Karl Whittington • The Ohio State University

Recommended citation: Karl Whittington, “The Cluny Adam: Queering a Sculptor’s Touch in the Shadow of Notre-Dame,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/YCIG9401.

The project of queering medieval art has followed several paths since the 1990s.[1] In an earlier essay, written a decade ago, I argued that queering a medieval object usually meant either analyzing a work “whose themes straightforwardly included sexually transgressive, playful, fluid, or otherwise non-normative sexualities,” or using a deconstructive methodology based in queer and feminist literary studies to explore an art object whose themes were not explicitly sexual or gendered, in order to read beneath the surface and expose the structures of gender and power informing its creation.[2] Since that time, new innovations in intersectional methods, trans and non-binary studies, and materiality studies have expanded both the methodologies of queer art history and the objects in its purview, as recent books by Roland Betancourt, Robert Mills, Leah DeVun and others have shown.[3] In many ways, these new directions in queering medieval art mark a return to the “open mesh of possibilities” outlined in Eve Sedgwick’s famous definition of queer studies, charting the wide range of meanings and interpretations embodied by objects rather than seeking to pin down or label particular historical identities.[4]

In my short essay for this collection, I want to explore a different method for queering a medieval object: queering the act of making itself by focusing on the physical interaction between artist and material.[5] Rather than seeking a queer identity in an artist, patron, or viewer, or exploring the rendering of a particular iconography or narrative, this essay argues that acts of making are sites that can themselves be read in sexual terms, a concept that has been frequently explored in relation to modern artists but much less often for premodern ones.[6] In later periods, artworks are more often understood to be, at least in part, expressions or extensions of self, which allows scholars to more easily make meaning from issues of identity when researching an artist’s biography or personality in dialogue with their acts of making. To hypothetically bring identity and experience to bear in the cases of essentially anonymous medieval artists requires a different set of approaches and expectations. In addition to responding to Sedgwick’s call for queer histories that embrace the “open mesh of possibilities,” this essay also responds to a later essay of Sedgwick’s where she calls for a model of history that is “reparative” rather than “paranoid.”[7] For Sedgwick, a reparative reading is one that “undertakes a different range of affects, ambitions, and risks,” as it seeks to bring “experimentation and pleasure” to the process of historical work.[8]

My case study for this reparative queer reading is a famous sculpture that has remained relatively under-studied in the field, one of those objects that most medievalists know but is too rarely engaged with directly: the statue of Adam from Notre-Dame in Paris, now kept in the Cluny Museum.

Figure 1. Adam, from the interior south transept of Notre Dame in Paris, now in Musée du Cluny, Paris, ca. 1260. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Since the first time I saw it almost twenty years ago, this statue has stood out to me as an enigma – a work that seems in many ways out of place as a nearly-nude monumental figure in the cathedral. But the statue has the potential to encapsulate particularly thirteenth-century ways of thinking about the body, the relationship of medieval artists and viewers to the classical world, and the complex idiom that many call “Gothic naturalism.”[9] What I came to see as I visited the statue a dozen times throughout the years was a series of small details on the work that testified to its complex and possibly even vexed creation, and that I believe can offer a potential opening into understanding the experience and perspective of the artist who made it. What follows is not a concrete historical claim about the artist or the sculpture, but a kaleidoscopic exploration into a whole series of readings of what the act of making this work might have meant during these years in Paris.

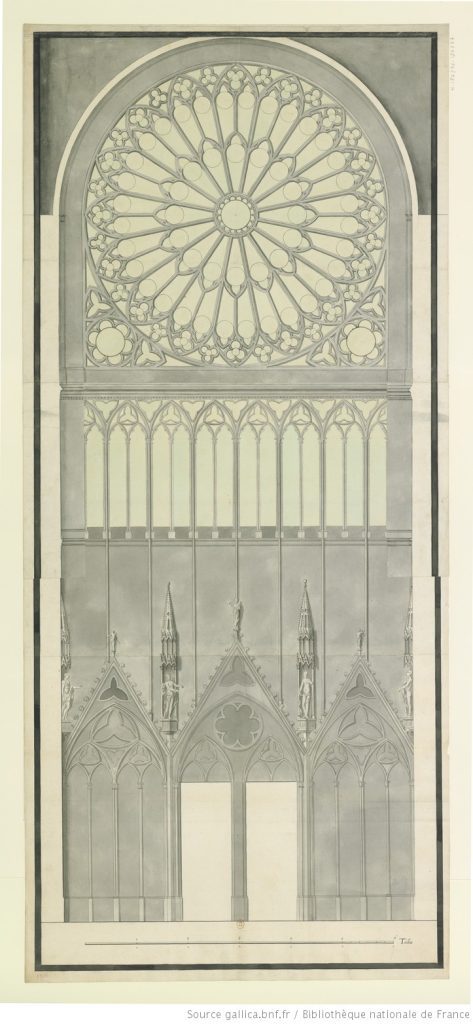

The sculpture of Adam is usually dated to around 1260 and assigned to Pierre de Montreuil, who will be introduced in greater detail below. Along with a counterpart sculpture of Eve, previously damaged and then entirely lost by the nineteenth century, it was part of a sculptural program that once ornamented the interior south transept of Notre-Dame, right around the years when the cathedral’s main fabric and decoration were brought to completion. The program included a Christ in Judgment along with Adam and Eve, an arrangement conveyed in a drawing by Germain Boffrand after Robert de Cotte at the beginning of the eighteenth century, when the statues were still in situ.[10]

Figure 2. Drawing of the interior south transept façade of Notre Dame de Paris, Germain Boffrand after Robert de Cotte, 1725. Cabinet des Estampes de la Bibliothèque nationale. Photo: BnF.

