Elizabeth Pastan • Emory University

Recommended citation: Elizabeth Pastan, “It Ought to be Mary: Themes in the Western Rose Window of Notre-Dame of Paris,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/FRYZ5161.

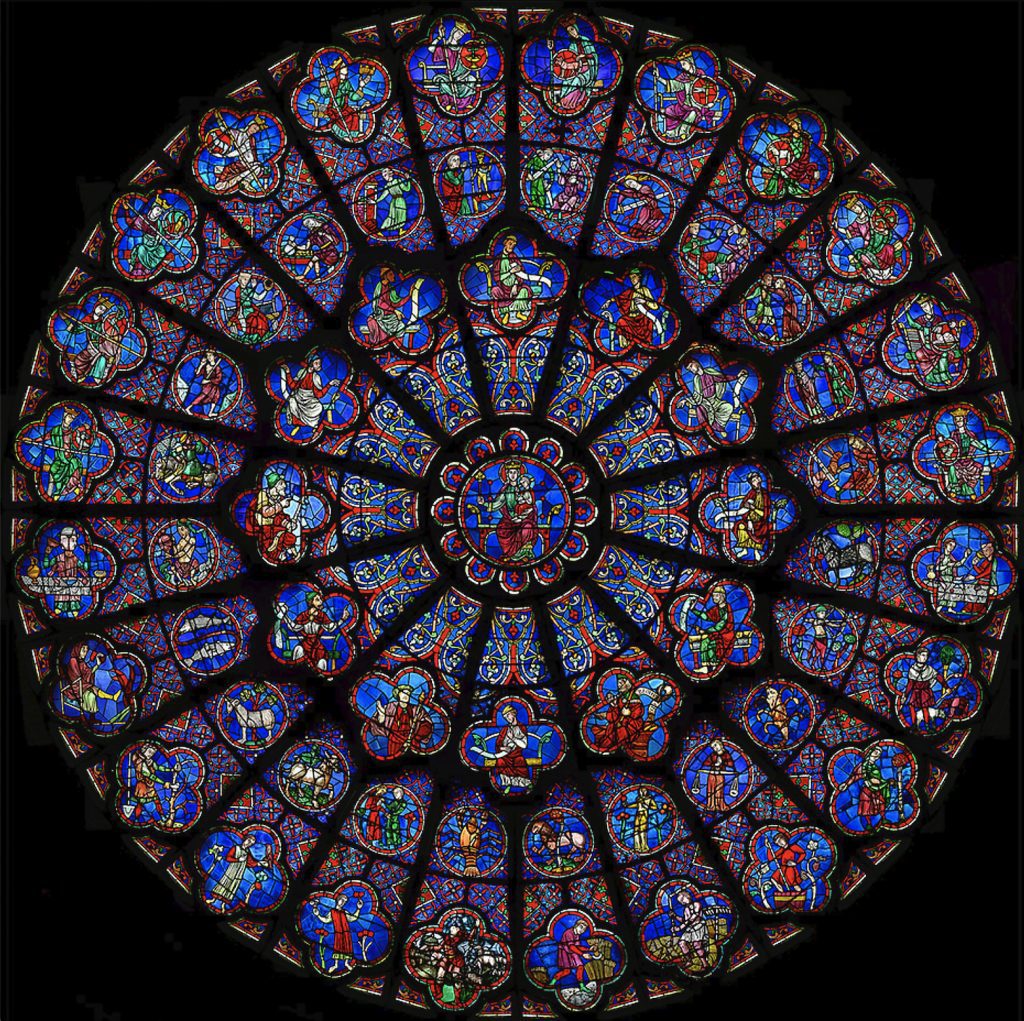

Rachel Dressler is a scholar who has always been willing to critically reevaluate traditional iconographic explanations, and that is one of the reasons I found it so stimulating to organize the College Art Association session, “Reassessing the Legacy of Meyer Schapiro” with her.[1] In tribute to Rachel’s spirit of inquiry, in this paper I will reexamine themes in the western rose window of Notre-Dame of Paris, which is the large circular aperture with stone traceries designed to hold stained glass at the center of the cathedral’s entrance façade (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Exterior view of Notre-Dame of Paris from the west, with the rose window of c. 1220, photo taken before the fire of 2019 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Peter Haas, CC BY-SA 3.0).

In investigating the window, I was struck by the assumption that the lost central medieval motif of the rose had to have been then, as it is now, the Virgin and Child (see Fig. 2). Since the cathedral is dedicated to the Virgin Mary – or Notre Dame as she is known in French – her depiction at the center of the rose window would not be unexpected. Yet themes in the extant medieval stained-glass panels of the rose window as well as twelfth-century precedents also introduce other intriguing possibilities. This context led me to pose the question at the heart of this contribution: what would the earliest rose window of the cathedral of Notre-Dame of Paris look like if the modern image of Notre Dame were not at its center?

The Parisian cathedral is generally dated c. 1163-1250, corresponding to the Gothic structure’s first major phase of construction.[2] At thirty feet taller than prevalent medieval buildings such as the cathedrals of Laon and Canterbury, Notre-Dame’s size demanded new strategies as well as continuous and costly revisions.[3] The cathedral was also the subject of a contemporary critique by its precentor, Peter the Chanter (†1197), who decried the “superfluity” of such tall and expensive structures, observing that their costs were unfairly borne by the poor.[4] The large rose windows positioned over the major portals of the building celebrate the cathedral’s height and structural daring, but also draw attention to the expense of the undertaking, as accounts from the abbey of Saint-Denis reveal that the glazing of the building cost as much as the structure itself.[5]

Although the cathedral of Notre-Dame was once illuminated by approximately 200 medieval stained-glass windows, most of these were destroyed in campaigns of modernization undertaken in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[6] The stained-glass artist Pierre Le Vieil (1708-1772) claimed to have removed the last of Notre-Dame’s medieval windows in 1741 at the direction of its clerics, and recorded the event for posterity in his history of the medium of stained glass, in an account that is at turns poignant and justificatory.[7] Thankfully, however, medieval stained glass in the cathedral’s three rose windows undertaken between c.1220-60, which encapsule major developments in Gothic design and technology, survived both Le Vieil’s interventions and the recent fire of 15 April 2019.[8]

The western rose that is my focus is the smallest and earliest of Notre-Dame’s rose windows at 9.60 meters or 31 ½ feet in diameter. It was probably completed by c. 1220, and set in place near the end of the first building campaign.[9] It offers pictorial imagery in proportions designed to draw the beholder in, and this imagery takes up themes also present in the carvings of the western exterior portals. On the interior, the rose window is usually partially concealed by the pipes of the modern organ located in front of it.[10]

Figure 2. Interior view of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris of c. 1220 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Eric Chan, CC-BY-2.0).

But even in this view, the restored image of the Virgin and Child seated at the window’s center, surrounded by concentric rings of imagery, can be distinguished. In contrast, Notre-Dame’s transept roses belong to a later phase of the cathedral’s expansion from the mid thirteenth century; at 13 meters or about 42 feet in diameter, these later rose windows undertake an ambitious evacuation of the wall, and their scale alone demanded a reconceptualization of the windows’ contents (contrast Figs. 1 and 3).[11]

Figure 3. View of Notre-Dame of Paris from the south, with its rose window of c. 1260, photo taken before the fire of 2019 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, sacratomato_hr, CC-BY-SA-2.0).

Related to the question of the image at the center of the cathedral’s western rose window is the issue of the nature of Marian devotions at Notre-Dame of Paris. In the early Middle Ages, the Virgin Mary was treated with a certain reserve as the instrument of redemption through her son. As Anna Russakoff has recently outlined, although the liturgical feasts and ecumenical decrees that define the cult of the Virgin date to early Christianity, “it was in the high and later Middle Ages that Marian worship flourished most fully in western Europe.”[12] In works of art from the critical juncture of the later twelfth century and early thirteenth centuries – precisely when the Gothic rebuilding of Notre-Dame of Paris was undertaken – Mary began to appear as a subject in her own right.[13] Her appearance as the focal point of the western rose window over the central portal of Notre-Dame, which has a medieval sculptural program with Christ at its center, would thus constitute a relatively recent development and should not be taken for granted.[14] Devotion to the Virgin Mary is such an important aspect of later medieval theology that it is tempting to read her prominence back into the imagery of Notre-Dame’s western facade, but that risks overwriting the complex and interesting ways that Mary became central in medieval devotional art.[15] The Virgin and Child, for example, are unequivocally at the center of Notre-Dame’s north transept rose of c. 1250, in keeping with the Marian emphasis of the imagery throughout the northern choir of the cathedral.[16] But that fact alone raises questions about having an identical medieval subject in the western rose of decades earlier. As Margot Fassler concluded in her study of the contemporaneous monument of Chartres Cathedral, “Mary of Chartres cannot be known without unraveling a made history.”[17]

To address the question of the lost central stained-glass panel of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris, I will turn first to the window itself, examining its scenes and identifying its restorations. Such a critique d’authenticité, or establishment of the window’s state of preservation, is the starting point for any investigation in a medium as fragile as stained glass. Yet it is rarely a straight-forward analysis; among other issues to be weighed is the fact that early modern restorations often preserved the themes of the earlier glass they replaced. After examining the condition of the western rose and identifying its medieval contents, I will then investigate other examples of the Parisian rose window’s unusual themes in earlier mosaics, stained glass, and manuscript illuminations. Since we may never know for certain what originally occupied the center of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris in the early thirteenth century, these comparanda allow us to explore a fascinating and understudied chapter in later twelfth-century devotional imagery. The central image of the western rose may or may not have been Mary, but inquiry into the thematically related materials in works that preceded Notre-Dame will reveal the extent of medieval artistic and devotional invention, thus further opening up the realm of possibilities for the center of the Parisian window.

The Western Rose Window of Notre-Dame of Paris

Given the status of Notre-Dame’s rose windows as the only surviving examples of medieval glass in the cathedral and their just fair state of preservation,[18] earlier scholars made a virtue of necessity by emphasizing broad themes in each of the Parisian rose compositions, and then discussing a few of the better-preserved medieval panels.[19] This broad thematic approach to the cathedral’s three rose windows was far better suited to the content of the later transept roses – which make their impact through scale, luminosity, and enumeration – than to the complex combination of pictorial subjects joined in the western rose of decades earlier. This state of affairs may have contributed to the presumption that the western rose window’s central subject was the Virgin and Child.

