Nonetheless, seemed like a great opportunity to feature the Walters’ glorious collection of illuminated manuscripts alongside a modern manuscript that has aroused some interest among the general public. And yet, the exhibition touched off a vigorous and rather difficult discussion among the staff about the very appropriateness of showing contemporary religious art within a public museum. Even though the great majority of works in the Walters are religious in nature, they are also entirely historical. No one would think that the artifacts on display in the museum constituted an endorsement of Mithraism or an inducement to use enemas spiked with psychoactive substances to access the Mayan spirit world (even if that would allow us to settle this whole “2012” thing once and for all). Even those works from living traditions (Buddhism, the Abrahamic faiths) had been largely de-consecrated, denatured by time, and displaced from their religious settings to become art objects.

Perhaps naively, I didn’t see why exhibiting the SJB should be any different, but some on the staff felt that, in showing contemporary Christian art, the Walters was allowing itself to become a platform for evangelism. In response to these anxieties, we tried to direct attention away from the spiritual themes of the book by looking at how it was made, by comparing its scripts to earlier calligraphic traditions, and by setting it in a global religious context (we had a Koran front and center in the first room). “See? It’s just another work of art. Don’t worry, it won’t infect your mind.”

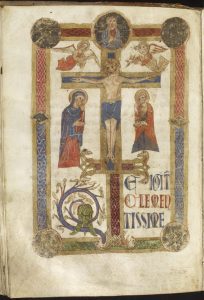

Missal (The “St. Francis Missal”). Assisi, Italy, 1172-1228. Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. W.75, f. 166v.

When the show went up, the reaction to its religious content was mixed. Many people came because they were interested in the artistry and calligraphy. Some Jewish museum members admitted to me that they went to the show primarily out of a sense of obligation, but found themselves pleasantly surprised. So the ploy to de-sanctify the art apparently worked. But then I also witnessed people praying in front of the Saint John’s Bible, and in front of some of the older books. A group of Franciscan monks came to see a missal that is recognized as a relic of St. Francis. To them, this absolutely was a religious show. The setting couldn’t obscure the divinity of these objects.

Most of the art I study was made by and for medieval Christians, and I end up spending a lot of time exploring questions of dogma and theology. I absolutely love the material, even though I am thoroughly agnostic and wholly uncurious about whether or not a god exists. I suppose I enjoy it primarily as a spectator. This stuff isn’t mine, it isn’t me; I’m just an historian trying to understand what these things are. I’m certainly not in the minority in cultivating this mindset. I think, generally, that most scholars feel that they need some sort of “necessary distance” to do good work on a topic.

But the Saint John’s Bible exhibition (and a recent book chapter I wrote on the manuscript) recently inspired me to wonder if I’ll ever really get the art I work on. I worry that maintaining emotional, philosophical, and spiritual distance entirely misses the point of religious art. Is it possible for me to really understand something that is meant to provide a connection to the divine if I don’t claim to know if that divinity exists? If seeing Jesus on the cross evokes no particular sorrow (or gratitude) in me, am I in any position to try to interpret that work of art? At what point does the “necessary distance” become a chasm?