Sarah Ganzel • University of Wisconsin, Madison

Recommended citation: Sarah Ganzel, “Swearing Oaths, Touching Books, and Embodying Christ: The Social Life of the Arenberg Gospels,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.61302/AHFA7102.

People swore oaths of office, oaths of fealty, and legal oaths on books of sacred scripture in the Middle Ages—often on older books designated for specific use as oath books. However, few studies have examined these books and the full meaning of their usage, especially in terms of their materiality or “social life.” This article investigates the history of the Arenberg Gospels (Morgan MS M.869), a deluxe gospel book from Christ Church, Canterbury, c. 990–1010, that served as an oath book at the church of St. Severin in Cologne in the fourteenth through eighteenth centuries.[1]

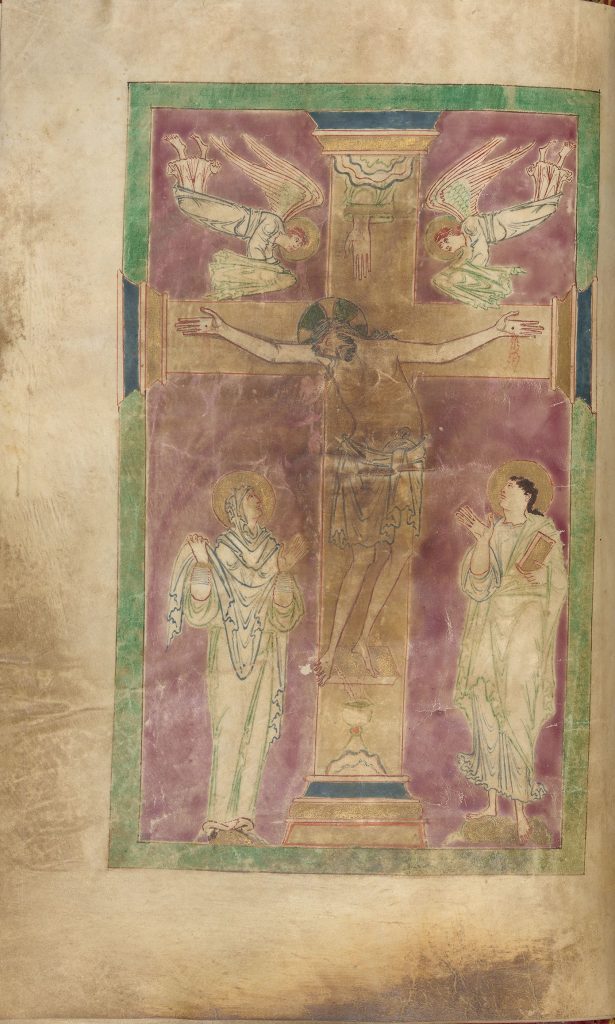

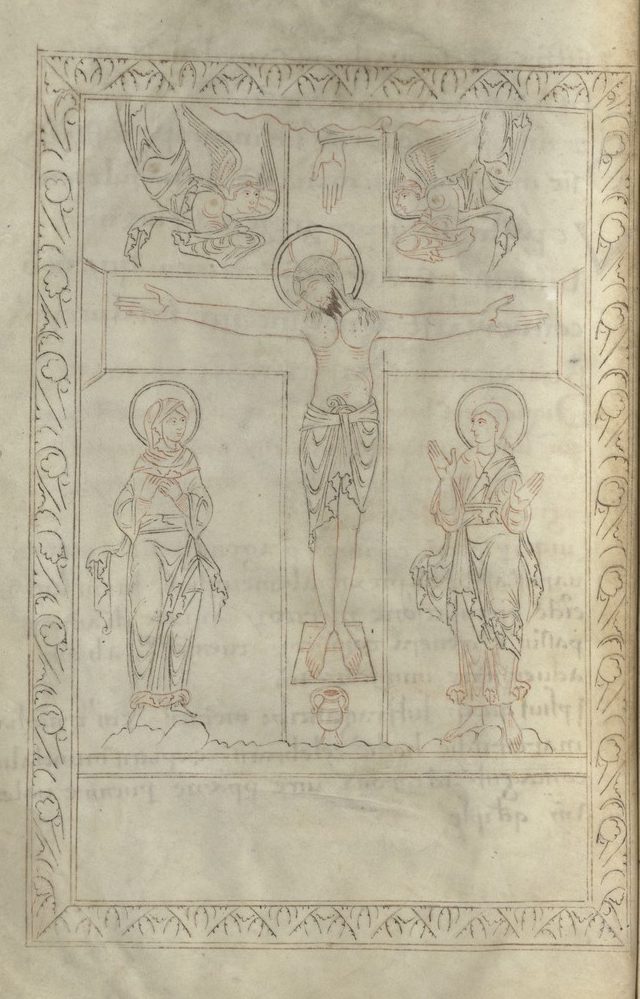

The life of the Arenberg Gospels is revealed on its pages.[2] It is an illuminated manuscript on moderately heavy, grayish vellum, and its leaves are arranged in the old Insular method.[3] The book’s antiquity and foreignness may have made it more attractive as an object of legal standing. In addition to the heavily soiled Crucifixion miniature on fol. 9v on which church officials at St. Severin swore oaths of office (Fig. 1), the corners of many of the book’s pages have darkened, and several of the oath formulae in the opening quire have flaked.[4] The eponymous Duke of Arenberg, a later owner, cut and rebound the manuscript when it entered his collection in the nineteenth century, but there are no records of the book having been cut or rebound prior.[5] Regardless, the manuscript’s original binding was likely ornate, as Christians typically displayed gospel books on the altar during the liturgy and lavishly bound them to reflect their hallowed status.[6] The manuscript measures a moderate 302 x 191 mm and contains 167 leaves, making it easily transportable, and it changed hands multiple times throughout its life.

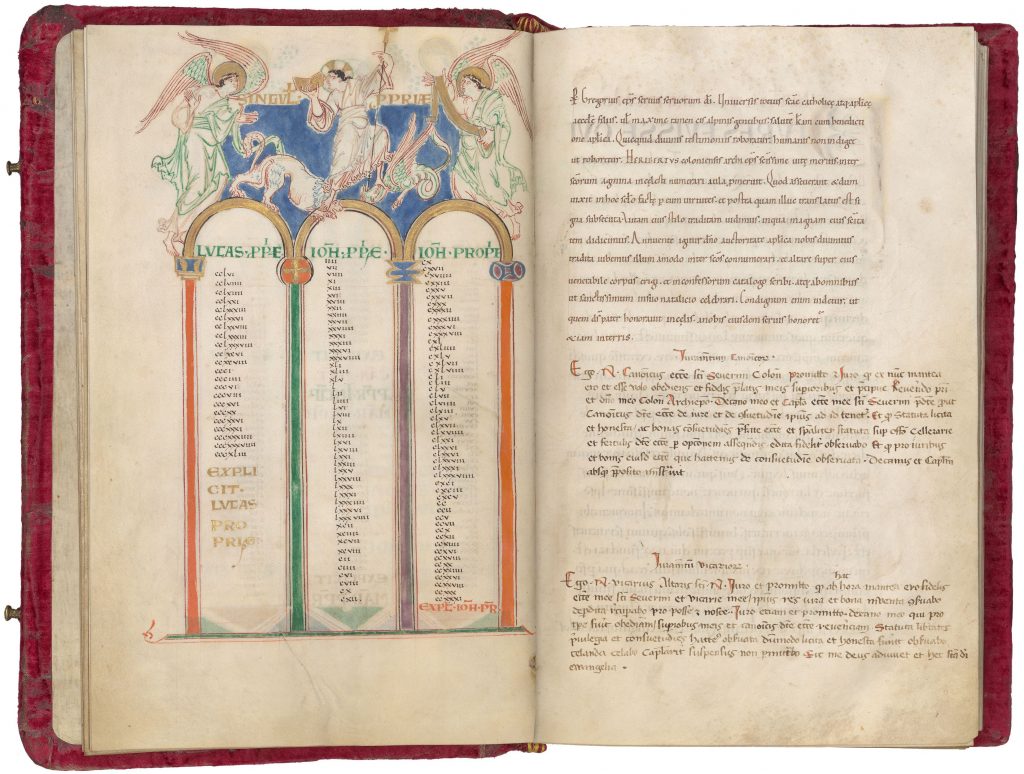

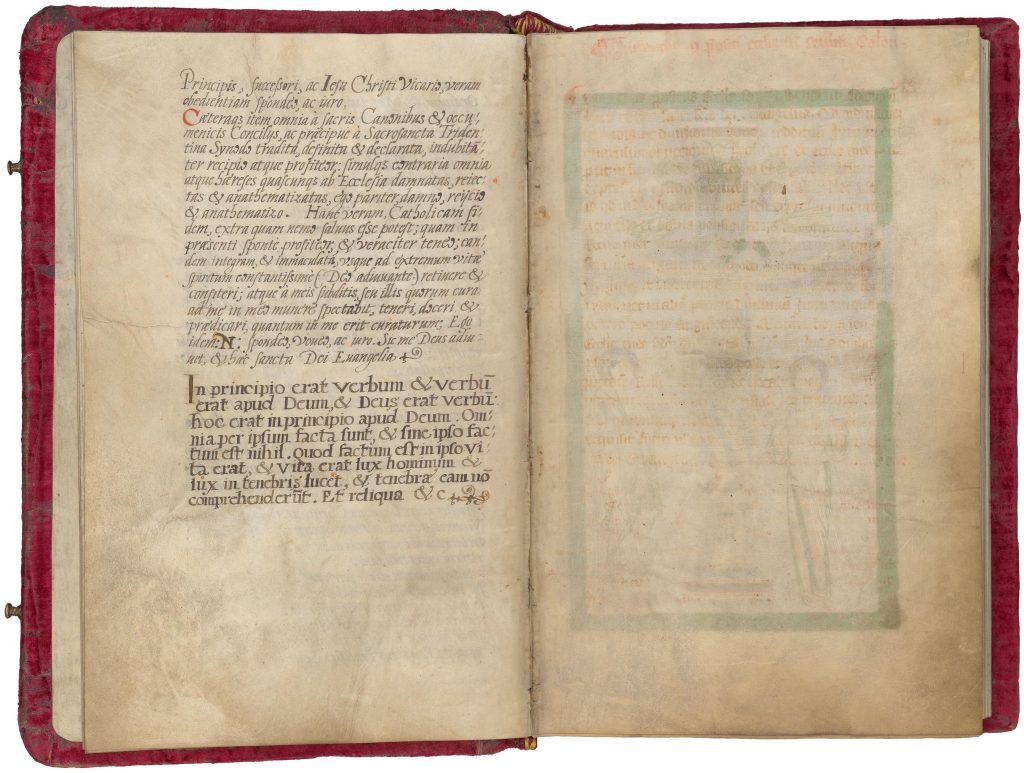

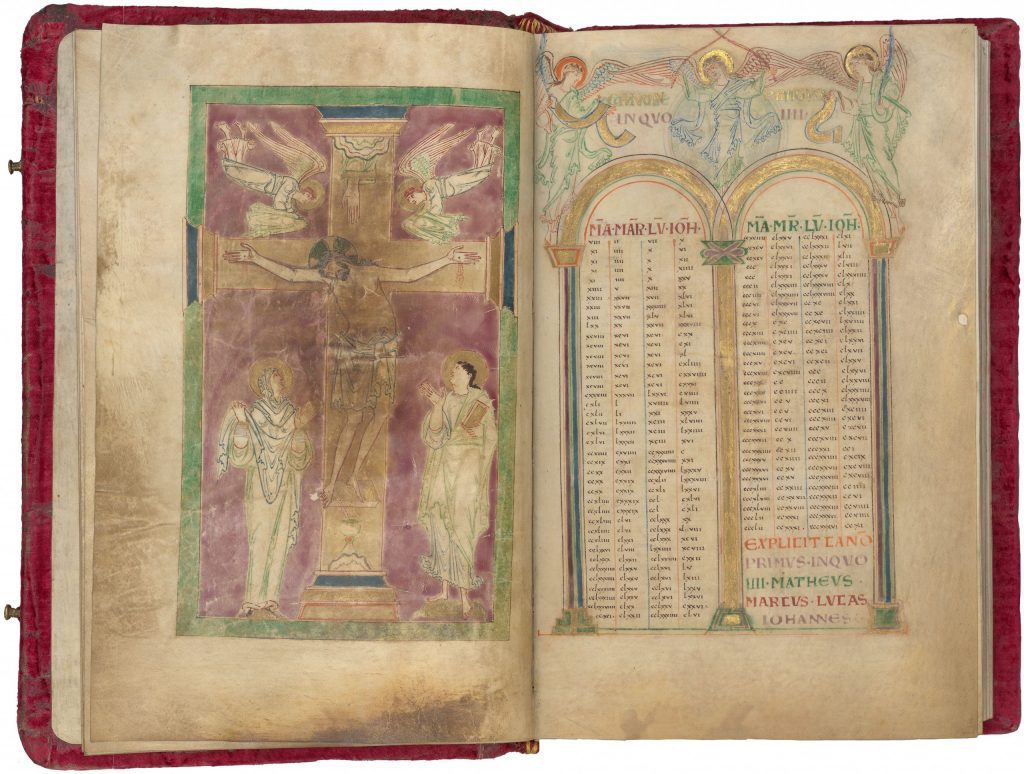

The manuscript shows signs of almost continuous use from its creation. Marginal notes indicate the book was used in England around the time of its production, and an early twelfth-century copy of a papal decree canonizing Archbishop Heribert of Cologne as a saint on fol. 14 indicates it reached Cologne by then (Fig. 2).[7] Though the manuscript’s provenance during the eleventh through thirteenth centuries is unknown, the oath records evidence that the collegiate church of St. Severin owned the manuscript from at least the century that followed. Church officials recorded oaths in Latin and German on fols. 1–9 in the book’s opening quire, which they inserted early in the manuscript’s use in oath rituals, fol. 14r, and fols. 124r–126r.[8] The oath records date to the fourteenth through seventeenth centuries, and extra appended but miscellaneous documents are included on fols. 6r–8v (Fig. 3), which date to the sixteenth century.[9]

