Emily Shartrand • Glendale Community College

Recommended citation: Emily Shartrand, “Don’t Judge a Book by its Cover: Picturing Girlhood in Medieval Inspired Children’s Literature,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/LWHX6724.

I was born in 1990 and have always been a voracious reader, particularly of fantasy fiction with a medieval spin (think kingdoms, dragons, knights, elves, and epic quests). My career as a medieval art historian can even be attributed to my bookworm beginnings. In college I wanted to learn about beautifully illustrated books, and the Middle Ages certainly had some of the best. From as far back as I can remember until about the age of twelve my parents took turns reading to me every night. My mother, as one might expect, read me new releases in children’s literature. My father, on the other hand, started me on J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit around age four. He read me books that he was interested in without much care for what was considered age appropriate, and they were all either fantasy or science fiction. I have a very distinct memory of asking him to define the word “ultimatum” as we worked our way through Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series. I could not have been more than eight.

As a result of my father’s influence, it is sometimes hard for me to grasp the nuances between the different reading levels in the publishing industry. What classifies a book as children’s, middle grade, teen, or young adult? How are authors, publishers, and illustrators targeting different ages and stages? And, what do they do when someone inevitably picks up a book that is technically not meant for them? I still read books that are not age appropriate. About a third of books I read last year were marketed to readers under the age of eighteen. I know I am not alone.[1] I learned about the existence of most of those books from other adult women on the #BookTok corner of TikTok.

Renaissance of Girly Girl Culture

As society emerged from the pandemic, cultural critics were writing about a collective return to girl culture. Between the ‘Barbie’ movie and Taylor Swift’s Era’s Tour, adult women were dressing up in pink, sparkles, and trading friendship bracelets.[2] In an article for The Cut Isabel Cristo argued that, “the fervid enthusiasm of grown women to participate in the veneration of girlhood raises a slightly unsettling question: What is it, exactly, that’s so uninviting about being an adult woman?”[3] Her answers were none too encouraging. Mainstream feminism was adrift, she argued. Some women were leaning back into traditional gender roles, sparking the “Tradwife” movement. Political events such as #METOO and the Dobbs decision were making many women “fucking miserable.”[4] Cristo saw girlhood culture as an opting out of thorny feminist politics, but writers and podcasters Emma Grey and Claire Fallon believe this premise contains a flawed assumption; “the idea that ‘girly’ things cannot be taken seriously.”[5] They argue that the adult concerns of feminism very often, “intrude into the lives of girls.” For them, a turn towards girlhood is an attempt, “to sort out which of our experiences of femininity are joyful and powerful and which are degrading.”[6] So, let’s follow their example and take the experiences of girls and girlhood culture seriously.

