Suzanne Lewis • Stanford University[1]

Recommended citation: Suzanne Lewis, “Encounters with Monsters at the End of Time: Some Early Medieval Visualizations of Apocalyptic Eschatology,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 2 (2010). https://doi.org/10.61302/FSQU1802.

In our long history of interpreting apocalyptic images in medieval manuscripts, we have tended to resist the idea of eschatological expectation as a major creative force.[2] Now that we have passed the end of our second millennium only to confront dire threats to the fate of our planet, there seems to be a particular urgency in revisiting some medieval sites of pictorial representation with a view to re-examining how they opened visual discourses relating to the end of time.

Although the Book of Revelation promises the coming of the messianic kingdom in the Heavenly Jerusalem, Saint John’s meta-narrative leaves his reader on what has been called “the edge of chaos . . . the point . . . where the components of a system never quite lock into place.”[3] At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we are still there—waiting. Albeit living in a drastically changed world context, we can still comprehend, if not share, the medieval experience of what Catherine Keller aptly characterizes as a “marginal spirituality of unresolvable complexity itself.”

Following the description of the future celestial Jerusalem, Saint John is commanded “not to keep secret the prophecies in this book because the time is close. Meanwhile let the sinner go on sinning, and the unclean continue to be unclean” (Rev. 22:10-11). Not unlike our medieval predecessors, we find ourselves drawn, not to the promise of a remote heavenly bliss, but to an immediate evil that defies narrative closure, the kind of malign cosmic power that can destroy humanity and shatter the world.[4] As Keller reminds us, “Apocalypse does not mean annihilation, but revelation.” Yet the narrative of disclosure (unveiling) has been conceptually transformed into the ideological power

with which to face and [to] justify annihilation. The mythic dramatization of the final confrontation of good and evil, with the destruction of most life on the planet as ‘collateral damage,’ may constrain, or may inspire, human agents of world extermination.[5]

Keller concludes by suggesting that perhaps what renders the evil that

emanates from the pandemonium of the Apocalypse so interesting . . . [is] our unintegrated need for complexity: for the states of heightened, unsettling contrast.[6]

Thus poised on the trembling thread linking death and desire, the reader- viewer of the medieval Apocalypse encounters many incarnations of evil—a stunning array of monsters—Antichrist, the seven-headed Dragon, the Beast from the Abyss, the Beasts that emerge from the earth and sea, as well as the devouring jaws of the beast that is Hell itself. At the extreme ends of time and the edges of space beyond Christendom, monsters mark the outer thresholds.[7] The monster constitutes a subversive ontological liminality that may in part explain our disturbing reactions of repulsion and attraction. As Jeffrey Cohen argues,

The monster lives at the slippery, indefinable edge . . . his very existence obliterates all perceptible lines of boundary and enclosure, thus offering an imperiling expansion of human cognition that breaks with order and rationality and logic.[8]

As they are drawn from the narrative structure of the Apocalypse text, that is, from a series of epic struggles between the forces of good and evil, visual configurations repeatedly converge in confrontations between God’s people on earth and monstrous embodiments of the Devil, Satan, and Antichrist. Whereas the faithful remain human and unchanged throughout both the text and its visual representations, images of monstrosity are never fixed or physically defined.

Indeed, the most terrifying aspect of Satan’s appearance or disappearance is that they function as shifting metaphors. In his various roles, his visible identity is discontinuous, and hence unknowable. As Luther Link puts it, “the Devil is not a person. He may have many masks, but his essence is a mask without a face.”[9] For our contemporary psyche, it is tantamount to staring into the face of Charles Manson and experiencing the horror of confronting absolute depravity. In his presence, real or imagined, we feel soiled and corrupted.

Within the context of the recent theoretical repositioning of our notions of monstrosity, the Devil, Satan and Antichrist are not empty signifiers but images heavy with multiple meanings. In order to understand the cultural paradigm (of Foucauldian episteme) that shaped medieval representations of monsters, we must first turn to the foundational definition formulated by Saint Augustine, based on the etymology of monstrare (to show).

Monsters, in fact, are so called as [portents], because they explain something of meaning or because they make known [immediately] what is to become visible.[10]

Here, the definition of monster inevitably depends upon its epistemological function.[11] The Augustinian idea that there is some kind of reality beyond the sign’s signification outside language, rhetoric, and logic forms the basis of the medieval concept of metalanguage in visual and verbal constructions of paradox, ambiguity, and monstrosity, “which sufficiently deform the normal process of signification so as to urge the mind beyond . . . language and logic.”[12] In the twelfth-century negative theology of the Pseudo-Dionysius, following upon the incarnational character of Saint Augustine’s sign theory, the Christian concept of God-man is seen in the figure of Christ, who resolved within himself the “monstrous paradox of his own double nature, man and God, carnal body and spirit.”[13] Most important for our present concerns is the notion that “paradox, by its very nature, refuses closure,” and opens the mind to the limitless receptivity of Being found in God.[14]

At the centre of the subversive discourse of monstrosity is the microcosm of the human body made in God’s image but whose earthly integrity is under constant threat of distortion and perversion by diabolical powers. Throughout the Middle Ages, deformity and ugliness were believed to be outward visible signs of inner moral corruption; by the same token, hybrid creatures embodied a bestial perversion beyond nature.[15] Whereas monsters and demons may have been endowed with a palpable, if not always visible, ‘reality,’ within the ontological framework of medieval belief,[16] from the postmodern perspective of Jeffrey Cohen,

The monstrous body is pure culture . . . a construct [that] exists only to be read . . . the monster signifies something other than itself. And so the monster’s body is both corporeal and incorporeal: its threat is its propensity to shift.[17]

In exploring the violence enacted by these debasing representations, René Girard observed that “monsters are never created ex nihilio, but through a process of fragmentation and recombination,” in which elements are extracted from various rejected forms and categories “and then reassembled as the monster, which can then claim an independent entity.”[18] Since, as Cohen points out, the monster is the incarnation of radical difference, the kinds of otherness inscribed upon the monstrous body tend to be cultural, political, racial, and sexual.[19] As we shall see, the pictorial code of rejection that was operative over several centuries of the Middle Ages was not fixed or monolithic, but demonstrably “free-floating and mutable—flexible and adaptable to changing ideological interests.”[20]

Medieval apocalypticism was a state of mind premised on the belief that human history is structured according to a divinely predetermined pattern culminating in the Last Judgment. Contrary to many popular assumptions, anxiety concerning the coming end was not pervasive at all levels of society. Apocalyptic writings and images were created by and for elite readers and viewers within both the religious and secular spheres of cultural power. In contrast to the problematic determination of audiences for the medieval bestiaries, the social contexts in which most apocalyptic manuscripts were made and experienced can be convincingly documented. As we shall see, from the ninth to the end of the twelfth century, illustrated Latin Apocalypses were produced almost exclusively for monastic or clerical consumption. For the Middle Ages, apocalypse expectation generated what Bernard McGinn has called “psychological imminence, in which life is lived under the shadow of the end.”[21] Within the context of this dark cloud of vague urgency, the medieval conviction that the final drama was already underway had a profound effect upon the shaping of apocalyptic imagery for seven medieval centuries and beyond.

We shall begin by considering some of the earliest visual configurations of a prophesied end in the Carolingian Apocalypses of the early ninth century. Then we shall turn to some uniquely inventive twelfth-century formulations in the Liber Floridus. In revisiting these sites, we shall explore the fundamentally semiotic character of apocalyptic expectations of the end, as they are embodied in the figure of Antichrist, who will be known by his multiple and changing signs.[22] At the same time that the working out of a divine plan remains consciously and pointedly unclear, inexplicable and unknowable, a wide range of apocalyptic commentaries and exegetically driven images reveal an ardent medieval desire to grasp and even manipulate the unexplained and incomprehensible coming of the end.

Carolingian Apocalypses

Throughout the Middle Ages, manuscript images of apocalyptic visions are often projected on an empty vellum screen as if seen from a divine perspective— distant and elevated. That is, events are represented as they appear to God. At the ideological core of the medieval Apocalypse is the belief that time is merely an illusion—hence the simultaneous visual perception of heaven and earth, in an ontological blurring of past, present, and future (see Figure 4).[23] Until the twelfth century, the Apocalypse was only rarely understood in eschatological terms as a revelation about the end of time. Instead, it was interpreted as an allegory of the Church between the first and second advents of Christ.[24] As Yves Christe argues, the great visions of the glory of God were perceived as present eschatological reality.[25] Notwithstanding the dominance of what McGinn has called the “vertical” reading of the Apocalypse as a revelation of the timeless secrets of heaven and the universe,[26] the perception of a “horizontal” uncovering of the meaning of history and its end can be seen as a critical subtext of medieval manuscript illustration as early as the Carolingian period.[27] I would argue, however, that the temporal dimensions of the text-image discourses in the ninth- century Trier and Valenciennes Apocalypses emerge most clearly when we ask: What is absent? What is missing? What has been suppressed?

