Barbara Crostini • Uppsala University/Newman Institute

Recommended citation: Barbara Crostini, “Gypsum and Mortar: Constructing Byzantine Builders and Craftsmen between Late Antique Practice and Medieval Exegesis,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.61302/IUSJ6602.

Per nonno Attilio, stuccatore

My grandfather was a plasterer. A framed photograph conveyed his life to me. In it, he stood before the stucco-work fence of our Liberty-style home (built in the Italian version of Art Nouveau in the 1920s, Fig. 1), posing in his work-clothes, a paper hat, and a trowel in his hand. He was short and strong. His craft required precision and courage. My father used to say he had no fear of heights when he climbed scaffolding to decorate stucco ceilings and outer cornices of buildings. This memory of him motivated my writing for this topic, a history of the working class.

Fig. 1. Entrance of a Liberty house with stucco work, c. 1920s, Rome. Photo: John Moir.

From this point of departure, my interest in this essay is turned to plasterers and their tools, more than to their finished products. The people who produced ornate architecture or frescoes, which are techniques that require the making and application of surfaces made of gesso, are hardly ever mentioned in art history books.[1] Lime burners, lime transporters, lime mixers and the tools for the application of quicklime – an active chemical substance that needs careful handling – are seldom highlighted despite their incredibly long pedigree in the history of making art.[2] Through inscriptions and images, I assemble here the evidence for these workers and trace for them a history from the beginnings of Christianity into the Middle Ages where their specific profession walks into the limelight.

The study of plasterwork is a recent development in art history. Studies analyse both the finished products, monumental or fragmentary, and the chemical composition of the materials. In this essay, I will not make this kind of analysis nor use the terms for the materials in a strictly technical sense, even though the composition of the plaster and the proportion of lime, gypsum, and sand (or other binders) in it are important evidence for mapping the spread of the techniques and the relation between different workshops. Both stylistically and technically, scholars have noted the Eastern origins of the medium.[3] Some have even postulated a continuing contribution of Syrian workmanship in eighth-century Italy.[4] This trajectory sketches a path that finds some confirmation in this study, which considers evidence of named plasterers at Dura Europos on the Euphrates, one of the earliest extant monuments of early Christian art.

One topic that receives some attention in current scholarship is that of the extent of the plasterers’ job. Overlap with activities such as woodcarving and masonry building, as well as fresco painting, are considered likely, even though the evidence is not as firm as one might wish.[5] In this essay, I follow this intuition and expand it with evidence of the organization of builders’ associations that witness to the commemoration of builders, including plasterers, in late antique inscriptions and Byzantine images. Moreover, I suggest a further connection between military service and building work,[6] which included the completion of cultic buildings. In particular, centurions were involved in the system of building supplies by liaising further afield for the quarrying of marbles and the overseeing of the transport operations carried out by the military themselves.[7] This involvement explains the extensive networks criss-crossing the Roman Empire from the Danube to Mesopotamia. From this material perspective, passages such as Luke 7:5 can be interpreted less spiritually or metaphorically than currently envisaged. In Luke’s Gospel, the Jewish community of Capernaum acknowledges that the local centurion deserved to be helped by Jesus “because he loves our nation and has built our synagogue” (Lk 7:5). Paula Fredriksen interprets the passage as offering “an example of the god-fearer-as-patron”,[8] overlooking the simpler option that the centurion was a builder and raising him to the loftier rank of being the (wealthy) sponsor of the enterprise instead. Despite looking at the building itself, Runesson and Cirafesi make the same abstracted assessment of the centurion[9]. However, taking this sentence at face value yields the most historically plausible interpretation, namely, that the centurion’s military function in the province of Palestine doubled as that of builder. More specifically, the centurion acted as master builder giving orders to construct the synagogue at Capernaum, as his dialogue with Jesus demonstrates.

A theologian’s bias is matched by art historians’ preference for describing iconography and style of the master artist, divorcing that persona from the hand of the artisans executing the work. Academic disciplines reinforce each other in this way to construct aloofness.[10] While the neglect of stucco production has at its root this preference for conceptual topics that reflect exegetical elucubration, its rediscovery shifts the discourse to more concrete topics, such as the work of the craftsman. Rachel Danford significantly defines stucco as “an interstitial medium that falls somewhere between conventional categories of painting and sculpture”.[11] The same word, ‘interstitial’, is used by theologians Mauro Pesce and Adriana Destro in describing how Christianity functioned within society at its origins, filling the cracks in-between the strata of society, entering the homes (oikoi), and cementing together different actors on the social scene.[12] The coincidence of this descriptive terminology is not superficial. It reflects a preference for the ambiguous and the unglamorous that is capable of conferring to primary matter and workforce an appropriate dignity and status. I therefore argue here that, through the ‘humble’ medium of plaster,[13] craftsmen in all ages left a remarkable contribution to the making of the church, both as a building and as a social institution.

With this aim of integrating plasterers more fully into the history of art, I highlight their critical importance not only as individuals, but more specifically as organized collectives.[14] This article thus reads scenes of work not as mannerist genre scenes,[15] nor as straightforward biblical illustrations (most commonly associated with the Tower of Babel, as we shall see). Far from epitomizing the over-ambition of the working classes to partake in elite culture, the visual manifestations here analysed acknowledge the determinant role of the plaster-makers and builders, thereby opening a space for appreciating the workforce that drives society’s cultural achievements. Starting from two rare Byzantine manuscript illustrations of builders at work, I work towards an interpretation of these images by contextualizing their activity within the diachronic reality of plasterers and their corporations. When returning to the manuscript images, it will I hope become clear how they emerge from a tradition of celebrating this trade, and how their inclusion within luxury productions of Greek Psalters marks a long-standing continuity that acknowledges the plasterers’ contribution to the making of the church, ancient and modern.

Two Byzantine illuminations

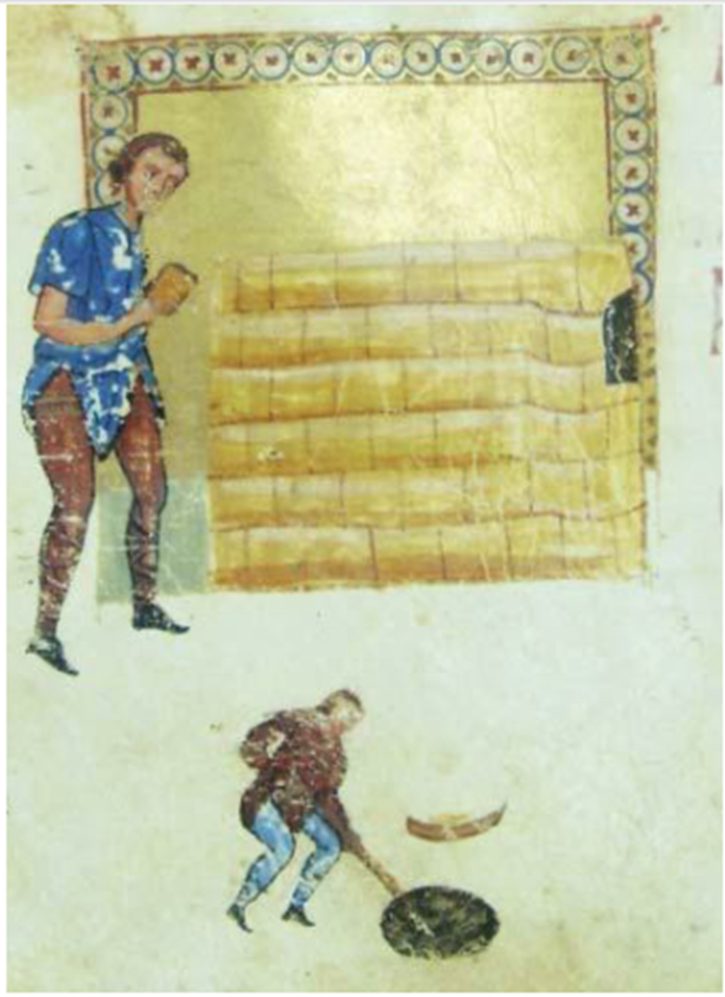

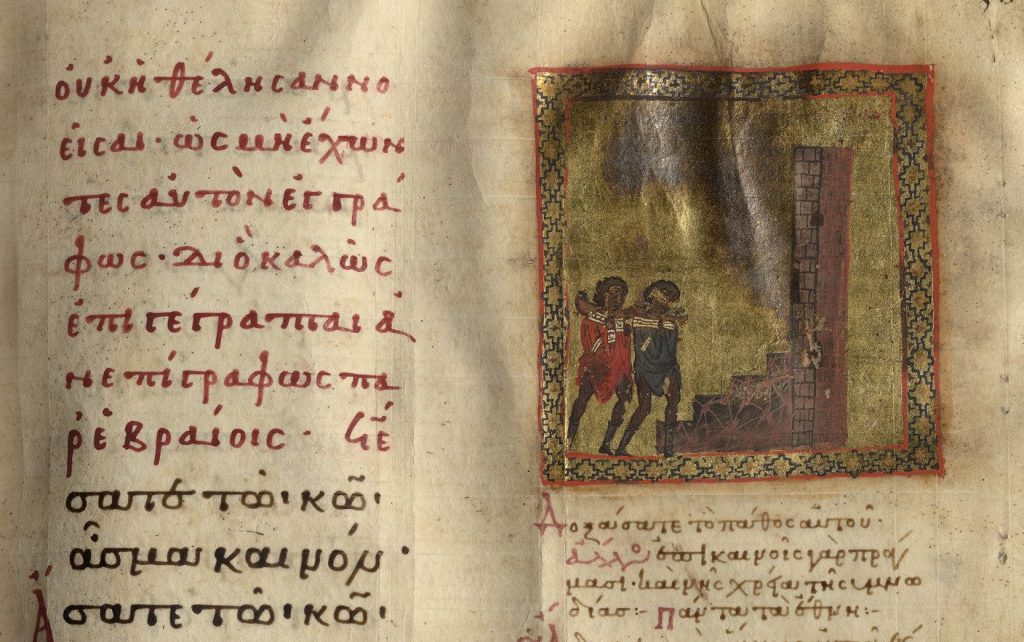

Compared to the considerable documentation about builders and their guilds that comes from Roman catacombs and late antique inscriptions, representations of builders in Greek manuscripts are rare, and do not benefit from a wider framework in which to be understood. Two eleventh-century Greek manuscripts of the Psalter, related productions probably from the same center, are exceptional in offering miniatures of builders: Jerusalem, Hagiou Taphou 53, fol. 138v (Fig. 2)[16] and Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vaticanus graecus 752, fol. 300r (Fig. 3).[17] Both illuminations are appended to Psalm 95 (96), a psalm of praise that begins “O sing to the Lord a new song,/sing to the Lord all the earth!”, rather than where we would more likely expect them, at Psalm LXX 126 (127):1, “Unless the Lord builds the house,/ those who build it labor in vain” (Ἐὰν μὴ κύριος οἰκοδομήσῃ οἶκον, / εἰς μάτην ἐκοπίασαν οἱ οἰκοδομοῦντες αὐτόν). As we will see, the caption to the Vatican image alludes to this verse. Why, then, are they placed at Psalm LXX 95, and what do the images really show? Both miniatures depict two men against a gold-leaf background, yet their spatial composition and details reveal different approaches (and perhaps different models).

