Meg Bernstein • Alfred University

Recommended citation: Meg Bernstein, “Climbing the Ladder to Heaven: Inventing an Iconography of Purgatory,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 7 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/BNRG4276.

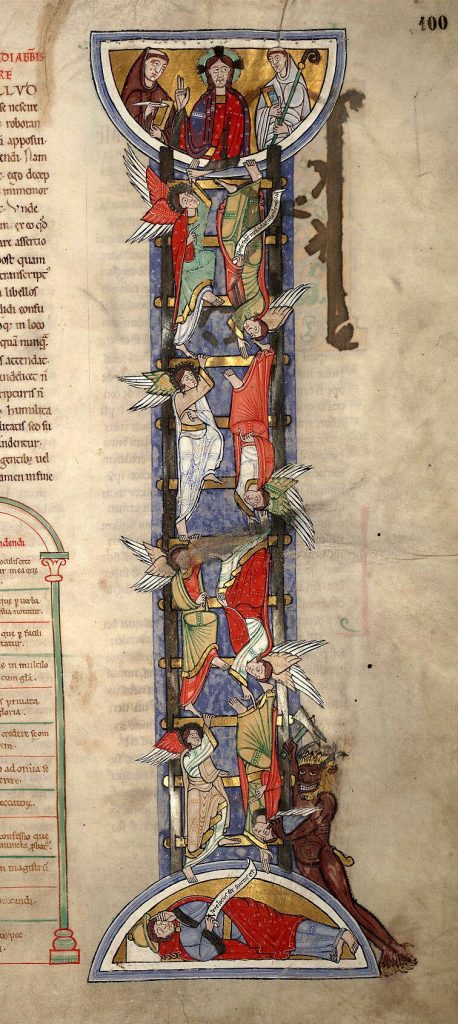

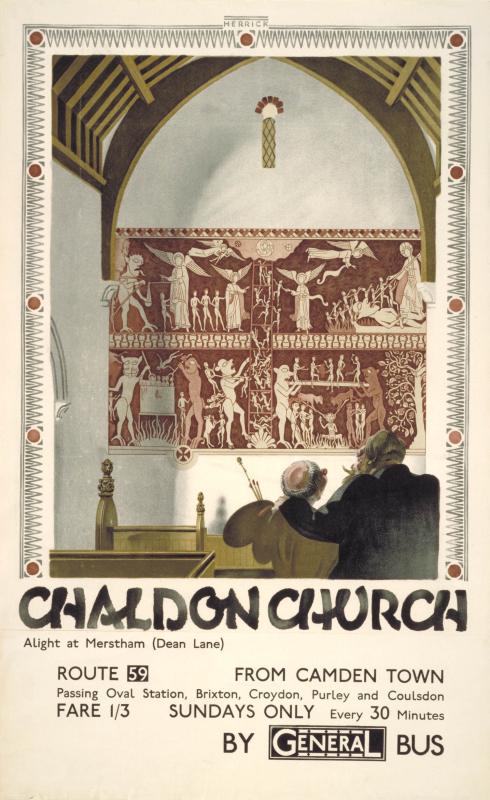

Fig. 1. St. Peter and St. Paul, Chaldon (Surrey), interior view to the southwest featuring mural on the west fall (photo: Roy Reed).

