Tania Kolarik • University of Wisconsin, Madison

Recommended citation: Tania Kolarik, “From Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame to The Rivan Codex: How Late 20th Century Medievalism Shaped an Art Historian,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/RDWD7120.

In the summer of 1996, Disney released their classic animated film The Hunchback of Notre Dame to the great acclaim of a soon to be four-year old in Dayton, TX. My instantaneous love and fascination with the film led to its being the theme of my fourth birthday party—less than two months after its release.

Tania Kolarik blowing out the candle on her birthday cake during her 4th birthday party, August 1996. Taker of the picture with disposable camera currently unknown.

Much would change over the course of the year following my Hunchback themed birthday party, my parent’s impending divorce, moving into a single-wide trailer on my grandparent’s property, and the beginning of a multi-years long bullying campaign led by identical twins at my rural private Catholic School. I longed to be anywhere but trapped on the former family farm turned familial compound, so I read. Reading provided an escapism that nothing else in my life compared to. In one book I could be in a different universe, filled with magic, funny characters, powerful heroines, and to which I could return, time and time again, like the warm comfy feeling of visiting an old friend. David and Leigh Eddings’ Belgariad (1982–84) and Malloreon (1987–91) series, culminating with the collection of background materials in The Rivan Codex (1998), immersed me further into a world of fantasy, but one based on real medieval societies and cultures.[1] Each country was inspired by different types of cultures and peoples: Vikings, crusading knights, Mongols, and even the Roman Empire. In this reflective essay, I consider the impact of these works of medievalism on my own path toward becoming an art historian and confront the inherent and often explicit racist narratives in both the Hunchback and the Eddings’ works.

Dayton–Eastgate, TX, ca. 1990s

In 2025, Dayton, TX is a forty-minute drive—if you’re lucky—away from downtown Houston, and due to the recent opening of State Highway 99 is projected to grow by 27,000 residents in the coming years as it is subsumed into the great suburban sprawl.[2] In stark contrast, the town in the ‘90s–‘00s was characterized by the old American Rice Growers’ rice dryer built in 1949,[3] the nearby underpass that still floods in heavy rains, and the urban center surrounded by the beginnings of the Piney Woods to the north, the Trinity River bottoms to the east, and fields populated by cows, St. Augustine grass, rice, maize, or soybeans to the south and west. Until my parents divorced when I was 5, I lived “in town” near-ish to the rice dryer, but after their divorce my mom, younger sister, and I moved to the unincorporated (and still technically part of Dayton) area known as Eastgate.

Eastgate was supposed to be its own town. Populated by a mixture of Czech and Polish Eastern European immigrants, all devotedly Catholic, they built their own parish church dedicated to St. Anne in 1919.[4] I grew up going to this church, so did my parents, and my grandparents, etc., and I am in some way related to all the founding families through blood or marriage. But besides the church, the hall, the cemetery (where non-parish members aka non-Catholics are buried outside the fence), and—by the time I was born—a long gone general store, nothing else that would make a town ever appeared. My family stopped farming by the 1960s and turned the land into a familial compound centered along a private dirt road my grandfather and great-uncle constructed out of nothing. It was along this road, next door to my grandparents, that my mother put a single-wide trailer and where we would live for the next four years.

Me + Disney + The VCR

Like many children of the 1990s I was regularly handed over to the in-home babysitter—the television, VCR (videocassette recorder),[5] and a stack of mostly Disney VHS (Video Home System) tapes. My fascination with Disney films that were medieval was a mixture of chance (i.e. whatever my parents [aka my mom] bought for me) and the requests for films that were advertised during television commercials at the time. I remember watching the classics: The Sword in the Stone (1963), Robin Hood (1973), Sleeping Beauty (1959), and I was so taken with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) that around age 3 I watched—to the exasperation of my mother—seven times in a row, one for each dwarf![6]

As far as my first interaction with The Hunchback of Notre Dame is concerned, I must have asked for it based off of a television commercial or Disney VHS preview since I was definitely not taken to the movie theater to see it in person. After my disastrous first movie theater outing earlier in the year to see Muppet Treasure Island (1996), I was not taken to a movie theater for at least another two years. However I ended up first watching the film, I was mesmerized. Based on Victor Hugo’s 1831 French Gothic novel of the same name, Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a “kid-friendly” story about the physically disfigured bell ringer of Notre Dame in Paris, Quasimodo, who saves the Roma “gypsy” Esméralda and the city of Paris from the sinister clutches of his guardian Count Frollo with the help of the solider Phoebus and gargoyle friends, Victor, Hugo, and Laverne.

