Sarah Bromberg • University of Pittsburgh[1]

Recommended citation: Sarah Bromberg, “Gendered and Ungendered Readings of the Rothschild Canticles,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 1 (2008). https://doi.org/10.61302/PMSR4045.

The early fourteenth-century manuscript known as the Rothschild Canticles exhibits many images of the Sponsa or of monks and clerics in the presence of Christ. The following article will consider the ways in which viewers fashioned their relationship to God through these figures. In his 1990 monograph on the Rothschild Canticles, Jeffrey Hamburger provided many iconographic parallels to the manuscript’s enigmatic imagery and uncovers many sources for its varied texts. Madeline Caviness’s semantic triangle provides a conceptual framework for my analysis which seeks to expand upon the method employed by Hamburger, which limits itself to historical explanations. I will therefore add the “critical theories” side of the triangle by invoking contemporary gender, film and queer theory. Further, I want to rebuild Hamburger’s historical side of the triangle by utilizing other medieval histories of gender and sexuality. Two separate triangulation processes will reveal the multivalent attitudes towards gender expressed in the Rothschild Canticles’ illuminations. First I shall consider a male reader’s process of identifying with the Sponsa. Second I shall reconsider the binary system of gender upon which my initial analysis of readership and imagery depends. In some cases, my different readings will contradict each other, but my intention is not to invalidate one reading with another, nor to privilege one interpretation over another. Rather, I wish to demonstrate that multiple possibilities of understanding coexist.[2]

Triangulation #1: Investigating Male Identification with the Sponsa

Hamburger comprehensively contextualized the Rothschild Canticles in the medieval traditions of bridal mysticism and female spirituality by comparing it with other texts and images used by women. By highlighting female mysticism and spirituality, Hamburger made a significant contribution toward considering gendered aspects of religious devotion in this manuscript. Hamburger assumed that the imagery and text in the manuscript were directed almost exclusively toward a female reader.[3] Recently, Pamela Sheingorn and Flora Lewis have clarified that a male viewer or reader of the Rothschild Canticles would also have been able to see his spiritual quest for divine union embodied in a female figure.[4] Corine Schleif has suggested that an investigation of male readership would be a useful endeavor.[5] The possibility of a male audience invites further investigation. This article will begin with an exploration of the process by which a male reader could perceive of himself as the bride of Christ by looking at a female representation of the soul. Although the Sponsa is depicted many times in the Rothschild Canticles, I will focus on the opening of fols. 72v – 73r (Figures 1 and 2). Although I believe a female reader may have also used the manuscript, I will restrict my discussion to a male reader’s perspective.[6]

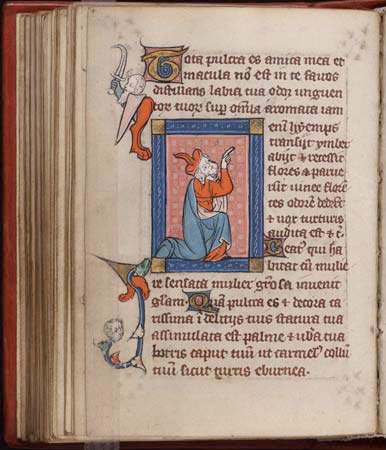

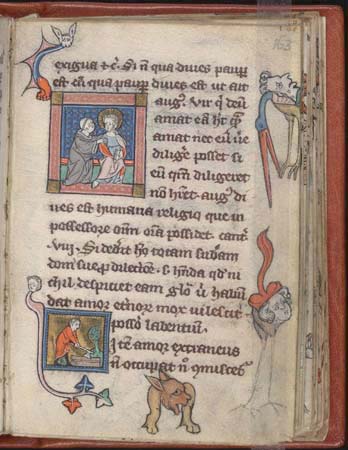

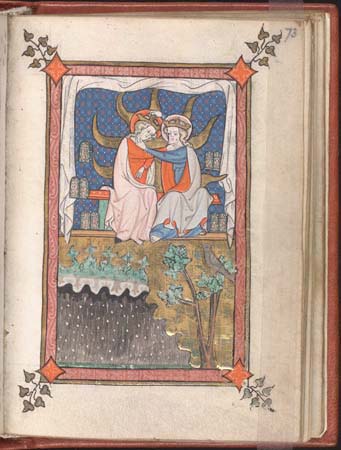

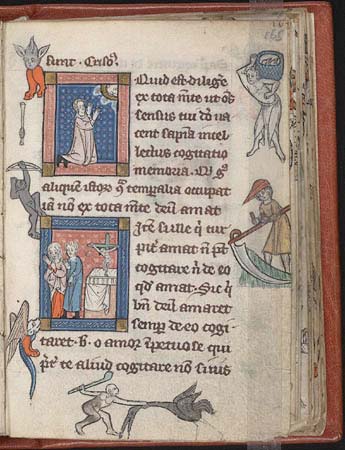

Fig. 1. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 72v.

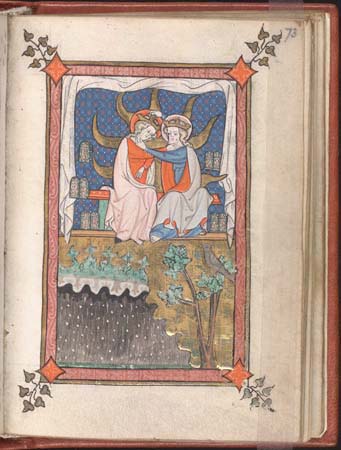

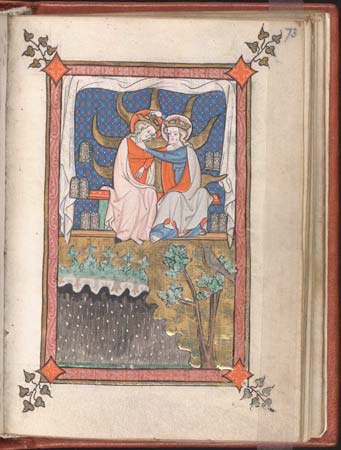

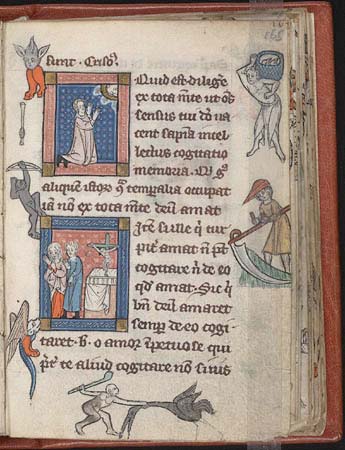

Fig. 2. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 73r.

The identity of the patron of this manuscript is unknown. Hamburger has posited that a highly educated female monastic patron was guided by a Dominican male advisor, who may have also compiled the text.[7] On fol. 73r, Christ as the heavenly bridegroom crowns the Sponsa. Both figures are encompassed by the rays of the sun and surrounded by containers of aromatic spices, a reference to the Song of Songs 4:10, which appears on the facing verso. Below, winter is depicted abstractly with white flakes against a black background, and spring as green plants, trees and a bird. These natural forms refer to the change of seasons described in Song of Songs 2:11-12. Fragments of these verses are also found on the verso.[8] In this enticing heavenly representation of divine union, the Sponsa is depicted in a submissive manner in relation to Christ. She looks downward, tilts her head and defers to Christ to be crowned. In this observation, I am inspired by Madeline Caviness’s description of a similar image, the Coronation of the Virgin Mary on the central north portal at Chartres (Figure 3):

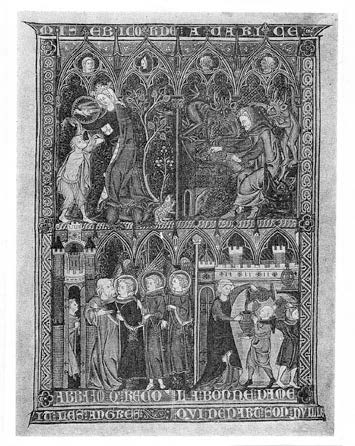

Fig. 3. Coronation of the Virgin, Central Portal, North Porch, Cathedral of Notre- Dame of Chartres, c. 1205 – 1215, Photo: c. Jane Vadnal.

