Karen Williams • University at Albany

Recommended citation: Karen Williams, “The Crucifixion Window in the Scrope Chapel of Yorkminster,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/KBUE4327.

The following essay draws on my dissertation, Christ at the Gates of the Minster, which examines the use of social space in relation to audience meaning making in the York Plays. Rachel is on my dissertation committee, and through her work, her graduate course on Women in Medieval Art, and our conversations, I learned the many ways that visual arts help us understand more about cultures and power dynamics within those cultures. Rachel’s teaching and scholarship also encouraged exploration and a bit of informed risk taking as I brought together drama, space, and visual arts in my dissertation. Thank you, Rachel.

*****

Almost as soon as Henry IV had allowed Archbishop Richard Scrope to be buried in a tomb in the Minster after ordering Scrope’s beheading, the king began working to limit public access to and attention on the tomb. Scrope’s tomb became a popular focal point for autonomy and resistance, causing Henry and other supporting leaders to issue decrees, beginning in December 1405, only six months after Scrope’s execution. The decrees attempted to steer people away by discrediting miracles at the tomb, a move to prevent the popularity of this local, rebellious “saint” from leading to another uprising like the Rebellion of 1381, still fresh in many nobles’ memories.[1] After a second push to deter both pilgrims and the political inspiration that coalesced around Scrope’s tomb, in April 1406 a wall was constructed around the tomb to further discourage visitation. Ultimately the wall was removed and homage to Scrope continued, with an officially sanctioned shift in narrative from his death and martyrdom to his saintly acts in life.[2]

Figure 1. York Minster, east end. The Crucifixion window is visible on the right, to the north of the larger Great East Window. Photo © Budby (https://flickr.com/photos/30120216@N07/albums/72157627536552608), reproduced by permission.

Figure 2. St Stephen’s Chapel (left) and Lady Chapel (right), York Minster. Photo © York Minster. CC BY-SA 2.0.

