Sarah S. Wilkins • Pratt Institute

Recommended citation: Sarah S. Wilkins, “’I Am That Woman:’ Creating the Eremitical Magdalen Dwelling in the Wilderness of Provence,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 12 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/NEQG8610.

‘Do you remember what the Gospel says about Mary the notorious sinner, who washed the Savior’s feet with her tears and dried them with her hair, and earned forgiveness for all her misdeeds?’ ‘I do remember,’ the priest replied, ‘and more than thirty years have gone by since then. Holy Church also believes and confesses what you have said about her.’ ‘I am that woman,’ she said. ‘For the space of thirty years I have lived here unknown to everyone; and as you were allowed to see yesterday, every day I am borne aloft seven times by angelic hands, and have been found worthy to hear with the ears of my body the joyful jubilation of the heavenly hosts.’

Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend[1]

In many ways, Mary Magdalen is not your typical desert saint.[2] The ‘desert’ or wilderness where she resided alone in contemplation for thirty years, clad only in her hair, was not located in the east, in Egypt, Syria or Palestine. Instead, she lived in a cave in the Sainte-Baume Massif, a mountain ridge that extends between the départements of Bouches-du-Rhône and Var in a wooded region of Southern France. Rather than being a Desert ‘Father,’ as was most usual for eremitic saints, she was a Desert ‘Mother,’ indeed, part of the subcategory of ‘holy harlots.’[3] Rather than living in the late antique period, the era of the Desert Fathers and what has been called “the desert movement,” Mary Magdalen was a biblical saint.[4] Lastly, her sojourn in the wilderness was not part of her penitential journey as it was for other hairy eremitic saints.[5] Although penitence was a critical aspect of the understanding of the Magdalen in the period and is key to her transformation into a desert saint, her residence in the wilderness began long after she had been granted absolution for her sins by God himself.

The Magdalen’s legendary life in the wilderness is thematically linked to her penitential actions described in the Bible in Luke 7:37-50, when the unnamed sinner in the house of the Pharisee—officially said to be Mary Magdalen since the time of Gregory the Great (r. 590-604 CE)—wept upon Christ’s feet and dried them with her hair; in return she received absolution from Christ, who said to her “Thy sins are forgiven thee.” As a woman who sinned, that sin was presumed to be sexual, and she quickly became understood as a penitent prostitute saint.[6] Her transformation into a hirsute desert saint, however, was the end result of a lengthy hagiographic process. The Magdalen became an eremite through her conflation with another penitential prostitute saint, Mary of Egypt.[7] The Magdalen’s ‘wilderness,’ the location of which was originally unidentified, was later established as France by the abbey of Vézelay in order to justify their supposed possession of the Magdalen’s relics, which they claimed to have stolen from Provence in a furtum sacrum, a holy theft.[8] It was the Angevin rulers of Provence and Naples, however, in concert with the Franciscans and the Dominicans that fully developed and promoted the image of the eremitic Magdalen beginning in the late thirteenth century.

In this essay, after considering how and why Mary Magdalen came to be an eremitical saint, I examine the dissemination of this new understanding of Mary Magdalen in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century central and southern Italian painting, much of it linked to the Dominican and Franciscan orders, as well as to the Angevins who were firm supporters of both orders. These three groups avidly promoted her cult after 1279, when the Angevin crown prince, the future Charles II, ‘discovered’ the Magdalen’s body in the Basilica of Saint-Maximin in Provence. Virtually all visual cycles of the Life of the Magdalen from this period include at least one depiction of her as a desert saint clad only in her hair, often more. Individual depictions of the Magdalen—narrative illuminations, frescoes, and panel paintings, as well as iconic representations—also frequently show her in this guise. Such images emphasize her penitential nature, a critical aspect of mendicant veneration of the saint, while firmly localizing her in Angevin Provence. This article explores their intersecting interests in the eremitic Magdalen, focusing especially on the iconography of the Magdalen receiving Communion from an angel, a pivotal pictorial creation in the period whose significance has hitherto been overlooked.

Creation of the Eremitical Magdalen—Written Hagiography

According to the legendary life of the Magdalen, found in its most complete and well-known form in the Dominican Jacobus de Voragine’s (1228-1298) popular thirteenth-century book of saints’ lives the Golden Legend, after Christ’s Resurrection, Mary Magdalen—along with Martha, Lazarus, Maximin, and others—were put to sea in a rudderless boat by non-believers. With God’s help, they miraculously reached Provence where the Magdalen converted the rulers of Marseilles. Then the Magdalen retreated to a cave in the wilderness clad only in her hair, for a life of penance and contemplation. Eating no food, the Magdalen was raised to the heavens by angels at the seven canonical hours to receive heavenly sustenance. After thirty years, a priest discovered her and, depending on the version, she either received a garment from him and went with him to a church to receive viaticum and died, or was angelically transported to the church where St. Maximin was bishop, and received Last Communion and died there.[9] Developed to explain and justify the presence of the Magdalen’s original cultic center in France at the abbey of Vézelay in Burgundy, this legend weaves together multiple hagiographic threads, which it is worth briefly disentangling here (Table 1).[10]

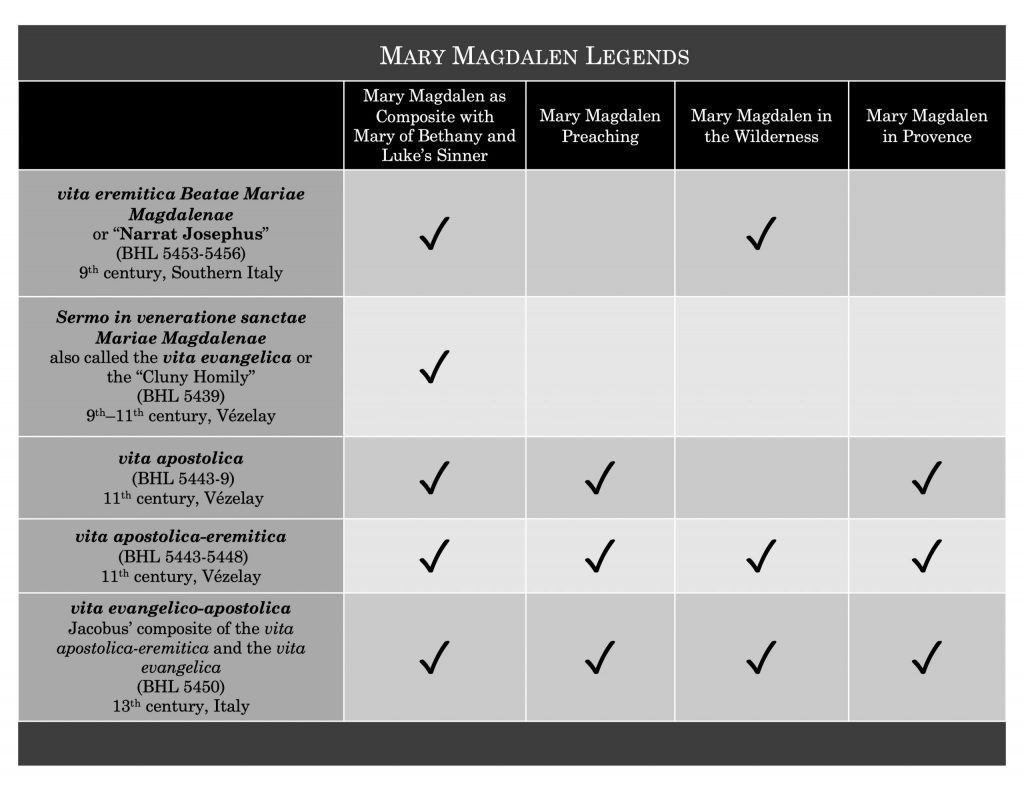

Table 1. Mary Magdalen Legends.

The earliest material contributing to the legendary life of the Magdalen are the early ninth-century vita eremitica Beatae Mariae Magdalenae (BHL 5453-5456) and the Sermo in veneratione sanctae Mariae Magdalenae (BHL 5439), better known as the vita evangelica, dating from between the ninth and eleventh century.[11] This latter text is a homily rather than a vita, fashioning a unified narrative out of the scriptural passages about Mary Magdalen, Mary of Bethany and Luke’s unnamed sinner.[12] While not itself contributing to the Magdalen’s legendary life in the desert, it was later combined with those that did.

The vita eremitica, however—also known as the “Narrat Josephus” variant, because it was introduced in the Golden Legend with the phrase “Hegesippus (or, as some books have it, Josephus) agrees in the main with the story just told”—was crucial in the creation of the eremitical Magdalen.[13] Originating in southern Italy, but widely known in France by the late eleventh century, this penitential vita incorporated elements from the life of St. Mary of Egypt, an Eastern penitential prostitute desert saint said to have lived in the fourth or fifth century, whose similarity of name and of reputation as a sexual sinner must have led to some confusion.[14]

Mary of Egypt first appears in the mid-sixth century in the Life of St. Kyriacus by Cyril of Scythopolis.[15] In the seventh century, the Life of St. Mary of Egypt attributed to Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem (560-638), was written in Greek and by the eighth or ninth century it was translated into Latin, probably in Naples by the deacon Paul.[16] She ultimately came to be one of the few female saints commonly included in the Latin compilation known as Vitae Patrum (Lives of the Desert Fathers) and in its vernacular translation by the Dominican Domenico Cavalca (c. 1270-c. 1342), Vita dei Santi Padri (c. 1330).[17] According to Mary of Egypt’s Life, unable to pass the threshold of the Holy Sepulchre due to her sexual sins, she fled the city of Jerusalem and crossed over the river Jordan. There Mary dwelt in the desert for forty-seven years with virtually no food, until she was discovered by the priest Zosimus, to whom she narrated her life.[18] At her request, he gave her Communion on Good Friday, after which she died.

The influence of Mary of Egypt’s narrative on that of the Magdalen in the vita eremitica is obvious. The vita eremitica contains the earliest reference to the Magdalen’s thirty-year penitential retreat into a grotto in the desert, her nakedness, her elevation by angels at the canonical hours, and her discovery by a priest who took her to his church for viaticum, where she died and was buried.[19] However, it did not yet situate her wilderness in Provence.