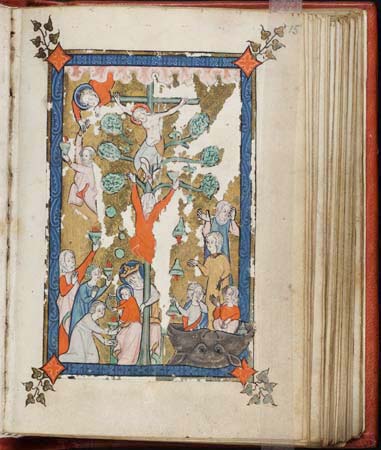

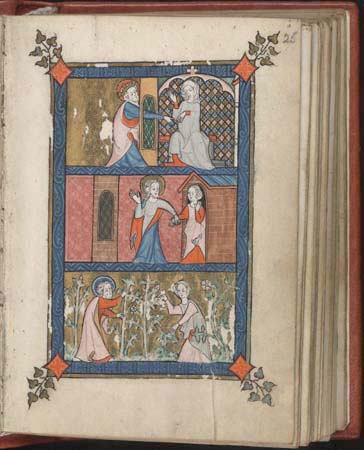

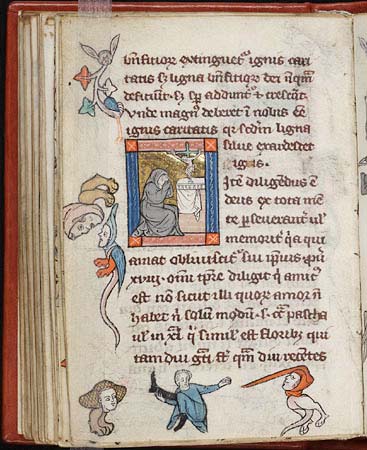

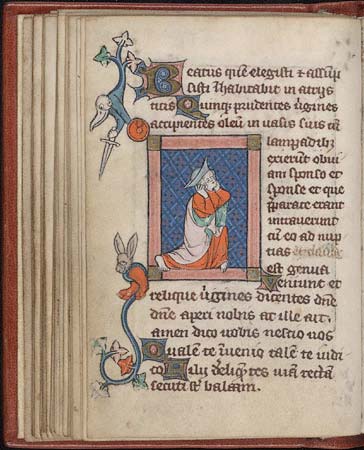

“[Mary] has been represented as the bride of Christ and the Queen of Heaven, an unequal consort whose body language is subservient as she turns toward her son with bowed head.”[9] Although I will focus on the implications of the inferiority expressed by the representation of the female figure of the Sponsa in fol. 73r, the Rothschild Canticles manifests several other instances in which the gestures, positions, and actions of the Sponsa express a similar degree of subservience. For example, on fol. 15r a figure who represents both a Wise Virgin and a Sponsa kneels below the Christ child, who is about to crown her with a green wreath (Figure 4).[10] A second Wise Virgin/Sponsa relies on Christ’s strength to be pulled toward the Heavenly realm from which he descends; she ascends not through her own agency, but through Christ’s power. On fol. 25r, the top register includes a Sponsa demurely looking downward while meekly offering her hand to the crowned Christ, who aggressively reaches through a window to grasp her hand; in the middle register, Christ leads the Sponsa out of a small building, grasping her by the hand, thus reinforcing her submission (Figure 5).[11]

Fig. 4. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 15r.

Fig. 5. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 25r.

It is no accident that both of these images of women—the Virgin Mary and the Sponsa—exhibit such passivity. Drawing upon Carol Clover’s modern film theory and Caroline Walker Bynum’s historical studies, I will demonstrate that the soul has been gendered female in the Rothschild Canticles in order to indicate supplication and dependence; thus I will build both the theoretical and historical sides of the Caviness triangle. Examining what is signified by a female figure allows me to consider how a male viewer would identify with the Sponsa. Clover has written that the sex of a character in the slasher genre of horror films is not just determined by biology, but by gender. She explained why victims of attack are often women: “A figure does not cry and cower because she is a woman; she is a woman because she cries and cowers.”[12] While I am currently less interested in incorporating Clover’s interpretation of violence into my discussion of the Sponsa, I am intrigued by her understanding of gender. If we apply Clover’s insightful remark to the representation of the Sponsa on fol. 73r, we can determine why she is depicted as a female. First, in order for the visual metaphor of a divine marriage to obtain, the spiritual lover of Christ must be represented as female since Christ is represented as a male. This keeps the heterosexual norm intact. Second, the Sponsa is depicted as a female because of her dependent and supplicant position. Separating gender from biology, in this instance, enables us to begin to understand how a male viewer would conceive of his union with Christ while looking at this image of the Sponsa. A male reader and viewer would not be identifying with a representation of a woman, but with a desire for Christ which has been gendered female. Clover and Bynum’s investigations reveal parallel notions of the ways in which gender is constructed. Bynum has observed that late medieval monastic and mystic male writers use women as symbols to describe inferiority in relationships to God. Bynum pointed to an example of extreme deference before God in the writings of John Tauler: “When Tauler sought a symbol of the soul’s utter self-abasement before God, its utter denuding and emptying, he…chose the poor Canaanite woman of Matthew 15:21-28, who referred to herself as lower than a dog.”[13] A male viewer of the Rothschild Canticles might be similarly accustomed to using the visually feminized symbol of the Sponsa in order to act out his own supplication in seeking divine union.

Medieval scientific and medical writings shed additional light on why a male reader of the Rothschild Canticles could see his experiences reflected in the image of a soul as a female. Several scholars have examined the ways that medical and scientific concepts interacted with and influenced religious discourse. Vern Bullough demonstrated that misogyny pervaded medieval scientific attitudes.[14] Joan Cadden found a complex relationship between medieval scientific and medical conceptions of sex difference and religious and secular understandings of gender difference.[15] In particular, Madeline Caviness has noted that: “Galen’s view that biological sexual difference is not simply binary prevailed in the medieval discourse of sexuality.”[16] Galen wrote that the male and female genital organs were analogous to each other in structure. He describes the female genitalia as inverted male genitalia:

Think first, please, of the man’s [sexual organs] turned in and extending inward between the rectum and the bladder. If this should happen, the scrotum would necessarily take the place of the uteri [sic], with the testes lying outside, next to it on either side; the penis of the male would become the neck of the cavity that had been formed; and the skin at the end of the penis, now called the prepuce, would become the female pudendum itself…In fact you could not find a single male part left over that had not simply changed its position; for the parts that are inside in woman are outside in man.[17]

Galen also emphasized that the female organs were inferior to the male organs: “the woman is less perfect than the man in respect to the generative parts.”[18] Bullough contended that this understanding of male and female reproductive systems pervaded medieval thought. This understanding of the relationship between the two sexes’ biological makeup likely affected the reader’s awareness of the relationship between the two genders. When a medieval male viewer looked at the Sponsa, he did not perceive a body that was in complete opposition and equal to his gender. Instead, he saw a lesser, flawed version of his own body.

For a male viewer, associating his soul with inferior feminine qualities was an essential ingredient in his spiritual quest. Bynum’s explanation for why men identified with females as symbols can help to explain why a male reader and viewer would want to identify with an image of a female Sponsa: “Man became woman metaphorically or symbolically to express his renunciation or loss of ‘male’ power, authority and status.”[19] Bynum posited that positions of power placed so much pressure on men that they desired a release from the responsibility of their status. Thus, it is possible that a male reader and viewer of the Rothschild Canticles identified with the female figures in order briefly to escape the duties of his privileged social and ecclesiastical position.

