Alexa Sand • Utah State University

Recommended citation: Alexa Sand, “Materia Meditandi: Haptic Perception and Some Parisian Ivories of the Virgin and Child, ca. 1300,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 4 (2014). https://doi.org/10.61302/FBJV9093.

Among the many exquisite ivories of the Virgin and Child in the collection of the V&A, the Rattier Virgin, a Parisian work of about 1270, stands out for its delicacy and its fine state of preservation (Figure 1). Viewed in its museum setting, it is an icon of Gothic elegance and refinement, its miniature scale, sumptuous materials, and intimacy of gesture all emblematic of the aesthetic sensibility characterized by Umberto Eco as “vast symbolical ideations [alongside] some pleasant little figures which reveal a freshness of feeling for nature and a close attentiveness to objects.”[1] The Christ child’s lively movements seem drawn from observation of how real toddlers behave, his face bears a sweetly inquisitive expression commensurate with his playful engagement with the bird he holds, and his mother gazes at him with the affectionate absorption that very young children do inspire in their adult caregivers. What makes the image poignant rather than saccharine is that these same, deceptively naturalistic visual traits also carry a heavy theological load. The strong chiasmus expressed in the child’s pose inevitably points toward his fate on the cross; the bird, perhaps a goldfinch, is associated with death, and Mary’s tender caress of the pudgy foot calls to mind the nails that will wound that flesh in the course of the Passion.[2]

Fig. 1. Seated Virgin and Child, “Rattier Virgin,” ivory, 201 x 92 x 73 mm. London, Victoria and Albert Museum, 200.1867 (photo: © Victoria and Albert Museum, London).

Despite the initial impression of emotive spontaneity given by the interaction between mother and child here, each of these motifs belongs to a representational vocabulary that draws on a deep iconographic well.[3]

As Jacqueline Jung has recently discussed in an essay on the centrality of the tactile properties of sculpture to the medieval religious imagination, small sculptural works such as this one belong to a set of practices and performances that weave tactile and visual perception into the fabric of devotional experience.[4] While Jung explores a range of sculptural media and settings, I think that the particular case of ivory deserves close scrutiny for a couple of reasons. First the sensuous nature of the material—smooth, but like velvet or satin characterized by subtle variations in the surface and quickly responsive to the warmth of the hand. Anthony Cutler points out that medieval audiences for ivory objects were also acutely aware of another tactile property of ivory, weight, which would have enhanced pleasure as it conveyed a sense of luxury and expense.[5] Cost is emphasized in the Rattier Virgin and many other similar works by the restrained use of polychromy: gilding, ultramarine blue, and red, all three prestigious and valuable coloring agents themselves.[6] Then there is the semiotic resonance of ivory: like the similarly velvety vellum pages of devotional books, it is a once-living material purified of its bestial associations by human artistic intervention and by the sacred purpose and iconography toward which it is devoted. Liturgical and homiletic sources stress the parallel between ivory’s whiteness and translucence and the Virgin’s luminous purity, as well as its scriptural association with her womb and with the incarnate flesh of Christ.[7] All this, combined with the material’s rarity and its putative medicinal virtues make it the ideal vehicle for representing the Virgin and her Child.[8]

In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the increased availability of elephant ivory along with a ravenous taste for small-scale ivory statuettes depicting the Virgin and Child resulted in the production of large numbers of these objects, hundreds of which survive.[9] Paris was the most important, though by no means the only, center of production, and it is on a small group of statuettes from Paris that I focus here. All depict the seated Virgin with the child standing in her lap and engaged in a variety of gestures that emphasize touch. Originally classified as stylistically related and linked to the Parisian context by Raymond Koechlin, the group has been further studied by Danielle Gaborit-Chopin, Charles Little, François Bucher and Paul Williamson.[10] The group includes several well-known works, such as the Rattier Virgin, the magnificent example from the treasury of San Francesco d’Assisi, and the large and elegant Virgin and Child from the Collégiale Villeneuve-les-Avignon. Also associated with these works are less widely publicized examples, including the small (9 cm high) Virgin and Child in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, and the comparatively monumental (25.4 cm high) Virgo lactans in New Haven (Yale University Art Gallery, 1949.100). All of them not only invite touch—or at least the contemplation of touch—through their medium, scale, and form, but also actively engage in the visual representation of touch in a reflexive, devotional mode. I hope to situate the statuettes in terms of what Bissera Pentcheva has called (in reference to Middle Byzantine icons), a “tactile and sensorial visuality,”[11] in order to come at a complex account of how these material things signified and to engage with the theme of objects as active agents, and not merely as passive elements in devotional practice.

