Christopher Herde • University of Wisconsin

Recommended citation: Christopher Herde, “Open the Gates: Medievalism and the Movement Beyond Accuracy,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/VSVC7092.

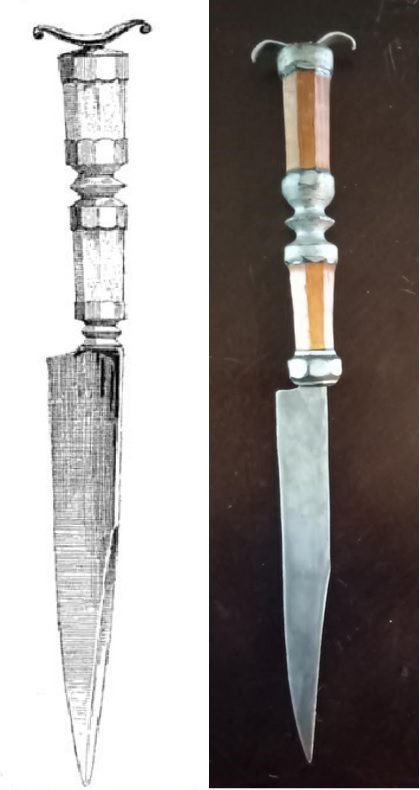

In the spring of 2015, toward the end of my undergraduate career, I was hard at work digging through historical documents that had nothing to do with my degree. Rather than studying for exams, writing papers, or drinking like a sensible 21-year-old, my evenings and weekends were dedicated to preparing for my upcoming role as a street cast performer at the Kentucky Highland Renaissance Festival. I had been given broad leeway to define my character, and had chosen to represent a minor historical figure – a young knight from the 14th-century Seton family. Thus, when I wasn’t attending performance rehearsals and improv training, I would dive back into the scant historical records of medieval Scotland. Due in part to the aristocratic tradition of recycling names, I was having considerable difficulty in separating out what sources referred to which of three successive Alexanders Seton. The only thing I could determine with any certainty was that my Alexander was well-known to carry an “unusual dagger.” I traced references to the dagger down through generations of the family, eventually discovering that an old photo of it was held in the archives of an American university. Here I struck a dead end, however, as the archive in question responded to none of my inquiries. Just as I was about to abandon the search, another performer sent me a few 19th-century histories he had found in the course of his own research. By sheer cosmic coincidence, the first page I opened in one of these texts contained a detailed illustration of the very dagger I had been trying so fruitlessly to locate. I could talk of nothing else for weeks, and immediately commissioned a local artist to make a replica based on the image.

Fig. 1. Left: Drawing from Robert Seton, An Old Family, or the Setons in Scotland and America, New York: Brentanos, 1899. Right: Replica by Napier Arts, 2015.

Within the month, one of my professors took note of my enthusiasm, and permitted me to replace the final assignment for his class with a paper based on my research into the Seton family. That paper would ultimately be the writing sample that I attached to my first successful grad school application.

Since then I have remained firmly committed to the idea of medievalism as a source of joy, exploration, and engagement with the past. The initial freedom I felt to play with the medieval and to take ownership of it were essential precursors to my discovery of the joy of research. The unabashed silliness of Ren Faire and the gaming table laid a groundwork of passion and excitement that has sustained me through the ensuing decade of scholarship and all the accompanying rejections and trials. It has only intensified into a sort of gleeful determination that will undoubtedly carry me through decades more.

This was my path. While it is by no means the only or even the most ideal path, it is one I wished to leave wide open behind me. For years I bandied about plans and ideas on how to systematize a medieval hobbyist-to-scholar pipeline, all of which foundered between the rocks of play and the hard place of preserving and propagating an accurate understanding of the past. Everything I came up with ultimately resolved down into unrequested impromptu lectures at best and exclusive “well actually”-ing at worst.

I have since discovered that the obvious answer was to simply let people be wrong. Let them explore, play, and take ownership of the medieval just like I did. Provide inspiration where possible and resources when requested. Match passion and interest with more of the same, and let people decide for themselves when they want to go deeper. After all, no matter how central an accurate understanding of the past may be to our lives and work, it doesn’t occupy anything close to a position of paramount importance to those around us. Loudly insisting on its necessity every time a new film or game engages clumsily with the Middle Ages will not change that.

