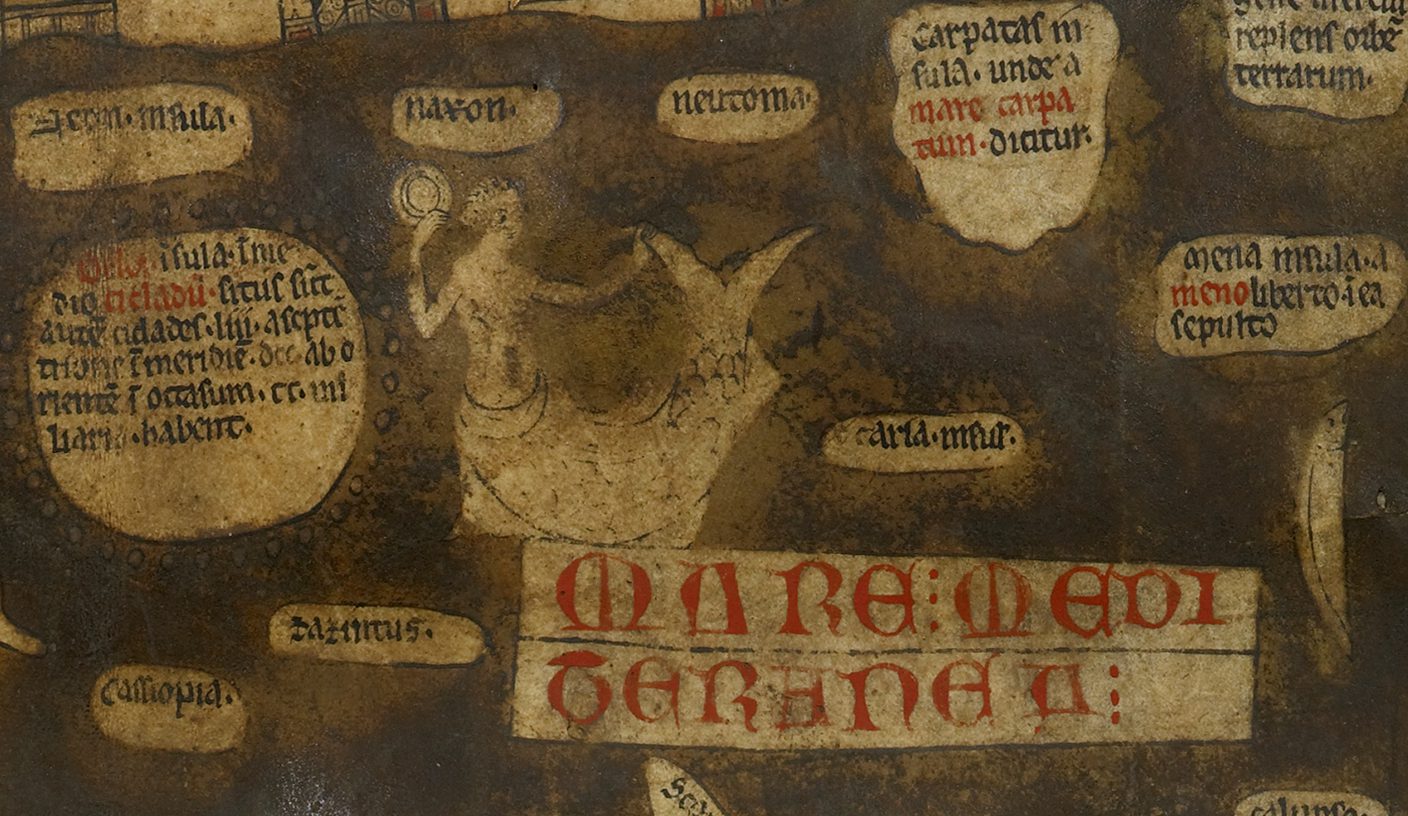

In the Hereford Map’s female collective, second in didactic significance only to the Virgin Mary, I believe, is the monstrous siren (Fig. 16). Like Mary, she occupies a prominent cartographic position, along the same vertical axis, in the middle of the Mediterranean and equidistant from the architectural icons marking Jesus’s Jerusalem (above) and the Pope’s Rome (below) (see Fig. 2). The siren is further emphasized by her proximity to the ecumene’s largest rubricated inscription—the only one written in capital letters—which does not refer to her, but rather to the sea in which she is situated (MARE MEDITERANEA).[92] She is half-woman, half fish, with short curly hair, holding her mirror in one hand and in the other, the left fork of her fishtail, towards which she gazes.[93] Like Mary high above, the siren’s breasts are fully exposed, but unlike Mary, she is no virgin. She is, like Mary, a type of intercessor, but with privileged access not to God, but to the world, in which she enables viewers to locate themselves by inviting them to see their own reflections in her outward-turned mirror. Based on current understanding of the Map’s late medieval display, the siren’s gesture would have been at eye level, helping to ensure that her invitation was received by all.[94]

By 1300, the siren was a ubiquitous figure in public church art, with additional examples in Hereford Cathedral. Pilgrims arriving at the cathedral’s north porch encountered among its thirteenth-century carved voussoir figures a siren assessing the exposed buttocks of a male bagpiper positioned directly above (Fig. 17);[95] and certain local clerics sat on (or leaned against) a siren suckling a lion on one of the choir’s misericords.[96] In the bestiaries, the siren is the quintessential figure of female deception, lust, and murder, infamous for lulling sailors to sleep by singing, having sex with them, and then tearing them to pieces, as vividly illustrated in facing bas-de-page scenes in the Queen Mary Psalter.[97] According to the bestiarists, the siren symbolizes those deceived by luxuries and pleasures, but she also points to a social reality: “In truth [sirens] were prostitutes (meretrices) who led their lovers to poverty and thence are said to cause shipwrecks. They are said to have wings and claws, because love both flies and wounds”.[98]

Figure 17. Siren and bagpiper, inner north porch, Hereford Cathedral (photo: Matt Strickland).