However, identifying with characteristics that are gendered female might be troubling to a male reader and viewer due to his conception of female inferiority. Thus, he might eventually want to deny this sort of identification. Carol Clover has demonstrated that the modern slasher film provides a psychological apparatus in its narrative to allow the male viewer to cease identifying with characteristics that are gendered female. A common pattern emerges in which a woman is gruesomely beaten, survives the attack, and later kills her attacker.[20] In brandishing a weapon, thrusting it upon her victim and assuming an aggressive male gaze she becomes phallacized.[21] This narrative device regenders this victim-turned-hero as male. In a parallel way, the Rothschild Canticles imagery suggests that affection for Christ can also be gendered male. When looking at a subsequent image, on fol. 163r, the male reader and viewer can resist the act of feminizing his religious devotions by identifying with the monk who replaces the Sponsa’s physical and spiritual position (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 163r.

The meaning attached to divine union becomes even more complicated when fol. 73r is compared to fol. 163r.[22] This illumination changes the way a male viewer relates to an image of a figure reaching for and adoring Christ because that figure is now male. Several visual similarities between these two images suggest that the male figure was conceived as a replacement for the female Sponsa. In both images, Christ sits on a bench in the same position: one foot extends toward the Sponsa or the monk and the other foot points to the left. Both the Sponsa and the monk sit on Christ’s dexter. The Sponsa and Christ look at each other. Similarly, the monk and Christ exchange glances. Further, like the Sponsa, the monk reaches out and touches Christ. The replacement of the Sponsa with the monk allows the male reader to reject the sense of inferiority gained through identification with the female gender and identifying with the greater status monks had.

The differences between the Sponsa and the monk’s physical interaction with Christ are also instructive. Unlike the Sponsa, who gently holds Christ’s chin with one hand, the monk aggressively extends his arms to embrace Christ with both hands.[23] In addition, the monk’s gaze is more forceful than the Sponsa’s. While the Sponsa partially directs her gaze downward as she looks at Christ, the monk looks directly at Christ without any indication of deference. Christ responds differently to the monk than he does to the Sponsa. Christ does not embrace the monk as he does the Sponsa; in fact, his entire body, except for his head, is turned away from the monk. For a male reader and viewer, this image provides an alternative to the erotic supplicant nature of bridal mysticism.

This image of a monk and Christ was an intentional “correction” to the image of the coronation of the Sponsa. This visual shift expresses a historical transition.[24] As Pamela Sheingorn has noted, men could have resisted identifying with female figures that represented their souls: “There may have been increasing reluctance on the part of many medieval male religious to identify with the female soul of bride mysticism as that soul’s relationship with Christ was realized in more concrete imagery.”[25] Although Sheingorn wrote that such reluctance has not been documented by scholars, the Rothschild Canticles seems to document visually this rejection of female imagery to represent a soul loving God.

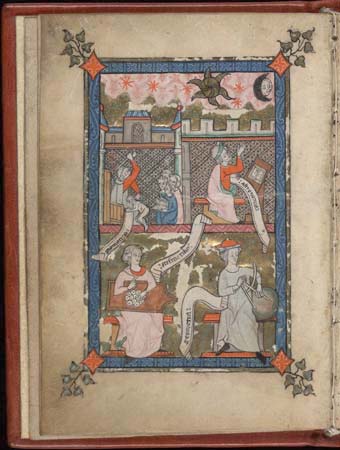

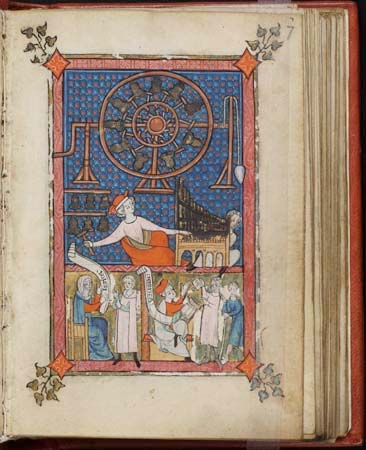

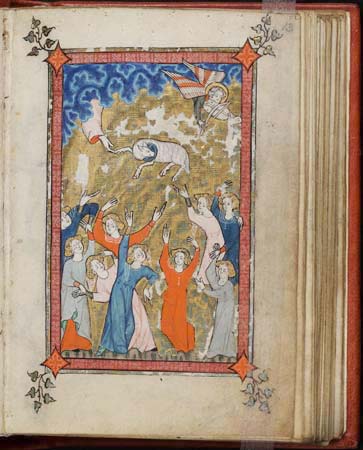

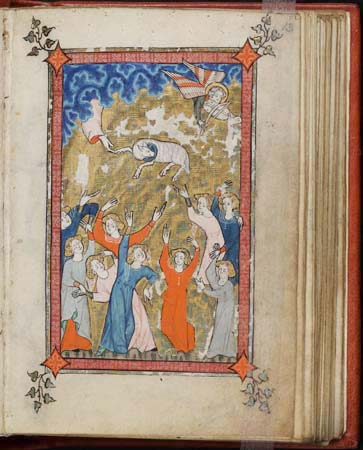

My discussion of a male reader and viewer’s intervisual connection between these two images exposes two aspects of a complicated viewing process encouraged by the structure and appearance of the entire manuscript. First, in assuming a viewer would conceptually link two illuminations that are separated by many folios, I am indebted to Michael Camille’s statement that the owner of this manuscript likely read and viewed the text and images in a nonlinear manner.[26] Second, while I have pointed out but one instance in which figures of different genders perform analogous activities, there are many more examples. Illuminations on fol. 6v (Figure 7) and fol. 7r (Figure 8) depict the Seven Liberal Arts. Logic is personified as a woman in the bottom left corner of fol. 7r, but the other six liberal arts are personified as men. Many women dance below an image of the lamb on fol. 13r (Figure 9). On fol. 165v, a man’s upraised arms and slightly swaying body echo the women’s dancing movements (Figure 10). Pamela Sheingorn has observed that “the user of the manuscript is expected to be able to shift gender identification even when the iconography is the same.”[27]

Fig. 7. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 6v.

Fig. 8. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 7r.

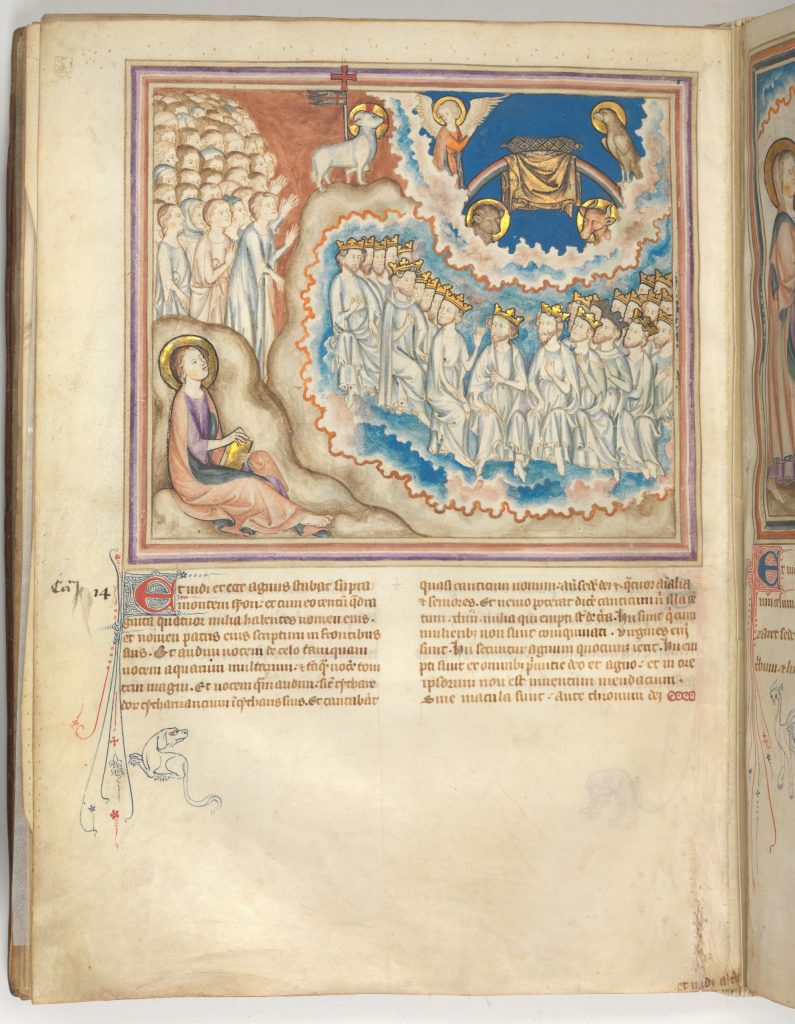

Fig. 9. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 13r.