Fig. 2. MS Jerusalem, Hagiou Taphou 53, fol. 138v (11th cent.).

Fig. 3. MS Vaticanus graecus 752, fol. 300r (11th cent.). Published by permission of the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

In the Jerusalem manuscript, the miniature is partly framed by a decorative band around the square of gold background and partly executed in an open field by using the parchment background (Fig. 2). The two men are wearing similar clothing, the colours of top and bottom garments reversed between blue and brown for shirt and leggings; the top man with short and the bottom with long sleeves, and both with black pointed short boots for shoes. This specularity discourages from drawing hierarchical conclusions from the different proportions of these figures: the man next to the wall at the top is double the size of the worker in the margin below. The latter might be thought an addition were it not that both figures use the plain parchment as background and are stylistically similar, represented in three-quarter view and similar posture. The wall of honey-coloured ashlar masonry dominates the upper half and seems to bend towards the right end, where it features a small window as a black square opening, reminding one of a hermit’s cell. The builder who stands next to this wall seems to step aside from it while he carries a brick in his right hand, which he deliberately raises towards the wall itself. A square of pale green grass behind his left leg may indicate that the wall is not finished, but the builder peacefully contemplates his achievement, unhurried towards its completion. His companion below is more physically engaged: he leans forward with his weight and bent knees with a tool composed of a stick, with, presumably, a spade-like end, although this part is invisible, hidden in the black pit dug in the ground before him where he is mixing mortar. The round lid visible just behind the pit shows an effective 3D rendering of its depth.[18] The mixing of lime or mortar was a skilled and important part of the building process, and it was often singled out for representation as we will see below. This particular miniature also had a prolific progeny in Slavonic manuscripts, which I will not investigate here.[19] The detail of the cut-out pit and its lid brings home the realism of the scene despite its otherwise idealized, almost de-materialized appearance. The pair form a collaboration in building the wall, putting together bricks and mortar. The majestic wall is greater than their efforts, being the house of God where praise to him can be given; at the same time, their ongoing activity of building, displayed in the miniature before their result is achieved, is itself celebrated.

In the Vatican manuscript, the two men are more neatly enclosed in a rough geometrical frame with red borders enclosing the golden background (Fig. 3). They, too, stand in a three-quarter posture at the side of a built structure, this time a stepped building culminating in a tower-like element. Interestingly, their clothes are styled in the same way as those in the Jerusalem miniature, with a loose top that hangs longer in a point between the legs, with slits for the legs to be free to move, covered as they are in tight legging-trousers of a dark-brown colour. But despite the similarity in style and colour scheme, the clothes of the Vatican figures are bordered in gold around the neck and cuffs. Moreover, the contrasting colour of their tunics, one blue and one red, reflects the colour scheme of other depictions in this manuscript, particularly that of the group of the ‘sons of Korah’.[20] The two men are walking together towards the built structure carrying implements on their shoulder. Although flaking of the paint makes discerning what they carry over their shoulders difficult, we will return to this detail after examining visual comparanda. Here too the building activity is somewhat stylized and even idealized, yet the details are accurate and, if examined carefully, can tell us more about how these mason-plasterers contributed to the praise of God, and even why their activity, so displayed, is in need of affirmation and protection.

Builders’ Associations

Only the Vatican miniature contains a caption written against the gold background, now almost erased. It identifies the two men as “οἱ οἰκοδομοῦντες τὸν ναόν”, which we can provisionally translate as “those who are building the temple”. This caption allows us to locate these two men within an established group since Hellenistic times, that of the ‘oikodomoi’, with known Byzantine epigones in fifteenth-century Thessaloniki disporting noble surnames.[21] Oikos can mean house or household, but the term is often translated as ‘house of God’, which the word chosen for the caption (naon) underscores. Builders did not operate on their own but were grouped in associations that coordinated the workforce and that protected their rights. Hellenistic associations are now considered significant constitutive elements in the development of the Christ-cult movement which, as a grass-roots phenomenon, questioned social stratification and to some extent succeeded in revolutionizing it.[22] Although the evidence for builders’ associations has been gathered together with that of other professions,[23] this group has not been analysed as much as more privileged ones. It is also possible to connect this epigraphical information with other evidence of this activity from figural imagery and tombs.

In the first century, a guild of builders advertises itself on the side of an upper decorative moulding on a basalt block from Gadara in the Decapolis: “The guild of builders” (syntechnia oikodomōn, Συντεχνία οἰκοδόμων).[24] A contemporary papyrus from Arsinoites in Egypt reveals the foundation of an association of builders (oikodomoi) through the payment of an official charter, written by the services of a scribe (grapheion) for 10 obols.[25]

At Oxyrhynchus in c. 300 builders were pitched against (an association of?) weavers who claimed that a young man had been abducted by the builders unlawfully while being a weaver’s apprentice. The tone of the dispute is not calm; the young person feared being threatened into having to leave his profession as a weaver: “For they are eager to make this linen-weaver who is my client into a builder and are daring to commit a great injustice. They are tearing him away from the craft which he has learned. They want to teach him a different craft, that of the builders. He must be guarded in his wife’s house so that he does not suffer any violence by the builders [oikodomoi throughout this passage]”.[26]

The presence of this group as a distinct lobby in the urban community is attested by the inscription on a column in the marketplace at Magnesia in Caria, designating that spot as the regular meeting-place for the builders (oikodomoi).[27] An exalted civic and religious function is attributed to an association of craftsmen (koinon twn technitwn) at Amphipolis, Macedonia, in 85/84 BCE, where it was responsible for crowning the priests of Athena.[28] Builders and craftsmen (oikodomoi kai technites) are named together in a very interesting set of regulations added to the base of a statue, perhaps of Septimius Severus, at Sardis in the fifth century. Like modern trade-unions, these extended decrees show how the association provided a form of social security and oversaw problems such as illness and the honouring of commissions and contracts on time according to strict procedures, acting as a mediator between the state and the workers. The association has to swear an oath to the city’s magistrate to abide by these rules, being legally liable for its members.[29] Among these provisions are guidelines for safe-guarding the employment of a sick builder for a certain period of time or providing a substitute for him from the members of the association.[30]

In order to fulfil their function, associations drew from independent funds – thus relying on donations – that could in turn be destined for preparing tombs and associated memorials for both members and patrons. For example, an association of builders (collegium fabri) at Volsini in Italy elected its patroness in 224 CE by choosing a worthy widow, whose husband had been “a centurion of the first military unit in the legion (primipilaris) and … made it his practice to act towards our association with much love and affection”.[31] The distinguished representative role of this patroness, Ancharia Luperca, was further commemorated by a bronze statue of her and her husband, Laberius Gallus, erected in the association’s meeting-place (schola). This Italian document exposes the network of links between the corporation of builders and local magnates, including magistrates (Ancharia’s father) and military men (Ancharia’s husband). The latter exemplifies the extended tasks of a centurion, as in the passage of Lk 7 mentioned at the beginning of this article.

A common burial for members of the same association is attested in several examples from Lamos, Cilicia, dated between the first and third centuries CE.[32] Like Ancharia, the wise Metereine is recorded raising a tomb and associated altar “for the guild of workers” (synergion operarii, τῷ συνεργίῳ τῶν ὀπεραρίων).[33] The “sacred guild of marble workers” was to receive money from any fine payable by those who disturbed the burial of Polychronia and her husband: 1500 denarii, a sum equal to that owed to the city at the same time.[34] That builders’ associations (or guilds?) took care of their members even in death is further attested by two spectacular monuments from Rome: the hypogeum of Trebius Iustus and the mausoleum of the Haterii.

The Hypogeum of Trebius Iustus

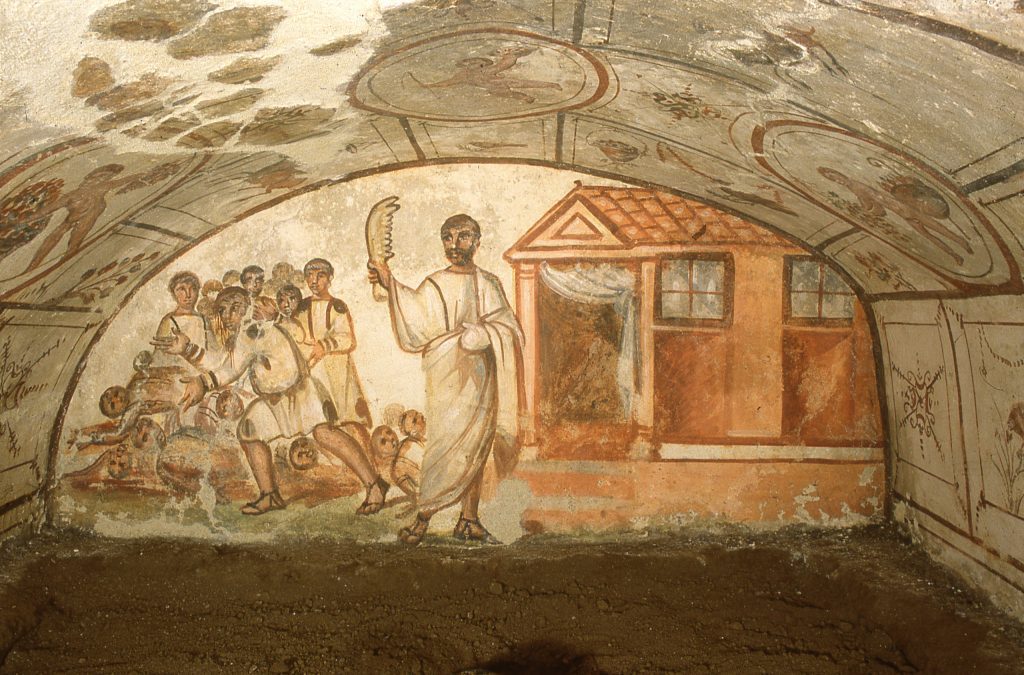

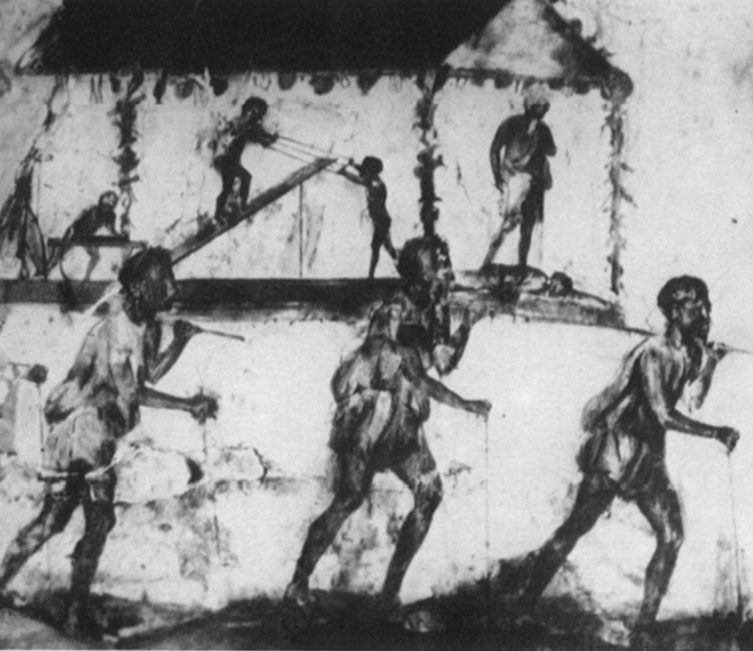

The hypogeum of Trebius Iustus, a fourth-century frescoed catacomb on the Via Latina, commemorates this young man who was, among other activities, a master builder, as the detailed scene with several workmen around a scaffolding clearly portrays (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Building scene, hypogeum of Trebius Iustus, Rome (4th cent.). After Fabrizio Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto,” in L’orizzonte tardoantico e le nuove immagini, corpus I, ed. Maria Andaloro (Milano: Jaca Book, 2006), 259-263.

