Larisa Grollemond • Getty Museum

Recommended citation: Larisa Grollemond, “Midwestern Medievalism,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/ANTI2335.

I must have been around seven or eight years old when my parents took me to the Bristol Renaissance Faire in Bristol, Wisconsin for the first time. My little sister, who would have been just four or five, was also on that trip, though I have no memory of her being there in the way that children have extremely selective memories of things in hindsight. It would have been during a summer vacation in the early 1990s, probably sometime in late July or August in the desperately boring and swelteringly hot midwestern late summer weeks before school started again. The small 1950s farmhouse that I grew up in was stifling in the summer, humid air hung unmoved by breeze. One ancient air conditioner worked tirelessly in a window, blocking the light like some sort of grumpy, wheezing ogre. We spent most of our summers outside catching toads and playing make-believe games in the far reaches of the backyard and in the hayfields and horse pastures around our house where we couldn’t be seen from the kitchen window. We went, or rather we were taken, to the Renaissance Faire probably because we were in dire need of entertainment, something to do on a summer weekend when all other outdoor options had been done what felt like a million times and the refrains of “but I’m so bored” had probably gotten overwhelming. Being bored, though, seemed an entirely legitimate complaint during the three months off from school that seemed truly unending, a lifetime between first and second grades. We ended up back at the Renaissance Faire many times after that first visit as a family, probably every summer until I was old enough to drive myself along with my nerd friends. Every time felt the same, a fixture of late summer childhood.

Bristol was just over the Wisconsin-Illinois state line, and what felt to my childhood self like an impossibly long drive from where we lived in rural northern Illinois, though I regularly sit in traffic on the 405 during my commute to work for longer stretches of time now. That drive, like many drives through the rural midwest, was just endless corn and wheat fields whipping by out the window of a car that I don’t remember but which probably didn’t have air conditioning; all the cars we rode in growing up were used, but not in the certified pre-owned way, but ancient sedan models from the 1970s that smelled like cigarette smoke and had odd-colored velvet seats pockmarked with their burns. There being little else in the immediate area, the Renaissance Faire was an attraction, the kind that you see signs for on the road miles before you get there: “Bristol Renaissance Faire, Fun for the Whole Family! Just 20 more miles!” with a cartoon cut-out of a pirate or a corseted lady holding a stein of beer. When we got there, I always felt as if I had just traveled the length of the Oregon Trail, on which I was an expert from playing the computer game of the same name on my friend Jamie’s family PC. It never looked like much at first: just an open field that had been repurposed as a parking lot, broken weeds baking in the sun and muddy tracks marking the trails for foot traffic to the entrance.

It wasn’t a disappointment though, the journey felt like time travel. The entrance gate to the Faire was, to my young eyes, a magical portal: a huge Tudor-style building with a pitched roof and two shingled towers with flags that would have looked better flapping in the wind but which were more often hanging limply in the summer air, big wooden doors flung open.

Fig. 1. Bristol Renaissance Faire entrance gate.

The wooden coats-of-arms and snaking ivy added a sense of legitimacy, as if someone had said, “Yes, this is absolutely what 16th-century England looked like. Trust us.” And I did. People waited in line for tickets, some dressed in the most elaborate, real-looking costumes I’d ever seen, even at Halloween. Here we were, at the precipice of real history. Crossing the front gate truly felt like stepping into a different world, leaving the American midwest behind entirely, and entering a past that felt unknowably old, the pounding of simple drums and melody of flutes in the air and the shouts of the performers on the stage shows and raucous laughter of the audience near the entrance beckoning.

The historical concept of the Bristol Renaissance Faire is that it takes place in 1574, during Queen Elizabeth I’s visit to the port city of Bristol, England. The 30-acre site, home to a set of permanent, English Tudor-style structures built into a heavily wooded area that recreates the winding dirt streets of a medieval city, houses a huge variety of stages for performers, food stalls, and shops selling things you didn’t need but suddenly wanted very badly. The Bristol Faire was founded in 1972 by Richard and Bonnie Shapiro as “King Richard’s Faire,” inspired by the first faires held in Southern California in the 1960s. The Bristol Faire was sold in 1988 to Renaissance Entertainment Corporation, Inc., which still produces it along with two in California and one in New York.

