Thomas Brami • University of Wisconsin, Madison

Recommended citation: Thomas Brami, “Contaminations of Past and Present in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s I racconti di Canterbury,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 7 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/OYAR2408.

When the Inquisition tried and burned witches, the world was stationary rather than dynamic, thinly populated rather than crowded; there was not yet the sensation of dizzying physical movement and the amorphous masses were still to come. It was essentially a finite cosmos, not the infinite world of ours.

-Siegfried Kracauer[1]

Introduction

The above quote from Siegfried Kracauer typifies a common view of the Middle Ages that informed early film theories of the new medium’s capabilities. Like Walter Benjamin, Kracauer posited a fundamental shift in human perception under modernity: it was an experience marked by shock, distraction, and isolation in an age that had ushered forth hyperstimulation and a mode of scientific thinking that isolated objects and ideas in order to quantify them. As a product of modernity, film somewhat paradoxically had the radical potential to counter its shocks and its isolating effects by making us aware of the boundless spatial possibilities of modern reality. Films about the Middle Ages were thus doubly flawed for Kracauer: they did not utilize the medium’s potential for representing a boundless world, and they wrongly misrepresented the Middle Ages as open. While theorists such as Erwin Panofsky, Béla Baláz and André Bazin instead compared rather than contrasted the effect of film with that of medieval art, their assumptions are similarly informed by a view of rupture between the Middle Ages and the modern period, where the former world was experienced as spatially and temporally finite or unified.[2]

Periodization continues to underpin contemporary theory and film analysis. Despite his highly idiosyncratic output, the reception of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s work is a paradigmatic case. Because Pasolini seems to propose a counter-modern cinematic imagination, his work appears to respond to the often-made assumption that the cinematic apparatus (including its optics, forms, subjects, and ideological effects) is a product of modernity, descending from Renaissance perspectival tradition. Because Pasolini reaches back to pre-modern subject matter, and uses unconventional aesthetics that deviate from the norms developed within the classical Hollywood system, there has been a tendency to invest his films with an oppositional power that goes beyond the transgressive representations that his characters enact on screen – this is a power that supposedly, disrupts the ideological effects of the cinematic apparatus itself. According to the Marxist and Foucauldian paradigms that have been so influential in film theory, the fourteenth century is an age of social transition when the sexual, social, and national identities of the modern age had not yet been fixed in place by forces of dominant power. In this view, the individual’s lack of a subjectivizing identity paradoxically makes the Middle Ages well suited to discourse that could formulate the transgressive sexual act. Pasolini’s transgressive subject matter has its stylistic correlate in the use of medieval iconography, theatrical performances, and depth-flattening, painterly compositions, with both strategies finding an excessive hermeneutic encoding that bears the device, distancing passive spectatorial modes of perception.

As Giuliana Bruno makes clear in her own analysis of Pasolini’s writings on film, the director’s films are reconsidered alongside contemporary theory for good reason.[3] Pasolini’s semiology was rejected by his own contemporaries – by the likes of Christian Metz, Stephen Heath, and Umberto Eco – on the basis of a perceived naïve realism. But as Bruno claims, now that the drive to consider semiotics a scientific exercise has passed, it is possible to move beyond the “notorious question of reality” and to re-evaluate Pasolini’s work with attention to the multifaceted and complex nature of his thought.[4] It is in this spirit that we find scholars drawing from theoretical traditions that are based on historical binaries, such as Patrick Rumble’s analysis of Pasolini’s films alongside the Marx-inspired suture theorists, or Agnes Blandeau’s use of Foucault’s writings on biopolitics.[5] These authors’ pioneering work, and the translation of Pasolini’s wide-ranging writings into English, has demonstrated that Pasolini’s semiology was not one that collapsed the cinematic into the real in reverence of reality, but instead was a theory that saw the medium of film as a privileged site of social negotiation, an inscription of cultural production and theoretical discourse into praxis. Rather than providing an ontology of cinema, Pasolini proposed that the cinematic image was a meta-linguistic sign brought to consciousness in the practice of interpretation.[6] The radical heterogeneity of his films – their stylistic and thematic eclecticism – was a reflection of the relation between texts, ideas, ethics, experience and perception, and thus a challenge to rethink both the conventional dichotomies that underpin the political Left and Right, and the homogenizing cosmopolitan culture of consumer capitalism. It is this reconsideration of Pasolini’s semiology that has informed the increasingly common view of Pasolini as a precursor to post-structuralism, post-colonial studies, and cultural theory.[7]

It is also in the spirit of Pasolini’s ongoing reassessment that I situate the analysis that follows, but rather than turning to film theory or cultural studies as a frame of reference, this article asks how Pasolini’s thought might be brought into generative conversation with critical currents in medieval studies. A focus point for Pasolini’s treatment of history is the series of adaptations he made as part of the Trilogia della vita (Trilogy of Life) which includes a version of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. As I will explain below, Chaucer has been central to the reconsideration of the split between the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and this article demonstrates the ways that Pasolini’s adaptation anticipates these insights while raising important questions regarding temporality that occupy the field of medieval studies but are neglected in cultural studies more broadly.

In the first section, I explore Pasolini’s film theory in relation to Chaucer’s reception in medieval studies. In recent years, Chaucer’s poetry has often been used as a challenge to the assumption that the Renaissance marked a shift in Western consciousness. A number of scholars show how his heterogeneous poetic style responds to a complex social and even globally connected world, problematizing reductive accounts of the transition from a feudal to capitalist economy and its perceived effects on subjectivity. Decades before these interventions, Pasolini’s I racconti di Canterbury (1972) featured a “global” Middle Ages that allegorized the “international neocapitalism” of his own time, and Pasolini detected in Chaucer’s poetry an open structure that would influence his own “cinema of poetry” and his aesthetics of “contamination.” For Pasolini, contamination referred to a mix of codes and styles, but also a combination of sacred and profane forces that he believed comprised the cinematic apparatus itself and which rendered the spectator an active participant in the construction of his films’ meaning and impact.

The second section of this article takes Pasolini up on this interpretive challenge by considering I racconti’s political effects. In light of the conceptual challenges surrounding periodization, I “contaminate” Pasolini’s own theory by reading the film not as an allegory for the present, but as a non-linear historical representation that articulates discursive tensions between the medieval and modern that are operative in the periods in which both Pasolini and Chaucer lived. Both artists’ use of symbolic settings is particularly reflective of their engagement with “medieval” theological and “modern” economic ideas, and in the final paragraphs, I demonstrate how Pasolini guides our attention to these settings in order to negotiate tensions between economics, gender, class, and institutional power in The Merchant’s Tale.

Pasolini’s antagonism towards continuity devices makes it unlikely that he would have agreed with my analysis of his style. We cannot know definitively, as his writings are full of contradictions, recantations, revisions, and ironic allusions that elude unification. However, more than his use of any particular device or subject, it may be the persistence of this unsettling (or contaminating) voice that provides Pasolini’s films with an index of lasting critical power in a way that perhaps parallels the function of the Middle Ages in popular memory culture. Both have frequently occupied an antagonist position towards whatever aspect the present ascribes itself, and perhaps they are reflective of what Richard Burt has called the “philological uncanny:” a compulsion to recover the past by correcting its texts, and a continual return of that which has been repressed by linear, progressive historical models.[8] It is this impurity and recursivity that inspires the following analysis, designed to open Pasolini’s text to new insights while suggesting possibilities for critical theory at the intersection of different media, historical periods, and disciplines.

