Genevra Kornbluth • Independent Scholar

It may be useful to begin this essay with a very basic observation. Aside from kinetic sculpture, objects are only as active as viewers allow them to be. They shape our perceptions, and direct the physical, intellectual, and perhaps spiritual movements that we make in response to them, only insofar as we agree to be influenced. Some years ago I ordered a photograph of the Majesté de Sainte Foi (Conques) from the official archive of the Caisse Nationale des Monuments Historiques et des Sites in Paris (Figures 1a, b). When it arrived I was surprised to see a modern screwdriver held in the figure’s left hand. The screwdriver is of course not part of the reliquary, nor present in its current display or published images. A technician involved in producing the CNMHS photo must have parked his tool there temporarily, and then forgotten to remove it before the photographer began shooting. It was therefore immortalized as evidence of one viewer’s response to an object that is still the focus of regular pilgrimage, both spiritual and art historical. That one person, at least, refused to be awed. His act echoes the first response of Bernard of Angers who, before being converted by the holy power of the saints, famously regarded such figures as works of human artifice without spiritual significance: “Brother, what do you make of this idol?”[1] Other recorded responses, however, suggest that many medieval viewers did fall under the spell of religious art, and we are therefore justified in asking how they allowed themselves to be directed. This essay presents some answers based on empirical observation.

Fig. 1a. Majesté de Sainte Foi, gold, silver gilt, and gems on wooden core, front height 85 cm, ninth century and later. Abbaye de Conques, Treasury (photo: © CNMHS)

Fig. 1b. Majesté de Sainte Foi, detail (photo: © CNMHS).

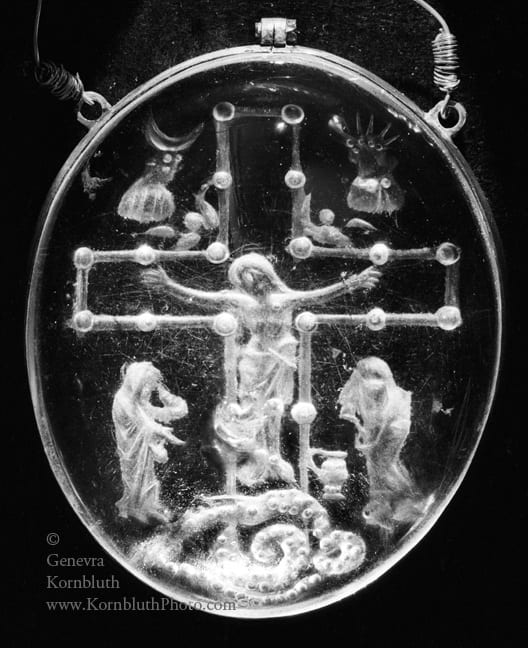

Fig. 2. Crucifixion, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse, 8.5 x 6.8 cm including mount, second quarter to mid ninth century. London, British Museum, 1867,0705.14 (photo: author).

The Carolingian gems that are the focus here have probably always been attached to liturgical objects.[2] Their imagery was engraved on rock crystal (natural quartz stone) with rotating drills and abrasive grit. They were cut in reverse because, unlike most engraved gems, the crystals were designed to be correctly legible when viewed from behind. The unengraved face of the stone, often strongly curved (cabochon), was polished smooth so that the composition is clearly visible through its transparent, colorless material (Figures 2, 3, c.825-50).[3] Although none of the original settings of the Carolingian figural crystals have been preserved, there is ample evidence that contemporary liturgical artists took advantage of the optical properties of such objects. The Ardennes Cross (c.830) has at its center a cabochon crystal (Figure 4).[4] Another major Carolingian cross, formerly in the treasury of Saint-Denis, had at its crossing a similarly large oval amethyst.[5]

Fig. 3. Crucifixion, rock crystal intaglio, side view, 8.5 x 6.8 cm including mount, second quarter to mid ninth century. London, British Museum, 1867,0705.14 (photo: author).