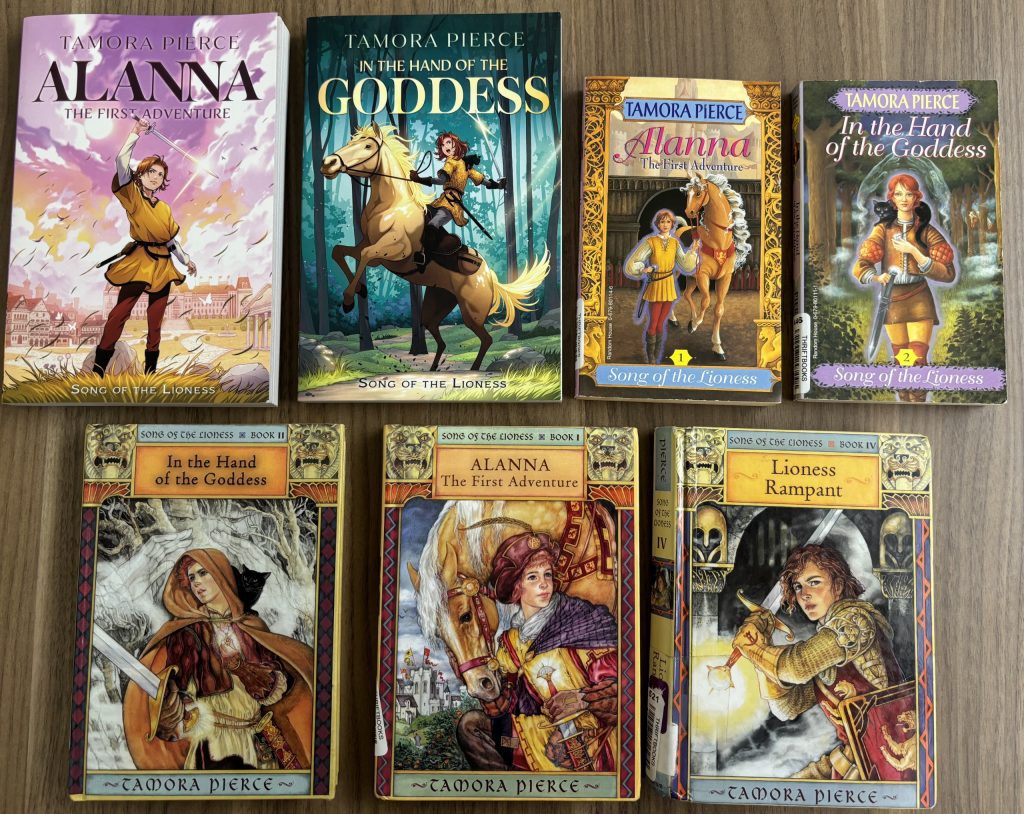

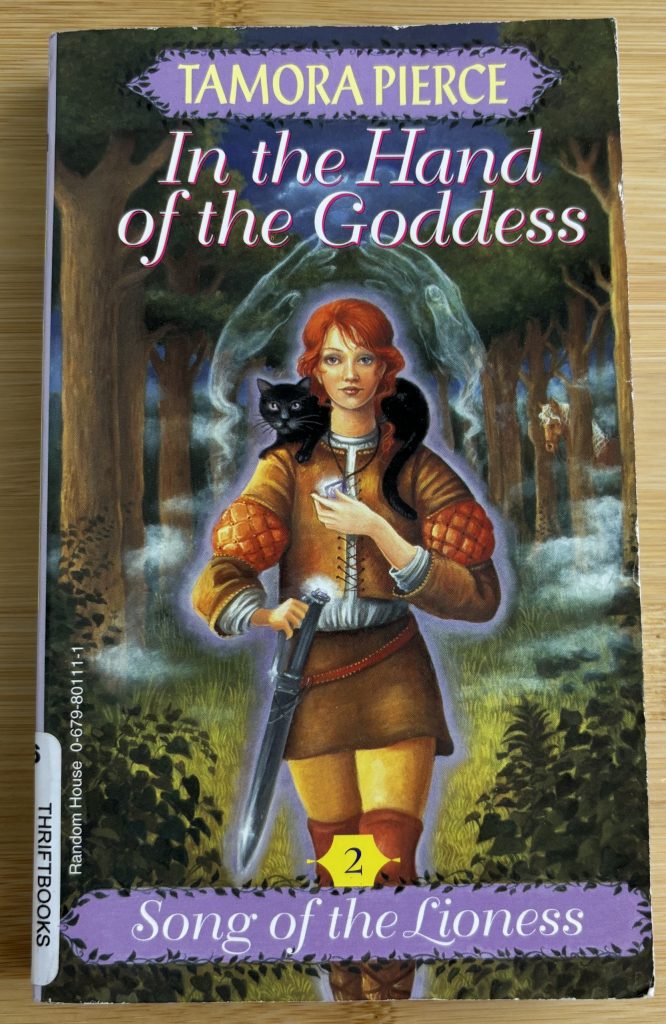

I want to reflect on three girl-centered, medieval, or medieval inspired fantasy novels from my own childhood that have either stayed popular or have made a resurgence in recent years. Alanna: The First Adventure was published in 1983 as the first book in Tamora Pierce’s ongoing Tortall Universe and has been reprinted with new cover art every few years since.

Fig. 1. Various editions from the Song of the Lioness quartet by Tamora Pierce, featuring cover illustrations by illustrators Yuta Onoda, Joyce Patti, and Marilee Heyer (top left to bottom right). Photo by author.