In a medieval Christian worldview, the real-life prostitutes referenced in the bestiary siren moralization were shunned for their sinfulness, but they were also to be pitied as ordinary women incapable of restraining their insatiable libidos.[99] As Ruth Mazo Karras notes, the term, meretrix—often better translated as ‘whore’—in medieval literature could refer not only to paid sex workers but more broadly to any woman engaged in nonmarital sex, even with only one man.[100] The dangers such sexually active women posed to men were carefully articulated by Robert Mannyng of Brunne (c. 1275-c. 1338) in his popular didactic work, Handlyng Synne:

Full foul is that public one

Who is common to all, indeed;

Therefore, whatever is in your thought,

Common women take you not,

(…)

One [reason] is, she may take your brother,

Father, or relation, as well as another.

Another, for quarrels and foul strife,

You may, through her, lose your life.

The third is the worst defilement:

Lepers, people say, use them;

And he who takes them in that heat

May soon lose the purity of his body.

Much woe, then, it is to take such,

For the sake of these three problems;

And much may be that woman’s moan,

For she shall answer for every one

Who has done any sin with her

On Judgment Day, the day of wrath.[101]

These verses are especially suggestive for medieval understanding of the Hereford Map’s siren, a temptress positioned near the center of the world, will pay the price at the Last Judgement depicted high above. Alternatively, the siren with her mirror signaled the remedy for female sexual misconduct: according to certain miracle tales, a whore devoted to the Virgin Mary could be saved no matter how or how badly she had sinned.[102] On the Map, the visual pendant for the siren in this connection is, of course, the figure of the merciful Mary.

