Derrick Austin is the author of Tenderness (BOA Editions, 2021), winner of the 2020 Isabella Gardner Poetry Award, and Trouble the Water (BOA Editions, 2016). His third collection, This Elegance, is forthcoming in Spring 2026. A Cave Canem fellow, he is the recipient of a Ron Wallace Poetry Fellowship, a Stegner Fellowship, and an Amy Lowell Poetry Traveling Scholarship. He has had poems and essays commissioned by The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, The New Museum, Craft Contemporary, The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Arts, The Brick (formerly LAXART), and The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.

Recommended citation: Derrick Austin, “Medieval Ekphrasis,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/PLUZ7100.

Visiting American museums, I’ve found medieval galleries tend to be one of the quietest and least trafficked. All that allusion, maybe. All that blood. All that Jesus—and not the sculpted, Renaissance Jesus but more difficult depictions at once too otherworldly and too bodily. I’m amazed by people who have an easy intimacy with the divine. As a Black, homosexual given to bouts of depression in a profoundly anti-Black and homophobic country, intimacy has often been fraught. Love has never been easy or simple. And isn’t Jesus Love itself?

Last spring, I visited The Cloisters for the first time in nearly a decade. The city had been strangely cold that week but on our walk the sun was bright and hot. My friend had never been before. We called it our pilgrimage. In the Cuxa cloisters, we took pictures of each other taking pictures of flowers. There were tulips the color of dry wine that I loved best. On plain tables, there were cuttings of plants commonly grown in medieval gardens. Some poisonous species grew in nearby pots.

The Unicorn Tapestries were woven in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries. The unicorn poses, flees, thrusts, and bleeds. Each wool tapestry is large and dizzyingly detailed. We were taken by the hunters’ clothes, the time lavished on a shining boot. One of the men, turned just so as if to flaunt his sleeve’s blue folds, charmed us. Look at me, he said. See me here in this moment in the world.

Even when I’m not writing about visual art, it informs my poems. I have a passion for art, particularly religious works and European paintings. I delight in their beauty. I’m awed by the labor required to create these objects. They refine my thinking about poetic form. What I love best about ekphrasis (writing about visual art) is that it’s an encounter between the viewer and the object. The ekphrastic poem isn’t the painting, it’s the space between, where the viewer brings to bear their history and position in the present with the history of that painting. The poem is what can’t be seen.

In an interview with The Paris Review, Anne Carson reflects on churchgoing despite not being particularly devout: “A kind of thinking takes place there that doesn’t happen anywhere else.” Looking at Simone Martini, for example, my mind feels liberated. When I’m in a quiet gallery, attentive to an artwork, not rushed, letting my mind wander and wonder, I feel a physical charge that I imagine must be what people feel when they pray. I didn’t grow up going to church. I don’t have a regular spiritual practice, but I’m still invested in the questions religious belief raises. I think they’re worthwhile questions because often, distilled, they are questions of intimacy, selfhood, origin, and power. We all seek after answers. Poems rarely answer anything for me, but they’re an excellent engine for questions and supposition.

My poem “Catacombs of San Callisto” is a poem of queer intimacy and devotion between sightseeing lovers. Those catacombs contain some of the earliest Christian art when depiction was slippery and vexed, when Jesus was a beardless youth like Apollo. “Byzantine Gold” unfolds beneath the authoritative eyes of Christ Pantocrator. I’ve desired men with those eyes. I like that Jesus can be hieratic and distant. I like that Jesus can have a physical body like ours, a beautiful body, a wounded body. I like that depictions of Jesus can be sensual and weird and frightful and opaque. I’m awed by medieval artists, their thorny and intelligent designs.

Illumination

Witness the monk

tracing figures

on bright, empty pages.

Shine and color rise

like mist

in meticulous outlines,

his path illumined by

a dribbling candle

Wanton overgrowth,

spriraling arabesques,

the works of his

hands blossom

on both pages: split pomegranates

(cinnabar pigment,

iron rich), a lattice

of jade leaves (lapis worth more than

a year’s wages)

and rose gold shocks

of bougainvillea. His garden

is the centerpiece.

Hares and falcons

and the gentle flick of

his brush,

white for a hind’s tail;

cows graze flat fields (perspective

as yet unknown).