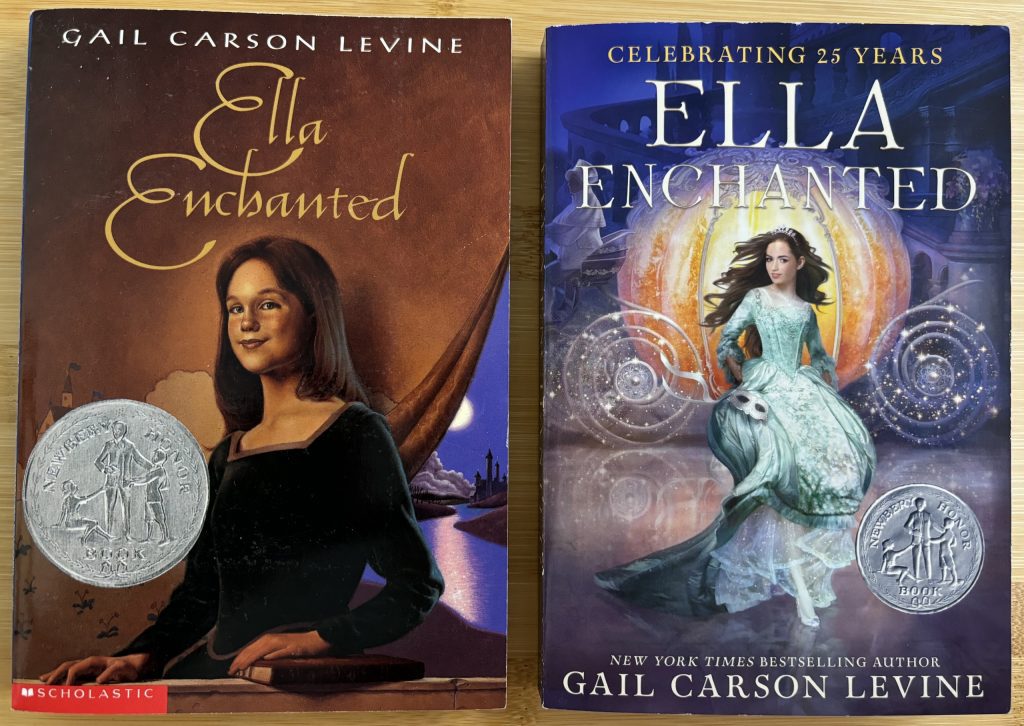

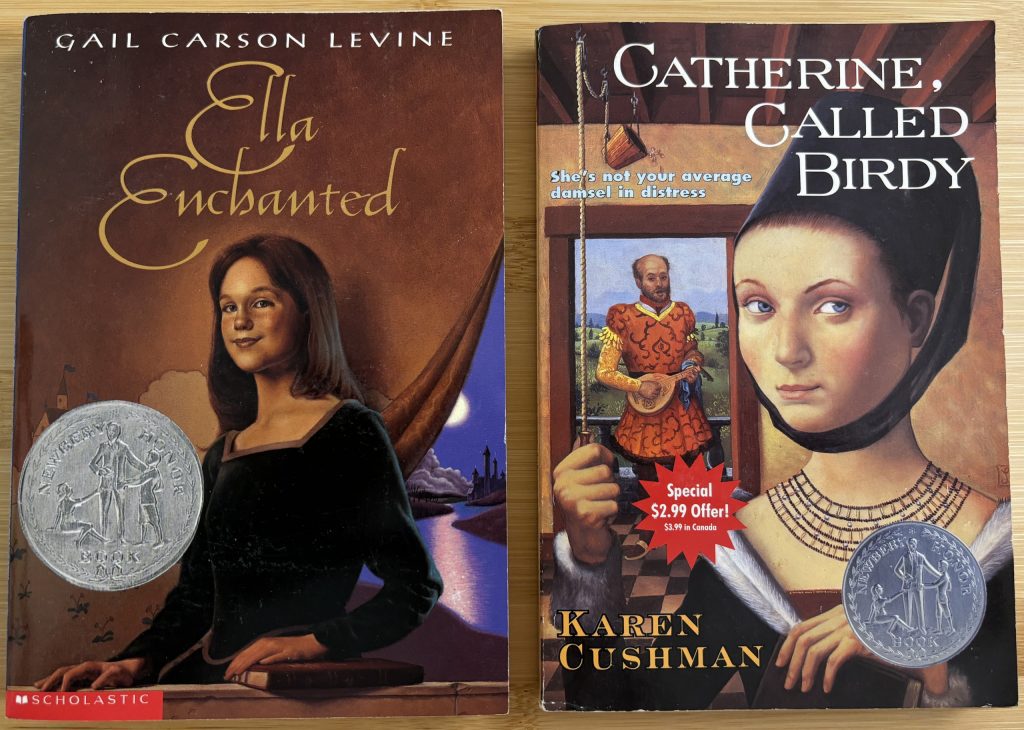

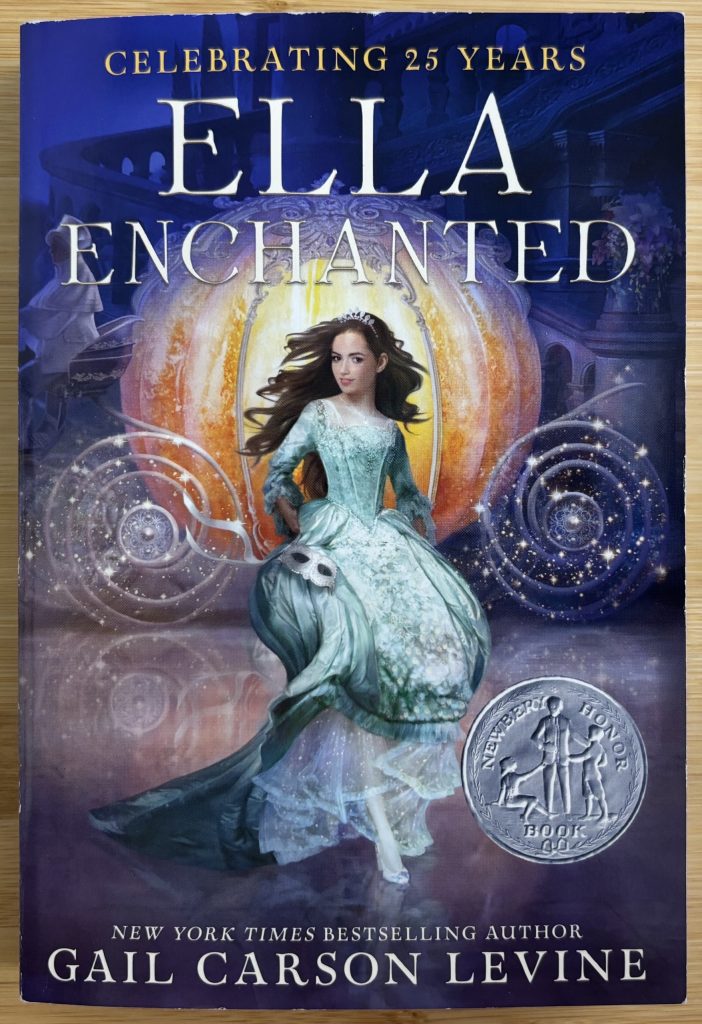

Gail Carson Levine’s 1997 Ella Enchanted was celebrated in a 25th anniversary edition in 2022 and was the basis of a 2004 movie of the same name.

Fig. 2. Left: Ella Enchanted, by Gail Carson Levine. Illustrated by Greg Call (HarperCollins, 1997).

Right: Ella Enchanted, by Gail Carson Levine. Illustrated by Lisa Keene (Quill Tree Books, 2022). Photo by author.

Fig. 3. Film still from Ella Enchanted, 2004 (Miramax Films). Screengrab by author.