Fig. 4. Ardennes Cross, gold and gems on wood core, full cross height 73 cm, ca. 830. Nürnberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, FG 763 (photo: author).

Fig. 5. Book cover or case, copper gilt and crystal on wood, 31.4 x 20.3 cm, tenth century. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 528-1893 (photo: author).

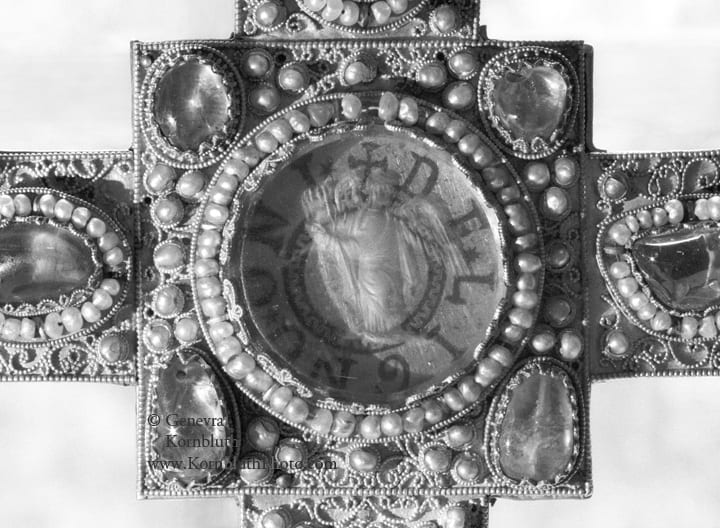

Crystals were also used on the precious covers and cases for liturgical books. A late Carolingian example in London incorporates a crux gemmata into its composition (Figure 5).[6] At the center of the cross is a cabochon crystal. Like the stone on the Ardennes Cross, this one is aniconic; but a designer nonetheless found a way to use it as part of the figural composition. The stone is placed over a repoussé head of Christ (Figure 6), and both physically protects that figure and reveals its presence. The same technical device was later used over a Crucifixion and a fragment of the True Cross on the Mondsee Gospels cover (11th-12th century).[7] And not only strongly curved cabochon crystals could serve on book covers. The gem now at the center of the Enger Cross in Berlin (Figure 19)[8] was clearly part of a set of evangelist symbols like the ones on the London cover. Its winged man holds a rectangular object, most likely a book, in front of its body, while the figure’s head is turned in a different direction. The twisted pose is typically used to demonstrate the connection between evangelist symbols and Christ, who is placed between them as a Lamb, Majestas, or some other sign. The flat circular crystal in Berlin may well have been part of a four-symbols-and-Christ composition, perhaps incorporated into a book cover similar to the ninth/tenth-century one on the Morienval Gospels (Figure 7).[9]

Fig. 6. Book cover or case, detail. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 528-1893 (photo: author).

Fig. 7. Morienval Gospels cover, wood with bronze, ivory, and horn, 24.5 x 19.3 cm, ninth or tenth century. Noyon, Hôtel de ville (photo: © Inventaire général, ADAGP).