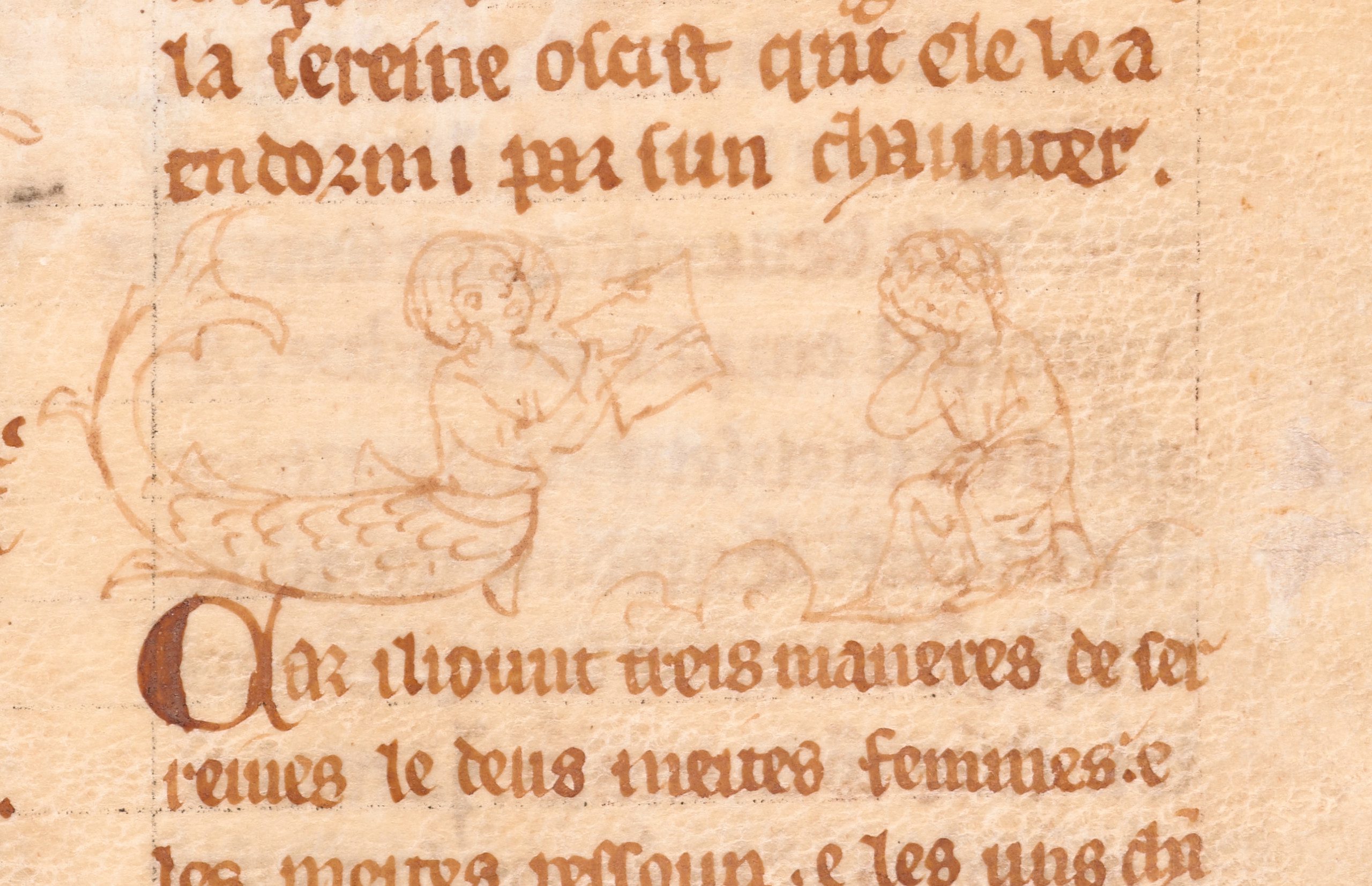

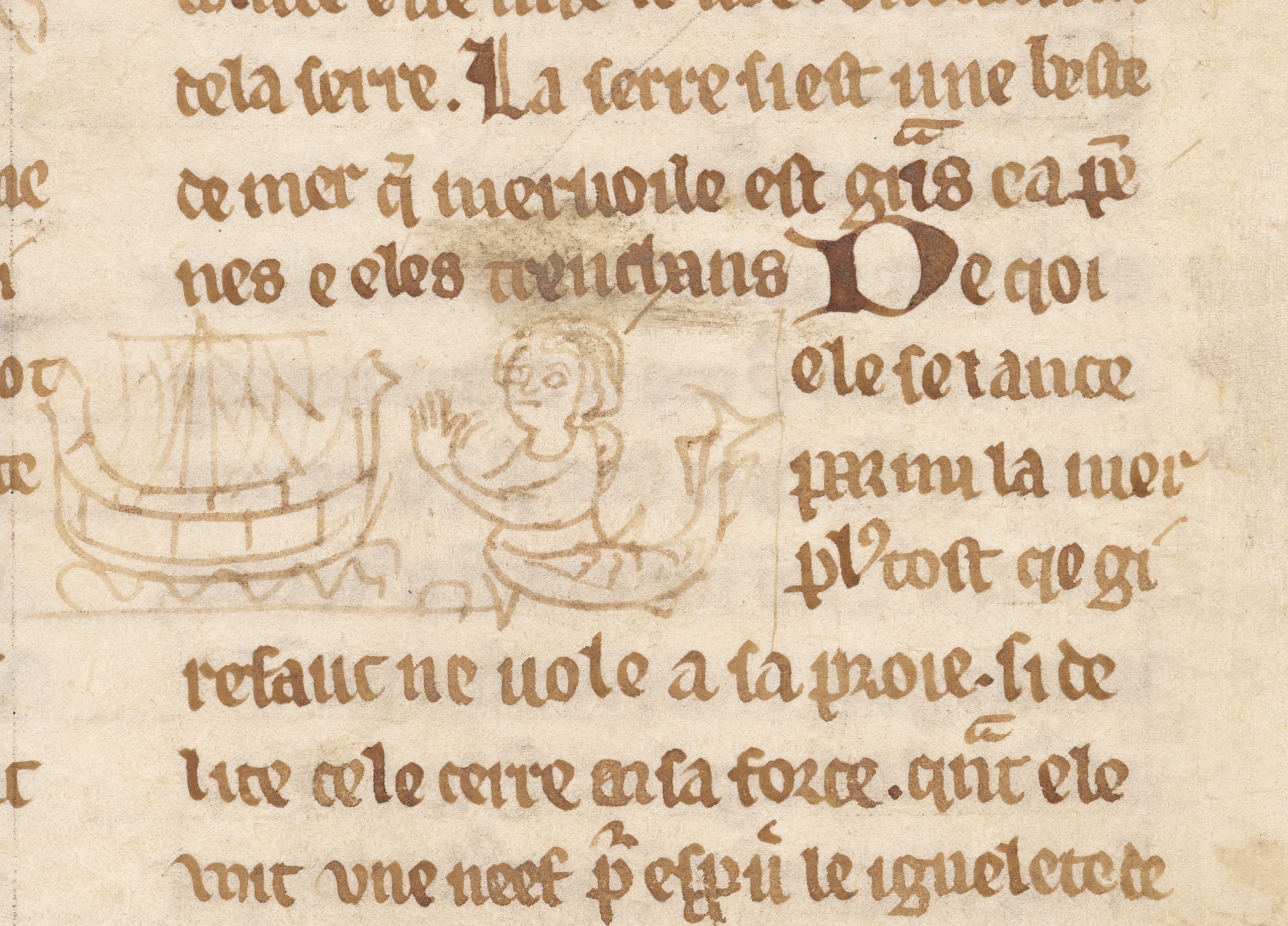

The Latin bestiary’s references to worldly love and prostitution made the siren an indispensable inclusion in the misogynist Bestiaire d’amour, in which Richard claims he was treacherously killed by the lady’s love, like the man killed after placing his trust in the seductive, singing siren.[103] The author of the Response, however, turns the tables by identifying the siren’s seductive song with Richard’s deceptively sweet words, which are dangerous and not to be trusted.[104] The siren is depicted twice in the Ludlow copy of the Bestiaire d’amour.[105] In the first drawing, a clothed, fish-tailed siren gestures towards the book she is holding before a man whom she has lulled to sleep, presumably by singing—or possibly by reading (Fig. 18).[106] She is depicted a second time alongside the description of the serra, a ferocious, winged fish who races against ships, for which the artist has substituted a clothed and fish-tailed siren, this time gesturing before an empty ship (Fig. 19).[107] Operating independently from their texts, these drawings may be viewed together as a two-part allegorical image of a woman’s destruction of men, the first showing how she does it (with irresistible voice or words) and the second affirming her success: the ship is literally ‘unmanned’. In this local copy of the Bestiaire, it seems, the male artist has had the last word.

Figure 18. Siren and man, Bestiaire d’amour, from a miscellany, Ludlow, c. 1300-1349, London, British Library, MS Harley 273, fol. 73r (photo: © British Library Board).

Figure 19. Siren and ship, Bestiaire d’amour, Harley 273, fol. 78r (photo: © British Library Board).

On the Hereford Map, too, the siren’s danger is clear and present: “the voluptuous siren flaunting her carnal mirror”[108] tempts viewers to gaze at themselves, thereby letting down their spiritual guard. This reading aligns with an understanding of the siren as a figure of worldly distraction––most immediately, for the Map’s equestrian rider, who gazes upward in her direction from its lower right corner (see Fig. 2). In her erudite analysis of the Hereford Map’s theological themes of speculum and speculatio, Marcia Kupfer has linked the siren, her mirror, and the rider’s gaze to comments on women and lust in the Tractatus moralis de oculo (Moral Treatise on the Eye), a popular guide for preachers composed by Peter of Limoges in Paris around 1275-89. In it, Peter explains that each of the five senses is vulnerable to lust’s assault, personified as a woman’s eyes. Thus, hearing is captured by the siren’s song, and sight by the “bright mirror” of the female body, so that “when someone who is a fool looks at it, it sometimes transfixes him in his tracks spiritually and leads him to forget the heavenly things which he should pursue.”[109] The Hereford Map, then, offered pilgrims a choice: the path to salvation by way of the intercessory Virgin Mary, or the road to perdition via the allure of the siren. The implications of both choices are clarified in the Last Judgement scene at the summit, and both paths begin with exposed female breasts.