Pasolini’s Contaminations

Only since the Renaissance have people become aware of themselves as freestanding individuals – or so the story goes. A lasting assumption is that, before then, in the words of nineteenth-century historian Jacob Burckhardt: “man was conscious of himself only as the member of a race, people, party, family or corporation – only through some general category.”[9] Medieval literature has therefore seemed inhospitable to the study of the relations between individual subjectivity and social power. As D.W. Robertson put it in A Preface to Chaucer:

The medieval world was innocent of our profound concern for tension…We project dynamic polarities on history as class struggles, balances of power, or as conflicts between economic realities and traditional ideals…But the medieval world with its quiet hierarchies knew nothing of these things.[10]

However, contemporary studies of Chaucer complicate the view that the Renaissance was an age in which individual subjectivity was formed. Where Chaucer was once admired as a forebearer to this moment because he reflected the timeless “human condition” that was apparent in the great works of antiquity, over the last few decades, scholars such as Paul Strohm, David Wallace, Lee Patterson, Peggy Knapp and David Aers have created a rich picture of the social world in which Chaucer lived, demonstrating how his poetry engages with the complex social, political, and ideological conflicts of his time.[11]

Medievalists have also drawn upon Chaucer to address the assumptions that underpin the theoretical frames we use for studying the Middle Ages directly. For example, in Negotiating the Past, Lee Patterson set in motion New Historicism’s study of medieval literature with a theoretical lens derived from Foucault and cultural anthropology partly as a way to eschew Marxist causality.[12] However, while Marxist perspectives often place the medieval era outside of the master narrative of capitalist accumulation and class struggle that defines the modern era, the focus on power discourses and social divisions also neglects the complicated way that economic and political processes worked in the Middle Ages and how people reacted to them. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, medievalists and early modernists often showed how contemporary theoretical paradigms reinstate the Middle Ages as a homogenous and mythical field against which the Renaissance and the troubling idea of “modernity” can be defined, while a more recent trend in medieval studies provides an important corrective to both Marxist and Foucauldian assumptions by attending to the Middle Ages’ global connections alongside particular voices and poetics.[13] For example, the collection of essays Money, Commerce, and Economics in Late Medieval English Literature (which contains three essays on Chaucer) offers a “post-Historicist turn towards history” that considers economic processes alongside literary texts; The Global Middle Ages includes essays on economic, political, social, and cultural processes, eschewing periodization “to focus on what people actually did, and on how and why they did it;” while Marion Turner’s recent biography of Chaucer convincingly demonstrates the way that Chaucer’s experiences in a period of great economic, political, and social flux shaped his poetic imagination.[14]

The latter study is particularly salient in its demonstration of the Middle Ages’ global connections and the way that Chaucer’s poetry constitutes a complex subjectivity. Turner tracks the way that Chaucer moved through multilingual and multicultural spaces such as Vintry Ward (an immigrant neighborhood that lay along the Thames); occupations that connected him to a cosmopolitan court life (from his position inside the great household of Elizabeth de Burgh to his occupations as diplomat, forester, and clerk); and a peripheral kingdom (travelling widely within England and abroad with a direct involvement within global networks of power and culture). As Chaucer moved further from the center of London and court-life, Turner demonstrates how his poetry became more global in its outlook, reflecting England’s interactions with the world in a way that destabilizes hierarchical ideas and notions of center-periphery. For example, Chaucer’s trips to Italy are particularly reflective of England’s complicated entanglement in global trading systems and European politics, and these visits also had a profound influence on Chaucer’s poetics. Here, Chaucer learned to resist a teleological view of history and imperial power, embracing a sense of contingency that he would express in heterogeneous genres and voices.[15]

Almost fifty years before these interventions, Pasolini launched a political project that also involved casting Chaucer within a “global” Middle Ages, while capitalizing upon his heterogeneous poetics to develop his own theory of film. Like much of his work the film is an allegory for his own time, which he thought was entering into a new phase of “international neocapitalism:”

Capitalism is today the front line of a great internal revolution: it is revolutionarily evolving into neocapitalism. Faced with this revolutionary, progressive and unifying neocapitalism, there is an unheard of feeling, an unprecedented feeling of unity in the world. Why all of this? Because neocapitalism coincides with the complete world’s industrialization, and with the technological application of the science. It is a product of human history: of all men, not just of this or that people. In fact, nationalisms tend, in the near future, to be levelled by this naturally international neocapitalism. So the unity of the world (now barely sensible) will be a real unity of culture, social forms, goods and consumption.[16]

I racconti di Canterbury’s opening sets up the film’s depiction of a world that is unified by international neocapitalism and its cultural and social forms. In Pasolini’s version of The General Prologue, the director does away with the descriptive frame that associates characters with social hierarchies, and the space is not marked geographically either but instead is defined by institutional forces that exude their power from afar. For example, a sense of place is expressed in the Wife of Bath and the Pardoner’s monologues, but rather than announcing where they are from, they announce to their marketplace audience their own (and the market’s) connection to the larger, economic marketplace of the medieval world: Alisoun is better at weaving than “those bitches from Ghent and Ypres” and has travelled to the cosmopolitan centers of the known world (Rome, Cologne, Constantinople); the Pardoner peddles wares that come directly from Rome. Their monologues fade into the raucous ambiance of the marketplace, and depending on whether you listen to the Italian version or the dubbed English, we could be in England or Italy, or even in the world evoked by the Flemish masters that informs the scene’s mise-en-scène.

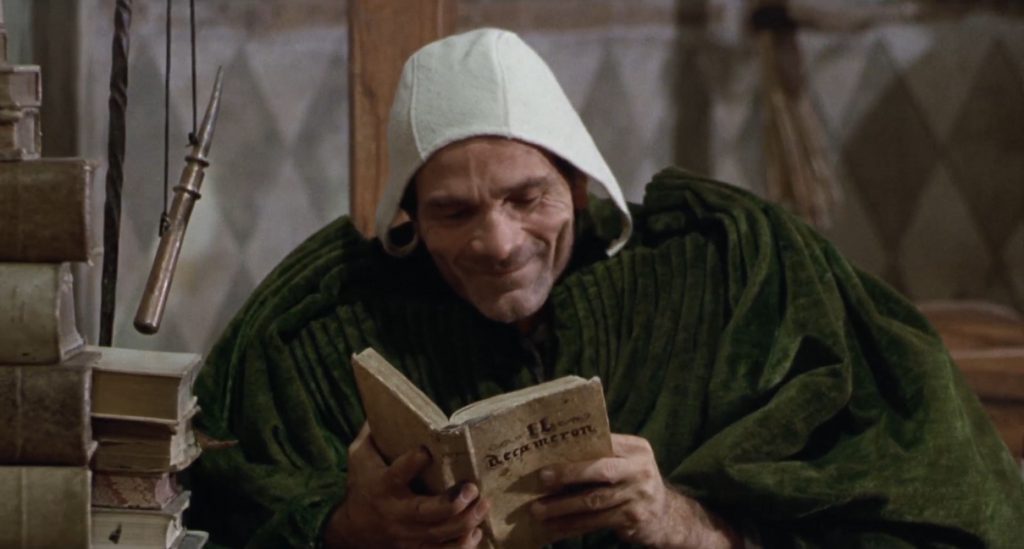

The Canterbury Tales provided Pasolini with more than just an allegory. His adoption of Chaucer’s poetic technique is reflective of the medievalism that informed his style and film theory more generally. Much has been made of the influence of fourteenth-century art on Pasolini’s visual style, but his allusions to Chaucer’s metafictional devices might also be regarded as a key moment in the development of his “cinema of poetry.”[17] Crucial to the distinction Pasolini makes between “prosaic” and “poetic” cinema is a device he called the “free indirect subjective” that permits the author to maintain their own voice while entering their characters’ world. By this, Pasolini refers to the way that a director can express their point of view in the world of a narrative film, but in I racconti, Pasolini does this literally by playing the role of Chaucer. While the “free indirect subjective” was based on literary theories of “free indirect discourse” and conceived earlier in relation to the techniques employed by “modernist” filmmakers such as Antonioni, Bertolucci, and Godard, he engaged with this idea in a more lasting way alongside his reading of Dante, whose persona he eventually assumed in the long gestating and posthumously published Divine Mimesis.[18] In I racconti, Pasolini displays an authorial elusiveness that references Chaucer’s own self-referential technique (apparent for example, in the Man of Law’s Introduction, Prologue and Tale), just as his decision to play Giotto’s best pupil in The Decameron suggests a link between the construction of a fresco and the film itself.[19] In Pasolini’s later works, the medievalism of his poetics that is always implicit in his theory and praxis becomes more explicit through his own identification with figures that he thought approximated his cinema of poetry. (Fig. 1.)

Fig. 1. Pasolini as Chaucer, reading The Decameron.