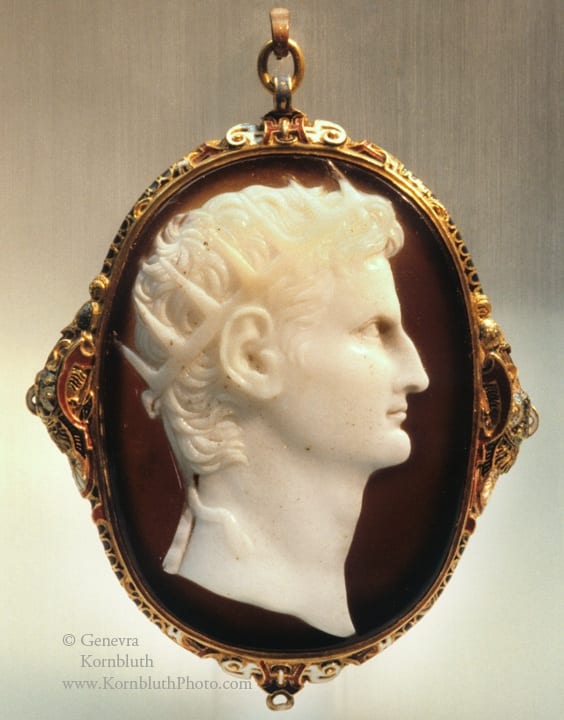

Fig. 8. Augustus, banded agate cameo, 6.69 x 4.94 cm, decade after 14 CE, frame second half of the sixteenth century. Cologne, Römisch-Germanisches Museum, 70.3 (photo: author).

Fig. 9. Eagle, carnelian cameo 2.28 x 2.24 cm, twelfth century. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum CG, 751a (photo: author).

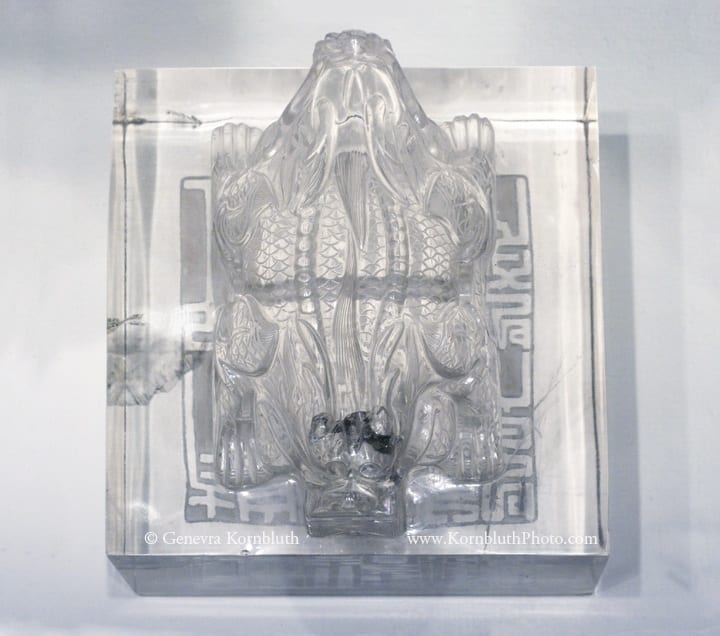

Fig. 10. Chinese rock crystal stamp seal, cameo and intaglio, 10.2 x 14.3 cm, dated 1796. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1944-20-14 (photo: author).

