Amelia Hope-Jones • University of Edinburgh

Recommended citation: Amelia Hope-Jones, “Male Friendship as an (eremitic) way of life,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/ADYX1641.

Introduction

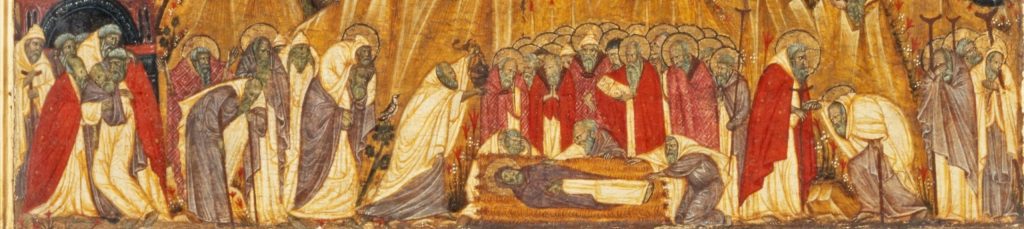

Within a dense narrative image of eremitic life, made in Italy ca.1295, two small details depict close friendships between pairs of monks. In a gesture of strange and striking intimacy, one monk carries another on his back. The narrative containing these details forms the central panel of a painted tabernacle, currently on display in the Scottish National Galleries, Edinburgh (Fig. 1).[1] It shows more than a hundred saints and hermits inhabiting a mountainous desert, with the funeral of a saint and a monastery at its lower edge. The pairs of carrying monks appear among many other hermits who descend the mountain in groups or pairs to attend the funeral. The composition of the central panel has no clear antecedents in Italian or in Byzantine painting, though it is very similar to later Byzantine and post-Byzantine narrative icons. However, in its details, particularly the interactions between individual monks, it is clearly linked to and ultimately derives from eleventh-century byzantine manuscript illuminations.[2] The seemingly incidental figural motif of the carrying monks, as represented in a byzantine manuscript illumination and in the Edinburgh Tabernacle (and which are also present, little altered, in later Italian and byzantine paintings), are the visual sources on which this paper is based. I approach them via Foucault’s later writing, especially his 1982 interview, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” placing them in dialogue with his thoughts on friendship, queer community, and ascesis. In doing so, I propose a queer re-reading of these provocative, perplexing figural details, asking what they might reveal about the eremitic way of life and the intimacies it engenders.

Fig. 1. Tuscan, Scenes from the Lives of the Hermits (central panel); The Passion and Resurrection of Christ (hinged lateral panels); Redeemer and Angels (pediment), ca.1295 (“The Edinburgh Tabernacle”) National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh (photo: by permission of the National Galleries of Scotland). For a zoomable image, please see: https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/8697.

“Friendship as a Way of Life” is the title of a short interview between Foucault and the French magazine Le Gai Pied.[3] In it, Foucault discusses the “problem” of friendship, which he positions at the heart of the queer challenge to a culturally assumed heteronormativity. He discusses the radical potential of new forms of relationality among men, including but not confined to the homosexual, which escape accepted forms of institutional, familial, or professional relations. These kinds of intimacies, which he describes as “unforeseen lines of force,” open the possibility for previously unimagined, and thus “disturbing” modes of life and forms of love between men. Foucault has been criticized by later scholars for his almost exclusive focus on men and male sexualities, an objection he acknowledges in the interview.[4] Yet he makes the case for a gendered approach, arguing that, historically, “Man’s body has been forbidden to other men in a much more drastic way.”[5] He discusses the kinds of intense and devoted friendships that emerge among men in extremis, for example amidst the wretched suffering of warfare. These emotional ties and affective intimacies are not, in themselves, evidence of homosexuality; they demonstrate the powerful, sustaining necessity of life, and love, between men. Foucault sees the possibilities inherent in male communities that cut across boundaries of age, social status or identity and encompass “a multiplicity of relationships.” For him, such relationships permit the creation of entirely new cultural and ethical frameworks, an all-encompassing “way of life.”

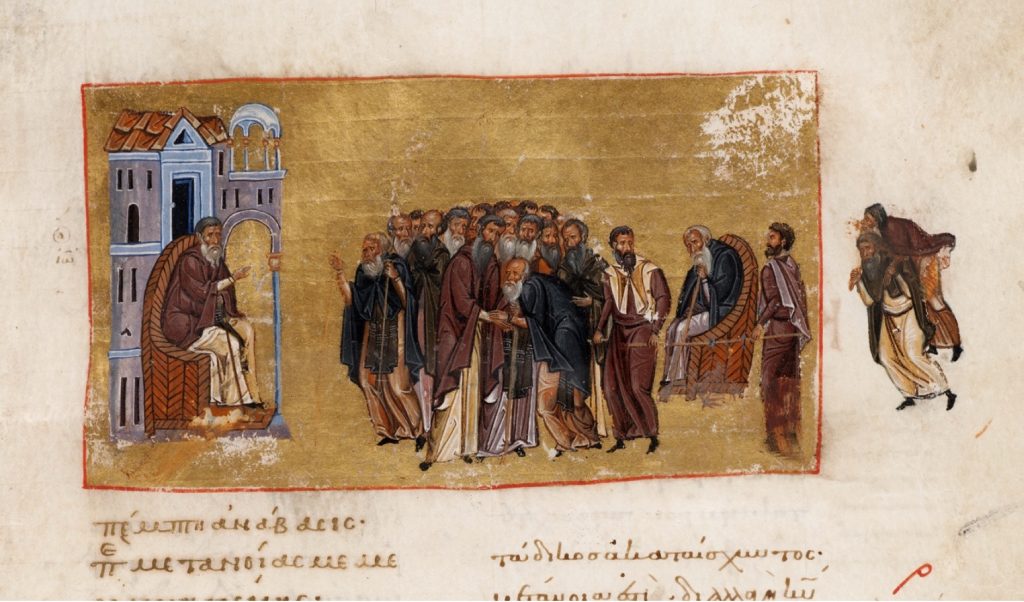

Fig 2. Monks approach John Climacus, fol. 41r, “On Penitence,” The Heavenly Ladder, late eleventh century, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Gr. 394 (photo: © Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana).

The asymmetric pairings of monks repeated in the visual sources (a motif I’ll refer to as the “carrying motif”) seem to speak directly to the forms of relationality described by Foucault. They are also exclusively male. There is an inescapable and touching intimacy between the monks—carrier and carried, potent and submissive—which gestures towards, without insisting on, the erotic. These relationships and interdependencies emerge in, and are defined by, the environment and conditions of ascesis that are particular to the desert. In both the primary case studies considered here, the carrying motif is a detail of a larger narrative concerning monastic or eremitic life. These are a late eleventh-century manuscript illumination of the Heavenly Ladder (Vat.Gr.395, fol.41r) now at the Vatican Library (Fig. 2), and the late thirteenth-century painted tabernacle introduced above, currently in Edinburgh, Scotland. I also discuss later Italian and post-byzantine paintings, dating to ca.1500 and ca.1700 respectively. While prioritizing the visual sources, I read them in relation to relevant premodern texts, especially the Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus, a foundational treatise of Orthodox monastic spirituality seemingly closely linked to the origins of the iconography.[6]

The Heavenly Ladder describes the ascent of the individual soul up thirty-three “rungs” of the Ladder of Divine Ascent, from the initial conversion to the religious life, through the practice of the virtues and struggle against the passions, to eventual mystical union with God.[7] It was written by John, abbot of the desert monastery of St Catherine on Sinai, ca. 600, as a manual of spiritual instruction for coenobitic monks. Peter Brown describes the Heavenly Ladder as the “undisputed masterpiece of byzantine spiritual guidance” and the culmination of the ascetic tradition at the end of antiquity.[8] John Climacus wrote from personal experience as a hermit and also drew on an influential body of ascetic literature dating from the early fourth to late sixth centuries.[9] While many of these sources, such as the collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers known as the Apopthegmata Patrum, and the Collationes of Cassian, were widely disseminated across the early Christian world, the Heavenly Ladder was not translated into Latin until the late thirteenth century, and not widely known in the West until the fifteenth.[10] Yet, the text represents an important synthesis of the ascetic tradition and an apparent impetus to the creation, and subsequent repetition, of the carrying motif that is my focus in this essay.

