Virginia Blanton • University of Missouri – Kansas City

Jack Walton • University of Missouri – Kansas City

Recommended citation: Virginia Blanton and Jack Walton, “St. Didier’s Flowering Verge and the Rhetoric of Chaste Virility in a Modern Devotional: Joseph Royer’s Homage to Medieval Langres,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/PMAL4500.

A recent gift to the Spencer Art Reference Library in Kansas City, Missouri, is an illuminated manuscript containing the life of St. Didier (Desiderius), Bishop of Langres. Reminiscent of books of hours with elaborate borders illustrating flowers and insects, this book also contains a pictorial cycle of the saint’s life and martyrdom. Yet, this tiny devotional book was produced in 1902.[1] Purchased by Lewis Gould in memory of his wife, the book augments a group of manuscript leaves in the Nelson-Atkins Museum Library, a teaching collection amassed by the medievalist and art historian, Karen Gould (1946–2012). As an artifact, this book contributes evocatively to the nineteenth-century vogue for medieval-style book arts; as a representation of medievalism, this manuscript encodes meanings about masculine sanctity perfected in medieval Christian devotionals.[2] But, the book is far more provocative in that it stages the city of Langres as an important cultural landscape in Christian history. Designed and executed by the Langrois antiquarian and bibliophile, Joseph Royer (1850–1941), the manuscript demonstrates the artist’s investment in preserving the life of a local bishop who sacrifices himself to protect Langres from marauding Vandals. In effect, Royer’s text operates as a homage to this ancient, walled city, which sits on a limestone promontory originally inhabited by the Lingones tribe.[3] Styled as a ploughman turned bishop, Didier is an uncommon overlord, but his efforts and ultimate failure to preserve Langres are masked by Royer’s visual rhetoric of a fortified town that never succumbs: Didier is martyred but outside the city’s intact walls. Drawing on masculinity studies—which Rachel Dressler has so usefully invoked to discuss medieval tomb sculpture and the virility of knights’ effigies—we argue that the depiction of the town demonstrates Royer’s desire to rewrite the history of Langres as a sanctified communal space bounded by the virility of its patron saint.[4]

Our study takes up the likely medieval sources, both textual and visual, of Royer’s book to discuss its multivalent images of masculinity.[5] We contend that Royer’s manuscript operates not only as an honorific for the town of Langres, where Royer was raised, but also as a totem of personal devotion to his community. Born into a family dedicated to preserving the antiquities of Langres, Royer used his talents as a painter and bookmaker to contribute to these familial commitments. Royer’s book is not simply a celebration of the saint who defended the town; it is a demonstration of God’s love for Langres. The vie’s language affords God ultimate power over the city, even allowing the town to be vandalized and its bishop martyred. Like many other male saints who ineffectively resist, Didier cannot forestall the Vandals; he cannot save his town, his people, or himself. In this provincial narrative, Didier is but a metonym for the defeated town, reborn.[6] The sacking of the city and the beheading of its bishop operate as elements that reveal God’s agency and the eternal reward for those who imitate Christ’s suffering: the city and the bishop are re-energized as masculine subjects of strength and vitality. The narrative of Didier, then, is representative of God’s intervention in human affairs, as Didier rises from his martyrdom and carries his head back into his city.

Manuscript Description & Provenance

Now in the Spencer Library collection at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, the manuscript, which we will refer to as the Royer Didier, is identified by shelf mark KGC51. The petite book features twenty-one parchment leaves, measuring 136 x 115 mm, mounted on paper guards, with modern end papers. The leaves are gilded at the fore-edge, head, and tail to complement the gilt-tooling on the binding, which is red morocco over pasteboards with watered silk inserts in navy blue. There is no ex-libris or signs of ownership.[7] A bookmark made from a gold and red striped ribbon embellishes the volume. Two tiny metal eye clasps, adorned with a perforated quatrefoil on each hasp, enhance the finished book. The design of the binding is simple but elegant, reflecting French tastes at the turn of the century.[8]

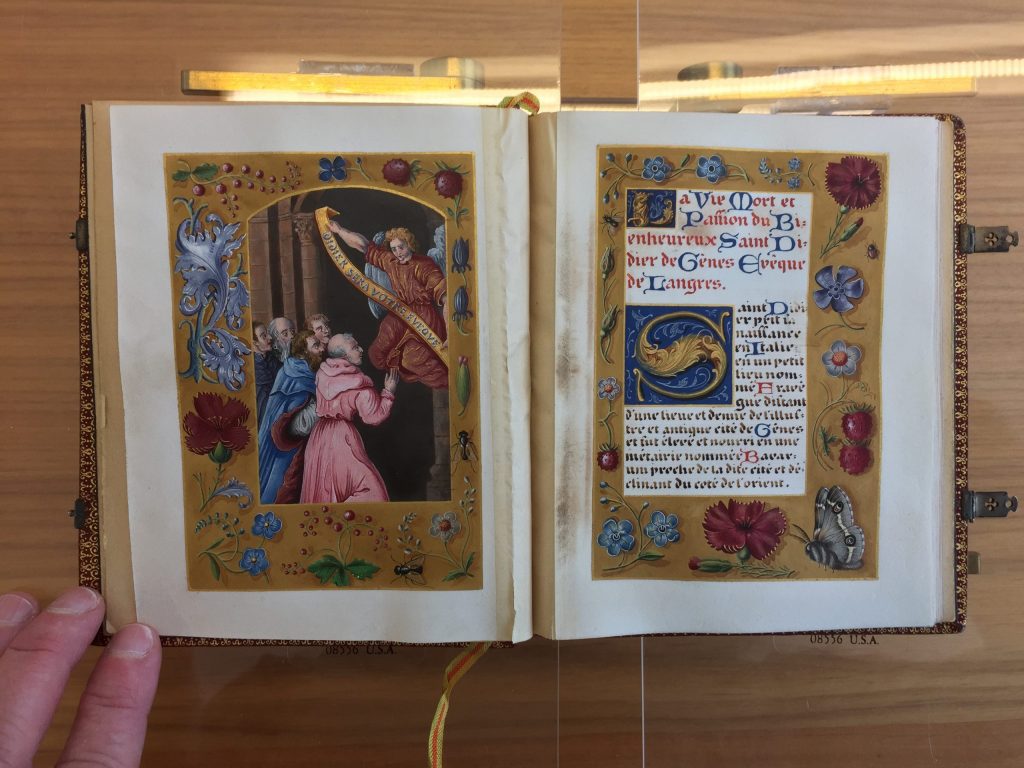

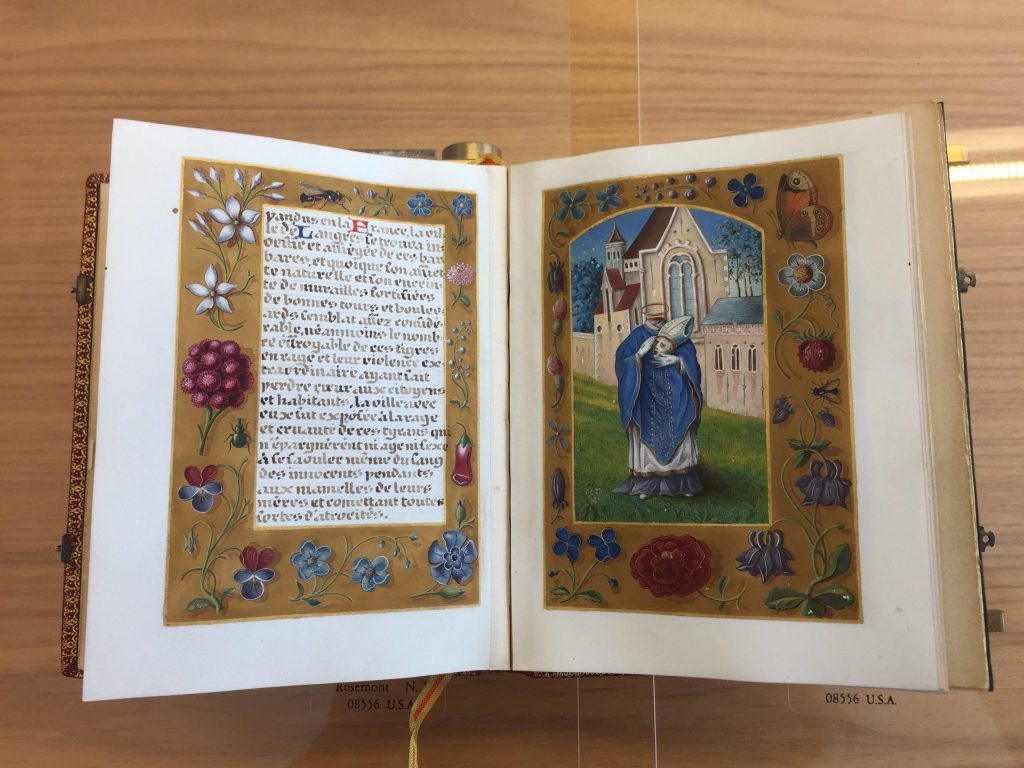

Figure 1. Opening of the Royer Didier, fols. 1v–2r. Life of Saint Didier, Gothic Revival Manuscript, 1902. Karen Gould Collection #51, Gift of Lewis Gould. Spencer Art Reference Library, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo: Virginia Blanton.

The manuscript contains only one text, a life of Didier of Langres in French. The text block, copied in a modern calligraphic script—a type of modified textualis—is presented in a single column, twenty-two lines per folio, in brown ink. Royer takes advantage of all available space in the text block, which means there are many hyphenated words. Unlike medieval practice, it is clear that the text was copied after the decoration, as lettering occasionally carries over onto the borders. The pristine parchment leaves, which were treated with lead white, contain no marginalia or usage marks. The end papers and paper guards show some yellowing or darkening from the lead white reacting with sulfur in the wood pulp.[9]

Each folio of the Royer Didier is decorated with a full-page, rectangular border in the trompe l’oeil style of late medieval Bruges-Ghent workshops. The paint is luminous—perhaps because of the lead white underlay—and the vivid colors engage the viewer with their vitality. Minute brushstrokes show exquisite details, such as the ribbing of flower petals, the delicate wings of flies, and individual blades of grass, demonstrating Royer’s fine, artistic skill. The decorated borders (probably from shell gold) are ornamented with flowers, fruits, insects, and acanthus leaves, reminiscent of the Hastings Hours, a late fifteenth-century book of hours (London, British Library, Additional MS 54782). Decorative multi-line initials, formed with acanthus leaves that are alternately gold on a navy blue background or navy blue on a robin’s egg blue background, demarcate twenty-two distinct sections of the life.[10] Each sentence of the prose life is marked out by alternating red and blue one-line initials, as are the personal names. Direct speech, which is minimal, is copied in red, and the book opens with a title in red, with blue capitals and a two-line decorated initial: “La Vie Mort et Passion du Bienheureux Saint Didier de Gênes Evêque de Langres.” Decorative borders are also employed on the five folia with full-page, arched miniatures. These miniatures constitute a pictorial cycle: fol. 1v depicts an angel with a scroll announcing that Didier will be their new bishop (Figure 1); fol. 5r shows Didier as a smiling ploughman whose oxen refuse to move (Figure 2);