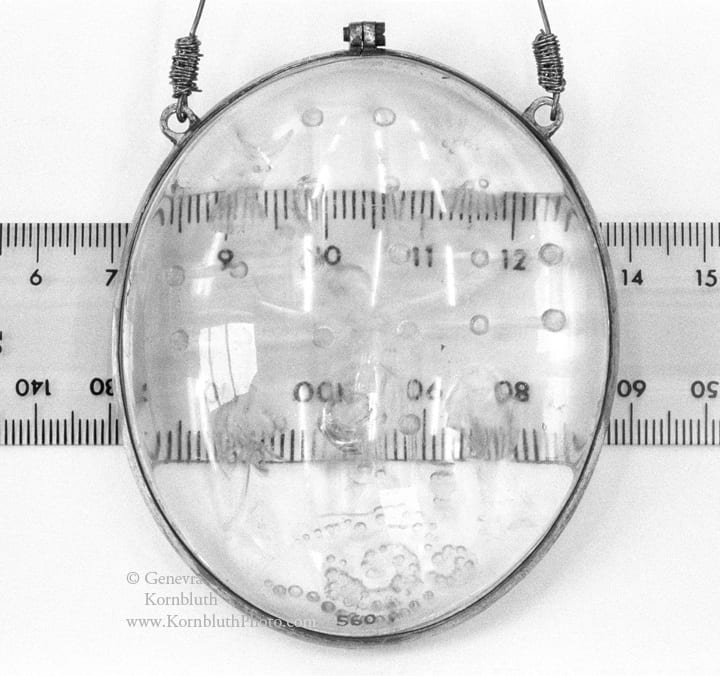

Whether flat or curved, all of the Carolingian engraved crystals were designed to be correctly seen from the reverse, through the body of the stone, taking advantage of their medium’s transparency.[10] They are also affected by the material’s other optical characteristics. Most readers will be familiar with cameos made from naturally layered shell or stone (Figure 8),[11] where an engraver has cut the background plane deeply enough to reach a different color, leaving the figure silhouetted and easily visible. Compositions on monochromatic cameos (Figure 9)[12] are slightly more difficult to see, though light reflecting from their relief surfaces can usually reveal their details. If a cameo is transparent as well as monochromatic, features seen through the stone appear to interact with the reflective front surfaces, sometimes creating visual confusion. On a Chinese seal matrix, for example (Figure 10),[13] the design to be inked and stamped is on the base of the object, but is visible enough to prevent immediate recognition of the double-headed toad that forms its handle. The Carolingian crystals add one more level of potential obscurity. They are intaglios, not cameos, their figures cut below the background plane rather than protruding above it (Figures 11, 12).[14] As on other rock crystal objects, their designs are made visible by the light that reflects off their variously angled and textured surfaces; since those designs do not protrude in relief, however, they usually do not catch such light by accident. Carolingian artists left their engraving matte, helpfully allowing light to reflect differently from figures and their highly polished backgrounds. Nonetheless, the angles between the engraving, the light source, and the viewer must be precisely aligned to make a composition fully visible. Two photographs of the same Carolingian intaglio[15] demonstrate the problem: in Figure 13 the light is carefully positioned to reveal as much of the engraving as possible, while Figure 14 shows the gem as it is displayed in its museum case, lit by sunlight coming through a window. Another Carolingian crystal photographed in available light (Figure 15), this time from rows of overhead neon lights in a museum study room, demonstrates how the engraving can nearly disappear; compare Figure 2, the same object carefully lit. Without modern illumination selectively applied, one sees only part of the engraving at any given moment. Like sunlight, the flickering light from candles and oil lamps allowed only partial glimpses of a composition. A medieval viewer had to work to see all of it.

Figure 15 also demonstrates another optical property of rock crystal: when given a curved surface, the stone becomes a magnifying lens. I have elsewhere argued that magnification was noticed, understood, and intentionally deployed by Carolingian artists.[16] It probably influenced the decision to place a strongly curved polished crystal over the packed earth at the center of the Ardennes Cross (Figure 4), where the stone visually enlarges as well as protects and reveals the relic. The BM Crucifixion crystal (Figure 15) shows the effect of that magnification on an object placed behind the engraved back of the gem. Art historians normally think of the figural surface of an object as the primary one. Depending on angles of light, however, at any given moment the unengraved surface, the engraved composition, or something behind the crystal might be the primary focus.

Fig. 11. Saint Paul, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse, 4.2 x 3.3 cm, mid to late ninth century. Paris, Museum of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 9505-A-19, housed in Paris, Cabinet des Médailles, H3416 (photo: author).

Fig. 12. Saint Paul, rock crystal intaglio, oblique view of engraved reverse, 4.2 x 3.3 cm, mid to late ninth century. Paris, Museum of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 9505-A-19, housed in Paris, Cabinet des Médailles, H3416 (photo: author).

Fig. 13. Crucifixion, rock crystal intaglio, engraved reverse, 6.1 x 5.4 cm including mount, 855-69. Paris, Cabinet des Médailles, 2167ter (photo: author).

Fig. 14. Crucifixion, rock crystal intaglio, engraved reverse, 6.1 x 5.4 cm including mount, 855-69. Paris, Cabinet des Médailles, 2167ter (photo: author).

