Mariah Proctor-Tiffany • California State University, Long Beach

Recommended citation: Mariah Proctor-Tiffany, “Finding Badass Women through Medievalism,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/QFGI3903.

Castles, crowns, and gowns–I’m here for the show! Medievalism, or literature, art, drama, or pop culture that plays with medieval themes, absolutely has been the catalyst for my fascination with art of the Middle Ages.[1] Today I am an art historian of Western medieval and Islamic art at California State University, Long Beach. I study real women who collected and gave manuscripts, metalwork, textiles, and other precious objects to bolster their international networks to exercise power in highly patriarchal societies.[2] Additionally, with Tracy Chapman Hamilton, on the website Mappingthemedievalwoman.com, I map foundations, residences, processions, burials, and artistic production of women in late medieval Paris, highlighting their contributions to the cityscape.[3] Medievalism has pushed me to look for all the different ways real medieval women successfully navigated their environments despite palpable misogyny.

My study of the Middle Ages evidently began with a castle–a toy castle. One of my first and favorite early childhood gifts was the Fisher-Price Play Family Castle when I was about three (Fig. 1). I remember playing with the castle and the character figures for hours, raising and lowering the drawbridge over the moat, dropping the little people through the hinged trap door into the dungeon, swinging the staircase open to reveal a secret room, and driving the queen and king around in the horse-drawn chariot. And everyone fought the dragon.

Fig. 1. Fisher-Price “Play Family Castle” (1974). Author’s photo.

Playing with the castle and its figures I narrated the characters’ stories. As a scholar of medieval women now, I wonder how I saw court power structures. I definitely understood that the king and queen were in charge, prince and princess next, and then the knight.[4] I’m sure I imagined women leading battles, making decrees, and running the show. But when did I first learn that women were most often second in command?

Like toys, books were pivotal influences on my interests. When I was about four, I remember my mom reading an illustrated copy of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937) as we sat on the yellow and black, checkered 1970s couch in our living room. I enjoyed the pictures and the slightly scary environments of Bilbo Baggins’s journey. “Precious, precious,” was the line that stuck with me. I understood Gollum obsessively caressing the ring through my own love of my toys, which I carefully handled and guarded.

Growing up in the foothills of Pikes Peak in Colorado, I walked alone a mile to kindergarten, and in my free time I enjoyed the unsupervised run of my neighborhood (despite occasional sightings of bears and mountain lions). I knew to make my way home when the streetlights came on or I heard my mom’s loud whistle. So adventure books felt just right to me.

C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56) captivated me when I was about nine. The idea of Peter, Susan, Lucy, and Edmund, stepping into the wardrobe and ultimately living as king, queen, princess, and prince was intriguing (Fig. 2). As with so much adventure literature, the children were able to move from daily life where they had to do what they were told to an imaginary realm where they could be the “main characters,” make courageous choices, take on responsibilities, fight battles, and emerge triumphant.

Fig. 2. C.S. Lewis, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. Author’s photo.