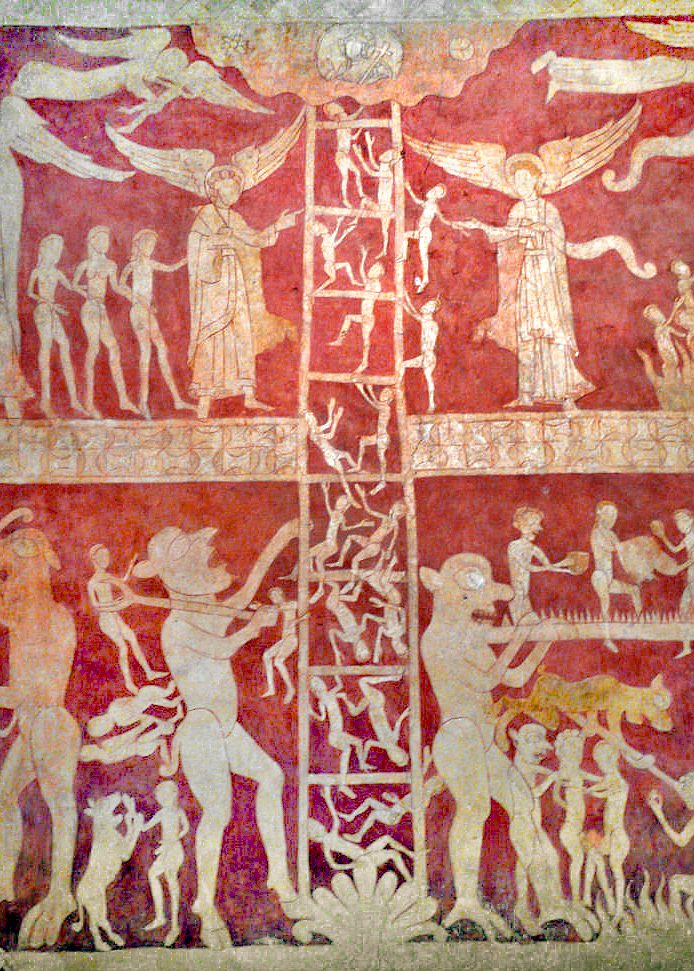

While the parishioners of the church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Chaldon in Surrey, approximately fifteen miles from London, face the altar in the chancel during the Mass, an arresting scene plays out behind their backs on the western wall of the church (Fig. 1). Nestled between the arcade responds separating the nave from side aisles, this painted composition is composed of two main registers, connected by a vertical passage: a ladder that reaches from the bottom of the composition to the top, where Christ appears nimbed and bust-length, in a roundel situated among a wavy, cloud-like puff (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Detail of Christ and upper ladder, Chaldon (photo: Wikimedia commons, CC0).

Since the mural’s rediscovery in the 1870s, several scholars have contributed substantially to the discussion of the painting’s unusual iconography.[1] This essay further contributes to this body of literature, asserting that the architectural context where the painting is situated, and the liturgical context of the consecration cross at the bottom of it, allow us to deepen our understanding of the work. The ladder motif is precocious and novel within its parochial context. Through a consideration of the painting’s role in the architectural space of its building, and by focusing on lay piety and the nascent understanding of purgatory, I argue that in the historical moment this mural was made, a new eschatology specifically formulated for and by lay people was being experimented with and developed. I suggest the Chaldon mural represents an imaginative, innovative way to reflect the concept of purgatory, answering the call of representing it as a place, but one which is liminal, temporary, and necessitates forward motion. While the Chaldon solution for representing purgatory was never imitated elsewhere, it is nonetheless in conversation with other eschatological visual and textual sources from the Middle Ages.

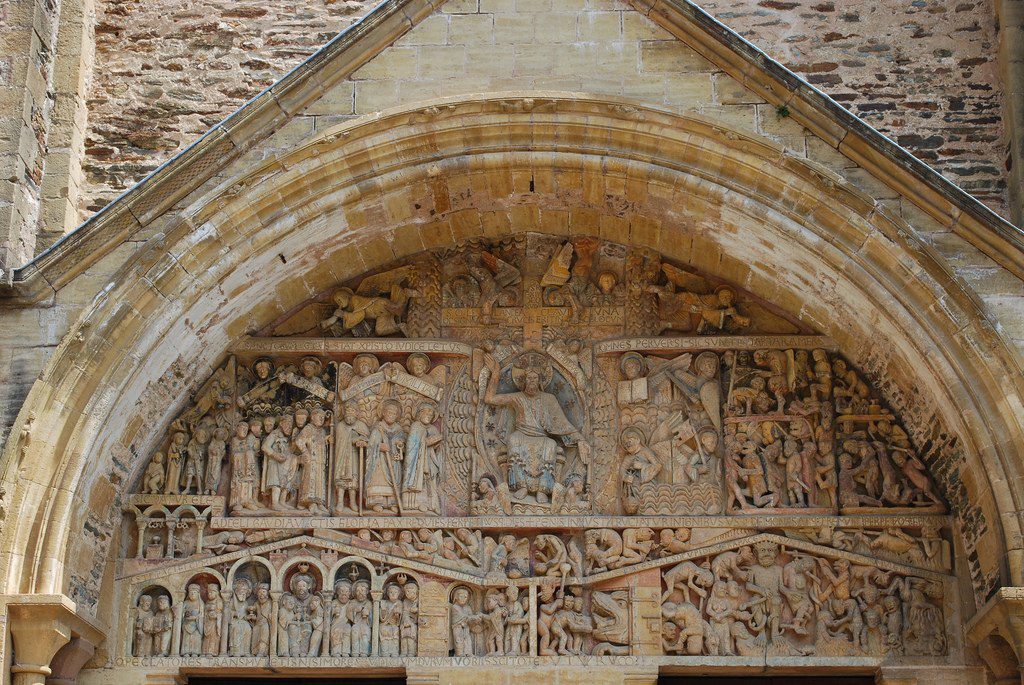

Fig. 3. Last Judgment tympanum, Church of Sainte‐Foy, France, Conques, c. 1050–1130 (photo: Òme deu Teishenèir, CC BY-SA 2.0).

