Sara Varanese • Rutgers University

Recommended citation: Sara Varanese, “Elephants, Yogis, and Kings: Ritual and Ecology in a Seventh-Century Forest Hermitage in Eastern India,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/CICV1742.

Introduction

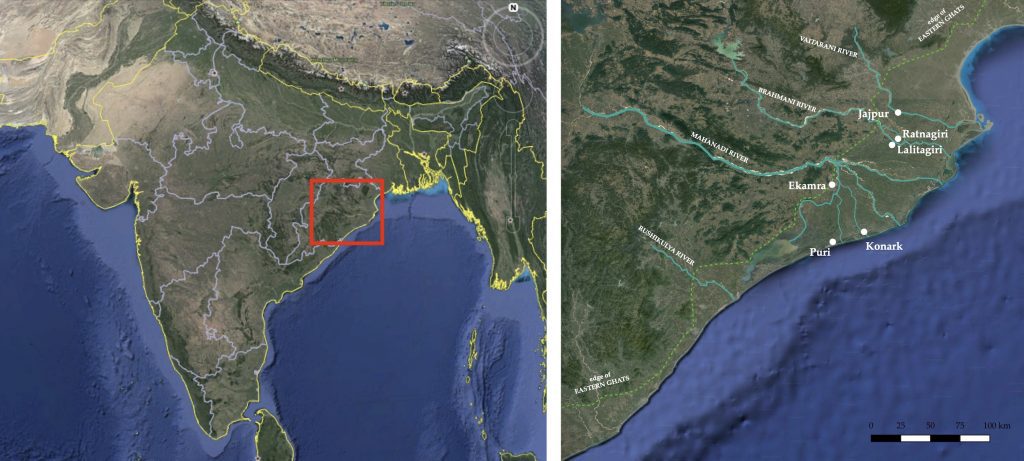

Encircling the walls of the seventh-century Parasuramesvara temple in Bhubaneswar (eastern India) are images of yogis dancing and offering garlands to the deity Shiva, nature spirits, monsoon clouds and herds of wild elephants. These reliefs echo the surroundings of the temple at the time of its construction, a Shaiva hermitage that was established in one of the densest forests of the subcontinent. The seventh century can be understood as a transition period leading to the increasing appearance of temple urbanism across the Indian subcontinent. Often pointing to the rise of new rulers and religious lineages, the settlements that were established at this time often grew to become important urban centers of the early medieval period (ca. between the sixth and thirteenth centuries). This was the case for Bhubaneswar, known as Ekamra in the premodern period (Fig. 1). Ekamra became an important pilgrimage center between the eleventh and thirteenth century, with dynastic patronage and powerful religious institutions supporting the construction of monumental temple complexes. The city today is still known for the massive Lingaraja temple, which continues to be the focus of ritual pilgrimage. This landscape, however, originated in the sixth and seventh century as a much more diffuse type of settlement, a forest hermitage where clusters of temples gathered on interregional travel routes, vanguards and catalysts of later urbanization.[1]

Fig. 1. Bhubaneswar, premodern Ekamra, is located in the region of Odisha in eastern India. It was part of a local network of sacred sites, organized on long distance travel routes that followed the path of rivers and edge of the ghats. (Map data: Google, ©2025 NASA).

Bhubaneswar’s historical layers are a rare example of a South Asian landscape where continuous urbanization has not completely eradicated traces of its previous iterations. As a result, they allow the study of long-term processes of settlement. This study, however, has not yet been undertaken. Bhubaneswar’s many temples have been published in a number of art historical surveys as individual monuments. Their dating and stylistic development have been analyzed and discussed, as have their patronage and iconographic programs.[2] However, they haven’t yet been studied as constituting a unified settlement system, nor have they been grounded in the environmental and social geography that determined their construction in the first place.

By examining Bhubaneswar’s earliest material remains, this article suggests that the city’s foundation as a forest hermitage can be seen a deliberate act of placemaking by the Pashupatas, a lineage of ascetics devoted to the god Shiva. This religious lineage intentionally engaged and responded to the environment, inscribing onto it layers of ritual meaning through building campaigns and iconographic programs. Through the continued layering of meanings and practices the built landscape was “activated” and connected with sacred potency.[3] Early temple programs reveal the Pashupatas’ desire to fashion their earthly hermitage into a sacred forest retreat. The association of the site with the lineage was conveyed by ritual scenes and specific iconography, while the idea of Shiva’s forest was evoked by temple reliefs that engaged the wilderness surrounding Ekamra, imbuing it with spiritual potency through the animated presence of divine and semi-divine inhabitants. The Pashupatas illustrated themselves within this landscape, dancing wildly or engaging in ritual offerings, the human inhabitants of the sacred forest of Shiva.

This article unpacks a key experimental moment in the establishment of temple architecture. Ekamra’s sixth and seventh century temples, among the first structural stone temples in India, show iconographic discrepancies and variation, especially if compared to the rigid framework of later temples, which arose as local and sectarian cults were being absorbed into mainstream and dynastic forms.[4] A close analysis of iconographic programs, however, suggests a distinction between the main icons of the temple, which remain relatively constant across centuries, and secondary icons.[5] Secondary panels and reliefs on early temples contained rich and detailed narrative content, which was simplified and standardized into decorative motifs in later centuries. Through a careful reading of these reliefs, and by grounding the temples in the local landscape of sixth and seventh century Ekamra, we may gain some understanding of the practices of the ascetic communities that constructed and inhabited this site, of the environmental history of Eastern India, and of the interaction between humans and other animals in this landscape.

In the first half of the article, I introduce the historical context surrounding the site’s first temples and situate them within broader practices of placemaking during the early medieval period. I introduce how the early settlement was established on long-distance travel routes, and examine how it negotiated the site’s forested ecology and abundant waters to construct a spiritually potent landscape. I examine the depiction of sectarian ritual practices within the temple’s visual program as forms of self-fashioning, through which the Pashupatas represented their practices to non-initiated devotees, with a particular interest in the dance ritual that was specific to this lineage and that featured prominently in Bhubaneswar’s temple reliefs.

In the second half of the article I focus on how temple reliefs echoed local ecology, symbolically reinforcing the association between the site and Shiva’s forest hermitage. I reveal the ways in which temple reliefs illustrate this landscape through narrative depictions of the monsoon, and through the personification of nature elements into semi-divine beings, which transformed the lived hermitage of the Pashupatas into a heavenly forest inhabited by deities and other supernatural beings. I specifically examine the many narrative scenes which depict the abundant herds of wild elephants that populated the forests around Ekamra. These scenes locate the Shaiva hermitage in the dense elephant forests (gajavana) of Eastern India, and at the same time reveal the complex relations between the seventh century human community and the powerful ecology with which they would have interacted daily.

The hermitage

Ekamra emerged on an important intersection between a historical north-south route which ran along the eastern coast of the subcontinent to the Gangetic valley, and the riverine route of the Mahanadi which led inland and to the North Deccan and Central Highlands.[6] These routes had connected important administrative centers of the Mauryan Empire for centuries. The site of Ekamra in fact coincided with one of these centers, tentatively identified with Toshali.[7] Mauryan centers were abandoned around the fourth century CE, as part of a generalized contraction of urban spaces across South Asia.[8] However, they did not leave a complete vacuum of settlement. In the site of Ekamra, sites of ritual activity that had developed around the administrative center, including a stupa and various cave sites, likely maintained active communities.[9]

At the turn of the seventh century, a number of Shaiva temples were layered onto this preexisting landscape. This new phase of settlement in Ekamra was tied to the rise of Pashupata Shaivism. The Pashupatas were followers of the deity Shiva who practiced asceticism and renunciation, and who gained favor during the early medieval period.[10] The seventh century saw a proliferation of Pashupata centres, many of which were located in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.[11] The establishment of Pashupata hermitages and pilgrimage centers coincided with a key moment of institutionalization which could be felt also through textual production, most notably the composition of the Skandapurana.[12]One of the most important foundational texts for the Pashupatas, the Skandapurana includes narratives of important episodes in Shiva’s mythology, which are made to bear on the landscape of northern India, that the Pashupatas were at the same time settling.[13] Through the Skandapurana, the Pashupatas aimed to define and legitimize their own lineage while inscribing it in a physical geography, which was in turn connected to mythological traditions. In this way they sanctified the landscape “by representing it as the scene of primordial events.”[14] The text, though codified through ritual and mythological language, had a sociopolitical purpose, its construction a complex process that was very likely led by acharyas, or ritual specialists.

In the same way as the Skandapurana constructed an imagined landscape for the Pashupata across northern India, a branch of the same community was legitimizing their presence in Ekamra through the construction of its ritual space.[15] Among the rulers mentioned in the Skandapurana is Shashanka, a king that ruled over Gauda (ca. contemporary Bengal) in the first half of the seventh century, whose territory branched south along the Odishan coast. Ekamra’s sthalapuranas, ritual texts that described and codified the pilgrimage site in later centuries, all credit him with the construction of a stone temple to Shiva in the city.[16] Shashanka’s patronage may have spearheaded the intense building campaign through which the forest hermitage quickly grew into an important pilgrimage center. However, this process likely involved a broader community of donors including laymen, merchants, and pilgrims. I argue that it is the latter, itinerant lineages traveling through Ekamra’s far-reaching routes, that turned the nascent hermitage into a ritual space and center of learning for Shaiva and Shakta lineages.[17]

