Jennifer Borland • Oklahoma State University

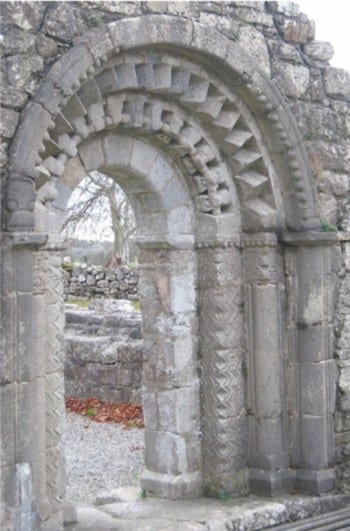

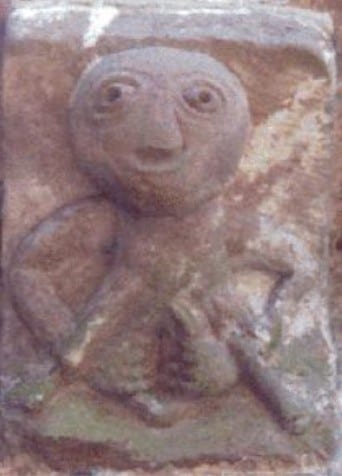

Within the ruins of the so-called Nuns’ Church, a twelfth-century building associated with the monastic complex of Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly, Ireland), a weather-beaten acrobatic figure is incorporated into the sculptural decoration of the structure’s interior arch (Figures 1-2). Located on the seventh voussoir of the third arch sandwiched between two chevrons, this figure’s bulbous head and long, splayed legs emphasize the display of her genitals to the viewer. Such a figure might not seem so unusual when considered as one example of the many acrobatic or erotic sculptures that exist on contemporaneous churches across Europe. However, this figure’s location – on an interior arch, and in a space for women – warrants further consideration.

Little is known about the Nuns’ Church, in part because of the relative scarcity of historical documents. Nevertheless, some records do indicate that there were buildings for religious women at Clonmacnoise, and scholarly investigations have generally supported this building’s association with the patronage of an elite woman named Derbforgaill.[1] Although this is by no means certain, there seem to be few concrete reasons to deny that this structure was a space associated with and used by women. This raises the question: what is the relationship between this audience and the acrobatic figure? Although several scholars in recent years have considered the traditional narratives associated with this building, little has been said about the relationship between the audience, the intimate space of this church, and its sculptural decoration. This essay argues for the possibilities that a female audience has on the meanings of the building’s decoration, and proposes a reading of the sculpture that supports such a gendered audience.

Fig 1. Exhibitionist figure, chancel arch, Nuns’ Church, Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, Ireland, c. 1167 (Photo courtesy of author)

Fig 2. Nuns’ Church as seen from the north, Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, Ireland, c. 1167 (Photo courtesy of author)

I have chosen a phenomenologically-informed approach, which allows me to read the space of the church in conjunction with its sculptural decoration as creating an enclosed environment that fosters both thoughtful contemplation and corporally-centered experiences. Moreover, the Nuns’ Church was built at a great distance from the main monastic precinct of Clonmacnoise, contributing further to the “placial” significance of the church.[2] A phenomenological approach allows us to take into consideration questions that connect to what we can actually see and experience ourselves today. Extant architectural remains, however mediated by changes over time, still share some characteristics with the original configuration, including their scale, environmental situation, and contextual landscape – why not acknowledge and use these elements to rethink such a past structure’s impact on users? Phenomenology also provides a link with medieval understandings of vision and perception as embodied and synaesthetic. And, in cases where so little is known about the object, its function, or its meaning, a phenomenological approach acknowledges and capitalizes on necessary speculation. The potential of this approach contrasts with the untenable nature of iconography for such instances, for iconography demands knowledge of “original” meanings usually based on textual sources that we often do not have. As scholar of material culture Christopher Tilley has argued in relation to the study of prehistoric landscapes, spaces, and rock art, material culture “does not necessarily require a process of decoding, or a verbal exegesis of meaning, to have power and significance.”[3] As I hope to demonstrate, the “very materiality of things” at the Nuns’ Church and the “direct agency” [4] of its curious figure are most compellingly accessed through an investigation of the way the space and the decoration connected with viewers.

The Clonmacnoise figure demonstrates an exaggeration of, or emphasis on genitalia, and in so doing, she offers her viewers a paradoxical message, one that required the viewer’s complex negotiation of the gap that exists in the image between authority and degradation. The audience members at Clonmacnoise saw in this figure a body like theirs. And they would have also seen a body that was engaged in a remarkable and possibly even shocking gesture. Craig Owens has described the power created by such stereotypical images as an apotrope precisely because of the gesture, which seems executed with the express purpose of “intimidating the enemy into submission.”[5] The power of the gesture to arrest and suspend evokes the myth of Medusa, indicating the dual power of such exhibitionist figures to both capture their audience and resist their penetration. There is indeed a capacity in this figure to arrest the viewer with her bold gesture, forcing some viewers to turn away. But we must also consider the nature of these actions, which consist not only of display or defensiveness. In her act of taking hold of the edges of her vulva, the figure controls the access to her own body.

An apotropaic aspect of this gesture, then, can be seen as a guarding or protection of the space not only through a defensive gesture that thwarts the viewer or other perceived threats. Her behavior also guards and protects the space by taking control of the openings – those of her own bodily orifices as well as that of the architectural spaces in which she appears.[6] This figure takes control of her body via the handling of her genitals, but she also controls access by exhibiting a closed mouth. The connection of such corporeal openings to the space of the building is not ambiguous. As Michael Camille has noted, “entrance points in twelfth-century churches were dangerous intersections of inner and outer, described in terms of bodily metaphors like orifices, eyes, and mouths.”[7] According to Camille, mouth motifs in architecture, which are seen at the Nuns’ Church in abundance (biting beasts, ingesting figures, and even the dental references created by the chevrons), achieve “meaning” on a decidedly somatic, rather than semantic, level. Such figures provoke an experience of one’s own presence – through their actions that connected at once to the viewer’s own body, creating a protected space made “safe” for such phenomenological experiences.

It has been commonly put forward that Christianity thrived, especially in the British Isles, largely because it assimilated and integrated many facets of the pre-Christian “pagan” cultures, rather than prohibiting them outright. Many of these groups wore animal emblems on their clothing, integrated complicated interlace or beasts onto their weapons, and even tattooed their own bodies — all for the purpose of the protection such images would grant them. These kinds of apotropaic functions continued throughout the Middle Ages. For example, the metal badges worn by pilgrims and others in the later Middle Ages served as souvenirs of shrines visited and pilgrimages taken, the representations of the cross, saints, beasts, or even more “vulgar” imagery continuing to protect the wearer long after the journey had ended (Figure 3). [8]

Fig 3. Vulva-Pilgrim Badge, 14th-15th c., France (Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague, inv. no. 5774; photo: Gabriel Urbánek)

An apotropaic reading offers one of the most productive paths to the figure’s interpretation, particularly because it acknowledges an active form of exchange between image and viewer, one that can be tied to the power of a space to exert presence and foster experience.