This technique is central to Pasolini’s aesthetics as well as his own self-fashioning. But if adopting medieval figures’ personas allowed him to assert a particular agency over the text, according to the theorist’s beliefs regarding the function and limits of authorial intervention within a cinema of poetry there is no unity between Pasolini as auteur, narrator, or the character Chaucer. As he put it in “The Cinema of Poetry:”

This implies, theoretically at least, that the ‘free indirect subjective’ in cinema is endowed with a very flexible stylistic possibility; that it also liberates the expressive possibilities stifled by traditional narrative conventions, by a sort of return to their origins, which extends even to rediscovering in the technical means of cinema their original oneiric, barbaric, irregular, aggressive, visionary qualities. In short, it is the ‘free indirect subjective’ which establishes the possible tradition of a ‘technical language of poetry’ in cinema.[20]

The cinematic sign has a double aspect: it enables the authorial voice at the same time as it frees images from their mimetic functions to become “totally and freely expressive” as transmissions of “their origins.” For Pasolini, these origins were to be found in reality itself, which he conceived by using semiological language. The cinematic signifier was comprised of imsigns: precultural codes found in “gestures, environment, dreams, memory.” It is this contradictory logic that is at the heart of Pasolini’s theory of contamination: at once, cinema was enabled by forces of modernity and technology, but its language was one that was representative of “untamed thought,” or primitive and pre-linguistic experience that he associated with the “sacred.”[21]

Pasolini’s beliefs about the sacred are complex, and I expand upon this concept in the next section. But the question of agency that Pasolini was developing by associating himself with medieval artists during the making of the Trilogia was often expressed in religious terms and conceived alongside an identification with (and unrealized film about) Saint Paul. In 1969, he told the interviewer Jean Duflot “I have been discovering, slowly as I study the mystics, that the other face of mysticism is precisely ‘to do,’ ‘to act.’…”[22] In 1971, Pasolini’s last book of poetry Trasumanar e organizzar (Transhumanize and Organize) took its title from Dante to express these opposites. “Transhumanize” was Dante’s term for the impossibility of describing mystic discipline in the Paradiso, and “organize” meant to pursue action and community rather than solitude and contemplation. Pasolini’s discourse of the sacred parallels his writings on the cinema of poetry, where returning language to its origins is to practice a sublime contemplative discipline as well as to produce action within communities. As he put it in “The Unpopular Cinema,” the spectator is “merely another author” who “codifies the uncodifiable act performed by the author,” and in “The Written Language of Reality,” Pasolini said that “the first language of men is their actions. The written-spoken language is nothing more than an integration and a means of such action.”[23] Spectators, as well as authors, reconstruct the “written” manifestation of human action as they do in their dreams and memories.

But if Pasolini’s semiology often leads critics to interpret his discourse of the sacred in metaphorical terms, there is much evidence to suggest that Pasolini believed that the spectator could actually experience a trace of the numinous through cinema. In his screenplay on the unrealized Saint Paul project, Pasolini writes that “the poetic idea – which ought to become at the same time the conducting thread of the film – and also its novelty – consists of transposing the entire affair of Saint Paul to our time.”[24] These transpositions were to be expressed through analogies between the past and present as they are in the Trilogia, but they are also characterized in this case by a fidelity to Saint Paul’s words as they appear in the biblical text.[25] For Pasolini, the poet, like the prophetic figure, could sacralize the Word and make it a vehicle for the sacred just as cinema could return language to its “visionary” origins. As Noa Steimatsky argues, Pasolini’s theory of cinema might thus be considered “a theology of the cinematic image:”

The cinematographic impression can be seen to bind, then, Pasolini’s realism with a reverential perception. Pasolini’s archaistic imagination aspires to a primal sense of the cinematic image as reality’s direct emanation – one that carries the evidentiary force of an imprint but also the magical resonance of a temporal bridge to the past, as to an altered state: a simultaneity of different temporalities, different orders of being.[26]

Steimatsky demonstrates the way that Pasolini draws from the “magical resonance” of the devotional image and particularly the acheiropoietic icon. The icon was believed to have received the sacral image by direct physical impression, heightening the indexical claim between image and referent while endowing the copy with the miraculous power of the image in its moment of contact. Similarly, in his location scouting documentaries, Pasolini expresses a belief in the immanent power of the landscape, and sees the mythic traces of an archaic past that left their mark in particular environmental features, ruins, and the inhabitants of the land.

Yet, Pasolini was ambivalent about how one might harness this power. In a revealing essay, David Ward shows how Pasolini’s key terms such as “cinema of poetry,” “cinema of prose,” “film,” and “cinema” are ascribed different functions and privileged at different times throughout Heretical Empiricism: the collection of his writings on film semiotics.[27] Beginning with his 1967 essay “Observations on the Sequence Shot” – in part, because he realized that Andy Warhol used a continuous long take that was simply boring rather than revealing – Pasolini began to oscillate between an appreciation of more conventional narrative techniques that he associated with the term “film” and the transformative functions he ascribes to the “cinema of poetry,” expressed simply as “cinema.” In this essay, Pasolini imagines a spectator surrounded by multiple angles of the Kennedy assassination. In such a situation, Pasolini argues “this multiplication of ‘presents’ in reality abolishes the present; it renders it useless, each of those presents postulating the relativity of the other, its unreliability, its lack of precision, its ambiguity.”[28] Now, rather than privileging the spectator’s ability to reconstruct the archaic past in the present, Pasolini argues that cinema needs a narrator figure, a “clever analytical mind,” that “transforms the present into the past.”[29] Ward suggests that Pasolini’s vacillations are connected to a broader instability in Pasolini’s writings that is characterized by shifting subject positions occupied by different narrative voices: “at times, attracted by the potential for semiosis inherent in signs, the voice we hear is that of the poet; at other times, aware of the necessity to know and describe the world, the voice belongs to the narrator figure of genial analytic mind.”[30] Indeed, the crux of the issue is as Ward suggests the question of how we come to know the world through cinema, but it is also a question of agency, film style, temporality, and political engagement.

Pasolini’s identification with Chaucer amounts to a similarly unstable performance that explores these questions. Or rather, it is an exploration of metanarrative, where shifting subject positions articulate and constitute the instability within his own theorizing and self-fashioning. Pasolini thought that Chaucer’s own work was marked by a dichotomy where “on the one hand, there is the epic aspect with the vulgar and vital heroes of the Middle Ages who were full of life; on the other, the essentially bourgeois phenomena of irony and self-irony which are the sign of a guilty conscience.”[31] This dichotomy is reflected in I racconti di Canterbury, where on the one hand, Pasolini removes Chaucer’s frame narrative and simply lets the pilgrims perform, and on the other, he undermines the voice of Chaucer/Pasolini at key moments. Indeed, commentators often focus on characters from different social strata that subvert Chaucer/Pasolini’s authorial voice. For example, Agnes Blandeau sees his entrance into the marketplace and comic stumble into the Cook as a moment that undermines Chaucer’s class-based pretensions, and conversely, Kathryn L. Lynch argues that The Merchant’s Tale functions as “a kind of allegory of authorial tyranny” where the tyrant January stands in for the author himself.[32]

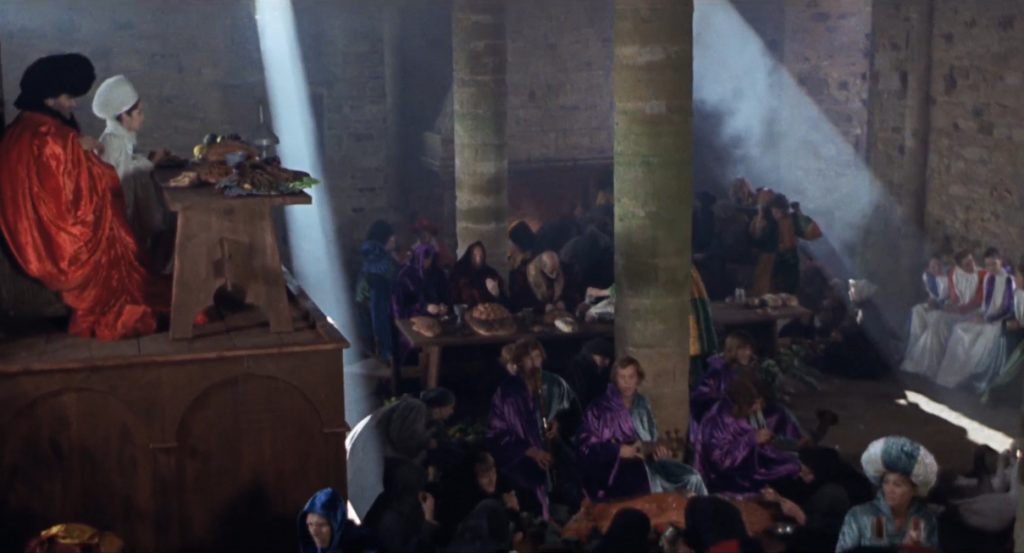

These are insightful readings; however, it is important to point out that in both of these cases, the final word is with a character that represents the sacred or the natural world. It is the power of the gods that ultimately shapes January’s perception, and it is not the Cook who makes Chaucer/Pasolini a laughingstock, but Chaucer/Pasolini’s horse that bumps the poet into the Cook in the first place. In the marketplace, agency is dispersed and fragmented, with animals even assuming a role in driving the narrative. They participate in the general economy of bodily exchange that characterizes this world: the Miller wins a goat for his wrestling, but he treats the goat like a lover by holding it to his breast and kissing it (Fig. 2); flocks of geese, cows, dogs, and herds of goats occupy a central place in the frame as they wander about the marketplace with its peoples; and Chaucer/Pasolini’s speech, ironically, comes straight from the horse’s mouth. If for Pasolini the films of the Trilogia were “an experiment with the ontology of narration, an attempt to engage with the process of rendering a film filmic,” the determining factor in this process is not the voice of the rational poet, but the “irrational” forces of reality.[33]

Fig. 2. The Miller wins a goat.