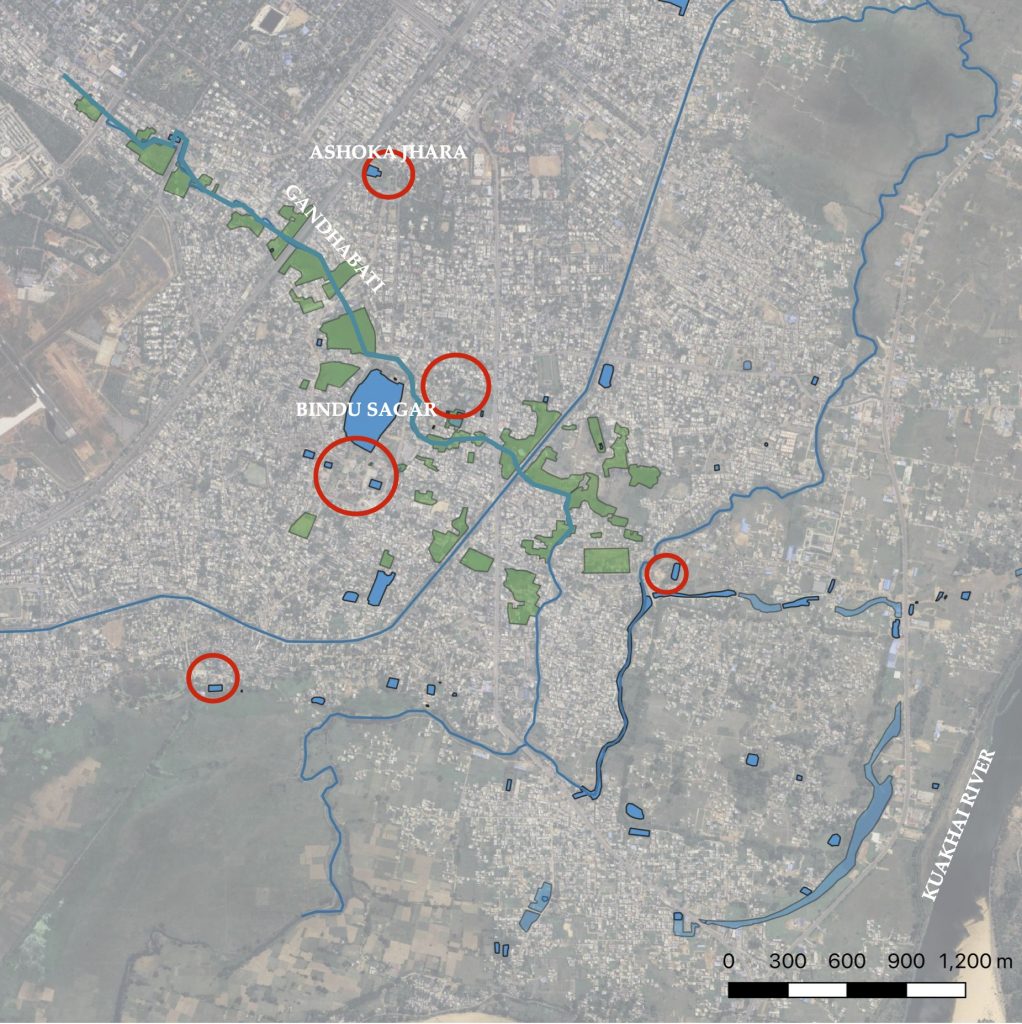

Fig. 2. Ekamra’s earliest built sites, in red, were established around water resources and natural pools such as the Bindu Sagar. Waterlogged areas, highlighted in green, show the presence of ground water moving northwest to southeast towards the Kuakhai river. (Map data: Google, ©2025 Airbus, Landsat / Copernicus, Maxar Technologies).

Besides its location on travel routes, Ekamra’s ecology also made it suitable for the establishment of a hermitage. The site had a reliable local water basin, nourished by the Gandhabati stream and by abundant ground waters, emerging in floodplains and waterlogged areas (Fig. 2). These emerging ground waters fan out in a triangular shape from the northwest to the southeast, towards the Kuakhai river. While flowing towards the river, they gathered centrally in the basin of Ekamra and surfaced in natural pools. Early communities intervened on these sites of natural water collection, digging further into the soil and adding containment walls and steps. In this way, they created functional access points to water and helped water drainage, reclaiming fertile farmable landscape from what would have been marshy land.[18]

The site was surrounded by a gajavana, a dense “elephant forest” that provided the relative isolation required for renunciant practices.[19] In early environmental classifications, gajavanas were anupa, rainforest-like ecologies, marshy and abundant in water, in contrast to the jangala, a much drier savannah.[20] The wild elephant populations that characterized these environments can be reliably used as indicators of vegetation density and water resources. Because elephants have delicate skin, they need a dense forest cover to shelter from the sun. They consume considerable amounts of food and water: a single adult will eat around 350 pounds (150 kg) of vegetation and drink between twenty and forty gallons of water per day. They gather in herds which continuously roam in search of food, covering an average of 100 square miles (250 sq km) daily.[21] Wild elephants were an important resource for rulers who hunted and captured them to bolster their armies. These animals’ massive impact on the environment was the reason why historically they were captured as adults rather than raised in captivity. Early kings, then, placed great value on the maintenance of extensive and plentiful gajavanas.[22]

Fig. 3. The earliest temples in Ekamra were arranged as a series of clusters or settlement nodes. Two were more central, just northeast and southwest of the Bindu Sagar, and three were around one mile to the north, southeast and southwest. (Map data: Google, ©2025 Airbus, Maxar Technologies).

The first temples of Ekamra formed a dispersed, granular settlement that carefully negotiated the site’s physical geography and preexisting routes. A first set of temples, at least five, were built in the immediate vicinity of the Bindu Sagar. While not directly on the shore, they were within 200-300 meters (700-1000 feet) or a few minutes’ walking distance (Fig. 3). Remembering that this was the most waterlogged area of the site, it is understandable that stone monuments were built away from the water. Temple sites also avoided the area southeast of the Bindu Sagar, where ground waters fanned out towards the river. Therefore, the temples gathered in two separate areas around this central waterlogged ground. A second set of temples, six in total, were placed on a wider ring around the reservoir, creating a series of clusters around 1.5 km (one mile) away. The clusters were located in correspondence of natural springs or pools, and also connected Ekamra to landscape routes. The early settlement, then, was a series of nodes that we can envision as hermitages with two or three temples each. While each node or cluster of temples may have been relatively isolated in the lush vegetation, together they constituted the tirtha or pilgrimage site of Ekamra, which was identified in its waters and thus embraced the whole area.

The character of inhabited wilderness of the initial settlement may have been similar to other early monastic and ascetic sites of the Indian subcontinent. Cave sites on the Western Ghats offer useful comparisons. These communities, similarly to Ekamra, were strategically located on important through-ways between the interior and coastline, and with direct access to a water source. Sites such as Elephanta, Ellora, and Aurangabad, contemporary to this early moment of Ekamra’s history, also offer examples of diffuse ascetic communities whose construction was not completely tied to dynastic patronage, but to which dynasties did contribute.

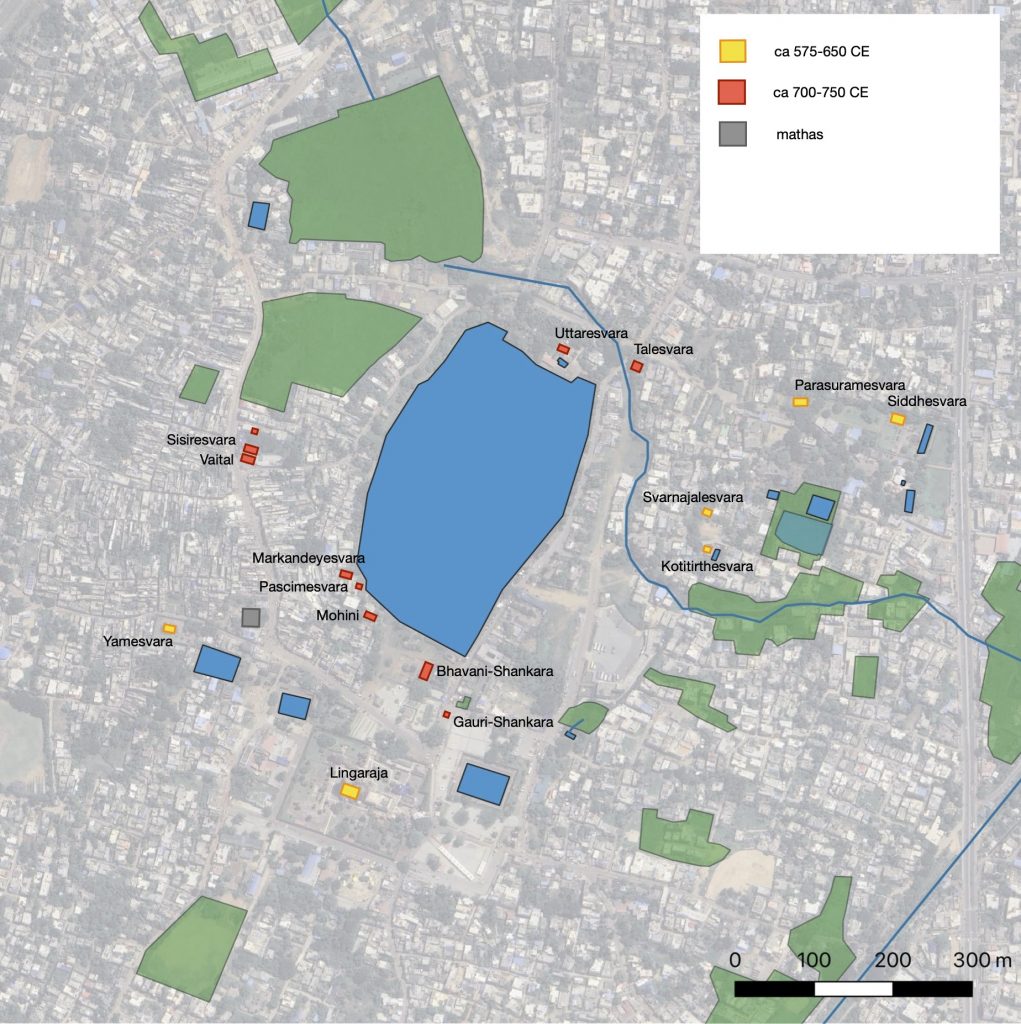

Fig. 4. Sixth to eighth century temples around the Bindu Sagar. (Map data: Google, ©2025 Airbus, Maxar Technologies).

Of the two nodes closer to the Bindu Sagar, the one to the south may have already been the central focus of Ekamra. The Lingaraja temple is a reconstruction of the shrine built by Shashanka. It marked one of the main sites of spiritual potency of the hermitage, the site where according to local myth Shiva first established himself in the forest as a svayambhu lingam, a rock formation that embodied his presence in the landscape. A second ritual focus was defined in the eighth century, when a ring of new temples was built around the Bindu Sagar, Ekamra’s central water reservoir (Fig. 4). Eighth-century temples established internal connections between the two temple clusters and reservoir at the center of Ekamra, gathering the different nodes of the hermitage into an articulated but unitary system, and constructing a ritual experience which still today constitutes the core of the old city.

