Lindsay S. Cook • Penn State University

Recommended citation: Lindsay S. Cook, “Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame in the Making of a Medievalist,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/XSRM9686.

When I studied abroad during my junior year of college, my utter fascination with French Gothic architecture initially puzzled Madame Françoise de Turckheim, the inimitable host who generously opened her quintessentially Parisian home to me on the rez-de-chaussée of a stately nineteenth-century apartment building on a boulevard in the 17th arrondissement, where she would continue to rent me an affordable room well into my graduate school days (fig. 1). Early on, she asked me something to the effect of, “How did you come to study our cathedrals [nos cathédrales]?” Her use of the possessive “our” rang in my ears. While I knew enough about historic monuments by then to know that French cathedrals technically belonged to the state, and thus, in a sense, to the French people, the fact is, I thought of these magnificent and awe-inspiring edifices as mine, too.[1] At the time, I gave my gracious host a somewhat defensive answer that eventually became the official version of the story, in which I emphasized the many classes I had taken with inspiring teachers over the years about French language, history, culture, and especially art and architecture.

Fig. 1. The author with Mme Françoise de Turckheim, 2009. Photo by Melissa Perrett Cook.

Updated to reflect the fifteen years that have elapsed since then, the “official” story of how I became a historian of French Gothic architecture is straightforward enough. Indeed, it might, at first glance, seem quite linear. A studious theater kid who intended to major in English literature, I fell in love with the Vassar College campus in New York’s Hudson River Valley on one of the many college visits I took during the spring of my junior year of high school. I applied Early Decision to the private, small liberal arts college, so when I received my letter of admission over winter break of my senior year, I had to jettison the twenty or so other college applications I had meticulously prepared and instead began getting ready to move across the country. Vassar’s legendary art history courses Art 105 and Art 106 drew me to the field, and Byzantinist Sarah Brooks’s excellent teaching cracked the world of medieval art wide open for me. By the end of my first year of college, I knew that I wanted to declare an art history major.

Ultimately, I decided to double major in Art History and French & Francophone Studies, and I spent the spring semester of my junior year studying abroad in Paris. Back on campus, I worked closely with French Gothic architecture specialist Andrew Tallon after he joined the faculty as an Assistant Professor in 2007. In 2010, Tallon selected me from a pool of applicants to join Mapping Gothic France, the digital humanities grant project he was co-leading at the time. I took and processed digital photographs of dozens of Romanesque and Gothic churches in Burgundy, available in open access on the Mapping Gothic website as panoramas ever since.[2] Through intensive fieldwork, amusing car rides, and joyous group meals, I also got to know Professor Stephen Murray, several of his brilliant Columbia University art history graduate students, and talented Media Center for Art History staff members. The following fall, I applied to the Ph.D. program at Columbia to study French Gothic architecture with Stephen Murray, and, indeed, the rest is history.

This version of events is certainly true: without the mentorship of Sarah Brooks, Andrew Tallon, and Stephen Murray, I simply would not be a professional medievalist today. And yet, it does exclude as much from the story as it includes. The missing pieces are more personal and less academic, but likewise important in the making of a medievalist. A combination of memories and a small collection of personal artifacts I unearthed recently at my childhood home in Chicago make it clear that the “official” account leaves out key sources of inspiration, including multiple forms of medievalism. This short essay aims to write several childhood experiences into the story of how I came to the academic study of medieval architecture, in general, and that of Notre-Dame of Paris, specifically.

I grew up in Hyde Park, in the shadow of the very same gargoyles that so inspired the late medievalist Michael Camille.[3] From the crenellations, pinnacled lantern tower, and incised Gothic script of the Chicago Lying-In Hospital where I was born, to the pointed arches, prominent gables, and stair turrets of the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools where I attended lower, middle, and high school, to the stained glass, hovering wooden angels, and soaring finials of Ralph Adams Cram’s Fourth Presbyterian Church where I attended church and Sunday school, late nineteenth- and especially early twentieth-century Gothic buildings punctuated my experience of the city. In addition, a sizable poster from the Musée d’Orsay of Maximilien Luce’s Le Quai Saint-Michel et Notre-Dame (1901) hung on the wall in each place I lived throughout my childhood, including the house where my parents still live (fig. 2). Meanwhile, in New Orleans, where I traveled regularly to visit my maternal grandparents, some of the city’s allusions to medieval France are literally embedded in the pavement, as at the intersection of Chartres and St. Louis Streets in the French Quarter (fig. 3).

