Severed Heads, Abnormal Sights, and Perplexity

Sonja Drimmer

October 31, 2016

Severed heads were a familiar sight during the Wars of the Roses; but though familiar, they were not normal. The chronicles that relate the events of these years are crowded with accounts of decapitations and spikings—evidence that their presence was, if common, certainly aberrant enough to warrant comment. One chronicler relates that in 1450 “so many were executed that twenty-three heads stood upon London Bridge” (Kingsford, 162). The gruesome details of these exhibits are fleshed out in revolting array in my essay, “The Severed Head as Public Sculpture in Late Medieval England” for the forthcoming volume, The Art of War: Imagery, Ideology, Impact.

When I wrote that essay I could not have imagined the political climate of autumn 2016.

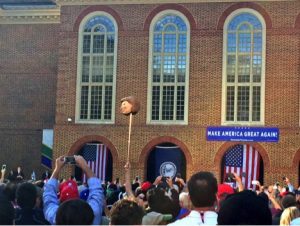

And so it was with dread that I learned of the severed and spiked head’s resurrection in American political culture. Witnessed recently by journalists Katherine Faulders, Emily Stephenson, and Ashley Killough and reported via Twitter (our own answer to the medieval chronicles of the Wars of the Roses) were effigial heads of Hillary Clinton mounted on pikes at rallies in support of GOP presidential nominee Donald Trump.

Stephenson saw it through the lens of Hollywood, while Keith Olbermann tracked it in medieval history.

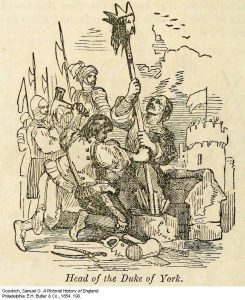

Few medieval representations of heads on pikes survive, perhaps in part because no one needed or wanted to be reminded of a sight to which they might well have been exposed in the flesh. But a fanciful illustration from a nineteenth-century pictorial history of England resonates well enough with what we now see, aghast, in rallies and on our computer and phone screens across the country and the world.

phone screens across the country and the world.

In a video editorial, Olbermann went on to give a voice to the distress I felt when seeing, second-hand, the violent ostentation that has elbowed out civic discourse in this election cycle.

Olbermann opens on a note of perplexity. Could that…is that really? No, it can’t…but, my God, it is. It is Clinton’s head. Absent a body. And mounted on a pike. It is deranged—out of order with what we think of when we think of political speech. In the words of Hillary Clinton herself, it is “horrifying” to see how very far we have wandered from the norm.

If you want, you can read any number of thought pieces on how it is that we got here. All of them crisp diagnostics with sensible explanations and lines of causality. Of course, their unspoken starting point is that something is now so awry that it requires an etiology.

But we are not unique in our outraged decorum.

In the middle of Warkworth’s Chronicle, the author pauses to report on the public’s horror at the atrocities laid before them. In response to the exhibition of bodies spiked from the buttocks through the head, “the people of the land were greatly displeased; and ever afterward the Earl of Worcester [who condemned the victims] was greatly hated among the people for the disordinate death that he caused, contrary to the law of the land” (Matheson, 102; my translation). Similarly the author of Gregory’s Chronicle relates that “Owen Tudor was taken and brought into Haverfordwest, and he was beheaded at the market place, and his head set upon the highest point of the market cross. And a mad woman combed his hair and washed away the blood from his face. And she got candles and set about him burning more than 100 of them” (Gairdner, 210; my translation). To this so-called madwoman, a severed head looming over her town was an abomination. An anomaly needing righting. A non-sensical thing to which she gave more sense by treating it like a relic.

All of this is to say that if this most recent imagined violence against Clinton has a medieval flavor, the perplexity that so many of us experience at witnessing its occurrence is no less medieval.

But perplexity is ineffectual. Perplexity ignores that the severed head (albeit a fabricated one) is not a deviation from the norm. Perplexity denies that this is our new normal, not just a blip in the news cycle to retweet and forget.

It is on us not to be perplexed.

Sources:

Matheson, Lister M. Death and Dissent: Two Fifteenth-Century Chronicles. Suffolk: Boydell, 1999.

Gairdner, James (ed). Three Fifteenth-Century Chronicles, Historical Memoranda By John Stowe, The Antiquary, And Contemporary Notes of Occurrences Written by Him in the Reign of Queen Elizabeth. London: Camden Society, 1880.

Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (ed). Chronicles Of London. Oxford: Clarendon, 1905.

Sonja Drimmer is Assistant Professor of Medieval Art at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst. She has previously written about the author portrait in medieval manuscripts, the visual culture of late medieval literary culture, and the history of manuscript conservation and restoration.