The Men—and Women?—Behind the Map

In this final section, I consider the Map’s patronage and how it might have influenced the content or reception of its female presence. Do the documented proclivities of the men associated with the Hereford Map’s creation and display shed any additional light on its misogynistic messages and their reception? More speculatively, might the Map’s female presence have extended to female patronage?

I begin with what is known. One of the Map’s main Anglo-Norman inscriptions, partially quoted earlier, identifies its maker as one Richard of Haldingham and asks viewers to pray to Jesus (but not Mary) on his behalf.[110] Circumstantial evidence extends the Map’s patronage to Bishop Richard Swinfield (d. 1317), on whose watch it was created in tandem with his protracted efforts to secure the canonization of his beloved predecessor, Bishop Thomas Cantilupe (d. 1282), which was finally accomplished in 1320, three years after Swinfield’s death.[111] Given Swinfield’s close association with Cantilupe and the Map’s subsequent role in pilgrimage experiences, thirteenth-century witness accounts of St. Thomas’s misogyny, which was considered excessive even by contemporary standards, are highly germane. One section of Thomas’s canonization dossier reports that he so feared women’s dangerous wiles that he excluded his own three sisters as overnight guests, and he even refused to kiss one of them when she visited him at Bosbury to congratulate him on his bishopric.[112] The author of his seventeenth-century vita, by contrast, presents his misogyny as a virtue, for example, in a hagiographical set piece describing his sexual temptation by a beautiful woman who crawled into bed with him one night (from whom he escaped by jumping out the other side), which follows an equally conventional proclamation of his devotion to the Virgin Mary.[113] These attested traits provide a thematic link between the Hereford Map and the saint’s cult in which it originally functioned, and also reaffirm the central importance of its intercessory figure of Mary.

In spite of these strong leads, scholars agree that the Map’s patronage remains uncertain and that its Richard of Haldingham inscription provides an incomplete account of its creation.[114] Still, that inscription cannot be discounted, and importantly, it suggests that the Map itself might yield additional patronage clues. For example, Marcia Kupfer has recently identified the golden ‘R’ and ‘S’ letters in the Map’s all-encompassing M-O-R-S (Death) inscription with the name, Richard Swinfield (see Fig. 1).[115] I have provisionally identified another visual reference to patronage in the Last Judgement scene’s handmaiden holding Mary’s crown (see Fig. 5). This figure has been all but overlooked by previous critics who presumably have considered her just another part of the Last Judgement furniture. However, because the presence of such a figure in a Last Judgement scene is unusual, and because she occupies a position of honor on Mary’s right side, I propose to read her as commemoration of a female patron, whose devotion to Mary in life has earned her the high honor of serving Mary in heaven.

Figure 20. Tomb of Joanna de Bohun (c. 1327; restored 1940), Lady Chapel, Hereford Cathedral (photo: Matt Strickland).

In lieu of written evidence of female patronage of the Hereford Map, were there any local women of means whose circumstances make them plausible candidates? I believe the most promising candidate is Joanna de Bohun (d. 1327), also known as Joan Pugenet or ‘The Lady Kilpeck’, who was a special benefactress of Hereford Cathedral and a member of the extended de Bohun family, which included prominent patronesses of the arts.[116] Although there is no documented connection between Joanna and the Hereford Map, her importance at Hereford Cathedral is otherwise attested by her fine effigy tomb, installed in a recess in the north wall of the Lady Chapel, where she founded a chantry (Fig. 20).[117] Loveday Lewes Gee has observed that burial, especially of a woman, in such a prestigious position within a major cathedral was unusual, as patrons and founders’ families were normally buried in the choir; and that burial in a Lady Chapel, especially one situated at the east end of the building, was especially desirable owing to its closeness to the church’s relics and its association with Mary’s intercessory and protective services.[118] Beyond its obvious Marian associations, the Lady Chapel in Hereford Cathedral accrued additional prestige as the location in 1349 of St. Thomas Cantilupe’s new shrine. It is also the first documented location of the Map, which is known to have been displayed here by the 1680s,[119] located here before or after the installation of Joanna’s tomb is unknown. Arguably, the most telling sign of Joanna’s special status is the fact that hers is the only woman’s tomb from this period in Hereford Cathedral, which otherwise houses contemporary tombs of knights, clergy, and especially bishops.[120] Like the handmaiden on the Map, Joanna’s tomb effigy is a figure of modesty, with her head covered by a wimple and veil rather than a more fashionable headdress appropriate to her social station. As Rachel Dressler has shown, such modest dress conforms to expectations for women’s effigies of this period,[121] helping to maintain a focus on the piety of the deceased rather than on her sartorial finery, medieval women’s supposed obsession with the latter being one of the sticks with which they were perpetually beat in misogynistic theological tracts and sermon screeds.[122]

Joanna de Bohun’s special devotion to the Virgin Mary is affirmed not only by her tomb’s position in the Lady Chapel but also by the image originally painted behind the arch of the tomb recess, now plastered over, of a kneeling lady offering a small model of a church to a crowned Mary.[123] Moreover, shortly before her death, she granted to the dean and chapter of Hereford one acre of land at nearby Lugwardine and the appropriation of the church (presumably the one represented in the tomb recess painting) and several chapels. The revenues generated from these benefactions were used for the maintenance of masses in the Lady Chapel for the express purpose of improving Hereford Cathedral’s service to the Mother of God.[124]

That Joanna, who died in 1327, might have contributed funds toward the creation in 1300 of a Marian triptych incorporating a magnificent mappamundi is therefore chronologically possible and in keeping with her documented devotional concerns and track record of benefaction at Hereford Cathedral. Whether or not this might one day be confirmed upon discovery of written evidence, the Map’s handmaiden augments the female presence in the Last Judgement scene, as does a second female figure, this one quite fashionably dressed,[125] standing in the lineup of the elect to the right (our left) of the handmaiden (Fig. 21). Because fashionable feminine costume is her only distinguishing characteristic, and because she has been accorded a position of relative privilege among heaven’s otherwise all-male company of the blessed, I read this second figure not as a reference to a specific individual but rather as a heavenly placeholder for any and all aristocratic benefactresses who, like Joanna de Bohun, contributed to the material and spiritual enrichment of Hereford Cathedral.