Esméralda was my favorite character—attested to by her prominently featured on the shirt I wore during my fourth birthday party.

Esméralda Christmas ornament, purchased July 2024 from Sainte-Chapelle in Paris. Photo: Author.

I loved how sassy and disobedient of the male clergy and of Count Frollo’s authority she was, and her clothes were such a hit that I was her for Halloween and wore her costume regularly until I grew out of it. It is this fascination with Esméralda’s clothing that also extended toward the sash she threw at Count Frollo, which he holds, rubs against his face, and throws into a fire. All the while singing that Paris will burn if she will not be his. I could just imagine, even as a child, how that sash would feel, lightweight, a silk chiffon-like fabric with gold thread. This fixation on clothing, costume, imagining what an animated sash would have felt like if it was a real piece of fabric has played deeply into my own academic scholarship on medieval clothing and textiles. I now use these same skills when looking at painted clothing on figures within a wall fresco or altarpiece, imagining what those fabrics could have been made of and potentially felt like if based on real textiles.

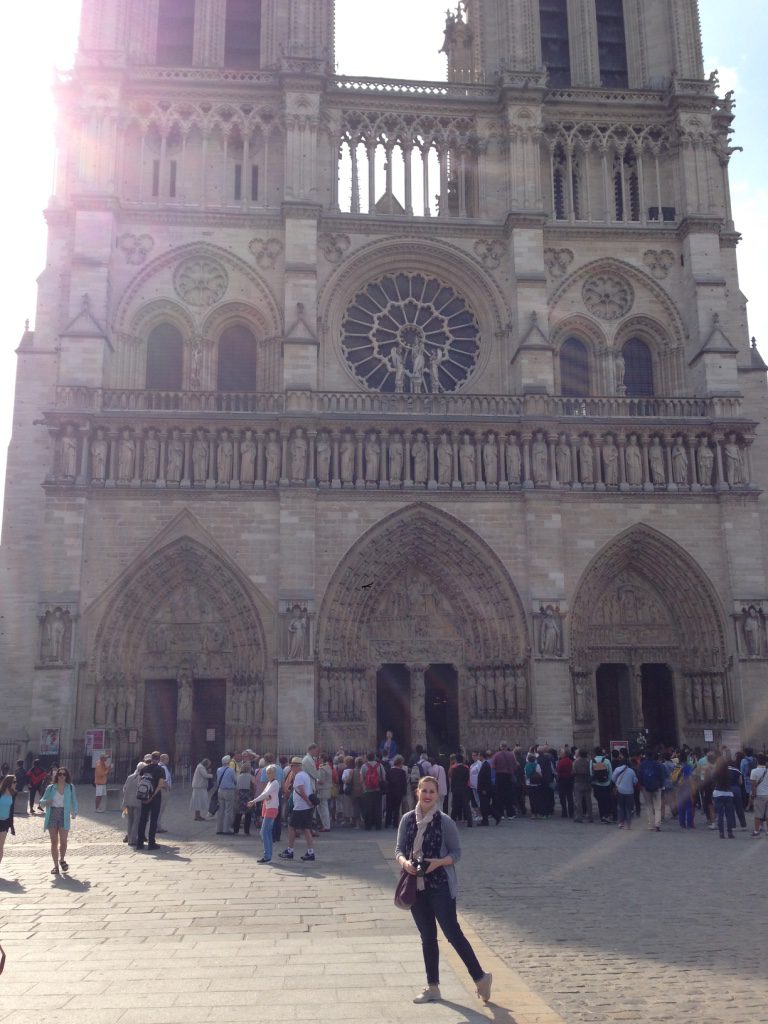

My other favorite part of film was Notre Dame itself—it was alive. This life was quite literal as the gargoyles would spring to life, Quasimodo named the bells, and it was very clear from the beginning of the film that the sculptures of the saints and of the Virgin Mary were always watching as they prevented Count Frollo from killing Quasimodo as an infant. Another aspect of the life of the cathedral came through the colors of one of the stained glass rose windows reflecting down on Esméralda while she sings “God Help the Outcasts.” I wanted so desperately to feel that light on my own skin and was so happy to find out that Notre Dame was a real place that I could go one day. And I did. In 2015, during my first ever art historical research trip to Europe and first trip out of the United States, my MA advisor, Mickey Abel, showed my fellow MA students and I around Paris, including a pre-fire Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Paris.

Tania Kolarik in front of Notre Dame in Paris, June 2015. Photo: Jena Jones.

However, during my childhood the only realization of Notre Dame into my life was limited to watching its animated rendition through the television via the VCR.

“You Can Read”

