KellyAnn Fitzpatrick • Senior Industry Analyst, RedMonk

Recommended Citation: KellyAnn Fitzpatrick, “Constructing Gender in Visual Medievalisms: What an Art Historian has Taught me about Digital Gaming,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 8 (2022). https://doi.org/10.61302/ZNOZ6301.

Whether or not you have spent time rescuing Zelda, questing in Skyrim, or even just binging The Witcher on Netflix, it is hard to miss popular culture’s plethora of (neo)medievalisms and their often complicated relationship to the Middle Ages. While my own relationship with these medievalisms began as a consumer (I have rescued Zelda many times), they eventually wound their way into my scholarship, including a monograph on neomedievalism.[1] Although my formal training is in English and medieval studies, art history and its disciplinary conventions have played an essential role in my work, due in no small part to Rachel Dressler’s influence as a mentor, scholar, and collaborator. What follows is a brief record of that influence and some insights into how it has informed my work with visual (neo)medievalisms such as those found in digital games.

Figure 1. Rachel Dressler dressed as Empress Adelheid, 2002.

I met Rachel–then a faculty member in the Department of Art and Art History at the University at Albany (SUNY)–during my first year as a Ph.D. student in the English Department. I was delighted to meet one of the few other medievalists on campus (and most immediately her insight into how to navigate the various wine hours at Kalamazoo was invaluable). The following year, when a group of us put on an adaptation (with frame play) of Hrotsvit of Gandersheim’s tenth-century martyrdom play Sapientia, Rachel not only supported and advised the venture (including serving as sound and visual designer), but reached back to her dramatic roots to take on the frame play role of Empress Adelheid (Fig. 1). Rachel was kind enough to let me audit her course on Women in Medieval Art and Society and her excellent seminar on the Medieval Revival. Rachel’s own knowledge of and scholarship on medievalism[2] landed her on my dissertation committee, where her advice and patience proved vital in completing the project and eventually translating it into a book.

One key element that I have taken from Rachel’s perspective is how art works to construct gender. She articulates this brilliantly in her 2007 MFF article on “Continuing the Discourse: Feminist Scholarship and Medieval Art.”[3] In a then-recent survey of the types of feminist scholarship on medieval art, she acknowledges the value of approaches that examine both women artists and the role art plays in capturing women’s experiences. She then emphasizes the importance of scholarship that “incorporates the insights of poststructuralist theory to examine the ideological work performed by the visual construction of gender” (24).

Of the approaches that Rachel outlines, the ones that I have found most useful are those that examine the ideological work that continues to be performed by visual constructions of gender in digital mediums. In my own work, I’ve focused on visual constructions of gender in medievalisms such as Disney’s 1959 animated Sleeping Beauty (Fig. 2) and 2014 live action (but heavily reliant on CGI, or “computer-generated imagery”) Maleficent, and the fully CGI 2007 film Beowulf. In Neomedievalism, Popular Culture, and the Academy, I examine aspects such as ideals of feminine and masculine beauty, activity/passivity, narrative control, monstrosity, how these things shift from 1959 to 2014, and how they perhaps need to shift some more. I argue that these medievalisms lay claim to a posited historic medieval past (while also consciously deviating from it), locating specific twentieth and twenty-first-century gender constructions in medieval history both to link them to specific historical referents and to cast them as timeless, real, and rooted in transcendent truth. The result: a seemingly contradictory blending of “how it has always been” and “how it really was.”[4] Visuals, of course, play an important role in constructing not only gender, but also the medievalesque and medieval-fantasy settings against which this ideological work is performed.

Figure 2. A scene from Sleeping Beauty (1959) that helps visualize the film’s stated fourteenth-century setting through the stylized depiction of knights and architectural details such as crenellation.

In addition, the other feminist approaches that Rachel outlines in “Continuing the Discourse” could usefully be employed to analyze digital gaming. Some approaches might focus on content creators, and indeed recent lawsuits, most notably against game producers like Activision/Blizzard (which produces World of Warcraft) and Riot Games, bring to light just some of the difficulties that women creators face in the industry (another key starting point would be the series of instances of online harassment and threats to visible women in the game industry known as Gamergate[5]). Others might look to the experiences of women as game players (including, unfortunately, the high level of harassment aimed at female players), the increasing proportion of gamers who identify as female, or the capacity for the topics and stories within and around gaming to capture women’s experiences.

