Corine Schleif • Arizona State University

Recommended citation: Corine Schleif, “Introduction/Conclusion: Are We Still Being Historical? Exposing the Ehenheim Epitaph Using History and Theory,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/TZKB5241.

Preface and Acknowledgments

The volume had its beginnings in 2004 when sessions on Madeline Caviness’s theoretical model were proposed to the International Center for Medieval Art for sponsorship at the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo. Accepted for 2006, the sessions were honored with the distinction of commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the International Center for Medieval Art. In addition to issuing the open call for papers we invited individual scholars from as far away as Europe and Japan. Due to the overwhelming response, what began as a double session was expanded to five sessions. I would like to thank many who made these sessions possible: Alyce Jordan, co-organizer of the sessions and the chair of the ICMA program committee; Annemarie Weyl Carr and Mary Shepard, past presidents of the ICMA; Elizabeth Teviotdale, Associate Director of the Medieval Institute at Western Michigan University; and the presiders: Evelyn Lane, Elizabeth Pastan, Virginia Chieffo Raguin, Ellen Shortell, and Anne Rudloff Stanton. Not all the papers delivered are re-presented in the following volume. Many participants had otherwise committed their work or planned for its publication: Anna Bücheler, “Bilder im Auftrag Gottes: Zur Konzeption des Wiesbadener Scivias der Hildegard von Bingen,” (MA Thesis, Eberhard-Karls-Universität, Tübingen, 2003); Kathleen Nolan, Queens in Stone and Silver: The Creation of a Visual Imagery of Queenship in Capetian France (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, announced for 2009); Pamela Sheingorn, “Subjection and Reception in Claude of France’s Book of First Prayers,” in Four Modes of Seeing: Approaches to Medieval Images in the Honor of Madeline Caviness edited by Evelyn Lane, Elizabeth Pastan, and Ellen Shortell (Basingstoke: Ashgate, announced for 2008), 313-32; Debra Strickland, “The Holy and the Unholy: Analogies for the Numinous in Later Medieval Art,” in Images of Medieval Sanctity. Essays in Honour of Gary Dickson, edited by D. Strickland (Leiden: Brill, 2007), 101-20; and Sarah Stanbury, The Visual Object of Desire in Late Medieval England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008). The additional papers delivered were “The Bayeux Tapestry and Nazi Germany” by William Diebold, and “The Crucifix of St. John Gualbertus: The Creation of A Cult Image in Late Medieval Florence” by Felicity Ratté. Maija Kule was unable to deliver her paper “Visualizing Women in the Latvian Culture” due to unexpected bureaucratic difficulties associated with international travel. Anne Harris chose a topic different from that presented at Kalamazoo. My own article was also not presented at Kalamazoo, but resulted from my interaction with the other participants and my work on this volume.

Special thanks are due to Rachel Dressler, who, early on, even before the sessions had taken place, raised the possibility of establishing an online journal in which the otherwise ephemeral presentations could be expanded and circulated beyond the conference audience and more rapidly than is usually now possible with print media. She has acquired the support of the University of Albany and promoted the endeavor with her own efforts and resources, assuming the responsibility for those time-consuming tasks necessary for publication in any venue including copyediting, page design, and image reproduction. Different Visions will hopefully one day demonstrate that within the storms and urgencies that have been termed the crisis in scholarly (art historical) publishing, necessity can be a very nurturing mother of invention. Many thanks are also due to the anonymous readers who provided detailed and constructive reports on the essays as well as to my fellow members on the editorial board of Different Visions, Virginia Blanton, Richard Emmerson, Linda Seidel, Debra Strickland, and Christine Verzar, who offered advice and direction in initiating the journal and establishing its policies. In the course of the preparations of this volume a great deal of communication has taken place among the contributors and editors, many of whom have sought input and criticism from one another and to a far greater extent than that to which we are accustomed in conventional journal publishing venues. I hope that this is a sign of new modalities on the horizon that will one day supplant the current process that requires editors to persuade colleagues to join them and invest their time and research efforts in developing an anthology on a topic after which individually and collectively all must wait patiently for a thumbs-up or thumbs-down decision from a publisher whose proficiencies more often than not lie in marketing and not in the discipline of art history or in historical and/or theoretical scholarship.

Background and Foreground

The essays that follow adopt and adapt, explore and expand an approach to the medieval art object that Madeline Caviness has dubbed “triangulation.” The pioneering role of Professor Caviness in pursuing critical and theoretical goals provides the a priori condition for this volume. The endeavor is devoted to the methodology that Caviness first proposed in an article in 1997, more consciously developed in her book Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy in 2001, and subsequently articulated as a diagram in her e-book Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries in 2002.[1] This project is conceived as a tribute to her unflinching pursuit of issues not only specifically historical, but broadly theoretical and sharply critical. Further, this current publication is dedicated to the work of those who have employed the methodologies espoused by Caviness. It is meant to address all whose critical methods have been denigrated, whose contributions, when theoretically grounded, have been refused for publication, or whose critical insights have been expunged by editors, peer reviewers, and publishers. For obvious reasons this remains a virtual community, whose members remain unaware of each other, but it may be cultivated as a conscious epistemic community whose members seek support from one another. In this vein, it is hoped that this e-publication will rekindle discussions about methodology and encourage those who see the necessity of using critical theories as well as those who endeavor to employ historical specificity along with postmodern theory.

Potential participants were asked to develop essays that employ the Caviness model, which triangulates between critical theories and historical contexts, or that expand, refine or even refute the model. Along the way contributors were given further encouragement to state their methodologies and approaches up front rather than to leave it to readers to analyze or tease out the theoretical frameworks that motivated, informed or facilitated their work. The essays published here were the result.

Notions of Inter-Viewing, viewing into, and viewing ourselves occupy the center of this publication. Kathleen Biddick opens the work of the medievalist on a note of enjoyment, including the capacity to incite curiosity and wonder. On the basis of an interview with Madeline Caviness, Biddick shows the person, the career, and the writing of Caviness in terms of “shattering,” “grafting,” and “queer performance.”

One circle of essays considers a self-conscious assessment of critical theorizing. In her brief reaction to the research presented in the five sessions, Caviness includes some personal notes about herself and other participants in an effort to show the dilemma that is currently facing those who engage critical theory in their work on the Middle Ages. She encourages opposition to what some have feared and others have celebrated as “the end of theory.” Charles Nelson’s essay grows out of years of teaching critical theory in a literature department and interdisciplinary team teaching with Caviness at Tufts, as well as more recent collaboration with her in research and writing. He first explains the background and genesis of the triangulation model in literary theory, and, exploring texts and images from the Sachsenspiegel on which their current collaborative research is based, employs speech act theory (a historically current critical theory, the right leg of the triangle) to analyze the subtle ways in which the text reveals the anxiety of the author/narrator, Eike von Repgow, with respect to the absence of his authority in writing this law book (a historical source, the left leg of the triangle). In the essay following, I point out the ways in which not only critical theory but also the historical specificity of objects and sources is currently neglected in North American art history publications. I suggest that historical contexts can be explored by using the material object and written sources in order to perform particular history through the anthropological approaches of thick description and emic recording or empathic storytelling. To develop these methodologies I address the Ehenheim Epitaph, and scrutinize underdrawings and political records. The juxtaposition of individuals clad in exotic fabrics and fur with a fully exposed Man of Sorrows invites inquiries within current discourses of gender and animals in society as well as those of postcolonial theory.

The largest ring of explorations facilitates views of specific medieval objects, works of art, or categories of works. In an extended version of the plenary talk delivered at Kalamazoo in 2006 and sponsored by the Medieval Academy of America, Madeline Caviness herself triangulates visual constructions of goodness and evil, particularly those related to race and skin color, as they occur in twentieth-century Italo-westerns as well as parallel manifestations in thirteenth-century European art. Expanding her geometrical model to one that is three dimensional, she views these two historical phenomena as occupying parallel planes, the one closer to present-day audiences than the other. Rather than claiming a cause common to both, she distinguishes the specific historical circumstances of each, explores the self-fashioning of the “whiteman” as a performative, and postulates “psychological conditions that operate as causes and effects in a cycle of fear and aggression.” Her close scrutiny of stained glass, manuscript illuminations, and wall paintings, including observations on changing techniques and methods of production exemplifies the ways in which medieval art can be employed to examine social issues on a very particular level. Anne Harris re-examines the Shoemakers’ Windows at Chartres Cathedral and proposes an alternative interpretation to this often-studied stained glass. Triangulating Martin Heidegger’s theoretical notions of “Dinglichkeit” (usually translated as “reality” but with emphasis in his thought on literal “thingness”) with the historical circumstances involving the shift to and dependence on a monetary economy, specifically with its implications for the tradespeople, Harris proposes new views on the self-reflexive display of the windows represented within the windows as discrete objects. Karl Whittington demonstrates the ways in which late-thirteenth-century physiological drawings of the female body are mapped onto an image of the crucified Christ. In so doing he juxtaposes diverse but imbricated discourses from the Middle Ages and argues that the designers and writers of these annotated diagrams were projecting a male perspective for their viewers/readers. Rachel Dressler analyzes the Gyvernay family chantry chapel and tombs at St. Mary’s Church in Limington. Using historical sources she demonstrates how Richard Gyvernay lacked many of the salient characteristics of knighthood but profited socially and economically from his marriage with Gunnora, his second wife, who contributed the manor of Limington. Dressler contrasts these sources with the material features of the tomb sculptures—the ostentation of Richard’s effigy with respect to the reduced size and inferior internal positioning of Gunnora’s effigy—to show how she was abjected in order to deny her significance in constructing Richard’s masculine knightly standing. Sarah Bromberg takes up the enigmatic early fourteenth-century prayer book known as the Rothschild Canticles, which, although it has attained canonical status and is now included in survey textbooks, has been the focus of very few publications. Bromberg poses different possible historical contexts and argues for various gendered and ungendered readings of the devotee figures, which play an important role in the iconography. Viewing the images in the context of the accompanying texts, she, for the first time, provides a transcription of the particular texts that she analyzes as well as an English translation. Martha Easton takes up secular images from the Middle Ages, images of nudes in books of hours, ivory mirror cases, and the sheela-na-gigs. Using the material objects, including signs of their use or abuse, together with historical readings of them, she triangulates these views with postmodern gender theory. Notions of the scopic economy are of particular interest to Easton, as she departs from the often invoked notion of the dominant male gaze to include not only the homoerotic gaze but also the pleasurable gaze of the female on the female body and the appreciative look of a woman apprehending a male body. Linda Seidel returns to the Ghent Altarpiece and, taking up new formalism as her present-day theoretical approach, she points to one underinterpreted feature of Adam, his suntanned hands, and one completely ignored feature of Eve, the linea nigra on her swollen abdomen. By making ordinary objects appear extraordinary—Seidel’s working definition of formalism—she posits that Jan van Eyck was drawing attention to the craft of painting.