In the words of Henri Lefebvre, “bodies themselves generate spaces, which are produced by and for their gestures.”[9] We may interpret this as an argument that a space is not just constructed on an intellectual, symbolic level; the bodies within that space help to define its meaning. Camille’s argument is also supported by numerous medieval authors. Suzannah Biernoff has found evocations of the body as a “vulnerable architectural edifice” in a variety of sources, including the work of Bernard of Clairvaux, as well as in Robert Grosseteste’s Chateau d’amour (pre-1253) and the Ancrene Wisse.[10] For example, Bernard characterizes the senses as windows, permeable and susceptible to contamination, even actively receptive through the “roving eyes, the itching ears, the pleasures of smelling, tasting, and touching.”[11] Only with death will “all the gates of the body by which the soul has been used to wandering off to busy itself in useless pursuits and to go out to seek the passing things of this world will be shut.”[12] This trajectory leads Bernard to use the theme of enclosure to cut off the senses, arguing that one should “close the windows, fasten the doors, block all entry carefully” in order to protect the body from sin.[13]

Such perceptions portrayed the eyes as both penetrating (the evil eye, often characterized as feminine) and particularly open, left so by one’s failure to protect or close off this opening.[14] Certainly such notions can be associated with figures like the one at Clonmacnoise, where she is located by a portal and in a building created for women. Indeed, associations with liminal spaces such as portals include dangerous ambiguity, but also power.[15] But the loaded associations between architectural spaces and the female body are complicated by medieval discourses.

In Biernoff’s words, “the concept of enclosure and its transgression depends on a cultural understanding of embodied femininity as both bounded and permeable.”[16] There is an inherent contradiction in this formula and the discourses that inform it, for is constructs an ideal that is cloistered and contained, but that nevertheless remains capable of expanding outwards, particularly through vision. In the Ancrene Wisse, a thirteen-century text intended to guide anchoresses, or women who have chosen to live as recluses, the reader is urged to keep herself enclosed, “blind to the world,” and yet the anchoress’s vision remains a means of motility, “to reach out, grasp, or caress,” and is perceived as dangerous because “it transforms the anchorhold into an ‘unwalled city.’”[17] At Clonmacnoise we have an example of a literal edifice that delimits a space designated for women but also facilitates their visual activity and corporeal experiences once inside.

The main entrance of the Nuns’ Church displays decoration that can be perceived as warding off evil, and possibly even discouraging the presence of members of monastery’s male population. Such gendered boundaries may have been difficult for the women to maintain if men wanted to or needed to enter;[18] for instance, clerics would have entered the space to administer the sacraments to the nuns. However, inside this small church, the decoration offers something other than containment or immobility. It is as though the inside of the church, distinct from the outside world, becomes a privileged interior for freedom of movement.[19] Those women would have been relatively free to move about the space of the church, potentially unencumbered by the societal limitations made upon not only their movement, but also their vision. For if we acknowledge the corporeality of sight, evident in medieval theories of vision, as an extension of the body, then we must accept that medieval “vision – like the flesh – exceeds the boundaries of the body.”[20] In the space of a church like Clonmacnoise, the figure’s “ocular body” suggests to viewers not only the physicality of seeing, or the embodied nature of the senses, but also the specific tangibility of moving and being moved within a specific architectural environment.

The connection between the body and its spatial surroundings is fundamental to Christopher Tilley’s kinesthetic and experiential approach, in which he builds on phenomenology’s emphasis on the intertwining of subject and object.[21] Phenomenological studies pursue the affective character of experience, acknowledging that intellectual and visual stimuli can be felt throughout the body.[22] Prompting investigations into the essence of what we experience, phenomenology provides a critical apparatus for investigating reception through the notion of a “lived-body” that experiences the world and also impacts that world, a notion that resonates with medieval materiality. For example, Iris Young has characterized late-twentieth century women as physically limited by their “situation,” keenly aware of the boundaries of their bodies and the spaces around them.[23] But within the nave space of the Nuns’ Church, the mobility of this group of religious women would have been relatively unrestricted. While the sculpture may act apotropaically to immobilize evil entities or inappropriate visitors, she also enables the sight of female viewers. Her location, in a charged space of passage, and her active gesture of guarded openness, both speak to the idea of vision as active, corporeal, and fundamentally involved with the body’s movement in space.

This paper explores how the Nuns’ Church, physically on the periphery of a larger monastic complex and yet presumably central to the experiences of a group of religious women, engaged the audience to experience the site’s liminality through the corporeality and motility of their sight. Drawing upon the work of scholars in fields such as spatial theory and phenomenology as well as medieval theories of vision and reception, I argue that the liminal spaces of the building’s portals foster a kind of “inhabited space” that accommodates both this figure and her female viewers.[24] In such a privileged space, both the viewer’s motility and vision are unrestrained by social, cultural, and even architectural boundaries. The female viewer is enabled to embrace vision in all its transgressive capacities. Especially in church spaces, the presence of such a figure speaks to the embodied nature of worship and the spatial reciprocity of looking and seeing in the Middle Ages.

The Architectural Context

The acrobatic figure at Clonmacnoise is located in one of two sculptural arches that have been reconstructed. It is clear that this figure is part of the original sculptural program for the building, attesting to her primacy as well as her role in a more complex visual and spatial configuration (Figures 1-2, 4-9). The west portal and chancel arch of the Nuns’ Church were restored by the Kilkenny Archeological Society in 1865, in what has been assessed as a very good and relatively non-invasive restoration.[25] Aside from these two arches, the rest of the church ruins have been left as low walls that articulate the building’s footprint.[26] The west portal, also the entrance to the church, is comprised of four orders – each consisting of an arch and two jambs (Figure 4).

Fig 4. Western portal, Nuns’ Church (Photo courtesy of author)

The inner arch is primarily restoration, and the two outer arches exhibit geometric designs: the outer arch is a “hood moulding” decorated with a band and large beads, and the inner arch displays a saw-toothed chevron design.[27] Some of the jambs display chevrons on their inner and outer surfaces, which join to create lozenges. The most striking element of this portal, however, is the second arch, which includes eleven original voussoirs with stylized animal heads biting on a full roll moulding (Figure 5).

Fig 5. Detail of western portal, Nuns’ Church (Photo courtesy of author)

A viewer passes through the small nave quickly (it is only 11 meters long and 5.5 meters wide) to approach the chancel arch (Figure 6). This arch is broader and taller than the church portal, and consists of four orders facing the nave and two others (rather unadorned) facing the small chancel opposite the altar. Of the four orders, three arches survive.

Fig 6. Chancel arch from the west, Nuns’ Church (Photo courtesy of author)

The inner arch has saw-tooth chevron designs on the archivolt and intrados, which meet to create the effect of hollow lozenges.[28] Both the second and third arches contain archivolt and intrados chevron designs as well. These chevrons frame a bar-and-lozenge motif in the second arch, and in the third arch lozenges are formed that contain small figures of animals and at least one human figure, the aforementioned contortionist (Figure 1). In addition to the sculptural arch, the three large capitals on either side of the chancel entrance contain various abstract designs such as interlace, human heads, and animals in low relief (Figure 7). Above the flat surfaces of three of the capitals, small, beasts’ heads protrude from the top of the capital.[29] Therefore, the sculptural programs on both the church portal and the chancel arch are oriented outwards towards a viewer who would have approached from the main entrance to the west.

Fig 7. Detail of chancel arch, Nuns’ Church (Photo courtesy of author)

Fig 8. Lozenges, chancel arch, Nuns’ Church (Photo courtesy of author)

Fig 9. Detail of capitals, chancel arch, Nuns’ Church (Photo courtesy of author)

Clonmacnoise (the Irish Cluain Mhic Nóis means “the meadow of the sons of Nós”) has been an important religious site in Ireland since the middle of the sixth century. The monastic center was built at the crossing of two major route- ways: the Shannon River running north-south and a band of glacial eskers (elongated, often flat-topped mounds of gravel) carrying the main east-west route across the country.[30] The monastery was founded around 548 by St. Ciarán, but only seven months after his arrival he died, at the age of thirty-three.[31] The institution nevertheless flourished after his death, and over the centuries garnered much support from local kings (the kingdoms of Meath and Connacht both bordered the site) as well as pilgrims, who came to visit the site and the relic of St. Ciarán’s hand. The site suffered numerous attacks and plundering, including at least thirteen fires, eight visits from Vikings, thirty-one attacks by Irish enemies, and six initiated by Normans.[32] A testament to the importance of the site, it recovered from most of these setbacks through extensive reconstruction. However, according to Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh the twelfth century was an “uneasy” period for Clonmacnoise, which was not at the forefront of the reform movement that swept through Ireland. The building undertaken during this period was relatively small in scale. But while the prestige of Clonmacnoise may have diminished, it remained the favored site of burial and support by the Ua Conchobair kings of Connacht.[33]

Due to its location, political support, and importance as a center of religion, learning, trade, and craftsmanship, Clonmacnoise resembled a town more than a monastery.[34] Although domestic houses and communal buildings were made of timber and therefore no longer exist, there was a substantial community of lay people associated with the institution. Evidence for the thriving artistic legacy of Clonmacnoise includes the carving of several high crosses and numerous grave slabs that remain on the site.[35] The architectural ruins include seven churches, two round towers, and a castle, the dates of which range from the tenth through the seventeenth centuries. Several of the places of worship are small buildings built in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, and among these is the Nuns’ Church.