For this important development in the Magdalen’s Life, we must look to two vitae invented in the eleventh century to explain and support the presence of the Magdalen’s cultic center at the abbey of Vézelay.[20] The vita apostolica is the first narrative that relates the coming of Mary Magdalen and her companions to Provence, where they preached and converted the region.[21] It did not, however, include her retreat into the wilderness, focusing on her role as a missionary rather than penitent. It was the subsequent vita apostolica-eremitica that united the vita apostolica with the vita eremitica, creating the narrative in which the Magdalen traveled to Provence, and then, after converting Marseilles, retired to her cave in the wilderness.[22] It further localized her in Provence by stating she was buried in the church of St.-Maximin, from whence the monks of Vézelay claimed they had stolen (or rescued) her body.

We might look at a map and jokingly note the dearth of anything resembling a desert in Provence. But while it is certainly true that, originating in the eastern tradition, most Desert Fathers and Mothers did find their wildernesses in the desert areas of the Holy Land, the terminology used in the Old and New Testament as well as in Latin vitae to indicate such places is in fact ambiguous, meaning a wilderness as much as desert.[23] While Provence is not a sandy desert, it certainly includes wild uninhabited regions, and is thus a fitting place for eremitic retreat.

Finally, in the thirteenth century, these sources were combined in the Golden Legend, which presented the most developed and widely known version of the Magdalen’s vita.[24] Jacobus in fact included two versions of her Life. His longer—primary—narrative combined the vita apostolica-eremitica with the earlier vita evangelica (Sermo in veneratione sanctae Mariae Magdalenae) to form what is sometimes called the vita evangelico-apostolica (BHL 5450).”[25] His shorter version, as previously noted, is the vita eremitica or “Narrat Josephus.”[26]

The Magdalen’s legendary life in Provence—including both her preaching and her eremitical sojourn—was now accepted as fact. And from at least 1248, the site of her cave was identified as Sainte-Baume.[27] However, two final elements were required to initiate the flurry of Italian pictorial depictions of the eremitical Magdalen. The first was the creation and rise of the Mendicant Orders with their interest in promoting the Magdalen as an exemplar of penance.[28] This second occurred in 1279, when Charles of Salerno, the future Charles II, Angevin heir to the Kingdom of Naples and the County of Provence, ‘discovered’ Mary Magdalen’s body in the crypt of St.-Maximin, the place from whence Vézelay’s monks claimed to have stolen it centuries earlier. Seizing this opportunity to associate themselves with an important biblical and apostolic saint, who luckily enough already had a well-established narrative localizing her in their territory, the Angevin dynasty eagerly promoted the Magdalen’s cult both in Provence and in Naples.[29] On April 6, 1295, in a Papal Bull addressed to King Charles II, Pope Boniface VIII officially authenticated the recently discovered Magdalen relics at St.-Maximin, an act that sounded the death knell for the Vézelien cult.[30] In the same Bull, Boniface also transferred control of the Basilica of St.-Maximin and the priory at the cult site of Ste.-Baume from the Benedictine monks of the abbey of Saint-Victor in Marseilles to the Dominican Order at the request of King Charles II. St.-Maximin was classed as an Angevin Royal foundation, independent of episcopal control, with the number of friars there left to the king’s pleasure.[31] Today St.-Maximin is a parish church dedicated to the Magdalen.[32] Ste.-Baume, however, is still in Dominican hands and is an active pilgrimage site with an online presence.

Creation of the Eremitical Magdalen: Pictorial Hagiography in Central and Southern Italy

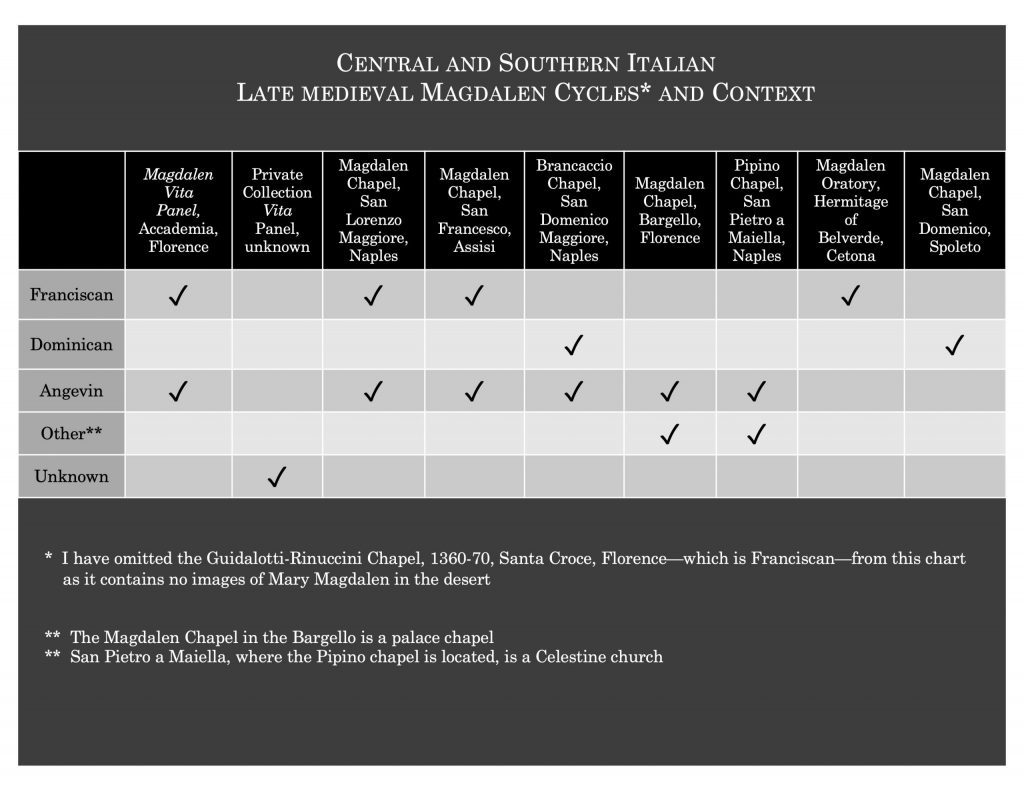

Table 2. Central and Southern Italian Late Medieval Magdalen Cycles and Context.

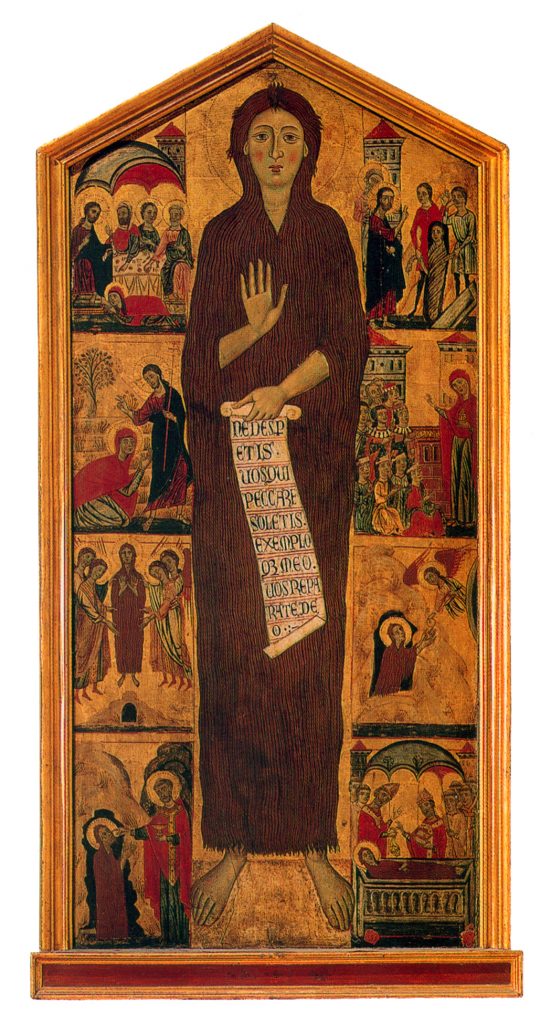

The Angevins’ powerful reach and the ascendant mendicant orders’ devotion to the Magdalen quickly spread her cult through Italy. Ten extant central and southern Italian narrative cycles depicting the Life of the Magdalen were painted in the years between c. 1280-c. 1400 (Table 2), varying considerably in scope and content.[33] In chronological order, these cycles are found on or in the Magdalen Vita Panel, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, c. 1280 (Fig. 1, hereafter referred to as the Accademia Vita Panel); the Magdalen Vita Panel, Private Collection, c. 1290 (Fig. 2, hereafter Private Collection Vita Panel);

Fig. 1. Magdalen Master, Magdalen Vita Panel, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence. Tempera on wood panel, 178 x 90cm, c. 1280. Inv. 1890 n.8466 (Photo: © public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

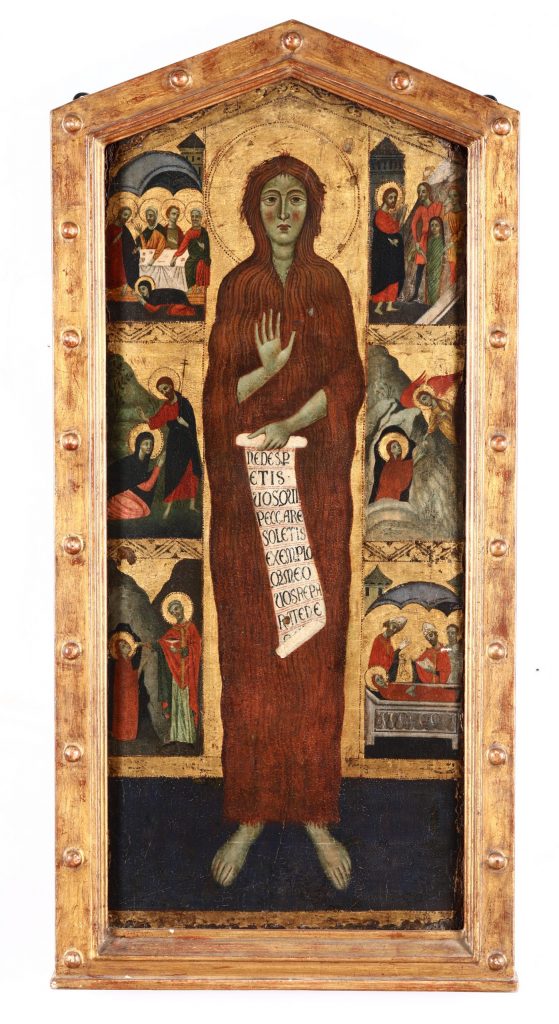

Fig. 2. Magdalen Master (?), Magdalen Vita Panel, Private Collection. Tempera on wood panel, 95.2 x 40.6 cm, c. 1290 (Photo: © Private Collection).

the Magdalen Chapel in San Lorenzo Maggiore, Naples, c. 1295-1300 (Fig. 3); the Magdalen Chapel in the Lower Basilica of St. Francis, Assisi, 1307-8 (Fig. 4); the so-called Brancaccio Chapel in San Domenico Maggiore, Naples, c. 1308-9 (Fig. 5); the Magdalen Chapel or Chapel of the Podestà in the Palazzo del Podestà (Bargello), Florence, 1321 (Fig. 6); the Pipino Chapel in San Pietro a Maiella, Naples, c. 1340-54 (Fig. 7); the Guidalotti-Rinuccini Chapel in Santa Croce Florence, 1360-70 (Fig. 8); the Oratory of the Magdalen at the Hermitage of Belverde, Cetona, c. 1400; and the Magdalen Chapel in San Domenico, Spoleto, c. 1400 (Fig. 9).