The Arenberg Gospels mediated the divine from its earliest usage, but, in its role at St. Severin, it was charged with mediating church officials’ oaths to God in the church’s officiation rituals. The now badly damaged Crucifixion miniature on which church officials swore effectively materialized the body of Christ in vellum and thus co-produced and physically manifested officials’ exchanges with divinity.[10] This paper argues that church officials interpreted the Crucifixion miniature’s material transformation as a message to suffer and serve, thus making officials ideal vassals by obligating them to embody Christ’s sacrificial virtues in service of the Church.

Fig. 1. Crucifixion, Arenberg Gospels (Fol. 9v), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0039-0040.jpg.

Fig. 2. Canon tables, Gregorius VII’s decree of St. Heribert’s canonization, and oaths of the canons and vicars, Arenberg Gospels (Fols. 13v–14r), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, 12th- and 14th-century inscriptions, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0047-0048.jpg.

Fig. 3. Articles of faith prescribed for the clergy, John 1:1-5, and erased oath, Arenberg Gospels (Fols. 8v–9r), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, 16th-century inscriptions, ink on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0037-0038.jpg.

Oath Objects

The practice of swearing oaths on precious objects both predates and parallels the use of oath books among Christians, suggesting that the tangible things on which people swore were vital to oaths’ meaning and veracity across cultures. For example, ancient and post-Mishnaic Jewish communities swore oaths to God while holding a Torah scroll, while Germanic peoples swore more political fealty oaths on precious items, such as swords or rings.[11] Jews, Germanic polytheists, and Christians alike believed that oath objects acted as channels to divinity.

As such, the movements people channeled through these objects mattered. Due to the medieval emphasis on iconic bodily movements in ceremonial communication, these gestures may have contributed even more to the oath ritual’s meaning than the spoken oaths.[12] Notably, people often sealed both Christian oaths and Germanic fealty oaths with a kiss. In the latter context, lords and vassals kissed each other on the mouth to confirm their mutual fidelity, though this kiss was subordinating as well, especially when accompanied by the vassal’s genuflection.[13]

By the late Middle Ages, Christians confirmed their promises by touching or kissing oath books, which were usually repurposed gospel books.[14] Christian oaths developed in concert with liturgical practices and were often sworn on liturgical objects, such as reliquaries, in ecclesiastical settings in the early medieval period.[15] Kissing the Gospels in oath rituals thus paralleled the priest’s kiss of the Gospels during the Mass, with the latter kiss marking the commencement of and culmination to Communion with the Church and with Christ in his Eucharistic nature.[16]

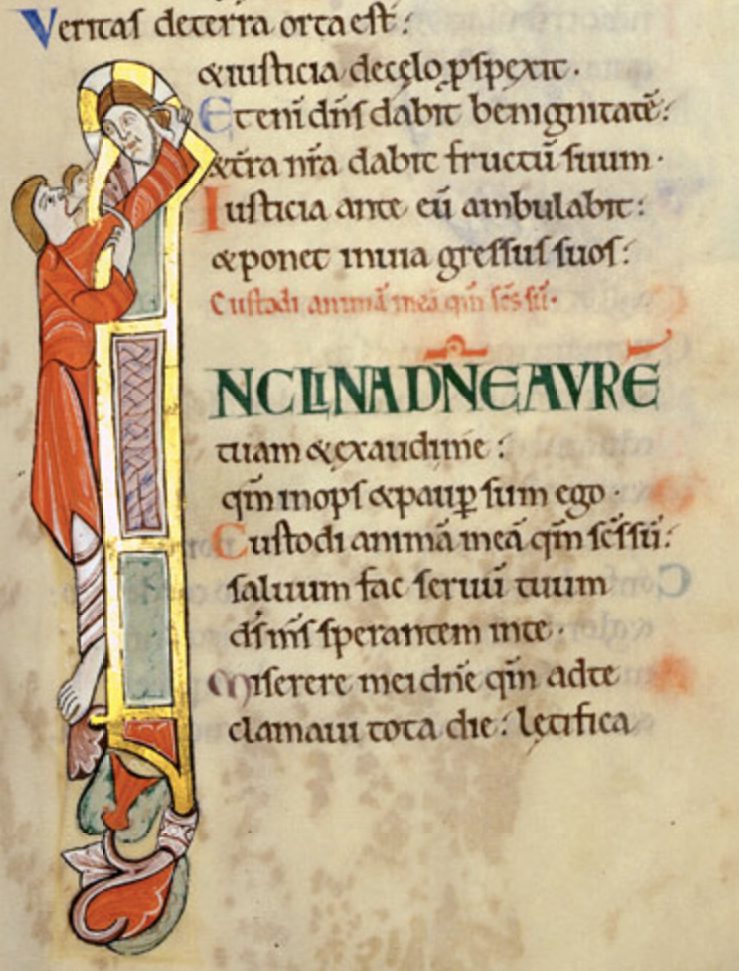

In the Mass, the kiss was also believed to unite souls. In fact, the mouth may have been thought of as the bodily locus or at least the entrance or exit location of the soul, as artists often portrayed the soul emanating from the mouth at death.[17] In an example that is not a death, a historiated initial in the Albani Psalter depicts the soul of a psalmist as a small figure issuing forth from his mouth (Fig. 4).[18] The psalmist plucks at God’s ear and points to his soul, and the accompanying verse reads “Bend your ear lord and hear me: because I am destitute and poor. Defend my soul because I am holy.”[19] Thus, souls could be said to pass through the mouth. Notably, prior to the Gospel lection, the officiant blessed the deacon and affirmed that God would live in his heart and mouth for the reading.[20] The priest’s kiss of the gospel book thus represented his soul’s communion with Christ during the Gospel lection, much like the kiss of peace was believed to unite Christ’s soul with the souls of his mystical body.

Fig. 4. Psalmist plucking at God’s ear, pointing to the worthy soul issuing from his mouth (Psalm 85), Albani Psalter (page 243), St Albans, England, 12th century, illumination on vellum. Hildesheim Cathedral, Germany, https://www.albani-psalter.de/stalbanspsalter/english/commentary/page243.shtml.

The liturgy also connected the act of kissing the gospel book to receiving the Eucharist through the pax, a liturgical object designed to capture and disseminate the priest’s kiss of peace (Fig. 5).[21] By the late medieval period, Christians commonly employed the pax as a proxy for the body of Christ, and congregants spiritually received the pax as they would the host.[22] Oral rituals tied the Eucharist to the pax—the priest kissed the pax and passed it to the congregants, who then kissed it to receive the kiss.[23] The gesture mirrored the priest’s kiss of the gospel book at the ceremony’s opening.[24] Though paxes were composed in a wide array of materials and typically took the form of a plaque, paxes often bore images of the Crucifixion. Both the pax’s iconography and the gestures surrounding its liturgical use thus linked the pax to the gospel book and the gospel book, by extension, to the host.

Fig. 5. Pax with Crucifixion, Germany or France, 15th century, ivory. Catharijneconvent, Utrecht, Netherlands, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/WLANL_-_Pachango_-_Catharijneconvent_-_Paxtafel_met_kruisiging_%281%29.jpg/848px-WLANL_-_Pachango_-_Catharijneconvent_-_Paxtafel_met_kruisiging_%281%29.jpg?20090901101310.