The expressive potential of reality remains a constant theme throughout Pasolini’s writings, and his rethinking of agency through cinema as a continuum of language, culture, and biology underpins his persistent beliefs about political commitment in the age of neocapitalism. As the filmic signifier did not contain traces of class or national linguistic identity, cinema was an appropriate medium through which he could adapt the original texts of the Trilogia in order to displace nationalist cultural paradigms complicit in the installation of the international order.[34] Similarly, although the three films of the Trilogia were received as a retreat from the more incisive treatment of class so evident in earlier works such as Mama Roma (1962) and Teorema (1968), in these later films, Pasolini continues to seek a “reality” that could provide revolutionary energy in the urban peripheries at the margins of Europe and in the colonized world.[35] Pasolini travelled to Nepal, Africa, and the Middle East to film Il fiore delle mille e una notte (Arabian Nights, 1974), and for The Decameron, he changed the location from Florence to Naples in an attempt to allegorize the detrimental effects on the south of Italy that he saw emerging from the economic miracle of the 1950s.[36]

The “oneiric” quality of language upon which the cinema was precedented was also associated with oral speech, and the film’s sound design is important for its political effects as well. In the essay “Quips about Cinema,” Pasolini compared the turn from an oral to a written culture with the effects produced by the mirror. Writing “revealed to man what his oral language is, first of all. Certainly, this was the first movement forward in the new, human cultural consciousness.”[37] Pasolini thought cinema could perform a similar role, and perhaps he considered Chaucer’s work reflective of the potential for the written to illuminate an oral culture that constitutes subjectivity (this quality of Chaucer’s poetics has in fact since been described by Marshall Leicester).[38] Indeed, “chatter” was the “gift” and structure of Chaucer’s work for Pasolini, and particular but cacophonous local dialects were as important for the Trilogia’s political work as the transmission of the “absolute” language of reality.[39] For Pasolini language is a tool of hegemonic culture, and the standardization of Italian since unification was symptomatic of Italy’s acquiescence to global bourgeoisie technocracy. Thus, his decision to film The Decameron in Naples was also motivated by his desire to replace the Tuscan dialect (that Boccaccio helped make the national standard) with a Neapolitan dialect that he saw as reflective of an uncivilized underclass.[40] I racconti di Canterbury was also dubbed into both Neapolitan and English, which Louis D’Arcens argues is a “deliberate strategy of split-second delay” that produces an alienating effect in the viewer.[41] For D’Arcens, the English language version presents a cacophony of local dialects that can be interpreted as a challenge to the proto-bourgeois culture of which Pasolini believed Chaucer was a participant. However, she argues that the temporal slippage experienced by the viewer of the Italian version suggests “that the proto-bourgeois English text is not fully contained by proletarian Neapolitan.”[42] Pasolini was perhaps aware of this tension: I racconti was filmed in England in part because he attributed Chaucer’s pessimism to the dark Northern European climate – a pessimism which Pasolini himself felt in regards to the very possibility of using the folk Middle Ages as a precedent for popular resistance, even as he represented it.[43]

To be sure, the Trilogia does reflect an ideological shift away from the overt politics of his earlier films, a position perhaps asserted by Chaucer/Pasolini’s provocative closing statement to I racconti: “Here end the Canterbury Tales, told only for the pleasure of telling them.” Far from being apolitical, however, it is pleasure that forms the basis of the Trilogia’s critique of religious hypocrisy, the spiritual bankruptcy of the bourgeois, and capitalist oppression. With different emphasis, each film expresses sexuality in the face of what Pasolini saw as a world rising to a level of unreality, epitomized in its denial of the body. While editing Il fiore delle mille e una notte, Pasolini explained his representations of sexuality in the films of the Trilogia in response to critics that held him responsible for an explosion of low-budget pornographic versions. He wrote that: “the bourgeoisie, creators of a new type of civilization, could not help but arrive at the de-realization of the body. They have been successful, indeed, and they have made a mask.”[44] If the body had become a sign whose referent was merely consumer products, Pasolini draws attention to bodily functions – shitting, fucking, puking – to reassert the body’s materiality. He also believed that reality survived in the Neapolitan subproletariat and Third World subject, who had not yet adopted bourgeois values. It is this survival that Pasolini celebrates in the ebullient expressions of sexuality in The Decameron and Il fiore delle mille e una notte. On the other hand, in I racconti di Canterbury, Pasolini’s most prominent additions to his source material reflect the intertwining of political, economic, and sexual oppression. Towards the beginning of the film, for example, a sodomite is burned alive at the stake. But this is not because of his crime, but because he could not afford to buy off the power of the church like his fellow parishioners.

Unsurprisingly, for most critics Pasolini’s explicit and often brutal carnality distorts the original, but as I suggest above, the film anticipates certain trends in Chaucerian criticism. For Kathleen Forni, Pasolini’s film reflects what Carolyn Dinshaw has coined Chaucer’s “sexual poetics;” and it is also “the first to approach the work in a Bakhtinian spirit, emphasizing the carnivalesque spirit of Chaucer’s poem and the first to explore and exploit the ‘queer’ subtext of Chaucer’s poetics.”[45] I would argue that in these examples what Pasolini also anticipates is a more general political impulse that is apparent in medievalists’ critical re-evaluation of Chaucer in light of a blurred bright line between the Renaissance and the Middle Ages as well. However, the project of the “global Middle Ages” is not without its own conceptual challenges. It is to these issues that I now turn.

Contaminating Pasolini

I racconti di Canterbury’s political effects are the subject of much debate. This is not surprising, as Pasolini invites a multiplicity of readings by fashioning an ambiguous persona that haunts the film and by offering contradictory public statements outside of it. While the film ends with Chaucer/Pasolini’s comment that the film was “told only for the pleasure of telling them,” later, he was to vigorously defend the films of the Trilogia as his most ideological, and eventually, he would recant them altogether.[46] To be sure, the constant undoing of subject positions both inside and outside of the film – including his recantation – can easily be interpreted as part of the self-conscious exploration of metanarrative that characterizes the Trilogia and his poetics more generally. However, whatever artistic and political effects Pasolini might have intended, these were swiftly neutralized by the film’s commercial success. By 1975, I racconti di Canterbury had spawned dozens of softcore pornographic imitations, and thus even Pasolini’s most explicit and “transgressive” depictions of sexuality became integrated into a global mainstream consumer culture.[47] It is indeed an irony that Pasolini’s theory depends on the double articulation of the cinematic signifier as at once intentional and primordial, and that it is the sex drive that led to the displacement of his authorial intentions as the film circulated in popular culture. In a fitting but troubling paradox, Pasolini/Chaucer and “reality” had become agents of the very forces he believed they could unsettle.

The fate of I racconti di Canterbury reminds us of the power that critical artistic and academic interventions can exert on the popular sphere. The cinematic uses of the past have long been the concern of film scholars, and now, medievalists are grounding their own scholarship in similar concerns about the resonances of the past in the present, but with a greater awareness of positionality derived from postcolonial studies.[48] Thus, the Global Middle Ages Project (G-MAP)– an interdisciplinary collaboration of scholars working across media – features an introductory essay that situates the project as an intervention in both politics and academia by opening with a reference to the “Global War on Terror’s” medievalism and the calcification of humanities departments along disciplinary lines.[49] But while the project’s global focus seeks to decenter the then near-exclusive focus on Europe and devaluation of medieval studies by administrative bodies, the authors demonstrate why periodization is also necessary to distinguish the ways in which globalism in the Middle Ages is different from modern processes of globalization. Not only does such a historical collapse mask the particular character and political urgencies of both the past and present, but as Kathleen Davis and Nadia Altschcul argue elsewhere, it can corroborate the narrative logic of western global dominance.[50] Europe’s growth in global power involved the construction of the medieval as a period characterized by the sacred and irrational, which facilitated the identification of colonial subjects themselves as irrational and superstitious. As Davis argues, medievalists situated within the corporate structures of the university are uniquely positioned to deliver “precisely what is necessary for globalization – particularly its economic forms – to have a legitimizing past.”[51]

Pasolini’s film is unlikely to ever be taken as historical fact, but as a public intellectual who continues to exert an enormous influence on the humanities in general and with the release of Criterion Collection’s Trilogy of Life in 2012, his medievalism is one of the most powerful in popular culture. While severe restrictions limited the circulation of I racconti in the years following its release, viewers can now watch high quality restorations of the films of the Trilogia alongside a wealth of supplementary critical material on the Criterion website and DVDs, and Pasolini’s work continues to find legitimation by and within academic discourse that seeks to explain his films’ political effects by showing how his ideas resemble this or that theory. Indeed, Pasolini’s own periodization is characteristically complex and contradictory, as his statements oscillate between a straightforward nostalgia for the premodern and a more flexible conception of temporality that suggests a collapse of the past into the present and vice versa. However, despite Pasolini’s attempts to turn the sacred and irrational characteristics of the premodern into a virtue, he nonetheless reinstates and naturalizes a binary that has legitimized systems of rule that bore and continue to bear concrete effects upon the very minoritarian groups he wishes to liberate. Attempting to resolve or rationalize the contradictions in Pasolini’s thought by turning to theoretical paradigms that also depend on binaries between the medieval and modern can further buttress the very logic of the systems of power that they seek to unravel.

