Rebekah Compton • College of Charleston

Recommended citation: Rebekah Compton, “Forest Ecology: The Silver Fir Trees of Camaldoli in Fra Filippo Lippi’s Uffizi and Berlin Adoration of the Child paintings,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/JUUW5642.

The whole earth is quiet and still, it is glad and hath rejoiced. The fir trees also have rejoiced over thee, and the cedars of Libanus, saying: Since thou hast slept, there hath none come up to cut us down. … All shall answer, and say to thee: Thou also art wounded as well as we, thou art become like unto us.[1]

Isaiah 14:7-8, 10

You could also be a fir tree, lofty in height, densely shady and luxuriantly green, striving to meditate on sublime truths, contemplate heavenly realities, and knock at the doors of the highest dwelling of divine majesty.[2]

Rudolf II, Book of Eremetical Rule, 1080

Fig. 1. Filippo Lippi, Adoration of the Child with Young St. John the Baptist and St. Romuald, c. 1463. Tempera and oil on wood. Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. Photo: Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo.

In c. 1463, Piero de’ Medici and Lucrezia Tornabuoni commissioned the building of a new cell at the Sacred Hermitage of Camaldoli. To adorn its oratory, the couple enlisted Fra Filippo Lippi to paint an Adoration of the Child (Fig. 1), placed on a wooden altar draped with an embroidered cloth bearing the Medici and Tornabuoni arms.[3] In the painting, a young Virgin Mary kneels in prayer before a radiant Christ Child nestled in green grass and spring flowers. A youthful St. John the Baptist traverses the mountainous terrain, toting a slender gold cross. In the lower right, the hermit St. Romuald grasps a whittled, tau-shaped crozier and touches his hand to his heart, as he gazes upon the Holy Savior, who looks directly at the viewer. God, abstracted into the agency of his hands, opens the heavens and releases the Holy Spirit in a burst of glittering light. The epiphany unfolds in a forest of fir trees, where flowing streams nourish lush grass; it is the landscape of the Sacred Hermitage of Camaldoli (Fig. 2). Here, Romuald of Ravenna was inspired by the Holy Spirit to establish the Church of the Holy Savior, around which an eremitical community rose — like fir trees — to heaven.

Fig. 2. Sacred Hermitage of Camaldoli. Photo: Luc Kordas / Alamy Stock Photo.

Fig. 3. Filippo Lippi, Adoration in the Forest, c. 1459. Tempera and oil on wood. Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Photo: Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo.

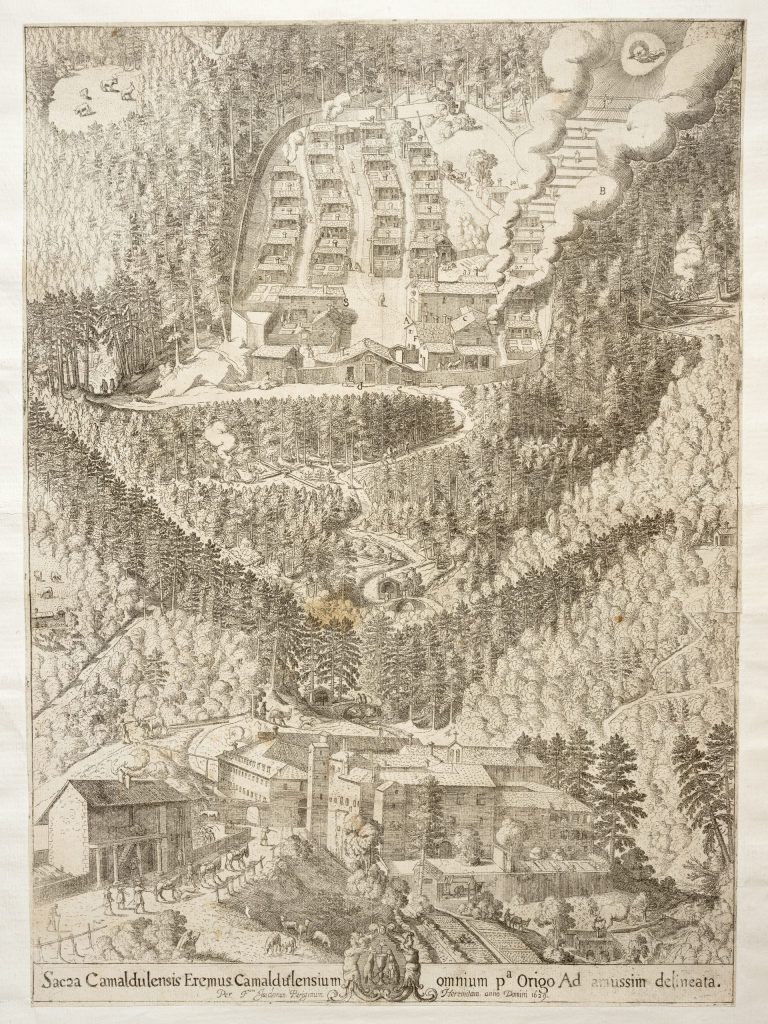

The landscape of Lippi’s Adoration of the Child for the Sacred Hermitage resonates with the imagery of his earlier Adoration in the Forest (Fig. 3), created for the altar of the Medici family’s private chapel. Likely commissioned by Piero de’ Medici and Lucrezia Tornabuoni, this painting situates the Madonna and Child, St. John the Baptist, and St. Romuald within a densely wooded forest interlaced with flowing streams. The topography, I argue, evokes the lower forest surrounding the Monastery of Fontebuono, located approximately three kilometers and over 300 meters in elevation below the Sacred Hermitage. A 1629 engraving of The Sacred Camaldolese Hermitage (Fig. 4) by Brother Isidore of Paris, a hermit, offers a bird’s eye view of Camaldoli.[4] The Monastery of Fontebuono derives its name from the abundance of freshwater springs in the area; it was originally founded by Romuald as an infirmary and guesthouse. The Medici family had provided financial support to the monastery since at least 1434, and Lucrezia Tornabuoni owned property nearby. She was a devotee of both St. John the Baptist and St. Romuald, a devotion expressed in Lippi’s Adoration in the Forest.[5]

Fig. 4. Brother Isidore of Paris, hermit, The Sacred Camaldolese Hermitage, the origin of all Camaldolese Fathers, 1629. Engraving. Private Collection. Photo: Isabella Case.

While art historians have noted the naturalistic and spiritual qualities of Lippi’s Adoration landscapes—and sometimes linked them to his Carmelite training—they have not adequately explored their ecological and silvicultural contexts.[6] This essay addresses that gap by applying an ecocritical lens to Lippi’s Adoration panels. A growing interdisciplinary field of study, ecocriticism analyzes literary and artistic representations of the natural world in relation to environmental concerns. Within early modern art history, recent studies—such as James Pilgrim’s work on Jacopo Bassano’s Flood of Colmeda and David Aberdeen’s discussion of the ecological resonance of tree stumps in Italian Renaissance art—have laid important groundwork for the field of ecocritical art history.[7] Building on these roots, this essay turns to the development of Camaldoli’s landscape in Renaissance paintings, paying particular attention to the measures employed by the Order to protect its vital resources. The essay investigates the iconographies of St. Romuald, the silver fir tree, and the Hermitage in paintings and drawings by Nardo di Cione, Don Giuliano Amidei, Fra Filippo Lippi, and Giorgio Vasari. Trained in Florentine techniques of perspective and botanical study, these artists invite viewers into Camaldoli’s lived—and protected—woodland world.

The forest of Camaldoli was a vital resource for Florence and a popular destination for Florentine visitors. It was also a site of natural thaumaturgy, where divine interventions shaped the landscape. Compelling readings of natural thaumaturgy have been offered by scholars, such as Alison Perchuk and Ellen Arnold, who focus on the environmental underpinnings of hagiographic accounts.[8] This essay builds on their work by examining natural thaumaturgy in relation to St. Romuald and the Appenine mountains. It also explores the enchanted ecology of Camaldoli through the lens of ecomateriality—an approach that considers how natural materials are extracted, handled, maintained, and imbued with meaning. As Gregory Bryda argues in The Trees of the Cross, wood carries both material and symbolic weight, particularly in devotional and monastic contexts.[9] The silver fir trees and rushing waters of Camaldoli were understood as shaping a sacred topography evocative of Isaiah 41:11–20, in which God transforms a desert wilderness into an evergreen forest teeming with water.[10] This essay delves into the ecology and economy of Camaldoli as well as the measures designed to conserve and cultivate its forest.

