Alexandra Alvis • Winterthur Library

Recommended citation: Alexandra Alvis, “Rainbow Medievalism,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/FRUE8301.

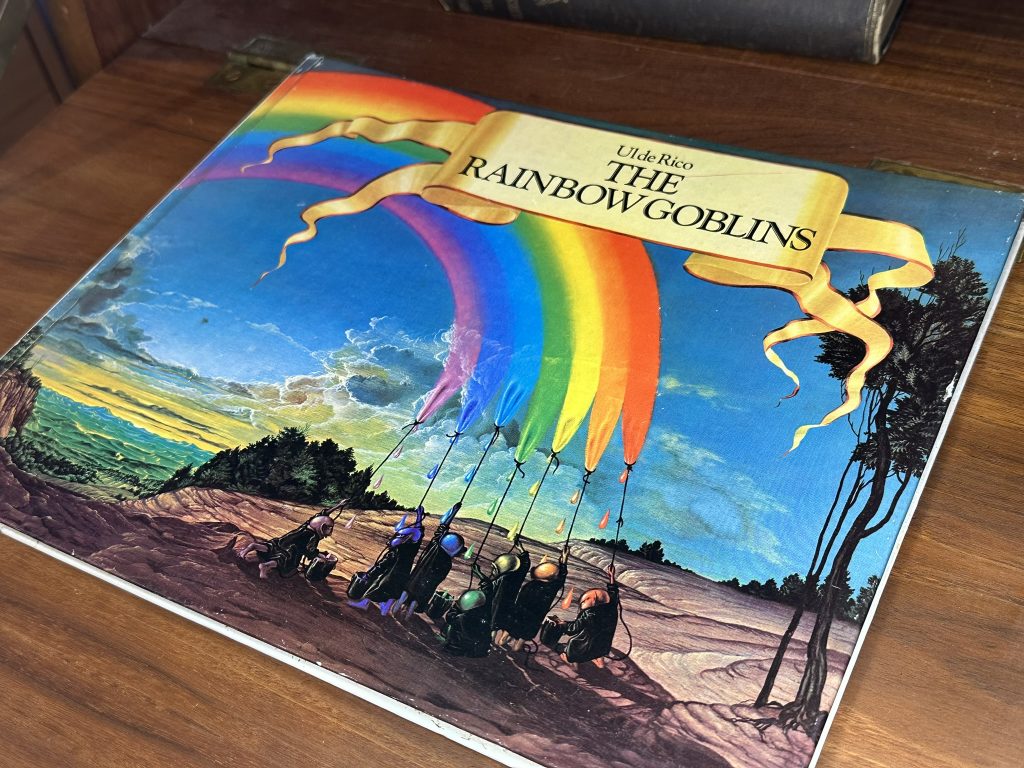

Fig. 1. The cover of Alexandra’s copy of The Rainbow Goblins.

“I’m not gay, I just really like rainbows!” I would often declare as a young teen in the early 2000s, when questioned about my aesthetic choices. I owned rainbow earrings, a rainbow necklace, decorated my notebooks with rainbow stickers; I loved colorful things. I was also extremely, deeply in denial about my queerness, so my display of rainbows wasn’t some vibrant effort to nonverbally communicate my identity. Of course, frequently proclaiming that I was cis and straight did very little to convince the school bullies, who clocked me before I did.

I can trace my love of rainbows to my early childhood, specifically to Ul de Rico’s 1977 picture book The Rainbow Goblins. The book chronicles the grim fate of seven greedy goblins, each of whom only eats the essence of one color, as they are thwarted in their efforts to devour the rainbow in the valley where it is born. My local library had a copy of a late 1980s edition, which saw heavy circulation to my house. I was transfixed by Ul de Rico’s vivid color choices and drawn into the depths of his complex landscapes, spending far more time looking at each page than it took for me to actually read the words printed on it. His art style was remarkably distinct from the other picture books my parents read with me, and despite their best efforts to diversify my bibliographic palette, I kept coming back to The Rainbow Goblins.