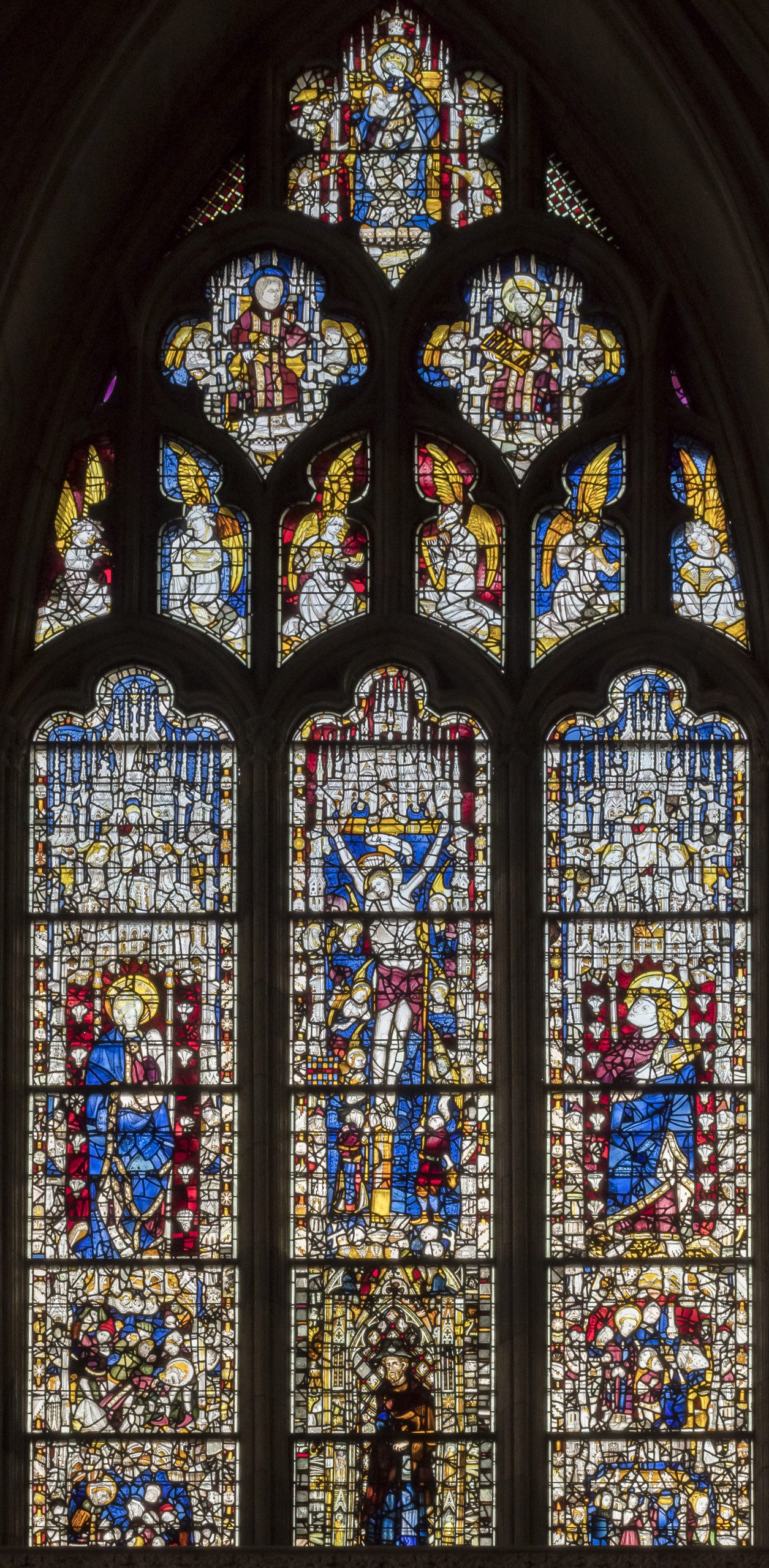

Scrope’s tomb is in the Chapel of St. Stephen, an accessible area of the minster next to the Lady Chapel, just north on the same wall as the Great East Window. The chapel window is above the altar and features the Crucifixion of Christ surrounded by other deacon martyrs and local martyrs, as well as St. John the Evangelist and Mary.[3] [A high resolution, zoomable image of the window is available on the website of the York Glaziers Trust; the Crucifixion comprises panels 3b-6b.] The chapel became popularly known as the Scrope Chapel shortly after Archbishop Scrope’s martyrdom in June 1405,[4] and the window may have been commissioned by the Scrope family, including a brother, John, who referenced the “Scrope Chapel” in his will in 1451.[5] Based on stylistic evidence, the Minster assigns a date of mid-fifteenth century to the window. So it seems quite likely that it was purposely commissioned to reflect and reinforce the popular connection between Scrope’s execution and martyrdom and Christ’s sacrifice.

This window and the Scrope chapel would have been visited by a wide range of city residents and others from the surrounding areas and even other parts of England and Scotland, based on analysis of the coins left at the tomb by visitors and pilgrims. These coins tell us that people traveled to visit the tomb, and also that they were of varying classes since there was variety in the value of coin offerings. So it seems likely that Scrope was admired by a wide range of residents and pilgrims, and we can speculate about their viewing of the window in connection with their visit to the tomb. While parts of the window date to before Scrope’s death, and may have been used to replace damaged glass at some later date, the main sections of the window focusing on the crucifixion and the surrounding figures are generally dated to shortly after Scrope’s death. So it is likely they were put in place above his tomb once his acts were widely known.

For visitors entering the Minster through the west entrance under the Rose window, and proceeding through the Nave, the Scrope Chapel and the Crucifixion Window would not have been very visible initially. Possibly the upper lights of the window could have been seen, if one looked above the rood screen and the quire. Certainly the Great East Window, which would have been in the process of being created throughout decades in the early to mid-fifteenth century, would have been visible. But since people generally knew of the chapel where Scrope’s tomb stood, they would have passed through the nave and headed up the north aisle outside of the quire. Once in the aisle, the window would have been fully visible, without obstruction.

Figure 3. Crucifixion, York Minster Window n2, mostly c.1440. Photo ©Jules & Jenny (https://flickr.com/photos/jpguffogg/), CC BY 2.0.