If ideology can be defined in simple positive terms as “whatever is known or believed,” it can also be cast in its negative counterpart as “what is left unsaid.” In his reworking of postmodern formulations of ideology as a set of discursive practices, Fredric Jameson explores the rhetorical strategies of constraint as repressing the unthinkable:

The graphic embodiment of ideological closure . . . allows us to map out the inner limits of a given ideological formation . . . [It] now affords a way into the text . . . through its diagnostic revelation of terms or nodal points implicit in the ideological system which have, however, remained unrealized in the surface of the text . . . and which we can therefore read as what the text represses . . . So the literary structure . . . tilts powerfully into the underside or impensé or non-dit.[28]

As Derrida argued, however, the power of erasure can be sustained only by remaining legible; the trace of what is invisible or absent must be established by a hinge (brisure).[29] The brisure in this case is provided by the monastic reader’s prodigious memory of scriptural texts. These relations can be explicit as well as surreptitious—“they can operate at the level of a single text, or only through an accretion of similar textual strategies throughout the culture.”[30] With this in mind, we can find a striking omission of the image as well as the text for the Sixth Seal in both the Trier and Valenciennes Apocalypses.[31] For most medieval commentators, the opening of the Sixth Seal signified the coming of Antichrist and his persecution of the Church as harbingers of the end.[32] From the ninth to the early eleventh century, it was also held that

Antichrist would not come into the world . . . unless all the kingdoms that long ago were subject to the Roman Empire secede from it . . . As long as the kings of the Franks, who possess the Roman Empire by right, survive, the dignity of the Roman Empire will not perish altogether, because it will endure in the Frankish kings.[33]

The avoidance of picturing the Sixth Seal literally “glossed over” a major apocalyptic event, which continued to be perceived as potentially dangerous by the designers of the Bamberg Apocalypse made around 1001-1002 for the German Emperor Otto III.[34] The singular and apparently deliberate omission constitutes a tacit recognition of the implications of the symbiotic relationship between Church and Empire sustained from the time of Charlemagne beyond the passing of the first millennium. Just as early eleventh-century chronicles could selectively ‘forget’ the past in an effort to mitigate the effects of violent ruptures that could undermine ideas of stabilizing continuity,[35] the omission of a powerful apocalyptic image can be seen as capable of suppressing the potentially disruptive forces of future prophecy. By reinforcing the long-standing ideological role of the Empire in the eschatological drama of apocalyptic prophecy, Antichrist could be kept away.[36] For a writer of the millennial generation such as Adémar of Chabannes, eschatological concern for imperial continuity persists in his account of Otto III’s startling discover on Pentecost in the year 1000 of Charlemagne’s tomb at Aachen in which the long-dead emperor was still seated on a throne.[37]

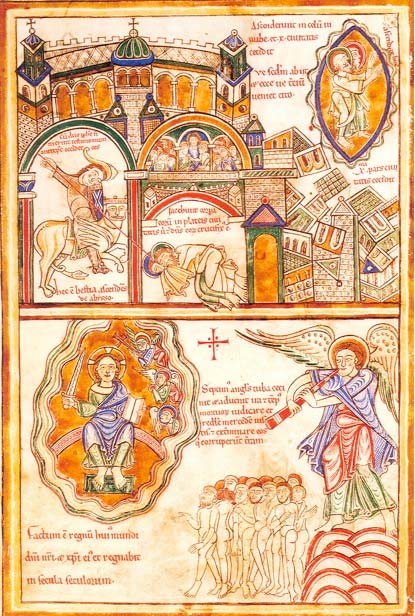

A similar strategy of denial to stave off the end of time occurs in Valenciennes’ striking omission of the Beast who emerges from the abyss to attack the Witnesses in Revelation 11 (Figure 1).[38] The absence of the bestial agent of death who murders God’s prophets renders the image almost indecipherable as an illustration of the text. Nevertheless, his monstrosity becomes a powerful but unseen presence—unspeakable and unimaginable. By rendering the Beast invisible, however, the designer has succeeded in suppressing the threatening presence of Antichrist with whom it had been identified by exegetes such as the widely influential Haimo of Auxerre and Ambrosius Autpertus.[39] One of the most popular and widespread legends attached to the Antichrist tradition promoted the belief that Enoch and Elias will come in the last days to preach against him.[40] In the Valenciennes Apocalypse, the two Witnesses stand at an impasse with the violence signalled in the first part of the inscription (Bestia qui ascendit de abysso faciet adversos illus bellum et occident). In contrast to the silent emptiness of the rectangle below, the crucified Christ evoked in the titulus appears at the upper right (et dominus eorum crucifixus est). Within the context of what David Williams terms “deformed discourse,” the reader-viewer hears the silence of the text as he sees the absence of image and understands their meaning as what is neither said nor embodied.[41] Nothing is allowed to detract from the triumph of God’s sovereignty over the earth at the sounding of the Seventh Trumpet (Rev. 11:15): “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and his Christ, and he will reign forever and ever.” According to Bede’s influential commentary, the Seventh Angel, “messenger of the eternal Sabbath, makes known the victory and imperium of the true king.”[42] The angel blows his trumpet toward the upper left in a gesture of linkage and closure, as if giving voice to the silent prophecies of the Witnesses who face the reader. In marked contrast to the violent retribution for the death of the Witnesses in the Trier illustration of this text (fol. 35r), the Seventh Trumpet generates an inscribed empty space (septimus angelus tuba cecinet), a metaphorical lacuna intended to evoke “the time [that] has come to destroy those who are destroying the earth.”

Fig. 1. Witnesses and Crucifixion (above); Seventh Trumpet (below), Apocalypse, Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 99, fol. 22r (Photograph: Ville de Valenciennes)

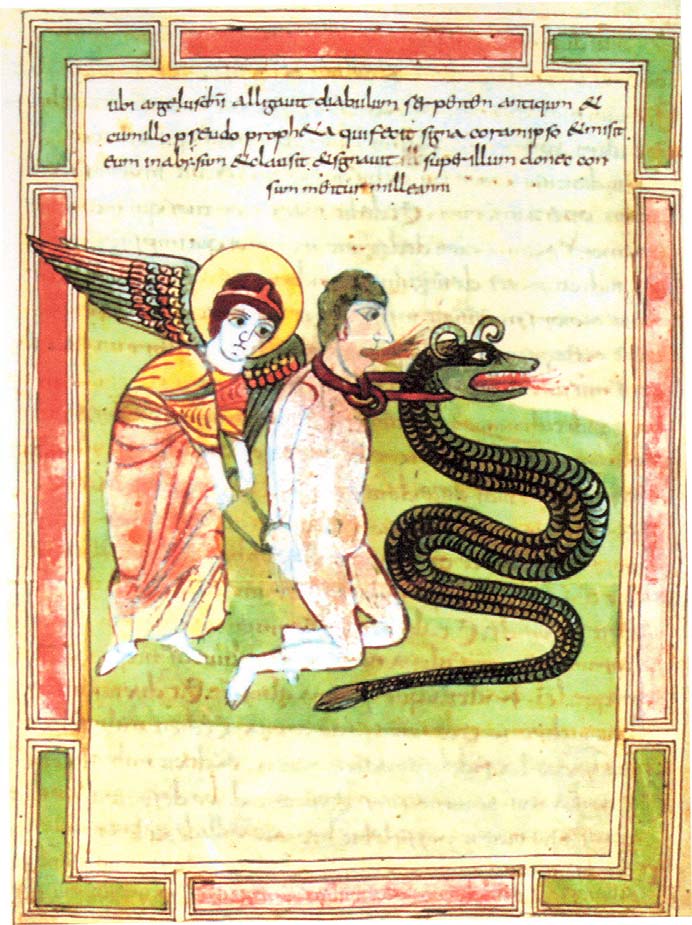

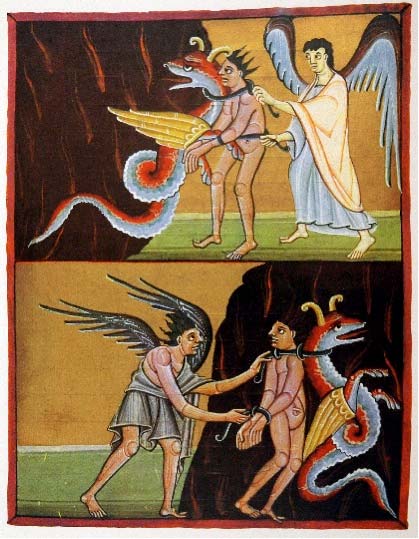

Fig. 2. Angel Enchaining the Beast and False Prophet. Apocalypse, Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 99, fol. 36r (Photograph: Ville de Valenciennes)

Following upon Valenciennes’ insistent and even aggressive suppression of the image and idea of Antichrist, the arch-fiend in Revelation 20 is suddenly thrust before the viewer’s gaze as a naked giant in full-blown human form (Figure 2).[43] If we rely upon the garbled version of the Vulgate text presented in the titulus, the intended identity of the two figures in not as ambivalent as it might seem. Along with the Devil, clearly identified as the “old serpent,” the angel enchains the False Prophet, who has been shifted to this moment from his adjacent Vulgate appearances. The corrupted merger of texts from Revelation 19:20 and 20:1-3 in the Valenciennes titulus creates a radical shift from a single figure (“the ancient dragon [who is] the ancient serpent, who is the devil and Satan”) in the Vulgate, to two distinct characters, “the Devil (diabolus serpentem antiquum)” and “with him the False Prophet (cum illo pseudopropheta).”[44] Clearly, the Valenciennes illustration seems to be engaged in creating its own independent narrative, drawing upon the viewer’s reading of the images and inscriptions as opposed to the biblical text. The problematical but suggestive intrusion of the aberrant text in the inscription could easily have served to divert the monastic reader’s attention in the direction of an absent (but remembered) commentary. In this case, Bede as well as Ambrosius Autpertus equated the False Prophet with Antichrist.[45] Following Augustine, the most quoted authority on Antichrist, early medieval writers from the seventh century on largely rejected the possibility that he would be the Devil incarnate and instead concluded that he will be a “natural man (purus homo), whom the Devil nevertheless will possess.”[46] Notwithstanding Augustine’s anti-millennialist prohibition against applying Revelation 20 to the future, Satan’s agent, Antichrist, was nevertheless necessary to the explanation of salvation history in De civitate Dei.[47]

In this stunning dramatic move, the Valenciennes’ designer introduces a monstrously large naked figure who commands the viewer’s fascinated gaze like a contorted magnet, as he passively echoes the curving outline of the now overshadowed dark coiling serpent at the same time that the angel pulls his arms back. Indeed, somewhat later in the ninth century, Haimo of Auxerre declared that Antichrist is the son of the Devil, “not through nature, but through imitation.”[48] Tethered and pinioned to the green ground behind him, the human monster is seen as an exhibited specimen, demonstrative of something other than itself, as it resonates with the early medieval conception of Antichrist as a giant.[49] In Cohen’s words, the giant has “no life outside of a constitutive cultural gaze, outside of its status as a specular object.”[50] As early as the seventh century, Isidore of Seville perceived that the most obvious and appropriate model for an analytical classification of monsters is the human body.[51] The giant’s deformity in size constitutes an excess that places him outside the realm of natural human proportion, a transgression of natural boundaries.[52] In his gross incarnation, he is a “spiritless mass of moribund matter.”[53] In the Valenciennes figure, more striking than his size is the giant’s nakedness, which by the ninth century had become a familiar pictorial sign of monstrosity and barbarism.[54] As John Friedman reminds us, “the postlapsarian shame of Adam and Eve (Gen. 2:25 and 3:7) passed on to their descendants . . . thus distinguishing them from animals lacking reason and moral inhibition.”[55]

In the Valenciennes illustration, Satan (the Devil) and the False Prophet are being enchained together by an angel, thus merging Revelation 19:20 and 20:10 into a single conflated image and potentially into a single dual-bodied figure, at once human and beast. Locked together in a chain of being that can be visually read as the transgressive metamorphosis of a single entity, the enigmatic identity of the two ‘serpentine’ beings hangs literally on the edge of the abyss. The ground behind the two figures is lightly washed in green, leaving a vacant rectangle below as a spatial metaphor that suggests the transitory status of their consignment to the abyss. They both anxiously turn to the edge of the frame in anticipation of their ultimate fate. In a move consistent with the designer’s desire to assuage or to suppress the reader’s potential eschatological concerns, the singular representation concentrates on Satan-Antichrist’s immobilization by the angel who renders him (them) powerless within the knotted bonds. Swollen and pot-bellied, the naked but still fire-breathing human monster kneels behind the Devil in a captive state of abjection.

