Janet T. Marquardt • Eastern Illinois University, Emerita; Mount Holyoke College, Research Associate

Recommended citation: Janet T. Marquardt, “Medievalism at Age 9: Crafting a Model Castle and Countryside,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/BJEP6073.

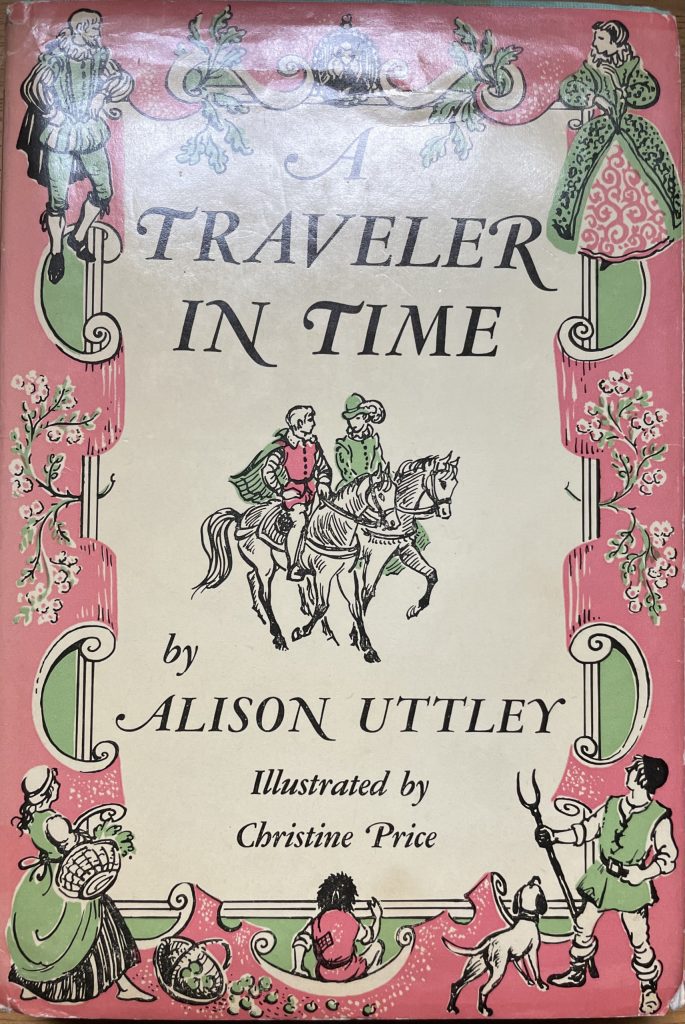

Between third and fourth grades, we were assigned a sheet with 10 lines to record our reading over summer vacation. I filled it in and added additional pages, topping out at 163 books for the season. Each week, my mom took me to the public library where I was allowed to check out 10 books at a time. Often I would finish them early and convince her to take me again before the week was up; other times I would get her to check out some books on her card for me to add to the pile. So, by fourth grade I had discovered time-travel worlds that would house my imaginary lives: colonial New England (which has left me obsessed with American 18th-century houses) and old Europe, especially the long Middle Ages. On the latter, read that summer, were two that have stayed with me over 60 years: The Mystery of Mont Saint-Michel by Michel Rouzé (La Forêt de Quokelunde, in French 1953) and A Traveller in Time by Allison Uttley (1939, which was technically Elizabethan, reprinted in the USA with one ‘l’ in Traveler). Coincidentally, the local classical music station was running a weekly morning program to introduce music to kids, such as a narrated “Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” that the nuns broadcast over the school’s PA system. The one I remember best was Elgar’s variations on “Greensleeves,” which happened to be a song used in Uttley’s book and thus brought to life by the story of the tragic Mary, Queen of Scots.