At the same time, it is perhaps the pervasiveness of Pasolini’s paradoxical logic that might provide I racconti di Canterbury with a lasting critical force. Pasolini’s film provides a non-linear model of temporality that could be read – and more importantly, positioned – as an illuminating historical work. Davis responds to the conceptual problems involved with the “global turn” with a similar kind of solution in a conversation with Micheal Puett:

The challenge, then, is to think the idea of “the medieval globe” in a way that, as you suggest, resuscitates “medieval” as a theoretical term divorced from teleology and the spectre of an inevitable modernity. Such a “medieval” might bring to visibility multiple, coexisting conceptions of temporality that altogether defy attempts to plot them on a linear trajectory.[52]

A number of medievalists and early modernists follow this line of thought by arguing that it is necessary to consider the “medieval” and “modern” not as terms that denote periods, but as plural concepts that can exist in multiple times and places.[53] This is indeed what Pasolini’s film achieves, however I would like to distance my approach from those who champion the cinematic medium itself as particularly suited for reconceiving of temporality. This claim is most often made by drawing from Gilles Deleuze’s conception of the “time image,” paradigmatically, through “crystal images” which represent movements of past and present that show us how we operate and inhabit time.[54] Such an approach ironically reinstates a periodizing historical framework (the time image is associated with post-war films) that is based on a kind of circular reasoning, inherited from Henri Bergson, where the example becomes proof of the theory: cinema both misconceives of movement and time but is also used as a metaphor that models “modern” epistemology.[55] While the “modern” and “medieval” are concepts that coexist in the storyworld of Pasolini’s allegorical text, the film is not indexed as scholarship, making his analogies appear sloppy, and his “transgressive” representations of carnality a more likely affordance of gratuitous pleasure. To bring visibility to the historical and political work that Pasolini’s medievalism can do would necessarily involve abandoning the idea that his subject matter and stylistic technique is inherently subversive, and instead, emphasizing Pasolini’s contradictory temporal logic as well as the kinds of historical truths to which it alludes.

For example, Pasolini’s contradictory vision of the sacred and profane forces of cinema offers an analogy with Chaucer’s practice that is suggestive of the poet’s position within the long durée that saw the transition to a modern economy. Scholars have recently demonstrated how in Chaucer’s time, seemingly contradictory ideologies and modes of exchange were operative. For example, Anne Schuurman troubles the traditional reading of debt in Chaucer, where the comic punchlines in the Friar-Summoner sequence appear to depend on the incommensurability of economics and theology as separate fields of inquiry.[56] Clerical corruption is often equated with corrupt friars, summoners, monks and pardoners who attempt to quantify the non-quantifiable — that is, the spiritual debt or “rente” owed to God. However, Schurmann argues that a challenge to this common-sense reading arrives in the coda to The Summoner’s Tale, where the squire successfully poses a solution to the problem of division. Following Giorgio Agamben and Walter Benjamin, Schuurman concludes that capitalism is “essentially a religious phenomenon,” and she demonstrates how Chaucer does not oppose economics to theology but instead exploits the multivalence of debt, in particular its double mathematical and theological meanings.[57]

Comparably, Pasolini’s own adaptation of the Summoner’s Tale and Prologue also posits a connection between economics and religious corruption, while simultaneously emphasizing the corporeality of the body that is so important to his belief in the cinematic image’s transmission of the sacred. The scene is fixated on anality: Satan’s henchmen mutilate sinners’ nether regions with sledgehammers, demons violently rape the sinners with pitchforks, and Satan himself excretes corrupt friars in an explosive discharge. At the time, the scene became a focus point for the film’s negative reception, and it has since been defended as a transgressive challenge to religious hypocrisy.[58] However, more recent attention to Pasolini’s religious beliefs reveals a complicated attitude that is analogous with Chaucer’s in the way that the artist engages with competing ideologies that circulated in the historical context in which he lived. As Stefania Benini argues, Pasolini’s conception of “sacred flesh” is above all animated by a feeling or “sense of the sacred” that involved an intense, subjective adherence to ideas gleaned from both religious tradition and the contradictions of post-historical modernity.[59]

While The Summoner’s Tale punctuates the film with an emphasis on the relationship between economic and sexual oppression, in The Merchant’s Tale, Pasolini, like Chaucer, attaches symbolic weight to elements of the setting, emphasizing the tension between the sacred and the profane. Story settings were extremely important for both artists, and two particular symbolic spaces form the backdrop for The Merchant’s Tale: the palace and the garden. These settings can be read as representations of the contaminating forces that make up Pasolini’s theory of the apparatus itself: below I interpret the palace as a profane, institutional locus of power, and the garden as a symbol for sacred, immanent power. Pasolini’s discourse of the sacred is an extensive one that involves the archaic, the flesh, the ruinous, the landscape, and a reverential perception that is bound to the photographic capabilities of the cinematographic medium. Added to this list might also be Pasolini’s attitude towards nature. For example, Monica Seger’s ecocritical readings of Pasolini’s films focus on “interstitial landscapes” that explore the transition from agrarian to cosmopolitan life in a way that parallels his assertion of the “interstitial person”: both sacred and damned in the face of commodification and industrialization.[60] As we shall see, the garden in The Merchant’s Tale accords with Mathew Gandy’s description of Pasolini’s representations of an “uncompromisingly essentialist reading of nature as a physical embrace around the everyday world of bourgeois reality.”[61] Indeed, the garden is a space that is essentializing in the way nature and culture are opposed, and it is also classically gendered. Yet, just as Pasolini’s earlier explorations of the Roman borgate in Accattone (1961) and Mama Roma (1962) were fixated on the visual overlap between open land and urban structure and development, so too does the garden interpenetrate with the figure of the palace. In The Merchant’s Tale, the palace not only recalls Pasolini’s use of institutional settings as the space of tyrants (for example, Pelias as usurper of the throne in Medea (1969) or the four fascist libertines in their castle in Salò (1975)), but it also brings to mind his interrogation of the production of knowledge. As is often noted, Pasolini’s theory was preoccupied with the Foucauldian question of the relation of power to knowledge, and in his theoretical writings he used the architectural metaphor of the palazzo (the “palace”) to stand for the far-reaching notion of an institution as well as the network of transactions created by and within dominant discourse.[62]

In Chaucer’s poetry, palaces and gardens similarly function as nexus points that negotiate the tensions between economics, gender, class, and institutional power. For Chaucer, the palace – and its extension, the tower – were symbols of imposing mystique and sovereignty, associated with the structures of church and state. However, they also symbolized economic change.[63] The Tower of London was a place that occupied Chaucer as clerk of the works. It was the place where money and weapons were made, and thus a site that facilitated major changes in English life that came with the development of guns and gold coins. Chaucer’s gardens, too, had political and economic resonances in addition to mythical associations. They were constituted by their connection with buildings; spaces of female segregation but also where women could express a creative preserve; gardens were associated with eavesdropping and surveillance; and following in the tradition of Guillaume de Machaut and his heirs, they were, as Turner puts it, “the space of courtly subjectivity and subjection, where the individual is constrained yet also constituted.”[64] For Chaucer, the garden not only had long standing biblical and mythical associations, but it also constituted a displacement of the interior world of courtly leisure: a characteristic example of his rejection of center-periphery divides. These connotations emerge from Chaucer’s rich symbolic textuality, heterogeneous expression of genres, forms, and intertextual allusions. While such attributes abound in Pasolini’s work, the director also uses norms developed within Hollywood’s system of continuity-editing to guide the viewer’s attention to salient areas of the frame in order to communicate an intended meaning. In The Merchant’s Tale, Pasolini uses camera movement, framing, editing, elements of mise-en-scène, and sound in concert to align characters drawn from different social classes with or against symbolic settings. Out of these particular relationships emerges a picture of interpenetrating theological and economic modes, and a reflection of the sacred and profane powers that comprise Pasolini’s theory of contamination.