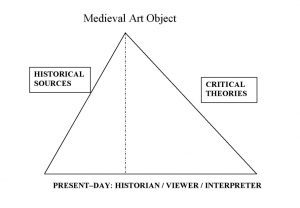

Triangulation – Among Other Paradigms of Art History

Caviness presents her methodology in a diagram (Figure 1), which, as Charles Nelson points out in his essay, is “elegant in its simplicity.” She proposes to “pry open” visual works from the past, not in order to get inside them and understand them for their own sake, but rather to expose them and let them out into the present world. By approaching the work obliquely from two directions, through historical sources and through critical theories, Caviness endeavors to disrupt the usual comfortable viewing habits of present-day museum-oriented audiences. She wishes to create tensions that are brought to bear on the object, wrought by the levers of two diverging viewpoints and thus to open the work up to offer new insights for today. This does not mean that the diagram’s intent is dogmatic or that we have here to do with an overarching explanation for cultural production, cultural consumption, or the place of artistic enterprises within cultural production. As Caviness explains, the diagram was conceived as a chalk drawing on a blackboard, that tradition that may still be the most effective interactive, mutable and discursive medium for classroom teaching. In my opinion the diagram carries added advantages not only as a picture serving as a mnemonic and didactic device, but also as a name with certain semantic utility. In this case a woman has not only developed a theoretical diagram and metaphorical model, but also named it.

Fig. 1. Caviness’ methodology in a diagram

Charts, diagrams, and visual metaphors have long been favored by art historians when promoting conceptual methodologies. Perhaps we are particularly prone to visualizing our own doing. To date perhaps two of them have had the most impact on our discipline: In the second decade of the twentieth century Heinrich Wölfflin established the long held art historical conceit of comparing and contrasting by proposing his five binary pairs of formal stylistic characteristics, which he aligned into an implied vertical chart, easily translated into the practice of projecting two images side by side. Using these polarities he distinguished both the shifts of periods, particularly the Renaissance to the Baroque, and the divides of topography, especially the Italian from the northern European or German.[2] Erwin Panofsky subsequently proposed a procedural chart with three levels: pre-iconography, iconography, and iconology to be followed by those wishing to expand art history beyond formal issues of periodization and nationalization (or naturalization?), in order particularly to engage in the new art historical pursuits of decoding the disguised messages that artists with the help of advisers placed into their pictures.[3]

To these I would like to add the diagram that emerges for me from my reading of “Semiotics and Art History” by Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson, one that is only verbally suggested and never concretely articulated. Bal and Bryson first liken the artist to the neck of a funnel into which flow all the influences and causations of the work of art. In their subsequent discussions the model is implicitly expanded to that of two funnels connected, somewhat resembling an hourglass turned on its side. The work of art at the place/moment that it through the artist comes into existence or appears in the world can be imagined at the narrowest portion of the hour glass. Without dimensions, this point occupies neither space nor time; it is therefore imperceptible in and of itself. The funnel to the left of it can be viewed as the space containing all the texts, previous works of art, technical developments, artistic influences, artistic training and maturation, political and economic circumstances — all that existed before the work came into being that feed into it; on the other hand, the funnel on the right represents the diffuse trajectories of all the signifieds that emerge from the reception of the work involving infinite numbers of viewers, viewings, and meanings.[4]

If we broaden our scope to include concepts, terms, and structural paradigms that were invented to show the relationship of a work of art to other forms of cultural production, the list of examples grows substantially. Panofsky, borrowing a term from Ernst Cassirer, described various historical systems for conceiving of perspective, i.e. recognizing, constructing, and rendering three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, as “symbolic form.”[5] Later Panofsky asserted that Gothic architectural vocabulary as well as developmental processes were linked with scholastic thought through what he dubbed was a “mental habit” of the thirteenth century.[6] Somewhat similarly, Baxandall developed his notions of the “period eye” to demonstrate correspondences in material and visual products wrought by a given culture at a particular time.[7] Not to be overlooked is likewise the older structural diagram proposed by Ernst Gombrich in an attempt to show the various manifestations of a given culture as radiating from a common center like the spokes of a wheel.[8] The various attempts to adapt and refine the two-layered structure of base and superstructure have likewise occupied many Marxist and post-Marxist art historians as they have endeavored to work out nuanced ways of showing relationships between variously defined kinds of economic and cultural production. To be sure, all of the above can also be used to chart the historical course of the discipline and its ever-changing concerns.

Unlike any of the previous paradigms, triangulation makes the viewer of the present day its raison d’être. It likewise grants great agency to this current observer and thus it gives broad place to the authorial “I.” This place I would argue is not a self-aggrandizing insertion of authorial voice as some editors may view this practice, nor is it a result of overconfidence as some colleagues perceive the pronoun when it appears in students’ work. Rather it is the modest assertion that the author recognizes that s/he is not the purveyor of timeless facts and eternal truths.

At the apex of the triangle, Caviness places the medieval art object— not all of them, not all of a particular time period, not all that depict a specific iconographic subject. Also in this respect the diagram is less universalist than most of the other paradigms enumerated above in that it does not presume to stand at some pinnacle of history and pretend to look down upon and survey either the essences of a particular period, such as the Middle Ages, or the essences of cultural production and the relationships of the production of visual art to other kinds of cultural production. The position it takes up is not that of God, operating from outside the space-time continuum. Thus it likewise implicitly allots much agency to the (medieval) work of art and its makers, designers, sponsors, audiences, and other facilitators. With respect to establishing or upholding various hegemonies, these works and the persons behind them can be aggressive and celebratory, they can be collusive and complicitous, or they can be oppositional and defiant. Often complex combinations of the above can be observed when pressure is brought to bear from two viewing sites, some of the positions negotiated, others occurring by default.

The two legs of the triangle, the two paths to the medieval work of art, the two approaches toward opening the work and making it accessible have not been in the past nor are they consistently now considered equally valid or acceptable. Discovering and defining the historical context has long been a more favored pursuit of art historians, as reflected in the various charts and diagrams mentioned above. Yet, in the Caviness diagram, critical theory provides the longer and therefore more forceful and effective lever for opening the medieval work of art and making it accessible and useful to audiences of today.

The engagement of critical theory that we here espouse often runs against the grain, as Caviness herself laments in her response essay in this volume, when she poses the question whether we have reached the “end of theory.” I would maintain that the current relative disappearance of theory has occurred for a number of reasons. Our discipline of art history has established its footing as part of the “feel good” apparatus of cultural production and therefore has great discomfort with methodologies that are critical. (Historical) art with all of its presences that involve affirmations of (past) humanity, celebrations of (past) human achievement, and articulations of allegedly timeless human values must tower above all that is critical. Western art and art history were both born of sixteenth-century humanist notions of valiant individual artists who created masterpieces that superseded the standards of their craft and the purposes of their sponsors. Both the idea of art and the practice of its appreciation and history were further nourished by specious enlightenment claims of egalitarian disinterestedness, universal pleasure, and goodness barred to none. In a viciously competitive world, art provides the escape of choice, offering deliverance from and denial of the dog-eat-dog competition of the retail establishment, the office, the board room, or the bank, as a conveyance to a realm of (apparent) gentility and graciousness motivated by generosity and supported through donations and volunteerism.

Art exists beyond those tugs of war waged by parish pastors and large religious institutions that so embarrassingly pull at the heart strings in order to open the purse strings–those heart strings that tie personal piety to narrow interests entwined with ancestral national proclivities, ethnic origins, and class orientation. A reverence for art, especially perhaps the art of the past, including that of the European Middle Ages, which was only subsequently deemed to be art and which has stood the test of time, collecting on its surfaces the rich patina of looks, stares, and gazes that many generations of admiring viewers left behind, promises to lift devotees to those imagined realms that transcend religious boundaries and denominational pettiness, to provide that which is truly universally edifying. The cost and level of allegiance, i.e. membership fees, are graduated according to class and pocket book, ranging from collecting, to supporting museums and public art, to acquiring college degrees in art history, to buying coffee table picture books and posters. With such effective all-embracing powers to hail ideologically, art does not well tolerate criticisms that penetrate it from contexts external to it. Perhaps due to their apparent and comparative immediacy, works of visual art from the Middle Ages are again considered sacred images in a manner in which medieval texts are not today honored as holy writ and Gregorian chant is no longer perceived as divinely angelic. Is it any wonder then that interrogating the possible darker sides of visual images and opening them in order to view their intrinsic power is considered heretical and that deconstruction is perceived as the equivalent to destruction, perhaps even akin to the deeds of axe-wielding iconoclasts who destroyed medieval audiences’ sacred images in rages fueled by fear of the potential power of these images?

Are We Still Being Historical?

What of the short leg of this scalene triangle? For a number of reasons I would like to address the advantages, indeed the necessity of investigating historical contexts. Madeline Caviness has already put great effort into explaining the longer leg, that which stands for theory, which she favors, believing it can be used as a more effective lever in opening the work to audiences of today. Further, Charles Nelson has chosen to contour the history and genesis of this more important leg of the triangle.

My opening question plays off of Nelson’s question, whether we are being theoretical yet, a question he posed by turning around Carolyn Porter’s question of 1988, whether we are being historical yet.[9] With her query she addressed the then new “new historicism” of Stephen Greenblatt and others, who were, first of all, endeavoring to replace ahistorical formalistic methodologies in literary studies, which had largely been dominated by practices of comparing and contrasting works of literature only to or with each other, and, secondly, attempting to present an adjustment to historical materialist theories that had often proven both teleologically reductive and deterministic. New historicism promoted the inclusion of nonliterary texts in the discursive field.[10] Using postcolonial criticism Porter advises an even more broadly discursive historical contextualization of sources and voices than that employed by Greenblatt.