Fig. 10. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 165v.

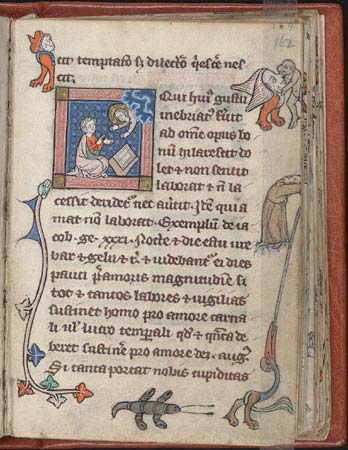

The image of the monk reaching for Christ in a gesture of devotion and admiration on fol. 163r is one of many incidents of a male figure adoring Christ. This illumination appears in a gathering consisting of fols. 161r – 166v and containing a compilation of texts from an unidentified florilegium or glossed Bible. As Hamburger has noted, this gathering includes many exegetical comments on Biblical passages regarding the proper and improper ways to love God, a theme which is developed throughout much of the Rothschild Canticles.[28] Although Hamburger briefly but perceptively contextualized this collection of textual excerpts within the broader themes of this manuscript, he did not explore their accompanying illuminations and the differences between these texts on love and other texts in the Rothschild Canticles, which reveal that there are other models of devotion accessible to a man besides those involving imagining himself in a position of feminized submission. Many of these figures sit or kneel while reading or praying in the presence of a divine face, hand, or body that emanates from the clouds; others kneel before an altar which often displays a crucifix. These illuminations accompany a text that conceptualizes love for God without the eroticized language from the Song of Songs found in earlier parts of the Rothschild Canticles.

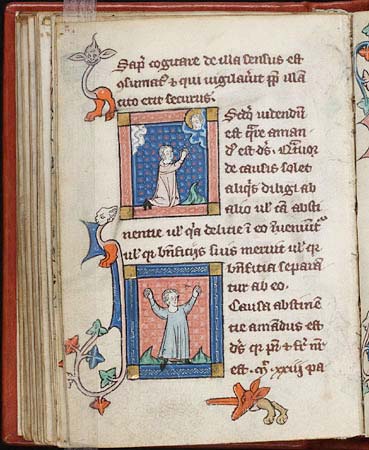

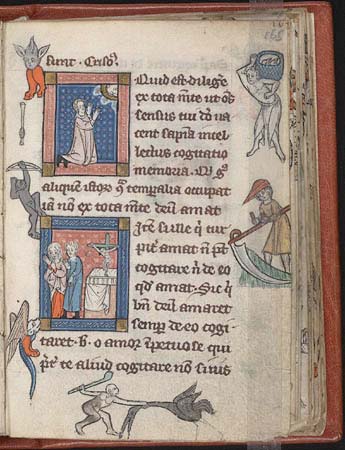

Fig. 11. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 161r.

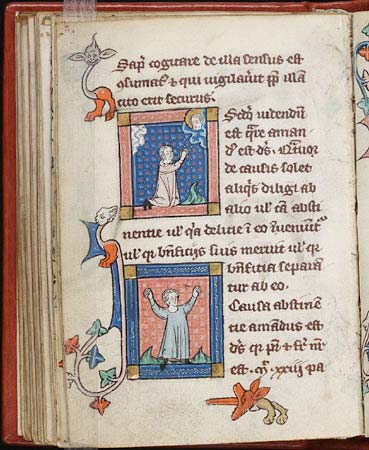

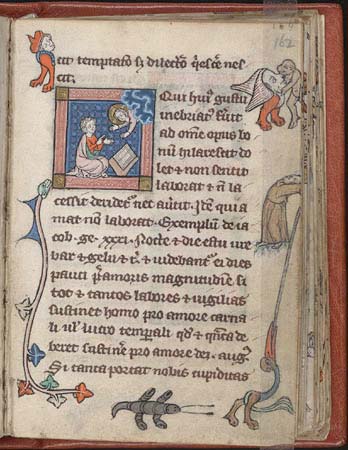

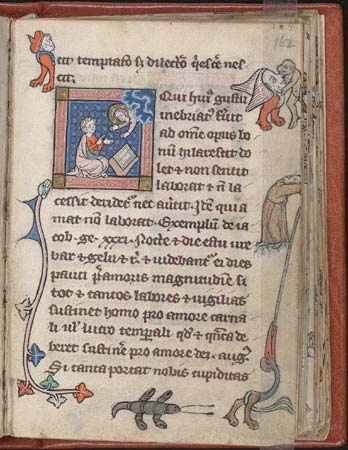

Fig. 12. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 162r.

