Looking at Gleaning

Several of us have been talking about slow looking, of late, including me, a term that I think probably borrows from the “slow food” movement. I found myself connecting food and art and slowness in my mind, listening, of all things, to a story on NPR about the recent trend toward a sort of postmodern gleaning. For example, a new organization, purportedly inspired by the so-called “Old Testament,” is working to help solve hunger by reviving the practice of gleaning.

According to an NPR report, 96 billion pounds of pre-consumer food goes to waste. This is clearly a terrible thing, since almost 50 million Americans do not have enough to eat. There is a ton of waste—actually, surely millions of tons—not only of food, but also of fertilizer, water, and so on that has been used to produce food that will go uneaten by, say, the 16 million hungry children in the US. Sarah Ramirez is trying to do something about this. She (like me!) did a Ph.D. at Stanford and then (unlike me) became the epidemiologist for Tulare County, in CA’s often forgotten Central Valley (hint: it is likely that every bit of produce you ate today was grown there), but she recently quit this to start a small non-profit gleaning this would-be wasted food. She and her husband lead a small number of volunteers to pick the food that would rot. This is a wonderful thing, of course. The hungry are eating, and eating more healthy foods, as well, which might help combat the rising levels of diabetes in the rural poor communities where Ramirez is focusing her efforts

But thinking about this has me troubled, as well. And this is where we get back to art, and to a bit of slow looking. In this case, I want to write a bit about a painting (I’m sure you’ve guessed which) that I have been looking at, thinking about, and reading essays on for several years: Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, painted in 1857 and now housed in the Musée d’Orsay (where I’ve had the privilege of viewing it, several times). The image shows three women—poor peasants—in the foreground, stooped over, picking up the stray bits of grain left behind by the harvest. In the background, a rich harvest is occurring. There are massive haystacks and heaps of wheat, and a crowd of harvesters all working under the watchful eye of a mounted overseer (tiny, by the horizon, on the right).

But thinking about this has me troubled, as well. And this is where we get back to art, and to a bit of slow looking. In this case, I want to write a bit about a painting (I’m sure you’ve guessed which) that I have been looking at, thinking about, and reading essays on for several years: Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners, painted in 1857 and now housed in the Musée d’Orsay (where I’ve had the privilege of viewing it, several times). The image shows three women—poor peasants—in the foreground, stooped over, picking up the stray bits of grain left behind by the harvest. In the background, a rich harvest is occurring. There are massive haystacks and heaps of wheat, and a crowd of harvesters all working under the watchful eye of a mounted overseer (tiny, by the horizon, on the right).

This painting is one of the options for a student assignment in an art appreciation course I teach regularly. They are to just supposed to perform a straightforward visual analysis of the painting, but of course all sorts of assumptions creep in around the edges. Perhaps the most common of these is that they refer to the women as “African-Americans” or “slaves,” indicating that they haven’t paid much attention to the context for its production (19th century France). Nonetheless, they unintentionally comment on the exploitation of the rural poor. Not once, though, out of several dozen essays, has a student mentioned those mighty haystacks in the background, and the contrast of their mounded forms with those of the women in the foreground (though should their googling bring them to this post, surely this will become a regular feature of said essays).

This painting is one of the options for a student assignment in an art appreciation course I teach regularly. They are to just supposed to perform a straightforward visual analysis of the painting, but of course all sorts of assumptions creep in around the edges. Perhaps the most common of these is that they refer to the women as “African-Americans” or “slaves,” indicating that they haven’t paid much attention to the context for its production (19th century France). Nonetheless, they unintentionally comment on the exploitation of the rural poor. Not once, though, out of several dozen essays, has a student mentioned those mighty haystacks in the background, and the contrast of their mounded forms with those of the women in the foreground (though should their googling bring them to this post, surely this will become a regular feature of said essays).

There are even three sets of three mounds, as if Millet is trying to make sure that we can’t miss the comparison of abundance and want. The main set of three mounds is to the left, where the leftmost is the highest, and then the other two are gradually lower, as if reversing the positions of the three gleaners. The rightmost mound of grain is therefore in a position analogous to, and also directly above, the leftmost gleaner. Its flattened summit is topped with a few strokes of whitish paint, suggesting human figures at work stacking the grain yet higher. The woman, in contrast, holds a few stalks of grain on her flattened back.

There are even three sets of three mounds, as if Millet is trying to make sure that we can’t miss the comparison of abundance and want. The main set of three mounds is to the left, where the leftmost is the highest, and then the other two are gradually lower, as if reversing the positions of the three gleaners. The rightmost mound of grain is therefore in a position analogous to, and also directly above, the leftmost gleaner. Its flattened summit is topped with a few strokes of whitish paint, suggesting human figures at work stacking the grain yet higher. The woman, in contrast, holds a few stalks of grain on her flattened back.

How to read this? Where grain is abundant, people are superior—literally—to it, but where it is absent in sufficient quantity, it is tramples down the people who depend on it for their sustenance. This woman is bent over double to reach out for another bit of grain, but her left arm, clutching what she has so far gathered, is wrenched around, as if gripped by a person twisting it behind her. But, of course, it is not a person who forces her downward, presses her toward the ground—it is the grain, itself. Or is it?