Figure 21. Aristocratic female among the elect, detail of Hereford Map (photo: © Hereford Cathedral).

If we are to entertain the possibility of female patronage for this major cathedral monument, then we must ask why—contrary to its direct commemoration of Richard of Haldingham, and against the backdrop of conventional public recognition of church benefaction—there is no inscribed female name or heraldic identification next to the handmaiden figure or anywhere else on the work. In view of the Map’s female presence, might anonymity be understood as a gesture of humility—if not an act of silencing? Of more pressing concern is the need to explain the tension between (potential) patroness and object: Why would a woman commission or fund a work of art that foregrounds misogynist messages? The answer to this second question, I believe, lies in the symbiotic relationship between antifeminist theological beliefs and patriarchal social structures that were normalized and upheld by Christian men and women. Documentary records long attest to female patronage of medieval artistic and literary works, both religious and secular, which ratified the patriarchy. Equally long are patterns of religious women who internalized Church teachings about their own inherent physical and mental inferiority, and their need for masculine guidance and control.[126] Certain works of art, which I suggest included the Hereford Map, promoted institutionalized misogyny as part of a larger instruction around proper Christian moral conduct and eschatological expectations. From this perspective, female patronage of misogynistic artworks does not represent a conflict of interest so much as it bears witness to the universal pan-gender normalization of the controlling ideologies that these very artworks promote.

* * * * * * * *

The strategic placement and cartographic relationships of the Hereford Map’s female iconography offered medieval viewers opportunities for extended meditation on women’s subordinate position in the world and in the economy of Christian salvation. It must be remembered that the Map’s selection and distribution of female figures, like the rest of its design, is part of a masculine vision, executed by men with a stake in upholding male authority and keeping women’s ambitions in check. That such messaging appears on a Marian monument is in no way devotionally discordant: as Madeline Caviness has clarified, medieval representations of Mary ultimately point not to Mary herself, but to Jesus,[127] just as Mary’s secondary status to Jesus in the heavenly hierarchy (affirmed in the Map’s Last Judgement scene) provided the divine template for women’s secondary status to men in late medieval Christian societies. With this new scrutiny of the Hereford World Map, I hope to have demonstrated that the visual language of misogyny familiar to medieval viewers from manuscript illumination, stained glass, tapestry, monumental and small-scale sculpture, embroidery, and wall painting also received sophisticated development in the spaces of the mappaemundi, an artistic medium in which cartographic strategies and geographical juxtapositions could further enrich and intensify their meanings. Having begun my investigation with Mary, I end it by observing that the Map’s lessons about women and the masculine need to control them are especially poignant on a monument to this most holy Virgin, whose unequalled virtue lay in her ability to transcend the female nature and associated sins inescapably embodied by all other women.

References

| ↑1 | The Hereford Map literature is extensive. Major studies include P. D. A. Harvey, Mappa Mundi: The Hereford World Map (London: British Library, 1996); Naomi Reed Kline, Maps of Medieval Thought: The Hereford Paradigm (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2001); Scott Westrem, The Hereford Map: A Transcription and Translation of the Legends with Commentary (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001) (hereafter cited as Westrem); P. D. A. Harvey, ed., The Hereford World Map: Medieval Maps in Context (London, 2006); and Marcia Kupfer, Art and Optics in the Hereford Map: An English Mappa Mundi c. 1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016). Unless otherwise noted, I cite Westrem’s expanded Latin transcriptions and English translations of the map’s inscriptions, and I follow his numerical system for the locations of its images. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Hereford Map’s more precise measurements are 5 ft. 2 in. x 4 ft. 4 in. (1.59 m. x 1.29–1.34 m.). |

| ↑3 | On the Map’s sources, see Westrem, xxvii–xxxvii; and Patrick Gautier Dalché, “Decrire le monde et situer les lieux au XIIe siècle: L’Expositio mappe mundi et la généalogie de la mappemonde de Hereford,” Mélanges de l’École française de Rome. Moyen Âge 113 (2001): 343–409. By ‘popular bible’, I refer to the aggregate biblical knowledge collected by Peter Comestor in his Historia Scholastica (c. 1170) and in later compilations. See James H. Morey, “Peter Comestor, Biblical Paraphrase, and the Medieval Popular Bible,” Speculum 68 (1993): 6–35; and Brian Murdoch, The Medieval Popular Bible: Expansions of Genesis in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2003). https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.2001.11111 |

| ↑4 | On these narrative scenes, see Valerie I. J. Flint, “The Hereford Map: Its Author(s), Two Scenes and a Border,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 8 (1998): 19–44; Diarmuid Scully, “Augustus, Rome, Britain, and Ireland on the Hereford mappa mundi: Imperium and Salvation,” Peregrinations 4 (2013): 107–33; and Kupfer, Art and Optics, 33–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/3679287 |

| ↑5 | Westrem, 86–87, no. 181. |

| ↑6 | This and subsequent biblical quotations are taken from the Douay-Rheims version of the bible. See Augustine, Tractates on the Gospel of John 6.10.2, trans. John Gibb in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, vol. 7, ed. Philip Schaff (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1888) rev. & ed. Kevin Knight http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/1701.htm; The Middle English Metrical Paraphrase of the Old Testament, ed. Michael Livingston (Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 2011), 31 (ll. 361–372); and Theodore Hiebert, “The Tower of Babel and the Origins of the World’s Cultures,” Journal of Biblical Literature 126 (2007): 29–58. On the Map’s Tower of Babel icon, see Kupfer, Art and Optics, 66–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/27638419 |