Regulations for protecting Camaldoli’s natural resources begin as early as 1189 and steadily continue into the eighteenth century. Measures focus on the fir tree stands and include prohibitions, prior authorizations, boundary enforcements, posted notices, and planting mandates. In 1404, the Florentine humanist Coluccio Salutati petitioned the General of the Camaldolese Order to preserve its “sacred wood,” both for the sanctity of the Hermitage and the enjoyment of its visitors.[11] During the second half of the fifteenth century, concern for the forest’s sustainability intensified after a hydro-powered sawmill was installed at the Monastery of Fontebuono and commercial logging began in earnest.[12] The Hermits of Camaldoli managed their alpine forest from the founding of the Sacred Hermitage in 1024 until the second suppression of monasteries by the Napoleonic regime in 1866. The land was officially transferred to the Forest Administration of the Region of Tuscany in 1974.[13] Key documents related to the millennial history of Camaldoli’s forest have been collected by Italian scholars, beginning with Don Giuseppe Cacciamani.[14] In 2012, Carlo Urbinati and Raoul Romano co-edited the Codice forestale Camaldolese (2012), which includes inventories, logging records, and land regulations with a focus on forest management after 1500. Exploring this woodland with an eye to the previous two centuries, this essay uncovers how art and architecture reflected, engaged with, and helped shape the understanding of Camaldoli’s sacred woodland.[15]

Natural Thaumaturgy: St. Romuald and the Forest of Camaldoli

Filippo Lippi’s Adoration of the Child (Fig. 1) for the Sacred Hermitage is among the earliest Florentine altarpieces to replace the solid gold ground standard to the genre with a vivid naturalistic landscape.[16] The painting adorned the oratory of the Medici-sponsored cell dedicated to St. John the Baptist, an homage likely related to the death in 1463 of Piero’s brother, Giovanni di Cosimo de’ Medici (1421-1463).[17] The landscape of Lippi’s Adoration echoes the silver fir trees and forest clearing of the Sacred Hermitage and recalls the earliest account of St. Romuald’s dream to found the Church of the Holy Savior. The painting includes the Holy Spirit and a natural ladder to Heaven, composed of steep terrain interspersed with grassy landings and fir trees that reach up to the sky. As the land rises, God descends, sending forth Jesus, the Holy Spirit, and two evergreen angels. The painting infuses the landscape, which it depicts and in which it is located, with divine revelation.

The first written account of Camaldoli’s origin is found in the Constitutions of Rudolf I (c. 1080). It states that “the Hermitage of Camaldoli was built by our Holy Father Romuald the hermit, through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit and at the request of the Most Reverend Theobald, Bishop of Arezzo, along with a church consecrated by the same bishop under the patronage of the Holy Savior.”[18] The site was granted between 1023 and 1026, and the church consecrated in 1027.[19] The Book of the Eremitical Rule, written in the twelfth century by Prior Rudolf II, includes a more popular account of Romuald’s founding of the Sacred Hermitage. According to Rudolf II, Romuald fell asleep “in a field in the Alps,” where he “dreamed like the prophet Jacob of a very high ladder reaching to heaven, on which were climbing a band dressed in shining white.”[20] The dream inspired Romuald to establish the Sacred Hermitage and to change the habit of his reformed group from Benedictine black to Camaldolese white.

Fig. 5. Nardo di Cione, The Dream of St. Romuald, right panel of the Trinity, St. Romuald and St. John the Evangelist, 1365. Tempera on wood. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. Photo: akg-images / De Agostini Picture Lib. / A. Dagli Orti.

Fig. 6. Nardo di Cione, Trinity, St. Romuald and St. John the Evangelist, 1365. Tempera on wood. Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. Photo: akg-images / De Agostini Picture Lib. / A. Dagli Orti.

An early representation of The Dream of St. Romuald (Fig. 5) is included as a predella scene in the Trinity altarpiece, by Nardo di Cione (1320-1366), dated 1365. Commissioned by Giovanni Ghiberti, this glittering triptych (Fig. 6) was installed in the chapel of St. Romuald, one of six chapels surrounding the chapter room of the Florentine Camaldolese Monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli.[21] In the painting, Romuald appears as a tough, hearty monk with a long wooly beard. He wears a white or undyed cocolla (monk’s habit) and holds a leather bound, embossed Psalter, the keystone of the Benedictine Divine Office and of Romuald’s ministry.[22] A Psalter believed to have belonged to Romuald, and glossed by him through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, was kept as a relic in the Church of the Holy Savior in Camaldoli.[23] In Cione’s panel, Romuald grasps a tau-shaped wooden staff, a deliberate deviation from the Roman church’s formal shepherd’s crook. The tau-shaped crozier was associated with Eastern traditions of Christianity, with abbots, and specifically with the first hermit and desert father, St. Anthony of Egypt.[24]

Peter Damian’s hagiographic account of Romuald, written 15 years after the hermit’s death, links Romuald to the desert fathers. His wilderness, however, is not the desert but the forest, where he is connected to the upright growth of trees and to the solitude of the woods, where miracles involving its dangers also occur.[25] Damian begins the Vita with an account of Romuald’s early life in Ravenna, writing that the adolescent’s “soul was drawn to solitude.”[26] When finding a lovely spot in the woods while hunting, Romuald was said to have proclaimed: “How pleasant to live like hermits in these forest recesses; how easily one could be quiet, away from all the worldly turmoil!” Damian then likens Romuald’s devotion to God to a tree’s growth, writing that the youth “tried to straighten himself and move toward higher goals.”[27] The anecdote points to Romuald’s early desire for a solitary life amidst the quiet of the forest and appears not only in written sources, including a chapter of Petrarch’s The Life of Solitude (c. 1346 and 1356), but also in paintings that visually link the peripatetic hermit to the forest.[28]

After becoming a monk at the age of twenty at the Monastery of St. Apollinare in Classe, a scene depicted in the first predella panel of Cione’s Trinity altarpiece (Fig. 6), Romuald spent his life traveling across Italy and into parts of France, Poland, and Croatia. Alternating between founding monastic communities and living alone as a hermit, he traversed remote forested regions, including the Dolomite and Apennine mountains. In the Dream of St. Romuald (Fig. 5), the white-clad monk sleeps alone in a mountainous landscape consisting of steep rocky outcroppings and tall dark conifers. To the left, Romuald’s dream unfolds: an older monk climbs a ladder toward heaven, while two younger ones gaze upward in solemn attention. The monks’ upright postures and lifted heads echo the vertical growth of the fir trees. On average, fir trees grow to a height of 45 meters (150 feet), and in the predella, their deep green crowns stretch from bare trunks to the uppermost edge of the panel. Cione’s iconographical pairing of the monks with the trees visualizes spiritual ascent and may have been inspired by a passage included at the beginning of this essay and found in the twelfth-century Book of the Eremitical Rule. In a section allegorizing monastic virtues in relation to the seven trees planted by God in the desert, Rudolf II writes that the monk can be like the lofty, shady, and green fir tree and strive “to meditate on sublime truths, contemplate heavenly realities, and knock at the doors of the highest dwelling of divine majesty.”[29]

![Branch and foliage of silver fir [abete] in woodcut with watercolor from Mattioli’s Materia Medicinale, Venice, 1604.](https://differentvisions.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/1356/2025/06/Compton-7-692x1024.jpg)

Fig. 7. Abete [Silver Fir] in Pietro Andrea Mattioli, Dei discorsi nelli sei libri di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo della Materia medicinale, Venice: Bartolomeo de gli Alberti, 1604, p. 119. Woodcut with watercolor. Private Collection. Photo: Isabella Case.

In Cione’s panel, the tall fir trees align with the monks, who contemplate a heavenly reality and prepare to encounter divinity. In the center of the panel, Cione also includes a young fir tree. A distinguishable feature of this seedling is its cruciform shape, as seen in a branch and foliage of the Abete [Silver Fir] from Pietro Mattioli’s Materia medicinale (Fig. 7). The fir’s cruciform growth pattern differentiates it from other coniferous trees, such as spruce, larch, or pine. Numerous fifteenth- and sixteenth-century sources assert the connection between the abete [fir tree] and the cross. In his 1570 description of the Sacred Hermitage, for example, Andrea Muñoz writes that “in its very first rise, a seedling is raised up to heaven, bearing the image of the cross with a wonderful artifice; from which the branches, which gradually fall apart from each other, keep the same shape of a cross, completing the whole tree in a sealed manner.”[30] In Cione’s Dream of St. Romuald, the cruciform sapling aligns with the gold cross placed on the red-and-white-draped altar. The mirrored forms underline the iconographic connection between the tree and the cross. In St. Romuald’s chapel, which was located adjacent to the chapter room at the Angeli, this panel may have reminded the brothers of their duty to cultivate new monks as well as to protect the forest of Camaldoli, whose wood provided the Order with essential construction material.[31] These duties were stressed in the Camaldolese Constitutions, which were read during weekly chapter meetings.[32]

The first recorded measure protecting Camaldoli’s forest was made on July 15, 1189, by Emperor Enrico VI, who issued an imperial decree that forbade the “building of villas or stores inside the space of a mile from the church of Camaldoli and of Fontebuono.” The penalty for breaking this measure was a fine of “10 lire d’oro.”[33] The prohibition’s purpose was to create a natural barrier that separated the hermits and monks from the outside world. In the Constitutions of Prior Gherardo of 1278, care of the trees is given to the operaio or operations manager at the Hermitage, who has the right to use the wood to ensure that “the church, the refectory, and the cells are in good condition.”[34] The operaio manages the stone- and wood-working tools; he also keeps wine and cheese in his cell for the workers that he hires. The portaio or porter is responsible for appointing a deputy “for the preservation of the fir trees,” who should “guard them faithfully” and make sure that the little ones “are not harmed by wild beasts.” No one other than these two men has permission to cut trees.[35]

A more detailed prohibition against fir tree cutting is included as an addendum to Gherardo’s Constitutions. On September 14, 1285, it was declared that everyone, as well as the Prior, is prohibited from “giving silver fir trees from the Hermitage to third parties” and that prior authorization is needed for trees to be cut for any reason other than for the construction and repairing “of the houses of the hermits and their subjects.”[36] With consent, trees could be cut for poles and beams within the “boundaries of the area in which it is allowed to reduce the fir trees.” If a monk breaks these prohibitions, he “shall be subjected to the most severe correction.”[37] The regulations, along with their associated penalties, reflect the hermits’ commitment to preserving the silver fir trees as well as the persistent external demand for the valuable fir timber.