While I lived in Eastgate and my address said “Dayton, TX,” I never quite belonged in either place as I went to private Catholic school thirty minutes away in the next town to “get a better education” and my cousins went to the public schools in Dayton. While this school may have been on some levels “better” than my public-school alternative, it was no prep school and many of the teachers did not even have four-year college degrees. During this time, I was inherently liminal, occupying space betwixt and between my parents and grandparent’s homes, and being regularly bullied and ostracized at my private school by a pair of identical twins who placed me in their crosshairs. The bullying intensified during the second grade from the twins, other students, and my teacher to the point where I truly skipped that grade because I never went. The third and fourth grade years were slightly more tolerable due to having better teachers and discovering a deep love for reading, but until I moved to public school in another city where my mother worked at a chemical plant I was constantly overwhelmed by unrelenting thoughts of suicide.[7]

It was around the time of not going to second grade and starting third grade that my mom tricked me into becoming a reader. The Harry Potter book series was all the rage and my mom had read and owned all of the books that had been published, likely through The Prisoner of Azkaban (1999). While I could read, up until that point I wasn’t that into reading and only did the bare minimum of what I needed to do for school. My mom, when she was off from work, started reading The Sorcerer’s Stone (1997) to me chapter by chapter, and once she could tell I was clearly invested in the story she stopped mid-chapter and went off to do laundry. I protested loudly; how could she stop reading to me mid-chapter? I needed to know what happened next! What I heard back was something along the lines of “you can read.” And so, I did. Once I finished The Sorcerer’s Stone I moved on to The Chamber of Secrets (1998), quickly followed by The Prisoner of Azkaban, but I needed more.

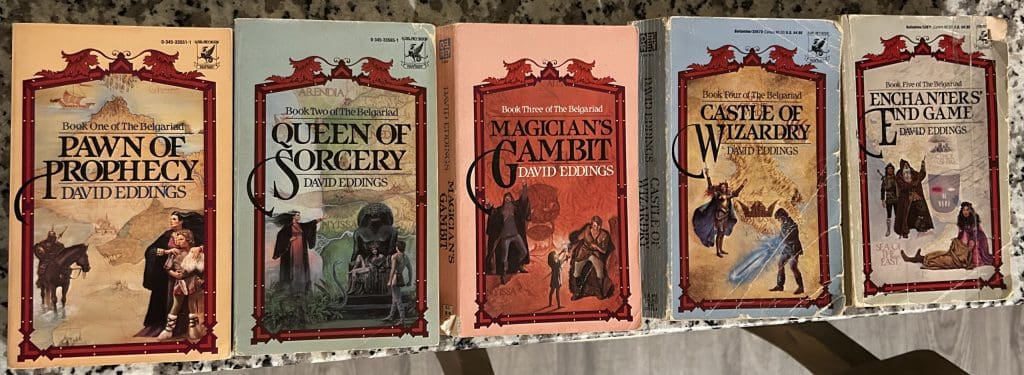

My private school library was severely lacking in their selection of reading material, especially the fantasy genre introduced by Harry Potter, but my mom—a voracious reader of sci-fi/fantasy—had some mostly age-appropriate options for me to read. This is when I was introduced to the work of David and Leigh Eddings, whose five-book Belgariad series brought me into a universe that seemed to me at the time to be completely disconnected from my own.

