Mario Elías Jaroud

Recommended citation: Mario Elías Jaroud, “Reclaiming Paradise: A Queer Body in Medieval Eden,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/FNLB5170.

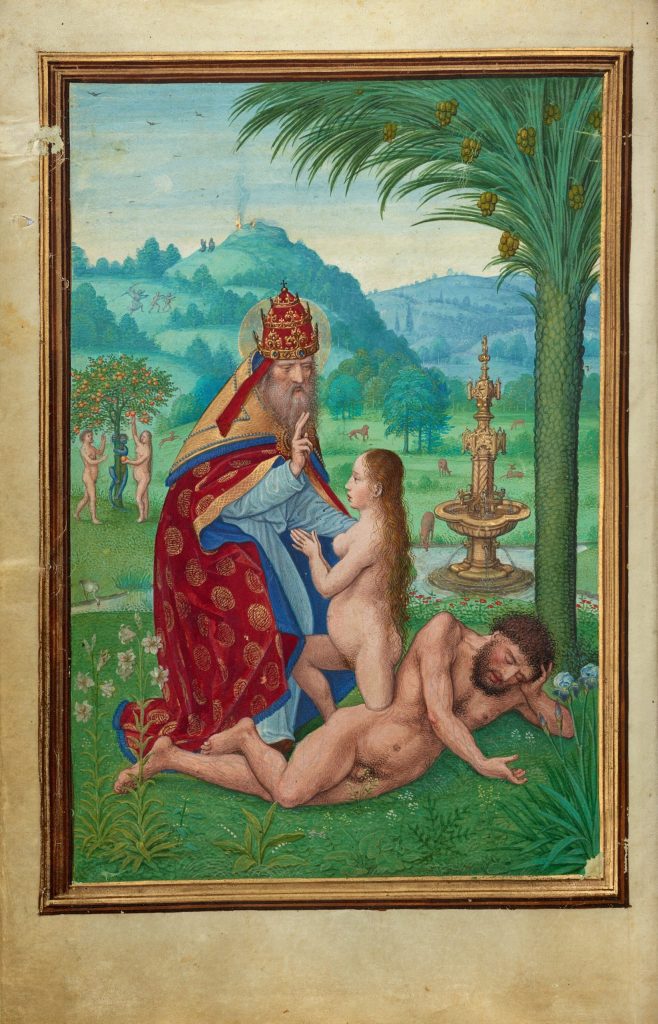

Fig. 1. Simon Bening, Scenes from the Creation, ca.1525–30. Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf

Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 7v, 83.ML.115.7v.

In examining how the male gaze has shaped religious iconography, Simon Bening’s 1525 Scenes of Creation (Fig. 1) presented a fascinating case study. This illuminated miniature from the Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg depicts God creating Eve from Adam’s rib, but with unexpected nuances that caught my attention. In Bening’s original, under a date palm, a resplendently robed God the Father gently lifts a newly formed Eve from Adam’s side and blesses her. Adam, curled at God’s feet, is still fast asleep and blissfully unaware that his better half is under divine construction.

In the background of this tiny painting, Bening condenses the entire human doom-and-gloom saga: we see Adam and Eve reaching (together!) for the forbidden fruit, an angel brandishing a sword to expel them from Paradise, and even Cain and Abel on a distant hill making their offerings—with smoke rising from Abel’s accepted sacrifice and blowing sideways off Cain’s rejected one. In one miniature, the glory of creation is already undercut by the tragedy of humanity’s fate. Bening has tricks!

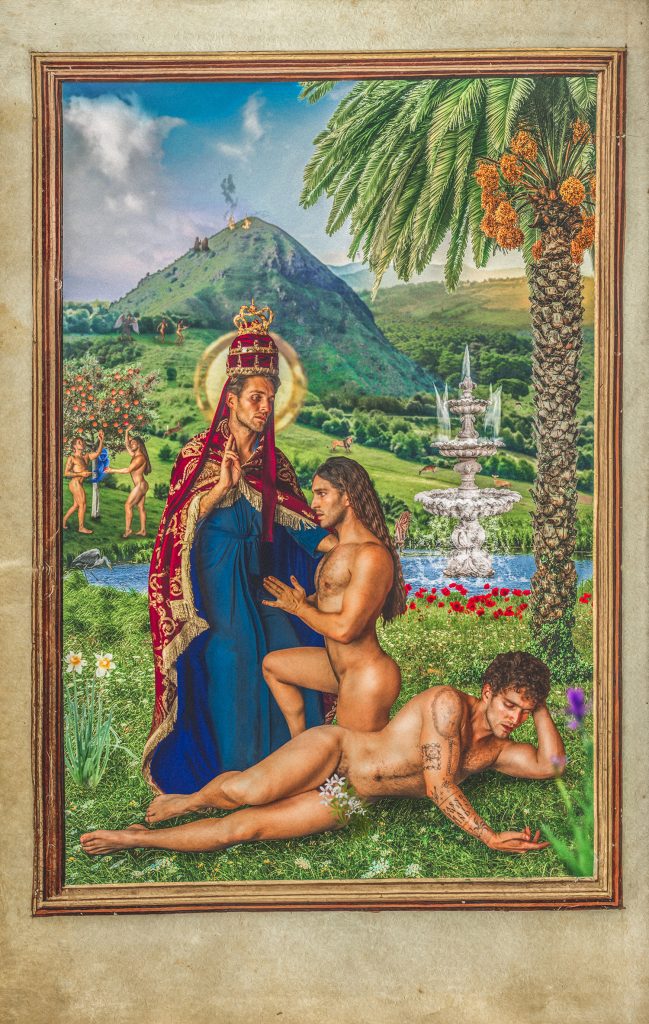

Fig. 2. Mario Elías Jaroud, Self-Portrait as Scenes from the Creation by Simon Bening, 2019.