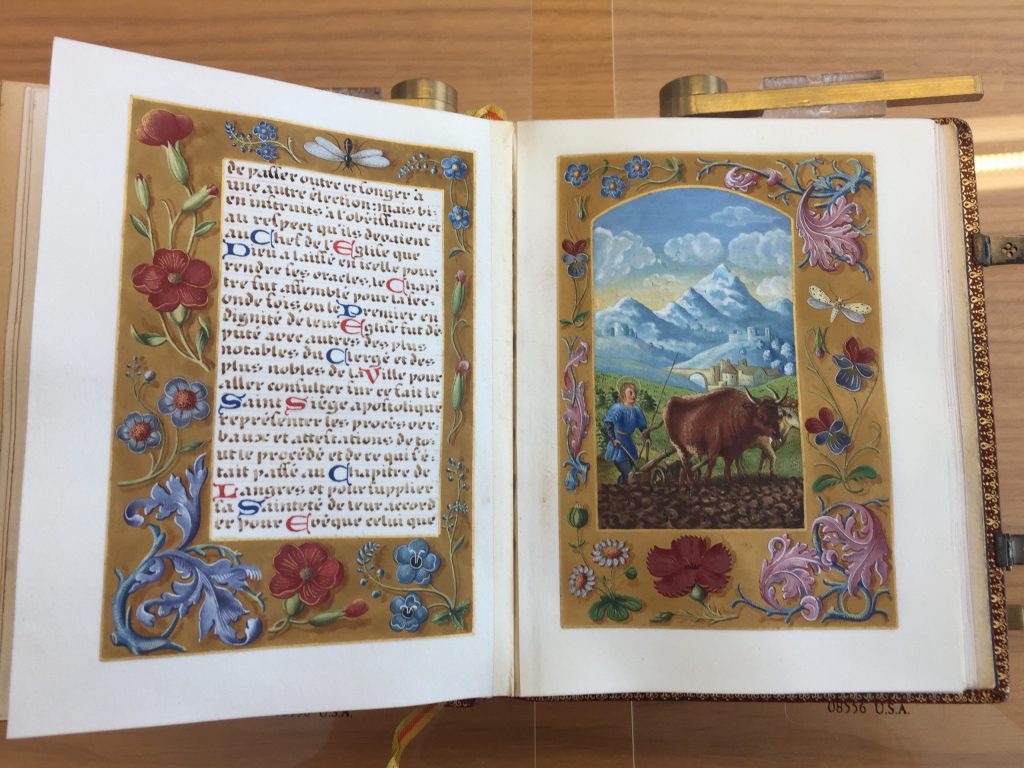

Figure 2. Didier with oxen as ploughman, fols. 4v–5r. Life of Saint Didier, Gothic Revival Manuscript, 1902. Karen Gould Collection #51, Gift of Lewis Gould. Spencer Art Reference Library, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo: Virginia Blanton.

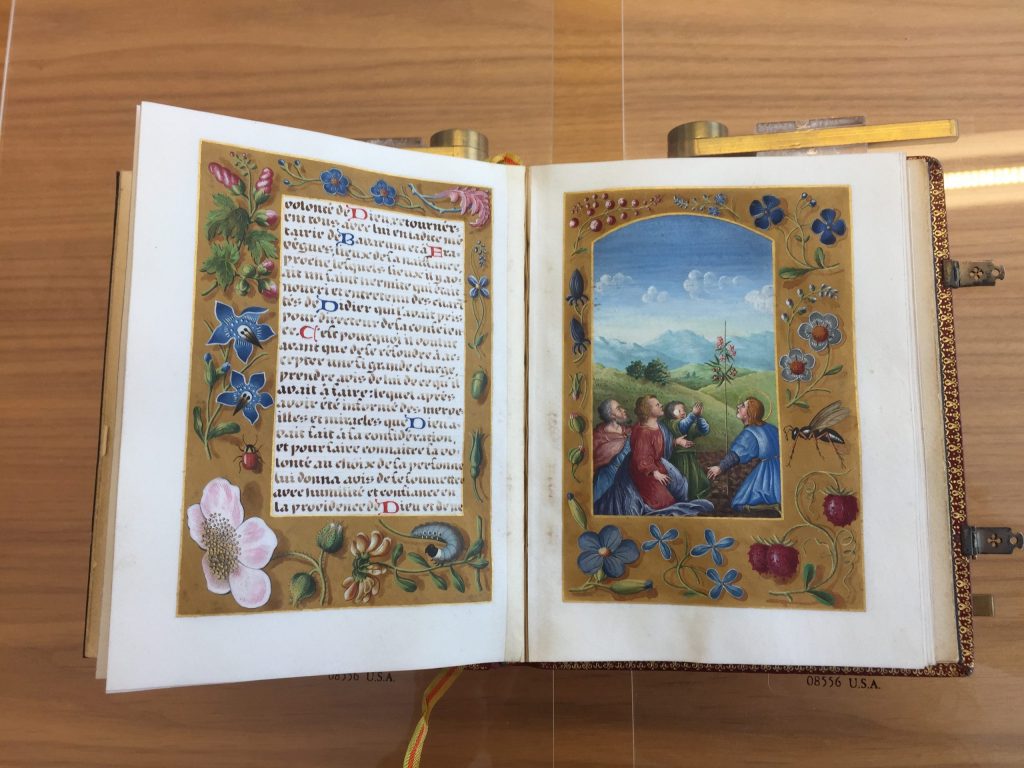

fol. 10r illustrates the miracle of the ploughman’s flowering rod or verge (Figure 3);

Figure 3. Miracle of Didier’s flowering rod, fols. 9v–10r. Life of Saint Didier, Gothic Revival Manuscript, 1902. Karen Gould Collection #51, Gift of Lewis Gould. Spencer Art Reference Library, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo: Virginia Blanton.

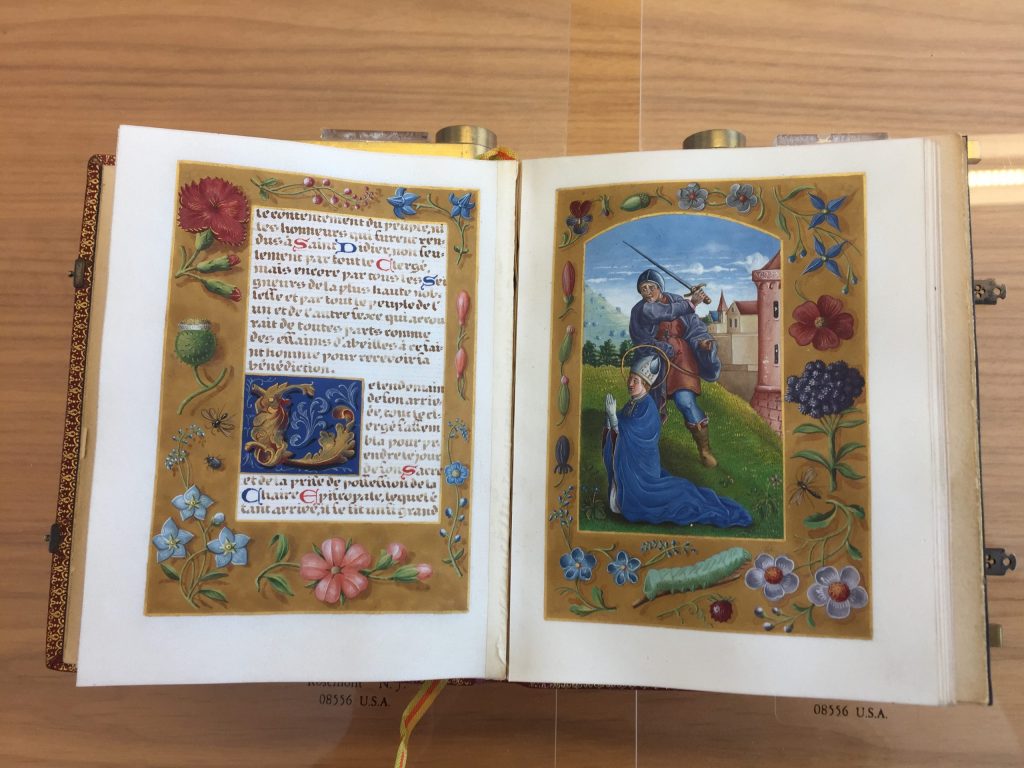

fol. 13r portrays Didier’s execution (Figure 4);

Figure 4. Execution of Bishop Didier of Langres, fols. 12v–13r. Life of Saint Didier, Gothic Revival Manuscript, 1902. Karen Gould Collection #51, Gift of Lewis Gould. Spencer Art Reference Library, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo: Virginia Blanton.

and fol. 17r presents the decapitated bishop holding his head in his hands (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Bishop Didier of Langres, decapitated, holding head in hands, fols. 16v–17r. Life of Saint Didier, Gothic Revival Manuscript, 1902. Karen Gould Collection #51, Gift of Lewis Gould. Spencer Art Reference Library, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo: Virginia Blanton.

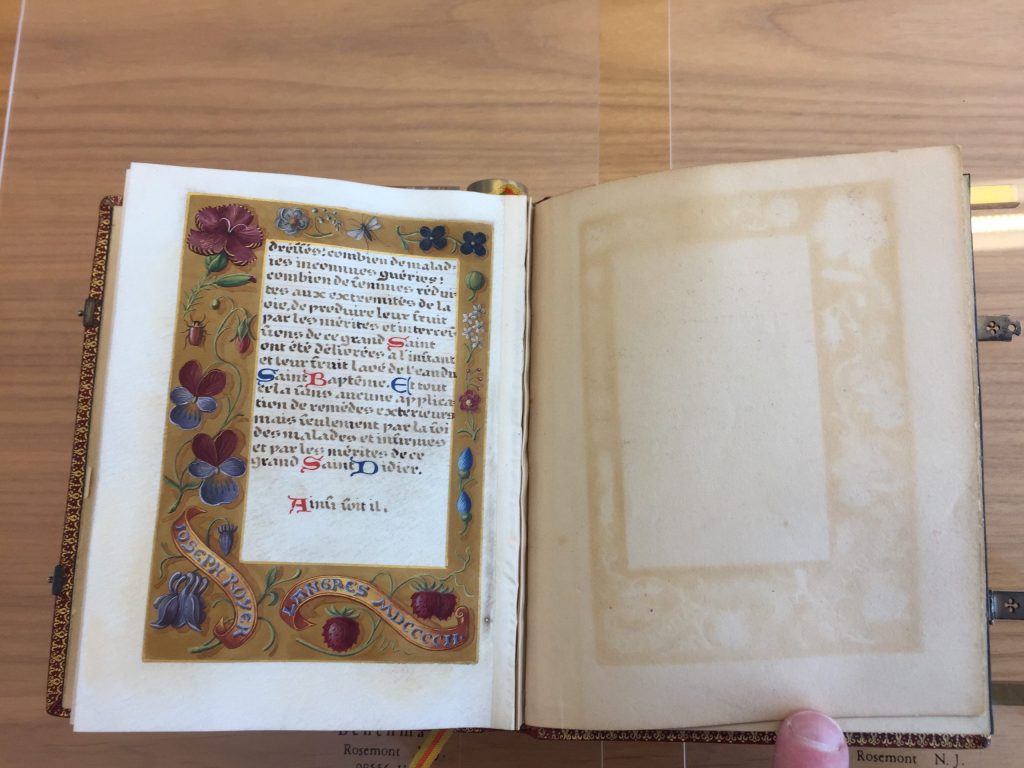

The final folio features two scrolls in the lower border with the name “Joseph Royer” and “Langres MDCCCCII” (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Ending of the Royer Didier, with scroll featuring artist’s name, city, and date: Joseph Royer, Langres MDCCCCII, fol. 21v. Life of Saint Didier, Gothic Revival Manuscript, 1902. Karen Gould Collection #51, Gift of Lewis Gould. Spencer Art Reference Library, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Photo: Virginia Blanton.