While the contexts of their reception and viewing necessarily differ, the two primary examples considered here, made in eleventh-century Constantinople and late-medieval Italy, invoke a paradigmatic and authoritative eremitic ideal. They each depend on the early ascetic literature, either directly, as in the case of the illumination of the Heavenly Ladder, or indirectly; the Edinburgh Tabernacle does not illustrate a singular narrative, but rather an apparent synthesis of multiple textual and visual sources. While the origins of Christian monastic life were universally traced to the third and fourth-century inhabitants of the deserts in Egypt and Syria, the monastic tradition developed separately in Latin Europe and in Orthodox Byzantium.[11] Each gave different texts and ways of life priority. In the East Roman empire, monastic foundations were established under independent typika (charters) and frequently accommodated both coenobitic and more solitary ways of life within a broadly eremitic context.[12] A more centrally controlled and tightly regulated coenobitic model came to dominate in the Latin West. Benedict of Nursia’s influential Rule (early sixth century) became the institutional expression of the eremitic ideal and the Church retained nominal oversight over monastic Orders.[13] Yet despite these important religious and contextual differences—which lie beyond the scope of the present article—the early, exemplary forms of monastic life represented in the images and recorded in the literature are pervaded by a sense of alterity, liminality and extreme ascetic practice.[14] The images acknowledge an eremitic ideal that originates in the early Christian past and help to reiterate, or perpetuate, the same ideal in the (historic) present.

The first section of this article sets out my approach to the themes of friendship, ascesis and the eremitic life raised by the visual sources, in relation to Foucault and to more recent scholarship. The second looks closely at the manuscript illumination of the Heavenly Ladder as a case study, considering its meaning in relation to the text of which it is a part and its subsequent repetition in later, more complex narrative images of the eremitic life. The third and final section turns to the carrying motif in the Edinburgh Tabernacle, most likely derived from an illuminated manuscript of the Heavenly Ladder similar to Vat.Gr.395. Here, I consider more closely the meanings that might have attached to this motif, and to the eremitic life more generally, in the late thirteenth-century context of its making.

Throughout this essay, I consider the possibilities that emerge when we attend to the “fundamental queerness” of the eremitic endeavor.[15] I have followed Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s now-classic definition of queerness as an “open mesh of possibilities, gaps, overlaps, dissonances and resonances, lapses and excesses of meaning when the constituent elements of anyone’s gender, of anyone’s sexuality aren’t made (or can’t be made) to signify monolithically.”[16] Among communities of ostensibly chaste monks in the desert, sexuality is insistently present, and ascetic practice pushes up against the limits of what can be counted as sexual desire. Queering the eremitic way of life allows it to be approached not as a clearly-defined “thing” but as a strategic marginality; “a potentially privileged site for the criticism and analysis of cultural discourses.”[17] I defend its willful eccentricity and, following Foucault, its radical possibility as a way of life.[18] The carrying motif, which reappears so insistently in the visual sources, operates as paradigmatic example of “queer” eremitic relationality, opening up broader issues of premodern sexuality and ascesis.

Foucault and queer ascesis

While Foucault has been well-mined in queer theory, his work has been useful to me for its consideration of male friendship and Christian conceptions of sexuality and the self. “Friendship as a way of life” reflects Foucault’s belief in the radical potential of love between men, not so much as a non-normative sexual act or identity, but as an antidote to sexuality as a mechanism of power. He described how, through the practice of penitential confession, sexuality became “the seismograph of our subjectivity,” an effective mechanism in the production of knowledge and power.[19] Foucault wanted to show that the conditions of the present – what Butler has called the “epistemic regime of presumptive heterosexuality”[20] – are neither inevitable nor natural.[21] In identifying sexuality as a key aspect of biopolitics, he advocated ways to escape or resist its essentializing force, including through friendship. In the years before his death, he increasingly saw male friendship, historically more tightly controlled than friendship between women, as simultaneously encompassing and surpassing sexuality in a way that imagined the creation of entirely new social forms.[22]

Foucault attended to the “details and accidents” of history rather than searching for an overarching metaphysical logic.[23] He positioned the body as the site of historical truth and drew attention to ascetic endeavor as a crucial method of self-surpassing transformation. Foucault’s use of the term ascesis was not limited to those archetypical religious practices of self-denial and self-injury; it included the broader and more positive sense of an ongoing, transformatory exercise of self upon self. He saw the goal of ascesis: “to get free of oneself, and to reconstitute oneself in a calculated encounter with otherness.”[24] For Foucault, homosexuality was also a kind of ascesis, because it was not defined by the supposed liberation of a repressed and final truth about an individual’s desire, but found instead in the constant movement towards something beyond the self, new forms of pleasures, coexistences, and attachments; “a manner of being that is still improbable.”[25] In his consideration of sexuality as a key aspect of subjectivity, he saw the Christian requirement to know and renounce oneself – the confessional operation of self upon self – functioning through complex relations with others.[26] Relating this “technology of the self” to contemporary social contexts, he described the act of being “‘naked’ among men,” the disclosure and renunciation of the self that constitutes ascesis, as a radical possibility, surpassing the limitations imposed by institutionalized relations, family, profession and obligatory forms of association.[27] He saw deep and affective friendships, invented anew and unmediated, as an effective means to escape disciplinary control. Such friendships, I suggest, are reflected in the carrying motif, the “detail and accident” of art history which is the subject of this study.

The “encounter with otherness” Foucault saw at the heart of ascesis is directed, for the Christian ascetic, towards God. Yet the movement beyond the self also happens between men who share this journey, which is neither purely painful nor entirely solitary. Foucault saw the powerful potential of pleasure as a means of surpassing the limitations of desire and the associated restrictions of identity. He spoke about pleasure as “virgin territory,” an event at the limit of the subject, neither inside nor outside, neither of the body nor of the soul.[28] Writing about his own contemporary historical moment, he described new forms of bodily pleasure – decentered, degenitalized sexuality, including sadomasochistic practices (S/M) – as a means of facilitating desubjectivization, a fracturing of the self which shatters identity.[29] This has a political dimension, in that it subverts hierarchies of power or control established on the basis of a discrete (sexual) identity – what Leo Bersani has described the disciplinary productivity of power in the guise of sexuality – and constitutes a stance which David Halperin characterized as inherently communal and fundamentally queer.[30] Halperin wrote at length on what he called Foucault’s “queer ascesis”; “an ongoing set of practices with oneself in relation to others that subvert, or move beyond, institutionalized relations and modes of being.”[31] The counterintuitive pleasures of discord, fracture and the surpassing of the self in a collective penitential context have been seen to possess a correspondingly subversive potential. In the extreme environment of the desert, beyond the safety of the monastic enclosure, new forms of relationships and alternative kinds of pleasure might be invented that resist teleological thinking and refuse the necessity of gratification. They emerge as “queer” disruptions, a movement towards transformation that is never fully attained.[32]

The apparent sadomasochism of ascetic practice, particularly among the earliest desert saints, has long fascinated scholars.[33] It is closely linked to the seemingly perverse relationship between physical punishment and spiritual advancement found in hagiography and noted by Robert Mills; “Pain, experienced as delight by the saints, is not a symbol of the fleshliness that they wish to disavow, so much as a symbol of their willingness to embrace the flesh as a source of power and subjectivity.”[34] The queer, subversive delights of eremitic ascesis, a kind of slow martyrdom, have been discussed in important contributions by Karmen MacKendrick and Virginia Burrus.[35] MacKendrick’s Counterpleasures picks up Foucault’s understanding of ascesis as a means of disrupting relations of power. It reads the early ascetics’ apparent turn against the body as a paradoxically carnal gesture that radically problematized the hierarchicality and misogyny of patriarchal Christianity.[36] Burrus’s Sex Lives of Saints highlighted the queerly erotic way of being that is instantiated in the desert, the “incipient homonormativity of ascetic solitude” and the passionate, transgressive love that animates the friendships of hermits.[37] The humiliation, punishment and self-negation experienced in the intensely physical trials of ascesis have been read as the source of potential “jouissance” – the pleasure that derives from the shattering of a unified self, and directly linked to contemporary expressions of S/M practice such as those discussed by Foucault.[38]