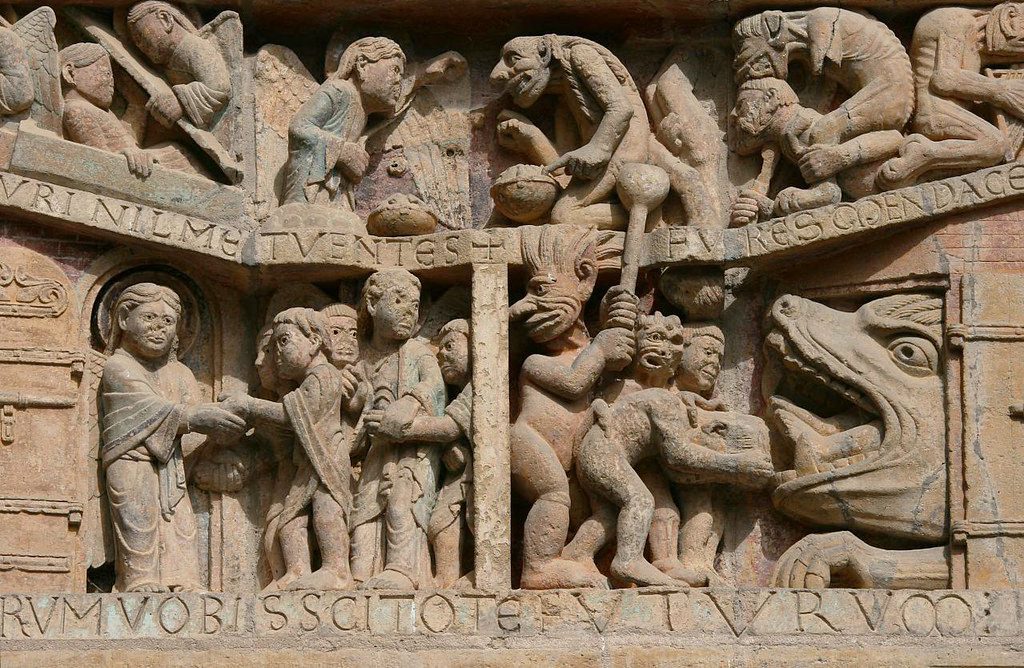

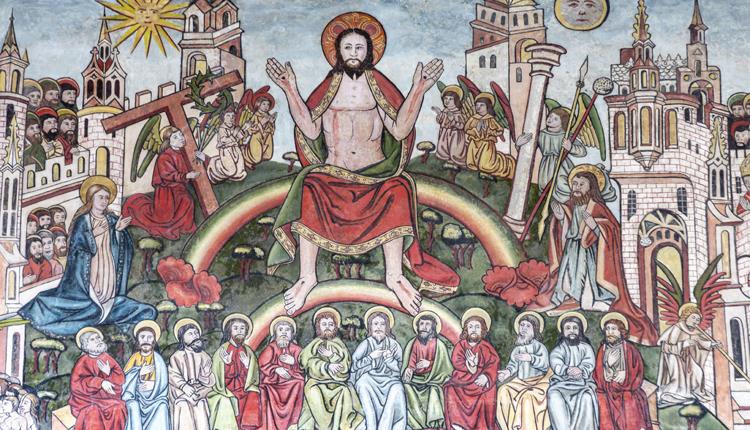

Some of the most familiar images in medieval art are those that depict the sharp dichotomy between heaven and hell. The Last Judgement tympanum at Sainte-Foy in Conques, on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, is easily legible (Fig. 3).[2] Christ is seated at center, in judgement. To his right, queuing decorously behind the Virgin Mary and Saint Peter, are those about to be saved. The narrative continues beneath them, where the saved are welcomed into heaven via a rounded portal (Fig. 4). The saved sit, erect and confronting, in arcades. On Christ’s left, however, things are very different. Rather than the pleasant, peaceful, orderly scene in heaven, writhing bodies and fearsome demons populate hell, enacting various gruesome torments on the damned.

Fig. 4. The gates of heaven and the mouth of hell (detail), Last Judgment tympanum, Church of Sainte‐Foy, France, Conques, c. 1050–1130 (photo: Holly Hayes, CC BY-NC 2.0).

On the Conques tympanum, there seems to be no ambiguity between heaven and hell: the conditions in the two places are starkly different. This dichotomy represents the prevailing visual representation of the afterlife for most medieval Christians up until at least the middle of the twelfth century. Yet even before this, there was some belief that there was an intermediary period in the afterlife that caused prayers for a person’s soul to be efficacious. This is evident in the writings of the church fathers, like St. Cyril of Jerusalem who in the fourth century described that in the mass: “Then we make mention also of those who have already fallen asleep… for we believe that it will be of very great benefit to the souls of those for whom the petition is carried up, while this holy and most solemn sacrifice is laid out.”[3] Yet, these early statements from the church fathers do not provide specific details about the place where these sleeping souls rest.