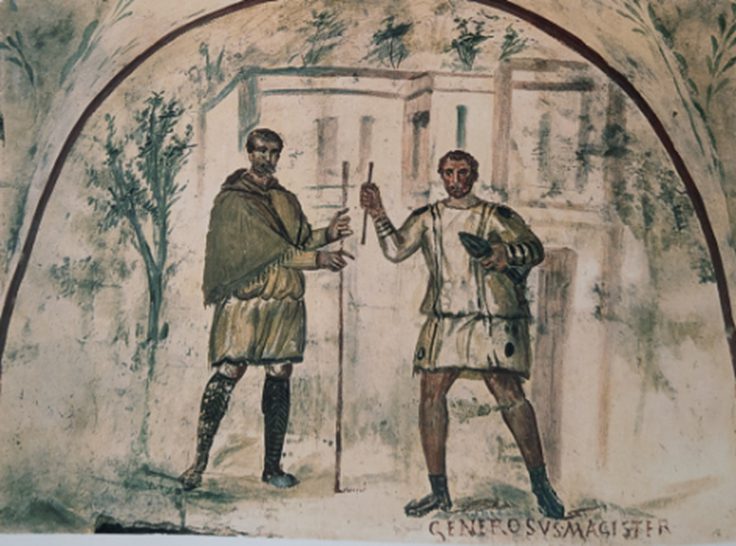

However, the loculi provided more space than what was needed for the designated members of his family, and one therefore wonders whether the choral scenes displaying several individuals should not be read more collectively than has hitherto been proposed.[35] The writing under the feet of the protagonist in a portrait niche just below the fresco of the building site identifies Trebius as master builder, adding the caption ‘generosus magister’ below him (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Trebius Iustus as ‘generosus magister’, hypogeum of Trebius Iustus, Rome (4th cent.) After Fabrizio Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto,” in L’orizzonte tardoantico e le nuove immagini, corpus I, ed. Maria Andaloro (Milano: Jaca Book, 2006), 259-263.

By these words, ‘generosus magister’, his generosity is immortalized. This quality may be understood in practical terms as sponsorship, but, in connection to the meaning of ‘magister’ as head of the workshop,[36] it more likely refers to his gentle disposition and parsimony with discipline towards his subordinate workers. A pun or double-meaning of ‘magister’ as teacher or model of behaviour may be also underscored by the learning aids depicted in the principal dedicatory lunette with inscription (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Central lunette with inscription, hypogeum of Trebius Iustus, Rome (4th cent.). After Fabrizio Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto.”

As his name tells us, Trebius was ‘Iustus’, a just man, and this spiritual virtue is manifest in the flourishing of his activity and in the fellowship and cooperation of those represented with him and likely buried there together (and/or thanks to him) in this tomb.

From this communal perspective, I would suggest reading the display scene above the lunette (Fig. 7) not as a family show of fortune, where mother, father, and son exhibit their wealth on an outstretched cloth, but rather as a donation scene within the guild of which Trebius was the head.

Fig. 7. Donation scene with Trebius Iustus, Horonatia Severina, and another man, hypogeum of Trebius Iustus, Rome (4th cent.). After Fabrizio Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto.”

Thus, the gold of Trebius and, possibly, of his mother Horonatia (sic) Severina, is displayed for the benefit of the association of builders as a whole. The key to this interpretation is the canvas on which the precious objects are displayed: it is a white cloth with four black circles at each corner and an ornamental black rim, a pattern matching the clothes of Trebius and of the person standing to his left. This outfit, adapted as a shorter garment in the master builder scene to identify Trebius, is clearly a costume of sorts, perhaps the association’s uniform. The matching display cloth appears to have a ritually designated function that would not be necessary if the wealth simply belonged to the titular family. A comparison with the tunics worn by a crowd in the scene from another set of catacombs of the Via Latina, identified as Samson and the Philistines (Judges 15:14-17) (Fig. 8), shows that the garments with the four black circles are not unique to the persons singled out in Trebius’s tomb.[37]

Fig. 8. Samson holds up an ass jawbone, note costume of the crowd fighting against the Philistines, Via Latina Catacomb, Rome (4th cent.). Published with permission of the Pontificia Accademia di Arte Sacra.

The connection with this other catacomb is also illuminating with respect to the designation ‘Asellus’, meaning ‘donkey’, found both in the masculine referred to Trebius Iustus himself (Trebio Iusto signo Asellus), and in the feminine, referred to a ritual libation to the dead (Asellae piae zeses). Thomas Mathews noted how the donkey functioned as a marker of identity in the Via Latina catacomb that includes the scene with Samson and the Philistines, in which Samson is holding up the jawbone of an ass to grant victory to his men (Judges 15:19). As depicted on the catacomb fresco, his men are dressed in garments marked by four black circles, perhaps marking builders doubling as soldiers – or vice-versa.[38] Mathews also remarked on the other donkeys in the nearby paintings: the scene of Balaam and the Ass (Num 22-23) and that of Abraham’s sacrifice, where the ass carrying the wood is given a full space to itself.[39] Thus garments and donkeys connect these sepulchral spaces, and the key to their being read as tombs destined to an association of builders seems confirmed by an independent inscription from the catacombs of Saint Valentinus on the Via Flaminia, where another Asellus is named on a slab bearing the drawing of an axe and dated to 336 CE (dulcissimo filio Asello).[40] The donkey thus likely functioned as an emblem for this group (signo in Trebius’s inscription), connected with building activity, likely not devoid of pointed self-irony (we still use comparison with a donkey to allude to exceptionally hard manual labor).[41] This beast must have also aided transport during building work, even though extant illustrations depict horses and oxen strapped to carts.[42] There is no doubt, then, that Trebius Iustus was as ‘Christian’ as his neighbours.[43]

This way of reading the evidence, not as a proud display of wealth per se, but as a token of a larger benefaction to society, is in line with the hermeneutics that Lauren Hackworth Petersen applied to the shipbuilder’s stele from Ravenna.[44] Like Trebius Iustus, Longidienus was both the patron of the stele, where he is depicted with his wife and two other of his freedmen, and the person represented at work on a ship at the bottom of it, as specified by the inscription. Petersen confirms that “he also depicts himself, both visually and verbally, as hard at work in casual tunic attire … not only as the overseer of his business enterprise, but as actively engaged in it”.[45] In both cases, civic pride in being “active members of their community’s workforce and contributors to the economy” is reflected in the communal nature of their monuments, which display a specific attitude in the freedom granted to former slaves and co-workers.[46]

The Haterii Mausoleum

A similar reading could be applied to the grander mausoleum of the Haterii, a family of builders who displayed their activity in a monumental tomb along the via Labicana in the second century CE, whose marble reliefs are now preserved in the Vatican Museums.[47] While Trebius’s business could be described as medium to modest, the Haterii may be compared to today’s builders of skyscrapers, being entrusted with the erection of imperial monuments such as triumphal arches and obelisks. Their wheel-powered crane is proudly featured at the side of their tomb relief. Yet the inscription again specifies that it is the families’ ‘liberti libertaeque’ (male and female freedmen) that find place in the mausoleum, which is therefore not an advertisement for the family itself, nor even for its business, but an enlarged celebration of its ‘familia’, in this case large enough not to need connections with a wider network of dependants (as the Ravenna stele). It was these freedmen who are also represented in the tomb reliefs, surrounding their dead patroness (Fig. 9). As Trimble perceptively interprets the monument, the crane functioned “as a symbol of transformation, … [and] an engine of social transformation: several of its workers wear the pileus, the conical cap signifying manumission, and they may have been freed by will”.[48]

Fig. 9. Tomb of the Haterii, the familia surrounds their dead patroness, Vatican Museums (2nd cent.).

Returning to our pair of workers in the Byzantine illuminated Psalters, we can now read their sumptuous, colour-coordinated clothes, at first seemingly incongruous with their activity, as pointing to their ceremonial belonging to a lay association connected with building work. The filing of the Vatican duo recalls the ceremonial parade on a fresco from Pompei, where three builders carry their tools on their shoulder against the background of a building site (Fig. 10).[49] In particular, the robes of the builders in the Vatican miniature would suit the mode of a ‘défilé corporatif’, given the ornamental quality of the gilt rims. It is possible, then, that the Psalm the builders are associated with could work as their processional hymn or anthem. During processions, people carried items significant of their trade. What were the Vatican builders carrying and can we identify their precise activity by analogy with other ancient images of builders?

Fig. 10. Procession of the corporations, Pompei, after Jean-Pierre Adam and Pierre Varène, “Une Peinture romaine représentant une scène de chantier, ” Revue Archéologique n.s. 2 (1980), 213-238, fig. 18.