My hesitation to accept this conclusion stemmed primarily from anxiety about the ubiquitous shadow of Godwin’s Law[1] hanging over all modern questions about medievalism: Neo-Nazis. Like every other medievalist I know, I was infuriated by the brazenness with which conservative trolls and white supremacists distorted and paraded the Middle Ages as justification for their hatred, violence, and racism. My immediate reaction was to push back against them on every front. When rioters in Charlottesville and Washington DC claimed to be vikings or knights, I made sure everyone knew how wrong they were. When online culture warriors whined about the presence of non-white actors in medieval-themed media, I was ready to hand with primary sources. Whenever conservative ideologues even mentioned the Middle Ages, I sallied forth to assert the illegitimacy of their narratives, of their claim to any part of the past I studied. This impulse felt natural and correct. As experts on the medieval past, it was our responsibility to present an accurate counter to the distortions flying about the public discourse. It was something relevant, important that we could offer society, and it was the exact thing we are trained to do: analyze historiography, critique sources, and correct past historical narratives. The medieval is our territory, after all, and this was our chance to stop an enemy at its gates. And yet, while sitting through one conference presentation after another that began by recapping Charlottesville before pivoting to a comparison of screen-grabbed tweets to manuscript images, I couldn’t help but wonder if we were going about this the wrong way.

In the first place, this attitude assumes that neo-nazis care one way or another about the accuracy of their facts. They don’t.

Second, it rests on the supposition that we are the sole arbiters of what is and isn’t legitimately medieval. Even if one argues that we should be, the fact of the matter is that we are not. There are countless stakeholders in the concept of the Middle Ages, from individual enthusiasts to organizations like the Society for Creative Anachronism, from reenactors to fans of Braveheart, Game of Thrones, and Kingdom Come: Deliverance. Regardless of how true their visions of the past are, one can not deny their investment in the medieval nor their role in shaping public perception of it. By insisting on historical accuracy as the paramount ideal of medievalism in order to exclude bad actors, we not only incidentally gatekeep many of the other stakeholders, we also inadvertently lock them on the same side of the gates as those bad actors. This has had the added effect of casting us historians as joyless pedants, wielding pointless nitpicks against all comers and shouting “well, actually” from our ivory battlements. For evidence of this, look no further than Ridley Scott publicly baiting historical controversy to milk free publicity for film projects like Napoleon. Was anything truly gained by that Twitter discourse and the ensuing media coverage of “furious historians” “slamming” the films for their inaccuracy?[2] I don’t wish to give the impression that I agree with Scott’s take on history or his opinion of the field. I merely wish to ask: what does it say about our relationship to the rest of society that a Hollywood director could make such a transparent marketing ploy, safe in the knowledge of how “the Historians” would react and how the wider public would view the ensuing controversy?

Third, it implies that historical accuracy is somehow virtuous in and of itself. Even when non-academics do adopt accuracy as the highest ideal of medievalism, does that make their communities better? Consider as an example the SCA, an organization whose members pride themselves (in many cases justly so) on their commitment to accurate and well-researched recreation. In Medieval Fantasy As Performance: The Society for Creative Anachronism and the Current Middle Ages, Dr. Michael Cramer addresses the issue of race in the SCA through the anecdote of African-American SCAdian Eric Gardner. Upon joining the organization, Eric took on the implicitly-white sobriquet “Eric of Huntington.” He continued under this name up to the day of his knighting ceremony, a significant mark of prestige and recognition within the community. When the region’s “King” (the leader of the local chapter) presiding over the ceremony asked the name under which he wished to be knighted and announced, he chose to reintroduce himself as “Eric Ibraheim Mozarabe.” Cramer claims that the “King” in question

…was Chris Ayers/Duke Christian du Glaive, whose persona is a Norman Crusader. A strong proponent of acting “in persona” and maintaining a medieval attitude at all times, he was clearly bothered by Gardner’s declaration. He had no problem knighting a black man, but for his crusader knighting a Muslim created an issue. As a compromise, he continued the ceremony using both names, saying “Eric Ibraheim Mozarabe, also known as Eric of Huntington…[3]

Cramer puts this down to a failure of research, pointing out that Ayers was ironically unaware that Mozarabs were not in fact Muslims but rather Arabic-speaking Christians living in Muslim Iberia. Accuracy was the ideal, and if only the poor enthusiast had known what the scholarly author knows, all would have been well. I reject this framing. As the leader of a voluntary social organization presiding over a ceremony to honor the commitment and accomplishments of one of his own members, at the moment in which all attention was rightly focused on that individual, Ayers made the moment about himself. The celebration of Gardner’s hard work was just too good an opportunity to remind the audience about Ayers’ own character and commitment to accuracy for him to pass up. No explanation of the complexities of Iberian ethnic and religious identities, no presentation on the history of friendly contact between Frankish crusaders and Muslim fursan will address the fundamental problem that in this moment historical accuracy mattered more than people.