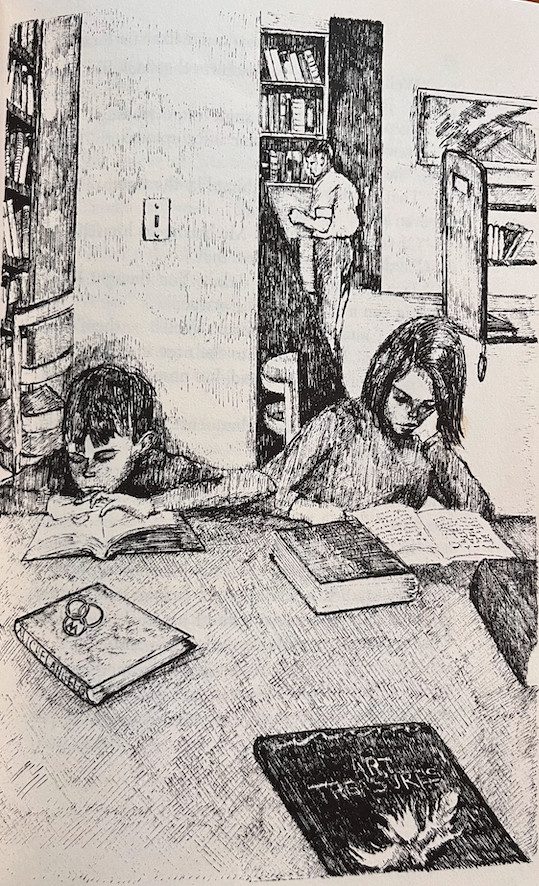

As a pre-teen, I devoured The Chronicles of Prydain by Lloyd Alexander (1964) (Fig. 3).[5] Loosely based on medieval Welsh stories, the series follows Taran, an assistant pig-keeper as he leaves home, confronts evil, and becomes his own confident self.[6] The adventure-bound and increasingly capable protagonist in the series made sense to me as I imagined traveling back in time.[7] I also read and reread From the Mixed up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg (1967), in which siblings Claudia and Jamie run away to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ultimately, they stumble upon a sculpture in the museum whose creator has long been a mystery. Only through their archival research in the donor’s files at the museum can they authenticate it as a Michelangelo (Fig. 4). When I study medieval documents today, I still relish the sense of detective work and discovery Konigsburg describes in her book.

Fig. 3. Lloyd Alexander, The Black Cauldron. Author’s photo.

Fig. 4. Claudia and Jamie studying in the library at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. E.L. Konigsburg, The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, 71. Author’s photo.

By high school in the late 1980s, adventure books had prepared me for a world where women could do anything. Want to be a surgeon? Like, totally! For sure, for sure! Leadership conferences? Absolutely. Want a woman president? Awesome! Why not you?

Also, as a devoted drama kid, I enthusiastically traveled to the Renaissance Festival in Larkspur, Colorado for the costumes, performances, food, and jousting. At the rowdy fair, I wore a purple-flowered chaplet, or flowered crown, which I kept and recently found. Along similar lines, I played Juliet in my public high school’s production of Romeo and Juliet.[8] And my aunt was the publications director of a Shakespearean festival, so we would go almost every summer to watch plays and participate in the costumed festivities. I relished the spectacle of the velvet dresses, the “gem”-laden jewelry, and the stage sets, as well as the interpersonal machinations, desires, and tangling I saw on stage. The intricate psychology of plays like Othello, The Merchant of Venice, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, King Lear, and Much Ado About Nothing raised complicated questions about humanity and exposed me to historic court and mercantile cultures, adding depth to my earlier understanding that began with adventure books and toys. At the same time, these plays helped me put my finger on how women were expected to act and how they were treated when they didn’t conform (in earlier times and often now). I wondered why more women in these plays weren’t the main characters rather than just the collateral damage (Hello, Ophelia, Desdemona, and Cordelia!).

While writing this essay this summer, I nostalgically returned to the Shakespearean festival, and that night The Taming of the Shrew was playing. Now there’s a classic that has passed its sell-by date–a man disciplining his wife (whom he married for the money) into obedience by keeping food and clothing from her?![9] Yes, it’s just a joke!– a humorous play from another time, but the depicted control and coercion remain present in relationship-abuse cases to this day.[10]

As a teenager, given the literary evidence I had at hand, it seemed that historically men were in charge. Yet, I was curious. Certainly there had been agile women who negotiated patriarchal systems successfully. And Lady Macbeth was not the role model I was seeking. Who were these badass medieval women, and how had they found ways to thrive and even rule?

Fig. 5. Katherine Hepburn as Eleanor of Aquitaine in the 1968 film “A Lion in Winter.” Wikimedia Commons.

Eleanor of Aquitaine (ca. 1122-1204) was one answer. I wish I could say that it was Katharine Hepburn’s electrifying performance in A Lion in Winter (1968) that hooked me (Fig. 5). I only returned to that later. Rather, I remember soaking up Marion Meade’s biography, Eleanor of Aquitaine (1977).[11] I was impressed with Eleanor’s spunk, wit, and ambition. In 1137, she brought her expansive and lush domain of Aquitaine to the French crown as she married Louis VII and became queen of France, but the mismatched pair—monklike Louis and fiery Eleanor—after fifteen years of marriage and only two daughters(!), finally secured a divorce from the pope. Within two months, Eleanor brought Aquitaine with her as she married Henry, Duke of Normandy, who shortly became king of England, and they had five sons and three daughters. In 1173 Eleanor supported her sons in a revolt against Henry, then as a result suffered almost sixteen years in prison. But when her son Richard the Lionheart ascended to the throne, she emerged triumphant, ruling in Richard’s stead when he was away. Queen! Eleanor’s story captivated me, an ambitious young woman with Sinéad O’Connor, Depeche Mode, The Cure, Kate Bush, and R.E.M playing on a mixtape on my yellow Walkman.