Following Bede’s assertion that many Antichrists were already at work, eschatology became a major concern when, after the eighth century, the Apocalypse became a major target of exegetical study and artistic illustration.[56] Unlike the multiple symbols, beasts, and allegorical types adduced for Satan/Antichrist in patristic and early medieval exegesis, the human figura in the Valenciennes Apocalypse presents a physical and historical reality.[57] Here the image of the naked and helpless male body serves as a forceful means of describing exposure and vulnerability.[58] The bound body acknowledges a satanic presence and at the same time asserts his radical exclusion, denial, and repudiation.[59] Below the terrifying pair, an empty expanse of white vellum suggests the abyss, a potential place of banishment and oblivion that could serve to assuage the viewer’s aversion and fear.

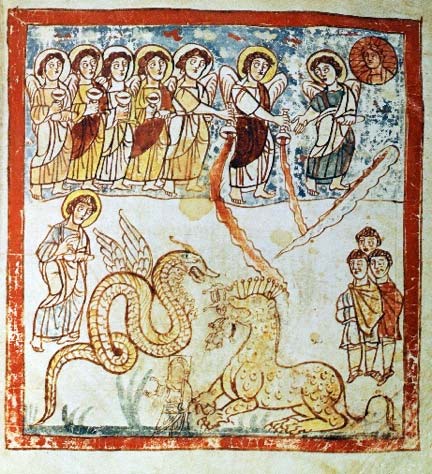

Further visual evidence of a growing need to suppress an already present human Antichrist can be seen in the Trier illustration for Revelation 16:13 (Figure 3), in which the False Prophet becomes a minuscule human figure wrapped in drapery and marked by a square nimbus signifying that he is a living person.[60] Here, we are confronted by a disturbing ontological contradiction. Just as the giant’s monstrosity inheres in its proportional violation of the human norm, the deviant shrunken scale of the Pygmy or dwarf excludes this tiny enigmatic figure as human.[61] Although fully dressed, Trier’s Antichrist has been disempowered both by his diminished stature and by his lack of substance. As Cohen points out, however, the tiny monster “can turn immaterial and vanish, only to reappear somewhere else, thus staging its threat in its power to shift back and forth between the corporeal and incorporeal, between the visible and invisible.”[62] In contrast to the gigantic Beasts that coil and crouch solidly above the river running along the bottom frame, the dwarfed, transparent incarnation of Antichrist disappears into the Euphrates, like a powerful chimera which will dissolve only temporarily and then suddenly resurface at another time and place.

Fig. 3. Pouring of the Sixth Vial (above); the Dragon, Beast and False Prophet Emitting Evil Spirits (below). Apocalypse, Trier, Stadtbibliothek MS 31, fol. 51r (Photograph: Stadtbibliothek, Trier)

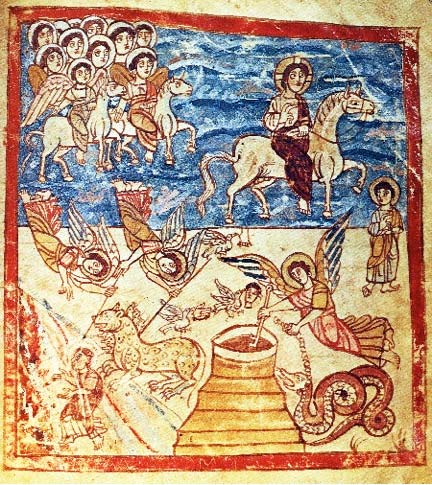

Fig. 4. Army of Heaven (above); the Beast and False Prophet Consigned to the Fiery Lake; the Angel locking the Dragon into the Abyss (below). Apocalypse, Trier, Stadtbibliothek MS 31, fol. 64r (Photograph: Stadtbibliothek, Trier)

In a subsequent, conflated image (Figure 4) in which the Trier designer merges Revelation 19:20 and 20:1-2, the diminutive False Prophet reappears, still in the company of the Beast, as they are thrust along a downward diagonal trajectory into the flames of the fiery lake. The small human figure raises his open palms in a gesture of surrender as two angels join forces to consign him to the burning sulphur in the lower left corner. Perhaps initially mistaking the False Prophet for the very similar small figure of Saint John at the right edge of the frame, Antichrist was given a circular nimbus (which was subsequently erased) in an ironic gesture of misrecognition that inadvertently demonstrates the often indiscernible differences between true and false prophets, in this case, between the human and the monstrous.

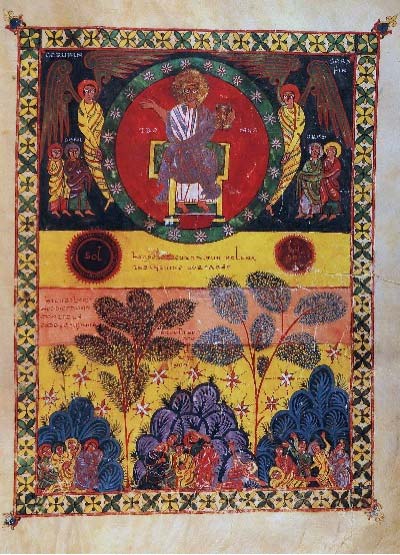

In the Valenciennes text-illustration for Revelation 20 (Figure 5), we encounter a pair of problematical figures, now entrapped together in the lower rectangular green register beneath the upper celestial space dominated by the Lord enthroned. Although the titulus designates the Devil, still embodied in the two-horned serpent, he is no longer enchained with the False Prophet but with a gigantic human embodiment of Infernus. They writhe together in a synchronic coil, forming an indissoluble bond that blurs the separation of their identities and continues to reinforce the reader’s intuitive impulse to see again the monstrous fused pair as a composite dual embodiment of evil. The naked body of Infernus is rendered as a deep indigo silhouette, representing the black skin that has already begun to serve as a distinguishing mark of the devil in the art of the early ninth century.[63] As if absorbing the darkness of the coiling serpent, he touches its underside with his left foot. The blackened figure then extends his right foot over the frame, linking both monsters with the central dark blue panel of the segmented frame, which in turn serves as a powerful chromatic magnet that will fix them in place for eternity. Like most of the angelic figures in the Valenciennes Apocalypse, however, Inferno’s black hair is crowned by a narrow gold fillet that unequivocally identifies him as the fallen angel, Lucifer, whom Jeffrey Russell described as a “hulking pathetic creature who had once been an angel of light.”[64] His lifeless body becomes a signifier of humankind’s fallen state as well as a metaphor of divine punishment.[65] Now transformed into a cadaver signifying “Death and Hades,” the darkened corpse is seen as a jettisoned object, emitting vile pollution from within and embodying death as the ultimate state of abjection.[66] Within the vertical hierarchy of the entire image, the triumph of light over darkness, good over evil, order over chaos, and of the incarnate Christ over diabolic monstrosity, is assured, as all power is visibly invested in the divine ruler seated on the throne.

Fig. 5. The Lord Enthroned (above); the Beast and False Prophet Enchained in the Fiery Lake (below). Apocalypse, Valenciennes, Bibliothèque Municipale MS 99, fol. 37 (Photograph: Ville de Valenciennes)

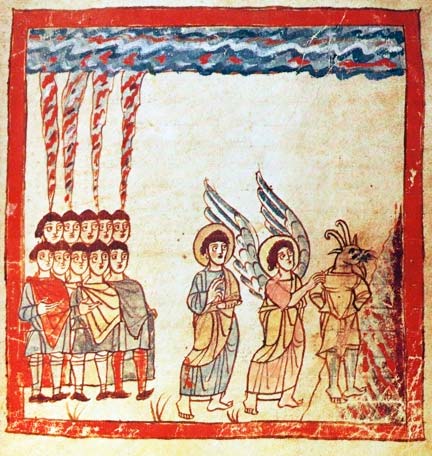

Fig. 6. Fire Consuming the Army of Gog and Magog (left); the Devil Thrown into the Lake of Fire (right). Apocalypse, Trier, Stadtbibliothek MS 31, fol. 66r (Photograph: Stadtbibliothek, Trier)

In the Trier Apocalypse, the illustration for this text (Figure 6) constructs the devil as a singular hybrid creature with the human body of the False Prophet (Antichrist) and the head of the two-horned Beast.[67] The incoherent form of the monstrous hybrid refuses to be identified within the “order of things,” thus rendering him dangerous. As Julia Kristeva observes, the Apocalypse seems rooted on a fragile border where identities are “double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject.”[68] This disturbing ambiguity apparently incited a later reader to deface the head with dark ink in an effort to disable the power of the image.[69] However, the designers of both the Valenciennes and Trier Apocalypses had already provided a sequence of reassuring images of the bound figures of Antichrist and the serpentine Satan; together, the illustrations clearly obscure their release and thus deny their eschatological effects of rampage and death.

