Julia Perratore • The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Recommended citation: Julia Perratore, “The Waters of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/RNNM4628.

Fig. 1. A waterfall of the Verdus River, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert (Photo: author).

To walk the length of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert is to navigate a river, the Verdus. Though not the largest, most powerful, or best known waterway in southern France by far, its waters are essential to life in the town. In many places, the river does what it will, spilling over stones and swags of fern, leaving travertinous traces (Fig. 1). Yet it also pumps into mossy roadside basins and spurts by the bucketful from the fountain in the Place de la Liberté. Householders conjure the river whenever they turn on a tap. In Saint-Guilhem, and in the Gellone valley in which it is situated, the Verdus is both independent and managed, charting its own course and channeled by humans. In this respect, not much has changed since medieval settlers first encountered and interfered with the river in the ninth century, following the 804 foundation of the Benedictine monastery of Gellone by Guilhem, Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Toulouse. At this time, the agency of the Verdus and the will of the human collective first entered into what would become a constant state of negotiation. In the ensuing centuries, as the monastery grew, and Gellone came to be known as Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, the dynamic relationship between river and community became a central manifestation of broader tensions between wilderness and domestication that defined cenobitic life and identity.

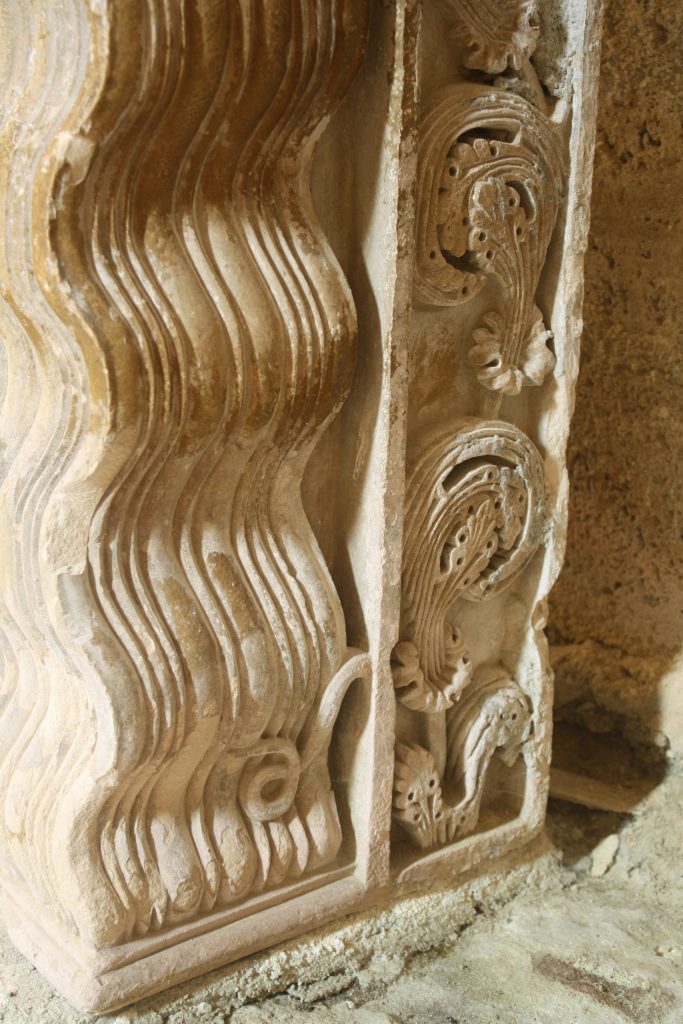

Fig. 2. Undulating supports from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now at The Met Cloisters.

Emblematic of these tensions is a curious carved decoration of ca. 1200 in the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, the undulating support (Fig. 2). The column of waves, an innovative feature of this monument and an unicum of late-Romanesque cloister sculpture, recalls nothing so much as the flow of water, expressed using some of the oldest and most basic visual language for representing this element. Originally functioning architecturally as responds addorsed to piers, seven exemplars of the undulating support survive from the dispersed monument today.[1] Inert but apparently fluid, solid yet seemingly penetrable, the meandering forms are as unlikely as they are charismatic. Their material tensions speak to the complex and sometimes contradictory roles of water in medieval Saint-Guilhem, which centered on the River Verdus but also extended well beyond it.

Water infuses the medieval history of Saint-Guilhem. The first monks of Gellone scarcely knew that they had settled on a site made by a river, a torrent that had emerged from the local limestone massif to carve out the valley over millions of years, although they saw evidence of the Verdus’ impact on the features of the land, and they defied it, diverting the river’s course to conform to their own needs. They built a monastery using blocks extracted from the limestone escarpments that it had revealed and the tufa deposits it had created. Venturing beyond the valley, the monks built bridges and weirs across an even more powerful waterway, the Hérault River, then harnessed the currents to power mills that pulverized grain and crushed olives. All the while, as the monks copied, read, and meditated on scripture, they dreamed of the waters evoked therein, from the Edenic rivers of Genesis to the riparian Paradise of the end of time. Drawing on these sources, when they wrote of their founder’s attraction to the Gellone valley as a desert, as well as his impulse to obliterate its wildness, they celebrated the waters of his own eyes, telling of how his streams of tears irrigated gardens and washed pavements to ensure the site’s cultivation and sanctification. Finally, when it came time to decorate the cloister, the communal heart of their everyday existence, the monks installed waters of stone cascading from ashlar cliffs.

In this essay, I seek to understand why and how the undulating supports came to be in the cloister and what significances might have coursed through them as the objects of monastic meditation. I read the undulating supports in light of the many different ways in which the monks actually interacted with and also idealized waters of all kinds: the waters of their faith, of their house’s foundation, and of their daily lives. I propose that these most unusual carvings served as enlivened conduits of monastic thought, channeling water’s scriptural, hagiographic, and actual presences to connect the community to its past, present, and future—temporalities that easily could flow into and against each other in medieval monastic minds. Through these sculpted passages, the monks could reflect on their abbey’s origins, consider their roles as spiritual and earthly authorities in the lands that they controlled, and look forward with anticipation to a final, eternal dwelling place in a well-watered garden. In all of this, the Gellone valley’s dynamic hydroscape of rivers, waterfalls, caverns, and slippery tufa domes played an integral mediating role.

My inquiry into the Saint-Guilhem cloister carvings is in part inspired by Anne F. Harris’s advocacy for uncovering the “persistence of the natural within the sacred” in the medieval period, and I am especially interested in how “the natural” becomes entwined with the sacred and made to conform with the goals of the latter.[2] The broad question of what “nature” in the modern sense of the word—the collective phenomena of the non-human physical world—meant to medieval people is a complex one, especially because a clear divide existed between how medieval people actually experienced their environments and what they wrote about them.[3] The influential work of Marie-Dominique Chenu, who identified a twelfth-century “discovery of nature” in writings of this era, posited that this newfound awareness of the non-human world became a means of accessing the divine, placing “nature” in an intercessory position that scholars have since come to question.[4] Sara Ritchey, for one, has emphasized that a general conceptualization of the non-human world under the heading of “nature” did not exist in medieval minds and instead advocated for scholars to consider medieval engagements with and interpretations of the physical world in terms of the latter’s status as holy matter—the stuff of God’s creation and re-creation through the Incarnation. An important corollary to this work is an emphasis on the local and the specific rather than the universal.[5] Building on Ritchey’s work on the high and later Middle Ages, Danielle Joyner extended the discussion to the early medieval period, considering the savin bush represented on the Plan of St. Gall as a specific manifestation or anchor-hold of creation, a focal point that makes tangible the enormity of God’s work.[6]

I heed these studies’ notes of caution in treating “nature” as a broadly applicable medieval concept and take seriously their shared emphasis on the local and the importance of place in plumbing the depths of medieval relationships to the non-human world.[7] In so doing, by focusing on water, I embrace the challenge of thinking through the elements explored recently by many medievalists, considering water’s material form and its ability to act equally upon the shape of the land, the meditations of monks, and the creativity of sculptors.[8] I deem thinking through the elements to be a useful endeavor because this framework is based in a concept—the world’s composition of earth, air, fire, and water—that lay at the heart of medieval people’s understanding of their surroundings. Thinking through an element has the potential to open a window onto a broader understanding of the Gellone monks’ perspectives on the non-human world, and not exclusively as they were expressed in the visual arts. The expansiveness of an elemental exploration necessarily calls for different disciplinary lenses, from the “hard sciences” to the humanities. The studies I have consulted in my interpretation of the sculptures thus range from geological investigations of the Hérault region to literary criticism focused on medieval hagiography and chansons de geste, and from theology to the history of science and civil engineering. In its interdisciplinarity, my approach is fundamentally ecocritical, casting a wide net to better understand how cultural products express human relationships to the non-human world.[9]

Fig. 3. The Hérault River viewed from near Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert (Photo: Havang(nl), CC0, via Wikimedia Commons).