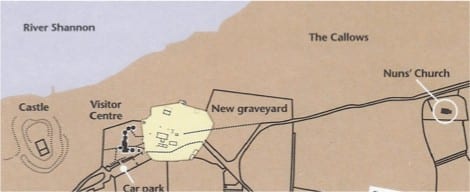

The specific location of the Nuns’ Church, far from the main precinct, seems to suggest that it was perceived as a space quite different from the others on the site. The complex’s many other church ruins, crosses, and round towers are relatively close together in a centralized organization, enclosed and protected by a stone wall. However, the Nuns’ Church, from its eleventh-century beginnings, was located at a significant distance from the rest of the precinct, exposed and unprotected some 500 meters away from the main group of buildings (Figures 10-11).

Fig 10. Site map showing the distance between, Nuns’ Church and main site, Clonmacnoise (Image detail from Clonmacnoise Visitor’s Guide, produced by Dúchas/The Heritage Service)

Fig 11. Today’s path between Nuns’ Church and main site, Clonmacnoise (Photo courtesy of author)

The distance between the church and the rest of the site is significant, requiring a walk of several minutes, long enough to make palpable the physical space that separated the nuns in their mini-precinct from the main site.

The practices of the nuns at Clonmacnoise probably played a role in both the plan of the building and its sculptural program. The nave-and-chancel plan was relatively common in twelfth-century Ireland, a simple design that was nevertheless highly functional.[36] Within the immediate space of the Nuns’ Church, however, we have no evidence of the organization of a larger configuration involving a cloister or other buildings; all that remains are the ruins of the church itself. Nevertheless, John Bradley suggests that the Nuns’ Church may have been the center of a “suburban settlement,” as is “suggested by the reference in 1082 to the destruction of the houses at the churchyard of the Nuns.”[37] The local lay community may also have had access to the church space, as well as the male clerics needed for the administration of the sacrament.[38] While the original site plan itself remains largely inaccessible, the sculptural program of the Nuns’ Church has been preserved well enough to provide some insights into the objectives behind the church’s construction and the community for which it was built.

According to the Annals of the Four Masters, the so-called “Nuns’ Church” was “completed” by a woman named Derbforgaill in 1167.[39] Derbforgaill was the daughter of Murchad Ua Máelsechlainn, king of Meath, who was a key patron of Clonmacnoise, and wife of Tigernán Ua Ruairc of Breifne. As Ní Ghrádaigh has pointed out, few patrons are known from twelfth-century Ireland, and thus having Derbforgaill’s name associated with this building is remarkable.[40] Records also mention her association with the Cistercian foundation at Mellifont to which she gave a gift of altar clothes, a gold chalice, and gold in 1157, and to which she retired in 1186 before dying in 1193.[41] Although there is no direct evidence of a nunnery at Mellifont, Dianne Hall suggests that Derbforgaill’s retirement indicates that women were admitted in some capacity.[42] Her family ties also extended to nearby Clonard, where her sister Agnes was abbess of an Arrouaisian nunnery. Most nuns’ communities in Ireland were affiliated with the Arrouaisian order by the thirteenth century. This pattern follows St. Malachy’s founding of numerous nunneries after a visit to Arrouaise (France) in 1139- 1140.[43] The Arrouaisian order was a stricter and more contemplative version of those based on the Augustinian rule, one that was less structured in Ireland due in part to the relative independence of houses from continental motherhouses or chapters.[44]

Several scholars have interpreted Derbforgaill’s acts of patronage as reflecting the political power of her family, and thus her own wealth, rather than that of her husband.[45] Although the dating of the Nuns’ Church and thus Derbforgaill’s contribution have been debated, Ní Ghrádaigh’s recent work provides a convincing argument for the likelihood of both the building’s completion date of 1167 and Derbforgaill’s role in it.[46] For instance, at Clonmacnoise the church for nuns was granted by Derbforgaill’s father to the community of Arrouaisian nuns at Clonard (where her sister was abbess) in 1144, and both of these institutions appear to have had nuns’ communities since the eleventh century.[47] Thus Derbforgaill’s patronage falls in line with her family’s general interest in supporting Clonmacnoise.

Derbforgaill has also been tied to another event that has been connected to her personal wealth as well. In 1152, she was “abducted” from her husband Ua Ruairc by Diarmait Mac Machada, [48] and this episode has been linked in popular culture to the eventual invasion by Mac Machada’s allies, the Anglo-Normans, in 1169. In some literary traditions, the abduction (or elopement) was constructed as an event that caused a conflict between these two men and eventually led to the invasion; as such, her patronage at Clonmacnoise has occasionally been read as a form of penance.[49] But the relationship between Derbforgaill’s abduction years earlier and the later invasion has been disputed by many scholars.[50] At any rate, several annals make a point of stating that some of her own possessions stayed with her during these events.[51] Ní Ghrádaigh argues that the presence of the Anglo-Normans, in fact, may have been one of the reasons Derbforgaill retired to Mellifont instead of Clonmacnoise, for the Anglo-Normans displayed more respect for Cistercian monasteries than those of the Arrouaisian tradition, as indicated by repeated sacking of Clonmacnoise in the late 1170s.[52]

Therefore, many scholars recognize adequate support for the presumption that this building was intended for nuns and that Derbforgaill was a patron of the structure. A female patron and religious women as users together reinforce the reading of this space as particularly feminized, as does its isolated location.[53] The organization at Clonmacnoise displays a significant gap between the main site and the area surrounding the Nuns’ Church – an area we can assume also contained living quarters for both the nuns and affiliated lay women.[54] In contrast to nunneries that are deeply enclosed spaces, this church represents an instance of exclusion (from the main monastic precinct) rather than enclosure.[55] What is the difference between the isolation of enclosure and that of exclusion? As we will see when we explore the Nuns’ Church alongside other examples of nuns’ spaces, these two forms of separation may have existed simultaneously to create remarkably complex and contradictory experiences. Was this a space where religious women were under less scrutiny and/or had greater independence? The genders of both the patron and likely audience of this building have further implications for understanding how the structure was used and perceived.

The situation at Clonmacnoise is especially useful for accessing how the audience might have related to this acrobatic figure and her surrounding spaces. The church was not only used by a particularly small group of women, but it was presumably planned with an audience of religious women in mind, and this knowledge is key to a better understanding of the complex relationship between the building, its sculpture, and its female audience.