In the later Bamberg Apocalypse modeled on Valenciennes, we encounter the same sequence of imprisoning the diabolical pair, Satan and the False Prophet (Antichrist),[70] similarly represented in the guise of the naked male figure and the two-horned serpent, respectively (Figure 7). However, the lower register now frames a new image of their release in a reversed mirror-like reflection of the upper scene. Although the text does not identify their deliverer, the Luciferian winged figure with black flaring hair is clearly a fallen angel.[71] Indeed, the human Pseudo-Prophet, now with flaring hair, turns back to create another mirror image of facing profiles of the diabolical figures. The newly interpolated image could be seen as inaugurating the time of Antichrist according to the ninth-century commentary of Haimo of Auxerre as well as that of the later chronicler Radulfus Glaber,[72] but Satan and Pseudo-Prophet remain securely bound, and the potential threat is soon thwarted in the next illustration on folio 53. In Bamberg’s new version of the Last Judgment, a bound naked figure of the False Prophet has already taken up residence in the lower right corner of the inferno.[73] Within the context of the imperial ideology established in the Carolingian period and revived with renewed conviction by the tenth- and early eleventh-century German emperors, the release of Satan and Antichrist would clearly have posed a threat to the interests of Otto III.[74] Thus we see a vigorous defensive reaction to thwart such an eschatological possibility in the aggressive physical restraint imposed upon the two most powerful enemies of Empire and Church.

Although we must make a critical distinction between eschatological expectations and a prophetic focus on the passing of the first millennium, it is tempting to link the coincidence of the year 1000 and the making of the Bamberg Apocalypse with millennialist expectations.[75] Time in this medieval sense was not precisely calibrated but nevertheless keenly and intuitively felt.[76] Contemporary disavowals such as that of Abbo of Fleury in 998 clearly respond to an intensified feeling that the end was imminent.[77] As Johannes Fried has convincingly argued, however, the Carolingians provided the theological base for the Ottonian doctrine that a strong Empire and Church could stave off the advent of Antichrist.[78] Nevertheless, the exaggerated, theatrical gestures embodied in the bold line and striking colors of the Bamberg Apocalypse can be seen to convey a new and compelling sense of urgency in the Book of Revelation’s prophetic visions.

Fig. 7. The Beast and False Prophet Consigned by an Angel to the Fiery Lake (above); Lucifer Releases the Beast and False Prophet (below). Apocalypse of Otto III, Bamberg, Staatsbibliothek Msc. Bibl. 140, fol. 51r (Staatsbibliothek, Bamberg)

The Morgan Beatus

The sudden appearance and proliferation of apocalyptic picture cycles for the Spanish Beatus commentaries in the tenth century seem to have shared with the Carolingian and Ottonian apocalypses a similar ideological investment in the cultivation and perpetuation of a powerful cultural tradition centered on an idealized image of the Church.[79] Internal threats to Church orthodoxy as well as the Muslim domination of all but a small Christian enclave in northern Spain gave particular impetus to apocalyptic concerns with the trials that would precede the triumph of the Church at the end of time. The scribe of the earliest surviving illustrated Beatus text (Morgan M. 644) explained that the book was produced “so that those who know may fear the coming of the future judgement at the world’s end.”[80]

Although still operating within the ecclesiological traditions of patristic and early medieval exegesis when he wrote the first version of his commentary in 776, Beatus of Liébana saw the Apocalypse as a treatise on Antichrist and the signs by which he could be recognized at the end of time.[81] There seems to be sufficient evidence not only in the Beatus text itself but also in contemporary Spanish chronicles to suggest the currency of beliefs that the Antichrist had already been born and that the world would end in the year 800.[82] Although the passing of the prophesied endpoint undoubtedly caused the terrors of 800 to lose some of their potency, the eschatological expectation that initially inspired the Beatus text made a lasting impact on the entire Spanish tradition of picture cycles in the representation of an explicitly human but monstrous Antichrist.[83]

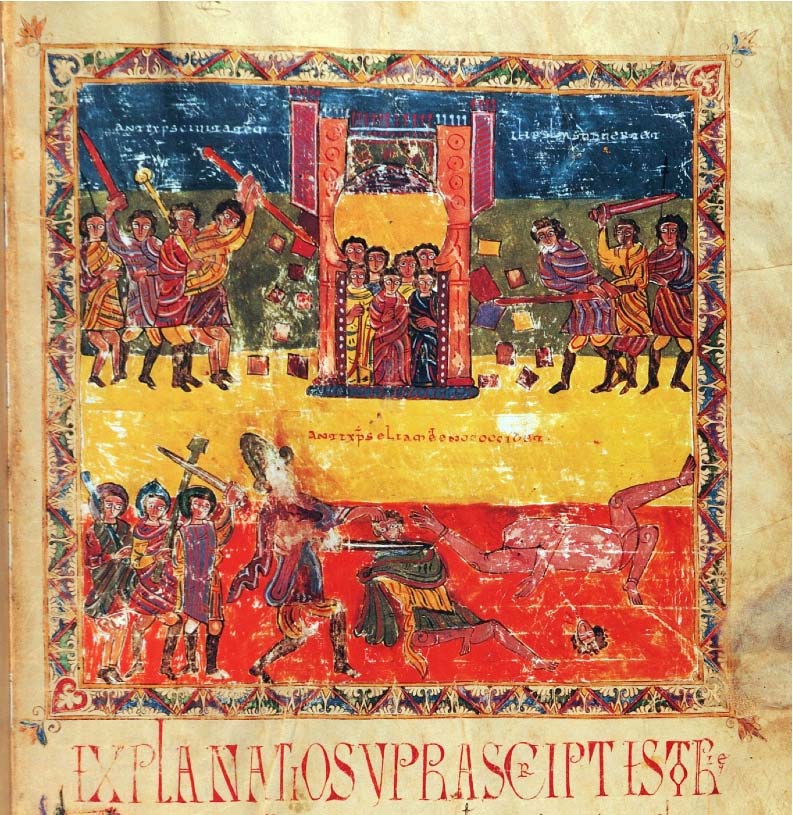

In the tenth-century Morgan Beatus, we see an insistent repetition of images showing Antichrist attacking the Church. In the illustration of the Massacre of the Witnesses (Figure 8), the assassin is named Antichrist and the city being destroyed is identified in the inscription as Jerusalem.[84] The pictorial juxtaposition in superposed registers forges Antichrist’s attach on the Church (Jerusalem) and the killing of the Witnesses into an ideologically charged visual synthesis. The earliest Beatus illustrations followed on the heels of the mid- ninth-century martyrdoms in Córdoba where more than fifty Christians were beheaded for professing their faith. Viewers who remembered the event were invited to identify with the abject fallen, naked male figures of the Witnesses. At the same time, Antichrist can be seen as a Muslim overlord, an association further pressed in some manuscripts by the exotic headgear worn by the executioner.[85] The monstrous human Antichrist now becomes the detested alien tyrant who massacres Christians who protest his perceived reign of terror. In an eloquent cry of contemporary protest, Paulus Alvarus exclaims, “And what persecution could be greater, what more severe kind of suppression can be expected when one cannot speak by mouth in public what with right reason he believes in his heart?”[86]

Fig. 8. Destruction of Jerusalem (above); Antichrist Executing the Witnesses (below). Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse (Morgan Beatus), New York, Morgan Library MS M. 644, fol. 151r (detail) (Photograph: ©The Morgan Library and Museum, New York.)

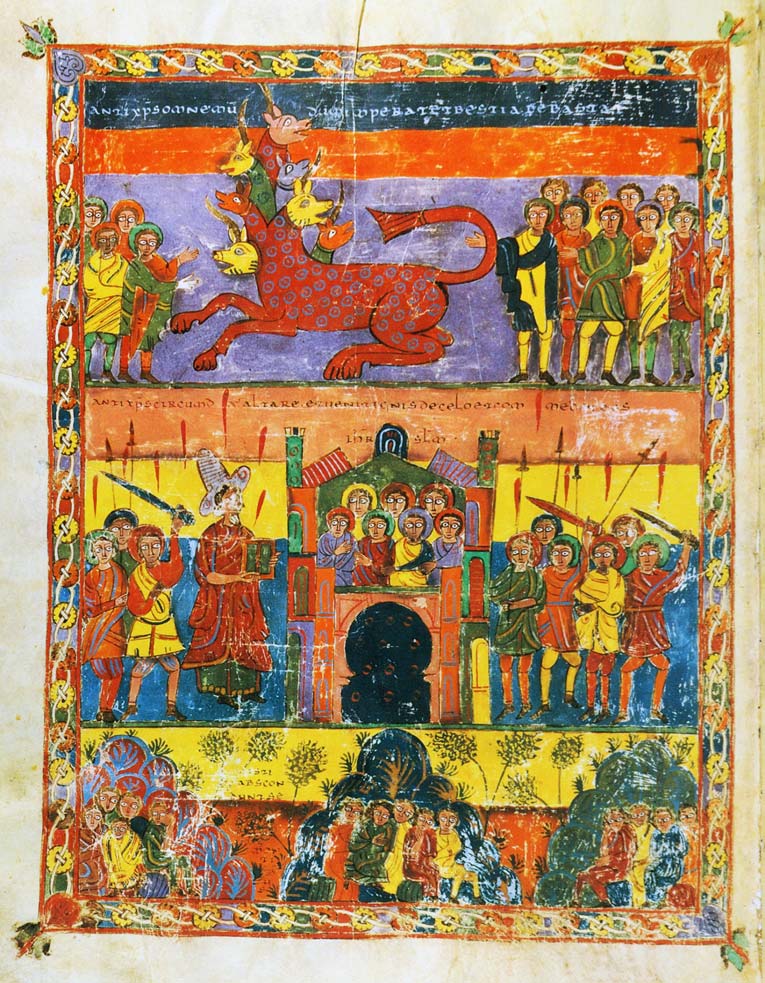

An unmistakable resonance of the Carolingian reading of the Sixth Seal can be seen in the Morgan Beatus image of the human Antichrist in Revelation 20 (Figure 9), which illustrates the passage describing how Satan will be unleashed to deceive humankind, devour the saints, and destroy the “beloved city” by fire (Rev. 20:7-9).[87] At the head of a triple-tiered composition, in response to the long Beatus digression on the Beast in Revelation 20, we see Satan in the form of the seven-headed Beast from the Sea. As Rosemary Muir Wright points out, the inscription explicates this vague text by asserting that Antichrist and the Beast are one and the same: Antichristus omne mundum imperat et bestia debatat.[88] In the middle zone, a giant-scaled human Antichrist, beaded and wearing a tall hat, appears as a high priest of the Old Testament, holding the tablets of Moses and preaching the Old Law against Christ and the Trinity. By surrounding him with men wielding swords, who represent the harsh justice of the Old Testament,[89] the image is transformed into an attack on Jews as well as Muslims. More significant, however, is the connection the viewer is prompted to make in recognizing the visual repetition of the earlier illustration of Antichrist killing the Witnesses from Revelation 11,[90] which brings the image within the orbit of the contemporary experiences of anti-Christian persecution in Muslim dominated Al-Andalus. In the bottom register, three groups of figures signify the end as they huddle together under the protection of mountains in an unmistakable reprise of the illustration of the cosmic earthquake of the Sixth Seal (Figure 10), in which the heavens and earth flee from God’s awful presence.[91] The cringing figures represent the refugees whom Beatus describes as those who flee to the mountains where they will be protected from the Devil’s sight for three and a half years, thus accounting for the otherwise inexplicable reiteration of the illustration for Revelation 6:16 where the people hid in caves from Antichrist.[92] The image very probably would have had a special poignancy for tenth-century Mozarabs who had recently fled from the Muslim-dominated south.