Studies of premodern sexuality have highlighted the (homo-)erotic potential of monastic community, including among the early desert fathers. Where traditional historical studies have construed monastic friendships as highly regulated and strictly anti-erotic, this approach has been problematized since John Boswell’s pioneering Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality.[39] Boswell did much to reconsider and uncover the evidence, arguing that same-gender love was widespread in Christian communities, and that it was neither consistently nor universally condemned. Since then, our understanding of male monastic friendship has been considerably expanded and nuanced. The work of Derek Krueger and Mark Masterson on byzantine monasticism, and Robert Mills on twelfth-century France, are particularly relevant to the present study.[40] Roland Betancourt’s recent Byzantine Intersectionality discusses the queer communities that formed in early Christianity and draws connections with contemporary marginalized identities. He reminds us that queer desire encompasses, “other relations beyond “straight,” between nonbinary, transgender, and cisgender persons, while understanding that queer desire and intimacy need not always be affirmed or confirmed by sexual intercourse.”[41] Female, transgender and nonbinary saints are prominent in the history of early Christian monasticism and Betancourt, among others, has done important work in recovering their subjectivities, often erased or omitted from the historical record.[42] However, the focus of the present article, reflecting the content of the visual sources, is restricted to male hermits who are ostensibly chaste. The non-necessity of the sex act in queer desire is especially important in this context. It accords with Foucault’s emphasis on the “disturbing” power of male friendships, which he saw located in their intimacy and not reducible to the act of sex.[43] It also reflects the concerns of premodern ascetic literature, which treats sexuality as something real and present in the body, even where it does not manifest in acts, no matter the sexual object.[44] Following Mills, I intend for a queer reading of male monastic friendships to operate as a “third term,” beyond the binaries of gender and sexuality.[45] I prioritize the rich interpretative potential of an imagined, artistic subject and, in doing so, hope to contribute something to Betancourt’s articulation of disenfranchised identities and marginalized subjectivities.[46]

With the notable exception of Robert Mills, existing scholarship on queer desires in medieval monasticism has tended to prioritize the written sources.[47] Art historical studies of eremitic landscapes, which appear primarily in Italian and byzantine art, have tended to follow a traditional, anti-erotic interpretation of monastic friendship and regard the images as examples of strict ascetic virtue.[48] My initial encounter with the case studies I examine here is indebted to the art-historical research of John Martin and Alessandra Malquori.[49] However, the present study does not, for reasons of space as well as approach, attempt an iconographic survey of the carrying motif; nor does it claim to ascertain a definitive, historically-located meaning for the motif itself. Instead, it prioritizes the close reading of selected visual details that might be considered minor or incidental, complicating existing interpretations of these images, including my own, and attending to the imaginative and critical possibilities that emerge from them. In suggesting alternative responses to these details – and, by extension, the images and landscapes of which they are a part – I make connections across chronologies and geographies, from Foucault to early Christian texts, and from the deserts of Egypt to the cities of late medieval Italy.[50] Though I consider written sources, I argue for the primary significance of the visual. Attending to the suggestiveness of these pairings of carrying monks raises questions about the proximity of the ascetic and the erotic, and invites consideration of the meanings they might bear, then and now.

The Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus, Vat.Gr.395

The earliest instance of the carrying motif known to me is in an eleventh-century illuminated manuscript of the Heavenly Ladder now at the Vatican Library (Fig. 2). The motif appears in a miniature at the start of the fifth chapter, or rung of the ladder, “On Penitence,” which deals with the extreme forms of adversity and self-inflicted suffering sought by the penitent. A tight-knit group of monks, all bearded and of advanced age, approach a seated figure. He is identifiable by his speaking gesture as the author and hegumenos (abbot), John Climacus, and is positioned to the left of the rectangular illuminated field. Separated from the main group and outside the vivid red frame of the illumination, two more figures hurry towards the gathering. One monk carries another on his back, holding tightly to his wrists to prevent him falling. The limbs of the carried monk hang limply; his left leg, visible beneath torn robes, seems damaged, scored violently with orange and yellow brushstrokes indicative of an open wound. The same colors, more roughly painted, emerge from the injured monk’s mouth, perhaps an indication of his crying out in pain. The two figures are brought together in close physical proximity by the suffering of the carried monk; their bodies lean urgently towards the others. Unanchored on the plain vellum of the page and furthest from the authoritative figure of the author-hegumenos, they occupy an indeterminate wilderness beyond the safety of the monastic enclosure.

The suffering of the carried monk and the urgency with which the pair approach the main group are clearly evident in the image. Their belonging is indicated by their long beards and habits, which mirror those of other monks. Yet the gesture of carrying also marks them as distinct. The carrying of one by the other is necessitated by physical incapacity and by an obedience to the words of the author-hegumenos at the start of the chapter:

Come, gather round, listen here and I will speak to all of you who have angered the Lord. Crowd around me and see what he has revealed to my soul for your edification.[51]

In the text that follows, Climacus instructs the monks about the self-inflicted suffering of penitence experienced in a place known as “the Prison.” He describes the visceral bodily consequences of sleep deprivation, self- injury, and exposure experienced in this purgatorial “place of pure grief.”[52] Climacus describes how the penitent must willingly endure suffering to draw down the mercy of God. He narrates the story of a zealous brother who is tempted by the devil to avoid the necessary pain of penance, and who anxiously seeks human help for a festering wound. Realizing his lack of faith, he throws himself at the feet of the hegumenos and asks to be sent to the Prison, where after a week of willing abjection, he is freed by death and granted burial among the fathers.[53] The marginal image of the carrying, wounded monk which precedes this narrative may represent the zealous brother and his subsequent, transformational penitence. While there is no indication in the text that the injured monk was carried, the image serves to illustrate the severity of the open wound and dramatizes the communal, bodily nature of his penitential gesture.

The story of the injured monk’s recognition of his sin, followed by his willing self-abnegation in the Prison, may seem to indicate an excessive contempt of the body. Yet the chapter does not end there; Climacus uses this narrative to indicate the importance of recognizing and redirecting the physical impulses through the act of penance. He draws an analogy between the zealous monk and “the gospel harlot,” whose dramatic self-revelation at the feet of Christ allows her to be completely transformed.[54] Mary Magdalene demonstrates how the successful redirection of a bodily impulse such as sexual love can be used as an impetus towards the love of God:

I have watched impure souls mad for physical love but turning what they know of such love into a reason for penance and transferring that same capacity for love to the Lord.[55]

Climacus uses the same word, eros, to refer both to carnal love and the love of God. The physicality of erotic love is neither rejected nor refused – it is a motivation for penance and a means of approaching God. Climacus draws a direct parallel between “the gospel harlot” and the wounded penitent, who each make the same dramatic gesture of disclosure, Mary at the feet of Christ and the monk at the feet of his superior. In this public, performative gesture, the penitent surpasses their individual, bodily desires (for love, or for comfort) and enters an ecstatic state beyond the self that precedes and enables salvation. The redirection of desires, the “turning” Climacus describes, is a transgressive turn beyond the limitations of the individual self. Rather than being refused, the desiring body is regarded both as the site or origin of sin and impurity, and, crucially, as the means of redemption.

The carrying motif on fol. 41r places the desiring (male) body in intimate proximity with another. The carrying gesture describes both the intensity of the suffering that accompanies ascesis, and the kinds of embodied relationships that emerge from it. It seems to concern love as much as it concerns pain. It is dramatic and unexpected, emphasizing the relationship that enables the act of penitence, rather than the act itself. This image reflects the kind of friendship Foucault describes, which is transgressive, troubling, with the capacity to sidestep established ways of being, and that often emerges in conditions of extremis:

Institutional codes can’t validate these relations with multiple intensities, variable colors, imperceptible movements and changing forms. These relations short-circuit it and introduce love where there’s supposed to be only law, rule or habit.[56]

In the chapter “On Penitence,” Climacus draws a direct connection between the act of penitence motivated by suffering and the act of penitence motivated by love, “eros.” The image which accompanies this chapter similarly brings into uncomfortable proximity the suffering of the injured monk and the gesture of love with which he is carried to the superior. It vividly demonstrates the intense emotional ties of queer ascesis that are central to the transformations of penitence.