Ekamra’s sthalapuranas, dating centuries after the temples were built, echoed the establishment of this sacred landscape through mythological narrative.[23] According to this textual tradition, Shiva left the crowded pilgrimage center of Varanasi and retreated to the forests of Ekamra. Here he created the rock formation of the svayambhu lingam, his direct embodiment. He also provided natural water resources by stabbing the ground with his trident and letting water emerge. The texts used narrative conventions common to locality-specific mythologies. We can recognize the trope of the deity miraculously procuring water by piercing the ground, the reference to spiritual potency through the synthesis of broader sacred geographies, and the connection to other pilgrimage centers. These textual codifications integrated local myth with pan-Indian ritual narratives, establishing in this way Ekamra’s sacred landscape in the complex pilgrimage networks of early medieval India. The texts, however, also reflect the process through which the forest is made into an inhabitable space, marked by a spot for worship and water to sustain it. The sources of spiritual potency of Ekamra, connected to Shiva’s embodied presence, were architecturally arranged between the sixth and eighth centuries to constitute the structure of the early settlement.

The Pashupata temple

Fig. 5. Seated ascetic engaged in prayer and meditation, with yogapatta and mala or prayer beads. Front hall of the Parasuramesvara temple.

The Pashupatas were ascetic practitioners whose refusal of social norms and devotion to Shiva led them to inhabit extra-urban spaces.[24] As they built their forest hermitage, they illustrated themselves among temple reliefs. Representations of forest sages in Ekamra display them engaged in a number of different practices, including dance rituals, meditation, and worship. On the Parasuramesvara temple, built in the first decades of the seventh century, an ascetic engaged in tapas (spiritual austerities) is carved on the west and north faces of the front hall or jagamohana (Fig. 5). We see his bearded profile and matted hair held up by a cord. He is seated on a low stool and his legs are held close by a yogapatta or strap. His left arm rests on his knee, while the right is raised holding prayer beads. He is engaged in mantra recitation, seated in a crouching posture which would have created heat through the restriction of the legs towards the abdomen.

Fig. 6. Parasuramesvara temple. View from southwest corner.

The Parasuramesvara not only includes depictions of ascetics, as is the case for many temples in Bhubaneswar and elsewhere, its complete program also suggests that the Pashupatas used temple reliefs to convey specific aspects of their doctrine, and to communicate their own identity by depicting sectarian rituals (Fig. 6). While important as a rare example of an early and completely intact temple, the Parasuramesvara’s asymmetrical double entrances, the fact that it had been restored, and the lack of a framework for its early iconographic program presented particular interpretive problems for art historians.[25] This temple’s sculptural program is, in fact, consistent with the architectural language of the emerging lithic tradition, seen in other experiments with arrangements of chaitya arches in Nagara aedicular systems dating back to the fifth century.[26] Figural and narrative reliefs, on the other hand, reflected the intent of its Pashupata patrons. The main icons are depictions of Shiva’s different aspects, coinciding both with Pashupata doctrine and with programs at other sectarian hermitages including for example the Dashavatara cave in Ellora. Other deities, such as Parvati and Ganesha, are accompanied by symbols that connect them to yogic practice.[27] Besides these main icons, secondary icons and scenes in early temples purposefully reflected the environment of the forest hermitage. On the Parasuramesvara, sages and yogis are shown performing rituals, while other scenes depict the vegetal life and herds of wild elephants that formed the background of the temple. Finally, semi-divine flying creatures and humanoid snake kings illustrated a forest that was not just a physical space but a spiritual one.

The real and the spiritual were made to intersect on the temple, grounding sacred space in the experience of place. Deity icons in South Asian traditions contain the gods’ embodied presence and for this reason can support a direct interaction with the devotee through an exchange of gaze.[28] In the same way, secondary icons, narrative scenes and details may have brought to life the entourage of the deity, and reproduced in stone their celestial abode.[29] In Ekamra, temple reliefs reimagined the surrounding wilderness and its powerful water landscape as animated by spiritual potency by illustrating it as inhabited by deities and semi-divine creatures.[30]

The iconographic program of the Parasuramesvara temple reflects a layering of popular and esoteric doctrines and ritual that facilitated two depths of ritual performance. One was devotional, directed at the devotee circumambulating the structure, exchanging darshana (ritual gaze or sight) with the deities, praying, offering flowers, incense or candles. The other was esoteric, exclusive to the ascetic community. Doris M. Srinivasan has for example suggested that the sequence of head, bust, and fully manifest deity that adorns the tower of the Parasuramesvara from top to bottom is a “theological exposition on the progressive unfolding of the body of Shiva” as expressed in medieval Shaiva agamas (sectarian texts).[31] These complex philosophical concepts, however, were hidden in the tower reliefs. What was in front of worshippers’ eyes as they circumambulated the temple was instead a sequence of beings with which to establish a much more direct relation.

The two entrances to the Parasuramesvara may also indicate a double ritual focus. The two doors are located on the rectangular hall in front of the main shrine of the temple (Fig. 6). On the eastern side, a central doorway is flanked by two grilled windows. A second doorway is located asymmetrically on the south wall, closer to the shrine. This arrangement is similar to the double entrance and double axiality of the cave temple at Elephanta.[32] At Elephanta, the double axis established two distinct yet interconnected paths for approaching Shiva. Whereas one led to a sanctum housing a lingam, the most powerful symbol of undifferentiated potential, the other directed the worshipper towards a three-headed bust of Shiva (Sadashiva), evoking the first stage of emerging consciousness. In writing about the Elephanta temple, Srinivasan noted that the status of both these two foci as venerated icons was reinforced through the presence of flanking guardian figures. The many large images filling the rest of the temple’s interior walls were simply murtis, images of the deity involved in divine play. They do not have guardians because “they no longer relate to the mystery of the divine unfolding.”[33]

Fig. 7. Gajalakshmi icon, where the goddess Lakshmi is lustrated by two elephants. Lintel of the western doorway of the Parasuramesvara temple.

Fig. 8. Ganesha icon, seated on mat, with background of monsoon clouds. Lintel of the eastern doorway of the Parasuramesvara temple.

Fig. 9. Three-headed bust of Sadashiva. North side of the front hall of the Parasuramesvara temple.

Reliefs surrounding the Parasuramesvara’s two entrances build on these two approaches to the temple. The visual program of the west-facing door, which lies on axis with the sanctum and linga, is consistent with the iconography of temple entrances, with the auspicious goddess Gajalakshmi sitting at the center of the lintel and the two river goddesses positioned as guardians at either side (Fig. 7). By contrast, the second, south-facing entrance may have marked a more esoteric approach. On the lintel is the elephant-headed god Ganesha, an iconographic configuration that identifies monastic establishments. In this specific example, Ganesha is shown sitting on a woven mat, referencing seated practice (Fig. 8). This second doorway aligns not with the main linga but, as at Elephanta, with an icon of Sadashiva positioned on the north wall of the jagamohana (Fig. 9). As a representation of Shiva’s first stage of manifestation, Sadashiva belonged to the realm of esoteric, meditational practice rather than devotional ritual.[34]

Fig. 10. Depiction of linga puja, with ascetics offering garlands and fire to the linga. West facade of the Parasuramesvara front hall.

The devotional nature of the western entrance was reinforced through the imagery surrounding the doorway. Represented in a relief just above and to the left is the ritual of linga puja, or the making of offerings to the main icon (Fig. 10). The relief shows devotees and semidivine beings bringing food offerings and acknowledging the deity with their hands in anjali mudra, palms joined together in front of the chest, while sages adorn it with garlands and perform arati, an offering of fire performed by waving a lantern with circular movements. The linga is still worshipped daily in this way. It is washed and dressed with flowers, and after the arati is performed, the lit flame is left on the entrance to the sanctum.

Fig. 11. Window grille on the west facade of the Parasuramesvara. Located on the north side of the door.

Fig. 12. Window grille on the west facade of the Parasuramesvara. Located on the south side of the door.

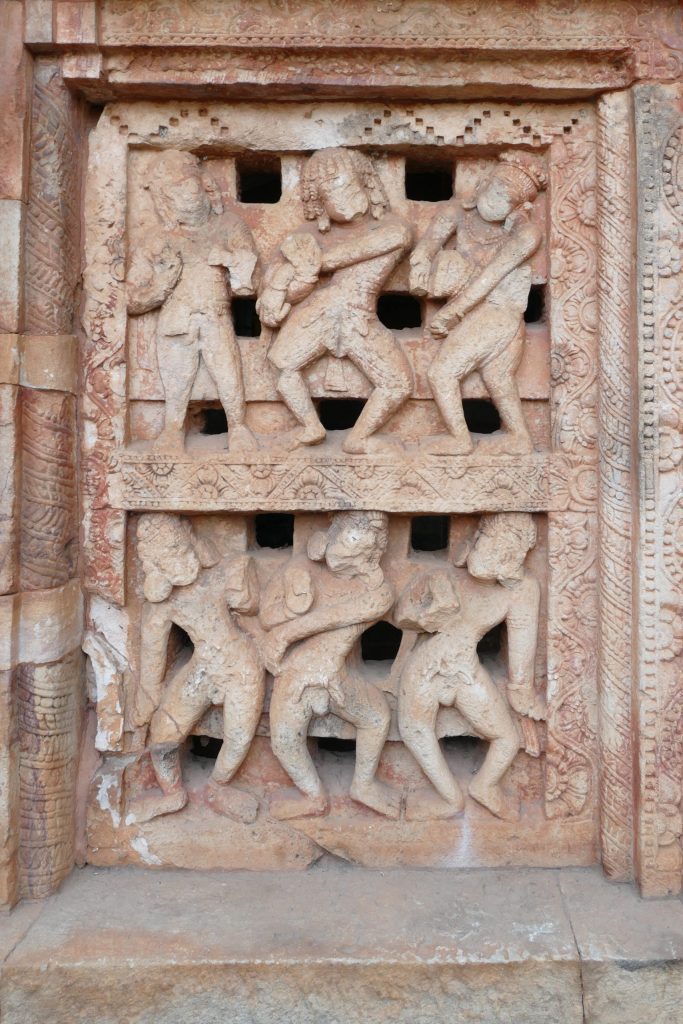

Another set of reliefs, located on the two grille windows that flank the door, may highlight dance ritual as one of the central forms of worship associated with Pashupata ascetics (Figs. 11 and 12). In his study of two texts associated with the Pashupatas, the Pashupatasutra and the Ganakarika, Charles Collins lists dance as one of the six forms of performative rituals that Pashupatas should enact within a temple. Altogether these include wild laughing, singing, a dance that “consists of [all possible] motions of the hands and feet: upward, downward, inward, outward and shaking motion,” making a bellowing sound, internalized meditative worship, and prayer.[35] It is notable that the reliefs adorn not the sanctum but the congregation space of the jagamohana.[36] Previous scholarship hasn’t contextualized or interpreted the reliefs. Indologist Charles Louis Fabri suggested in his volume on the art of Orissa that this imagery might represent performers of “some ancient form of dancing not known to survive in this shape to the present day.”[37] He only cursorily mentions the Parasuramesvara panels, and spends more time describing a similar panel affixed on the Kapilesvara temple, where he interpreted the snarling expressions of the dancers as masks, and their jeweled headdresses as “tinsel crowns, reminiscent somewhat of the large crowns of present-day Kathakali dancers.”[38]