| ↑7 | For patristic sources, see The Seven Deadly Sins, ed. Kevin M. Clarke (Washington, DC: Catholic University Press of America, 2018), 166–85. Definitive for later periods is the extended discussion of pride in Innocent III’s On the Misery of the Human Condition 2.30–2.34 (c. 1196). See Lothario dei Segni (Pope Innocent III), On the Misery of the Human Condition / De miseria humane conditionis, ed. and trans. Donald R. Howard (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1969), 55–60. |

| ↑8 | For example, Part 1 of the Fasciculus morum, which includes numerous antifeminist exempla, is devoted to pride. Edition: Fasciculus morum: A Fourteenth-Century Preacher’s Handbook, ed. and trans. Siegfried Wenzel (University Park: Pennsylvania University Press, 1989), 32–115. See also Siegfried Wenzel, Verses in Sermons:“Fasciculus morum” and Its Middle English Poems (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978). |

| ↑9 | The famous “Devil’s gateway” passage in Tertullian’s De cultu feminarum (1.1.2) is often cited in this connection; see F. Forrester Church, “Sex and Salvation in Tertullian,” Harvard Theological Review 68 (1975): 83–101. See also Augustine of Hippo, On Christian Doctrine 1.13.12–1.15.14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017816000017077 |

| ↑10 | For an overview of this tradition, see Philippe Delhaye, “Le Dossier anti-matrimonial de l’Adversus Jovinianum et son influence sur quelques ecrits latins du XIIe siècle,” Mediaeval Studies 13 (1951): 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.MS.2.305912 |

| ↑11 | In addition to the Hereford Map, Baumgärtner analyzes a range of female figures on the Ebstorf Map and the Catalan Atlas, among other mappaemundi. See Ingrid Baumgärtner, “Biblical, Mythical, and Foreign Women in Texts and Pictures on Medieval World Maps,” in Harvey, Hereford World Map, 305–27. |

| ↑12 | Pioneering art historical work includes Madeline H. Caviness, “Patron or Matron?: A Capetian Bride and a Vade Mecum for Her Marriage Bed,” Speculum 68 (1993): 333–62. https://doi.org/10.2307/2864556; and Madeline H. Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001). For an overview of the issues and further bibliography, see Sherry Lindquist, “Gender,” Studies in Iconography 33 (2012): 113–30; Martha Easton, “Feminism,” Studies in Iconography 33 (2012): 99–112; and Sherry Lindquist, “Introduction to Gender and Otherness in Medieval and Early Modern Art,” in Gender, Otherness, and Culture in Medieval and Early Modern Art, ed. Carlee A. Bradbury and Michelle Moseley-Christian (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65049-4_1 |

| ↑13 | Kate Manne, Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190604981.001.0001 |

| ↑14 | Manne, Down Girl, 33. |

| ↑15 | The shrine, cult, and miracles (some 461, exceeded in England only by St. Thomas of Canterbury) of St. Thomas Cantilupe began in 1287 (prior to his canonization in 1320) and continued at pace for about sixty years. See Meryl Jancey, ed., St Thomas Cantilupe, Bishop of Hereford: Essays in His Honour (Hereford: Friends of Hereford Cathedral, 1982); Nicola Coldstream, “The Medieval Tombs and the Shrine of Saint Thomas Cantilupe,” in Gerald Aylmer and John Tiller, eds., Hereford Cathedral: A History (London: Hambledon Press, 2000), 322–30; Robert Bartlett, The Hanged Man: A Story of Miracle, Memory and Colonialism in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); and Michael Tavenor and Ian Bass, Thomas de Cantilupe: 700 Years a Saint (Eardisley: Logaston Press, 2020), 63–83. For case studies of miracles, some involving women, see J. H. Ross and Meryl Jancey, “The Miracles of St Thomas of Hereford,” British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition) 295, no. 6613 (1987): 1590–94. |

| ↑16 | On literacy during this period, see especially M. T. Clanchy, Looking Back from the Invention of Printing: Mothers and the Teaching of Reading in the Middle Ages (Turnhout: Brepols, 2018). |

| ↑17 | Marcia Kupfer, “Medieval World Maps: Embedded Images, Interpretive Frames,” Word & Image 10 (1994): 262–88, esp. 272–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666286.1994.10435518 |

| ↑18 | Dan Terkla, “Informal Catechesis and the Hereford Mappa Mundi,” in The Art, Science, and Technology of Medieval Travel, Robert Bork and Andrea Kahn (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), 127–42. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315241265-10 |

| ↑19 | The seminal reconstruction of this process, grounded in extensive evidence, is Conrad Rudolph, “The Tour Guide in the Middle Ages: Guide Culture and the Mediation of Public Art,” Art Bulletin 100 (2018): 36–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2017.1367910 |

| ↑20 | Conrad Rudolph, “Macro/Microcosm at Vézelay: The Narthex Portal and Non-Elite Participation in Elite Spirituality,” Speculum 96 (2021): 601–61. https://doi.org/10.1086/714579 |

| ↑21 | Rudolph, “Tour Guide,” 41. |

| ↑22 | See Robert Swanson and David Lepine, “The Later Middle Ages, 1268–1535,” in Aylmer and Tiller, Hereford Cathedral, 48–86, at 64–69. |

| ↑23 | Westrem, 314, no. 806. Over the past decade of studying the Map in the Hereford Cathedral Mappa Mundi Centre, I have observed that where ‘we’ are is often the first thing visitors ask of the attendant docent. |

| ↑24 | “Tuz ki cest estorie ont / Ou oyront ou lirront ou veront. / Prient a ihesu en deyte / . . . (Westrem, 11, no. 15). This inscription, which I discuss in more detail below, is located in the Map’s lower left corner. |

| ↑25 | See John Harper, “Music and Liturgy, 1300–1600,” in Aylmer and Tiller, Hereford Cathedral, 375–97, at 383–84. |

| ↑26 | On the Marian program at Hereford Cathedral, see Kline, Maps of Medieval Thought, 69–70; and Kupfer, Art and Optics, 44–46. See also Nigel Morgan, “Texts and Images of Marian Devotion in Thirteenth-Century England,” in England in the Thirteenth Century: Proceedings of the 1989 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. W. M. Ormrod (Stamford: Watkins, 1991), 69–103, esp. 97 (on the Hereford Map). |