The analysis of the condition of the western rose window of Notre-Dame begins with Ferdinand de Lasteyrie, who wrote the earliest extant detailed description of the cathedral’s windows in 1857. Significantly, he did not recognize the western rose as a Marian window.[20] Although his identification of the rose as a Tree of Jesse window is incorrect, his nuanced discussion is worth examining in detail, since Lasteyrie was at pains to document what the stained glass before him had endured:

Quelques-unes de ces figures ont été détruites, d’autres sont frustes, et toutes ont subi des remaniements nombreux, d’où il résulte que la disposition n’en est plus maintenant bien régulière.

[Some of these figures have been destroyed, others are crude, and all have undergone numerous efforts at reordering, with the result that the arrangement is no longer very homogeneous.][21]

Lasteyrie also remarked on the motif of “some kind of pale sun” then occupying the center of the western rose; he stated that it belonged to one of the window’s most recent restorations,[22] an intervention that probably dated to the installation of a new western organ loft in 1731.[23] Lasteyrie used oblique language to indicate that the image at the center of the rose was probably an image of the Virgin: “Le centre de la rose … devait être occupé par une figure de la sainte Vierge” [The center of the rose … ought to have been an image of the blessed Virgin.][24] Yet with near unanimity since Lasteyrie’s publication, scholars have simply identified the western rose of Notre-Dame Cathedral as a window dedicated to Mary, with the Virgin and Child at its center.[25] Accordingly, I will examine the stained-glass panels in detail, in order to establish the medieval themes within the window.

Figure. 4. Interior view of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris of c. 1220 (Photo by kind permission of Christian Dumolard).

By the count of Jean Lafond, who undertook the critique d’authenticité of the window in 1959, there are at least 35 reasonably well preserved medieval figural panels out of 96 figural subjects in the western rose.[26] Ornament plays an important role in the lush foliate motifs in the center and throughout Notre-Dame’s western rose and is one of the reasons Lasteyrie thought the window was a Tree of Jesse, but in this context, focus will be on the figural imagery. Within the window’s broad themes of time, the cosmos, and the human condition, the remnants of a substantial medieval program can still be discerned (Fig. 4). While replacement panes are found throughout the medieval panels, the varying sizes and shapes of the elements established by the traceries of the window may have helped to safeguard the thematic cohesion of the whole. We will also keep track of the sixteenth-century campaign(s) of restoration, evinced in seven panels that appear to have maintained the medieval content of the rose.[27]

Turning to the second or medial concentric ring of images that surround the modern replacements at the center of the window, there are twelve prophets in quatrefoil compositions of about 3 ¼ feet x 3 ½ feet (1.00 meters x 1.05 meters). The seated prophet in the D-4 quatrefoil, at the 3:00 o’clock position within the circular composition, is one of the few substantially thirteenth-century medieval figures in this ring (Fig. 5). His left hand holds a scroll, while his right hand points emphatically downwards, and though it is a restoration, the direction indicated by his hand may suggest that he had a different placement originally; if he were positioned above the central motif of the rose, the gesture would make more sense.[28] With his large head, elongated proportions, overlapping arms, and fluidly falling drapery, this prophet compares in style to sculptures on the west façade also from the early thirteenth century.[29] The prophets, figures from the Hebrew Bible who foretold the coming of the Messiah, introduce the element of time into the window and would combine well with a number of central motifs including the personification of the Church, an allegory involving the faith, or a Marian subject, as we shall see.

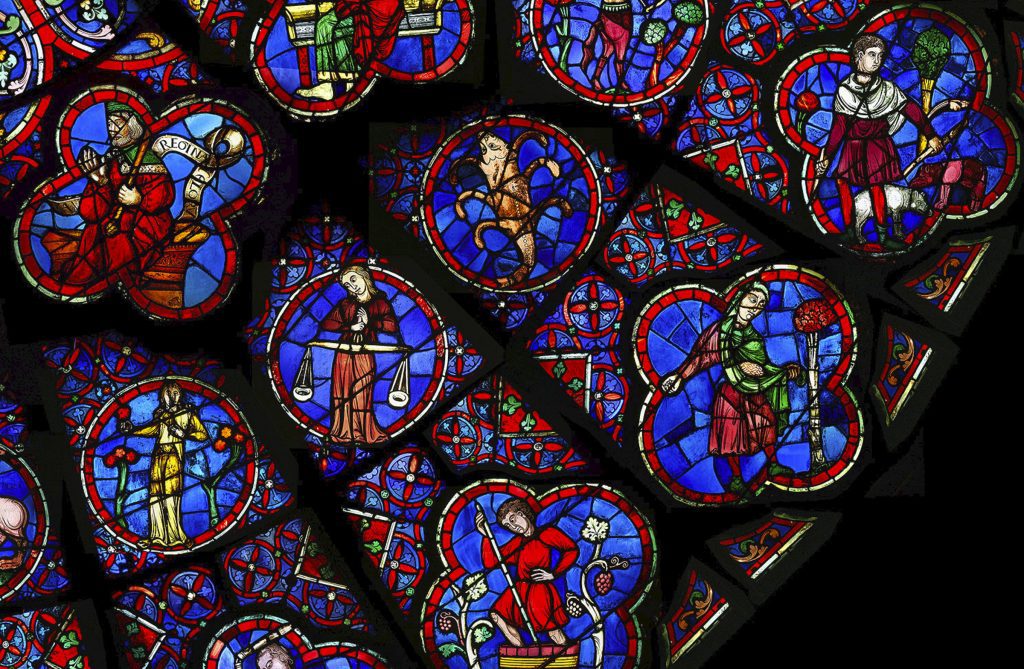

Figure 5. The right portion of western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris, detail of Fig. 4, with thirteenth-century images of the prophet in quatrefoil D-4, with a view of the vice of Cowardice (medallion D-5), and the sixteenth-century sign of the zodiac Capricorn (D-6). (Photo by kind permission of Christian Dumolard).

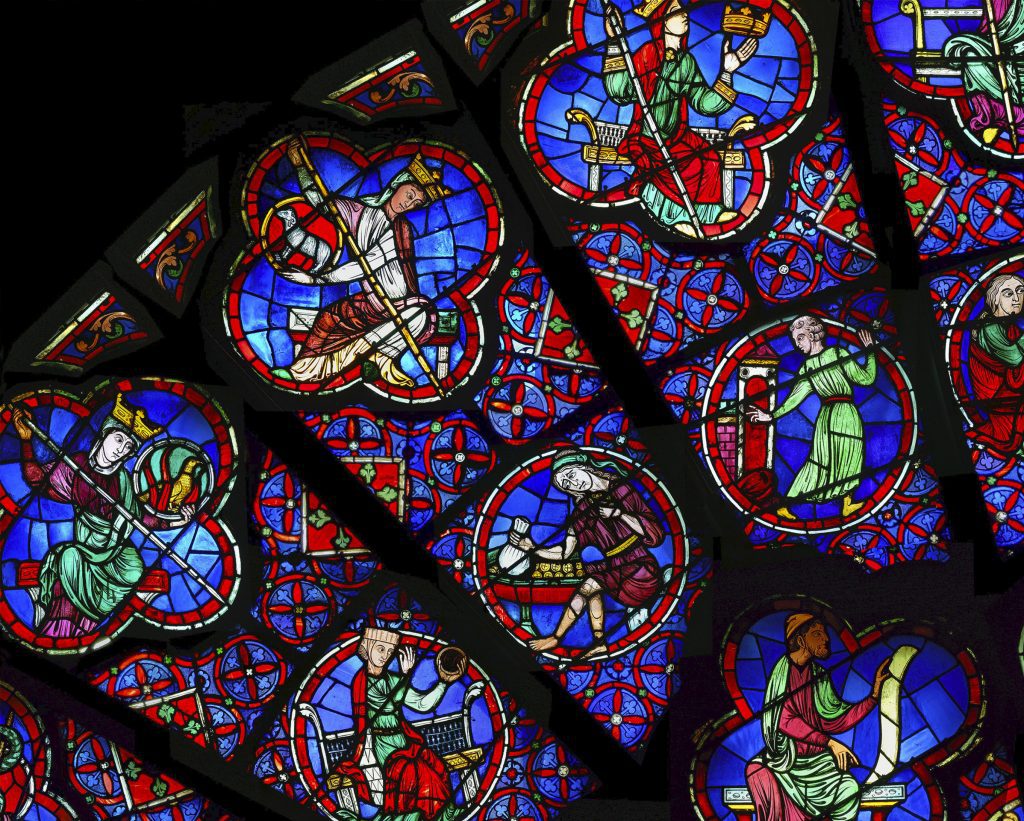

While seven of the prophets in quatrefoils from this ring of the rose window are largely modern, there are also three sixteenth-century restorations.[30] The panel of the sixteenth-century prophet in quatrefoil F-4, at approximately 5:00 o’clock in this concentric row of the rose window (Fig. 6), is particularly interesting. Behind the seated prophet is a dynamically curling banderole with late medieval lettering that reads AV[E] REGINA CELORU[M], or “Welcome, O Queen of Heaven,”[31] a Marian antiphon that celebrates the part the Virgin played in the reopening of heaven to humankind.[32] The prophet’s inscription indicates that the window’s sixteenth-century restorer either found or intuited a Marian subject in the center of the window. Therein lies the quandary: did the early modern restorer respond to or assume that Mary occupied the center of the western rose window?

Figure 6. The lower mid-section of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris, detail of Fig. 4, with the sixteenth-century prophet with banderole in quatrefoil F-4, and the thirteenth-century sign of the zodiac Virgo (medallion F-6) and the month of October sowing grain (quatrefoil E-12). Other scenes, including Libra (F-5), Scorpio (E-6), November felling acorns to feed the pigs (E-11), and September trampling grapes (F-11), are more heavily restored. (Photo by kind permission of Christian Dumolard)

The next concentric ring of images in the western rose of Notre-Dame is justly famous for the twelve small medallions of the vices in the upper half of the window (Fig. 7),[33] and twelve images of the signs of the zodiac in the lower half (see Fig. 6); sadly, these latter are now covered from view by the pipes of the modern organ in the organ loft before the window (Fig. 2).[34] At 0.70 meters or about 2 1/3 feet in diameter, the medallions of this ring of the rose are smaller than other elements in the western rose window’s composition, and are evidence of the complex coordination of the pictorial elements within the framework established by the window’s traceries. The medieval personification of Cowardice (D-5) is among the best-preserved medieval images (Fig. 5, upper right).[35] The medallion shows a Monty Pythonesque male figure dropping his sword as he flees a rabbit, who is nearly the size of his human quarry.[36] The fleeing man has wonderful torsion as he turns his large head back towards the menacing rabbit while his outstretched arms and widely spaced feet signal the direction of his flight out of the frame. There are also three sixteenth-century medallions from this series, including the image of Capricorn (D-6), visible below Cowardice (Fig. 5, lower right).[37]

Figure 7. The upper mid-section of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris, detail of Fig. 4, with images of the vices from the upper half of the window (left to right): Luxuria (K-6), Avarice (L-5, well preserved), Inconstancy (L-6, modern), Idolatry (A-5), Anger (A-6), Despair (B-5), Ingratitude (B-6), and Discord (C-5) (Photo by kind permission of Christian Dumolard).