When I speak of the tactile properties of these works, I do not necessarily propose that they were intensively stroked, fondled, or otherwise handled by their owners and admirers. Indeed, in some cases, the poor condition of an object, its discoloration from repeated contact with the oils, sweat, and dirt of human skin speaks of this kind of hard use.[12] A recently acquired seated Virgin and Child of about 1300 in the Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario shows significant signs of wear from handling, particularly on the proper right of the Virgin’s face which has been restored, and in the loss of almost all the original polychromy, but this is unusual in surviving objects and it cannot be absolutely determined to be damage by medieval, rather than later owners.[13] Elephant ivory was very expensive in Europe of the Middle Ages, and ivory sculptures that have come down to us in the almost pristine condition of the Rattier Virgin must have been carefully preserved and cautiously handled. The tactile nature of these works has less to do with being handled than with being haptic—that is oriented toward the sense of touch in their materiality and their conception as representational objects.[14] Their size, their material, and their devotional setting engender a close-in viewing experience in which “the eye has a haptic, nonoptical function,” and the mind “touches” the object.[15] Without entirely embracing the opposition of “haptic” and “optic” modes as stable and predetermined, we can understand the haptic qualities and the attentiveness to tactility in the Gothic ivory Virgins as in part a function of their participation in the sphere of devotion.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s notion of the “intersensory thing,” an internalized object of consciousness produced by and consisting of the combined “invasions” of outward phenomena into the body by way of the cross-referential senses allows us to think about how an art object might be haptic in nature even when it is not being handled. Touch, of all the senses the only one that is “enacted throughout the body” is always present under the surface of visual perception.[16] On a hot day, the sight of a fountain or a lake can cool us, and our vision often serves to inform or to warn us of other tactile properties such as rough, hot, soft, or sharp—this is not the neurophysical condition of synesthesia, in which sense perceptions are literally cross-referenced in the process of reception, but instead a normal, indeed necessary associative function of the mind. The “intersensory thing” is produced by the sensing body and its sense-memory; as Oliver Sacks has observed, “Most of us have no sense of the immensity of the construction, for we perform it seamlessly, unconsciously, thousands of times each day, at a glance.”[17] The work of art, both in its making and in its reception asks to be understood specifically in terms of how it acts upon, shapes, shifts, or distorts the perceptual phenomena of seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting, smelling, or more likely some combination thereof. The Gothic ivory Virgins that concern me here specifically call upon the relationship between sight and touch, though they also in different instances and to varying degrees summon taste, smell, and sound to the perceptual table.

Fig. 2. Seated Virgin and Child (Virgo lactans), ivory, 254 x 95 x 57 mm. New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, 1949.100 (photo: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University).

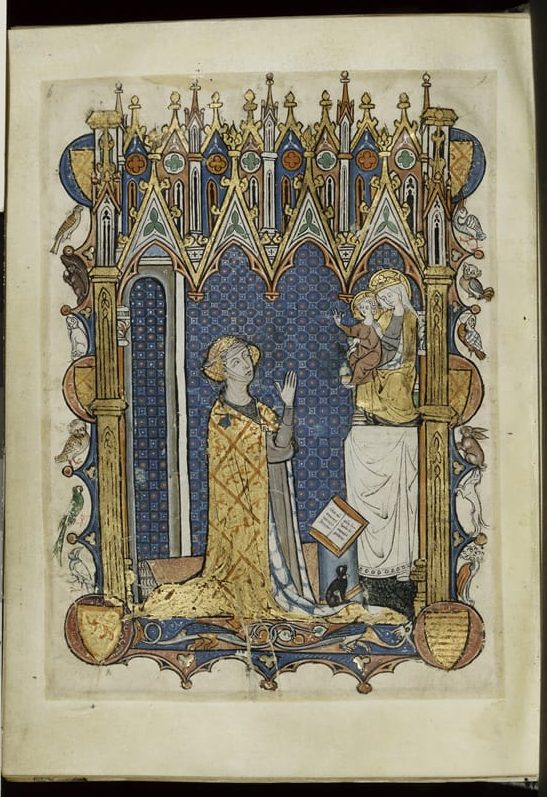

Fig. 3. Book owner kneeling in prayer, Matins of the Hours of the Virgin, Psalter-Hours “of Yolande of Soissons,” c.1290, Amiens. The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. MS M.729, fol. 232v. Purchased in 1927 (photo: © The Pierpont Morgan Library).