David and Leigh Eddings five-book Belgariad series, worn paperbacks. Photo: Author.

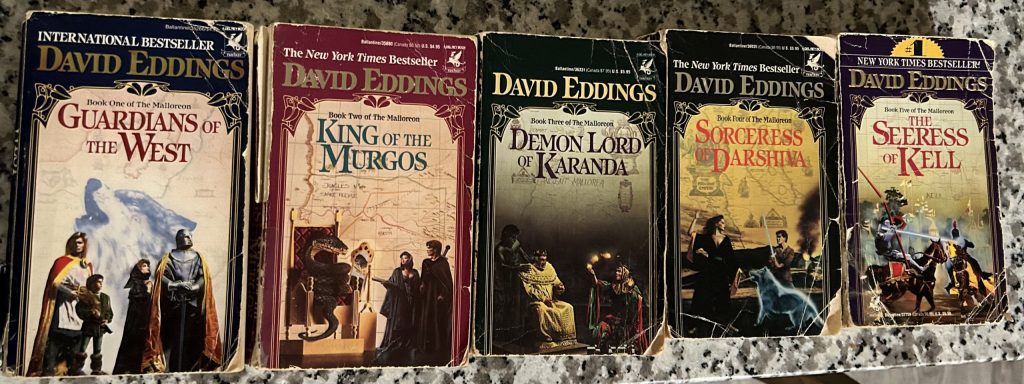

While Harry Potter was set adjacent to my own reality, the Belgariad was in a world that didn’t look or feel like mine, with maps of the world at the beginning of each book to geographically ground the reader in this place of its characters. The story centers on the hero character of Garion, who at the beginning of the series is a child destined by the prophecy (a living[?] entity) to fight the evil god Torak, in a good vs. evil final showdown for future of the planet. Overall, a coming-of-age story, Garion is aided in his quest by his many times removed great-grandfather Belgarath and great-aunt Pol (aka Polgara) who are extremely powerful sorcerers, along with several other very colorful characters who offer different types of expertise along the hero’s journey. The story, along with many of the original characters, continues in the five-book sequel series of the Malloreon.

David and Leigh Eddings five-book Malloreon series, worn paperbacks. Photo: Author.

In addition, there are large prequels each dedicated to the lives of Belgarath and Polgara.[8]

Besides the powerful sorcerers, the other characters tended to exhibit the personalities of their “peoples” or countries. For example, Barak is a large red-headed man from Cherek and a great warrior who, when the main character of Garion is in danger, literally goes berserk and turns into a bear much like those in Norse mythology. While the other Chereks did not turn into actual bears, their kingdom was in the north and they were known for being great sailors and fierce warriors, much like most surface level modern peoples’ understandings about the Vikings. Another example rooted in medieval stereotypes is the practically destroyed kingdom of Arendia that due to chivalry has torn itself to pieces. This feudalism on steroids has mounted knights who battle against each other in jousting tournaments, professing floral poems about love in the realm of the Le Roman de la Rose, Robin Hood-esque characters who are proficient in archery, and are constantly dueling over injuries to ones’ pride. It is this kingdom, in particular, that is the least societally functional and the most stereotypical example of public perception about what the Western medieval world was really like.