After being damaged in the French Revolution, the statue was purchased by Alexandre Lenoir for the Musée des Monuments Français and displayed in the north gallery of the cloister near the remains of the Apostles from the Sainte-Chapelle.[11] After the museum’s closure in 1816 the sculpture was sent to Saint-Denis, where it remained until it was moved to the Cluny Museum in 1887. The conservation history of the object is complex; its legs (below the knee) were badly damaged, along with portions of the arms, face, and tree trunk. Major restorations took place in its first year in the museum, as confirmed in a further restoration and cleaning in 1979. The position and gesture of the right arm, in particular, have not been definitively established; the current gesture of blessing is a result of the 1888 restoration. Restorers have also confirmed that the entire statue was originally fully painted.[12]

Occasionally misassigned to a location on the cathedral’s façade by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers, technical examination of the statue has confirmed that it was never displayed outdoors and exposed to the elements. The current understanding of the arrangement of the figures on the interior south transept façade is based largely on Antoine Gilbert’s 1821 description of the building, part of his larger catalogue of the city’s churches, later analyzed by Alain Erlande-Brandenburg.[13] Underneath the south rose window, three gables carried a statue of Christ in Judgment at the center, with two angels holding instruments of the passion atop the gables to either side. Below, in two niches, were the statues of Adam and Eve: Adam to the right of Christ and Eve to the left (this proposed arrangement departs slightly from Boffrand’s drawing, where the statue of Adam seems to appear at the far right of the interior façade, rather than closer to the figure of Christ at the center). The theme of judgment was then continued in the decoration of the rood screen, dedicated to the resurrection of the dead. The statues of Adam and Eve would thus have been viewed from far below, displayed approximately 25-30 feet off the floor, and could possibly have been slightly angled toward Christ at the center. Adam’s gaze responds to this arrangement, his head angled slightly down towards the viewer.

Standing a full two meters high, the statue of Adam is probably the most famous freestanding nude sculpture created in medieval Europe; indeed, it is one of the only medieval monumental freestanding nudes known, though some might claim that it is not actually nude, since the figure’s genitalia are covered by the leafing tree held in place by the left hand (another example of monumental nude figures are the Adam and Eve of the Adamspforte in Bamberg of ca. 1230-35). The Cluny figure is courtly and graceful, with long limbs, narrow shoulders, and calm, even features. That the sculpture must have been inspired at least in part by a classical work is clear at first glance: its monumental nudity and especially the sinuous suggestion of contrapposto or an S-curve to the body were likely inspired by a Roman work of art then in some collection in Paris (probably a carved gem, ivory, bronze, or some other small-scale object). Nude figures appear now and then in medieval sculpture; when they do, it is usually in a much smaller scale, such as in the figures of souls in last judgments (most famous and well-preserved in France are the examples on sculpted tympana at Bourges and Reims), or relief sculptures like the carving of Eve from Autun.[14] While in other periods carving a monumental nude was a mainstream endeavor, the sculptor who undertook the creation of the Adam for Notre Dame was embarking on something quite unusual in his time. What I want to do in what follows is to speculate about what it was like for this medieval sculptor to carve this statue, both physically and psychologically. Rather than primarily seeking out some queer aspect of the portrayal or iconography (one usual route of a queer art history), or thinking about the potential queer effect of viewing this nude statue (another route), I want to think instead about how we can queer the embodied experience of making a work like this. The statue’s creation would have required an incredible amount of physical proximity to this life-size nude body, in a time when the issue of same-sex relations in Paris was particularly fraught.

The sculpture is usually attributed to Pierre de Montreuil, who was active in Paris throughout the middle years of the thirteenth century and is primarily documented as an architect.[15] Numerous works are attributed to him (including, many have argued, the Sainte-Chapelle), but his only securely documented activity is as the designer of several chapels at Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris in the 1240s and as a mason at S. Denis in 1247. He is believed to have taken over the project of the interior south transept at Notre Dame in the 1260s. Sources convey nothing about his life or personality, and the fact that he is usually described as an architect certainly opens up the possibility that he was in charge of the overall design of the interior transept façade but that the actual sculpture was executed by someone else whose name remains unknown. Thus, in what follows, I’m in no way queering the historical person, Pierre de Montreuil; he is a stand-in for whoever actually made the statue. We can probably assume that the statue was carved by a man; while there were certainly women artists working in other media in Gothic Paris, I don’t know of any surviving records that suggest women were ever trained in monumental stone carving in the period.[16]