Joseph Royer, who was a noted collector of medieval manuscripts and incunables, was no doubt the illustrator and scribe of the Didier, as he is known to have copied and decorated another book using medieval book arts, the Passio Domini Nostri Jesu Christi (1908), which is Manuscript 179 in the Bibliothèque de la Société Historique et Archéologique de Langres (SHAL), Musée d’Art et d’Histoire in Langres. Like the Didier, the Passio Domini has a pictorial programme with four, illuminated miniatures and is signed and dated by the artist. The Passio Domini was gifted to SHAL in 1941, along with three other illuminated books Royer made; a compendium of genealogies of notable Langrois families (also hand made by Royer); and a collection of manuscripts with Langres associations (such as an antiphoner and a gradual from the Cathedral of Langres).[11] Among Royer’s medieval manuscripts were four, fifteenth-century books of hours (three of the Use of Langres), which no doubt influenced Royer’s production of the Didier and the Passio Domini, but only Manuscript 166 has the distinctive Bruges-Ghent look of the Didier, with gold borders featuring leaves and fruit. The far less polished decoration and miniatures in Manuscript 166 do not, however, approximate the delicate artistry of Royer’s modern book.

Royer’s training as a painter is not documented, but his brother Charles (1848–1920) studied in Paris with Jean-Jacques Henner for a time.[12] The two brothers were naturalists, collectors, amateur archeologists, and successive conservators of the Musée de Langres.[13] Their father, Nicholas (1798/9–1877?), was justice of the peace in Langres, and both sons studied the law briefly before giving it up to pursue their hobbies. Joseph Royer’s work as a naturalist is evident in two books he made on flora and lepidoptera, and the collection of 500 birds, 2,000 moths and butterflies, and 26,000 beetles he donated to the museum indicate his enthusiasm for the natural world, a passion attested in the border decoration of the Didier, which features such startlingly beautiful depictions of insects. Significantly, a death notice published by SHAL lauds Joseph as a “copiste de manuscrits et sur fond d’or, avec la patience et le talent d’un moine, des enluminures dignes des plus beaux moments de le moyen Âge” [copyist of manuscripts and with the patience and talent of a monk, illuminations on a gold background worthy of the most beautiful moments of the Middle Ages].[14]

The Rhetoric of Chaste Virility

The life of Didier recounts the elevation of a Genoan farmer to the episcopal see of Langres, a change of status effected through God’s intervention. This uneducated, simple man humbly resists an angel’s decree that he is to be bishop of Langres. Didier is only convinced when his staff miraculously flowers and produces fruit. After a night of prayer and reflection, God gives Didier the ability to preach and bring penitents to the faith. His investiture as bishop, which has variously been assigned to dates in the second, third, and fourth centuries, occurs when angels deliver episcopal vestments.[15] Didier’s efficacy as a humble servant leader contrasts with a violent attack by Germanic Vandals who denounce Christianity and the bishop’s authority. In an effort to preserve Langres, Didier attempts to parley with the Vandal leader, Chrocus, who holds him in disdain and orders Didier’s execution.[16] Beheaded by a soldier named Godifer, Didier does not immediately die. His corpse retrieves his head, re-enters the town, and inters itself in a tomb. An important miracle augments the moment of martyrdom: the executioner’s sword pierces the gospel book in the bishop’s hands, and the martyr’s blood soaks its leaves, yet the words of the Gospel remain legible. Years later, Didier’s body is found uncorrupted as another sign of his sanctity.

This narrative of an acephalous saint derives from a complicated tradition of vitae Desiderii, though it remains unclear if Royer were simply copying from a late nineteenth-century exemplar or if he shaped the vie himself from several sources. As noted above, his version is divided into twenty-two discrete sections, which has helped us determine how three key texts were used: 1. the earliest known narrative about Didier is Varnahaire’s Vita Sancti Desiderii (c. 615); 2. the earliest text in French is Guillaume Flamang’s (or Flamant’s) La vie et passion de monseigneur sainct Didier (1482); and 3. Agostino Calcagnino’s Le Sacre Palme Genouesi (1655) is a noteworthy, post-medieval Italian version.[17] A short summary of each illustrates their importance in the shaping of Royer’s vie. Varnahaire’s vita is a straightforward narrative of martyrdom: it opens with the Vandal invasion and a description of Didier’s verbal defense from atop the city walls.[18] It proceeds to relate Didier’s execution before describing the deaths of Godifer and Chrocus.[19] Written by a canon of Langres in Latin prose, this brief account lacks all but four of the twenty-two sections in Royer’s vie, though it does include the posthumous miracle of the gospel book’s legibility.[20]

Flamang’s verse play is far more complex.[21] Like Varnahaire, Flamang was a canon of Langres Cathedral, but seems to have been from Flanders. His play, composed in French using the rhyme scheme of a ballade, is an ensemble production that includes the canons and citizens of Langres; a heavenly host including God, the Virgin Mary, and various archangels; the Holy Roman Emperor and the Bishop of Dijon as arbiters of the state; and a cast of devils who inspire Chrocus to sack Langres. The play, which contains three acts, is impressively long. Part one details the birth and youth of Didier in Fravega, near Genoa, and Didier’s abiding virtues as a rustic; his discovery by the Langrois delegation; his resistance to being called to serve; and the miracle of his flowering verge as evidence of God’s benefaction. Part two provides the main conflict between Didier and Chrocus in which the Vandal violence is framed as an attack on Christianity. The action focuses on Didier’s leadership, his encouragement of the faithful and of the Langrois military. When the city is overrun, Vandals seize Didier at prayer in church and take him outside the walls to be executed. Part three focuses on the 1315 translation of Didier’s relics, conducted by Guillaume de Durfort, Bishop of Langres.[22] Significantly, the majority of the elements that appear in Royer’s vie, including Didier’s life as a ploughman and his role as reluctant bishop, are included in the French play. An edition published in 1855 might well have served as an important source for the current vie, yet several details differ, such as the mechanism by which the Langrois learn about Didier and an extended conversation between Didier and a hermit advisor, indicating that Royer’s text did not derive solely from this source.[23] Some of these elements appear in Agostino Calcagnino’s Le Sacre Palme Genouesi, along with the Langrois deputies’ audience with the pope and the miracle of the angelic investiture.[24] This source also demonstrates the kind of wordplay between “Desiderio,” Didier’s Italian name, and “desiderato,” the Italian word for “desired” that is observed in Royer’s vie.[25]

As this review indicates, Royer’s vie is indebted to elements in the French and Italian traditions, as well as details found in Varnahaire’s Latin vita. Common to all three, however, are images of virility and fertility: the young ploughman who tills the soil; the rod that flowers and produces fruit; the decapitation of Didier—which has long been a metaphor for castration—and the spilling of blood; the town penetrated and sacked by marauders; and Didier’s posthumous interventions in helping pregnant women deliver healthy children.[26] As we note above, God’s will is effected by angels, and Royer focuses his first miniature on an angelic visitation. As the canons discuss an election in the chapter house, with interested laymen (but no women) present, an angel appears to announce that “Didier sera votre Évêque” [Didier will be your bishop]. Presented vividly on a scroll (Figure 1), Didier’s name is announced to the assembly, who gaze up in astonishment. In the foreground, with the laity standing behind him, a tonsured canon in a rose tunic, scapular, and hood raises his hand towards the red-robed angel, receiving his message. The angel is gendered male and his short sleeves reveal muscular forearms. The image (like the text) does not indicate that Didier is from Genoa. Where in some stories, the angel also identifies Genoa as Didier’s home, the Royer vie offers no hints by which the Langrois can locate their next bishop. So, a delegation journeys to Rome to seek papal advice. Reassured by the pope that God will reveal all, the delegates head north towards home. Like the Israelites seeking the promised land through the wilderness, the Langrois must wander and search until God delivers their high priest. Near Genoa, they see a ploughman, Didier, whose oxen have stopped, and overhear him exhorting the beasts.

Royer’s second miniature presents this scene with Didier driving a team of oxen in the foreground, with the walled city of Genoa in the distance situated before the Apennine mountain range (Figure 2). The Ponte Vecchio, which is the entrance to the Sturla Valley where Didier farms, is a central feature of the landscape. Didier himself is presented as a youth whose golden ringlets and clear, white complexion suggest nothing of a laborer. He is dressed in dark blue tights and undershirt with a royal blue tunic with half sleeves, cinched by a gold belt.[27] The effect of the tunic’s shortened sleeves emphasizes Didier’s shoulders and arms. Where one might expect a laborer’s forearms to be uncovered, here they are hidden and differ markedly from the angel’s naked forearms. The cinched waistline, which symbolizes chastity in medieval monastic dress, shows that Didier is trim, but the narrow waistline also enhances broad shoulders and muscular thighs. As he strides forward, Didier’s strength is evident. The stature of the ox complements Didier’s posture. Commanding attention, the ox is immense, taking up the majority of the foreground. The musculature of the brown bullock’s shoulders contrasts with its trim flanks. Drawing attention to the bullock’s stomach, a light brush stroke highlights the sheath, directing attention to the hidden penis. An ox, of course, is a bull castrated after it reaches sexual maturity so that it will be a powerful but docile draft animal. The representation here accentuates the masculine power of the ox, but also its sexual limitation: without testicles, the ox is not fertile. The focus here seems to highlight the chastity of the ox, and by extension, the chastity of the powerful, young man who drives the team.[28]

Through God’s interference, Didier’s oxen refuse to move and not even a stroke from his verge affects them.[29] The ploughman shouts “par la tête de Didier vous marcherez et avancerez!” [by the head of Didier, march and advance]. This exclamation—which prefigures his decapitation and the precise relic by which the devoted will swear in his name—alerts the delegation to Didier’s identity, and they explain their mission. Didier is astonished by their assertion about his new role, and demurs, insisting that “Quand cette verge aura produit des feuilles des fleurs et des fruits ce sera pour lors que je ferai votre Évêque” [When this rod has produced leaves, flowers, and fruits, that will be the time that I will be your bishop] (fol. 9r). Immediately “cet aiguillon, cette verge s’épandit et fut chargée de fleurs, de feuilles et de fruits aussi bien que celle d’Aaron qui avait été choisi de Dieu pour être le grand prêtre de la loi ancienne” [this goad, this rod spread out and was loaded with flowers, leaves, and fruits, much as Aaron’s who was chosen by God to be the high priest of ancient law] (fol. 9r). The reference to Aaron’s authority makes explicit Didier’s status as God’s chosen, even as the rod becomes the sign of the ploughman’s episcopal position. The miracle of the flowering verge alludes directly to the Biblical story in which God appoints Aaron the leader of the Levites (Numbers 17.5–8).[30] As an indication of his preference, God makes Aaron’s staff, a sign of his priestly authority, flower and produce almonds.[31] The third miniature in the Royer Didier depicts the flowering verge (Figure 3). The five-petaled, white or light pink flowers with long yellow stamens of the prunus dulcis are similar to wild roses, while the fruit, an oblong drupe, ripens in clusters. Because the flowers, lanceolate leaves, and drupes grow on spurs or lateral branches of the almond tree, the fruit has the appearance of testicles on a long narrow branch. Royer places three Langrois on the left with Didier on the right. The young boy in a green robe, positioned at center, smiles with joy and raises his hands in supplication.[32] All have dropped to their knees, gazing up in astonishment. The up-raised hands with palms forward indicate the adults are startled. Even Didier is slack-jawed, aghast at the flowering rod, which is planted in front of his body and between his knees. The lateral branches on the rod, adorned with flowers and fruit, very much approximate those of a flowering almond tree, and the round, brown hulls on the narrow rod reproduce male genitalia. The visual association of the verge with genitalia is no accident. The vie’s language is modest, yet a consideration of the multiple meanings and connotations of the term reveals explicit sexual innuendo. While this study translates verge as “rod,” another primary sense is “penis.”[33] The use of the word virga for male anatomy dates back to classical Latin where the term means “root,” “staff,” “twig,” and “male member.”[34] These senses are well known to native speakers of Romance languages, making the imagery of the flowering rod one of male reproduction. The etymology of verge seems entirely in keeping, therefore, with the presentation of many plants in the border art featuring round balls on a stick.[35] The use of various pollinators in the margins—bees, butterflies, moths, and dragonflies—provides, moreover, a visual clue to the meanings encoded in the miniatures.