Despite these restrictions, fir trees were sometimes sold, but only with the approval of the Superior and the Chapter of the Sacred Hermitage. In 1317, for example, the Superior and the Chapter “ratified the sale of 3000 fir trees” for the price of 2005 gold florins. These trees were sold to a Florentine and designated as being for “publicum instrumentum” or public works, likely for construction at the Duomo.[38] By 1380, the Florentine Republic had acquired their own alpine forests north of Camaldoli, and disputes between the two entities arose over boundary lines. However, as Cècile Caby has pointed out, Florentines were concerned with the deforestation of Camaldoli. In 1400 and 1404, Coluccio Salutati wrote two letters to the Prior General of the Order, urging him to preserve “this sacred wood” for the benefit of the Sacred Hermitage and for the “pleasure of visitors.”[39] These letters characterize Florence as a “protector” of the forest, valued not only for its wood but also for its role in sustaining eremitical life at Camaldoli.

Ecomateriality: The Sacred Hermitage

Fig. 8. Florentine School, possibly by Don Giuliano Amidei, The Death of St. Ephraim and other Scenes from the Lives of the Hermits, c. 1480-1500. Tempera on panel. Private Collection. Photo: National Galleries of Scotland.

One of the first depictions of the Sacred Hermitage as an autonomous monastic site appears in The Death of St. Ephraim and other Scenes from the Lives of the Hermits (Fig. 8), most likely painted between 1480-1500 by the Camaldolese monk, Don Giuliano Amidei. This horizontal panel offers a bird’s-eye view of an ascetic landscape populated by early Christian desert fathers and more contemporary spiritual leaders, such as St. Francis of Assisi, who received the stigmata along the ridgeline of the Casentino region. Amidei entered the monastery of San Benedetto fuori della Porta a Pinti in Florence in 1446 and may have received artistic training at Santa Maria degli Angeli. He later held leadership roles at Camaldolese monasteries in the Arezzo province and at Valdicastro, the site of Romuald’s death in 1027.[40] Amidei’s painting resembles other horizontal panels of the Lives of the Desert Fathers, such as Fra Angelico’s Thebaid of the 1420s. The popularity of the genre in Florence occurred around the same time as the vogue for cassone and spalliere panels, which featured small-scale romance and war narratives set within meandering landscapes.[41] As Florentine artists turned to nature armed with new perspectival techniques, they increasingly rendered recognizable regional features, such as the rugged Apennine terrain of the Casentino region.

Fig. 9. Detail of hermitage in Florentine School, possibly by Don Giuliano Amidei, The Death of St. Ephraim and other Scenes from the Lives of the Hermits, c. 1480-1500. Tempera on panel. Private Collection. Photo: National Galleries of Scotland.

In the upper right corner of Amidei’s Death of St Ephraim, the Sacred Hermitage (Fig. 9) appears beneath a ridgeline of tall firs, which mark the border of Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna. Water flows from the Hermitage down into the valley where a trio of Florentine aristocrats in red observe the miracles in the landscape. Nestled between two peaks, the Hermitage includes a gate, a church, and a series of cells divided by gardens and paths. The organization of cells in vertical rows conforms to the laura plan typical of early Eastern eremitical communities in Egypt and Syria, where hermits lived in isolated caves during the fourth and fifth centuries.[42] At Camaldoli, the laura preserved an early Christian tradition in a Tuscan landscape and its material construction reflected the Order’s ecological consciousness and use of natural resources.

The value of wood for an eremitical life in the Apennine mountains cannot be overestimated. Wood was essential for a hermit’s shelter, warmth, and sustenance. In his Life of Blessed Romuald, Peter Damian recounts how the abbot of Valdicastro, offended by Romuald’s rebukes for “abandoning his solitary cell” and failing to “limit his fraternal visitations to feast days,” had “the wood set aside for the building of Romuald’s cell chopped to pieces.”[43] Damian writes that this act forced Romuald, “this tall cedar of paradise,” to be chased “from the woods of earthly men.”[44] Romuald then moved into the Apennine region of Tuscany. In Damian’s Vita, God is praised for having blessed the Apennines with “the splendor of so great a star.”[45] Several of Romuald’s tree-related miracles occur in this region. In a location known as Aquabella, for example, Romuald ordered a large beech tree near his cell to be cut down. The tree was leaning close to his cell, and the workers were worried it would fall on him. According to Damian, the tree came down “with a loud roar;” however, by “divine power,” it fell in the opposite direction, away from Romuald’s cell. All were amazed by the “miracle,” and “raised their joyful voices to heaven and gave boundless thanks to God.”[46]

The procurement of wood and the building of new cells at the Sacred Hermitage took money, materials, and labor, and construction was sponsored sometimes through outside patronage. Each cell (unless otherwise authorized) followed a standard design with a garden, a portico, an ancillary room, and a living room or cameretta. The ancillary room was used to store wood, to cook, and to wash. Hermits required large amounts of wood for heat and light during the winter months, and even in the summer, due to the region’s cold, damp climate. Chestnut wood, rather than the more precious silver fir, was used for fuel, and each hermit’s cell received a measured allotment during the summer, as noted in Silvano Razzi’s Description of the Sacred Hermitage from 1572.[47] The ancillary room, as Razzi points out, also housed the water source for the cell. He writes that within this room, “water from a living source” continually flows.[48] Designed under the guidance of the hermits, this hydraulic system channeled the mountain streams through wooden conduits and supplied the cells with fresh water.

Fig. 10. Bed of St. Romuald in cell of St. Romuald, Sacred Hermitage of Camaldoli, Casentino Forest, Monte Falterona, 27 October 2024. Photo: Mauro Toccaceli / Alamy Stock Photo.

The main living area of a hermit’s cell consisted of a small room, or cameretta, measuring about five or six braccia square. It contained a bed (Fig. 10), which Razzi describes as “a small bed placed somewhat high up, and closed all around, and above, except on the front side, with boards of silver fir.”[49] The cameretta also held fir furnishings, including a small table for eating and a recessed nook or scrittoio with shelves for books. During Advent and Lent, hermits were required to take their meals on the floor of this room, barefoot and reading sacred texts, such as the Old and New Testaments, Lives of the Desert Fathers, and the Lives of the Saints. On most fasting days, their meals consisted of salted bread and water.[50] Devotional practices and the celebration of Mass took place in the adjoining room, arranged as an oratory or private chapel (Fig. 11). This consecrated space was outfitted with a wooden altar and kneeler(s). According to Razzi, the hermits recited the Roman Mass here, with license from the Superior, and were permitted to pray and to meditate in this space “with incredible quiet and comfort.”[51]

Fig. 11. Oratory, Cell of St. Romuald, Sacred Hermitage, Camaldoli. Photo: Rebekah Compton / Isabella Case.

The occupant of the Medici-sponsored cell would have performed Mass, recited psalms, and engaged in contemplative meditation while kneeling in the oratory and gazing upon Lippi’s Adoration of the Child. The composition of the painting is notable for its combination of two distinct styles: 1) the iconic, hierarchical arrangement of the figures and 2) the more naturalistic setting. The painting’s steeply rising background reflects both the altitude of the Hermitage’s location and the spiritual ascent of the viewer, who, kneeling before the image, is positioned to gaze upward in contemplation. The work’s imagery resonates with the earliest description of Camaldoli’s founding and echoes the recurring imagery of trees and mountains in the Psalter. The psalms appointed for Friday in the Divine Office (Psalms 85-100), for example, include passages such as: “Then will all the trees of the wood shout for joy at the presence of the Lord, for he comes, he comes to judge the earth.”[52]

Set within the oratory’s distinctive sensory environment of brown hues, wood grains, and spruce-scented air, the landscape of Lippi’s Adoration offered a welcome vision of verdant life amid the white snow and gray clouds of winter. Storms in the Apennine mountains, particularly in December and January, could be brutal. Ambrogio Traversari, the Prior General of the Order between 1431 and 1439, recounts a violent snowstorm he faced in route from Poppi to the Monastery of Fontebuono on December 6. Traversari writes that he “fell prey to the terror” of the storm and describes the snow, sticking to his eyes, face, and even inside his clothing.[53] He explains how “the scream of the howl of the storm shook the forest with terrifying force; on the right side of the road, I was deafened by the waterfall of the stream that runs between rocky banks.”[54] While Traversari’s account evokes the fear and physical discomfort of Camaldoli’s winter storms, the season’s beauty is captured in Ludovico Porciano’s Description of the Sacred Hermitage, a manuscript written between 1464 and 1465 in the cell, as the author notes, “built by the generous hand of Piero.”[55] In his account, Porciano describes how in the winter, the sky becomes “as though wool” and the region “white with snow.”[56] Snow could accumulate to the height of the cell roofs, as seen in a winter photograph of the Hermitage (Fig. 12), and hermits had to receive their provisions through their chimneys. Amid this brilliant white, Porciano points out that the “green fir tree, adorned with gleaming crystals, presents to the viewer a most joyful sight in the glow of the sun.”[57]

Fig. 12. Hermitage of Camaldoli in Casentino after heavy snow, 11 February 2012. Photo: Alberto Fornasari / Alamy Stock Photo.