The outer concentric ring of the western rose’s composition features the twelve virtues in the upper half of the window (Fig. 7), and the twelve labors of the months in the lower half (see Fig. 6). These quatrefoils, at 1.10 x 1.10 meters, are comparable to, but slightly bigger than those of the prophets in the inner medial ring of the window.[38] The well-preserved and dynamically posed figure of Charity aims her lance like a javelin at Avarice in the concentric ring beneath her (Fig. 8), thus showing the interaction between the images in the different registers of the medieval composition and further underscoring the complex network of imagery established by the window’s traceries. Once again, there are two sixteenth-century panels that complete the series.[39]

Figure 8. The upper portion of the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris, detail of Fig. 4, with views of the Virtues of Chastity (K-12), Charity (L-11, well preserved), and Perseverance (L-12, well preserved) and the vices of Luxuria (K-6), Avarice (L-5, well preserved), and Inconstancy (L-6, modern) (Photo by kind permission of Christian Dumolard).

While the scenes of the zodiac and labors of the month in the lower half of the window extend the cosmological significance of the window, the virtues and vices in the upper portion of the window address the human condition and connect to contemporaneous teaching at the University of Paris. This movement is sometimes dubbed “the biblical moral school,” because scholars such as Peter the Chanter (†1197) and his circle sought to explore scripture through practical moral questions.[40] As Emily Corran has recently emphasized, the casuistical method these scholars employed in the classroom consisted in selecting ambiguous cases for discussion and pursuing their moral and ethical implications.[41] As we shall see, the scenes of the virtues and vices in the western rose echo those of the eye-level exterior reliefs on the central doorway, thus giving these images further emphasis.

The thematic content of the medieval stained-glass panels remaining in the western rose window of Notre-Dame of Paris – including scenes dealing with time, the cosmos, and the human condition – allows considerable scope for its lost medieval image. Yet is it important to emphasize that a central Marian motif remains conceivable. Given the number of panels from an early modern campaign of restoration and the way they appear to maintain the thirteenth-century medieval program in panels of the prophets, vices, labors of the months, and signs of the zodiac, the sixteenth-century prophet with a Marian antiphon in his accompanying inscription (Fig. 6) provides more compelling evidence for a Marian subject at the window’s center than it might appear at first. Moreover, carvings involving the seasons, labors of the month, and signs of the zodiac in the northern portal of the west façade of Notre-Dame’s exterior reliefs have been associated with the cult of the Virgin.[42] To pursue these possibilities, I turn now to other examples of the Parisian rose’s themes in works from the late twelfth century that could have served as sources of inspiration and offer evidence of the devotional invention of the period.

Twelfth-Century Forerunners

Surprisingly, one of the first places to look for the combination of imagery in Notre-Dame’s western rose is floor mosaics. As Madeline Caviness explained, “Floor mosaics, since they inherently have the character of a mappa mundi, are often found to be forerunners of programs in rose windows.”[43] Ernst Kitzinger added an ingenious practical explanation for the subjects found in mosaic pavements, namely the fact that because mosaics are located on the floor, they presented a challenge for choosing subjects that did not invite desecration by being trod upon.[44] He suggested that themes pertaining to the world of nature and country life were a good source of “neutral” subjects for this potentially undesirable role, and that in turn, scenes from the natural realm offered the faithful an encyclopedic view of God’s creation.[45] Kitzinger’s insights offer context for the imagery from the natural world and prominent foliage throughout the western rose window of Notre-Dame of Paris.

Kitzinger’s focus on the late twelfth-century mosaics of S. Salvatore in Turin confirmed his surmise about floor mosaics, as they contain an inscription addressed to whomever would step upon the seven stairs to reach the black and white figural mosaic pavement in the chancel, with subjects that include exotic animals, a mappa mundi, and personifications of the twelve winds.[46] Most unexpected, given the mosaic’s location near the altar, is the fact that the inner circle of the mosaic contained, not a biblical subject, but the personification of Fortuna, thus combining the representation of fortune’s wheel with a world map.[47] Kitzinger reasoned that the mosaics participate in an anagogical approach to the divine, “The physical world became a mirror which reflects, a step whereby we can ascend to and reach the world of the intelligible and ultimately God Himself.”[48] S. Salvatore is characteristic of a number of late twelve-century churches in using non-Christian subjects to articulate Christian concepts. In the case of the Turin mosaic, none of the pictorial elements is inherently Christian, but their location within sacred topography confers a devotional context. Kitzinger’s analysis of the Italian floor mosaic is helpful in understanding the content of the western rose of Notre-Dame, both in leading us to understand its program as a joining of the terrestrial and heavenly realms, and in opening up the possibility that a non-biblical personification could have been at the window’s center.

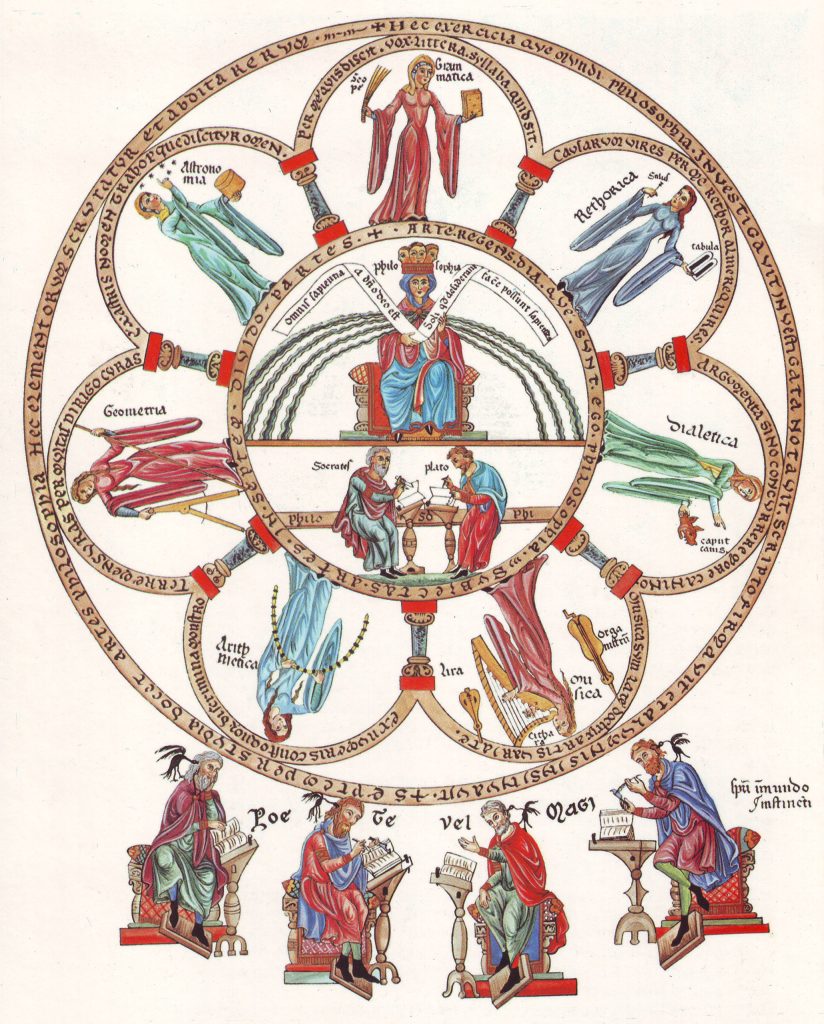

Caviness could track similar kinds of themes, albeit with variations, in antiquarian descriptions of the mosaic pavement that once adorned the choir of Saint-Rémi of Reims, as well as late twelfth-century rose windows in the neighboring programs of Laon Cathedral and Saint-Yved in Braine.[49] In these early rose windows, as with S. Salvatore’s floor mosaic, the central image was often a personification, such as Philosophia in Laon’s north transept rose (c. 1170-80), which is dedicated to the liberal arts and is the earliest extant rose in the cathedral.[50] Particularly revelatory was Caviness’s reconstruction of the south transept rose window of Saint-Yved in Braine of c. 1185-95. On the basis of remaining stained-glass panels and older descriptions that alluded to the southern rose window’s themes of “the triumph of the virtues over the vices and of religion over heresy”[51] accompanied by images of the liberal arts, constellations, and calendar imagery – which are subjects resembling those in the western rose of Notre-Dame of Paris – Caviness concluded that the center of Braine’s south transept rose was an allegorical representation of the triumph of religion over heresy. These examples of early rose windows at Laon and Braine, with the personification of Philosophia and allegory of religion at their respective centers, highlight the devotional invention of their subjects and expand the range of possibilities for Notre-Dame’s lost image.

Figure 9. Exterior view of the Imago Mundi rose window, Lausanne Cathedral, south transept, c. 1190 (photo: Stephen Pastan).

My concluding example is the rose window in the south transept of Lausanne Cathedral, now dated c. 1190 (Fig. 9).[52] It is one of the most frequently cited examples of an early rose window, undoubtedly because it offers features of a mappa mundi in a fairly well-preserved medieval stained-glass window. The window has an underlying numerical logic in the way its composition presents the components of the cosmos, in cohesive groups of twelve, eight, and four components, that underscore the notion of the divine intelligence that created and ordered the universe: the twelve months of the year, twelve signs of the zodiac, eight winds, eight so-called “monstrous races,” four elements, four seasons, four divinatory arts, and four rivers of paradise.[53] As Caviness has recently explored, the geometries of the Lausanne window “visualize knowledge” for the beholder.[54] The Lausanne rose offers numerous strikingly original images with prominent inscriptions that appear to have been made expressly to work within its organizational matrix. For example, the arresting image of the element of water, who offers her breast to a fish (Fig. 10) is from the center of lowest lobe of the window.