Although the topic of medieval monastic engagement with the environment is not one that should be explored uniquely at Saint-Guilhem, it should be plumbed no less urgently there, and not least because its sculpture features so many forms inspired by the natural world. For one, this Benedictine house of southeastern France inhabits a spectacular, often challenging terrain that the monks had to negotiate daily (Fig. 3). In addition to the interest that the site itself affords, the varied medieval texts recounting the monastery’s foundation reveal an attentiveness to the landscape that, if not in itself unusual, calls out for further exploration given its clear centrality to monastic self-fashioning.[10] Of course, the term “landscape” is a fraught one in itself, given that it arose to describe a genre of painting, and thus a particular, subjective view of the land.[11] Recognizing the pitfalls of employing this term, in this essay I intend it to refer to the ensemble of geological, hydrological, and botanical features of a specific area.[12]

At the heart of this study lies the concept of the desert, understood expansively and medievally as any wild place, even a well-watered one.[13] The early Christian phenomenon of the ascetic’s retreat into the Egyptian desert had a pervasive impact on western monasticism. Local interest in the example of the Desert Fathers is evident early on in the writings of the ninth-century abbot Saint Benedict of Aniane, Guilhem’s spiritual mentor; these in turn provided a foundation for invoking the desert in Gellone.[14] Embedded in the monastery’s very name, the importance of the wild setting to Saint-Guilhem’s history and identity cannot be overstated. The Vita Sancti Willelmi, the life of the founder composed at the monastery ca. 1125, celebrates Guilhem’s discovery of the remote valley of Gellone, lauding the site for the possibilities of ascetic isolation and self-denial that it offers.[15] This text “naturalizes” (to use the language of James Goehring) the local landscape of the Gellone valley to conform to the mythical deserts of the first Christian ascetics.[16] At the same time, the Vita applauds Guilhem’s initiatives, together with those of the community he gathers in the valley, to make the desert disappear through building and planting. The seeming contradiction of both endorsing and effacing the wilderness was also present in the earliest narratives of Christian asceticism.[17] It soon became the central paradox of much cenobitic monasticism, in which the desire to retreat from the world inevitably led to a re-formation, if on a smaller scale, of the very world the monks sought to reject, through strategies such as the expansion and development of monastic patrimony and recourse to lay labor. Ellen F. Arnold has explored this phenomenon extensively in her research on the Belgian Ardennes, and I am indebted to her work demonstrating the important role that hagiography played in smoothing over this unevenness in perspective.[18] In line with this work, my examination of the representations of water at Saint-Guilhem seeks to lay bare the monks’ ambivalent perspectives on their local landscape.

This essay is divided into several short sections that explore the different ways in which the undulating supports served as conduits of monastic thought, proposing a number of different water stories that converge at the monument like tributaries to a river. The first section focuses on the cloister itself, providing a brief overview of its salient features and its chronology before more fully introducing the undulating supports and considering their formal origins. The second interprets the supports with respect to biblical and sacramental imagery. The following sections expand spatially and disciplinarily from this discussion, gathering instances of medieval encounters with water in Saint-Guilhem that resonate with the element’s sculpted presence in the cloister. Taken together, these discussions demonstrate the non-human world’s infiltration of monastic spirituality. The essay concludes with a reflection on the monks’ infrastructural interventions in the local landscape that ran counter to the community’s myth of desert asceticism, emblematized by an unusual representation of a water-powered gristmill on an abbot’s tomb. Throughout, the tensions between human and hydroscape, water and stone, and temptation and salvation resonate.

Waves: The Sculpted Waters of the Saint-Guilhem Cloister

Initially, the abbey of Saint-Guilhem was known by the local name for the valley, Gellone, said to be derived from agellus, or little field.[19] It is only over time that it came to be known by the name of its founder, Guilhem, a warrior nobleman who underwent a spiritual conversion in his later years. In 804, under the mentorship of Saint Benedict of Aniane, Guilhem founded the monastery to which he retired in 806. He died a monk in 812.[20] Though little concrete information survives from the first two centuries of its existence, Guilhem’s foundation grew and prospered. Sometime during this period, Guilhem himself was canonized.[21] In the eleventh century, the existing Carolingian church was rebuilt in the Romanesque style and Guilhem’s remains were given prominence within it.[22] About this time, pilgrims traveling the Via Tolosana to Santiago de Compostela increasingly stopped in Gellone to venerate not only the saint’s shrine, but also a relic of the True Cross that Guilhem is said to have brought to the monastery as a gift from his cousin, Charlemagne.[23]

As work on the church wrapped up in the later eleventh century, the monks turned their attention to developing the communal core of the abbey complex, the cloister. The first phase of construction, which saw the completion of the north and west galleries and a small section of the east, spanned the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries. After a decades-long pause, a second phase dating to the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries expanded the cloister by adding south and east galleries to the ground level, as well as an upper level over the existing north and west galleries. Finally, the upper-level galleries of the south and east aisles were completed in a third phase dating to the fourteenth century.[24]

Fig. 4. The cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert today, view of the northwest corner (Photo: author).

The cloister no longer survives intact: only the ground-level north and west galleries, and a small section of the east gallery (dating from phase one), remain in situ (Fig. 4). The site’s post-medieval history saw the monument’s fragmentation and dispersal. In 1568, Huguenots entered the abbey and committed acts of iconoclasm, the effects of which are readily visible on many a surviving figural sculpture. The arrival of a Maurist congregation in the seventeenth century brought about the cloister’s repair and restoration, but this period of renewal was short-lived. The last monks left Saint-Guilhem in 1783, and the property’s subsequent privatization placed the cloister at the mercy of a succession of owners, including a mason who “quarried” the monument until 1847.[25] Today, sculptures are divided between the abbey museum in Saint-Guilhem, the Musée Languedocien in Montpellier, and The Met Cloisters in New York.[26]

Based on stylistic criteria combining late Romanesque and incipient Gothic forms, most of the cloister’s surviving sculptures date from the second phase of the late twelfth through early thirteenth centuries. There also exists documentary evidence to corroborate the work’s completion in this time frame. Notably, a charter of March 8, 1205 records the presence of some twenty men in “the new cloister of Saint-Guilhem,” indicating that at least some additional portion, new in comparison with the existing portions of the eleventh and early twelfth century, or phase one, was completed by this date.[27]

Fig. 5. An acanthus-based capital from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now at The Met Cloisters.

The sculptures of the cloister’s second phase are the most elaborate and inventive of the entire ensemble. They include many figurative and narrative sculptures, such as the remains of an impressive group of pier reliefs depicting Christ and the Apostles divided today between Saint-Guilhem and Montpellier. Most, however, depict forms inspired by the non-human world. Vegetation predominates, and in particular the acanthus plant (Fig. 5). A mainstay of Romanesque sculpture, the acanthus was, of course, part of the legacy of Greco-Roman antiquity. Based in the Mediterranean, the Saint-Guilhem cloister’s sculptors had particularly easy access to ancient art and architecture, so it comes as no surprise that they emulated these models. In this, their work relates to that of other famously classicizing Romanesque monuments in the vicinity, including the cloisters of Saint-Trophime in Arles and the cathedral of Aix-en-Provence, as well as the west façade of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard, where the Saint-Guilhem sculptors are believed to have worked beforehand.[28] Yet while the sculptors of these monuments took serious inspiration from the art of the past, their work is anything but derivative. While most surviving examples mimic the Corinthian capital’s upturned bell shape, and the familiar ingredients of acanthus leaves, volutes, and fleurons are principally used, only a few examples are compositionally faithful to the ancient model. On some, the fleshy acanthus leaves grow upward from the astragal, while on others, the leaves dangle from upper corners; these might stand separately in regimented rows or overlap softly. On other examples, the leaves swirl hypnotically in the manner of an ample acanthus scroll, their floral offshoots gracefully curving in rhythmic harmony. At Saint-Guilhem, the renditions of the Corinthian capital often have been described as variations on a theme, full of idiosyncratic details such as the use of the drill to create lacy surfaces (Fig. 6).[29]

Fig. 6. An acanthus-based capital from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now at The Met Cloisters.