How to read this? Where grain is abundant, people are superior—literally—to it, but where it is absent in sufficient quantity, it is tramples down the people who depend on it for their sustenance. This woman is bent over double to reach out for another bit of grain, but her left arm, clutching what she has so far gathered, is wrenched around, as if gripped by a person twisting it behind her. But, of course, it is not a person who forces her downward, presses her toward the ground—it is the grain, itself. Or is it?

She is the leftmost figure in the image. Across the canvas from her, toward the right edge, is another figure. As the Musée d’Orsay informs us:

“The man on horseback, isolated on the right, is probably a steward. In charge of supervising the work on the estate, he also makes sure that the gleaners respect the rules governing their task. His presence adds social distance by bringing a reminder of the landlords he represents.”

“The man on horseback, isolated on the right, is probably a steward. In charge of supervising the work on the estate, he also makes sure that the gleaners respect the rules governing their task. His presence adds social distance by bringing a reminder of the landlords he represents.”

He extends his right arm forward, holding it straight out before him in a commanding pose.

Were the gleaner to stand, her arm would be in rather the same position. But angle is everything in this work, dominated by the long, flat horizon that emphasizes hierarchical separations of this from that, above from below. The grain, which seems to be what presses the gleaner downward, what seems to draw her companions downward, is not what creates their hunger. There is, those massive stacks in the background remind us, plenty to go around.

Were the gleaner to stand, her arm would be in rather the same position. But angle is everything in this work, dominated by the long, flat horizon that emphasizes hierarchical separations of this from that, above from below. The grain, which seems to be what presses the gleaner downward, what seems to draw her companions downward, is not what creates their hunger. There is, those massive stacks in the background remind us, plenty to go around.

Plenty. They are like Monet’s lovely heaps of hay:

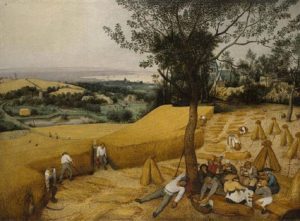

Or like Bruegel’s:

But these two present scenes of plenty. Monet may be disinterested in the human ramifications, but Bruegel is focused on them. His peasants are well-fed—indeed, many of them are actively stuffing themselves, spooning food from bowls, cutting hunks off of massive wheels of cheese, drinking from large vessels.

Millet’s gleaners are hungry, but they don’t starve in a desert. They are surrounded by mighty stacks of grain, while they scavenge the scant leftovers, under the watchful eye of the pointing steward, who “makes sure that the gleaners respect the rules governing their task.” That is, he makes sure they stay in the foreground, in the lower half of the painting, where the field is largely barren, where the grain has been cut down to little nubs that Millet has highlighted as vertical slashes against the darkened patch at the lower edge.

The gleaners’ hunger, their pain, their bent backs are pressed down not by the grain but by the overseer, and the human powers he represents, by social injustice and inequality of the sort that was supposed to be ended by the Revolution three-quarters of a century earlier.

The gleaners’ hunger, their pain, their bent backs are pressed down not by the grain but by the overseer, and the human powers he represents, by social injustice and inequality of the sort that was supposed to be ended by the Revolution three-quarters of a century earlier.

This brings me back to the modern gleaners, like the Stanford Gleaning Project (“Gleaning from the Privileged and Donating to Those in Need,” not affiliated with Ramirez, as far as I can tell). And like the man sitting beside me on a flight several months back, who identified himself as a gleaner who flies around the country (admittedly in coach) to harvest unwanted food, which he then ships back to the collective with which he lives. Again, fine.

But some straw seems stuck in my craw. Part of it is the term, itself. These modern “gleaners” are either, like my airline-traveling neighbor, gleaners by lifestyle choice, or self-described privileged folks, gleaning for those in need. None of these know the pain and fear and exhaustion and hunger of the figures in Millet’s arresting image.

The second problem (and thanks to Martha Easton here!) is that, while the three gleaners in Millet’s painting are anonymous, they nonetheless occupy the foreground of the painting, indeed they dominate it. Unlike so many peasants depicted throughout the history of art, these three are the main point of the painting, and are not there to be mocked or romanticized. The focus stays resolutely on them—my students have never commented on the overseer on his horse. Indeed, I don’t think a single one has acknowledged that there are other figures in the image, at all. In contrast, the focus at least of the news stories about these certainly worthwhile modern gleaning projects stays resolutely on their named founders. Those who assisted through their volunteer labor, and those who are assisted by it, remain generally anonymous, relegated to the background.

The final part of my concern is that gleaning was and should be an act of desperation, not a plan for social change. Indeed, it is a plan for social stasis. The farmers (really, multinational agribusinesses) will keep overproducing, and the poor will continue to be poor and hungry. Some—really, a tiny fraction—will eat better, and this is something. It is real and it matters for them. But gleaning is not social progress. A slow look at Millet’s painting, at the bent bodies, stooped and heavy with exhaustion, their fingers thickened by a lifetime of work and red and raw with their gleaning should remind us of that.