While a flowering staff is a standard topos in hagiographical texts, its presence here complements Didier’s role as bishop who exhorts sinners to repent. Didier’s ability to father or engender Christians is embedded in this image, but the sexualized language of the vie is even more explicit when describing how he brings men to the faith. After his consecration, for example, Didier offers such eloquent and beneficial instruction that “qu’il ravit tout le monde et d’ou chacun sortit tellement édifié, instruit, et satisfait” [it ravished all the world and everybody came out of there so edified, instructed, and satisfied] (fol. 16r). As this passage suggests, the language of the vie is eroticized to focus on multiple desires and fulfillment. Recalling the wordplay of the Italian chronicle, the name Desiderius itself is an indication that God desires him to be his servant, even as Didier is the one the people desire to be their bishop. The narrator of the vie defines the name for the audience, saying, “Le nom de Didier qui lui fut donné à son baptème est mystèrieux et conforme aux semences des graces dont Dieu avait déjà favorisé son âme” [the name of Didier, which was given at his baptism, is mysterious and conforms to the seeds of grace with which God had already favored his soul] (fol. 2v). Forms of désirér, moreover, appear throughout the vie reminding readers of the eponymous saint and of their own desires as penitents. The text makes the metaphorical act of desiring literal; when Didier identifies himself as a humble servant of Christ, his words ravish the delegation:

“Ce qui ravit en admiration ces Messieurs et dont ils sentirent leurs cœurs dilatés d’une si grande joie, que leurs yeux en versèrent des larmes et leurs langues l’épandirent en louanges et actions de grâces à la bonté divine d’avoir enfin satisfait à leurs désirs ayant enfin trouvé le Didier tant désiré des hommes et des anges pour être leur Évêque.” (fols. 8r/v, emphasis ours)[This ravished these gentlemen with admiration, and gave them the feeling that their hearts were expanding with a great joy, and their eyes shed tears, and their tongues poured out praise, and other such actions of grace towards the divine kindness, having at last satisfied their desires by finding the Didier whom men and angels so desire to be their bishop.]

Along with words of desire, the narrative indicates ravishment is the means by which desires are fulfilled. As in Latin, the modern French verb ravir retains its medieval connotations of “to take pleasure in,” “to delight,” “to be overcome sexually,” and “to be taken or stolen by force.”[36] Spiritually enervating preaching overcomes the congregants who experience desire themselves. The rapture of the delegation, moreover, is completed by satisfaction. Recalling Hebrews 4.12, in which the Word of God is likened to a double-edged sword that penetrates the body to distinguish the soul and the spirit, this passage demonstrates that Didier’s parishioners come to spiritual and physical contentment in hearing their desired one speak.[37] Thus, the narrative frames speech as the means by which the bishop asserts his sovereignty and his paternity; hearing Didier’s preaching brings the Langrois into community: he is the father who engenders his spiritual family.

How a ploughman becomes so capable a preacher is unfathomable, yet the vie makes it clear that as God’s chosen, Didier is enflamed by the Holy Spirit. He is clothed by an angel, who “les habits pontificaux desquels il devait être revêtu avec la mitre et le baton pastoral” [furnishes all the pontifical habits of he who was to take on the mitre and the pastoral baton] (fol. 11r). This episode originates in the Italian tradition, perhaps as a result of Mediterranean cultural exchange, as the delivery of robes by an angel to a holy man is a common miracle in Islamic texts, usually after enduring a crisis.[38] For Didier, it is a crisis of self-doubt. He insists that he does not have the ability, that he “avait été élevé et nourri pour labourer la terre qu’il étant sans savoir et sans expérience” [had been raised and nourished to plow the earth, that he was without knowledge and without experience] (fol. 13v). Didier does not aspire to power, and therefore sees his investiture as a charge or “burden” (fol. 9v). The text explains that this is exactly what makes Didier perfect for this role. Royer paraphrases Luke 17.10: “après que vous aurez fait tout le bien à vous possible confessez que vous êtes serviteur inutiles” [after you have done all the good you possibly can, confess that you are useless servants] (fols. 11r/v). What is special about Didier is his awareness of his limitations. He is wracked with anxiety the night before his coronation, passing

“toute la nuit en prières et oraisons si ferventes, qu’enfin une Colombe éclatante en lumière, symbole du Saint Esprit, parut sur sa tête pour l’assurer de sa présence et de son assistance. Et dès lors il reconnut sa esprit si éclairé de lumières, son cœur tellement fortifié, qu’il prit résolution de travailler de toutes ses forces pour le salut des âmes, et induire particulièrement son Diocèse à la vertu par son exemple et par sa parole” (fols. 15r/v).[all the night in prayers and orisons so fervent that in the end a Dove, bursting with light, symbol of the Holy Spirit, appeared on his head to assure him of its presence and of its assistance. And from then on he admitted that his spirit was so enlightened, his heart so strong, that he had the resolution to work with all his power for the saving of souls, and to induce in particular his diocese towards virtue by his example and by his word].

The focus on an unlearned, secular man who is overnight made a bishop underscores God’s sovereignty. Mirroring the miracle of “Cædmon’s Hymn,” in which an unlearned herdsman learns to sing about God’s creation through a divine vision, Didier’s miraculous ascension and his new-found eloquence leaves his spiritual authority without doubt.[39] It is by divine intervention that he is located, by divine intervention that he is dressed, and by divine intervention that he has anything to say at all. Given the co-mingling of spiritual imagery and masculine virility, we are invited to view Didier’s as not merely an ecclesiastical success story, but as the fulfillment of a humble ideal of masculine sanctity.[40]

Yet, these images of masculine virility are undercut in many ways. Didier fails as a ploughman when his oxen refuse to move. Further, Didier’s decapitation illustrates that he cannot save himself or his people. The phallic sword wielded by a powerful Vandal stresses his powerlessness in the face of violence (Figure 4). Where the verdant landscape replete with blooming flowers suggests vitality, the figure of the bishop is static. On his knees in prayer, wearing a royal blue vestment, white gloves, and mitre, Didier’s submission is absolute. Indeed, his robes occlude the powerful physique observed when he drives the plow (Figure 2). By contrast, the Vandal’s heavily muscled legs, encased in royal blue tights (and highlighted with white), are accentuated by the short brown tunic and calf-high brown boots. The stance, which shows the Vandal’s weight on his right leg, indicates the impending action: the right arm crosses the body with the sword raised at the top of his swing; the downward stroke will force his weight onto the left leg. The alignment of the Vandal’s body from lower right to upper left commands the scene. Behind him are the intact walls of Langres with the cathedral’s bell tower in the distance. The setting outside of the walls suggests that the bishop has willingly faced the Vandals outside the town. This is a key divergence from Flamang’s play, in which the bishop ascends the walls to parley with Chrocus and offers himself in exchange for the safety of Langres.[41] The Vandals refuse and sack the town, finding the bishop in the church on his knees where he is killed within the city.[42] Royer’s vie does not explain how the bishop comes to be in the field outside, a lacuna that is glossed over by the depiction of the martyr outside the walls, which has not been breached.

In the passages leading up to Didier’s martyrdom, the focus of the vie is on the violence of the Vandals. Where Didier represents virile fortitude, the Vandals are pure rage (fol. 17v).[43] While Langres is presented as an urbane, civilized place of Christianity, the Vandals are wild and ungoverned barbares [barbarians] (fol. 17v). Didier’s virile strength is used to plow the earth, laboring to do good works that will bear fruit, but the physicality of the Vandals only brings death. Not only are they evil, their nature makes them inhuman. They are tigres [tigers] of nombre effroyable [horrifying number] and violence extraordinaire [extraordinary violence] (fol. 16v). Where the vie emphasizes Didier’s attractiveness to both men and women, the Vandals are dangerous to all, as they “n’épargnèrent ni âge ni sexe à se saouler même du sang des innocents pendants aux mamelles de leurs mères” [spared neither age nor sex, getting themselves drunk on the blood of the innocents hanging on the breasts of their mothers] (fol. 16v). This imagery is in stark contrast with Didier’s posthumous miracles, which recalls moments of nurture when Didier helps “femmes réduites aux extrémités de la vie, de produire leur fruit par les mérites et intercessions de ce grand Saint ont été délivrées à l’instant et leur fruit lavé de l’eau du Saint Baptême” [women reduced to the extremes of life produce their fruit by the merits and intercessions of this great Saint, delivering in an instant and washing their fruit in the water of Holy Baptism] (fol. 21v).

Vandal rage drives Chrocus to demand Didier’s death, but Didier’s body continues to function. The second miracle describes Didier “portant sa tête qu’il avait consacrée à Dieu pour sa gloire” [carrying his head which he had consecrated to God for His glory] (fol. 19r) to his own grave. The vie recounts a third miracle. Not only is Didier’s head cut clean off, but the Gospel book that he carries is also pierced with the

“même glaive que le bourreau lui avait avalé la tête, et que le sang qui ruisselait de toutes parts à découler sur ce livre: néanmoins il ne fut pas endommagé et n’y eut pas un seule lettre effacée et se lisait aussi facilement que même longtemps après quand on a relevé son corps et enchâssé ses Saintes Reliques, ou a encore un et tiré d’icelui cet écrit miraculeux.” (fols. 19r/v)[very same blade that the executioner had used to slice off his head, his blood spattered all over it, oozing through the book. Nevertheless, it was not damaged, and not a single letter was erased, and it read as easily as ever, so that even a long time after when they raised his body and set out his Holy Relics, they still saw and comprehended in it this miraculous writing].