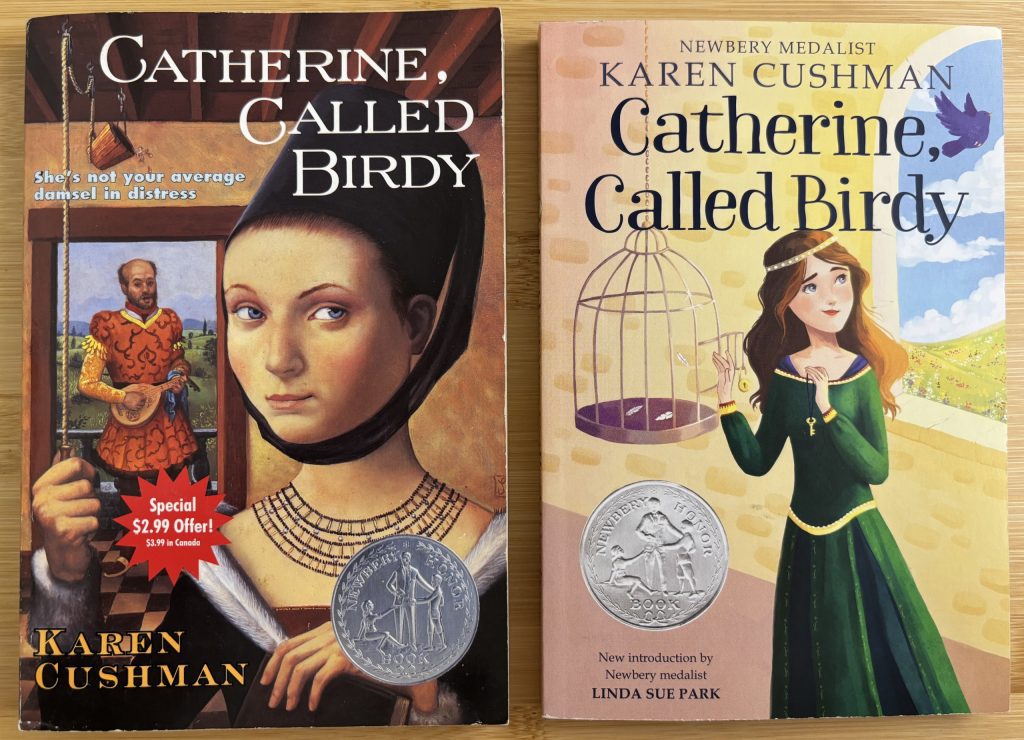

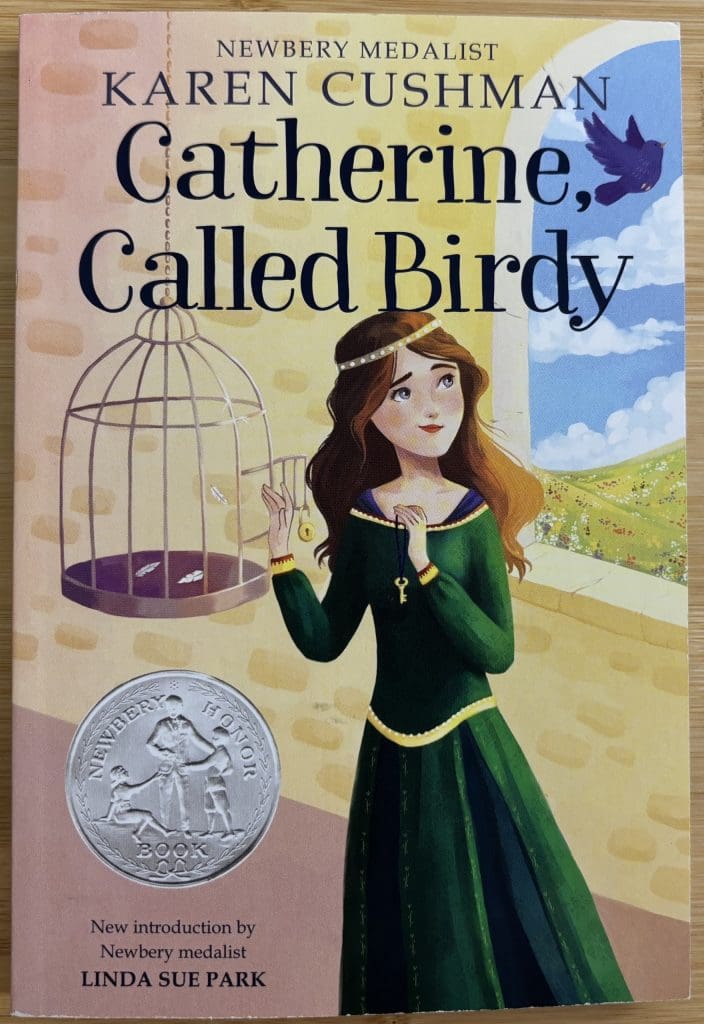

Catherine, Called Birdy by Karen Cushman was published in 1994, but was remade into a movie by writer/actor/director Lena Dunham in 2022.

Fig. 4. Left: Catherine, Called Birdy, by Karen Cushman. Illustrated by Bryan Leister (HarperCollins, 1995).

Right: Catherine, Called Birdy, by Karen Cushman. Illustrated by Maria Ukhova (HarperCollins, 2019). Photo by author.

Fig. 5. Film still from Catherine, Called Birdy, 2022 (Amazon Studios). Screengrab by author.

All these books and media are marketed to middle grade or tween audiences, and not to the slightly older young adult age group. Despite this fact, I believe there are consistent issues with sexualizing or aging up of the female protagonists in the cover illustrations and live action film adaptations of these novels, while at the same time an infantilizing of the important instructive content.

Defining Middle Grade

Most agree that middle grade books are those marketed to children ages 8-12 years old and feature characters that are approximately 10-13. Young adult books begin for readers around 13 or 14 and continue up to 18, but the protagonist is generally 16 and up.[7] In fact, within the YA genre, only 3% of stories feature characters under 16 whereas double that number have protagonists who are out of high school. Most middle grade books have 12-year-old characters, but only 16% highlight 13- and 14-year-olds.[8] What does all this data tell us? Children are marketed and tend to prefer books about characters that are a little older than they are themselves. Also, there is an obvious gap for the true middle-school-aged kids of 10-14 years old (despite making up 6.23% of the US population in 2023).[9] The problem, it seems, is crafting something relevant to the lives of kids in each age group, and those lives look very different at 8 versus 12 versus 16.

Middle grade books focus on friends, family, and the immediate world around the protagonist, without any violence or sexuality beyond a crush or a first kiss.[10] Actual middle school kids want something more than that, yet this same age group tends to be less interested in the core themes of many YA novels, mainly romance as a primary plot point.[11] The medieval inspired novels from my childhood that I have chosen to highlight here fall into a class of outliers, not quite fitting snugly into middle grade or YA, but instead appealing to a true middle-school-aged audience. In each example the main character either ages up dramatically over the course of the series, or romantic themes are present in the plot, but are not the main driving force. Perhaps this is why some of the cover illustrations of these novels struggle to depict the protagonists in a way that correctly reflects their age and personality. This is problematic, as it is through reissued covers, and in some cases movie adaptations, that new generations are introduced to older books. Moreover, these books do not shy away from difficult subject matter, in the same way that middle school aged girls have difficult experiences that must be taken seriously, and it is therefore especially important to depict the characters accurately and respectfully in visual media.

Capturing Androgyny: Alanna: The First Adventure

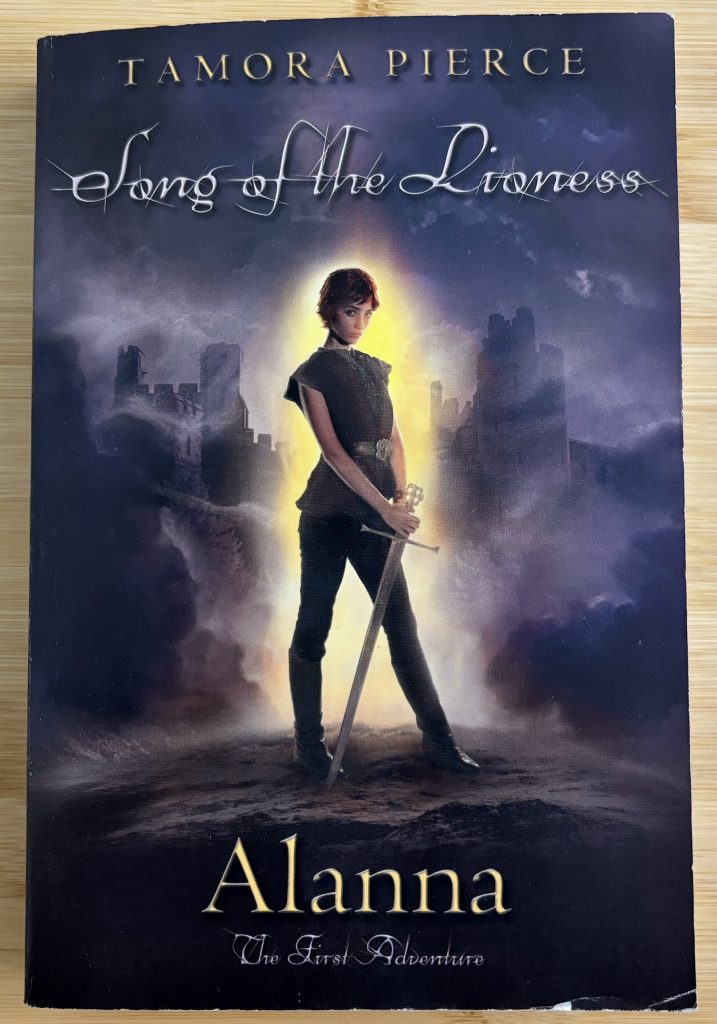

Alanna: The First Adventure was Tamora Pierce’s first published book. It began as a failed adult novel that she eventually aged down and split into four separate installments.[12] Known as the Song of the Lioness quartet, these books represent the beginning of Pierce’s ever-expanding Tortall Universe, with sequels and spin-offs published as recently as 2018. Alanna follows the title character, also known as Alan, in the fantasy kingdom of Tortall. She disguises herself as her twin brother in order to train as a knight, something that women were not allowed to do in this universe. The 2023 Simon & Schuster edition of the first book was marketed to children ages 12 and up. Amazon advertises the box set of the full quartet online for grades 7 through 9. I recently found a copy shelved in the young adult section of the local book store near where I grew up.