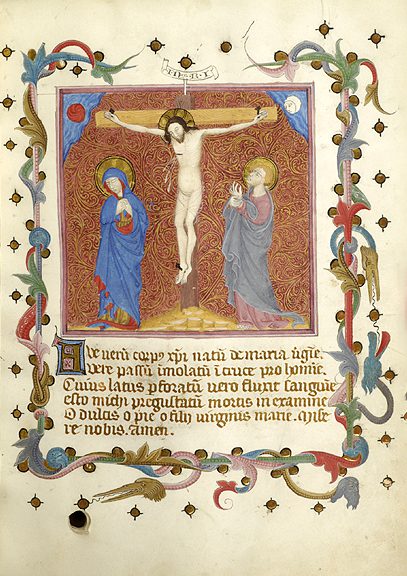

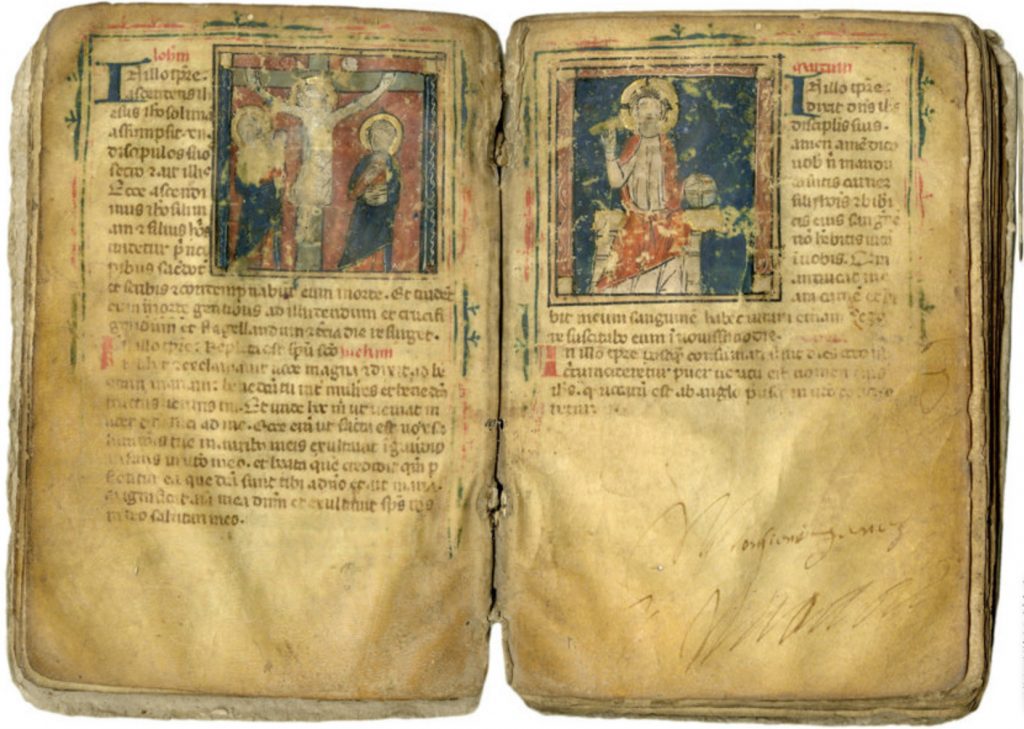

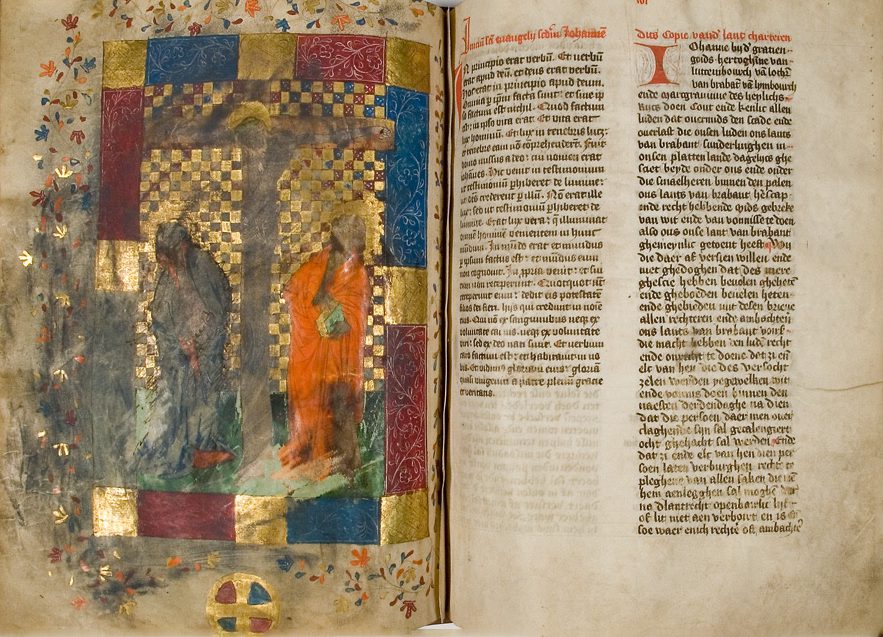

Beyond the gospel book’s associations with the Eucharist, many medieval Christians believed that the gospel book had a talismanic power as a symbol of Christ and represented the desired unity of the Church and the lord’s human element.[25] Medieval organizations sometimes repurposed secular books for oath rituals by inserting Gospel verses and images of the Crucifixion when gospel books were not available, suggesting that oath books’ efficacy depended on gospel books’ talismanic quality.[26] This was also the case for manuscripts compiled specifically for secular oath swearing rituals such as Morgan MS M.300 (Fig. 6), a fifteenth-century oath book for coiners and minters in Avignon, and TM 652 (in a private collection), a customary and oath book for the town of Lézat-sur-Lèze from the turn of the fourteenth century (Fig. 7).[27] The latter manuscript’s Crucifixion miniature and accompanying Gospel verses show visible stains and signs of erosion from repeated use, which may have resulted from the later custom of vassals kissing both their lord and the Gospels in fealty oath rituals.[28] In this manuscript’s case, evidence of oath swearers’ tactile fixation with the Crucifixion miniature and its feudal context speak to the wider implications of kissing oath books in the late Middle Ages.[29]

Fig. 6. Crucifixion miniature, Oath of office for coiners and minters of Avignon and register of officials (Fol. 3r), Avignon, France, c. 1411, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.300, http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/2/112377.

Fig. 7. Crucifixion and God the Father miniatures, Customary and Oath Book for the town of Lézat-sur-Lèze, with accessory texts; Arbitration Award (Fols. 9v–10r), Lézat (Ariège), France, c. 1299, with additions 1327, illumination on vellum. Les Enluminures, TM 652 (private collection), https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/customary-oath-book-60907.

Kissing or rubbing an oath book thus simultaneously venerated God and confirmed servitude, while the talismanic nature of the Gospels imbued this touch with transformative power over the bodies of those who swore on them. Due, in part, to the theological focus on the Eucharist having informed the practice of swearing on oath books, the liturgical connotations of oath swearing gestures were instrumental to these books’ power.

Crucifixion

The Arenberg Gospels’ visual program makes visceral the liturgical linkage between the Gospels and the sacramental body of Christ. Eucharistic theology shaped the manuscript’s original iconography, which emphasizes Christ’s real, physical death in both the scheme for salvation and the sacrament of the Eucharist.[30] In the Crucifixion miniature, the dead Christ figure’s body betrays the agony of his death on the cross (Fig. 8). Christ’s heavy brows cast shadows over the creases under his closed eyes, and his head slumps horizontally to the left, countering the dramatic arc of his broken body. As the figure collapses under his own weight, the sharp curve in his lower spine unnaturally rends his corpse in opposite directions. His hips and stomach turn against his leftward leaning upper torso to face the right, only to be countered again by the sweeping curve of his legs, which stand in an exaggerated contrapposto and bend inward at the knees. Tiny droplets of blood stream from the dark puncture wounds in the figure’s hands and feet, and his feet bleed directly into a Eucharistic chalice sitting at the base of the cross. The Christ figure’s deep purple outline and uncolored corpse stress the raw humanity of Christ’s body—his flesh becomes the flesh of the parchment.[31] His blood becomes the bedrock of the architectural frame. Mary and John, who carries a golden book, flank Christ in the lower register of the image, and two angels flank him in the upper register. The surrounding figures’ transcendent expressions highlight the palpable emotionality of the Christ figure. John and Mary do not mourn but bear witness, with their colorful clothing echoing the angels’ celestial forms.[32] The hand of God emerges from the top of the cross and strains towards Christ, while Christ’s slumped head directs the eye down his twisted figure to the bloody droplets that spurt from his wounds and collect in the Eucharistic chalice below his feet.

Fig. 8. Crucifixion (detail), Arenberg Gospels (Fol. 9v), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0039-0040.jpg.

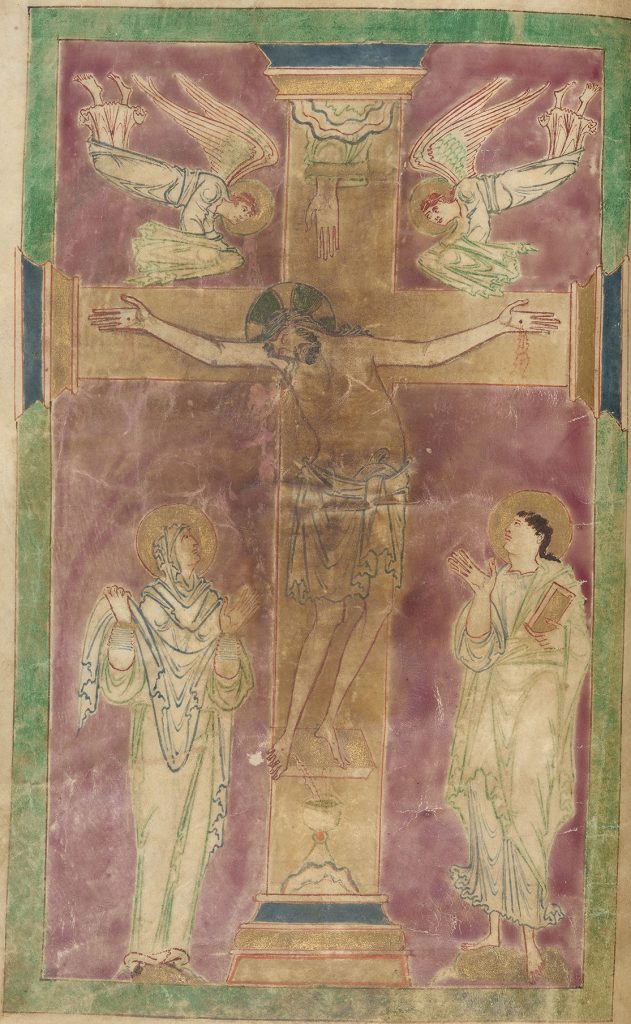

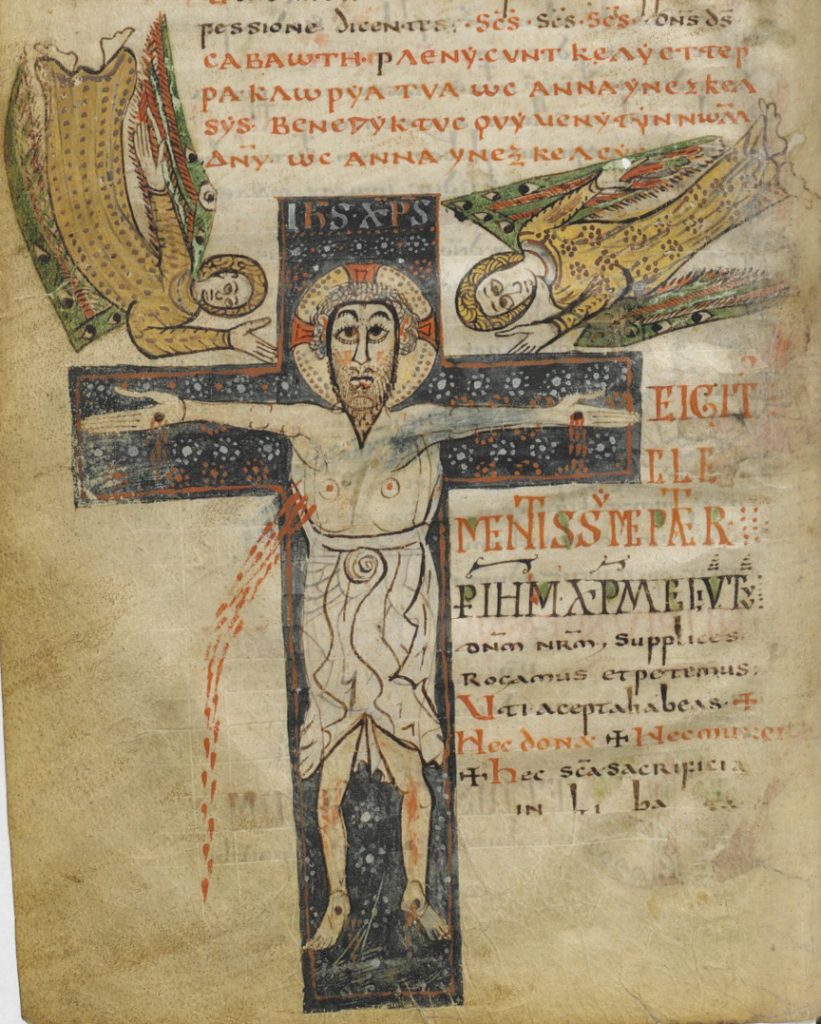

The degree of the dead Christ figure’s suffering is unparalleled in earlier or contemporary Crucifixion scenes. While agonized portrayals of the crucified Christ appear in English poems like “The Dream of the Rood” as early as the eighth century, these poems also depict Christ in a triumphal light, and early English Crucifixion images tend to share in this more glorious conception of Christ on the cross.[33] Though the Christ figure’s agony in the Arenberg Gospels pales in comparison to the agony in, for example, Matthias Grünewald’s violent Crucifixion paintings of the sixteenth century, it far surpasses the pain shown in even the bloodiest Carolingian or early English Crucifixion scenes. For instance, in perhaps one of the earliest illuminated Crucifixions, the bleeding Christ figure in the Te igitur initial of the Gellone Sacramentary stands in an upright posture with a neutral expression (Fig. 9).[34] Dead Christ figures in contemporaneous English Crucifixions, like that in the Sherborne Pontifical (Fig. 10), often bear closed eyes and a slightly slumped head but otherwise maintain the straight, frontal posture typical of triumphal Christ figures.[35] Though the Crucifixion miniatures in the Sherborne Pontifical and the Arenberg Gospels employ closely related motifs, the Arenberg artist’s pathetic treatment of the Christ figure radically departs from that of his contemporary.[36] The artist of the Arenberg Gospels instead went to great lengths to stress Christ’s agony by exaggerating the figure’s bodily contortion. The dramatic break in Christ’s spine, the sideways tilt of his head, and the elaborate curve of his body are all suggestive of Christ’s suffering in death.

Fig. 9. Te igitur Crucifixion initial, Gellone Sacramentary (Fol. 143v), France, c. 790, illumination on vellum. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France Latin 12048, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b60000317/f10.item.

Fig. 10. Crucifixion scene, Sherborne Pontifical (Fol. 4v), Dorset, England, c. 992–995, ink on vellum. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France Latin 943, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6001165p/f14.item.