The world building process chosen by the Eddings is documented in their 1998 book The Rivan Codex. Functioning as a how-to manual for creating and writing your own fantasy saga they propose assembling a group of characters who will embark on a hero’s quest as the main driver of the plot. They also discuss how they looked back through history for inspiration shaping the characteristics of different countries/kingdoms. By basing groups of people somewhat in reality they created a familiarity between the reader and the imaginary world they crafted. Through their use of these medieval-ish societies and environments I was able to completely lose myself into the story. The level of distraction that sci-fi/fantasy books provided from my actual life circumstances really helped save my life in a way.[9] Instead of doing nothing and being an easy target during recess or after the class lesson was done for the day, I could block the outside world out and read. This also made the transition into public school easier because if I was feeling anxious about meeting new people, I could pull out whatever book I was reading and just disassociate from everything happening around me. It is also clear that these books deeply impacted how I viewed the medieval world, one that many of us grew up thinking—full of backward, dirty, and full of dumb people who were overly religious—very much like the Eddings’ kingdom of Arendia. This view and biased impression of the medieval world colored my first interaction with the art and architecture of the real Middle Ages during my first art history class.

Becoming a “Medieval” Art Historian

I took my first art history class my senior year of high school for AP credit and the medieval world was of little to no interest to me. I remember being disappointed in all of the extremely religious artworks—way too much Jesus—and not even my childhood love for Notre Dame in Paris could make me that excited about it. At the same time, learning about the history of art sparked something deep inside me. I loved it, and even though I wasn’t that excited about the medieval, I absorbed everything, resulting in scoring a 5 on the AP art history test and the only AP exam I ever scored that top mark on. However, I was never going to “make a living” if I “didn’t have a Bachelor of Science degree,” which is why I have an undergraduate degree in Biomedical Science. After being extremely unhappy, I found my way into an art history MA program at the University of North Texas (UNT) where a chance encounter with Otto Brendal’s “Prolegomena to Roman Art” sparked an interest in ancient Rome.[10] As there was no classicist on faculty I “compromised” by working on Late Antique Rome, dragging me into the beginnings of the medieval world. Though once I began learning more about the Middle Ages, I couldn’t get enough.

Re-Examining the Past

It was during my MA program at UNT and before my 2015 trip to Paris that I re-watched Disney’s Hunchback as an adult. The part of the film that was most shocking was Count Frollo’s scene where he insinuates wanting to sexually violate Esméralda and if he can’t have her then he will burn Paris to the ground. That rocked my entire understanding of the film, on top of the clear othering of Esméralda with her olive skin that marked her as Romani, which is interestingly not used on the figure of Quasimodo as his disfigurement does the othering instead of skin tone even though his mother is also Roma. The film makes the racialized power dynamics even more clear as the Roma are kept separate from the rest of white Paris belowground in the catacombs when they’re not functioning as entertainment. It’s only once Frollo is dead and gone that the city can be integrated into a unified multi-racial society aboveground in the sunlight as Quasimodo—and the Romani—are accepted by citizens of Paris. While this newfound interpretation of the film began to coalesce in my brain it still took a bit longer for me to begin reconsidering the way racial stereotypes worked in the sci-fi/fantasy novels of my childhood and young adulthood.

It was only after beginning my Ph.D. program at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and engaging in the scholarship coming out from discourses surrounding medieval race that I was first exposed to J.R.R. Tolkien’s racialized stereotypes, between the elves and the orcs, white and black, good and evil. While I tend to watch The Lord of the Rings film trilogy once a year and have read The Hobbit a couple of times, I have only read the full trilogy once and at the age of 10. It is clear, now, that Tolkien’s racialized blueprint for how to depict the good vs. bad guys had seeped into my own understanding of fantasy novels that I never even thought to question it as I got older.