This series is clearly difficult to categorize. Alanna/Alan is 11 years old at the start of the first book and ages up to about 14, placing her firmly in the middle grade main character age range. But in the second book, In the Hand of the Goddess, Alanna ages to 18, and in the final two books she is between 19 and 21. Despite this fact, with large text, a third person perspective, and each book averaging just under 300 pages, they read firmly in that not quite middle grade, not quite young adult stage that would appeal to middle school students.

The Song of the Lioness quartet has had at least nine different cover illustrations in the United States editions and re-releases over the last forty years since its first publication. They tend to follow trends in cover illustration in children’s literature more generally, for example there is a truly horrible 2010 Atheneum reissue that looks like it is trying to attract the Twilight fanbase.

Fig. 6. Alanna, The First Adventure, by Tamora Pierce. Cover photo-illustration by Dominic Harman (Atheneum, 2010). Photo by author.

In the book Alanna is red haired, has a white-maned horse companion, and acquires a magic sword; all elements that appear on many of the covers. Some even correctly dress her in a gold page’s tunic with red pants, or include the slight purple glow she gives off when she secretly practices magic. The consistent problem with many of these covers, especially for the first two books, is that they do not depict an androgynous 11- to 17-year-old child. This is important, because Alanna is known only as a boy named Alan to all but a few characters throughout the first two books. The first chapter of book one describes Alanna and her brother; “Thom and Alanna of Trebond were twins, both with red hair and purple eyes. The only difference between them – as far as most people could tell – was the length of their hair. In face and body shape, dressed alike, they would have looked alike.”[13] It is crucial to the plot of the novel that Alanna is able to pass convincingly as a boy throughout her entire childhood.

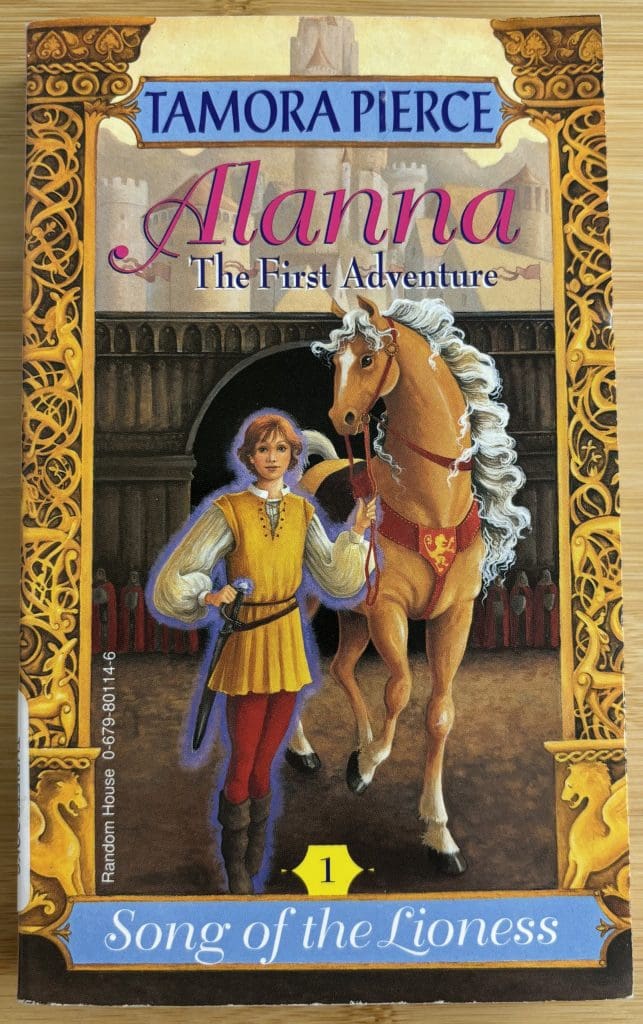

Despite this fact, many editions of the first two books have cover illustrations where Alanna ranges from girly to downright sexualized. In that same 2010 reissue discussed above Alanna is shown in three-quarter perspective, leaning on her sword so that her hip pops, accentuating the curve of her body. Her lips are pursed in an imitation of the “duck-face” style of a social media selfie and her hair looks less page boy and more Hallie Berry in the mid 1990s or Alice Cullen of the Twilight saga. In the original 1983 design illustrated by David Weisner the crop of Alanna’s tunic is short and her pants, if she is in fact wearing any, are skin toned. Both elements draw attention to her thighs.[14] A similar problem occurs in the 1997 Random House Young Readers edition of In the Hand of the Goddess illustrated by Joyce Patti.

Fig. 7. In the Hand of the Goddess, by Tamora Pierce. Illustration by Joyce Patti (Random House, 1997). Photo by author.

Here, in addition to the short tunic/dress and exposed thighs, Alanna appears to be wearing eye shadow and lipstick, and her hair is femininely styled, even though she is still under the age of 18 and disguised as a boy for the entirety of the novel. I personally remember the Joyce Patti additions from my own childhood, particularly the first book.

Fig. 8. Alanna, The First Adventure, by Tamora Pierce. Illustration by Joyce Patti (Random House, 1997). Photo by author.

In this iteration Alanna is appropriately childlike, but there is something about the frilliness of her horse’s mane that is off-putting. The horse looks less like a knight’s trusted mount and more like My Little Pony, as if to say to children reaching for the title in their local library, “the character on the cover may be androgynous, but this is still a book for girls.”

Books about teen girls written for even younger, child audiences should never depict sexualized images of the main characters. I do not say this because I am conservative or a prude, (I am neither) but because it is damaging to children to see themselves represented this way.[15] It is also, in my opinion, particularly critical to represent Alanna’s gender identity correctly. Before she hits puberty, Alanna is indistinguishable from her brother, meaning there is no external gender difference while clothed. At around the age of 12 to 13 Alanna begins to develop breasts, which she subsequently binds. Her response to her changing body is, “Maybe I was born this way, but I don’t have to put up with it!”[16] A year later when she has her first period and is told, “You may as well get used to it,” she responds in anger that she will try to change her developing body with her magic.[17] Ultimately, Alanna, like many girls, comes to terms with her body and her gender as assigned at birth. The Song of the Lioness was written in the 1980s when the inclusion of a non-binary or trans character in a children’s novel would have been forward thinking to say the least. Yet, the many reprints of the series prove the quartet’s enduring popularity. I think there is space for Alanna’s story to appeal to children with a variety of gender identities. Alanna may be unable to stop puberty with her magic in the world of Tortall, but in the real world this magic is possible. Her name change, breast binding, anger towards bodily development, and magical attempts to make herself grow taller so she seems more like the other boys, are all experiences that a gender non-conforming child might identify with and find useful in their own journeys. At the same time, Alanna: The First Adventure is a story that spoke to me: an athletic girl who found, and still finds, breasts and periods frustrating, despite being cis-gendered. I do not think the magic of the Tortall universe is stripped from girls if it is marketed to children with diverse gender expressions.