The execution of the bishop is directly aligned with the desecration of the gospel book. The sword of the executioner performs a sacrilegious act by its penetration of the Word, yet the bloodied Gospels continue to signify, just as the desecrated corpse continues to act. And while Didier can no longer speak, the Gospels convey meaning. Symbolically, the text that recounts Christ’s martyrdom and regeneration reminds believers that Didier’s efficacy remains: his preaching of the Gospel endures when the book he carries remains legible. And where Didier preserves his own head, the executioner’s is completely annihilated. In response to this act of murder, God causes Godifer to be “saisi d’une si grande frénésie et aliénation d’esprit” [seized by such a great frenzy and alienation of spirit] (fols. 18r/v) that he “il se heurta si brusquement la tête contre la porte” [brusquely bashed his brains out on the gate] (fol. 18v). First he loses his mind, and then his head is destroyed completely, a scene original to Varnahaire’s Latin text. So while Didier may have lost his “tête et la vie” [head and life], the executioner suffers a far worse fate, losing “sa vie et son âme” [his life and soul] (fol. 18v).

A final point of contrast between Didier and the Vandals occurs at his death. The bishop loses the battle, since “[l]es larmes de Saint Didier qui s’exposa comme une victime pour son troupeau, ses prières ni celles de tout son Clergé . . . n’eurent pas assez de force pour fléchir” [the tears of Saint Didier, who exposed himself as a victim for his flock, his prayers, nor those of all his clergy . . . had enough force to sway the] Vandals (fol. 17v). Didier, even at the zenith of his worldly power, is not strong enough to overcome enemies of the Church. Further, it is implied that Didier’s preaching was not entirely efficacious, for immediately following the description of the bishop’s sermons, the vie indicates that the country remained so full of “péchés et désordres” [sins and disorders] that “Dieu voulant châtier” [God wished to chastise] (fol. 16r) the people. That is, God allows the Vandals to terrorize Gaul because of the people’s sins. It seems that despite Didier’s initial success, he fails to bring all of France into the fold.

Yet, in this defeat and sacrifice is a standard Christian victory. While it may seem to a modern audience that Didier’s masculinity is undercut by his physical defeat and humiliation, in Christian ideology, such humiliation is actually a hallmark of robust virility. Early Christian martyr tales, such as the Didier, were profoundly influenced by a now apocryphal appendix to the Greek Bible known as 4 Maccabees.[44] As David A. deSilva notes, that first-century text bears many hallmarks that appear in the Didier: an evil “tyrant” (4 Maccabees 8.2) dominated by “violent rage” (4 Maccabees 9.28) sends his “leopard-like” (4 Maccabees 9.28) servants to torture and murder holy men defending their religious community.[45] The endurance of suffering, according to this text, makes one “a noble athlete” (4 Maccabees 7.10). The men die nobly, understanding that their persecutor will be punished by God. From this perspective, the victorious man does not execute violence; rather, he endures suffering with grace.

Royer’s illustration of the post-mortem Didier as a cephalophore emphasizes the value of his sacrifice (Figure 5). The face is pale white, drained of blood, and the neck is bloodied, yet no stain mars Didier’s white gloves or amice. A thin halo encircles the neck wound, highlighting the significance of the functioning corpse. Didier, whose voluminous blue cope is richly embroidered with white and gold, stands on a green lawn with blooming flowers before the walls of the city, with his cathedral (with bell tower) and the small church in which he is enshrined prominently visible in the background. This image invokes the iconography of acephalous saints in late-medieval books of hours, such as St. Denis, whose Parisian cult Royer seems to be imitating.[46]

Figure 7. Denis of Paris as acephalous saint. Master of Sir John Fastolf. Book of Hours. Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, MS 5, fol. 35r. 1430–1440. Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program.

In Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, MS 5, fol. 35r, which is dated between 1430 and 1440 (Figure 7), two nimbed angels support the decapitated but erect corpse of Denis.[47] The bishop’s arms cradle his haloed head, which is prominently displayed at center. The gory neck is highlighted by a second golden disc, as blood drips onto the amice. Similarly, blood trails through the bishop’s fingers, but the rest of his vestments are clean. Royer’s depiction of Didier in episcopal vestments shows his reliance on such static images, and the setting indicates Royer’s awareness of a standard representation of cephalophore saints before a natural or architectural backdrop. Where Denis stands before a hill of rock (which might be understood to be Montmartre), Didier is placed before his walled city, which appears untouched by siege. The walls are intact, the church stands tall behind the bishop, and trees shade the city. The image Royer offers is the Church unshaken. Where the Vandals have clearly martyred the bishop, God has preserved the town. Imagery of flowering plants and trees is but another indication that the city was not defeated but regenerated and continues steadfast. As Royer’s vie indicates, the bishop “s’exposa comme une victime pour son troupeau” [exposed himself as a victim for his flock] (fol. 17v) and was “executé sure le champ” [executed in a field] (fol. 18r), but the city’s “enceinte de murailles fortifiées de bonnes tours et boulevards semblant assez considérable” [enclosure of high walls seemed quite considerable, being fortified with good towers and boulevards] (fol. 16v).

Royer’s insistence on the integrity of his city is in direct contrast to two medieval depictions of Didier’s martyrdom in fifteenth-century copies of Vincent of Beauvais’ Speculum historiale. Both quite vividly portray the moment before Didier’s death within the city’s walls.

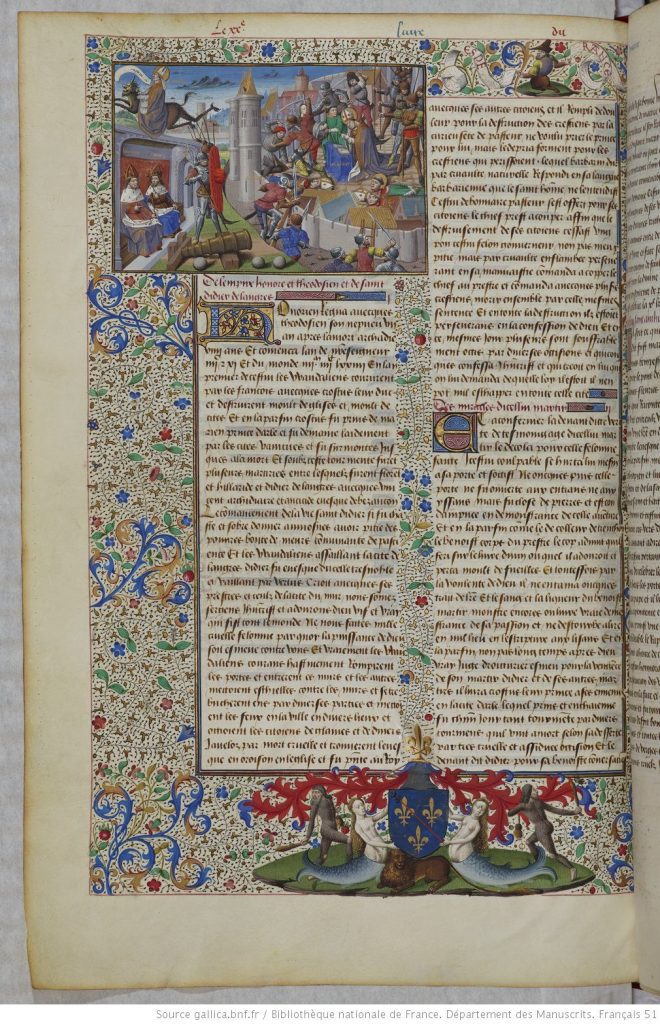

Figure 8. Martyrdom of Bishop Didier of Langres. Vincent of Beauvais’ Le Mirouer historial, translation by Jehan du Vignay. XVe. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Français 51, fol. 328v. Digital image courtesy gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

In Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms Français 51, fol. 328v (Figure 8), the artist stresses the chaos of a city under siege, with Vandals actively climbing the walls while others inside have decapitated a number of religious figures. Didier, who is accompanied by a cleric holding his episcopal staff, kneels at a prie dieu (on which his name is inscribed), wearing his vestments, mitre, and gloves. His peaceful countenance contrasts with the raging battle. Behind him, the leader Chrocus (whose name is painted at his feet), directs the execution. Godifer holds his sword in both hands. His arms are extended behind his head in mid-swing, stopping the action at precisely the moment before Didier is to die.

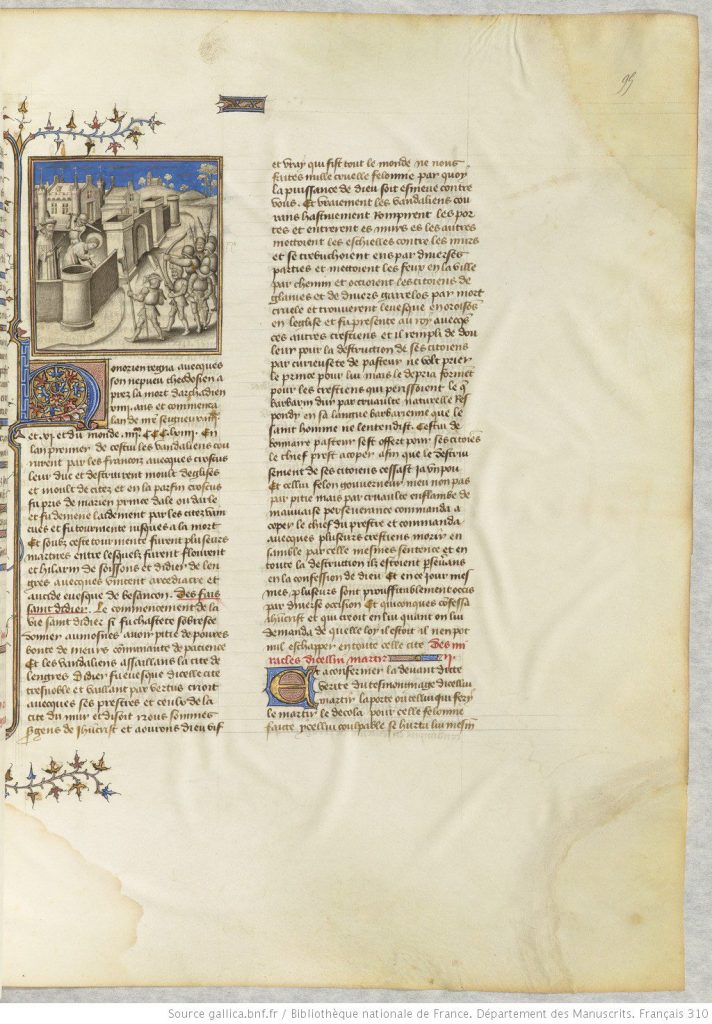

Figure 9. Martyrdom of Bishop Didier of Langres. Limner: Willem Vrelant (1410?–1481). Bibliothèque nationale de France, Département des manuscrits, Français 310, fol. 95r. Digital image courtesy gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France.

A similar scene is found in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms Français 310, fol. 95r (Figure 9), where the executioner is poised for the downstroke. Chrocus stands within the walls of Langres behind Didier, holding a scepter and wearing a Phrygian hat, which as Naomi Lubrich has shown was an iconographical device for “barbarian” in the Roman world and later evocative of Jews or Others in Christian medieval iconography.[48] Didier’s costume and posture, however, differs: his humble robe, with nimbus, indicates his sanctity, but there are no markers of his episcopal status, as he leans forward as though falling to the earth. Outside the walls, soldiers stand poised to attack.