At this point, it might be useful to ask to what extent the Beatus manuscripts constituted an anti-Muslim polemic. Although the imagery invented for the Visigothic text cannot be seen as having been shaped by a mentality as sharply defined as the ideological engine that drove Spain to its great victories from 1080 to 1150,[93] significant links can be argued to have existed between Visigothic renewal and a rejection of Islam at the beginning of the pictorial tradition in the early tenth century. The brilliantly colored illustrations of the Beatus text appear to have constituted strident professions of orthodox Christian faith comparable to the loud professions made by the martyrs of Córdoba. In the early period before the military gains of the Reconquista, bearing witness was the only weapon available to the soldiers of Christ.[94] In the grotesque human Antichrist clearly caricatured as the monstrous alien Other, we are invited to recognize the heated anti-Muslim rhetoric of Paulus Alvarus, who in the late ninth century identified Muhammad with Antichrist.[95] In both Morgan Beatus images, the tall figure in voluminous Muslim robes and trousers wears an enormous high-crowned hat in the shape of an oversized phallus that serves not only to exaggerate his height but also to signal the sexual prowess of mythical proportions claimed for Muhammad as well as the giant Antichrist. Defined as a generic monster, the Beatus giant is thus perceived as a violently gendered male body.[96]

Fig. 9. Release of Satan as Beast (above); Antichrist Attacking Jerusalem (center); People Seeking Refuge in Mountains (below). Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse (Morgan Beatus), New York, Morgan Library MS M. 644, fol. 215v (Photograph: ©The Morgan Library and Museum, New York.)

Fig. 10. The Lord Enthroned (above); Sixth Seal (below). Beatus Commentary on the Apocalypse (Morgan Beatus), New York, Morgan Library MS M. 644, fol. 112r (Photograph: ©The Morgan Library and Museum, New York.)

In Cohen’s Lacanian interpretation, the rapacious hypermale projects his power upon the conquered land in the form of the phallus.[97] As David Williams remarks, after the head, the most important index of monstrosity resides in the genitals.[98] In the Beatus image of Antichrist-Muhammad, the phallic hat transforms his head into a sexual organ of abnormal size. Throughout the Middle Ages, amulets and other small objects in the form of autonomous male genitals seem to have been ubiquitous.[99] In his Indiculus luminosus, Alvarus took it upon himself to undertake a graphically detailed explanation of how the line from Daniel 11:37, “And he shall follow the lust of women (Et erit in concuspiscenti feminarium),” characterized the sexual prowess claimed for Muhammad, the Antichrist:

[Muslims] recount and babble, as if proclaiming something noble, that this pimp of theirs, preoccupied with the activity of seduction, had obtained the power of Aphrodite in excess of other men . . . that he had a greater quantity of liquid for his foul activities than the rest . . . and that he had been given the endurance in coitus and indeed the abundance of more than forty men for exercising his lust for women.[100]

In response to the monstrous composite figure of Muhammad-Antichrist, a later reader of the Morgan Beatus vigorously defaced the heads of both figures.

Liber Floridus

When we turn to the early twelfth century, we encounter a radical shift from allegorical, ecclesiological readings of the Apocalypse to more direct and urgent expressions of eschatological expectation. While the manuscript production of the traditional illustrated Beatus commentary continued unabated in Spain, a new and remarkably innovative wave of apocalyptic imagery emerged in the northern European regions of France, Flanders, and Germany. What appear to be the most striking features of this renewal of creative energy are not only its wide diversity of texts, cultural contexts, and centers of production, but also the preponderance of singular ingenious creators, both men and women, whose imaginative enterprise reached beyond the traditions and confines of their monastic worlds to embrace the encyclopedic scope of all human history, prophecy, and intuitive knowledge, both spiritual and secular. Although such stellar twelfth-century figures as Herrad of Hohenburg, Rupert of Deutz, Honorius Augustodunensis, and Hildegard of Bingen spring to mind, in the interest of brevity I have chosen to single out Lambert of Saint-Omer, whose Liber Floridus is brilliantly marked by a striking innovative interplay between text and image.[101] In contrast to the others comprising this constellation, Lambert’s influence extended into the fifteenth century via nine faithful copies of the Liber Floridus that enable modern scholars to gain an adequate understanding of this massive undertaking as a whole.[102]

The Liber Floridus is an eccentric collection of chapters on diverse subjects of sacred and profane history compiled by Lambert of Saint-Omer in the Channel region of France around 1120.[103] An incomplete, large format copy of this copiously illustrated encyclopedia survives in Ghent.[104] The compiler presents himself in the Prologue, accompanied by a full-page author portrait (fol. 6v) as a secular canon of the collegiate church of Saint-Omer. Over a period of almost a decade, Lambert drew material from a wide range of sources, making repeated additions and modifications, which resulted in what now seems to be a somewhat sprawling, idiosyncratic work.[105] In many ways anticipating the massive thirteenth-century illustrated autograph manuscript of the St. Albans Chronica Majora of Matthew Paris, the Ghent version of the Liber Floridus is also an author’s working copy as well as a ‘presentation’ volume, written and illustrated on coarse and reused vellum sheets of various sizes.[106]

Although not rigorously trained in a regular scriptorium, in Derolez’s opinion, Lambert “is a good scribe, who writes in a rather old-fashioned type of Late Carolingian minuscule.”[107] Beyond his daunting achievement as, with very few exceptions, the sole scribe of his massive work, most scholars agree that there are persuasive arguments for assuming that Lambert also produced all the illustrations, based upon their critical relationship to the textual fabric of the Liber Floridus.[108] In subscribing to this view, Rosemary Muir Wright explains that

Word and image are essential features of the Liber Floridus, demanding that the reader use textual sources to locate and expand the subject portrayed in the illustration.. . . [Lambert’s] images are never static conventional representations of the theme, but are revitalised by the compiler drawing into their orbit references to other images and other texts, both within and without the reference work itself. Lambert’s pictures seem to evoke the pathways of his thinking . . . leaving the reader to find a way.[109]

Thus, we are invited to agree with Derolez that

The pictures in the Liber Floridus have such an eminent role in communicating the leading ideas of the book, they are so idiosyncratic and interwoven with the text, they so often replace the text as a medium, that they can hardly be the work of an artist other than the very man who conceived the book.[110]

The origins of Lambert’s work can be traced back to the seventh-century encyclopedia of Isidore of Seville, who set out to compile the sum of all knowledge in the form of an Etymology of nouns, carefully arranged by subject. Two centuries later, Hrabanus Maurus transformed the earlier secular work into an unsystematic mass of religious learning by adding an allegorical gloss to each of Isidore’s chapters, thus asserting an eternal truth behind each of his words, in their origin and meaning.[111] Dating from the first quarter of the twelfth century, the Liber Floridus stands at the head of a number of encyclopedias that comprise the most characteristic production of the period. Lambert’s original project, as indicated by the title, was modestly intended to be a varied collection of texts and pictures (“flowers”). In Saxl’s classic assessment, Lambert’s encyclopedia is a landmark achievement in marking “a selection from the wide realm of knowledge, combining eschatological, ethical, historical, and scientific teaching by means of texts and pictures.”[112] Ultimately overpowering any sense of well-defined order, this rich and varied compilation was produced by and for the literate, if not learned, canons of Lambert’s collegiate church, whose lives were devoted to religion and who at their leisure could pour over these pages, which, judging from their well-worn condition, may have served them for a lifetime.[113]

Lambert’s universal history opens onto an eschatological view of the present, based on the doctrine of the Six Ages of the world.[114] Moving beyond the theological and biblical structure of the past propounded by Bede and Isidore of Seville, Lambert’s encyclopedic compilation is guided by a belief in the approaching end of time, thus explaining the unprecedented gathering such eschatological material as the Pseudo-Methodius and Adso tracts on Antichrist, Fifteen Signs Preceding God’s Judgment, a florilegium entitled On the Coming of the Lord on Judgment Day, in addition to a pictured Apocalypse.[115]

For Lambert, one of the most important signs of the impending end was the contemporary presence of a Christian king in Jerusalem, to which he draws attention in a long history of the First Crusade.[116] Because the Christian recovery of Jerusalem was interpreted to mean that the reign of Antichrist was imminent, the new urgency of the Crusade had to be elucidated as part of God’s unfolding plan. The encyclopedic scope of all human history, prophecy and knowledge thus provided the eschatological context in which the Crusades became meaningful down to the local level at which the nearby Abbey of Saint-Bertin took on a significant role.[117] Apart from the section devoted to a chronicle of the First Crusade, references to actual events as well as to prophetic visions of the world’s end form a leitmotif running through the whole work. The entire history of the Roman Empire concludes with Charles the Bald rather than Charlemagne, a shift that moves the account into Lambert’s immediate geographical sphere. As Penelope Mayo points out, Charles the Bald was the last of the major Carolingian emperors who was directly involved in the preservation and protection of Saint- Omer at the end of the ninth century.[118]