The Crucifixion miniature integrates the historical Christ figure’s agony into a thematically sacramental iconographic program. According to Jane E. Rosenthal, this iconography draws on the ninth-century theologian Paschasius Radbertus’s commentary on transubstantiation.[37] Radbertus believed that the utterances spoken in consecration became the body and blood of the historical Christ and that the presence of Christ’s historical body in the sacrament allowed one to spiritually unite with him by physically fusing with his body.[38] The chalice on the mound identifies the sacramental blood as that which flowed on Golgotha, and Christ’s dead, human body on a liturgical form of the cross identifies the sacramental body with Christ’s historical one.[39]

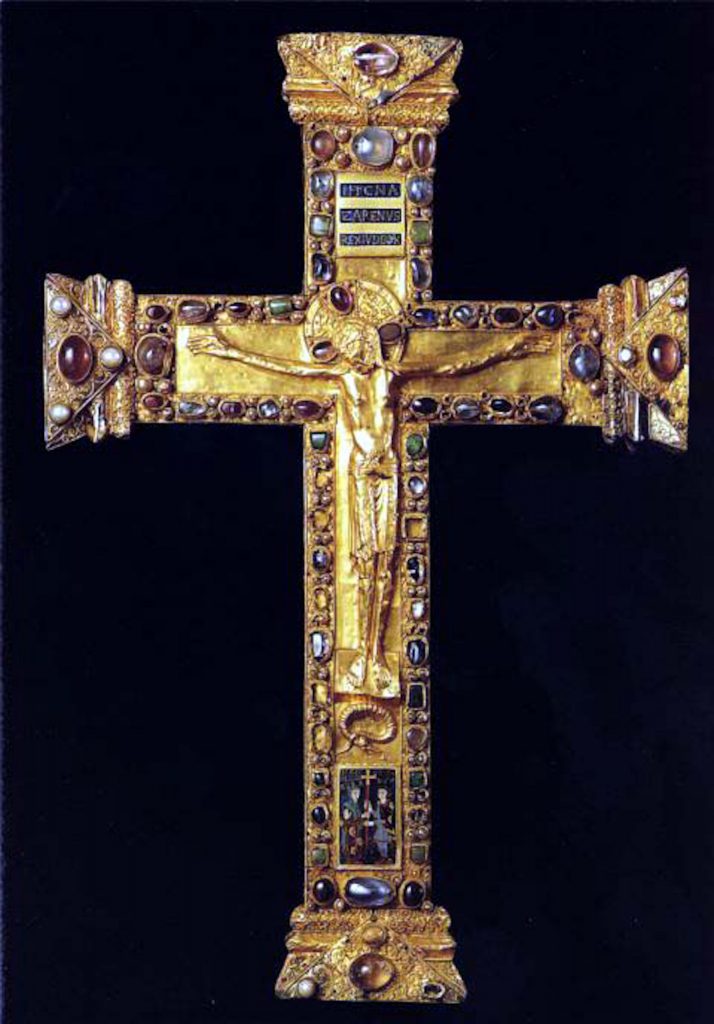

Specifically, the artist modeled the cross in the miniature on processional forms of metal crosses that, along with a gospel book, would have been carried to the altar to open the Mass and remained there as a reminder of Christ’s sacrifice. Much like the cross in the Arenberg Gospels, surviving liturgical crosses such as the Lothair Cross (Fig. 11) and the Otto and Mathilda Cross (Fig. 12) both feature banded architectural terminals and appear monumental in scale compared to their central Christ figures.[40] As argued by Beatrice Kitzinger, these liturgical crosses’ potential to play an active ritual role essential to the immanence of the sacrament relies on the marriage between the form of the cross and the physical object, while, in illuminated crosses, this immanence applies to both the manuscript and the cross itself.[41] For example, through its textual integration into first canon of the Mass and its depiction of a liturgical form of handheld cross, the Te igitur initial establishes the manuscript as a space of ritual action parallel to the surrounding rite, extending the body of the crucified to the Eucharist outside the page.[42] Similarly, the Arenberg Gospels utilizes a liturgical cross and motifs such as angels flying in at the moment of consecration to embed the cross, the crucified, and the manuscript itself in the physical space of the sacrament.

Fig. 11. Lothair Cross (back), Cologne, Germany, c. 1000, gold, silver, gems, and cloissoné enamel on wooden core. Aachen, Aachen Cathedral Treasury, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Germania_occidentale,_croce_detta_di_lotario,_1000_ca,_con_ base_tardogotica_(XV_secolo),_retro_01.jpg. The Christ figure’s posture on the Lothair Cross also bears a close resemblance to that of the Arenberg Gospels’ Christ figure, which further suggests that the Arenberg artist worked from a similar model.

Fig. 12. Otto and Mathilda Cross (front), Essen, Germany, c. 973–982, gold, gems, and cloissoné enamel on wooden core. Essen, Essen Cathedral Treasury. Photo: Martin Engelbrecht, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Otto_Mathilden_Kreuz.jpg.

The imagery surrounding the cross further ties the Arenberg Gospels’ Crucifixion scene to the site of consecration. In addition to the purple ink of the background representing Christ’s blood, the color was also associated with Heaven in the medieval period.[43] The same color also appears in the background of all four Evangelist portraits, in each case surrounding either the Evangelist or the Evangelist symbol, thus uniting the saints under Heaven. Meanwhile, by placing Christ on a processional form of the cross atop a purple backdrop, both of which create an architectonic container around the figures, the Crucifixion miniature’s background recalls the porphyry used to protect gatherings of relics in series of portable altars in the central Middle Ages.[44] Therefore, the backdrop links Christ’s blood to his sacred union with the Court of Heaven, while the cross represents the historical procession gathered at the liturgical site of his salvific death.[45] Both the cross and altar dominate the architectural frame, staging the Passion at the heart of the Church and its re-presentation in the Mass as Christendom’s unifying force.[46] Christ both rests atop and becomes one with the altar and the relics of the martyrs, equating the body of Christ with the Eucharist and the book while anticipating the book’s liturgical use.

Fig. 13a. Crucifixion and canon tables, Arenberg Gospels (Fols. 9v–10r), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0039-0040.jpg.

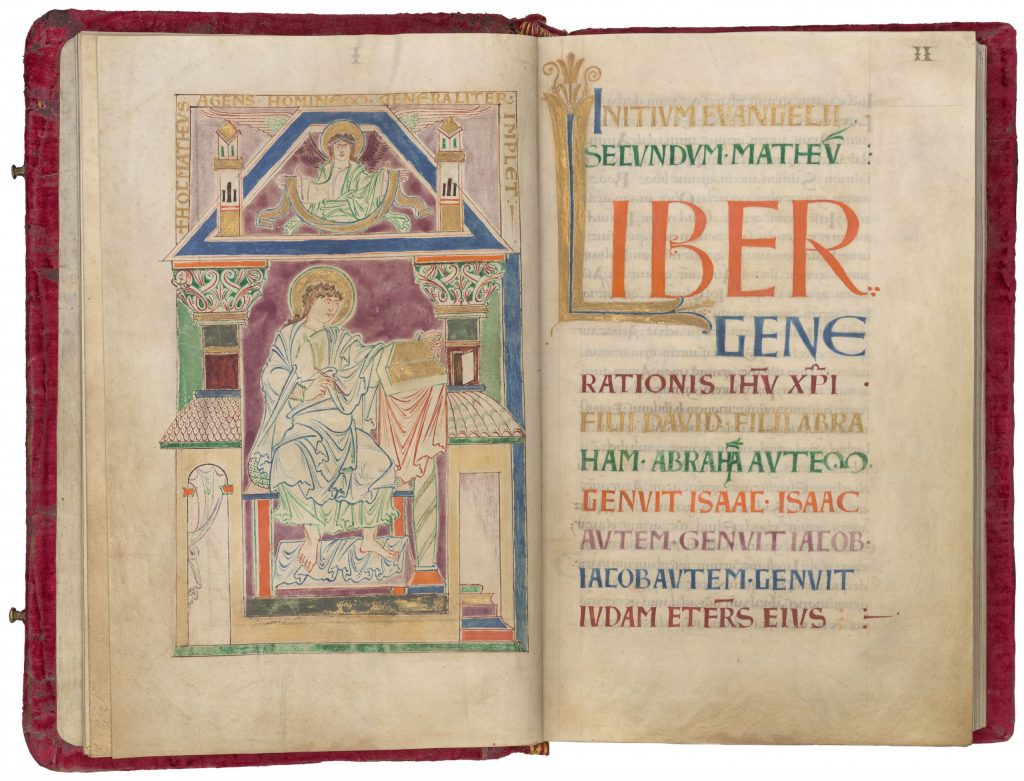

Fig. 13b. Evangelist portrait of Matthew and decorative incipit page, Arenberg Gospels (Fols. 17v–18r), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0055-0056.jpg.

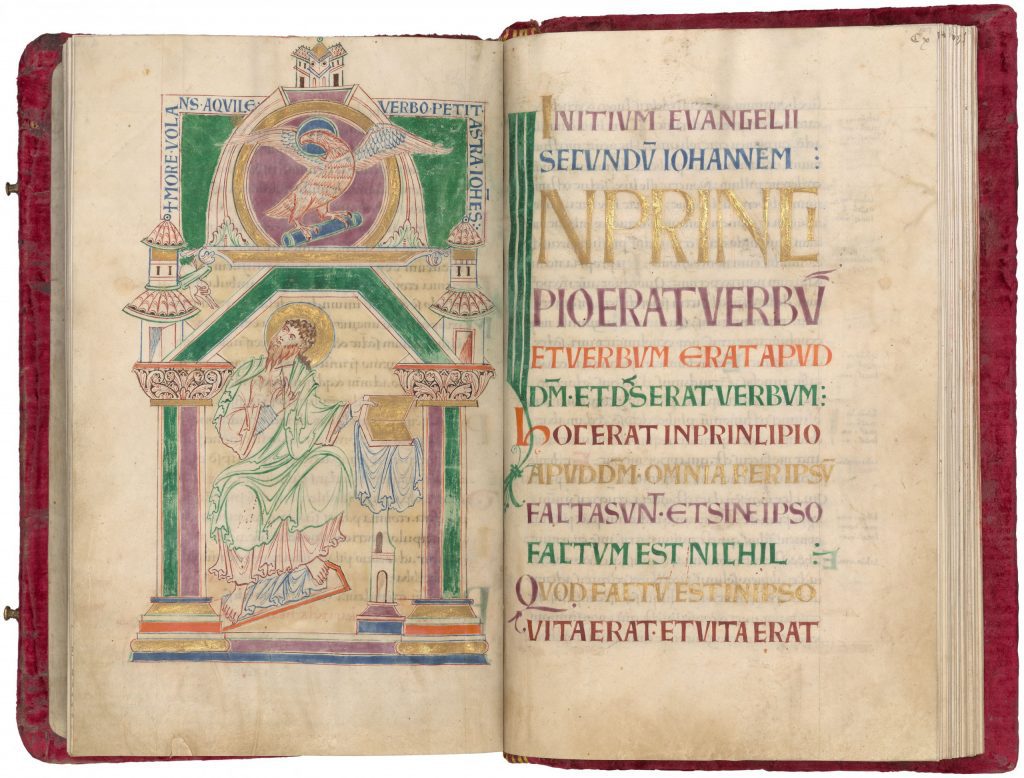

Additionally, the Evangelist portraits’ placement on the verso sides of the leaves facing their respective Gospels echoes the Crucifixion miniature’s position on the verso side of the opening leaf opposite the canon tables (Figs. 13a–b).[47] While Evangelists were often shown opposite their Gospels in later early English gospel books, the Arenberg artist’s unusual choice to separate the Crucifixion from the chronological narrative of Christ’s life in the canon tables opposite it frames the Crucifixion in a similar position as the Evangelists with respect to their Gospels. That is, it frames Christ’s death as the origin of the canon tables’ narrative cycle, which combines the events of the Gospels with dogmatic themes derived from Aelfric’s sermons.[48] This arrangement links Christ’s liturgical body to the bodies of those who preach, both in the form of the Evangelists and in the Mass. It also connects Christ to the act of writing and preparing a gospel book as well as to the gospel book itself. All four Evangelists are shown writing the Gospels, and their books’ open pages shine with the same gold of the closed book in the Crucifixion miniature.[49] As Kitzinger argues, writing Evangelist portraits build continuity between the people represented in the Gospels and those who created the genre of the gospel book in the past or present, while, according to Richard Gameson, John carrying a book in early English Crucifixion miniatures underlines the status of his eyewitness account.[50] The writing Evangelists with their Gospels thus mirror John bearing witness to Christ through his written account in the Crucifixion miniature, while John’s Evangelist portrait also features the lord (Fig. 14). The hand of God appears outside the architectural frame in John’s portrait, emphasizing God’s heavenly nature by separating him from John’s earthly sphere. Though God resides in Heaven, John’s contact with the book allows him to call upon divinity.