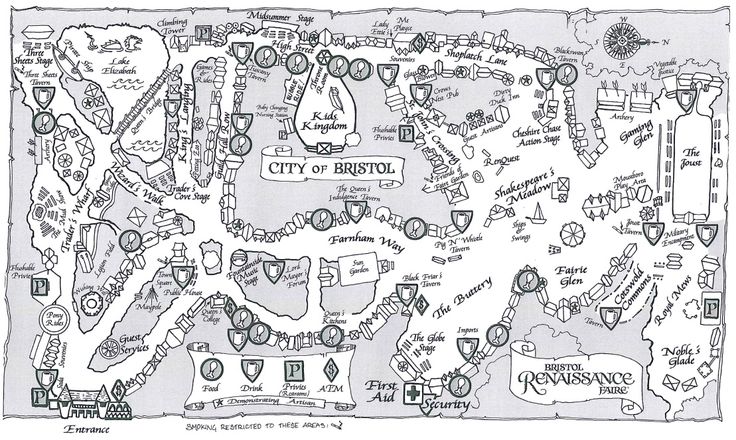

The details of the proposed historical setting of the Faire didn’t concern me much as a child, except that I liked that it was in a place called Bristol. The correspondence with the “real” English Bristol felt important for establishing a sense of legitimacy, as if these events could actually be taking place here in rural Kenosha County. The hand drawn map, an aerial view of “the city of Bristol,” that was given to visitors at the front gate reminded me of the maps in the fantasy novels that occupied so much of my time–the ostensible year and place of the faire didn’t matter to me as much as it felt like somewhere and somewhen else altogether.

Fig. 2. Bristol Renaissance Faire Map.

In practice, the faire is an amalgamation of periods and influences, encompassing a variety of medieval cultures (Celtic pagan religions, Vikings, performance art of the Black Death, etc.) and since I started going in the 1990s, has expanded to include a huge number of fandoms, nerd cultures, and alternative identities, even in red parts of the country that are known for being more politically conservative. In hindsight, the historical scaffolding of the Bristol faire seems especially rigorous: staying for the whole day (10am-7pm) followed the narrative of the Queen’s visit to the city from London, with a full schedule of appearances at various events throughout the faire: the mid-afternoon joust in her honor, traveling around the faire to speak to her subjects and learn about the local people and events, and rest periods with her court where visitors could observe them dining, drinking, and dancing.

As a painfully shy kid, the experience of the faire was both exhilarating and terrifying. I lived in perpetual fear of being directly spoken to by the faire’s wandering performers, who roamed the streets of Renaissance Bristol in costume and speaking a particular way that was partially a midwestern-British accent punctuated by “good morrow” and “huzzah.” Yet the completely immersive experience of the faire was intoxicating. We ate food that would have been at home at the county fairs that we went to all the time (cotton candy, funnel cake) but was just weird enough (turkey legs, roasted candied nuts, meat pies) to be transportive. We saw stage shows and wandering performers that demanded audience participation and were messy and slightly debaucherous (the raunchiest jokes went entirely over my head until high school). If we were lucky, we were allowed to buy some sort of trinket or costume piece (a pewter dragon necklace, a princess hat) from one of the faire’s merchants, all dressed in historically inflected garb to sell their wares and feeling like people who existed only at the faire. It was impossible to imagine them in “real” life. The main event, of course, was the joust, which took place in a small fenced-in area ringed by open-air wooden bleachers, with a special area reserved for Her Majesty the Queen.

Fig. 3. Bristol Renaissance Faire Joust.