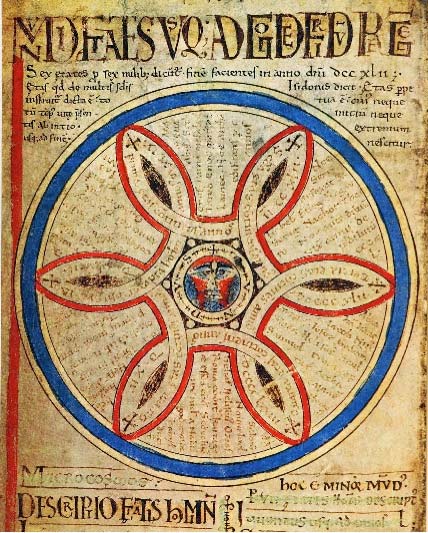

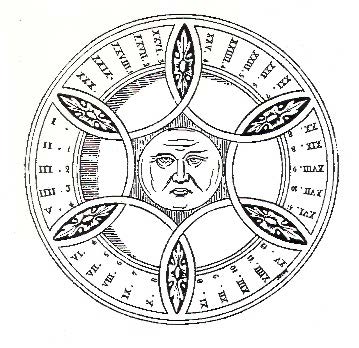

Lambert sets forth the fundamental eschatological premise of the Liber Floridus among the extraordinary number of diagrams designed as his response to the twelfth-century sense of an overwhelming abundance of conceptual and theological material. Entitled MVNDI ESTATES VSQUE AD GODFRIDVM REGEM, the scheme of the Six Ages (Figure 11) is comprised of a large blue-banded sphere encircling six wide interlocking arcs that enclose a central circle.[119] Based on a well-known geometrical design apparently derived from Bede’s lunar diagrams in De Temporum Ratione (Figure 12),[120] a human face is inscribed on the central planetary surface of the world (MVNDVS) that confronts the reader-viewer with a magnetic but disturbing image to which I shall return. The intersecting arcs are inscribed with the title of the Ages along with the length of their respective durations; the spaces within each semicircle carry the geneaologies and events pertaining to each Age. Breaking with this pattern, only the text for the Sixth Age gives a specific date. In reference to the title of the diagram, it relates to the First Crusade and its culminating event, the “crowning” of Godfrey of Bouillon (1099) as King of Jerusalem.[121]

Fig. 11. The Six Ages of the World, Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 20v (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Fig. 12. Diagram of Luna, Bede, De Temporum Rationale (after J. P. Migne, Patrologia Latina 90:384)

At the base of Lambert’s division of the spherical world’s temporal dimensions are lines linking the dual notions of Macrocosm as Mundus and Microcosm as Hominem that enable the metaphorical reading of the Ages of the World as the Ages of Man from infancy to decrepitude.[122] Along with Otto of Freising’s pessimistic declaration that “We see the world . . . already on the decline and exhaling the final breath . . . of advanced old age,” the canon of Saint- Omer placed himself in the era of the Last Age, nearing the end of time and of the world, which would culminate in the reign of Antichrist.[123]

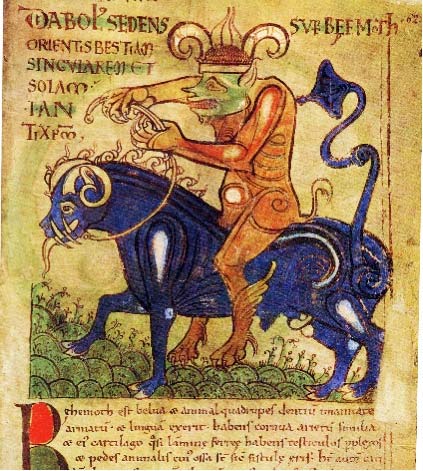

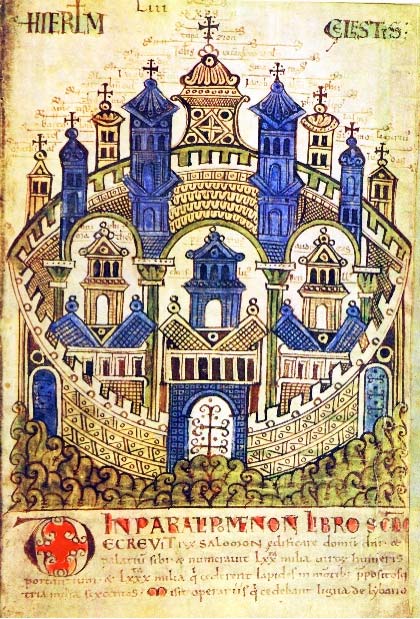

Although the lost Apocalypsis depictus can be accurately reconstructed from later copies of the Liber Floridus, far more relevant to the subject at hand are Lambert’s unique representations of Antichrist based on the two biblical monsters described in the Book of Job—Behemoth and Leviathan (Figures 13-14). The pair of symbolic creatures were drawn and painted on the recto and verso of a folio that Lambert decided to insert as two separate chapters at the end of his Bestiary.[124] However, his remarkable afterthought resulted in disrupting the logical order of his chapters on Fish within an already very strangely truncated bestiary that claimed lineage from Isidore’s Etymologiae but strayed very far from its purported model in almost every conceivable way.[125] Derolez astutely draws our attention to a striking pattern in Lambert’s radical interventions that were clearly intended to transform Isidore’s ancient natural history into the symbolic sphere of monsters. The chapter on Birds (XLVI) begins with a monumental picture of the Griffin (Figure 15), not really a bird, but a fantastic, cruel monster carrying a hapless tiny human figure in its beak, as it prowls across the page, digging its razor-sharp talons into the text below.[126] Lambert follows his abbreviated description of the Griffin on folio 58v with a cryptic remark, “yet, even here, the precious stone emerald will be discovered (Ibi etiam smaragdus lapis preciosus repperitur).” presumably, the monster’s brilliant blue and green body was meant to fix the idea in the mind’s eye in anticipation of the Lapidary, which begins with a list of the twelve apocalyptic stones (Rev. 21:19-20 on fols. 66r-67r). More important, however, is the image of the Heavenly Jerusalem, which will descend to earth at the end of time (Rev. 21:9-23). Lambert painted the celestial city as an elaborate full-page representation (Figure 16) on the recto of the other half of the inserted bifolio inscribed with the images of Behemoth and Leviathan (Figures 13-14), thus confirming his intention to establish inevitable connections between bestiary monsters, apocalyptic eschatology, and the Antichrist prophecies that follow.

Fig. 13. The Devil Riding Behemoth, Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 62r (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Fig. 14. Antichrist Enthroned upon the Tail of Leviathan, Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 62v (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Fig. 15. Griffin, Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 58v (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Fig. 16. Heavenly Jerusalem, Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 65 (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Before we direct our attention to these remarkable diabolical icons, we must situate them within the complex narrative of their codicological structure in order to understand fully what Lambert had in mind when he created them. In the autograph Ghent manuscript, each of the monsters from Job 40-41 dominates a full folio. As Jessie Poesch observed, the images, inscriptions, and text reiterate the assertion that the Devil, Behemoth, Antichrist, and Leviathan are not only interrelated but are virtually identical, as they embody the power of Satan in the world from Creation to the end.[127] Clearly based upon the allegorical explication of each of the beast’s body parts in Gregory’s Moralia in Job, one of the most influential and accessible of medieval texts,[128] Lambert’s pictures brilliantly render each anatomical detail both literally and with dramatic force. What binds the biblical monsters together is not only their coupling in the Book of Job but also Gregory’s repeated identification of both Behemoth and Leviathan as embodying the Devil and Antichrist at the same time.[129] This complex allegorical exegesis has been morphed into startling monumental images that capture the meaning of the text in a pictorial rhetoric that is as powerful as the monsters themselves.

As proclaimed in the banner headline, DIABOLVS SEDENS SVPER BEEMOTH ORIENTIS BESTIAM SINGVLAREM ET SOLAM, ID EST ANTICHRISTVM, we see Behemoth (Figure 13) being urged on by a gigantic horned devil-rider who equals if not overwhelms him in scale and aggression. The Devil himself is in turn pushed forward by the upward-flaring end of Behemoth’s huge draconian tail, which had been interpreted in extenso by Gregory as signifying Antichrist.[130] Indeed, the bestial Devil pulls the reins into an elegant loop that points to his other name. With clenched teeth, the slimy green-faced monster clumsily grasps the reins with fang-like claws and seems to paw the ground in an effort to accelerate the pace. Because the visible presence of the Devil creates an ‘alien’ intrusion into what purports to be a text illustration, Lambert has given him physical characteristics belonging to Behemoth to reinforce their allegorical identity. His body is thus rendered like polished bronze, complementing the intense blue metallic iron hide of his mount (quasi lamine ferree). The burnished, muscled belly visualizes the description of his power in Job 40:11 (et virtus illius in umbilicus ventris eius). Even more audacious are the revisions of the Job and Gregory references that Lambert introduces into the text and consequently into his picture. A striking example appears in the curiously curved horns of the ox-like Behemoth, generated by an insertion explaining that he has “horns like those of a ram (habens cornua arietum similia).” Lambert’s strategy of transferring Behemoth’s features onto the Devil extends to the upper part of the illustration, which is dominated by a pair of huge ram’s horns that sprout from the demon’s crown. By this ingenious move, Lambert succeeds in linking the Devil with the regal Antichrist image on the verso of the same folio, thus moving, as the reader-viewer turns the page, from the barbaric crown worn by the Behemoth rider to the Carolingian one worn by the figure enthroned upon Leviathan’s tail. Here, we again see a sequence of paired, dual images of the Devil-Antichrist, conceptually aligned with those first encountered in the Carolingian and Ottonian Apocalypses (see Figures 2, 5, and 7).