The large statuette in New Haven, with its suckling Christ (Figure 2), taps into the multisensory phenomenon of lactation and nursing. To a certain degree, the same can be said of any representation of the Virgo lactans, and may partially account for the popularity of the motif in both Byzantine and later medieval Western European art. In the particular case of this object, however, the harmony between the theme of lactation and the creamy white, smooth surface of the ivory, underscored by the organic unity of the two bodies carved from one tusk and knit together by the fluid, rippling swathes of their drapery and the direct statement of the bodily continuity between mother and Son as he latches on to her gently proffered breast not only make visible a fundamental theological truth, but also evoke the physical and material dimensions of nursing. It is not necessary to be or to have been a lactating mother for the statuette to instigate an internalized perceptual episode; the point is precisely that it can visually provoke the process of intersensory association in anybody who approaches it with the expectation that it will trigger some kind of internally transformational event, which is to say the viewer who recognizes its manipulated and manipulative nature as a consciously fashioned representational object—a work of “art.”

The Virgo lactans motif combined with the material properties and symbolic dimensions of ivory may amount to overkill; it is guaranteed to deliver a perceptual payload along with a substantial dose of theology, but without much finesse. Add to this the unusually large size (and therefore large price) of the New Haven Virgin, and the whole thing begins to seem a bit ostentatious. Other objects in this group balance more delicately between giving the appearance of a shimmering vision momentarily condensed from the spiritual ether and a substantial, material image crafted by human hands and therefore evocative of the maker’s physical touch and the owner’s worldly wealth. This oscillation between apparition and object was of interest to medieval artists and viewers as well. In the devotional picture of the book owner that appears at the beginning of the Matins of the Virgin in the Psalter-Hours of Yolande of Soissons (Figure 3), the painter skillfully leaves open the question of whether the lady at the center of the picture with her prayer book and her little dog is merely praying hopefully in front of a static sculptural representation of the Virgin and Child, or whether instead she has moved beyond the routine of devotion into direct interaction with an animate apparition of the holy pair. While subtle differences in the tonality of flesh between the kneeling woman and the Virgin and Child as well as their smaller scale and their placement on an altar all suggest that we are seeing a large but not life-size sculptural group, the gestures made by both figures towards the praying book owner stand in sharp contrast to the mutual absorption of the mother and Son in contemporary ivory statuettes. The engagement of the Virgin and Child with the book owner mirrors their engagement with the three Magi in the Adoration miniature that appears a few pages on in the same manuscript and that recycles a visual commonplace already centuries old by the late 1200s.

Fig. 4. Seated Virgin and Child, ivory, 450 x 160 mm without wooden base (added in 19th century). Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, Musée Pierre-de-Luxembourg, Inv. PL 86. 3. 1 (photo: © Musée Pierre de Luxembourg, Villeneuve-lès-Avignon).

Though the group on the altar appears to be a polychrome statuette in the current style, it enacts an exchange more typical of its forerunners, the Throne of Wisdom Virgins of the eleventh, twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, which were cast as players in liturgical dramas reenacting the Epiphany narrative, as we understand thanks to Ilene Forsythe.[18] Those same statues were also far more likely than their younger ivory cousins to be animate in miracle stories and local traditions. Reflecting the physical nature of these wood sculptures, in which the Christ figure was often carved independently of the Virgin and could be removed and replaced for purposes of costuming or storytelling, one legend relates how a woman whose child has vanished appropriates the infant from a local Madonna sculpture (described by the narrator as “old and badly made”) and hides it in her cupboard, swaddled like a real infant, until such time as the Virgin restores her own child to her alive. The ploy works, and both mothers express their satisfaction with the outcome.[19] Such a tale would not ring true were an ivory statuette involved—the very form they take, curving with the arc of the tusk, serves to remind the viewer of the unitary nature of the two figures. This unity is not incidental; according to the regulations of the Livre des Mètiers of the Prévôt of Paris, Etienne Boileau (about 1268), no carved figure in wood or ivory should be cut from more than one piece (except a crucifix, in which the arms could be cut from a separate piece of material for obvious reasons), as such shoddy work was unworthy of the profession.[20]