The rest of the sculptural program of the chancel arch renders the figure both more enigmatic and more complex than when she is considered independently. Perhaps most provocative of all is the effect created by the meeting chevron designs in the second arch, best identified as a series of bars and lozenges (Figures 7-8). The diamond-shaped lozenges in this series do not simply exist as conjoined chevrons; they also contain small lines that curve together to form a shape reminiscent of a mandorla. Prevalent in medieval imagery as a shape that cradles a seated Christ, often a Christ in Majesty enthroned in heaven and looming large in the top half of an image, it is also the shape of Christ’s wound as well as that of women’s reproductive parts. It is not difficult to see the evocative resonances between the depiction of a vulva and the diamond-shaped lozenges here at Clonmacnoise.[56] This peculiar, essentially unprecedented imagery is worth noting precisely because of the female audience for which it is intended.[57]

The exhibitionist figure and the accompanying vulvae mark the space between the nave and chancel, the chancel admittedly a zone into which the nuns were probably not allowed. Should we read the chancel as a sort of womb, then, one that is off limits to this audience of women? According to Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg women were often denied access to sacred spaces, a position that stemmed from their perceived pollution.[58] However, she also points to evidence that there were significant difficulties in putting such prohibitions into practice, as women often refused to follow strictures and transgressed boundaries set up to keep them out of sacred space. Regardless of whether these women entered the chancel, the sculptural elements face the nave and are most meaningful to the viewers seeing it in that space, whereas the opposite side of the chancel arches was left unadorned.

If the chancel is read as an inaccessible womb, we might be tempted to link it to the idealized body of the Virgin Mary. [59] Although Hall includes the Nuns’ Church among those dedicated to Mary in her catalogue of Irish nunneries, the date of this dedication is unclear.[60] Peter O’Dwyer suggests that Augustinian and Cistercian churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary begin to appear in Ireland around this time, but specifically after the arrival of the Anglo-Normans.[61] Based on this evidence, it seems probable that the Nuns’ Church was rededicated at a date after its original construction, and this is supported by the building’s decoration. An androgynous, empty body, rather than any kind of Marian imagery, is more appropriate for both the sculptural program as a whole, and the audience using this church.

The nuns who used the Nuns’ Church were women, yes, but they were women who had chosen celibacy and at least some form of enclosure; they were removed from much that defined secular female life – marriage and motherhood. This figure was placed in a context that belonged to the realm of celibate religious women. Her androgyny may have spoken directly to the particular asexuality that was experienced by these nuns.[62] This androgyny is only one several aspects of the figure that reiterate the ambiguities of her display.

Inside the church, some jambs display evidence of interlace, while the capitals are decorated with a range of interlace and other patterns, as well as both human and bestial heads. From manuscript decoration to metalwork, interlace and animals (especially combined) served to protect the owner, resident, or wearer. Interlace works this way in part through confusion or distraction, losing the (potentially hostile) viewer in contemplation of, or even “focused reflection upon,” the complex design.[63] The inner set of capitals is decorated with stylized animal heads that appear to swallow the jambs below and the plant-based design on the capital itself (Figure 9). The second set contains abstract human heads surrounded by an X pattern, and the third set displays intricate interlace and designs in the Urnes style of ornament.[64] Along with the interlace, the idiosyncrasies of each arch, all of which contain complex patterns of small elements that are difficult to discern, may have contributed to this kind of thoughtful contemplation.[65] On the one hand, such complexities may have functioned apotropaically, by blocking access and creating confusion; on the other hand, they also may have served to promote pause and reflection. In the context of the Nuns’ Church, the figure joins in the apparent contradiction of these many-layered images, fostering both resistance to outside threats and engaged contemplation in a protected space.

The Clonmacnoise figure’s position is also significant: she is low enough on the arch to be readily seen (Figure 6). The position of the figure places her in a more visible and accessible location within the arch. As result, she is notably marginalized from the central position directly above the chancel entrance. This location provides another reason for the value of a phenomenological-informed approach, for in this case, the visual and spatial availability of this image to the audience, despite it ostensibly marginal status, contradicts an iconographic reading that interprets centrality as a marker of importance. Located in a place of feminine worship and contemplation, she could have conjured thoughts about both the power, and shamefulness, of overt corporeal display. Such an image also may have served to create a sense of security. The collective apotropaic display at the Nuns’ Church, which involved not only the exhibitionist but also the interlace patterns and beasts, worked together to both defend and protect, to both draw in and push away.

The figure’s actions were oriented in a particular direction, towards an audience and with a particular spatial understanding of visual experience in mind, which is particularly evident through a kinesthetic approach to understanding experience. Medieval debates about intromission and extromission demonstrate that vision was seen as an active exchange between viewer and viewed, one in which the physical space that existed between the object and the viewer was involved. The theory of extramission involved “the idea that a beam of light radiates outward from the eye illuminating what it falls on, ” while intromission was the idea “that all matter replicates its own image through intervening media until the image strikes the human eye.”[66] This understanding was evident in the phenomenon of multiplication of species, which referred to “the natural property of matter to replicate its image through space.”[67] For example, intromission required the power of things to reproduce images of themselves through the process of species striking the eye and entering the mind.[68] In the case of figures like the one at the Nuns’ Church, the exchange between an image and its audience was actually an exchange between two bodies in the spatial context. It is precisely this notion that seeing is a process of engagement in physical space that supports a reading which prioritizes the experience viewers might have had with the sculpture. Thus, the figure does not engage viewers solely through her provocative gesture. She also created a particularly physical exchange – as a three-dimensional entity positioned within an architecturally-defined space.

Broader Contexts

As many spatial theorists have explored, our engagements with spaces are not static but all encompassing, integrated with our senses and our bodies. Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s work, Phenomenology of Perception, is often key for scholars exploring the physical, experiential aspects of perception. Of course, he raised questions specific to his particular, mid-twentieth-century context. Since then, a variety of authors have taken up the opportunity to explore his ideas in their own work. In this essay as well, I use certain concepts presented by Merleau-Ponty as points of departure for how we might think about the nature of medieval spatial experience. According to Merleau-Ponty, “to be a body, is to be tied to a certain world…our body is not primarily in space: it is of it.”[69] Yet while bodies are central to the creation of meaningful spatial experience, they are also subject to such spaces, for “space commands bodies, prescribing or proscribing gestures, routes and distances to be covered.”[70] This tension, between the limitations created by architecture and the spatial experiences of bodies moving through its spaces, is particularly evident in medieval religious architecture. Furthermore, the sculptures and other decoration on buildings had an important role in mediating, even intervening into, the experience of medieval architectural space. Architectural remains often provide us today with a sense of a space as it once was, fostering contemplation of experiential factors such as the scale of the building, the physical movement required on the part of the user, or how sculptural decoration compelled or inhibited viewers in particular ways. The boundaries between spaces, and between body and place, are always permeable, especially, as Hall points out, when life necessitated a more flexible construction of enclosed space.[71]

In her book on women and the Church in medieval Ireland, Hall explains the relative paucity of records and resources available, but nevertheless argues that Irish nuns and their lay sisters were vital participants. Due in part to these circumstances, she advocates for the use of architectural remains as evidence.[72] Furthermore, many of her examples are supported by very similar conditions and phenomena in concurrent trends in England and France. For this reason, she frequently cites research on these other geographic regions, such as Roberta Gilchrist’s archeological study of (primarily English) medieval nunneries.[73] Gilchrist has demonstrated that the planning and manipulation of the many spaces within religious complexes were highly deliberate. The spatial segregation of women may have been intended to ensure chastity (of both men and women), but it also reflected the separation of men and women in the secular domestic domain, a separation that was both familiar and practical to women living in castles as well as nunneries. We may be inclined to interpret such gender-based segregation as a means by which women were “controlled and alienated,” but Gilchrist points out that “the tendency for spatial segregation of women is apparent even where women have been active in commissioning their own quarters.”[74] At the same time, spaces for women were also most certainly permeable in both directions, especially as nuns often interacted with the outside world through service to the community and family ties.[75]

Monastic complexes undoubtedly reflect the consideration of gender in determinations about how space was constructed and who would have access to which areas, and often include physical boundaries to maintain separation of different groups. For instance, the archaeological study of nunneries has shown that they have more physical boundaries between the precinct and the inner cloister than do monasteries. The dormitories of religious women tend to be the most secluded space in a nunnery.[76] But at the same time, Hall points out that “although nunneries were probably in relatively secluded positions, these positions were usually within the reach of populous areas, suggesting that it was in these areas that the need for nuns and their services was felt and that resources were sufficient to support nunneries.”[77] The location of the Nuns’ Church at Clonmacnoise seems to reflect these contradictions, where the church itself was in set aside in an external suburb, but that location may have simultaneously allowed flexibility in the boundaries between the nuns’ spaces and the outside world.