The fearsome expressions of some of the dancers on the grille reliefs contribute to the iconography of a ritual that involved a congregation of initiates, the Pashupatas, whose aim was to ultimately achieve closeness, and even likeness, to Shiva.[39] The lower two registers of the Kapilesvara grille show snarling fanged creatures (Fig. 15). The upper register shows three seated figures with a central symmetry focused on a cross-legged figure with a yogapatta, possibly a religious leader or guru, raising a scarf in an impossible arch above his head. All figures in the upper two registers wear crowns and jewelry, the middle register only adds a second jeweled belt. The dancing figures also have a scarf, draped around their shoulders and undulating with the dance. On the Parasuramesvara windows we see the same kind of activity portrayed, only without seated onlookers (Figs. 11 and 12). The relief to the south of the doorway shows two registers, one with dancers and one with musicians. In the window to the north, only two musicians flank the central figure in the upper register, all others are dancers. The attire is the same, with jewelry, crowns, and scarves that wrap and float around the dancers’ arms.

Fig. 13. Detail with dancer, from the south window grille of the Parasuramesvara.

The movements and positions suggested by these reliefs are the same shown in the icons of Shiva performing his tandava dance, frequently found on Pashupata temples in Bhubaneswar. The importance of this icon is conveyed by its position on the vajramastaka on the entrance-facing side of the tower.[40] We recognize in the window grille reliefs the arm crossing the body diagonally, with the opposite hand rising to touch the forearm, reminiscent of the abhaya mudra and gajahasta in depictions of dancing Shiva. The dance is not synchronized, all dancers have slightly different positions, with their feet slightly raised from the floor, possibly stepping or shifting their weight from one foot to the other. While later dance reliefs become ornamental motifs, here the dance’s physicality is evident. The movement is vigorous and grounded. With legs and spine bent, the dancers turn by torquing into the ground and keeping the same height. The dancer at the top left of the south window shows us an almost complete movement. (Fig. 13) His feet are crossed with the weight on the front one, as shown by the slightly raised right hip. The spinal column curves as his whole body turns following the feet.

Fig. 14. Detail with crouching figure, from the south window grille of the Parasuramesvara.

Fig. 15. Window grille on the Kapilesvara temple.

The crouching figure in the lower register of the southmost window may correspond to a vidusaka, leading us to interpret the jeweled dancers of the Parasuramesvara as initiates that, by following the path of renunciation, have achieved spiritual closeness with the deity (Fig. 14). Much smaller than the other figures, he is hunched and twisted, turning his face to confront the viewer directly. His ears are notably large, with conspicuously missing earrings. He wears a cap with three round tufts of hair. This curious figure has been identified by indologist and art historian Monika Zin as a vidusaka, a character from the Natyashastra that can appear in a jester-like role, meant to invoke ridicule in kavyas (Sanskrit court literature).[41] Through the Pasupatasutra we know that the Pashupatas’ dance had a connection to the Natyasastra, which confirms this identification.[42] In early Buddhist iconography, the vidusaka is often associated with narrative scenes that depict the leaving of worldly life in favor of asceticism.[43] He is shown holding his kutila, a bent stick, in his left hand, while with his right he makes sure we notice the sacred thread which identifies his as a Brahmin, just like the dancers above him. Unlike the other vigorous figures on the relief, however, he has not joined the ritual that leads to Shiva. He has not been bestowed the spiritual jewels which adorn the dancers. He remains sitting among the musicians, his small genitals hanging downward, deliberately contrasting with the ithyphallic depictions of Shiva on the temple.

Positioned at the devotional entrance, the dance reliefs may have had a didactic role, evoking for all worshippers, initiated and uninitiated alike, the dance ritual of the Pashupata ascetics. The reliefs depicted renunciant followers of Shiva at an advanced stage of practice. They are shown with jewels and crowns, symbolizing their nearness to the deities also represented on the temple. Their faces are contorted into fearsome expressions, as if the tandava dance had transfigured them into ganas, the horde of ghouls that forms Shiva’s entourage. This was a model to which worshippers of Shiva and new initiates could aspire, as opposed to the vidusaka which instead was an example of a bad practitioner, showing his Brahmin thread but bare of the spiritual jewels which can only be achieved through renunciation and ritual performance.

Nature spirits and the monsoon

Drawing from a rich tradition of nature spirits which embodied the life force of the landscape, temple reliefs may have echoed the lush foliage and rich waters that constituted the lived reality of the hermitage. As originally argued by Ananda Coomaraswamy, much of the decorative motifs of early Indian architecture directly or indirectly draw associations with water in a system of correspondences which includes rain and monsoon clouds.[44] Entangled with the iconography of water cosmology are anthropomorphic representations of the life force, or prana, which animates the landscape. Ganas are inhabitants of the underground, the fertile soil from which life can emerge. They are shown as squat, dwarfish figures, at times carrying the weight of the temple structure. Yakshis are female nature spirits that inhabit plants, trees, and bodies of water. Their graceful figures, sometimes shown in front of a tree and holding one of its branches, are noted in most surveys as beautifying the temple. Nagas or nagarajas, “snake kings,” are inhabitants and protectors of flowing waters, also associated with the underground and trees. They can be depicted as snakes, or as half-human but with a hood of snake heads and often a tail. These semi-divine beings populated the first temples in Ekamra, surrounding the imagery of deities and sages.

Fig. 16. The shrine of the Vaital temple is articulated through split pilasters containing alasa-kanya figures.

The imagery of yakshis and ganas often appears on temples as decorative motifs. However, outside the eighth-century Vaital temple yakshis occupied a prominent position. The rectangular shrine of the Vaital is modulated by pillars that split open, to reveal niches occupied by female figures (Fig. 16). These alasa-kanyas (an iconographic type which depicts female figures in various postures) have been praised for their harmonious depiction of the sensual female form.[45] Sensual and sexual imagery was present in early temples and gained ground from the eighth century, when mithunas, maithunas, and female imagery proliferate on temples accompanied by the deity Kama. However, two of the female figures on the Vaital temple are shown in association with a tree, holding its branch in a position that mirrors yakshi iconography from previous centuries. A third figure is not associated with a tree, but is smelling a flower. These iconographic details describe them as nature spirits, the life-force that allows vegetation to flourish, and the haloes that adorn their head still point to their semi-divine status. The yakshis are carved as large as other deities around the shrine, brought to participate fully in the ritual space of the temple.

Naga icons also populated Ekamra’s temples, part of an iconographic program that portrayed the natural landscape and tried to propitiate its power. Similarly to yakshis, snakes and snake-kings have long been the object of popular cult. In Bhubaneswar, the earliest naga icons predate the first temples and were themselves the object of worship.[46] In his study of the naga icons in Ajanta, Robert DeCaroli has argued that these figures’ proximity to gutters and cisterns reveals a reliance on supernatural forces as an aspect of water control.[47] This may have also been the case in Odisha, where nagas may have been called upon to help contain the ground waters whose levels rise considerably with the monsoon, and which were managed through the construction of cisterns since at least the first century BCE. For example, one Nagaraja icon dated between the eleventh and thirteenth century was found inside the Bindu Sagar reservoir, possibly a propitiatory offering to the waters or the embodiment of their spirit.[48]

Fig. 17. A sculpture of a naga king carved in the round.

Fig. 18. Naga sculptures were life-sized and placed in front of temple doorways as guardians. Example from the Svarnajalesvara temple.

Life sized sculptures of nagas were placed outside the doorway of some of Ekamra’s earliest temples.[49] Examples of these sculptures are located in the yard of the Muktesvara and may have originally been part of the preexisting Siddhesvara temple (Fig. 17). Another example is in situ next to the doorway of the Svarnajalesvara (Fig. 18). All have a human torso and head, covered by a snake hood. They are crowned and jeweled, and their expression is peaceful with a slight smile. Their hands hold a purnaghata, a pot overflowing with flowers and greenery, in front of their chest. They were just in front or attached to the entrance of the temple, possibly acting as guardians of the threshold.[50] The imagery of the vase of plenty adds some nuance, suggesting an act of worship to the deity in the temple and a reference to their own life-giving nature.

Figs. 19a and 19b (below). On the Svarnajalesvara temple, a naga king is part of the iconographic program around the north parsvadevata niche.

Fig. 19b.

Nagaraja icons also found space among temple reliefs.[51] In the Svarnajalesvara (early seventh century), a naga is placed on the top left corner of the north parsvadevata niche, housing Parvati. Although just a fragment remains, a snake hood and purnaghata are visible (Figs. 19a and 19b). On the eighth-century Sisiresvara, a naga is given a prominent position as one of the main icons of the jagamohana together with Kubera, another semi-divine being and king of the yakshas. The naga and yaksha sit in the side niches to the left and right of Lakulisha, a manifestation of Shiva favored by the Pashupatas (Fig. 20).[52] The Sisiresvara and Vaital were established next to each other in the same temple enclosure. They both brought to life yakshis and nagas, raising the inhabitants of the forest to participate in the temple program next to the gods.

Fig. 20. South face of the Sisiresvara temple jagamohana. From left to right, the main icons are the yaksha king Kubera, Lakulisha, and a nagaraja.

The vegetal life that is embodied on Ekamra’s temples was nourished by the local water basin and renewed yearly by the monsoon, a life-giving yet portentous event where natural forces take over daily life. The transition to the rainy season is accompanied by winds and lightning storms. As the rains advance, continuous flooding and rushing rivers can still make travel treacherous. For this reason, during the rainy season wandering renunciants ceased travel to seek refuge in hermitages, gathering as a community to consolidate lineages and transmit teachings. As the rains closed in, ascetics traveling through Odisha would have directed their steps towards sites such as Ekamra’s forest hermitage, the surrounding caves at Dhauli, Khandagiri and Udayagiri, or the monastic centers around Ratnagiri north of Cuttack, where they would have stayed until the end of the rainy season.