Written historical sources have long been my particular bailiwick, to the extent that I have often felt more at home in archives than in museums. To those art historians who have never ventured into archives and perhaps seldom search through editions of documents I would recommend it. We cannot always rely on our historian colleagues to do our detective work for us since the issues we pursue and questions we ask are not always those that motivate historians. Art historians can make good archival sleuths. We are poised to see through the ideological veils of those marks on parchment, words on paper, or typescript on pages since these are the materials of our own quite imperfect craft and arbitrary trade, more than are paint and glass, wood and stone.

As this presentation and publication project has progressed, I have come to recognize that the short side of the triangle, too, is increasingly threatened by current practice. I would see in Caviness’s diagram a far more urgent call for historicity than merely a balancing of approaches or a nod to traditional methodologies. Even if indeed the often romantic images of the past that pretend to associate visual art with its original historical contexts make historical methods less threatening than those that critically and theoretically question what appear to be the very foundation of our discipline and all that renders it worthy of public and private support, critical historicity is at risk. I would posit that in the last years, art history, including the part of it that examines the Middle Ages, has fallen away from its earlier interests in interrogating objects within their complex and contradictory historical contexts. Perusing the titles of books that are appearing from university presses and commercial scholarly publishers, I observe that studies painted with a broad brush and covering whole topographies and/or encompassing one or more periods and engaging wide general topics have come to replace the careful (re)examination of a specific work or group of works within historical contexts. Surveying the English language art historiography of the moment—especially that produced in North American—I apprehend a landscape in which the dikes have broken and publications full of shiny full- color digitally derived illustrations spread out in all directions, but few of them have any depth of specificity. Publishers targeting those lucrative so-called crossover markets for undergraduate textbooks and general coffee table books are rolling art history back to the ways it was practiced several generations ago but with few if any footnotes, which would reveal to its passengers that they have shifted into reverse.

The focused attention to and study of written records appears to be in noticeable decline. Of the many new medieval sources, which have come to light both on patronage and on technique that are referenced by English-writing authors of the last decades, few have been translated and made available in print. For the frequently cited standard texts, De diversis artibus by Theophilus and Il Libro dell’Arte by Cennino Cennini both mentioned by Linda Seidel in this volume, we must rely on old translations and text commentaries although in recent years new studies have appeared in German and Italian.[11] Remarkably the situation appears to be more grave in art history than in the fields of literature and history, which have in the last years produced many new compilations and translations of literary texts and historical records including (auto)biographical writings. Moreover, the time-honored art historiographic traditions that persisted into the 1980s of including the original language and an English translation have not been maintained.[12] The situation for materials appropriate for university courses is similar. Although the University of Toronto Press, through the Medieval Academy Reprint Series, continues to make three of the old editions of translations of selected sources and documents available in paperback, inexpensively priced for students’ pocketbooks, and Elizabeth Holt’s work is also still in print, many years have passed since any new collections have appeared that can be used to whet students’ appetites for archival study.[13]

The situation for monographs with a high density of historical information presented discursively can likewise be quite revealing. If, for the sake of providing a manageable overview, we limit ourselves to what we might roughly consider the Romanesque period, we can quickly detect changes in the books available for art history scholars and advanced students. Books centering on a particular genre, such as Illene Forsyth’s The Throne of Wisdom, which examines archival records, literary texts, and theological treatments along side the material art objects, are now rare.[14] Likewise, monographs such as Pamela Sheingorn’s The Book of Sainte Foy and the subsequent volume by Sheingorn together with Kathleen Ashley, which present translations of historical sources surrounding one work of art along with critical interpretations and theoretical insights (the other side of the triangle) into the ways that this object performed ideological work, are scarce since the dawn of the twenty-first century.[15] The same is true of studies that pay careful attention to patronage in a particular place and consider sources while critically tracing and contrasting (art) historiography as Caviness did in Sumptuous Arts at the Royal Abbeys in Reims and Braine or as Seidel did in her consideration of the famous Gislebertus inscription in Legends in Limestone.[16]

Much historical and theoretical work remains for scholars studying medieval art. In many cases, objects have only been catalogued with the purpose of determining how each may formally fit into the larger set of like objects. With materials, dates, and provenance of works of art abbreviated as acquisition numbers and articulated as short labels, museum galleries filled with figures of saints or Madonnas or crucifixes often resemble a morgue with rows of corpses, each tagged with brief information. Once these works were part of a living social environment; they were loved (and hated); they provided a livelihood for artists and craftsmen, they served to further their donors’ eternal salvation, they participated in public rituals, they were the objects of intense personal devotional fervor, and they furthered, limited, or challenged social hegemony.

Caviness lobbies for “thick description,” a term made famous in an essay first published by Clifford Geertz in 1973.[17] The simple often quoted analogy that Geertz borrowed from Gilbert Ryle involves the motion of blinking one eye. The movement can be unwanted and unintended as with an involuntary twitch, it can involve intentional, unobtrusive communication as in a wink, or it can potentially be used as mockery or ridicule, which might even involve practice and rehearsal. At face value none of these instances can be distinguished from the others, i.e. a camera would record these acts as identical. Only the complex background of context can determine the meaning, and this is already reflected in the words used in the descriptive narrative: twitch, wink, blink. Thick description is not naive description or, applied to art history, the identification of every historical object, person, or event pictured in the image, i.e. the pre-iconographic level in Panofsky’s chart mentioned above; nor is it simply the unlocking of the historical meanings of each of the above, i.e. the iconographic level. Rather it involves the consideration of complex contexts to determine meanings. In some respects thick description is closest to the third level in Panofsky’s chart, i.e. the total iconological program intended through the image, but this would only provide one thin single strand of narrative and even then procedurally we would have to turn Panofsky’s chart upside down asking first the question of the larger historical purpose. What is more, the practice of thick description calls into question the validity of neutral terms, the very foundation on which Panofsky’s step-by- step process is based. Geertz underscores the necessity that every description is ineluctably interpretive. Thus the concerns that make up the short leg of the triangle and leverage the medieval object by way of historical context do not therefore pretend to constitute a unified and stable historical reality.

In fact, the endeavors of the short leg of the triangle do not purport to achieve any historical reality. The short leg of the triangle, in the German words so often used to connote a detachment and specificity separated from common everyday English parlance, does not claim to determine “wie es eigentlich gewesen [ist],” perhaps best translated as “how it actually truly was.”[18] The problem is not merely a practical one—that it is impossible to reconstruct the complexity of past contexts and experiences for today’s audiences, but it is an epistemological one–that it is impossible even to claim to know what they actually were. As a logical consequence it may seem that audiences of today should be free to interpret only for and from the present moment. But it is here that the triangulation model offers some caution against the hubris and chauvinism of our own historical moment, lest we think we are perched as it were at the highest point of the teleological slope of progress. I have paraphrased Geertz’s optimistic assertion, the last sentence in his short essay on thick description and altered it to fit the situation for present-day viewers of medieval works of art wishing to understand historical contexts: The essential calling of interpretive art history is not to answer our deepest questions, but to make available to us answers that others, protecting other identities, other policies, and other economies in other eras, have given, and thus to include them in the consultable record of what human beings have seen and said.[19]

As we scrutinize historical contexts with a macro lens with the goal of writing for the “consultable record” we might do well to borrow some other precautionary methodologies from the anthropologists’ tool kit. Ethnographers have often argued the comparative merits of emic and etic approaches to their material. An emic approach to gathering information and writing about that information favors the use of terms and descriptions that are close to the experiential perspective of groups being studied, as opposed to etic concepts that are more distanced and closer to the analysts conducting the studies. Many anthropologists have chosen the emic over the etic on ethical grounds.[20] We as art historians of the Middle Ages, who do not deal with living human subjects, may have slightly different reasons to choose the emic approach. Allowing our historical subjects to speak with their own voices facilitates understanding across time. I am not recommending that we dispense with analytical terms of our place and time, but these belong consciously separated—on the other leg of the triangle. The emic underscores the importance of being able to access materials in original medieval languages as well as the importance of providing reliable critical translations of important texts or quotations. It favors terms that show respect for medieval concepts of liturgy, ritual and theology, governmental forms, and social practices rather than immediately transforming specific vocabulary into ahistorical yet non-analytical nomenclature. For example, I would encourage the use of loci sancti rather than “zones of veneration” to refer to the places inside and outside of churches that were marked with art work or performances for the celebration of specific feast days in the liturgical year. These cautions might serve us well in resisting the urge to ventriloquize while furthering our ability to empathize and our capacity to sympathize in order to facilitate the formation of virtual epistemic communities over time, which can prove useful in understanding the contradictions of collusion and complicity and in observing the complexities of ideologies at work in works of art. For art historians this may involve informed speculation and the risk of imagining one’s self transported back into a given (historical) situation. This does not mean, of course, that one uses the art object to wish or whisk one’s self back into the Middle Ages. Geertz writes that only a romantic or a spy would wish to become or to mimic a native.[21] With respect to art historians and the natives of the Middle Ages, the spy is the colonialist voyeur who subjects medieval art and artifacts to his gaze in order to control that which would challenge his hegemonic position in history; the romantic is the escapist, self-delusional viewer who compensates for that which she lacks in the present through wistful projections into the past.

In order to avoid both the pitfalls of determinism and the recuperation of stereotypes, I would also advocate the pursuit of “particular history.”[22] In many respects art history cries out for this methodology even more than does the discipline of history itself. History’s individuals and events have not survived, but art history’s art has. The materiality of the work itself and its formal qualities offer great clues to its living environment and the various settings it once occupied. These include not only its representational contents or functions but the substances that comprise it, the techniques and talents employed to create it, its self-referentiality, and the marks of use and abuse left on its surfaces, all of which can be employed not only to order it among other objects of its kind but also to learn its stories. These stories need not be chronological narratives woven as a chain of causes and effects, they can be constituted as (con)texts. Scrutinizing the particular, i.e. that which art history has deemed insignificant and therefore ignored, we are enabled to find more than just countless new examples that fit the larger pattern. We can examine contradictions, complicity, compensations and negotiations. Particular history as opposed to universal history allows us to include the traces and reflections of those who resisted hegemony but failed, and therefore do not belong to any of the grand narratives of history.

In 1988 Carolyn Porter answered her question “Are we [literary historians] being historical yet?” with “no.” In 2008 I answer my question “Are we [art historians] still being historical?” likewise with a “no.” If historicism was approached and achieved somewhere in the time intervening, at least for art history, it was very short lived.