Although the idea of an intermediary realm distinct from Heaven and Hell was not new in the twelfth century, only in the second half of the twelfth century did purgatory as such come to be discussed as a specific place and entity.[4] Jean Beleth, a canon of Notre-Dame in Paris, wrote around 1165 that while some souls were believed to go directly to heaven or hell, “(t)here are others, in the middle, for which a recommendation of this sort must be made.[5] One of Peter Comestor’s sermons from the third quarter of the twelfth century uses the phrase “in purgatorio,” showing that the concept was in use by 1175.[6] Although not formalized by the Catholic Church until the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, the concept was already in strong circulation a century earlier.

According to Jacques Le Goff, the true triumph of the doctrine of purgatory was not with clerics, but with the populace, where it “scored a tremendous success.”[7] The potential of redemption through prayers was appealing to lay people as it gave them the sense of having some agency over their afterlives. It is therefore unsurprising that in the realm of the parish church evidence of belief in purgatory and a wish for purgation can be seen even from a very early date. It is difficult to overstate how critical the introduction of purgatory was within the Latin church from the thirteenth century forward. It precipitated an economy of chantry masses, coupled with, in some cases, extravagant, purpose-built chantry chapels. It also led to the production of indulgences which would become one of the complaints of Protestant reformers.

Yet, in spite of the undeniable prevalence of purgatory in the lives and deaths of medieval Christians from the twelfth century forward, Paul Binski has observed that in the Middle Ages, there was a representational silence in the depiction of purgatory, at least in the century or two after the Second Council of Lyon.[8] There is a corpus of later medieval images in various media, like an extraordinary Carthusian manuscript, where Purgatory is clearly labelled.[9] Yet in general, these images are from the fifteenth century—not the decades when the doctrine of purgatory was reaching a fever pitch in interest, particularly from lay people.

The Mural

The church at Chaldon is small, and from the exterior, unassuming.[10] There has been a church in Chaldon at least since the manor was recorded in Doomsday Book in 1086 as being held by Ralph Fitz Turold; later, the living of the church was a rectory, the advowson held by Roger de Covert in 1275 who reserved it for his heirs.[11] The right of advowson remained tied to the lord of the manor until 1715.[12] In 1870, Chaldon was the site of a remarkable discovery. During building work, the rector, Reverend Henry Shepherd spotted signs of a painting when the whitewash was disturbed, locating a previously unknown mural, and causing it to be saved.[13]

Locating previously unknown medieval wall paintings in the nineteenth century is not in and of itself unusual. Medieval churches were widely covered with wall paintings, which were limewashed by the brushes of iconoclastic reformers under Edward VI (r. 1547-1553).[14] What is remarkable about the Chaldon discovery is its subject matter and unusual iconography, which has been the subject of debate since its discovery in 1870. Frustratingly little is known about the mural from a historical perspective: who commissioned it, commented on the iconography desired, and paid the bill? Where did the painter or painters responsible come from? Local monasteries like Chertsey or Merton have been suggested as possibilities for the origin of the painter, but this is purely speculation.[14] As is typical of English parish churches before the fifteenth century, these are questions that cannot, at present, be confidently answered. Most previous authors on the Chaldon mural have focused on formal accounts and debates over iconography,[15] or have used it to illustrate wider points about death and purgatory in the medieval world. This article, by contrast, centralizes the mural in its environment of the parish church, and within its contemporary religious climate.

Based on style, the mural has been dated around 1170 or 1200.[16] The mural is executed on lime plaster, using yellow and red iron oxide pigments. The mural has been extensively restored: the red areas have been overpainted, and the red outlines have been strengthened. Some fine lines on the tree at bottom right have been spared. It was first restored at the time of its discovery.[17] A report from 1954 confirms that the painting had, at some point, been coated with a thick layer of wax by a restorer intending to preserve the image; however, even by 1954, this was no longer considered best practices by conservation professionals and its removal was recommended.[18] Further restoration was undertaken in 1989 by Wolfgang Gärtner.[19] Gärtner speculated that a top layer of paint has been lost which would have provided more detail and a wider variety of colors.[20] However, twelfth century English wall painting used only a small range of colors; a high status painting might include green, blue, and vermillion, but most would use a limited palette of yellow and red ochres—clays that could be naturally pigmented by iron content.[21] Thus, the painter of the Chaldon mural, working in a local parish church, would have likely used a color palette not materially different from the one we see today, even if this was only an underdrawing.