Pairs of plasterers

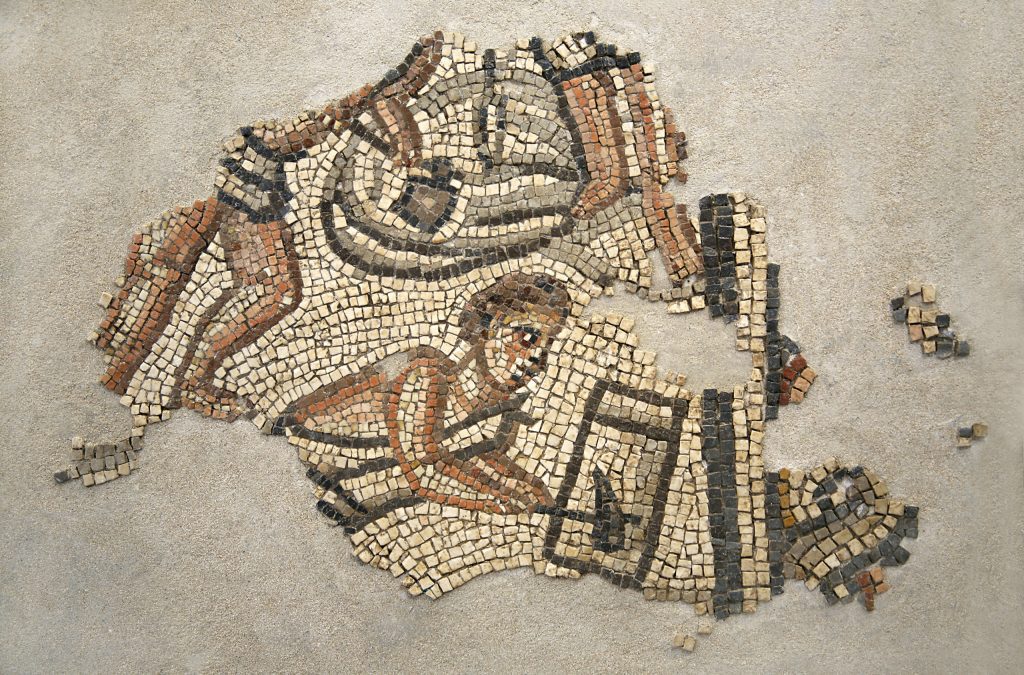

Due to flaking, it is no longer possible to read with precision the objects carried by the Vatican workers (Fig. 3). On the other hand, the Jerusalem manuscript’s pair (Fig. 2) makes their activity clear – they are building the wall so prominently displayed in the background – while stressing two instruments of their work: the bricks and the mortar. It is notable that the phase of mixing the mortar is often chosen for display in ancient representations. In the tomb of Trebius Iustus, the man mixing is standing to the right of the composition, handling a squarish spade with a curved blade over a grey mound of lime piled on the ground (Fig. 4). Behind him is what seems a large dish on a table under the scaffolding, where he would transfer the lime mixture to be taken up in portions to the builders. The person climbing the ladder in fact is carrying a similar oblong dish over his left shoulder, leaving his right hand free to grasp the rungs for balance. Bisconti notices that another tool may be poised on the side of the dish, perhaps a long kind of spatula to help pour out the mixture at the top of the wall.[50] A similar kind of square-tipped hoe is manoeuvred by the half-preserved craftsman mixing mortar in the mosaic from the synagogue at Khirbet Wadi Hamam, from the mosaic decoration of the floor (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11. Floor mosaic, Synagogue at Khirbet Wadi Hamam, 6th cent. Ensemble. Courtesy of Uzzi Leibner, Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Photo: Gabi Laron. Overall view.

Fig. 12. Floor mosaic, Synagogue at Khirbet Wadi Hamam, 6th cent. Ensemble. Courtesy of Uzzi Leibner, Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Photo: Gabi Laron. Detail.

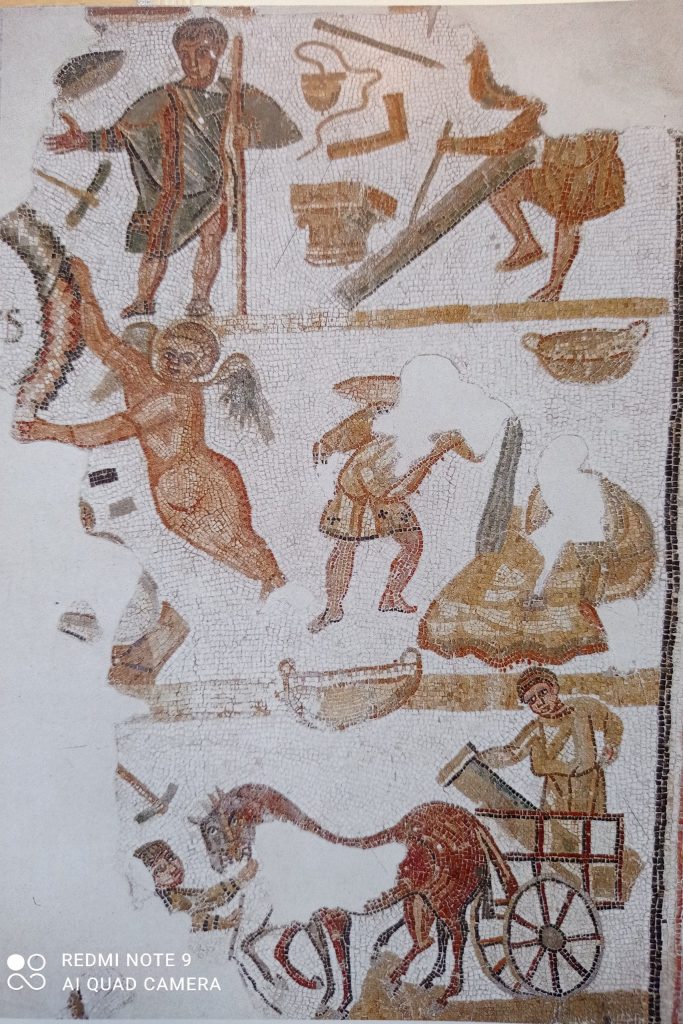

Rows of white, grey and black tesserae well delineate the layers of viscous substance in the lime mixture, while an assistant brings water in a jug to adjust the process of slaking.[51] Even the sixth-century church mosaic from Oued Rmal in Tunisia, where the building vignettes are stacked vertically on three planes, dedicates the middle level to the mixing of mortar (Fig. 13), similarly displaying a man with a spade-like tool leaning toward a mound while another pours water on it (or possibly more lime from a sack).[52] This operation was a specialized and delicate one, since it could initiate a chemical reaction and even lead to an explosion. Vitruvius gives advice on how best to perform slaking in order not to leave bits of unburnt lime that could blister when applied to the wall: “When such bits complete their slaking after they are on the building, they break up and spoil the smooth polish of stucco”.[53] Such care was particularly important in the preparation of surfaces to be frescoed.

Fig. 13. Mosaic from the church at Oued Rmal, Tunisia, now in the Bardo Museum, Tunis: from the top: builders with measuring instruments and tools; a pair of builders mixing mortar; a column is transported in a horse-drawn chariot, 6th cent. Photo: Robin M. Jensen.

The other key instrument related to plastering as well as masonry building is the trowel. In front of the lime-mixer in the synagogue floor is a half-preserved man holding a pointed trowel to the side (Fig. 12),[54] while Trebius Iustus and his co-worker are each handling a pointed trowel to fix the mortar at the top of the wall (Fig. 4).[55]

Of 183 builders’ tools designs from the Roman catacombs, 62 represent an axe (Id9.1-62), 21 a hammer and chisel (Id3.1-21), 18 only a hammer (Id4.1-18), 28 only a chisel (Id5.1-28), 13 the measuring foot (Id6.1-13), 12 squared measures and spirit levels (Id7.1-12), 3 spades, compasses and other unidentified marks (Id8.1-3), and another 3 trowels, ladders, and other building materials (Id10.1-3). Additional trowels are also found together with an axe (cf. Id9.42 and Id9.47).[56] The memorial inscription for a certain Constantia depicts a trowel between two hammers, typical of a faber coementarius, though it was unlikely to be her own occupation given her gender (Id10.2). Perhaps she was one of those women who sponsored builders’ associations, which we have seen was quite frequent, and the combination of hammers and trowel the association’s badge.

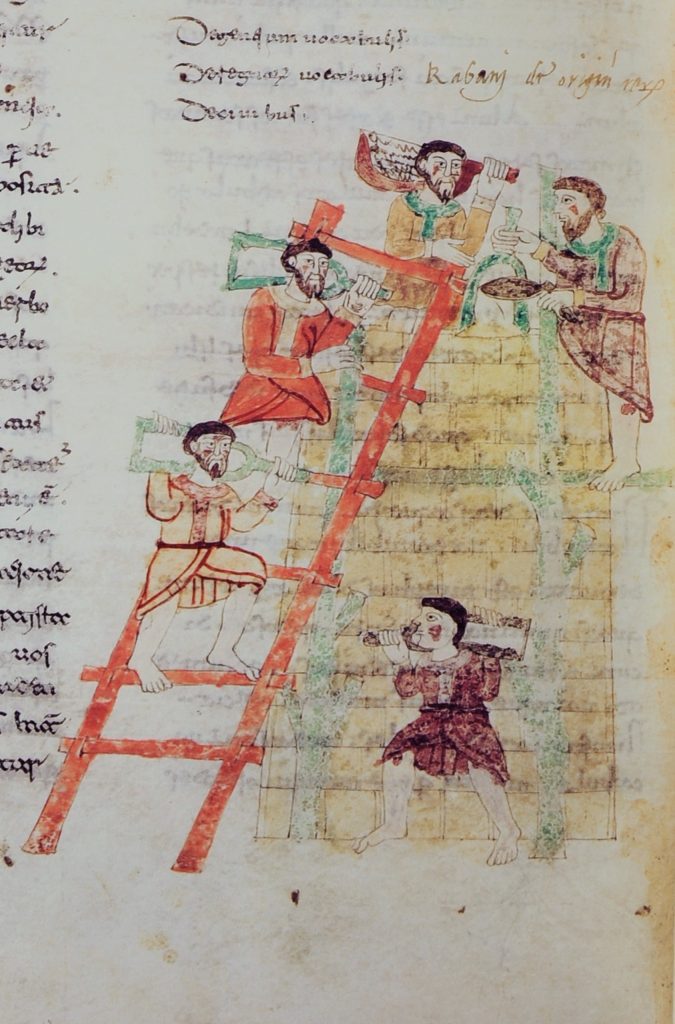

A medieval illumination of the building of the tower of Babel, the subject identified for the Hamam synagogue’s mosaic, shows several men ascending the ladder stationed around the tower. They are carrying portions of slaked lime in oblong spades with a long handle for ease of transport, corresponding to a modern hod. This miniature is found in Rabanus Maurus’s De universo, book XVI, in the only extant illustrated manuscript of this work, MS Montecassino, Cas. Lat. 132, fol. 394b (Fig. 14), copied in c. 1023. The U-shaped tool with a handle used by the mason standing on the scaffolding to reach the top row of the brick-laying probably also represents a hod from a section view, while the mason empties its contents with the help of a long-shaped trowel or spatula in his left hand.

Fig. 14. Hrabanus Maurus, De universo, Book XVI, builders construct the tower of Babel, MS Montecassino, Cas. lat. 132, fol. 394b, early 11th cent. Photo: Roberto Mastronardi. Published with permission of the Archivio di Montecassino. With thanks to d. Mariano Dell’Omo.