The Ehenheim Epitaph

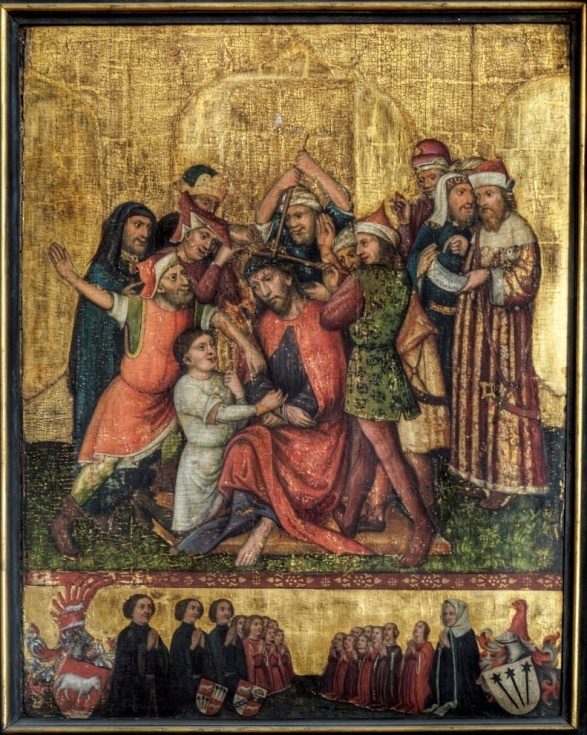

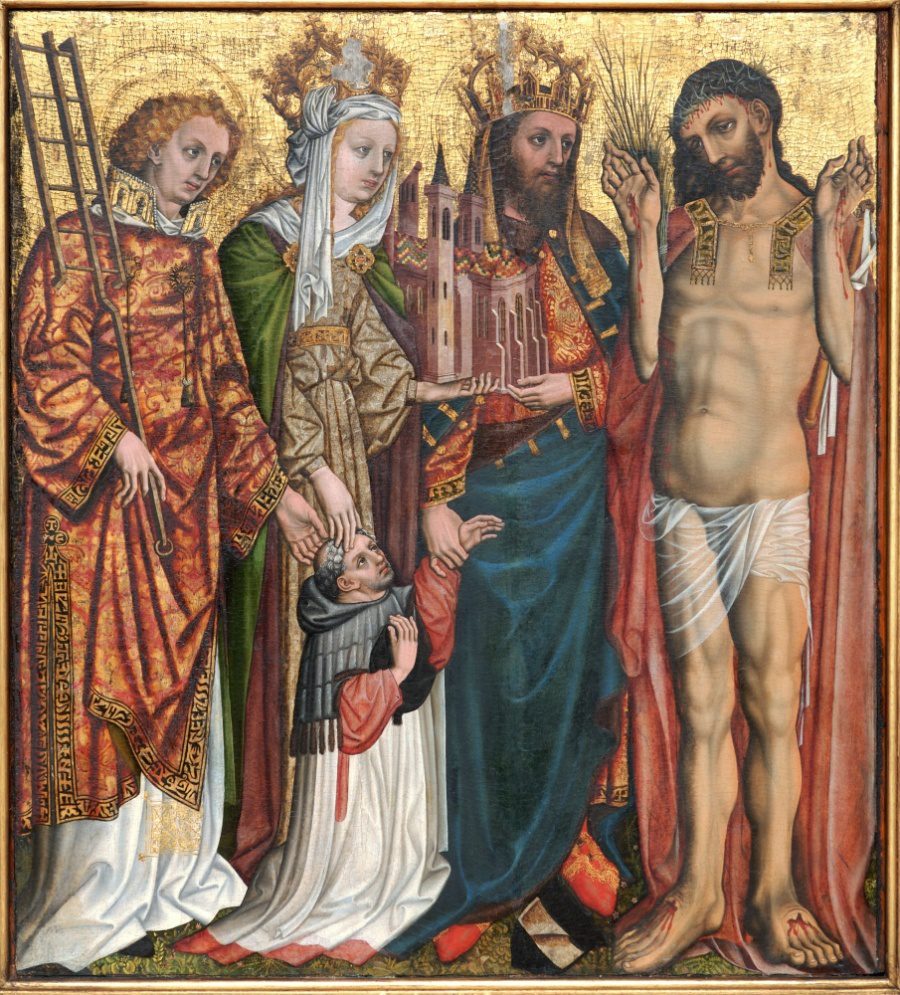

The Ehenheim Epitaph (Figure 2) presents a welcome opportunity to engage in particular art history using thick description, emic concepts, and informed speculation to leverage from the side of historical context as well as to apply pressure with the longer lever of critical theory. Technical analysis, cleaning, and restoration has just been completed on this panel, measuring 113 by 102 centimeters, which has hung in the parish church of St. Lorenz in Nuremberg since it was painted following the death of Dr. Johannes von Ehenheim in 1438.

No archival records about this work from the time of its origin have survived. In fact, even the inscription portion of the epitaph, which in Nuremberg was usually on a separate board, either fashioned as part of the frame or mounted at an angle to provide a kind of protective roof, has been long lost. It is not included in the oldest surviving collection of inscriptions, that compiled by Johann Helwig dating from the middle of the seventeenth century.[23] In the inventory compiled for the church between 1823 and 1827, Johannes Hilpert noted that the panel hung on the first pier on the north side of the choir—according to the standard numbering system in use today, N iv. In the floor nearby, a bronze inscription together with a full-figure effigy, marked von Ehenheim’s final resting place until the stripping and removal of nearly all the bronzes at the beginning of the nineteenth century.[24] This grave assumed a most prestigious location within the church before the building of the hall choir, the position directly before the high altar and between the choir stalls occupied by the clergy. Even in the absence of any direct records from the time, a complex story—or stories—full of tensions and contradictions emerges from the work itself in its discursive relationships with other historical texts surrounding von Ehenheim and his contemporaries. Previous literature, including my own publications, has not made use of most of the edited documents in which von Ehenheim appears.[25]

Fig. 2. Epitaph for Dr. Johannes von Ehenheim, 1438 or shortly thereafter, Nuremberg, St. Lorenz (photograph: Volker Schier)

Historical Sources

Documents point to von Ehenheim as a potentially important figure in the power struggles between the bishop of Bamberg and the civic authorities of the autonomous imperial city of Nuremberg, who strove to name their own appointees to the prestigious office of pastor of this parish. Von Ehenheim was named by Bamberg in opposition to the Nuremberg candidate, Konrad Konhofer. Not giving up easily, the Nuremberg City Council arranged for another well-paid prebend in exchange for the Nuremberg post, but, contrary to all expectations, including those of Bishop Anton von Rotenhan himself, von Ehenheim refused.[26] It is unclear, however, if he ever took up residence in Nuremberg since he died about a month after he had taken office.

Coming from a family of imperial knights, Johannes von Ehenheim had the prerequisite aristocratic pedigree for membership in the cathedral chapter. In 1424 Johannes was appointed to this office through papal approbation (auctoritate apostolica).[27] Unlike most cathedral canons, von Ehenheim had been ordained a priest and had enjoyed a university education culminating with a doctorate in canon law.[28] By 1430 he had been appointed vicar general, a position that made him second in rank to the bishop in the diocese, afforded him many episcopal rights, and charged him to represent the bishop in his absence.[29] In 1432 and 1433 he participated in the Council of Basel in the stead of the bishop.[30] Many surviving charters and other documents bear von Ehenheim’s name and seal.

In 1435 he was involved in the Bamberg immunity controversy, which had erupted into armed conflict between the citizens under the municipal court and those in the so- called immune districts, belonging to the collegiate churches and the Benedictine abbey, and under the protection of the bishop and the cathedral chapter.[31] The primary issues were the lack of a unified lower court system and the refusal of those living in the immune districts to pay municipal taxes and thus share in the financial responsibility for civic projects. Partially as a result of von Ehenheim’s efforts, the clergy succeeded in squelching the uprising and some important families left Bamberg for Nuremberg, a city that offered more rights and privileges to the burgeoning merchant class. It is thus quite understandable that the Nuremberg City Council did not welcome the appointment of this well-known and powerful individual and that the council did everything it could to prohibit him from taking office.

Orchestrating the Visual and the Tactile

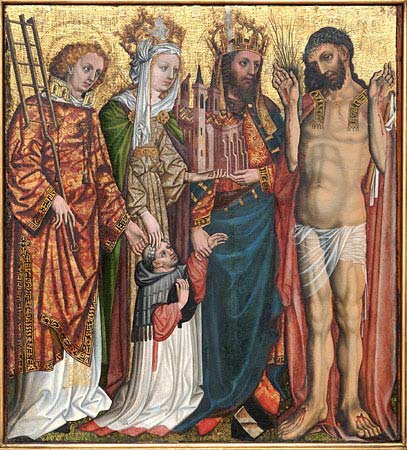

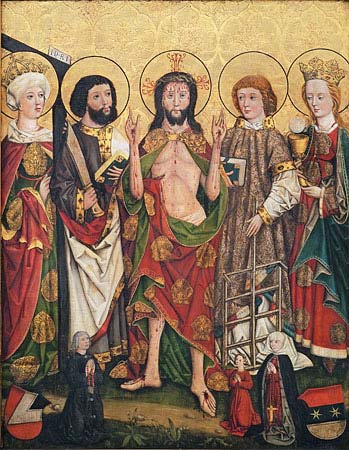

Looking first at its composition and comparing it with other Nuremberg epitaphs, I can make the following observations: Von Ehenheim is not banned to a separate lower zone as was the situation for the deceased and their families in most such memorial images in Nuremberg during the late Middle Ages (Figures 3 and 4). Like other clerics he shares the space of the saints (Figures 5 and 6). Unusual is the asymmetrical arrangement of the figures with the Man of Sorrows on the far right and not on the central axis, the usual position for Christ or the Virgin (Figures 6 and 7). Highly unusual, as I have discussed elsewhere, is the assortment and choice of gestures.[32] Saint Lawrence, titular saint of the Nuremberg parish, imparts the most common gesture of saintly patronage, that of commendation, a friendly pat or nudge on the back of the shoulder or head. However, Empress Cunegond and Emperor Henry II, saints of the Bamberg diocese, employ two means of physical contact found very rarely in epitaphs. Cunegond gently caresses Ehenheim on the forehead as if anointing him, while Henry grasps the cleric by the wrist. The latter gesture could carry both positive and negative connotations, with contexts ranging from its most common usage in scenes of Christ’s Descent into Limbo, in which it is employed to show that Adam and Eve were liberated by Christ and not by their own merits or power, to its appearance in the Sachsenspiegel, in which it is used to denote the crime of a man raping a woman.[33] In her article in this volume, Sarah Bromberg points to its use in the image of Christ leading the sponsa (Bromberg, Figure 5). In the Ehenheim Epitaph the array of highly differentiated gestures is intensified by the artist’s almost exaggerated attention to the specific and sometimes irregular contour of each individual finger (Figures 8 and 9).