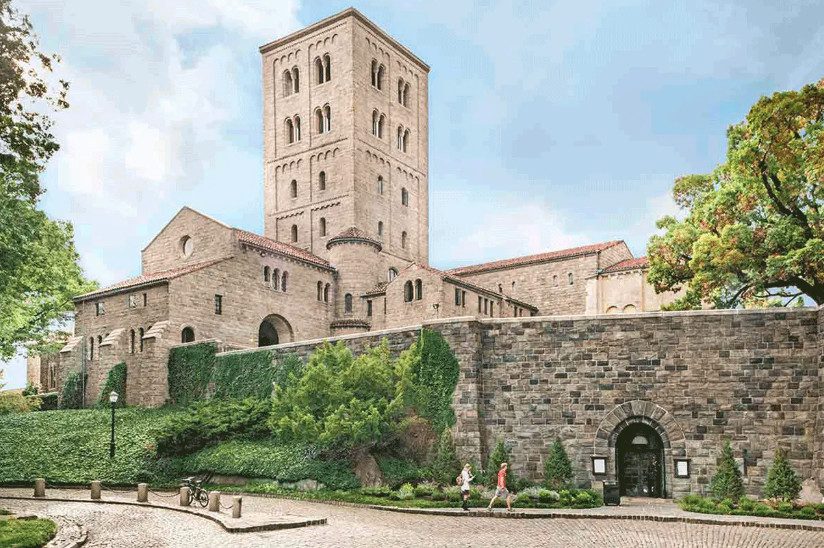

After doing my BA and MA in art history, then teaching art history at a community college and a high school for a year, I moved to New York City and worked at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Only after I had been there a while did I remember the connection to The Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, but perhaps that book played a subliminal part in my ambition to work there. Then I landed my dream job as a museum educator at The Met Cloisters–the mothership of American medievalism (Fig. 6). I led tours, coordinated the scholarly lecture series, gave thematic talks, and trained and was the liaison to the volunteer corps that did the K-12 visits.[12] Working at the museum appealed to me for many of the same reasons so many New Yorkers and visitors from around the world love it: top-tier academic study of exceptional works of medieval art, parts of actual medieval cloisters, chapels, and a chapter house, combined with a touch of the fantasy of traveling back to the Middle Ages, all with a pristine view of the Hudson River. And the gardens, with their medieval medicinal plants, rendered the Middle Ages olfactorily present for me.

Fig. 6. The Met Cloisters. Metmuseum.org.

Dressing up was definitely not an everyday practice there since the emphasis was on academic art history rather than on historical recreation, but one of my favorite “medievalish” memories at The Cloisters was a special family program my colleagues and I did where we rented courtly robes from a New York City theater costume house and dressed up for the tours we gave. We helped the kids make pilgrims’ scrips (travel purses), we served “medieval” food, and we explored the art and architecture.

The Unicorn Tapestries (1495-1505) were some of my favorite works of art to share with visitors (Fig. 7). The dyeing and weaving techniques, the accurately rendered plants, the depictions of a medieval hunt, and the magical unicorn were always a hit. The period room within the medievalizing museum created an evocative space that enabled one to imagine what the tapestries might have looked like in their original medieval environment. Medieval women in the tapestries embodied familiar archetypes: the elegant maid in whose lap the unicorn lays his head, her conniving handmaid signaling to the waiting hunters, and the courtly lady watching the slain unicorn paraded on the back of a horse.

Fig. 7. “The Unicorn Surrenders to a Maiden,” The Unicorn Tapestries (ca. 1495-1505). French cartoon, Netherlandish weaving. Wool warp with wool, silk, silver, and gilt wefts. The Cloisters Collection, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1938 (1938.51.2) Metmuseum.org.