Fig. 14. Evangelist portrait of John and decorative incipit page, Arenberg Gospels (Fols. 126v–127r), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, illumination on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0273-0274.jpg.

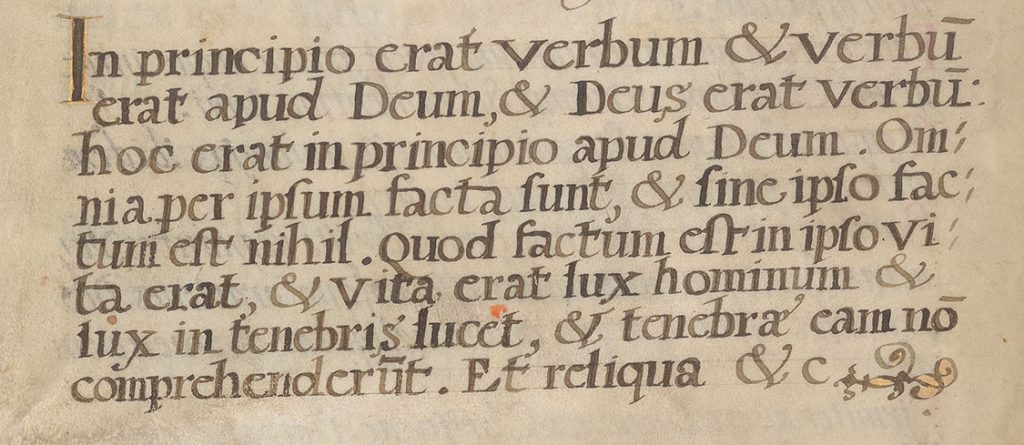

Moreover, the book’s arrangement of the Crucifixion miniature before both the canon tables and the Gospels frames Christ’s sacrifice as prefiguring the Mass and all its meaning, while, as Rosenthal argues, the artist goes further than Radbertus in implying that the Mass literally renewed the agonies of the Passion.[51] Thus, the Crucifixion miniature’s placement unifies Christ’s liturgical and historical bodies through the Gospels, while the medium of the book unites Christ with the body of the speaker or scribe. Furthermore, the Arenberg Gospels’ iconographic program establishes Christ’s sacrifice and its liturgical re-materialization in the Eucharist, the gospel book, and the Word as intrinsic to these relationships.

Advent in the Flesh

Just as Christ’s sacrifice prefigures the significance of the Arenberg Gospels’ imagery and text, the manuscript’s production symbolically mirrored the Passion.[52] As argued by Marlene Villalobos Hennessy, medieval readers imagined that books could become the incarnate flesh of Christ, the Word made flesh.[53] Hennessey traces this set of associations to the Carolingian period, with Rabanus Maurus’s ninth-century treatise on the Passion metaphorically referring to Christ’s blood as ink.[54] Parchment stretched to dry on wooden frames resembled Christ on the cross.[55] Parchmenters rubbed and beat Christ’s “crucified” body with pumice and chalk, recalling his flagellation.[56] Pricking and transcribing punctuation invested parchment with the crown of thorns, and it bled red or purple ink symbolizing his blood.[57] The unity of the Gospel narrative with the process of making underlies this symbolism, and the Arenberg Gospels’ production illuminates how these narratives converge.

Manuscripts are living matter, continuously transforming with the materials, surroundings, and people with which they interact during their production.[58] Parchmenters, scribes, and artists attune themselves to the fluxes of the parchment and ink, working with the current of materials in their further transformation.[59] The artisans, in effect, saw Christ’s advent in the flesh as they prepared the Arenberg Gospels. They felt calfskin transubstantiate into his flesh through contact with their own.[60] The activity within the gospel book’s materials as well as the bodies who co-produced and responded to this activity generated this symbolism. Thus, the Arenberg Gospels’ material transformation during production, as both a product and a producer of touch, re-materialized Christ in the book and imbued it with Christ’s power.[61]

In fact, as Rosenthal argues, the artist’s unique pictorial innovations appear to be such a personal statement of belief that he likely decorated the manuscript for his own use or for someone in his immediate circle, intimately linking him to the life of the book.[62] For example, the artist recombined motifs derived from multiple Insular, Carolingian, and late antique sources in a highly improvisational manner to convey the themes of Aelfric’s sermons throughout the canon tables.[63] As Rosenthal also observed, the artist’s depiction of a suffering Christ figure brings a layer of meaning to the Radbertusian iconography of the Crucifixion miniature that does not appear in Radbertus’s writings.[64] This suggests that Christ’s portrayal may have been the artist’s invention based on his interpretation of the author’s Eucharistic theology. Moreover, neumes and marginal rubrics marking lections for certain feasts appear in the earlier part of the book and exhibit similar forms and coloring to the central text, which indicates that the Arenberg Gospels may have been originally intended to serve as a lectionary in the divine service at around the time it was made.[65] Bearing in mind the artist’s specific theological knowledge, it is possible that he designed the book for his own use as a preacher in the service.[66] As such, the manuscript may have borne both Christ’s talismanic power and a personal connection to its venerable scribe and the liturgical context of the Passion.[67]

God’s Gift

Given the longstanding ties between the network of churches in Cologne and Christ Church, the manuscript likely entered Cologne as an ecclesiastical gift.[68] The gap in marks of use between the artist’s marginal rubrics and the early twelfth-century copy of Pope Gregory VII’s decree canonizing Archbishop Heribert of Cologne on fol. 14 would allow that the book may have entered Cologne as early as the early eleventh century during St. Heribert’s tenure.[69] Though it is impossible to say if an ecclesiastic in Canterbury indeed gifted the manuscript to St. Heribert or one of his colleagues, the fraternal community that copied the papal bull may have done so to acknowledge Heribert’s connection to the manuscript, whether real or invented.[70]

This suggests that the Benedictine abbey at Deutz may have recorded the bull, which St. Heribert founded in 1003, and which elevated him as their main patron in the twelfth century.[71] The abbey at Deutz may have gifted the Arenberg Gospels to the church of St. Severin later in the twelfth century to promote St. Heribert’s cult, though the lack of documentary or physical evidence—such as inscriptions—from the later twelfth through thirteenth centuries may indicate, instead, that the manuscript did not reach St. Severin until the fourteenth century.[72]

No matter the exact circumstances, medieval gifting mores may have heightened the sense that the Arenberg Gospels promised its recipients divine gifts while, at the same time, morally indebting them to the book’s donors. As the Arenberg Gospels was a luxurious gospel book with a possible connection to a local saint and was likely a gift between ecclesiastical houses, the obligation of the medieval offering pro anima may have impacted its reception. Gifts pro anima, or gifts for the salvation of the soul, were offerings donors dedicated to saints and gave to religious communities in hopes that they would be spiritually rewarded for their generosity.[73] These offerings set in motion mechanisms designed to ultimately guarantee the donor a spot in heaven by negotiating sacred bonds between donors, the religious communities who received the gift, and the saints to whom the gift was dedicated.[74] However, the bonds gift giving affirmed had to be reaffirmed by a counter gift, with disparities in gift exchanges often demarcating the direction and degree of subordination between two parties.[75] Asymmetrical gifts between monastic communities competing for patronage made this particularly clear.[76] The Arenberg Gospels’ reception at St. Severin may have thus underlined the receiving church’s spiritual debt to its neighboring churches and the Church. If this was the case, this dynamic would have likely factored into the Arenberg Gospels’ use in ecclesiastical oaths of office.

Communion

In its use within oath rituals, the Arenberg Gospels carried the combined meaning of its past lives. The overrepresentation of fourteenth-century oaths in the formulary and the erosion of oaths for more common roles in the opening quire indicates that church officials likely reused earlier oaths for the same positions, linking later oath swearers to the tradition of their office and to that of their church and its surrounding fraternal network.[77] A number of shortened versions of the formulae for existing oaths may also attest to groups of officials being sworn in during the same ceremony, furthering this sense of community.[78] Moreover, the oath records’ placement suggests continuity between the manuscript’s history and the words of the oaths. For example, church officials recorded two oaths under the papal bull of St. Heribert’s canonization and before the opening to the Gospels, connecting the oath ritual to the book’s potential ties to a local saint and sacramental use in England.[79]

The oath formulae also equate God and the Gospels, constituting the lord in a way that recalled the words spoken in consecration, which were believed to miraculously transform bread and wine into Christ by verbally identifying them as his body and blood.[80] Each oath begins with church officials stating their name in connection with their title (“Ego. Nomen. Decanus,” “Ego. Nomen. Canonicus,” etc.), and each oath concludes with “Sic me deus adiuuet et hec sancta dei Evangelia” (So help me God and these sacred Gospels).[81] The pronoun “hec” specifically refers to that just mentioned, thus equating God and the Gospels through the medium of the book.[82] Having officials verbally identify themselves without relying on the written word also served both a practical and a symbolic purpose. Anonymizing the written oaths allowed for their reuse. At the same time, it let officials reflect on their promises and embody them through their utterances, while defining themselves in terms of their relationship with the Church connected the help of God and the Gospels to the sacramental context of the oath ritual, where the deacon equated God and the Gospels before reading the Gospel lesson.[83] As ecclesiastical oaths are themselves covenants with Christ and his mystical body, the gospel book essentially becomes equivalent to the “host,” physically representing the promise of the oath and recalling Christ’s sacrificial covenant with humanity.

Though many medieval oath books include nearly identical oath formulae, the Arenberg Gospels’ iconography and social life furthered this Eucharistic analogy in oath rituals at St. Severin. The manuscript may have entered the church as a gift, much like the meaning of the word host. “Eucharist” comes from the Greek root eukharistía (thanksgiving). The Latin eucharistia refers to Christ’s gift, a thanksgiving which terminates in the sacrificial self-oblation of Christ.[84] At the same time, the manuscript’s possible use as a lectionary in the Mass at Christ Church linked the book’s potential saintly contacts to the liturgical context of Christ’s sacrificial gift. The Crucifixion miniature made these connections palpable by manifesting Christ’s sacramental body in both the illumination and the parchment itself. Outside of recalling the general symbolism of gospel books, few oath books from this period made such explicit iconographic references to the liturgical context of Christ’s sacrifice. For example, while the whitish liquid that spurts from Christ’s wound in Morgan MS M.300 may reference water mixed with blood as indicative of the sacrament (see Fig. 6), the scene otherwise lacks liturgical imagery, featuring instead a historical type of cross surrounded by celestial motifs. Similarly, the severely abraded Crucifixion miniature in the Rood Privilegeboek, an oath book and book of civic statutes for the city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch from c. 1430, displays a historical cross and a decorative background, making no allusions to the sacrament (Fig. 15).[85] Among surviving examples of Crucifixion scenes and other images used for oath swearing, the Arenberg Gospels’ Crucifixion miniature uniquely created a reminder of the gospel book’s Eucharistic symbolism in the oath ritual. The words of the oaths, thus, tied the kiss of the Crucifixion miniature to both the priest’s kiss of the gospel book, which the Arenberg Gospels may have received in England, and to the pax as proxies for the body of Christ. By kissing the Crucifixion miniature, church officials received Communion, and Communion meant becoming as Christ.

Fig. 15. Crucifixion miniature, Gospel of John, and Joyous Entry, Rood Privilegeboek (Fols. 55v–56r), c. 1430, illumination and ink on vellum. ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Netherlands, Erfgoed ‘s-Hertogenbosch oud archief inv. nr A 525, https://hdl.handle.net/21.12121/14858590.

Specifically, the kiss let officiants form a spiritual and embodied union with the lord. Kissing the gospel book in the liturgy allowed the speaker to receive Christ into his soul during the Gospel reading, much like the kiss of peace joined the souls of the congregation together to form Christ’s mystical body.[86] Both kissing the gospel book and consuming the host enacted a spiritual fusion with divinity and promoted salvation from sin. Meanwhile, people often conceived of reading and seeing as physical acts of mimesis heightened by touch.[87] By feeling Gospel verses, officials internalized Christ, the Word, while internalizing him in a way that resembled both the pax and the priest’s kiss of the Gospels tied mimetic reading to transformation into a Christ-like mode of being.