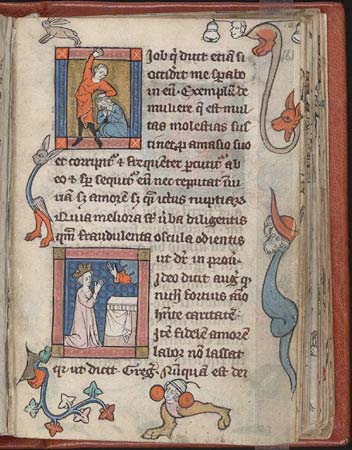

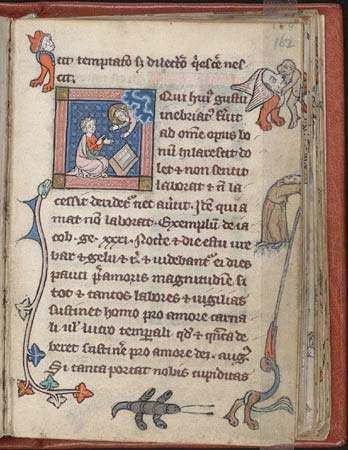

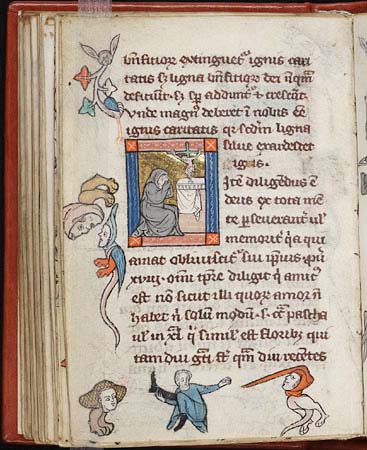

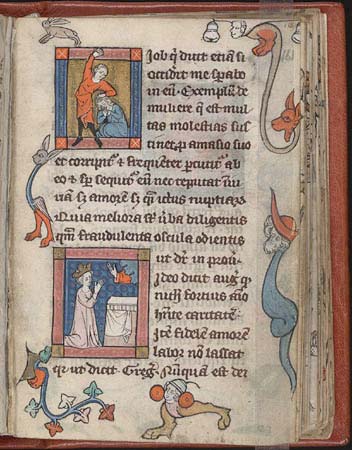

On the lower illumination of fol. 161r, a young, crowned boy kneels before an altar and prays while looking in the direction of Christ’s hand extending from behind a blue cloud-like formation in a gesture of blessing (Figure 11). This small illumination is accompanied by excerpts from a text by Augustine that celebrates loving God with one’s mind and a passage by Gregory regarding labor that is motivated by loving God.[29] On fol. 162r, a young boy kneels in front of a book while pointing toward an equally youthful Christ, whose arms and head extend from a cloud-like formation (Figure 12). The two face each other, Christ’s hands extending toward the youth. This interaction between a boy and Christ illustrates a lengthy passage that explains that the labor of loving God does not involve the pain, suffering, and exhaustion normally associated with the labor of acquiring carnal love and earthly wealth.[30] On fol. 164v, a monk kneels before a crucifix (Figure 13), a counter-example to the man and woman who turn away from a crucifix in order to pursue lustful activity on the facing verso, fol. 165r (Figure 14).[31] On fol. 165r, another male youth, kneeling and wearing a pink hooded robe gestures towards a cross-nimbed face surrounded by a cloud. The miniature illustrates a passage attributed to John Chrysostom that defines what it means to love God with one’s whole heart.[32] On fol. 165v, another young boy in a pink hooded robe kneels while looking at the bearded face of God hovering within a blue cloud-like formation; the lower image on this folio shows a male figure raising his arms and gently swaying his hips to illustrate the importance of loving God the Father more than one’s own earthly father (Figure 15).[33] This gathering ends with another kneeling hooded male figure in front of a crucifix that accompanies a passage discussing the delight and sweetness of loving God.[34]

Fig. 13. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 164v.

Fig. 14. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 165r.

Fig. 15. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 165v.

Although the focus of this article is not an in-depth analysis of the textual passages, I have discussed these excerpts in order to demonstrate that the language does not depend on the gendered description of love between God and a soul from the Song of Songs. In contrast, many of the excerpts on fol. 72r from the Song of Songs praise the head, neck, lips, and breasts of the Sponsa. Moreover, images of male figures whose gestures and actions reveal admiration for Christ frequently appear throughout the entire manuscript, beyond the gathering of fols. 161r – 166v. Pamela Sheingorn has also noticed the prevalence of male figures in the Rothschild Canticles and, most importantly, has observed that these hermits, monks, and seers appear more often than the female representation of the soul.[35]

Triangulation #2: Escaping Gender Binaries

The second section of this article will demonstrate that the Rothschild Canticles visualizes an ever greater shift away from and beyond the gendering of spiritual desire. The devotees on fols. 161r – 166v, which have initially been categorized as male youths, on reconsideration, have many androgynous facial and bodily features. Androgyny, in this case, denotes a lack of gendered qualities rather than a combination of male and female characteristics. Hamburger noted one instance in which a kneeling figure on the lower illumination of fol. 14v cannot conclusively be classified as male. However, he did not seem to notice that ambiguously male figures, such as the above-mentioned devotees, appear throughout the Rothschild Canticles.[36]

The worshippers of Christ on folios 161r, 162r, 165r, 165v, and 166r can be reevaluated in terms of their ungendered appearance. Initially, I classified these figures as male because they did not seem female. Since they did not have the hairnets found on the female souls of fol. 13r (Figure 16), or the long hair as found on the Sponsa on fol. 73r (Figure 17), or a veil as found on the lustful woman of fol. 165r (Figure 18), I assumed these figures could not be female and then must be male. However, these devotees are not definitively represented as male: they are beardless, and their loose, flowing robes conceal their anatomy. Although beardlessness indicates youth, it simultaneously signifies androgyny by portraying prepubescent sexuality, a time before secondary sexual characteristics such as beards are developed. In observing their lack of a fully developed male sexuality, I recognize the necessity of conceiving of these figures as genderless. If sex, at its most basic level of definition, refers to the biological structure of a person, and gender to a cultural construction, then I must refer to these figures in terms of gender, or in this case, a lack thereof. As part of an image that was likely fashioned by the combined efforts of the illuminator, manuscript designer, theological advisor/compiler and the patron, these androgynous figures are a cultural production.

Fig. 16. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 13r.

Fig. 17. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 73r.

Fig. 18. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 165r.

The manuscript invites a reading that relies more on an analysis of these figures’ gender than their sex. A major component of the Rothschild Canticles’ visual language is the devotional activity of these figures, which prescribes the actions of the reader/viewer. Rather than communicate that a lack of physical sexual characteristics is necessary for devout pursuits, these images suggest to the reader/viewer that in order to participate in these forms of worship, one must imitate, but not become, an asexual being. I shall initially contextualize these ungendered beings with several medieval visual and textual representations of asexuality in order to ultimately construct a parallel between the ungendered life of the reader and the ungendered appearance of these figures.

The facial features of these ambiguously gendered beings are identical to those of the angels that frequently appear in the Rothschild Canticles. Both the angels and these youths have round, beardless faces and short, curly hair. A comparison between the angel on fol.13r and the devotee on fol. 162r (Figure 19) confirms the similarity. Angels are also found on folios 44r, 77r, 81r, 90r, 94r, 182r, and 185v. Angels, in medieval theology, were traditionally understood as sexless. Debra Higgs-Strickland has noted that medieval representations of angels emphasized their asexuality: “By deliberate contrast, in order to convey their celestial and asexual natures, artists rendered angels with androgynous and sylphlike rather than anatomically specific bodies, without attributes suggestive of earthly physicality.”[37] Since angels appear throughout the Rothschild Canticles, the viewer would have had many opportunities to note that these youths were as androgynous as the angels.

Fig. 19. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 162r.

These figures of an indeterminate gender in Rothschild Canticles resemble angels in two French manuscripts produced at the same time as the Rothschild Canticles, around 1300. The Ruskin Hours exhibits an Annunciation scene within a historiated initial (Figure 20) in which the angel has the same short curly hair, beardless face and draping garments as many of the figures without a clear gender in the Rothschild Canticles. An illumination from La Somme le Roi, written by the Dominican Père Laurent for Philip III of France (c. 1279), also includes the three angels that visit Abraham to announce that Sarah will bear a child (Figure 21). These angelic figures manifest the same androgynous characteristics, round beardless faces and loosely draped clothing as the figures in the Rothschild Canticles.

Fig. 20. Initial D: The Annunciation; Initial D: A Young Man Praying to Christ in the Clouds, The Ruskin Hours, beginning of the fourteenth century, 26.4 x 18.3 cm., The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, 83.ML.99.37v.

Fig. 21. La Somme le Roi, ca. 1279, The British Library, Add 28162, fol. 9v. © The British Library, London,. All Rights Reserved.

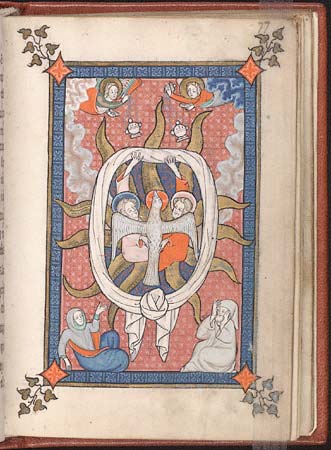

Utilizing insights from queer theory we can observe that the androgynous figures complicate the representation of the highly gendered and heterosexualized Sponsa- Sponsus relationship. Karma Lochrie has defined a goal of this methodology: “[Queering] risks the anachronism of speaking of sexuality in the first place to unsettle the heterosexual paradigms of scholarship.”[38] Lochrie intentionally queered the previous scholarly focus on heterosexual mystical sex between the bride and bridegroom found in Song of Songs commentaries by examining women’s use of eroticized language and imagery to describe and visualize devotion to a feminized Christ.[39] In the Rothschild Canticles, another type of alternative to the heterosexual model of bridal mysticism is present in that devotees, while supplicant, do not display overt male or female characteristics, as they wear loose clothing and have round, youthful, beardless faces. Moreover, on folio 162r (Figure 22), Christ is not depicted as the highly masculine spiritual lover as on fol. 73r. Christ no longer displays his power by crowning a Sponsa and is depicted with the same beardless, youthful, round face as both his devotee and the angelic figures throughout the manuscript.[40] Without clearly gendered figures, representing exclusively heterosexualized spiritual desire becomes impossible.