In his tour of the grounds, Porciano refers to the Sacred Hermitage as the “flourishing cloister, embraced by fir-wood porticos.”[58] He urges his reader to pause and “to contemplate the [fir tree’s] trunk: note its straightness and the orderly arrangement of its branches, which imitate the form of the cross.”[59] Ludovico then invites the visitor to “notice also the precious liquid flowing from the rich bark of the tree, called resin, which is a most useful remedy, especially for healing wounds.”[60] The exuding liquor, as he remarks, recalls the salvific blood of Jesus.[61] A medicinal liquor called “lacrima d’abeto” or “tear of the fir tree” is first recorded in 1460 at the pharmacy of Fontebuono.[62] In the sixteenth century, Andrea Muñoz describes how the oil, “a wonderful liquid, suitable and useful for many things,” is retrieved from penetrating the “strongest and most solid nodes” of the tree with “some sharp iron tool.”[63] This tapping of the tree required a hole to be cut. In the Adoration, Lippi registers a circular extraction wound on the splintered tree stump behind the Virgin Mary. The jagged remnants of the tree reveal that its life was cut short, by man or by the divinely ordained forces of nature.

With its green grass, wildflowers, and young saplings, the landscape of Lippi’s Adoration suggests the vernal months of late spring and early summer in Camaldoli, a seasonal iconography related to the painting’s liturgical purpose and its therapeutic virtues. During June, the Hermitage and Monastery celebrated the regionally popular feast days of St. Romuald (June 19) and St. John the Baptist (June 24), both of which align with the summer solstice. A liturgical handbook from the Angeli recommends green textiles for these two feasts, which follow the octave of Corpus Christi, when green decorations are to be used “for the love of summer’s vegetation.”[64] Both feasts are designated as “solemnitas plena” or “full of solemnity,” a classification that determines the duration, décor, chants, and readings appropriate to the occasion. The feast day of St. Romuald, for example, begins at sundown with Vespers I on the day before the feast day (June 18) and concludes at Vespers II on the feast day (June 19).[65]

The seasonal verdancy alluded to in Lippi’s Adoration of the Child and in Porciano’s Description of the Sacred Hermitage also correlates with fifteenth-century pharmacological beliefs that green’s temperate chroma was beneficial for the mind, body, and spirit. Discussions of green’s therapeutic properties can be found in the ancient writings of Aristotle and Pliny the Elder, in the medieval work of Hildegard of Bingen, and in various treatises from the fifteenth century.[66] Marsilio Ficino, who visited Camaldoli in the 1470s, writes in his Three Books on Life that green things, so long as they stay green, possess a lively, youthful, and salubrious humor that “flows to us through the odor, sight, use, and frequent habitation of and in them.” For Ficino, green’s temperate, tender, and moist qualities strengthen the body and spirit, particularly through visual contemplation.[67]

Ficino’s theories correlate with the development of landscape painting in mid-fifteenth-century Florence, particularly the innovation of setting sacred figures within a naturalistically receding green background rather than against a flat, reflective gold ground. In his Adoration, Lippi employs perspective and geometry and manipulates pigments and binders to invite the viewer into his verdant woodland. Lippi’s fir trees are identifiable by their tall straight trunks and dark foliage. The artist carefully delineates the pliable needle-like foliage of the trees with individual brushstrokes laid down in a vertical-horizontal pattern that mimics the tree’s cruciform growth. Clay soil fosters the growth of silver firs, and Lippi paints his soil using pigments procured from the earth. Restoration reports from 2014 reveal that Lippi used “green earths and iron oxides diluted in oil” for the background landscape.[68] Lippi’s use of oil rather than egg yolk allowed him to layer the green earth, red ocher, and brown umber in transparent glazes that resemble the colorful clays typical of Camaldoli’s soil layers. For the grasses and low vegetation, Lippi employed malachite and lead-tin yellow.[69] Malachite originates in copper mines and was sourced from the Black Forest of Germany. During the second half of the fifteenth century, this pigment became highly desirable and rather expensive, as Florentine artists began to include naturalistic settings of grass, moss, and foliage within their sacred and secular paintings.[70]

Filippo Lippi’s Medici Chapel Adoration and the Art of Silviculture

Fig. 13. Medici Chapel with frescos by Benozzo Gozzoli and a copy of Filippo Lippi’s Adoration of the Child. Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence. Photo: Hemis / Alamy Stock Photo.

Filippo Lippi’s Adoration of the Child (Fig. 1) for the Sacred Hermitage presents a luminous, verdant landscape that differs from the one depicted in the artist’s slightly earlier Adoration in the Forest (Fig. 3), painted in c. 1459 for the altar of the Medici family’s private household chapel (Fig. 13).[71] The differences in green hues may result from varnish or pigment aging, particularly the darkening of copper-based greens, or from differences in cleaning campaigns.[72] The contrast may also indicate Lippi’s depiction of two distinct forest zones. While the Hermitage panel evokes the fir-encircled clearing of Camaldoli’s upper forest, the Medici Chapel Adoration seems to reference the denser, lower woodland characteristic of the Monastery of Fontebuono. The differences in the two forest zones are indicated in Isidore the hermit’s 1629 engraving of Camaldoli (Fig. 4).

The Medici family had provided financial support to the Monastery of Fontebuono since at least 1434, when Don Ambrogio Traversari requested funding from Cosimo de’ Medici for a second cloister to house his new school for youths. In 1438, Cosimo’s brother, Lorenzo, obtained transparent Venetian glass for the windows, bringing light and warmth into the monastery.[73] Correspondence with Camaldoli continued with Cosimo’s children, Giovanni and Piero. As Stephanie Solum has argued, it is likely that Piero and his wife Lucrezia Tornabuoni oversaw the commissioning of the family chapel’s altarpiece.[74] Lucrezia was a devotee of St. Romuald, whom she credited with saving her from a mortal illness in 1468. In a letter dated 1474, the abbot of the Monastery of Valdicastro thanks Lucrezia for sending a paramentum or canonical cloth woven with gold thread for the wrapping and displaying of St. Romuald’s relics.[75] As Solum also pointed out, Lucrezia owned property in the Casentino region, and a letter of 1473 reveals her plans to construct a lake from the descending mountain streams, three miles from the Sacred Hermitage.[76]

Lippi’s Medici Chapel Adoration contains visual cues that resonate with the working landscape of Camaldoli, such as the axe and trees depicted at various stages of growth, felling, and refinement.[77] A stream on the viewer’s right resembles the channel that collected water from Camaldoli’s seven mountain springs, from which the Monastery of Fontebuono took its name. The channel carves a meandering line down the mountain, as seen in the 1629 engraving. In the painting, Lippi animates the water’s movement with a transparent white paint that he twists and curves into a foamy flow. This river powered the sawmill installed at Fontebuono in 1458, shortly before Lippi created the Medici Chapel Adoration. The engineering for this hydro-powered sawmill, which began the commercial enterprise of logging at Camaldoli, included directing water through conduits down the grade of the mountain. The pathways were essential for the arduous task of moving timber down and across the steep, rocky terrain.

In the Adoration, Lippi leads the viewer into the forest with a perspectival system that follows the natural sight lines of the tree trunks, which become thinner and shorter as they recede into the distance. The diagonal lines of the trees organize the composition into a triangle, symbolic of the Trinity, and mimic the actual practice of planting fir trees in straight lines for easier harvesting. Lippi depicts at least 50 tree trunks, not including those that have been cut, and it is in this denser area of the lower forest that the practice of silviculture took place. Raoul Romano explains that the harvesting of trees at Camaldoli followed a process laid out in book 5 of the Enquiry into the Plants by Theophrastus (c. 371-287 BC).[78] This process consisted of three phases: 1) the cutting of the tree within the forest; 2) the collection and transport of timber by land and river; and 3) the processing of wood into lumber with an assortment of sizes.[79]

Fig. 14. Detail of St. Romuald with a felled tree in Filippo Lippi, Adoration in the Forest, c. 1459. Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Photo: Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo.

In the fifteenth century, the cutting of a silver fir tree began with an axe and trees fell to the forest floor with their branches intact. In Lippi’s Adoration, St. Romuald prays above one of these unrefined trees (Fig. 14). Its location on the edge of a steep precipice recalls a tree miracle included in Peter Damian’s hagiographic account. In the Apennines, St. Romuald and his workers were cutting down an enormous oak tree, when it “rolled over the precipice and down the slope, struck a farmer, and dragged him down.”[80] Everyone feared the worst: that the man was dead. Damian explains, however, that “the divine power was amazing.” The man was safe, “as if an oak leaf had fallen instead of a tree.” Damian writes that St. Romuald “must have carried great weight with God: in his presence, the enormous mass of the tree lost all its weight.”[81] Damian’s anecdote and St. Romuald’s prayerful gesture over the fallen tree underscore the seasonal hazards of felling, chopping, and transporting massive trees as well as the saint’s intercession on behalf of those at risk.

In the forest, timber was refined and measured at the fall bed, and irregular trees and logs were sent to the sawmill to be processed as lumber. Fir wood was cut into specific shapes and sizes, including piane (boards for flooring), antenne (poles for the sails of ships), bordone (posts for fencing), decorenti (framing or sheathing wood for roofs), and arcali (border frames for doors).[82] Tall timber was removed from the fall bed using a traino or sled consisting of two long pieces of wood joined together in the shape of a triangle and pulled by oxen over well beaten tracks. Wooden bridges were erected for crossing streams and channels of water, as seen in the right of Lippi’s panel.[83] Wood was prepared by October for transport during the winter months, when the waters of the Arno were full and construction had slowed in the cities of Florence and Livorno. The wood arrived in these cities for purchase in the spring.[84]

Fig. 15. Detail of fallen fir tree, splintered stump, and refined trunk in Filippo Lippi, Adoration in the Forest, c. 1459. Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Photo: Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo.