Church officials also inserted the opening lines of John on fol. 8v (Fig. 16), which were often used as textual talismans, suggesting that officials called upon the Arenberg Gospels’ talismanic powers in their rituals.[88] Notably, church officials always positioned their oaths to precede the Word made flesh.[89] The first line of John reads, “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”[90] The scribe in the opening quire also added “Et reliqua” (And the rest) after the fifth line, citing not only the rest of the Gospels but also John 1:14 specifically: “And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us.”[91] This line refers to Christ’s advent in the flesh, just as he was manifested in the flesh in the Crucifixion miniature as well as in the Gospels themselves. The oaths before the verses from John in the opening quire precede the Crucifixion miniature, the oaths on fols. 124–126 come before the opening of the Gospel of John, and the oaths on fol. 14r precede all four Gospels.[92] Additionally, the opening lines of John in the Arenberg Gospels’ first quire show no signs of erosion, unlike the visibly damaged Crucifixion miniature on the next folio, which implies that only the latter received the devotional touch typical of talismans. Thus, the oaths’ arrangement before the opening lines of John and the Crucifixion miniature prefigured officials’ embodiment of Christ’s virtues in their new roles while increasing the efficacy of calling on God’s protection to help them live virtuously.

Fig. 16. John 1:1-5 (detail), Arenberg Gospels (Fol. 8v), Canterbury, c. 990–1010, 16th-century inscriptions, ink on vellum. New York, Morgan MS M.869, https://www.themorgan.org/sites/default/files/facsimile/download/159161v_0037-0038.jpg.

Importantly, kissing the Crucifixion miniature animated Christ’s body with the bodies of those who swore on the manuscript, thereby enhancing Christ’s presence in the oath ritual. According to a DNA study by Matthew J. Collins and his team on the York Gospels, a roughly contemporary oath book in use at York Minster, the manuscript contained a high percentage of human DNA compared to the control group of legal manuscripts due to centuries of intense rubbing and kissing.[93] The visible erosion of the Crucifixion miniature in the Arenberg Gospels suggests that the book would probably return similar results, as the manuscript’s use as an ecclesiastical oath book spanned several centuries during roughly the same period. Additionally, Kathryn M. Rudy’s densitometer analysis of medieval prayer books found that readers’ devotional touch both added material to and subtracted material from the manuscripts in her study.[94] The greater the wear on an image, the more pronounced these layers of addition and subtraction became.[95] Additionally, church officials’ usage patterns in the Arenberg Gospels suggests that officials were aware that they exchanged matter with the Christ figure and that, by leaving behind a part of themselves, they damaged the image of their lord. One church official even tried to salvage Christ’s image by scraping some of the thick layer of crud off the bottom of the miniature but instead left a patch of dirt in the part of the gutter his tool could not access.[96] Thus, each time church officials kissed Christ’s image, they gave themselves to Christ and received Christ and the book’s past contacts into themselves. Christ’s figure fused with their bodies, recommencing his advent in the flesh. At the same time, church officials’ touch degraded Christ, renewing his sacrifice with every oath. The oath ritual therefore reproduced the Arenberg Gospels’ iconography of transubstantiation in the Crucifixion miniature’s materiality by rehumanizing Christ’s suffering and enacting officials’ bodily fusions with divine corporeality.[97] Consequently, the book shaped officials’ understanding of their oaths by injecting the soteriology of the Eucharist into the oath ritual.

By letting church officials connect with divinity, the Church implored its officials to embody Christ’s sacrificial virtues in their duties. Communion meant becoming as Christ, who saved humanity through his own physical, human suffering.[98] Due to the late medieval tendency to interpret changes in matter and, particularly, changes in Christ’s physicality as internal to one’s personal devotional life, church officials may have interpreted the Crucifixion miniature’s erosion as a message of internal sacrifice.[99] When they kissed the Crucifixion miniature, they “consumed” and thereby embodied Christ’s pain. They had to suffer in service of the Church, and suffering meant redemption.[100]

The church of St. Severin integrated the Arenberg Gospels’ Eucharistic symbolism into an employment contract typical of Germanic fealty oaths.[101] Church officials pledged loyalty and obedience to the Church in exchange for lodging and subsistence.[102] For example, the canons promised to observe the binding customs and laws of the church to receive goods or tithes.[103] The oaths also reinforced the church’s internal hierarchy. For instance, the oath of the canons on fol. 14r begins with a promise to be obedient and faithful to one’s superiors, including the lord, the Archpriest of Cologne, and the dean and chapter of St. Severin.[104] Similarly, the oath of the vicars on fol. 4r reiterates vicars’ statuses at the bottom of the church’s pecking order, with vicars swearing allegiance to the church of St. Severin, their canons, and their deacons.[105] Originally, the canons personally employed these low-level clerics to perform some of their less crucial tasks, but the vicars’ roles soon became official, and the shortened form of their oath implies that many new vicars were sworn in in larger batches.[106] In fact, the oath of the vicars on fol. 4r became so badly abraded due to the number of vicars swearing on the manuscript that it had to be reinscribed, suggesting that lowest ranking church officials made up the largest cohort within the church in an organizational structure similar to the hierarchy of a feudal estate.[107] Therefore, church officials’ oaths followed the format of Germanic fealty oaths, wherein vassals promised to serve their lords as subordinates, and lords guaranteed them protection and maintenance in return.[108] By kissing the Gospels, church officials pledged fealty to the Church, confining them to a lord-vassal relationship in which they relinquished comforts and autonomy to serve the lord.

In addition to communicating obligations similar to fealty oaths, however, the oath ritual’s form also paralleled the preparation to receive Communion, with the oath book acting as both a proxy for Christ and a confessional. The oath book’s presence raised the specter of the oath swearer’s possible guilt by suggesting that church officials might lie if they only confirmed their promises verbally without invoking divinity through the book. Indeed, simply having an oath book had the potential to put the oath swearer in an uncertain state of quasi-culpability and moral inferiority in relation to the other parties to the contract.[109] This dynamic unfolded in Jewish oaths of the same period, and a comparison is revelatory.[110]

As previously discussed, medieval Jewish communities swore on Torah scrolls, which adhered to strict halakhic rules in their production and preservation, such as using specially prepared types of parchment.[111] However, Christians produced the rolls for Jewry oaths, which were special oaths that Jewish citizens had to swear to submit evidence in civil lawsuits.[112] These rolls adhered to none of the same honorific principles and thus lacked the sacredness of the Torah scroll, yet Jewish witnesses were required to confirm the rolls’ genuineness in court, making Jewry oaths’ veracity dependent on prescribed self-maledictions and procedural humiliation.[113] In this case, Christians used oath books to publicly shame the accused for their presumed untrustworthiness. Of course, the church of St. Severin did not subject its officials to such an elaborate humiliation ritual but rather let officials taste the glory they would receive in Heaven if they performed their jobs adequately. However, by implying that church officials received Communion when they kissed the oath book, the church made Christ’s blessing contingent upon officials’ public confession of potential guilt.

Church officials also displayed subservience and apologized for their sins by lowering themselves to swear on the Gospels. Ecclesiastics often bowed or kneeled before the presider over the oath ceremony, mirroring vassals’ posture when they paid homage to their lords.[114] Vassals kneeling or bowing before their lords in fealty oath rituals communicated their status as underlings, and vassals only rose to engage in the kiss of mutual fidelity with their lords’ permission once this hierarchy had been established. Indeed, genuflection could be seen as an act of humiliation between lords or nobles of a similar rank, with, for example, rulers such as Conrad III refusing to kneel before Byzantine Emperor Manuel I to preserve his country’s honor.[115] Additionally, genuflection often represented penitence and sorrow for one’s sins in the Mass.[116] The priest bowed or kneeled while reciting the prayers at the foot of the altar, prayers which recalled and asked for freedom from one’s sins.[117] For example, the Confiteor addressed the saints with the plea “mea culpa (III vic.) peccavi / per superbiam in multa mea mala iniqua et pessima cogitatione,” while the Aufer a nobis that followed similarly recounted sins for which the speaker sought absolution.[118] The prayer that accompanied the altar kiss, Oramus te, Domine, combined the martyrs’ memory with a longing for forgiveness from sin.[119] Much like a vassal, the priest displayed humility before a higher authority when he lowered himself to kiss or kneel at the altar. Thus, in the oath ritual, genuflection symbolized church officials’ apology for their sins, with their subservience paving the road to forgiveness.

Furthermore, church officials erased the oaths on the recto sides of the Crucifixion miniature and John’s Evangelist portrait, thus removing their oath records before both miniatures that depict the lord (see Fig. 3). Officials likely inscribed their oaths as close to these talismanic images and verses as possible to give their oaths more power, whereas the later censorship of these records may reflect a sense of unease or unworthiness around claiming such proximity to the divine.[120] While it is unknown if the same official who scraped dirt from the Crucifixion miniature was responsible for these erasures, the act could nonetheless signify a similar attempt to salvage the depicted divinity from the smudge of human fault. This is notable because all Germanic oaths represented a bedingte Selbstverfluchung (hypothetical self-denunciation), with penal clauses in earlier Germanic oaths cursing the oath swearer to this effect if they breached the contract.[121] By removing their oath records before these specific miniatures, church officials may have performed a sort of penance by denouncing themselves of their potential iniquities before appearing before God.

In this sense, becoming as Christ was also an un-becoming. While the Arenberg Gospels’ scribe and artist may have produced the manuscript to celebrate his personal faith, swearing oaths of office on the manuscript paradoxically distanced officials from their own humanity when they performed their duties. Because becoming Christ-like meant suffering in service, church officials could not savor the material benefits their offices afforded them. Nor could they enjoy the fruits of their labor. When they worked, they worked as Christ, dissociating them from their own actions and, consequently, from what their actions produced. The self-sacrificing mindset that came with embodying Christ increased officials’ desire to work beyond their roles’ requirements and increased the power of their prayer, thereby earning the church more benefactors and the Church above it greater control.[122] Ultimately, suffering created value. By imploring church officials to become self-sacrificing servants and reminding them that they would achieve redemption or invoke divine retribution depending on their success, the Arenberg Gospels transformed oath swearers into ideal vassals.

Conclusion

The Arenberg Gospels’ history of use generated meaning in the oath ritual by re-materializing Christ’s human suffering with every touch. Swearing on the Arenberg Gospels compelled church officials to sacrifice to receive spiritual benefits in a rite that echoed feudal contracts. However, the oath ritual combined the significance of kissing the gospel book and receiving the host; as in Radbertus’s Eucharistic theology, it signified becoming as Christ through Communion. Because officials implicitly asked God for redemption and forgiveness in the ritual, the church insinuated that church officials would receive salvation by embodying Christ. Specifically, church officials had to suffer for the Church to be redeemed in Heaven. When church officials internalized the message of Christ’s sacrifice, they denounced their ownership over their material realities to pursue immaterial gains in the afterlife.

This sacrificial dynamic likely unfolded more subtly in day-to-day life in the church.[123] Because officials’ employment contracts were placed within a gospel book and confirmed by kissing the body of Christ in an otherwise liturgical setting, church officials may have understood self-sacrifice to be a part of their roles. Thus, whenever officials underperformed on that expectation, they technically failed to live up to the responsibilities of their offices.

Swearing on the Arenberg Gospels also acted as a community bonding ritual: a rite of passage in which many new officials took part, often within the same ceremony, thus helping them connect over their shared duties. Uniting church officials in this way might have otherwise had the potential to threaten higher authorities in the church, if, for instance, officials lower down in the church’s hierarchy collectively advocated for increased recognition or standing. However, because swearing oaths on the gospel book fostered fraternity both among officials and between officials and Christ, the oath ritual may have convinced officials that, if they did not sacrifice to improve the church, they not only let down their brothers but also dishonored the lord.

By persuading church officials to embody Christ’s sacrifice when they served the Church, the Arenberg Gospels’ use in oath rituals enriched the Church while subordinating officials within an almost feudal organizational structure. The oath book reinforced the Church’s authority over its officials and moralized the Church’s pecking order, with vicars indebted to canons, all church officials indebted to their chapter, and the church of St. Severin indebted to Rome. Because church officials’ oaths established their vassalage to the lord’s mystical body, this agreement morally and legally bound officials to self-martyrdom.

I would like to thank Asa Mittman for his invaluable feedback on my essay and Cynthia Hahn for her guidance and support throughout my writing process.