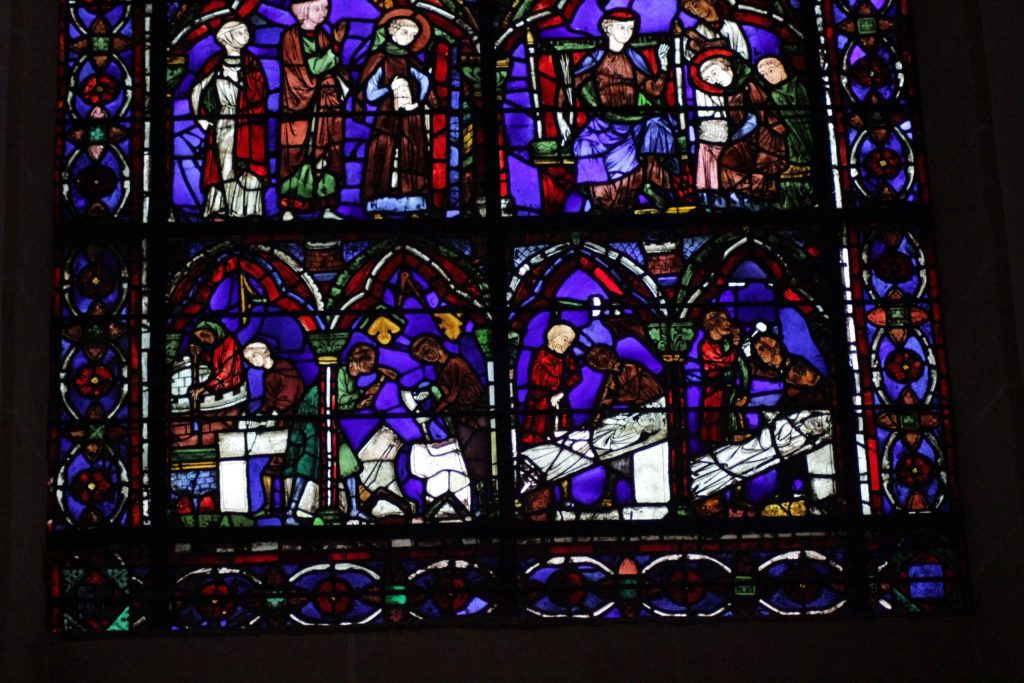

The process of carving a monumental statue like this one was an intimate endeavor that would have taken months of labor. From a small number of surviving images of medieval sculptors at work, we can get a sense of some of the techniques that would have been used.[17] After the stone was selected and the design generally blocked out into a tall rectangle, the stone would likely be laid out horizontally, as is seen in an image of sculptors and stone cutters from the bottom of the ca. 1220 stained glass window in the ambulatory of Chartres Cathedral depicting the life of Saint Chéron.

Figure 3. Carvers and Masons, Window of Saint Chéron, Chartres Cathedral, ca. 1220-1225. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The stone would have been laid out on a table or armature and the sculptor would have moved around it; eventually it would have been stood up for the final stages and worked on all sides. As the carving of the figure progressed, finishing the work would have involved scraping, filing, and polishing the stone. Too rarely, I think, do we fully recreate in our minds the amount of physical contact that would have occurred between the sculptor and the life-size body being created in stone during these long hours, days, and months. Especially in the horizontal positions shown in the Chartres window, the sculptor would have leaned against the stone, pressing their body onto it. The physical actions performed on the stone with hand, hammer, chisel, and polishing stone would have alternated between violent blows, short repetitive strokes, and soft touches, as the artist’s body interacted perhaps awkwardly with all different parts of the stone body, hovering over it or crouching beneath it. Once the statue was stood up, the sculptor may have put one arm around it while pressing their body against it to brace it for the pressure applied by files or polishing stones. A slightly later image of the sculptor at work, made in the fourteenth century for the Orsanmichele in Florence, gives a taste of this physical proximity, though it notably captures the sculptor in a moment where they don’t touch their creation at all.

Figure 4. The Sculptor at Work, Orsanmichele, Florence, 14th Century. Photo: author.

In reality, the sculptor’s arms and probably even knees would have been pressed against the hard stone flesh, bracing the sculptor’s body for the impact of the chisel or the rubbing of the polishing stone or metal file. We can understand why in this image the sculptor’s knee isn’t shown pressing against or between the statue’s legs, since it is a statue of a child and depicting this touch would have been awkward, but such physical proximity between artist and stone would have been unavoidable. In studying the iconography of Adam and Eve, scholars have moved easily between different media and also between small-scale and monumental works, but the degree of interaction, proximity, and touch between a sculptor’s entire body and the artwork was different and more sustained in monumental stone sculpture than in any other medium.

Any sculptor of monumental stone in this period would have been trained primarily in the creation of draped figures; the carving of draperies is one of the most complex and celebrated parts of the life-size sculptures that decorated the exteriors and interiors of medieval buildings. The monumental stone bodies that decorate the medieval cathedrals of northern France were largely created in and through their articulation in clothing; Jacqueline Jung argues that clothing was a primary means through which monumental sculptors emphasized the haptic presence of figures, both in the traditional sense that draperies defined bodies but also through figures’ complex and dynamic interactions with their own clothing.[18] That the sculptures of Adam and Eve from Notre Dame were monumental nudes was an unusual and significant choice, and would have constituted a real departure from what a sculptor was used to doing. We have become naturalized to viewing such unclothed figures through their endless production in other historical periods, but I think it is likely that the act of carving a nude figure like the Adam was an unusual and perhaps even fraught experience for the sculptor of this work, particularly in thirteenth-century Paris.

Paris was ruled in the 1260s by Louis IX (1214-1270), who is still celebrated today as a model of the pious Christian King; current undergraduates read in Gardner’s Art through the Ages of how he “united in his person the best qualities of the Christian knight, the benevolent monarch, and the holy man.”[19] But Louis also presided over what increasingly seem today like some of the darkest moments of Paris’s medieval history. To cite only one well-documented example, while many rulers of the time enacted anti-Semitic policies, Louis went to extremes, famously putting the Talmud on trial in 1241, and following up the trial with a massive burning of Jewish holy books in 1242 in the Place de Grève (now the plaza in front of the Hôtel de Ville) – documented at the time as up to 10,000 manuscripts confiscated from Jewish communities all over France. Louis also ruled during a period of intense discussion and regulation of homosexuality in Paris. Several recent books, particularly the studies by Robert Mills and Joan Cadden, have revealed the expansion of anti-sodomy discourses in the thirteenth century, and Mills in particular emphasizes Paris’s centrality in this history.[20] Building on the work of figures like Peter Damian, scholastic theologians associated with the university in Paris such as Peter the Chanter, William of Auvergne, Albertus Magnus, and Thomas Aquinas wrote with increasing specificity and urgency from the 1190s to the 1260s about sodomy and its legal, spiritual, social, medical, and scientific implications for life in the medieval city. Mills argues that it was positioned as a particularly urban vice, and one that was occasionally associated with the city of Paris, itself.[21] Like Michael Camille and others before him, Mills explores the visual culture of the moralized bibles created in Paris during the thirteenth century, using them as one piece of evidence for the “surge of interest in the topic of sodomy in thirteenth-century Paris, a discursive explosion generating visual as well as verbal responses.”[22] The specifics of the scholastic debates over sodomy are well discussed by others, and are perhaps not particularly important to my reading of the Adam; since my analysis is not iconographic, I am not trying to argue that the statue contributed in any particular way to either these anti-sodomy discourses or some potential resistance to them. But it is unquestionable that the artist of our statue was living and working, probably in a workshop near the new cathedral, in a time and place of incredible regulation, surveillance, and discussion of sodomy and homosexuality. Just as Florence would famously be in fifteenth century, Paris in the thirteenth century was a place where the discussion of sodomy permeated many parts of society.[23]