These images of medieval women at The Cloisters, along with numerous images of the Virgin Mary, were quintessential stereotypes. But the real rockstars of The Cloisters, in my humble opinion, were the depictions of martyred Christian women populating the museum. The saints’ lives featured in the book the Golden Legend, a compilation of stories by Jacobus de Voragine (1259-66). According to this text and the art that depicted them, the women were proud and often aggressive as they marched toward their violent deaths. According to her legend, According to her legend, Saint Catherine refused to marry the Roman emperor Maxentius, who then imprisoned for her Christian faith. She triumphed in debates with numerous scholars and then her enemies built a machine with “four wheels studded with iron saws and sharp-pointed nails, . . . But the holy virgin prayed the Lord to destroy the machine for the glory of his name . . . and instantly an angel of the Lord struck that engine such a blow that it was shattered and four thousand pagans were killed.”[13] Even though she later perished, she triumphed. I do wonder about the divergence in reception of Catherine’s story in the Middle Ages. When de Voragine and other men celebrated her and other women martyrs’s violent deaths, were they fetishizing violence against women? I see these saints’ stories differently when women were honoring them, perhaps identifying with these martyrs’ suffering.

I easily imagine this with Saint Margaret, whose legend describes her bursting from a dragon’s belly–thereby making her a patron saint of medieval women in childbirth (Fig. 8). “Margaret was taken down and put back in jail, . . and a hideous dragon appeared, but when the beast came at her to devour her, . . . the dragon opened its maw over her head, put out its tongue under her feet, and swallowed her in one gulp. But when it was trying to digest her, she shielded herself with the sign of the cross, . . . and the dragon burst open and the virgin emerged unscathed . . .”[14] Especially during this period of extremely high maternal mortality, such a saint might reassure women when they faced the strong possibility of death as they headed into childbirth.

Fig. 8. Saint Margaret. Workshop of Michael Pacher, Austrian or German, ca. 1470-80. Pine with metal appliqués, traces of gesso and paint. 50 3/4 × 31 × 13 1/2 in. (128.9 × 78.7 × 34.3 cm). The Cloisters Collection, 1963 (63.13.2) Metmuseum.org.

Medieval artists depicted a martyr’s embrace of death as an act of agency and power. Their popularity in the Middle Ages meant to me that while images of the Virgin Mary reigned, and those of graceful maids of courtly love abounded, women who took their destinies in their own hands also stood as icons of womanhood. It was while I was surrounded by these images of powerful women in the medievalizing environment of The Cloisters that I wrote my doctoral program applications about women and agency in the production, reception, and circulation of medieval art.

Medievalism encouraged me to seek the many ways real medieval women successfully carved a path for their lives within their societies despite blatant misogyny. I love a gauzy nineteenth-century Edward Burne-Jones medievalizing enchantress like that of Nimue in The Beguiling of Merlin, but so many of these phantasms were painted or written by men. The actual medieval women I found through graduate and post-graduate research were so much more practical, raw, resourceful, and powerful (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. Edward Burne-Jones, The Beguiling of Merlin (c. 1872–1877). Oil on canvas. 186 × 111 cm (73 × 44 in). Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, Merseyside, England. Wikimedia Commons.