Rachel has also influenced my examination of Magic the Gathering: Online,[6] the digital version of what started out as a trading card game. Both digital and physical cards include various numbers and indicators needed for the mechanics of gameplay, but the main visual for each card is an illustration accompanied by snippets of “flavor text” designed to suggest narrative possibilities for each entity. While there is a lot to unpack in the themes running through the various editions and sets of cards released over the years, one trend I’ve noticed—inspired by Rachel’s analysis of constructions of masculinity in her article “Cross-Legged Knights and Signification in English Medieval Tomb Sculpture”[7]—is the updating of visuals to make figures (usually those presenting as male) more active. See, for instance, the evolution of the visuals for the “Northern Paladin” card. In earlier editions the view is presented with the title character’s figure presented in a static, portrait-like pose with no weapon in sight. In later editions, the figure appears to rush at the viewer in more fantastical, action-oriented style armor while brandishing a blazing sword.

One additional area where there is much to be gained by examining the visual construction of gender in digital medievalisms is in games where players assume one or more point of view character (a “player character” or “playable character” for short). This overlap of game character and game audience often results in interesting intersections in how both are constructed, especially as concerns gender. It is worth noting that medievalism in gaming has its own long history, one that can be traced partly back to Dungeons & Dragons, and from there to J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle-earth. This history brings with it in-game conventions around narrative and game mechanics as well as articulations of race and gender, but also a history of assumptions around who is seen as the target audience for consumption of the commodity that such games often constitute. This in turn has influenced the characteristics of available player characters. With some exceptions (e.g., Thyra the Valkyrie in Gauntlet), the vast majority of playable characters in early medieval-inspired and medieval fantasy video games are figured as male. While this seemingly expanded in the late 1990s and early 2000s to introduce female player character options (e.g., the Baldur’s Gate and Champions of Norrath series), such options (à la Lara Croft: Tomb Raider) are often constructed for a male gaze rather than female or queer identifying players and audiences.

The massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) World of Warcraft, for instance, lets each player name and customize their own player character by choosing from a variety of pre-set options. Appearance options include a range of hair styles and colors, skin tones and tattoos, with different types of armor rendering distinctly from each other. Gender options are limited to a male/female binary, with the same armor type often revealing considerably more skin (including cleavage) for a female version of a character than a male version. Differences in posture and stance (also prevalent among the game’s non-player characters, or NPCs) also work to show male characters are active, solid, and ready for combat while their female counterparts often appear to be presenting themselves entirely for the viewer’s gaze. See, for instance, the differences in resting posture between the male and female Blood Elf characters in World of Warcraft. Male incarnations are positioned with their torsos square with their lower bodies (even when their eyes gaze off in three-quarter profile), with shoulders and heads pitching slightly forward, expressing an attitude that they are ready for movement. Female incarnations are positioned with torsos and lower bodies at different angles, and with their right legs stepping forward with weight seemingly positioned on their back left legs: a much less active stance (Fig. 3). It is also worth noting that although both male and female incarnations are both scantily clad when stripped of all equippable armor and clothing, when the characters are rotated in the game view, the female incarnations’ derrieres and upper thighs are almost completely exposed. This is not the case, however, for the male versions (Fig. 4).

Figure 3. Front-view screenshots from World of Warcraft of a female Blood Elf (left) and a male Blood Elf (right).

Figure 4. Rear-view screenshots from World of Warcraft of a female Blood Elf (left) and male Blood Elf (right).

In situations where female player characters are not hypersexualized or visually constructed as less active and vital, they are often decentered or omitted in promotional material in favor of a character who reads as male. The 2020 game Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, which is notable for being the first installment in the Assassin’s Creed series to feature a single main character, Eivor, that can be played as either a woman or a man (Figs. 5 and 6),[8] nevertheless features the male Eivor in its prominent promotional material, including the initial game packaging.

Figure 5. Screenshot of the Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla inventory screen (early in the game) while playing Eivor as female.