I know that I am not the only viewer, queer or otherwise, who finds this sculpture of Adam particularly beautiful and even in some ways erotic. The delicacy and grace of the pose, and the smooth, soft curves of the body harken back to the casual, confident eroticism of classical Greek and Roman nudes. Of course, Adam in this statue is a vision of fallen sexuality, as is indicated by his covered genitalia, though in the context of the Last Judgment the point of the iconography may have been to show that Adam and Eve were redeemed. But shame is not truly conveyed by the figure as it is in some depictions of Adam and Eve from this period; indeed, Jung emphasizes the sense of agency and intellect conveyed by Adam’s firm press of the fig leaf against his groin.[24] The statue would have intersected with a broad range of theological writings about Adam and Eve’s role in salvation history, and its particular pose and attributes may have contributed to its precise meanings for viewers, but I’m not interested here in iconographic meaning. While the precise iconography of the figure may have been critical in the conceptualization of the statue by the planner of the overall sculptural program, I think it was unlikely that it was much on the mind of the artist for the majority of the long hours and days that he worked on the statue. Despite the vital role played by Adam in the story of salvation, and the privileged location that the statue was planned to occupy, I am more concerned with the mundane experiences of the carver, who I think is unlikely to have had a simple reaction to what he was carving.[25]

We know nothing of the sculptor’s identity, so let’s imagine him with a whole range of potential identities or personalities as we hypothesize what his experience carving the statue might have been like. If the sculptor was one of the many men documented in Paris who felt an attraction to other men (after all, the numerous legal regulations would likely not have been put in place in thirteenth-century Paris if same-sex activity was not perceived as a widely present), then the physical act of carving this statue could have been charged with erotic potential or even longing. Scholars have debated the possible use of a live model for the figure; most agree that this is unlikely, but, if our sculptor were attracted to other men, his delicate and nuanced Christian recreation of a classical nude could have been informed by a longstanding appreciation of male physical beauty, either observed furtively in the world, at his leisure in sexual or romantic encounters, or through the appreciation of Classical artworks. At the same time, our imagined “queer” sculptor’s long hours creating this nude statue may have been fraught with fear that his attention and work on the figure might reveal his desires. Conversely, if our sculptor was “straight” (for lack of a better term), he might also have found the intimate process of carving this nude male figure to be uncomfortable, perhaps finding himself the butt of jokes made by others in the workshop as he braced and pressed his warm flesh against the cold marble flesh of the statue while carving or polishing it. Either of these two readings – of a “queer” artist lovingly crafting an object of desire like Ovid’s Pygmalion or of a “straight” artist made uncomfortable by the act of carving a male nude – can be supported, I think, through looking at the statue in closer detail.