Throughout the Heavenly Ladder, and particularly in the chapter on penitence, John Climacus describes the desirable pain undergone in ascesis. The image of the carried monk helps to articulate the suffering that is beyond words; as Elaine Scarry has noted, “pain has no voice.”[57] His inability to walk seems to be caused by a serious injury, possibly self-inflicted. In being carried to the gathering of monks around the hegumenos, his suffering is exposed; through this exposure he might be transformed. The public, performative nature of the event is common to descriptions of extreme, self-injurious ascesis in the literature.[58] Seen by others, this dramatic intensification of physicality holds a kind of compulsive fascination. Pain might be desired, inflicted, or willingly undergone by a subject, to achieve a hoped-for effect, “transporting the body in the intensity of its pain to the divine.”[59] It might also provoke desire in another, to undergo the same discordant “unpleasure,” or to gratify the senses, to titillate and horrify.[60] Describing his experience of witnessing the penitents of the Prison, Climacus writes:

Some wished for blindness so that they might be a pitiful spectacle, others sought paralysis so that they might not have to suffer later. And I, my friends, was so pleased by their grief that I was carried away, enraptured, unable to contain myself.[61]

Such is the extent of the suffering that the witness also experiences a kind of self-surpassing transport, echoing Bataille’s formulation of pain as both “ecstatic and intolerable.”[62] He shares something of the shattering effects of pain, in which time breaks apart and the penitent glimpses his future resurrection. The Penitence miniature perpetuates the witnessing of penitential suffering. It reiterates the connection between pain, sacrifice and exaltation and points towards the inaugurated eschatology of ascesis.[63]

The relationships of monastic community, dramatically intensified by the sufferings of penitence, were also a source of same-gender carnal desires. Climacus acknowledges the erotic potential of relationships within the monastery and repeatedly describes chastity as a “flame” which must burn with like power to the fires of lust.[64] In the chapter “On Discernment,” he describes two monks who develop an excessive fondness for one another, praising the discernment of an elder of the monastery who sows discord between them and brings their “unhealthy affection” to an end.[65] In early byzantine monastic typika, intimacy between monks was sometimes tightly regulated and forms of touch seen to be especially provocative, such as sitting together with another man astride a donkey, were forbidden.[66] Cyril of Scythopolis describes how the arrival of young, beardless, “feminine” novices might cause problems among established members of the monastery, “because of the conflict with the Enemy.”[67] Yet despite these evident anxieties about same-gender and pederastic desire, binding relationships between men in Byzantium were formalized through a Church rite originating in the seventh century, known as adelphopoiesis, or “brother-making.” These deep ties, similar to those of kinship, may well have concretized homoerotic intimacies.[68] In a monastic context, it recognized the joint purpose of two monks, particularly where they lived separately from the coenobium, and formalized shared living arrangements. The brothers’ spiritual companionship, intended to persist after death, replaced the ties of blood that had been renounced.[69] From both secular and religious contexts, the evidence is often deeply ambiguous, and homoerotic desire might be both suggestively present and firmly denied.[70]

The seventh-century Life of Symeon the Fool by Leontios of Neapolis includes a description of a religious rite that seems to be an early form of adelphopoesis.[71] When Symeon and his companion John are tonsured as monks together, they undergo a ceremony involving prayers and admonitions, after which they are blessed by the Abba Nikon as though joined in one body.[72] When the two eventually part company, after living together in the Judean desert for twenty-nine years, John laments, “…we agreed not to be separated from each other. Remember the fearful hour when we were clothed in the holy habit, and we two were as one soul, so that all were astonished at our love.”[73] Their union is described in terms that clearly echo the description of marriage in Genesis 2:24, and the (temporary) severance of their bond is both highly emotive and physically expressed.[74] Their close and affective relationship defies circumscription; it is a spiritual bond, affirmed at the start of the two men’s journey, that also invokes the desires of the body. The ambiguity appears intentional, suggesting the ascetics’ mutual encounter with temptation and the strength of a shared love that transcends death. The monastic partnerships described in the literature often appear contradictory, emerging in a monastic context that prohibited certain forms of relationship while accepting the frequent cohabitation of spiritual brothers.

The implicit eroticism of monastic friendship was often witnessed by, and functioned in relation to, others in the community. In the early collection of aphorisms known as the Apopthegmata Patrum, handed down from the Desert Fathers orally and recorded in the fourth century, the following narrative shows how close friendships might provoke or reveal desire in an observer:

A brother was attacked by a demon and went to a certain old man, saying: “those two brothers are with one another.” And the old man learned that he was mocked by a demon, and he sent to summon them. And when it was evening, he placed a little mat for the two brothers, and covered them with a single spread, saying: “The children of God are holy.” And he said to his disciple: “Shut up this brother in the cell outside, for he has the passion in himself.”[75]

Here, the bond between the two men is affirmed, and the nature of their closeness unquestioned. Their union, which is both spiritual and physical, is blessed by the gesture of covering them with a single blanket. Only in its mediation through the desiring gaze does the relationship become problematic. The “passion” of the onlooker seeks to disrupt the pleasures of the two brothers, but serves only to expose his own desires. The monks lie on the mat together in a demonstrative intimacy that encompasses, even if it does not consummate, queer desire. Their relationship takes on meaning in performance, much like the penitential suffering of ascesis. In the carrying motif, the viewer is witness to both suffering and suggestive intimacy, and to the desires and difficulties they contain.

Climacus, alongside other authors, invoked human love and bodily pleasures to express the ultimately desirable, spiritual delight of union with God.[76] In the eleventh century, at around the time this illumination was made, the monk and poet known as Symeon the New Theologian (d.1022), described an excessive and embodied love of God in definitively erotic terms. In his hymns, he frequently positions the male-gendered faithful as both lover and beloved (erastes/eromenos), actively seeking and gratefully receiving the “tender kisses” of divine love.[77] Derek Krueger has analyzed the deep (homo-)eroticism of Symeon’s writings, which explore the intensely physical desire animating a longing for God. He repeatedly invokes the counterpleasureable coexistence of passion and chastity, which Krueger argues is not reducible to metaphor. Symeon frames divine love as an unconsummated desire, “a devotion to Christ that is both excessive and queer.”[78] Climacus, too, employs the erotic language of the Song of Songs to express the consuming, “ravishing” love of Christ, enacted from within the bounds of monastic celibacy.[79] He saw the love between brothers as a necessary step on the Ladder, an aspect of love for God; “He who loves the Lord has first loved his brother, for the latter is proof of the former.”[80] Love is the final rung on the Ladder, the precursor to union with God. It is animated with hope and infinite beauty, described in terms which echo those used to describe the burning fires of lust; “It is an abyss of illumination, a fountain of fire, bubbling up to enflame the thirsty soul.”[81] It is in the queerly chaste love between brothers, and in the paradoxical heat of desire, that God might be approached.

The “carrying motif” at the start of the chapter On Penitence in Vat Gr 295 is located in the margins of the main illumination, beyond the boundaries of the monastic enclosure. It is an image of physical suffering and penitence, likely invoking the story of the injured monk narrated by the author later in the chapter. The emotional tenor of the pair, combining the violent pain of the carried monk with the tender embrace of his companion, is both excessive and arresting. The “carrying motif” speaks to the love between brothers and the limitations of the physical body in ascesis. It also invokes the carnality of the flesh and the ever-present “counterpleasures” of desire—for God, and for another—that are never fully consummated. Climacus regards the body, with all its limitations, as the source of radical transformational potential. In ascetic practice, desire is invoked in order that it might be overcome; mutual yearning leads, eventually, to a dissolution of boundaries between self and other that anticipates, but cannot reach, eventual union with God. Foucault later acknowledged this paradoxical impossibility of self-transformation in ascesis, which involves the fracture of the self and invention of new ways of relating to the other, “the work that one performs on oneself in order to transform oneself … which, happily, one never attains.”[82] He saw ascesis at the heart of a radical, utopian manner of being, a shared way of life that defies circumscription and escapes disciplinary control. The striking image of the carrying monks similarly resists confinement, pointing towards the troubling, affective intensities that Foucault locates in male friendship and to the utopian potential of queer community “at the margins.”[83]

Fig. 3. Florentine, Scenes from the Lives of the Desert Fathers (the Smaller Lindsay Panel), ca. 1480-1500, private collection, on long-term loan to the National Galleries of Scotland. (Photo by permission of the National Galleries of Scotland).

Fig. 4. A monk carried to the funeral, detail of Fig. 3.

Fig. 5. Emanuele Tzanfournari (signed), first half of seventeenth century. The funeral of St Ephraim. Pinacoteca, Vatican City (photo: Wikimedia Commons, under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

Fig. 6. A monk carried to the funeral, detail of Fig. 5.