Fig. 15. Crucifixion, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse with plastic ruler, 8.5 x 6.8 cm including mount, second quarter to mid ninth century. London, British Museum 1867,0705.14 (photo: author).

Fig. 16. Evangelist Symbols with Cross, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse, visible stone, 5.5 x 4.5 cm, c.820-60. Toledo, Ohio, Toledo Museum of Art, 1950.287 (photo: author).

A cabochon crystal with a cross and four evangelist symbols, c.820-860, is now in the Toledo (Ohio) Museum of Art (Figures 16, 17).[17] Probably first set on a cross, it is now prominently displayed on a reliquary base from the early thirteenth century (Figure 18).[18] A cavity for the relic opens immediately behind the crystal, and may connect with the space under an access door in the top of the object. The relic itself is unfortunately lost, so we cannot be sure exactly where it was placed. In the medieval period as now, however, anyone looking at the center of the reliquary’s front side had to deal with at least three levels of visibility. First is the polished, curved surface of the crystal, highly reflective and so insistent on its presence. Only by looking past that surface can one see the engraving on the back of the stone, and that “looking past” presents a challenge. In my photograph, the engraving is carefully lit to let readers see its composition without difficulty. The photograph allows the viewer to be passive. In person, the object requires that a viewer be active (or to use the terminology of this publication, the crystal itself is controlling). The light source must be precisely positioned and repositioned, and the viewer must move her/his head around to see all four of the evangelist symbols. When the relic was still present, it required peering still farther in, past the engraving. The transparent stone allowed it to be seen even though it was enclosed and protected, and magnification must have helped. But even today, seeing any more than the edge of the red interior lining is quite difficult. Viewing the relic required active effort.

As I have noted above, the crystal with the winged man of Matthew (Figure 19), mid to late ninth century, must originally have been part of a group of evangelist symbols depicted on separate gems, perhaps made for a book cover. It is now mounted on a processional cross from the first third of the twelfth century, located in the Berlin Kunstgewerbemuseum (Figure 20).[19] Although central, it is only one of many polished stones and pearls set in gold. Those who saw the cross carried in procession can have had only a general sense of precious metal and stones, flashes of reflected light and color, as it went past. Officiants and sacristans would have had closer and longer views, and it is they who could have given the cross and its crystal the active looking that they require. In this case, the engraving is not the first thing that catches the eye. Once past the shiny surface of the unengraved face, the literate viewer (at least) is struck by the inscription behind the gem: +DE*LIGNO*DNI* (Figure 21). The niello letters are in stark contrast with the ground, quite unlike the engraved figure. But sooner or later the figure does demand attention, a ghostly apparition barely visible in the center of the gem. Only with sharply angled light can details of the figure be seen—and only a digital composite makes both the length of the person standing on a cloud/ground and the full breadth of the extended wing visible at the same time. Once again, the photograph allows a viewer to passively take in the whole composition, but in person the object requires constantly shifting angles of light and view. And then, of course, there is the question of the relic, presumably a fragment of the True Cross. That is actually not visible at all, but hidden in a small cavity behind the inscription.[20] The center of the cross required differentiation between and active looking on three superimposed planes—the polished surface of the stone, the engraved winged man, and the inscription—and intellectual extension of ‘sight’ to a fourth level, the relic inside.

Fig. 17. Evangelist Symbols with Cross, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse from right, visible stone, 5.5 x 4.5 cm, c.820-60. Toledo, Ohio, Toledo Museum of Art, 1950.287 (photo: author).

Fig. 18. Reliquary base, gilt and enameled bronze, copper, silver, rock crystal, 21 x 47 cm, c.1200-1225. Toledo, Ohio, Toledo Museum of Art, 1950.287 (photo: © Toledo Museum of Art).

Fig. 19. Symbol of St. Matthew on the Enger Cross, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse, diameter 3.6 cm, mid to late ninth century. Berlin, Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1888,635. (photo: author).