Similar imagery adorned Didier’s tomb. Arnaud Vaillant has identified part of the pictorial programme of the remnants of Didier’s stone sarcophagus, which was destroyed during the French Revolution.[49] He shows that the tomb was sculpted between 1230 and 1260 and featured two registers on the long sides, with an abundance of floriation entirely in keeping with the miracle of the flowering rod. The north side can be more fully reconstructed thanks to a 1670 engraving by Jacques Vignier. The upper register depicts three scenes from the bishop’s life: his investiture; his engagement with the Vandals climbing a ladder placed against the city walls; and his martyrdom at the hands of Godifer outside Langres. We are lacking more than half of the south side of the tomb, but one panel shows Didier as a cephalophore, yet the remaining scenes suggest that this programme did not include his antecedents as a farmer or his election by God. The tomb’s narrative programme, which Royer would have known, may therefore have influenced his presentation of Didier’s martyrdom extra urbis. Another local scene may have been equally instrumental.

The Registre de la Confrérie de Saint-Didier was begun in the early sixteenth century and includes a miniature depicting Didier’s martyrdom. In a manuscript known as Langres, Musée d’Art et d’Histoire, Manuscript 169, fol. 14r, this miniature is divided into two scenes demarcated by the decorative details on the architectural column (Figure 10).[50]

Figure 10. Martyrdom of Bishop Didier of Langres. Langres, Musée de Langres, MS 169: Registre de la Confrérie de Saint-Didier, fol. 14r. Early sixteenth century. Dépôt Société Historique et Archéologique de Langres au Musée de Langres (SHAL), cl. S. Riandet. Digital image courtesy of SHAL.

In the lower register, Didier, in vestments, kneels in prayer outside the city with his gospel book on the ground before him. Godifer (whose name is inscribed on his galliegascoignes) is poised to strike, while Chrocus and his men watch from the left. Above, the scene shifts to show Godifer bashing his head against the city gate, a significant element in the Latin vita and the French play. The complete destruction of Godifer’s head, which replicates the saint’s decapitation, serves here to differentiate Didier’s fortitude from Vandal instability. The viewer is encouraged to read the scene from bottom to top by naked figures on each side of the architectural frame. The cherub at the lower right wrestles with a serpent, and the one above him swings from a decorated cord that is replicated on the left. Another figure at the top left raises a rope via a pulley, and a fourth figure dangles from its end. Inside the frame at upper-right, two angels hold a veil, in anticipation of escorting Didier’s soul to heaven. Didier’s spiritual victory is complemented by the city’s: the Registre shows that the gate remains closed, and the walls are intact. The city has not been defeated, and God’s celestial army is in force.

As we have seen, Royer’s presentation of Didier’s martyrdom follows the Langrois artist’s setting for the execution outside the city walls. Where he elected to use the iconography of acephalous saints when painting the static image of the martyred saint, he rejected the presentation of the Speculum historiale in favor of imagery that suggests the city’s victory. That is, in representing Didier’s martyrdom as the Registre had done (an image most certainly available to Royer for consultation while his brother served as conservator of the museum in which it is housed), Royer’s visual programme could assert that Didier’s sacrifice had saved the city. This insistence on the city’s viability accords with Royer’s larger pictorial narrative, in which Didier, as God’s chosen, becomes a metonym for a city that cannot be destroyed. Like Christ, Didier is physically defeated by worldly powers, enduring great suffering, only to rise again to perform more miracles. Thus, Didier’s virile fortitude does not overcome violence, but rather endures it. His epitaph reads “ici repose le corps de l’insigne et admirable Didier . . . Pasteur rempli de toutes les vertus tant morales que chrétiennes, un parfait Exemplaire de toute Sainteté” [here lies the body of the distinguished and admirable Didier . . . pastor full of all the virtues, so many Christian morals, and perfect Exemplar of all Holiness] (fols. 19r–20v).

Where the visual programme of Royer’s book highlights the stability of Langres in the face of Vandal violence, the narrative, as we have suggested here, is more multivalent. Where Flamang’s play showcased Didier’s heroism in the face of the Vandal rage—and God’s preferment of Didier—Royer’s vie assigns blame to the people for not heeding the bishop’s call and seemingly frames the martyrdom as the bishop’s failure. A saint’s life, of course, is at heart a demonstration of God’s beneficence in human affairs. Didier’s strength is his role as God’s humble servant, even sacrificing himself to save his people. A quantitative analysis of the vie’s structure and its terminology affirms God’s centrality.[51] The ninth section of Royer’s text is the longest of the twenty-two divisions and narrates the miraculous proofs of God’s favor. It contains 561 words to describe the discovery of Didier as ploughman, his resistance to being called to serve, his defiance in thrusting his verge into the earth, and the miraculous transformation of the rod into a flowering tree. Only after a conversation with a hermit who tells Didier he should not refuse God’s call and the miraculous delivery of ecclesiastical vestments does Didier accept that he is worthy of any attention. God has to prove three times that he intends for such a mediocre man to be his chosen one. The size of this episode reinforces its central importance and underscores God’s authority.

Didier’s secondary status before God is reflected more clearly in the text’s terminology. Despite this being a saint’s life, Didier is not properly the main character of the text: God performs most of the action in the story. The word dieu occurs thirty-four times; whereas didier comes in third place at twenty-eight occurrences.[52] The term didier is most frequent at the beginning of the vie and usage dwindles throughout. God’s power comes to the fore as Didier hears his calling, submits to his fate, and ultimately dies. A notable increase in the term’s usage occurs in section seven where the Langrois delegation first encounters Didier. The term dieu occurs throughout the text, but usage peaks around section twenty. After Didier has been killed but before Chrocus is punished, the vie presents the power of Didier’s sepulchre: “jamais il n’est entré personne qui rempli de témérité et outrecuidance, ait fait faux serment et se soit parjuré, qui soit sorti de la sans avoir ressenti et expérimenté la vengeance divine et les justes punitions et châtiments de Dieu” [never entered anyone, who full of temerity and arrogance, making a false oath and perjuring himself, who came out of there without feeling and experiencing the divine vengeance and just punishments and chastisements of God] (fol. 20r). God’s presence is ascendant as Chrocus dies.

These quantitative aspects, which we have only addressed here briefly, underscore the themes of the Royer Didier. Didier’s nobility does not stem from heredity, but is a product of God’s favor, and thus Didier’s miraculous rise as the city’s overlord receives the most attention. Didier’s failure to avenge himself on the Vandals reflects his humility before God and his obedient service. The vie contends Didier “se rendit très parfait imitateur du divin Apôtre Saint Paul” [rendered himself the perfect imitator of the divine Apostle Saint Paul] (fol. 2v), who implored his followers to live harmoniously, to be humble and modest, to remain noble in the face of evil, to live peaceably with all, and to leave vengeance to God (Romans 12.16–19). In short, Didier is noble because he is humble and peaceful. The longest sentence of the vie, moreover, occurs in section nineteen, where the miracle of the gospel book is described, with livre along with corps being the most prominent terms alongside feuillet, which aligns with the focus of the living corpse and the living Gospel. The dramatic climax, therefore, is a recounting of the divine powers and durability of the book, contrasted with the decaying body and the spoken words of liars. This emphasis is a reminder of the strength of God’s Word but also the value of the codex, that is, the book as an object within the vie, and the vie as an object within a devotional book. Royer has already invited us to objectify Didier by repeatedly calling attention to his name. The Royer Didier, therefore, offers a physical, sensual answer to the spiritual desires of the reader, providing a metacognitive engagement for the devotee.

The colors Royer chose within and without the book further signify Didier’s martyrdom and remind the devotional reader of his sacrifice. The red and blue flowers in the gold borders complement the image of the decapitated body, vested in blue and white, the bloody neck encircled by a gold halo. Royer’s presentation of the martyrdom (Figure 4) is supported with the symbolism of a large green caterpillar on a twig, prior to its life change into a chrysalis and eventually a butterfly. As a reminder of regeneration that comes through seeming death, the caterpillar directly beneath the kneeling bishop offers hope of Christian victory. The red leather binding represents Didier’s passion but also his robust immortality. And Didier’s vestments are also reflected in Royer’s choice to use blue-silk inserts: the book is dressed just as Didier is, reflecting the contemporary idea that “the art of the bookbinder is to contrive a garb becoming to the author and to the nature of the work, just as the art of dress is to express in some degree the character and function of the wearer.”[53] Didier is invested with robes not by a king, cleric, or some other worldly power; God himself appoints Didier and invests him.[54] Didier, despite his deep anxieties about his own worth, is able to sublimate his masculine virility into a humble devotion to God. His sacrifice becomes a sacred text that can be read and visualized, as well as rewritten and deployed to engender belief and devotion. One might well read the production of Royer’s Didier similarly. Joseph Royer’s book invites us to objectify Didier, even as it invites us to objectify the book itself as a representation of the medieval past and a statement about Langres’ present. The book’s color scheme also reflects the coat of arms of Langres—d’azur semé de fleurs de lis d’or, au sautoir cousu de gueules—demonstrating that it is to be read as a symbol for the city.[55] Royer’s devotional insists, therefore, that despite Didier’s (and the city’s) defeat, the diocese is intact, and the town of Langres remains fortified. The sky is dark in Royer’s final miniature, with only a splash of sunlight emanating from just below the horizon, hinting at the possibility of a new dawn. By suffering with fortitude, the image reminds the viewer, that the faithful of Didier’s flock will flourish.

The Miracle of the Book

As we have suggested here, Royer used a coordinated visual rhetoric to communicate with other bibliophiles. It was common practice for late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century bookmakers to craft their books so that the physical object represented the themes of the text contained within it.[56] The term “bibliophile” is not applied lightly to Joseph Royer. Neither he nor his brother ever married. They dedicated their lives to producing works of art and conserving the past. Seemingly, Joseph lived in the shadow of Charles, and has been referred to as the “lesser” brother, and while Charles’ devotion to Musée d’Art et d’Histoire is evident, it is Joseph’s dedication to book arts that rewrites the narrative of the community’s history.[57] The Didier, the first text that Joseph Royer designed and made, seems to reflect the circumstances of his own life, his own desires. Didier, a simple man of no particular talent, is able to rise and become a hero of Langres through faith alone. His miraculous investiture mirrors that of Aaron, who, like Joseph, is the lesser brother: “[M]éprisé et inconnu sur la terre, jusqu’à ce qu’il plut à Dieu” [Scorned and unknown on the earth, until it pleased God] (fol. 3r). We might well imagine that Royer created this book as an expression and consummation of his own desires as a bibliophile and son of Langres. The reasons behind Royer’s celebration of Langres precisely at the start of a new century may have to do with francophone anxieties about Germany’s 1871 annexation of Alsace-Lorraine and the establishment of the German national state following France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.[58] As a fortified city in northeastern France, Langres occupied a strategic but precarious location in the face of any future offensive. Eight forts were built around Langres in the late-nineteenth century to protect the city from Germany.[59] That Royer’s book is a narrative about Vandal violence against the Langrois provides one possibility for the production of the Royer Didier at the fin-de-siècle. [60] In using book arts to stage the town’s history, Royer—himself a collector of medieval Langrois books—presented a beautifully illuminated devotional that rewrites the medieval past from a nineteenth-century vantage, suggesting to the townspeople that should they again be faced with the threat of Germanic violence, God and his Didier will sustain them. Or, it may have simply offered a personal message of reassurance. If the book were made for Royer’s own private devotions, it would explain why it was not donated to the Société Historique et Archéologique de Langres. Given this, it is surprising that this honorific to the city of Langres was not included in the donation, when one realizes that the museum itself was born out of the deconsecrated space of a Romanesque church where the medieval tomb of Didier was located and where its remnants remain.[61] This chapel, adjacent to the city’s cathedral, was transformed into the repository of Langres’ lapidary history in 1838 (Figure 11).[62]