Fig. 3. Magdalen Chapel in San Lorenzo Maggiore, Naples, c.1295-1300 (Photo: © Author).

Fig. 4. Overview from nave of the Magdalen Chapel in the Lower Basilica of St. Francis, Assisi, 1307-8. Frescoes by Giotto(?) (Photo: © dvdbramhall https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/).

Fig. 5. Overview of the so-called Brancaccio Chapel in San Domenico Maggiore, Naples, c. 1308-9 (Photo: © Robert Rosinski).

Fig. 6. Overview of the Magdalen Chapel or Chapel of the Podestà in the Palazzo del Podestà (Bargello), Florence, 1321 (Photo: © Miguel Hermoso CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons).

Fig. 7. Overview of the Pipino Chapel in San Pietro a Maiella, Naples, c. 1340-54 (Photo: © Robert Rosinski).

Fig 8. Giovanni da Milano, south wall of Guidalotti-Rinuccini Chapel in Santa Croce, Florence, 1360-70 (Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

Fig. 9. Overview of the Magdalen Chapel in San Domenico, Spoleto, c. 1400 (Photo: © Silvio Sorcini, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons).

Six of these cycles are linked to the Angevins, five to the Franciscans, and two to the Dominicans—in overlapping circles of influence and with a varying degree of certainty.[34] While the provenance of the newly discovered Private Collection Vita Panel is unknown, it was very probably Franciscan, like the Accademia Vita Panel, which it closely reflects at a smaller scale.[35]

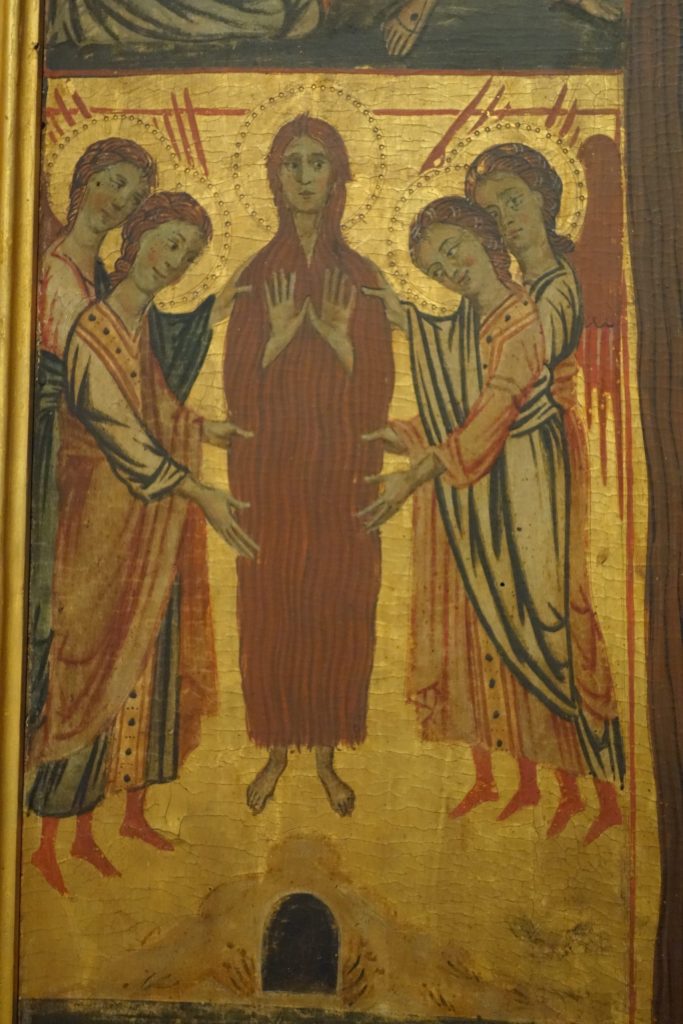

Table 3. Mary Magdalen in the Wilderness: Scenes Present in Each Cycle.

Of these ten cycles, all except for one—that in the Guidalotti-Rinuccini Chapel—include scenes from the Magdalen’s eremitical sojourn in the Wilderness of Provence (Table 3).[36] Indeed, some of them include multiple representations of the Magdalen as a desert saint. In total, there are four separate events occurring in the wilderness that appear in these Magdalen visual narratives. The first is The Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels, where we see her elevated to the heavens to hear “the glorious chants of the celestial hosts.”[37] The second is The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, which we will return to shortly. The third episode is The Magdalen Receiving a Mantle, which reflects the shorter, “Narrat Josephus” account in the Golden Legend. The last is the Magdalen’s Last Communion with St. Maximin set in the wilderness rather than inside a church, which is where it occurs in both versions of her written vita included by Jacobus.[38] It is worth noting that in addition to these narrative representations of the eremitical Magdalen, each of the two panel paintings depicting the Life of the Magdalen features, as its focal point, a large iconic image of the eremitical Magdalen covered only in her hair.

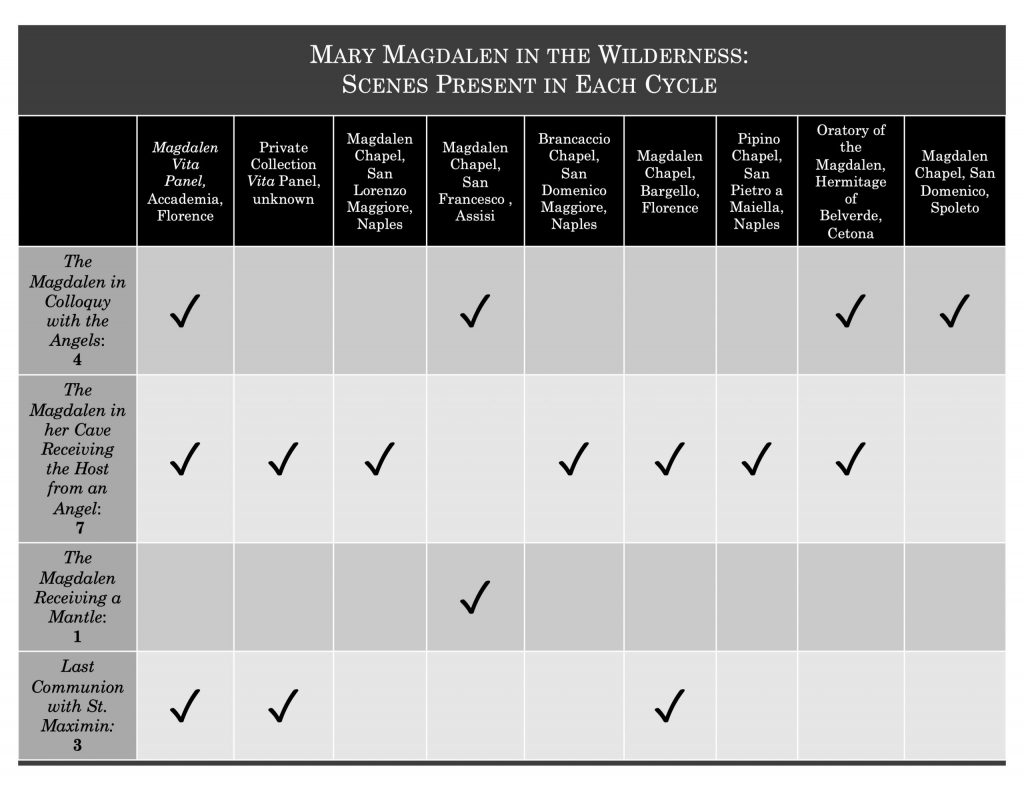

Based on the written vitae, one would expect the Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels to be the most frequently depicted event in her desert narrative. It concisely illustrates key aspects of the Magdalen’s sojourn in the desert. It reveals that her survival in this harsh environment was made possible by the grace of God, who sent his angels to elevate her daily at the seven canonical hours to hear their celestial music so that she required no physical sustenance.[39] Yet, surprisingly given its textual primacy, The Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels appears in just four of the nine cycles illustrating the Magdalen’s life in the desert—in two of the earliest: the Accademia Vita Panel, c. 1280 (Fig. 10), and in San Francesco, Assisi, c. 1307-8 (Fig. 11), and in the two latest: in the Oratory of the Magdalen, Cetona, and in San Domenico, Spoleto, both c. 1400 (Fig. 12). These are among the most extensive Magdalen cycles, ranging from six to eleven scenes, and all but the one in Spoleto include multiple scenes of the Magdalen’s sojourn in the desert.

Fig. 10. Magdalen Master, detail of The Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels, Magdalen Vita Panel, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (Photo: © Author).

Fig. 11. Giotto(?), The Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels, Magdalen Chapel in the Lower Basilica of St. Francis, Assisi, 1307-8 (Photo: © Stefan Diller / http://www.assisi.de/).

Fig. 12. The Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels, Magdalen Chapel in San Domenico, Spoleto, c. 1400 (Photo: © Silvio Sorcini, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons).