The same biblical scene represented in the twelfth-century mosaics of the Cappella Palatina, Palermo, also offers a representation of lime mixing in the foreground, as well as showing a lime kiln top left and builders with different tools in their hands on the tower itself (Fig. 15).[57]

Fig. 15. Cappella Palatina, Palermo: Building the Tower of Babel, 12th cent. Photo: Beat Brenk. Published with permission.

In this mosaic, however, the lime mixture is made in a raised, fountain-like trough, and the spade-like hod is used only to transfer the mixture to a basket with a rigid handle that is then hoisted with a rope up the tower. This kind of basket, but without handle, is visible in another twelfth-century Byzantine manuscript illumination of the Tower of Babel, in the illustrated Octateuch Vaticanus graecus 746, where it is left standing on the ground, and also dropped upside-down from a height visualizing the catastrophic end to the tower’s enterprise.[58]

The oblong shape that appears over the left shoulder of the red-dressed man in the Vatican miniature, and protrudes beyond his right shoulder, could be one such lime-carrying dish or hod (Fig. 3). While the tools from the Italian area (Montecassino, Palermo) seem made of wood, the shape of the vessels carried by the workmen in the Vatican miniature may suggest that they were made of pottery. Although, unlike trowels and hoes, precise archaeological finds for this object are lacking, the story in the miracles of Saint Photeine could indirectly confirm the hypothesis that Byzantine hods – whether shovel-shaped or basket-shaped – were pottery items. In that text, a workman who falls off the scaffolding is saved, but the trough of mortar he was carrying is smashed to pieces.[59] It is impossible even to guess what the other, blue-dressed worker in the Vatican miniature is carrying, perhaps the same type of container or an axe or trowel. If the building they are constructing is the one represented in the same miniature, analysing it should provide us with further information about their activity.

Ashlar-like brick and plasterwork

The tower to the right of the pair of builders in the Vatican manuscript is an odd construction (Fig. 3). Nothing indicates that it is a free-standing, external structure or that it should be interpreted biblically as the tower of Babel. Indeed, the negative connotation of that biblical episode, while providing the perfect excuse to display a working building-site, casts these images of builders in an unnecessarily problematic light that the sheer delight in detail of their early Christian forebears did not share. In particular, one wonders whether the synagogue’s scene needs to be interpreted this way, when the Tunisian church’s mosaic does not.

The stepped structure the builders in the Vatican miniature are walking towards is composed of four ascending steps culminating in a fifth that shoots up vertically disproportionately higher, so high that it could not be climbed on. While the visible side of the lower steps is coloured reddish-brown and presents veining in regular star-shapes that imitate a marble surface, the tallest step/tower is divided vertically into a section in ashlar bricks, outlined in black ink from top to bottom on the left half, and a reddish-brown right half, probably also composed of bricks. It is possible that the black line of bricks is a later repainting of the miniature. Thus, the structure presupposes two types of plastering work: for the steps, a plastering of the surfaces so as to imitate marble, while for the tower the masonry work that imitates ashlar with regular bricks.

The symbolic significance of ashlar constructions as a civilizing token cannot be dealt with here, except to say that masonry so constructed was considered particularly apt for the house of God, and was used among other things for Herod’s temple. But the tradition of ashlar construction goes back much longer. The palace of Knossos at Crete, where the Minoan civilization flourished between 2000 and 1500 BCE, is both an outstanding example of construction in ashlar masonry in limestone and the first successful experimentation with fresco painting, some of which imitated stone surfaces.[60]

While it is possible that the stepped structure in the Vatican Psalter was made of quarried marble, comparison with other images in the same book argue for this to be faux-marble created by painted stucco. At fol. 94v, for example, a similar construction made of porphyry-looking steps and a grey-green veined column at the top of which is the bust of a saint suggests that such devotional installations were created within a church space rather than in the open air and used faux-marble, makeshift columns.[61] Evidence of stucco capitals is also widespread, even though it is not possible to say whether any were used on free-standing rather than structurally integrated columns.[62]

While tools to cut, incise, and hammer could be equally employed by workmen as by marble cutters, sculptors, and inscription carvers, trowels are specific to plasterers and masons building ashlar-stone or brick walls.[63] It would seem, then, that the latter two activities are singled out as distinctive of the workmen represented in both Psalters, those deemed appropriate to celebrate God as proclaimed in the song of Psalm LXX 95 (96).

Marble… or painted plaster? “Masonry style” and the marmorarii

Commenting on a famous passage by Vitruvius, Fabio Barry comes to the conclusion that what the ancient architect called crustae marmoreae were more likely marbleized coatings than marble veneers. The passage reads as follows: “The ancients who first used polished surfaces [expolitiones] originally imitated the variety and juxtapositions of crustae marmoreae and thereafter the various combinations of cornices and ochrish bosses”.[64] Barry argues that since there are no substantial remains of marble revetment, Vitruvius must have meant the faux-marble produced by painted plaster, a point underscored by the imitation process referred to in the passage. Further, it may be surmised that, though explicitly mentioning only faux-revetment, Vitruvius had in mind the faux-ashlar technique that characterized the Pompeian First Style, also called ‘Masonry Style’ to describe its main characteristic, namely, that of decorating interior walls by painting colourful patchworks of stylized masonry blocks on plaster.[65]

Barry cites a Hellenistic text that describes (and prescribes) the ‘Masonry Style’, written as a contractual memorandum by the Alexandrian painter Theophilos for the House of Diotimos at Philadelphia in the Fayyum (Egypt). The instructions do not mention any specific stone that needs imitating, but rather stress the ideal of ‘poikilia’ in the variety of colours and patterns that come together in one composition.[66] Such an explosion of colours and patterns was realized in the Chapel of the Red Monastery, as Elizabeth Bolman wonderfully details in her book.[67] Often, the painted imitation chose the rounded patterns of alabaster, as in the Great Temple at Petra.[68] The economic factor was not the issue, since some of the materials employed to produce the required effect and colouring on plaster were actually as expensive as raw materials from rock.[69] Availability, however, may have been a constraint so that the painterly imitation made available to a wider geographical spread a uniform aesthetic fashion.

Barry concludes that all the make-believe of the Masonry and First Style was an image not of what was but of what could be, and even though these painted reliefs could almost pass themselves off as plausible construction, they had no true referents in reality. They are “simulacra”, copies without an original. […] The representation of the wall is an idealization (even heroization) of its material possibilities, lifting the prose of construction into a creative dimension where it becomes a thing of poetry. Looking for real-world models is futile because the painted and moulded fiction of the architecture aims at the kind of wonder that was unavailable in actual construction.[70]

Barry’s considerations alter the status of the builder and plasterer from makers of practical solutions to creators of an illusionary, enhanced world. This inhabited world is, in turn, inspired by the natural environment, including stone, but re-interprets it and re-proposes it in a tamed, deliberate form after a lengthy and complex process of semi-industrial and artisanal production of materials and mastery of special techniques. Barry emphasizes that even the use of natural stone was bent to the needs of the particular taste and object, so that imperfectly veined stones were over-painted with the desired patterning.[71] This tension between the man-made and the natural –images not-made-by-hand (acheiropita)– lies at the heart of the theory of images debated in the iconoclast controversy.[72]

Reversing the relationship, then, between what is found in nature and how patterns and colour enter the inhabited world of humans, even the use of real marble is interpreted through the lens of its intended effect. Partly influenced by a fantastic understanding of the process of marble formation as the conglomeration of water from the ocean, the meaning of ‘mar’, the sea, and ‘mar-mar’, indicating the movement of agitated waves, transferred to ‘marmor’ as the rock carrying these effects on stone. The Greek verb marmairein, to glisten, carried both marble’s shining qualities and the expected movement of its stripes into producing the effect of church floors described as places of illusion, where one can ‘walk on water’.[73] From this perspective, one may revise the understanding of the designation of marmorarius, narrowly understood as stone-cutter, to include a craftsman who produces this illusion, whether through marble or through imitative crustae marmoreae.[74]

None of the five marmorarii inscriptions in Bisconti’s list have tool drawings attached.[75] One commemorates Silvanus (If1.1). Another has a heart-shaped leaf to the right of an inscription in Greek: Aurelios son of Agathias, Syrian, marmararios (μαρμαράριος) (If1.2). A third specifies that the marmorarius is ‘Puteolanus’, presumably not a proper name but an inhabitant of Pozzuoli, the place where the prime material from the volcanic rocks was extracted for the making of cement (puteolana pulvis) (If1.3). The following two inscriptions are incomplete. One of them is not on marble, however, as all the previous ones, but on a fragment of plaster. This evidence supports the hypothesis that the job of the marmorarii was not (exclusively? primarily?) cutting and shaping marble, but rather plastering and decorating surfaces with illusionistic veneers.

Additional literary sources may strengthen this hypothesis. The healing of Leontios by the wonderworking martyr Thekla of Seleucia describes an on-the-job accident of this non-Christian (perhaps Jewish?) artist and his fellow-workmen: they all fell from the scaffolding when working high on the walls. Everyone else died, except Leontios, who was lucky to survive but had broken his leg until he made the journey to Seleucia and was healed at the shrine of Thekla.[76] The Greek text is written in a very literary style that chooses language carefully (and complicates the plot with its undertones). In referring to Leontios’s profession, his ‘techne’, it specifies that the beauty of the place (to kallos) was the result of the work and effort of his hands (τῶν ἐκείνου χειρῶν ἔργον καὶ πόνος). His decoration of the walls included ‘marbles and stone slabs’ (μαρμάρων τε καὶ πλακῶν), a duplication that may indicate a difference between marbleized areas and lower-wall stone revetment. He was also responsible for laying the floor, which in Antioch could be covered in mosaic, opus sectile, or plastered. The episode is not only one of healing, but one of conversion, revealing the multi-faceted activities and dangers in the life of a (named) artist.

In an encyclopaedic article on named artists in Byzantium, Anthony Cutler observes that ‘[w]all painters and mosaicists … are more widely celebrated … than illuminators and other craftsmen’.[77] Many examples in his list support this statement, with an overwhelming majority of ceilings and floors from Palestine, Jordan, Southern Italy, and, later, from the Balkans, revealing named individuals.[78] Among them, the ‘marmaras’ named in the decoration of churches could include activities of plastering and decorating.[79] A relief from Sens shows the activities of wall-painting and plaster work being carried out simultaneously by a team of workers (Fig. 16).[80]

Fig. 16. Musée de Sens, relief of the stucco workers. (Inv. J. 115, coll. Société archéologique de Sens). Photothèque du CERP – Musées de Sens. Published with permission.

A named plasterer at Dura Europos?