The image of the carrying motif found in Vat gr 395 recurs, little altered, in much later eremitic landscapes such as the Smaller Lindsay Panel, made in Tuscany ca.1500 (private collection, Figs. 3 & 4) and the The funeral of St Ephraim by Emanuele Tzanfournari, ca.1700 (now in the Vatican Pinacoteca, Figs. 5 & 6). It evidently becomes an assimilated aspect of the iconography, closely associated with the funeral of a sainted hermit, and appears alongside other apparently incidental details, such as the tender interactions between hermits and tamed wild beasts. In the smaller Lindsay Panel, the carrying motif appears among a small group of monks who travel down a steep mountain path towards a funeral, an apparently minor detail of a broad, horizontal landscape with multiple concurrent narratives. A bearded monk clings tightly with his knees to his capable, upright younger companion, whose head is almost entirely obscured by the older man’s body. In the Tzanfournari panel, the carrying motif is a larger and more conspicuous aspect of a centrally-focused composition. The elderly monk crouches awkwardly on his companion’s back, causing the carrying figure to stoop under his weight and clutch onto his wrists to prevent him from falling. Here, the extreme difficulty of carrying a fully-grown, incapacitated man is more lucidly described. The two men’s bodies are carefully delineated and pressed tightly together as they progress unsteadily towards the funeral. In both images, the carrying motif appears alongside vignettes of other elderly monks carried in sedan chairs, pulled in wheelchairs, or shuffling on hand crutches, indicating the determination of all the monks living in the desert to pay their respects, no matter the hardship of the journey. The carrying motif seems curiously excessive in this context; it serves no clearly identifiable narrative purpose. Yet, more than the other vignettes of travelling monks, it succinctly describes the embodiment of the hermits’ friendships and the communal nature of their endeavor. It brings to mind the longstanding companionships formalized by adelphopoesis and the performative context of penitence. It openly acknowledges the instability and uncertainty of these relationships, at times visually conflating the two figures or underlining the precarity of their interdependence. In none of the examples discussed here are the carried monks identified, even where other figures in the image are identifiable by inscription or by established iconography. These anonymous pairs of monks, which repeat the motif found in the Heavenly Ladder (and perhaps elsewhere), are arresting indications of the queerly excessive intimacies that are inseparable from ascetic endeavor.

The Edinburgh Tabernacle

In the Edinburgh Tabernacle, painted in Tuscany ca.1295 and now at the National Galleries of Scotland in Edinburgh, the carrying motif appears twice (Figs. 7 & 8). As in the two later panels described above, the motif shows monks travelling together towards the funeral of a sainted hermit, and appears alongside vignettes of other elderly and incapacitated hermits. Though the current gallery label titles the central panel of the tabernacle The Death of St Ephraim and Scenes from the Lives of the Hermits, it is not possible to firmly identify the dead saint or the monks who travel to his funeral.[84] The narrative is dense and diffuse, with no clear visual anchor. As the first surviving Italian example of this iconography, it is likely to have been derived, in part, from an illuminated byzantine manuscript comparable to Vat Gr 395. Additional details, such as the elderly monk who reaches out to clasp a hand offered to help him, and the two monks who carry a sedan chair between them, are very close to interactions shown in the Penitence miniature on fol. 41r. Other details specific to the Orthodox monastic tradition, such as the stylite saint and the monk striking a semantron, similarly point to a byzantine origin, but the entire composition has been developed and adapted for a Latin audience. It represents an idealized form of the eremitic life, tied to the origins of Christian monasticism in the third and fourth centuries, but also, potentially, as it was perceived to be practiced in an Orthodox monastic context in the late thirteenth century. This way of life is presented in direct parallel to the sacrificial life, death and resurrection of Christ shown in the wings and pediment of the tabernacle.

Fig. 7. A monk carried to the funeral, detail of Fig. 1.

The first carrying pair appears at the far left-hand edge of the panel, about halfway up the mountain (Fig. 7). They are contained within a mass of bodies, a close community group that emerges from a chapel-like structure to travel to the funeral below. The standing monk is much larger than the figure he carries, whose wrists he clutches tightly at either side of his face. The carried monk is hunched high on his companion’s shoulders, his legs tucked beneath him and a single foot visible beneath his white, hooded robe. The faces of the two figures are pressed closely and tenderly together, their eyes fixed on the same spot in the middle distance. The compact posture of the carried monk on his companion’s back makes the figures difficult to separate, so that they appear conjoined, almost as one body.

Fig. 8. A sainted monk carried to the funeral, detail of Fig. 1.

The second pair appears at the lowest edge of the central scene, adjacent to the funeral of the sainted hermit (Fig. 8). The carrying monk is more evidently bowed under his companion’s weight than in the pair described above. He clasps the smaller figure’s feet to his chest as they seem to advance with difficulty towards the funeral. The carried monk, who is conspicuously haloed, rests his chin gently on his companion’s head. Both the two monks’ eyes are fixed on the bier of the dead saint, the event which motivates the carrying of one by the other, emphasizing the shared nature of their grief. While the monks travelling towards the funeral are drawn by the gravitational pull of death and grief, others closer to the summit of the mountain look up in wonder as they witness the ascent of the dead saint’s soul to heaven. The community is drawn together by the loss of a venerated saint and animated by the promise of future resurrection.

Fig. 9. Tuscan, Christopher of Lycia Carrying the Christ Child, wing of a triptych, panel, Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA.

The carrying motif in the Edinburgh Tabernacle may have prompted associations with images of Christopher of Lycia carrying the Christ child (Fig. 9). In the Golden Legend, Voragine describes how Christopher is prompted to this unusual form of physical ascesis by a hermit.[85] As he carries the Christ child across the river, he experiences the immense weight of the world and its creator on his shoulders. In the tabernacle, the carrying hermits’ sacrificial gesture functions also as a form of ascesis; in the second instance, it is undertaken by an ageing monk with a long grey beard who is bent double under the weight of his companion. As in images of Christopher carrying Christ, the carrying monk clasps onto his companion’s foot, while the smaller, carried monk holds on to the other’s head. The analogy with Christopher puts the carried monk in place of the supernaturally heavy Christ Child – a connection that is supported by the adjacent scenes of Christ’s Passion. Yet the carrying pairs of monks are difficult to visually disentangle, and they lack a clear narrative source. Although the diminutive size of the carried figures is somewhat infantilizing, the age of both hermits is clearly evident. The carrying gesture, in which one man rides on the back of another, is provocatively erotic; the carrying of an adult is a different proposition to the carrying of a child. While on one level the iconographic parallel to Christopher underlines the hermits’ likeness to Christ, on another, it highlights the unexpectedly queer, intimate care of one by the other in the environment of the wilderness.

The desert landscape depicted in the tabernacle is precipitously steep and rocky. The mountain is represented by tiers of jagged rocks, culminating in two pointed summits. The hermits travel to the funeral with difficulty, along steep, narrow paths. The scale of the mountain is suggested by the multiple layers of strata, and among the rocks, hermits and animals shelter in caves and contours. While the landscape is wild and remote, it is not barren. Abundant plants and flowing water decorate and animate the mountain, making it into a kind of flourishing paradise similar to Jerome’s description of the place where Antony lived in the desert:

…There is a high and rocky mountain extending for about a mile, with gushing springs amongst its spurs, the waters of which are partly absorbed by the sand, partly flow towards the plain and gradually form a stream shaded on either side by countless palms which lend much pleasantness and charm to the place.[86]

The abundance and provision of nature reflects the grace of God and the virtue of the saint. It also indicates the sensory beauty and pleasure that might be found even in a steep and inaccessible wilderness. Virginia Burrus has described the beauty of the far-reaching landscape as an aspect of the ascetic’s infinitely dispersed desire for God.[87] It often appears unexpectedly, in the deepest desert, beyond miles of harsh or barren land, and is always emphatically distant from civilization and the secular world. In the image, as in the ascetic literature, the hermits’ relationships are established in a remote place, outside of and beyond dominant social structures. They are alternative, self-sustaining communities that rely on reciprocal support, even where the monks, like the earliest desert fathers, live alone. In the tabernacle, the summit of the mountain reaches towards a soul carried to heaven, while its base shelters a funeral. The hermits travel precipitously downwards between the two, among demons, wild beasts, and angels, towards the inevitability of their own deaths and the hope of their future resurrection. The monks carried because of bodily infirmity, advanced age or emaciation are perhaps closer to death than the others. Yet they are also a source of sustenance for one another, like the water that flows from the rocks in the desert.