This is even more remarkable considering the fact that the Colloquy signifies one of the most typical of desert saint tropes to be found in the Magdalen’s hagiographic life—that is, the encounter of the desert saint with a holy man, to whom he (the desert saint is usually a “he”) recounts his story.[40] In the Golden Legend we read:

There was a priest who wanted to live a solitary life and built himself a cell a few miles from the Magdalene’s habitat. One day the Lord opened this priest’s eyes, and with his own eyes he saw how the angels descended to the already-mentioned place where blessed Mary Magdalene dwelt, and how they lifted her into the upper air and an hour later brought her back to her place with divine praises.

Wanting to learn the truth about this wondrous vision and commending himself prayerfully to his Creator, he hurried with daring and devotion toward the aforesaid place; but when he was a stone’s throw from the spot, his knees began to wobble, and he was so frightened that he could hardly breathe … So the man of God realized that there was a heavenly secret here to which human experience alone could have no access.[41]

And yet, despite the priest’s vital role in the written vita, where he serves as witness to—and verifier of—her sanctity, he is only depicted once in the painted hagiography: in the Magdalen Chapel in San Domenico, Spoleto (Fig. 12).

In fact, the painted iconography of the Colloquy is surprisingly not standardized, showing substantial variation between the four cycles. The Magdalen is flanked by two angels at Spoleto, but in the other cycles by four. She is shown frontally on the Accademia Vita Panel, and in the Cetona, but in Assisi she is shown in profile view, and at Spoleto in three-quarters view. In both Spoleto and Assisi she is depicted kneeling, while in Cetona and the Accademia Vita Panel she stands. The Magdalen’s hands are usually pressed together in a gesture of prayer, however on the Accademia Vita Panel she makes an orant gesture, palms facing outwards before her chest. Usually, she is pictured hovering above her cave, but in Cetona, she floats above a choir of music-making angels. As already noted, the priest appears only in Spoleto where the Magdalen inclines her head and seems to address him, as described in the written vita. In the other depictions however, she looks directly at the viewer, or upwards to the angels, indicating that we are now the witnesses.

This variety and deviation from the written narrative indicates that despite relating a narrative established in written texts, the iconographers responsible for visually presenting the Magdalen had their own agendas, and were keenly aware that changes could, and indeed, must be made, to best express the essence of the narrative in a visual medium.[42] As Cynthia Hahn has argued, “pictorial narrative is best understood as a partially independent version of the story, one that locates reception and interpretation in a markedly different medium.”[43] In a painting, the priest is unnecessary to authenticate the tale. The events unfold before the viewers’ eyes without the need for an intermediary figure to confirm them. The viewer thus replaces the priest as authenticator, and the focus is transferred to the Magdalen’s own experience of the desert than on the priest’s second-hand experience of observing and hearing it.

Fig. 13. Giotto(?), The Magdalen Receiving a Mantle, Magdalen Chapel in the Lower Basilica of St. Francis, Assisi, 1307-8 (Photo: © Stefan Diller / http://www.assisi.de/).

The most infrequently depicted event from the Magdalen’s period in the wilderness is The Magdalen Receiving a Mantle.[44] It is found only once, in the Magdalen Chapel in the Lower Basilica of San Francesco, Assisi (Fig. 13). This event comes from the shorter life in the Golden Legend: the vita eremitica. In this variant, a priest encountered the Magdalen in the wilderness. She asked him for a garment to cover her nakedness and then went to his church for Last Communion, and died.[45] As this vita is brief, and is presented by Jacobus as an afterthought, it is understandable that it had little impact on visual narratives. In fact, its rarity is such that the scene is frequently misidentified by scholars as Mary Magdalen Receiving the Mantle from the Hermit Zosimus.[46] This shows the continuing confusion between Mary Magdalen and Mary of Egypt. In the Life of Mary Magdalen this priest is unnamed; Zosimus is the hermit in the story of St. Mary of Egypt’s sojourn in the desert, the primary source for the eremitical Mary Magdalen.

Fig. 14. Magdalen Master, detail of Mary Magdalen Receiving Viaticum in the Wilderness from St. Maximin, Magdalen Vita Panel, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, c. 1280 (Photo: © Author).

Fig. 15. Magdalen Master (?), detail of Mary Magdalen Receiving Viaticum in the Wilderness from St. Maximin, Magdalen Vita Panel, Private Collection, c. 1290 (Photo: © Author).

Fig. 16. Mary Magdalen Receiving Viaticum in the Wilderness from St. Maximin, the Magdalen Chapel or Chapel of the Podestà in the Palazzo del Podestà (Bargello), Florence, 1321 (Photo: © Author).

The ongoing elision between the two desert-dwelling Marys can also be seen in the scene of Mary Magdalen receiving viaticum in the wilderness from St. Maximin, which is found in three of the cycles: the Accademia Vita Panel (Fig. 14), the Private Collection Vita Panel (Fig. 15), and the Magdalen Chapel in the Bargello, Florence (Fig. 16). This event is not present in the hagiographic accounts discussed previously, which all indicate that the Magdalen received Last Communion inside of a church: either that of St Maximin or of the priest who came upon her in the wilderness in the “Narrat Josephus” version. And indeed, the Magdalen Receiving Last Communion in a Church is depicted in an additional three cycles.[47] The episode of the Magdalen receiving viaticum in the desert must be the result of her further conflation with Mary of Egypt, whose legends do have her receiving Last Communion in the wilderness from Zosimus.[48]

Fig. 17. Attributed to Cenni di Francesco di ser Cenni, Mary Magdalen Receiving Viaticum in the Wilderness from St. Maximin, in the Gianfigliazzi Chapel (or San Benedetto Chapel) in Santa Trinità, Florence. Fresco, c. 1400 (Photo: © Author).

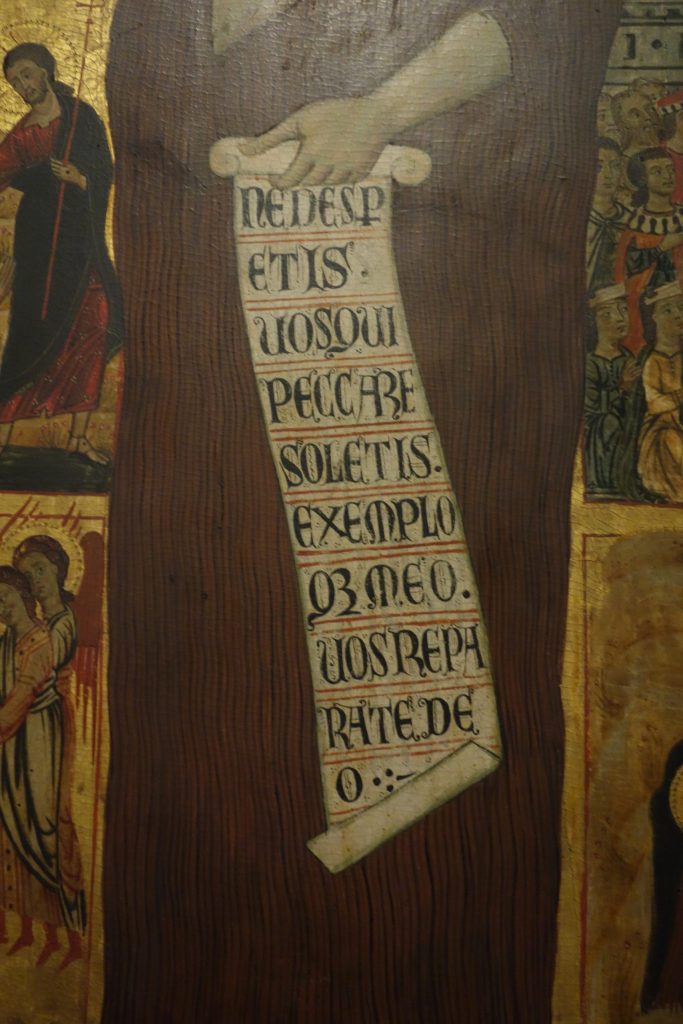

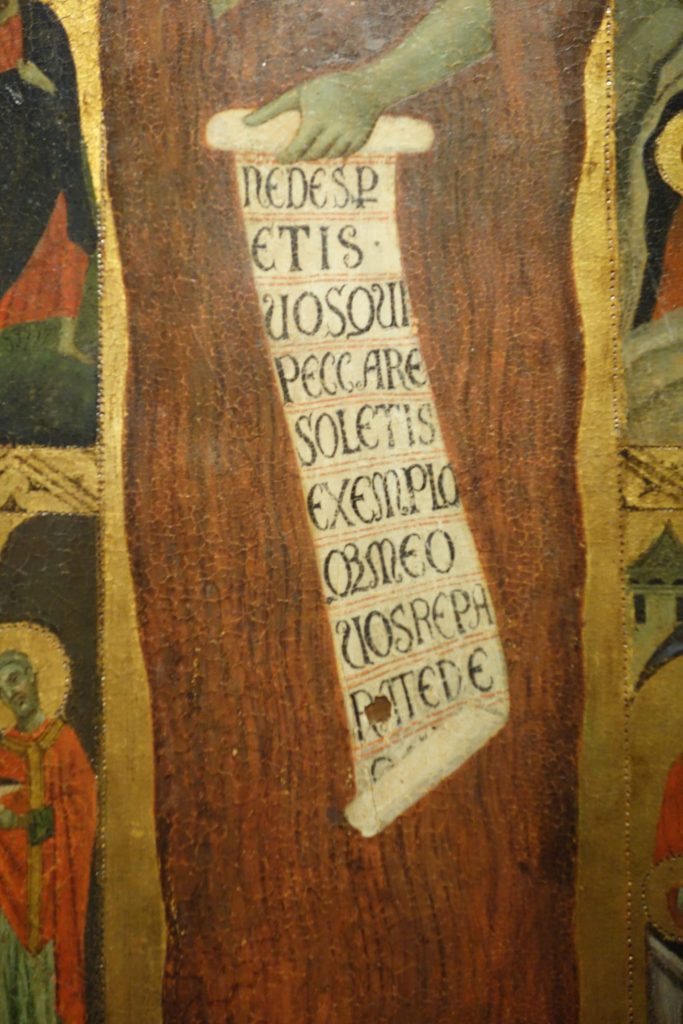

Notably, the three cycles that include the Magdalen’s Last Communion in the Wilderness are the three that have a Florentine (or probable Florentine, in the case of the private collection panel) provenance. The reason for this is not clear. Perhaps a written version of the Magdalen’s vita interpolating this episode from Mary of Egypt’s vita circulated locally and has been lost. Or, perhaps it became a local visual tradition independent of any textual counterpart. Whichever the episode’s origins—textual or visual—evidence that it had become established in Florentine visual tradition is provided by a fresco dating from about 1400 in the Gianfigliazzi Chapel (also called the San Benedetto Chapel) in Santa Trinita, Florence (Fig. 17).[49] Frequently misidentified as Mary of Egypt receiving viaticum from Zosimus, the desert saint receiving communion in her cave is clearly Mary Magdalen.[50] Not only is Mary of Egypt infrequently seen in narrative Italian frescoes in this period, the saint’s identity as the Magdalen is proclaimed by the banderole surrounding her in the fresco. It carries an inscription identical to that on the scroll displayed by the Magdalen in the central iconic images of both Magdalen vita panels: NE DESPERETIS VOS QUI PECCARE SOLETIS EXEMPLOQUE MEO VOS REPARATE DEO or “do not despair those of you who are accustomed to sin, and in keeping with my example, return yourselves to God” (Figs. 18 & 19).[51] The fact that the imagery of Magdalen Receiving Last Communion from St. Maximin in the Desert also first appeared on the Accademia Vita Panel, indicates this is the likely source for what remained a fairly localized visual tradition.[52]