Figure 10. The element of water (Piscis Aqua) from the south transept of Lausanne Cathedral, c. 1190 (Photo: Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz).

The modern central lozenge of the rose window of Lausanne was created in 1899, with five medallions of God creating the universe, and these are the only explicitly Christian content in the window, apart from the four rivers of paradise.[55] Using the dimensions of the medieval stained-glass panels, partial extant inscriptions, and contemporaneous cosmological images in manuscripts from the region, Ellen J. Beer persuasively argued that Annus, the personification of the year (which also recalls the Latin word anus for ring), was the image originally featured at the Lausanne rose window’s center.[56] Annus would thus join other non-biblical figures that served as the centerpiece of compositions resembling those of the western rose window of Notre-Dame of Paris. Indeed, the lack of explicit Christian content among the central motifs of late twelfth-century rose windows may account for their poor rate of survival.

The late twelfth-century manuscript known as the Hortus deliciarum offered a similarly diverse selection of central figures in its circular compositions – known as rota or wheel-shaped diagrams – that regularly punctuated the manuscript. The large volume, overseen by Abbess Herrad of Hohenbourg as a communal teaching manuscript for the nuns of her convent on Mont-Odile in Alsace over several decades between c. 1176-96, has been painstakingly reconstructed on the basis of copies made from it before its destruction in 1870.[57] Its comprehensive program of texts and images included at least fifteen rota diagrams that allow us to observe how they functioned within the manuscript’s rich program of salvation history. Attentive readers were alerted to the importance of rotae in the opening poem, in which, playing upon the metaphor of the “volvelle,” or wheel-shape of the rotae, Herrad advised her nuns to ceaselessly “examine from all sides” or volvere, the contents of the Hortus deliciarum in their hearts.[58] As Michael Curschmann observed of the Hortus deliciarum and related manuscripts, “picture and text are made for each other and linked as equal partners in pursuit of a common goal.”[59] Texts within the Hortus also referred explicitly to imagery within the rotae.[60]

Further reinforcing the close ties between the Hortus deliciarum’s imagery and rose windows is the fact that the rota dedicated to “Philosophy, the Liberal Arts and the Poets,” f. 32r (Fig. 11) is preserved in a color replica that allows us to imagine the richness of the medieval manuscript and its resemblance to a rose window. The other rotae, along with many of the images from the rest of the manuscript, are preserved only in drawings made from the tracings that constituted the main part of the surviving pictorial record. These drawings can create the mistaken impression that the manuscript adhered to an outline style, whereas the Hortus deliciarum was in fact almost fully painted.[61]

Figure 11. Philosophia and the Seven Liberal Arts, copy made after the Hortus Delicarium, f. 32r, c. 1176-96 (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC-PD-Mark).

A particularly noteworthy use of circular diagrams in the Hortus deliciarum is the positioning of pairs of rotae at key transitions between the work’s three major thematic groupings of the Old Testament, the life of Christ, and the Church.[62] The rotae that define these groupings are:

- “Philosophy, the Liberal Arts and the Poets” (f. 32r; Fig. 11), which warns against misuse of knowledge in the wake of the Fall,[63] and was once complemented by a rota devoted to Idolatry (f. 32v).[64] These rotae established a transition between the scenes of the creation of the world and those focusing on Old Testament narratives.

- “Old and New Testament Sacrifices United” (fols. 67r and 67v), in which a conjoined central image of Moses-Christ from the first rota looks left, to the Old Testament material that precedes it, while Christ with the attributes of both king and priest in the second rota diagram looks right, towards the typological recapitulation of the Old Testament, and led into the section on the life of Christ.[65]

- The Chariots of Avaricia and Misericordia (fols. 204r and 204v), which amplify the Hortus deliciarum’s theme that contempt for the world is the remedy for avarice, and these rotae inaugurated the final section devoted to the Church.[66]

The central elements of the manuscript’s rotae resemble the late twelfth-century personifications we have identified in mosaics and early rose windows. In addition, thematic continuity between the imagery in the manuscript and in monumental rose windows is evident in the fact that the Hortus’s rotae of the “Old and New Testament Sacrifices United” are the direct inspiration behind the small, side by side roses in the south transept of Strasbourg Cathedral of c. 1228-35.[67] Attesting to their origin in a literary context, Strasbourg’s transept roses have an unusually large number of inscriptions identifying the personifications within, which match those in the Hortus deliciarum word for word.[68]

The comparanda of the later twelfth century we have examined in mosaics, windows, and manuscript illuminations raise several important issues. First, they suggest that the content of early rose windows was varied and inventive. Second, this body of material reinforces the fact that there were lots of possible thematic combinations and variations within depictions of time, the natural world, and the virtues and vices that resemble those of Notre-Dame of Paris. As Caviness summarized, “the themes that tended to be used in early Gothic roses were mixed and blended …. there was considerable flexibility in combining elements, and few combinations can be described as normative.”[69] On the basis of imagery with similar themes to those in the Parisian rose, it is entirely possible that the stained glass originally at the center of the western rose of Notre-Dame was a non-scriptural or allegorical subject. Since most of the early extant compositions are unique, it is difficult to do more than venture a guess, but the possibilities include: a sun of the type Lasteyrie saw in a modern version;[70] a representation of the triumph of virtue over vice comparable to an antiquarian description of the south rose at Braine;[71] an image of the Fall of Adam and Eve similar to the panel that was used as a stopgap in the rose window in the Parisian rose in the mid-nineteenth century;[72] or a personification such as Ecclesia, who is depicted in the Hortus deliciarum and other works of the period.[73]

Within these speculations, it is also interesting to recall the fact that the monk Guillaume, in his Life of Suger, mentioned a stained-glass window that the abbot of Saint-Denis gave to the cathedral of Notre-Dame in Paris.[74]) Guillaume, a canon of Saint-Denis who penned the vita shortly after Suger’s death in 1151, gave no other detail.[75] Nonetheless, Pierre Le Vieil, the eighteenth-century glass painter (and remover) of the stained glass of Notre-Dame, referred to the window Suger gave as “une espece de triomphe de la Sainte Vierge” [some kind of triumph of the holy Virgin].[76] According to Le Vieil’s description, it was an intricately painted window with a blue ground that recalled Saint-Denis’s twelfth-century windows. He stated that portions of the window Suger gave had been preserved in the gallery of the choir of the cathedral, and that they were subsequently demolished (probably by Le Vieil himself).

The window Suger gave to Notre-Dame of Paris has been imagined as everything from a Coronation of the Virgin to a representation of the triumph of the church,[77] in imagery thought to resemble one of Suger’s allegorical compositions such as the Chariot of Aminadab.[78] Indeed, questions surrounding the window Suger gave to Notre-Dame of Paris in the twelfth century resemble those about the lost central medieval motif of the western rose of the cathedral from the early thirteenth century: namely, whether it was a pictorial image of the Virgin and Child, of the kind represented by the modern image there now, or an allegorical representation, such as those found in twelfth-century windows at Laon, Braine, Lausanne, and elsewhere. Without a doubt, however, the closest comparisons for the extant medieval imagery found in the rest of Notre-Dame’s western rose window are the contemporary exterior sculptural reliefs of c. 1210-20 on the portals of the cathedral’s west façade to which we now turn.

The Sculptures of Notre-Dame’s Western Façade

The sculptures of the western portals of Notre-Dame offer a kind of summa of the role of Mary and her son in salvation (see Fig. 1).[79] The best parallel for the cycle of the virtues and vices in the western rose window of the cathedral is in the exterior reliefs of the socle zone at eye level on either side of the central doorway (Fig. 12).[80] The affinities between glazing and sculpture at Notre-Dame extend to the fact that in both media the depictions of the virtues and vices are twelve in number, despite the tradition of seven virtues and vices.[81] The swelling in their number allows for nuance that parallels the emphases of the Parisian circle of Peter the Chanter, which articulated a view of the priest as a kind of medical doctor who must take into account the many symptoms of his patient.[82] In both vitreous and sculptural images, the virtues are personified as seated women holding shields with symbolic animals (Figs. 7 and 12), while the vices are presented by means of scenes of human interactions (see Figs. 6 and 12). In the memorable phrasing of Émile Mâle, virtue is thus shown in its essence, and vice through its effects.[83]

Figure 12. Notre-Dame of Paris, detail of Fig. 1, with an oblique view of the central portal, showing the socle reliefs of the virtues and vices on the right embrasure, c. 1210 (Photo: Andrew Tallon © Mapping Gothic France, The Trustees of Columbia University, Media Center for Art History, Department of Art History & Archaeology).

According to Bruno Boerner, the pictorial distinctions between virtue and vice express the Parisian theologians’ belief that virtue is a gift that comes from God, who combated evil on behalf of humankind, and is instilled through the Christian sacrament of baptism.[84] In contrast, vice is human, finite, and contingent. If one only looked at the exterior sculpture of the central portal of Notre-Dame of Paris, one might conclude that the western rose drawing upon its imagery had Christ at its center, as is the case for the tympanum and trumeau aligned vertically on the exterior central portal beneath the western rose window (Fig. 12).[85]

However, William Hinkle examined the imagery associated with the tympanum of the Coronation of the Virgin on the left or north portal of Notre-Dame’s western façade, where reliefs of the signs of the zodiac and labors of the months are unfolded on the door jambs and trumeau (see Fig. 1). Hinkle cited a range of supporting materials to argue for the importance of its Marian imagery reflected in contemporaneous materials dedicated to the Virgin Mary that portray her as the flower of the months and seasons, the joy of the earth (“virginis Mariae, ideo cum summa exultatione gaudeat terra nostra”) and the Queen of Heaven, elevated above the stars.[86] While the Marian sculptural reliefs are not at the center of the façade composition – as is the western rose window – a Marian conceptual underpinning to the façade’s program is further supported by the earlier right portal. This southern portal of c. 1160, combines narrative scenes of the Nativity and image of Jesus enthroned in Mary’s lap at the apex of the tympanum. The image of Mary in the tympanum compares to a mid-twelfth-century seal of the chapter of Notre-Dame, which also features the Virgin, though not the infant Jesus.[87] In essence, then, the western rose window offers a re-presentation of carved imagery from all three portals of the west façade and transmutes their Marian and Christological themes into a single central wheel of light above.