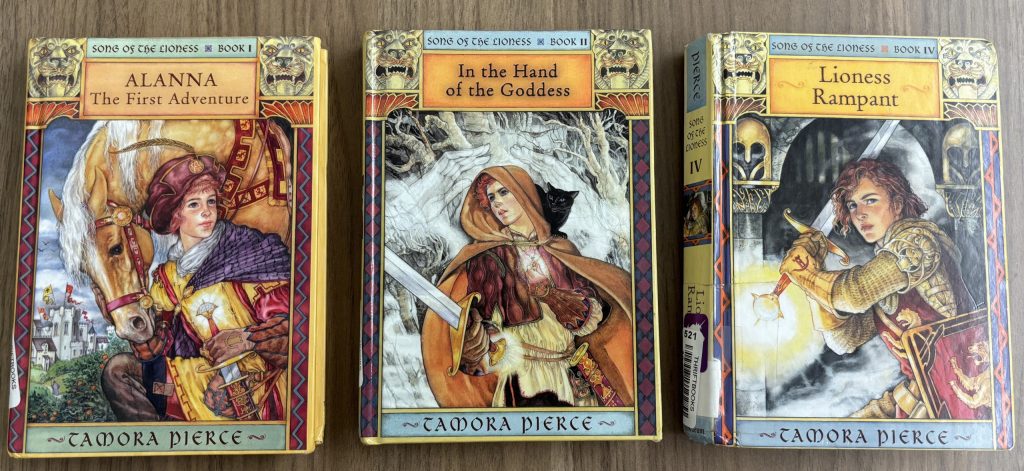

There are two editions of the cover illustration that I think correctly depict Alanna as androgynous and open the covers’ appeal beyond cis-girl readers. The first is the 2002 hardcover reissue illustrated by Marilee Heyer.

Fig. 9. Alanna, The First Adventure, In the Hand of the Goddess, and Lioness Rampant, by Tamora Pierce. Illustration by Marilee Heyer (Atheneum, 2002). Photo by author.

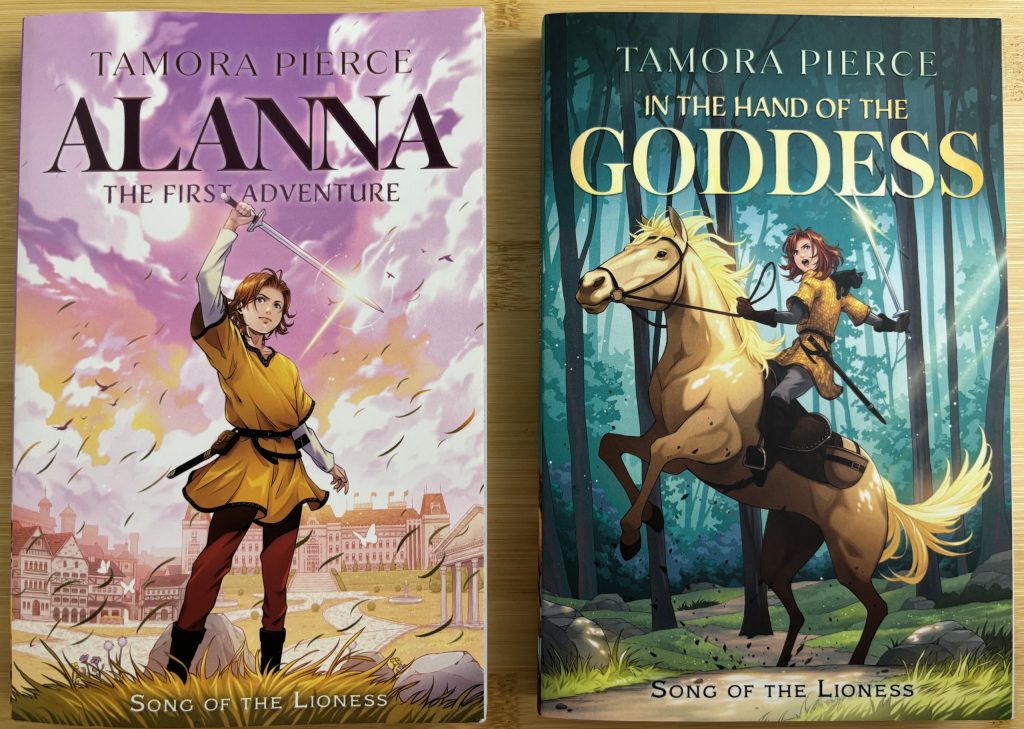

These covers are perhaps overly busy, with highly saturated colors and a bit of a Renaissance fair flare to Alanna’s outfits, but she is depicted the correct age, in clothing appropriate for her roles as page, squire, and eventually knight. More importantly, she is androgynous throughout all four covers in the series. There is no makeup or curves, but instead we see a confident warrior. Additionally, the most recent reprint, the 40th anniversary edition that was published in 2023 with cover illustrations by Yuta Onoda, is similarly well done.

Fig. 10. Alanna, The First Adventure, and In the Hand of the Goddess, by Tamora Pierce. Illustration by Yuta Onoda, (Simon & Schuster, 2023). Photo by author.

Alanna is the correct age and is androgynous in the first two covers. In Alanna: The First Adventure she is round-cheeked, wearing a tunic, and trousers that do not cling to her body. She holds her sword aloft and her short hair is tousled by the breeze. Setting aside the buildings in the background that create a confusing sense of space and seem to come from three different eras of architectural design, I believe the cover is successful in its colorful appeal to middle school aged children, without advertising a specific gender that it is attempting to market itself to. Perhaps more importantly, young readers of these editions can look up to the character of Alanna without thinking this means they must conform to a feminine beauty standard before they even hit puberty.

Girl, Adapted: Ella Enchanted and Catherine, Called Birdy

Gail Carson Levine’s Ella Enchanted and Karen Cushman’s Catherine, Called Birdy provide an interesting side-by-side comparison of a book’s textual content, cover illustration, and movie adaptation handled in completely opposite ways. Catherine was released in 1994 and Ella in 1997. Both books won Newbery Honor awards and have been adapted into feature length films. Ella Enchanted is a Cinderella retelling where the title character has been cursed by a fairy into obedience. She must follow every direct order given to her, which causes her to grow up headstrong and obstinate (a clear commentary on the standard depiction of Cinderella as cloyingly sweet despite neglect and abuse). Ella uses her sense of humor and superior language skills to conquer ogres, make friends with elves and gnomes, and gain the favor of Prince Char. Catherine, Called Birdy is not a fantasy novel but instead a work of historical fiction. Set in thirteenth-century England, it reads as the diary of Birdy who spends the book trying to fight off unwanted marriage suitors through increasingly comic hijinks.[18] Both books are marketed to an 8- to 12-year-old, middle grade audience and feature characters who start the novel around the age of fourteen.