Fig. 18. Magdalen Master, detail of Banderole, Magdalen Vita Panel, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, c. 1280 (Photo: © Author).

Fig. 19. Magdalen Master (?), detail of Banderole, Magdalen Vita Panel, Private Collection, c. 1290 (Photo: © Author).

The most depicted event from the Magdalen’s life in the wilderness by far is The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel. This episode is included in all but two of the late medieval cycles featuring the eremitical Magdalen.[53] It was also depicted independently of Magdalen cycles in manuscripts, in fresco, and on panels.[54] The iconography of this episode is remarkably consistent despite variations in media, scale and style (Figs. 20 & 21). It features a hirsute Magdalen shown in profile view, kneeling either inside her small cave or at its mouth, her arms are outstretched and bent, with her hands either pressed together in prayer, or held open to receive the Host from the angel. In all these images Mary faces towards the right side of the image, with her eyes raised towards the angel swooping down from above, bearing the host in its hands or, more frequently, held in a cloth.[55]

Fig. 20. Magdalen Master, detail of The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, Magdalen Vita Panel, Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence, c. 1280 (Photo: © Author).

Fig. 21. The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, so-called Brancaccio Chapel in San Domenico Maggiore, Naples, c. 1308-9 (Photo: © Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons).

The near universality of this scene in late medieval Magdalen cycles, and the uniformity of its iconographic presentation, bears careful consideration. This is particularly true because, unlike the other scenes we have discussed, a literary source for this event is not apparent. While the Magdalen Receiving Communion from St. Maximin in the Wilderness is not found in the written vitae of the Magdalen, its origins in Mary of Egypt’s vita are evident and—given the degree to which Mary Magdalen’s post-biblical life had been shaped to resemble the life of Mary of Egypt—the interpolation is understandable. That is not the case, however, with the Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel. Mary of Egypt’s vita is clear that she received communion only once during her sojourn in the desert—from the priest Zosimus, whom she told “since the day I came here I have not received the communion of the Lord.”[56]

Neither is it feasible to argue that this is an alternate means of depicting the Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels receiving “heavenly sustenance” at the seven canonical hours. Her vitae are clear that this sustenance was musical in nature and that she was lifted to the heavens to receive it. As Jacobus writes in the Golden Legend, “Every day at the seven canonical hours she was carried aloft by angels and with her bodily ears heard the glorious chants of the celestial hosts.”[57] The paintings’ insistent localizing of the Magdalen in her cave at Ste.-Baume, attended by a singular angel, combined with the corporeal nature of the host, all argue against such an interpretation. The fact that two cycles—those on the Accademia Vita Panel and in the Hermitage of Belverde in Cetona—include both the Colloquy with the Angels and the Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, makes this explanation entirely untenable.

Instead, the narrative of the Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel seems to be a new story, one invented in and for the pictorial medium.[58] It is an event that functioned in multiple ways to aid the spread of the Magdalen’s cult in Italy by the Angevins, Franciscans and Dominicans. It was present in the earliest Italian Magdalen cycle, the Accademia Vita Panel (c. 1280).[59] Although this panel’s original provenance is undocumented, its format, iconography and its dating—to immediately after the 1279 discovery of the St. Maximin Magdalen relics by Charles—all indicate it was commissioned for a Franciscan church, most likely, by an Angevin-affiliated patron with an interest in promoting the saint to whom the dynasty was devoted.[60] This large panel (178×90 cm)—with an eremitic central Magdalen holding a speaking scroll in which she exhorts sinners to follow her example and return to God—insistently emphases the Magdalen as a penitential exemplar, one of the key elements of her appeal to Franciscans.

This influential work of art seems to have established the new scene as virtually essential to the interpretation of the Magdalen as successful penitent. Its indispensability is evident when considering the Accademia Vita Panel in relation to the recently discovered, half-scale, Private Collection Magdalen Vita Panel (95.2 x 40.6 cm) (Fig. 22). As part of the reduction in size, the later panel was forced to reduce the eight scenes of her life to just six. Yet the iconographer, perhaps surprisingly, opted to delete two Provençal scenes that came from the written vitae—The Magdalen Preaching and the Colloquy—rather than leaving out the newly invented event of the Communion from an Angel.

Fig. 22. Magdalen Master (?), detail of The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, Magdalen Vita Panel, Private Collection, c. 1290 (Photo: © Author).

This brings us to what it was that gave this particular scene in the wilderness—one not found in the textual sources—its exceptional appeal. Both vita panels create interesting pairings in the registers in which these scenes appear. In the Accademia panel, it is located on the right side in the third register from the top, with the angel appearing as if entering from the space outside the altarpiece on the right. This angel is in the process of placing the Host into the Magdalen’s gratefully outstretched hands. On the left side, the previous scene is The Magdalen in Colloquy with the Angels. The paired events are ones that each show—in different ways—the favor she has received from God, and how he spiritually sustained her in the desert: through the angelic provision of heavenly music and with the corporeal body of Christ—a reward for her successful penance.

In the private collection panel, the representation of the Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, again on the right but now in the middle register, is virtually identical to that in the earlier panel.[61] However, with the deletion of the Magdalen Preaching and the Colloquy, it is paired instead with the biblical Noli me tangere. This pairing makes it clear that despite coming from different sources and different times in her narrative, these are, in fact, parallel scenes, compositionally and in terms of content. Both events have the Magdalen kneeling at the left side facing to the right, silhouetted against an almost identically formed geological feature: a grassy hill on the left, and her mountainous cave dwelling on the right. In the Noli, with hands clasped in front of her in prayer, she addresses the Risen Christ as first witness to the Resurrection, the Apostolorum Apostola: “apostle to the apostles.” In the Communion it is the Body of Christ in the form of the Host that she reaches towards. As Hahn argues, “in pictorial hagiography, topoi often make reference to other, similar images, thereby changing recognizability and clarifying meaning.”[62] What the compositional similitude makes evident is that these images depict essentially the same thing—the Magdalen reaching for the body of Christ—and that God has given her privileged access to it due to the success of her penance.

In fact, while a retreat to the wilderness is a typical feature of the penitential vitae of desert saints, and this is certainly the reason why the famously penitent Magdalen’s vita came to incorporate this trope, the Magdalen’s sojourn in the desert was less penitential in nature than it was contemplative, it is even described as such by Jacobus who states that the Magdalen withdrew to the wilderness “wishing to devote herself to heavenly contemplation.”[63] During her thirty years in the wilderness she did not undergo any of the physical torments and constant temptations that were the norm for the Desert Fathers and even Mary of Egypt, on whom her story is based.[64] Denva Gallant calls their solitary battle against the devil, “a defining feature of the lives of the Desert Fathers and Mothers” and calls “the inhospitable and infertile desert …both the locale and the instrument of penance.”[65] Susanna Elm describes the desert existence as “a world of constant, relentless battle, of ceaseless resistance against the sheer overwhelming force of the environment, as well as the equally ceaseless resistance against the demons that assailed the ‘inner man.’”[66] And yet, despite her solitude this was not the experience of the Magdalen, whose hermitage was, according to Jacobus, “made ready by the hands of angels.”[67] Her period in the wilderness is characterized by the contemplation of heavenly things, of sustenance by God. Instead of being a time of trial and penitential suffering, it confirmed the success of her penance and the forgiveness she had received from Christ himself when she knelt at his feet in the House of the Pharisee.

The Magdalen’s successful penitence is revealed most explicitly through her action in this scene: the reception of Communion. This sacrament was critically important to penitential theology, which had been reformulated by Pope Innocent III at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215. Every member of the church was required to feel contrition, make confession, and fulfill their penance before they could receive Holy Communion, which they were to do at least once annually, preferably at Easter.[68] In her book on Eucharistic devotion, Miri Rubin discussed the interconnectedness of penance and host reception:

Penance was essentially private…The eucharist which followed it, however, introduced the universal, cosmic, timeless, supernatural intervention in the world which legitimated and explored the very grace to which access was made through the sacrament of confession and penance.[69]

Communion provided the repentant sinner with access to grace. It was a public proclamation that their penance had been successful, and their sins forgiven. These images of Mary Magdalen receiving the Host from no mere mortal, but an angel, make this divine forgiveness particularly explicit.

Thus, the Magdalen was presented as a message of hope for penitent viewers. This was one of the critical components of the Magdalen’s appeal to the mendicants, in particular to the Franciscan Order. The most frequent themes for Franciscan preaching in the period included repentance, contrition, and confession of sins,[70] and they believed this mandate to preach penance came directly from Pope Innocent III.[71] Interestingly, in San Lorenzo Maggiore, the major Franciscan church of Naples, the earliest fresco cycle to include this event adds an inscription reading SIC FECIT PENITĒ/[N]TIA[M] or “so she did in penitence,”[72] testifying to the Franciscan’s penitential reading of this event (Fig. 23).