Figs. 21a and b (below). Eastern parsvadevata niche on the Parasuramesvara temple. Under the icon of Kartikkeya, a peacock is carved against a background of swirling monsoon clouds.

Fig. 21b.

In Ekamra, the monsoon and the resulting watery landscape is represented in the background of some of the early imagery, possibly evoking this specific moment in the life of the hermitage. This environmentally-specific content disappears in later iterations of the same icons, as temple programs became standardized. On the Parasuramesvara temple the monsoon is evoked in three scenes. The central panel of the Eastern door lintel shows the goddess Lakshmi lustrated by two elephants (Fig. 7). The elephants stand on two flowers of an abundantly proliferating lotus and are adorned with straps and bells. One of them raises its trunk to pour water over the goddess. The background of wavy lines shows us that, in fact, the entire scene takes place inside a pool of water. The second example can be found on the other door lintel. Around the icon of Ganesha, clouds gather to portend the coming monsoon that would have driven wandering ascetics to hermitages (Fig. 8). In the third example, monsoon clouds gather around the peacock vahana of Kartikkeya, situated in the east-facing temple niche (Figs. 21a and 21b). In other Kartikkeya icons in Bhubaneswar, the peacock functions as a seat for the deity or is placed under one of his feet. In this example, it is positioned independently in its own panel. The narrow frame is entirely occupied by the body of the bird, sinuous almost as the snake it has just captured. This tense encounter is, again, shown against a background of swirling, gathering monsoon clouds.[53]

Elephant reliefs

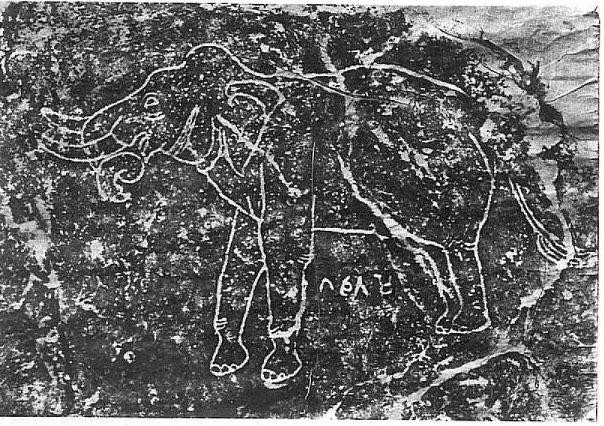

Fig. 22. Wild elephants above the entrance of one of the caves at Udayagiri.

The Ganesha and Gajalaksmi lintels on the Parasuramesvara continued a long iconographic tradition where the elephant is associated with water and a protective and purifying role. Elephants are present on the gateways at Sanchi and Bharhut, at Lomas Rishi a procession of elephants emerges from two makaras (crocodile-like mythological creatures) at the corners of the entrance arch. One of the caves at Udayagiri near Bhubaneswar also has a procession of wild elephants on its lintel (Fig. 22). These elephants signified celestial waters, and a devotee that crossed the threshold under them would have been, in a sense, cleansed. The same role will be later held by the icons of river goddesses.

To the symbolism of elephants in water cosmology, two additional layers of significance may be added. One had to do with the affective depiction of the surrounding ecology. Early temples showed the population of wild elephants either in scenes where they are roaming the wilderness, or in scenes of elephant hunt and capture, echoing the forested landscape of seventh century Ekamra, and how its human inhabitants related to it. The second has institutional connotations. The vast elephant populations of Odisha were an important military resource, and the hunt and capture panels in Ekamra point to rulers’ struggle for military dominance. This second significance became more closely tied to the figure of the ruler from the eighth century, as shown on the Vaital temple, and especially after the pilgrimage site of Ekamra became a dynastic center from the tenth century.

Fig. 23. Lotus rhizomes proceeding from the mouth of an elephant. Bharhut, second century BCE. (From Coomaraswamy, Yakṣas, vol. 2, plate 11. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives).

Fig. 24. Yakshi (nature spirit or nymph), identified as Culakoka Devata, with elephant vahana (vehicle). Bharhut, second century BCE. The deity and the elephant’s positions are parallel, they both embrace the tree allowing it to fruit. (From Coomaraswamy, Yakṣas, vol. 1, plate 4. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Libraries and Archives).

In the context of water cosmology, “sky elephants” also signaled the monsoon clouds.[54] The association is sensorial: the noise and destruction that the monsoon brings on its arrival is likened to a rutting elephant’s tearing through the growth, and both experiences may have been familiar to premodern inhabitants of Ekamra’s forests. It is also based on the elephants’ perceived virility, their seed equating water and its creative power with the same symbolism of the linga. As water and monsoon, sky elephants are depicted as life-giving, they sprout vegetation out of their open mouths, or are shown in association with nature spirits, in turn signifying the sap of flourishing vegetation and less directly the prana or life force that animates the manifest world (Figs. 23 and 24). Rutting elephants also produced liquid from their temporal glands, an additional water-producing character that became a trope and is sometimes indicated in imagery (Figs. 23, 25, and 26).[55] Consider a description of Indra’s elephant vehicle Airavata, from the Ramayana: “[…] Indra mounted the four-tusked lord of elephants, which resembled a peak of Mount Kailasa. It was streaming rut fluid, bearing ornaments, lofty, and loud with the sound of its golden bells.”[56] Airavata’s size, his tusks, and his rutting fluid associate water-making qualities with markers of virility.

Fig. 25. Carving with elephant in musth on the north face of the Ashokan rock edict at Kalsi, Dehra Dun, third century BCE. (From Hultzsch, Inscriptions of Asoka, 50).

Fig. 26. Gajalakshmi with elephants in musth. Detail of eastern gateway, Great Stupa, Sanchi, first century CE. (Photo by John C. Huntington, Courtesy of the John C. and Susan L. Huntington Photographic Archive of Buddhist and Asian Art).

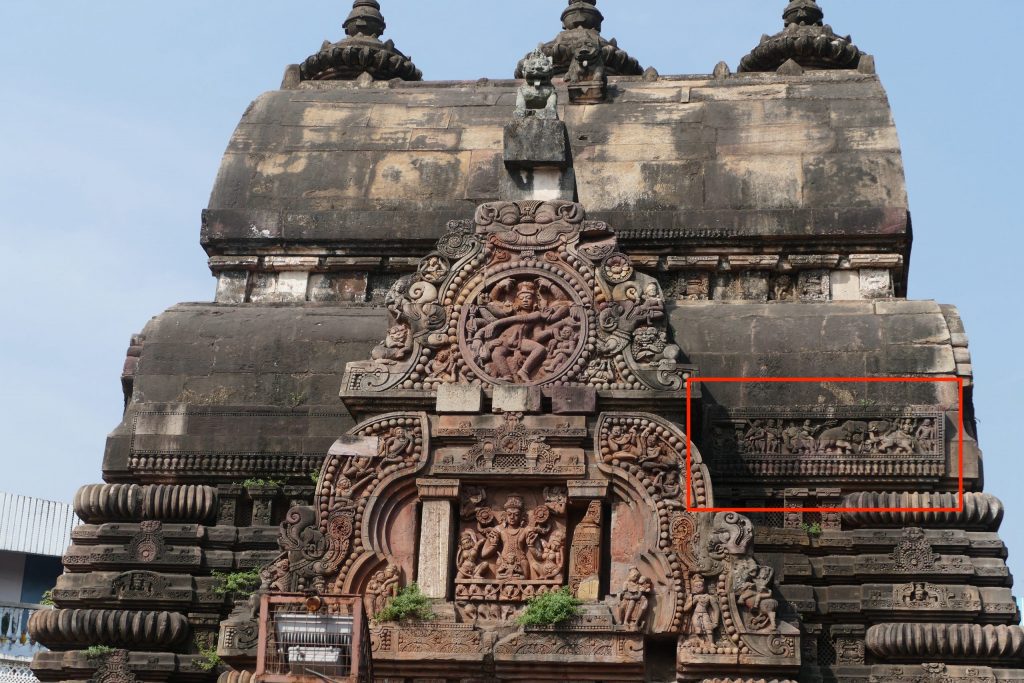

Premodern rulers were quick to claim this association for themselves. Elephant imagery is an important signifier of kinship and military power. This is the case for example in scenes of elephant processions, or as part of decorative motifs representing the fourfold Indian army, with cavalry, chariots and foot soldiers also part of the decorative program. Elephants are also prominently featured in depictions of hunts, showing warrior figures involved in the capture of elephants deep in the forest. Whereas the significance of the elephant in water cosmology and military warfare has been amply explored, the imagery of the hunt in early medieval India hasn’t been looked at quite as closely. In previous surveys of Bhubaneswar a vast range of imagery, from standardized motifs to content-rich scenes, has been summarized as “elephant reliefs” or “elephant hunt reliefs,” and cursorily mentioned as part of the collection of decorative motifs on the temple.[57] A closer analysis offers more nuance. On tenth to thirteenth-century temples elephants were included as decorative bands or motifs, with only slight variation in the overall repetitive imagery. Later reliefs also include elephant processions in the context of dynastic patronage, as for example on the thirteenth century Sari temple and on the fifteenth century Kapali matha (Figs. 27, 28).[58] Sixth to eighth century temples, on the other hand, represented elephants through detailed narrative scenes where these animals are often shown as agents in the forest environment, interacting with humans and with each other.

Fig. 27. Elephant procession panel on the Sari temple.

Fig. 28. Elephant procession panel from the Kapali matha.

I suggest that not only do elephant hunt reliefs function as signifiers of military prowess, but they also evoke the setting of the forest as a remote space, one that lay beyond the ordered structures of the city and that was inhabited by powerful creatures with whom humans developed complex relationships. Hunt scenes appear on the earliest temples in Bhubaneswar, built at a formative moment in the city’s urban development. As humans began establishing their presence in this environment and carving out residential spaces, temple reliefs envisioned the wilderness of the elephant forest that surrounded the settlement and also human processes of trying to harness it, evoking a key transitional moment that saw the transformation of a forest hermitage into a budding pilgrimage town.