Fig. 7. An abacus carved with hop vines and masks from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now at The Met Cloisters.

The cloister is not, however, merely an exercise in remixing the Corinthian capital. Though in lesser numbers, other kinds of plants are represented, such as hops (Fig. 7) and perhaps bindweed (Smilax). These carvings form part of a sub-group of sculptures executed with a thoughtful naturalism that suggests their later date, in line with new, thirteenth-century Gothic currents in southeastern France.[30] In my view, certain stylistic consistencies—for example, the articulation of eyes and hair among the figural forms—suggests not a wholesale change of workshop, but perhaps evidence of new membership or interest in a new way of doing things. Whatever the precise date of the gothicizing sculptures, their introduction in the cloister seems to herald the arrival of “Gothic naturalism” in the Hérault.[31] Overall, the cloister’s emphasis on vegetal forms was not unusual for the time. Vegetation proliferated in these spaces in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, in part because the expansion of the Cistercian order brought a new austerity and tendency toward aniconism, although Benedictine spaces also increasingly began to embrace the vegetal.[32] Nevertheless, Saint-Guilhem’s columns, capitals, and abaci stand out from many other examples for the exceptional skill, attention to detail, and love of variety with which they were executed.

Fig. 8. A pilaster carved with an acanthus rinceau from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now at The Met Cloisters.

Fig. 9. Carved columns (center left: palm trunk pattern), capitals, and abacus from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now at The Met Cloisters. At far left: a modern copy of an original undulating support.

The care lavished upon the cloister carvings likely resulted from the collaborative work of dedicated monks of the community, eager to shape the monastery’s identity in plastic form as they did in writing, with an exceptionally skilled and inventive workshop of itinerant sculptors who knew well the ancient monuments of the region. The relationship between cenobitic and itinerant ideators was a fruitful one, as there are many innovative forms in the cloisters that suggest the confluence of both the ingenuity of professional artists and the reflective tendencies of full-time religious. The many carved supports are a case in point. While not an entirely unusual feature of the time period in itself, the sculptors seem to have taken chisels to columns with particular gusto, once more preferring vegetal forms, and those that they conjured are unusually detailed. For example, two wide pilasters are carved with acanthus scrolls unfurling down their centers, reorientations of a Corinthian frieze such as the one found on the Maison Carré of Nîmes, not so very far away from Gellone (Fig. 8). Two other columns, wonderfully detailed and easily recognizable, are carved to look like the scaly trunks of palm trees (Fig. 9). Although their regularly patterned surfaces suggest the artists replicated a stylized model already in circulation, the detailed texture, which resembles the stems of the European fan palm (Chamaerops humilis) of the Mediterranean region, relates them to the other sculptures in the cloister that depict flora more naturalistically.

Fig. 10. Undulating supports from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now in the Musée Saint-Guilhem (Photo: author).

Fig. 11. Undulating supports from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now in the Musée Saint-Guilhem (Photo: author).

Of all the many complex and notable sculptures from Saint-Guilhem, however, the undulating support might be the most remarkable (figs. 2, 10, 11). As far as I am aware, the form does not appear in any other Romanesque cloister apart from Saint-Guilhem’s. Five of these supports survive in the abbey museum, and two more at The Met Cloisters. Originally, they served as responds at corner or central piers, as they are displayed today in New York. Though their specific locations within the original cloister are unknown, Dominique Labrosse suggested in her reconstruction of the two-story monument that a pair of undulating supports feasibly could have been located at the end of each arcade in the cloister, making for an original total of eight (if used only on the lower level) to 12 pairs (if also used on the upper level).[33] Given that Romanesque monuments are rarely as uniform and consistent as we might like, not every pier needed to have featured these supports, but even so, the survival of seven indicates their significant presence.

Carved from single blocks of stone, the engaged supports are variously described as pilasters or columns and actually seem to combine both. Each pilaster-like flat backing is carved on one side with a pair of wide vertical flutes (although one example has a rinceau instead of flutes), appearing on the right or left depending on the support’s placement within the arcade. Addorsed to the pilaster is the columnar component, which undulates along a vertical axis, its wavelengths perfectly equidistant. This is squared in section, yet each of its three visible faces melds seamlessly with the next, playing the rigidity of mathematical repetition against the sense of fluidity that repeating curves impart. Six of the seven surviving examples particularly resemble each other, cresting between six and eight times, their surfaces articulated with tight vertical grooves of alternating widths that vary slightly from column to column. In contrast, the seventh example, in the abbey museum, is widely and evenly fluted, forming more relaxed waves that crest only three times on the column’s central face (Fig. 11). This last example bears the most explicit reference to classical fluted supports.

The undulating columns contrast dramatically with the flat, hard-edged pilasters and the piers to which they were engaged. Their sinuosity imparts a looseness that revolts against the received wisdom of what an architectural support should be: straight, rigid, and static. Quivering with energy from top to bottom, the supports have long captured modern viewers’ imaginations. Robert Saint-Jean and Barbara Drake Boehm have both championed the waved column as one of the great innovations of the Saint-Guilhem chantier.[34] Enthusiasm for the form is further evident in The Met Cloisters’ display, where in fact only two of the supports are medieval, and the remaining dozen are modern copies.[35]

Twisted or spiral columns frequently appear in Romanesque architecture and architectural depictions, but the undulating support is unusual. The small number of comparanda that Saint-Jean identified only serve to underscore this. Notable among them are the wavy, fluted pilasters from the tomb of Saint-Lazare in Autun, although with their strict planarity, none of these has a strong formal affinity with the Saint-Guilhem supports; they possess an indisassociably architectural quality that, while appropriate to the decoration of the church-like shrine, contrasts with the Saint-Guilhem columns’ sculpturality.[36] In the end, Saint-Jean cited the zig-zagging ribs of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard’s central crypt vault as the model for the Saint-Guilhem supports, suggesting that the angular framework developed for the ribs, brought by the workshop that linked both sites, was softened into waves at Saint-Guilhem.[37]

An additional comparative example might be added to Saint-Jean’s list, although it resonates more conceptually than formally with Saint-Guilhem’s supports: the patterned central column of the fountain in Monreale Cathedral’s cloister. Articulated with tiers of nesting chevrons that frenetically mimic both waves (horizontally) and falling water (vertically), the column’s decorations further enliven an already dynamic installation by underscoring the streams of water emerging from the spouts above. In a similar vein to the Monreale fountain column, Saint-Guilhem’s undulating supports suggest rippling energy moving through a body of water even if, at first glance, their rigorously equidistant crests and troughs might seem more sinusoidal than aqueous.[38] They recall a river’s flow and/or its bending path through a landscape. While water does not fall in waves, the form’s basic shorthand for water, together with the column’s vertical orientation, suggests a vigorous cascade.

Fig. 12. St. Peter and the Miracle of the Spring, “Anastastis” Sarcophagus attributed to Constantine II, Carrara marble, fourth quarter of the fourth century, FAN.1992.2484, Musée départemental Arles antique (Photo: © Bénali R. & Roux L.).

Fig. 13. St. Peter and the Miracle of the Spring (lower left corner), multi-episode Sarcophagus, marble, second half of the fourth century, Church of Saint-Trophîme, Arles (Photo: author).

While I have not been able to identify any other Romanesque comparatives for the undulating supports, I suggest a late-antique model for the columns that similarly depicts water as an undulating column. Given the cloister sculptors’ awareness of classical carving, which clearly went beyond passing familiarity to the keen study of particular examples, the undulating supports they devised may have quoted a mode of representing streams of water among regional antique sculptures. To take one example, a late-fourth-century sarcophagus from Alyscamps now in the Musée Départemental Arles Antique depicts Saint Peter and the Miraculous Spring on one short side (Fig. 12) and the Baptism of Christ in the Jordan on the other.[39] At the center of each scene, a stream of water cuts vertically through the center of the composition from the top of the field to the bottom, appearing as a wavy, striated column. In both scenes, the water flows downward from a rounded protrusion suggesting a mass of rock at the top edge of the slab. Another example is found on the front of a sarcophagus in the nave of the church of Saint-Trophîme, Arles, that shows rows of scenes within architectural frames (Fig. 13). The image of the Miraculous Spring in the bottom left corner once again represents the spurt of water as an undulating, vertical column flowing downward from a rock cluster. Curiously, this formation is immediately juxtaposed with one of the colonettes (now largely broken off) and capitals that make up the sarcophagus’ decorative framework, perhaps suggesting a formal affinity between them. There is no way of knowing whether the Saint-Guilhem sculptors saw either of these specific images, but the fact that a handful of examples of antique sculptures depicting this form survive in the region does make it a possibility.[40]

Source: Representing Baptism, Evoking Paradise

The representation of water was as relevant for the twelfth-century monks of Saint-Guilhem as it had been for fourth-century Christians. On the late antique funerary monuments cited above, baptism is the subject of the scene in which the column of water appears. The sacrament is depicted directly in Christ’s own baptism and alluded to in the scene of the Miraculous Spring, which shows the incarcerated Peter smiting a rock that gushes the water he will use to baptize his fellow prisoners.[41] Adorning sarcophagi, these representations communicated the promise of life after death by alluding to the symbolic death necessarily preceding the rebirth of the Christian initiation rite. If indeed late antique sculptures such as these may be counted among the formal sources of inspiration for the cloister supports, then perhaps the iconographic weight of the watery columns carried over as well. While baptisms did not occur in the Saint-Guilhem cloister, this foundational sacrament nonetheless resonates with themes suggested elsewhere in this space’s decorations.