Figure 11. Nave, Church of Saint-Didier, Langres, location of the medieval tomb of Bishop Didier of Langres. Now the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire de Langres. Photo: Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement (1840–1905). “Eglise Saint-Didier,” Médiathèque de l’architecture et du patrimoine. Digital image courtesy of Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

It would seem that Royer’s Didier would have been an ideal gift for the museum, especially when one realizes that Royer employs an archway supported by Corinthian columns (perhaps a deliberate echo of the museum and former shrine of Didier) as a frame for his depiction of the canons and citizens receiving the angel’s announcement. Be that as it may, the work of Royer—like that of other French Medieval Revivalists—created a space where people could indeed find repose and fulfillment of their desires, away from the increasingly dangerous modern world. This nostalgia was palpable and contagious. So much so, that in John Dos Passos’ novel One Man’s Initiation: 1917, written in the trenches of France, a wearied American soldier finds relief from his unfulfilled spiritual desires in the chaos around him, dreaming

of the quiet lives the monks must have passed in their beautiful abbey so far away in the Forest of the Argonne, digging and planting in the rich lands of the valley, making flowers bloom in the garden . . . he had found a few torn remnants of books; there must have been a library in the old days, rows and rows of musty-smelling volumes in rich brown calf worn by use to velvet softness, and in cream-coloured parchment where the fingermarks of generations showed brown; huge psalters with notes and chants illuminated in green and ultramarine and gold; manuscripts of the Middle Ages with strange script and pictures in pure vivid colours; lives of saints, thoughts polished by years of quiet meditation of old divines; old romances of chivalry; tales of blood and death and love where the crude agony of life was seen through a dawn-like mist of gentle beauty. ‘God! if there was somewhere nowadays where you could flee from all this stupidity, from all this cant of governments, and this hideous reiteration of hatred, this strangling hatred . . .’ he would say to himself, and see himself working in the fields, copying parchments in quaint letterings, drowsing his feverish desires to calm . . . .[63]

Even as he sought to honor Didier as the city’s savior, Joseph Royer succeeded in becoming a beloved hero of Langres. On 10 January 1934, he was elected to the Ordre national de la Légion d’honneur. After his death on 5 July 1941, he was memorialized in ways that recall the motifs of hagiography: he was known for his youthful vigor, quick smile, and good humor, as well as his many selfless contributions.[64] Royer died just after Langres was overrun by a German warlord. The nightmare of the city’s invasion that the Didier recounts had once again come to pass. Like Didier, Royer posthumously reenergized his defeated community with gifts of cultural heritage: a library of books celebrating the town’s history, the installation of which commenced November 1943 and was only completed in September 1945, just after the liberation of France from German occupation. The reason for the delay was to preserve the books from Nazi appropriation, and Royer’s death notice frames this act as one of dignified resistance.[65] Royer’s books now reside in a museum that was once a monument to Didier’s shrine. We might say that Royer’s life and work represents a provincial pride, an attempt to cultivate a rich, artistic life far away from the urbane glare of Paris and the all-too-present challenges of living so close to the German national border. We may never know why and how the Royer Didier was separated from the collection donated to SHAL, but it has found a good home at the Spencer Research Library in Kansas City, Missouri.[66] The Library’s stewardship and commitment to fostering scholarship exemplifies exactly the kind of investment in one’s local community that Royer made the guiding principle of his life. We might say, then, that the desires of the bibliophile-turn-bookmaker expressed in the Royer Didier were indeed satisfied.

Appendix A—Transcription of La Vie Mort et Passion du Bienheureux Saint Didier

The prose text is emended without comment to correct small errors in spelling and to reflect contemporary diacritics. Capitalization remains as represented in the Royer Didier. Sections of the vie demarcated by decorated capitals are indicated numerically below to accord with the source study and computational discussion above.

La Vie Mort et Passion du Bienheureux Saint Didier de Gênes Evêque de Langres.

[1] Saint Didier prit sa naissance en Italie en un petit lieu nommé Fravegue distant d’une lieue et demie de l’illustre et antique cité de Gênes et fut élevé et nourri en une métairie nommée Bavarum proche de la dite cité et déclinant du côté de l’orient.

[2] Le nom de Didier qui lui fut donné à son baptême est mystérieux et conforme aux semences des grâces dont Dieu avait déjà favorisé son âme, puisque l’humilité la crainte et la très étroite soumission à ses commandements ayant pris de très profondes racines en lui, son cœur était rempli de désirs tout célestes et surhumains. Si bien qu’arrivé en âge propre pour travailler, il se rendit très parfait imitateur du divin Apôtre Saint Paul qui vivait du travail de ses mains et en soulageait les pauvres: sachant bien qu’il n’y a rien qui retarde davantage une âme chrétienne qui veut faire progrès à la vertu que la paresse et l’oisiveté. C’est pourquoi s’exerçant en toutes les actions de piété et charité, il se rendit autant admirable dans le ciel qu’il était méprisé et inconnu sur la terre, jusqu’à ce qu’il plut à Dieu qui est le Père des lumières et des miséricordes, de faire éclater cette lumière au milieu de son Eglise pour l’édification et consolation de ses fidèles serviteurs.

[3] Ce qui arriva au temps que l’Église de Langres était demeurée sans Évêque le Siège vacant par la mort de Iustus son Prélat et Pasteur. Alors le Chapitre de ladite Église s’étant assemblé, après l’être disposé pour recevoir les grâces et les lumières nécessaires pour faire l’élection d’une Personne en la place selon le cœur de Dieu et capable de cette charge, comme on était aux opinions, chose miraculeuse, un Ange envoyé du Ciel apparut au milieu du Chapitre et leur dit ces mots: « Didier sera votre Évêque. » Paroles qui les étonnèrent autant que la présence de celui qui les prononçait. Ce qui donna à l’assemblée sujet de se lever ne songeant plus aux suffrages et opinions pour ladite élection mais seulement à demander et s’enquérir de celui portait le nom de Didier, afin de bien conformer leur élection à celle qui avait été faite de toute éternité dans le Ciel.

[4] Tous se mettent en peine de savoir s’il y a quelqu’un qui porte le nom de Didier: on envoie des commissaires partout le Diocèse pour en savoir des nouvelles: lesquels après une très exacte recherche n’ayant trouvé personne qui approchant soi peu de ce nom, très assurés de la vision de l’Ange et du choix que Dieu avait fait de leur Évêque ils ne furent pas si téméraires que de passer outre et songer à une autre élection: mais bien instruits à l’obéissance et au respect qu’ils devaient au Chef de l’Eglise que Dieu a laissé en icelle pour rendre ses oracles, le Chapitre fut assemblé pour la seconde fois ou le Premier eu dignité de leur Église 11 fut député avec autres de plus notables du Clergé et des plus nobles de la Ville pour aller consulter sur ce fait le Saint Siège apostolique représenter les procès verbaux et attestations de tout le procédé et de ce qui l’était passe au Chapitre de Langres et pour supplier la Sainteté de leur accorder pour Évêque celui que le Ciel par la voix de l’Ange appelait Didier.

[5] Ces députés furent reçus avec tous les témoignages d’humanité et bienveillance que l’on peut désirer d’un père envers ses enfants et la Sainteté les exhorta à avoir grande confiance en la parole de Dieu qui est toujours fidèle en les promesses: et leur baillant la bénédiction leur dit ces paroles du Prophète: vous leur avez donné selon leurs désirs et n’avez point rejeté les prières et les vœux qui sont sortis de leurs bouches: l’espérance qu’ils ont toujours eu en votre bénignité ne sera point vaine: vos bénédictions ont prévenu leurs désirs leur faisant plus de bien qu’ils n’en pouvaient souhaiter puisque vous leur donnez un Évêque que vous voulez couronner d’une couronne de pierres précieuses émaillées de toutes sortes de vertus chrétiennes appelé Didier.

[6] Or sa Sainteté ayant congédié les susdits députés après leur avoir donné la bénédiction paternelle les exhorta de promptement et sans aucun retard chercher l’homme de Dieu appelé Didier pour être leur Evêque très satisfaits et consolés de ses instructions: si bien qu’au même instant ils disposent de leur retour, assurés enfin qu’ils ne seraient frustrés de leurs désirs et après avoir traversé beaucoup de pays, ils arrivèrent à l’état de Gênes ou étant, comme ils vinrent à passer le pont d’une petite rivière ou torrent qui s’appelle Sturla, ils aperçurent un laboureur qui était au milieu d’un champ avec la charrue et des bœufs accouplés qui labourait la terre, et l’ayant bien considéré, ils remarquèrent soigneusement que quoiqu’il sollicitât les bêtes tant de la voix que de son aiguillon duquel illes piquait plus fort qu’auparavant, elles demeuraient néanmoins immobiles et sans vouloir avancer ni bouger de la place, et entendirent clairement ce laboureur qui leur dit hautement et comme fâché et ennuyé de ce qu’elles ne voulaient pas avancer: « Par la tête de Didier vous marcherez et avancerez. »

[7] Ces Messieurs ayant entendu que ce laboureur nommait le nom de Didier, s’arrêtèrent tout coi, et se rendant attentifs au discours qu’il tiendrait. Ses bœufs plus rétifs et arrêtés qu’auparavant, ils lui entendirent pour la seconde fois en les piquant de son aiguillon, répliquer ces mêmes paroles qu’il avait déjà proférées: « Par la tête de Didier, vous passerez outre et avancerez. »

[8] Ce qu’ayant entendu, les députés mirent pied à terre et l’approchant de cet homme le saluèrent avec révérence en ces mots: « Le Seigneur soit avec vous ami de Dieu. » Et lui pareillement les ayant accueillis et rendu le salut avec honneur leur dit: « Chers amis de Dieu, soyez les bienvenus: que désirez-vous de moi. » Alors le Chef des députés lui répondit: « Nous vous supplions de nous dire quel est votre nom. » « Ie m’appelle, » leur répliqua-t-il, « Didier, humble serviteur de Iésus Christ. » Ce qu’il dit avec une grande prudence et modestie, témoignage des grâces qu’il avait reçues du Saint Esprit. Ce qui ravit en admiration ces Messieurs et dont ils sentirent leurs cœurs dilatés d’une si grande joie, que leurs yeux en versèrent des larmes et leurs langues l’épandirent en louanges et actions de grâces à la bonté divine d’avoir enfin satisfait à leurs désirs ayant enfin trouvé le Didier tant désiré des hommes et des anges pour être leur Évêque.