A visitor seeking to honor Scrope would look up at the window and gaze upon Christ’s Crucifixion. The image is brightly colored, bordered, and intricate. The eyes of each figure in the larger central panels are focused on Christ, drawing the viewer’s gaze to the central figure. Even St. James (panel 2b) seems to raise his eyes to Christ, above him. The viewer, perhaps a gild member of the Pinners—the gild that “brought forth” the Crucifixion play in York’s civic pageants each year—or another craftsman, would have had life-long knowledge of the central topic of the window. The focal image, Christ on the cross, is typologically consistent with the narrative of the crucifixion in the early- to mid-fifteenth century. In this central panel Christ is surrounded by angels and below him on the ground are Longinus, with a clearly visible spear, and Stephanton, with his stick and sponge. Many other faces within this central panel look on, some humans and some grotesques, including figures throughout the canopy of the three main panels, one of whom looks on from the lower left of the central panel, wearing a dark red pointed cap that may identify him as a Jewish priest. Images of contemporary architecture, steeples, and towers create canopies within each of the three central panels. These canopies can be seen as two-dimensional frames for the sacred space which encloses the figures of Christ, Mary, and St. John the Evangelist. In this framework, the human priestly figures are in line with the architectural structures, making the priest figures a part of the border between Christ and the “outside,” while the grotesques fall further outside the sacred space, creating a hierarchy of distance from Christ. If the capped figure is meant as a Jewish cleric, the image may remind the viewer that those who condemned Christ were within the official power structure. Interestingly, intermingled with the grotesques are shining candles, as if the actions and figures within these canopies may offer light to those who occupy the margins of society. Golgotha, Christ’s place of crucifixion, is included within the canopy, as a place of momentous significance and as a sacred space. The skulls at the base of Golgotha visually echo the faces of the grotesques, further suggesting that the grotesques are part of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice.

The shining candles mingled among the grotesques open up questions regarding the relationship between those outside of the frame and the “light,” whether that is the light of God or the light that drives out evil. The grotesques are absent from the lights in the tracery, possibly complicating the unconditional acceptance suggested by their inclusion in the three main panels. In a city and a culture that was acutely aware of the societal boundaries that delineated those within from those without–religion, socio-economic factors, nationality, among others—those outside were generally depicted as sorrowful, in darkness, or otherwise separate. The grotesques are also unbounded by the architectural frame. While the priests are contained within the architectural frames of each panel, the grotesques continue up the main structural frame to the height of the spires. The frame acknowledges the hierarchy of those officially belonging to society and those outside of recognized structures. Creating an image of those “outsiders” as potentially enlightened opens up nontraditional portions of the population to grace. The commoners and the lay people, those within liberties and those beyond the city proper, or even those outside of civic structures, can also lay claim to Christ’s sacrifice and Scrope’s legacy in York.

In the midst of these grotesques, Christ’s posture is consistent with moda of the time and brings to the fore his humanity. While it seems likely some pieces of the window have been replaced, for instance by the inconsistency we see on the left side of Mary’s halo and on the top of Christ’s halo, the figure fits with the tone and tradition of the early- to mid-fifteenth century. Christ’s face is sorrowful with slightly open eyes. His gaze seems to be directed downward, toward visitors to the minster. Interestingly, in light of the focus on Christ’s humanity and suffering, there is little evidence of the stigmata, though this again could possibly be attributed to restorations, including one or both of his hands, since we see drops of liquid trailing down his feet. His crown of thorns is clear and bright, and difficult to miss. The emotive and human image of the crucifixion is enhanced in this window as both Mary and John the Evangelist look on with sorrow. Though Mary’s face shows no visible tears, she is somber. She is depicted with her crown and halo, pointing to the biblical narrative of her future coronation. John has a less somber expression. He gestures toward the book that he holds in his other hand as if in presentation. The viewer experiences both the mother’s sorrow at her son’s death and the reminder of the Gospels that grew out of the Crucifixion.

The Scrope family would likely have been content to send a message of sacrifice and sorrow through a visual image above Scrope’s tomb in an attempt to redeem the archbishop’s legacy and reinforce Scrope’s popular reputation as a martyr among the local community. The family was ultimately brought back into the noble fold by the crown under Henry V, and the local popular admiration for the archbishop was lasting, in spite of the reconciliation. The sorrow experienced by the community in the aftermath of the uprising and Scrope’s execution was present for decades, and Scrope’s tomb continued to draw pilgrims during that time and beyond. The image that the family may have imagined — one of a virtuous member who sacrificed himself for a just cause, even if it meant going against the Crown — would have resonated with York residents and remained, even as they likely held on to the popular, rebellious elements of Scrope’s legend.