The early desert saints and their followers removed themselves to the desert to enact a dramatic, renunciative “death to the world.”[88] Their extreme, heroic acts of self-denial at the limits of human capacity epitomized an effort towards transcendence that was primarily solitary and dissociative, “a sort of humanity different from that of ordinary mortals and half-way to the other world.”[89] Yet their endeavors acquired meaning only in relation to others. The Life of Paul of Thebes describes how Antony discovers Paul’s superior ascetic virtue and determines to go farther into the desert to find him. After an arduous journey through the wilderness, the men eventually meet and embrace one another, in an arresting moment of intimacy that relieves their longstanding solitude.[90] The relationship that follows is brief but intense. Paul is close to death, and tells the distraught Antony that he has been sent by God to bury his body. In a gesture that echoes that of a lover, Antony declares he would rather die than be parted from his beloved, begging Paul to “take him as my companion on that journey.”[91] Jerome tells us that as he travels a second time to Paul’s cave, Antony “longed for Paul, desiring to see him and to contemplate him with his eyes and with his whole heart.”[92] The desire is both physical and all-consuming, expressed in kisses and embraces and, ultimately, in the burial of Paul’s body. It is thrown into relief by the remote and unyielding landscape of the utmost desert, through which Antony has travelled, and reflects the excesses of God’s love. The ascetic literature and authoritative lives of the first hermits demonstrates how flourishing human love is enfolded within the eremitic life.[93] In the outside-ness of the desert, ascesis permits the formation of particularly precarious and intense relationships, epitomized by the paradigmatic friendship of Paul and Antony, that embrace the desires of the body and simultaneously refuse their satisfaction. This mutually-witnessed “death to the world,” epitomized by the turning of the desiring flesh towards God, permits a “taste of the immortality to come.”[94]

Fig. 10. The Meeting of Antony and Paul, detail, 1180-1199, fresco, portico of Basilica di Sant’Angelo in Formis, Campania, Italy. Public Image – The Index of Medieval Art, Princeton University, system no. 180309.

Late-medieval images of the Desert Fathers depict them with long hair and beards, indicating their age and authority born of countless years in the wilderness (Fig. 10). The long, grey beards of the hermits in the Edinburgh Tabernacle are closely comparable, though only some of the hermits are sainted and none are clearly identifiable. Their conspicuous beards also serve to highlight their embodied maleness.[95] Like the impassioned friendship of Paul and Antony, the friendships represented in the Edinburgh Tabernacle are between men of similar age and status. Yet the close-pressed faces of the first carrying pair (Fig. 7) describes a strikingly maternal tenderness that echoes contemporary images of the Virgin and Child eleousa (Fig. 11). The same cheek-to-cheek gesture is also found in scenes of devoted love and grief, most often the Virgin and the dead Christ.[96] When it appears between physically entangled male monks, it invokes a gender-crossing intimacy that counters hegemonic constructs of ascetic masculinity as heroism and strength. It suggests the childlike vulnerability imposed by prolonged, incapacitating ascesis and the powerful bonds of spiritual brothers described as sharing one body. It also points to the indeterminate, “angelic” nature of the ascetic body described by Climacus: “…the awful and yet angelic sight of men grey-haired, venerable, preeminent in holiness, still going about like obedient children and taking the greatest delight in their holiness.”[97] These aged, humble, childlike bearded men cling to their brethren like the Child who clings to his Mother.

Fig. 11. Maestro del Trittico di Perugia, Trittico di Perugia (Trittico Marzolini), Virgin and Child eleousa with scenes from the Life and Passion of Christ (detail), 1280-1290, tempura on panel, (Photo credit: Haltadefinizione ®), Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia (photo: © Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria, Perugia).

In the thirteenth century, not long before the Edinburgh Tabernacle was made, Francis of Assisi likened the relationships established in the eremo to those between mother and child. In his short Rule for Hermitages (ca. 1217-1221), he suggested that friars take it in turns to act as protective “mothers” and contemplative “sons.”[98] Francis, a deeply ascetic man, saw the necessity for alternative practical, emotional and spiritual bonds of support among friars who withdrew from society to live in the wilderness. Such bonds acknowledge the value of typically “feminine” qualities such as tenderness and nurture alongside those associated with masculinity – particularly the practice of ascesis and the transformation of the body.[99] Francis suggests that these specific, gendered roles might be performed by any friar in the eremo at certain times; the rigors of the environment necessitate a particularly intimate and fluid kind of interdependence. He also associates the eremitic way of life with the childlike obedience admired by Climacus, even among those who are older or more experienced. For Francis, as for others living and writing in the ascetic tradition before him, the eremitic life instantiates ways of being that transcend fixed identities associated with gender, age or status. In the visual sources, the hermits’ beards indicate their maleness, and their monastic habits imply chastity. Yet their interactions in the carrying motif – and, potentially, elsewhere – cannot be constrained by limited, binary understandings of gender or of sexuality. They indicate the potent ambiguity of spiritual kinship as a form of queer relationality that surpasses sex alone.[100]

The eremitic way of life periodically embraced by Francis became an important paradigm for the so-called Spiritual Franciscans towards the end of the thirteenth century.[101] While the institutional Order prioritized the establishment of convents and preaching to the laity in towns and cities, the Spirituals sought to re-animate the rigorous renunciation of Francis and prioritize a contemplative life in the wilderness. They objected to the perceived corruption of Francis’ Rule and Testament by members of the Church hierarchy and advocated for a return to the highly ascetic origins of the early Order. In doing so, they echoed the repeated invocation of monastic origins in the wilderness, common to reforming religious orders in Europe since at least the tenth century.[102] While eremitic practice was widely admired, inseparable from the highest ideals of the Christian religious life, it was also seen to be risky, prone to irregularity and heterodoxy. Eremitic congregations, which proliferated in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, presented a challenge to established forms of power and all too easily escaped institutional control.[103] Amidst the growing crisis of the Spiritual controversy, the eremitic way of life also became associated with flight from persecution and religious dissent, as the most radical of the Spiritual friars were exiled or sought refuge in hermitages. Some of the Spiritual Franciscans found confirmation of their beliefs in the controversial apocalyptic theology of Joachim of Fiore (d.1202).[104] His Exposition on the Apocalypse (c.1184) prophesied the imminent dawn of the ultimate, third “age” of humanity, heralded by the arrival of a contemplative order of “viri spiritualis.”[105] The period of transition – from the present age of corruption and tyranny to a future age of peace and concord – would be marked by a time of conflict and persecution. It was not difficult for the Spiritual Franciscans to align themselves with the prophesied true followers of Christ, and to see their struggle in opposition to a powerful and corrupt Church hierarchy which had effectively undermined the purity of Francis’ Rule.

The image at the center of the Edinburgh Tabernacle reflects the idealized, potentially controversial nature of an eremitic existence at the end of the thirteenth century. It imagines a way of life likely radically different from the context in which it was first seen, associated with monastic origins, apocalyptic expectation and religious dissent. As discussed above, it is iconographically linked to illuminated manuscripts of the Heavenly Ladder, a text first translated into Latin by the dissident Spiritual Franciscan Angelo Clareno prior to 1294.[106] Clareno believed that the Orthodox tradition represented a pure form of Christian spirituality, close to that of Francis. He hoped his translation of the Heavenly Ladder and other Greek texts would contribute to the reform of the Franciscan Order and renewal of the Latin Church.[107] Clareno and his companions had been repeatedly banished to hermitages in Italy and further afield, in Cilicia and Greece, for defying their superiors in the Order. Yet Clareno actively sought a life of poverty “in the desert,” regarding this as the only possible way to follow the example of St Francis and to overcome the present tribulations of the Order.[108] While the patronage of the Edinburgh Tabernacle remains uncertain, its likely origins in illuminated manuscripts of the Ladder suggest a potential connection to the Spiritual Franciscans and to the short-lived papacy of the hermit-pope Celestine V in 1294. At the end of the thirteenth century, such an image may well have carried associations of an opposition or challenge to established forms of power and institutional control – a “marginal positionality” and implicit critique of dominant religious discourses.[109]

Integral to this image of eremitic life, the carrying hermits dramatize the alternative forms of intimacy that emerge from a distant past and approach a proximate, utopian future. They enact the labors of a queer ascesis understood, per Foucault, as an ongoing, embodied process of self-transformation, surpassing the limitations of a fixed identity and oriented instead towards discursive reversibility and collective self-invention.[110] José Esteban Muñoz describes queerness as a “mode of desiring” that allows us to glimpse a hoped-for, not yet realized way of being in the world.[111] The communities of hermits, particularly the carrying pairs I have chosen to focus on in this paper, point towards the “open, indeterminate potentiality” of an eremitic utopian.[112] They invoke hope and tenderness as well as fear and violence, childlike humility and ascetic strength. They are queerly, chastely erotic. Together, they encompass the multiple, shifting, counterpleasurable desires of shared ascesis. The community they help to constitute functions as an imagined and idealized alternative social order, close to the queer subcultures described by Halberstam as an opposition to hegemonic (gendered, sexualized) constructions of time and space.[113] This is an alternative temporality of advanced age and infirmity, impending death and imminent resurrection. It involves a striving towards the future from within the present confines of a body “already risen to immortality before the general resurrection.”[114] This constant movement towards the eschatological future is enacted by the community in deserted places, outside of, and in tension with, the structures of institutional religion. The carrying motif, and the image of which it is a part, distills an idealized past and projects an imagined, utopian future.[115]