At the heart of this discussion is the fact that the cloister was also full of real, running water, and not just stone evocations. Water once freely flowed from the fountain installed reverently under its own architectural shelter in the southwest corner of the garth and pooled in a small fish pond immediately adjacent. According to an act in the Gellone Cartulary carried out circa lavatreium, the fountain was in place by 1205, making it contemporary with the second phase sculptures.[42] Sometime in the monastery’s later history, the flow of water was suppressed, the shelter was dismantled, and now only fragments of the carved stone fountain survive in various locations, while the reservoir does still exist in situ.[43] It is not known how the fountain made it out of the cloister, but according to tradition, it was reconstructed in the nearby town of Saint-Jean-de-Fos, where it stood until its dismantling in 1830. The traveler and artist Jean-Marie Amelin had described the still in situ fountain briefly in his 1827 Guide du voyageur dans le département de l’Hérault as having a type of “lantern” ornamented with a frieze of masks and acanthus.[44] A few years later, another artist, Jean-Joseph Bonaventure Laurens, presumably working with the verbal description, created an image of the fountain’s presumed original appearance.[45] Given the number of interventions on the fountain that occurred between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries, it is best to take Laurens’ image with a grain of salt, but fragments of the curious “lantern” do still survive at the abbey.[46] The form consisted of a limestone drum pierced with six slender, arched windows, each articulated by a simple molding. The design recalls the relief-carved arcades encircling other Romanesque fountain basins, although the “lantern” was elevated, its openings framing the spouts that would splash water into a catch basin below.[47]

While the fountain’s overall appearance remains conjectural despite these later testimonies, the “lantern” provides an anchor for its iconographic interpretation.[48] Its open, circular form recalls the ancient, centrally-planned tholos, originally associated with funerary monuments and repurposed in late antiquity as an architectural frame for the sacrament of baptism. Perhaps, then, the form references the shapes of early Christian baptisteries. More relevant to Saint-Guilhem, a monastery founded at the beginning of the ninth century by a man with direct ties to the Carolingian court, might be the potent image of the fons vitae found in this era’s Gospel illumination, represented among the prefatory images of the Godescalc (781-83) and Soissons (ca. 810) Gospels.[49] Each manuscript depicts a centrally-planned structure of eight columns supporting an architrave and conical roof that shelters a basin; birds and deer fill the space around the structures. Robert Saint-Jean suggested the cloister’s undulating supports referenced the fons vitae, and this may be so, but a link can first be forged more directly with the cloister’s actual fountain, which bears a strong resemblance to the structures depicted in the Gospel books.[50] In addition to the “lantern’s” round form, the play of light and dark created by its pierced arches even recalls the contrast between the closer and farther columns of the Godescalc fountain.

The fons vitae motif had conceptual roots in the Edenic spring, which merged with the Psalms’ “fountain of life”; the architectural forms of baptistery and baptismal font became associated with these scriptural references.[51] The waters of Eden also served as the basis for Christian conceptions of the verdant Paradise to be inhabited by the elect at the end of time. Evoking terrestrial Eden and celestial Paradise and alluding to baptism, which washes away the original sin that marked the closing of Eden and starts the Christian soul on the path to salvation and thus to Paradise, the fons vitae brings together the complementary views of baptism as a vehicle of death and as a promise of rebirth.[52] While images of the fons vitae often incorporate the number eight (eight columns, eight sides of the basin), strongly associated with baptism, the number six—the number of openings in the Saint-Guilhem “lantern”—could also symbolize the sacrament.[53]

The evocation of Paradise in the Saint-Guilhem cloister fountain coincided with an increasing twelfth-century interest in describing claustration as accession to a kind of Paradise on earth.[54] Explored extensively in spiritual writing, this conceptualization invited description of the actual, architectural cloister as a paradisiacal space.[55] A sermon of Peter Damian, for example, specifically describes the architectural cloister as Paradise, filled with the meadows of scripture and the fruitful trees of the choirs of saints.[56] Honorius Augustodunensis compared the claustrum (understood here as the monastic enclosure writ large and not simply the architectural cloister) and its constituent parts to a Paradise garden in his Gemma Animae, ultimately arguing the space symbolized the kingdom of Heaven. As part of this reading, he likened the cloister fountain to the baptismal font. The reference to baptism accompanied his assertion that eventually the saved will be separated from the damned and brought to Paradise, just as those who take monastic vows are separated from everyone else in earthly time and, by implication, enter an earthly claustral Paradise.[57] Later, William Durandus identified the architectural cloister as a symbol of the Paradise of the elect.[58]

The fountain’s baptismal and paradisiacal dimensions express the hope of eternal life after death, and the undulating supports underscore this theme.[59] The wavy columns’ formal resemblance to the springs and rivers in late antique depictions of the Baptism of Christ and Saint Peter and the Miraculous Spring suggests that the undulating supports symbolized baptismal waters just as the cloister fountain’s actual waters did. Either way, the presence of water in both fountain and pier supports (could the undulating columns originally have been placed around the fountain?) signified redemption and accession to Paradise on both a temporal level (becoming a monk and entering the claustrum) and an eschatological level (dying in a state of grace and going to Heaven).

Other sculptures in the cloister support a broader reading of the claustral space as a paradisiacal one. Specific forms, such as the palm trunk columns and a fragmentary capital of the Crucifixion now in the Musée Languedocien that depicts the cross as lignum vitae, make clear allusions to the tree of life originating in Eden and found again in the heavenly Paradise.[60] Overall, the aggregate of so many vegetal carvings suggests the scriptural ideal of a healthy and well-watered Paradise garden, understood elastically in terms of both the prelapsarian Garden of Eden and the celestial destination of the saved.[61]

Flow: Rocks and River

The undulating columns’ evocations of the rivers of Eden and the celestial Paradise, carried forward by streams of baptismal waters, portray the history of salvation as a current flowing from the earliest moments of creation to the end of time. The intangible rivers of scripture were not, however, the only bodies of water informing the undulating supports’ creation and interpretation. In this section, the regional hydroscape enters the discussion as a source of inspiration for sculptors and monks alike. Although some authors have suggested a connection, to my knowledge the relationship between the supports and the waters of the Gellone valley and its environs has never been explored in-depth.[62] Yet the sheer plenitude of flowing water among local crags and cliffs suggests it held great potential to inspire the sculpted streams that similarly coursed through the cloister arcades. That said, however, the fact of flowing water in Gellone is only one possible dimension of the sculptural response to the landscape. The relationship between water and stone is also worthy of consideration. After all, stone is the material in which water was represented in the cloister, and this solid substance opposes shape-shifing liquid in every possible way.[63] Leading up to this surprising elemental transformation under the sculptor’s chisel, there were many opportunities for the sculptures’ creators to observe the conjunction of water and stone in the landscape and consider the ways in which they worked upon each other. It thus will be helpful at this point to step back and consider the natural setting in greater breadth.

Fig. 14. The “Bout du Monde” (Photo: author).