Fiat lux

Yet there is one way that the western rose window of Notre-Dame of Paris utterly eludes its parallels with the exterior sculptural reliefs of the cathedral’s western facade and with the late twelfth-century floor mosaics and manuscript images that preceded it: the subjects of the rose are completed by the light that comes through the window and illuminates their panes for devotees on the interior of the church (Figs. 3 and 4).[88] The rose window’s translucency is a vital aspect of its meaning and impact, and recalls the fact that one of the most familiar and poetic ways of referring to Mary’s virginity was by means of the metaphor of light that passes through a glass without breaking it.[89]

This analogy, which is patristic in origin, could pertain to any glass composition of any subject. But a widely circulated later thirteenth-century version of the light metaphor adapted it to encompass the colored-saturated stained glass of contemporary windows. In Die goldene Schmiede, the poem of Konrad von Würzburg (†1287) praising the Virgin, the ray of the sun passing through the glass acquires the hues of the panes it illumines, comparable to the way the Son of God took on the Virgin’s color, or human nature, glossed as the wedding of the spirit to the flesh.[90] Through Würzburg’s poetics, we grasp that the western rose window of Notre-Dame of Paris not only depicts the mysteries of the cosmos and the wonders of creation in imagery, but also through the incorporation of light. The light enlists viewers in engaging with the invisible presence of God, per colorum imaginariam operationem.[91] Mary need not have been represented in pictorial form in the window to be a source of inspiration; the combined effects of the Marian, soteriological, and cosmological themes interwoven on the exterior portals, along with the light that illuminates the window, provide an elegant expression of contemporary early thirteenth-century Marian theology.

The Marian light metaphors can also be joined to a phenomenological consideration of the beholder’s experience of the light that streams into the vessel of the cathedral of Notre-Dame through the vitreous panes of the window. The transmitted light permeates the space of the beholder in an immersive way that the carved subjects on the exterior reliefs of the portals cannot. Yet in the reciprocity of themes between exterior reliefs and the imagery of the rose window on the interior, the luminous panes of the rose also confirm, insist upon, and activate themes enunciated in the portal sculptures. The sheen of the window’s luminous glass draws the eye upwards, and this pull is gently reinforced by the placement of subjects, with the twelve labors of the months on the lower half of the window and the twelve virtues in the upper half (Fig. 4). Such a glazed window is “positioned as the membrane between earth and heaven,”[92] as it both pulls the devotee’s gaze to the heavens and transmits changes in the light of this world filtering into the building. Drawing on the perceptual phenomenon known as the Purkinje shift, Madeline Caviness has observed that contrastive light levels over the course of the day illuminate different colors within the stained-glass window’s composition selectively, beginning with the blue panes in the early light of the day, and followed by reds and purples at midday. The colored panes of the windows take hold in relation to the intensity of the incoming light throughout the day, kinetically enlivening the interior.[93]

These observations recall Kitzinger’s suggestion that a large circular composition can serve as a kind of mirror that connects the earthly and heavenly realms.[94] Further, Francesca Dell’Acqua cited the comments of appreciative observers over time who compared the shimmering effect of glass to that of gold, gemstones, molten metals, crystal, and to the materialization of divine light.[95] She also noted that the richly colored vitreous materials of a window approximate the precious gems of the heavenly Jerusalem, described in scripture.[96] Adding to these metaphoric associations, Herbert Kessler has remarked on the fact that a window’s vitreous material was forged by a process that transformed the base element of sand into a resplendent new substance, in a metamorphosis rich with Christian symbolism.[97]

Thus, even before the devotee engaged in the window’s figural themes, the glazing of the western rose of Notre-Dame contributed to the sensory enrichment of the interior ambiance of the cathedral, an enrichment that was likened to the central mystery of the Virgin birth of Jesus. Whatever the medieval image at the western rose window’s center may have been – the Virgin and Child as the modern image evokes (Fig. 3), a medieval Christological image like the sculptures aligned with the rose on the exterior (Figs. 1 and 11), a Marian image such as the early seals of the Notre-Dame chapter,[98] or a personification comparable to the images of Philosophia, Annus, Ecclesia, and others we have explored – the rose window provided a vibrant locus for thinking with and beyond its imagery.

References

| ↑1 | College Art Association Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, 2002. Contributions to the session by Ilene Forsyth and Walter Cahn were subsequently published in Gesta 42.2 (2002). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For chronology, see Caroline Bruzelius, “The Construction of Notre-Dame in Paris,” The Art Bulletin 69 (1987), pp. 540-69. Within its vast bibliography, a few key works may be singled out: Marcel Aubert, La cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris: notice historique et archéologique (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1950 [with multiple editions going back to 1909]); Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, Notre-Dame de Paris, trans. John Goodman (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998); and Dany Sandron and Andrew Tallon, Notre-Dame de Paris: Neuf siècles d’histoire (Lassay-les-Châteaux: Parigramme, 2013). I’m also inspired by the example of Craig M. Wright, Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500-1550 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), who, in order to address the early musical life of Notre-Dame of Paris, undertook a wonderfully thorough examination of all things related to the quality of sound at the great cathedral, including its interior hangings and spatial divisions, its processions, and the question of who actually did the singing. His is an important example of scholarship in which an unapologetically disciplinary inquiry contributes to the larger understanding of the cathedral. |

| ↑3 | For the “gigantism” of Notre-Dame, see Bruzelius, “The Construction,” pp. 540-41. For contemporaneous buildings, see Jean Bony, Ch IV “A First Gothic System, ca. 1160-80,” in idem, French Gothic Architecture of the 12th and 13th Centuries (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), pp. 117-93. When the nave of Notre-Dame of Paris was built in the late twelfth century, its relatively small upper windows were so far from the ground that the interior remained dark, so the upper windows were refashioned only decades later, doubling their surface area. On the transformation of the nave elevation of Notre-Dame, see Geneviève Viollet-le-Duc, “Découverte par Viollet-le-Duc des rose des travées de la nef,” Monuments Historiques, fasc. 3 (1968), p. 108; Robert Branner, “Paris and the Origins of Rayonnant Gothic Architecture down to 1240,” The Art Bulletin 44 (1962), pp. 39-51 at pp. 47-48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1962.10789080; and Stephen Murray, “Notre-Dame of Paris and the Anticipation of Gothic,” The Art Bulletin 80 (1998), pp. 229-53 at p. 250, n. 34. https://doi.org/10.2307/3051231 |

| ↑4 | See John W. Baldwin, Masters, Princes, and Merchants: The Social Views of Peter the Chanter & his Circle, 2 vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970), esp. vol. I: pp. 65-71, vol. II: pp. 48-49, n. 31; see the translation of Peter’s “Contra superfluitatem aedificiorum,” in G.G. Coulton, Life in the Middle Ages: Selected, Translated & Annotated, The Cambridge Anthologies (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1930), vol. 2: no. 15, pp. 25-28. |

| ↑5 | As suggested by the accounts of the Abbey of Saint-Denis, see Louis Grodecki, Les vitraux de Saint-Denis: étude sur le vitrail au XIIe siècle, Corpus Vitrearum France, Etudes I (Paris: CNRS, 1976), p. 28, n. 44. |

| ↑6 | Jean Lafond in Marcel Aubert et al., Les vitraux de Notre-Dame et de la Sainte-Chapelle de Paris, Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi, France, I (Paris: Caisse nationale des monuments historiques, 1959), pp. 13-67: hereafter this work will be referred to as Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame. |

| ↑7 | See Pierre LeVieil, L’Art de la peinture sur verre et de la vitrerie (Paris: L.F. Delatour, 1774), pp. 23-25. On discrepancies between his testimony and the actual apertures that would have held the glass, see Henry Kraus, “Notre-Dame’s Vanished Glass, I. The Iconography,” Gazette des beaux-arts 68 (1966), pp. 131-48 at pp. 131-35. |

| ↑8 | See the presentation of Notre-Dame’s roses in Painton Cowen, The Rose Window: Splendour and Symbol (London, 2005), pp. 88-91 and pp. 100-03 with excellent color images. On rose windows generally, see Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, “Rose” in idem, Dictionnaire raisonné de l’architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Paris, 1869), vol. 8, pp. 39-42; Helen J. Dow, “The Rose-Window,” The Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 20 (1957), pp. 248-97. https://doi.org/10.2307/750783; and Elizabeth Carson Pastan, “Regarding the Early Rose Window” in Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Medium, Methods, Expressions, Brill Reading Medieval Sources series, ed. Elizabeth Carson Pastan and Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz (Brill, 2019), pp. 269-81. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004395718_021 |

| ↑9 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 23-34 dates the western rose to c. 1220, as do Louis Grodecki and Catherine Brisac, Gothic Stained Glass, 1200-1300, trans. Barbara Drake Boehm (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1984), pp. 52-54. In contrast, Bruzelius, “Construction,” p. 541, 565-66 suggests c. 1225-40, a position also taken by Sandron and Tallon, Notre-Dame de Paris, pp. 90-93, who note instabilities in the western portal’s foundations that created delays in installing the upper stories of the western frontispiece. In choosing c. 1220, I have opted for the date of the window’s creation. |

| ↑10 | The view of the west rose is currently unobstructed, as the organ has been removed for cleaning and restoration. |

| ↑11 | On the different conception of later rose windows, see Robert Suckale, “Thesen zum Bedeutungswandel der gotischen Fensterrose,” in Karl Clausberg, Dieter Kimpel, Hans-Joachim Kunst, and Robert Suckale, eds., Bauwerk und Bildwerk im Hochmittelalter: Anschaulich Beiträge zur Kultur- und Sozialgeschichte (Giessen: Anabas-Verlag 1981), pp. 259-94. Notre-Dame’s north transept rose of c. 1250 is the best preserved of its three medieval rose windows, and the only one to merit an illustration in Lasteyrie’s foundational publication. See Ferdinand de Lasteyrie, Histoire de la peinture sur verre d’après ses monuments en France: Planches (Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1853), pp. 134-37 and pl. XX1; and Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 35-51. The south rose of c. 1260 was particularly admired by Viollet-le-Duc for its engineering. See idem, “Rose,” pp. 50-54 and his drawing after it on p. 51, Fig. 7; Lasteyrie, Histoire, pp. 132-34; and Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 52-67. The Parisian transept roses leverage size over pictorial exposition. In the north transept rose for example, as Lafond demonstrates in his planche 8 and catalogue pp. 46-51, the none of the figural medallions is larger than 0.80 meters or about 31 1/2 inches in diameter; these comparatively small medallions in the very large rose window demonstrate the different aim of the pictorial imagery in this rose, as compared to the western rose, where the medallions are larger in proportion to the smaller vitreous composition. |