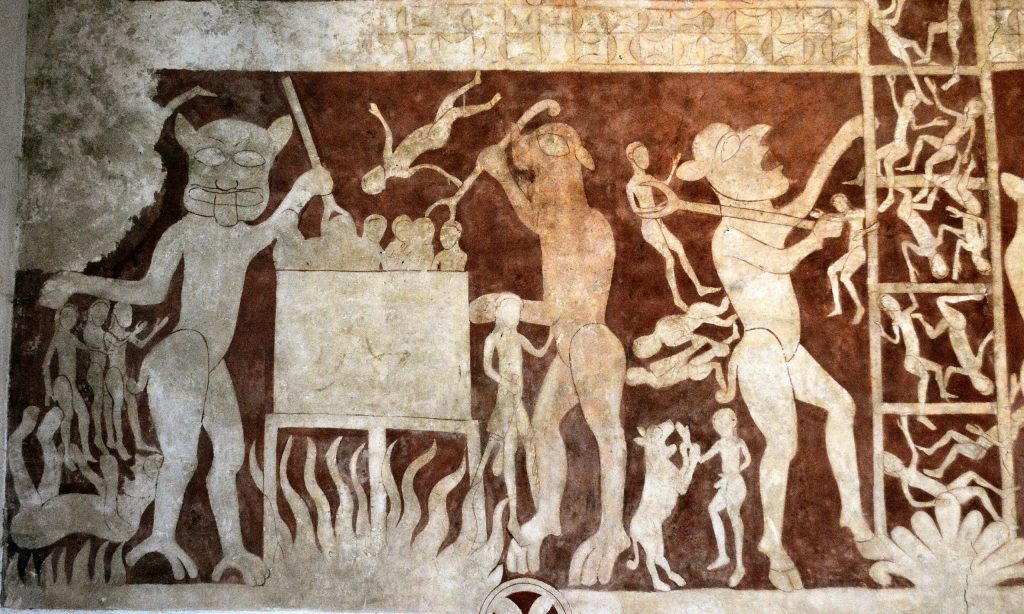

Fig. 5. Devils cooking souls in a cauldron, Chaldon (photo: Andy Scott, CC BY-SA 4.0).

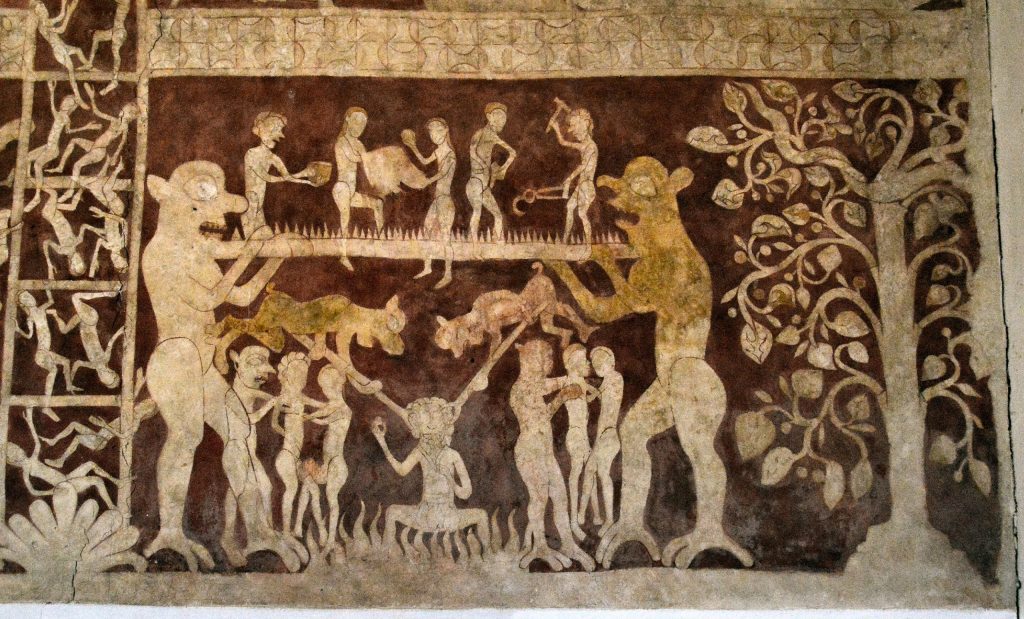

Fig. 6. Bridge of spikes, Chaldon (photo: Andy Scott, CC BY-SA 4.0).