During that next school year, while we were studying the Western European Middle Ages, we were told to devise a project that would relate to what we learned. Most kids did drawings or encyclopedia-driven papers. However, I had spent many happy Sunday afternoons with my dad, his only leisure time, watching black-and-white movies on television like Ivanhoe, Knights of the Round Table, and The Adventures of Robin Hood. Between the stories and illustrations in the books and the sets and costumes in these movies, I had formed a strong idea about how I thought the medieval world looked. I decided to create my own dollhouse-sized version. I designed, built, peopled, furnished, and dressed an entire castle-church-and-countryside model. It was about 90 square inches and took me months. Disdaining sugar cubes, I used bits of wood and little stones, dirt and bits of weeds, “angel hair” (spun glass) from Christmas decorations for sheep and leather bits for cattle. I made the people out of pipe cleaners and sewed their clothes according to social status (those who fight, work, and pray!) as well as banners and flags. I still vividly remember some of the fabric scraps I got from my mom for the outfits—a coarse brown cloth tied with little rope-like strings for the serfs’ smocks, black bits of wool made into robes with tiny hoods, also tied with string, for the monks; bright and shiny linen and silk for chemises, robes and surcoats of the royals, and of course foil armor and weapons for the knights but also metal buttons with raised lions as shields. There were furs and veils and coifs and brimmed caps and helmets. After a while, our set of the World Book Encyclopedia opened automatically at the pages illustrating each costume. I’ve never enjoyed sewing again so much as I did that year and it earned me my first sewing machine, which I still have and use, as a gift on the following Christmas.

Oddly enough, I did not include nuns in the mix of feudal society, even though I was at a Catholic school. Nonetheless, my teacher—Sister St. John—apparently did not hold this against me, and liked my project so much that she asked my parents to let her take me to present it in person at the annual education conference held at the order’s local college. I had to write a speech about it and use a microphone at a big podium and afterwards, I was sure I’d nailed it. They had made a tape recording—the first time I’d ever seen one of those big reel machines—which she played for my class. I was mortified at hearing my own voice but so proud that it wasn’t one of the popular kids who’d been picked, only little me. Unfortunately, no one in my family thought to take a photo of the finished product.

Still, I’m pretty sure those books, movies, and ultimately, that project instigated my interest in the Middle Ages, in the spectacle of art history, and especially in the gloriously inaccurate and dramatically histrionic recreations of Medievalism. Perhaps it even led to my focus on the historiography of the period; an interest in the longue durée and the way others before me have imagined that past. Although I wrote my dissertation on a manuscript as it was made around 1000, my books have focused on afterlives: the dismantling, excavations, presentation, and ongoing celebrations at the Abbey of Cluny,[1] on the adventures of Françoise Henry while digging up the past in Ireland,[2] the long-term project that resulted in the many series of Zodiaque books on Romanesque Art and their impact on cultural heritage around Europe,[3] the politics of neo-Romanesque churches,[4] modern-day museums of medieval art,[5] the influences of France on Victorian medievalism,[6] and so on.[7]) We are always shaping our vision of the historical periods that fire our imaginations and we change that vision according to what we have seen and read about the past but also what we need in our lives during the present. What did I know and need in 1960s Los Angeles? How was my vision created? Maybe it was the nuns recounting saints’ lives: St. Bernadette, for whom our parish was named, with her visions of the Virgin at a grotto;[8] St. Teresa of Lisieux “the Little Flower”, my middle name and patron saint, in her gloriously romantic slow death from TB;[9] Joan of Arc (whom I realized later had a variant of my own first name), believing she had been called by God to save France in knight’s armor.[10] I was the stupid little sister by 6 years, the kid who wore glasses already in second grade, the one with the older/unattractive mom, the one whose dad had to work outside 12 hours a day/6 days a week all year without a vacation, the girl with frizzy/wavy brown hair during a fashion obsession with straight and blond. Was I dreaming of empowerment, of fame and success and acceptance? Although my Middle Ages later became less flamboyant, it did lead to a career in the classroom, invoking history for new audiences, and scholarship in the art-historical field. My focus on Romanesque architecture may recall the little church attached to the castle in my model–I didn’t know how to make ogive arches or flying buttresses so I made a simple little chapel with round-arched windows and door, open to a tiny altar inside covered with a white cloth. I wish I’d somehow kept it, at least, but I have no idea what happened to the entire project. Too big to keep in the house, I suppose my mom quietly tipped it into the bin or perhaps it was more dramatically shoved into the incinerator we still had in those days in our backyard and burned up as if the Vikings had swept through our neighborhood.