The tale of the purloined Christ child reminds us that religious images were not museum pieces, and were frequently handled or manipulated in ways that suggested they were living members of a community. Kissing, fondling, even removing of pieces of an image were accepted practices that acknowledged the efficacious agency of sacred representations. Though such manipulations could be destructive (the Volto Santo in Lucca was so degraded by supplicants’ depredations that it had to be entirely refashioned in the twelfth or early thirteenth century) they did not necessarily involve rough handling; the woman who steals the Virgin’s Child cares for the sculpted infant by wrapping it in rich cloths and keeping it safely closed away in a cupboard. However, ivory objects because of their cost, their sensitivity to environmental factors, and their delicacy certainly belonged to a reserved class of religious images that needed extra care. William Wixom points out that while today most Gothic ivory Virgins appear as stand-alone works, in their original setting they were often the centerpiece of a tabernacle crafted of ivory or more often of gilt or silvered wood, sometimes complete with shutters to enclose and protect the statuette.[21] The very sensitivity of ivory objects to handling makes the centrality of touch to their representational strategy all the more compelling. It may even be that the haptic quality of these statuettes in some way responded to their decreased receptivity to intensive handling relative to earlier sculptural groups depicting the Virgin and Child.

In the Rattier Virgin, the sense of touch is brought to the fore through a series of depicted gestures. Most affecting of these is that of Mary fondling the foot of the Christ child. Beneath its seemingly observational naturalism, this motif reflects a devotional and iconographical topos immensely popular in this period. The iconography of the Magi often features the reverential touching or kissing of the infant’s feet, and borrowing from the visual repertoire of Crusader and Orthodox icons from Cyprus central Italian painters of the thirteenth century adopted the motif of the Virgin delicately fondling the child’s forefoot. Christ’s feet are also the focus of Mary Magdalene’s attention in the house of Lazarus, and again, in Byzantine-derived iconography of the Lamentation. Already in the twelfth century Bernard of Clairvaux and Aelred of Rievaulx exhorted penitent sinners to address themselves to the feet of Christ, Bernard proposing the feet as the proper focus of the first, “purgative” stage of devotion, and Aelred ecstatically urging the penitent to emulate the Magdalene; “Kiss, kiss, kiss, blessed sinner, kiss those dearest, sweetest, most beautiful feet… kiss them, embrace them, hold them fast.”[22] Writing in the early fourteenth century, the author of the pseudo-Bonaventuran Meditations on the Life of Christ instructs the reader to “kiss the feet of the child Jesus lying in the manger,”[23] and as Christine Klapisch-Zuber has noted, this was not merely an imaginative practice, but a very public performance communally enacted in monastic and secular communities in early modern Italy.[24] As Jung has pointed out, German mystics of the fourteenth century frequently described the experience of fondling the tiny foot of a sculpted Christ child only to feel it come alive in the hand.[25]

The imagery of kissing melds touch and taste, and seems to raise the devotional temperature at least by a degree. Recent scholarship has tended to stress the bodily and erotic dimensions of the kiss, and these are undeniably present in the rhetoric of medieval spirituality. However, against such literal reading of the performative sexuality of late-medieval devotion it is important to keep in mind the figurative turn of the medieval imagination. To utter the words of prayer could constitute spiritual kissing, just as to gaze upon an image of the Crucifixion could plunge the viewer into a wrenching experience of compassio, as it did for Julian of Norwich as she lay upon her sickbed thinking herself near death. When the English Benedictine chronicler and monk Matthew Paris depicts himself almost prostrate at the feet of the enthroned Virgin and Child in the colophon page of his Historia Angolorum (1250-1259) he shows the infant kissing his mother’s cheek. The prayer Matthew offers, written out in front of his hands as if it were a physical votive, is O felicia oscula, “Oh happy kiss, with milky lips impressed.” Matthew, in his subservient posture, is in no position either socially or practically, to literally kiss the holy pair, but he participates in the tender, milk-scented embrace they share through his prayerful offering.

Kissing, touching, and holding the infant’s foot all correspond to both ritualized gestures of submission and supplication and to a more spontaneous set of behaviors characteristic of adult responses to infants on the level of bodily sensation, thus reinforcing the bond between the symbolic and the sensory orders of experience. Furthermore, the gesture of holding the foot calls up a host of Christological meanings embedded in the iconographic formula. Rebecca Corrie’s work on Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del Bordonehas demonstrated that the motif of the squirmingly active Christ child, his foot in his mother’s hand, derives from the Byzantine iconographic type identified by Victor Lasareff as “the Virgin with the playing child,” and brings with it a mordant message; the playful infant adumbrates the inert corpse of the Crucified Christ.[26] The focus on Christ’s feet in contemporary depictions of the Lamentation would have helped to make this prolepsis present and perceptible.