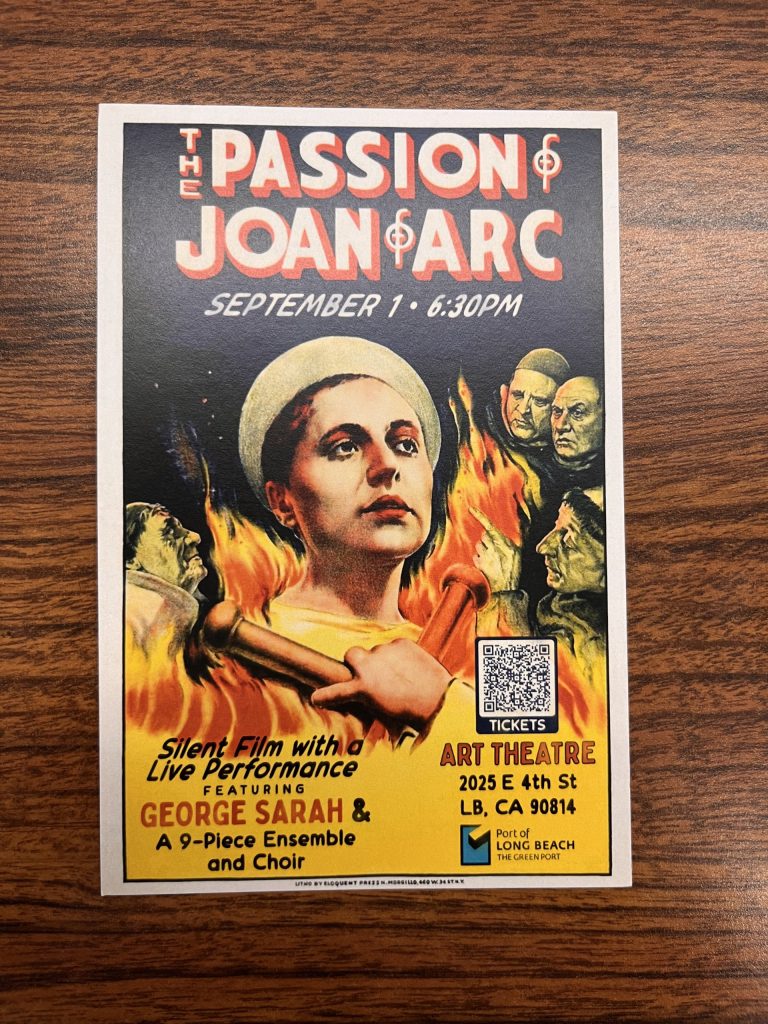

Some of my many favorites include the Byzantine Empress Theodora (ca. 497-548), supposedly the daughter of a bearkeeper at the Hippodrome in Constantinople. She was a sex worker, overcame the social stigma, ascended to the throne of Byzantium, and ultimately became the most powerful woman in Byzantine history.[15] Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179) was an abbess, philosopher, composer, writer, botanist, visionary, and mystic. Christine de Pizan (1364-1431) made a living as a professional writer advising her royal clientele on their behavior. Joan of Arc (ca. 1412-31) was jailed even though she had rallied the troops in support of the future King Charles VII, saving France from the English. They ultimately burned her at the stake as a heretic, largely for refusing to dress like a woman. Today, a trans icon, Joan continues to inspire art and action (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Postcard for a packed showing of The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), starring Maria Falconetti, directed by Carl Theodor Dreyer. Art Theater, Long Beach, California, Sept. 1, 2024, with a live performance of George Sarah’s original score composed for the silent film. Author’s photo.

I found that some women did indeed wield power like the characters of the modern, medievalizing Game of Thrones TV show (2011-19). I think of Countess Mahaut d’Artois (1269-1329) in fourteenth-century Paris. She was a wealthy and well-networked ruler of the counties of Artois and Bourgogne, and she successfully shut down her nephew’s claims to her land. But when her daughter became queen after the deaths of King Louis X and his baby son Jean in 1316, her enemies accused her of witchcraft and of poisoning the kings. Mahaut’s trial transcript shows that Clémence de Hongrie (Louis’s widow and Jean’s mother) testified in Mahaut’s defense. Even the powerful Game of Thrones character Cersei Lannister couldn’t escape a walk of shame, but Mahaut d’Artois did. She was acquitted on October 9, 1317.[16] How many women can you name who walked away from a witchcraft trial? Mahaut was a woman who knew how to thrive within a patriarchy. Badass, total badass.