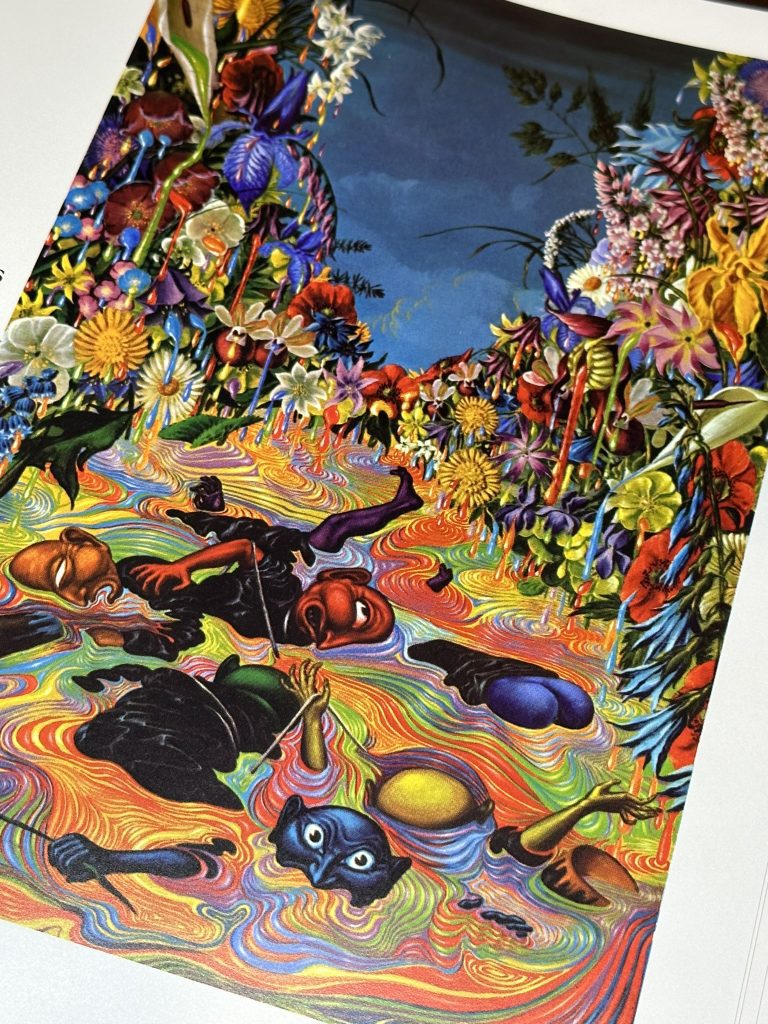

When I reflect on my love of that book, the old adage that “hindsight is 20/20” rings in my mind, made all the louder by writing said reflection as a queer curator of special collections with a medievalist background. Almost every illustration is a blinking neon arrow that points towards where my sensibilities and academic interests would develop, from the dripping rainbow marbled endpapers to the title page that arranges the goblins into a pastiche of the Biblical last supper. Ul de Rico’s towering, swirly rock formations seem to come straight out of the illuminated miniatures of late medieval manuscripts, and his visual humor would not be out of place among the marginal grotesques in those same works.

As I declared my love of rainbows and denied my queerness in one breath, so too did I maintain my love of the aesthetics represented in The Rainbow Goblins while decrying medieval art. From the same age that I was reading picture books, I was also poring over my mom’s old college art history textbook, becoming acquainted with the Old Masters and the Impressionists, whose works I would render in crayon. If this textbook mentioned medieval art between its discussion of the arts of antiquity and the Renaissance, I don’t remember it; this was echoed in the art education I would receive in school, which emphasized that the “Dark Ages” – where everyone in the West mysteriously forgot how to make realistic art – were not worth considering. At some point, I stopped thinking of The Rainbow Goblins, replacing it with young adult fantasy novels such as Tamora Pierce’s Alanna series. When I was assigned to write a history paper in high school about the Limbourg brothers, I was dismayed when I found out that they were – ugh – medieval artists. My teacher rationalized their inclusion on his list of paper topics by relating them to the development of the Renaissance, pondering what kind of a positive impact they would have on the art world had they not died so young. For my next paper I was assigned Hieronymus Bosch, who I was more than happy to delve into as he was decidedly not medieval – or so I was told.

This negativity toward medieval art was mirrored in my community’s negativity towards queerness. At my small Kansas private school, conformity to conservative attitudes and aesthetics was socially rewarded; with my short hair and my colorful fashion sense, I was a walking example of how not to be. Bullying often took the form of accusations of queerness, that my haircut somehow marked me as a lesbian and that my clothes meant I was any variety of slurs. All of this implied that who I was was not of value – much like the art created by medieval artists, who I was taught didn’t have the skills to produce anything of quality. If I wanted to be a good person, I should “get over it” and progress beyond this crude identity, just like the Renaissance artists who surpassed their medieval predecessors.

For a while, I convinced myself that I was neither queer nor interested in the Middle Ages. But my numerous reads of The Rainbow Goblins as a child had endeared medieval and early modern aesthetics to me; I was drawn to medieval-ish movies such as The Lord of the Rings, The Dark Crystal, and The Last Unicorn, and spent many happy afternoons at “Renaissance” fairs. I was still in denial when I began my first master’s degree at the University of Edinburgh – right up until the first time I saw an illuminated manuscript during one of my classes. Like the pivotal scene in The Rainbow Goblins where the flowers release all of the rainbow’s colors in a flood to drown the goblins, all of the love I had been holding back for medieval art suddenly rushed through my mind, eroding the false idea that it was somehow technically lesser. As I hurled myself into learning about the Middle Ages through Edinburgh’s holdings of illuminated manuscripts to make up for lost time, I stopped making excuses for my interest and instead shouted it from the rooftops. Though embracing my queerness took a few years longer, it was a similar experience of a euphoric game of catch-up.

Fig. 2. The Goblins die colorful deaths.