Fig. 22. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 162r.

While Lochrie’s approach provides the impetus to explore this additional mode of devotion in the Rothschild Canticles, historical and art historical context can also be invoked to explain the meaning and function of the ungendered figures. The genderless appearance of these figures could connote the ideal genderless state of monks, especially that of our male reader, who would have likely been a Dominican advisor. John Bugge has surveyed beliefs, purported by early Christian fathers and Gnostics, that monastics should imitate the ideal sexless state of humanity before the Fall that would again be achieved in the Millennium. Bugge pointed to Saint Ambrose’s commentary on the vita angelica in which the church father asserts that monastic virgins embody the angelic status of human nature that was lost in Paradise.[41] Further, the expectation of post-apocalyptic asexuality for those who avoid marriage (i.e., monks) derives from the following passage found in Luke: “The children of this world marry and are given in marriage. But those who shall be accounted worthy of that world and of the resurrection from the dead, neither marry nor take wives. For neither shall they be able to die any more, for they are equal to the angels, and are Sons of God, being sons of the resurrection.” (Luke 20:34-36)[42]

By sustaining virginity, monks gave up gender identity. As both St. Ambrose and the author of the Gospel of Luke equated virgins with angels and angelic qualities, it is significant that the androgynous devotees in the Rothschild Canticles are depicted to have the same physical characteristics as angels in the manuscript. Thus, these androgynous figures could express the sexless angelic state of virginity.

Virginity was visually expressed through genderless figures elsewhere in late medieval art. For example, in the Cloisters Apocalypse, the 144,000 virgins, who stand to the left of the lamb, are shown as androgynous figures, as is St. John himself (Figure 23). Like the figures in the Rothschild Canticles that do not seem clearly male or female, these figures have youthful, round faces and delicate, soft facial features. The male figures are differentiated from the androgynous ones, a distinction also found in the Rothschild Canticles. In this image from the Cloisters Apocalypse, many of the virgins do not have beards, while the kings do have beards. The angel, the symbol of Matthew, is portrayed with a young beardless face, delicate eyes and mouth.

Fig. 23. Cloisters Apocalypse, 1320, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, 1968 (68.174), fol. 25v. Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Heterosexist elements still persist in my reading of the Rothschild Canticles, and, following the example of Karma Lochrie’s rejection of heteronormativity, I intend to reconsider them. Imposing a binary classification of homosexuality and heterosexuality upon the Middle Ages inaccurately positions heterosexuality as a norm against which the abnormal concept of homosexuality is measured. Lochrie asserts that these norms themselves are the invention of nineteenth-century statisticians.[43] Lochrie’s argument that the Middle Ages predates a time when heterosexuality was considered normal allows us to refrain from positioning the Sponsa-Sponsus imagery as the standard, most important aspect of devotion expressed in the Rothschild Canticles from which other types of represented devotion deviate. Since the representations of the devotees and Christ defy gender classification, it is not possible to posit a homoerotic relationship between the figures; my intention is not to literally follow Lochrie’s process of challenging heteronormativity. When I posited that the male reader could escape the process of imagining his soul as feminine while looking at fol. 73r, a large illumination with richly painted details, by transferring his identification process to the image of the monk on fol. 163r, a much smaller illumination, I still positioned the image of the Sponsa’s Coronation, and the larger context of bridal mysticism as something prevalent and powerful enough to generate an adverse reaction on the part of the male reader. In creating an opposition between a heterosexualized desire for God as visualized through the Sponsa’s behavior on fol. 73r and a homosocial relationship to Christ as embodied by the monk’s actions on fol. 163r, I created a binary opposition between the meanings attributed to the monk and the Sponsa. I assumed that representing a monk signified certain masculine qualities, such as power and aggressive behavior, that were opposite to the feminine qualities of submission and dependence. Yet, as I will soon demonstrate, a monk cannot always be associated with masculine qualities. In his lack of complete masculinity, the gender of the monk is not fully opposite to the gender of the Sponsa. The signification of a male figure (the monk of fol. 163r) does not need to be set in opposition to that of a female figure (the Sponsa), as medieval monks’ and priests’ lives were not defined by medieval constructs of masculinity. Robert Swanson has argued that the dictates of the Gregorian Reform prevented the medieval male religious from participating in activities that would have defined him as masculine.[44] Drawing upon Swanson’s scholarship, I suggest the monk of fol. 163r need not signify masculinity.

With the Gregorian Reform of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, greater numbers of monks attained the status of priests than before, and chastity was enforced on this newly developing clergy. The requirement of clerical celibacy further removed men from the masculine duties of family life, which can be categorized as impregnating women, protecting children, and providing for one’s family.[45] To name the gender of the clergy for the period between the eleventh and early sixteenth centuries, Swanson has proposed the term “emasculinity” to account for a person sexed male but unable to perform masculine activities.[46] The clergy’s status of emasculinity was doubly reinforced: in contrast to the dictate of clerical celibacy, secular men were praised for marrying and producing children in thirteenth-century sermons.[47] The monk who reaches after Christ in the Rothschild Canticles connotes this emasculinity. The “male” reader, likely a monk, may also be categorized as emasculine because a religious imperative would have prevented him from engaging in heterosexual family and social behaviors. Moreover, the androgynous figures’ physical appearance also visualize a state of emasculinity; as noted before, they are not female, and with their short hair it may be tempting to categorize them as male, but without beards, and with their graceful facial features, they are not quite virile adults.

Fig. 24. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 73r.

Fig. 25. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 161r.

Fig. 26. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 162r.

Fig. 27. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 164v.

Fig. 28. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 165r.

Fig. 29. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 29v.

Exposing androgyny may appear to risk a reversal of the scholarship that has so necessarily inserted an awareness of gender into the study of medieval art and history over the past few decades. Yet the Rothschild Canticles does not privilege ungendered over gendered models of devotion or vice versa. The presentation and structure of the manuscript’s illuminations do not allow either conception of spirituality to displace or dominate the other. The Sponsa-Sponsus imagery is emphasized through a series of full-page illuminations such as fol. 73r (Figure 24), replete with extensive amounts of gold leaf and costly pigments. An equally powerful visual phenomenon, the androgynous figures, appear not just on folios 161r-166v (Figures 25-28), but from the beginning to the end of the Rothschild Canticles. These figures guide and imitate the viewer’s looking process. Many, such as that on fol. 29v (Figure 29), appear in texts opposite full-page illuminations. Others can be found hovering in celestial space below Christ, e.g. on fol. 38r (Figure 30).

Fig. 30. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 38r.

Several of the illuminations visualizing Trinitarian themes also display personages of an indeterminate gender. One example is the seated admirer who gesticulates toward the Trinitarian form on fol. 77r (Figure 31). All have similar facial features and garments that resist definition by gender. The Rothschild Canticles includes a wide variety of illuminations that reinforce and evade a binary gender system. In addition to triangulating between history and theory, perhaps it is necessary to triangulate between gendered and ungendered readings/viewings to comprehend the complexity of this manuscript.

Fig. 31. Rothschild Canticles, ca. 1300, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, MS 404, fol. 77r.