In Lippi’s Adoration, trees appear in different states of refinement, which may allude to the increase of logging in the forest of Camaldoli.[85] Lippi is quite attentive to the foliage, bark textures, and inner anatomy of the trees. In the foreground (Fig. 15), Lippi paints a fallen fir tree, angled so that the viewer looks through its boughs. Branches laden with evergreen needles lie across the Virgin Mary’s mantle. Against the celestial blue, Lippi used his brush to delineate small green crosses that branch out into smaller crosses. Above the fallen fir, Lippi includes a jagged and torn tree stump, whose trunk appears to have been shattered by a force greater than an axe. Then, nearby, a more refined tree trunk, whose branches have been hewn and whittled away to a smooth finish. Below it may be a stack of cleanly cut, squared lumber. In the opposite corner of the painting, next to the axe (Fig. 16), Lippi represents a horizontal cross section of a felled tree that displays alternating light and dark rings of growth. Cut vertically, this part of the tree provided the much-desired heart wood. Lippi lays in the bark textures, forming variations in the wood with highlights of lead white and lead-tin yellow mixed with a brown iron oxide.[86]

Fig. 16. Detail of axe with artist signature in Filippo Lippi, Adoration in the Forest, c. 1459. Gemäldegalerie der Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Photo: Peter Barritt / Alamy Stock Photo.

The artist signs his name on the foreground axe: Frater Phillipus. P [Fra Filippo P[ainter]. This signature copyrights Lippi’s design; it is one of only two signatures found in his oeuvre.[87] The axe is a significant choice because it is the tool used to chop, cleave, split, and hew felled trees. Hand-hewing with an axe required geometry, line, and measurement to transform the natural material of the tree’s trunk and branches into poles, beams, and planks.[88] In the painting, Lippi too uses geometry, line, and measurement for the perspective, composition, and alignment of his design. His signature thus relates to craftsmanship and the wielding of tools for the creation of beauty. Such a signature in the 1460s fits with trends in artistic circles to copyright designs, and Lippi’s Adoration would become one of the most reproduced devotional compositions in the fifteenth century.[89] In the context of the Medici Chapel, Lippi’s painting provided a cutting-edge depiction of a Tuscan landscape as the background of the chapel’s altarpiece. The painting – in ways similar to Donatello’s David and Pollaiuolo’s Hercules and Anteas – may have reminded the Medici family of their duty to protect Florentine interests, in this case the forest of Camaldoli.

In the summer of c. 1472, the young Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano – both of whom had repeatedly viewed Lippi’s painting in their household chapel – traveled to Camaldoli and stayed at the Monastery of Fontebuono.[90] The trip is described in Cristoforo Landino’s Disputationes Camaldulenses. Landino explains that the group chose Camaldoli to escape the heat of the summer and to “rest their souls” in the vernal climate and healthy air.[91] The group included Florentine literati (Alamanno Rinuccini, Peter and Donato Acciaiuoli, Marcus Parenthius, and Antonio Canisianus) as well as Leon Battista Alberti and Marsilio Ficino. Mariotto Allegri cared for the group.[92] The men slept at the Monastery of Fontebuono, rose early to attend the Divine Office, then walked through the mountains for health and pleasure.

Each day, they stopped in a flowering field with a beech tree growing beside a transparent, clear fountain. Landino describes the pleasure that the group found for the eye in the “beauty of the landscape” and for the mind and soul in the “the vestiges of ancient religion.”[93] In this locus amoenus – though one dedicated to divine love – the group philosophizes on the virtues of the active and contemplative ways of life, a discussion lead by Leon Battista Alberti. The necessity of this philosophical discussion and of time to withdraw from public affairs is voiced by Alberti, who asserts that “Lorenzo and Giuliano, should do so as often as possible. For you see that the whole weight of the Republic must soon rest on your shoulders due to your father’s worsening illness.”[94]

The Medici brothers and their entourage stayed at the recently renovated Monastery of Fontebuono. In 1456, Leonardo, the chancellor to Mariotto Allegri, wrote a description of this restoration project, which reveals its designers’ and builders’ ecological use of local materials.[95] The letter begins with an account of the Monastery’s numerous structural problems. The roofs, for example, were collapsing, so expert workers from Santa Maria of Impruneta were hired. According to Leonardo, the workmen used “diverse clods of earth of different colors from different places in the forest” and with “common wood material,” they assembled the roof.[96] The oldest parts of the monastery had to be completely restructured because the dwellings were “very rustic” and “quite uncomfortable.”[97] Moreover, a “multitude of shrewmice,” had invaded the building and “were most injurious to the inhabitants for their number and size.”[98] The walls were rebuilt “almost from the foundations.” Leonardo points out that “two huge fir trees, the like of which are not equaled in the whole house” were used “to support the weight of the upper building.”[99] Leonardo’s account reveals the rich reserve of natural construction materials in the forest of Camaldoli and their value for rebuilding the Monastery of Fontebuono.

The building campaign undertaken during Allegri’s tenure as General Prior aided in the promotion of Camaldoli as an ancient establishment of religion, located in a sacred region of Tuscany.[100] Commercial logging began in Camaldoli during these years and renovations were undertaken to better house visitors at the Monastery of Fontebuono. During this period, Lippi and several writers set their compositions within the vernal environment of Camaldoli. Indeed, with the increase in logging and desire for wood, management of the forest was becoming increasingly urgent. Perhaps, not by circumstance, the Order received the wisdom of Paolo Giustiniani, whose knowledge of forest management may have been learned in Venice. Indeed, the city was home to the oldest forest bureaucracy and management system in Europe. Since the early fifteenth century, the Venetian State had been focusing on policies and practices to govern the cutting and replanting of its mainland forests.[101]

Concern for the deforestation of Camaldoli is the subject of a series of letters dated to 1512 between Paolo Giustiniani and his Venetian friend, Pietro Quirini. The letters note that on May 8, Cosimo Pazzi, the Archbishop of Florence, “has been appointed to judge the dispute occasioned by the cutting down of the forests of the Hermitage.”[102] The appeal to the Archbishop of Florence to judge the dispute underscores earlier connections between the city and Camaldoli, such as the letters written in 1400 and 1404 by Coluccio Salutati that urged the Prior General to protect the sacred woodland. The necessity of preserving and enlarging Camaldoli’s stands of trees is emphasized then in Giustiniani’s revised Constitutions of 1516, known as the Regola della vita eremitica. This text provides cutting restrictions and price margins for existing stands as well as mandates for planting four to five thousand new firs per year. Giustiniani explains that these trees not only protect the hermits’ solitude and silence but also surround the hermitage with an incredible, awe-inspiring beauty.[103]

In 1537, the forest and its inhabitants restored the artist Giorgio Vasari, who was in a severe depression following the death of Duke Alessandro de’ Medici. In a letter written to Giovanni Pollastra, Vasari explains how his mind is “gripped by terrifying and melancholic imaginings,” his mind is “so infected,” that if he continues in these thoughts, he will certainly meet an “unfortunate end.”[104] However, after two days at Camaldoli, he finds himself good and healthy. He writes:

Already, I begin to recognize how mad I was, where blindness was leading me. Here, on this high ridge of the Alps, among these straight fir trees, I perceive the perfection that comes from quietude. Just as every year they form around themselves a ring of branches shaped like a cross, growing straight toward heaven, so these holy hermits imitate them—and all who dwell here—detaching themselves from worldly things, lifting their spirits to God, growing ever closer to perfection. And just as they do not care for worldly temptations or vanities, even though the winds crash down and the storms beat and strike them continually, still they flourish more than us; for when the skies clear, they become straighter, stronger, more beautiful, and more perfect than ever. It is clear that heaven bestows on them constancy and faith—just as it does on these souls who serve God with all their being.[105]

Vasari’s letter continues in an uplifting tone, noting that the monks have asked him complete panel paintings and frescos for the high altar and rood screen (tramezzo) of the monastery’s church.[106]

Fig. 17. Giorgio Vasari, The View of a Hermitage, c. 1538, INV 2213, Recto. Black and brown ink with white highlights, black chalk. Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo: Michèle Bellot / © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

Though Vasari’s frescos were destroyed in eighteenth-century renovations to the Church of SS. Donato and Illariano, the artist’s scaled drawing of The View of a Hermitage (Fig. 17) survives. Likely granted special permission to undertake this rendering, Vasari maps out the Hermitage with precision: hermit cells step up the steep perspective in gridded alignment. The perimeter of the clearing is encircled by fir trees, whose canopies cast shadows in washes of brown ink. The wooden fence seen at mid-ground encircles the clearing and encloses the sacred zone from humans and animals. Chimneys are prominent throughout, indicating the warmth required for the eremitic life. In the foreground, St. Romuald grasps his whittled tau-shaped staff and prayer beads, a new addition to his iconography that correlates with sixteenth-century devotion. With his right hand, Romuald touches his heart, as he does in Lippi’s Adoration, and looks up, visualizing the Hermitage. Social interaction occurs outside its gates, preserving the inner silence, a silence so complete, Vasari claims, that “not even the fir leaves dare to speak with the winds. And the waters flow through wooden channels, across the hermitage from one hermit’s cell to another, as a clear stream in marvelous, respectful silence.”[107]

Vasari’s The View of a Hermitage was likely completed in September or October of 1538, when he received supplies and payments for work on the tramezzo.[108] The archival contracts and ledgers related to the artist’s work at Camaldoli have been gathered by Manuala Alotto, who points out the priority given to wood within them. In 1542 and 1543, over twenty traini or sleds of fir planks and beams were shipped to Vasari’s home in Arezzo. This document explains that a traino of fir planks is 5 lire a load, while eight fir beams cost 28 lire.[109] In 1569, some years after completing his work for Fontebuono, Vasari was partially paid in sled loads of fir wood for his Assumption, a large-scale wood panel painting for the high altar of the Hermitage’s Church of Holy Savior. As noted in the Acta Capitularia (1563-1585), Vasari was provided with 200 traini or sled-loads of silver fir timber, delivered directly to his house in Arezzo. Some of this wood may have been used for the framework, doors, and ceiling of his house.[110]

Fig. 18. Gabriello di Vante, known as Attavante degli Attavanti, The Dream of St. Romuald, c. 1502. Daniel Wildenstein Collection, Inv. M 6016, musèe Marmottan Monet, Paris. Photo: © musèe Marmottan Monet.