The Gellone valley is located at the southern edge of the Massif Central in a transitional zone between the highlands and the coast. It forms part of a riverine hydroscape centered upon the Hérault, the area’s most significant body of fresh water.[64] Sited upriver, Gellone lies among the gorges of the Hérault, a zone characterized by plunging cliffs, jagged ledges, and rushing water. At the far western end of the valley, known evocatively as the Bout du Monde, lies the Causse du Larzac, a limestone plateau edged by the Séranne massif (Fig. 14).[65] The valley’s calcareous substrate supports a diverse array of local vegetation characterized as maquis and garrigue—tall and low scrub, respectively, featuring trees like holm oak and Salzmann pine, and aromatic shrubs including junipers, sage, and thyme.[66] The River Verdus rises from below the Séranne’s distinctive peaks. Its source is a spring in the Cirque de l’Infernet, at the base of the Bout du Monde, but runoff from the surrounding high places additionally feeds the river along its course. It flows eastward to join the Hérault.[67]

Fig. 15. Promontory at the north end of the Gellone valley (Photo: author).

From a deep time perspective, the Verdus made the Gellone valley. Over millions of years, its abrasive action excavated a wide trench into the limestone of the massif, carving dramatic promontories, slicing escarpments, and shaping slopes that delimit the valley to the north, south, and west. While the protective natural walls of the valley surely were a significant draw (Fig. 15), the Verdus was also one of the main reasons behind the choice of Gellone as a site for human settlement.[68] It may not seem so today, since part of the river’s supply is now diverted at the source for the town’s needs, but the Verdus’ flow is generous.[69] Carbon 14 dating of plant matter trapped in the valley’s tufa deposits indicates that by the early Middle Ages, and at least up to the thirteenth century, the river’s debit was regular and stable, a favorable condition of settlement.[70]

In addition to the river’s visible currents, there are also many and unseen flows of groundwater actively shaping Gellone; the calcareous massifs surrounding the valley are “véritables châteaux d’eaux” enchambered with half-hidden grottoes and sink holes.[71] The Saint-Guilhem monks surely were aware of this aspect of the site. Medieval people understood that water makes progress through stony underground chambers; Isidore of Seville wrote that water “is percolated through certain hidden openings in the earth, and runs back again to the source of springs and fountains.”[72] The local masterpiece of underground aquatic action is a massive cavern just to the south: La Grotte de Clamouse, named for the clamor of water periodically gushing from its outlet above the Hérault.[73] There is no medieval text describing people’s experiences of this spot on the river, but they could not have missed its dramatic expulsions of water and the thunderous sounds accompanying them. Although observed every day in the Hérault’s downstream progress, water’s supreme power would have been cast in sharp relief when the Clamouse was raging, prompting periodic recognition of this element’s force every time it burst out in a single, concentrated stream from the living rock.[74]

The particular features of the local hydroscape make an appearance in the Moniage Guillaume, a chanson de geste recounting Guilhem’s retirement that was composed sometime in the eleventh century and written down by the later twelfth.[75] The poem describes Guilhem’s initial exploration of the valley, offering a strikingly vivid—and accurate—evocation of the site as rocky, steeply sloped, pockmarked with caverns, and shot through with water. The pairing of waters and caves in a single line of the poem is particularly poignant given the two features’ inextricable relationship in the landscape.[76] Their juxtaposition makes it easy to imagine the one infiltrating the other, the slippery porosity of stone making it all the more difficult for the saint, portrayed in this story as a lone hermit, to navigate the valley, with sudden damp openings in the rock making progress perilous.

The first settlers of the valley did indeed have to tread carefully as they learned the terrain and searched for solid ground on which to build. One particular tufa dome, located about two thirds of the way from the Bout du Monde to the banks of the Hérault, seemed particularly promising. It was traversed by the river but offered solidity, as well as easy access to a strong, but lightweight building material; this became the site of the monastic complex.[77] The first abbey church’s crypt was cut from this surface, and the excavated material was used in building the aboveground structure. Over time, the finely-grained limestone quarried in both the valley and at other nearby sites would become the monks’ preferred building material, but locally-sourced tufa would continue to be used, especially where lighter weight was welcome, for example in the vault of the existing church.[78]

Fig. 16. View of the abbey of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert from the south, with tufa terrace covered in vegetation (Photo: author).

Given its formation through the flow of water, tufa is an intriguing material to consider with respect to the Saint-Guilhem cloister carvings. It is created by the progressive buildup of calcareous deposits left by flowing water. This is an additive process, as opposed to the subtractive work of erosion. Also in contrast to the riverine abrasion that created the valley over eons, the tufa deposits are more recent developments, only some several thousand years old.[79] While the monks of Gellone may not have thought about the relative ages of the valley’s geology, they would have observed the erosive power of water against stone. We can once again turn to Isidore for a hint of how medieval people thought about this material, as he wrote that tufa “is crumbled by heat and sea air, and weathered by rain.”[80] Presumably, the Gellone monks also could have recognized the tufa mounds to be the slow work of water.[81] In general, ancient and medieval ideas about petrogenesis did emphasize elemental combination, namely water and earth, and the relative aqueousness of stones and metals were posited, although the extent to which this idea would have been disseminated before the thirteenth-century De mineralibus of Albertus Magnus also remains a question.[82] Yet the continued intimate, dynamic association of river and tufa observable in the landscape, as the one flowed over the other, would have put the monks in a position to consider if not the causal effect between the one and the other, then certainly the alliance that the two elements seem to forge. Tufa’s porosity encourages water’s infiltration of its many small and sometimes interconnecting cavities, prompting the two elements to work collaboratively to sustain plant life. Today, the broad base on which the entire monastery rests is only partly visible along the east terrace, over which the Verdus flows, because a thick mat of green grows over the mineral surface, concealing it (Fig. 16). This is not a recent phenomenon, but rather a typical side effect of porous tufa’s water-retaining nature.[83] To that end, it is also important to keep in mind that the garth of the cloister itself rested on a tufa substrate, and that any plants growing in this space would have been those suited to growing on such a surface, even with the introduction of topsoil. The interaction of stone, water, and vegetation in and around the monastery provided fertile ground for imagining a rendering of water out of stone through an artificial sculptural process, complementary to so many vegetal carvings.

Fig. 17. Tufa arch in Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert (Photo: author).

Moreover, the physical properties of tufa could have encouraged the sculptural exploration of water in stone. Many a cross section of cut tufa reveals an undulating pattern of striations not only evidential of the flow of water, but also evocative of water, employing the basic visual language of waves (Fig. 17). The tightly-grooved, undulating columns in the cloister echo these patterns in the stone as much as they do the surface of water. The ability of richly veined marbles to evoke water is well attested in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Though a poorer material, there is every reason to think that undulating patterns in tufa could prompt a similar interpretation.[84] While the Saint-Guilhem columns themselves are not carved of tufa, which is not a desirable material for sculpting, the stone’s use in the abbey and the town’s constructions, along with its “living” presence in the ground, offered ample opportunity for the cloister’s creators to contemplate its complex forms and these forms’ ability to recall the river so closely associated with them. It may have proved irresistible to find a way to sculpt them, with the resulting undulating columns creating a bond between abbey and valley.

The interplay of water and stone observed in Gellone also has iconographic implications for the cloister’s undulating supports. I have already noted the wavy columns’ formal resemblance to the stream issuing from the stone in depictions of the Miraculous Spring on late antique sarcophagi. This story’s focus upon the petrogenesis of water—Peter strikes a rock, eliciting a source that enables him to baptize his captors—feels far more immediate when considered in the midst of a terrain in which water spills over limestone ledges, pools in pockets of tufa, and issues suddenly forth from underground caves. In the Saint-Guilhem cloister, elemental phenomena converge with miraculous moments; the former help the latter to feel more real, relevant, and continually possible in this site. The collision of the elemental and the miraculous is further encountered in the valley through the hagiography of Saint Guilhem, the subject of the next section.

Tears: Irrigating the Desert

It is difficult to venture far into the Gellone hydroscape with the medieval monks because they left no records of their direct, frank impressions of it. Nonetheless, idealized portrayals in texts like the Moniage Guillaume can provide some insight into medieval people’s perspectives on the land.[85] Before returning to the Moniage, the legendary text, I will consider the hagiographic account of Guilhem’s life, the Vita Sancti Willelmi, committed to parchment by an anonymous monk or monks of Gellone around 1125.[86] Just as the Moniage follows the conventions of the chanson de geste genre, hagiographic convention governs the Vita, but a sense of site-specific connection between monastery and valley also pervades it, implicating the founder as the hinge between institution and site and establishing Gellone as a locus sanctus.