Conclusion

The carrying motif at the heart of this discussion derives from illustrations of monastic community and penitential ascesis in manuscripts of the Heavenly Ladder. In the Edinburgh Tabernacle, it functions as an integral aspect of eremitic existence closely associated with the commemoration of a dead saint, significant in its repetition here and in other panel paintings, despite the seeming absence of a clear narrative or literary source. This is a relationship that is framed by, and constituted in, the landscape of the desert, describing the flourishing love between men amidst the suffering associated with an extreme and barren environment. In both main case studies, it dramatizes the strongly communal aspect of the eremitic life and the centrality of witnessing to ascetic endeavor, permitting the suffering of the carried monk and the closeness of the pair to be seen – in community and by the audience. It also highlights the monastic journey, the perpetual movement towards God which the monk must undertake, helped by his companions if necessary. This movement towards the future is clear in the Edinburgh Tabernacle, where monks witness the resurrection of the dead saint’s soul and the entire scene invokes the utopian potential of the eremitic way of life. In the present moment of its making at the end of the thirteenth century, amidst religious controversy, persecution and dissent, this painting may have invoked the oppositional potential of an eremitic life in relation to dominant or institutionalized forms of power.

The images considered here represent forms of specifically eremitic relationality that correspond with the self-surpassing, “queer” friendships discussed by Foucault. In Friendship as a Way of Life, Foucault talks about new forms of relationality that defy circumscription and resist hegemonic forms of power in the guise of sexuality. He sees the radical potential in friendships between men as a way of being, a “matter of existence.”[116] Foucault wrote about the radical possibilities, not so much of sex, or the “liberation of desire,” as of resistance to hegemonic forms of power through new alliances, “unforeseen lines of force.”[117] He saw this resistance as a creative process, a self-determined, marginal positionality from which it becomes possible to critique dominant cultural discourses around power, truth, and desire. Halperin describes this way of being as “the transformative practice of queer politics,” a strategic possibility which cultivates the ability to “enter into our own futurity.”[118] This essay has argued that the eremitic way of life, as it is refracted in the visual sources, may be productively read as a parallel form of queer, resistant positionality in the premodern past. This resistant positionality emerges most clearly in the touching, unsettling forms of friendship so vividly imagined in the images of struggling, suffering, loving pairs of monks who carry one another through the wilderness.

References

| ↑1 | For a detailed discussion of this object, see Amelia Hope-Jones, “‘Poor Men and Brother Hermits’: The Spiritual Franciscans and a Late Thirteenth-Century Image of the Desert,” Gesta 64, no. 2 (2025) (forthcoming); Manuela De Giorgi, “La Dormizione dell’Eremita,” in Atlante delle Tebaidi, ed. Alessandra Malquori, Laura Fenelli, and Manuela De Giorgi (Florence: Centro Di, 2013), 196-7; Alessandra Malquori, Il giardino dell’anima: ascesi e propaganda nelle Tebaidi fiorentine del Quattrocento (Florence: Centro Di, 2012), 52-65, 192-97, 201-13. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | John Martin, The Illustration of the Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954) 59-60. |

| ↑3 | Michel Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” in Ethics: Essential works of Foucault 1954-1984, ed. Paul Rabinow (London: Penguin Books, 2000), 135-140. All quotations in the following paragraph are taken from this source, unless cited otherwise. |

| ↑4 | Some feminist and postcolonial theorists have criticized Foucault’s implicit and unacknowledged (male, colonial) subject-position. See, for example: Nancy Hartstock, The Feminist Standpoint Revisited, and Other Essays (Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 2019) and Anjali Arondekar, For the Record: On Sexuality and the Colonial Archive in India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009). |

| ↑5 | Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick supports and expands this argument in Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016), 4-5. |

| ↑6 | John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, trans. Colm Luibheid and Norman Russell (Paulist Press, 1982). I tend to use its alternative title, The Heavenly Ladder (Scala Celeste) in the text, for brevity. |

| ↑7 | For an overview of the Ladder in its monastic context, see Jonathan L. Zecher, “Introduction: Approaching the Ladder as a Text in Tradition,” in The Role of Death in the Ladder of Divine Ascent and the Greek Ascetic Tradition (Oxford Early Christian Studies, online edn, 2015), 1–28. |

| ↑8 | Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988), 240. |

| ↑9 | Kallistos Ware, “Introduction,” in The Ladder of Divine Ascent trans. Luibheid and Russell, 58-59. |

| ↑10 | Charles L. Stinger, Humanism and the Church Fathers: Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439) and Christian Antiquity in the Italian Renaissance (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1977), 127. |

| ↑11 | There is an extensive literature on the subject. See, for example: James Goehring, Ascetics, society, and the desert: studies in early Egyptian monasticism (Trinity Press International, 1999); William Harmless, Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism (Oxford University Press, 2004); David Brakke, Demons and the Making of the Monk: Spiritual Combat in Early Christianity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006); Claudia Rapp, “Desert, City, and Countryside in the Early Christian Imagination,” Church History and Religious Culture 86, no.4 (2006), 93-112. On the legacy in western monasticism, see: Jitse Dijkstra and Matilde van Dijk, eds., The Encroaching Desert (Leiden: Brill, 2006); Steven Vanderputten, Medieval Monasticisms: Forms and Experiences of the Monastic Life in the Latin West (Berlin: de Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2020). On the eastern context, see: Peter Hatlie, “Monasticism in the Byzantine Empire,” in The Oxford Handbook of Christian Monasticism, ed. Bernice M. Kaczynski (Oxford Handbooks online, 2020); Alice-Mary Talbot, Varieties of Monastic Experience in Byzantium, 800-1453 (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2019); J Thomas and A Constantinides Hero, eds. Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments, 4 vols. (Dumbarton Oaks, 2000). |

| ↑12 | Claudia Rapp, Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium: Monks, Laymen, and Christian Ritual (Oxford University Press, 2016), 91. |

| ↑13 | Benedict lived c.480-c.545. His Rule, alongside other primary sources, is translated in Owen Chadwick, ed. Western Asceticism: selected translations (London: SCM Press, 1958). |

| ↑14 | Brown, The Body and Society, 47; Karmen MacKendrick, Counterpleasures (New York: State University of New York Press, 1999), 69. |

| ↑15 | Roland Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender and Race in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020), 130. |

| ↑16 | Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), 8. |

| ↑17 | David Halperin, Saint Foucault: towards a gay hagiography (Oxford: University of Oxford Press), 57. |

| ↑18 | Judith Halberstam, In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (New York: New York University Press, 2005), 1. |

| ↑19 | Michel Foucault, “The Battle for Chastity,” in Ethics, ed. Rabinow, 179. |

| ↑20 | Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (New York: Routledge, 2nd ed. 2006), xxviii. |

| ↑21 | Following Nietzsche, Foucault favoured a genealogical approach to history, a refutation of dominant teleological or universalising narratives and thus a way to imagine alternative conditions in the future. See Michel Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice; Selected Essays and Interviews, transl. Sherry Simon, ed. Donald F. Bouchard (Cornell University Press, 2019). |

| ↑22 | Michel Foucault, “Sex, Power, and the Politics of Identity,” in Ethics, ed. Rabinow, 170-71. |

| ↑23 | Foucault, “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History,” 156. |

| ↑24 | Michel Foucault, in Fornet-Betancourt et al., “The ethic of care for the self as a practice of freedom: an interview with Michel Foucault on January 20, 1984,” Philosophy and Social Criticism 12, 2-3 (1987), 113. |

| ↑25 | Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” 137; Halperin, Saint Foucault, 77-78. |

| ↑26 | Foucault, “The Battle for Chastity,” in Ethics, ed. Rabinow, 139. |

| ↑27 | Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” 136. |

| ↑28 | Foucault, quoted in Halperin, Saint Foucault, 94. |

| ↑29 | Halperin discusses Foucault’s attitude to S/M, and other forms of transgressive sexuality, in Saint Foucault, 85-99. |

