I’m sure many people (especially art historians) may have had the feeling that a painting has haunted their life, but people tell me that my case may be exceptional. Reproductions of Giovanni Bellini’s Portrait of Doge Leonardo Loredan hang in my office and dining room, in my closet ironed onto the back of a kimono crafted by a friend to wear on Halloween, and have previously appeared in six apartments, three dorm rooms, a childhood bedroom, and on the backgrounds of two cell phones.

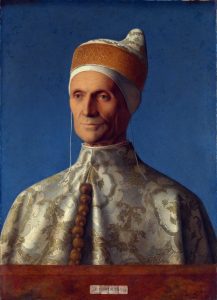

Giovanni Bellini, Doge Leonardo Loredan, 1501-02

I must have seen the painting for the first time when I was about 10, on a trip to London with my family. I don’t remember my first encounter with it, but I bought a postcard that hung in my bedroom and slowly worked its way into my imagination. My real engagement with the painting started my senior year in high school, when I read and was infuriated by an article in The New Yorker about David Hockney’s claims that Bellini and other Renaissance painters used lenses to project and trace their images. I wrote a letter to the editor (thankfully, never published) lambasting the article—I couldn’t accept that my favorite painting was somehow “fake.” Now, of course, I can’t run from that letter fast enough. Now I study, as my job, art’s intersection with science and technology, and am fascinated by how painters used these kinds of tricks. Yet the letter keeps catching up with me; to my dismay, my mother read it aloud during a toast at a celebratory graduation dinner (who knows how she even got her hands on it). It seemed too complicated to try to explain why I disagreed with everything I had written before; I really just wanted to crawl under the table to avoid having to confront the pretentious, outraged tone of my teenage self.

I feel a bit less embarrassed by my response to the painting as I was set to enter college. I wrote about it in my application essay, explaining the ways that I saw myself, aged a few decades, in the painting’s subject—that there was something that I felt he and I shared. Now, having seen so many other people’s response to the painting, I can only assume that this alarmed the admissions officers. To me, he was kind, but to others he was severe, creepy, emaciated, stern. In my love for the painting I thought I’d found the perfect example of my love of art, something that I assumed would bind me to others, but it was quite the opposite—it just revealed another layer of difference, of a response to something that wasn’t quite right. In the years that followed, my friends became affectionately amused by my attachment to the painting, but they never hesitated in conveying their impressions and questions. How can you think he looks like a nice guy? Benevolent? Are you kidding? Why would you want to grow up to be HIM? Is that a man or a woman? Don’t you feel like he’s watching you while you’re eating/working/sleeping (depending on the room where it was currently hung)? My partner accepted the painting with good humor, helping me hang a reproduction in our first apartment, giving me the time to explain all the meanings it had for me, nodding knowingly to each.

After so many years of looking at it, I am finally starting to see what all these people meant—there is a sense of the uncanny in the figure’s expression. Now that I think about it, he might actually be a ghost, haunting the streets of Venice every time I visit, ensuring that things are never quite right. The time when I was five and went to Venice with my parents and a cast on my broken arm, and then returned home to have the doctor saw off the cast and find a piece of corn inside from feeding the pigeons in San Marco Square. Was he there twenty years later when, in the middle of the afternoon and miles from my hotel, I fell into one of the canals (joining an illustrious list that includes Katharine Hepburn, George Eliot’s husband, and, in the fourteenth century, a relic of the true cross)? A couple years later when shouting teenagers set up shop in the Campo San Tomà outside my hotel windows for an entire week, keeping me from any sleep?

I still look at the painting dozens of times every day—I can see it from the chair at my office desk and my place at the dining room table at home. In some ways I think I’m finally starting to figure it out. Before, I always thought it was about the person—the Doge Leonardo Loredan—and some connection I felt with him across time (despite knowing little about him). That he was my kindred spirit. But he has faded into the background. What I see now, and what I have perhaps always loved but not been able to express, are miracles of paint on a surface. How the blue of the background shifts a single tonal increment, impossibly slowly, from bottom to top. How the shine of the silk is both rough and smooth, catching light and producing it. The drawn lips and lined face contrasting with the bright, youthful eyes. The perfect simplicity of the pose and composition. The way that, in the absence of arms or hands, the head seems almost disembodied, perched atop a cloth-covered pedestal. I think I love it because it has always seemed to me to be a perfect painting—one that couldn’t exist in any other way than the way it is, a house of cards whose glory would crash down if a single detail was changed. If the string of nuts on his jacket were simply buttons, I think I might be able to look away. Or if the two single threads didn’t fall down from the cap, breaking the simple outline of the figure against background. In the painting I’ve embraced on some visceral level some quality of perfection and genius that I otherwise reject as a myth.

Now this is starting to feel like a college application essay—another case all over again where I try to reveal myself through examination of something else (though of course it looks nothing like the essay I wrote on the painting when I was an applicant at 17). I didn’t intend it to be that—I’m just trying to understand why I can’t escape the painting. How could I have been under its spell for so many years? It returns me again to the knowledge that there are works of art that I want to look at and live with, and works of art that I want to study, and that they are often not the same. In my years of work, I’ve never wanted to read (and never have) a single scholarly article on Bellini’s painting. Though now I know that Hockney was right about the Renaissance use of optics and mirrors to create near-photographic effects in such paintings, I don’t want to think about it here. All I want to do is look at the painting—not think about it. I wonder if other art historians have secret obsessions like this, and, if so, what they are—these paintings or objects that we wall off from our scholarly minds and preserve in some other realm.

Karl Whittington is Assistant Professor of Medieval Art History at The Ohio State University. His research explores issues such as art and science, medieval image theory, and gender and sexuality.