Medieval Muslim and Jewish women intrigue me as well, as they used their intellects and resources at hand to carve out their distinct places in their societies. A fourteenth-century source attributes the foundation of the al-Qarawiyyin Mosque in 857-59 in Fez, Morocco to a woman named Fatima bint Muhammad al-Fihriya al-Quarashiyya. This African mosque eventually became the first university, predating those in Europe. And in the Ottoman Empire based in Istanbul, critics of Hürrem Sultan (ca. 1505-1558), the foreign-born wife of Sultan Süleyman called her a witch. (So many witches in history!) It made them uncomfortable that, breaking with custom, she rose to become Süleyman’s legal wife, bore more than one son, and remained with Süleyman in the capital “meddling” in politics. To build goodwill, Hürrem actively performed the fundamental Islamic practice of charity. She commissioned numerous mosques and hospices in Istanbul, Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem, and over a period of years, she gained respect through her generous behavior.[17] For example, the Hürrem Sultan complex in Istanbul featured a mosque, schools, a hospice, and a hospital (1538-51). And the Jewish women depicted reading, teaching, and debating in the fifteenth-century German Darmstadt Pessach Haggadah (Darmstadt, Technical University of Darmstadt, Cod. Or. 8, fol. 48v.) demonstrate that for some medieval women, respect and power could come through intellectualism, teaching, and debate.[18]

Women of great means or scholarly training were not the only ones to successfully negotiate their way through misogynistic landscapes. As Tracy Chapman Hamilton and I are documenting geographically, women of lesser means but high skill worked both inside and outside the home. Parisian tax records from 1292 to 1313 list numerous women running businesses as artists and makers: carpenters, smiths, painters, manuscript makers, metalworkers, sculptors, and textile workers.[19]

I’ve found that women’s strength appears not only in lording power over others but in simply leading the lives they desired. Take for example the beguines, members of the religious order in medieval Europe in which women kept their property, could leave and marry if they chose, and sometimes even made excellent money working and investing in the silk trade in medieval Paris–unlike other orders that mandated forfeiting assets and vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.[20] Some beguines lived in the béguinage, but many resided with other women in homes throughout the city, exhibiting uncloistered freedom that made the authorities uncomfortable. One such beguine, Jeanne du Faut, established a thriving silk production business. In her 1330 testament, she bequeathed the bulk of her properties and large estate to Beatrice la Grande, her “agent and receiver” (probably of silk)–in spite of the fact that Jeanne had family who might have had a legitimate claim to her property. When Jeanne’s testament was executed in 1334, she endowed masses to be sung for her and her “beloved”–Beatrice.[21]

And in the tax records, several beguines (and other women) were taxed with a “companion,” for example, “Yfame, la beguine, et Emeline, sa compaingne.”[22] Yes, these companions might have been assistants, but the descriptions of pairs of women living together certainly leave open the possibility that they were lesbians who had found a way to live together, as many “roommates” have over the centuries. This is what these relationships would have looked like in tax records. One way or another, the beguines lived the spiritual lives they desired, sought edification, served in the community, built financial strength, and lived on their own terms–independent of fathers, husbands, uncles, or brothers–effectively sidestepping the omnipresent patriarchy.

Medievalizing art, literature, and drama frequently focus on women and others overcoming lowly circumstances or structural oppression. What is it about the Middle Ages that makes it such fertile ground for people today to fantasize about overcoming steep odds for success? Perhaps this is in part because social structures were often so legally and visibly codified in the Middle Ages. In France for example, unlike other countries, the Salic law literally dictated that men, not women, ruled. Moreover, the elite of Europe legally controlled dress and adornment through sumptuary laws, particularly in France and Italy, in principle, making people’s roles and stations instantly visually identifiable. For example, in 1294 French king Philippe le Bel decreed that only the royalty could wear fancy furs, gemstones, and crowns, “ . . . no bourgeois man or woman will wear vair, or gris, or ermine, and will forfeit that which they have by next Easter. They will not wear precious stones, nor crowns of gold or silver.[23] In other words, “all you wealthy social climbers, fork over your furs, gems, and crowns by Easter–or we’re coming for them.” So in a medievalizing story today about someone of lowly birth overcoming those structures, when she appears at the end wearing that red velvet gown and a gold crown studded in rubies, emeralds, and pearls, she splendidly bursts through the structural limitations of her culture; today’s glass ceiling was a wood ceiling in the Middle Ages, making exploding through it all the more visibly triumphant in medievalizing art, literature, and pop culture.