And all these are named,

as when Adam reared and ranked

their tribes,

for a prince’s solitary pleasure,

each beast and blossom.

Every page gilded

as if to pollinate

those fingertips. And this

is but one page, one page

in a book of praise.

The monk inks the owner’s likeness

in a green cloak

lined with gold leaf

to echo the landscape

(the body politic

easy parable for a boy). But this garden

is very real. See there,

how the monk

bearded and wiry, inserts himself

and points to the adjacent page?

A flaming sword.

Two figures

evicted from their green shade.

The vellum

supple as with her tears.

Both cover their nakedness

with a banner,

he holds the word humus

and she, hubris.

Written

on the flesh.

The ash and soot of a

book burning

just under her foot

as if ruin made our shadows.

Fan, Silver, 6th century CE, Aleppo (Syria), Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

Imagine the pages of illuminated manuscripts turned by an anxious lady or penitent lord. Knowledge worth its weight in gold and precious stones. Imagine reaching for a fan on a sleepless, summer night. A seraph visible in moonlight.

Catacombs of San Callisto

He’s never Himself in the earliest frescos:

the shepherd boy guarding the sallow lamb

whose fleece might hide the god. Or the fish

and bowl of loaves. Or the phoenix.

He isn’t Himself, yet I trust Him.

I’ve walked alone with a man in the dark

and made much of his body—

you’re with me now, touring the nests of the dead.

We’re told by books old as these walls:

Filthy, our bodies, yours and mine. Not so.

When we love, we take each other in

like living water until warm

plaits of air unbraid in our throats.

The early artists did not turn up their noses

to flesh and, in this way, honored

the putrefying bodies in their midst

and painted the signs by which their bodies

would be watched and known.

The liquid issue smeared the frescos

with scents of urine and blood.

I would gladly shame myself in this way for you.

I would be the good shepherd

above your body in its cold, stone niche

not only because I believe

in the resurrection of the body, but because

I want to be the face that welcomes you

to that inordinate dark.

Adam, lle-de-France, about 1260, Lutetian limestone, traces of polychromy From Notre-Dame de Paris, reverse of the southern facade of the transept, Musée de Cluny.

Shame seems utterly absent from this Adam’s world even while clutching the cartoonish leaf. It’s wholly medieval yet it echoes the Classical past. He reminds me of Milton’s Adam in Paradise Lost, a sweet fool.

Byzantine Gold

A chain of blue-white chips mimics waves

pleating

around Christ’s body. Owl-eyed saints

draw light on the western wall.

Despite

centuries of votive smoke,

the shining ranks of prophets gesture,

elegant

as sommeliers, toward mosaic scrolls

and would have you consider the honeycombed

geometry

of paradise—dome, arch, and column—

with its air of permanence,

above penitent

and tourist, above the fray

of ethnic cleansing we’d like to believe:

a Balkan

landmine planted near trillium,

the scarred field, the ghost limbs of olive trees,

and the boy

there, I mean, he’s a man now,

about my age, passing us on his prosthetic leg—

that which was

sundered brilliantly shining—though

he might have been a child when he lost the limb.

Think invention.

Think miracle. To think someone, Doctors

Without Borders, maybe, could make a man whole again.

But look:

a mortar leveled Gethsemane,

Visigoths defaced the deposition, and,

her turquoise

hem unraveling, poor Mary’s going to pieces,

pocked by shrapnel from a mislaid bomb.

If the dome

cracked open, what a dry comb it would be.

We consider paradise anew despite its stone

indifference

to time. Christ Pantocrator, alien, severe,

claims the apse, suspended in gold

leaf, apart

from and a part of the world, the dust

those semi-precious stones become. We would find

comfort

in his Renaissance flesh,

its bordello-shades of pain—the oils

of the canvas

like the oils of the body—but where

would we find warmth beneath these glass eyes,

radiant,

petrifying? His gaze arrests us

like everything we make, which is touched

with our image:

metals and mirroring glass

in mortal shapes, even the minefield,

visionary

in its violence—God before Sodom

would be amazed by such force. The mind

itself

drips rough honey and gilds the world.

Christ Discovered in the Temple, painted in 1342, Simone Martini (about 1284-1344), Tempera on wood panel, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool.