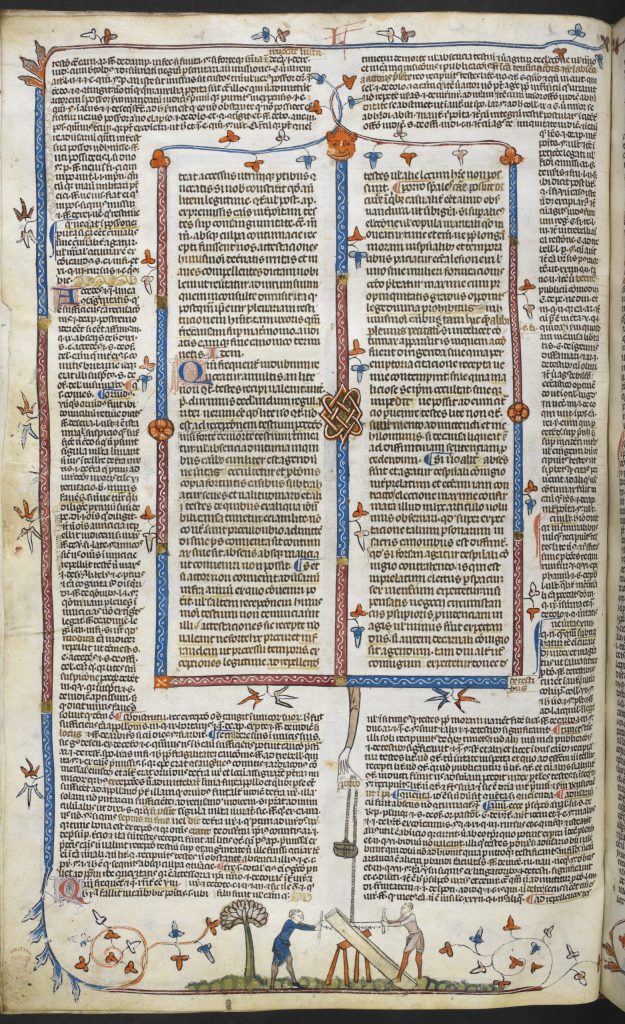

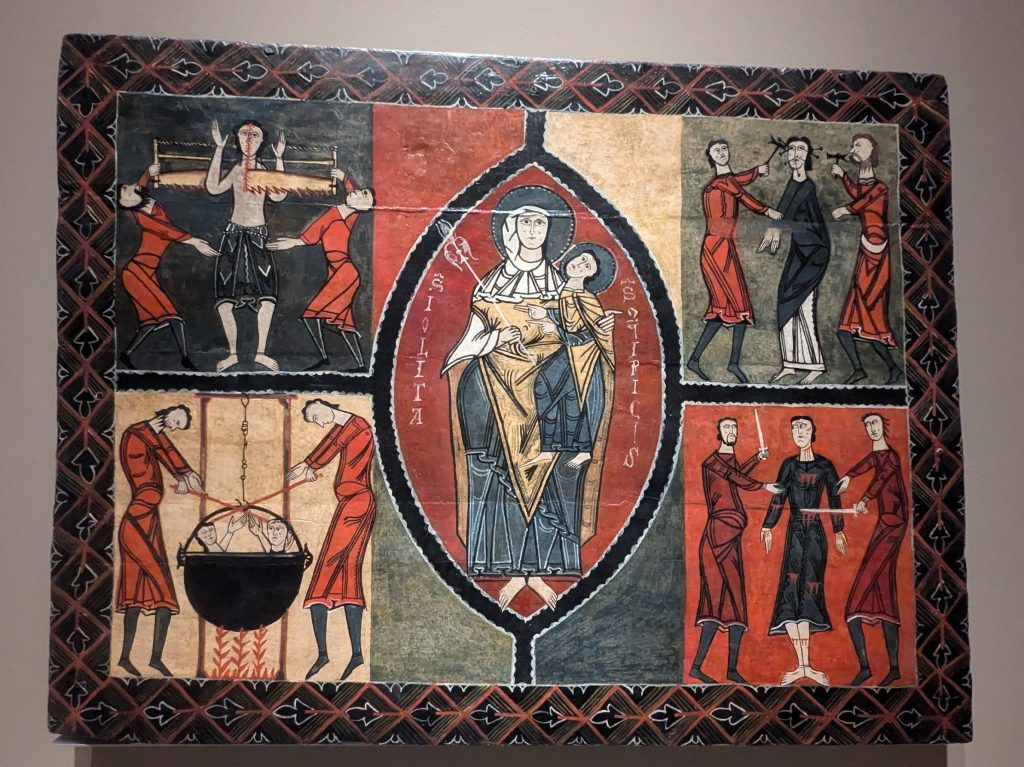

The bottom register of the Chaldon mural depicts hell. On the left of the ladder, two bird-footed demons cook souls in a cauldron raised over violent flames (Fig. 5). On the right, a second pair of demons elevate a spiky upside-down crosscut saw (Fig. 6), where souls seemingly continue to perform their trades from life under what Ernest Tristram called “insuperable difficulties”: a potter attempts to shape a pot, a woman spins yarn without a distaff, and two blacksmiths make a horseshoe without an anvil; a second woman’s task is unidentifiable due to loss of a passage of paint.[22] The figures here are precariously perched, neither standing nor sitting on the torturous device. The sawblade forms a visual opposite with the ladder in the center of the painting—unlike in the ladder, where vertical movement is possible, the sawblade bridge offers no end to suffering, because the destination on either end is the mouth of a demon. The saw is an ambiguous object—like the cauldron, it is an object of daily life, shown worked by two carpenters on a bas-de-page from the Smithfield Decretals executed around the 1340s (Fig. 7).[23] Yet, the crosscut saw is also found in more sinister contexts, like as a torture device in the martyrdom scene of Saint Quiricus depicted on an altar frontal from Sant Quircus de Durro (Fig. 8). The altar frontal, a near-contemporary of the Chaldon painting, also shows a cauldron as an instrument of torture, like the hell scene at Chaldon.