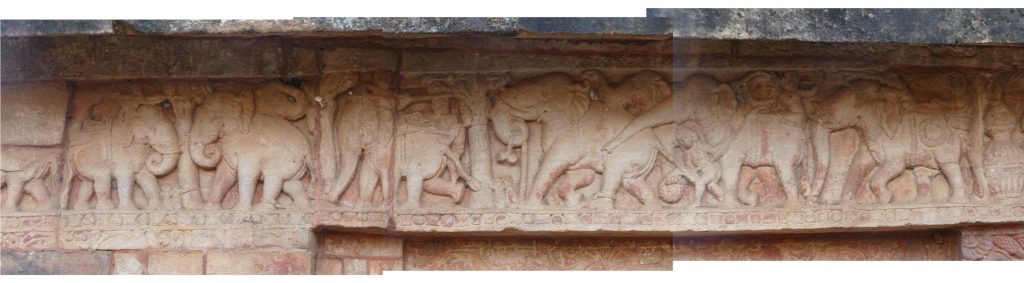

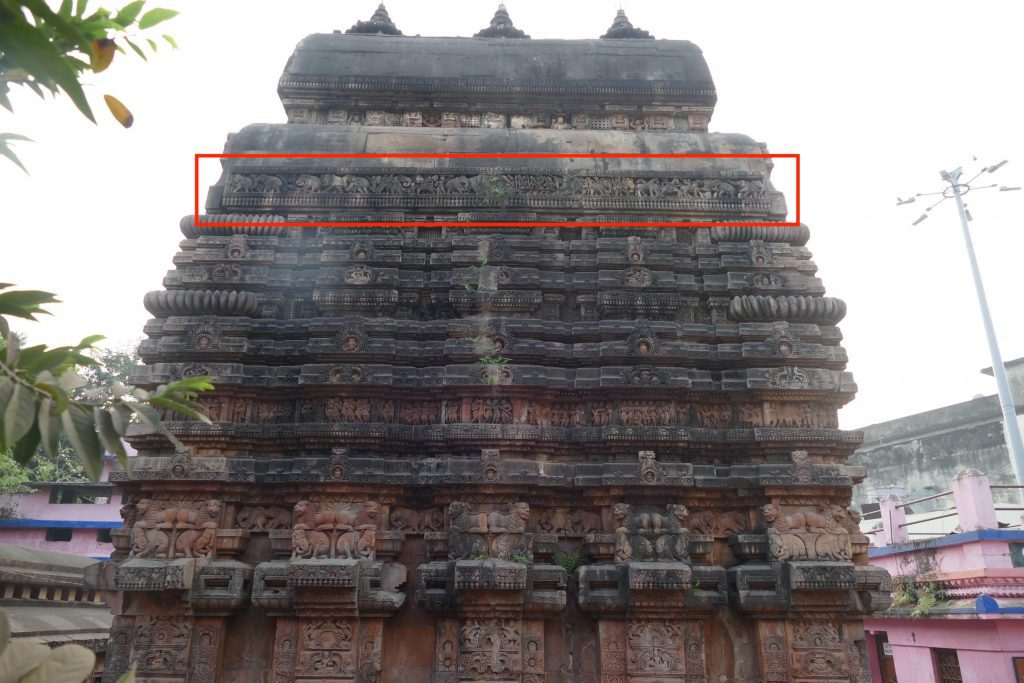

We find depictions of elephants in the forest in prominent positions in the decorative program of three very early temples, dating to the turn of the seventh century.[59] Two are on the Parasuramesvara. Of these, the first is located just above and to the left of the main entrance, the second serves as a lintel to one of the main niches. A third example is located on the lintel of the doorway of the Satrughnesvara temple. The location on or around the lintel is significant. These reliefs are close to eye level, anyone ritually circumambulating the temple will likely observe them as they are either just above the main icons or above the doorway. They also are in correspondence with the threshold, a space of ritual transition where elephants’ protective and auspicious qualities were already integrated in the iconography of Ganesha and Gajalakshmi. On the Svarnajalesvara, the elephant relief is a bit higher on the temple, on the southwest corner of the varandika frieze.[60]

Fig. 29. Elephant hunt relief on the west facade of the Parasuramesvara temple. Located above and to the left of the door lintel.

My first example is a complex and animated representation of an elephant hunt unfolding in a densely forested landscape, occupying a long panel just above the doorway on the west face of the Parasuramesvara temple (Fig. 29). It is worth noting that elephants were not hunted for sport, and that the hunt was not intended to be lethal. Rather, hunts like these were aimed at capturing adult elephants that could be put into human service. In this particular relief, a group of hunters is attempting to capture wild elephants in a forest setting, signaled by the numerous trees among which the action takes place. The hunters ride already domesticated elephants, identifiable as such by the harnesses made of cords and straps that wrap around their chest. There are two riders on each elephant, one of them sits in front, on the shoulders of the elephant, while the second stays toward the back, within reach of a coiled rope, and held by a simple rope harness. In the scene, we can see that the wild elephants have just been captured – although they do not wear harnesses, they have ropes wrapped around one of their rear legs. The second elephant from the left is in this way securely fastened to a tree.

We also see the struggle against this capture, as the second wild elephant towards the right has managed to get free. He has a rope around one of his legs, but is holding the other end of it with his trunk, having just ripped it from where it was tethered. His strength is depicted through his tusks: they are longer than the other elephants in the relief, indicating a powerful male bull that would have been a prized addition to the army. This elephant is causing some chaos within the hunt. We can see a human rushing to climb up one of the domesticated animals to seek refuge, while another hunter has jumped down from his mount and is sneaking up on the enraged elephant from behind.

Fig. 30. Elephant relief on the lintel of the Satrughnesvara temple.

Once captured, elephants needed to be tended and trained, often in forested areas in the outskirts of settlements. We see such an example represented in an earlier lintel relief in Bhubaneswar, found on the Satrughnesvara temple (Fig. 30). This lintel depicts a herd of already captured elephants being tended to by a human who appears to be an elephant trainer. The scene is animated. Towards the left two elephants are playfully interacting, turning toward each other, to the right two others appear to be grazing from a tree. Nearby, the elephant trainer struggles to guide a disobedient stray using his elephant goad. All of the elephants are marked distinctly as tusked males, suggesting that what we are seeing is the training of war elephants, which were often outfitted with blankets and bells. The elephant to the far right has a blanket on his back, indicating that this panel is not depicting a wild herd, but a group of tamed animals.

Fig. 31. Elephant hunt relief on the varandika of the Svarnajalesvara, located on the west corner on the south facade.

Fig. 32. Details of the Svarnajalesvara relief, with male bulls in musth.

Such domesticated forests were spaces where human-animal relationships could be safely cultivated. By contrast, in wild and undomesticated forests the potential for violence was always imminent in conflicts between humans and animals. A scene similar to the Parasuramesvara elephant hunt appears on the Svarnajalesvara temple (Fig. 31). The varandika frieze is here dedicated to scenes from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, important South Asian epics where a lot of the action is set in the expansive forested landscapes of premodern India.[61] The violent scene with rutting elephants on west side of the frieze on the south face of the temple is not part of epic narrative, but may be describing the forested setting of these Pan-Indian myths while at the same time referencing Ekamra’s ecology.[62] The panel shows a forest scene with hunters mounted on elephants and wild elephants in the state of musth. To the right, domesticated elephants with rope harnesses and riders enter the forest, where male rutting elephants are fighting. Moving towards the left other riders are directly engaging a tusked bull, and further to the left two wild elephants close the scene, with one of the elephants trampling a human. This relief is higher on the temple than the one on the Parasuramesvara, being further away from a visitor’s eyes its carving is deeper and simpler. Yet the elephants are carefully characterized. These are tusked males, pockmarks show the hair on their forehead, and in two of them it is possible to distinguish rutting fluid flowing from their temples (Fig. 32).[63] Similarly to the Parasuramesvara, the scene is interspersed with trees. In this example, they seem to mark a narrative rhythm. If so, reading the relief from right to left, following the direction of circumambulation, we might have a sequence of hunters entering the forest, encountering two rutting elephants, engaging with one of them, and losing the fight. The scene to the left might indicate an acceleration which pushes the tree in the background as elephants crowd together, their mass overwhelming the hunters and ultimately killing one of them.

Fig. 33. Hunt relief on the lintel of the north parsvadevata niche of the Parasuramesvara temple.

A second example from the Parasuramesvara temple also shows the forest as a dangerous space where the relationship between humans and nature could be tense and even violent (Fig. 33). On the left side of the relief we see hunters mounted on a domesticated elephant. The driver is holding an elephant goad while the person behind him has a bow in his hand. Just in front of them, another human is confronting a couple of wild elephants, a male and female, and pushing a spear directly into the chest of the male bull. The enormous strain of this action is shown by the figure’s crouching position, with his weight pushed on his back leg. The scene is mirrored to the right, where a rider on horseback is confronting a couple of large felines, possibly tigers or lions, and using a spear to kill one of them. The ferocity of the scene is reinforced by a vignette of a buffalo and her calf fleeing to the far right.

The combination of elephant and horse point to ancient army divisions, suggesting a hunt that has a military connotation. The warrior-like central figure might represent a ruler leading this attack on the forest. The scene also resonates with tropes of royal prowess as articulated in contemporary inscriptions. For example, a seventh century land grant from this region describes the king striking the chest of a large elephant with his weapon.[64] In early medieval Odisha, power was continually fluctuating as localized clans competed for control over the landscape.[65] Hunt reliefs may have celebrated kings’ virility and conquering power. In this context, the elephant not only served as foil for the king’s strength, it also signified the richness of the landscape that he is controlling. The hunt’s ability to signal military prowess was reinforced by its inherent violence. This is indicated by textual sources, including classic epics such as the Mahabharata, where kings enacted hunts with notable ferocity.[66] Describing one of these narratives, historian Romila Thapar writes: “Families of tigers and deer were killed, and severely wounded elephants trampled the forest. So fierce was the slaughter of animals that predators and prey took refuge together.”[67] We can notice these “families” of animals represented in the Parasuramesvara relief: the elephants and lions are shown as a couple of male and female, and the buffalo is escaping with a calf. Might we be looking at depictions of such ferocious hunts in these reliefs, or at allegories of sixth-century kings’ virility and power in battle? I suggest that these reliefs also evoke the forest as the lived environment that surrounded Bhubaneswar in the initial stages of settlement, an environment which humans inhabited not without conflict.

Fig. 34. Elephant hunt relief on the west face of the Vaital temple.

Figs. 35a and 35b (below). The elephant relief on the Vaital temple might unfold following the direction of circumambulation, from right to left.

Fig. 35b.