Fig. 3. First exterior shot of the palace.

When Pasolini gives us the first exterior shot of the palace he immediately aligns January with its power (Fig. 3). The scene begins with a shot of a tower, which is followed by a long, slow vertical tilt and tracking shot that shows off the height and majesty of his palace as it moves down its elaborate façade to rest on an empty arched door at the center of the frame. The arched door is flanked by three guards who wield absurdly oversized axes. The guards are arranged along the z-axis, diminishing slightly in size from the left side of the foreground to the immediate space in front of the archway in the midground, leading the eye to this centered architectural zone. Their costumes’ yellow and ruffled texture match the building’s off-yellow checkered bricks, helping to lead the eye, but also suggesting that the guards are an extension of architectural power. The figures are crowded into the space of the foreground and pressed up against the palace which forms a stage-like backdrop. This eliminates the depth of the image, so that January emerges in the archway as if from the very setting itself. He is dressed in a slightly darker yellow costume that both connects him to the building but helps offset him from it as the center of focus. The camera cuts closer to January as he scans the marketplace for a bride (Figs. 4 and 5). Shots that frame January in his archway are followed by his point of view, suggesting it is not only January who gazes hungrily at the lower classes before him, but the structure of institutional power in which he is centered. The market is a center of economics, but it rests at the base of an institution that has the power to consume all that’s within it, even its people.

Fig. 4. January scans the marketplace for a bride.

Fig. 5. The marketplace that January scans for a bride.

These strategies for aligning January with the architecture of the palace – framing within architectural zones, centering in the frame, the arrangements of the mise-en-scène, voice, and point of view shots – continue throughout the tale. At the feast, January towers above the room on a giant feasting table (Fig. 6). In the bedroom scene, his loose white cloak merges with the sheets of the bed and engulfs the naked May within it (Fig. 7). But aligning January with the institutional power exuded by his palatial architecture sets up opportunities for transgression. These are realized outside of the palace, where Damian pleasures himself outside the window as January serenades May, but there are also instances of subversion inside the palace; Damian and May exchange letters and lustful glances under January’s nose. Of course, the tale’s famous act of transgression occurs in the garden, but it is not only the humans in this space that are responsible for undercutting January’s power. Unlike the marketplace, which functions as an extension of the palace’s (and cities like Rome’s) economic power, the garden is a place that occupies a liminal space between the institutional, human, and divine. As such, January’s power within this space is contaminated by divine forces, and the architecture of the palace itself is contaminated by the garden.

Fig. 6. January aligned with the architecture of the palace.

Fig. 7. January aligned with the architecture of the palace.

The first shot of the garden contrasts with the first exterior shot of the palace. Rather than tilting, the shot pans almost 360 degrees, emphasizing the expansive power of the divine, ecological world as it pervades the human, rather than human attempts to reach the heavens. The noise of court and commerce in preceding scenes is strikingly absent; only the birds are chirping as a faun plays a lute. Pluto and Proserpina stroll through the orderly green trees, but rather than speaking, it is January who narrates, bragging to May about the garden’s beauty, reaffirming his ownership of the space by telling her it is only he who has the key that will provide access. But as the narration continues, the camera undercuts his claim: a cut to an extreme long shot shows January and May at the cusp of its entrance; at the left is the palace, but on the right is the garden which spills over from its boundaries and engulfs the palace in its green leaves (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. The garden consumes the palace.

In this scene, January’s costume – a striking red cloak – makes him stand out and draws the eye. At the palace, costume and framing worked together to position January as a force from which power exudes. Here, the power of the environment bears upon him. In his red clashing cloak, he is squeezed between the green leaves and vines that spill out from the garden and over the walls of his palace (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. The power of the environment bears upon January.

As he leaves the boundaries separating the garden from the palace, he swaps his red coat for a white one that matches May’s. But now, he is framed in an extreme long shot that dwarfs the humans within the green garden that engulfs them and sprawls across their architecture (Fig. 10).

Fig 10. The garden encloses the feminine figure.

This image is a reformulation of a classic “hortus conclusus” trope, where the garden encloses the feminine figure, foreshadowing the reversal of power dynamics at play. This reversal is emphasized by the shots that establish this image as Pluto and Proserpina’s point of view. (Fig. 11) They laugh playfully at January, countering his earlier lustful gaze at May in the marketplace.

Fig 11. Reversal of the gaze.

The final two transitions from the garden to the palace and back again emphasize January’s undoing. After the first cut from the garden to the palace, a close up of May’s hand shows her slipping away from January’s grasp as he sleeps. The transition back to the garden involves three quick shots that focus on Damian: in the palace, a close up shows him return May’s silent mouthing with an inaudible chuckle before Pasolini cuts to a long shot of the tree in the garden and uses a jump cut to clearly show Damian within it and to recenter his gaze (Figs. 12-14).

Fig. 12. Final transition from the palace to garden.

Fig. 13. Final transition from the palace to garden.

Fig. 14. Final transition from the palace to garden.

These cuts are rendered fluid by audio smoothing that blends January’s groaning in the palace into the flute that accompanies the garden scenes. The smooth transition between spaces de-emphasizes the binary that Pasolini had set up between them but highlights the subversive power of the garden by focusing on Damian. Now, blind and in despair, January no longer has authority over this space. It is May who must guide his key to get access, and his grumbling is replaced by the clear, distinctive voices of Pluto and Proserpina as they orchestrate the events to follow: Pluto will restore January’s sight to reveal May’s treachery, but Proserpina will “teach her the words that will save her.” Indeed, it is also May’s voice and January’s blindness that enables her affair with Damian, as she tricks January into making a stepladder of his back by telling him she is pregnant (Fig. 15).[65]

Fig. 15. May tricks January into making a stepladder of his back.

Earlier, January’s voice and gaze were positioned as extensions of the institution that exerts its power upon its human subjects in a way that renders them consumable goods within a market. Now, the poor woman that he had tried to consume, as well as god and nature, or the very landscape itself, has the power to contaminate this process. For Pasolini, the immanent power of landscape interpenetrates with the institutional mechanisms of neocapitalism, just as the medieval contaminates the contemporary, and the cinematic apparatus itself oscillates between photo-realist capability and an amenability to myth.

Conclusion

It is no longer the majority opinion that the Middle Ages was a “finite cosmos.” However, much theoretical discourse in cultural studies remains predicated on a narrative of temporality where modernity is positioned, as the medievalist Geraldine Heng colorfully describes it,

simultaneously as a spectacular conclusion and a beginning: a teleological culmination that emerges from the ooze of a murkily long chronology by means of a temporal rupture – a big bang, if we like – that issues in a new historical instant.[66]

The prevalence of this narrative makes it seem natural to draw from Foucauldian or Marxist principles, suture theory, or other traditions such as the “history of vision” literature referenced at the beginning of this article in order to see Pasolini, arriving at the wrong side of this rupture, as presenting the Middle Ages as a mirror for the modern: a possible utopia, or a kind of tabula rasa of subjectivity. However, Pasolini’s ambivalence towards Chaucer suggests a more nuanced perspective, one that anticipates the insights that scholars of the late Middle Ages have recently brought to light. Chaucer’s was a heterogeneous poetics that was concerned with placing characters into a close relationship with meaningful settings, and in this I find a loose analogue with Pasolini’s approach. These are two artists concerned with interpretation as a mode of praxis, whose work was enabled by the same broad economic, social, and political globalizing forces that they sought to unsettle.