In fact, the close viewer is encouraged to look around and through the whole cross. The iconography of the back side, four evangelist symbols surrounding the Agnus Dei (Figure 22), echoes the symbol of Matthew on the front, inviting a second look back at the gemmed side. The Lamb itself is presented as a bringer of news like the evangelists, holding up and standing on a scroll. And that Lamb is inscribed in a circle within a square, like the circular crystal on the square obverse crossing. Compositional similarity reinforces the conceptual unity of the cross’s two faces: Christ is present in both the True Cross mentioned on the obverse and the Lamb/Hand of God on the reverse. While physically looking at one side and then the other, the viewer is invited to look intellectually and spiritually through and beyond the cross, perceiving the relic in the center without physical sight, and ultimately moving beyond the material object altogether.

Fig. 20. Enger cross, obverse, gold with gems and pearls on oak core, 22.4 x 18.5 cm, c.1100-1130. Berlin, Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1888,635 (photo: author).

Fig. 21. Enger cross, obverse center. Berlin, Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1888,635 (photo: author).

Fig. 22. Enger cross, reverse. Berlin, Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1888,635 (photo: author).

In some ways, the Carolingian crystal on the Majesté de Sainte Foi (Figures 1a, 23, 24)[21] functions more simply. The Crucifixion intaglio, unfortunately only broadly datable (c.825-950), is set in one of the metalwork bands added to the reliquary in the late tenth century. It is located at the top of the throne back, just below the nape of the figure’s neck. This is one of the strongly curved cabochons, so its outward-facing unengraved side is both highly reflective and quite noticeable. One must look past that, carefully setting up the light and angle of view, to see the engraving. But this crystal covers neither inscription nor relic. Only a black textile is visible in the very narrow space behind the stone, and behind that is flat metal.

Fig. 23. Majesté de Sainte Foi, from back right. Abbaye de Conques, Treasury (photo: © CNMHS).

Fig. 24. Crucifixion, rock crystal intaglio, unengraved obverse, 4.9 x 3.9 cm. On Majesté de Sainte Foi, second quarter of the ninth to mid tenth century. Abbaye de Conques, Treasury (photo: author).

Fig. 25. Knights carrying a reliquary of St. Martin, altar frontal from Saint Martin de Liége, silk embroidery with gold and silver, second quarter of the fourteenth century. Brussels, Royal Museums of Art and History, Cinquantenaire Museum (photo: author).

But behind that in turn is the bulk of the figural reliquary, with Foi’s skull and vertebrae located inside at the stomach level. Like the Enger cross, this work concealed its relic until a Gothic viewing window was installed in front. But unlike both objects discussed above, this “Majesté” has the form of a human body. While any reliquary may take on the personality of the saint(s) inside, one whose shape was modeled after our own implicitly suggests interaction as with an ordinary living person.[22] Viewers tend to dwell on the figure’s head (and eyes). Thus Bernard of Angers described the figural reliquary of St. Gerald:

It was an image made with such precision to the face of the human form that it seemed to see with its attentive, observant gaze the great many peasants seeing it and to gently grant with its reflecting eye the prayers of those praying before it.[23]

Many people probably wanted to see Ste. Foi’s head. But in order to see the reliquary at all—let alone its head—most of them had to look up. In about 1013, Foi was displayed in a special area or room at her abbey in Conques.[24]

When [Bernard and his companion] had entered the monastery, fate brought it about, quite by chance, that the separate place where the revered image is preserved had been opened up. We stood nearby, but because of the multitude of people on the ground at her feet we were in such a constricted space that we were not even able to move forward.[25]

The people were “on the ground at her feet”, and Bernard implies that he could see her despite the crowd, so she was probably raised up on a platform or pedestal, as today.[26] She was certainly held high when carried in procession. One of her miracles that Bernard recorded was the punishment of a greedy man who, seeing Foi at such an event, thought to himself,