Such a spatial divide may have contributed to feelings of both exclusion and increased independence. Under reduced scrutiny from the monastery, the nuns may have exercised greater freedom in their prayers, rituals, and daily life than in the average convent. Women’s religious institutions throughout the Middle Ages were less well funded than those of men, and in cases where the two were conjoined, the convent or nunnery would have been largely dependent upon the male monastery.[78] But as Gilchrist points out, women’s communities may not have been expected to function in the same way as their male counterparts:

If nunneries looked different from monasteries, were placed in different landscape situations, and were never endowed in order to achieve self-sufficiency, this is because medieval patrons had a different purpose in mind for medieval religious women.[79]

It seems that many such nunneries were developed in order to engage with and support the local community, [80] and such a community would have been substantial at Clonmacnoise. This form of outreach also complements the Augustinian beliefs upon which the Arrouaisian order of nuns at Clonmacnoise was based.[81] Moreover, the Arrouaisian order is known for its relative independence.[82] Therefore, the active, local work of the nuns around the area of the Nuns’ Church may be one reason why the area was created at such a distance from the rest of the complex.

As an Irish foundation established for women, Clonmacnoise does not seem especially unique.[83] Although Clonmacnoise’s Nuns’ Church was apparently founded in the eleventh century, it was eventually associated with what Hall calls “The Clonard Group,” or the first Arrouaisian network of nunneries.[84] The establishment of this system, and of general expansion over the course of the twelfth century, suggests much in common with the explosion of nunneries across Europe at this time. Within art history or architectural history circles, however, the complex at Clonmacnoise is also sometimes compared with the Irish foundations of Glendalough and Cashel. And several scholars have pointed out parallels between elements at Rahan and the Nuns’ Church as well as Rahan’s architectural links to Cashel (especially Cormac’s Chapel) – links that might indicate a shared workshop.[85] Karen Overbey suggests further that Derbforgaill may have had a hand in Rahan’s patronage, about which nothing is documented.[86] However, these other complexes do not appear to have had women’s spaces, perhaps in part because they functioned as diocesan as well as abbatial centers and women would have ostensibly had access to these cathedrals. Furthermore, examples like Cashel were associated with reform and expansion (and support from Anglo-Norman reformers) while Clonmacnoise reflects a different twelfth-century trajectory. As Ní Ghrádaigh has articulated so strongly, the Nuns’ Church fits well into the artistic period as a solid example of Irish Romanesque, but the aesthetic connections between this building and those of other contemporary foundations must also acknowledge the very different issues of building use and patronage.[87] Perhaps the small scale of this building, and its “problematic” patronage are precisely why scholars have been inclined to discuss it only as a comparative example to other, better known complexes.[88]

The Sheela-na-gig Tradition

The figure at Clonmacnoise has been interpreted as a problematic example of a Sheela-na-gig, and regardless of whether or not we should consider her as such, the scholarly discourses around Sheela-na-gigs are worth touching upon, if only to demonstrate the ways that most of the interpretations remain inadequate for the figure at Clonmacnoise. The term Sheela-na-gig refers to a group of sculptures with notable characteristics: disproportionately large genitals, gripped and displayed by her own hands; small, coarsely rendered breasts; emaciated, scarred body; direct and aggressive gaze (Figures 12-13). [89]

Fig 12. Sheela-na-gig, Church of St. Mary and St. David, Kilpeck, Herefordshire, England, c. 1134-1140 (Photo courtesy of author)

Fig 13. Sheela-na-gig, All Saints Church, Oaksey, Wiltshire, England, 13th(?) c. (Photo courtesy of author)

They appear in a variety of architectural contexts primarily in Ireland and England, first emerging in the eleventh or twelfth century and continuing through the sixteenth century. [90] These sculptures have no textual sources and have been difficult to date, both factors contributing to scholars’ difficulties in understanding them. The scholarship on Sheela-na-gigs has pursued a number of different paths in order to access the enigmatic meaning of these sculptures, most of which rely on an iconographic approach that remains unsatisfying on its own. There have been investigations into the Celtic or pagan past, through ancient stories that involved aggressive and powerful women. This connection often suggests that Sheelas were relics of an earlier Celtic age, powerful hags who were sexually voracious and politically authoritative. [91] These associations have also led some scholars to link these Celtic resonances with even earlier female imagery – prehistoric and ancient goddess figures that represent fertility and earth.[92] Anne Ross and Patrick K. Ford have found provocative resonances between the antics of powerful warrior women in early Irish narratives and the Sheela-na-gig figures.[93] But these approaches often fail to take into account the sculptures themselves, which so often reside in the particularly Christian context of the church. In fact, the few surviving in-situ figures are not relegated to the peripheral spaces of the decorative design, but are often central to the building’s organization. This dichotomy highlights one of the tensions inherent in the Sheelas: while they can be associated with imagery that is often considered outside the official realm of the Church, in many cases they are presented as a central part of individual churches’ decorative systems.

Efforts to find a place in the Church for such figures has led several authors to argue that the Sheela was a representation of the sexual sin, akin to Eve.[94] For example, in their book Images of Lust, Anthony Weir and James Jerman attempt to place the Sheelas within a larger (primarily French) Romanesque context that includes other sexual carvings such as luxuria (female allegorical figures representing lust), femmes-aux-serpents, exhibitionists, hybrid creatures, mouth-pullers, and other rude figures.[95] This approach leads them to understand the Sheelas primarily as images of sexual sin. While acknowledging the provocative interconnections between Sheelas and their continental counterparts, this method distances the sculptures from their immediate physical as well as geographic context. And the aggressive, confrontational posture displayed by most Sheela-na-gigs suggests neither lust nor shame. While visual connections to a broader European context are undeniable and potentially illuminating, the search for a specific source from which the Sheela-na-gig was derived is misguided and ultimately unfruitful.

More recent investigations have begun to consider the connection between these images and female reproduction, especially in light of local audiences and their religious and secular lives.[96] In particular, Marian Bleeke’s approach to the figure at Kilpeck (Herefordshire, UK), which considers the Sheela as part of a large sculptural program that reflects the surrounding spaces of the church and their uses, is one of the most spatially aware and thus convincing arguments to date (Figures 12, 14).[97] But inevitably, the search for a tidy answer to the question “what do they mean?” is fundamentally impossible. [98]

Fig 14. Church of St. Mary and St. David, Kilpeck, Herefordshire, England, c. 1134-1140 (Photo courtesy of author)

This is why consideration of the audiences that viewed Sheela-na-gigs is central to uncovering meanings beyond that of monstrosity or sinfulness. Dating has been impossible for many ex-situ sculptures, and even some in-situ figures are now located in buildings to which they are not original. Although these reused Sheelas shed light on the motivations and beliefs of their later medieval owners, they provide little idea of original context. But some examples stand out because of their presence in fairly well-preserved twelfth-century buildings. For example, the figure from the church at Kilpeck serves as an exemplary figure because it was original to the building’s twelfth-century design (Figures 12, 14). Although it has been proposed, the Clonmacnoise figure cannot be considered an early prototype to the series because she dates later than other examples (including Kilpeck). Even her femaleness has at times been put into question. But Catherine Karkov suggests that we approach the category of Sheela less literally:

…as the main message of the Sheela-na-gigs lies in the open threatening body, and as the figures frequently combined clear gender signifiers (the vulva) with signs of genderless ambiguity (monstrous faces, bald heads, skeletal torsos), the Clonmacnoise acrobat is clearly in the same tradition.[99]

Indeed, this small figure lifts her legs to display the genitals, and although the vulva is less pronounced than most Sheelas (the result of both weathering and the figure’s small size), the figure does not brandish anything resembling a male member. And as Karkov observes, her face is genderless and a little grotesque, if not exactly monstrous.[100]

Most Sheela-na-gigs confront the viewer so forcefully that they may have even served to defy the gaze — forcing the viewer’s eye away from the image through its directness, its lack of inhibition, its physicality. Indeed, the power of these images resulted in part from their capacity to be simultaneously engaging and repulsive, engrossing and disturbing. The apotropaic display demonstrated by the Clonmacnoise figure links her to other Sheela-na-gigs and their capacities to both engage and resist their viewers. At the same time, her specific characteristics and context undermine the broader associations with sexual voracity and monstrosity.