[9] Et après lui avoir rendu tous les devoirs et honneurs, ils le prièrent très instamment de s’acheminer avec eux à la ville de Langres, parce qu’ils étaient très assurés qu’il était choisi de Dieu pour être le Prélat et Pasteur de cette ville. Paroles qui étonnèrent d’abord ce grand homme de Dieu, lequel avait en éminence la sainte humilité qui est la base et le fondement de toutes les vertus chrétiennes. Si bien que par un mouvement particulier du Saint Esprit, ayant pris en la main l’aiguillon et la verge de laquelle il piquait ses bœufs, il leur dit en ces termes: « Quand cette verge aura produit des feuilles des fleurs et des fruits ce sera pour lors que je ferai votre Évêque. » Ô prodige, ô merveille de la toute puissance de Dieu: ces paroles furent elles à peine achevées, qu’en un instant cet aiguillon, cette verge s’épandit et fut chargée de fleurs, de feuilles et de fruits aussi bien que celle d’Aaron qui avait été choisi de Dieu pour être le grand prêtre de la loi ancienne. Miracle qui étonna autant Didier qu’il remplit de joie tous les députés d’avoir trouvé celui qu’ils désiraient. Et ainsi assurés de la volonté de Dieu retournèrent tous avec lui en ladite métairie de Bavarum et à Fravegue, lieux de sa naissance, proche lesquels lieux il y avait un saint hermite qui était nourri et entretenu des charités de Didier qui l’avait pris pour le directeur de sa conscience. C’est pourquoi il voulut avant que de se résoudre à accepter une si grande charge, prendre avis de lui de ce qu’il avait à faire: lequel après avoir été informé des merveilles et miracles que Dieu avait fait à sa considération, et pour faire connaître sa volonté au choix de sa personne lui donna avis de se soumettre avec humilité et confiance en la providence de Dieu et de ne point se rendre criminel devant sa Majesté par sa désobéissance. Pendant que Didier traitait de ses affaires avec le saint hermite, les députés consultaient des moyens pour amener l’Évêque désigné de leur pays en la ville de Langres avec tout l’honneur et bienséance dus à sa dignité, et étant en un pays pauvre et désert de toutes choses nécessaires, ne savaient à quoi se résoudre. Mais Dieu qui favorise toujours les dessins de ceux qui se soumettent à ses volontés, leur envoya un Ange qui leur laissa tout ce qu’ils pouvaient désirer, non seulement pour la conduite de leur Prélat, mais encore leur fournit tous les habits pontificaux desquels il devait être revêtu avec la mitre et le bâton pastoral qui sont les principales marques et les plus spécieux ornements des Évêques et Pontifes. Ce miracle et saveur singulière que cette Compagnie reçut, les obligea d’avoir leur Prélat en plus grande considération lequel d’autant plus qu’il se voyait honoré, autant s’humiliait il en son cœur, se voyant et estimant indigne de cette charge, et serviteur inutile à Dieu et à son Eglise, pratiquant en cela le conseil de Iésus Christ qui nous dit: après que vous aurez fait tout le bien à vous possible confessez que vous êtes serviteur inutiles. Référant avec Saint Paul et le Prophète Iérémie toutes les grâces qu’il avait reçues à Dieu qui en est le seul auteur et qui les départ à qui il lui plaît, suivant sa divine providence.

[10] Saint Didier dont rempli d’humilité, ne voulant rien présumer de soi même, prêt à obéir à la providence divine, prit conseil du saint hermite et lui dit: « Père saint que dois-je faire: faut il que je m’en aille avec ces messieurs. » « Oui, » lui répliqua-t-il, « allez ferme et confiant en l’amour de Dieu. Prenez courage et n’appréhendez rien parce que le Seigneur est avec vous, et l’Ange qui leur a déclaré en leur Chapitre que vous seriez leur Évêque et Pasteur vous accompagnera et sera votre guide. »

[11] Voilà Saint Didier résolu de se soumettre aux volontés de son Créateur qui accompagné de tous ces députés se met en chemin avec eux pour se rendre en la ville de Langres où est l’Église cathédrale et Siège Episcopal. Il n’y a plume si polie, langue si diserte, ni esprit si fécond, qui puisse exprimer la joie et le contentement du peuple, ni les honneurs qui furent rendus à Saint Didier, non seulement par tout le Clergé, mais encore par tous les Seigneurs de plus haute noblesse et par toute le peuple de l’un et de l’autre sexe qui accourait de toutes parts comme des essaims d’abeilles à ce saint homme pour recevoir sa bénédiction.

[12] Le lendemain de son arrivée, tout le clergé s’assembla pour prendre le jour de son Sacre et de la prise de possession de la Chaire Épiscopale, lequel étant arrivé, il se fit un si grand amas et concours de peuple, tant de la ville que de tout le diocèse et régions circonvoisines pour voir cette cérémonie et ce Saint Personnage ainsi choisi de Dieu, que l’Eglise quoique grande et spacieuse, ne se trouva pas capable de les recevoir tous. Ce qui donna sujet à Saint Didier après avoir considéré par son humilité sa faiblesse et ses défauts, de supplier le Clergé et tout le Peuple de ne le point contraindre à prendre cette charge et considérer qu’il avait été élevé et nourri pour labourer la terre qu’il étant sans savoir et sans expérience, et n’avait aucune partie sortable à cette éminente qualité. Et dès lors il parut en son visage et en son maintien un si grande majesté, que toute cette Assemblée s’écria qu’il ne pouvait ni devait résister à la volonté de Dieu qui l’avait choisi par tant de miracles pour être leur Évêque.

[13] On procède donc à son Sacre, il est revêtu des habits Pontificaux, de la Mitre sur la tête et du Bâton Pastoral en la main et ainsi est assis en la Chaire Épiscopale, de laquelle se relevant avec un grave modestie, donna sa Bénédiction à tout son peuple, qui témoigna avec des exclamations extraordinaires la joie et la satisfaction qu’il avait d’avoir vu Saint Didier qui avait été si longtemps cherché et désiré.

[14] Toutes ces cérémonies avec le jour parachevées, ce grand Saint sachant bien qu’il ne pouvait rien du tout sans l’assistance particulière du Saint Esprit, qui seul peut changer les simples pasteurs et bergerots comme David et Amos en Prophètes: qui remplit l’esprit de Daniel de lumières pour expliquer les visions des rois de l’Egypte: qui donna aux Apôtres la force, le courage et la patience les sciences et l’intelligence des langues pour supporter les tourments des tyrans, enseigner les peuples et planter par toutes les nations les trophées de Iésus Christ leur maître. Il passa toute la nuit en prières et oraisons si ferventes, qu’enfin une Colombe éclatante en lumière, symbole du Saint Esprit, parut sur sa tête pour l’assurer de sa présence et de son assistance. Et dès lors il reconnut sa esprit si éclairé de lumières, son cœur tellement fortifié, qu’il prit résolution de travailler de toutes ses forces pour le salut des âmes, et induire particulièrement son Diocèse à la vertu par son exemple et par sa parole.

[15] La nuit ainsi passée en prières et le jour venu Saint Didier se dispose à célébrer la Messe et présenter à Dieu ses vœux tant pour soi que pour le peuple à lui commis. La Messe dite, il entre en chaire, il commence à instruire et enseigner ce peuple, et fit une prédication si docte et si profonde, qu’il ravit tout le monde et d’où chacun sortit tellement édifié, instruit et satisfait: que ceux qui étaient aveugles en leur salut, en furent illuminés, les pécheurs convertis et les plus méchants et dépravés très sages et vertueux.

[16] Ce que ce grand Saint a toujours fait et pratiqué pendant sa vie, jusqu’à ce que Dieu voulant châtier la France de tant de péchés et désordres dont elle était remplie, il permit un débord étrange des Vandales par toutes les Gaules: et s’étant répandus en la France, la ville de Langres se trouva investie et assiégée de ces barbares, et quoi que son assiette naturelle et son enceinte de murailles fortifiées de bonnes tours et boulevards semblât assez considérable, néanmoins le nombre effroyable de ces tigres en rage et leur violence extraordinaire ayant fait perdre cœur aux citoyens et habitants, la ville avec eux fut exposée à la rage et cruauté de ces tyrans qui n’épargnèrent ni âge ni sexe à se saouler même du sang des innocents pendants aux mamelles de leurs mères et commettant toutes sortes d’atrocités.

[17] Les larmes de Saint Didier qui s’exposa comme une victime pour son troupeau, ses prières ni celles de tout son Clergé qui les assuraient que Dieu les punirait enfin de leur cruauté, puisqu’étant chrétiens ils étaient en sa protection, n’eurent pas assez de force pour fléchir ces barbares et inhumains à la miséricorde et apaiser leur rage: au contraire s’étant échauffés et animés davantage avec leur roi Chrocus, se saisirent de sa personne et commandèrent à un bourreau de lui ôter et la tête et la vie tout ensemble. Ce qui fut exécuté sur le champ le dixième des calendes de juin au grandissime regret de tout le reste des citoyens et fidèles serviteurs de Iésus Christ qui restaient en la ville.

[18] Mais Dieu qui témoigna le soin qu’il avait de son serviteur Saint Didier en prit bientôt vengeance: car ce misérable bourreau qui avait commis le parricide et qui avait souillé ses mains du sang de ce glorieux Évêque et Martyr, se trouva au même instant saisi d’une si grande frénésie et aliénation d’esprit, qu’après avoir couru les rues comme un possédé, sortant de la ville pour se rendre en son quartier, il se heurta si brusquement la tête contre la porte, qu’il y laissa sa cervelle, sa vie et son âme aux démons pour être associé éternellement à leurs tourments et à leurs flammes, et ressentir à tout jamais les justes punitions et vengeances de Dieu.

[19] Ces cruels bourreaux s’étant retirés avec leur roi Chrocus après avoir laissé la ville de Langres déserte et le peuple de reste en désolation: les fidèles que Dieu avait retiré et conservé, de cette oppression cruelle, s’assemblèrent pour rendre les derniers devoirs à leur Évêque et inhumèrent son corps en une petite chapelle de la ville qui était dédiée et consacrée à l’honneur de Dieu et de Sainte Marie Madeleine, portant sa tête qu’il avait consacrée à Dieu pour sa gloire, confession de son nom et conservation de son troupeau: en ses mains avec un livre ouvert et tout écrit de feuillet en feuillet, lequel était percé tout à travers d’un coup d’épée et du même glaive que le bourreau lui avait avalé la tête, et que le sang qui ruisselait de toutes parts à découler sur ce livre: néanmoins il ne fut pas endommagé et n’y eut pas un seule lettre effacée et se lisait aussi facilement que même longtemps après quand on a relevé son corps et enchâssé ses Saintes Reliques, ou a encore un et tiré d’icelui cet écrit miraculeux qui contenait ces mots: « ici repose le corps de l’insigne et admirable Didier Martyr de Iésus Christ qui fut en sa vie un Pasteur rempli de toutes les vertus tant morales que chrétiennes, un parfait Exemplaire de toute Sainteté. »

[20] Et ce qui est tout à fait prodigieux c’est que sur la sépulture de ce Saint Martyr ni en l’Église où est inhumé son corps, jamais il n’est entré personne qui rempli de témérité et outrecuidance, ait fait faux serment et se soit parjuré, qui soit sorti de la sans avoir ressenti et expérimenté la vengeance divine et les justes punitions et châtiments de Dieu. Si bien que tous ceux qui ont particulière dévotion à ce grand Saint, recevront par son entremise de très abondantes bénédictions de Dieu.