Sarah Bromberg is a Ph.D. candidate in Art History at the University of Pittsburgh. Bromberg focuses on images associated with visionary, devotional and exegetical forms of biblical commentary that are found in manuscripts used for ritual practices, private prayer and intellectual study. Methodologies and broader issues of interest are: gender theory, reception history, artistic commerce and patronage. Her undergraduate thesis and several ensuing conference papers analyzed Hildegard von Bingen’s *Scivias* illuminations. At Tufts University, under the direction of Madeline Caviness, she wrote her Master’s thesis on the *Rothschild Canticles*. Currently, for the dissertation, Bromberg is examining illuminations found in fifteenth-century recensions of Nicholas of Lyra’s *Postilla litteralis super totam bibliam*

References

| ↑1 | This paper is a revision of part of my Master’s thesis, “Problematizing Gendered Readings of the Rothschild Canticles,” (Tufts University, 1999) written under the direction of Madeline Caviness. I would like to thank Madeline Caviness and my current advisor, M. Alison Stones, for guiding me on the revision process. I wish to extend my gratitude to Corine Schleif for providing a very careful reading along with suggestions of precise phraseology and to the anonymous readers for contributing invaluable comments that enabled me to refine my arguments. I am also grateful to Peter Reid and D. Mark Possanza for generously transcribing and translating the passages of the Rothschild Canticles provided in the notes below. The responsibility for any remaining errors rests with me. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The marginalia present an additional powerful counterpart to the framed images; however, the meaning attached to their presence is not within the scope of this article. |

| ↑3 | Occasionally and only briefly does Hamburger allow for the possibility of a male reader and viewer. In discussing the text on fol. 65v, Hamburger wrote: “The Rothschild Canticles places the words of Song of Songs 1.6 in the mouth of the reader, thereby identifying him (or her) with the Sponsa.” See Jeffrey Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles: Art and Mysticism in Flanders and the Rhineland circa 1300 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 106. Later, Hamburger indirectly implied that imagery based on bridal mysticism could be directed to male readers: “Bridal mysticism is hardly the only current in female spirituality, and its conventions were not restricted to texts written for women. The use of feminine—as opposed to female—imagery need not imply a female audience…” See Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 157. Moreover, Hamburger noted that the textual evidence does not guarantee a female reader: “Philological criteria suggest, without proving conclusively, that the Rothschild Canticles was addressed to a woman.” See Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 155. |

| ↑4 | Pamela Sheingorn wrote that it is possible: “to understand bride mysticism as a specific set of social practices in which the role of the soul, a female identity, could nonetheless be assumed by either males or females.” See Pamela Sheingorn, Review of The Rothschild Canticles by Jeffrey Hamburger. Art Bulletin 74 (December 1992): 680. Flora Lewis wrote: “Men could use the theme of the female soul, the anima, to explore the metaphor of sexual union with a male God.” See Flora Lewis, “The Wounds in Christ’s Side and the Instruments of the Passion: Gendered Experience and Response,” in Women and the Book: Assessing the Visual Evidence, ed., Lesley Smith and Jane H.M. Taylor (London: The British Library/Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1997), 214. Hamburger has since refuted Lewis’ argument, claiming that thirteenth- and fourteenth-century visual picture cycles that literally represent the Song of Songs are only found within women’s monastic environments. See Jeffrey Hamburger, “The Visual and the Visionary: The Image in Late Medieval Monastic Devotions,” in The Visual and the Visionary: Art and Female Spirituality in Late Medieval Germany (New York: Zone Books, 1998), 507 n. 58. |

| ↑5 | Corine Schleif, citing her agreement with Sheingorn’s proposition of potential male readership, wrote: “If then the book did not belong to women’s exclusive discursive space, speculation as to how a male or female reader would have read it differently might prove a fruitful future exercise.” See Corine Schleif, Review of The Rothschild Canticles by Jeffrey Hamburger. Medieval Feminist Newsletter no. 15 (Spring 1993): 30. https://doi.org/10.17077/1054-1004.1639 |

| ↑6 | In my Master’s thesis, I discussed at length the different ways in which a female reader might approach the manuscript’s imagery in ways that would both resist dominant patriarchal ideologies and would be complicit with such ideologies. |

| ↑7 | Hamburger argued for German patronage based on German devotional literature, sermons, mystical writings and iconography that parallel images and texts in the Rothschild Canticles. Hamburger also did not rule out the possibility that the patron was an independent religious. See Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 161-162. Wybren Scheepsma questioned Hamburger’s insistence on a patron from the Rhineland and Hamburger’s contextualizing of the Rothschild Canticles’ text and imagery with German sources. Scheepsma posited that the Rothschild Canticles might have been produced in the Low Countries. See Wybren Scheepsma, “Filling the Blanks: A Middle Dutch Dionysius Quotation and the Origins of the Rothschild Canticles,” Medium Aevum 70, no. 2 (Fall 2001): 278-303. https://doi.org/10.2307/43632680 |

| ↑8 | See Hamburger, Rothschild Canticles, 197 for a complete transcription and identification of the sources of the text on fol. 72v. |

| ↑9 | Madeline H. Caviness, Visualizing Women in the Middle Ages: Sight, Spectacle, and Scopic Economy (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 3. The Rothschild Canticles illumination of the Coronation of the Sponsa has previously been linked to the development and exegetical context of the iconography of the Coronation of the Virgin by Philippe Verdier. See Verdier, Le couronnement de la vierge: les origins et les premiers développements d’un thème iconographique (Montreal: Institut d’études médiévales Albert-le-Grand, 1980), 84. |

| ↑10 | See Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 47-52 for the ways in which the iconography of these female figures conflates the wise virgin and the bride of Christ. |

| ↑11 | Corine Schleif has examined the gesture of grasping another person’s wrist in the specific context of the painted panel epitaph for Pastor Johannes von Ehenheim in the Church of St. Lorenz in Nuremberg and in the more general context of medieval art. Schleif asserted that being grasped indicates submission. See Schleif, “Hands that Appoint, Anoint, and Ally: Late Medieval Donor Strategies for Appropriating Approbation through Painting,” Art History 16 (March 1993): 16- 21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8365.1993.tb00511.x |

| ↑12 | Carol J. Clover, Men, Women and Chain Saws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992), 12-13. Christelle L. Baskins employed Clover’s discussion of cross-gender identification in a study of Boticelli’s Nastagio degli Onesi. See Baskins, “Gender Trouble in Italian Renaissance Art History: Two Case Studies,” Studies in Iconography 16 (1994): 15. |

| ↑13 | Though the Canaanite woman’s lowly status may have also been due to her race or class, I am choosing to focus on her gender, in keeping with Bynum’s interest in woman as symbol of inferiority. See Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 283. |

| ↑14 | Vern Bullough, “Medieval Medical Views of Women,” Viator 4 (1973): 485-501. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301662 |

| ↑15 | Joan Cadden, Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages: Medicine, Science and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 2-3. |

| ↑16 | Madeline H. Caviness, Reframing Medieval Art: Difference, Margins, Boundaries (Medford, MA: Tufts University, 2001), Chapter 4. http://dca.lib.tufts.edu/Caviness |

| ↑17 | Text cited by Bullough, “Medieval Medical Views of Women,” 492, and originally found in: Galen, On the Usefulness of the Parts of the Body (De usu partium), vol. 2 trans. Margaret Tallmadge May (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968), 628-629. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., 492. |

| ↑19 | Bynum, Holy Feast and Holy Fast, 284. |

| ↑20 | Clover, Men, Women and Chain Saws, 35-36. |

| ↑21 | Ibid, 48-53. |

| ↑22 | A transcription of portion of the relevant text on fol. 163r: Uir q(ui) Deu(m) amat ea(m) h(abe)t q(uam) amat nec eu(m) u(er)e dilig(er)e posset si eu(m) deligeret no(n) h(abe)r(e)t. Translation: A man who loves God has her whom he loves nor could he love him truly if he did not have him whom he loved. |

| ↑23 | The Sponsa’s gesture may be classified as the “chin-chuck,” an iconographic category suggested by Leo Steinberg. See Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (New York: Pantheon Books, 1983), 111- 116. |