Original dust cover for French edition of La Forêt de Quokelunde by Michel Rouzé (Paris: Editions Bourrelier, 1953).

Interior illustration showing the children under Mont Saint-Michel, by Pierre Belvès from La Forêt de Quokelunde.

Dust cover on 1964 American edition (New York: Viking Press) of A Traveler (sic) in Time by Allison Uttley (1939).

Interior illustration of Mary, Queen of Scots by Phyllis Bray from A Traveller in Time by Allison Uttley.

Interior illustration of the market fair, by Phyllis Bray from A Traveller in Time.

References

| ↑1 | Janet T. Marquardt, From Martyr to Monument: The Abbey of Cluny as Cultural Patrimony (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007; pb, 2008); Janet T. Marquardt,“Celebrating the Medieval Past in Modern Cluny: How popular events helped shape collective memory for a small French town,” in: Elma Brenner, Meredith Cohen and Mary Franklin-Brown, eds., Memory and Commemoration in Medieval Culture (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2013). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Janet T. Marquardt, ed., Françoise Henry in Co. Mayo: The Inishkea Diaries edited, with introduction (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2012). https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T2220325. |

| ↑3 | Janet T. Marquardt, Zodiaque: Making Medieval Modern 1951-2001 (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2015); Janet T. Marquardt, “Rouergue roman: Zodiaque’s Conques,” in: Ivan Foletti and Adrien Palladino, eds., Conques Across Time. Inventions and Reinventions 9th–21th Centuries (Rome: Viella, 2025), 438–469. |

| ↑4 | Janet T. Marquardt, “The Politics of Burgundian Romanesque: Demolition and Construction in Cluny and Mâcon during the nineteenth century,” in: J. M. Mancini and Keith Bresnahan, eds., Architecture and armed conflict: the politics of destruction (Abingdon: Routledge, 2015), 165-181. |

| ↑5 | Janet T. Marquardt, “Medieval Art Collections,” in: Conrad Rudolph, ed., A Companion to Medieval Art, 2nd ed., (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2019), 933-955. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119077756.ch38. |

| ↑6 | Elizabeth Emery and Janet T. Marquardt, “Resonances in France,” in: Joanne Parker and Nick Groom, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Medievalism (Oxford: OUP, 2020), 303-324. |

| ↑7 | Janet T. Marquardt and Alyce A. Jordan, eds., Medieval Art and Architecture after the Middle Ages (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009; pb 2011. |

| ↑8 | Ruth Cranston, The Miracle of Lourdes (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1955); Ruth Harris, Lourdes: Body and Spirit in the Secular Age (Harmondsmith: Penguin Press, 1999); Suzanne K. Kaufman, Consuming Visions: Mass Culture and the Lourdes Shrine (Ithaca: Cornell, 2005). |

| ↑9 | Thèrèse of Lisieux, Autobiography of St. Thèrèse of Lisieux, trans. Ronald Knox (New York: J. P. Kenedy & Son, 1958); Thèrèse of Lisieux, Story of a Soul: The Autobiography of St. Therese of Lisieux (the Little Flower) trans. John Clarke OCD (Bar-le-Duc: Oeuvre de St. Paul, 1898; Washington, DC : ICS, 1996) ; Monica Furlong, Thèrèse de Lisieux (New York: Virago/Pantheon, 1987). |

| ↑10 | Marina Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1981); Helen Castor, Joan of Arc: A History (New York: Harper, 2015. |