![The fresco in the lunette on the right wall of the chapel in San Lorenzo with the Magdalen facing right, kneeling in the mouth of her cave receiving Communion from an angel who is flying in from the left. There is an inscription reading SIC FECIT PENITĒ/[N]TIA[M] or “so she did in penitence.”](https://differentvisions.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/1356/2025/06/Wilkins-Fig.-23-919x1024.jpg)

Fig. 23. The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, Magdalen Chapel in San Lorenzo Maggiore, Naples, c.1295-1300 (Photo: © Author).

In fact, the importance of the Eucharist is such that considering both the Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel and Receiving Last Communion from St Maximin, the Magdalen receives the Host in every cycle. And in four of them, the presence of this new scene means that she receives the Eucharist not once, but twice.[73] As we explored before, this underscores the exceptional relationship between Mary Magdalen and Christ’s body expressed in both the Gospels and her vitae. Weeping on Christ’s feet and drying them with her hair, anointing him with precious ointments, reaching for him after the Resurrection in the Noli me tangere, the Magdalen is constantly touching, or trying to touch Christ. These images of the Magdalen receiving the Eucharist from an angel continue the intimacy between Mary Magdalen and Christ’s body—so key to her biblical narrative—into her post-biblical experience in the wilderness.

The scene of the Magdalen in her cave receiving the Eucharist from an angel also served to firmly localize the Magdalen in Provence, in her cave at Ste.-Baume. This was particularly important for the Angevin rulers of Provence and Naples, who, after Charles’ discovery of her relics adopted her as their patron saint, and indeed promoted her as a kind of saintly ancestor.[74] This localization was also crucially important for the Dominicans who, thanks to Angevin patronage, controlled her two pilgrimage sites in Provence from 1295 onwards. They were the custodians of Ste.-Baume where she lived in the wilderness, and St.-Maximin where she was buried and her relics were located. While it is true that any of the scenes of the Magdalen in the wilderness could, and to an extent probably did, function this way, the iconography of the angelic communion is unusual in its consistent placement of this event within the Magdalen’s cave of Ste.-Baume. In fact, over half of the Magdalen cycles contain multiple images depicting the Magdalen in her wilderness in Angevin Provence, the reiteration underscoring the importance of the location. In the instances, however, where only one wilderness scene appears, it is this one, as it came to act as a kind of shorthand for her experience in the wilderness.

The narrative of the Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel functioned multivalently in cycles depicting the Life of the Magdalen. By emphasizing the location of the Magdalen’s penitential sojourn in Provence, it supported Angevin interests by situating her within Angevin territory, where her relics had recently been found by the future King Charles II. By further situating this retreat from the world at Ste.-Baume, the cultic and pilgrimage center newly in Dominican control thanks to the Angevins, it similarly promoted Dominican interests. It communicated the Magdalen as the exemplar of perfect penitence: an interpretation critical to both Dominican and Franciscan promotion of her cult. Lastly, it reinforced the intimate link between Mary Magdalen, first witness to the resurrection, and the body of Christ.

Ultimately the eremitic Magdalen is a figure fraught with ambiguities. Her hagiography—both written and pictorial—draws on tropes familiar from the vitae of other eremitic saints, yet in many ways she consistently defies them: in her gender, in her location, in the time in which she lived. Most importantly, she is presented as a penitent like all other desert saints—indeed, she was understood as the “perfect penitent”—yet she is radically unlike them. Their ordeals in the desert served as their major acts of penance, the Magdalen’s penance, in contrast, was already complete long before her retreat to Ste.-Baume. Absolution had been granted to her by Christ when he said to her, “Thy sins are forgiven thee.” This difference is most powerfully visually evinced in her (repeated) reception of the Host while in the wilderness.

References

| ↑1 | Jacobus de Voragine, The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints, 2 vol., trans. and intro. William Granger Ryan (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), I, 380. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The scholarship on eremitic desert saints is extensive and beyond the scope of this essay to catalogue. For a brief overview on “hairy hermits” see Laura Fenelli, “Gli eremiti pelosi,” in Atlante delle Tebaidi e dei temi figurativi, ed. Alessandra Malquori, with Manuela de Giorgi and Laura Fenelli (Florence: Centro Di, 2013), 171-172. |

| ↑3 | For the phenomena of ‘holy harlots’ and ‘desert mothers’ see Ruth Mazo Karras, “Holy Harlots: Prostitute Saints in Medieval Legend,” in Journal of the History of Sexuality 1 no. 1 (1990): 3-32; Benedicta Ward, Harlots of the Desert: A study of repentance in early monastic sources (Kalamazoo MI: Cistercian Publications Inc., 1987); Lynda L. Coon, Sacred Fictions: Holy Women and Hagiography in Late Antiquity (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997), 71-94; Philip C. Almond, Mary Magdalene: A Cultural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023), 63-70 |

| ↑4 | For context on the rise of the desert movement, see Alexander Ryrie, The Desert Movement: Fresh perspectives on the spirituality of the desert (Norwich, UK: Canterbury Press, 2011). |

| ↑5 | On the link between eremitism and penance, see Ward, Harlots of the Desert, 1-9. |

| ↑6 | No indication of the nature of her sin is provided in the Bible. |

| ↑7 | For the Life of Mary of Egypt, see Ward, Harlots, 26-56; Almond, Mary Magdalene, 67-69; Karras, “Holy Harlots,” 6-10; Jacobus, The Golden Legend, I, 227-9; Jean Misrahi, “A Vita Sanctae Mariae Magdalenae (BHL 5456) in an Eleventh-Century Manuscript,” Speculum 18, no. 3 (July 1943): 336. |

| ↑8 | For the history of Mary Magdalen and Vézelay through hagiography, liturgical texts, historical texts, etc., see Victor Saxer, Le Dossier Vézelien de Marie Madeleine: Invention et Translation des reliques en 1265-1267 (Subsidia hagiographica, n.57) (Brussels: Société des Bollandistes, 1975); Neal Raymond Clemens, “The Establishment of the Cult of Mary Magdalen in Provence, 1279-1543” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1997), 19-65. |

| ↑9 | Jacobus, The Golden Legend, I, 374-383; 376-383 for the legendary material on her life after the death of Christ. |

| ↑10 | For a summary of this complex material see Katherine L. Jansen, The Making of the Magdalen: Preaching and Popular Devotion in the Later Middle Ages (Princeton University Press: Princeton NJ, 2000), 36-41. For an extended discussion of these hagiographic materials and how Jacobus made use of them see Almond, Mary Magdalene, 56-111; as well as Seth J.A. Alexander, “The Magdalene of Medieval Hagiography,” in Mary Magdalene from the New Testament to the New Age and Beyond, ed. Edmondo F. Lupieri (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 176-188. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004411067_011. |

| ↑11 | BHL refers to the Bibliotheca Hagiographica Latina. On the vita eremitica: the text of BHL 5453, 5454 and 5455 have been transcribed in J.E. Cross, “Mary Magdalen in the Old English Martyrology: The Earliest Extant ‘Narrat Josephus’ Variant of Her Legend.” Speculum 53, no. 1 (Jan. 1978): 20-25. The text of BHL 5456 has been transcribed in Misrahi, “A Vita Sanctae Mariae Magdalenae,” 338-339. Cross dated this text to the middle of the ninth century, while Misrahi dated it to the eleventh century, citing the ninth century as possible. The earlier dating is now generally accepted, as seen in Jansen and Almond. Cross, “Mary Magdalen in the Old English Martyrology,” 20; Misrahi, “A Vita Sanctae Mariae Magdalenae,” 337; Jansen, The Making of the Magdalen, 37; and Almond, Mary Magdalene, 57. On the vita evangelica (BHL 5439): BHL 5440 is a version of this sermon truncated at the end. BHL 5441 has the addition of a metric prologue, and BHL 5441 b and c have different endings. For more about this text, see Dominique Iogna-Prat, “La Madeleine du Sermo in veneratione sanctae Mariae Magdalenae attribué à Odon de Cluny,” Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome Moyen Age. La Madeleine (VIIIe-XIIIe siècle) 104, no. 1 (1992): 37-70; Dominique Iogna-Prat, “‘Bienheureuse Polysémie’ La Madeleine du Sermo in veneratione sanctae Mariae Magdalenae attribué à Odon de Cluny,” in Marie Madeleine dans la mystique, les arts et les lettres, ed. Eve Duperray (Paris: Beauchesne, 1989), 21-31; Victor Saxer, “Un manuscrit décémbre du sermon d’Eudes de Cluny sur Ste. Marie-Madeleine,” Scriptorium 8 (1954): 119-23. Most recently see Almond, Mary Magdalene, 70-77. Iogna-Prat dates this to between 860 and 1030, Jansen to the late ninth or early tenth century and Almond to between 860 and 1050. Iogna-Prat, “‘Bienheureuse Polysémie,’” 22; Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 38; Almond, Mary Magdalene, 71. |

| ↑12 | Traditionally attributed to Odo of Cluny it was likely written by an author from Vézelay. Iogna-Prat does not believe the text was written by Odo or that it is from Cluny, proposing an origin at Vézelay. Jansen maintains its Cluniac origin, but not the attribution to Odo. Almond refers to the author as ‘pseudo-Odo’ and says he may have been working in Vézelay. Iogna-Prat, “Madeleine du Sermo,” 42; Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 38; Almond, Mary Magdalene, 71. |

| ↑13 | Jacobus, The Golden Legend, I, 381. Cross, “Mary Magdalen in the Old English Martyrology,” 17. The Josephus to whom it was incorrectly attributed is the Jewish Roman historian Josephus (37-100). Almond, Mary Magdalene, 61. |

| ↑14 | Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (New York: Riverhead Books, 1993), 117. Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 37. For more on the vita eremitica see Almond, Mary Magdalen, 57-70. Given the origins of the vita in Southern Italy, and Mary of Egypt was originally an Eastern saint, it has been suggested that Greek monks fleeing to the West may have been influential in this process, with Jansen suggesting that it may have been the work of a Cassianite monk. Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 37; LaRow, “The Iconography of Mary Magdalen,” 152-158. |