References

| ↑1 | The origins and dating of the Arenberg Gospels are debated. The Morgan Library & Museum dates the book to c. 1000–1020. T. A. Heslop and Robert Deshman also support an early eleventh-century dating, whereas Jane E. Rosenthal and T. A. M. Bishop date the manuscript to the late tenth century. I agree with a slightly earlier dating, within the range of the last decade of the tenth century to the first decade of the eleventh century, due to the Insular characteristics of the script and the arrangement of the leaves in the old Insular method (HFHF). Though scholars have studied the Arenberg Gospels’ origins and movement to Cologne, the manuscript’s use in oath rituals has received little scholarly attention. “Gospel Book,” The Morgan Library & Museum, accessed September 22, 2022, https://www.themorgan.org/manuscript/159161; Jane E. Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1974), 1, 73; “M.869,” CORSAIR, The Morgan Library & Museum, accessed September 22, 2022, http://corsair.themorgan.org/msdescr/BBM0869a.pdf; T. A. M. Bishop, “NOTES ON CAMBRIDGE MANUSCRIPTS: Part IV: MSS. Connected with St Augustine’s Canterbury,” Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society 2, no. 4 (1957): 323–36, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41155317; Robert Deshman, “Christus rex et magi reges: Kingship and Christology in Ottonian and Anglo-Saxon Art,” Frühmittelalterliche Studien 10, no. 1 (1976): 367–405, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110242096.367; T. A. Heslop, “The Production of ‘de Luxe’ Manuscripts and the Patronage of King Cnut and Queen Emma,” Anglo-Saxon England 19 (1990): 151–95, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44509957; Richard Gameson, The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995), 17; Richard Gameson, “The Anglo-Saxon Artists of the Harley 603 Psalter,” JBAA 143 (1990): 40–41. This approach is inspired by Arjun Appadurai’s work on the social life of things. See: Arjun Appadurai, “Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 3–63, https://hdl-handle-net.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/2027/heb32141.0001.001; Arjun Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), https://hdl-handle-net.proxy.wexler.hunter.cuny.edu/2027/heb32141.0001.001. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Arenberg Gospels is housed at The Morgan Library & Museum. The full-page Crucifixion miniature on fol. 9v precedes eight historiated Eusebian canon tables on fols. 10–13. The manuscript also contains four full-page Evangelist portraits after the prologues to the Evangelists’ respective Gospels and a decorative incipit page after each Evangelist portrait. The same-colored inks appear throughout the drawings and decorative lettering, indicating that the same artist likely drew both. “Gospel Book (Arenberg Gospels),” CORSAIR Online Catalogue, The Morgan Library & Museum, accessed September 26, 2022, http://corsair.themorgan.org/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=159161; The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869”; Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 2. |

| ↑3 | The Insular method was unique to the British Isles but fell out of favor in Britain by the late tenth century. Michael Hare, “Cnut and Lotharingia: Two notes,” Anglo-Saxon England 29 (2000): 275, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675100002489; Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 2007), 15; The Morgan Library & Museum, “Gospel Book (Arenberg Gospels).” |

| ↑4 | This darkening likely resulted from rebinding or improper supports or storage at certain points in the book’s history, while the text in the opening quire may have flaked due to either human contact or unstable compounds in the paint reacting to more frequent exposure because of their placement in the book. Clemens and Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies, 101–04, 106–08. |

| ↑5 | The manuscript was in the collection of Canon Franz Pick (1750–1819) before the Duke of Arenberg purchased it in 1802, who kept it in the Arenberg Library at Brussels. In 1954, The Morgan Library & Museum purchased the book from Duke Engelbert Charles d’Arenberg. It is currently bound in a nineteenth-century German red velvet cover with two silver gilt clasps studded with amethysts and agates from the Three Kings Shrine in Cologne by Nicholas of Verdun. The Morgan purchased the manuscript without its original upper cover decoration, which Jacques Seligmann removed and sold as separate components. Prior to the book’s acquisition, its upper cover featured an arrangement of enamels, gems, and a fifteenth-century jet figure of St. James Major. At least four of its enamel plaques were of a late twelfth-century Rhenish make and featured geometrical and floral decorations in cloisonné and champlevé enamel. See: Konrad Hoffman, The Year 1200: A Centennial Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1970), 185; The Morgan Library & Museum, “Gospel Book (Arenberg Gospels).” |

| ↑6 | Eyal Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England (Manchester: Manchester University Press: 2013), 60–61; Joseph A. Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), trans. Rev. Francis A. Brunner, C.SS.R., rev. Charles K. Riepe (New York: Benziger Brothers, Inc., 1959), 284. |

| ↑7 | The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑8 | The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑9 | The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑10 | Arjun Appadurai, “Mediants, Materiality, Normativity,” Public Culture 27, no. 2 (2015): 224, https://www.dhi.ac.uk/san/waysofbeing/data/communities-murphy-appadurai-2015.pdf . https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2841832; Marlene Villalobos Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” in The Social Life of Illumination, eds. Joyce Coleman, Mark Cruse, and Kathryn A. Smith (Turnhout: Brepols, 2013), 17–52, https://www.academia.edu/19932974. |

| ↑11 | Oaths were sworn before the thing (or þing), a public assembly or legislative council which was both a body of people and a site to which communities travelled to cement social bonds and settle legal disputes by engaging in rituals. Landnámabók includes accounts of swearing oaths to the gods on rings, which suggests that this practice predates Christianization (see: Ari Þorgilsson, The Book of the Settlement of Iceland: Tr. From the Original Icelandic of Ari the Learned, trans. Thomas Ellwood (Kendal: T. Wilson, 1898), 177, https://archive.org/details/booksettlementi00ellwgoog/page/n220/mode/2up). For a summary of ancient and medieval Jewish oath swearing practices, see: “Oath,” Jewish Virtual Library, accessed June 5, 2024, https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/oath. Silvio Meli, “The oath: genesis, development and Augustinian orientation – a revisitation in the light of recent scholarship,” ELSA Malta Law Review 6 (2016): 242, 247, https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/64571; Alexandra Sanmark, “At the Assembly: A Study of Ritual Space,” in Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, c. 650–1350, eds. Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, and Thomas Småberg (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers n.v., 2015), 87, https://doi.org/10.1484/M.RITUS-EB.5.109653; Gerd Althoff, “Symbolic Communication and Medieval Order: Strengths and Weaknesses of Ambiguous Signs,” in Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, c. 650–1350, eds. Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, and Thomas Småberg (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers n.v., 2015), 69–70, https://doi.org/10.1484/M.RITUS-EB.5.109653; Cornelius Tacitus, Tacitus: De vita et moribus Julii Agricolae et De Germania. Tacitus: Agricola and Germania; with introduction and notes by Alfred Gudeman (Massachusetts: Allyn and Bacon, 1900), ch. 11–12, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044102771706; Shevu. 38b; Yad, Shevu’ot, 11:8; ḤM 87:15. |

| ↑12 | Dmitri Zakharine, “Medieval perspectives in Europe: Oral culture and bodily practices,” in Body – language – communication: an international handbook on multimodality in human interaction, eds. Cornelia Müller, Alan Cienki, Ellen Fricke, Silva Ladewig, David McNeill, and Sedinha Tessendorf (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 2013), 346, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110261318.343. For more on the meaning and significance of gestures in the medieval period, see: Jean-Claude Schmitt, La raison des gestes dans l’Occident médiéval (Paris: Gallimard, 1990). |

| ↑13 | A comical subversion of this trope appears in the Chronicle of St. Denis (see: Frederic Austin Ogg, ed., “The Chronicle of St. Denis Based on Dudo and William of Jumièges,” in A Source Book of Mediaeval History: Documents Illustrative of European Life and Institutions from the German Invasions to the Renaissance (New York: Cooper Square Publishers, 1972), 165–73, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/843bertin.asp.). Verse 1260 in the Lîvre de jostice et de plet describes the kiss between lord and vassal (for the full verse, see: Emile Chénon, Le rôle juridique de l'”osculum” dans l’ancien droit français (Nogent-le-Rotrou: Imprimerie Daupeley-Gouverneur, 1923), 17, https://books.google.com/books?id=TKEsAQAAMAAJ). J. Russell Major, “‘Bastard Feudalism’ and the Kiss: Changing Social Mores in Late Medieval and Early Modern France,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History 17, no. 3 (1987): 509–10, 513, https://doi.org/10.2307/204609; Jón Viðar Sigurðsson, “The Wedding at Flugumýri in 1253: Icelandic Feasts between the Free State Period and Norwegian Hegemony,” in Rituals, Performatives, and Political Order in Northern Europe, c. 650–1350, eds. Wojtek Jezierski, Lars Hermanson, Hans Jacob Orning, and Thomas Småberg (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols Publishers n.v., 2015), 224, https://doi.org/10.1484/M.RITUS-EB.5.109653; Zakharine, “Medieval perspectives in Europe: Oral culture and bodily practices,” 347. |

| ↑14 | Monasteries and cathedrals prevalently used gospel books as oath books, though other liturgical books were used when gospel books were not available, for example, in some parish churches. Ecclesiastics usually amended the gospel books they used in their oath ceremonies with oath formulae and documents related to canon law. Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 61–62, 78, 85–87. |

| ↑15 | Illustrations in the Heidelberger Sachsenspiegel demonstrate the protocol for swearing on reliquaries (see: “Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, Cod. Pal. germ. 164,” Bibliotheca Palatina – digital, accessed June 6, 2024, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg164/). Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 62. |

| ↑16 | This influenced the form of later oath rituals. The rubrics in the Sainte-Chapelle missal illustrate the place of the priest’s kiss of the gospel book in the order of the Mass by fourteenth century (see: “Harley MS 2891,” British Library, accessed June 6, 2024, https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?index=0&ref=Harley_MS_2891). Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), 482; Michalina Duda and Sławomir Jóźwiak, “On What Were Oaths Taken in Christian Latin Europe in the High Middle Ages (12th-Early 14th Centuries)?,” Mediaevistik 32 (2019): 151, https://doi.org/10.3726/med.2019.01.06. |

| ↑17 | Moshe Barasch, “The Departing Soul. The Long Life of a Medieval Creation,” Artibus et Historiae 26, no. 52 (2005): 21, https://doi.org/10.2307/20067095. |

| ↑18 | Though discussing departing souls, Moshe Barasch makes a similar argument about the iconography of a series of woodcuts from a book of L’art de bien vivre et bien mourir. See: Barasch, “The Departing Soul. The Long Life of a Medieval Creation,” 21–22. Jane Geddes provided this commentary on the English translation of the Albani Psalter, which was translated by Sue Niebrzydowski. “Page 243 Commentary,” Commentary, St Albans Psalter, accessed March 12, 2023, https://www.albani-psalter.de/stalbanspsalter/english/commentary/page243.shtml. |

| ↑19 | St Albans Psalter, “Page 243 Commentary.” |

| ↑20 | Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 65; Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), 286–87; Romans 1:16. |

| ↑21 | Kathryn M. Rudy, “Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts through the Physical Rituals they Reveal,” Electronic British Library Journal (2011): 56, http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/article5.html. |

| ↑22 | Rudy, “Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts through the Physical Rituals they Reveal,” 1. |

| ↑23 | Rudy, “Kissing Images, Unfurling Rolls, Measuring Wounds, Sewing Badges and Carrying Talismans: Considering Some Harley Manuscripts through the Physical Rituals they Reveal,” 2. |

| ↑24 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 23; Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), 288–89, 482. |

| ↑25 | Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 60–62. |

| ↑26 | For example, in civic settings. David Ganz, “Touching Books, Touching Art: The Tactile Dimensions of Sacred Books in the Medieval West,” Postscripts 8.1-2 (2012): 95–96, https://doi.org/10.1558/post.32702. |

| ↑27 | “Oath of office,” The Morgan Library & Museum, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.themorgan.org/manuscript/112377; “MS M.300 fol. 3r,” Medieval & Renaissance Manuscripts, The Morgan Library & Museum, accessed January 30, 2023, http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/2/112377; “M.300,” CORSAIR, The Morgan Library & Museum, published June 1936, http://corsair.themorgan.org/msdescr/BBM0300a.pdf; “Customary and Oath Book for the town of Lézat-sur-Lèze, with accessory texts; Arbitration Award (1327),” TEXTMANUSCRIPTS, Les Enluminures, accessed January 30, 2023, https://www.textmanuscripts.com/medieval/customary-oath-book-60907. |