Simone Martini, renowned for his elegant forms, is perhaps my favorite painter of the Virgin Mary. He often depicts Mary’s all-too-human agitation. I laugh looking at Mary and Joseph in this intimate panel painting because parents have been giving that same disciplinary look for centuries. In a field of gold indebted to Byzantine icons, Martini renders the sacred world of the Gospels with psychological precision and good humor.

Art Restorer

What are these figures up to? Who knows.

It’s hard to read a weathered expression.

In an apron, I arrange my tools in rows:

cotton swabs to clean faded, celestial hose,

a scalpel for wax on a distant mountain.

What are these figures up to? Who knows

if angels can curse or grieve Golgotha’s woes.

Leading our gaze, accessories to Magdalene

and Christ, they show us what to feel. Suppose

they look like us, their faces a lost reflection?

What are these figures up to? Who knows.

The panel cracked from heat. An x-ray shows

patterns in the wood I preserve or recondition.

Picture its candlelit past: a draft blows

against chafed pilgrims wrapped in sheepskin.

Recovering the shades and shadows

of different eras and other worlds, I imagine

I do good work here. At last, this corner glows.

Centuries of varnish dissolve. Sickly yellows

leave Mary’s face. Her eyes are wet and sanguine.

originally published in American Literary Review

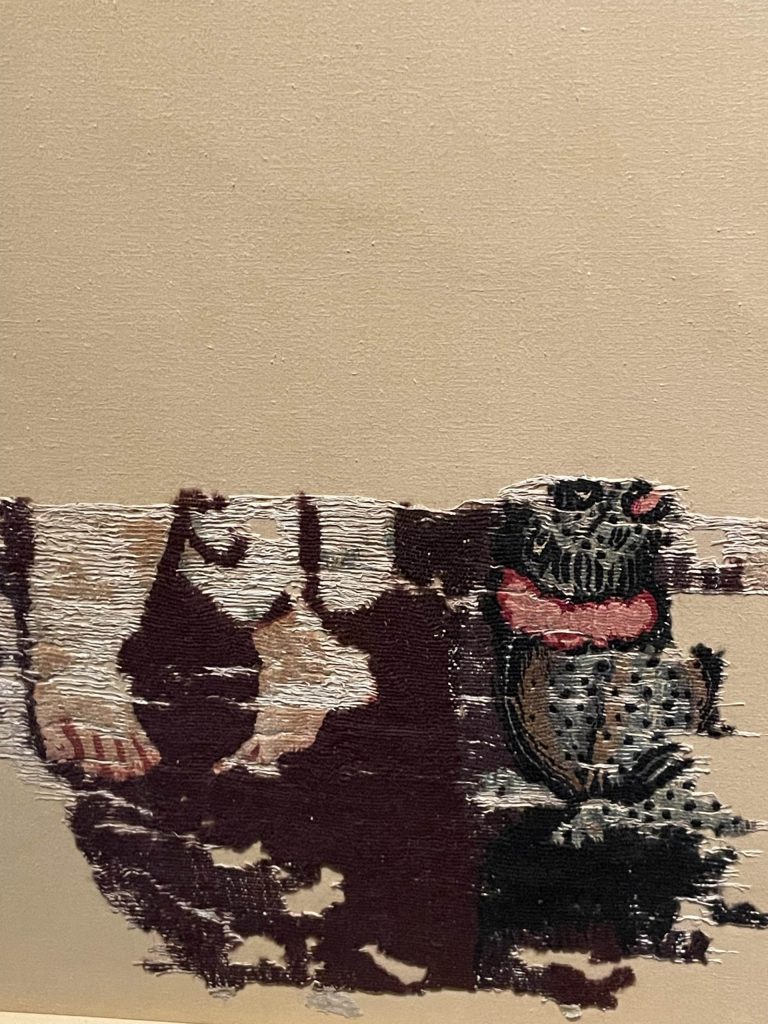

Fragment of a hanging representing the god Dionysos under an arch (detail), Egypt, Late Roman-Early Byzantine Period,

4th-early 5th century, Tapestry weave of dyed wools and undyed linen, MFA Boston.

And sometimes the past can’t be restored. This is no problem for the god of wine and ecstasy. Still he dances separated from his feet.