Studying and playing with medieval culture and history today enable us to visualize hierarchies, to name what we see there, and to challenge and reject power structures that minimize worthy aims and abilities. Perhaps medievalism is a way to point out inequities through riveting scenes long ago and far away; what seems obviously ridiculous in a medievalizing story can help us recognize and challenge equally ludicrous injustices today. For me, medievalism and the Middle Ages serve as arenas in which we can think through social norms, gender, race, power structures, and material culture.

I see the defining questions of my scholarship emerging from my cacophonous years of striving toward a better future while negotiating inherited social and cultural structures. I am delighted that many of the contributors to this issue of Different Visions see medievalism as a fantasy playground for creative expression. As a young woman, medievalism was not only my imaginative, magical world but also a site of inquiry for me. How did medieval women negotiate treacherous patriarchal landscapes? In my scholarship, I’ve been on the hunt for these women and the variety of ways they used art, costume, ritual, generosity, and drama to meet their political and personal goals. And these badass women were there throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East. Yes, the structures of patriarchy were and are real; and yes, women found and will always find a way.

References

| ↑1 | In talking about medievalism here, I refer to work that draws on history, culture, and art of the so-called long Middle Ages (about 800 to 1600), so Shakespeare and Renaissance fairs count! Many of the themes of early modern literature and art, especially related to court culture, manuscripts, clothing, metalwork and design, are deeply rooted in their medieval antecedents, and these continue to engage with themes of gender, race, otherness, and material culture as they did in the high Middle Ages. I am grateful to Catha Paquette, Kaarina Cleverley Roberto, and my co-editors Larisa Grollemond and Bryan Keane, as well as the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions on this essay. I thank my mom, Mauna Proctor, who introduced me to so much literature and art. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mariah Proctor-Tiffany, Medieval Art in Motion: The Inventory and Gift Giving of Queen Clémence de Hongrie (University Park: Pennsylvania State University, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271083056. |

| ↑3 | Mappingthemedievalwoman.com; Tracy Chapman Hamilton and Mariah Proctor-Tiffany, “Inscribing Her Presence: Digital Mapping and Women in Late Medieval Paris” in Medieval People: Social Bonds, Kinship, and Networks (2022) Vol. 37: Iss. 1, Article 3. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/medpros/vol37/iss1/3. https://doi.org/10.32773/WAON8251. |

| ↑4 | Disney’s versions of Snow White (1937), Cinderella (1950), Sleeping Beauty (1959), and other fairy tales aired on TV frequently. While I don’t remember Disney’s films being key for me, they and the traditional Grimms’ fairy tales were definitely in the air and on the bookshelf and must have subtly influenced my worldview about how people interacted in the stratified world of material splendor “once upon a time.” |

| ↑5 | David Roberts, “The Chronicles of Prydain is the greatest fantasy series ever written.” Vox Nov. 3, 2017 https://www.vox.com/2015/8/18/9166631/chronicles-prydain-alexander. |

| ↑6 | The 1985 Disney film “Black Cauldron” did little to capture the magic of the original books for me. |

| ↑7 | Speaking of time travel, even if not to the Middle Ages, I must have been about ten when I tore through Edward Ormondroyd’s book Time at the Top (1963). It’s a story about Susan and Victoria, girls who travel to the past through a magical elevator in an apartment building. Although the characters were only going back to the nineteenth century, the idea of time travel and tripping out about questions of how changing events in the past could alter the future really made me think. I read this in the early 80s before the famous Back to the Future movies began in 1985, so for me, time travel was a new concept to puzzle through, and I’m sure it played a part in my interest in the past. |

| ↑8 | My mom, a 4-H Club award-winning seamstress, made many of my costumes, and I’m sure my interest in medieval costume and textiles began at her feet as I sat while she sewed at her machine. |

| ↑9 | I also have this horrified reaction when I hear the stalker anthem, “Every Breath You Take” by the Police. How is this possibly still playing?!?! Forgive me, dear reader–I digress. |