The long, slender fingers of the Rattier Virgin’s hand gently caress the forefoot just behind the toes rather than grasping or holding the foot firmly. The quality of this touch is similar to that of the Child manipulating the bird—he presses its wings between the tips of his fingers and his pudgy thumbs without indenting the soft feathers. Likewise, the Virgin’s supporting hand on the child’s lifted thigh seems scarcely to skim the surface. All this careful handling draws attention to the material delicacy of the image, emphasizing the translucency and purity of the polished, lightly gilded and tinted ivory surface. If the owner of such an image, alerted to the centrality of touch by these visual cues, was tempted to pick it up and caress it, perhaps at times he or she did, but perhaps not—the haptic sensibility of the image itself may have sufficed. Yet one person at least must have had intimate tactile knowledge of the object; the artist who carved the image held it and handled it. It is probably impossible to determine to what extent the material itself suggested a visual approach that emphasized touch, and to what extent the physical experience of handling ivory led to certain representational decisions, but the ymagier working in ivory cannot have been entirely immune to the particularities of the medium.[27]

The poignant sensibility of the Byzantine-derived motif of the Virgin with her playful child appealed to ivory carvers and particularly to the artists associated with the high-quality productions of the first third of the fourteenth century in Paris. Of the group of seated ivory virgins associated with the Rattier example, several others also use the visual depiction of touch to underscore the embodied, touchable nature of the incarnate Christ. In the statuette now in the treasury of the Collégiale Villeneuve-lès-Avignon (Figure 4) the infant is less boisterous, and the Virgin’s free hand is missing, but at the center of things we still find the visual attention to touch. The child’s small fingers have found the gilded cord that should attach the front neck edges of the Virgin’s cloak, but that has come loose, or has been unfastened by the child. Again, he toys with it delicately, neither pulling it taut nor entirely closing his hand about it. The nature of the ivory tusk from which the statuette is carved demands that the Virgin pull back slightly, as if to get a better look at her son’s face, while his body curves in towards her shoulders, drawn magnetically by his fascination with the cord. The push and pull of these movements focuses around that gesture of tactile exploration, and invites the beholder’s touch whether physical, or more likely, notional; either way, it is a Christomimetic touch.

Even more balletic is the large statuette that has been in the treasury of the basilica of Saint Francis in Assisi since at least 1370 (Figure 5). Here, the natural curve of the tusk, instead of being oriented toward the back of the work as in the Villeneuve-lès-Avignon example, moves out to the side, resulting in a somewhat thin profile to the piece that adds to its fragility and suggests that it was designed primarily to be viewed from the front, probably in a tabernacle setting that would have disguised its shallow volume. The deliberate and unusual choice of orienting of the tusk to the side allows the child standing on his mother’s knee to sway away from her, flourishing his long cloak with his outward hand. His other hand rests, as if for balance, on her chest, just above her right breast, only the tips of the fingers lightly pressing into the cloth. With a similarly dainty gesture, the Virgin holds the stem of a flower (its bud has broken off), between the tips of her thumb and forefinger, the other fingers extended stiffly in contrast to the supple, undulating contours of the rest of the piece. The child’s dual gesture, reaching out from his mother to spread his cloak, and reaching back toward her to touch her breast, seems to reference popular imagery of Misericordia, underscoring the bodily identification between Mary and her Son, since it is more usually the Virgin who figures Mercy. The child’s gentle caress of her breast takes this connection between her body and his in multiple sensory and semiotic directions, conjuring the salvific notion of milk as Mercy, and, like Matthew Paris’ self portrait, the warmth and innocent intimacy of the physical relationship between the mother and the child. The “intersensory object” informed by such an image not only engages touch and sight, but smell and taste as well—the sweetness of milk, the fragrance of the rose once held in the Virgin’s stiff fingers.

Fig. 5. Seated Virgin and Child, ivory, height without base 200 cm; 250 x 152 x 60 mm with base. Assisi, Museo del Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco, Inv. 70 (photo: ©Museo del Tesoro della Basilica di San Francesco).

Fig. 6. Seated Virgin and Child, ivory, 182 x 90 x 90 mm. Barcelona, Museo Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, MNAC/MAC 5223 (photo: ©Museo Nacional d’Art de Catalunya).