Most viewers of the window would bring with them numerous and varied cultural connections to the Crucifixion, from other visual images, sermons, books of hours, and the civic biblical plays of York, among others. The crucifixion section of the civic cycle traveled throughout the city every year and would have been viewed by numerous locals, as well as people from afar. There are some interesting choices in this window as it relates to the biblical narrative and to popular understanding of the episode, so the elements of this window and its panels that are narratively or visually unique would have stood out. For a viewership skilled at reading visual narratives, the juxtapositions of Christ and the figures that surround him would have added layers of complexity. Christ’s crucifixion and St. Stephen’s stoning — depicted below the Virgin Mary, in panel 2a — become a comment on Archbishop Scrope and his martyrdom. Both St. Stephen and Scrope are said to have repeated Christ’s words of forgiveness for those who killed them. Scrope’s tomb, at the southern edge of the chapel, builds a connection among Scrope, Stephen, and Christ, all of whom are martyred for their beliefs by those with official authority. Laurence, a popular saint in York, also figures into this schema, though in a less prominent manner as he shows up only in the upper lights in one image (B2), paired with Stephen: they are deacon martyrs who stood against authority. Martyrdom is typically connected to Christ’s sacrifice and crucifixion, but Stephen and Laurence would have provided additional significance for the legacy of narrative and family of Archbishop Scrope in their roles as church officials. Like Christ, they upset the order from within, as they were a part of the church they sought to change, much as Scrope used his position as archbishop to preach against and undermine Henry Bolingbroke’s victory and accession in favor of York’s relationship with Richard, costing him his life.

Scrope’s demands in the rebellion had been specific and supported by common citizens and the merchant and noble classes, alike. York had generally enjoyed reduced financial burdens for the Crown and lower taxes, among other claims that furthered the city’s autonomy. Scrope seemingly assumed that his locally popular position would translate to power with the king and his representatives, a mistake that allowed Scrope to send home all of his supporting “troops,” and fall prey to deception and capture. The urgency and behind-closed-doors nature of Scrope’s trials were likely paralleled to Christ’s capture at night in a rush to beat the clock before the sabbath. While all martyrs have sacrificed themselves in Christ-like ways, the stories of Scrope’s trial and execution show striking, and in some cases likely purposeful, connections. Scrope was placed on a “sorry horse,” comforted Thomas Mowbray, his partner in rebellion and execution, and forgave his executioners and those who ordered the execution. The cause he died for was also seen as just in the North, benefitting the community, and thus Christ-like. The citizens of York had long valued their autonomy and strove to be as free as possible from royal obligations and taxes. Scrope’s rebellion explicitly argued against more taxation and interference by the crown. So local people, bolstered by the martyr’s presence in their community, visited this tomb in the popularly named Scrope Chapel to honor a popular hero and martyr.