Conclusion

The exhibitionist figure and her sculptural context in the Nuns’ Church at Clonmacnoise provide a remarkable instance in which a conventional building simultaneously offers a compellingly unique environment for visual and spatial experience. Rather than considering this figure as a Sheela-na-gig, with all of that term’s accompanying archetypal associations, I have asserted that the context and placement of the figure are what motivated the construction of a gendered space that is specific to this building, while allowing for the importance of audience in the production of meaning. In a very real way, the building “creates” an interpretation of the sculpture, and in so doing, asserts “the direct agency of the imagery” that ought to be more central to our understandings of medieval visual culture.[101] My phenomenological approach works here because it focuses on the specificity of this building and its sculpture instead of generic traits that limit interpretation. In the end, the powerful relationship between an image and its past viewers is never really accessible. But if we accept this and consider new paths for exploration, we might just allow for thoughtful communication between past and present that is based on the intimate experiences of a shared space.

This essay greatly benefitted from the suggestions of the two anonymous readers for Different Visions, as well as comments from Louise Siddons. I also thank Suzanne Lewis for feedback at an earlier stage of the project.

References

| ↑1 | The Irish Annals referenced throughout this essay include the Annals of the Four Masters (AFM), Annals of Clonmacnoise (AClon), Annals of Ulster (AU), and Annals of Loch Cé (ALC). The commonly used translations include John O’Donovan, ed. Annala Rioghachta Eireann. Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland (Dublin: Hodges and Smith,1851); Denis Murphy, ed. The Annals of Clonmacnoise (Dublin: University Press for the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 1896); Seán Mac Airt and Gearóid Mac Niocaill, eds. The Annals of Ulster (Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1983); W. M. Hennessey, ed. Annals of Loch Cé (London: Longmans, 1871). While the accuracy of these sources has sometimes been questioned, especially the Annals of the Four Masters which is a seventeenth-century compilation, most scholars whose work on Clonmacnoise and Derbforgaill I cite have found few reasons to doubt the general reliability of these sources. One reason may be that often events are documented in more than one of these annals. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Christopher Y. Tilley and Wayne Bennett, Body and Image: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology II (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2008), 17. Tilley proposes the alternative term “placial” because he finds it “less abstract and distanced” than the term “spatial.” |

| ↑3 | Ibid., 37. |

| ↑4 | Ibid., 48, 46. |

| ↑5 | Craig Owens, “The Medusa Effect, or, the Specular Ruse,” Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture, eds. Barbara Kruger, Scott Bryson, Lynne Tillman, and Jane Weinstock (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992) 194. |

| ↑6 | I thank Suzanne Lewis for helping me articulate this notion. |

| ↑7 | Michael Camille, “Mouths and Meanings: Towards an Anti-Iconography of Medieval Art,” in Iconography at the Crossroads, ed. Brendan Cassidy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 48. |

| ↑8 | Denis Bruna, Enseignes de pèlerinage et enseignes profanes (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1996) and Saints et diables au chapeau: Bijoux oubliés du Moyen Âge (Paris: Seuil, 2007). |

| ↑9 | Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space (Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992), 216. |

| ↑10 | Suzannah Biernoff, Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 54-56; Robert J. Hasenfratz, Ancrene Wisse, Middle English Texts (Kalamazoo, MI: Published for TEAMS by Medieval Institute Publications, 2000); Bella Millett, Ancrene Wisse – Guide for Anchoresses: A Translation Based on Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Ms 402 (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2009). |

| ↑11 | Bernard of Clairvaux: Selected Works, trans. G. R. Evans (New York: Paulist Press, 1987), 72; Biernoff, Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages, 54. |

| ↑12 | Bernard of Clairvaux: Selected Works, 71. |

| ↑13 | Ibid., 73. |

| ↑14 | On the evil eye, see: Robert S. Nelson, Visuality before and Beyond the Renaissance: Seeing as Others Saw (Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 151; Biernoff, Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages, 56. |

| ↑15 | Catherine E. Karkov, “Adam and Eve on Muiredach’s Cross: Presence, Absence and Audience,” in From the Isles of the North: Early Medieval Art in Ireland and Britain, ed. Cormac Bourke (Belfast: HMSO, 1995), 209. |

| ↑16, ↑20 | Biernoff, Sight and Embodiment in the Middle Ages, 56. |

| ↑17 | Ibid; and Millett, Ancrene Wisse – Guide for Anchoresses: A Translation Based on Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, Ms 402, Part 2: 40, p. 42: “blindfold your eyes on earth.” |

| ↑18 | Dianne Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, c.1140-1540 (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2002), 168-69. |

| ↑19 | Anne Friedberg, Window Shopping: Cinema and the Postmodern (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 44, 58, 184. Friedberg suggests that in the mid-nineteenth century, department stores provided such a space to women – a public space that was also private interior. |

| ↑21 | Christopher Y. Tilley and Wayne Bennett, The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology I (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 29. |

| ↑22 | For example, see Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London and New York: Routledge, 2005, orig. 1945), 202. Feminist reassessments of Merleau-Ponty’s work have also been useful to me, including Vivian Carol Sobchack, The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1992).); Judith Butler, “Sexual Ideology and Phenomenological Description: A Feminist Critique of Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Perception,” in The Thinking Muse: Feminism and Modern French Philosophy, ed. Jeffner Allen and Iris Marion Young (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989); Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994); Iris Marion Young, “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility, and Spatiality,” in Throwing Like a Girl and Other Essays in Feminist Philosophy and Social Theory (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990). |

| ↑23 | Young, “Throwing Like a Girl,” 144. Young is working here with Simone de Beauvoir’s theory of the situation of women. |

| ↑24 | This phrase is borrowed from Sobchack, The Address of the Eye, 9. In addition to Sobchack, feminist critiques and reassessments of Merleau-Ponty’s work have been offered by scholars including Butler, Grosz, and Young. Other work that has informed my thinking includes Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984); Victor Witter Turner and Edith L. B. Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978); Bissera Pentcheva, “The Performative Icon,” The Art Bulletin 88, no. 4 (2006). |

| ↑25 | Tadhg O’Keeffe, Romanesque Ireland: Architecture and Ideology in the Twelfth Century (Dublin: Four Courts, 2003), 262; Kenneth MacGowan, Clonmacnois (Dublin: Kamac Publications, 1991), 30. This is in notable contrast to many well-known “restored” medieval buildings in France (Vézelay, Notre-Dame de Paris). |

| ↑26 | Part of the east window also survives. |

| ↑27 | For an extensive and detailed description of all these elements, see O’Keeffe, Romanesque Ireland, 262- 64, and Jenifer Ní Ghrádaigh, “‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’ Derbforgaill and the Nuns’ Church and Clonmacnoise,” in Clonmacnoise Studies: Seminar Papers 1998, ed. Heather A. King (Dublin: Dept. of Environment Heritage and Local Government, 2003). |