The Vita portrays Guilhem as a pious nobleman and warrior of the faith who, despite the good life he leads, desires to do more for God. He decides to build a house of worship in a remote and undeveloped place: a desert (desertus or heremum, a wild place).[87] Led by an angel, he encounters a place of lofty headlands, steep slopes, and narrow, rocky passes that eventually opens onto a small plain surrounded by tall escarpments, shaded by trees, and watered by a stream (the Verdus). In this land, Guilhem recognizes the desert he sought and promptly builds a monastery there. Gradually, the rough terrain gives way to foundations, walls, roofs, and, last but not least, altars consecrated in honor of the Savior, Mary, and the saints. Having begun this work, Guilhem returns to Charlemagne’s court—only to yearn for his desert foundation, which he describes as his “well-loved place of solitude.” When he is finally able to return to Gellone, he joins the brothers in removing unfruitful trees and planting vineyards, orchards, and gardens. He also improves access to the valley, building a road along the Hérault.[88]

The Vita Sancti Willelmi portrays the Gellone landscape as a wilderness of rocky uplands that resonates with the actual terrain. Of course, the Vita uses stock forms found in many a desert hagiography, and as such their ability to carry weight with respect to historical reality may be called into question—indeed, there are many ways in which the text is so typical of other monastic hagiographies that it might seem impossible to glean anything notable from it at all. Yet it is bespoke in its particular selection of topoi and motifs, and the authors’ choices can in themselves be revealing of their own experiences and perspectives. In the end, it is not a coincidence that the images of stones and scrub in the Vita rhyme with the actual landscape of gorges and garrigues, and its description of the land is no less apt for being conventional.[89]

A hagiographic topos, the monastic retreat to the wilderness, unfolds in the Vita. This was a popular theme with a long history, modeled on ancient accounts of Judeo-Christian desert heroes from Elijah to John the Baptist to Anthony Abbot.[90] In such accounts, the desert is portrayed as unsettled, uncultivated, and inhospitable, a locus horribilis opposed to the classical locus amoenus of a pleasant, fruitful, and convivial green space.[91] Yet, if the desert is a terrible and dangerous place, full of unruly terrain, ferocious animals, and even demons, the ascetic’s flight into it is nonetheless a boon for his salvation. It gives the would-be devotee a chance to lead a life of true separation from the corruption and comforts of the world, offering all manner of trials that have potential to bring spiritual revelation and ultimately redemption.[92] The desert is a supernatural place where one will surely encounter demons, but also angels; it is, in the end, a site of theopany for those virtuous ascetics who seek it out.[93] In this respect, and following Jerome, the experience of a desert-dwelling saint such as Paul the Hermit had the potential to reframe the desert as a flowering Paradise, a notion later explored further by Peter Damian.[94] The locus horribilis of the desert thus transforms into a locus amoenus, which, in contrast to its classical literary portrayal as a place of gathering, becomes a site of solitude and reflection—the act of enjoyment itself having been reinterpreted in the late antique and medieval periods not as a frivolous engagement with the fleeting pleasures of earthly existence but as a dedicated focus on the joys of the world to come. To that end, in Late Antique saints’ lives, where the desert is still a challenging wilderness full of loose rocks, steep slopes, and desolate patches, there are also certain comforts or even beauties of the kind essential to the classical topos of the locus amoenus, like trees and springs, which enable the ascetic subjects to thrive. In particular, the desert-friendly palm is the tree of choice in the lives of the early hermit saints, offering shade and fruit.[95] With its palm trunk columns, the Saint-Guilhem cloister seems to make a bid for its consideration as a desert locus amoenus such as it was interpreted in the time of the Desert Fathers—a setting compatible with the monastic desire for solitude and reflection, an earthly Paradise.

Monastic desert dwelling was just as desirable in reality as it was in hagiography because (at least in theory) it challenged monks to fulfill their vocation at the highest level. The appreciation of the desert in Guilhem’s Vita, which arises both because and in spite of its many challenges, was likely mirrored by the monks’ own sense of satisfaction in their rocky valley, a perspective underscored in Gellone’s other name, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert.[96] The name demonstrates the wilderness’ centrality to the house’s origins, as well as to subsequent monks’ continued willingness to live there and accept its challenges. Valorizing the desert as the Vita does, the name may have signaled something of a monastic badge of honor, a hard-won marker of ascetic identity made possible by Guilhem himself.[97] Whatever the monks actually thought about the Gellone landscape, they knew to revere and celebrate its more difficult features, since these were, hagiographically speaking, the quintessential qualities of the desert.

There was an additional reason for the monks to celebrate their desert home, this one concerning Gellone’s relationship with the nearby monastery founded by Saint Benedict of Aniane, Guilhem’s erstwhile spiritual mentor. In its early days, Gellone seems to have been considered a dependent of Aniane.[98] The eleventh century, however, found the Gellone monks distancing themselves from the alleged mother house, promulgating an alternate history that stressed their own house’s independence from the start. Enabled by a fortuitous archive fire, they forged documents to that effect. As Aniane was not willing to accept the loss, there began what has been described as a war of charters, with each house refining its own version of the story via diplomatics.[99] The Vita Sancti Willelmi also does its part to portray the monastery as a singular foundation entirely separate from Aniane.[100] Among other strategies, the Vita authors fed competition between Saint-Guilhem and Aniane by underscoring the Gellone Valley’s desert status. According to the Gellone monks, while Guilhem took on the wild, his mentor did no such thing, instead founding his monastery in a decidedly unchallenging alluvial plain, the kind of easygoing landscape that provided little opportunity to test one’s spiritual fortitude. As Jean Meyers has demonstrated, in emphasizing the desert setting, the authors of Guilhem’s Vita modeled passages of their text on the life of the fourth-century hermit Saint Hilarion, strategically selecting a Desert Father to convey Gellone’s superiority over Aniane.[101] From this perspective, Gellone’s wildness, more conducive to serious asceticism and perhaps just a bit more worthy of monastic occupation as a result, contributed to its inherent supremacy, which became an argument in favor of its independence. In presenting this perspective, the Vita authors made a bid for Gellone’s greater authenticity qua monastery, the medieval monastic equivalent of demonstrating street credibility. Ironically, their knowledge of the Desert Fathers and their absorption of the ethos of wilderness asceticism may have been enabled by the many texts on these subjects initially amassed at Aniane by Benedict himself in the early ninth century.[102]

Making use of the topoi of desert and locus amoenus, the authors of the Vita Sancti Willelmi sought to portray Gellone as the ideal monastery in the perfect setting. Employing their own house’s desert location as an argument in favor of its superiority, and by extension, its independence, they were able to develop further Guilhem’s role vis-à-vis the site. They portrayed the saint himself as possessing a powerful physical connection to the monastery and to the valley, involving him bodily and fluidly in their care. Water plays a central role in expressing this relationship, and the textual imagery is so evocative of the love and attention that went into Guilhem’s support of the monastic community that it becomes possible to read his presence in the undulating stone supports of the cloister. This imagery appears in the context of Guilhem’s return to Gellone after an interval at the Carolingian court. In locating the valley again, he is once more guided by an angel, suggesting that access to Gellone is accorded to the virtuous by means of divine intervention. There, Guilhem is moved to impromptu adoration, calling upon God to bless, sanctify, and continually visit the place, suggesting the sacrality of the valley itself as a place of worship, as a locus sanctus. Next, intercepted by his brethren, he is led in procession to the church, where he places Charlemagne’s great gift, the relic of the True Cross, in addition to other saintly remains and sumptuous treasures, on the altar of the Savior.[103] Then, he prostrates himself on the ground and arranges his body in the manner of a crucifixion for two hours. He sends prayers to heaven while his tears water the earth and fall onto the paved floor.[104]

The image of the saint crying copiously enough to water the earth is a powerful one, although weeping in the monastery is not unusual; a sermon of Peter Damian, for example, describes the cloister garth as a Paradise kept green by tears of compunction.[105] In the context of the Vita Sancti Willelmi, Guilhem’s lachrymose irrigation relates to a number of aspects of his story. His tears flow as he at last commits to enter the monastery as a monk; they accompany his complete spiritual conversion in a mode that has, following Piroska Nagy, baptismal, sacrificial, and penitential dimensions.[106] The saint’s weeping also places him in league with his mentor Benedict of Aniane, who, according to his biographer Ardo, cried daily and once put out a fire with his tears. Ardo links Benedict’s propensity to cry to that of his role models, the Desert Fathers, for whom weeping was an integral aspect of their asceticism and a manifestation of God’s grace. For all of these sainted figures, crying constituted an act of purification in the face of bodily temptation, a corporeal practice leading to spiritual transcendence.[107]

Guilhem’s tears also contribute directly to the work of cultivation in which he himself participates, although this extraordinary act goes well beyond the mundane activity of planting trees with the brothers. His tears refresh and bless the valley, signaling the catalytic presence of his body and its effluence on the land. Overall, the tears falling on both earth and pavement express Guilhem’s dedication to caring for both the monastery he built and the land upon which it was founded.[108] In addition to the watery verbs describing his tears, his prayers also pour to heaven, an action presented in near parity with his tears spilling onto the pavement (“fundit” for tears and “infundit” for prayers).[109] The simultaneous acts of pouring sited in Guilhem’s body, modes of praying and crying, depict a continuous flow from earth to heaven and back again, with Guilhem the conduit. The aqueous language further affirms Guilhem’s potency as intercessor by invoking water’s unparalleled ability to move quickly, forcefully, and efficiently. The tears are no longer droplets, the prayers no longer words; instead, they are steady, sustaining streams, as strong and supportive as stone columns, and they serve to confer the sanctification to the valley that Guilhem himself prayed for. Flowing as they do in a wilderness, Guilhem’s literal and metaphorical effluences are evoked by the watery stone sculptures in the cloister.