This “baked in” use of white and black skin for signaling good vs. evil is also part of the Eddings’ works, especially in the first Belgariad series. The main villains of the story, the Murgos, are “dark” peoples who follow the evil god Torak, and while the Eddings do not explicitly state that they have dark skin it is implied, describing one of the Murgos the main characters encounter as “dark, burly man.”[11] However, even they did complicate the narrative set by Tolkien with the inclusion of some lighter-skinned people of color as part of the “light/good” side, such as the Algar peoples of Algaria who are based on the Mongols. In the second part of the saga with the Malloreon series, the dark-skinned Murgos as a people face redemption as they are attempting to further interact with the world after their evil god was killed by Garion at the end of the Belgariad. It is only through the leadership of their new king, revealed to be secretly half-white and the half-brother of another character, who is able to accomplish this. Overall, I am still struggling, developing, and re-developing my thoughts about the Eddings’ works as their books were an integral part of not only my childhood but my ability to survive that time in my life. I hope that after finishing my dissertation I can take some time to visit these characters once again, these old friends, but with a new perspective grounded in my understandings about race and the medieval world.

Concluding Thoughts

While I have always been aware that medievalisms were part of my childhood and integral to what entertainment (books, movies, tv series, etc.) I prefer to consume, until the call for this special issue of Different Visions I had never attempted to fully come to terms with how my own academic research interests into the medieval world have been shaped by the content I greedily inhaled as a child and young adult. Thinking back on my reaction to medieval art in high school, it was likely a mixture of rejecting my Catholic upbringing and a skewed view of the Middle Ages shaped by the books I liked to read. While set in medieval-esque realms, if you took the magic and fantastical creatures out of the narratives what was there? It was only through my own quest to find myself that I discovered that the real Middle Ages is just as, if not more, interesting than the fantasy. Similar to the Eddings providing more depth and nuance into the characters marked as “evil” in the transition from the Belgariad to Malloreon series, I think that is where we are all in some way as scholars—attempting to provide more depth and nuance into the Middle Ages, a world that has been for so long shaped by those who only see black and white.

References

| ↑1 | Some of the books are labeled as being written by David Eddings alone, but it is clear from his own writings and the fact that later books include Leigh’s name as co-writer that they both contributed and wrote these books together. So, I will refer to them as being co-written throughout. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Russell Payne, “Dayton projects over 27,000 new residents coming to area,” The Vindicator (Liberty, TX), September 7, 2022. |

| ↑3 | “End of an Era: Historic rice dryer in Dayton being demolished,” Bluebonnet News (Liberty, TX), March 20, 2024. |

| ↑4 | “Historical marker unveiled at St. Anne’s Catholic Church,” Bluebonnet News (Liberty, TX), October 28, 2020. |

| ↑5 | While we called it a “VCR” it was probably just a VHS player as I doubt we had the money for one that actually recorded anything off of the television. |

| ↑6 | This may have been an early ADHD induced hyperfixation, a condition I have only been diagnosed with in the past year. I also was a fan of many other ‘90s Disney classics, such as Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992), The Lion King (1994): the theme of my third birthday party, Hercules (1997): the theme of my fifth birthday party, and Mulan (1998). |

| ↑7 | While bullying and child suicide was not a major of topic conversation when I was growing up in the ‘90s–‘00s, if this sounds similar to your child or someone you know please check out: stopbullying.gov; GLAAD’s anti-bullying resources for students; and the Suicide Prevention Resource Center’s resources for children 12 and younger. |

| ↑8 | The character of Polgara the Sorceress was and is a favorite character of mine. While she can be sweet, kind, and nurturing she is also fierce, smart, dangerous, intimidating, beautiful, and powerful. Polgara was everything I was not as a child, especially since I had so little power and control over my own circumstances, and I thought she was an ideal of feminine strength. Though, once I got older and re-read the books over and over again it became clear that while she was had all those characteristics and was powerful, she was still subject to life circumstance that we all are tied to and cannot actually control. |

| ↑9 | Other authors of sci-fi/fantasy books I have read include, but not limited to: Anne McCaffrey, Terry Brooks, Frank Herbert, and George R.R. Martin. McCaffrey’s Dragon Riders of Pern series was also especially influential. |

| ↑10 | Otto J. Brendal, “Prolegomena to a Book on Roman Art,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 21 (1953):9–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/4238629. |

| ↑11 | David [and Leigh] Eddings, Pawn of the Prophecy (New York: Del Rey, 1982), 38. |