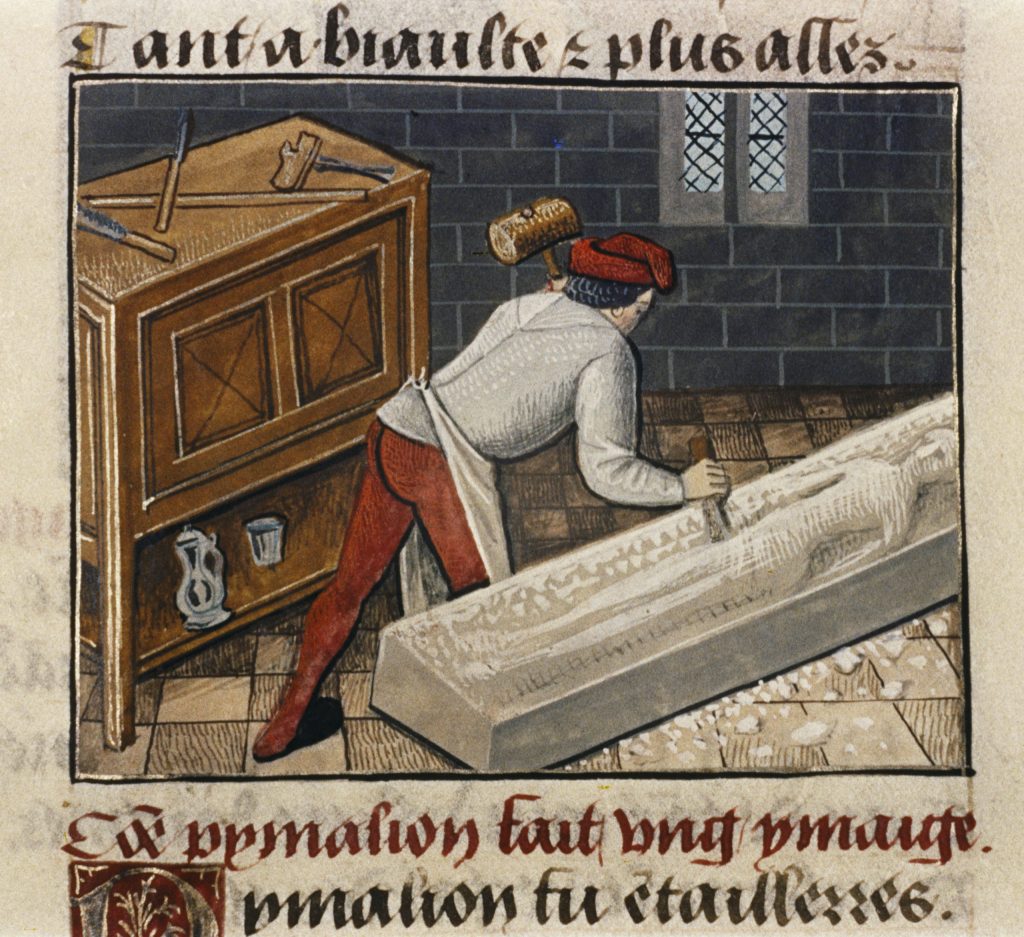

Pygmalion is an apt figure to consider in relation to the potential sculptor of the Adam.[26] In Ovid’s story, the sculptor fell in love with the statue that he had carved from ivory, and prayed to Aphrodite that it be brought to life. The story was incredibly popular during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, particularly because of its re-telling in the Roman de la Rose; manuscript paintings of Pygmalion, particularly in copies of the Roman de la Rose, emphasize the intimate connection between sculptor and sculpture, and the chisel as a phallic extension of his body (see Figures 5 and 6).[27]

Figure 5. Pygmalion, Bibliothèque Nationale de France BNF Fr 19156, 14th century. Photo: BnF.

Figure 6. Robert Testard, Pygmalion, from Ms. Douce 195, f. 149r, late fifteenth century. Photo: The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

Indeed, these images of Pygmalion at work often emphasize the formative and more aggressive sculptural moments with chisel and hammer, rather than the more sensual and potentially erotic filing and polishing that would have taken place afterward. Though in Ovid’s narrative Pygmalion carves the woman out of ivory, manuscript paintings of the sculptor usually show him working in a scale only possible with stone, carving a life-size figure in order to make the erotic connection between the two figures more plausible and palpable. The sculpture of Adam follows the statue of Pygmalion’s woman in its nudity and graceful beauty, and the sustained medieval interest in the story showed the fascination that medieval people had with it, as it intersected with critical ideas about creation, idolatry, and the allure of art.

Indeed, we can imagine many other reasons why the creation of this work may have been vexed for the sculptor. Numerous medieval images depicting God as an artist or sculptor in his creation of Adam, such as an example on folio 6v in the twelfth-century Lambeth Bible in which God seems to mold and shape Adam from clay with his hands, reveal that artists frequently ruminated on their status as divine creators. This conceptualization of their role as divine creators may have been especially poignant in creating a life-size image of Adam.[28] And the statue’s nudity and pose would inevitably have prompted reflections on idolatry and antiquity. Casting Adam almost as an enticing Apollo or Dionysus rather than a fallen mortal was a charged act in the thirteenth century, and as has been seen in the lengthy discussions of how to read “classicism” in Gothic sculpture (such as in the famous “antique” figures on the Reims west façade), the question of how exactly such antique references were meant to be read remains unsettled. Camille argued in an oft-cited formulation that “the aesthetic anesthetizes” – that despite other contemporary works that reveal longstanding medieval concerns over idolatry, often projected onto “others” such as Muslims and Jews, medieval people could also enjoy classical beauty on its own terms, its loaded borrowing tamed through beauty. But rather than a true example of Panofsky’s “principle of disjunction,” in which form and content are split and classical forms can be borrowed without any ideology attached, the sculpture of Adam resembles more Camille’s description of a creative reformulation of a classical source in Christian terms.[29] The statue operates at the intersection of Christian nakedness and Classical nudity, with Adam’s protective gesture signifying the nakedness typical of Adam and Eve in the period but his monumental presence in stone and sinuous eroticism conveying classical associations.