The spirit of these contaminating, place-oriented poetics marks the topography of this paper and its interpretive lens. Many scholars have shown us how Pasolini achieves a flattening of depth by drawing from medieval iconography as well as neighboring traditions such as theater and the visual arts, but I have focused on Pasolini’s use of classical devices precisely because we might consider it to be an impure exercise. Pasolini often railed against Hollywood, and strove throughout his life to develop an alternative Marxist poetics. In the spirit of Pasolini’s own logic, the analysis above demonstrates how his work depends on continuity devices that interpenetrate with those that stress fragmentation and disruption. Similarly, the common-sense reading of Pasolini’s work involves attending to the mythic invention of a past untainted by the forces of modernity, an archaic other against which our contemporary moment can be defined. However, inverting this relationship, and comparing the complicated social, economic, political, and ideological realities of Chaucer’s medieval world with Pasolini’s mythic version can deepen our understanding of the critical and historical work that the film can do. It is in his vision of a world comprised of mutually contaminating powers where we find a reflection of Chaucer’s global world as a nexus point between the medieval and the modern. Much recent Chaucerian scholarship emphasizes the proto-capitalist aspects of Chaucer’s medieval world, while drawing attention to the ambiguities, and the often-contradictory discourses that were operative during the period. It is in this complicated picture, of a world constituted by global networks of power and culture, replete with ideological ambiguities and contradictions, that we can find a subject matter suited to Pasolini’s aesthetic of contamination and the thematic tensions that characterize his work. But this is not a world that exists as a utopian alternative or mirror, but one that is in a continuum with our own.

I would like to thank Jeff Smith, Martin Foys, Elizabeth Bearden, and Different Visions‘ anonymous reviewers for their generous support and suggestions while writing this essay.

References

| ↑1 | Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1997 [1960]), 81. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For a survey of film theory’s connections to the medieval, see Bettina Bildhauer, “Forward into the past: film theory’s foundation in medievalism,” in Medieval Film, ed. Anke Bernau and Bettina Bildhauer (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), 40-59. |

| ↑3 | Giuliana Bruno, “Heresies: The Body of Pasolini’s Semiotics,” Cinema Journal 30 (1991): 29-42. https://doi.org/10.2307/1224928 |

| ↑4 | Bruno, “Heresies,” 31. |

| ↑5 | Patrick Rumble, Allegories of Contamination: Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996); Agnes Blandeau, Pasolini, Chaucer and Boccaccio: Two Medieval Texts and Their Translation to Film (Jefferson: McFarland & Company Inc. 2006). |

| ↑6 | Bruno, and many other commentators, have based this reinterpretation on the compilation and synthesis of Pasolini’s different writings, including his collections of essays in Passione e ideologia (Passion and ideology, 1960); writings in film magazines such as Filmcritica, Bianco e Nero, Cinema Nuovo and Cinema e Film (from 1965); his collection of essays and seminars on film semiotics in Empirismo eretico (Heretical empiricism, 1972); posthumously published anthologies of literary criticism Descrizione di descrizioni (Description of Descriptions, 1979) and Il portico della morte (The Arcade of Death, 1988). Bruno, “Heresies,” 30. |

| ↑7 | Pasolini’s approach towards the Other has also been considered naïve on the basis of his Eurocentricism and Orientalism. However certain scholars have reconsidered his views in light of his broader theory, his historical context, and by analyzing the films that were to be part of the Appunti per un poema sul Terzo Mondo (Notes for a Poem on the Third World, 1968), including Sopralluoghi in Palestina per Il Vangelo secondo Matteo (Location Scouting in Palestine for The Gospel According to Matthew, 1964); Appunti per un film sull’India (Notes for a Film on India, 1968); Appunti per un’Orestiade africana (Notes for an African Oresteia, 1969); and Le mura di Sana’a (The Walls of Sana’a, 1971). See for example, The Scandal of Self-Contradiction: Pasolini’s Multistable Subjectivities, Geographies, Traditions, eds. Luca Di Blasi, Manuele Gragnolati, and Christoph F.E. Holzhey (Berlin: Verlag Turia + Kant, 2012); Luca Caminati, “Notes for a Revolution: Pasolini’s Postcolonial Essay Films,” in The Essay Film: Dialogue, Politics, Utopia, eds. Elizabeth Papazian and Caroline Eades (New York: Columbia University Press, 2016); Cesare Casarino, “The Southern Answer: Pasolini, Universalism, Decolonization,” Critical Inquiry 36 (2010): 673-696. |

| ↑8 | Richard Burt, Medieval and Early Modern Film and Media (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). |

| ↑9 | Jacob Burckhardt, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, trans. S.G.O. Midlemore (London: Phaidon Books, 1965 [1960]), 81. |

| ↑10 | D.W. Robertson, A Preface to Chaucer (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1962), 51. In 1987, Lee Patterson found Chaucer studies divided between two approaches: the New Critical mode associated with E.T. Donaldson, and Robertson’s geistesgeschichtlich historicism. See Lee Patterson, Negotiating the Past: The Historical Understanding of Medieval Literature (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987), 3-9. |

| ↑11 | For a bibliography and discussion of the tendency to read Chaucer “socio-historically,” see Historians on Chaucer: The ‘General Prologue’ to the Canterbury Tales, eds. Stephen H. Rigby and Alastair J. Minnis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014). See also David Wallace, Chaucerian Polity: Absolute Lineages and Associational Form in England and Italy (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997). |

| ↑12 | Patterson, Negotiating the Past. |

| ↑13 | Medievalists and early modernists who critique the binary between the Renaissance and Middle Ages include the following: David Aers, “A Whisper in the Ear of Early Modernists; or, Reflections on Literary Critics Writing the ‘History of the Subject,’” in Culture and History 1350–1600: Essays on English Communities, Identities and Writing, ed. Aers (New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992), 177–202; The Challenge of Periodization: Old Paradigms and New Perspectives, ed. Lawrence Besserman (New York: Garland, 1996); James Simpson, Reform and Cultural Revolution (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2002); Simpson, “Diachronic History and the Shortcomings of Medieval Studies,” in Reading the Medieval in Early Modern England, ed. Gordon McMullan and David Matthews (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007), 17–30; Simpson, “Trans-Reformation English Literary History,” in Early Modern Histories of Time: The Periodizations of Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England, ed. Kristen Poole and Owen Williams (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), 88–101; Aers and Sarah Beckwith, eds., “Reform and Cultural Revolution: Writing English Literary History, 1350–1547,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 35, no. 1 (2005): 3–120; Jennifer Summit and David Wallace, eds., “Medieval/Renaissance: After Periodization,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 37, no. 3 (2007): 447–620; Brian Cummings and Simpson, eds., Cultural Reformations: Medieval and Renaissance in Literary History (Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press, 2010); Andrew Cole and D. Vance Smith, eds., The Legitimacy of the Middle Ages: On the Unwritten History of Theory (Durham, NC: Duke Univ. Press, 2010); and Holly A. Crocker, “The Problem of the Premodern,” Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 16, no. 1 (2016): 146–52. |

| ↑14 | Craig E. Bertolet and Robert Epstein, “Introduction: “Greet prees at Market ” – Money Matters in Medieval English Literature,” in Money, Commerce, and Economics in Late Medieval English Literature, eds. Craig E. Bertolet and Robert Epstein (Palgrave MacMillan: 2018), 1-10; Catherine Holmes and Naomi Standen, “Introduction: Towards a Global Middle Ages,” Past & Present 238, Suppl. 13 (2018): 1–44; Marion Turner, Chaucer: A European Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71900-9_1 |

| ↑15 | Turner argues that 1370s Florence might have had a particularly important impact on Chaucer. Here Chaucer was exposed to the works of Giotto, whose experiments with light, space, and movement were extolled by the poets that Chaucer read, and whose works were exhibited in the spaces he visited. She also demonstrates how the poetry of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio influenced his bold poetic experiments. Chaucer: A European Life, 161-5. |

| ↑16 | Pasolini (interview), in La voce di Pasolini, dir. Mario Sesti and Matteo Cerami (2005). Translation provided by Vita Nova, “The Beautiful Shape,” Medium, Waves-Onde, 5 March 2019, https://medium.com/waves-onde-en/the-beautiful-shape-c9b9c45566ea (accessed 2 August 2022). |

| ↑17 | During the shooting of Porcile, while he was scripting The Decameron, Pasolini told film historian Gian Piero Brunetta about a fundamental shift in his practice: “At first, I used technique to affirm reality, devour it, represent it in a way that was more corporeal, heavier; I tried with my camera to be true to the reality that belongs to other people, but no more. Now I use the camera to create a kind of rational mosaic that will render acceptable – clear and absolute- aberrant stories. The world will not be seen on screen through the eyes of Accattone or of Stracci, but through the unashamedly composing vision of a narrator (Giotto, Chaucer) who assembles the ‘rational mosaic.’” The rest of this section discusses Pasolini’s shifting poetics during this period. Cited in Barth David Schwartz, Pasolini Requiem (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2017 [1992]), 528. |

| ↑18 | On the provenance of Divine Mimesis and Pasolini’s identification with Dante, see Gian Maria Annovi, “Dante,” in Pier Paolo Pasolini: Performing Authorship (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017), 49-70. For a more general study of Dante’s influence on Pasolini and especially his representation of subalterns, see Emanuela Patti, Pasolini after Dante: The ‘Divine Mimesis’ and the Politics of Representation (Cambridge: Routledge, 2016). https://doi.org/10.7312/columbia/9780231180306.003.0003 |