| ↑30 | Foucault argued against the tendency to associate ‘queer’ resistance only with radically non-normative social and sexual practices. This point is made in “Friendship as a Way of Life”; it is not the gay sex act that is potentially troubling, but the formation, through homosexuality, of new kinds of community, new relationships. Leo Bersani, “The Gay Daddy,” cited in Halperin, Saint Foucault, 97; Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” 137. |

| ↑31 | Halperin, Saint Foucault, 76-77. |

| ↑32 | MacKendrick, Counterpleasures, 12; Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” 309. |

| ↑33 | See, for example, Carolyn Dinshaw, Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Postmodern (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1999); David Hunter, “Celibacy was Queer,” in Queer Christianities: Lived Religion in Transgressive Forms, ed. Kathleen Talvacchia (New York University Press, 2014); Geoffrey Galt Harpham, “Ascetics, Aesthetics, and the Management of Desire,” in Religion and Cultural Studies, ed. Susan Mizruchi (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021); Christopher Vaccaro (ed.), Painful Pleasures; Sadomasochism in medieval cultures (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2022). |

| ↑34 | Robert Mills, Suspended Animation (London: Reaktion, 2005), 8. |

| ↑35 | MacKendrick, Counterpleasures; Virginia Burrus, The Sex Lives of Saints: An Erotics of Ancient Hagiography (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). |

| ↑36 | MacKendrick, Counterpleasures, 9. |

| ↑37 | Burrus, Sex Lives of Saints, 45. |

| ↑38 | Leo Bersani, “Is the Rectum a Grave?”, cited in Burrus, Sex Lives of Saints, 14. |

| ↑39 | John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981). For the traditional approach, see: Jean Leclerq, Monks and Love in Twelfth-Century France: Psycho-Historical Essays (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979); Stephen C. Jaeger, Ennobling Love: In Search of a Lost Sensibility (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999); Brian Patrick McGuire, Friendship and Community: The Monastic Experience, 350-1250 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010). See also: Corinne Saunders, “‘Greater love hath no man’: Friendship in Medieval English Romance,” in Traditions and innovations in the study of Middle English literature: the influence of Derek Brewer, edited by Charlotte Brewer and Barry Windeatt (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 128-143. |

| ↑40 | Derek Krueger, “Between Monks: Tales of Monastic Companionship in Early Byzantium,” Journal of the history of sexuality 20.1 (2011): 28–61; Mark Masterson, Between Byzantine Men: Desire, Homosociality, and Brotherhood in the Medieval Empire (Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2022); — “Impossible Translation: Antony and Paul the Simple in the Historium Monachorum,” in The Boswell Thesis: Essays on Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, ed. Mathew Kuefler (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 215-235; Robert Mills, Seeing Sodomy in the Middle Ages (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015); Mathew Kuefler, “Male Friendship and the Suspicion of Sodomy in Twelfth-Century France” in Gender and Difference in the Middle Ages, eds. Sharon A Farmer and Carol Braun Pasternack (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 145-181; Claudia Rapp, Brother-Making in Late Antiquity and Byzantium: Monks, Laymen, and Christian Ritual (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016); Dirk Krausmüller, “Byzantine Monastic Communities: Alternative Families?” in Approaches to the Byzantine Family, eds. Shaun Tougher and Leslie Brubaker (London: Routledge, 2016), 345-358. |

| ↑41 | Roland Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality; Sexuality, Gender and Race in the Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 130. |

| ↑42 | See Chapter 3, “Transgender Lives,” in Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality, which discusses the Life of the trans monk Marinos, among others. See also: Leah DeVun, The Shape of Sex; Nonbinary Gender from Genesis to the Renaissance, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2021); Greta LaFleur, Masha Raskolnikov, and Anna Klosowska, eds., Trans Historical: Gender Plurality before the Modern (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2021); Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt, eds., Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2021). |

| ↑43 | Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” 136. |

| ↑44 | This was noted by Foucault, “The Battle for Chastity,” in Ethics, ed. Rabinow, 188. See also: Brown, The Body and Society, 230; David Hunter, “Celibacy was Queer,” 21. See also: Christopher Roman, Queering Richard Rolle: Mystical Theology and the Hermit in Fourteenth-Century England (Cham: Springer International, 2017). |

| ↑45 | Mills, Seeing Sodomy, 21. |

| ↑46 | Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality, 15-16. |

| ↑47 | Betancourt and Harpham both separately recognize the importance of the visual, but this is not their starting point. Betancourt, Byzantine Intersectionality, 5; Harpham, “Ascetics, Aesthetics, and the Management of Desire,” 100-107. |

| ↑48 | See, for example: Denva Gallant, Demons and Spiritual Focus in Morgan MS M.626,” Gesta 60, no.1 (2021), 101-119; — Illuminating the Vitae Patrum: The Lives of Desert Saints in Fourteenth-Century Italy (The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024); Anne Leader, “The Church and Desert Fathers in Early Renaissance Florence: Further Thoughts on a ‘New’ Thebaid,” in New Studies on Old Masters: Essays in Renaissance Art in Honour of Colin Eisler, ed. Diane Wolfthal and John Garton, Essays and Studies 26 (Toronto: Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2010); Maria Corsi, Gli affreschi medievali in Santa Marta a Siena: studio iconografico (Siena: Cantagalli, 2005); Lina Bolzoni, The Web of Images: Vernacular Preaching from Its Origins to Saint Bernadino da Siena (Burlington: Ashgate, 2004); Alessandra Malquori, “La ‘Tebaide’ degli Uffizi. Tradizioni letterarie e figurative per l’interpretazione di un tema iconografico,” I Tatti Studies. Essays in the Renaissance 9 (2001), 119-137. All of this scholarship has added much to our understanding of the eremitic way of life and its expression in visual culture. |

| ↑49 | John Martin, “The Death of Ephraim in Byzantine and Early Italian Painting,” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 33 no. 4 (1951), 217-225; John Martin, The Illustration of the Heavenly Ladder of John Climacus (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954) 59-60; Malquori, Il Giardino dell’Anima, 52-65, 192-97, 201-13; Massimo Bernabò, “Rezension Von: Il Giardino dell’Anima: Ascesi e Propaganda nelle Tebaidi Fiorentine Del Quattrocento,” Rivista di Bizantinistica, no. 15 (2013), 199–201. |

| ↑50 | Following Valerie Traub, I intend for “queer to denaturalize sexual logics and expand the object of study through untoward combinations and juxtapositions” and am confident in the potential of the visual to contribute to historical understanding. I believe that through images, the past might speak to the present. Valerie Traub, “The new unhistoricism in queer studies,” PMLA, 128 (2013), 27. |

| ↑51 | Climacus, Ladder of Divine Ascent, 121. |

| ↑52 | Climacus, Ladder of Divine Ascent, 122. |

| ↑53 | Climacus, Ladder of Divine Ascent, 128. |

| ↑54 | Climacus, Ladder of Divine Ascent, 128; Luke 7:47. |

| ↑55 | Climacus, Ladder of Divine Ascent, 129. |

| ↑56 | Foucault, “Friendship as a Way of Life,” 136. |

| ↑57 | Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain, 3. |

| ↑58 | Peter Damian wrote De laude flagellorum (In Praise of Flagellation) ca.1070, defending its primacy as a form of public penitence and exerting a profound influence on its widespread practice in late-medieval Europe. Sarah Chaney, Psyche on the Skin: a history of self-harm (London: Reaktion, 2019), 37; William Burgwinkle, “Visible and Invisible Bodies and Subjects in Peter Damian,” in Troubled Vision: Gender, Sexuality, and Sight in Medieval Text and Image, ed. Emma Campbell and Robert Mills (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 47-62. |

| ↑59 | MacKendrick, Counterpleasures, 86. |

| ↑60 | Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Penguin, 2013), 34. |

| ↑61 | Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 128. |

| ↑62 | Georges Bataille, cited in Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others, 34-35. |

| ↑63 | Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 185–86; Ware, “Introduction”, 31-32. |

| ↑64 | Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 171; 288. |

| ↑65 | Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 250. |

| ↑66 | Pachomius, Pachomian Koinonia: The Lives, Rules, and Other Writings of Saint Pachomius and His Disciples, trans. Armand Veilleux, vol. 2 (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1981), 161-162. Climacus also mentions bestiality with donkeys in his discussion of Chastity, Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, 175. |

| ↑67 | Benedicta Ward, ed. The Sayings of the Desert Fathers: the alphabetical collection (London: Mowbray, 1981), 64 |

| ↑68 | The practice is alluded to in Boswell’s discussion of “gay marriage,” in Christianity, social tolerance, and homosexuality, 50. |