This event followed a similar story as the joust at Medieval Times, which we visited for school field trips and the occasional birthday celebration (that is perhaps a tale for another confessional Different Visions issue): a display of horsemanship and a friendly tournament that turned dark, with one knight abandoning his chivalric duty which then resulted in a joust to the death that happened later in the day, asking visitors to return to the jousting field after several hours to see the conclusion of the story. I especially remember this part as being blisteringly hot, taking place in the midday sun, but the sweat that visibly dripped from the knight’s faces was satisfyingly real. We had horses at home, of course, but these horses seemed entirely different, the loyal noble steeds of particular equine excellence.

My parents, aging hippies who I think were drawn to the socially liberal ethos of the faire even if they weren’t quite conscious of it, were perhaps surprisingly game. We usually stayed to see the denouement of the joust, heading back to the car as the food stalls served their last customers and the sun started to lower into a midwestern summer evening. Fireflies started to blink on and off along the road on the drive home, back to the present after wandering in some far-off land for the day. The Renaissance Faire taught me to suspend disbelief in a way that few other things did. It was a place where you could be anyone you wanted to be, even if that person was a pirate with an eye patch, a fairy with wings made of wire and tulle, or a knight with a plastic sword that looked like it had seen better days. There was no judgment at the Faire, only a shared commitment to the absurdity of it all. What mattered was that we were there, together, pretending.

Fig. 4. The author at the Bristol Renaissance Faire in 2006 with her mom, Theresa.

I don’t think that I really understood how important to my idea of history these many summer visits to the Bristol Faire were until working on The Fantasy of the Middle Ages exhibition and publication project with Bryan Keene in 2020-2022.

Fig. 5. A short video flipping through the book The Fantasy of the Middle Ages, Getty Publications, 2022.

Growing up on a midwestern farm, medieval or Renaissance history (the distinction couldn’t have mattered less to me) was an abstract concept, so far away as to be synonymous with fantasy; it was in no way grounded or concrete for me. Even in school, “history” was largely “American history,” and in the Illinois public school system, “American Civil War history.” I had visited the Abraham Lincoln cabin in Springfield, I had been to the battlefields, I went on the 7th grade class field trip to Washington, D.C. and saw all the monuments. That history was the real history. Growing up on a midwestern farm, my family was working poor. I wasn’t aware of that, not really, until I filled out the FAFSA (Free Application for Federal Student Aid), which required a reporting of annual household income, when I applied to college. I had a full and happy childhood and didn’t feel that I missed out on things, but we didn’t really travel outside of the midwest. I didn’t, as I later learned many of my peers in doctoral programs had, visit Europe or spend summers traveling abroad as a kid. I left the United States for the first time when I was twenty years old. Growing up on a midwestern farm, the history I encountered at the Bristol Renaissance Faire was my way in, and in at least some ways, my way out.

As a first-generation college student, there was so much I had to learn about what it meant to exist in higher education without the safety net of money and experience that so many of my peers had. There are a lot of unspoken rules, mostly that you never talk about the safety net of money and experience that provide a certain number of both quantifiable and also more intangible advantages when moving about the world. One of the other main ones was that it’s not always safe to admit that it was the Bristol Renaissance Faire and a healthy diet of YA fantasy novels and not a transformative childhood visit to see some Gothic cathedral in France or an early brush with Chaucer that made you a medieval historian. But the particular medievalism of a Renaissance Faire–it’s low-brow, anachronistic, escapist, flexible–is the medievalism of the masses, unencumbered by a pedantic insistence on “accuracy” as if such a thing is possible. It’s for regular people and it doesn’t try too hard, which I think makes it difficult for the more, say, socially privileged, scholars among us to fully understand or to really contend with in a rigorous way. The history that hooked me at the Renaissance Faire was viscerally alive, engaged, and demanded attention and participation. That’s history at its best in any venue, scholarly or otherwise. After all, I like my medieval history the way I like my Renaissance Faires– loud, creative, accessible, a little raunchy, and above all, fun.