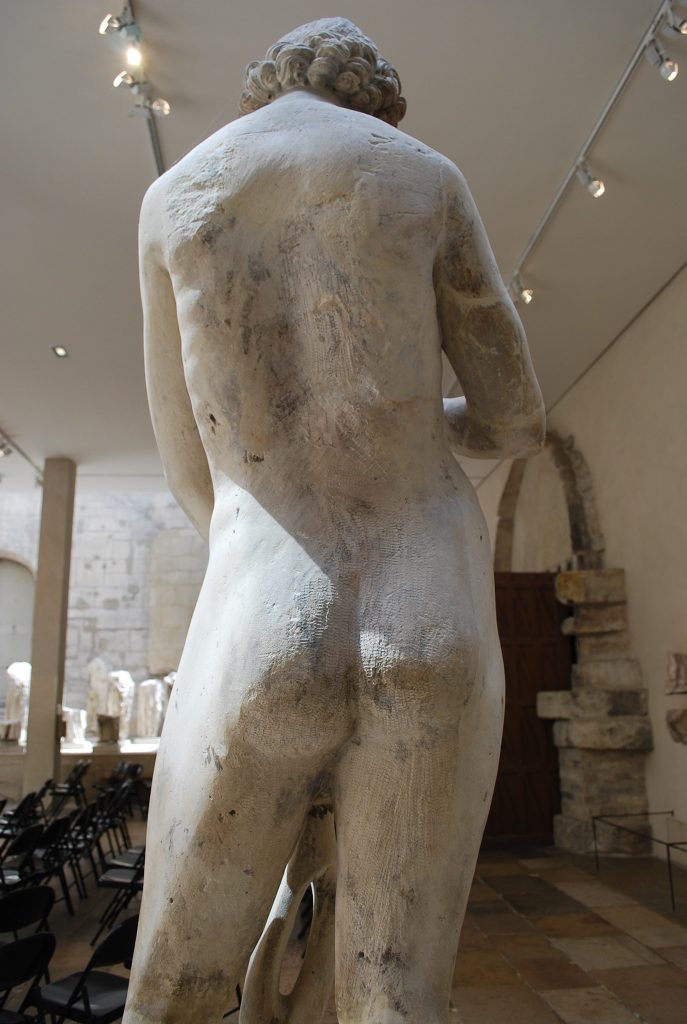

But it is above all in the smooth and delicately crafted details of Adam’s body that I think we see the potential evidence for the sculptor’s complicated investment in the beauty of the body: the smooth flesh of the abdomen, with its combination of some musculature with a softness more associated at the time with female figures, stands out, as does the figure’s sinuous curving waist and buttocks.[30] The figure’s nudity and humanity is not something painted onto the exterior through classical quotation, as I think is seen in a work like the Genesis reliefs on the façade of Orvieto Cathedral; in that work, Adam is rendered in a Late-Antique idiom, likely inspired by sarcophagi, but his body looks like a quotation rather than an embodiment, in part because of the figures’ small scale.

Figure 7. Lorenzo Maitani (?), Creation of Adam, façade of Orvieto Cathedral, ca. 1310. Photo: Author.

Another example, far more extreme, of a medieval copy of a classical figure that traces exterior patterns of the body without the eroticism or confidence of the likely original is Villard de Honnecourt’s drawing on folio 22r of his “sketchbook”; while Villard was incredibly expert at conveying things like drapery folds when he copied gothic sculptures, his drawing after a classical nude seeks to map the contours of the body’s musculature but not its embodied presence.[31] These examples, whether the aestheticized classicism of the Orvieto reliefs or the awkward documentary body of Villard’s drawing, stand in contrast to the complex self-knowledge conveyed in the Adam – his “agency,” as Jung argues. The figure’s evident engagement with the viewer, and the relaxation and calmness conveyed in both his pose and expression, contribute to the confidence of the figure that is so different from other renderings of Adam in relief sculpture or manuscript painting of the period.

But while some aspects of what I am arguing is the figure’s eroticism are conveyed to the public at a distance, other key details would have remained unseen. The fact that the buttocks of the figure are carved fully in the round, when the sculpture was meant to be placed against a wall, is noteworthy.[32] In a wonderful new 360-degree scan of the sculpture on the Cluny Museum’s website, viewers can zoom in on some of these details, noting the round fullness of the buttocks, unusual in depictions of men at this time.[33] But in this same area, we find tantalizing evidence of the sculptor’s potential discomfort. While other parts of the back of the figure, such as the shoulders and the sides of the back, are smoothed and polished to a higher degree of finish, the buttocks themselves, while amply carved and fleshed out, have not been polished – we see clear chisel marks remaining across this entire area of the body.

Figure 8. Adam (detail), from the interior south transept of Notre Dame in Paris, now in Musée du Cluny, Paris, ca. 1260. Photo: author.

As far as I can ascertain, the buttocks are not a part of the statue that has been extensively restored.[34] Could these unfinished marks suggest an unwillingness or discomfort with undertaking the hours and days of sanding and polishing this part of the body that it would have taken to bring it to the degree of finish seen on the front of the statue?[35] This might seem like baseless speculation, but perhaps not if we try to imaginatively recreate again the mundane atmosphere of a medieval sculptor’s workshop in the shadow of Notre Dame. In a space likely shared by at least half a dozen men, we have to imagine the artist of the Adam seated on a low wooden stool, his face only inches from the plump, round backside of the figure he has created, working with file, sand, and/or pumice to repetitively grind away the chisel marks and create a smooth polished surface, and to incise and mark the crease between the buttocks leading down to the legs. We can easily imagine the jokes and taunts of coworkers as he worked on this delicate task, which indeed he seems to have abandoned, either out of frustration, annoyance, discomfort, or embarrassment. (We certainly know from a variety of popular sources at the time that men teased each other with slang words and insinuations of homosexuality, then as now).[36] While we can imagine a more mundane reason why the rear of this figure might not have been finished to the degree that the front was, I think we can learn a lot by thinking about the sculptor’s material process: his physical intimacy with the work, and the parts of the surviving sculpture that may testify to his careful attention to the work’s eroticism on the statue’s front and also to its denial on its back. It is the interplay between the high level of polish in certain parts of the statue and the unfinished quality of the buttocks that I find so suggestive. The figure’s thighs, abdomen, and face have clearly been labored over and carefully polished; we can almost sense the way that the sculptor zeroed in on these areas when finishing the work. But when it came to the rear of the statue, he was unable or unwilling to engage in the repetitive motion of polishing around the figure’s buttocks, though it was completed on parts of the upper back and legs.

The loss of the corresponding statue of Eve is significant; it would be fascinating to know whether that sculpture also contained key erotic areas that remained unfinished. It is also compelling to try to imagine the experience of the same sculptor creating both statues. Carving and polishing the Eve would have obviously required the same bodily engagement as the Adam, placing the sculptor in equal proximity and intimacy to her stone body. If we imagine that the Eve was carved with the same softness and sensuality as the Adam, we uncover a new layer of the psychic engagement of the sculptor – a kind of complex bisexuality in his artistic role (if not necessarily his actual identity) as he assumed the role of both creator and intimate material and psychological companion to the works during their lengthy period of creation and finishing.[37] Knowing what the Eve looked like – her pose, attitude, and degree of finish – could have provided further evidence for a particular psychological reading of the artist. If she lacked the evident eroticism of the Adam we might read it as evidence of the sculptor’s greater interest in the Adam, either because of a queer attraction to the figure or an identification with it. If her eroticism were even more pointed than the Adam’s, the opposite could be argued. And if every part of both the front and back of her body were highly polished and finished, unlike the Adam, it would perhaps indicate a lack of the anxiety that I argue is revealed on Adam’s buttocks. If the creation of monumental nudes like these would inherently involve reflections on the sculptor’s part concerning his own sexuality and humanity, as I think it must have, then we have to assume that his mental or emotional engagement with the Adam and the Eve would have been different in meaningful ways.