Though not pointed out thus far in art historical scholarship, the forest of Camaldoli developed a recognizable landscape in art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Sacred Hermitage with its belt of silver fir trees surrounding a green clearing and its individual cells with gardens and porches appears in later artworks as well. Paired down references via a church and a ring of trees can be seen in Franceso Salviati’s Madonna and Child with Saints, painted for the Camaldolese female monastery of Santa Cristina in Bologna and in Francesco Morandi’s Christ as Man of Sorrows with Angels and Saints.[111] A detailed rendering of the Hermitage appears in Attavante degli Attavanti’s Dream of Saint Romuald (Fig. 18), painted in a missal belonging to the Medici family, and an imagined one materializes in El Greco’s Allegory of the Camaldolese Order (Fig. 19) of c. 1597, commissioned in connection with Fray Juan de Castañiza’s petition to Philip II in 1597 to establish the Camaldolese Order in Spain.[112]

Fig. 19. El Greco, Allegory of the Camaldolese Order, 1597. Museo del Patriarca, Valencia. Photo: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo.

As this essay has illustrated, paintings created in Florence between 1350-1470 offer visibility to Camaldoli’s forest ecosystem. The silver fir trees, which define its topography and iconography, not only protected the solitude and silence of the hermits and monks, but also provided the cities of Florence and Livorno with a yearly supply of valuable wood. The hermits had a duty to protect and cultivate their forest, as outlined and revised in each new set of Constitutions. The regulations exemplify aspects of medieval and early modern forest management, including the planting and felling of trees, the hauling and selling of timber and lumber, and the oversight of streams, channels of water, bridges, roads, and laborers. By employing ascetic principles, the Hermits of Camaldoli sustained the natural resources of their forest. As this essay reveals, Florentine paintings created in the fourteenth and fifteenth century visualized the critical value of Camaldoli’s evergreen landscape to the hermits, monks, and city of Florence, encouraging all to preserve and sustain it.

References

| ↑1 | Isaiah 14:7-8, 10 in The Holy Bible: Douay-Rheims Version, trans. from the Latin Vulgate (Charlotte, NC: Saint Benedict Press, 2003), 772. My acknowledgments to the monks of the Monastery of Fontebuono and Hermits of the Sacred Hermitage for their generous hospitality during my stays at Camaldoli and for the inspired forest visits with Andrew Chen, Denva Gallant, Machtelt Israëls, Cark Strehlke, and Anne Derbyshire. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Peter-Damian Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality: Essential Sources (Bloomingdale, OH: Ercam, 2007), 259. |

| ↑3 | Fra Filippo Lippi’s painting is described in the Latin Annali of the Camaldolese Order as being located in a cell built at the Sacred Hermitage by Piero de’ Medici and his wife, Lucrezia Tornabuoni. For the entry, see Giovanni Benedetto Mittarelli and Anselmo Costadoni, eds., Annales Camaldulenses Ordinis Sancti Benedicti, vol. 7 (Venice: Pasquali, 1755-73), 270. For Giorgio Vasari’s description of the painting, see Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the most eminent painters, sculptors, and architects, vol. 3 (London: Macmillan, 1912), 81. |

| ↑4 | Several copies of the print are known, including one at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et planes, GE BB-246 (XII, 100-101). |

| ↑5 | For a discussion of Lucrezia Tornabuoni’s writings on John the Baptist, see Stephanie Solum, Women, Patronage and Salvation in Renaissance Florence. Lucrezia Tornabuoni and the Chapel of the Medici Palace (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 109-168. |

| ↑6 | Oftentimes, scholars mis-identify St. Romuald for St. Bernard of Clairvaux. For scholarship on Lippi’s paintings, see Megan Holmes, Fra Filippo Lippi: The Carmelite Painter (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 172-82; Jeffrey Ruda, Fra Filippo Lippi: Life and Work (London: Phaidon, 1993), 224-33. Solum correctly identifies the saint as St. Romuald and connects the landscape to the Casentino region; see Solum, Women, Patronage and Salvation, 167-212; Scott Nethersole, Art and Violence in Early Renaissance Florence (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 222-30; Benjamin Tilghman, “Script, Pseudoscript, and Pseudo-pseudoscript in the Work of Filippo Lippi,” in The Hidden Language of Graphic Signs: Cryptic Writing and Meaningful Marks, ed. John Bodel and Stephen Houston (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 106-11. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108886505.008. |

| ↑7 | James Pilgrim, “Jacopo Bassano and the Flood of Feltre,” Art Bulletin 105 (2023): 115-37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2023.2176648; David Peterson Bardeen, “Harvest, Rot, Blood: Rethinking the Tree Stump in Italian Painting,” I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance 28 (2025): 51-80. https://doi.org/10.1086/734800. |

| ↑8 | On landscape and water thaumaturgy, see Ellen F. Arnold, Medieval Riverscapes: Environment and Memory in Northwest Europe, c. 300-1100 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2024); Ellen F. Arnold, “Engineering Miracles: Water Control, Conversion and the Creation of a Religious Landscape in the Medieval Ardennes,” Environment and History 13 (2007): 477-502; Alison Perchuk, The Medieval Monastery of Saint Elijah: A History in Paint and Stone (Turnhout: Brepols, 2021). |

| ↑9 | Gregory C. Bryda, The Trees of the Cross: Wood as Subject and Medium in the Art of Late Medieval Germany (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023). For studies of eco-materiality, see David P. Bardeen, “Grains Stains, and Worms: Designing from Wood in Early Modern Italy, 1450-1530,” Art Bulletin 106 (2024): 88-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2024.2381992; Anne Harris, “Water and Wood: Ecomateriality and Sacred Objects at the Chapel of Saint-Fiacre, Le Faouët (Brittany),” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 44 (2014): 585-615. https://doi.org/10.1215/10829636-2791548. |

| ↑10 | For art historical studies of hermits in the ascetic landscape of the desert, see Lyle Massey, “Ascetic Ecology: Landscape of a Desert Saint,” in Making Worlds: Global Invention in the Early Modern World, ed. Angela Vanhaelen and Bronwen Wilson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022), 301-30; Denva Gallant, “Into the Desert: Demons, Spiritual Focus, and the Eremitic Ideal in Morgan MS M.626,” Gesta 60 (2021): 101-19; Alessandra Malquori with Manuela De Giorgi and Laura Fenelli, eds., Atlante della Tebaidi e dei temi figurativi (Florence: Centro Di, 2013); Luciano Patteta, “Eremi e ‘santi deserti’: novità tipologiche nel XVI-XVII secolo,” Arte lombarda 105/107 (1993/1994): 206-11. |

| ↑11 | For Salutati’s letters, see Voir D. De Rosa, Coluccio Salutati, il cancelliere e il pensatore politico (Florence: Aracne, 1980), 55-56. For a discussion of this letter and other evidence regarding tourism in the Casentino and at Camaldoli, see Cécile Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli pour Pierre Le Goutteux. La Heremi descriptio de Ludovicus Camaldulensis monacus (Florence: Florence University Press, 2021), 29-35. |

| ↑12 | One of the earliest recorded sales of fir trees to Florence from Camaldoli took place in 1317, when 3000 fir trees were sold to the city for public works; see Annales Camaldulenses, vol. 6, 265. Records for wood sales in Florence begin to be documented in 1470 in the first of the Libri della foresta. For a discussion of the transport and sell of wood from Camaldoli to Florence, see Raoul Romano, Sonia Marongìu, and Carlo Urbinati, eds., Codice forestale Camaldolese. Foresta e monaci di Camaldoli: un rapport millenario tra gestione e conservazione (Rome: Inea, 2012), 112-44; hereafter cited as Foresta e monaci. |

| ↑13 | The original grant of the land to Peter Dagnino, a disciple of Romuald, was made by the Bishop of Arezzo, Teobaldo di Canossa in 1027. The grant identifies the boundaries of the land, which are defined by seven pure water sources. Knowledge of the forest’s use from the tenth through the fourteenth centuries is scarce and limited to the management and cultivation of the trees, predominantly for inner-institutional use in Constitutions and Amendments between the Monastery of Fontebuono and the Sacred Hermitage. In the fifteenth century, the economic value of the wood increased with the installation of the hydraulic sawmill, as did documentation of the prices, cuts, and profits from the sale of wood. For this development, see Foresta e monaci, 9, 21-47; for “Donation” of Bishop Teobaldo, see 21; for “Libri della Foresta,” see 116-17. |