The complex relationships are orchestrated through a diagram of vectors showing directional forces of varying magnitude creating tensions between tactile and visual experiences. Christ alone stands untouched and untouchable, but naked, he is fully accessible visually. The three saints form various tactile bonds with the devotee, but this touching is not mutual touching; von Ehenheim does not touch, he is touched, and independently, by each of them. At the same time, as if taking up his cause through these physical links, each saint intercedes on von Ehenheim’s behalf by looking beyond the other saints each delivering a petition directly to Christ, through the eyes. Cunegond and Henry take the lead, while proffering, as it were, the model of the cathedral they donated in Bamberg at the turn of the first millennium, and thus making it once again an object of gift exchange and not merely their identifying attribute parallel to Lawrence’s grille. Von Ehenheim, kneeling below, his line of vision unobstructed, also directs his eyes toward Christ, who answers with an approving nod and look of compassion. Only von Ehenheim and Christ are locked in a mutual stare. Martha Easton similarly observes the particular configuration of the looks and gestures in Jean Fouquet’s Melun Diptych, which also culminates in eye contact between Etienne Chevalier and the Christ Child (Figures 10 and 11). Dieter Koepplin has discussed the notion of chains, ladders or stairways of intercession.[34] Even more than that of the Melun Diptych, the constellation of the Ehenheim Epitaph confounds conventional hierarchically mediated approaches to the Godhead.

Fig. 3. Epitaph for Klara Münzmeister Löffelholz, 1437 or shortly thereafter, Nuremberg, St.Sebald (photo: Volker Schier)

Fig. 4. Epitaph for Margaretha Zollner Löffelholz, 1448 or shortly thereafter, Nuremberg, St. Sebald (photo: Volker Schier)

Fig. 5. Epitaph for Georg Rayl, 1494 or shortly thereafter, Nuremberg, St. Lorenz (photograph: Volker Schier)

Fig. 6. Epitaph for Jobst Krell, 1483 or shortly thereafter, Nuremberg, originally St. Lorenz, today Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Fig. 7. Epitaph for Ursula Haller, 1482 or shortly thereafter, Nuremberg, originally St. Lorenz, today Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Fig. 8. Detail of Patrons’ Hands on von Ehenheim in his Epitaph

Fig. 9. Detail: Right Hand of Saint Lawrence, Ehenheim Epitaph (photograph: Volker Schier)

Fig. 10. Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych, Left panel, Saint Stephen and Etienne Chevalier, ca. 1451, Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie

Fig. 11. Jean Fouquet, Melun Diptych, Right panel, Virgin and Child, ca. 1451, Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten

Christ Exposed

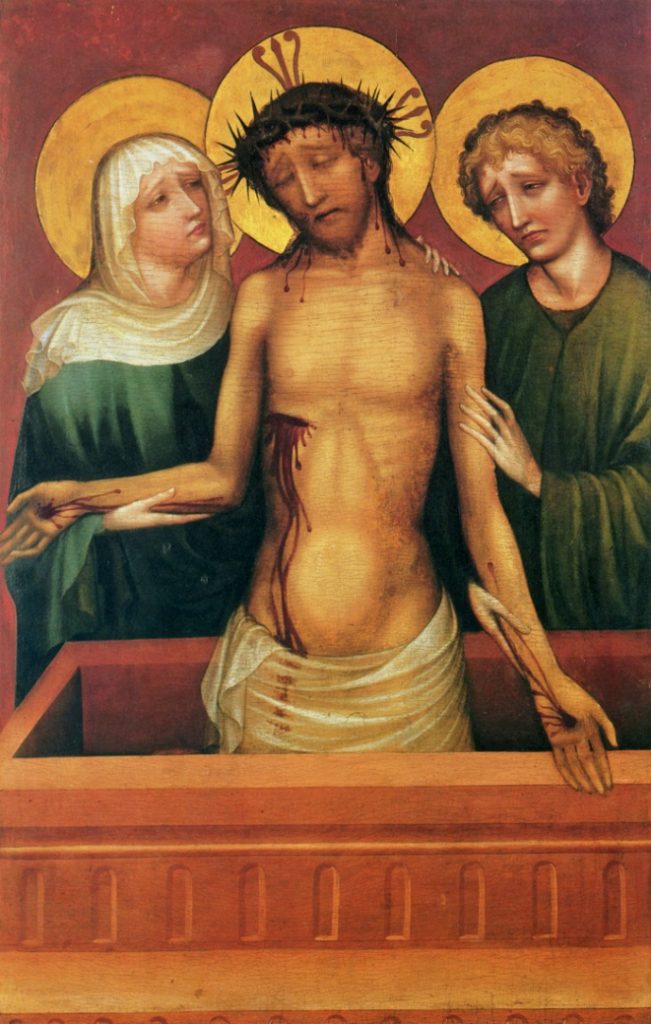

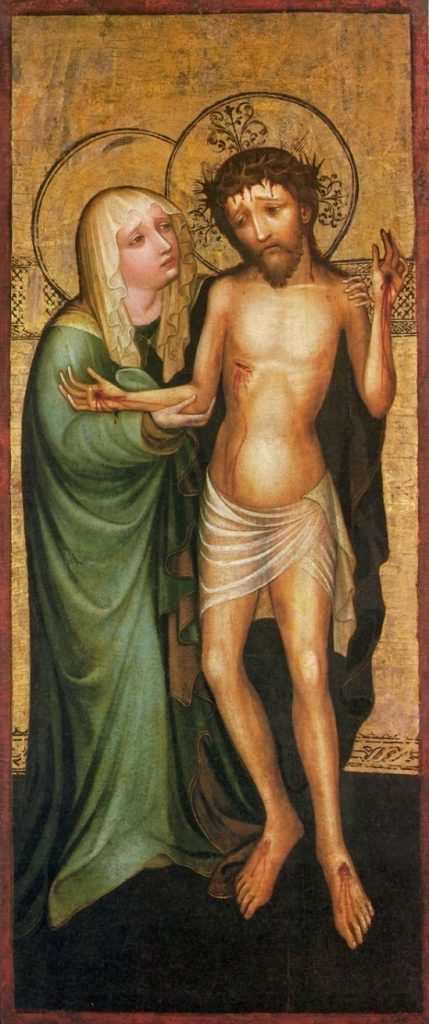

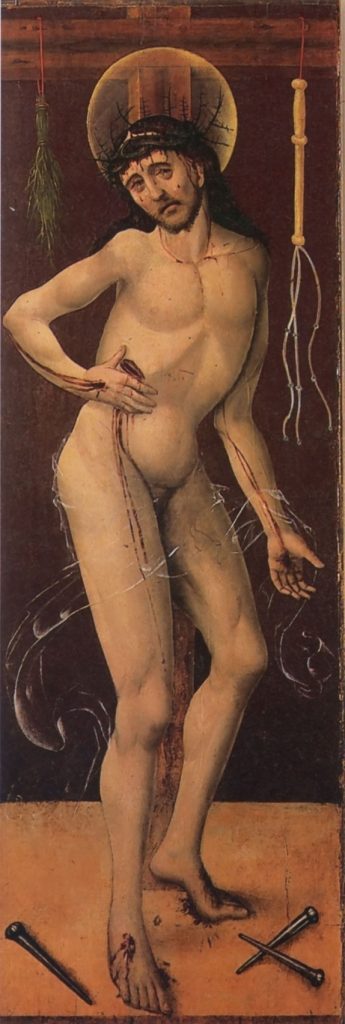

What of that most obvious feature of this painting—Christ’s visible genital anatomy? Ehenheim and the three saints politely avert their gazes toward Christ’s face, as have many of the authors who have written on this work to date. Leo Steinberg demonstrated that images of the infant Christ calling attention to his genitals preponderate around this time, but that pictures of the adult Christ so exposed are almost nonexistent; Richard Trexler has written about the extreme rarity of representations of the crucified Christ that exhibit him completely disrobed and has cited several sources that warned against displaying such representations.[35] To my knowledge no similar work showing the Man of Sorrows exists. To be sure, in several images from ca. 1420, Christ is depicted wearing a semi-opaque or even transparent loincloth but no genitals are visible (Figures 12 and 13). Similarly, in a panel attributed to Jan Polack and dating from around 1500, a few white strokes of paint merely suggest the idea of a loincloth; yet this nude Christ’s penis disappears discretely between his legs (Figure 14). Christ raises his forearms as if intentionally exposing not only the nail prints in his hands but his entire body to von Ehenheim, holding the scourge (and perhaps also the bundle of rods) in the crook of his arm and causing the red robe to hang open from the shoulders, framing his nude anatomy (Figure 15). In many other images, his mantle, the royal robe with which he was clad at the command of Pontius Pilatus—often rendered as the clerical pluvial—wraps decorously around the front of his torso (Figure 16).

Fig. 12. Man of Sorrows Flanked by the Virgin and Saint John, Nuremberg, ca. 1420, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum

Fig. 13. Man of Sorrows with the Virgin, Nuremberg, ca. 1420, Nuremberg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum.