One more important but thus far overlooked (or avoided) body part awaits out attention—the “entangled” spermatic cords of Behemoth’s testicles (Nervi testiculorum eius perlexi sunt), which are referenced in the abbreviated text description (Job 40:12) beneath the image of the monster.[131] In his Moralia, Gregory dedicates two separate discourses on the monster’s nether parts that include lengthy word-plays on testis, which can denote either “testicle” or “witness,” at one point declaiming

Whoever is unbridled by voluptuous lust . . . to what extent is he the testis of Antichrist? . . . what therefore is he other than the testis of Antichrist who, having lost the moral authority of promises by faith in God, is responsible for giving the testimony of deception?[132]

Whereas the venerable exegete stresses how the tangled cords of the monster’s testicles signal the latent duplicity of his witnesses’ twisted, corrupting arguments, Lambert’s Behemoth happily strays from the biblical and exegetical texts, as his testicles swing freely in rhythmic accompaniment to his carefree passage over the verdant grass that provides his abundant sustenance.

In a contrasting corollary to Gregory’s warnings concerning the latent evil powers of Antichrist embodied within this remarkable bovine beast, Lambert visually celebrates Scripture’s heavy emphasis on his maleness. As Williams aptly reminds us, God commands Job to admire Behemoth’s phallic power: “Behold, his strength is in his loins, and his power is in the navel of his belly. He constricts his tail like a cedar; the cords of his testicles are entangled. His beginning is through God who made him” (Job 40:11-14). Such representations, both textual and visual, originated in the concept of God as Creator and the principle of generation of both good and evil.[133] In Lambert’s own imaginative creation, the Devil and Behemoth are fused into a dual-bodied hybrid monster relentlessly traversing the trajectory of time, as they literally embody the interpretive conclusion of Lambert’s text:

The world will come to an end when [Behemoth] traverses it. He signifies both the Devil who fell and Antichrist, the son of perdition, who will destroy, to the extent of his power, humankind and himself at the end.[134]

Just as Behemoth is the epitome of terrestrial monsters, Leviathan (Figure 14) is the epitome of all the monsters of the sea.[135] Juxtaposed on opposite sides of the same folio, the biblical monsters are conceived as diverse embodiments of the Devil and Antichrist whose joint powers cover the world as a universal malefic force. Like Behemoth who carries a rider, Leviathan is also ‘mounted,’ but rather than by another hybrid monster, his ‘cavalier’ is a handsome, young king. The inscription reads: ANTICHRISTVS SEDENS SVPER LEVIATHAN SERPENTEM DIABOLVM SIGNANTEM, BESTIAM CRVDELEM, IN FINE. As Poesch points out, the inscribed image is a direct reversal of the preceding Devil-Behemoth pair.[136]

Seated upon the Devil-Leviathan’s tail, Antichrist is no longer a bestial perversion of God’s image but what Debra Strickland has termed a “crypto- monster,” a normal human being who visually conceals his identity, thus allowing him to “deceive those around him, but not the viewer of the image.”[137] Here, Lambert is clearly driven by Gregory’s emphatically repeated references to Antichrist as a man.[138] Lambert’s Antichrist himself points to the surrounding inscription that informs the viewer-reader of his true identity as well as his claim to human parentage.[139] Leviathan, by contrast, follows the template designed for his counterpart, Behemoth. The hybrid sea-monster dominates his watery domain as he stands in profile, facing left, and displays in exaggerated detail the equally striking anatomical parts explicated in Gregory’s Moralia in Job. Described in the biblical text as “serpent . . . and monster and beast,” like Lambert’s Griffin, Leviathan is a winged quadruped with sharp feline claws. His huge green body is literally covered with rows of “compacted scales like molten shields (corpus illius quasi scuta fusilia et compactum squamis),” interpreted by Gregory as “all sinners, that is, because they are hard through obstinacy but fragile through living, they are to be compared to molten shields.”[140] In response to the commentary’s interpretation of Leviathan’s teeth as Antichrist’s wicked preachers (iniquos praedicatores Antichristi) who pervert the pious faithful with words and swords, we see the sea-monster’s teeth transformed into long, sharp interlocking tusks: “On account of his ring of teeth, who can open the doors of his face?”[141] Within the context of Lambert’s associative pictorial strategies, we might then see the elongated tusk-like extensions from Antichrist’s feet as signifiers of his false preachers, particularly because, as extensions of his perfidy, they are aligned in parallel with Leviathan’s teeth. Apparently in a move to draw the viewer’s eye to the visual convergence of allegorical descriptions, the bright red stockings of the seated ruler are similarly aligned with the lurid flames, which Gregory explains to be the evil persuasion emitted from the monster’s mouth that touches the hearts of men with the fire of earthly lust.[142] Even the vertical stem of the initial “L” in the monster’s name is banked by dark red tongues of fire that fuse together to echo the shape of its pointed teeth.

Although Leviathan’s tail is not mentioned in the biblical text, as Poesch points out, Gregory’s emphasis on one of the monster’s other forms as serpent would appear to explain its excessive length in the Liber Floridus image.[143] In one striking instance in the Moralia, Job’s text on Leviathan’s teeth is linked with Revelation 11:19: “Their power was in their mouths and in their tails.”[144] Lambert ingeniously pulls the magnificent extension of this appendage into a grand arc that encompasses the figure of Antichrist and provides the precarious throne upon which he sits. Nothing could express more elegantly Gregory’s assertion that the tail signifies the power of men in the world, and that the tail, which is behind, is the temporal condition of this world, which is clearly at the end, as Antichrist confirms by pointing to the words at the end of the inscription at the upper right—IN FINE.[145] As Schüssler wisely concludes, “the demonstrative gesture of the rule at the end of time and his impressive throne on the tail of Leviathan demonstrate the genuine eschatological relationship between the Devil designated in Leviathan and his last exposure, his tail (cauda).”[146]

So striking is Lambert’s composite visualization of Antichrist and the bestial sea-monster that it has inspired a number of attempts to find a possible pictorial model.[147] Source-hunting often fails to yield direct or critical insights into the intention or meaning of a medieval image. As we shall see, however, Lambert’s visual concept tends to contradict this assertion when we consider the nature of his creative process as a compiler of texts, that is, extracting and revising segments from other works to be reconstituted into a new entity. It seems entirely reasonable to assume that he adopted a similar approach in shaping his images. We should also remember that one of the major characteristics of twelfth-century “Romanesque” art is its basic tendency to construct visual images as well as buildings as “additive” compilations of separate, clearly articulated parts, not unlike the heavily leaded, brilliantly colored components of stained glass from this period. Similar patterns of analytical conception can be readily recognized in Lambert’s almost compulsive visual representations of Gregory’s dogged adherence to his biblical model in interpreting each of the contiguous but distinct body parts of Behemoth and Leviathan one by one.

Following the suggestion implied but not pursued by Richard Emmerson, we can now direct our focus to Lambert’s representation of Antichrist killing the Witnesses, which is missing in the autograph Ghent manuscript but carefully copied from the lost Apocalypse depictus in the somewhat later twelfth-century Wolfenbüttel manuscript (Figure 17).[148] The warrior riding the winged, crowned beast constitutes an unmistakable iteration of Lambert’s merger of Antichrist and the bestial Leviathan conflated into a singular monstrous figure. The hybrid monster, which turns its head toward the viewer in a toothy grimace, is identified in the inscription as the “Beast ascending from the abyss,” frequently seen by early commentators as another embodiment of Antichrist.[149] The rubric captions that identify the human rider as Antichrist and describe him as “thrusting a javelin into the bodies of the Witnesses” derive not from Revelation 11:3-7, but from a commentary that can be ascribed to Lambert himself.[150] Breaking with the traditional spatial relationship between heaven and earth, Lambert placed the true Christ directly beneath Antichrist as the divine undermining force. He holds the sword of divine judgment as opposed to the lance of the murderous barbarian.

Fig. 17. Antichrist Killing the Witnesses (above); Seventh Trumpet (below). Liber Floridus, Wolfenbüttel, Bibliothek Herzog August Cod. Guelf 1. Gud. Lat. 2°, fol. 14 (Photograph: Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel)

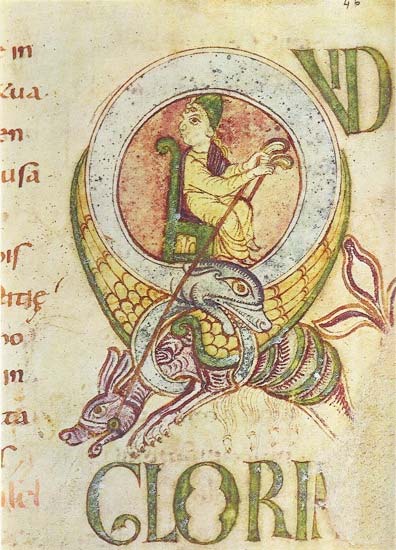

Although dressed in contemporary chain mail, Antichrist wears a curious hat with a conical crown and an extended curling tail-piece that resembles a Phrygian cap denoting an ‘alien’ from the East.[151] Whereas the distinctive Persian felt cap appears most notably on Early Christian sarcophagi, it frequently reappears in Carolingian ivory book covers and manuscript illustrations. Indeed, the early ninth-century Corbie Psalter, produced and housed in a Benedictine abbey within easy reach of Saint-Omer, contains three remarkable historiated initials featuring figures wearing fluted Phrygian caps, all viewed in profile—Doeg Idumaeus (the mule-driver), Goliath, and Habakkuk.[152]

In what might be considered one of the earliest extant representations of Antichrist as a man in the human figure who occupies the center of the initial “Q” for Psalm 51 (Figure 18), we might see, as Jean Porcher observed several decades ago, a visualization of the early commentary by Cassiodorus, who interpreted the Old Testament enemy of David as the arch-enemy of Christ.[153] The Corbie initial is formed by three creatures, which in some respects resemble Lambert’s serpent Leviathan and the claw-footed Behemoth, while the man seated on the throne can be seen to refer to an understanding of Antichrist as a traitorous tyrant.[154] The circle of “Q” is formed by the serpent’s tongue, which morphs into a tail, projected from his mouth into a figure “8.” The double edge of the pale blue tongue-tail that widens and swells as it encircles the figure of Doeg seems intended to visualize the text of Psalm 51:4 as well as the Cassiodorus commentary: “Your tongue is like a sharp razor . . . lying more than speaking the truth. O deceitful tongue, you love all words that devour.”[155] The tail of the “Q” is created by a winged, mule-headed, scorpion-bodied monster that attempts to escape through the small lower lobe formed by the serpent’s tongue/tail. Enthroned upon the head of the serpent, Doeg’s body faces right, but he anxiously looks back. Despite his pull on the reins, the powerful body of the scorpion-monster plunges downward over the word GLORIA, in fulfillment of the promise of ignominious ruin for the evil human embodiment of Antichrist.[156] The most significant and telling link that may have led Lambert to draw upon the Corbie Psalter for his pictorial conceptualization of both Leviathan and the Antichrist who kills the Witnesses in the Apocalypse might be recognized in the concluding text of the Cassiodorus commentary: “Just as at the world’s end Antichrist is to be destroyed by the two holiest of men, Elias and Enoch, [in this psalm] Antichrist is exposed [as] the son of iniquity.”[157] So it is that we can perceive the conflicted figure of Antichrist in the Old Testament guise of Doeg, immobilized and imprisoned within the engorging tongue-tailed body of the wicked serpent.