| ↑15 | Ward, Harlots, 28. |

| ↑16 | For an English translation of the Greek Life of Mary of Egypt attributed to Sophronius, see Holy Women of Byzantium: Ten Saints’ Lives in English Translation, ed. Alice-Mary Talbot, trans. Maria Kouli (Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1996), 65-93. For a discussion of questions regarding the attribution to Sophronius, see ibid, 66. For an English translation of the Latin translation of Sophronious, which was attributed to Paul, deacon of Naples, see Ward, Harlots, 35-56. |

| ↑17 | A summary of the literature on the Vitae Patrum is beyond the scope of this article. For an overview of the literature and transmission of the Vitae Patrum: Eva Schulz-Flügel, “Zur Entstehung der Corpora Vitae patrum,” in Studia patristica 20: Papers Presented to the Tenth International Conference on Patristic Studies Held in Oxford, 1987, 2: Critica, Classica, Orientalia, Ascetica, Liturgica, ed. Elizabeth A. Livingstone (Leuven: Peeters, 1989), 289–300, as cited in Denva Gallant, “Into the Desert: Demons, Spiritual Focus, and the Eremitic Ideal in Morgan MS M.626,” Gesta 60, no. 1 (Spring 2021): 103 n.9. See also Monika Studer, “Vitaspatrum – A Short Summary” Œuvres Pieuses Vernaculaires à Succès (2012): 1-8 https://opvs.irht.cnrs.fr/index.html%3Fq=fr.html. For Cavalca’s vernacular translation,Domenico Cavalca, Vite dei santi Padri, critical edition ed. Carlo Delcorno (Florence: SISMEL—Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2009). See also, Carlo Delcorno, tradizione delle “Vitae dei santi padri.” Classe di scienze morali, lettere ed arti 92 (Venice: Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, 2000) and Carlo Delcorno, “Cavalca, Domenico,” in Dizionario biografico degli italiani 22 (1979): https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/domenico-cavalca_(Dizionario-Biografico)/. |

| ↑18 | This trope in which the eremitic saint narrates their life to another is common in the Lives of the Desert Fathers and can be seen also in Jacobus’ description of Mary Magdalen’s tenure in the desert. Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑19 | Haskins, Myth and Metaphor, 117. |

| ↑20 | For the Vézelien documents on the Magdalen see Saxer, Le Dossier Vézelien. |

| ↑21 | BHL 5443-9. Published as “Ancienne vie de Sainte Marie-Madeleine” in Étienne-Michel Faillon, Monuments inédits sur l’apostolat de Sainte Marie-Madeleine en Provence: et sur les autres apôtres de cette contrée, Saint Lazare, Saint Maximin, Sainte Marthe, les saintes Maries Jacobé et Salomé, 2 vols. (Paris: J.P. Migne, 1859), vol. II: pièces justificatives, 433-436. See also Guy Lobrichon, “Le dossier magdalénien aux XIe-XIIe siècles, Èdition de trois pièces majeures,” Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome Moyen Age. La Madeleine (VIIIe-XIIIe siècle) 104, no. 1 (1992): 163-180. https://doi.org/10.3406/mefr.1992.3222. For a somewhat expanded description of the events in the vita apostolica, see Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 38-39, 52-53. |

| ↑22 | BHL 5443-5448. |

| ↑23 | In ancient Hebrew, terms used include midbar and arabah. In Greek, they include eremos or eremia. In the vita eremitica Beatae Mariae Magdalenae (BHL 5456) it says that she retires to heremi solitudinem. In the Golden Legend, Jacobus refers to the place to which the Magdalen retreats as asperrimum eremum—translated by Ryan as “empty wilderness,” but which can also be translated as harshest desert, in an illustration of the mutability of the terminology. On this ambiguity with regards to the Latin desertum, see Denva Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum: The Lives of Desert Saints in Fourteenth-Century Italy (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024), 9. |

| ↑24 | See Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 374-383, for his entire life of Mary Magdalen. Life In addition to these two vitae, the Golden Legend life of the Magdalen includes various miracles performed by the saint after her death, most involving relics at Vézelay. Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 381-383. |

| ↑25 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 374-381; Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 53 n14. |

| ↑26 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 381. Cross, “Mary Magdalen in the Old English Martyrology,” 17. |

| ↑27 | Salimbene de Adam O.F.M. (1221-c. 1290) went to Ste.-Baume on pilgrimage in 1248 as described in his chronicle, and King Louis IX of France did so in 1254 on his return from the Seventh Crusade as described by Jean de Joinville. Misrahi, “A Vita Sanctae Mariae Magdalenae,” 337; Clemens, “Establishment of the Cult,” 208; Edmunds, “La Sainte-Baume,” 17-18. However, Jacobus de Voragine, writing c. 1260, does not specify Ste.-Baume as the location, so there must have still been some question at that time. Edmunds claims there are late twelfth-century references to the location, but they do not clearly identify the cave as Sainte-Baume. |

| ↑28 | The reasons for these groups’ great devotion to the Magdalen can only be touched on here. The essential text on mendicant devotion to the Magdalen is Katherine L. Jansen, The Making of the Magdalen. See also, Sarah Stewart Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently Than the Rest: The Magdalen Cycles of Late Duecento and Trecento Italy” (PhD diss., Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 2012), 35-39 (Mendicant overview), 37-50 (on Franciscans) and 50-60 (on Dominicans). Additionally, Denva Gallant’s discussion on the mendicant orders’ great interest in and promotion of the eremitic ideal at precisely this time—supporting a general resurgence of interest in eremitism in this period—offers another angle for future investigation. Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum, 3-4. |

| ↑29 | Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 25-35. |

| ↑30 | Faillon, Monuments inédits, vol. II: Pièces justificatives. 815-820, doc. 89. Clemens argued that in doing this, Boniface VIII was explicitly acceding to Charles’ wishes. Clemens, “Establishment of the Cult,” 76-80. |

| ↑31 | Clemens, “Establishment of the Cult,” 80-82. Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 53-54. For documents relating to Saint-Maximin and its early history, see Faillon, Monuments inédits, vol. II: pièces justificatives, 663-688, docs. 31-44. |

| ↑32 | The Magdalen’s supposed relics are still located in this church. |

| ↑33 | It has been suggested that a fragment of an even earlier Italian cycle exists in the Chapel (or Ex-Church) of S. Barnaba at the Ospedale della Misericordia e Dolce, Prato. While one narrative image does exist, depicting the Magdalen receiving Communion from an Angel, it is not clear that it was part of a larger Magdalen cycle, nor is it securely dated. On this little-studied, ruinous fresco, see: Giuseppe Marchini, “Affreschi inediti del Duecento a Prato”, in Rivista d’Arte 19 (1937): 163 (dated second half of the 13th c.); Marilena Mosco, “Immagini della leggenda dal XIII al XVI secolo,” in La Maddalena tra sacro e profano: da Giotto a De Chirico, ed. Marilena Mosco (Florence: Casa Usher, 1986), 31 (dated 1250); Maria Pia Mannini,“Lo spedale della Misericordia e Dolce. Le collezioni d’arte”, in Lo Spedale della Misericordia e Dolce di Prato ed. Francesca Carrara, Maria Pia Mannini (Prato, Masso delle Fate, 1993): 86 (dated first half of the 13th c.); Esther Diana, “The «Misericordia e Dolce» Hospital of Prato: A Physical and Symbolic Space (1218-2013)” in The Medieval and Early Modern Hospital: A Physical and Symbolic Space, eds. Antoni Conejo da Pena and Pol Bridgewater Mateu, 239-254 (Rome: Viella, 2023), 240 (dated first half of the 13th c.). The last two scholars are the only ones who suggest that the fresco is part of a larger cycle, and no reason is given for this or for the progressively earlier dating. |

| ↑34 | The cycles linked to the Angevins are the Accademia Magdalen Vita Panel; San Lorenzo Maggiore, Naples; San Francesco, Assisi; San Domenico, Naples; Bargello, Florence; and San Pietro a Maella, Naples. The cycles linked to the Franciscans are Accademia Magdalen Vita Panel; San Lorenzo Maggiore, Naples; San Francesco, Assisi, Santa Croce, Florence; and the Hermitage of Belverde, Cetona. The cycles linked to the Dominicans are those at San Domenico, Naples and San Domenico, Spoleto. |

| ↑35 | On the ‘new’ panel see Sara Penco, “Catalog entry 3.9,” in Maddalena. Il mistero e l’immagine, exhib. cat., eds. Cristina Acidini, Gianfranco Brunelli, Fernando Mazzocca, and Paola Refice (Milan: Silvana Editoriale, 2022), 437-38; Sarah S. Wilkins, “Late Medieval Vita Panels and Mary Magdalen as a Gendered Model of Penitence,” in Women and Gender in Trecento Art & Architecture: Images, Ideals, Realities, ed. Judith Steinhoff (Turnhout: Brepols, forthcoming 2025). |

| ↑36 | The program for the five-fresco Magdalen cycle in the Guidalotti-Rinuccini Chapel is unusual, pairing it with a cycle of the Life of the Virgin, and concentrating not on the legendary Magdalen, but on the Magdalen as revealed in the Gospels. The scenes are the Supper in the House of the Pharisee, Christ in the House of Mary and Martha, Raising of Lazarus, Noli me tangere (with the Three Marys at the Tomb on the right) and the Miracle of Marseilles. This last scene is the only one to treat her legendary life and depicts events occurring prior to her sojourn in the desert. On this cycle see Michelle A. Erhardt, “Two Faces of Mary: Franciscan Thought and Post-Plague Patronage in the Trecento Fresco Decoration of the Guidalotti-Rinuccini Chapel of Santa Croce, Florence” (PhD diss., Indiana University, 2004); and Michelle A. Erhardt, “The Magdalene as Mirror: Trecento Franciscan Imagery in the Guidalotti-RInuccini Chapel, Florence,” in Mary Magdalene, Iconographic Studies from the Middle Ages to the Baroque, eds. Michelle A. Erhardt and Amy M. Morris (Leiden: Brill, 2012), 21-44. |

| ↑37 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑38 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380-381. Some of the cycles do instead follow the written accounts and depict her receiving Communion in a church interior. |

| ↑39 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑40 | Fenelli, “eremiti pelosi,” 172. It is also worth noting that this trope, although seen typically for male desert saints, would have seemed quite ‘natural’ to a hagiographer to gender-flip, given that late medieval holy women and mystics usually recounted their Lives to male confessors. |