On the eighth-century Vaital temple, the connection between the elephant hunt and the king’s military power is made more explicit. We are shown a first relief with an army hunting wild elephants, while on the other side of the temple a second relief shows the resolution of this conflict: a captured elephant is overseen by the king himself. The first relief spans the entire length of the west facade but is located high on the temple, just below the vallabhi (barrel-vaulted) roof (Fig. 34). Towards the right and the left of the relief are two herds of wild elephants; trees separate them from a dense army of foot soldiers, cavalry, and mounted elephants. From right to left, a few scenes stand out. Elephants and hunters encounter and charge each other with raised trunks and spears (1), a hunter traps a wild elephant with a noose (2) and is then trampled (3) (Figs. 35a and 35b). The relief reworks earlier scenes from the Parasuramesvara and Svarnajalesvara and, like on the Svarnajalesvara, seems to present a sequence of events. Reading the relief from right to left follows the same direction followed by the elephant herd. This is also the order in which we encounter the images if we circumambulate the temple ritually, starting from the entrance and following a clockwise direction. We may be meant to follow the herd as it encounters humans at the forest boundary, enters into conflict, and reenters the forest to the left, entirely unscathed by the encounter.

Figs. 36a and 36b (below). Scene with captured elephant and king, on the east face of the Vaital temple, next to the vajramastaka.

Fig. 36b.

Following the direction of the first relief and continuing the circumambulation, we encounter the second relief at the same height on the front of the temple, to the right of the vajramastaka, the central projection on the temple tower. We may understand this as an epilogue to the first scene. The relief shows a captured elephant, with both his feet tied down (Fig. 36). The process of taming is fully in progress, we are not in the forest but in an enclosure, and the king is overseeing his new property from a pillared space to the left. Soldiers, mounted and on foot, guard the scene and are in the process of subduing the elephant by hitting him with tree branches, while the elephant is still strong enough to drag around a human desperately clinging to one of its tusks.

In the first relief, we are shown that the conflict between army and wild herds is on equal ground. The wild elephants of Ekamra’s forests are strong enough that even the ruler’s army has some difficulty capturing them. This only makes the military prowess of the ruler more evident, as we are shown in the second relief that he has still been successful in his conquest of these powerful animals. At the front of the temple, the king sits just next to the central projection of the tower, where Surya rides his fiery chariot and Shiva dances wildly. Picturing the ruler in this prominent position, the iconography points to a shift in the socio-political context behind temple construction which became even more important in later centuries as secular power became closely associated with religious institutions.

Conclusion

Fig. 37. Encounter between humans and a group of elephants bathing in a lotus pond. Detail from Rani Gumpha, Udayagiri, Bhubaneswar, first century BCE.

Bhubaneswar’s earliest temples show the interaction between premodern settled communities and the powerful ecology that surrounded them. It is possible to recognize in their reliefs a reference to the initial encounter between a human community and the wilderness that it was trying to settle. In the Rani Gumpha at Udayagiri, a complex cave site adjacent to Bhubaneswar and dating from the first century BCE, a relief illustrates an encounter between a group of humans and a group of elephants, both intending to bathe in the same body of water (Fig. 37).[68] This encounter is evidently traumatic for both parties, as the elephants panic and the humans throw bangles and clubs to scare away the small herd. Would similar encounters have also characterized Ekamra during the medieval period? Elephant herds may have visited the same natural pools of water that supported the early settlement, and may have been a common sight in the surrounding landscape.[69]

The dense decorative programs of Ekamra’s earliest temples indicate that the forest still constituted a lived ecology in the nascent settlement. Vegetal motifs surround the animated figures of nature spirits, representing plant life, the ground from which this emerges, and the waters which nourish it. The deities, the main images on the temples, are then surrounded by a depiction of a supernatural garden or forest, captured at the moment of its renewal, sprouting and flowering thanks to the rain. These decorative motifs are not specific to Bhubaneswar, but part of a broader cosmology of water that filled temples with images of vegetation and watery creation. In Bhubaneswar, however, they are accompanied by detailed and varied narrative friezes that expand on and more specifically qualify the significance of the forest and waters as site-specific affective presence.

Early temples depicted distant rulers and their hunting and conquering armies in the landscape, but were more concerned with representing the many ascetics and sages that populated the hermitage. As the Pashupata lineage was fashioning Ekamra into a pilgrimage center, through temple iconography they constructed a sacred forest inhabited by Shiva and his retinue, and through scenes of ritual worship they included their own lineage in this spiritually potent site. This seventh-century Pashupata hermitage was one of the initial outposts of human settlement. It developed in the following centuries into a powerful dynastic centre, then into the current metropolis and capital of the state of Odisha.

References

| ↑1 | Romila Thapar, From Lineage to State: Social Formations in the Mid-First Millennium B.C. in the Ganga Valley (Bombay: Oxford University Press, 1984), 37-38; Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya, Aspects of Rural Settlements and Rural Society in Early Medieval India (Calcutta: Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, 1990); Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya, “Historiography, History, and Religious Centers: Early Medieval North India, circa A.D. 700-1200,” in Gods, Guardians, and Lovers: Temple Sculptures from North India A.D. 700 – 1200, ed. Vishakha N. Desai and Darielle Mason (New York: The Asia Society Galleries in association with Mapin Pub, 1993); Romila Thapar, Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300 (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2003). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Three foundational texts on the temples of Bhubaneswar and Odisha are Krishna Chandra Panigrahi, Archaeological Remains at Bhubaneswar (Orient Longman, 1961); Vidya Dehejia, Early Stone Temples of Orissa. (New Delhi: Vikas, 1979); Thomas E. Donaldson, Hindu Temple Art of Orissa, 3 vols., Studies in South Asian Culture, v. 12 (Leiden: New York: E.J. Brill, 1985). |

| ↑3 | On placemaking and cultural landscapes in South Asia, see Kiran A. Shinde, “Place-Making and Environmental Change in a Hindu Pilgrimage Site in India,” Geoforum 43, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 116–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.07.014; Amita Sinha, “Cultural Heritage and Sacred Landscapes of South Asia. Reclamation of Govardhan in Braj, India,” in Asian Heritage Management Contexts, Concerns, and Prospects, ed. Kapila Silva and Neel Kamal Chapagain (London: Routledge, 2013). Also see David C Harvey, “Constructed Landscapes and Social Memory: Tales of St Samson in Early Medieval Cornwall,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 20, no. 2 (April 1, 2002): 231–48, https://doi.org/10.1177/026377580202000201; Catherine Brace, Adrian R. Bailey, and David C. Harvey, “Religion, Place and Space: A Framework for Investigating Historical Geographies of Religious Identities and Communities,” Progress in Human Geography 30, no. 1 (February 1, 2006): 28–43, https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132506ph589oa; Sonya S. Lee, Temples in the Cliffside: Buddhist Art in Sichuan (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2021). |

| ↑4 | Hermann Kulke, Kings and Cults: State Formation and Legitimation in India and Southeast Asia, Perspectives in History, vol. 7 (New Delhi: Manohar Publishers & Distributors, 1993). |

| ↑5 | As explained by Donaldson, the main icons are the most conservative ones on the temple, their iconographic detail and positioning remained relatively constant across centuries. Donaldson, Hindu Temple Art of Orissa, 5. |

| ↑6 | See Acharya Paramananda, “Ancient Routes in Orissa,” Proceedings of the Indian History Congress 18 (1955), 44–51. |

| ↑7 | See Dilip K. Chakrabarti, The Archaeology of Ancient Indian Cities (Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1995), 240-241. |

| ↑8 | In the periodization of urbanism in India, we can understand the earliest phases of Ekamra as landing in between the “early historical cities” of the Mauryan empire, and the successive “early medieval cities.” As laid out by scholars such as Romila Thapar, Dilip Chakrabarti and Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya. |

| ↑9 | Fragments of the stupa are kept at the Orissa State Museum. |

| ↑10 | Shaiva lineages encouraged conversion on the part of kings. The relationship served both parties as it legitimized kings’ power and provided religious communities with powerful donors. Alexis Sanderson, “The Saiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Saivism during the Early Medieval Period,” in Genesis and Development of Tantrism, ed. Shingo Einoo, Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series 23 (Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009). Bakker also suggests that, as Vaishnavism had been the official religion of the Gupta empire, subsequent dynasties may have turned to Shaivism as a reaction. Hans Bakker, The World of the Skandapurāṇa: Northern India in the Sixth and Seventh Centuries, Groningen Oriental Studies Supplement (Leiden: Brill, 2014): 4. |

| ↑11 | Elizabeth A. Cecil, Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape: Narrative, Place, and the Śaiva Imaginary in Early Medieval North India, Gonda Indological Studies, volume 21 (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2020), 3. |

| ↑12 | This text has been dated between the beginning of the sixth and the end of the seventh century. Bakker, The World of the Skandapurāṇa, 1-4. |

| ↑13 | “A central aim of the Skandapurana was to sanctify the landscape of northern India. Many of the myths, regardless of over how many chapters they extend, are geared towards a final section, in which what has been told is related to a specific locality. […] it could be maintained that the Purana is to a large extent a sequence of Mahatmyas, whose purpose is to legitimize and lend authority to local communities of the Śaiva movement in the sixth and seventh centuries, thus supporting them in their rivalry with other religious groups.” Bakker, The World of the Skandapurāṇa, 10-11. |

| ↑14 | Bakker, The World of the Skandapurāṇa, 10-11. |

| ↑15 | “By narrating the divine origins of the Pasupata movement as a series of events tied to prominent locales within a sanctified region, the SP authors created an imagined landscape. ‘Imagined’ is not an antonym for ‘real’, […]. The term […] draws upon a body of scholarship on the ‘social imaginary’ as the shared conception, ideals, or ethos of a particular group that reflects a certain normative perspective. These conceptions are expressed in non-theoretical or even tacit ways as shared images, narratives, and practices.” Cecil, Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape, 21-22. |

| ↑16 | Nothing remains of this shrine, as it was entirely rebuilt in the eleventh century in the Lingaraja temple, still the core of Bhubaneswar and object of interregional pilgrimage. |

| ↑17 | “A network of itinerant sadhus connected these centres, which became well integrated with the local religious infrastructure and developed into junctions within a fabric of yogins and religious teachers.” Bakker, The World of the Skandapurāṇa, 13-14. |