| ↑28 | O’Keeffe, Romanesque Ireland, 264. |

| ↑29 | These include the outer capitals and the center capital on the left; the other center capital is missing this element, and the center capitals appear to be topped with different, snail-shell bosses that nevertheless echo the protruding heads. |

| ↑30 | Frances McGettigan and Kevin Burns, “Clonmacnoise: A Monastic Site, Burial Ground, and Tourist Attraction,” in Cultural Attractions and European Tourism, ed. Greg Richards (Wallingford, UK and New York: CABI Publishing, 2001), 139. |

| ↑31 | Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, The Memorial Slabs of Clonmacnois (Dublin: University Press, 1909), 112. See also John Ryan, Clonmacnois: A Historical Summary (Dublin: Stationery Office, National Parks and Monuments Branch, Office of Public Works, 1976); MacGowan, Clonmacnois. |

| ↑32 | Macalister included a list of recorded events in the history of Clonmacnoise; Macalister, Memorial Slabs, 112-27. |

| ↑33 | Ní Ghrádaigh, “‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 176, and Raghnall Ó Floinn, “Clonmacnoise: Art and Patronage in the Early Medieval Period,” in Clonmacnoise Studies Volume I: Seminar Papers 1994, ed. Heather A. King (Dublin: Dúchas/The Heritage Service, 1998), 97-98. |

| ↑34 | John Bradley, “The Monastic Town of Clonmacnoise,” in Clonmacnoise Studies Volume I: Seminar Papers 1994, ed. Heather A. King (Dublin: Dúchas/The Heritage Service, 1998). |

| ↑35 | See Ó Floinn, “Clonmacnoise: Art and Patronage.” |

| ↑36 | O’Keeffe, Romanesque Ireland. |

| ↑37 | Bradley, “The Monastic Town of Clonmacnoise,” 46. Bradley cites AFM, 1082 and AClon, 1080. |

| ↑38 | Jane Tibbetts Schulenburg, “Gender, Celibacy, and Proscriptions of Sacred Space: Symbol and Practice,” in Women’s Space: Patronage, Place, and Gender in the Medieval Church, ed. Virginia Chieffo Raguin and Sarah Stanbury (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2005), 193. |

| ↑39 | AFM. |

| ↑40 | Ní Ghrádaigh, “‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 177. |

| ↑41 | Ibid. The 1157 donation is cited in AFM, her retirement from AU and ALC, and her death the AU and AFM. |

| ↑42 | Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 79. |

| ↑43 | Ibid., 66-74, and Roberta Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture: The Archaeology of Religious Women (London & New York: Routledge, 1994), 40. |

| ↑44 | Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 68. |

| ↑45 | Including Ní Ghrádaigh, Preston-Matto, Karkov, and Overbey. See also Marie Therese Flanagan, Irish Society, Anglo-Norman Settlers, Angevin Kingship: Interactions in Ireland in the Late Twelfth Century (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 92-95. |

| ↑46 | Ní Ghrádaigh, “‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 204: “I believe that it is doing the church itself an injustice, and making scholarship in the field needlessly circumspect, to doubt the entry in the Annals of the Four Masters of 1167.” |

| ↑47 | Ibid., 178. AFM: A convent outside the main precinct of Clonmacnoise was apparently erected in 1026, though in 1082 this earlier building burned; Macalister, Memorial Slabs, 116, 19; Ryan, Clonmacnois: A Historical Summary, 62-63. |

| ↑48 | AFM and AClon. See also F. X. Martin, “Diarmait Mac Murchada and the Coming of the Anglo- Normans,” in New History of Ireland: Medieval Ireland, 1169-1534, ed. Art Cosgrove (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 49-50. |

| ↑49 | Karen Eileen Overby, “Female Trouble: Ambivalence and Anxiety at the Nuns’ Church,” in Law, Literature, and Society: CSANA Yearbook 7, ed. Joseph F. Eska (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2008), 93- 112; Catherine E. Karkov, “Sheela-Na-Gigs and Other Unruly Women: Images of Land and Gender in Medieval Ireland,” in From Ireland Coming: Irish Art From the Early Christian to the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Index of Christian Art and Department of Art and Archaeology, in asssociation with Princeton University Press, 2001), 313-331 (p. 313-14). |

| ↑50 | Overby, “Female Trouble”; Lahney Preston-Matto, “Derbforgaill’s Literary Heritage: Can You Blame Her?,” in Law, Literature, and Society: CSANA Yearbook 7, ed. Joseph F. Eska (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2008); Catherine E. Karkov, “Sheela-Na-Gigs and Other Unruly Women”; Martin, “Diarmait Mac Murchada and the Coming of the Anglo-Normans,” 49-50; Flanagan, Irish Society, Anglo-Norman Settlers, Angevin Kingship, 92-95. |

| ↑51 | Ní Ghrádaigh, ‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 179-80. Flanagan, Irish Society, Anglo-Norman Settlers, Angevin Kingship, 94-95. |

| ↑52 | Ní Ghrádaigh, ‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 180. |

| ↑53 | rkov provides another example how different readings based on a gendered audience in her essay on Muiredach’s Cross; see Karkov, “Adam and Eve on Muiredach’s Cross,” 208-9. |

| ↑54 | For more on the case at Fontevraud, see Loraine N. Simmons, “The Abbey Church at Fontevraud in the Later Twelfth Century: Anxiety, Authority and Architecture in the Female Spiritual Life,” Gesta 31, no. 2 (1992). Gilchrist also cites numerous examples of “double houses” in medieval England; see Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture. |

| ↑55 | Indeed, there are instances in which a church outside a monastery’s walls might be built specifically to accommodate female visitors; see Schulenburg, “Gender, Celibacy, and Proscriptions of Sacred Space,” 194 |

| ↑56 | Of course, this evokes the prominent vulvae of Sheela-na-gigs, discussed later in this essay. |

| ↑57 | I have not come across any other example of this particular sculptural element used in medieval architecture. A similar vulvate image (although not found in architecture) has also been seen occasionally on Roman objects such as lamp-handles; see Catherine Johns, Sex or Symbol: Erotic Images of Greece and Rome (London: British Museum Publications, 1982), 58 |

| ↑58 | Schulenburg, “Gender, Celibacy, and Proscriptions of Sacred Space.” Related is the tradition of “churching,” a purification rite that was necessary before a woman who had recently given birth could reenter a sacred space; see Paula Rieder, On the Purification of Women: Churching in Northern France, 1100-1500 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006). |

| ↑59 | As Karkov points out, the open bodies of Sheela-na-gigs in general invite comparison with Mary and/or Ecclesia: Karkov, “Sheela-Na-Gigs and Other Unruly Women,” 319. |

| ↑60 | Hall does not provide a date for this dedication. Aubrey Gwynn and R. Neville Hadcock list St. Mary Clonmacnoise as a possession of St. Mary Clonard by 1195, according to William Dugdale and Roger Dodsworth, Monasticon Anglicanum, vol. ii (1673), 1043-4; see Gwynn and Hadcock, Medieval Religious Houses: Ireland (London: Longman Group Limited, 1970), 307-310, 315. |

| ↑61 | Peter O’Dwyer, Mary: A History of Devotion in Ireland (Dublin: Four Courts, 1988) 72-73. |

| ↑62 | Gilchrist mentions in passing the possible asexuality of nuns in her discussion of the telling relationship between imagery and space; Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture, 155. |

| ↑63 | Mildred Budny finds an apotropaic meaning simplistic, especially in the case of religious manuscripts; she does, however, support the notion that interlace patterns were “powerful tools to focus reflection upon the multiple layers of meaning;” Mildred Budny, “Deciphering the Art of Interlace,” in From Ireland Coming: Irish Art from the Early Christian to the Late Gothic Period and Its European Context, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Index of Christian Art and Department of Art and Archaeology, in association with Princeton University Press, 2001), 197-98 |