Despite the fact that both books describe headstrong girls who push back against the even embroidery stitches and obedience expected of women, their reissues and film adaptations tell divergent stories. The original 1990s cover art of both books have similar elements. Illustrator Greg Call depicts Ella standing behind a balustrade, her hand resting on a book.

Fig. 11. Left: Ella Enchanted, by Gail Carson Levine. Illustrated by Greg Call (HarperCollins, 1997). Right: Catherine, Called Birdy, by Karen Cushman. Illustrated by Bryan Leister (HarperCollins, 1995). Photo by author.

She is wearing a square-necked velvet green dress, likely the one described in the novel as her mother’s favorite because it brought out Ella’s eyes. A tapestry behind Ella is pulled back to reveal a moonlit expanse depicting a river and castle in the distance. The overall appearance is reminiscent of late-medieval/early Renaissance portraiture. In Bryan Leister’s paperback edition of Catherine, Called Birdy, there is a similar portrait style. Birdy is in the foreground of an enclosed room. She wears a fur-lined dress, a tiered, beaded necklace, and her hair is pulled back in a black hennin. In her left hand she clutches a book and quill, alluding to the diary style of the novel, and in her right, she pulls on a rope that is poised to dump a bucket on top of a middle aged, lute playing suitor in the doorway, a landscape expanse behind him.

Both novels were reissued with new cover art recently; Ella in 2022 and Catherine in 2019, but only one of these covers preserved the character authenticity and youthful age of the protagonists. I have seen some millennial readers disparage the new Catherine, Called Birdy cover in the blogosphere, arguing that its bright colors and cartoony feel are incompatible with the medieval, flea-bitten world in which Catherine is set.

Fig. 12. Catherine, Called Birdy, by Karen Cushman. Illustrated by Maria Ukhova (HarperCollins, 2019). Photo by author.

As a scholar of medieval art, I disagree. I do not find the brightness of this cover incongruent with a time period characterized by burgeoning universities, cathedrals brightly lit with stained glass windows, or book art with comically frolicking rabbits. In this cover by Maria Ukhova, Birdy is youthful without any hint of sexuality. Her hopeful gaze out the window as she releases one of her birds from its cage is in line with a character who never stops searching for the life she wants. In contrast, when I first saw the 25th anniversary edition cover of Ella Enchanted by Lisa Keene I was horrified.

Fig. 11. Ella Enchanted, by Gail Carson Levine. Illustrated by Lisa Keene (Quill Tree Books, 2022). Photo by author.

The cover leans into the fact that the novel is a Cinderella retelling, but in a way that makes me question if the artist even bothered to read the book first. Ella is depicted in a ball gown stepping away from her magic pumpkin-turned-carriage. Her face is turned over one shoulder but her eyes look coyly out towards the viewer. Her hair is styled in flawless waves that seem to blow backwards in an invisible breeze. Her face looks like it’s gone through an Instagram filter. The illustration makes her look 25 instead of 14.

Gone is any sense that the girl depicted here might be the same Ella who over the course of the novel abandons finishing school, tricks murderous ogres, learns several new languages, and stands up to xenophobic and racist remarks directed at her friend. Yet, I think what bothers me most about this cover is the fact that the girl illustrated seems designed after a social media influencer. This book has been inspiring young girls for a quarter century, and the new cover is marketing the same unattainable, airbrushed version of feminine perfection that scientific studies have proven time and again are detrimental to the mental and physical wellbeing of girls. To me, this is inexcusable.

Unfortunately, Ella Enchanted did not receive better treatment in its movie adaptation. Released in 2004, the film starred Anne Hathaway as Ella and Hugh Dancy as Prince Char.

Fig. 14. Film still from Ella Enchanted, 2004 (Miramax Films). Screengrab by author.

The actors were 22 and 29 years old respectively, and even though it is not uncommon for older actors to play teenage characters, Hathaway and Dancy do not read youthful on screen.[19] Despite raising the age of the two principal characters, the movie does not take the opportunity to simultaneously raise the intellectual and emotional depth. The book has many serious moments. Ella’s mother dies on page nine. She confronts grief, racism, xenophobia, and emotional abuse. In the movie adaptation, instead of having Prince Char and Ella meet as he provides comforting words at her mother’s funeral, Char is vapid and mean. Ella must endeavor to “fix” him over the course of the movie, which reinforces the idea that girls should put up with problematic behavior in the hope that the boys they like will change.

Perhaps most egregiously, Ella’s best friend Areida, who is described in the novel as cinnamon skinned with, “dark hair plaited into many braids,” has a downsized part in the film, where she is played by actress Parminder Nagra.[20] In the book Ella spends weeks learning Areida’s language so that they can speak in a way she is most comfortable. She refuses an order to shun Areida and instead runs away from finishing school. Eventually, once her curse is broken, Ella reaches back out to Areida and restrengthens their friendship. In the film, the language connection is completely removed. Ella follows the order to verbally shun Areida, re-victimizing someone who at this point in the film has been repeatedly subject to racist teasing. In the end Ella lives happily ever after with Prince Char and Areida is never seen nor heard from again. If the character of Areida was introduced by Gail Carson Levine as a way to illustrate how peer pressure can lead to hurtful conduct and the perpetuation of unsafe environments for girls of color, then the movie loses sight of this lesson completely. Movies do not have to adapt their source material perfectly in order to be good films. But, in my opinion, to take a story directed at children, age up the characters, insert a problematic romantic relationship, and simultaneously remove all of the material that renders serious nuance to young lives, is unforgivable.

The film adaptation of Catherine, Called Birdy, when compared to Ella Enchanted is a study in opposites. Written, directed, and produced by Lena Dunham the movie stars Bella Ramsey, who was, and reads on screen, as a teenager.[21]

Fig. 15. Film still from Catherine, Called Birdy, 2022 (Amazon Studios). Screengrab by author.