Fig. 7. Page from the Smithfield Decretals with bas-de-page image showing two workers utilizing a cross-cut saw. (BL Royal 10 E IV, f. 99v), c. 1340s, © British Library Board.

Fig. 8. Altar frontal depicting the martyrdom of Saint Quiricus, Durro, mid 12th century, now Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (photo: author).

Fig. 9. Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil, Chaldon (Photo: Poliphilo, CC0).

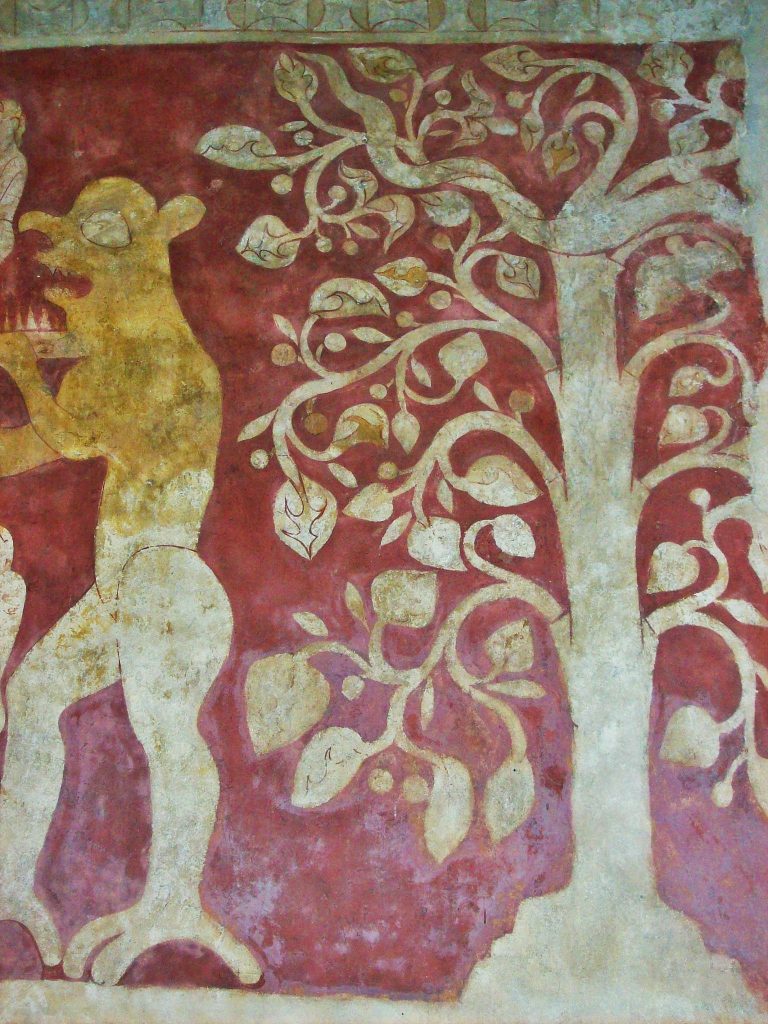

If the cauldron and the sawblade bridge are the main scenes in the bottom register, they are surrounded by numerous smaller vignettes representing a diverse range of torments. On the far right of the composition, a stylized leafy fruit tree flourishes, despite the heat of the nearby fire (Fig. 9).[24] This is the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil: a serpent winds through its upper branches, with his head facing to the north, his face now lost.[25] In contemporary representations of Adam and Eve in the garden, like in the Plaincourault Chapel, Meringy (Indre, France) from the twelfth century, the serpent also faces to the right, towards Eve (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Plaincourant Chapel, Merigny, Indre, France, tree of knowledge with Adam and Eve, (photo: Aranthama, via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Fig. 11. Harrowing of Hell and upper ladder, Chaldon (photo: Andy Scott, CC BY-SA 4.0).