| ↑64 | O’Keeffe, Romanesque Ireland, 263-64. Named after the carving at a church in Urnes, Norway, the Urnes style was a popular Scandinavian-influenced style of ornamentation in the eleventh and twelfth centuries in Ireland. It is characterized by curving, biting animals and spiral designs. For an extensive architectural appraisal of the Nuns’ Church, see Ní Ghrádaigh, ‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 180- 202. |

| ↑65 | Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400-1200 (Cambridge, UK & New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998), especially Ch. 3, 116-70. |

| ↑66 | Carolyn P. Collette, Species, Phantasms, and Images: Vision and Medieval Psychology in the Canterbury Tales (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001), 15. |

| ↑67 | Ibid., 14. |

| ↑68 | Ibid., 16. |

| ↑69 | Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, 171. |

| ↑70 | Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 143. |

| ↑71 | Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 20, 159-90. |

| ↑72 | Ibid., 15-20. |

| ↑73 | Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture. |

| ↑74 | Ibid., 168. Gilchrist continues that this “thus represents an example of the way in which the female subject is both active in interpreting material culture, and complicit in being conditioned by it.” |

| ↑75 | Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 159-200. |

| ↑76 | Roberta Gilchrist, “Medieval Bodies in the Material World: Gender, Stigma, and the Body,” in Framing Medieval Bodies, ed. Sarah Kay and Miri Rubin (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1996), 56-57. See also Schulenburg, “Gender, Celibacy, and Proscriptions of Sacred Space,” and Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture. |

| ↑77 | Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 91-92. |

| ↑78 | “Double houses established in Ireland were at the forefront of ecclesiastical reform,” following similar trends taking place in England and France; Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 73. Perhaps as many as twenty-five percent of nunneries founded at this time were in some way double houses; see Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture, 38-39; Sharon K. Elkins, Holy Women of Twelfth-Century England (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988), xvii-I, 55-60; Penelope D. Johnson, Equal in Monastic Profession: Religious Women in Medieval France (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 7. |

| ↑79 | Gilchrist, Gender and Material Culture, 190. |

| ↑80 | Ibid., 191. |

| ↑81 | Hall, Women and the Church in Medieval Ireland, 66-68. |

| ↑82 | Ibid., 67. |

| ↑83 | Ibid., 63-95. |

| ↑84 | Ibid., 70-74. |

| ↑85 | Ní Ghrádaigh, “A Legal Perspective on the saer and Workshop Practice in Pre-Norman Ireland,” in Making and Meaning in Insular Art, ed. Rachel Moss (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2007), 110-125; see also Overbey, “Female Trouble: Ambivalence and Anxiety at the Nuns’ Church,” 100-01, and O’Keeffe, Romanesque Ireland, 265. Ní-Ghrádaigh also points out connections with the chancel arch at Tuam, “‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 202. |

| ↑86 | Overbey, “Female Trouble: Ambivalence and Anxiety at the Nuns’ Church,” 100-01, |

| ↑87 | Ní Ghrádaigh, “‘But What Exactly Did She Give?’,” 204 |

| ↑88 | Overbey, “Female Trouble: Ambivalence and Anxiety at the Nuns’ Church,” 112: “…ambivalence about female patronage has marginalized the Nun’s Church in architectural scholarship.” |

| ↑89 | The extant literature on Sheela-na-gigs is relatively small and represented by the following: Marian Bleeke, “Sheelas, Sex, and Significance in Romanesque Sculpture: The Kilpeck Corbel Series,” Studies in Iconography 26 (2005), 1-26; Barbara Freitag, Sheela-na-gigs: Unravelling an Enigma (London and New York: Routledge, 2004); Bleeke, “Situating Sheela-na-gigs: The Female Body and Social Significance in Romanesque Sculpture” (Dissertation, University of Chicago, 2001); Karkov, “Sheela-na-gigs and Other Unruly Women”; Joanne McMahon and Jack Roberts, The Sheela-na-gigs of Ireland & Britain: The Divine Hag of the Christian Celts: An Illustrated Guide (Cork: Mercier Press, 2001); Anthony Weir and James Jerman, Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches (London: Routledge, 1999); Patrick K. Ford, “The Which on the Wall: Obscenity Exposed in Early Ireland,” in Obscenity: Social Control and Artistic Creation in the European Middle Ages, ed. Jan M. Ziolkowski (Leiden & Boston: Brill, 1998), 179- 190; Eamonn P. Kelly, Sheela-na-gigs: Origins and Functions (Dublin: Country House, in association with the National Museum of Ireland, 1996); Stella Cherry, A Guide to Sheela-na-gigs (Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 1992); Jørgen Andersen, The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture in the British Isles (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde and Bagger, 1977); Anne Ross, “The Divine Hag of the Pagan Celts,” in The Witch Figure: Folklore Essays by a Group of Scholars in England Honouring the 75th Birthday of Katharine M. Briggs, ed. Venetia Newall (London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973), 139-164; Edith Guest, “Irish Sheela-na-gigs in 1935,” Journal of the Royal Society of Irish Antiquaries 67 (1937), 107-129. |

| ↑90 | Along with the connection between Derbforgaill and Clonmacnoise, Catherine Karkov links several other extant Sheela-na-gigs to aristocratic families; Karkov, “Sheela-na-gigs and Other Unruly Women,” 317. |

| ↑91 | Ford, “The Which on the Wall,” Karkov, “Sheela-na-gigs and Other Unruly Women,” and to a certain degree, Freitag, Sheela-na-gigs. |

| ↑92 | Andersen, The Witch on the Wall; Freitag, Sheela-na-gigs. |

| ↑93 | Ross, “The Divine Hag of the Pagan Celts,” and Ford, “The Which on the Wall.” This is also tentatively accepted by Andersen, The Witch on the Wall, 84-95. |

| ↑94 | Andersen, The Witch on the Wall.; Weir and Jerman, Images of Lust. |

| ↑95 | Weir and Jerman, Images of Lust. |

| ↑96 | Bleeke, “Sheelas, Sex, and Significance in Romanesque Sculptures,” Bleeke, “Situating Sheela-na-gigs,” and Freitag, Sheela-na-gigs. |

| ↑97 | Bleeke, “Sheelas, Sex, and Significance in Romanesque Sculptures,” Bleeke, “Situating Sheela-na-gigs.” |

| ↑98 | Although this cannot be done for all, or even most, of the Sheela-na-gigs, a few such studies may provide the foundations for a new set of more provocative questions about how and why Sheelas became so prevalent; Bleeke, “Sheelas, Sex, and Significance in Romanesque Sculpture: The Kilpeck Corbel Series.” See also Bleeke, “Situating Sheela-na-gigs”, 136. |

| ↑99 | Karkov, “Sheela-na-gigs and Other Unruly Women,” 315. |

| ↑100 | The name that now refers to these sculptures, Sheela-na-gig, or sometimes just Sheela, first appeared in the mid-nineteenth century, and is generally believed to be Irish in derivation. Nevertheless, the actual components of this name have been difficult to identify, with various interpretations including Síle na gCíoch (“Sheela of the breasts” or “old hag of the breast”) and Síle-ina-Giob (“Sheela on her hunkers” or “old woman on her hunkers”). It has also been suggested that it is an actual name: Sheela as a first name, “na” as a derivation of “Ni,” which is used for women’s names like “O” or “Mac” in men’s names, and “Gig” as a family name. Bleeke has found this last option most convincing because other personal names have sometimes been used as the local names for Sheela sculptures; also, it is common in Irish local culture to identify images as representations of specific individuals. See Bleeke, “Situating Sheela-na-gigs”, 1-2, 156-57. |

| ↑101 | Tilley and Bennett, Body and Image. Tilley’s comment reflects his engagement with W. J. T. Mitchell’s 1996 essay “What do pictures really want?” October 77: 71-82. |