Fig. 7. Panel, perhaps from a crozier, ivory, 101 x 75 x 11 mm. London, Courtauld Gallery, O.1966.GP6 (photo: ©The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London).

The little ivory virgin in the Museu Nacional d’Arte de Catalunya in Barcelona (Figure 6) shares the delicacy and sweetness of the Rattier example, and like the Assisi Virgin invokes the theme of lactation without baldly stating it in the manner of the New Haven Virgin. Barefoot and dressed in a long tunic, the infant stands on his mother’s lap, though his weight scarcely registers, his leading foot skimming over her knee. He places the open palm of the hand closest to her on her breast, a gesture that refers to both the virgo lactans theme and to the repertoire of images that call attention to the side wound high on Christ’s right breast. A contemporary ivory plaque of either French or Italian origin depicting both a similar seated Virgin and Child and a resurrected Christ displaying the wound spells the breast-wound correlation out more directly (Figure 7). Once more, the child’s depicted touch carries with it a freight of devotional signification even as it resonates with bodily experience and the observable tendency of very young children to explore their surroundings with their hands. The rose held daintily in the Virgin’s fingertips just in front of the child’s hand on her breast underscores the importance of his inquisitive gesture to the piece; both touch and flower allude to the side wound, giving a dark and violent undercurrent to the restrained sweetness of the statuette and reminding us of the connection drawn by medieval medicine and Christology alike between milk and blood.[28])

The ivory carvers responsible for the small family of objects I have surveyed here operated within the conventional iconographic space of the period and the subject. Within the boundaries imposed by habit, convention, law, and the very physical properties of the ivory itself, the makers of these objects capitalized on their material nature to engage their viewers in a perceptual dance that brings together the senses, particularly those of touch and vision, and hinges on their continuity and synergy within the devotional mindset. Gavin Langmuir’s definition of religiosity, “Something stabler and more accessible to the outside world than the totality of all non-rational processes, yet something central in the consciousness of the individual, not so much the process as its more enduring results in the consciousness” is useful; the idea that interaction with images has the power not only to inspire but actually to alter the interior self was critical to medieval theories of the religious image.[29] What the group of Gothic ivory Virgins I have featured in this essay share beyond a common point of origin is a calculated coordination of visual prompts that beguile the sense of touch and instate it at the center of the practice of devotional seeing. To touch such an object, even if such touch-perception is enacted entirely internally and imaginatively, is to mimic both the gestures of the figures and the probing, seeking gaze that searches for a true vision, a genuine, sensible encounter with the holy.

References

| ↑1 | Umberto Eco, Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, trans. Hugh Bredin (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1986), 64. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | On the iconographic significance of the bird, see Donat de Chapeaurouge, Einführung in die Geschichte der christlichen Symbole(Darmstadt : Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1984) 66-68. On the motif of Christ’s bare foot, see Michael Grandmontagne, Claus Sluter und die Lesbarkeit mittelalterlicher Skulptur: Das Portal der Kartause von Champmol (Worms: Werneresche Verlagsgesellschaft, 2005), 382-410. |

| ↑3 | Grandmontagne makes a similar point about some fourteenth-century standing statues of the Virgin and Child he studies in relation to the trumeau figure at the Chartreuse de Champmol; he investigates the gesture of touching or presenting the foot noticing the fine tension between naturalism and symbolism at play: “Das Gleichgewicht, das zwischen lebendiger, vitaler Gebärde einerseits und zeichenhaft zu verstehender Geste andererseits besteht, ist zungunsten einer ‘Denkwürdigkeit’ aufgehoben worden.” Claus Sluter und die Lesbarkeit mittelalterlicher Skulptur, 370. See also page 374-375. |

| ↑4 | Jacqueline Jung, “The Tactile and the Visionary: Notes on the Place of Sculpture in the Medieval Religious Imagination,” in Looking Beyond: Visions, Dreams and Insights in Medieval Art and History, ed. Colum Hourihane (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, 2010), 203-240. |

| ↑5 | Anthony Cutler, The Hand of the Master: Craftsmanship, Ivory, and Society in Byzantium (9th-11th Centuries), (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994), 29. However, the cost of elephant ivory dropped significantly in the late thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in northwestern Europe as new routes of exchange with Africa were developed to serve the growing textile industry, and the availability of ivory increased dramatically; see Sarah Guérin, “Avorio d’ ogni ragione: the supply of elephant ivory to northern Europe in the Gothic era,” Journal of Medieval History, 36 (2010): 156-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2010.03.003 |