Discovery of the method of production of quicklime and its implementation in building is located in the Middle East, in a region between Egypt and Palestine. “The plaster used by the Egyptians for their finest work was derived from burnt gypsum, and was therefore exactly the same as our ‘plaster of Paris’”.[81] The semi-ritual aspect of plastering walls that included sanitary value in keeping the environment aseptic and mold-free is dramatized in a passage of Leviticus (14:42-48), where a priest decrees whether a house can be dwelt in after carefully examining and testing the state of its plastered walls.[82]

It is not surprising, then, that the ruins of the early third-century town of Dura Europos on the Euphrates should reveal extensive use of plaster. Jennifer Baird notes that a prevalence of decorations in moulded plaster for door frames and cornices inside houses is “characteristic of the site”.[83] The limestone capping of the Dura plateau and the natural deposits of softer gypsum made primary material readily available.[84] Gesso reliefs[85] and sculptures were widely employed: a relief immortalized the central scene of the Mithraic altar while a gesso bust, likely of Emperor Commodus, was found near the Palmyra gate.[86] A charming plaster relief of Aphrodite apparently marked the entrance to the local brothel.[87] Smaller figurines, executed both as plasterwork and in terracotta, are also extant.[88]

The correlation between plastering and other decorative activities is captured by Grasby, who notes that “[m]arble waste (from inscriptions) was crushed and mixed with sand and slaked lime for the stucco coating of walls built of bricks and coarser stones. Cementum marmoreum or album opus, described by Vitruvius as “stucco, in the pride of its dazzling white”, provided a surface equal to marble in resistance to weather. It was the perfectly smooth ground required by artists for wall-painting, fresco and the rendering of fine detail.”[89] Many cultic buildings at Dura shared a taste for visual decoration executed as colourful frescoes, whether dedicated to Roman or local deities, Mithraic, Christian or Jewish worship. This unexpected uniformity of visual media across different faith groups has been justified by recourse to the same local workshop.[90] The narrow span of dating of the site’s last phase of decorations to a couple of decades in the second quarter of the third century, sealed by the destruction of the town by a Parthian invasion in 256 CE, means that the workshop was operative simultaneously across the board with the same basic agenda. Despite different outcomes in quality, the town’s attitude to cultic embellishment seems remarkably uniform, to the point that one might consider its having been orchestrated centrally, whether by local power or by imperial orders from Rome.

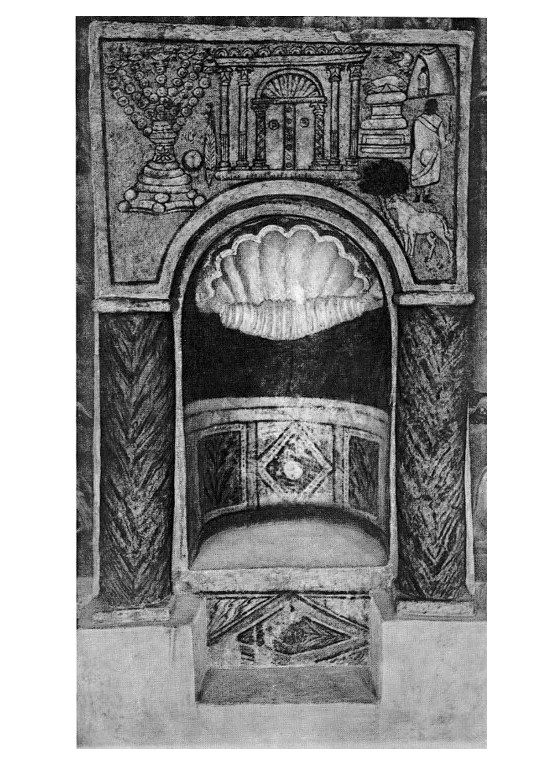

Besides the extraordinary fresco cycles in the large hall of the ‘synagogue’ (building U), a more modest programme is found in the smaller ‘Christian house’ (building Y), where paintings fill the walls of a small room (Room 6) that was purposely refurbished by being shut off the courtyard area at the same time as it was decorated (Fig. 17).[91]

Fig. 17. Niche with frescoes and faux-marble columns, Room 6 (known as the ‘Baptistery’) in the ’Christian’ building (X) at Dura Europos, Syria, ca. 320-340 CE, Yale Art Museum (image from Wikimedia).

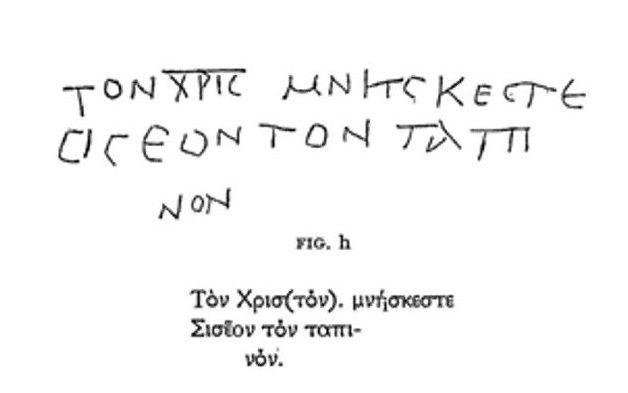

At the entrance to this room, a commemorative graffito is scratched deep into the wall.[92] Karen Stern describes it as follows: “The deeply engraved graffito, found to the left of the niche, acclaims Christ and reads, according to local orthography, ‘May you remember (Μνήσκετε) Siseos the humble one’” (Fig. 18).[93] Stern’s two-stepped reading reveals an uncomfortable juxtaposition between the invocation to Christ and the rest of the phrase. I would like to suggest that Siseos was writing his signature in this space as the plasterer and decorator, and that he marked this not with an explicit claim, but through a word-play present in the initial invocation of the name of Christ.

Fig. 18. Drawing of the Dura Graffito (after Kraeling, Christian Building, 95), graffito no. 17, fig. h. The abbreviated word is the second from the left, with the line drawn above it.

The words Christos and christes (plasterer) share a semantic link in the verb chrio (χρίω), meaning in origin ‘to touch lightly’ and then ‘to anoint, to smear’. Christ was the anointed according to the biblical symbolism of royal and prophetic unction,[94] while plasterers ‘washed or coated with colour,’[95] or alternatively with white.[96] On this interpretation, the graffito could read simultaneously ‘Remember the humble Siseos, the plasterer’, as well as something like ‘For the sake of Christ, remember the humble Siseos’. Moreover, the graffito abbreviates Christ’s nomen sacrum in an unusual way, using the first four letters (Chi, rho, iota, sigma) with a line above them rather than the first and last letters only.[97]

An invocation to Christ is present in a second inscription in the same room, where, however, the sacred name is written with the usual two-letter abbreviation, chi-nu (C[hristo]n), followed by iota-nu for Jesus (I[hsou]n), both in the accusative.[98] The invocation here is filled out by a rhetorical dative, ‘to us’, that makes it into a more complete prayer. The interpretation ‘Christon’ as the name of Christ in the Siseos inscription was made by analogy with this second example from the same room, despite these differences.

While variations in the spelling of the abbreviations for Christ make the analogy entirely plausible, the differences allow us to contemplate also another reading, in which Siseos was identifying himself as a christes (χρίστης, accusative χρίστην) which would characterize him as a worker in stucco. This rare word is attested in Hesychios’s Lexicon as synonym for koniatai (κονιαταί) and asbestarioi (ἀσβεστάριοι), both meaning ‘plasterers’.[99] The characterization of Siseos as ‘humble’ in the inscription further highlights his virtue, in line with later monastic practice of presenting oneself as unworthy of the task whatever the accomplishment.[100] Interestingly, the hagiographer of the Life of Thekla also presents the plasterer Leontios as possessing good moral qualities, which make him worthy of the attention of his lord, Maximinus. The first adjective used in his character description is chreston (χρηστόν, pronounced christon), a choice that may reveal a current pun between his trade and the good qualities associated with Christians. Moreover, the name of Jesus Christ himself was often spelt with an eta in Antioch and Egypt, as well as in the famous witness of Tacitus and Suetonius.[101]

The identity of Siseos, and perhaps that of his fellow graffiti-scratcher in Room 6, a certain Proklos, has never been discussed. Considered purely as commemorative writings, their ephemeral quality has impacted at most on prosopographical records. Kraeling considers ‘Siseos’ to be a typically Durene name containing a Semitic root that means ‘shining’, as the attribute of a god.[102] He relates it to the name of David’s secretary, Seisas, according to Josephus, Jewish Antiquities VII, v, 4, 110, although the corresponding passage of the Bible records this name as ‘Seraiah’ (2 Sam 8:17). The name Siseos with a slightly different spelling is found in a parchment record of the Clan of Zebeina,[103] ‘Seisaios’ (pronounced Siseos). In this list, the name is followed by the letters kappa epsilon, which could indicate his rank as a centurion.[104] If this interpretation is correct, rather than a mere coincidence of the same name, this record may be pointing to the same person who was both a ‘centurion’ and a master builder and plasterer.

Was this graffito the mark of an occasional visitor, or was it conveying a less informal message despite its unofficial character? Although both possibilities are open, the private, secluded character of this space within another building limits the occasions when passers-by could casually insert their mark on walls so carefully historiated. Such opportunities were not only spatially constrained, but also temporally limited, since the building did not remain for long above ground after its repurposing as a chapel. A global evaluation of graffiti culture at Dura also suggests that this medium conveyed important information. One of the earliest artist’s signatures is that preserved in the Dura Mithraeum, where the painter added his name to the wall: ‘Νάμα Μαρέῳ ζωγράφῳ’.[105] Mareos’s signature begins with the Mithraic invocation ‘Nama’, usually interpreted as a wish for salvation. Like the Siseos and Proklos graffiti, a statement of presence combines with a prayer. Moreover, Mareos explicitly connects his name to a profession, using the standard Greek word for ‘painter’ (literally, ‘writer of life’).

The main Aramaic building inscription written on three ceiling tiles in the Synagogue is without doubt an official text, but it commemorates, besides the named dignitaries, those who ‘labored and toiled’, as well as those who contributed financially to the project.[106] The names of the principal coordinators for the works, Samuel ‘presbyter of the Jews’ and Samuel, son of Sapharas, are repeated in Greek inscriptions also on ceiling tiles framed by wreathes, where the verb ektisen (ἔκτισεν from κτίζω) meaning ‘built’ is used in both cases.[107] Two inscriptions on the Torah niche appear to name its makers, Uzzi and Joseph son of Abba. The Torah niche itself is a gesso structure flanked by faux-marble columns coloured dark green with black streaks, exactly like the pair of marbleized columns in the niche of Room 6 where Siseos’ graffito is found (Fig. 19, cp. Fig. 18).[108]

Fig. 19. Torah niche with frescoes and faux-marble columns, from building U, the synagogue at Dura Europos, Syria, ca. 340 CE, Yale Art Museum (image from Wikimedia).