Fig. 14. Attributed to Jan Polack, Man of Sorrows, Munich, 1500, Freising, Diözesanmuseum

Fig. 15. Epitaph for Dr. Johannes von Ehenheim

Fig. 16. Epitaph for Ursula Haller

Skin, Skins, and Skin Color

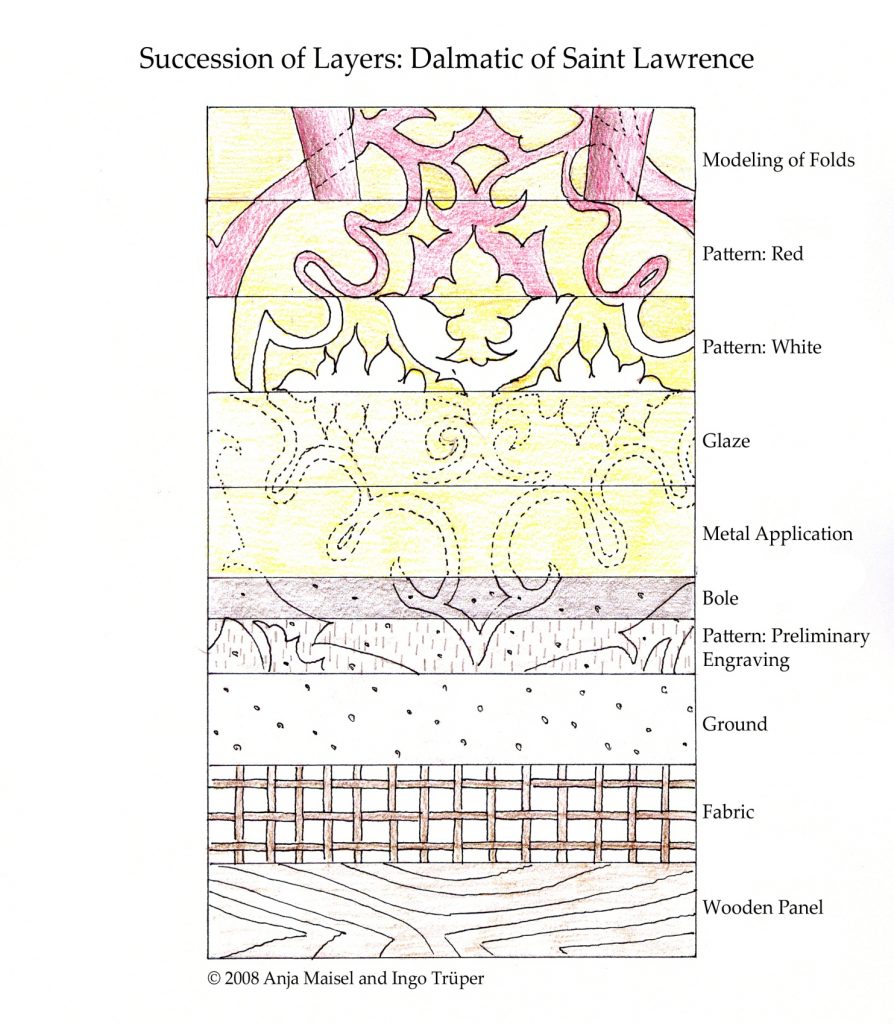

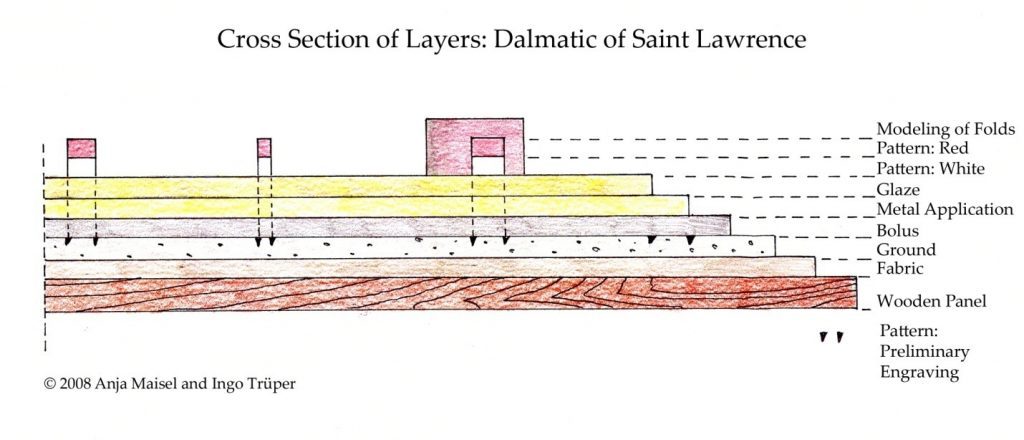

Christ’s nudity stands out in marked contrast to the overabundance of fine textiles and lavish drapery that envelop the other characters. As if in emulation of the end result, the artist(s) performed their crafts as a succession of layered grounds, pigments, and glazes. Diagrams prepared by Anja Maisel and Ingo Trüper during their recent cleaning and examination document eight applications or other processes beginning with the primed surface, all in order to fashion Saint Lawrence’s iridescent dalmatic (Figure 17 and 18). These include engraving the pattern into the ground, five surface applications to achieve the pomegranate pattern, and the final modeling of the drapery folds. Additionally tiny scratches were used to create the affect of nap suggesting velvet.[36] Folds of various contours also convey the sensual qualities of diverse textiles: Lawrence’s stiff collar, which was part of the amice, is ornamented with figures of apostles and prophets embroidered in relief and embellished with pearls of various sizes (Figure 19); the brocade of his dalmatic is so heavy that his fingers disappear into its folds; Cunegond’s filmy flaccid veil, the stiff but light brocade of her gown executed with silver; and Henry’s soft yet heavy fur-lined mantel created with azurite pigment present an array of multifarious fabrics.

Applying the longer lever of postmodern observations, I note that all the coverings of the figures are borrowed. Only Christ is clad in his own native human skin, and at the most basic theological level, Christ is thus showing off his human nature to distinguish it from his divine nature. The saints, by contrast, sport costly silks, velvets, and brocades suggestive of fabrics imported from the near East or derived from Asian prototypes. The fringed straps supporting Christ’s royal robe and the borders at the hemlines of the garments worn by Lawrence and Henry exhibit embroidered pseudo-Kufic script meant to evoke the exoticism of near Eastern cultures.[37] An inventory entry from 1466 describes “an old green velvet chasuble with red and white stripes and with pagan lettering,” indicating that such borders were used on mid-fifteenth-century vestments in the church of St. Lorenz.[38] Ironically although Lawrence’s blonde curls repatriate this third-century Roman saint as a northern European, his dalmatic dazzles with the distant mysteries and bounty of the “Orient.” Both Johannes von Ehenheim and Saint Henry have wrapped themselves in the skins of other species. The gray hooded cape known as an almuce, originally worn during the high Middle Ages to ward off the cold and damp during long hours of choir services, during the later Middle Ages had come to function primarily as a sign of high rank, particularly that of the cathedral or collegiate canon. Although as the natural covering of animals and of the legendary wild folk, fur connoted a lack of culture and civilization and generally a lower baser order, once it was removed and used to clothe the human frame it was conversely perceived as a mark of status–not unlike the colonial commodities taken from the East. Von Ehenheim’s almuce may be of marten or gray squirrel (Figure 20). The brown tails that abundantly ornament it at its lower edge, some of which turn upward as he raises his arms, appear to be of marten. Henry’s borrowed skins include a broad collar and the brown fur lining subtly visible at the edge of the robe and at his waist . Identities are thus reformed using parts and possessions of Others. In the case of other ethnic groups as well as other species, the implicit practices of skinning, dis-mantling and re-appropriating signify control; in their painted representation these hegemonies become part of the larger discursive strategy. Homi Bhabha discusses the notion of mimicry in terms of “the desire for a reformed, recognizable Other, as a subject of a difference that is almost the same, but not quite.”[39] In the appropriations represented in the Ehenheim Epitaph as well as exemplified in the actual vestments of those who originally inhabited the spaces around the epitaph, Bhabha’s notion of mimicry takes a different twist. The displaced and disassociated fragments of the colonized are reordered and both latent anxieties and conscious fears of the Other kept at bay: the pagan lettering is indeed nothing more than nonsensical forms that look like they could mean something threatening, but indeed do not. Thus recontextualized they merely frame and ornament Christian hagiography.

Fig. 17.

Fig. 18.

Fig. 19. Detail: Amice of Saint Lawrence Embroidered with Figures of Saints Peter and Paul, Ehenheim Epitaph (photograph: Volker Schier)

Fig. 20. Detail: Dr. Johannes von Ehenheim in His Epitaph

Fig. 21. Detail: Man of Sorrows in Ehenheim Epitaph

The treatment of human skin and skin color plays an important role in the epitaph. Madeline Caviness’s essay in this volume analyzes the changing colors and contrasting valences of skin color during the Middle Ages. In the Ehenheim Epitaph, Cunegond, in keeping with the contemporary ideals of her gender, exudes the palest of skin tones, followed by the slightly stronger hues of Lawrence, perhaps to connote his youth. Henry is shown as bearded and ruddy, and Christ’s expanses of flesh are exposed as somewhat pallid and sallow, perhaps to suggest the color of death. In her essay, Linda Seidel calls attention to the darker skin tones of Adam’s hands in the Ghent Altarpiece to reference Adam’s work out in the sun, tilling the soil and to signify the import of the labor of the hands. The recent cleaning by Maisel and Trüper has revealed a similar feature in the Ehenheim painting. Most obvious in the v-shaped suntan line high on Christ’s chest (Figure 21) is the artist’s careful effort to render the face, neck, and hands as tanned by the sun, in contrast with the rest of his body. By doing so the artist shows the protective shadow of Christ’s usual clothing and thus here too calls attention to his condition of being disrobed. Christ displays himself deprived of all coatings and coverings including the sumptuous robes of the saintly patrons within the painting, who usurped the coverings of Other peoples and species, the perhaps slightly less ostentatious vestments worn by the priests and choir boys outside of the painting, who inhabited the choir and could look at the epitaph, the warm clothing worn by ordinary men and women on the streets of Nuremberg, and even the tan patina left by the sun on the skin’s surface making it less transparent. Christ is exposed to the gaze of those who look on within the picture and without. It is not the fleeting and controlled moment of the medical examination, the 1970s streaker, or the strip-tease artist. In an epitaph, he is thus exposed for all eternity.