| ↑12 | Anna Russakoff, Imagining the Miraculous: Miraculous Images of the Virgin Mary in French Illuminated Manuscripts, ca. 1250-1450 (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2019), p. 5. |

| ↑13 | Émile Mâle, Religious Art in France, the Twelfth Century: A Study of Medieval Iconography and its Sources, new ed. by Harry Bober, trans. Marthiel Mathews, Bollingen Series, 90-1 (1922; Princeton, 1978), pp. 427-40; Adolf Katzenellenbogen, The Sculptural Programs of Chartres Cathedral: Christ, Mary, Ecclesia (1955; New York: The Norton Library, 1964), pp. 56-62. For more recent appraisals of Marian imagery with a thirteenth-century focus, see Miri Rubin, Emotion and Devotion: The Meaning of Mary in Medieval Religious Cultures, The Natalie Zemon Davis Annual Lectures, 2 (New York: CEU Press, 2009), esp. pp 45-77; and Russakoff, Imagining the Miraculous, pp. 1-20. |

| ↑14 | See the overview of the western façade program in Willibald Sauerländer, Gothic Sculpture in France, 1140-1270, trans. Janet Sondheimer (London: Thames and Hudson, 1972), pp. 450-57. Also noteworthy is Erwin Panofsky, Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism (1957; New York: Meridian Books, 1971), pp. 71-72 who spoke about the importance of this rose window without ever mentioning its imagery; and Elizabeth Carson Pastan, “A Window on Panofsky’s Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism,” Folia Historiae Artium 19 (2021), pp. 75-84. |

| ↑15 | William J. Courtenay, “The Growth of Marian Devotion,” Ch. 6 in idem, Rituals for the Dead: Religion and Community in the Medieval University of Paris (Notre Dame, IN, 2019), pp. 101-30 noted not only the large numbers of cathedrals rededicated to the Virgin in the course of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, particularly in northern France, but also the increase in the number of seals with images of the Virgin or Virgin and Child beginning in the mid-twelfth century. Nonetheless, reviewing the evidence in detail, Courtenay, p. 130 concludes that, despite these important early roots, it was in the course of the thirteenth century and especially in the fourteenth century that devotion to the Virgin increased at the University of Paris. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvpj7c4z.11 |

| ↑16 | For the Virgin and Child at the center of the north transept rose, see Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, p. 51, panel X-1, which is partially preserved. For other Marian imagery in the northern choir of Notre-Dame of Paris, see the overview in Erlande-Brandenburg, Notre-Dame de Paris (as in n. 2), pp. 165-210. For particular aspects of the northern choir, see Dorothy W. Gillerman, The Clôture of Notre-Dame and its Role in the Fourteenth Century Choir Program (New York: Garland Publishing, 1977), pp. 53-66; M. Cecilia Gaposchkin, “The King of France and the Queen of Heaven: The Iconography of the Porte Rouge of Notre-Dame of Paris,” Gesta 39 (2000), pp. 58-72. https://doi.org/10.2307/767154; and Michael T. Davis, “Canonical Views: The Theophilus Story and the Choir Palace, Paris, and the Royal State,” in Reading Medieval Images: The Art Historian and the Object, ed. Elizabeth Sears and Thelma K. Thomas (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002), pp. 102-16. |

| ↑17 | Margot E. Fassler, The Virgin of Chartres: Making History through Liturgy and the Arts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010), p. xi. |

| ↑18 | See Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame (as in n. 5), with restoration charts of the three rose windows at planche 3 (western rose), planche 8 (north rose), and planche 11 (south rose). |

| ↑19 | The literature on Notre-Dame’s glazing is surprisingly small. Besides Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame and Kraus, “Notre-Dame’s Vanished Glass” (as in n. 7), see Lasteyrie, Histoire (as in n. 11) of 1857, which has the earliest full descriptions of its three medieval rose windows, and is now available online https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k97921125/f15.image, accessed 12 November 2021; Grodecki and Brisac, Gothic Stained Glass (as in n. 9), pp. 52-54 Françoise Gatouillat, “Les Vitraux Anciens,” pp. 60-65 and Reine Bonnefoy, “Les trois grandes roses,” pp. 283-91 in André Vingt-Trois et al., Notre-Dame de Paris (Strasbourg: Nuée bleue, 2012). |

| ↑20 | Lasteyrie, Histoire, p. 138. Lasteyrie misidentified the prophets in the window’s second concentric ring as kings; this, in combination with the multiple (modern) foliate panels at the window’s center, led to his conclusion that the window was a Tree of Jesse. |

| ↑21 | Lasteyrie, Histoire, p. 138. My translation. |

| ↑22 | Lasteyrie, Histoire, p. 138 called it “une espece de soleil aux couleurs blafardes.” This description likely indicates the characteristic technique of enameling, associated with the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, in which color is applied in a painted layer of enamel that leaves a distinctively pale and milky appearance rather than the thirteenth-century technique of adding metallic oxides into the molten silicate mixture to color the glass in the mass, which contributes to their characteristic deeply saturated colors. See Sarah Brown, Stained Glass, An Illustrated History (New York: Crescent Books, 1992), pp. 113-25. |

| ↑23 | Gatouillat, “Les Vitraux Anciens,” p. 62. |

| ↑24 | Lasteyrie, Histoire, p. 138. This statement could also be translated as “must have been the Virgin,” but in either case the conditional and speculative nature of Lasteyrie’s observation are clear. |

| ↑25 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 24-25 dubbed the combination of the Virgin and Child with prophets “the most classic of iconographic themes”; Grodecki and Brisac, Gothic Stained Glass, p. 54; and Cowen, The Rose Window, p. 90. Only William M. Hinkle, “The King and Pope on The Virgin Portal of Notre-Dame,” The Art Bulletin 48.1 (1966), pp. 1-13 at p. 1 n. 10, and Gatouillat, “Les Vitraux Anciens,” p. 62 refrained from emphasizing the Virgin and Child at center, though another author in the same publication, Bonnefoy, “Les trois grandes roses,” p. 285 does. https://doi.org/10.2307/3048328 |

| ↑26 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 31-34, with descriptions of each panel. The ornamental panels are treated separately on p. 34, and according to Lafond, are not well preserved. |

| ↑27 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 31-34; Gatouillat, “Les Vitraux Anciens” (as in n. 19), p. 62. |

| ↑28 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, planche 1, after p. 20; and see his discussion of the prophet at D-4 on p. 32, indicating that only the right hand is a resoration. |

| ↑29 | See the central image of Christ from the tympanum of the Last Judgment, below the rose on the western façade of the cathedral in Sauerländer, Gothic Sculpture (as in n. 14), pl. 147, and his discussion of dating, pp. 456-57. |

| ↑30 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, planche 3, for his restoration chart of the window. And see pp. 32-33 for his brief discussion of the sixteenth-century panels at F-4, H-4 and J-4. |

| ↑31 | Lasteyrie, Histoire, p. 138; and documented in Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, p. 32, though without further comment. |

| ↑32 | Although the date the antiphon was composed is uncertain, it can be found in a twelfth-century manuscript from St. Albans and was introduced into the Divine Office in the fourteenth century. See Hugh Henry, “Ave Regina,” in The New Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. 2 (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907): http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02149b.htm, accessed 27 July 2020. |

| ↑33 | Lasteyrie, Histoire, pp. 138-42. |

| ↑34 | Wright, Music and Ceremony (as in n. 2), pp. 143-44 on the organ loft first constructed beneath the western rose in 1401. |

| ↑35 | See Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 32-33, with entries that refer to his restoration chart, planche 3. The thirteenth-century panels are Cowardice (D-5) and Avarice (K-5) from the upper half of the window (Figs. 5 and 7 here), and Virgo (F-6), Cancer (G-6), and Aquarius (J-5) from the lower half. |

| ↑36 | For good color reproductions of Cowardice, see Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, planche 1, after p. 20; and Grodecki and Brisac, Gothic Stained Glass (as in n. 9), pp. 53-54 and Fig. 41. For the topos of the fearful knight, see Marian Bleeke, “Modern Knights, Medieval Snails, and Naughty Nuns,” in Whose Middle Ages?: Teachable Moments for an Ill-Used Past, ed. Andrew Albin, Mary C. Erler, Thomas O’Donnell, Nicholas L. Paul, and Nina Rowe (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), pp. 196-207. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvnwbxk3.22 |

| ↑37 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, pp. 32-33. The sixteenth-century panels are Capricorn (D-6), Taurus (H-6), and Pride (J-6). |

| ↑38 | The thirteenth-century quatrefoils include the virtues of Charity and Perseverance (shown in Fig. 8 here), and October in the lower half of the window, who sows grain (Fig. 6 here). See the illustration of the virtues in Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, planche 4; Grodecki and Brisac, Gothic Stained Glass, p. 53 and Fig. 40. |

| ↑39 | See Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, planche 3 for the restoration chart. The sixteenth-century panels are April, who threshes the grain (F-12), and June, who tends sheep (G-12). |

| ↑40 | Baldwin, Masters, Princes, and Merchants (as in n. 4); Elizabeth Carson Pastan, “The Curious Case of the Prostitutes’ Window,” Codex Aquilarensis: Revista de Arte Medieval, vol. 37, issue in honor of Herbert L. Kessler (December, 2021), pp. 395-412. |

| ↑41 | Emily Corran, Lying and Perjury in Medieval Practical Thought: A Study in the History of Casuistry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 85-92. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198828884.001.0001 |

| ↑42 | William M. Hinkle, “The Cosmic and Terrestrial Cycles on the Virgin Portal of Notre-Dame,” The Art Bulletin 49-4 (1967), pp. 287-96; also see idem, “The King and Pope on the Virgin Portal” (as in n. 25). https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1967.10788666 |

| ↑43 | Madeline H. Caviness, Sumptuous Arts at the Royal Abbeys in Reims and Braine: Ornatus elegantiae, varietate stupendes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), p. 92. For a convenient overview of mappaemundi, see David Woodward, “Medieval Mappaemundi,” in J. B. Harley and idem, eds., The History of Cartography, 3 vols., vol. I: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), pp. 286-370, and Asa Simon Mittman, Maps and Monsters in Medieval England, Studies in Medieval History and Culture (New York: Routledge, 2006). |