| ↑41 | Jacobus, The Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑42 | An essential source on pictorial hagiography is Cynthia Hahn, Portrayed on the Heart: Narrative Effect in Pictorial Lives of Saints from the Tenth through the Thirteenth Century (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2001), 29-58, esp. 45ff. |

| ↑43 | Ibid, 45. |

| ↑44 | For a recent discussion of this iconography and its origins, see Penny Howell Jolly, “Gender, Dress, and Franciscan Tradition in the Mary Magdalen Chapel at San Francesco, Assisi,” Gesta 58, no. 1 (Spring 2019): 8-12. https://doi.org/10.1086/701601. |

| ↑45 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380-1. |

| ↑46 | Elvio Lunghi, The Basilica of St. Francis in Assisi (New York: Riverside Book Company, Inc., 1996), 151; Osvald Sirén, Giotto and Some of His Followers, trans. Frederic Schenck (New York: Hacker Art Books, 1975), 95; Bernard Berenson, Italian Pictures of the Renaissance: A List of the Principal Artists and Their Works, with an Index of Places (New York: Phaidon Publishers, 1963), 80; Francesca Flores D’Arcais, Giotto, trans. Raymond Rosenthal (Milan; New York: Motta; Abbeville Press, 1995), 276; Edi Baccheschi, The Complete Paintings of Giotto (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1966), 111; Roberto Salvini, All the Paintings of Giotto Part 2, trans. Paul Colacicchi (New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc, 1964), 88; Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, A New History of Painting in Italy, 3 vol. (London: Dent; New York: Dutton, 1908), vol. 1, 315 n2. |

| ↑47 | San Francesco, Assisi; San Pietro a Maiella, Naples; San Domenico, Spoleto. The Magdalen Chapel in the Bargello shows her receiving viaticum in the desert but then being blessed in the church. Please note that this scene of the Magdalen receiving viaticum in a church is not included in Table 3 which exclusively contains the events in the desert. |

| ↑48 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 227-229. |

| ↑49 | This is the first chapel on the right side when facing towards the altar. The sinopia for this work is displayed on the opposite wall. The fresco is sometimes attributed to Cenni di Francesco di ser Cenni (active 1369/70-1415). |

| ↑50 | Mosco, “Immagini della leggenda,”, 31; Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 235 n.128. |

| ↑51 | Translation from Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 234. No literary source for this inscription is known, but it is extensively and exclusively identified with the Magdalen from its first (known) appearance in 1280. For more on this see Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 71-73. |

| ↑52 | This iconography is also seen in Jacopo del Casentino (Florentine, active c. 1320-1349), Coronation of the Virgin Triptych, Kunstmuseum Bern. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jacopo_del_casentino,_incoronazione_di_maria,_1325-30_ca..JPG#/media/File:Jacopo_del_casentino,_incoronazione_di_maria,_1325-30_ca..JPG. A later work showing this iconography is the historiated B on fol. 298v of the Piccolomini Breviary, attributed to the Florentine artist Mariano del Buono di Jacopo (1433-1504), Italy, Lombardy, c. 1475. MS M.799. Morgan Library. The text is the collect from first Vespers on 22 July, the feast of Mary Magdalen. https://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/50/145066. A variation on this imagery which features the Magdalen receiving communion in a cave, with the priest emerging from an adjacent church, is seen in another Florentine work. Gherardo Starnina (c. 1360-13413), predella of the Altarpiece of Angelo Acciaiuoli, 1407. Previously in the Certosa dell Galluzzo Monastery, Florence, today in the Musée des Hospices civils de Lyon, France. https://theindex.princeton.edu/s/view/ViewWorkOfArt.action?id=371EAE40-6571-432B-9990-6F3CB485EFD4. A Northern German depiction of this event does exist: Bertram von Minden (Workshop?), right exterior wing (middle) of Altarpiece with 45 Scenes of the Apocalypse, c. 1400. Acc. No. 5940-1859. Victoria and Albert Museum. https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O89176/altarpiece-with-45-scenes-of-altarpiece-master-bertram/#object-details. The iconography, however, is quite different, with no cave. |

| ↑53 | It is absent only in the Magdalen Chapels of San Francesco, Assisi, and of San Domenico, Spoleto. |

| ↑54 | For example: The Magdalen Receiving Communion from an Angel, Missale et horae ad usum Fratrum Minorum, 14th c, Italian. BnF Latin 757, fol. 343v. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8470209d; Cristoforo di Bindoccio-Meo di Pero, Communion of Mary Magdalen, 1393, diocese of Grosseto (Tuscany). https://www.beweb.chiesacattolica.it/benistorici/bene/4608709/Cristoforo+di+Bindoccio-Meo+di+Pero+%281393%29%2C+Comunione+di+Maria+Maddalena#action=ricerca/risultati&view=elenco&locale=it&ordine=&liberadescr=comunione+maddalena&liberaluogo=&ambito=CEIOA&dominio=1&secoloRomano=XIV&highlight=Comunione&highlight=Maddalena; Workshop of Pietro Lorenzetti (Italian, Sienese, active 1280–1348), The Last Communion of St. Mary Magdalene, n.d. tempera on panel, 27 x 18 ½ in.; 68.6 x 47 cm. Gift of Robert Lehman, 1945.103. The Joslyn Art Museum, Nebraska. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Workshop_of_Pietro_Lorenzetti_-_Saint_Mary_Magdalene_Receiving_the_Host_from_an_Angel,_1945.103.jpg. I have recently discovered that this scene also appears in a mid-trecento (post-Giotto) fresco in the apse of the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua. |

| ↑55 | The sole exception I am aware of is the Joslyn Museum panel, which matches this description in all regards except that the image is reversed, with Mary Magdalen facing towards the angel on the left. As this panel was likely the wing of a triptych or polyptych, I would suggest that it was the interior right wing, and that the image has been reversed so that the Magdalen faces towards Christ in the central image, perhaps the Crucifixion or the Virgin and Child. A technical exam of the work might be elucidating in this regard. |

| ↑56 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 228. |

| ↑57 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑58 | In addition to written sources, I have also sought textual and visual sources for this story featuring other saints (preferably Desert Fathers) receiving angelic communion but have not found any to this point except for in Morgan MS M.626 (Vitae Patrum) fol. 89v., in the Life of Onuphrius, where, on the left, Paphnutius of Egypt receives Communion from an Angel. Dated mid-fourteenth century, this postdates the Magdalen iconography and does not greatly resemble it. http://host.themorgan.org/icaimages/6/m626.089va.jpg. |

| ↑59 | On the panel more generally see Wilkins, “Late Medieval Vita Panels.” This may not, however, be the earliest appearance of this episode. The fresco in Prato discussed in note 34 suggests this possibility, although the damaged condition and the lack of certainty regarding its date precludes certainty. If the Prato fresco indeed dates to before the Magdalen Vita Panel I would suggest a still earlier source is probable. It seems unlikely that a provincial fresco would be the origin of this imagery. |

| ↑60 | Now located in the Accademia in Florence, the altarpiece was in the convent of Santissima Annunziata in Florence until the suppression of 1810, but it is evident that this was not its original provenance. For a summary of its provenance history, see Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 62-63. |

| ↑61 | In both, the angel holds the Host in their hands rather than with a cloth. |

| ↑62 | Hahn, Portrayed on the Heart, 41. She defines a topos as “a nonoriginal narrative unit.” |

| ↑63 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑64 | On temptations suffered by the Desert Fathers, especially demons, and their visual representation, see Gallant, “Into the Desert,” 101-119; Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum, 71-87. |

| ↑65 | Gallant, Illuminating the Vitae Patrum, 11, 92. |

| ↑66 | Susanna Elm, Virgins of God: The making of Asceticism in Late Antiquity (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1994), 256. |

| ↑67 | Jacobus, Golden Legend, I, 380. |

| ↑68 | Innocent III, Canon 21, Fourth Lateran Council, in Norman P. Tanner, ed., Decrees of the Ecumenical Councils: Volume One Nicaea I to Lateran V (London: Sheed & Ward; Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1990), 245. For more on the role of the Fourth Lateran Council in the reformulation of penitential theology, see Jansen, Making of the Magdalen, 199-200, 202-3. |

| ↑69 | Miri Rubin, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 85, see also 84. |

| ↑70 | C.H. Lawrence, The Friars: The Impact of the Early Mendicant Movement on Western Society (London and New York: Longman, 1994), 121. See also Jansen, Making of the Magdalen; Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 37ff. |

| ↑71 | Thomas of Celano reported that when Francis went to Pope Innocent III for approval of the first Rule in 1209, Innocent said, “Go with the Lord, brothers, and as the Lord will see fit to inspire you, preach penance to all.” Thomas of Celano, Life of Saint Francis (1228-1229), Book I, ch. XIII in Francis of Assisi: Early Documents, hereafter FA:ED, ed. by Regis Armstrong, Wayne Hellmann, and William Short, 3 vols (New York: New City Press, 1999-2001), I : The Saint (1999), 212. This is re-confirmed by Bonaventure in his Major Legend of Saint Francis, which superseded Celano’s Life of Saint Francis. Bonaventure states that Pope Innocent III “gave them [the Franciscans] a mandate to preach penance.” Bonaventure of Bagnoregio, The Major Legend of Saint Francis (1260-63), Ch. III, in FA:ED, II: The Founder, 548-549. |

| ↑72 | In 1969, Bologna identified a damaged and illegible inscription to the left of the Magdalen, which he believed to be the artist’s signature. Ferdinando Bologna, I pittori alla corte angioina di Napoli (Rome: U. Bozzi, 1969), II-36, Fig. 53; 112 n101. This inscription has been noted also by J. Krüger; although he transcribes it: (h)IC / FECIT / (pe)NITE(n)/TIA(m). Jürgen Krüger, S. Lorenzo Maggiore in Neapel: Eine Franziskanerkirche zwischen Ordensideal und Herrschaftsarchitektur. Studien und Materialien zur Baukunst der ersten Anjou-Zeit (Werl: Coelde, 1986), 89 n33. Wilkins was the first to consider this inscription in relation to penitential themes. Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 95. |

| ↑73 | The two Magdalen Vita Panels, the cycle in the Bargello, Florence, and the cycle in the Pipino Chapel, S. Pietro a Maiella, Naples. |

| ↑74 | Wilkins, “She Loved More Ardently,” 25-35. |