| ↑18 | Water management systems around Ekamra may in part have been established during Mauryan rule. Kharavela, who ruled during the first century BCE may also have contributed to the establishment or betterment of hydraulic projects in the area. On the antiquity of some of the reservoirs in Ekamra, see Panigrahi, Archaeological Remains at Bhubaneswar, 190. On Mauryan agrarian development, see Ranabir Chakravarti, “The Creation and Expansion of Settlements and Management of Hydraulic Resources in Ancient India,” in Nature and the Orient: The Environmental History of South and Southeast Asia, ed. Richard H. Grove, Vinita Damodaran, and Satpal Sangwan, Studies in Social Ecology and Environmental History (Delhi: Oxford Univ. Press, 1998). On Kharavela’s inscription, see Romila Thapar, Early India, 211-213; K.P. Jayaswal, R.D. Banerji, “The Hathigumpha Inscription of Kharavela,” Epigraphia Indica, XX, 1929-30, 71-89. |

| ↑19 | The dense forests of Odisha were described as gajavana in ancient sources such as the Arthashastra. See Trautmann’s overview of the textual material on the gajavanas. Thomas R. Trautmann, Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015), 30-31. |

| ↑20 | “Anupa describes all the places where water abounds, […] marshes but also rainforests, liana forests, mangroves, […]. The opposite is the jangala, defined first and foremost by a scarcity of water.” Francis Zimmermann, The Jungle and the Aroma of Meats: An Ecological Theme in Hindu Medicine (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1987), 4. |

| ↑21 | I draw these numbers from the Wildlife Trust of India website and publications, which describe modern elephant populations. Elephant herds today must contend with very fragmented environments. To gather the same amount of resources their home range can extend to over 1300 square miles (3500 sq km). “Right of Passage: National Elephant Corridors Project,” Wildlife Trust of India (website), last opened May 3, 2024, https://www.wti.org.in/projects/right-of-passage-national-elephant-corridors-project/. |

| ↑22 | On the historical correlation between rulers, elephants, and forest management in India, see Trautmann, Elephants and Kings. |

| ↑23 | Sthalapuranas are ritual texts that describe sacred sites, containing mythological narrative as well as instructions for worship. The texts exclusively dedicated to Ekamra are the Ekamra Purana, Ekamra Chandrika, Kapila Samhita and Swarnadri Mahodaya. All of them date from at least the thirteenth century, based on their mention of the Ananta Vasudeva temple built in 1278. The Ekamra Purana is the earliest, and later texts borrow verses and repeat much of the content. Pramila Mishra, Kapila-Saṁhitā (Delhi: New Bharatiya Book Corp, 2005), 230-231. See also Panigrahi, Archaeological Remains at Bhubaneswar, 22; Donaldson, Hindu Temple Art of Orissa, 5. |

| ↑24 | In Ekamra’s myths and iconography, Shiva is portrayed as a hermit, engaged in meditation and ascetic practices. Within the triad of Shiva-Vishnu-Brahma, Shiva is understood as the destroyer of worlds, with the other two personifying creation and maintenance. While Vishnu and Brahma uphold organized society and family life, Shiva is most often associated with asceticism and counterculture movements. He is often depicted as an ascetic and master of yoga, with long matted hair which he wears knotted on top of his head, and covered in the ashes of the cremation grounds. His iconography includes fear-inducing elements such as skulls and snakes, which also point to spaces of renunciation, extra-urban and thus considered “wild.” |

| ↑25 | The temple was reworked in the eighth or ninth century, and then restored in 1903. This contributed to a dismissive attitude in previous scholarship. However, the restorations carefully maintained the iconographic program, as visible in the restoration photographs. M.H. Arnott, Report with Photographs of the Repairs Executed to Some of the Principal Temples at Bhubaneswar and Caves in the Khandagiri and Udaigiri Hills, Orissa, India, between 1898 and 1903 (London: Waterlow, 1903), iii. See also Panigrahi, Archaeological Remains at Bhubaneswar, 65-66; Donaldson, Hindu Temple Art of Orissa, 52, 55-56. |

| ↑26 | An example of this is also found on the lintel of the sixth-century Satrughnesvara temple in Bhubaneswar. Aedicular architectural reliefs such as these have already been examined by Meister. See Michael W. Meister, “Prasada as Palace: Kutina Origins of the Nagara Temple,” Artibus Asiae 49, no. 3/4 (1988), https://doi.org/10.2307/3250039. |

| ↑27 | On a number of temples in Bhubaneswar Parvati is accompanied by both deer and lion, code for the peaceful environment of the hermitage. Ganesha is often shown with a yogapatta. |

| ↑28 | “The darśan, or gaze of the deity, is recognized as a primary means through which interaction with the divine may be conducted, whether through the beautiful decorations of the temple chamber, offerings of light, or simply eye contact with devotees. In short, the temple itself is understood as a sacred abode within whose boundaries performance and decoration are instrumental in effective interaction with the divine.” Robert DeCaroli, “‘The Abode of the Nāga King’: Questions of Art, Audience, and Local Deities at the Ajantā Caves,” Ars Orientalis 40 (January 1, 2011), 159. See also, Stella Kramrisch, The Hindu Temple (Calcutta: Univ. of Calcutta, 1946); Diana L. Eck, Darśan: Seeing the Divine Image in India, 3. ed, (New York, NY: Columbia Univ. Press, 1998). |

| ↑29 | Phyllis Granoff, “Heaven on Earth: Temples and Temple Cities in Medieval India,” in India and beyond: Aspects of Literature, Meaning, Ritual and Thought: Essays in Honour of Frits Staal, ed. Frits Staal and Dick van der Meij (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 170–93. |

| ↑30 | This has already been argued for other sites of asceticism from a similar early timeframe. In his analysis of the iconography of the Ajanta caves, De Caroli points out the importance of the decorative program. He argues that secondary icons such as nagas, semi-divine snake kings ubiquitous in early Buddhist iconography, may have given tangible presence to creatures that were seen as actively inhabiting the landscape. DeCaroli, 2011, 156-7. |

| ↑31 | Doris Meth Srinivasan, “Saiva Temple Forms: Loci of God’s Unfolding Body,” in Investigating Indian Art: Proceedings of a Symposium on the Development of Early Buddhist and Hindu Iconography, Held at the Museum of Indian Art Berlin in May 1986, ed. Marianne Yaldiz, Wibke Lobo (Berlin: Museum für Indische Kunst : Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, 1987): 335–47; Doris Meth Srinivasan, “From Transcendency to Materiality: Para Siva, Sadasiva, and Mahesa in Indian Art,” Artibus Asiae 50, no. 1/2 (1990): 108-142. |

| ↑32 | Ulrich Schneider, “Towards a Sculptural Program at Elephanta,” in Investigating Indian Art, ed. Marianne Yaldiz, Wibke Lobo (Berlin: Museum für Indische Kunst : Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz, 1987): 325–34; Charles D. Collins, The Iconography and Ritual of Shiva at Elephanta (State University of New York Press, 1988); Michael W. Meister, “Access and Axes of Indian Temples,” Thresholds 32 (2006): 33–35. |

| ↑33 | Srinivasan, “Saiva Temple Forms,” 344. |

| ↑34 | In two other biaxial temples belonging to Pashupata lineages, the sixth century one at Elephanta and the eighth century Lankesvara temple at Ellora, the image of Sadashiva is highlighted by its position directly in front of the main entrance. Srinivasan noted that in Elephanta this potent icon may have been concealed behind a screen. It is possible that the Parasuramesvara maintained the iconographical program but, in a smaller temple, hid the Sadashiva icon by placing it outside. See Srinivasan, “Saiva Temple Forms,” 343. |

| ↑35 | Charles D. Collins, “Elephanta and the Ritual of the Lakulīśa-Pāśupatas,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 102, no. 4 (October 1982), 614, https://doi.org/10.2307/601969. |

| ↑36 | The jagamohana served as a congregation hall and, as the reliefs suggest, possibly provided a space for the dance ritual of the Pashupatas. Reliefs from later temples suggest that ritual dance persisted in Ekamra and Odisha in later centuries, though modified. The spaces of the temple will become more specialized, and later forms of this ritual will take place is the natya mandapas, that served exclusively as dance halls. |

| ↑37 | Charles Louis Fabri, History of the Art of Orissa (Bombay: Orient Longman, 1974), 175. |

| ↑38 | On the Kapilesvara panel: “[…] the three vigorously dancing performers in the middle row have masks with fangs on their mouths, and what I take to be tinsel crowns, reminiscent somewhat of the large crowns of present-day Kathakali dancers. Equally clear […] is that the cymbalist and the three flautists and drummer are all, undoubtedly, in masks—an amazing document of some ancient form of dancing not known to survive in this shape to the present day.” He only briefly mentions the Parasuramesvara panels on page 125. Fabri, History of the Art of Orissa, 175. |

| ↑39 | Compare the interpretation of a seventh-century sculpture from Kafir Kot in northern Pakistan as either Shiva Mahesvara or a “transubstantiating sage.” Michael W. Meister, “Discovery of a New Temple on the Indus,” Expedition Magazine, 2000, 44; Michael W. Meister, “Crossing Lines: Architecture in Early Islamic South Asia,” 2003, 127. |

| ↑40 | The vajramastaka is a projection on the central portion of the temple tower, on the side facing the entrance. This centrally placed projection is a highly visible portion of the temple, with large reliefs that often communicate the temple’s affiliation through scenes and iconography related to its main deity. |

| ↑41 | Monika Zin, “The One Who Was Against the Pavvajjā,” in Sanmati: Essays In Honour Of Prof Hampa Nagarajaiah, ed. Luitgard Soni and Jayandra Soni (India: Sapna Book House, 2015): 437–47; Monika Zin, “About Visual Language, Drunken Women, Jesters and Escaping the World,” Cracow Indological Studies XXIV, no. 2 (2022): 91–116. |

| ↑42 | Collins, “Elephanta and the Ritual of the Lakulīśa-Pāśupatas.” |

| ↑43 | Zin, “The One Who Was Against the Pavvajjā.” |

| ↑44 | Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy, Yakṣas: Essays in Water Cosmology (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 2001). |

| ↑45 | Panigrahi, Archaeological remains at Bhubaneswar, 109-113; Dehejia, Early Stone Temples of Orissa, 69; Donaldson, Hindu Temple Art of Orissa, 101-102. |

| ↑46 | Panigrahi, Archaeological remains at Bhubaneswar, 209-210. |

| ↑47 | Robert DeCaroli, “Snakes and Gutters,” Archives of Asian Art 69, no. 1 (April 2019): 1–19. |