| ↑44 | Ernst Kitzinger, “World Map and Fortune’s Wheel: A Medieval Mosaic Floor in Turin,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 117.5 (1973), pp. 344-73. |

| ↑45 | Kitzinger, “World Map,” p. 345, and also pp. 369-72, with further bibliography. |

| ↑46 | Kitzinger, “World Map,” p. 349 quoting what can still be read of the inscription, and pp. 350-53. |

| ↑47 | Kitzinger, “World Map,” pp. 353-54, 361-69. |

| ↑48 | Kitzinger, “World Map,” pp. 370-71. |

| ↑49 | For Saint-Rémi, see Caviness, Sumptuous Arts, pp. 37-39 and her Fig. 3 with a reconstruction, based on Nicholas Bergier’s description of 1622 before the remois mosaics were lost. |

| ↑50 | For Laon Cathedral’s north transept rose window, see Caviness, Sumptuous Arts, p. 90 and pls. 232 and 243; Laura Cleaver, Education in Twelfth-Century Art and Architecture: Images of learning in Europe, c. 1100-1220 (Suffolk: The Boydell Press, 2016), pp. 7-36; and Courtenay, Rituals for the Dead (as in n. 15), pp. 112-16 and Fig. 23. Later rose windows in Laon have explicitly Christian subjects; see the overview in Les vitraux de Paris, de la région parisienne, de la Picardie et du Nord-Pas-de-Calais. Corpus Vitrearum, France, Recensement des vitraux anciens de la France, I (Paris: CNRS, 1978), pp. 162-63. |

| ↑51 | Caviness, Sumptuous Arts, pp. 89-90, and her reconstruction pl. 244, p. 312. Also see her Catalogue A, pp. 348-50 with the extant stained-glass panels from Braine’s south transept rose. Caviness also discusses the Christian content of the northern rose, p. 89, and the western rose, pp. 90-92 |

| ↑52 | The rose was originally dated c. 1217-35 in the work of Ellen J. Beer, who returned to the Lausanne rose in numerous publications, beginning with her contribution Die Glasmalereien der Schweiz vom 12. bis zum Beginn des 14. Jahrhunderts (Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi Schweiz 1), Basel, 1956, pp. 25-71. For a good representation of her scholarship, see Ellen J. Beer, “Les vitraux du Moyen Age de la cathédrale,” in Jean-Charles Biaudet et al., La cathédrale de Lausanne, Bibliothèque de la Société d’histoire de l’art en Suisse, 3 (Bern: Société d’Histoire de l’Art end Suise, 1975), pp. 221-55. Christophe Amsler et al., La rose de la cathédrale, Histoire et conservation récente (Lausanne: Editions Payot, 1999) offers excellent, panel by panel documentation of the conservation of the window undertaken in 1996-98. The archeology of the site now points to an earlier dating of c. 1190 for the rose: see Werner Stöckli, “Les structures lapidaires,” in Amsler et al., La rose, pp. 7-20; and Alain Villes, “La cathédrale actuelle: sa chronologie et sa place dans l’architecture gothique,” in Peter Kurmann, ed., La cathédrale Notre-Dame de Lausanne: monument européen, temple vaudois (Lausanne: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 2012), pp. 55-91. For an analysis of the Lausanne rose within its setting that takes this revised dating into account, see Elizabeth Carson Pastan and Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, “Seeing and Not Seeing the Rose Window of Lausanne Cathedral,” in Unfolding Narratives: Art, Architecture, and the Moving Viewer, circa 300-1500 CE, ed. Anne Heath and Gillian Elliott (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming 2021), pp. 1-23. |

| ↑53 | For comprehensive description, in addition to Beer’s work cited above, see Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, “Die Rose in der Südquerhausfassade der Kathedrale von Lausanne, ein christliches Bild der Zeit und des Raums,” in Wissensformen (6. Internationaler Barocksommerkurs, Stiftung Bibliothek Werner Oechslin), Zurich, 2008, pp. 50-59 at pp. 51-53, and eadem, “Les vitraux de la rose. Une image chrétienne du temps et du monde,” in Kurmann, La cathédrale Notre-Dame de Lausanne, pp. 227-45 with good color images. |

| ↑54 | Madeline H. Caviness, “Templates for Knowledge: Geometric Ordering of the Built Environment, Monumental Decoration, and Illuminated Page,” in Marcia Kupfer, Adam S. Cohen, and J.H. Chajes, eds., The Visualization of Knowledge in Medieval and Early Modern Europe (Turnhout: Brepols, 2020), pp. 405-28 at pp. 405, 422-24. |

| ↑55 | See Claire Huguenin and Stefan Trümpler, “La rose à travers les siècles. Notes historiques et observations techniques,” in Amsler et al., La rose de la cathédrale, pp. 34-53. On controversies surrounding the central motifs of the window, see Mary Alice Hilton, “La rose de la cathédrale de Lausanne,” Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 46 (1989), pp. 251-69; François Forel, “Le carré central de la rose de la cathédrale de Lausanne, À propos de l’étude d’Alice Mary Hilton,” Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte 47 (1990), pp. 235-43; and the helpful overview in Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, “Die Rose in der Südquerhausfassade der Kathedrale von Lausanne, ein christliches Bild der Zeit und des Raums,” in Wissensformen, 6. Internationaler Barocksommerkurs, Stiftung Bibliothek Werner Oechslin (Zurich, 2008), pp. 50-59 at pp. 51-53. |

| ↑56 | Beer, “Les vitraux du Moyen Age,” esp. pp. 231-44. |

| ↑57 | In 1870, the manuscript, which was then housed in the Municipal Library of Strasbourg, was destroyed during the Prussian siege. In 1979, the Hortus deliciarum was reconstructed in a joint effort of the Warburg Institute and the Index of Christian Art at Princeton: Rosalie Green et al., Herrad of Hohenbourg, Hortus Deliciarum, 2 vols. (London: The Warburg Institute, 1979). Volume 1 will be referred to as Commentary for citations to the catalogue of miniatures (overseen by Rosalie Green), pp. 89-228; and individual contributions in the volume will be cited by author, including: Michael Evans, “Description of the Manuscript and Reconstruction,” pp. 1-8, and Rosalie Green, “The Miniatures,” p. 17-36. Volume 2, the reconstructed facsimile, will be referred to as HD. As explained in Green’s chapter, “The Miniatures,” p. 24 of approximately 346 scenes that once decorated the manuscript, 187 or 54% were fully copied, and 91 of these or 26% are totally lacking. She also added that because the Hortus remained unbound for many years, and included verse, prose, songs, and glosses of disparate lengths, as well as interpolated leaves of different sizes, it is hard to be certain about the full contents of the manuscript. Evans, “Description of the Manuscript and Reconstruction,” p. 7 estimated that of over 1160 sources, and there are complete transcripts of some 240 items, or not even 5% of the total. |

| ↑58 | HD, no. 1, pp. 2-3 at lines 47-48. A point made by Karl F. Morrison, History as a Visual Art in the Twelfth-Century Renaissance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), pp. 113-20 at p. 115. |

| ↑59 | Michael Curschmann, “Imagined Exegesis: Text and Picture in the Exegetical Works of Rupert of Deutz, Honorius Augustodunensis, and Gerhoch of Reichersberg,” Traditio 44 (1988), pp. 145-169 at p. 147. This point is developed in Danielle B. Joyner, Painting the Hortus Deliciarum: Medieval Women, Wisdom, and Time (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016) through her examination of the nuns’ use of computus. For her focused study of the topic, see eadem, “Counting Time and Comprehending History in the Hortus Deliciarum,” in Moritz Wedell, ed., Was Zählt: Ordnungsangebote, Gebrauchsformen und Erfahrungsmodalitäten de “numerus” im Mittelalter (Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, 2012), pp. 105-18. https://doi.org/10.7788/boehlau.9783412214876.105 |

| ↑60 | Fiona J. Griffiths, The Garden of Delights: Reform and Renaissance for Women in the Twelfth Century (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), pp. 119-25. https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812202113 |

| ↑61 | Green, “The Miniatures,” pp. 17-23. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004544499_006 |

| ↑62 | Frequently noted, see Green, “The Miniatures,” p. 29; and Griffiths, The Garden of Delights, pp. 111-12. |

| ↑63 | HD, p. 57, Pl. 18; Commentary (by Michael Evans), pp. 104-05. Philosophia is among the most written about images; in addition to the sources cited by Evans, see Griffiths, The Garden of Delights, pp. 144-58; Cleaver, Education in Twelfth-Century Art (as in n. 50), pp. 7-36; and Joyner, Painting, pp. 71-76. |

| ↑64 | Idolatry is represented by a blank folio HD, p. 58; Commentary, p. 107. |

| ↑65 | Annette Krüger and Gabriele Runge, “Lifting the Veil: two typological diagrams in the Hortus deliciarum,” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 60 (1997), pp. 1-22, esp. p. 14. https://doi.org/10.2307/751223 |

| ↑66 | HD, pp. 334-35, Pls. 118-119; Commentary, pp 194-95; Joyner, Painting, p. 33 emphasizing that the rotae “quite literally look the canonesses in the eye and demand a choice between sin and good deeds.” |

| ↑67 | Joseph Walter, “Les deux roses du transept sud de la cathédrale de Strasbourg,” Archives Alsaciennes d’histoire de l’art 7 (1928), pp. 13–33; Victor Beyer, Christiane Wild-Bock, an Fridtjof Zschokke, Les vitraux de la cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg, Corpus Vitrearum France 9.1 (Paris: CNRS, 1986), pp. 123–40 ; Jean-Philippe Meyer and Brigitte Kurmann-Schwarz, La cathédrale de Strasbourg choeur et transept: de l’art roman au gothique (vers 1180–1240) (Strasbourg: Société des Amis de la cathédrale de Strasbourg, 2010), pp. 251–70. |

| ↑68 | Meyer and Kurmann-Schwarz, Cathédrale de Strasbourg, p. 266. |

| ↑69 | Caviness, Sumptuous Arts (as in n. 43), p. 91. |

| ↑70 | Lasteyrie, Histoire (as in n. 11), p. 138. |

| ↑71 | Caviness, Sumptuous Arts, pp. 89-90 remarked on this subject among the possibilities for the south transept rose of the abbey of Braine. |

