Kathleen Biddick • Temple University

Recommended citation: Kathleen Biddick, “Sexing the Cherry,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1(2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/BMSW5782.

In the epilogue to her book, Sacrifice your Love: Psychoanalysis, Historicism, Chaucer, Aranye Fradenburg urges medievalists to “enjoy” medieval studies:

[W]e would do well to teach and write more explicitly about enjoyment. We should also be more enjoyable. I want to be clear, though, that by “more enjoyable” I do not mean “more pleasurable” or “easy.” …Pleasure [therefore] always poses a potential threat to experiences of curiosity and wonder, to risk, to work that has not yet become habitual (pleasure can be quite comfortable with the latter). The survival of the humanities in the academy depends on our power to provoke curiosity and wonder. Let’s take more risks with our enjoyment, with the fact that what makes our work distinctive is precisely the foregrounding of enjoyment.[1]

These Kalamazoo sessions held in honor of Madeline Caviness invite us to explore the risks of enjoyment (hers and ours) posed by her scholarship. We would not have this celebration had her research and pedagogy not inspired curiosity and wonder across generations of scholars. Three processes at play in her work have compelled me: 1) shattering; 2) grafting; 3) queer performance. At an interview with Madeline held in March 2005 at the Medieval Academy meeting in Boston, I had the chance to explore these themes with her (see full text of interview in this issue.) The word “inter-view” is important to me, because it embodies a notion of a gaze that can never be one and the idea of a conversation that can never be a monologue. The “inter” of “interview” also poses rich questions about the “now” of Madeline Caviness’ oeuvre. In what follows I interweave my reflections on the pleasure and challenge of her publications with comments taken from her interview. I hope you will enjoy this collage and use it for your own meditations on what is the “now” of these kinds of methodologies in medieval studies and beyond.

I first met Madeline Caviness in 1993 at the Medieval Academy Meeting held in Boston that year. Volume 68 of Speculum, a special issue on Studying Medieval Women edited by Nancy Partner, to which we had both contributed, had just come out; that year Madeline had also been awarded the prestigious Haskins Medal. I confess to being a bit fearful of meeting such a distinguished medievalist. I knew that since the inception of the Haskins award in 1940, up to 1993, only two other women, Bertha Putnam (1940) and Pearl Kibre (1964) had been Haskins recipients. I had, however, already developed an appealing fantasy of Madeline. It came from the novel, entitled Sexing the Cherry (1991), by the British novelist Jeanette Winterson. Set in London during the English Revolution, the protagonist Dog Woman describes the following traumatic event of the English Civil War. I think it is worth citing at length:

I went to a church not far from the gardens. A country church famed for its altar window where our Lord stood feeding the five thousand. Black Tom Fairfax, with nothing better to do, had set up his cannon outside the window and given the order to fire. There was no window when I got there and the men had ridden away.

There was a group of women gathered round the remains of the glass which coloured the floor brighter than any carpet of flowers in a parterre. They were women who had cleaned the window, polishing the slippery fish our Lords had blessed in his outstretched hands, scraping away the candle smoke from the feet of the Apostles. They loved the window. Without speaking, and in common purpose, the women began to gather the pieces of the window in their baskets. They gathered the broken bread, and the two fishes, and the astonished faces of the hungry, until their baskets overflowed as the baskets of the disciples had overflowed in their original miracle. They gathered every piece, and they told me, with hands that bled, that they would rebuild the window in a secret place. At evening, their work done, they filed into the little church to pray, and I, not daring to follow, watched them through the hole where the window had been.