With the transformative effects of Guilhem’s tears, Gellone becomes what Ellen Arnold has termed a “landscape of conversion,” in which the terrain is Christianized through the purifying acts of a founder saint.[110] In some respects, the episode recalls an infrastructural miracle of another monastic founder saint, Remaclus of Stablo, who exorcised a demon-infested, dried-up spring previously used by pagans by fitting a lead pipe into it, miraculously enabling water to flow once more.[111] Remaclus’ actions constitute a kind of baptism of the site, Christianizing the formerly pagan environs by reviving the spring. Falling onto the earth, Guilhem’s tears perform a similar baptism of the land, following up on his earlier call to God to bless the valley. In parallel, Guilhem’s tears also wash the abbey’s pavement, and if we can continue to see them as analogous with blessed water, then they re-consecrate the building he constructed.[112]

Abyss: Drowing the Devil

Alhough Guilhem’s tears are sanctifying, they also perform the maintenance work of watering and washing. These acts bring to the fore an important theme of the Vita Sancti Willelmi (among many other monastic hagiographies): the taming of the wilderness.[113] It must be conceded that just as the text celebrates wilderness, it also condones its effacement, as the monastic settlement described therein brings built environment, agricultural exploitation, and infrastructural development. Guilhem searches for a desert, but once there, he and his brethren do everything they can to cultivate it. In fact, the Vita devotes considerably more words to highlighting this work than it does to describing the desert setting. In so doing, it offers up what Peter Brown has called the myth of the desert, portrayed as a place separate from the world, but in fact very much part of it.[114] The Moniage Guillaume also chronicles the former warrior’s quest to become a monk (a hermit, in this version), and his eradication of the wilderness is just as much a part of the story. Although it appears not to have been written down until the second half of the twelfth century, the Moniage actually predates the written form of the Vita Sancti Willelmi (ca. 1125), and there is clear evidence that the monks were familiar with the epic poem when they composed their hagiography.[115] Of course, as a chanson de geste, an adventure tale, Guilhem’s story is sensationalized as it never is in the Vita, crammed with episodes ranging from the violent to the silly (sometimes both at once). Like the chanson, however, the hagiography gives the impression that the valley is a difficult landscape to both locate and live in.

Fig. 18. Detail showing snake, undulating support from the cloister of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now in the Musée Saint-Guilhem (Photo: author).

The descriptions of Gellone in the Moniage, briefly discussed above, are very evocative of, and even fairly accurate to the actual setting. The main point of the text, however, is not to dispassionately describe the valley, but to use its frightening features to set the mood to “thrill” and heighten the drama of the unfolding adventure. Of Gellone’s varied terrain, the poem identifies fear as the only appropriate response, although brave Guilhem’s warrior instincts take over, and he feels no such trepidation.[116] Another of the valley’s features that is explicitly designated as scary is the site’s infestation by serpents, lizards, and toads. Even Guilhem, nonplussed by the site’s overall wildness, prays for help with the pests. God responds by drowning them in the river.[117] One of the undulating supports in the cloister seems to respond to this part of the story, the only surviving example on which a bold rinceau decorates the backing instead of a pair of flutes (Fig. 18). At the lower edge of the waved component, adjacent to the leaf pattern, is a little curling snake, seemingly caught in the process of being expelled from Gellone, lingering at the edge of the “water,” represented by the undulations, and the “land” suggested by the rinceau.[118] While one tiny snake does not an infestation make, this sly carving especially seems to refer to the chanson, which, as a product of the eleventh century, was well known to all by the time of the cloister’s creation.

The river, incidentally, is no less fearsome, and not only as a potent form of pest control. The finale of the Moniage finds Guilhem attempting to build a bridge over a waterfall, joining the two high cliffs on either side with a sturdy stone construction.[119] The devil intervenes in this project, however, continually thwarting Guilhem’s work until the saint finally prays to God, who casts the devil down into the water just as he did the snakes, lizards, and toads. Even then, the river presents a new threat: churning waters caused by the devil’s wild thrashing. Filled with the corpses of foul beasts, agitated by the devil, the river’s waters become imbued with sinister tendencies, but Guilhem prevails and completes the bridge’s construction.[120]

Fig. 19. The Devil’s Bridge (foreground), Saint-Jean-de-Fos (Photo: author).

The rough waters in the story have a real-life analogue: this section of the Hérault has long been known as the Gouffre Noir, the black chasm, which squeezes through a narrow point in the river formed by a stone ledge jutting from the left bank. Though fanciful in its depiction of both the river and the bridge, this episode of the Moniage becomes the mythical origin story for the real medieval bridge that still spans the Gouffre Noir: the so-called Devil’s Bridge, which Gellone’s monks built in rare collaboration with the brothers of Aniane in the 1030s (Fig. 19). The chosen location had a long history of settlement and river crossing because the Hérault narrows there, squeezing past a rocky ledge extending from the left bank. As the legend indicates, the steep cliffs on either side are formidable, and in the past the river’s periodic flooding made crossing treacherous.[121] Although built up at successive points in its long life, the bridge is still supported by its two massive, original Romanesque arches, which meet at a central pier resting on the stone outcrop below. In addition, the bridge was outfitted at each of its furthest ends with a smaller arched opening, and the central pier features wedge-shaped buttresses both up- and downstream. Functionally, these refinements are meant to ease the flow of water during floods.[122] These features thus also remind of the river’s more nefarious behavior, able to turn on the region’s inhabitants despite their best efforts, and perhaps linked to the work of the devil. Considering the undulating columns of the cloister in this light, as perilous flows of water, inflects them with yet another understanding as potential dangers best kept in check.

In the context of an adventure story like the Moniage, describing the desert’s dangers heightens the tension of a suspenseful tale. In hagiography, doing so provided spiritual edification. In lived experience, however, the threats that nature posed, from flood to drought, were simply something for the monks to work hard to overcome. This became especially urgent as they found themselves surrounded by a growing urban lay community that depended upon them. The monastery thus undertook large-scale projects to mitigate the site’s dangers—once again, pushing the local wilderness further and further to the valley periphery. The construction of the Devil’s Bridge is a case in point. The main impetus for it was to facilitate the increasing traffic of locals, pilgrims, and other travelers over the Hérault. Its planning and construction were comprehensive and far-sighted. The costs were divided equally between Gellone and Aniane, and both houses agreed that once the bridge was completed, there would be no toll. The continued joint monastic guardianship of the structure also protected it from lay control.[123] In addition, the two parties agreed to establish shared fishing rights within a designated stretch of the river and limit the building of paxeriae, the shallow dykes or weirs extending from the banks that modulated the river’s flow and could facilitate crossings.[124] By building the bridge and aligning on the uses of the river, Gellone and Aniane united to protect their own interests in the region. That the rivals were able to reach an accord in planning the bridge, accomplish their goal in constructing it, and continue to honor their agreements concerning it despite their sustained conflict says much about the primacy of the waterways in the greater Hérault region and the urgency of regulating them to mutual benefit. It also reveals just how much the monks were doing to change the character of the waterways and the lands around them.