| ↑28 | Les Enluminures, “Customary and Oath Book for the town of Lézat-sur-Lèze, with accessory texts; Arbitration Award (1327)”; Major, “‘Bastard Feudalism’ and the Kiss: Changing Social Mores in Late Medieval and Early Modern France,” 510. |

| ↑29 | For a discussion of fealty oaths among the counts of Foix, see: Major, “‘Bastard Feudalism’ and the Kiss: Changing Social Mores in Late Medieval and Early Modern France,” 530–31; Les Enluminures, “Customary and Oath Book for the town of Lézat-sur-Lèze, with accessory texts; Arbitration Award (1327).” |

| ↑30 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 144. |

| ↑31 | The Arenberg artist employed a colored line drawing technique, leaving figures unpainted except for some brownish shading around outlines. This technique is attested in earlier and contemporaneous English manuscripts. For more information, see: Gameson, The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church, 12–13. |

| ↑32 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 87. Mary represents the source of Christ’s human nature in early English Crucifixion scenes. Barbara C. Raw, Trinity and Incarnation in Anglo-Saxon Art and Thought, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England, 21 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 177, https://books.google.com/books?id=NPXSH04ghiUC. |

| ↑33 | For example, “Pained perplexed & punctured — / yet I was bowed by crowds, / their hands humble-minding me, / my valor, my greatness.” (59–60a). “The Dream of the Rood,” Old English Poetry in Facsimile 2.0, eds., trans., Martin Foys, et al. (Madison, WI: Center for the History of Print and Digital Culture, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2019–), https://oepoetryfacsimile.org. “The Dream of the Rood” equates the cross with Christ, as do Aelfric’s sermons. See: Aelfric Abbot of Eynsham, “The Fifth Sunday in Lent,” in Homilies of the Anglo-Saxon Church: The First Part Containing the Sermones Catholici, Or Homilies of Aelfric in the Original Anglo-Saxon, with an English Version, ed., trans., Benjamin Thorpe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 225–40, https://books.google.com/books?id=zNhOPql4sX0C. Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 78. |

| ↑34 | “Sacramentarium gelasianum [Sacramentaire gélasien, dit de Gellone (Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert)].,” Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed June 12, 2024, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b60000317/f10.item. |

| ↑35 | “Pontificale Shirborniense.,” Bibliothèque nationale de France, accessed June 12, 2024, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b6001165p/f14.item. |

| ↑36 | For a discussion of the iconographic similarities between the two manuscripts, see: Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 106–55. |

| ↑37 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 145. |

| ↑38 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 145. For more on the Eucharistic theology of Radbertus, see: Paschasius Radbertus, De corpore et sanguine Domini: cum appendice Epistola ad Fredugardum, trans. Beda Paulus (Turnhout, Belgium: Typographi Brepols, 1969); Owen M. Phelan, “Horizontal and Vertical Theologies: ‘Sacraments’ in the Works of Paschasius Radbertus and Ratramnus of Corbie,” The Harvard Theological Review 103, no. 3 (2010): 271–89, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40731071. |

| ↑39 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 94, 148. |

| ↑40 | Christ figures typically dominate the cross in early English Crucifixion scenes. Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 102–03. |

| ↑41 | Beatrice E. Kitzinger, The Cross, the Gospels, and the Work of Art in the Carolingian Age (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 26–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108553636 |

| ↑42 | Kitzinger, The Cross, the Gospels, and the Work of Art in the Carolingian Age, 76. |

| ↑43 | For a discussion of purple’s symbolism from antiquity to the medieval period, see: Charlene Elliott, “Purple Pasts: Color Codification in the Ancient World,” Law & Social Inquiry 33, no. 1 (2008): 173–94, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20108752. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-4469.2008.00097.x |

| ↑44 | Cynthia Hahn, “What do reliquaries do for relics?,” Numen 57, no. 3-4 (2010): 297, DOI: 10.1163/156852710X501324. For more on porphyry, see: A. A. Vasiliev, “Imperial Porphyry Sarcophagi in Constantinople,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 4 (1948): 1–26, https://doi.org/10.2307/1291047. |

| ↑45 | Hahn, “What do reliquaries do for relics?,” 297. |

| ↑46 | The historical character of the Arenberg Gospels’ architectural framing devices likely derives from the buildings in the Utrecht Psalter. Gameson, The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church, 17–18. |

| ↑47 | Barbara C. Raw argues this placement of the Crucifixion miniature is an early English feature (see: Raw, Trinity and Incarnation in Anglo-Saxon Art and Thought). The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑48 | For a detailed discussion of the canon tables, see: Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 188–99, 211–24. On Eusebian canon tables in general, see: Clemens and Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies, 185. |

| ↑49 | Additionally, all four Evangelist symbols are shown holding either a codex or scroll. Gameson, The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church, 100. |

| ↑50 | Kitzinger, The Cross, the Gospels, and the Work of Art in the Carolingian Age, 127; Gameson, The Role of Art in the Late Anglo-Saxon Church, 99. |

| ↑51 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 155. |

| ↑52 | For information on the production of medieval manuscripts, see: Clemens and Graham, Introduction to Manuscript Studies, 3–64; Christopher De Hamel, Medieval Craftsmen. Scribes and Illuminators (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 45–69; Jiří Vnouček, “Illustrations for Instructions, the Book as Evidence. The Story of the Production of a Medieval Codex as Recorded in the Hamburg Bible,” in From Nature to Script. Reykholt, Environment, Centre, and Manuscript Making, eds. Helgi Þorláksson and Þóra Björg Sigurðardóttir (Reykholt: Snorrastofa, 2012), 199–229. |

| ↑53 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 19; John 1:14. |

| ↑54 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 20; Rabanus Maurus, Opusculum de passione Domini, Chap. V, https://www.documentacatholicaomnia.eu/04z/z_0788-0856__Rabanus_Maurus__Opusculum_De_Passione_Domini__MLT.pdf.html. |

| ↑55 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 18. |

| ↑56 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 22. |

| ↑57 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 18, 22. |

| ↑58 | On the significance of parchment’s organic nature in recording environmental, human, and non-human interactions, see: Bruce Holsinger, On Parchment: Animals, Archives, and the Making of Culture from Herodotus to the Digital Age (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2023). |

| ↑59 | Tim Ingold, “Materials against Materiality,” Archaeological Dialogues 14, no. 1 (2007): 12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203807002127 |

| ↑60 | The more oil parchment accumulates through handling, the more skin-like and, thus, the more human it becomes. Sarah Kay, Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 3, https://books.google.com/books?id=_5UtDwAAQBAJ. |

| ↑61 | Herbert L. Kessler, Seeing Medieval Art (Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 2004), 34. |

| ↑62 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 281. |

| ↑63 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 280. |

| ↑64 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 155. |

| ↑65 | The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑66 | Rosenthal, “The Historiated Canon Tables of the Arenberg Gospels,” 280. |

| ↑67 | Hennessy, “The Social Life of a Manuscript Metaphor: Christ’s Blood as Ink,” 23. |

| ↑68 | Susanne Wittekind, “Heribert and Anno II of Cologne: Two Saintly Archbishops, Their Cult, and Their Romanesque Shrines,” Romanesque Saints, Shrines and Pilgrimage (2020): 34, https://khi.phil-fak.uni-koeln.de/sites/kunstgeschichte/Dateien_Webrelaunch/Wiss._HP_s/Wittekind/Literatur_neu_Juni_2020/Wittekind_Heribert_and_Anno_II_of_Cologne_in_Romanesque_Saints_Shrines_and_Pilgrimage_2020.pdf. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429260162-3 |

| ↑69 | The original decree was issued between 1073 and 1075. The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑70 | Alternatively, T. A. Heslop has argued that King Cnut commissioned the manuscript as a royal gift; in which case, he would have it brought it with him on his visit to Cologne in 1027. However, this hypothesis clashes with the Insular characteristics of the script, which fell out of favor by the early eleventh century following Dunstan’s reforms. Moreover, the scribe’s marginal notes indicate its liturgical use in England. Another possibility is that a church official at Christ Church gifted the manuscript to Archbishop Friedrich I of Cologne when he presided over the marriage of Matilda and Henry V, and Friedrich, in turn, gave the manuscript to St. Severin when he visited the church in 1109. This theory accounts for the date of the first inscription from Cologne, but it does not explain why church officials at St. Severin would have recorded a papal decree of Heribert’s canonization if the saint had no connection to the manuscript. Nor does it account for the time between the date of these first inscriptions and the earliest date of the oath records from St. Severin. Heslop, “The Production of ‘de Luxe’ Manuscripts and the Patronage of King Cnut and Queen Emma,” 172; Hare, “Cnut and Lotharingia: Two notes,” 272, 275; The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869”; “Erzbischof Friedrich von Köln schenkt dem Severins – 1109,” Urkunden, Best. 264 Severin 1158 – 1802, Das digitale Historische Archiv Köln, accessed May 29, 2024, https://historischesarchivkoeln.de/document/Vz_FBC3461A-48A2-48E0-8D89-2AAB3B25000B. |

| ↑71 | The church of St. Severin bore little connection to Heribert during this period, and no records indicate that Heribert donated to St. Severin during his lifetime, whereas Heribert made extensive donations to Deutz. Wittekind, “Heribert and Anno II of Cologne: Two Saintly Archbishops, Their Cult, and Their Romanesque Shrines,” 27, 29; “fol. 6: Erzbischof Heribert von Köln überweist der – 1019 Mai 03,” Repertorien und Handschriften, Best. 208 Deutz, Abtei – 1003 – 1802, Das digitale Historische Archiv Köln, accessed May 29, 2024, https://historischesarchivkoeln.de/document/Vor_DCD413B7-3984-4AD6-B885-FC965471C9A3. |

| ↑72 | Wittekind, “Heribert and Anno II of Cologne: Two Saintly Archbishops, Their Cult, and Their Romanesque Shrines,” 29–31; The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑73 | Jennifer P. Kingsley, “Picturing the Treasury: The Power of Objects and the Art of Memory in the Bernward Gospels,” Gesta 50, no. 1 (2011): 19, https://doi.org/10.2307/41550547. |

| ↑74 | Kingsley, “Picturing the Treasury: The Power of Objects and the Art of Memory in the Bernward Gospels,” 19. |

| ↑75 | Patrick Geary, “Sacred Commodities: The Circulation of Medieval Relics,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 173; Filippo Carlà, “Exchange and the Saints: Gift-Giving and the Commerce of Relics,” Gift-Giving and the ‘Embedded’ Economy in the Ancient World (2014): 403, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316494322_4_F_Carla_M_Gori_eds_2014_Gift_giving_and_the_embedded_economy_in_the_ancient_world_Heidelberg_Universitatsverlag_Winter; Marcel Mauss, The Gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies, trans. W. D. Halls (London and New York: Routledge, 2002), 50. |

| ↑76 | Carlà, “Exchange and the Saints: Gift-Giving and the Commerce of Relics,” 421. |

| ↑77 | In total, sixteen of the Arenberg Gospels’ oaths date to the fourteenth century, three date to the fifteenth, one dates to the sixteenth, and two date to the seventeenth. The later records feature oaths for positions either not included in the earlier records or revised versions of the existing formulae for certain roles. |

| ↑78 | Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 79. |

| ↑79 | In addition to the gospel book’s general liturgical symbolism, church officials’ oaths on fols. 124–126 are placed close to pages with the scribe’s marginal notes, so they may have assumed the book’s use as a lectionary on that basis. The Morgan Library & Museum, “M.869.” |

| ↑80 | Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), 145. |

| ↑81 | “I, [name], dean,” “I, [name], canon,” etc. The German oaths use similar phrasing in translation: “So wahr mir gott helfe und diese heiligen [Evangelien]” (So help me God and these sacred [Gospels]). Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 79. |

| ↑82 | Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 79. |

| ↑83 | Poleg, Approaching the Bible in Medieval England, 79. |

| ↑84 | Jungmann, The Mass of the Roman Rite: Its Origins and Development (Missarum Sollemnia), 390. |

| ↑85 | “Detail Beelddocumenten,” Erfgoed ‘s-Hertogenbosch, accessed June 28, 2024, https://hdl.handle.net/21.12121/14858590. |

| ↑86 | Michael D. Barbezat, “Bodies of Spirit and Bodies of Flesh: The Significance of the Sexual Practices Attributed to Heretics from the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 25, no. 3 (2016): 412–13, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44862359. https://doi.org/10.7560/JHS25301 |