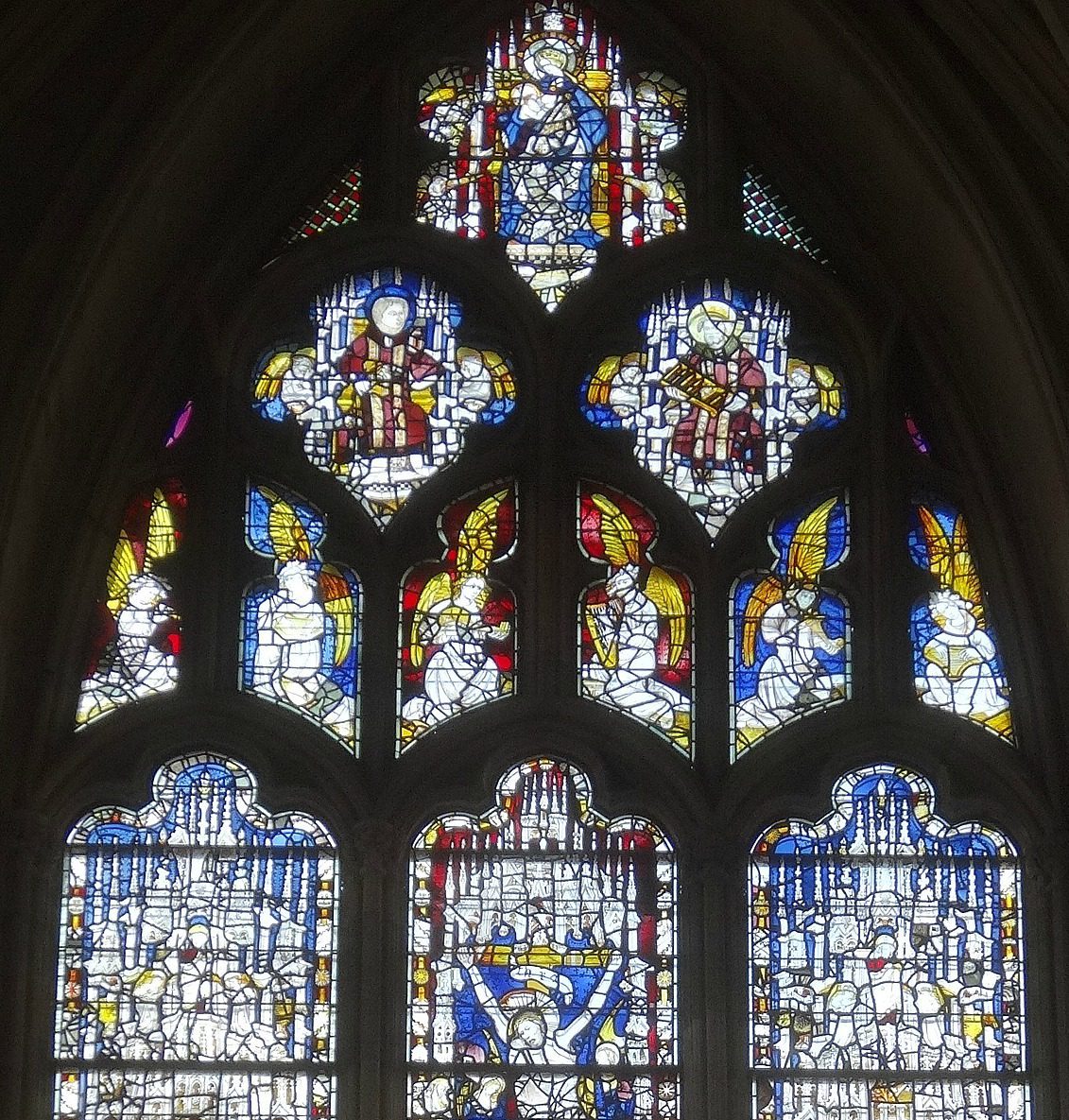

Figure 4. Detail of the upper lights of the Crucifixion Window, with the Virgin and Child Enthroned, angels, and Saints Stephen and Laurence. Photo © Budby (https://flickr.com/photos/30120216@N07/albums/72157627536552608), image cropped for detail and reproduced by permission.

The upper lights of the window show angels venerating Christ as they play their instruments among other martyrs (A1-A5). The angels’ expressions are rather neutral, but appear somewhat morose. Their heads are inclined, and some seem to look down on the crucifixion scene below them. Stephen figures again in the upper lights (B1), beside Laurence. Both deacon martyrs provide narratives of martyrdom significant to York and echo Scrope’s martyrdom. Each carries an implement important to his story: Stephen carries a book to convey his defense of his faith before a rabbinic council, and possibly to signify his reference to Christ as the Son of Man, a phrase that gets taken up in the New Testament; Laurence holds a miniature gridiron, an implement of his torture. Where Stephen’s words are said to have echoed Christ’s, in regard to forgiving those who convicted and killed him, Laurence’s reputed words are quippy – he was done on one side and should be flipped. What draws these men together, along with Archbishop Scrope buried at the foot of their images, is their willingness to stand up to authority and give their lives for causes they believed were just.

Visually connecting a history of martyrdom and saintliness with Archbishop Scrope was a significant community act. The juxtaposition, in both time and space, of a window showing Christ’s sacrifice and the archbishop’s tomb sent a clear message connecting Scrope’s actions to Christ’s sacrifice. Residents would have been very familiar with the martyrdom narratives and the stories depicted in the window at that time, and as the will of Scrope’s family member from 1451 shows, the popular name for the chapel had already become the Scrope Chapel. Through Scrope’s rebellion, the residents of York saw their own cleric defy an outside authority, seating this power in their own community. This would have been a constant reminder for residents and visitors, including nobility, of the local spirit of autonomy. Scrope was not only revered but elevated to the level of saint in his community, though he was never officially canonized. Through the association of Scrope with martyrs and saints, as well as with Christ, the rebellion with which Scrope was connected becomes less a doomed political move and more a just cause, a reminder of a city that continued to value its own autonomy and also purposefully encode that autonomy in its images and arts, creating a consistent message based in biblical history.