Fig. 2. Poster from the Musée d’Orsay of Maximilien Luce’s Le Quai Saint-Michel et Notre-Dame in the living room of the author’s childhood home, 2024. Photo by Lindsay S. Cook.

Fig. 3. New Orleans, street tiles at the intersection of Chartres and St. Louis Streets, 2024. Photo by Lindsay S. Cook.

Beyond encountering medievalism in the built environment, I also had early brushes with “real” medieval art and material culture. On the one hand, the dimly lit, arms and armor-lined passageway that connected one wing of the Art Institute of Chicago to the other evoked masculine violence and frightened me. On the other hand, the dynamic composition of Bernat Martorell’s panel painting Saint George and the Dragon fascinated me when beloved museum educator Daryl Rizzo brought us young viewers into the galleries to look at the painting closely and share our observations about it to anchor an especially memorable Early Bird Workshop one Saturday morning in the early 1990s (fig. 4).[4]

Fig. 4. Bernat Martorell, Saint George and the Dragon, tempera on panel, 1434-1435. Courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Learning to read and speak a language is, of course, a particularly powerful way to learn about the cultures where that language is spoken. In the 1990s, my elementary school offered foreign language instruction in three languages: German, French, and Spanish. Spanish was, by far, the most popular choice, and it was certainly the most useful in the daily lives of Chicagoans. Nevertheless, inspired by the Francophiles on my mom’s side of the family, I picked French (fig. 5). The choice especially delighted my grandfather, Marvin J. Perrett (fig. 6). After decades of relative silence on the matter, he began speaking in volumes about his service in the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II shortly before I was born.[5] A gifted storyteller, he often waxed poetic about the beauty of France and the warmth and hospitality of the French people, including that of the Coispel family who welcomed him into their home in Grandcamp-les-Bains (Calvados, Normandy) for cider, Cognac, and coffee about a week after D-Day. But he also expressed regret that he did not speak French fluently.

Fig. 5. Postcard with Notre-Dame of Paris on the front, sent from Edith Perrett (the author’s grandmother) to Irma Shepherd (the author’s great-grandmother), 1984. Courtesy of Melissa Perrett Cook.

Fig. 6. Marvin Perrett (the author’s grandfather) with French Minister of Defense Michèle Alliot-Marie at the Hôtel des Invalides after receiving the Legion of Honor medal, 2004. Photo courtesy of Melissa Perrett Cook.