Oh, if only that image would slip from the shoulders of the bearers and fall to the ground! No one would gather up a greater portion of the shattered stone and broken gold than I.[27]

The reliquary’s head must have been high above its base at shoulder height. Although Bernard does not describe just how the Majesté was carried in other processions,[28] by the time she took her current form it was normal for reliquaries to be placed on a platform that rested on two long poles extending in the front and back. Those poles in turn rested on the shoulders of the bearers.[29] A fourteenth-century embroidery, for example, shows knights carrying a reliquary of St. Martin of Tours in this way, first to take it to battle and then again to triumphantly return it home (fig. 25).

Viewers of the Majesté probably looked up most of the time. When the reliquary was out on procession, they looked up at a very sharp angle. And from behind, a glance toward the figure’s head first intersects the Carolingian Crucifixion crystal. At the moment of that regard, the spiritual truth about the saint’s glory and power—its derivation from the power and love of God manifested in the Crucifixion—becomes almost literal. The Crucifixion that is so often represented on reliquaries is here present in transparent form. The viewer looks at the saint through the lens of the Crucifixion. For those who, unlike the modern technician with his screwdriver, are willing to accept direction from a work of medieval art, the optics of this and the other crystals are very active indeed.

References

| ↑1 | I.13; Pamela Sheingorn, trans. and intro., The Book of Sainte Foy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1995), 77. https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812200522 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Genevra Kornbluth, Engraved Gems of the Carolingian Empire (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 1995) passim. |

| ↑3 | British Museum, 1867,0705.14. Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, no. 14. |

| ↑4 | Nürnberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, FG 763. Most recently Cynthia Hahn, Strange Beauty: Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400-circa 1204 (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2012), 92-96. |

| ↑5 | Michel Félibien, Histoire de l’Abbaye Royale de Saint-Denys en France (Paris 1706), plate IV; Blaise de Montesquiou-Fezensac and Danielle Gaborit-Chopin, Le Trésor de Saint-Denis (Paris, 1973-1977), vol. 3, 32-33 and plate 16A. |

| ↑6 | Victoria and Albert Museum, 528-1893. Frauke Steenbock, Der kirchliche Prachteinband im frühen Mittelalter, von den Anfängen bis zum Beginn der Gotik (Berlin, Deutscher Verlag für Kunstwissenschaft [1965]), no. 27. The later painting of Mary seen under the central crystal by Steenbock and still referenced in the V&A online catalogue is no longer present. |

| ↑7 | Walters Art Museum, W.8. Martina Bagnoli et al., ed., Treasures of Heaven: Saints, Relics, and Devotion in Medieval Europe (Cleveland, Baltimore, London: Cleveland Museum of Art, Walters Art Museum, British Museum, 2010), no. 61, 121-2; Steenbock, Kirchliche Prachteinband, no. 87. The setting of the crystal is disturbed, but if the stone is new it must replace another transparent one. |

| ↑8 | Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin, 1888,635. Peter Lasko, “The Enger Cross,” in Helmarshausen und das Evangeliar Heinrichs des Löwen, ed. Martin Gosebruch and Frank Steigerwald (Göttingen: Verlag Erich Goltze, 1992), 79-108; idem, “Roger of Helmarshausen, Author and Craftsman: Life, Sources of Style, and Iconography,” in Objects, Images, and the Word: Art in the Service of the Liturgy, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Princeton University, 2003), 180-201. Gem: Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, no. 11. |

| ↑9 | Noyon, Hôtel de ville. Steenbock, Kirchliche Prachteinband, no. 37. |

| ↑10 | The reversed intaglio engraving of the three crystal seal matrices (Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, nos. 5, 8, and 9) was required for the objects to physically function. While their metalwork settings may have allowed their designs to be seen through the stone, the form of those mounts is unknown. |