We will never know for certain who carved these sculptures of Adam and Eve for Notre-Dame. We will never know how the artist felt while making the pieces, or exactly how others responded when they saw them being made in the workshop or installed in the new cathedral. But in this essay, I have tried to open a space where the sexuality of an unknown medieval artist—whatever that sexuality was—could mean something in the context of their embodied material process in creating a work like the Cluny Adam. No matter what that sculptor’s reaction to or relationship with this sculpture was, I feel convinced that in some way his sexuality mattered to the way he felt, both as he labored to carve the body and as he chose to leave part of it unfinished. For a work like the Cluny Adam, queering the artist can just mean acknowledging that his sexuality, whatever it was, existed and mattered.

References

| ↑1 | Scholars who have contributed in significant ways to the project of queering medieval art history include Michael Camille, Karma Lochrie, Robert Mills, Gerald Guest, Martha Easton, Bryan Keene, Roland Betancourt, and Leah DeVun, among others. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | See Whittington, “Queer,” Studies in Iconography 33 (2012), 157-168. This piece has a much longer discussion of the historiography and methodologies of queer medieval art history up to 2010. |

| ↑3 | See Roland Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), Robert Mills, Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), and Leah DeVun, The Shape of Sex: Nonbinary Gender from Genesis to the Renaissance (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021). |

| ↑4 | See Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), 8. For bibliography on other key definitions and early work on queer studies, see Whittington, “Queer.” |

| ↑5 | For an interesting example of a similar queering of the physical/material act of creating an object, though one that is more focused on the erotics of collaboration, see Aaron Hyman, “Brushes, Burins, and Flesh: The Graphic Art of Karel van Mander’s Haarlem Academy,” Representations 134 (2016), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2016.134.1.1 |

| ↑6 | For analysis of modern/contemporary examples where the artist’s act of making, and even the materials themselves, can be understood in sexual terms, see, for example David Getsy, Abstract Bodies: Sixties Sculpture in the Expanded Field of Gender (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), Getsy, Rodin: Sex and the Making of Modern Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), Andrew Perchuk and Helaine Posner, ed., Masculine masquerade: masculinity and representation (Cambridge: MIT, 1995), and Marcia Brennan, Modernism’s Masculine Subjects (Cambridge: MIT, 2004), among many other examples. |

| ↑7 | Sedgwick, “Paranoid reading and reparative reading, or you’re so paranoid, you probably think this essay is about you,” in Touching Feeling, ed. Barale, Goldberg, Moon, and Sedgwick (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002), 123-151. Thanks to the anonymous reviewer for Different Visions who reminded me of this other essay by Sedgwick. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822384786-005 |

| ↑8 | Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading,” 150 and Heather Love, “Truth and Consequences: On Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading,” Criticism 52, no. 2 (2010), 235-241, 236. https://doi.org/10.1353/crt.2010.0022 |

| ↑9 | My understanding of the history and historiography of Gothic naturalism is most influenced by Jean Givens, Observation and Image-Making in Gothic Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005). |

| ↑10 | The 1725 copy after de Cotte’s drawing is by Germain Boffrand (1667-1754), and is in Bibliothèque Nationale, Cabinet des Estampes, Va 442, dessin 1836. https://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb402720718 |

| ↑11 | On the histories of the display of the statue, as well as the historiography of debates over its original location, see Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, Les sculptures de Notre-Dame de Paris au musée de Cluny (Paris, 1982), 114-118 and Erlande-Brandenburg, “L’Adam de musée de Cluny,” La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France 24, no. 2 (1975), 81-90. |

| ↑12 | On the restoration history of the statue, see Erlande-Brandenburg, Les sculptures de Notre-Dame de Paris, 117-118. |

| ↑13 | See Antoine Pierre Marie Gilbert, Description historique de la basilique métropolitaine de Paris (Paris, 1821), 200. |

| ↑14 | On the nude in medieval art, see especially Sherry Lindquist, ed., The Meanings of Nudity in Medieval Art (London: Routledge, 2012). |

| ↑15 | On Pierre de Montreuil, see especially Louis Grodecki, “Pierre, Eudes et Raoul de Montreuil à l’abbatiale de Saint-Denis,” Bulletin monumental 122 (1964), 269–74, Robert Branner: St Louis and the Court Style in Gothic Architecture (London: Zwemmer, 1965), 143–6, and Robert Suckale, “Pierre de Montreuil,” Les Bâtisseurs des cathédrales gothiques, ed. Roland Recht and Jacques Le Goff (Strasbourg: Editions Les Musées de la ville de Strasbourg, 1989), 181–5. https://doi.org/10.3406/bulmo.1964.8892 |

| ↑16 | Despite the lack of evidence for women’s participation in the creation of monumental sculpture, recent scholarship has documented the extensive participation of women in the making of medieval artworks; see especially Therese Martin, ed., Reassessing the Roles of Women as ‘Makers’ of Medieval Art and Architecutre (Leiden: Brill, 2012). Interestingly, by the late fourteenth century, it was at least possible to imagine a female sculptor; several illustrations to Boccaccio’s De mulieribus Claris include depictions of women created sculpted objects. Thanks to one of the anonymous reviewers for this reference. |