They kneeled in a line by the altar, and on the flag floor behind them, invisible to them, I saw the patchwork colours of the window, red and yellow and blue. The colours sank into the stone and covered the backs of the women, who looked as though they were wearing harlequin coats. The church danced in light. I left them and walked home, my head full of things that cannot be destroyed.[2]

This passage might seem a bit corny, but its image of violently shattered glass lures me in. Recall that shattering is the English word often used to translate the French psychoanalytic term of jouissance. Jouissance is the term used for the vanishing point of desire in libidinal rapture— shattering just beyond the point of endurance. We think of jouissance most commonly in terms of sexual orgasm and in so doing we unfortunately limit its modalities. Put another way, the mind, too, is an organ and subject to its own unbearable intensities. I read in the scholarly method practiced by Madeline Caviness, a double-shattering. Shards of painted glass shattered by the colliding drives of iconoclasm, world war, and collectors have constituted much of the evidentiary base of her research. To the analysis of such fragments, she has brought the most exquisite attention and has succeeded brilliantly in virtual reconstructions of their contextual ensembles. The sheer intellectual breadth and dedication at stake in such virtual recreation is shattering. Caviness has worked like a translator of painted glass in a way similar to what Walter Benjamin has described for the literary translator in his famous essay “On Translation.” The translator, according to Benjamin, has nothing but the shards of a vase to piece together painstakingly. The translation will never again be whole. So, too, Caviness, has translated medieval painted glass fragments into a “now” that for me is a time that is not yet fully past nor not yet fully present either.

In preparation for our interview I had sent Madeline a copy of the passage from Sexing the Cherry quoted above, and I asked her if it had any resonance for her. This is what she said:

Yes, so much….though I never say “our Lord” (I became atheist at about 4 years old. The bombing had an enormous effect on me-my brother and I went out one morning to find where the close bomb had dropped the night before, and collected shrapnel from a crater near a friend’s house. We saw London burning from our upstairs windows, 30 miles away in Chesham Bois, Bucks. I love people, but that is always tinged by knowing they have to die. I have worked very hard to ensure that medieval stained glass will not “die”. And I have spent hours trying to match scattered fragments, trying to get them back together…I am very upset now at what they are doing in Iraq, to people and cultural treasures.

As we celebrate the scholarly career of Caviness, we might also ask: what is her relationship to different generational cohorts of scholars represented in these sessions? How do different generations of academic feminists relate to each other? How does a supposed “older” scholarship in feminist history intersect with a purported “new” queer theory? These are complicated questions indeed. In 2001, Caviness broached them in her publication, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages, wherein she seems to perceive a “break” in her method. In the acknowledgements, she noted with sadness the decease of her parents and wished– “would that they had lived to see my feminist reincarnation.”[3] Does Visualizing Women really represent a break in her method? I propose that the process of “grafting” better describes her evolving methodology. Grafting is defined as that generative process whereby a plant stock is fused with another stock (for example, joining a tangerine with a grapefruit) to produce a hybrid. The two plants take advantage of each other and produce a third entity without “parent.” I would argue that the graft was always already there in her writing—we lose the richness of her method if we compress it into a story of supersession claiming that theoretical feminism superseded a traditional art- historical study of painted glass. This concept of grafting also provides a useful way of imagining the relations of the different cohorts of scholars participating in these sessions. Their contributions sustain the grafting process modeled by Caviness. A recent essay by Elizabeth Freeman, entitled “Packing History, Count(er)ing Generations”, eloquently describes such generational relations as a “temporal crossing, with the movements of signs, personified as bodies, across the boundaries of age, chronology, epoch—a kind of “temporal drag.”[4]