Moreover, the dado above the bench surrounding the synagogue walls imitates marble panelling, like in houses at Pompei.[109] Finally, several plaster fragments found in the synagogue space also carry inscriptions, some commemorative.[110] In line with these practices of self-identification, and considering the possible pun on the name of Christ and the function of the plasterer and fresco painter as christes, it is possible to consider Siseos and Proklos, together with Mareos, Uzzi and Joseph, as identifying their contribution to the making of the monument with some of the earliest artists’ signatures. Dura’s stucco production seminally marked a tradition of making particular architectural elements in this medium,[111] together with the strength of powerful biblical iconography that exerted a key influence in the development of Byzantine art.

Conclusion: Defending Builders and the Arts

The personal affirmation of Siseos relied on a network of connections that upheld the value of his profession. Builders’ guilds had traditionally enjoyed participation in civic cultural life, with reserved seats at theatre at Termessos, in Pisidia, Asia Minor, at Miletus, and even at Athens.[112] A stone-mason or sculptor (latypos) was a member of a group, the ‘akmastai’, probably associated with athletic competitions at the gymnasion at Daldis in Lydia (3rd cent. CE).[113]

John Chrysostom considers building among the top three essential labor activities in human society, painting a picture of complementarity among the various labours, like limbs in a body.[114] I have argued that representations of labourers, builders and plasterers from Roman antiquity to the middle ages were animated by the same spirit of community and interdependence, themselves building a family of workers whose fundamental contribution to society and the arts was celebrated in appropriate ways. Blood ties were extended to include collaborators and members in the guild,[115] shaping communities that shared both common aims and common values. Among these was a principle of freedom and equality, portrayed in memorable paintings such as that of Trebius Iustus and his workshop in the Via Flaminia catacomb.

The non-elitist scope of the associations, placing worth not so much on wealth, but on the successful networks of human collaboration they sought to promote, is perhaps uppermost in the case of plasterers and stucco makers, whose work of embellishment enhanced the appearance of public meeting places, such as the Dura synagogue, but also of private homes, street shrines, doorways, passageways, and tombs of various social levels.[116] Their middle-eastern or Egyptian origin marked the flourishing of these activities within a Semitic culture, where plaster also held a hallowing function. The sixth-century Syrian John of Ephesus tells a story of a certain courtier, Theodore, who gave up his prestigious title of kastrensis in order to become an ordinary person and a labourer: he “lived many years in all religious habits, while like an ordinary man he used to work and labour with his hands at carpentering and building and carving, … and he lived an ordinary and poor life, down to extreme old age”.[117]

The combination of building and plastering with good works underpinned the flourishing of the trade association, and it is interest in this combination of skill and virtue that seems to inform the choice of examples of building and plastering episodes in saints’ lives.[118] A special case that needs more research from the point of view of this connection between the practical and the symbolic is that of the ancient monastery of Moni Latomou, “of the Stoneworker(s?)” in Thessaloniki, whose mosaics date from the end of the fifth century (it was renamed Hosios David only in 1921). The legend preserved from its foundation speaks of a strange epiphany, when the monk Senouphios, praying alone in the church during a thunderstorm, saw that “from the apse ceiling fell a covering of leather, bricks, and lime, and Christ’s face appeared”.[119] The identity of these builders may have overlapped, in Roman times, with that of men enrolled in the army, whose presence constituted the bulk of the citizens of Dura, and whose disciplined body transitioned into ecclesiastical structures including ascetic monastic communities in ways yet unexplored and poorly understood.[120] In Byzantine times, monks acted as builders or master builders, and very likely also as plasterers, painters, and stucco workers.[121] Like my grandfather, they were caught between two worlds: on the one hand, as masons, they shared the company, pay and fellowship of working-class co-workers; on the other, as skilled stucco-craftsmen (in Italian, ‘stuccatori’), they could boast a more exalted and specialized artistic ability to make architectural ornament out of gesso. It was this profession that made my grandfather essential to the finish of local churches and to the restoration of Liberty-style houses in the area.

One may even go further and suggest that the builders’ association was key to the establishment of purpose-built churches and the development of their décor. Though generally overlooked, the labour of plasterers, presupposing the work of lime-burners in the production of the materials, and in cooperation with fresco painters and mosaicists, was foundational to the identity and the development of the decorated, iconic church, as well as to the attitude of its community in respecting others’ manual labour by enjoying its results. The activity of builders was worthy of being remembered and even celebrated, as they themselves contributed in a special way to God’s praise, as Psalm LXX 95 (96), to which the two medieval miniatures with which we began were appended, aptly sings. Although ashlar masonry and faux-marbling were aniconic aspects of church decoration, the art of plastering paved the way for the making of iconic frescoes, for the painting of icons on wood, and even for plaster casting of sculptures and reliefs. This article has highlighted their critical contribution, which should now be recognized, and has hopefully contributed to paving the way for further exploration of the significant network of plasterers and stucco and fresco workers, and their pivotal function in the plastering –and the beautifying– of the world.[122]

References

| ↑1 | My thanks to the editor for organizing the September 2021 workshop where I received much precious feedback on this paper from the other contributors to this volume. I also thank the anonymous peer reviewers for many valuable comments and bibliographical references, some of which I was able to incorporate in this final version. Entry for ‘plaster’ is often omitted even where one might expect it. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It is emblematic that the ‘Bible of Plaster’ is a reprint from a nineteenth-century publication, written in antiquated language: William Miller, Plastering: Plain and Decorative (1st edn, London: B.T. Batsford, 1897; repr. London & New York: Routledge, 2015). The first chapter is a history of plaster. On Byzantine plasterers see now Flavia Vanni, Byzantine Stucco Decoration (ca. 850-1453). Cultural and Economic Implications Across the Mediterranean, 2 vols, PhD, University of Birmingham, 2020. |

| ↑3 | Benedicte Palazzo-Bertholon, ‘Confronti tecnici e decorativi sugli stucchi intorno all’VIII secolo’, in L’VIII Secolo: un secolo inquieto, Atti del Convegno internazionale di studi: Cividale del Friuli, Chiesa di Santa Maria dei Battuti, 4-7 dicembre 2008 (Udine, 2010), 285-296, at pp. 285, 288, 292. |

| ↑4 | Isabella Vaj, ‘Il Tempietto di Cividale e gli stucchi omayyadi’, in Cividale longobarda. Materiali per una rilettura archeologica, ed. by Silvia Lusuardi Siena (Milano, 2002), 175-204. |

| ↑5 | Rachel E. Danford, Manipulating Matter: Figural Stucco Sculpture in the Early Middle Ages, D.Phil. thesis, Johns Hopkins University, 2016, pp. 8 and 12, citing scholars such as Adriano Peroni, Saverio Lomartire and Martin Hoernes; Benedicte Palazzo-Bertholon, ‘Le Décor de Stuc Autour de l’an Mil: Aspects Techniques d’une Production Artistique Disparue’, Les Cahiers de Saint-Michel de Cuxa, no. XL (2009), 285–98. |

| ↑6 | This aspect deserves further study. Materials to this end have been gathered by Giulia Marsili, Archeologia del Cantiere Protobizantino. Cave, Maestranze e Committenti Attraverso i Marchi dei Marmorari (Bologna: Bononia University Press, 2019), appendix. |

| ↑7 | Ben Russell, The Economics of the Roman Stone Trade (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), 45. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199656394.001.0001 |

| ↑8 | Paula Fredriksen, Augustine and the Jews: A Christian Defense of Jews and Judaism (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2010), 22-23. |

| ↑9 | Anders Runesson and Wally V. Cirafesi, “Art and Architecture at Capernaum, Kefar ‘Othnay, and Dura-Europos,” in The Reception of Jesus in the First Three Centuries, ed. Chris Keith, Helen K. Bond, Christine Jacobi and Jens Schröter, 3 vols (London: T&T Clark, 2019-2020), 151-200, 180. For a description of the remains of a large limestone synagogue, considered to be of later manufacture, see ibid., 166-167; A. Runesson, “Architecture, Conflict, and Identity Formation: Jews and Christians in Capernaum from the First to the Sixth Century,” in Religion, Ethnicity, and Identity in Ancient Galilee, ed. J. Zangenberg, H.W. Attridge and D. B. Martin, WUNT 210 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2007), 231-257, esp. 235-239, for further debate on the dating of this building and the function of its earlier strata. |

| ↑10 | For a counter-perspective, see Glenn Peers, Animism, Materiality, and Museums. How do Byzantine Things Feel? (Leeds: Arc Humanities Press, 2020), pp. 109-112. |

| ↑11 | Danford, Manipulating Matter, p. 9. |

| ↑12 | Mauro Pesce and Adriana Destro, Dentro e Fuori le Case. Il ruolo delle donne da Gesù alle prime Chiese (Bologna: Edizioni Dehoniane, 2016), 43-50. |

| ↑13 | Danford, Manipulating Matter, pp. 12-13, discusses this thesis by Hans-Rudolf Meier, “Ton, Sten, und Stuck: Materialaspekte in der Bilderfrage des Früh- und Hochmittelalters”, Marburger Jahrbuch für Kunstwissenschaft 30 (2003), 35-52; Danford argues against the conclusion that stucco was a more appropriate Christian material because it was cheap and humble: Danford, Manipulating Matter, pp. 23-24. See also the counterargument by Beatrice Leal, “The Stuccoes of San Salvatore, Brescia, in their Mediterranean Context”, in Dalla corte regia al monastero di San Salvatore-Santa Giulia di Brescia, ed. by Gian-Pietro Brogiolo and Francesca Morandini (Mantua: Società archeologica padana, 2014), 221-246; Danford, Manipulating Matter, p. 26 and n. 68. |

| ↑14 | A discussion of this question posed as dilemma in Flavia Vanni, “Individual or collective? Stucco-workers in Middle and Late Byzantine Construction Sites,” in Dialogues between Rich and Poor: Approaches to the Poor and Societal Stratification in Byzantium, ed. A.J. Kelley and Flavia Vanni (London: Routledge, forthcoming). |

| ↑15 | As John R. Clark, Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representations and Non-elite Viewers in Italy, 100 BC-AD 315 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 97, takes the variety of scenes at Pompei. |

| ↑16 | F. D’Aiuto, “Il Vat. gr. 752: scrittura, mise en page, fattura materiale (con qualche osservazione sul Salterio Hierosol. S. Sepulcri 53),” in A Book of Psalms from Eleventh-Century Byzantium: the Complex of Texts and Images in Psalter Vat. gr. 752, ed. Barbara Crostini and Glenn Peers, Studi e Testi 504 (Vatican City: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 2016), 43-156, 146, fig. 49. |

| ↑17 | Image also available at https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.gr.752.pt.2. This miniature is not cited in the volume about this manuscript (Crostini – Peers 2016, see previous note), showing how among the two-hundred plus miniatures that it contained it has been entirely neglected. |

| ↑18 | So D’Aiuto (see n. 16). The description is plausible given the regularity of the black shape the tool is inserted into. The blackness probably gives an illusion of depth rather than shows the actual mortar (whose colour could vary from grey to pink according to the aggregate with which it was mixed). |