| ↑27 | Kupfer, Art and Optics, 1–29; 44–49. On the Map, the Annunciation is also evoked by the icon of the Golden Fleece, situated just north (left) of Noah’s ark, as Gideon’s receipt of the Golden Fleece was a typological parallel for the Annunciation. See M. R. James, “Pictor in Carmine,” Archaeologia 94 (1951): 141–66, at 148, 151. The icon of the fleece incidentally replicates the form of the calf skin on which the Map was painted. |

| ↑28 | By 1300, the main Marian pilgrimage shrine in England was in Walsingham, which housed a phial of Mary’s milk. See Gary Waller, Walsingham and the English Imagination (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011); and Dominic Janes and Gary Fredric Waller, eds., Walsingham in Literature and Culture from the Middle Ages to Modernity (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010). On milk relics at Walsingham and other pilgrimage sites, see Marina Warner, Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and Cult of the Virgin Mary (New York: Vintage Books, 1983), 200. |

| ↑29 | On the perceived gulf between Mary and ordinary women, see Warner, Alone, 333–39; and Madeline Caviness, “The Problem with Mary: Disembodying Motherhood,” in Caviness, Visualizing Women, 3–16. |

| ↑30 | On the rarity of this motif, see Kathryn A. Smith, The Taymouth Hours: Stories and the Construction of Self in Late Medieval England (London: British Library, 2012), 232. On the more conventional motifs of an intercessory Mary nursing the Christ child or baring a single breast, see Salvador Ryan, “The Persuasive Power of a Mother’s Breast: The Most Desperate Act of the Virgin Mary’s Advocacy,” Studia Hibernica 32 (2002): 59–74. I thank one of my Different Visions peer reviewers for bringing this study to my attention. https://doi.org/10.3828/sh.2003.32.3 |

| ↑31 | Westrem (6, no. 8) sees the maiden about to crown Mary, but since Mary is crowned only by Jesus in medieval art, I see the maiden’s gesture as servile. Crowns are associated with virginity in patristic writings; see Elaine Pagels, Adam, Eve, and the Serpent (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 78–97, at 86. |

| ↑32 | Kupfer, Art and Optics, 39, 132–33. |

| ↑33 | “Veici beu fiz, mon piz, de deinz la quele chare preistes, / E les mamelectes, dont leit de Virgin queistes./ Eyez merci de touz si com vos memes deistes, / Ke moy ont servi, kant Sauveresse me feistes” (Westrem, 6‒7, no. 8). On this trope, see Ryan, “Persuasive Power, 69–70. |

| ↑34 | On the sources, see Charles T. Wood, “The Doctor’s Dilemma: Sin, Salvation and the Menstrual Cycle,” Speculum 56 (1981): 710–27. See also Beth Williamson, “The Cloisters Double Intercession: The Virgin as Co-Redemptrix,” Apollo 152 (2000): 48–54; and Kupfer, Art and Optics, 39. https://doi.org/10.2307/2847360 |

| ↑35 | The bestiaries explain that rinoceron is the Greek term, and monoceron, the Latin term for ‘unicorn’. These terms are thus used interchangeably in the bestiaries and other sources, although the rhinoceros and monoceros are usually given separate bestiary entries that correspond to the Map’s inscriptions. See Westrem, 132–33, no. 297 (rhinoceros) and 182–83, no. 433 (monoceros); compare to the sequential bestiary entries for unicornis and rhinoceros / monoceros in Cynthia White, ed. and trans., From the Ark to the Pulpit: An Edition and Translation of the “Transitional” Northumberland Bestiary (13th century) (Louvain: Université Catholique de Louvain, 2009), 80–83 (hereafter cited as White). |

| ↑36 | “(. . . ) huic monoceroti virgo puella proponitur, que uenienti sinum aperit, in quo ille— omni ferocitate deposita—capud ponit, sic que soporatus uelud inermis capitur” (Westrem 183, no. 433). |

| ↑37 | The relevant bestiary passage reads in full: “Sic et Dominus noster Iesus Christus spiritualis unicornis descendens in uterum virginis per carnem ex ea sumptam, captus a Iudeis, morte crucis dampnatur qui invisibilis cum Patre hactenus habebatur” (In the same way our Lord Jesus Christ, a spiritual unicorn who descends in the womb of a virgin through flesh taken from her, is seized by the Jews and condemned to a death on the cross) (White, 80–81). This text closely follows the earlier Physiologus unicorn entry; see Physiologus Latinus…versio B, ed. Francis J. Carmody (Paris: Librairie Droz, 1939), 31. |

| ↑38 | Edition: Richard de Fournival, Le Bestiaire d’Amour et la Response du Bestiaire, ed. Gabriel Bianciotto (Paris: Champion, 2009). English translation: Richard of Fournival, Master Richard’s Bestiary of Love and Response, trans. Jeanette Beer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986) (hereafter cited as Beer). The critical literature on this work is large. Feminist approaches include Jeanette Beer, Beasts of Love: Richard de Fournival’s Bestiaire d’amour and a Woman’s Response (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2003); and Helen Solterer, “Letter Writing and Picture Reading: Medieval Textuality and the Bestiaire d’Amour,” Word & Image 5 (1989): 131–47. |

| ↑39 | On the work’s influence, see Beer, Beasts of Love, 149–73. |

| ↑40 | London, British Library, MS Harley 273, fols. 70r-81r: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Harley_MS_273. |

| ↑41 | Beer, 15–16. |

| ↑42 | See Bianciotto, Bestiaire d’amour, 83–94, 95–96 (list of Response manuscripts). For the argument that the author of the Response was a woman, see Jeanette Beer, “Richard de Fournival’s Anonymous Lady: The Character of the Response to the Bestiaire d’amour,” Romance Philology 42 (1989): 267–73. |