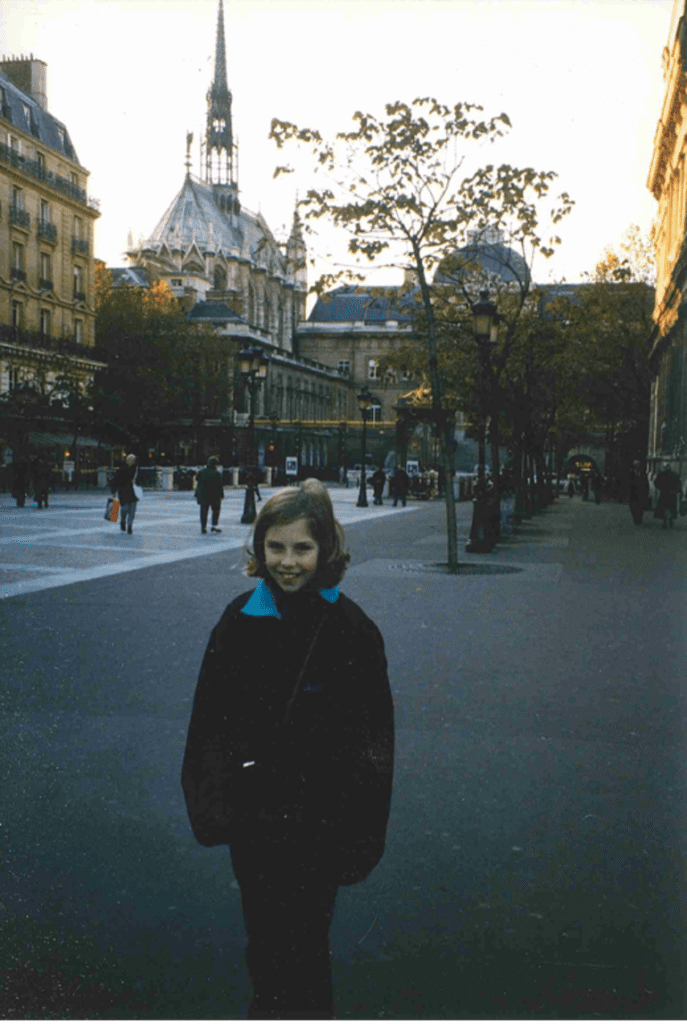

Two years into my own French language journey, at the age of ten, I had the opportunity to travel abroad for the first time. My dad had to speak at a conference in Paris, and my mom, younger brother, and I joined him.[6] On our first full day in the city, which happened to coincide with All Saints’ Day (November 1), we attempted to visit Notre-Dame of Paris:

Today my brother, Mom, and I all took the Metro to the Notre Dame Cathedral. We couldn’t go up because the lines were to [sic] long and we couldn’t go in the church because they were having mass [sic], so we went to get something to eat. It was around noon in Paris (5:00 a.m. in Chicago) and before we went to eat we stopped in some of the little shops along the way. “Tourist traps,” my mom called them, but I liked them anyway. We ate at a place called Notre Dame de Quazimodo [sic]. The food was fabulous, and the surroundings were cute, too.[7]

We had more success when we returned to the cathedral on the sixth day of our trip. In the interim, we also visited the Sainte-Chapelle (fig. 7), and I even had the unusual privilege of joining my dad at a professional dinner at the Musée de Cluny. Our table was in the part of the museum that was once the frigidarium of the Gallo-Roman thermal baths and later incorporated into the late medieval Hôtel de Cluny. While the dessert course consisting of poached pears was far too sophisticated for my palate at the time, the museum’s atmosphere—what I would now call its age-value—left a lasting impression.[8]

Fig. 7. The author with the Sainte-Chapelle in the background, 1998. Photo by Melissa Perrett Cook.

When we did finally make it back to the cathedral of Paris, we ascended the north tower, made our way along the balustrade amidst a throng of fellow tourists, and took a flurry of pictures. My own compact point-and-shoot film camera had a slider that enabled me to choose between three different aspect ratios for each shot. Long before I worked as a panorama photographer for Mapping Gothic France, I apparently intuited that the sprawling view from Notre-Dame called for the panorama setting (fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Paris, Notre-Dame, view from the balustrade facing north, 1998. Photo by Lindsay S. Cook.