| ↑6 | On polychrome ivory, see Danielle Gaborit-Chopin, “The Polychrome Decoration of Gothic Ivories,” Images in Ivory. Precious Objects of the Gothic Age, ed. Peter Barnet (Detroit and Baltimore: The Detroit Institute of Arts, and The Walters Art Gallery, 1997), 46-61. |

| ↑7 | In medieval sermons, liturgy, and treatises, the small but important role that ivory plays in the imagery of the Song of Songs (5.14 and 7.4) associates the material with the bodies of both Sponsus (5.14: “His belly as of ivory, set with sapphires”) and Sponsa(7.4, “Thy neck as a tower of ivory.”), and thus with the bodies of Christ and Mary. For example, the epithet “Tower of Ivory” for Mary belongs to the post-Tridentine tradition of the litany, but it is already present, in pseudo-Adam of St.-Victor’s sequence for the dedication of church, “Clara chorus dulce pangat voce nunc alleluia,” of around 1100, where Song 7 is sampled and rearranged as Christ’s address to his mother. For text, see The Liturgical Poetry of Adam of St. Victor, ed. and trans. Digby S. Wrangham (London: K. Paul, Trench 1881), 150-151. For the rejection of the traditional attribution to Adam, see Léon Gauthier, Oeuvres poétiques d’Adam de Saint-Victor: texte critique (Paris: Picard, 1894), 246. For an excellent, brief summary of the “elaborate and protracted metaphors and allegories” of ivory in late medieval Mariolatry, see William H. Monroe, “A French Gothic Ivory of the Virgin and Child,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 9 (1978): 6-29, see pages 24-25. More recently, Sarah Guérin has pointed out the explicit linkage of the ivory of Solomon’s throne to the bodies of Mary and Christ in the Bibles Moralisées: “Duplicitous Forms,” West 86th 18 (2011): 196-207, see page 204. |

| ↑8 | On elephant ivory in the medieval materia medica, see Sophie Page, Magic in Medieval Manuscripts (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 23. |

| ↑9 | Over 200 objects are returned on a search for statuettes of the Virgin and Child between 1200 and 1400 on the Courtauld’s Gothic Ivories Project website, which is still adding new objects on a regular basis at the time of this writing (http://www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk/search/advanced.html, consulted 8/30/12). When expanded to include diptychs and triptychs featuring the motif, the number climbs close to 1000. Sarah Guérin has noted that one of the challenges of advancing general statements about Gothic ivories arises from the extremely large number of surviving objects and the impossibility of acquainting oneself with every known example. See Sarah Guérin, “Duplicitous Forms,” West 86th, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Fall-Winter 2011), pp. 196-207. |

| ↑10 | Raymond Koechlin, Les Ivoires gothiques français (Paris, 1924), I, p. 103; II, no. 86; III, pl. XXVIII; Danielle Gaborit-Chopin, Ivoires du Moyen Age (Freiburg, 1978), p. 139, no. and fig. 204; Charles T. Little, “Ivoires et art gothique,” in Revue de l’Art, 46, 1979, p. 63.; Images in Ivory, no. 18, pp. 148-149; François Bucher, “A Gothic Ivory Virgin and Child,” Bulletin of the Associates in Fine Arts at Yale, 23 (1957): 4-9. |

| ↑11 | Bissera Pentcheva, “The Performative Icon,” The Art Bulletin 88.4 (2006): 631. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2006.10786312 |

| ↑12 | Sarah Guérin has challenged the paradigm of frequent handling and touching of ivory devotional objects (“Embracing Ivory: a Seated Virgin and Child at the Cloisters,” paper delivered April 19, 2011, meeting of the International Society for Ethnology and Folklore, Lisbon, Portugal – abstract online: http://www.nomadit.co.uk/sief/sief2011/panels.php5?PanelID=795, accessed October 4, 2012). |

| ↑13 | John Lowden, Medieval Ivories and Works of Art: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto: AGO, 2008), catalog number 17. For an image of this work, see the Courtauld Gothic Ivories website: http://www.gothicivories.courtauld.ac.uk/images/ivory/07c97500_6c58e861.html, accessed December 4, 2013. |