Ramsey performs Birdy as silly and sometimes spoiled, perfectly keeping with the character of a fourteen-year-old girl. The movie follows the general beats of the book, and is, all-in-all, a comedy. Yet, it also expands the side characters and adds emotional development that is only hinted at in the novel’s short, diary entry style. For example, Birdy’s father, who in the film is played by Andrew Scott, is still the problematically patriarchal center of the story, but he is more self-reflective and grows as a character. Changes to the script serve to update the parts of the story that may have worked in the early 1990s but feel outdated in 2022, unlike the film version of Ella Enchanted which is somehow less current than the book.

The landscape of fiction looks very different today from what it did during my childhood. The protagonists are more diverse. Authors are exploring an increased number of sexual and gender identities. Consequently, a greater number of children are finding themselves represented in medieval inspired realms. This is important, because fantasy, which is so often medieval coded, provides a crucial space for imagination and play. We cannot lose sight of how these medieval worlds and their inhabitants are depicted and marketed, especially towards children. Any lover of medieval fantasy should know that these books are not a return to an ideal past time, but instead an exploration of contemporary problems, just with more dragons and swords. If the real lives of young girls contain struggle and silliness, lessons and laughter, then fantasy books about girls should too. In the end, we do judge a book by its cover. Consequently, the visual culture surrounding these books should not market shined up and simple protagonists but instead should reflect the reality of girlhood even when girlhood is messy.

References

| ↑1 | Joanne O’Sullivan, “Who is YA For?,” Publishers Weekly, October 13, 2023, https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/childrens/childrens-industry-news/article/93417-who-is-ya-for.html. According to a 2023 article in Publishers Weekly, 51% of young adult books are purchased by individuals aged 30-44, and 78% of those indicated they intended to read the book on their own instead of to a child. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rebecca Rubin, “‘Barbie’ is Officially the Highest-Grossing Release of the Year with $1.36 Billion Globally,” Variety, September 2, 2023, https://variety.com/2023/film/box-office/barbie-highest-grossing-worldwide-movie-year-1235705510/; Antonio Pequeño IV, “‘Barbie’ Officially Becomes This Year’s Highest-Grossing Movie In the World – As It Edges Past ‘The Super Mario Bros. Movie’,” Forbes, September 2, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/antoniopequenoiv/2023/09/02/barbie-officially-becomes-this-years-highest-grossing-movie-in-the-world-as-it-edges-past-the-super-mario-bros-movie/?sh=5a55823a587a; Megan McCluskey, “As Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour Hits One Year, Let’s Take a Look at Its Staggering Numbers,” Time, March 15, 2024, https://time.com/6900208/taylor-swift-eras-tour-anniversary-stats/. In 2023 the Barbie movie was the highest grossing film, even beating out 2011’s Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2 as Warner Brother’s all-time highest grossing worldwide release. It made Greta Gerwig the highest grossing female director in the United States. Millions of women and girls created and traded friendship bracelets at Taylor Swift’s The Eras Tour concert, which sold 4.35 million tickets over the course of its first year. |

| ↑3 | Isabel Cristo, “Women in Retrograde,” The Cut, December 19, 2023, https://www.thecut.com/article/girl-culture.html. |

| ↑4 | Cristo, “Women in Retrograde.” |

| ↑5 | Emma Gray and Claire Fallon, “Girly Girls,” Rich Text, Substack, https://claireandemma.substack.com/. |

| ↑6 | Gray and Fallon, “Girly Girls.” |

| ↑7 | Marie Lamba, “The Key Difference Between Middle Grade vs. Young Adult,” Writer’s Digest, August 7, 2014, https://www.writersdigest.com/write-better-fiction/the-key-differences-between-middle-grade-vs-young-adult; Krystle Appiah, “What is Middle Grade Fiction and How Is It Different from YA?,” The Novelry, April 24, 2022, https://www.thenovelry.com/blog/middle-grade-vs-young-adult fiction#:~:text=Middle%20grade%20is%20exactly%20what,YA%20stands%20for%20young%20adult; Katy Hershberger, “Middle Grade Is too Young, YA too Old. Where Are the Just-Right Books for Tweens?,” School Library Journal, November 1, 2019, https://www.slj.com/story/MiddleGrade-Too-Young-YA-Too-Old-Where-Are-the-Books-for-Tweens-libraries. |

| ↑8 | Hershberger, “Middle Grade Is too Young, YA too Old.” |

| ↑9 | “2023 Data Table,” Census.gov, accessed June 19, 2024, https://www.census.gov/popclock/data_tables.php?component=pyramid. |

| ↑10 | Lamba, “The Key Difference Between Middle Grade vs. Young Adult.” |

| ↑11 | Hershberger, “Middle Grade Is too Young, YA too Old.” |

| ↑12 | Tamora Pierce, “Tamora Pierce Biography,” Tamora Pierce, accessed June 21, 2024, https://www.tamora-pierce.net/about/. |

| ↑13 | Tamora Pierce, Alanna: The First Adventure (Atheneum, Simon & Schuster Children’s Publishing Division, 2023) Original edition published (Atheneum, 1983), 2. |

| ↑14 | An image of the cover of the original edition of Alanna: The First Adventure can be found on the book’s Wikipedia page entry. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alanna:_The_First_Adventure. |

| ↑15 | Alana Papageorgiou, Donna Cross, and Colleen Fisher, “Sexualized Images on Social Media and Adolescent Girls’ Mental Health: Qualitative Insights from Parents, School Support Service Staff and Youth Mental Health Serve Providers,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(1) (December 2022): 433, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9819033/; “Sexualization of Girls is Linked to Common Mental Health Problems in Girls and Women – Eating Disorders, Low Self-Esteem, and Depression; An APA Task Force Reports,” American Psychological Association, (2007), https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2007/02/sexualization; Jaimee Swift and Hannah Gould, “Not an Object: On Sexualization and Exploitation of Women and Girls,” UNICEF USA, January 11, 2021, https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/not-object-sexualization-and-exploitation-women-and-girls-0#:~:text=Consequences%20of%20hypersexualization%20for%20girls,lower%20self%2Desteem%20and%20depression. |

| ↑16 | Pierce, Alanna: The First Adventure, 122. |

| ↑17 | Pierce, Alanna: The First Adventure, 157-59. |

| ↑18 | The back cover and some of the marketing material found online claim that the novel is set in fourteenth-century England, but Birdy dates the first entries of her diary to September of 1290. |

| ↑19 | This may simply be my opinion, but for further context Anne Hathaway plays a twenty-something adult just two years later in the film The Devil Wears Prada. |

| ↑20 | Gail Carson Levine, Ella Enchanted, (Quill Tree Books a HarperCollins Publishers imprint, 2022), Original edition published (HarperCollins, 1997), 74. The casting of Parminder Nagra transitions the character from black (at least how I read it) to someone of Indian descent. |

| ↑21 | Based on the actress’s current age I believe she was around eighteen at the time of filming. |