| ↑10 | Engaging with these plays also pushed me to grapple with the antisemitism and racism I saw there. I wrote a high school English paper about The Merchant of Venice. While Shakespeare’s vilification of Shylock played on antisemitic tropes, I appreciated Shylock’s plea that anyone who has felt the stab of discrimination might feel, “Hath not a Jew eyes, Hath not a Jew hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? . . . If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? . . . ” William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, ed. G. B. Harrison (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1952) 3.1.61-69. (Here I’m citing my mom’s student copy, with her notes in the margins.) And in Othello, I remember seeing a man who was a respected outsider, one who had “made it,” and yet Iago used racist tropes to whip up Othello’s jealousy and broader resistance to Desdemona’s and Othello’s interracial marriage. Iago taunted Desdemona’s father, saying that, “An old black ram is tupping your white ewe.” Shakespeare, Othello, 1.1.88-89. |

| ↑11 | Marion Meade, Eleanor of Aquitaine, A Biography (New York, Hawthorn Books, 1977). |

| ↑12 | It was also at The Cloisters that I made many medievalist friends, one of whom is Martha Easton, another contributor to this issue. |

| ↑13 | Metmuseum.org (37.52.4); Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, trans. William Granger Ryan (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), 2:172. |

| ↑14 | de Voragine, Golden Legend, I:369; Metmuseum.org (63.13.2). |

| ↑15 | Roland Betancourt, “Slut-shaming an Empress” in Byzantine Intersectionality: Sexuality, Gender, and Race in the Middle Ages (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2020), 59-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-30392-9; Theresa Earenfight Queenship in Medieval Europe (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 47-52. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-30392-9. |

| ↑16 | Jules-Marie Richard, Mahaut Comtesse d’Artois et de Bourgogne (Paris: H. Champion, 1887), 21-22, 41-42. Due to these accusations, the French writer Maurice Druon cast Mahaut as the murderous villain in his book series Les rois maudits (1955-77), which became an acclaimed medievalizing French mini-series (1972-73) with a reboot in 2005. Druon’s series, in turn, was important in George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire (1996-2011) which, in turn, served as a starting point for The Game of Thrones TV series (2011-19). See also Theresa Earenfight’s Queenship in Medieval Europe for many other women who exercised political power in the Middle Ages. |

| ↑17 | Gülru Necipoğlu, “Queens: Wives and Mothers of Sultans” in The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 268-292. See also the Turkish TV series The Magnificent Century (2011-14). |

| ↑18 | Darmstadt Pessach Haggadah. I look forward to reading the thesis that CSULB art history graduate student Isabel Cline is writing on this manuscript. |

| ↑19 | With Tracy Chapman Hamilton, Mappingthemedievalwoman.com. We thank research assistants Isabel Cline and Eve Clayton for their many contributions to the project. Sharon Farmer too shines scholarly light on innovative women migrants in late medieval Paris. Sharon Farmer, The Silk Industries of Medieval Paris: Artisanal Migration, Technological Innovation, and Gendered Experience (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017). See also on women and labor, Janice Marie Archer, “Working Women in Thirteenth-Century Paris” (PhD diss., University of Arizona, 1995); Shelley E. Roff, “Appropriate to her Sex”? Women’s Participation on the Construction Site in Medieval and Early Modern Europe” in Women and Wealth in Late Medieval Europe, ed. Theresa Earenfight (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 109-134. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230106017_7. |

| ↑20 | Tanya Stabler Miller The Beguines of Medieval Paris: Gender, Patronage, and Spiritual Authority (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). |

| ↑21 | Miller, 77-78. |

| ↑22 | “Jehanne, la broderesse;–Martine, sa compaaingne, 20 sous” H. Géraud, ed. Paris sous Philippe-le-Bel: d’après des documents originaux, et notamment d’après un manuscrit contenant le rôle de la taille imposée sur les habitants de Paris en 1292. (Paris: L’Imprimerie de Crapelet, 1837), 159. |

| ↑23 | Author’s translation. “Nul Bourgois, ne Bourgoise ne portera vair, ne gris, ne Ermines, & se delivreront de ceux que ils ont, de Pâques prochaines en un an. Il ne porteront, ne pourront porter Or, ne pierres precieuses, ne couronnes d’Or, ne d’Argent.” Laurière, Eusèbe. “Ordonnances des Roys de France de la Troisieme Race, Recueillies par Ordre Chronologique.” (Paris: Imprimerie royale, 1723), 541. Similar laws were issued time and again, demonstrating that people were pushing back and wearing forbidden finery. |