| ↑43 | Beer, 47. |

| ↑44 | “…in naribus cornu unum mucronem excitat; [eo]que aduersus elephant[o]s preliatur; par ipsis in longitudine sed breuior cruribus, naturaliter allvm petens, quam solam intelligit ictibus pervia[m]” (. . . [the rhinoceros] shoots out a sharply pointed horn from its nose; it fights with elephants, with which it is equal in length but shorter in limbs; it naturally seeks out the belly, which it knows alone [of the parts of an elephant] to be vulnerable to attack) (Westrem 133, no. 297). |

| ↑45 | London, British Library, MS Royal 12.F.XIII, fol. 10v: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMINBig.ASP?size=big&IllID=47419. |

| ↑46 | Beth Williamson, “The Virgin Lactans as Second Eve: Image of the Salvatrix,” Studies in Iconography 20 (1998): 105–138. On the broader theological implications of this concept for the Map’s design, see Kupfer, Art and Optics, 129–33. |

| ↑47 | According to Genesis, God created Adam first and directly from the earth (Gen. 2:7), and then to provide Adam with a suitable ‘helper’ (none of the animals having proved suitable), he created Eve from Adam’s own flesh (Gen. 2:18-23). From this point, as R. Howard Bloch pithily observed, “She is side issue.” See R. Howard Bloch, “Medieval Misogyny,” Representations 20 (1987): 1–24, at 11. |

| ↑48 | The Gothic-style gate is inscribed paradis porta. Also inscribed are Adam (Adam), Eve (Eua), and the Four Rivers of Paradise (Eufrates, Tigri, Phison, Gion). See Westrem, 34–37, nos. 64–70. |

| ↑49 | On the patristic development of the anti-Eve tradition, see Pagels, Adam, 98–126. This view met with consensus across Christian exegetical writing and in ‘vernacular theology’ produced by fourteenth-century English authors writing about theological subjects in their native language. See Nicolas Watson, “Censorship and Cultural Change in Late-Medieval England: Vernacular Theology, the Oxford Translation Debate, and Arundel’s Constitutions of 1409,” Speculum 70 (1995): 822–64, at 823. For example, the c. 1300 Cursor mundi identifies Eve and the serpent as coequal threats to Adam! “On eiþer side he haþ a fo / Bitwene sathan & his wif / Adam is sett in mychel strif / Boþ were þei on Adame / For to brynge him to blame / Boþe be o party / To ouercom man wiþ tricchery” (ll. 724–730). See Cursor Mundi (The Cursur o the world): A Northumbrian Poem of the XIVth Century in Four Versions, Part I, ed. Richard Morris, Early English Text Society, o.s. 57 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 51. For a summary of the feminist scholarship around Eve, including contributions by Hildegard of Bingen and Christine de Pizan, see Jennifer L. Kossed, “Reading the Bible as a Feminist,” Brill Research Perspectives in Biblical Interpretation 2.2 (2017): 1–75, at 46–64. |

| ↑50 | Westrem, 38–39, no. 76. On the legend of the Dry Tree, popular in England from the thirteenth century, see Rosanne Gasse, “The Dry Tree Legend in Medieval Literature,” Fifteenth-Century Studies 38 (2013): 65–96. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781571138613-004 |

| ↑51 | Westrem, 36–37, no. 71. |

| ↑52 | Compare to the Expulsion scene in the Holkham Bible (London? 1327–1335), London, British Library Add. MS 47682, fol. 4r: https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMINBig.ASP?size=big&IllID=28811. |

| ↑53 | Westrem, 40–41, no. 81. For the Middle English apocryphal stories about what Adam and Eve got up to after they were expelled from Paradise, see The Apocryphal Lives of Adam and Eve, ed. Brian Murdoch and J. A. Tasioulas (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2002). On the misogynistic dimensions of these stories, see James M. Dean, “Domestic and Material Culture in the Middle English Adam Books,” Studies in Philology 107 (2010): 25–47, esp. 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1353/sip.0.0043 |

| ↑54 | The story appears in the twelfth-century poetic compilation known as the Vienna Genesis (26.8). See Die frühmittelhochdeutsche Wiener Genesis, ed. Kathryn Smits (Berlin: Erich Schmidt, 1972), 135–37; cited in John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 93–94. |

| ↑55 | New Haven, Beinecke Library Yale MS 404, fol. 113r: https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2002755 (image 249 in the digital viewer) See Jeffrey F. Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 211–12. |

| ↑56 | In medieval sources, Dogheads (cynocephali) were often described as gigantic, as the Map’s inscription attests. See Westrem, 40–41, no. 80; Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England (New York: Routledge, 2006), 46–50; and Robert Bartlett, “Dogs and Dogheads: The Inhabitants of the World,” in The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 71–110. |

| ↑57 | A key text in the medieval debate is the letter written in the late ninth century by Ratramnus to the priest, Rimbert. See “Ratramnus and the Dog-Headed Humans,” in Carolingian Civilization: A Reader, 2nd ed., ed. Paul Edward Dutton (Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview Press, 2004), 452–55; and Bartlett, “Dogs and Dogheads,” 95–101. Earlier, Augustine of Hippo (City of God 16.8) remained on the fence as to whether Dogheads and other monstrous peoples—if indeed these even existed–were human. See Friedman, Monstrous Races, 90–92. Augustine, dressed in his episcopal finery, is represented on the Map inside his own aedicule (strangely tilted 90 degrees) situated in Hippo, on the south (right) side of the lower Mediterranean. The aedicule is inscribed “Ippone, regnum et civitas Sancti Augustini, episcopi” (Hippo, the kingdom and city of Saint Augustine, the bishop) (Westrem, 358–59, no. 918). |

| ↑58 | On the iconography of the Exodus path, see Debra Higgs Strickland, “Edward I, Exodus, and England on the Hereford World Map,” Speculum 93 (April 2018): 420–69. https://doi.org/10.1086/696540 |

| ↑59 | Westrem, 118–19, nos. 262 (Sodom) and 263 (Gomorrah). |

| ↑60 | “Uxor Loth, mutata in petra salis” (Westrem, 116–17, no. 254). |