| ↑14 | The term, haptisch, is Alois Riegl’s, developed in response to criticism of his use of taktisch in his Spätrömische Kunstindustrie (1901). For Riegl’s development of the concept and its reception in art history, see Christopher Wood, “Riegl’s Mache,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 46 (2004): 154-172, see page 168, note 32; Mechthilde Fend, “Körpersehen: über das Haptische bei Alois Riegl,” Kunstmaschinen : Spielräume des Sehens zwischen Wissenschaft und Ästhetik, (2005):166-202; Whtiney Davis, A General Theory of Visual Culture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 70-72 . |

| ↑15 | Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (St. Paul, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 545. Deleuze and Guattari are speaking of so-called “barbarian” or “animal style” art, but the fine distinction they make between the literalism of the mind touching “like a finger” and the more subtle operation of mental touch denoted by the term haptic is important. Film scholar Laura Marks has explored the concept of “haptic visuality” in her work on the role of touch in cinema: Laura Marks, Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media (St. Paul, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2002), xii-xviii, 3-7 in passim. |

| ↑16 | Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Kegan Paul (New York: Routledge, 2002 (1958) ), 370-371. Originally published in French as Phénomènologie de la Perception (Paris: Gallimard, 1945). |

| ↑17 | Oliver Sacks, “A Neurologist’s Notebook: To See and Not See,” The New Yorker (May 10, 1993): 65-66. |

| ↑18 | Ilene Forsythe, The Throne of Wisdom: Wood Sculptures of the Madonna in Romanesque France (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972). |

| ↑19 | Caesarius of Heisterbach, Caesarii Heisterbacensis monachi ordinis Cisterciensis Dialogus miraculorum [Textum ad quatuor codicum manuscriptorum editionisque principis fidem accurate recognovit Josephus Strange] 2 volumes (Ridgewood, NJ: Gregg Press, 1966; reprint of Cologne, Bonn, Brussels: S.M. Heberle,1851), vol. I, distinctio VII, capitulum XLIV, 62-63. English translation, The dialogue on miracles by Caesarius of Heisterbach, translated by H. von E. Scott and C. C. Swinton Bland, with an introduction by G. G. Coulton (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1929), vol. I, 525-526. |

| ↑20 | Cited by Paul Williamson, Gothic Sculpture, 1140-1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 7. |

| ↑21 | William Wixom, catalog entry #142 in Mirror of the Medieval World, ed. William Wixom and Barbara Drake Boehm (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1999), 120. |

| ↑22 | For Bernard, see Sancti Bernardi Abbatis Claraevallensis, “Sermo VI,” Opera Omnia: Sermones In Cantica Canticorum, Patrologia Latina vol. 183, ed. P. Migne (1854), col. 1280-1282, especially parts 6-9 (1281-1282). For Aelred, see Aelred of Rievaulx, De Iesu puero duodenni, in Oeuvres complètes de Saint-Bernard, volume 6 (of 7) (Paris: Vivès, 1867), 369. For critical discussion of these two texts in relation to one another see Michelle Sauer, “Cross-dressing Souls: Same Sex Desire and the Mystic Tradition in A Talkyng of the Loue of God,” in Intersections of Sexuality and the Divine in Medieval Culture: the Word Made Flesh, ed. Susannah Chewning (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), 153-182. |

| ↑23 | John of Caulibus, Meditations on the Life of Christ, trans. and ed. Francis Taney, Anne Miller, C. Mary Stallings-Taney (Asheville, North Carolina: Pegasus Press, 1999), 28. |

| ↑24 | Christine Klapisch-Zuber, Women, Family, and Ritual in Renaissance Italy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997), 323-325. |

| ↑25 | Jung, 232. |

| ↑26 | Corrie, “Coppo di Marcovaldo’s Madonna del bordone and the Meaning of the Bare-Legged Christ Child in Siena and the East,” Gesta 35 (1996): 43-65. https://doi.org/10.2307/767226 |

| ↑27 | Unfortunately, no detailed descriptions of the methods of medieval ivory workers, and no securely identifiable tools have come down to us. Parisian tax rolls begin to indicate a distinct profession of ivory carver (ivoirier) only in the 1320s. On the lack of extant tools and the similarity of techniques to wood carving, see Anthony Cutler, The Craft of Ivory: Sources, Techniques, and Uses in the Mediterranean World, AD 200-1400 (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1985), 37, 46. On the ivory market in Paris, see Elizabeth Sears, “Ivory and Ivory Workers in Medieval Paris,” Images in Ivory: Precious Objects of the Gothic Age, 18-37. |

| ↑28 | See Caroline Bynum, Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984 (1982 |

| ↑29 | Gavin Langmuir, History, Religion, and Antisemitism (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 163. |