Wheels: Taming the Wilderness

The Devil’s Bridge stands as a monument to cooperative monastic infrastructure for all to see, but the monks also found other ways to commemorate their large-scale interventions on the land. The documents relating to the bridge indicate that they also were involved in the construction, maintenance, and operation of hydropowered mills along the Hérault.[125] Admittedly, a complete picture of the monastery’s mill holdings in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries is lacking, but one particular example stands out for the importance the monks attached to it. This is the Roquemengarde mill in Saint-Pons-des-Mauchiens, located some 30 kilometers south of Saint-Guilhem following the meanders of the Hérault. In 1164, under Abbot Richard d’Arboras, the monastery acquired land along the banks of the river in the parish of Saint-Véran d’Usclas, a site that corresponds to the location of the Roquemengarde mill that stands today. They also gained riparian rights on the opposite shore.[126] Though the intention to build a mill is not made explicit in this document, the obtaining of rights to the opposite shore of the river would have supported the creation of a paxeria intended orient the river’s flow toward the mill.[127] The document laid the groundwork for the abbey’s construction of a mill under the leadership of either Richard d’Arboras or his successor, Bernard de Mèze.[128]

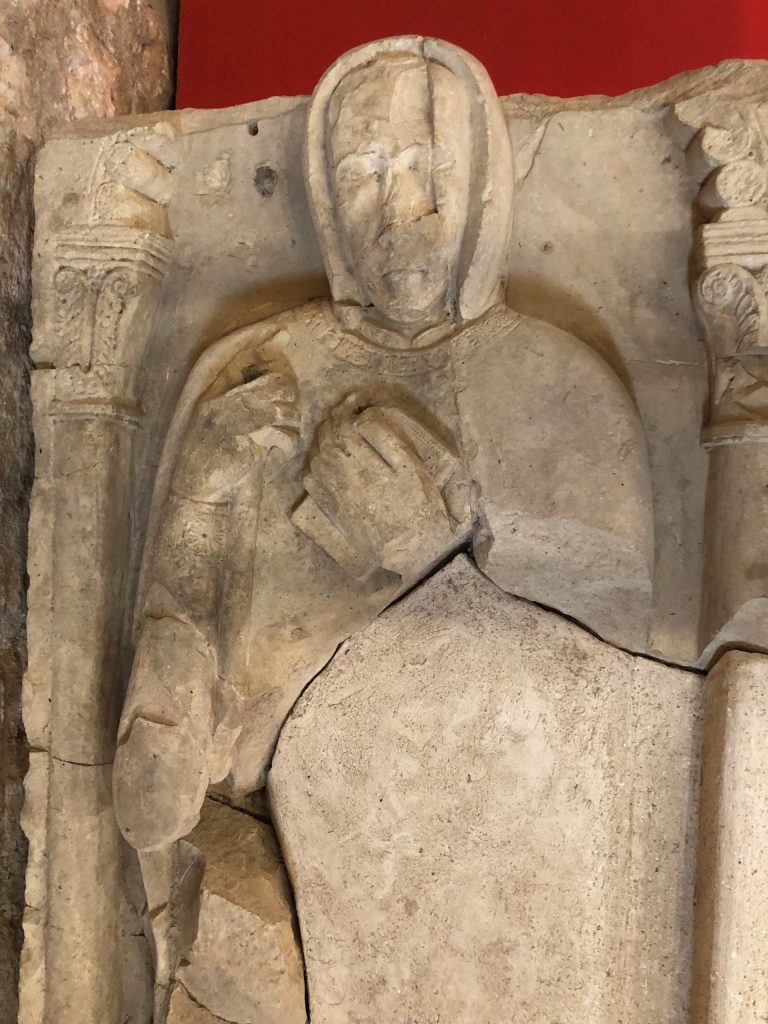

Fig. 20. Detail of the gisant, tomb of Bernard de Mèze (d. 1189) from Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now in the Musée Saint-Guilhem (Photo: author).

Fig. 21. Funerary scene, tomb of Bernard de Mèze (d. 1189) from Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now in the Musée Saint-Guilhem (Photo: author).

Fig. 22. The Roquemengarde Mill, tomb of Bernard de Mèze (d. 1189) from Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, now in the Musée Saint-Guilhem (Photo: author).

There survives no further documentary mention of the Roquemengarde mill for several centuries, but a unique sculptural record does reveal something of the mill’s significance to the monks of Saint-Guilhem at the end of the twelfth century. It is found today in the Musée Saint-Guilhem, one of several fragments of a tomb lid with full-sized sculpted effigy reconstructed at the museum’s entrance. Although broken into multiple pieces and missing a large portion of its midsection, the lid clearly displays the hooded, robed gisant of an abbot holding to his chest a prayer book and staff (probably a crozier, although the top has broken off). Slim columns topped with carved capitals flank the effigy, and an arch edged with small roundels, now mostly missing, springs from either side (Fig. 20). One of the slab’s sides was also carved in relief. The section below the effigy’s head and shoulders depicts a scene of monastic funerary rites (Fig. 21). Remarkably, below the effigy’s feet is a depiction of a hydropowered vertical mill, easily recognizable even though the building’s components are represented in a single line (Fig. 22), contrary to actual practice, in a manner similar to the representation of the vertical mill in the Hortus deliciarum of Herrad of Landsberg.[129] At center stands an impressive tower with regular masonry courses, a round-arched doorway, a double window, crenellations, and an angled buttress on its right-hand side. Two water wheels with articulated paddles, spokes, and axles flank the structure. The tomb once had an inscription, now lost, but notes compiled at the end of the seventeenth century by Jean Maignan, a monk of Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, record it in fragmentary state and identify the mill as that of Roquemengarde.[130] The name of the tomb’s occupant was already effaced by this time, but more recent studies usually attribute the tomb to Abbot Bernard de Mèze, who died in 1189.[131]

The Roquemengarde mill that still stands today is a later medieval construction with two towers, and it no longer has wheels.[132] If indeed the tomb relief depicts this mill, it represents an earlier iteration that either no longer survives or was reconstructed and expanded about a century later. Alternatively, it may represent the idea of a mill instead of a faithful portrait of a mill. That said, some extant twelfth-century mills on the Hérault, such as the Moulin de Plancameil, have a single tower and may suggest the appearance of the original Roquemengarde mill.[133] These also have a fortified character, with thick walls, crenellations, and a wedge-shaped buttress aimed upstream (as on the Pont du Diable, designed regulate the oncoming current), much like the mill depicted on the tomb.

The representation of a work of civil architecture on a monastic tomb is unusual, especially during this period, but its reference to the temporal world links it to the scene of funerary rites at the opposite end of the slab edge. The depiction evidently celebrates a major achievement for which the abbot was to be remembered, a boon not just to the community of monks but presumably also to the lay populations that the grain from the mill also would have fed. Grain would not have been a principal crop of the Gellone valley, which largely supported vines and olive trees. Instead, it would have been brought up from the alluvial plains to the south, making the location of a grist mill closer to the fields in southerly places like Roquemengarde a welcome efficiency. The image of the mill also suggests something of the magnitude of the project, which required the mobilization of resources and labor on a scale comparable to the construction of the Pont du Diable, under the abbot’s strong leadership. The celebration of a community leader who, through a major project, made work more streamlined and improved communal sustenance, would have been reason enough to commemorate the undertaking.

The sculpted mill’s defensive character, underscored by its solid masonry and crenellations, is also telling. As much as fortifying a gristmill may have had a protective purpose, given the valuable stores of grain within, it also projected the mill owner’s control of the river, the surrounding fields, and the harvest using the visual language of secular defensive architecture.[134] The tomb portrays the abbot as the feudal lord he effectively was, an impression intensified by the subtle rhyme of the beaded molding over the arched door of the sculpted mill with the circular pattern lining the arch over the effigy’s head on the lid. The correspondence of forms suggests that the abbot is meant to be understood as standing in the mill’s doorway, framed in the midst of the monumental, imposing symbol of temporal power that he shepherded into being.

Given the strong emphasis on water in the cloister, it is surprising that there is no inclusion of the element in the mill’s depiction. Despite the damage that the slab has sustained over time, the unarticulated lower edge survives more or less intact. The whole structure rests on a dry masonry platform, and the existence of water is only implied by the wheels’ presence. Imagining the wheels as turning does impart a particular vision of water; in such an imagining, the wheels lift and capture the water, channeling it temporarily before releasing it downward in a narrow stream, harnessing its power to work the grindstones. Water’s dynamism is not absent, but the apparatus contains it, effecting a total control, if fleeting, of the water itself, to the point of obliterating its actual presence. The mental image of channeled waters passing over the wheels vividly recalls the columnar undulations of the cloister supports, which do, after all, follow a strict and constrained path. As much as the supports might recall the untamed waters of the Gellone valley and its region, they also have potential to suggest these waters’ mastery by the monks through their infrastructural projects, be they hydropowered mills or irrigation canals-of which the medieval Gellone valley had many, some still surviving today.[135]

Conclusion