Fig. 18. Historiated Initial for Psalm 51: Doeg Idumaeus. Corbie Psalter, Amiens, Bibliothèque Métropole MS 18, fol. 46 (detail) (Photograph: Bibliothèques d’Amiens Métropole)

In Lambert’s Liber Floridus, another human Antichrist (see Figure 14), similarly enthroned but now diminished in scale, is also swallowed within the tail of another serpentine beast, Leviathan. Literally configured in the guise of Christ, Antichrist’s frontal enthronement and gestures closely mimic Lambert’s illustration of the apocalyptic Lord (Figure 19), holding the open book with the Lamb within a mandorla frame, which was originally intended for the lost Apocalypsis depictus but then revised to include the four elements so that it could serve as the opening page of the chapters on Astronomy.[158] As Emmerson observed, the Adso text to which Antichrist points gives the parodic, Christomimetic image a new and awesome power, “in order more effectively to deceive the world.”[159] With his left hand raised, almost as if in blessing, the handsome young king brazenly points to the text of his Vita, which reveals that “[he], son of perdition . . . will make his way to Jerusalem and sit in the temple of God as if he were God himself.”[160]

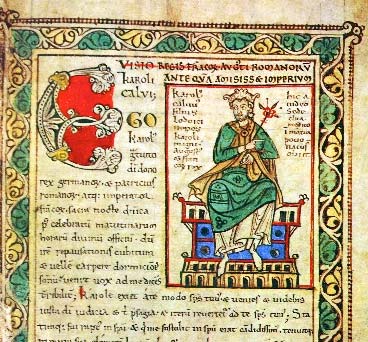

With the visualization of Antichrist as an earthly king, the Liber Floridus representation situates itself within an established exegetical as well as iconographical tradition. Read as an instructional document of theological ideology from the early twelfth century, the intellectually ambitious allegory of the Leviathan image expresses the whole intention of Lambert’s encyclopedia.[161] Antichrist also takes his place within the temporal framework of history, structured as the unfolding of a succession of empires and ages of the world and marked by a disconnected series of imperial portraits in the enthroned figures of Solomon, Augustus, and Charles the Bald (Figure 20).[162] Although the visionary Carolingian ruler turns his head away from the traditional frontal stare adopted by the other two sovereigns, he was clearly intended to be viewed as related in place and time to the Jerusalem recaptured during the First Crusade. Antichrist not only wears a familiar type of Carolingian crown, he also points to a self- referential text at his left. Instead of Charles’s cruciform foliate scepter, however, Antichrist holds an untraditional attribute of regal power, a lance, which Lambert invited his reader-viewer to recognize as the Holy Lance of Antioch. The infamous relic was taken by the Crusaders as a sign of divine favor when it was first found in 1098, but it soon proved to be a contrivance of human fraud and thus an appropriate emblem of a counterfeit ruler.[163] Just as Lambert drew attention to this ignominious “relic” of Christ’s crucifixion by thrusting the lance beyond the enframing tail of the Leviathan and painting it red, he inserted the text of the episode of its finding and fraudulence from the history of the First Crusade in a special space left blank at the end of the very long Gesta Francorum Hierusalem expugnantium.[164]

Fig. 19. The Lord and Lamb Enthroned, Liber Floridus. Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 88 (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Fig. 20. Charles the Bald, Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 207 (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

In conclusion, I would like to revisit the diagram of the Ages of the World (see Figure 11). It is here as well as in analogous schemata running throughout the Liber Floridus that Lambert proclaims most directly his allegiance to the new sense of history that evolved during the course of the twelfth century, an historical sensibility premised on the “supremacy of God, not only over the cosmos, but over all earthly events.”[165] In his magisterial account of this radical transformation of medieval recognitions, M.-D. Chenu centered his discourse on the new historical awareness of the workings of destiny and its obsessive tracing of the cosmic dimensions of time.[166] He concluded with an astute observation on the risks involved in the twelfth-century connection of events within the context of a messianic divine plan: “For the history of the world, eschatology can only introduce ambiguity; and allegorical interpretation is the literary effect of this ambiguity.”[167]

As Derolez concluded from his painstakingly meticulous analysis of Lambert’s autograph manuscript in Ghent,

The Liber Floridus is a metaphysical encyclopedia, not aiming at providing practical information . . . it is on the contrary focused on time-reckoning, cosmography and astronomy . . . and history in the widest sense . . . the whole pervaded by an emphatic sense of allegory and eschatology.[168]

Given the aberrant structure of the work as a whole, it is not surprising to encounter striking inconsistencies bordering on confusion in Lambert’s scheme of the Ages of the World. Breaking with the traditional duration of the Sixth Age usque ad nos, the era has already ended with Godfrey of Bouillon’s conquest of Jerusalem in 1099, clearly implying that this event did not signal the end of the world, since Lambert composed the work almost two decades later. At the bottom of the folio, however, Lambert altered the number of the ages of man by inserting gravitas between juventus and senectus, but ending with the usual decrepita usque ad annos finis.[169] By implicitly extending the Aetates Mundi from six to seven, the reader-viewer is obliged to find present time elsewhere within the temporal confines of the schematic circular universe. The Seventh Age cannot be anything other than the inner circle inscribed MVNDVS. In an explicit effort to guide the spectator to this conclusion is the small cross at the apex of the circle, forming a signum that links the central sphere with identical terminal crosses at the apex of each of the six lobes representing the first six Ages.[170]

Lastly, we must deal with the ominous human head (Figure 21) in which the intense red and blue hues of the dynamic interlocking and tangential frames converge in a lurid, painted mask—an image that can be imagined to have morphed from an iconic stained-glass face of Christ into a monstrous demonic mask. Although the human face could be read as a personification of Mundus, the twelfth century’s preponderant concern with systems that established anagogical relationships between the contemporary temporal world and the divinely ordered cosmos was apparently not satisfied with merely reviving this tradition.[171] Thus we see that Lambert transformed his model, which can be identified as Bede’s diagram of lunar cycles in De Temporum Rationale (see Figure 12), with its six interlocking arcs surrounding a central circle inscribed with the human face of the moon.[172] As Mayo has suggested, Lambert created a new temporal structure in which the last Age of Man is marked by the distorted, tortured image of Mundus as Antichrist, “hovering above the world like a monstrous cosmic phenomenon.”[173] Painfully stretched over the surface of the globe, the emaciated remnant of a human face, by turns frozen and seared by the elements of ice and fire, rivets our horrified gaze as we are invited to look into the future and to realize the threatening imminence of the end of time and of the world.

Fig. 21. The Six Ages of the World, detail: Mundus. Liber Floridus, Ghent, Universiteitsbibliotheek MS 92, fol. 20v (detail) (Photograph: Ghent University Library, Cultural Heritage Collection)

Although riddled with breaks and discontinuities, the autograph manuscript of the Liber Floridus reveals a structure almost unique to Lambert but at the same time entirely consonant with twelfth-century patterns of thought. Unlike the Late Antique encyclopedic formulas resurrected by Isidore of Seville and Hrabanus Maurus or the scholastic constructions that dominated medieval compilations from the thirteenth century on, the logic of the Liber Floridus is what Derolez describes as “associative” in nature:

Mental associations evoked by one chapter become the subject of the next. That way, chains of chapters are created, e.g., dealing successively with . . . the Antichrist prophecy, the First Crusade . . . the global and synthetic view of the world . . . so typical of the Romanesque mind, favored a simultaneous consideration of Creation and History in their multiple senses, literal and symbolical. The World as a whole, in its static and dynamic aspects, is the subject of Lambert’s work. Associative thought and multiple senses are the basic features of the Liber Floridus.[174]

Within the context of Derolez’s interpretative insight, Lambert’s earliest reference to Antichrist in his inclusion of the so-called Epistola Methodii de Antichristo can be seen as fundamentally important for understanding the entire work.[175] The text on folios 108v-110r is not the well-known Pseudo-Methodius Prophecy, but an abbreviated version of Adso’s tenth-century letter.[176] The most critical of Lambert’s revisions must refer to the First Crusade in its claim that, after the conquest of Jerusalem, a Frankish prince has been crowned king of Jerusalem. With this in mind, Lambert’s startling decision to make Godfrey of Bouillon the closing figure of the Sixth Age can now be understood, along with his inscription of the World in the Seventh and last Age with the saddened but nonetheless terrifying death mask of humanity in the guise of the last monster.[177]

* * * * *

The overall intention of my present analysis has been to open possibilities for further exploration of “horizontally” structured visualizations of the apocalyptic end that seem to have been conceived as part of the earliest extant medieval images and picture cycles. The meaning of history and its end appear to have existed as a critical subtext of apocalyptic discourses since the early ninth century. Whereas the political and ideological survival of the Empire in the Carolingian and Ottonian dynasties played a pivotal role in the eschatological drama of early medieval apocalyptic prophecy, the First Crusade provided the catalyst for a more forceful and explicit expression of expectation in Lambert’s images designed for the twelfth-century Liber Floridus. Centered on the multiple embodiments of Antichrist as harbinger of the coming cessation of the time and the world, his problematic figuration in the early Middle Ages generated a constellation of shifting notions of monstrosity, ranging from invisibility (denial) to larger than life, from giant to dwarf, from hybrid beast to the ultimate deception of human form.