| ↑19 | Commenting on his decision to play Giotto, Pasolini said that “I have created a perfect analogy: I played the role of a Northern Italian artist who therefore comes from historical Italy and goes down to Naples to paint frescoes (exactly according to this ontology of reality) on the walls of the Church of Santa Chiara. And, in fact, I am a Northern Italian from the historical part of Italy who goes to Naples to make a realistic film. Thus, there is an analogy between the character and the author … a work within the work.” Cited in Naomi Greene, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Cinema as Heresy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 186. |

| ↑20 | Pier Paolo Pasolini, “The Cinema of Poetry,” in Movies and Methods. Vol 1., ed. Bill Nichols (Berkely: University of California Press, 1976 [1965]), 548. All other quotes in this paragraph are from this essay. |

| ↑21 | See for example, Pasolini’s comparison of the cinematographic language to the reader’s encounter with a “primitive language,” in “The Screenplay as a ‘Structure that Wants to Be Another Structure,’” American Journal of Semiotics 1 (1986): 53-72 (58). https://doi.org/10.5840/ajs198641/28 |

| ↑22 | Cited in Schwartz, Pasolini Requiem, 548. |

| ↑23 | Pier Paolo Pasolini, “The Unpopular Cinema” and “The Written Language of Reality,” in Heretical Empiricism, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2005 [1972]), 269; 204. |

| ↑24 | Pier Paolo Pasolini, St Paul: A Screenplay, trans. Elizabeth A. Castelli (London: Verso, 2014 [1977]), 32. |

| ↑25 | In the introduction to his screenplay, Pasolini tells us that “none of the words pronounced by Paul in the film’s dialogue will be invented or reconstructed by analogy,” and that he wants to “transpose his life on earth to our time” in order to “present, cinematographically in the most direct and violent fashion, the impression and the conviction of his reality/present.” Ibid, 33. |

| ↑26 | Noa Steimatsky, “Archaic: Pasolini on the Face of the Earth,” in Italian Locations: Reinhabiting the Part in Postwar Cinema (The University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 138. |

| ↑27 | David Ward, “A Genial Analytic Mind: ‘Film’ and ‘Cinema’ in Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Film Theory.” Pier Paolo Pasolini: Contemporary Perspectives, eds. Patrick Rumble, and Bart Testa (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994), 127-151. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442678484-012 |

| ↑28 | Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Observations on the Sequence Shot,” in Heretical Empiricism, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2005 [1972]), 234. |

| ↑29 | Ibid, 235. |

| ↑30 | Ward, “A Genial Analytic Mind,” 144. |

| ↑31 | Cited in Greene, Cinema as Heresy, 191. |

| ↑32 | Blandeau, Pasolini, Chaucer and Boccaccio, 14; Kathryn L. Lynch, “Idols of the Marketplace: Chaucer/Pasolini,” 143. |

| ↑33 | Cited in Paul Willemen, Pier Paolo Pasolini (London: BFI, 1977), 77. |

| ↑34 | See Patrick Rumble for a discussion. Rumble, Allegories of Contamination, 3-15. |

| ↑35 | Many critics on the Left in Italy rejected the film for its lack of overt ideology. For example, fellow Marxist director Bernardo Bertolucci is reported to have said the work could only have been made by a “reactionary poet.” Footnote cited in Gino Moliterno, “The Canterbury Tales,” Senses of Cinema 19 (2002), https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2002/cteq/canterbury/ (accessed July 31, 2021). |

| ↑36 | For a collection of materials, including production stills, essays, documentaries, and interviews on the making of The Trilogy of Life, see the special features released with the box-set by Criterion, and their accompanying webpage: “From the Pasolini Archives,” Criterion.com, March 5, 2018, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/5447-from-the-pasolini-archives, last accessed July 31, 2021. |

| ↑37 | Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Quips on the Cinema,” in Heretical Empiricism, trans. Ben Lawton and Louise K. Barnett (Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, 2005 [1972]), 231. |

| ↑38 | Leicester writes that: “The Canterbury Tales is not written to be spoken as if it were a play. It is written to be read, but read as if it were spoken. The poem is a literary imitation of oral performance” and that “While any text can be read in a way that elicits its voice, some texts actively engage the phenomenon of voice, exploit it, make it the center of their discourse – make it their content. A text of this sort can be said to be about its speaker, and this is the sort of text I contend that the Canterbury Tales is and especially the sort that the individual tales are. The tales…concentrate not on the way preexisting people create language but on the way language creates people.” H. Marshall Leicester, Jr., “The Art of Impersonation: A General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales,” PMLA 95 (1980): 221, 217. https://doi.org/10.2307/462016 |

| ↑39 | Cited in Greene, Cinema as Heresy, 188. |

| ↑40 | Agnes Blandeau also argues that he used this dialect to signal “vernacularity,” Blandeau, Pasolini, Chaucer and Boccaccio, 51. |

| ↑41 | D’Arcens advances this claim by drawing both from Blandeau’s work on the Canterbury Tales as well as from Pasolini’s statements in Heretical Empiricism: “Pasolini argues that ‘just as the phenomenon of lightning and thunder is a single atmospheric phenomenon’ so too the speaking image and dubbed voice are one; but the ‘thunder’ of the track is, nevertheless, ‘a sort of regurgitation or yawn which hobbles behind the lightning.’” Footnote cited in D’Arcens, “The Thunder after the Lightning,” 194. |

| ↑42 | D’Arcens, “The Thunder after the Lightning,” 197. |

| ↑43 | Greene’s chapter on the Trilogia and Salò considers in detail Pasolini’s increasing pessimism in a political context during his final years. Greene, “The Many Faces of Eros,” in Cinema as Heresy, 173-217. |

| ↑44 | Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Tetis,” Pier Paolo Pasolini: Contemporary Perspectives, ed. Patrick Rumble and Bart Testa, trans. Patrick Rumble (Toronto: University of Toronto, 1994), 246. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442678484-018 |

| ↑45 | Kathleen Forni, “A ‘Cinema of Poetry:’ What Pasolini Did to Chaucer’s “Canterbury Tales,” Literature/Film Quarterly 30 (2002): 256. |

| ↑46 | Rumble argues this can be read as ironic or even parodic reference to Boccaccio and Chaucer’s own ironic recantations. For a full discussion see Rumble, Allegories of Contamination, 82-99. |

| ↑47 | For an account of the Trilogia’s reception, including Pasolini’s legal battles and the withdrawal of I racconti di Canterbury from circulation, see Schwartz, “The Trilogy of Life,” in Pasolini Requiem, 521-62. |

| ↑48 | For film scholarship on the past’s resonances in the present see Marcia Landy, Cinematic Uses of the Past (London: University of Minnesota Press, 1996); Robert A. Rosenstone, History on Film/Film on History (New York: Routledge, 2013 [2006]); and medieval films are analyzed in this vein in Laurie A. Finke and Martin B. Shichtman, Cinematic Illuminations: The Middle Ages on Film (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010); Race, Class and Gender in ‘Medieval’ Cinema, edited by Lynn T. Ramey and Tilson Pugh (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). |

| ↑49 | Geraldine Heng, The Global Middle Ages: An Introduction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 2-5. The project can be found at http://globalmiddleages.org/projects |

| ↑50 | Kathleen Davis and Nadia Altschul, eds., Medievalisms in the Postcolonial World: The Idea of “the Middle Ages” Outside Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 2009), 9. See also Kathleen Davis, Periodization and Sovereignty: How Ideas of Feudalism and Secularization Govern the Politics of Time (Philadelphia, Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2008). |

| ↑51 | Kathleen Davis and Michael Puett, “Periodization and the ‘Medieval Globe’: A Conversation,” The Medieval Globe 2 (2015): 1-14. https://doi.org/10.17302/tmg.2-1.2 |

| ↑52 | Ibid, 11. |

| ↑53 | See the works cited in footnotes 49-52 above, and also Carol Symes, “When We Talk about Modernity,” The American Historical Review 116, no. 3 (2011): 715–26; and Susan Stanford Friedman, Planetary Modernisms: Provocations on Modernity Across Time (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015). |

| ↑54 | Deleuze himself invokes Pasolini to develop his own film theory throughout both his books on cinema. Pasolini is especially important to Deleuze’s reconceptualization of “free indirect discourse” as the “free indirect image” and his illustration of the “perception image.” Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and B. Habberjam (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986 [1983]); Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989 [1985]). |