| ↑14 | Documents related to the Camaldolese management of the forest are in the Archivio di Stato di Firenze and the Archivio storico dell’Eremo e Monastero di Camaldoli. For the first study of the secular relationship between the monks of Camaldoli and the forest, see Giuseppe Cacciamani, L’antica foresta di Camaldoli. Storia e codice forestale con illustrazioni fuori testo (Florence: Camaldoli, 1965). For further research and documents of this relationship, see Giorgio Zattoni, “L’antica foresta di Camaldoli,” Dendronatura 1 (1989): 7-19; Francesco Cardarelli, Il codice forestale camaldolese. Legislazione e gestione del bosco nella documentazione d’archivio romualdina (Bologna: Bononia University Press, 2010). For a historiography of the scholarship on the Camaldolese forest, see Romano, “Le fonti storiche,” in Foresta e monaci, 67-72. |

| ↑15 | For sources related to logging before 1500, see Raoul Romano, Codice forestale Camaldolese. Le radici della sostenibilità. La Regola della vita eremitica, ovvero le Constitutiiones Camaldolenses (Rome: Inea, 2009). For a discussion of the environmental concerns of the monks of Fonte Avellana, see Kathryn Jasper, Bounded Wilderness: Land and Reform at the Hermitage of Fonte Avellana, ca. 1035-1072 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2024). For essays on the economics of the early modern forest, see Astrid Zenkert and Daniela Bohde, eds., Der Wald in Der Fruhen Neuzeit Zwischen Erfahrung Und Erfindung: Naturasthetik Und Naturnutzung in Interdisziplinarer Perspektive (Cologne: Böhlau, 2024). |

| ↑16 | For this gold-to-green transition, see Rebekah Compton, “The Green Places of Fra Filippo Lippi and Sandro Botticelli,” in Green Worlds in Early Modern Italy, ed. Karen Hope Goodchild, April Oettinger, and Leopoldine Prosperetti (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019), 31-48. https://doi.org/10.1017/9789048535866.002. David Kim, Groundwork: A History of the Renaissance Picture (Princeton University Press, 2022), 29-116. |

| ↑17 | Ten letters preserved in the Florentine State Archives attest to Giovanni’s connections with Camaldoli and the Prior General Mariotto Allegri between 1456 and 1463. The letters between Mariotto de’ Allegri and Giovanni de’ Medici include: ASF, MAP, f. VI, 209; ASF, MAP, f. VII, 161; ASF, MAP, f. VII, 210; ASF, MAP, f. VII, 215; ASF, MAP, f. VII, 273; ASF, MAP, f. VIII, 315; ASF, MAP, f. VIII, 372; ASF, MAP, f. IX, 234; ASF, MAP, f. X, 379. Mariotto likely approved the construction of the Medici-sponsored cell, as documented in a 1464 registry entry noting his visit to the cell of Piero de’ Medici; see Archivio di Stato di Firenze (hereafter cited as ASF), Conventi religiosi soppressi dal Governo Francese (hereafter cited as CRSGF), Camaldoli, Appendix, 591, f. 21v. Cited in Cécile Caby, “Fonti testuali, fonti iconografiche e topografia monastica: l’Eremo di Camaldoli e il Monastero di Fontebuono nel medioevo,” in Architettura eremitica. Sistemi progettuali e paesaggi culturali, ed. Stefano Bertocci and Sandro Parrinello (Florence: Edifir, 2012), 41. |

| ↑18 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 213-14; Antonio Ugo Fossa, Monaci a Camaldoli. Memorie, percorsi, interpretazioni (Camaldoli: Camaldoli, 2020), 9-10. |

| ↑19 | Claudio Ubaldo Cortoni, “Comunità monastica di Camaldoli: storia e spiritualità,” in Sacra Bellezza: Tesori svelati e percorsi inedita nell’Eremo di Camaldoli, ed. Claudio Ubaldo Cortoni, Marinella Peri, and Michel Scipioni (Bibbiena: Mazzaffirra, 2021), 18. |

| ↑20 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 236. |

| ↑21 | Angelo Tartuferi, Dal Duecento agli Orcagna (Livorno: Sillabe, 2001), 32. For discussion of the chapel, see George R. Bent, Monastic Art in Lorenzo Monaco’s Florence: Painting and Patronage in Santa Maria degli Angeli, 1300-1415 (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2006), 95-96, 104-108; Dillian Gordon, “The Paintings from the Early to the Late Gothic Period,” in Santa Maria degli Angeli a Firenze. Da monastero Camaldolese a biblioteca umanistica, ed. Cristina de Benedictis, Carla Milloschi, Guido Tigler (Florence: Nardini, 2022), 189-225. |

| ↑22 | In his attempts to reform the Benedictine Order, St. Romuald placed great emphasis on the psalms, as revealed in the brief rule he gave to Bruno-Boniface of Querfurt, who included it in his “The Life of the Five Hermit Brothers.” The rule reads: “Sit in the cell as in paradise. Cast the memory of the whole world behind you, carefully attentive to your thoughts as a good fisher is to the fish. One way is in the Psalms: this, do not dismiss. If you who have come with the fervor of a novice are not capable of making use of everything, then first in this place and then in that psalmodize in spirit and understand with an attentive mind.” For text, see Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 102. |

| ↑23 | The Psalter is noted as being to the left of the altar in Ludovico Porciano’s Description of the Sacred Hermitage, written between 1464 and 1465. Porciano writes that “in the upper section of the cabinet where the sacred relics are kept,” is “the Psalter written by the very hand of the most holy Romuald, along with glosses revealed to him by the Holy Spirit.” For text, see Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 90. |

| ↑24 | For the healing powers of the tau symbol (t), see Bryda, The Trees of the Cross, 94. The iconography of St. Romuald has been little studied. George Kaftal describes his iconography as an “old bearded monk in white” that may hold a book, a crutch, or a model of a monastery; see George Kaftal, Iconography of the Saints in Tuscan Paintings (Florence: Sansoni, 1952), 895-902, for crutch, see 895. |

| ↑25 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 105-106. |

| ↑26 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 107-108. Romuald’s love of the forest is also mentioned in his feast day liturgy in Choral Book 8, written and illuminated at the scriptorium of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence in 1395. Corale 8. Antiphonary, Part VIII: Corpus Christi to Sts. Peter and Paul, 1395, choir book from Santa Maria degli Angeli, now in Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, 76v-79v. |

| ↑27 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 107-108. |

| ↑28 | Francis Petrarch, The Life of Solitude, trans. Jacob Zeitlin (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois, 1924), 226. |

| ↑29 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 259. |

| ↑30 | Andrea Muñoz, Eremi Camaldulensis descriptio (Rome: Accoltum, 1570), 7r-7v. |

| ↑31 | For an analysis of the fir wood (abete bianco) employed in the construction and remodeling of the Camaldolese Church of the Holy Savior in Florence, see Alessandra Chiavaroli, “Le strutture di legno della chiesa di San Salvatore a Camaldoli in piazza Tasso a Firenze,” Bollettino ingegneri bimestrale di ingegneria ed architettura 12 (2005): 22-24. |

| ↑32 | The Constitutions found in Libri tres de moribus, composed in 1253 by Martin III, prior of Camaldoli, state that whenever everyone is seated at the weekly chapter meeting that “the reader shall read the passage from the Gospel of the day; on weekdays, he shall read a passage from the Rule.” Martin III, prior of Camaldoli, Libri tres de moribus, trans. Pierluigi Licciardello (Florence: Sismel, 2013), book 3, 190-91. In his Regola of 1516, Giustiniani writes: “And finally, after asking for the blessing, let there be read not some incomplete portion of the Homily (as was formerly done) but a passage from the Rule or the Constitutions, provided it is not too short.” Paolo Giustiniani, Regola della vita eremitica (Florence: Sermartelli, 1575), 202. |

| ↑33 | Foresta e monaci, 37. |

| ↑34 | Annales Camaldulenses, vol. 6, 228. |

| ↑35 | Annales Camaldulenses, vol. 6, 230-31. |

| ↑36 | Annales Camaldulenses, vol. 6, 242. |

| ↑37 | Annales Camaldulenses, vol. 6, 242. |

| ↑38 | Annales Camaldulenses, vol. 6, 265. |

| ↑39 | Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 30. For letters, De Rosa, Coluccio Salutati, 55-56; G. A. Brucker, Renaissance Florence (New York: Wiley & Sons, 1969), 221. |

| ↑40 | Andrea De Marchi, “Identità di G. Amadei miniatore,” Bollettino d’arte 80 (1995): 119-58. For a discussion of Amidei’s painting, see Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 36-37; Alessandra Malquori, “La ‘grande’ Tebaide Lindsay,” in Atlante della Tebaidi e dei temi figurativi, 56-63. |

| ↑41 | For Fra Angelico’s panel in the Uffizi, see Alessandra Malquori, “La Tebaide degli Uffizi,” in Atlante della Tebaidi e dei temi figurativi, 33-38. |

| ↑42 | For a discussion of different architectural models for the hermitage, see Mark H. Dixon, “The Architecture of Solitude,” Environment, Space, Place 1 (2009): 53-72. https://doi.org/10.7761/ESP.1.1.53. |

| ↑43 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 153. |

| ↑44 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 153. |

| ↑45 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 153. |

| ↑46 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 154-55. |

| ↑47 | Silvano Razzi, Descrizione del sacro eremo di Camaldoli, et della regola, et vita de’ Padri Eremiti, che in servigio di Dio habitano quel santo luogo (Florence: Sermartelli, 1572), 25-26. |