| ↑72 | In unpublished papers dating to the restoration of 1848-1855 at Notre-Dame, the antiquarian Baron Ferdinand de Guilhermy documented seeing a panel of the Temptation of Adam and Eve used as a stop gap in the western rose of Notre-Dame. The panel is now in the Musée de l’Oeuvre de Notre-Dame in Paris, Cl. 58-P-1034. As Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, p. 335 documents, the panel is compatible in dimensions to other panels in the western rose but drew attention to itself because it was mounted backwards within the window, with its painted surface facing to the exterior. The extant panel was dated by Lafond to the first half of the thirteenth century and appears later than other panels in the western rose; see his planche 96 |

| ↑73 | See Joyner, Painting the Hortus deliciarum (as in n. 59), pp. 114-19; Carl F. Barnes, Jr., The Portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt: a New Critical Edition and Color Facsimile, (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2009), pp. 47-48. |

| ↑74 | Sugerii Vita in Francoise Gasparri, ed. and trans., Suger, Oeuvres, vol. 2 (Paris, 2001), pp. 292-357 at book 2, p. 316: Nonne indicium evidens est liberalitatis ejus eximie in ecclesia Parisiensi illud ex vitro opus insigne? (“Isn’t the proof of [Suger’s] rare generosity evident in that admirable stained-glass window in the church of Paris?” |

| ↑75 | Also see Gasparri’s introductory remarks in Oeuvres, vol. 2, pp. XXV-XXXIII. |

| ↑76 | Le Vieil, L’Art de la Peinture sur Verre (as in n. 7), p. 23. |

| ↑77 | Lafond, Les vitraux de Notre-Dame, p. 15 with a good overview of the question. |

| ↑78 | For the Chariot of Aminadab, see Grodecki, Les vitraux de Saint-Denis (as in n. 5), pp. 98-102 and plate V. |

| ↑79 | Good images in Sauerländer, Gothic Sculpture (as in n. 14), pl. 151, and dated by him to c. 1210-20; discussion pp. 453-54, and 456-57. For the cycle of the virtues and vices, see Émile Mâle, Religious Art in France, the Thirteenth Century: a Study of Medieval Iconography and its Sources, new ed. by Harry Bober, trans. Marthiel Mathews, Bollingen Series, 90.2 (1898; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 101-32. For discussions with emphasis on Notre-Dame of Paris, see: Adolf Katzenellenbogen, Allegories of the Virtues and Vices in Mediaeval Art from early Christian times to the thirteenth century, trans. Alan J. P. Crick, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1964), pp. 75-81; Jennifer O’Reilly, Studies in the Iconography of the Virtues and Vices in the Middle Ages (New York: Garland Publishers, 1988), pp. 190-98; and Aden Kumler, Translating Truth: Ambitious Images and Religious Knowledge in late medieval France and England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), pp. 173-83. |

| ↑80 | For an analogous approach to the sculpture and glazing of the western façade of Saint-Denis, see Elizabeth Carson Pastan, “‘Familiar as the Rose in Spring’: The Circular Window in the West Façade of Saint-Denis.” Viator 49.1 (2018), pp. 99-152, esp. pp. 118-29. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.116876 |

| ↑81 | See Morton Bloomfield, The Seven Deadly Sins: An Introduction to the History of a Religious Concept, with Special Reference to Medieval English Literature (East Lansing, MI, 1952), esp. pp. 43-62; and for the flexibility of the tradition, see Siegfried Wenzel, “The Seven Deadly Sins: Some Problems of Research,” Speculum 43 (1968): 1-22; idem, “Preaching the Seven Deadly Sins,” in In the Garden of Evil: The Vices and Culture in the Middle Ages, ed. Richard G. Newhauser (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2005), pp. 145-69; and the range of studies collected in Richard G. Newhauser and Susan J. Ridyard, eds., Sin in Medieval and Early Modern Culture: The Tradition of the Seven Deadly Sins (Boydell & Brewer, 2012). |

| ↑82 | Baldwin, Masters, Princes, and Merchants (as in. n. 4), I: pp. 50-53. |

| ↑83 | Mâle, Religious Art in France, the Thirteenth Century, p. 111; see Kumler, Translating Truth, pp. 176-77, who focuses on the visual translation of this imagery into the reliefs of Notre-Dame of Paris. |

| ↑84 | Bruno Boerner, Par caritas par meritum: Studien zur Theologie des gotischen Weltgerichtsportals in Frankreich – am Beispiel des mittleren Westeingangs von Notre-Dame in Paris, Scrinium Friburgense, 7 (Fribourg: De Gruyter, 1998), esp. pp. 137-78. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110915754; good distillation in idem, “Réflexions sur les rapports entre la scolastique naissante et les programmes sculptés du XIIIe siècle,” in Yves Christe, ed., De l’art comme mystagogie: Iconographie du Jugement dernier et des fins dernières à l’époque gothique, Actes du Colloque de la Fondation Hardt, 13-16 February 1994, Civilisation Médievale, 3 (Poitiers: Centre d’Etudes Supérieures de Civilisation Médiévale, 1996), pp. 55-69. |

| ↑85 | See Sauerländer, Gothic Sculpture (as in n. 14), pls. 152-54. Christ is the central image of the western rose at Chartres Cathedral of c. 1205-10. For this superbly preserved window, see Claudine Lautier, “The West Rose of the Cathedral of Chartres,” in Kathleen Nolan and Dany Sandron (eds.), Arts of the Medieval Cathedrals: Studies on Architecture, Stained Glass and Sculpture in Honor of Anne Prache (Farnum, 2015), pp. 121-33. By focusing exclusively on Notre-Dame’s central portal of the Last Judgement, and not the western façade program as a whole, Boerner, “Réflexions,” pp. 63-64 overlooked the importance of the Virgin Mary woven throughout Notre-Dame’s other western portals’ subjects. |

| ↑86 | Hinkle, “The Cosmic and Terrestrial Cycles” (as in n. 42), esp. pp. 289-90, 292-95. Sauerländer, Gothic Sculpture, pp. 454-55 also remarks on the importance of Mary, which he connects to the cathedral’s dedication to the Assumption of the Virgin |

| ↑87 | Sauerländer, Gothic Sculpture, pl. 40 and pp. 404-06, with further bibliography. Laura Gelfand, “Negotiating Harmonious Divisions of Power: A New Reading of the Tympanum of the Sainte-Anne Portal of the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 140 (2002), pp. 249-60 at p. 255 compared the pose of the Virgin in the tympanum to that of the chapter seal of 1146, although the seal does not include the Christ Child, as the twelfth-century tympanum does. See Régine Pernoud, Notre-Dame de Paris, 1163-1963: Exposition du Huitième Centenaire, exhibition catalogue, June-October 1963 (Paris: Archives Nationales de France, 1963), cat. no. 16 (n. p.) and plate V, for the clearest black and white photograph of this seal. Both Courtenay, Rituals for the Dead (as in n. 15), esp. pp. 104-19, and Lindsay Cook, “Architectural Citation of Notre-Dame of Paris in the Land of the Paris Cathedral Chapter” (Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 2018), pp. 181-87 have explored these seals as evidence of the growth of Marian piety. I thank one of the anonymous readers of this study for drawing my attention to these materials. Also see Brigitte Bedos-Rezak, “Medieval Women in French Sigillographic Sources,” reprint in eadem, Form and Order in Medieval France: Studies in Social and Quantitative Sigillography (Aldershot: Variorum, 1993), Ch X, pp. 1-36, esp. p. 9, who draws attention to the characteristic seals of male ecclesiastics after c. 1300 that feature Mary and Child. |

| ↑88 | See Herbert L. Kessler, Experiencing Medieval Art, Rethinking the Middle Ages, 1 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019), pp. 111-13; and the foundational work of Louis Grodecki, “Fonctions Spirituelles,” in Marcel Aubert et al., Le Vitrail français, Musée des art décoratifs de Paris (Paris: Editions des Deux Mondes, 1958), pp. 39-54. |

| ↑89 | For the textual development of the metaphor, which is often associated with St. Bernard, but has been traced to the church father Athanasius, see Yrjö Hirn, “La verrière symbol de la maternité virginale,” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 29 (1928), pp. 33-39. https://doi.org/10.3406/bsef.1928.27929; Jean Dagens, “La métaphore de la verrière,” Revue d’Ascétique et de Mystique 25 (1949), pp. 524-32; Millard Meiss, “Light as Form and Symbol in Some Fifteenth-Century Paintings,” The Art Bulletin 27.3 (1945), pp. 175-81. https://doi.org/10.2307/3047010; and Francesca Dell’Acqua, “Between Nature and Artifice: “Transparent Streams of New Liquid,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 53/54 (2008), pp. 93-103 at pp. 100-03. https://doi.org/10.1086/RESvn1ms25608811 |

| ↑90 | Carla Gottlieb, The Window in Art: From the Window of God to the Vanity of Man: A Survey of Window Symbolism in Western Painting (New York: Abaris Books, 1981), pp. 135-42; Rüdiger Brandt, “Konrad of Würzburg,” in Will Hasty, ed., German Literature of the High Middle Ages (Boydell & Brewer: Camden House, 2006), pp. 242-53. |

| ↑91 | Literally, “through the working of the colors of an image,” taken from the defense of images quoted by Pope Nicholas I in 863 and repeated in 870, in J. D. Mansi vol. 16, col. 161. Discussed in Herbert L. Kessler, “Hoc Visible Imaginatum Figurat Illud Invisibile Verum: Imagining God in Pictures of Christ,” in Giselle de Nie, Karl F. Morrison, and Marco Mostert, eds., Seeing the Invisible in Late Antiquity and the early Middle Ages: Papers from “Verbal and Pictorial Imaging: Representing and accessing Experience of the Invisible, 400-1000” (Utrecht, 11-13 December 2003), Utrecht Studies in Medieval Literacy, 14 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), pp. 291-306 at p. 305. As Kessler explains, this commentary has to do with the dynamic, mental process in viewing images that is analogous to that needed to contemplate God. |

| ↑92 | Kessler, “‘They preach not by speaking out loud,’” p. 58. For a fascinating, site-specific discussion of color in glass, see Madeline H. Caviness, “The Twelfth-Century Ornamental Windows of Saint-Remi in Reims,” in The Cloisters, Studies in Honor of the Fiftieth Anniversary, ed. Elizabeth C. Parker, with Mary B. Shepard (New York 1992), pp. 178–93, esp. pp. 188-91. |