Christ as True Man

Five art historians have addressed the nakedness of Christ in this picture (Figure 24). In 1891, Henry Thode, the first art historian to publish on the painting, observed that Christ was naked and then indulged in surprising judgments:

It is not the saints, who show themselves dignified in their postures as well as appealing in their expressions, but rather the figure of Christ, which locks one’s eyes in a fixed stare. It is hard to imagine how the artist could come to picture Christ so ungainly, so unattractively muscular, an abominable exaggeration of all forms, as if designed after the model of a Herculean roustabout! Unimaginable — because there must have been a specific reason for emphasizing the strongest musculature, as a departure from the conventions employed earlier. Why did he place so much emphasis on bodily strength? Did the artist forget what he was representing while working with an unattractive model whom he used for nude studies? Or is he here making a declaration of an ideal to be found in mightily expansive, full, gigantic forms, in contrast to the slender weak figures in older art?[40]

Thode projected his unease and displeasure on Christ’s bare muscular torso and extremities, which he either found more disconcerting than the exposed penis or more comfortable as a topic of address. Searching for an explanation, Thode first posed a practical answer to the riddle of Christ’s astonishing appearance, an explanation like that of Otto Pächt, discussed in Seidel’s article with respect to Adam’s hands in the Ghent Altarpiece. Were artists of the 1430s so enamored with their powers of verisimilitude that a painter would reproduce aspects of a model’s physique (or rough and reddened hands in the case of van Eyck) for its own sake without thought as to the content of the representation? Thode’s second proposal, looked for causation in the personal predilections of the artist, and in the passage that follows, he supported this thesis using another painting he attributed to the same master.

Carl Gebhardt, writing in 1908, devoted several pages to a detailed and sensitive description of the Ehenheim Epitaph in which he called the plasticity of the musculature “almost frightening” and asserted that the master dared the utmost by painting a loincloth that concealed nothing. In contrast to the body, the head of Christ, according to Gebhardt, expresses nobility. In distinction to other late-medieval images of the Man of Sorrows, the face does not call forth the sympathies of the viewer nor does it sentimentalize or exude self-pity. Extolling the abilities of this painter, whom he identified as Hans Peurl, Gebhardt explained this high achievement with the supposition that he had studied in Venice.[41]

Fig. 22. Epitaph for Canon Johannes Geus, Austria, ca. 1440, Vienna, Diözesanmuseum

In 1958, Alfred Stange followed Gebhardt’s rather positive judgments. In 1980 Charles Sterling continued the discussion in the same vein and referred to the Man of Sorrows in the Ehenheim Epitaph as an “outstanding” figure of Christ. Pointing to a few contemporary examples of a muscular Man of Sorrows including the Epitaph of Canon Johann Geus (Figure 22), Sterling explained the phenomenon by proposing that a wandering artist from Bohemia or Austria had painted the epitaph. In 1993 Strieder agreed with this unusual proposition for attribution.[42]

All five art historians have been fundamentally vexed by this image of Christ. Thode’s overt distaste for a muscular overdetermined virility—calling it “unschön” and Gebhardt’s admission that the physique is “almost frightening” reveal the anxieties that the image could and did generate. Caviness has coined the term viriliphobia to describe the medieval and modern aversion for showing and viewing full-frontal male nudity.[43] These anxieties imbricate and become muddled with those of class. The Ehenheim Man of Sorrows reminded Thode of someone who made a living by his brawn, a roustabout. Gebhardt thought only the face to be “noble.” Indeed throughout most of the history of European art, hypervirile masculinities were viewed as threatening. Animals and satyrs helped to define the boundaries of the human; ethnic Others and peasants inhabited the margins of that which was civilized and therefore framed that which was centrally human; all of the above were displayed as hypervirile.[44]

The Ehenheim Man of Sorrows and the art historical discourses around this figure bring to mind Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s discussions of historical shifts from the ephebic ideals of masculinity reflected and promoted through the youthful androgynous male nudes of neoclassicism to the Herculean or virile ideal of manhood produced and perceived through the fashioning of mature muscular and bourgeois figures, which more often included genital nudity.[45] Indeed the images of the beautifully delicate Man of Sorrows, youthful, slight of build and androgynously represented not showing genitalia, had emerged from the courtly traditions of the end of the fourteenth century, the style associated with the maidenlike schöne Madonna figures, which, although coquettish, showed no anatomy beneath their cascades of lyrical drapery.

In order to cope with the Ehenheim Man of Sorrows, art historians often resorted to re-situating the painting within what was considered a stable system of attribution and geographic classification. If indeed those who five hundred years later spent their lives comparing the various visual conventions for the treatment of the anatomy within specific frames of place and time have been troubled by the representation, we might expect that the initial viewers may have been even more ill at ease.

Conversations Beneath the Painted Surface

Some traces of contemporary considerations in these matters remain under the surface of the painting. Underdrawings visible in reflected digital infrared photograms show that the loincloth was originally planned to sit much higher on Christ’s hips and to drape down over his right knee. It is difficult to ascertain if the cloth was also initially intended to be opaque. Hatch marks indicating modeling on the surface of the abdomen, executed as underdrawings above the original upper limits of the cloth but not below this intended upper edge, may suggest that the cloth was not planned as a transparent veil from the very start (Figures 23 and 24).[46] This would mean that decisions as to how revealing the fabric was to be were made while the work was in progress. The pentimenti may register deliberations of the artist or artist’s workshop or they may reflect conversations with the person or persons who commissioned the work. At least one other uncertainty involving loincloths is similarly documented. Infrared reflectograms of the Crucifixion painted by Hans Pleydenwurf, now in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, indicate that the loincloths of the two malefactors were originally intended to be more revealing.[47]

Fig. 23. Volker Schier, Reflected Infrared Digital Photogram, Detail: Torso of Man of Sorrows, Ehenheim Epitaph © 2008 Volker Schier.

Fig. 24. Detail: Torso of Man of Sorrows, Ehenheim Epitaph (photograph: Volker Schier)

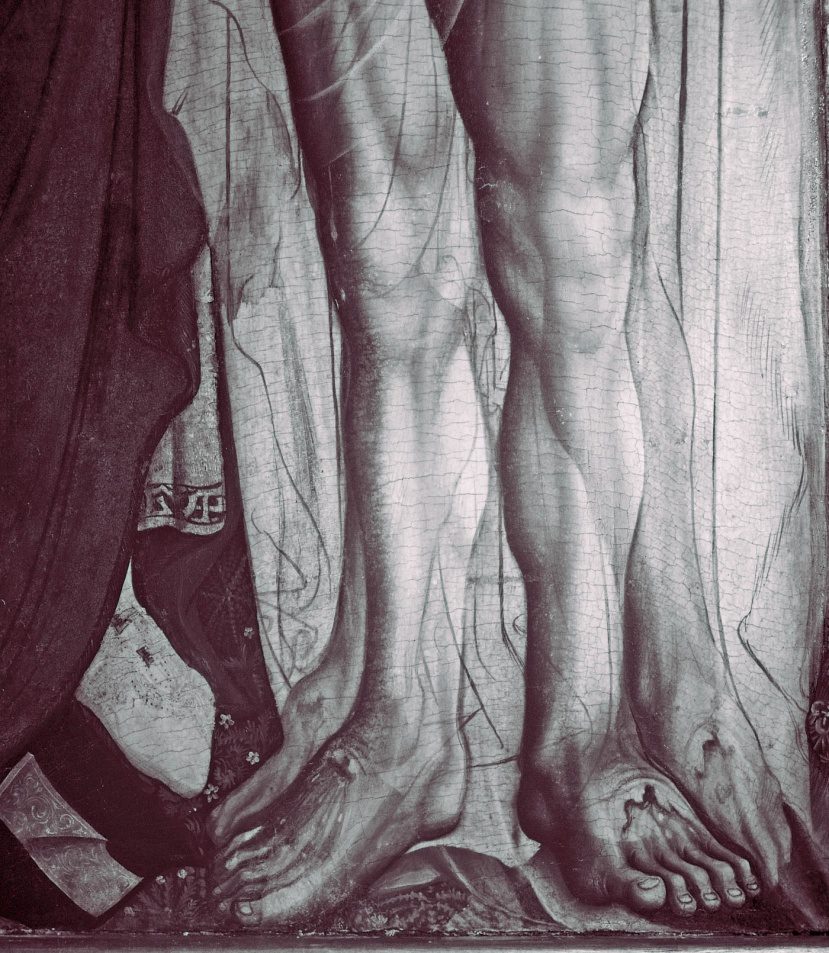

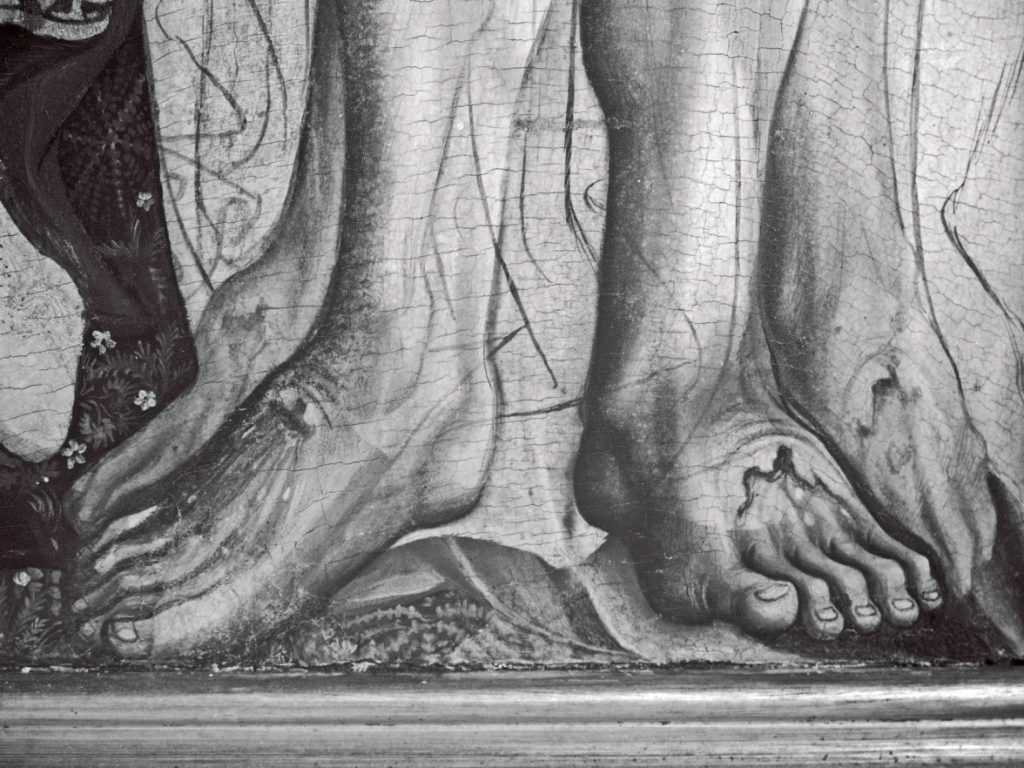

Fig. 25. Volker Schier, Reflected Infrared Digital Photogram, Detail: Legs and Feet of the Man of Sorrows, Ehenheim Epitaph © 2008 Volker Schier

Fig. 26. Volker Schier, Reflected Infrared Digital Photogram, Detail: Feet of the Man of Sorrows, Ehenheim Epitaph © 2008 Volker Schier

Yet another possibly related change from the original concept of the Ehenheim Epitaph is visible in the infrared photograms of Christ’s feet. In the course of the painting process, the feet and legs were moved, the viewing angle was changed, and the mantle lengthened to assure that the Man of Sorrows would appear to float in his own space and not to stand on the ground. He thus does not inhabit the same space as the venerator and the saints (Figures 25, 26, and 27). This change may have resulted from the extreme discomfort and shame arising from an image of individuals in almost obscenely close proximity to the unclothed Christ, or even of his perceived nearness to viewers outside of the image.