My goal in recreating this scene was to queer the narrative Bening so exquisitely rendered (Fig. 2). By casting a single contemporary queer body as all three principal characters (God, Adam, and Eve), plus the background figures, I wanted to scramble the traditional signals of gender and power embedded in the Eden story. After all, the Genesis account has long been used to prop up heteronormative and patriarchal structures: God as white-bearded lawgiver, Adam as prototype for all men, and Eve as the afterthought crafted from the man, yet solely responsible for that pesky Original Sin. A tidy little reminder for women to obey their fathers and husbands lest they upend the divine order and ruin everyone’s lives.

In medieval art and literature, especially, Eve’s legacy looms large. Illuminated manuscripts, in particular, are not unlike social media: peddling gendered and societal messages in vivid color. Eve is the OG cautionary tale: temptress, transgressor, teachable moment. Christian thinkers (most of them… you guessed it… straight white men) loved to contrast her with the Virgin Mary. It’s giving Eva vs. Ave: Eve the dangerous, naked woman who unleashed death and despair, versus Mary, the holy virgin who brought salvation into the world.

But Bening did something different in Scenes of Creation, and that’s what drew me in. For starters, his composition is surprisingly kind to Eve. He shows God tenderly raising her up, almost like a father helping his child take her first step. There’s a palpable sense of love and approval in that gesture of blessing.

Bening doesn’t paint a she-devil; he paints an innocent. And crucially, when the moment of temptation arrives, Adam is right there alongside Eve, reaching for the fruit. They act together in destroying their future. This detail quietly undermines the old “Eve made me do it!” narrative. Bening’s visual storytelling suggests the Fall was a joint effort, a tragic husband-and-wife team-up, not the fault of one conniving woman. In a prayer book made for a powerful clergyman, that’s a noteworthy nuance.

It’s as if Bening, within the constraints of his time, managed to slide in a bit of justice for Eve. She isn’t depicted with a sly expression or a serpent coiled erotically around her. She’s fresh from God’s hand, unclothed but unashamed; she’s a vision of purity, not punishment. And that nudity is crucial. In medieval art, naked bodies in Eden meant innocence, not indecency. No fig leaf jockstraps or bikinis in this spring collection! That all changes post-snack time, when shame enters stage left, but for now, ignorance is bliss… and butt-naked.

This generous reading of Eve’s story became the foundation for my own reimagining. Where Bening offered subtle justice within traditional constraints, I wanted to push that liberation further to create an Eden where queerness isn’t excluded but celebrated as part of the original design.

In my recreation, I claim that pre-Fall freedom as my birthright. Every follicle of body hair, every stretch mark, every detail of my queer body becomes sacred geometry in this new Eden. I’m not asking for permission to exist in paradise; I’m announcing that we were always meant to be here.

Now, let’s talk about the one-body-three-roles conceit, because it’s the loudest way I’ve queered Bening’s scene. In my composition, you see “God” in ornate robes and a towering papal tiara, one hand in a blessing gesture. Kneeling before “Him” is “Eve,” completely naked, with long hair cascading down her back and a reverent gaze upward. At God’s feet lies “Adam,” also nude, snoozing on the grass (men… am I right, ladies?). The effect is surreal, theatrical, and, if I’ve done it right, deliciously subversive.

I’ll admit there’s a dash of cheeky heresy in portraying my gay ol’ self as God. But isn’t there also poetic justice? In medieval art, God the Father is almost always an old white-bearded patriarch (basically a grander version of the artist’s own male patrons). Not anymore. By inserting a queer body into these roles, I’m cheekily reclaiming that goofy “God made Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” taunt. My very existence in this image mocks that slogan’s narrow-mindedness like a visual retort to the heteronormative gatekeepers of Eden.

And by collapsing those roles of Creator, Man and Woman into one body, I’m challenging the whole structure. Gender here is a performance: a robe, a wig, a pose. Medieval actors knew this too. It’s all drag, baby. And once you see that, the power dynamic shifts. God isn’t some far-off father figure. He’s cut from the same fabulous cloth as the created.

Visually, I kept it playful and referential. There’s the fountain of life bubbling away, rolling hills, shiny apples—classic Eden vibes. But it’s a queer paradise now, a place of authenticity and expression. Bening showed Eden as innocence soon to be lost; I show Eden as innocence reclaimed. This isn’t about sin. It’s about selfhood. So yeah, it’s irreverent. But irreverence is how we survive. This self-portrait is my love letter to medieval art and my middle finger to the rules that tried to keep us out of the frame.

Bening gave Eve a fighting chance, and I just wanted to take it a step further.

In the end, this reimagining is both tribute and rebellion, illumination and self-expression. Bridging 1525 and 2025, it honors the gold leaf, the careful brushwork, the sacred drama while remixing Genesis for the rest of us. Where the letter of scripture meets the spirit of queer resistance. And it was very good.