Figure 6. Screenshot of the Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla inventory screen (early in the game) while playing Eivor as male.

I hope that the brief survey above demonstrates that although digital games are new, ephemeral, and often highly commoditized entities, the approaches used to critique constructions of gender in medieval art can be extremely useful in reading the visual medievalisms such games create. To my mind, such endeavors will grow increasingly important as digital worlds play an even greater role in shaping public discourse, with medievalisms manifesting in ways similar to those Rachel writes about in her own excellent post on masculinity, the romanticization of knighthood, and confederate monuments,[9] but in virtual spaces and objects rather than physical ones.

I also hope that I have conveyed how truly indebted I am to Rachel and her work for helping to set me on my path; ever since her perspectives on art landed on my radar, rescuing Zelda has (thankfully) never quite been the same.

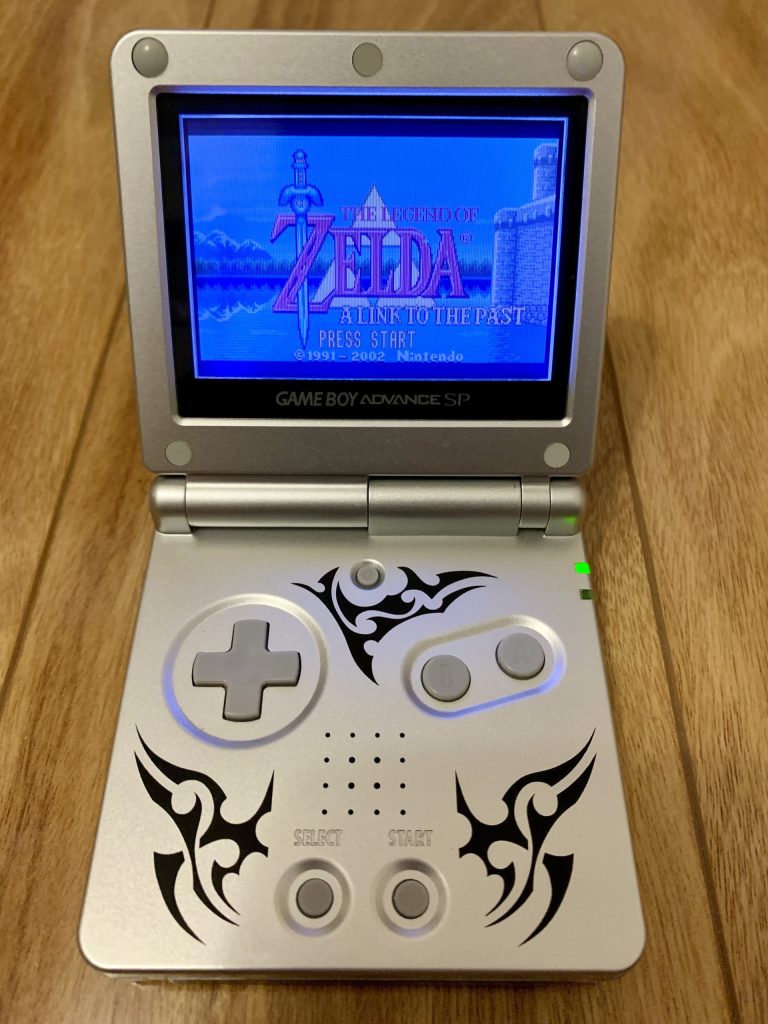

Figure 7. Start screen for The Legend of Zelda: a Link to the Past (1992) as shown on the author’s Nintendo Gameboy Advance SP.

