Hoarders and Hoards

The Material Collective’s special issue of postmedieval, Hoarders and Hoards: Responses to the Staffordshire Hoard, is now available. The journal has special relevance for me, and as we’ve been working on it, I’ve also been working through some stuff that I want to share.

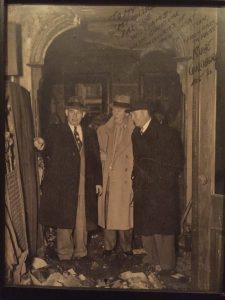

When I was a kid, I spent a lot of time at my grandmother’s house. Her late husband (who died when I was a baby) was a successful sports journalist in the 1940s, and their “den” had all kinds of amazing photos on the walls. Grandpa Joe with Babe Ruth, Grandpa Joe with Joe Louis, Grandpa Joe in the Collyer Brothers’ brownstone in New York.

Grandpa Joe in the Collyer Brothers’ brownstone (signed by Rube Goldberg).

From the earliest time I can remember, I was fascinated and horrified by the Collyer Brothers’ tale. The ultimate (original?) hoarders, they were both found dead in their Manhattan home, buried under mountains of stuff: stacks and stacks of newspapers, cardboard boxes, parts of cars and sewing machines, musical instruments, books, dressmaking dummies, a horse drawn carriage, broken things as well as whole. It took the police 5 hours to find the elder brother’s body, and they assumed the younger had fled the house until his body was finally found, no more than 15 feet from his brother’s. The police concluded that he had been crawling through a tunnel to come to his brother’s aid when the debris collapsed on him and he asphyxiated. My dad, who was always a fan of a good gothic story, loved the tragic irony of their demise and told me about it whenever I asked.

For the past few years, I’ve been spending a lot of time in my grandmother’s house again. When my parents divorced, my dad moved back in there with his mother, and when she passed, he stayed on. And so did his/her/our things.

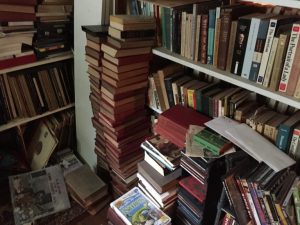

Dad retired a few years ago. Before that, he was a workhorse English Professor at a community college for more than 30 years. He taught a 5/5 load, offering English Composition every single semester, and I think he only had one sabbatical. Over those years of incredible service, he amassed a giant library. He also began collecting lots of other things: records, vhs tapes, bottles of hot sauce, postcards, a lighter with the name of every Irish pub he’d ever set foot in (and there were plenty). Not only that, but he was also unable to throw away any of his parents’ things: more books, more records, linen tablecloths, sets of china, furniture.

Dad retired a few years ago. Before that, he was a workhorse English Professor at a community college for more than 30 years. He taught a 5/5 load, offering English Composition every single semester, and I think he only had one sabbatical. Over those years of incredible service, he amassed a giant library. He also began collecting lots of other things: records, vhs tapes, bottles of hot sauce, postcards, a lighter with the name of every Irish pub he’d ever set foot in (and there were plenty). Not only that, but he was also unable to throw away any of his parents’ things: more books, more records, linen tablecloths, sets of china, furniture.

I’m both impressed and depressed by the vast quantity of things in the house. The sheer number of possessions is a graphic illustration of how privileged his upbringing was (as was mine, admittedly, though not quite to the same extent). Dad’s rebellion from the country club lifestyle was to become a poet and academic, and to spend whatever money and time he had on travel, good food, music—experiences over things, essentially. Ironic that the house ended up filled to the brim with the physical traces of those moments.

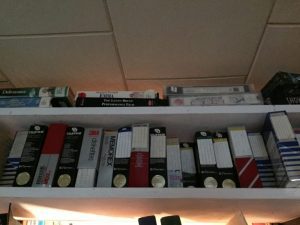

Ultimately, clearing out my dad’s house has been an important experience for me. Nostalgic and painful at times, cathartic at others. As I’ve been wrestling with something like a

5″ inch floppy disks of his first book on shelves that reach the ceiling.

mid-life crisis, I think a lot about the spaces I occupy and the things I choose to fill them with. As I sift through the detritus at my dad’s, I’m reconsidering all the stuff in my own house. (I’ve even been reading a bestselling self-help book (gasp!), The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up by Marie Kondo. Kondo’s philosophy of only keeping items that “spark joy” can be liberating, but it does also have a darker side. The book assumes that the reader starts from a place of economic privilege, and, in many ways, it encourages increased consumption.)

So, as many of us co-founders of the Material Collective were working on Hoarders and Hoards, I was digging through my own hoards and working through the human tendency to gather stuff. What’s that about anyway? Fear of death? Paralyzing nostalgia? Fear of change? Sure, all of that. At the end of the day, though, more stuff won’t resolve anything. I say, give up the meaningless stuff, save a few keepsakes, and live free while you can.