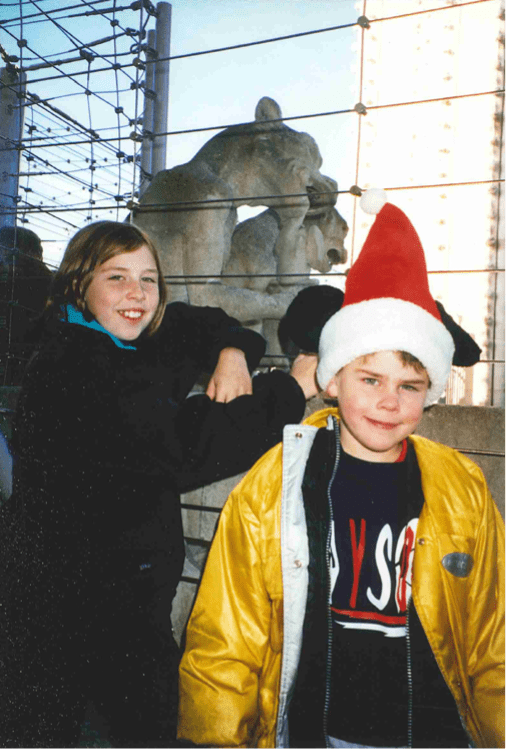

The most emblematic picture from what architectural historians would call my first “climb” at Notre-Dame is undoubtedly the one in which my brother and I are shown standing in front of two chimeras, with thick suicide-prevention cables conspicuously separating us from them. In the picture, my brother wears a synthetic Santa hat with plush Mickey Mouse ears attached on either side, a souvenir from his trip to Disneyland Paris with my dad, which overlapped with my own first visit to the Louvre with my mom (fig. 9). Noting the appearance of Disney imagery in this photograph led me to recognize the lasting, if subliminal impact of Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame on our 1998 touristic visit. As Michael Camille rightly observed, “the 630,000 visitors who climbed the steps” that year “to look from the towers of Notre-Dame and pose among the gargoyles were not only visiting a hallowed site on the modern European tour, but were also positioning themselves within their internalized memories of these filmic narratives.”[9] In my case, the twin experiences of seeing the movie and subsequently visiting the cathedral in person likewise seem to have shaped my career path.

Fig. 9. The author and her brother on the balustrade of Notre-Dame, 1998. Photo by Melissa Perrett Cook.

I saw the Disney animated feature with my family in theaters when it came out in 1996. If, as Paul Goldberger wrote in his scathing New York Times review, unlike the 1923 and 1939 films of the same name, “this ‘Hunchback,’ by contrast, was designed for the youngsters,” then I belonged to the right demographic for the Disney version to sink in.[10] My family’s enthusiasm was palpable: we even attempted to collect every character in the series of toys Burger King released for the occasion in its Kids Meals, the fast-food chain’s answer to the McDonald’s Happy Meal. In fact, we ended up with an odd assortment that included a comical and frustrating number of Clopins, the impresario who, in Disney’s adaptation, speaks English with a stereotypical French accent played for laughs. Only three plastic figurines survive from the larger collection: the protagonist Quasimodo, the conceited knight Phoebus, and the pigeon-tormented gargoyle Laverne (fig. 10). Since I realized only recently that the Disney film came out well before my first visits to the Musée de Cluny, the Sainte-Chapelle, and Notre-Dame itself at age ten, I certainly do not recall what exactly I thought of the film at the time. Nevertheless, it is clear to me now that the popular movie went a long way toward making the cathedral mine–and possibly yours, too.

Fig. 10. Figurines of Quasimodo, Phoebus, and Laverne, three characters from Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Burger King Kids Meal toys, 1996. Photo by Lindsay S. Cook.

References

| ↑1 | See, for example, La naissance des Monuments historiques: la correspondance de Prosper Mérimée avec Ludovic Vitet (1840-1848) (Paris: Éditions du C.T.H.S., 1998); Kevin D. Murphy, Memory and Modernity: Viollet-le-Duc at Vézelay (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1999). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Mapping Gothic Project, Media Center for Art History, Columbia University, mappinggothic.org. |

| ↑3 | “In the five years spent researching and writing this book my time has been divided between two gargoyle-infested places, Paris and the University of Chicago.” Michael Camille, The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame: Medievalism and the Monsters of Modernity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009), xv. |

| ↑4 | Early Bird Workshops were geared toward children between the ages of 4 and 6 years old, and Family Workshops were intended for children aged 7 and older. Both were based in the Art Institute of Chicago’s Kraft Education Center. See, for example, Nancy Maes, “Christmas Through a Child’s Eyes,” Chicago Tribune, December 6, 1991, 46. |

| ↑5 | He was a Higgins boat coxswain aboard the USS Bayfield, the vessel that served as the flagship for Utah Beach on D-Day (June 6, 1944). |

| ↑6 | XI Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology, Paris, France, October 31-November 4, 1998, http://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10063423/. |

| ↑7 | Lindsay Cook, travel journal, “Day 2,” 1 November 1998. The spelling errors “to” and “Quazimodo” and the capitalization error “mass” have been preserved intentionally. |

| ↑8 | Lindsay Cook, travel journal, “Day 3,” 2 November 1998. On the concept of age-value, see Aloïs Riegl, “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin,” trans. Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo, Oppositions, no. 25 (Fall 1982), 21-51. |

| ↑9 | Camille, The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame, 335. |

| ↑10 | Paul Goldberger, “Cuddling Up to Quasimodo and Friends,” The New York Times, June 23, 1996: “This ‘Hunchback,’ by contrast, was designed for the youngsters. Even a 6-year-old could love it. Perhaps only a 6-year-old could love it.” |