Bibliography

“Crucifixion, with scenes from the life of St Stephen, The.” York Glaziers Trust. https://stainedglass-navigator.yorkglazierstrust.org/window/n2-crucifixion/explore. Accessed 4/18/2022.

Davies, R. G. “After the Execution of Archbishop Scrope: Henry IV, the Papacy and the English Episcopate, 1405-1408.” Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, vol. 59, no. 1, 1976, pp. 40-74.

Fogelberg, Peter. “Coin Offerings to Archbishop Scrope’s Tomb in York Minster.” York Museums and Gallery Trust. https://www.yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk/blog/coin-offerings-to-archbishop-scropes-tomb-in-york-minster-by-volunteer-peter-fogelberg/. Accessed 6/21/2022.

McKenna, J. W. “Popular Canonization as Political Propaganda: The Cult of Archbishop Scrope.” Speculum, vol. 45, no. 4, 1970, pp. 608-623.

Osborne, John. “Politics and Popular Piety in Fifteenth Century Yorkshire: Images of ‘St’ Richard Scrope in the Bolton Hours.” Florilegium, vol. 17, 2000, pp. 1-19.

Piroyansky, Danna. Martyrs in the Making. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Surtees Society. Testamenta Eboracensia: A Selection of Wills from the Registry at York, Part II. Durham: George Andrews, 1855.

References

| ↑1 | Danna Piroyansky suggests Henry IV’s fear of “plots and uprisings, both real and imagined” contributed greatly to his initial resistance to Scrope’s following; see Martyrs in the Making (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008): 50. Regardless of the accuracy of any number, the men who had followed Scrope in the rebellion numbered in the several thousands as they met Henry’s men at Shipton Moor, concerning for any ruler, on the throne, justly or not. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Piroyansky, 52-54, discusses the narrative shift that allowed for the continued and persistent adoration of Scrope while shifting the focus away from the political aspects of his death, encouraging pilgrims to admire his saintly life, rather than his political activism and uprising for the north’s autonomy. |

| ↑3 | Following the York Glaziers Trust website numbering and identifications, beginning on the lower left and moving left to right on each horizontal register, the window includes: 1a St Stephen preaching; 1b-2b St James the Greater (glass c. 1340, thought to be part of a series of standing figures commissioned in 1339 for Archbishop Melton for the West wall, some of which are now located in other windows); 1c Pilgrims at a shrine (two women, one crowned, and one tonsured male, at a shrine, likely not original to panel); 2a Martyrdom of St Stephen; 2c St Stephen brought before the high priest; 3a-4a The Virgin Mary, under a canopy (her head is contemporary to panel, but not in its original location); 3b-6b The Crucifixion with Longinus and Stephaton, under a canopy (the shield of Clifford not original to the panel); 3c-4c St John the Evangelist, under a canopy; 5a-6a Canopy, with figure of Christ in benediction; 5c-6c Canopy, with figure of Christ in Benediction; A1-A5 Angel musicians; B1 St Stephen enthroned (his head is an insertion of c.1829); B2 St Lawrence enthroned {his head is made up of fragments of several different medieval heads); C1 The Virgin Mary suckling the Christ Child (See https://stainedglass-navigator.yorkglazierstrust.org/window/n2-crucifixion/explore). My reading focuses on the panels that are thought to have been in situ at the time of the window’s creation, and not those that have been moved to the window at later dates. |

| ↑4 | Surtees Society, Testamenta Ebroacensia: A Selection of Wills from the Registry at York, Part II (Durham: George Andrews, 1855), #30 185-186 includes a reference to burial in the “Scrop Chapell” in the north part of the Chapel of St Stephen. |

| ↑5 | John had recovered the family name and assets after another brother, Henry, a close advisor of Henry V, had been beheaded for his involvement in the so-called Southampton Plot to assassinate Henry V. Henry Scrope had been trusted by Henry V and had been given numerous commissions. John was in a position to finance a window glazing and would have been motivated to leave a lasting message as a benefit to his family name (Piroyansky, 54). |