| ↑24 | The notion of a “correction” was discussed by Madeline Caviness in a fall 1996 seminar, “Cathedrals and the Virgin Mary,” Tufts University, Medford, MA. |

| ↑25 | Sheingorn, Review of The Rothschild Canticles, 680. |

| ↑26 | Michael Camille, Review of The Rothschild Canticles by Jeffrey Hamburger, . Journal of Religion 72, no. 3 (July 1992): 429-431. https://doi.org/10.1086/488927 |

| ↑27 | Sheingorn, Review of The Rothschild Canticles, 680. |

| ↑28 | See Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 29, 214, 220. Hamburger also discussed fols. 164v, 165r, 165v, 16r, 162v and 163r (in that order) to investigate the use of images in devotional worship; see Hamburger, “The Visual and the Visionary: The Image in Late Medieval Monastic Devotions,” 134-6. |

| ↑29 | Transcription, fols.161r–161v: Ideo dicit Augustinus quod fortius animo habente caritate(m). Ite(m) fidele(m) amore(m) labor no(n) lassat q(uia), ut dicit Gregorius, nu(m)qua(m) est dei ot(i)osus; op(er)atur e(n)i(m) magna si est; si enim operari renuit, amor no(n) est. Translation: “Therefore Augustine says that nothing is stronger than a mind that has love. Likewise, labor does not weary faithful love because, as Gregory says, the love of [God] is never idle; for it does great works if it is [love]; for if it refuses to work, it is not love.” |

| ↑30 | Transcription, fol.162r–162v: Qui huius gustu inebriat(us) fu(er)it ad om(n)e opus bonu(m) hilarescit; dolet et non sentit; laborat et n(on) lacessit; derideret(ur) nec au(er)tit. Ite(m) qui amat no(n) laborat. Exemplu(m) de Iacob, Ge(nesis) xxxi: Nocte et die estu urebar et gelu et t(aliter). Et uidenbant(ur) ei dies pauci p(rae) amoris magnitudi(n)e. Si tot et tantos labores et uigilias sustinet homo pro amore carnali v(e)l lucro temp(or)ali, q(uo)d et quanta deberet sustin(er)e pro amore dei! Augustine. Si tanta portat nobis cupiditas, quare no(n) tanta portat caritas. Translation: “He who will have been made drunk by the taste of this is cheerful for every good work; he is in pain and does not feel it; he labors and does not blame; he is scorned and does not turn away. Likewise, he who loves does not labor. An example concerning Jacob, Genesis 31:[40]. Night and day I was burned by heat and cold, and so on. And the days seemed to him few in comparison to the greatness of his love. If a man endures so many and such great labors and sleepless nights for carnal love or temporal gain, how many and how great are the things he would have to endure for the love of God! Augustine. If cupidity endures such great things [i.e. labors] for us, why does not love endure such great things? |

| ↑31 | See Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 29 and 253 n. 88 for a partial transcription and translation of the text on fol. 164v. A partial transcription of the accompanying text to fol. 165r: Ite(m) si ille q(ui) turpit(er) amat n(on) p(otes)t cogitare n(isi) de eo q(uo)d amat. Translation: Therefore, he who loves lustfully cannot think on anything except on what he loves. |

| ↑32 | Transcription, fol. 165r: Crisos. Quid est dilig(er)e ex tota m(en)te? Ut o(mne)s sensus tui D(e)o uacent: sapi(enti)a intellectus cogitatio memoria. Q(ui) er(g)o alique(m) istor(um) (circum) temp(o)ralia occupat ia(m) no(n) ex tota m(en)te Deu(m) amat. Translation: What is “to love with one’s whole heart”? That all your senses should have leisure for God: wisdom, intellect, thought, memory. Anyone who occupies any of these in temporal affairs does not love God with his whole heart. |

| ↑33 | Transcription, fol. 165v-166r: Causa abstine(n)tie ama(n)dus est D(eu)s q(uia) p(ater) et fr(ater) n(oste)r est M(at.) xxiii patre(m) nolite vocare sup(er) terra(m); unus est pater n(oste)r qui es i(n) celis (id est) D(eu)s; si fili(us) naturalit(er) amat p(atr)em a q(uo) h(abe)t p(a)rte(m) corp(or)is, q(ua)nto magis debet amare Deu(m) q(ui) corpus (et) a(n)i(m)am ei(us) ex nihilo fecit. Aug(ustinus): ama(n)dus est gen(er)ator s(ed) p(rae)ponendus est creator. Translation: For reasons of abstinence God is to be loved because he is our Father and brother. Matthew 23: Do not call your father on earth Father; there is only one father, who art in heaven, that is, God. If a son naturally loves the father from whom he gets a part of his body, how much more ought he to love God who has made both his body and soul out of nothing. Augustine: one’s begetter is to be loved but one’s Creator should be put first. |

| ↑34 | Transcription, fol. 166r-166v: Ecc. vii: Dilige D(omi)n(u)m Deu(m) tuu(m) q(ui) te fecit i(n) tota a(n)i(m)a tua. S(e)c(un)do, ama(n)dus est Deus q(ui)a delitie i(n) eo i(n)ueniu(n)tur; delectat(i)o in partiu(n)cula creat(ura)e, q(ua)nta i(n)uenit(ur) in ip(s)o creatore. Aug(ustinus): q(ui)cq(uid) p(re)ter ip(su)m est, nihil est (et) dulce no(n) est; gustate ergo (et) uidete q(ua)m suauis est d(omi)n(u)s. Translation: Ecclesiasticus 7: Love the Lord thy God who has made you with your whole spirit. Secondly, God is to be loved because delight is found in Him. Delight is found in a little part of a creature—how much more is found in the Creator himself. Augustine: whatever is contrary to Him is nothing and is not sweet; taste therefore and see how sweet the Lord is. |

| ↑35 | Sheingorn, Review of The Rothschild Canticles, 680. |

| ↑36 | Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 296 n. 1. |

| ↑37 | Debra Higgs Strickland, Saracens, Demons, Jews: Making Monsters in Medieval Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2003), 73. |

| ↑38 | Karma Lochrie, “Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies,” in Constructing Medieval Sexuality, ed. Karma Lochrie, Peggy McCracken, and James A. Schultz, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 180. |

| ↑39 | Karma Lochrie, “Mystical Acts, Queer Tendencies,” 180-200. |

| ↑40 | While Hamburger identified the Christ figure on fol. 162r as a “figure emerging from cloud” (Hamburger, The Rothschild Canticles, 220), the nimbus on this figure’s halo points to an identification as Christ. |

| ↑41 | John Bugge, Virginitas: An Essay in the History of a Medieval Ideal (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff), 31. This comes from Bugge’s translation of De institutione virginis, civ, (Patrologia Latina 16.345). |

| ↑42 | Ibid.,, 31-32. |

| ↑43 | Karma Lochrie, Heterosyncrasies: Female Sexuality When Normal Wasn’t (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 1-25. |

| ↑44 | Robert Swanson, “Angels Incarnate: Clergy in Masculinity from Gregorian Reform to Reformation,” in Masculinity in Medieval Europe, ed. D.M. Hadley (London: Longman, 1999), 160-178. |

| ↑45 | Swanson took these three duties from Vern L. Bullough, “On Being a Male in the Middle Ages,” in Medieval Masculinities: Regarding Men in the Middle Ages, ed. Claire A. Lees, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 34. Bullough borrowed this categorization from David D. Gilmore, Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 223. |

| ↑46 | Swanson, “Angels Incarnate” 160-1. Jo Ann McNamara has thoroughly considered how men reacted to a loss of their masculine status by reasserting masculinity in new ways, though for a period that predates the Rothschild Canticles, from 1050 – 1150. Jo Ann McNamara, “The Herrenfrage: The Restructuring of the Gender System, 1050 – 1150,” in Medieval Masculinities: Regarding Men in the Middle Ages, 3 – 30. |

| ↑47 | Swanson, “Angels Incarnate,” 163. |