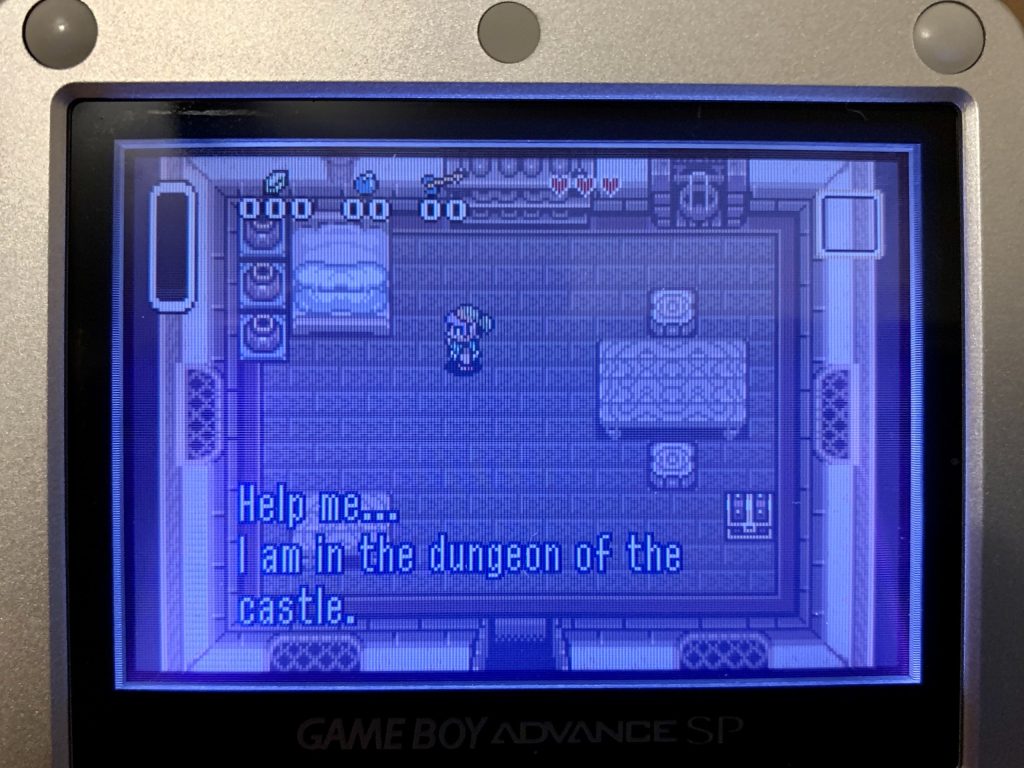

Figure 8. Image from The Legend of Zelda: a Link to the Past wherein the author of this article–playing as Link–prepares to go rescue Zelda.

References

| ↑1 | KellyAnn Fitzpatrick, Neomedievalism, Popular Culture, and the Academy From Tolkien to Game of Thrones (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781787447028 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Rachel Dressler, “‘Those effigies which belonged to the English Nation’: Antiquarianism, Nationalism and Charles Alfred Stothard’s Monumental Effigies of Great Britain,” Studies in Medievalism XIV (2005): 143-74. |

| ↑3 | Rachel Dressler, “Continuing the Discourse: Feminist Scholarship and Medieval Art,” Medieval Feminist Forum 43.1 (2007): 15-34. https://doi.org/10.17077/1536-8742.1022 |

| ↑4 | There is a lot of excellent work being done on gender, the Middle Ages, and how perceptions of gender in the Middle Ages are leveraged in popular thought today. See, for instance, the online magazine The Public Medievalist’s series on gender at: https://www.publicmedievalist.com/gsma-toc/ |

| ↑5 | For an excellent overview of this series of incidents, see Anastasia Salter and Bridget Blodgett, Toxic Geek Masculinity in Media: Sexism, Trolling, and Identity Policing (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 89-93. |

| ↑6 | See Chapter 5 of Neomedievalism, Popular Culture, and the Academy. See also KellyAnn Fitzpatrick, “Commodifying the Medieval in Magic: Online,” in Neomedievalism in the Media: Essays on Film, Television, and Electronic Games, ed. Carol L. Robinson and Pamela Clements (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 2012), 251–81. |

| ↑7 | Rachel Dressler, “Cross-Legged Knights and Signification in English Medieval Tomb Sculpture,” Studies in Iconography 21 (2000): 91-121. |

| ↑8 | Previous installments either feature a male main character or, like Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (2017), allow players to switch back and forth between two siblings, one female and the other male. |

| ↑9 | Rachel Dressler, “Growing Up in the Shadow of the Mountain,” The Material Collective, August 10, 2020. https://thematerialcollective.org/growing-up-in-the-shadow-of-the-mountain/. |