| ↑11 | Erika Zwierlein-Diehl, “Der Divus-Augustus-Kameo in Köln,” Kölner Jahrbuch für Vor- und Frühgeschichte 17 (1980): 12-53. |

| ↑12 | Martin Henig, Classical Gems: Ancient and Modern Intaglios and Cameos in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), no. 751a, 363. |

| ↑13 | Jean Lee et al., “The Crozier Collection part 1: Rock Crystals,” Philadelphia Museum Bulletin 40/203 (1944), no. 14, p. 9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3794818 |

| ↑14 | Museum of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, 9505-A-19, housed in the Cabinet des Médailles, H3416. Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, no. 10. |

| ↑15 | Cabinet des Médailles, 2167ter, 855-69. Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, no. 3. |

| ↑16 | Genevra Kornbluth, “Carolingian engraved gems: ‘golden Rome is reborn’?” in Engraved Gems: Survivals and Revivals (Studies in the history of art, 54), ed. Clifford Malcolm Brown (Washington, D.C., 1997), 45-61. |

| ↑17 | Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, no. 17. |

| ↑18 | Number 1950.287: Richard H. Putney, Medieval Art, Medieval People: The Cloister Gallery of the Toledo Museum of Art (Toledo: The Toledo Museum of Art, 2002), 54-55. |

| ↑19 | Lasko argues that the crystal has “not entirely relevant iconography as a cover for a fragment of the True Cross”: “Enger Cross,” 85. |

| ↑20 | Gia Toussaint, “Die Kreuzreliquie und die Konstruktion von Heiligkeit,” in Zwischen Wort und Bild: Wahrnehmungen und Deutungen im Mittelalter, ed. Hartmut Bleumer, Hans-Werner Goetz, Steffen Patzold, and Bruno Reudenbach (Cologne: Böhlau, 2010), 73. https://doi.org/10.7788/boehlau.9783412213206.33 |

| ↑21 | Beate Fricke, Ecce Fides: Die Statue von Conques, Götzendienst und Bildkultur im Westen (München: Fink, 2007), which I have not yet been able to consult directly; Danielle Gaborit-Chopin, “Majesté de Sainte Foy,” no. 1 in Danielle Gaborit-Chopin et al., Le Trésor de Conques: Exposition du 2 Novembre 2001 au 11 Mars 2002, Musée du Louvre (Paris: Editions du Patrimoine, 2001), 18-27; Jean Taralon and Dominique Taralon-Carlini, “La Majesté d’or de Sainte Foy de Conques,” Bulletin Monumental 155 (1997): 11-73. Crystal: Kornbluth, Engraved Gems, no. 16. https://doi.org/10.3406/bulmo.1997.872 |

| ↑22 | Barbara Boehm, “Reliquary Busts: ‘A Certain Aristocratic Eminence’,” in Set in Stone: The Face in Medieval Sculpture, ed. Charles T. Little (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2006), 168-80; Hahn, Strange Beauty, 117-33. |

| ↑23 | I.13: Sheingorn, Book of Sainte Foy, 77. |

| ↑24 | Claire Delmas, “Les différents emplacements du trésor dans l’abbatiale,” Bulletin Monumental 161 (2003): 104-05. |

| ↑25 | I.13: Sheingorn, Book of Sainte Foy, 78. |

| ↑26 | Display of reliquaries: Hahn, Strange Beauty, 199-208, with the note that “in general, reverence took the form of kissing the altar or grave, or the floor in front of it, and kneeling or prostrating oneself before the altar or grave” (200). |

| ↑27 | I.14: Sheingorn, Book of Sainte Foy, 79. |

| ↑28 | Other processions: II.4: Sheingorn, Book of Sainte Foy, 120-24. |

| ↑29 | Anton Legner, “Zur Präsenz der großen Reliquienshreine in der Ausstellung Rhein und Maas,” in Rhein und Maas: Kunst und Kultur 800-1400, ed. A. Legner (Cologne: Schnütgen Museum, 1973), vol. 2, 65-94. |