| ↑19 | Robert Ousterhout, Master Builders of Byzantium (Philadelphia, PA: Pennsylvania University Press, 2008), 133 at n. 29: the Kiev Psalter, 14th cent., also placed at Psalm 95 (f. 134r); the Tomic Psalter (f. 163v) and the Serbian Psalter (f. 124v). Further study of this group together would be welcome. |

| ↑20 | Ernest T. DeWald, The Illustrations in the Manuscripts of the Septuagint : III : Psalms and Odes, 2 : Vaticanus graecus 752 (Princeton/London/The Hague, 1942), 10, 13, 16, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 36, 39, 41, 47, 48. |

| ↑21 | Ousterhout, Master Builders, 55, considers Andreas Kampamares, Argiros Xiphilinos and Georgios Monomachos, three master builders named in the document dated 1421 from Iviron on Athos about the construction of a fountain in Thessaloniki, all designated oikodomoi. |

| ↑22 | Lella Cracco Ruggini, “La vita associative nelle città dell’Oriente Greco. Tradizioni locali e influenze romane,” in Assimilation et résistance à la culture gréco-romaine dans le monde ancien, Travaux du 6. Congrès d’études classiques, Madrid septembre 1974 (Madrid, 1975), 463-491; Gerhard van den Heever, “Once Again: Modelling Early Christian Social Formations and Christ-Cult Groups among Graeco-Roman Cults,” Journal of Early Christian History 10.3 (2020), 1-11; John S. Kloppenborg, Christ’s Associations: Connecting and Belonging to the Ancient City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019); see also the essays in Private Associations and Jewish Communities in the Hellenistic and Roman Cities, ed. Benedikt Eckhardt (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2019) and in Vereine, Synagogen und Gemeinden im kaiserzeitlichen Kleinasien (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2006). https://doi.org/10.1080/2222582X.2021.1950998 |

| ↑23 | Richard S. Ascough, Philip A. Harland and John S. Kloppenborg, Associations in the Greco-Roman World: A Sourcebook (Waco, TX/Berlin: Baylor UP and de Gruyter, 2012); see Harland’s online database (http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/) and the Copenhagen Inventory of Ancient Associations (https://ancientassociations.ku.dk/CAPI/) for searchable information. |

| ↑24 | http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/268-guild-of-builders/ and http://ancientassociations.ku.dk/assoc/610. |

| ↑25 | https://ancientassociations.ku.dk/CAPI/viewing.php?view=resultassoc&id=1432&hi=oikodomoi; see also CAPInv. 1458 and http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/179-oracle-from-didyma-involving-builders-at-miletos/ for a similar list of payments. |

| ↑26 | http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/court-records-concerning-a-linen-weaver-threatened-by-builders-302-309-ce/ and https://ancientassociations.ku.dk/CAPI/viewing.php?view=resultassoc&id=1934&hi=builders%20weavers. |

| ↑27 | Harland translates assistant builders. The inscription specifies that Pollion was ‘archpriest and grammateus’, 2nd cent. CE. http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/reserved-place-of-the-assistant-builders-ii-ce/. |

| ↑28 | http://www.philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/?p=24833 |

| ↑29 | W.H. Buckler, “A trade union pact of the 5th century,” in Studies presented to D.M. Robinson 2. Saint Louis (Missouri), ed. G.E. Mylonas and D. Raymond (Washington, 1953), 980-984. |

| ↑30 | CAPInv. 411, https://ancientassociations.ku.dk/CAPI/viewing.php?view=resultassoc&id=411&hi=oikodomoi: (1) the workers have to finish the work commissioned by the employer provided that this one intends to pay for it. (2) If for any personal or official reason the worker is not able to finish the work and, being “one of us” (a member of the association), presents an excuse, he will be substituted by another worker of the association. (3) If the worker that has started a work, or his substitute, does any harm to the employer, the association will compensate the employer in relation to the loan he and the worker had accorded. (4) If the employer is getting impatient because the work has been interrupted seven days, the same worker shall nevertheless continue the work. (5) If the worker gets ill, the employer shall wait up to 20 days. After that period, if the technites gets well but neglects his work, he will be substituted by another one, in the way the associations has accorded with him when he presented the excuse. (6) If the one who accepts the work presents an excuse, but one of the association’s members sees him not acting in accordance with the rules, the association will pay a fine for works in the city, and the worker himself must pay 8 gold pieces (nomismata, l. 47) and will be accused because of legal failure in accordance to the divine dispositions; and not less after having the previous fine been required. (7) The association commits itself, with its common and its private word, to pay the required fine with its present and future possessions of any kind. |

| ↑31 | http://www.philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/?p=4199 |

| ↑32 | ‘Koinon’ inscriptions (Copenhagen database): CAPInv. 1791, 1793, 1795, and esp. CAPInv. 1797 (the list headed by Rhodon, a Selgian stonemason). These monuments also displayed stone-masons’ signatures on the sarcophagi lids. |

| ↑33 | http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/donation-of-a-grave-to-a-guild-of-workers-by-metereine-i-ii-ce/ and CAPInv. 1014, https://ancientassociations.ku.dk/CAPI/viewing.php?view=resultassoc&id=1014&hi=operarii. Here see comment: ‘operarii’ is too general a designation; Edict. Dioclet. 7:1, De mercedibus operariorum, mentions 76 craftsmen beginning with ‘operario rustico’. |

| ↑34 | See http://philipharland.com/greco-roman-associations/grave-of-polychronia-with-fines-payable-to-the-marble-workers-undated/ and https://ancientassociations.ku.dk/assoc/1168. |

| ↑35 | Fabrizio Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto,” in L’orizzonte tardoantico e le nuove immagini, corpus I, ed. Maria Andaloro (Milano: Jaca Book, 2006), 259-263. |

| ↑36 | This is equivalent to the Greek maistor or protomaistor, which Ousterhout, Master Builders, 50, defines as “[t]he head of a workshop or of a guild” and translates as “master mason” or “master builder”. |

| ↑37 | Thomas F. Mathews, The Clash of Gods. A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2003, 1st edn 1993. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691246994), fig. 28; see also Uzi Leibner, Khirbet Wadi Hamam: A Roman-Period Village and Synagogue in the Lower Galilee, Qedem Reports 15 (Jerusalem: The Institute of Archaeology and the Hebrew University, 2018), Fig. 4:29, using this image to interpret a fragmentary mosaic in the synagogue, which also contains a scene of construction (see below). The crowd would be that of Samson’s men. |

| ↑38 | Mathews, Clash of Gods, 45-47. |

| ↑39 | Mathews, Clash of Gods, figs 26-27. |

| ↑40 | Fabrizio Bisconti, Mestieri nelle catacombe romane: Appunti sul declino dell’iconografia del reale nei cimiteri cristiani di Roma (Città del Vaticano: Pontificia commissione di archeologia sacra, 2000), 180-181, no. Id9.61. |

| ↑41 | See also the lost mosaic sequence from Syria showing the fraught education of the boy Kimbros, dressed in a white short tunic with black dots at the rim like the workers in the catacomb: Robin Lane Fox, Augustine: Conversions and Confessions (London: Penguin, 2015), 59, figs 5-8. The literary fortune of this animal was further explored in the long novelistic farce by Apuleius, The Golden Ass. |

| ↑42 | A construction scene, 6th cent. mosaic at Oued Rmel (Bardo Museum, Tunis), bottom row: two horses pull a cart with a column and a man on it: Aïcha Ben Abed, Tunisian Mosaics: Treasures of Roman Africa (Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, 2006), 106, fig. 5:18; Castellammare di Stabia, construction scene with oxen: Jean-Pierre Adam and Pierre Varène, “Une Peinture romaine représentant une scène de chantier,” Revue Archéologique n.s. 2 (1980), 213-238, fig. 2. |

| ↑43 | The funerary practices of ‘Christians’ and ‘Jews’ coincided to such an extent, for example in their use of commemorative gold glass, that it is best to refrain from relying on such distinctive labels as meaningful: see Eric C. Smith, Jewish Glass and Christian Stone. A Materialist Mapping of the “Parting of the Ways” (London and New York: Routledge, 2018). For an item in gold glass that displays a central figure holding a long staff (a master builder?), surrounded by different skilled workmen, Vatican Museum Inv. No. 60788, see Leibner, A Roman-Period Village and Synagogue, 151, fig. 4.9. |

| ↑44 | L. H. Petersen, “‘Arte plebea’ and Non-Elite Roman Art,” in A Companion to Roman Art, ed. B.E. Borg (Malden, MA, 2015), 214-230, 225-227, fig. 11.6. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118886205.ch11 |

| ↑45 | Petersen, “‘Arte plebea’,” 227. |

| ↑46 | On the emancipation of slaves in early Christianity, see J. Albert Harrill, The Manumission of Slaves in Early Christianity (Tübingen: Mohr & Siebeck, 1996); R. Zelnick-Abramovitz, Not Wholly Free. The Concept of Manumission and the Status of Manumitted Slaves in the Ancient Greek World (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 184-272. |

| ↑47 | For the monument, see https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-gregoriano-profano/Mausoleo-degli-Haterii.html. Jennifer Trimble, “Figure and Ornament, Death and Transformation in the Tomb of the Haterii,” in Ornament and Figure in Graeco-Roman Art: Rethinking Visual Ontologies in Classical Antiquity, ed. Nikolaus Dietrich and Michael Squire (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2018), 327-352, with earlier bibliography. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110469578-014 |

| ↑48 | Trimble, “Figure and ornament,” 338. |

| ↑49 | Adam and Varène, “Une Peinture romaine, ” fig. 18. |

| ↑50 | Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto.” |

| ↑51 | Leibner, A Roman-Period Village and Synagogue, fig. 4.15 (porter carrying a jar) and 154, fig. 4.17 (craftsmen 11-13). |

| ↑52 | Leibner, A Roman-Period Village and Synagogue, fig. 4.18, 154 and n. 58; Abed, Tunisian Mosaics, 106 fig. 5.18. |

| ↑53 | Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture, ed. Morris Hicky Morgan (Cambridge: Harvard University Press and London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1914), Book VII, ch. 2; Miller, Plastering, 3-4. |

| ↑54 | Leibner, A Roman-Period Village and Synagogue, 154, says ‘unidentified tool’ but the pointed shape looks like a trowel. |

| ↑55 | Bisconti, “Le pitture dell’ipogeo di Trebio Giusto.” |

| ↑56 | Inscription details in Bisconti, Mestieri, 161-181, with a few illustrated by drawings. |

| ↑57 | Beat Brenk, La Cappella Palatina di Palermo (Modena: Franco Panini Editore, 2010), image no. 417 (nave, South side, Middle register), Photo Atlas, vol. I, p. 343, and Testi/Schede, pp. 519-520. |

| ↑58 | Ousterhout, Master Builders, 135 and fig. 99, calls these baskets too ‘hods’, even though the shape of the modern tool with a long handle appears more suitable as a designation for the spade-like objects. |