| ↑17 | For a recent collection of essays on medieval limestone techniques, see Vibeke Olson, ed., Working with Limestone: The Science, Technology, and Art of Medieval Limestone Monuments (Ashgate, 2011). For broader reflections on the engagement of medieval sculptors with different kinds of materials, see Paul Binski, Gothic Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), especially Chapter 4. On issues related to the physical encounter (real and imagined) between sculptor and material, see the essays in Peter Dent, ed., Sculpture and Touch (Abingdon: Routledge, 2020). |

| ↑18 | Jung, Eloquent Bodies: Movement, Expression, and the Human Figure in Gothic Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2020), 41. |

| ↑19 | Fred Kleiner, Gardner’s Art through the Ages: A Global History (Boston: Cengage: 2015), 390. |

| ↑20 | Mills, Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages and Cadden, Nothing Natural is Shameful: Sodomy and Science in Late Medieval Europe (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/119.5.1760 |

| ↑21 | Mills, Seeing Sodomy, 74. The decoration of Gothic churches has long been noted to have often been targeted at curbing the vices of the city; see, for example, Gerald Guest, “The Prodigal’s Journey: Ideologies of Self and City in the Gothic Cathedral,” Speculum, 81.1 (2006), 35-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0038713400019370 |

| ↑22 | Mills, Seeing Sodomy, 30. |

| ↑23 | Whether or not one agrees with the “Boswell thesis” that the earlier Middle Ages was a time of greater tolerance of same-sex desire, most scholars agree that anti-sodomy discourses and regulations expanded in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Mills’ recent book is the best treatment of these questions, but for the formative works of the discourse, see John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), R.I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Power and Deviance in Western Europe: 950-1250 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1987), Mark Jordan, The Invention of Sodomy in Christian Theology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), and Matthew Kuefler, ed., The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006 |

| ↑24 | Jung, Eloquent Bodies, 37. |

| ↑25 | My approach to thinking about the everyday experiences of medieval artists, as well as my method for trying to imagine the psychic and physical toll of working with particular materials, is greatly influenced by Michael Camille’s book on the Parisian illuminated Pierre Remiet; see Camille, Master of Death: The Lifeless Art of Pierre Remiet, Illuminator (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996). |

| ↑26 | For a discussion of imagery of Pygmalion in the later Middle Ages, with extensive notes on the earlier scholarship, see Marian Bleeke, “Versions of Pygmalion in the Illuminated Roman de la Rose (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Douce 195): The Artist and the Work of Art,” Art History 33, no. 1 (2010), 28-53 and Victor Stoichita, The Pygmalion Effect (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), Chapter 2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.2009.00721.x |

| ↑27 | Both Marian Bleeke and Michael Camille make a similar observation about the phallic dimensions of Pygmalion’s tools in these examples; see Bleeke, “Versions of Pygmalion,” 39 and Camille, The Gothic Idol: Ideology and Image-Making in Medieval Art (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 326. |

| ↑28 | For the image from the Lambeth Bible, see Camille, The Gothic Idol, 33. On the artist as divine creator, among many interesting works see especially Conrad Rudolph, “In the Beginning: Theories and Images of Creation in Northern Europe in the Twelfth Century,” Art History 22 (1999), 3–55, Ittai Weinryb, “Living Matter: Materiality, Maker, and Ornament in the Middle Ages” Gesta 52 (2013), 113-132, and Beate Fricke, “Artifex and Opifex – The Medieval Artist,” in A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic and Northern Europe, Second Edition, ed. Conrad Rudolph (London: Blackwell, 2019), 45-70. |

| ↑29 | Camille, The Gothic Idol, 102-103. For further discussion of Panofsky’s principle of disjunction, see Dale Kinney, “Spolia,” in A Companion to Medieval Art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe, ed. Conrad Rudolph (London: Blackwell, 2006), 233-252. |

| ↑30 | For interesting discussions of softness/delicacy in medieval monumental statues of female figures, see for example Binski’s discussion of the ca. 1313 statue of Mary Magdalen from Ècouis in Binski, Gothic Sculpture, 164-167. |

| ↑31 | For this drawing, see the digitized version of the manuscript on the BnF website: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b10509412z/f45.item |

| ↑32 | For a fascinating later history of the rear view of the male nude, see Patricia Rubin, Seen from Behind: Perspectives on the Male Body and Renaissance Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018). |

| ↑33 | https://www.musee-moyenage.fr/collection/collections-3D/adam-3d.html While I observed these unfinished qualities in person numerous times, I don’t have my own detailed photographs of them yet because of the difficulty of travel during the Covid-19 pandemic. But all of the details can be easily seen on the museum’s 360 scan of the object. |

| ↑34 | See Erlande-Brandenburg, Les sculptures de Notre-Dame de Paris, 117-118. |

| ↑35 | For interesting ruminations on unfinished works, see the Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible, ed. Kelly Baum, Andrea Bayer, and Sheena Wagstaff (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016). |

| ↑36 | On medieval slang terms for homosexuals, as well as various body parts, see Michael Camille, “For our devotion and pleasure: the sexual objects of Jean, Duc de Berry,” Art History 24, no. 2 (2001), 169-194, esp. 172, and Mills, Seeing Sodomy, 81-82, 275-77. The anal humor of contemporary medieval manuscript marginalia also testifies to the widespread presence of jokes about anal penetration in the period. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8365.00259 |

| ↑37 | Many thanks to Trenton Olsen for his suggestion about considering this aspect of the Eve sculpture and the idea of the bisexuality of creation that is implied here. |