I don’t remember why, in 2022, I was seized with a desire to re-read The Rainbow Goblins; I ordered the cheapest copy I could find online. When the slightly worse for wear first American edition arrived in the mail, my personal hindsight achieved 20/20 vision. It was suddenly abundantly clear that this was my ur-medieval, the thing that had primed me to do the kind of visual analysis central to my role as a book historian and medievalist. I once again took my time absorbing the illustrations, now able to understand Ul de Rico’s artistic references: the cloud-dappled horizons of 17th century landscape paintings, the triptych-like framing of the final illustration. I also recognized the hand of Hieronymus Bosch in the figures of the goblins, whose colorful and grimly humorous deaths would fit seamlessly into the Hell panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights. With this realization, the memory of my high school disdain for the Limbourg Brothers and my enthusiasm for Bosch bubbled to the surface; how comical to think that Bosch could be taught without reference to the medieval underpinnings of his visual language and style.

Re-reading The Rainbow Goblins was like coming across one of those optical illusions that requires you to look at it from a certain angle to make sense of the image, and that angle was Medievalism. The line drawn from the vibrant miniatures that made me come to terms with my love for the medieval and The Rainbow Goblins only connects thanks to the ability of Medievalism to stay distinct from the medieval. Although I actively avoided the medieval, I continued to enthusiastically consume media that displayed Medievalism, never considering the inherent contradiction. With Medievalism as a consistent background noise in my life, when it finally came time for me to accept my medieval interests, I was able to do so not just as a historian but as an audience member – something that informs my current scholarship on Pop Bibliography.

Though I now understand that the goblins of The Rainbow Goblins were portrayed in a homosocial way, I can’t quite make the same causal link between my queerness and the book. However, it served a very similar function for me as the presence of Medievalism. Until I was able to come to terms with my identity, media like The Rainbow Goblins allowed me to explore the idea of living a more colorful life without definitively outing myself. And now that I am able to live authentically, rainbow flags have become a symbol not just of Pride, but of how far I have personally come to be able to fly them without excuse.

Looking back on how long I managed to maintain my denial of my interests and self, I am not sure whether to chuckle or to mourn. Would I have been in a better position had I understood who I was earlier – like how my history teacher wildly theorized the Limbourg brothers would have brought about an early Renaissance had they lived? Hindsight reveals not just connections, but a hail of missed opportunities. When I saw the call for submissions for this issue of Different Visions in early 2024, my mind went straight to The Rainbow Goblins. I did some preliminary Googling of Ul de Rico – real name Ulderico Conte Gropplero di Troppenburg – and found that he had died in the interim of when I purchased the book and when I was writing up my abstract. I was struck by the deep sadness I felt upon learning of this death. Ul de Rico was never a part of my life, his book was; I had never even seen a photograph of the man until I visited his personal website in 2022. I realized that my re-discovery of The Rainbow Goblins came with a fantasy of somehow corresponding with Ul de Rico, and being able to tell him how much the book meant to me. My dream of talking with him more about his historical inspirations and his other works was now completely out of reach.

This sense of lost (or worse, squandered) time that came with my learning of Ul de Rico’s death was a potent memento mori that felt, strangely, medieval. Or medievalish, at least. Like Megan L. Cook’s Dirtbag Medievalism, my grief over missed opportunities did “not care much about anything that actually happened […] it care[d] about the idea.”[1] It was not the loss of something that existed, but the loss of a possibility. My mourning for the me that could have been and my sadness at narrowly missing Ul de Rico on this mortal coil are of a similar emotional family – both predicated on uncertainty. Had I realized I was queer earlier, could I have avoided the bullying? If I had reached out to Ul de Rico, would he even have responded? Had I pursued medieval art as a subject sooner, would I be more advanced in my career? Logically, I know it is impossible to say that if (x) was different about the past, (y) would be true now. However, logic is not always the strongest opponent of emotion.

As ever, the only way out is through. Though I can never rekindle the potential energy of my youth or the life of an important artist, I will make the best of what I have now. Though I wound up on a professional path that means medieval books are almost entirely absent from my day-to-day work, my medievalist background allows me to contextualize later Western print cultures and decorative arts for budding scholars – no more of that “Dark Ages” stuff. No more value judgements made on historic art based on how modern eyes perceive the skill level of the artists who created it. I strive to be the kind of person and educator that I rarely encountered in my younger days: someone that the next generation doesn’t have to defend their interests or themselves to, who will help them find their own way without forcing them into someone else’s. Quite an ambitious goal to wrap up the end of a reflection on a colorful children’s book, but it speaks to the power of formative experiences like the repeated reading of a treasured story. I hope that my rainbow–tinted medievalism that arose from The Rainbow Goblins will help others avoid a prolonged denial of their own.

References

| ↑1 | Megan L. Cook, “Dirtbag Medievalism,” Avidly, 14 July 2021, https://avidly.lareviewofbooks.org/2021/07/14/dirtbag-medievalism/.

|

|---|