Fig. 27. Epitaph for Dr. Johannes von Ehenheim

Gesturing Saints and a Naked Christ in the Choir

What then might be the story or stories behind this strikingly disturbing yet captivating painting, a work carefully planned and meticulously executed to memorialize for all eternity a controversial individual of high standing but in an environment that had not welcomed him? I would speculate that to pay for the epitaph the executors of Ehenheim’s will or the administrators of his estate used his own more-than-ample funds, as was common practice. We cannot know if these relatives or associates, presumably from Bamberg, themselves commissioned the painting or if they left this matter to authorities in Nuremberg. Either way, the work was designed with multiple viewers, beneficiaries, and regulating authorities in mind. The panel had to be negotiated into the context of the choir of this important church under the patronage of the Nuremberg City Council. As was proper, the work had to function as an epitaph. For the soul of the deceased, the painting made present and real the benefaction of not one but three important saints. As advertisers today know all too well, the potential erotic attraction of the nude or seminude body can serve in various ways to draw the interest of potential consumers, whether the product is a bar of soap or a vacation on the beach. Once thus hailed by the image, onlookers could be expected to pray for the salvation of von Ehenheim. To be sure, priests and choir boys could likewise recognize Ehenheim as their pious role model, as their bones and muscles assumed his posture and pose. Future pastors and provosts could smile at the exaggerated representation of the bishop’s authority; visiting bishops could view in the epitaph a confirmation of a harmoniously structured hierarchy; all could be assured that ultimately all power resides in the omnipotent Trinity, here represented in the man Jesus.

Might some too have detected a bit of tongue-in-cheek irony here? Might the (in this context uncommon) gestures and predominant intercession of the Bamberg saints, have been intended as satirical hyperbole pointing to the bishop’s unwelcome intervention in Nuremberg affairs? Was the oral transmission of the story of von Ehenheim’s unwanted appointment through the Bamberg bishop against the wishes of the Nuremberg City Council and his short term in office expected whenever new clerics came to join the collegium and were introduced to the epitaph hanging over their choir stalls? In some respects the competitive struggles in ecclesiastical politics between Bamberg and Nuremberg are maintained in the image – not only reflected but also promoted. The domination of the Bamberg saints, here a metonymy for the bishop of Bamberg, is not uncontested in and through the painting. Von Ehenheim does appear primarily the charge of Henry and Cunegond; they are indeed more central to the image than Lawrence; Cunegond’s brocade gown included the application of silver, a costly material. Yet, as Trüper and Maisel have demonstrated, the greatest amount of time and effort went into the representation of the dalamatic worn by the Nuremberg saint, Lawrence.

How did the image of Christ, breaking all taboos by boldly showing his wounded yet powerfully naked body, figure into the picture for the viewers? Certainly, in addition to the sensationalism of Christ’s genital exposure, the complex orchestration of regimes of touching and looking ultimately focalizes all attention on him.[48] Did his daring depiction belong to the discursive insider anecdotes that were shared within this exclusively male community in this insulated elite space? Did the choir boys point and laugh to hide their embarrassment? Not only is the Christ who looks so approvingly at von Ehenheim strikingly muscular and manly, rather than the conventional feminized, ungendered, or gender ambiguous Man of Sorrows of the early-fifteenth-century, but the side wound caused by the pierce of the lance is barely visible. As it disappears into the shadowy recesses at the outer contours of Christ’s body, it does not beckon as the gaping vaginal orifice that invited spiritual fantasies of penetration on the part of the devotee. The discursive pentimenti preserved as underdrawings and the trouble that this Christ has created for art historians demonstrate the validity of the claims that the Middle Ages produced a gender inverted Christ, whether in the form of Jesus as Mother or a more sexualized body of Christ as the bride of Christ.[49] The shock of the Ehenheim Man of Sorrows is the inversion of the inversion. Different and unfamiliar positionings within the sexual/spiritual/political economy are thus facilitated. The inclusion of exemplary behavior within the picture taught proper viewing – looking away; but in order to accomplish this goal the figure also enabled a rather indecorous ocular transgression, the improper gazing at Christ’s penis during the many hours when the offices were chanted in the choir and Masses were sung before the high altar. The “meshes of possibilities” thus opened could include desire and envy.[50] This privileged viewing was the purview of an elite group of male viewers, clerics and young potential clerics from the St. Lorenz School, making it likewise a site/sight for homosocial bonding.[51] Saint Cunegond who anoints von Ehenheim and intercedes on his behalf may be represented in viewing proximity of the exposed Man of Sorrows, but had she lived in 1438 she would not have been privy to this picture hanging inside the choir of St. Lorenz.

Corine Schleif is professor of (medieval and Renaissance) art at Arizona State University. The author of over fifty publications including Donatio et memoria (1990), Schleif has focused her research on art as donation, art historiography, and art in multisensory contexts. Consistently she foregrounds issues of gender and class. Current projects include: Katerina’s Windows: Donation and Devotion, Art and Music as Heard and Seen by a Birgittine Nun, co-authored with Volker Schier (in press) and the multimedia manuscript study Opening the Geese Book.

References

| ↑1 | Madeline H. Caviness, “The Feminist Project: Pressuring the Medieval Object,” Frauen Kunst Wissenschaft 24 (1997): 13-21; Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 30-34; Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries http://nils.lib.tufts.edu/Caviness.html, Introduction http://nils.lib.tufts.edu/Caviness/introduction.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Heinrich Wölfflin, Kunsthistorische Grundbegriffe:Das Problem der Stilentwickelung in der neueren Kunst (Munich: Bruckmann, 1915); trans. by M. D. Hottinger as Principles of Art History (New York: Dover, 1932 and reprints). |

| ↑3 | Erwin Panofsky, “Iconography and Iconology: An Introduction to the Study of Renaissance Art” in Meaning in the Visual Arts (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1955). |

| ↑4 | Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson, “Semiotics and Art History,” Art Bulletin 73 (1991): 174-208. https://doi.org/10.2307/3045790 |

| ↑5 | Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form trans. Christopher Woods (New York: Zone Books, 1991), first published as an article in German in 1927. |

| ↑6 | Erwin Panofsky, Gothic Art and Scholasticism (New York: Meridian Press, 1957). |

| ↑7 | Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth Century Italy (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972) and The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1980). For an analysis of Baxandall’s notion of the “period eye” and its intersection with various directions of theory see Allan Langdale, “Aspects of the Critical Reception and Intellectual History of Baxandall’s Concept of the Period Eye,” About Michael Baxandall, ed. Adrian Rifkin (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), 17-36. |

| ↑8 | Ernst Gombrich, Ideal and Idols (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1979); Die Krise der Kulturgeschichte (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1983) 34. He first articulated these ideas in the essay In Search of Cultural History (London: Oxford University Press, 1969). |

| ↑9 | Carolyn Porter, “Are We Being Historical Yet?” South Atlantic Quarterly, 87 (1988): 743-86. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-87-4-743 |

| ↑10 | See for example Stephen Greenblatt, Renaissance Self-Fashioning. From More to Shakespeare (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005), first published in 1980. |

| ↑11 | Theophilus On Divers Arts, trans. by J. Hawthorne and C. S. Smith (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963; reprint New York: Dover, 1979); Cennino d’Andrea Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook: Il Libro dell’Arte, trans. Daniel Thompson, Jr. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1932-33; reprint, New York: Dover, 1960); full text also available on the internet: http://www.noteaccess.com/Texts/Cennini/1.htm |

| ↑12 | I am thinking of, for example, Erwin Panofsky’s Abbot Suger on the Abbey Church of St-Denis and Its Art Treasures with its Latin edition and English translation on facing pages, first published in 1946 and still in print in the second edition by Gerda Panofsky-Soergel (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979), cited by Anne Harris in this volume. Another more recent book known to students of the northern Renaissance is Michael Baxandall’s Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980) with its German passages followed by English translations. |

| ↑13 | Caecilia Davis-Weyer, Early Medieval Art 300-1150, Sources and Documents (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1971, reprint, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987); Teresa Frisch, Gothic Art 1140 – ca. 1450 (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1971; reprint, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986); Cyril Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1425, Sources and Documents (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1972; reprint, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986); Elizabeth Gilmore Holt, A Documentary History of Art: Volume 1, The Middle Ages and the Renaissance (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982). |

| ↑14 | Illene Forsyth, The Throne of Wisdom: Wood Sculptures of the Madonna in Romanesque France, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972. |

| ↑15 | Pamela Sheingorn, The Book of Sainte Foy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995); Kathleen Ashley and Pamela Sheingorn, Writing Faith (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). https://doi.org/10.9783/9780812200522 |

| ↑16 | Madeline Caviness, Sumptuous Arts at the Royal Abbeys in Reims and Braine: Ornatus elegantiae, varietate stupendes (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990); Linda Seidel, Legends in Limestone: Lazarus, Gislebertus, and the Cathedral of Autun (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999). |

| ↑17 | Clifford Geertz, “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture,” in his collection of essays, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 2006), 3-30. |

| ↑18 | Originally used in a historiographic context by Leopold von Ranke in his Geschichten der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1535, vol. 1 (Leipzig and Berlin: Reimer, 1824), vi. |