Ayers’ actions are by no means comparable in terms of scale or intentionality to the malicious race-baiting and homophobia of alt-right Templar cosplayers.[4] However, the same fundamental mis-ordering of priorities underpins both attitudes and, perhaps most significantly for this discussion, characterizes the scholarly response to both. By building our rebuttals around the inaccuracy of white supremacist history, we are inadvertently obscuring the fact that historical inaccuracy is far from the greatest of their crimes. The most pressing danger posed by the far right is not what they are doing to the past, but what they are doing in the present and what they want to do with the future. While it certainly feels correct that an attack on their historical claims is by definition an attack on their future ambitions, I believe that this approach leaves us wide open to misinterpretation. On the one hand, it could imply that if the trolls and hate-mongers simply returned with better evidence, then their position might be legitimate. On the other, it could give the impression that historians are little different from conservative ideologues, each employing the claim of objective historicity to cloak a primarily political agenda.

We do have an agenda in fighting Nazis, after all, don’t we? To directly counter the white supremacist vision of the future with one of our own? I don’t mean to present myself or you as equivalent to the trolls, or as cynical policy hacks who only care about using history to support our politics. But it is disingenuous to claim that our interest in history, in this debate, is devoid of politics. If it were simply a matter of stupid people being wrong, would we care this much? Certainly, the alt-right version of history is reductive, distorted, and incurious, but at least as far as I am aware the primary objection is not to their narrative of the medieval itself but to the purposes to which that narrative is being put. And if that is the case, then the accuracy of that narrative must be of lesser importance than the social and political implications of the purposes themselves. This is not to say that accuracy is of no importance, that there is no value in calling out blatant lies or correcting bad-faith interpretations of the medieval past. But those lies, those narratives aren’t the final boss, and more scrupulously well-footnoted narratives are not a silver bullet for defeating them. Accuracy is just one tool, and particularly when it comes to works of fiction, worlds of fantasy, and spaces of play, when it comes to medievalism, I find it a rather blunt and ineffective one. One that, if wielded haphazardly against every problematic, simplified, or just mistaken depiction of the Middle Ages regardless of intent or impact, threatens to undermine our very purpose in using it.

Therefore, instead of continuing to fight the war for accuracy from the same tired battlements, I recommend that we open the gates. Let everyone in to explore the medieval and make their own meaning. Remember the passion and joy that brought us here and help to foster it instead of punishing anyone whose exuberance leads them off the path. Focus our efforts on supporting those who feel lost or out of place, and diligently attack the nazis and other inevitable bad actors not on the basis of their inaccurate claims but on the basis of their bad acts. I do not mean to recommend here that we abandon the goal of accurately understanding the Middle Ages, nor that we should lessen the rigor of our own scholarship or give up on the idea that an enjoyment of medievalism can be a pathway for some hobbyists to become well-researched experts. After all, that was my path and it is one I wish to leave open behind me. However, I have come to the conclusion that I will do myself, my audience, and my discipline no favors by trying to force people onto that path, or by dismissing those who do not express interest in it. Rather, I recommend that we as scholars take a step back from being the gatekeepers of the medieval. Go out and have fun once in a while. Show up simply to support others’ engagement with the past without the goal of correction or recruitment. Treat everyone as colleagues of mutual interest and endeavor to meet them where they are. And when we do grapple with those who would try to harm others, let us not draw immediately and exclusively upon our authority as historians but upon our authority as humans with empathy. For surely we have no less expertise in the latter role than the former.

References

| ↑1 | “A facetious aphorism maintaining that as an online debate increases in length, it becomes inevitable that someone will eventually compare someone or something to Adolf Hitler or the Nazis.” Oxford English Dictionary, 3nd ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), s.v. “Godwin’s Law.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Zack Sharif, “Ridley Scott Tells Historian Who Called Out ‘Napoleon’ Errors to ‘Get a Life,’ Will Say ‘It’s About Feckin’ Time’ If He Ever Wins an Oscar,” Variety, November 6, 2023. https://variety.com/2023/film/news/ridley-scott-napoleon-historical-fact-checkers-1235781258/. Elsa Keslassy, “French Historians Slam Ridley Scott’s ‘Napoleon’ Inaccuracies: ‘Like Spitting in the Face of French People,’” Variety, December 7, 2023, https://variety.com/2023/film/news/napoleon-inaccuracies-french-historians-pyramids-1235823975/. Marianne Guenot, “Historians Absolutely Hate Ridley Scott’s Napoleon Movie,” Business Insider, November 27, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/historians-absolutely-hate-ridley-scott-napoleon-movie-2023-11?utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter&utm_campaign=insider-sf. |

| ↑3 | Cramer, Michael A. Medieval Fantasy as Performance: The Society for Creative Anachronism and the Current Middle Ages. (Rowman & Littlefield, 2010). 40. https://doi.org/10.5771/9780810869967. |

| ↑4 | Lydia Wilson, “Pete Hegseth’s Tattoos and the Crusading Obsession of the Far Right,” New Lines Magazine, November 29, 2024, https://newlinesmag.com/essays/pete-hegseths-tattoos-and-the-crusading-obsession-of-the-far-right/. |