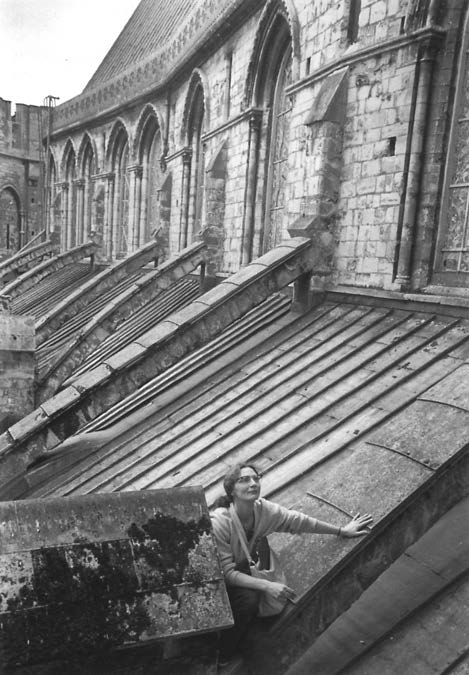

If enjoyment is always embodying, no matter how shattering the jouissance might be, it would be negligent of me to ignore the embodiment of Caviness as a scholar. Consider this photograph taken in 1970 by Verne Caviness, her husband. It serves as the frontispiece to her book, Paintings of Glass.

You see Madeline at age thirty-two scrambling on the aisle-roof of Canterbury Cathedral. If you read the prefaces and acknowledgements of her publications, you will learn about the pleasure that she took in the demands placed on her by the study of painted glass. She had to climb scaffolding and scale roofs in order to record and photograph her archival material. When I looked at this picture, I saw the image of an intrepid 32 year-old woman in whom flickered a tom-boy (a tree-climber for sure!). I asked Madeline about this picture in our interview in order to bring into view the joyous embodiments of her scholarship. This was her reply:

That was 50 feet up without a parapet. [I] Grew up a tom boy, wearing my older brother’s out-grown clothes (WW II) and following him up trees etc. I was nearly expelled from a convent school at about 5 for firing a catapult…the glazier who helped me on the project, George Easton, a poor boy from Canterbury, began to work at 16 and used to slide down the upper roof on the seat of his pants to get to the other side.

It is time now to turn to the question of queer performance in her brilliant career. In that her scholarship does not engage with problems of homosociality and same-sex desire, it might be thought that Caviness missed the queer turn in medieval studies. And yet, I would argue that Caviness’s work does engage queer performance, if not a queer analytic. In its love of fragments, in its careful recuperation and reconstitution of shards, her method bears all the markings of camp performance. Camp depends not just on inverting binaries (male/female; high-brow/pop etc), but also on the resuscitation of obsolete cultural texts. When some scholars are “bothered” by her research, I would argue, it is because of this camp performance. She has marked feminism as an incomplete political and scholarly project (oh, if only it would go away, you can almost here her detractors sigh). One of the performances of Caviness that I like best is the doughty way in which she always wears her Haskins medal at official academic functions. I asked Madeline about her medal and her answer leaves us with important issues to ponder when we consider what is the “now” of Medieval Studies and what is the “now” of the work of Madeline Caviness. I close with her words:

Well yes I think it was an important medal for women when I won it. And I am amused to wear it because as a woman I can and the men can’t or don’t. But it is also a talisman, especially since my feminist work has sat so badly with some of the very same people who I know respect the medal—so it’s in their face. It has always puzzled me that my books won prizes (the first book was awarded the John Nicholas Brown prize, and last year I received the AAUW Educational Foundation senior scholar award, along with Madelyn Albright who got the service award)—yet I have given up applying for research fellowships. I have not had a funded sabbatical since 1986-87.

Kathleen Biddick is a Professor of History at Temple University. Biddick’s interests are in critical historiography, especially discussions of temporality, cultural studies of technology, gender studies and medieval history. Her most recent monograph, The Typological Imaginary: Circumcision, History, Technology extends her critical work on temporality and periodization.

References

| ↑1 | L. O. Aranye Fradenburg, Sacrifice your Love: Psychoanalysis, Historicism, Chaucer (Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), 247. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Jeanette Winterson, Sexing the Cherry (New York: Vintage Books, 1991), 66. |

| ↑3 | Madeline Harrison Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, Scopic Economy (Philadelphia PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 230. |

| ↑4 | Elizabeth Freeman, “Packing History, Count(er)ing Generations,” New Literary History 31 (2000), p. 733. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2000.0046 |