| ↑48 | Razzi, Descrizione del sacro eremo, 25-26. |

| ↑49 | The bed included a straw mattress, a white sheet, a coverlet, and a small feather pillow. Razzi, Descrizione del sacro eremo, 24-25. |

| ↑50 | Giustiniani, Regola della vita eremitica, 127-45. |

| ↑51 | Razzi, Descrizione del sacro eremo, 25. |

| ↑52 | The Revised Grail Psalms. A Liturgical Psalter, prepared by the Benedictine Monks of Conception Abbey (Chicago: GIA Publications, 2010), psalm 96 (95), 212-13. |

| ↑53 | Ambrogio Traversari, Hodoeporicon, trans. Vittorio Tamburini (Florence: F. Le Monnier, 1985), 39-41. |

| ↑54 | Traversari, Hodoeporicon, 41. |

| ↑55 | For text, see Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 82. Translations of the Latin text were completed with the assistance of Jennifer Gerrish. One manuscript of the Descriptio is dedicated to Piero de’ Medici and includes the red palle or balls of the family set against a gold ground and encircled by a diamond ring, three feathers, and the SEMPER banner, a heraldic sign specifically associated with Piero between 1450 and 1465. Piero became head of the family in 1464 and died in 1469. Thus, Caby dates the work to between 1464-65; see Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 13, 16-17. |

| ↑56 | Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 93. |

| ↑57 | Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 93. |

| ↑58 | Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 88-89. |

| ↑59 | Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 89. |

| ↑60 | Caby, Un éloge de Camaldoli, 89. |

| ↑61 | Art historians studying depictions of bleeding trees and stumps, such as David Bardeen and Gregory Bryda, have noted that the resin of the tree, when cut or wounded, takes on the appearance of blood; see Bardeen, “Harvest, Rot, Blood,” 13-17; Gregory C. Bryda, “The Exuding Wood of the Cross at Isenheim, Art Bulletin 100 (2018): 6-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2018.1393323. |

| ↑62 | Cortoni, “Comunità monastica di Camaldoli,” 22. |

| ↑63 | Muñoz, Eremi Camaldulensis description, 7v. |

| ↑64 | Paramenti, MS Conventi Soppressi B. 2 1029, Biblioteca Nazionale Firenze, fol. 2v-3r. For green specifically, see fol. 10r-10v. |

| ↑65 | Giustiniani, Regola della vita eremitica, 79. |

| ↑66 | Ancient writers often note the curative effects of green materials, such as malachite, verdigris, and emeralds; see Aristotle, Minor Works (On Marvellous Things Heard), trans. W. S. Hett, Loeb Classical Library 307 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1938), 160-61; Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. H. Rackham, Loeb Classical Library 394 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1952), 9.34, pp. 208-13; Hildegard of Bingen, On Natural Philosophy and Medicine. Selections from Cause et cure, trans. Margret Berger (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 1999), 107. For other discussions of green’s virtues, see Michel Pastoureau, Green: The History of a Color, trans. Jody Gladding (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), 14-85; Katharine Stahlbuhk, Oltre il colore: die farbreduzierte Wandmalerei zwischen Humilitas und Observanzreformen (Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021). |

| ↑67 | Marsilio Ficino, Three Books on Life, trans. by Carol V. Kaske and John R. Clark (Binghamton: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1989), 204-05. |

| ↑68 | Daniele Rossi, “Fra Filippo nell’Adorazione di Camaldoli e nella Madonna con Bambino e Angeli della Galleria degli Uffizi a Firenze: Tinte d’oro e colla di formaggi,” Officina Pratee: tecnica, stile, storia (2014): 180. |

| ↑69 | A sample from the painting reveals the malachite in magnified stratigraphic layers; see Rossi, “Fra Filippo nell’Adorazione di Camaldoli,” 180-81. |

| ↑70 | Compton, “The Green Places of Fra Filippo Lippi and Sandro Botticelli,” 31-48. For further discussion of green pigments and their uses in fifteenth-century Florence, see Rebekah Compton, “Green Gardens: Venus’ Verdant Virtues,” in Venus and the Arts of Love in Renaissance Florence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 129-56. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108913393.005. |

| ↑71 | Lippi’s Adoration in the Forest altarpiece was likely installed in the chapel by the date of Galeazzo Maria Sforza’s visit to the Medici palace in April 1459, see Beatrice Paolozzi Strozzi, “The Adoration of the Child by the Workshop of Filippo Lippi,” in The Chapel of the Magi: Benozzo Gozzoli’s Frescoes in the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence, ed. Cristina Acidini Luchinat (London: Thames & Hudson, 1993), 29-32. For interpretations of the altarpiece, see Nethersole, Art and Violence, 224-30; Holmes, Fra Filippo Lippi, 172-82; Ruda, Fra Filippo Lippi: Life and Work, 224-30; Solum, Women, Patronage and Salvation, 167-212. For a discussion of the iconography of the frescos of the Medici Chapel Palace, see Allie Terry-Fritsch, Somaesthetic Experience and the Viewer in Medicean Florence. Renaissance Art and Political Persuasion, 1459-1580 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2020), 53-113; Diane Cole Ahl, Benozzo Gozzoli (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996), 96, 105-108; Roger J. Crum, “Roberto Martelli, the Council of Florence, and the Medici Palace Chapel,” Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte 59 (1996): 403-17. |

| ↑72 | The pigments for the Medici Chapel Adoration in the Forest at the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin have not undergone scientific analysis; however, Lippi likely used pigments similar to those found in the Hermitage Adoration of the Child, now in the Uffizi Galleries, Florence; see Rossi, “Fra Filippo nell’Adorazione di Camaldoli,” 178-82. For a discussion of Lippi’s technique and the darkening of copper-based green pigments, see Compton, “The Green Places of Fra Filippo Lippi and Sandro Botticelli,” 38-44. For observations regarding Lippi’s techniques in the Berlin Adoration, see Rose Miller and Christine Patrick, “Four Weeks of Work for Four Seconds of Fame: Reconstructions for Television,” in In Artists’ Footsteps: The Reconstruction of Pigments and Paintings: Studies in honor of Renate Woudhuysen-Keller, ed. Lucy Wrapson, Jenny Rose, Rose Miller, and Spike Bucklow (London: Archetype, 2012), 165-76. |

| ↑73 | Letters to Cosimo de’ Medici discuss Greek tutors, support for young intellects, and funding for the school that Ambrogio Traversari wanted to build for youths at the Monastery of Fontebuono; see, Ambrogio Traversari, Latinae Epistolae, vol. 2 (Bologna: Forni, 1968), book 7, letter 252, p. 329. In 1438, Traversari requests Lorenzo de Medici’s assistance in obtaining two full repositories of transparent Venetian glass for the monastery; see Traversari, Latinae Epistolae, vol. 2, book 7, letter 269, pp. 346-48. |

| ↑74 | Solum, Women, Patronage and Salvation, 167-212. For a discussion of Piero de’ Medici’s artistic patronage, see Francis Ames-Lewis, “Art in the Service of the Family: The Taste and Patronage of Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici,” in Piero de’ Medici, “il Gottoso” (1416-1469), ed. Andreas Beyer and Bruce Bocher (Berlin: Verlag, 1993), 207-20. |

| ↑75 | For letter, see ASF, MAP, f. 85, 136r. Text translation in Solum, Women, Patronage and Salvation, 179-80. |

| ↑76 | For documents and a discussion of the project, see Solum, Women, Patronage and Salvation, 176-77. |

| ↑77 | For a discussion of the rise of landscape specificity in fifteenth-century paintings, see Christopher S. Wood, “Indoor / Outdoor: The Studio around 1500,” in Inventions of the Studio: Renaissance to Romanticism, ed. Mary Pardo and Michael Cole (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 36-72; Luba Freedman, “The Arno Valley Landscape in Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painting,” Viator 44 (2013): 201-42. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.1.103346. |

| ↑78 | For a discussion of the logging process at Camaldoli, see Carlo Urbinati and Alma Piemattei, “La foresta camaldolese: il territorio, la gestione, i prodotti e i servizi,” in Foresta e monaci, 126-45. |

| ↑79 | For a discussion of the cutting of wood, see Urbinati and Piemattei, “La foresta camaldolese,” in Foresta e monaci, 126-45. |

| ↑80 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 155. |

| ↑81 | Belisle, Camaldolese Spirituality, 155. |

| ↑82 | Size and shapes of cut wood are identified regularly in the registries from 1582-1690, see Foresta e monaci, 150-54. |

| ↑83 | Urbinati and Piemattei, “La foresta camaldolese,” in Foresta e monaci, 125, 131. |

| ↑84 | For an account of the loading and transport of wood, see Urbinati and Piemattei, “La foresta camaldolese,” in Foresta e monaci, 131-45. |

| ↑85 | For a discussion of carpentry, wood, and the cross, see Bryda, “The Exuding Wood of the Cross,” 6-36. |

| ↑86 | For a discussion of the depiction and ecological and spiritual signification of stumps, see Bardeen, “Harvest, Rot, Blood,” 51-56. Lippi uses brown iron oxide in the Adoration of the Child in the Uffizi as revealed in FT-IR analysis, see Rossi, “Fra Filippo nell’Adorazione di Camaldoli,” 180. |

| ↑87 | Lippi’s other signature appears on the Maringhi Coronation, where Ruda explains that it is “cut into the stone platform at bottom center.” Ruda argues that the two signatures “imply that the paintings were intended as works of art, and not only as functional icons.” Ruda, Fra Filippo Lippi: Life and Work, 15. |