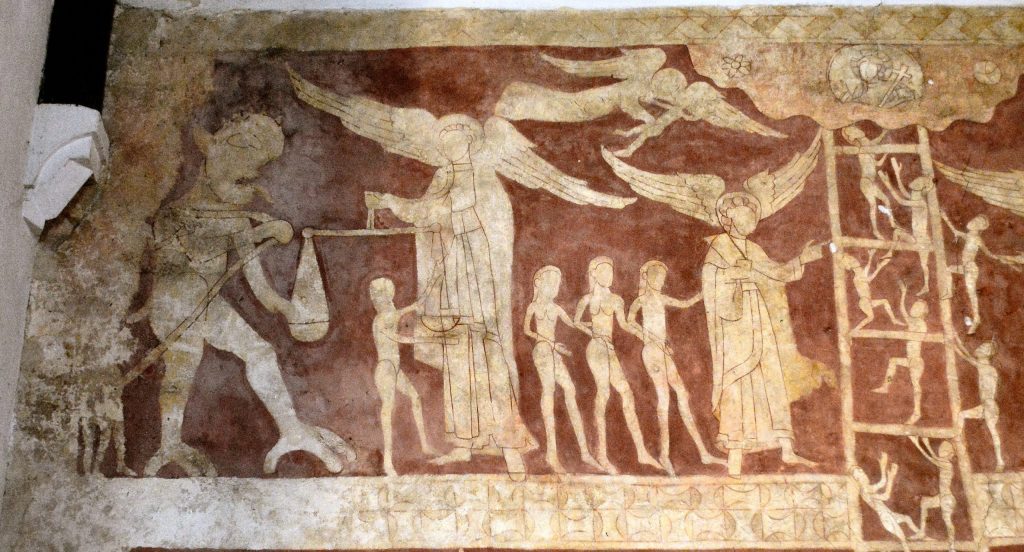

Interestingly, though, Adam and Eve are not present with the tree in the lower register of the Chaldon painting; however their presence is implied among the souls directly above the Tree, on the top register in the Harrowing of Hell (Fig. 11). There Christ stands on the legs of a recumbent demon with bound hands and sticks his staff into his mouth. Small naked souls, Adam and Eve typically among the first, with their hands raised, face towards Christ for salvation. Christ descends into the underworld in the days between his death and resurrection to rescue souls trapped there. At the left, St. Michael weighs souls, interrupted by a meddling, claw-footed demon who cheats the scales by adding weight with his hand (Fig. 12). Moving to the right, two standing angels surround the central ladder. While the lower register represents hell, the upper register doesn’t unambiguously represent heaven. Instead, the scenes here reflect the deciding moments between the two: when the soul is weighed, and when souls are pulled out of hell.

Fig. 12. Weighing of souls, Chaldon (photo: Andy Scott, CC BY-SA 4.0).

Fig. 13. Ladder detail, Chaldon (photo: Mattana, via Wikimedia Commons, public domain).

The ladder is both the formal and functional center of the image (Fig. 13). It is the most unusual element of the iconography depicted at Chaldon, and forms the visual link between each of the zones—including the nimbed Christ, who is the goal that the climbers aim to reach. The ladder itself is proportionally large, and the distance between each rung seems monumental given the size of the souls climbing it. The closer the climbers are to reaching Christ, the more capable they appear—the ones at the top of the ladder stand erect and seem to both pull themselves up and also reach for their salvation. They are more evenly spaced, and there are fewer of them. Alternatively, the souls in the bottom half of the ladder clumsily fall, some of them toppling headlong to the ground to be tormented in hell or perhaps begin their journey again.

Fig. 14. St. Thomas, Salisbury (Wiltshire), Doom painting over chancel arch (photo: Richard Avery CC BY-SA 4.0).

Fig. 14a. St. Thomas, Salisbury (Wiltshire), Doom painting over chancel arch, detail (photo: Benjamin Smith CC BY-SA 4.0).

This mural has often been included within the category of Last Judgement, or Doom, paintings. There is no rigid typology of Doom paintings before the fourteenth century when Roger Rosewell notes that they “had evolved into an increasingly predictable two-tier scheme, usually painted on the east nave wall above the chancel arch.”[26] In the Doom painting at the parish church of St. Thomas in Salisbury, Christ sits in judgment over the chancel arch, wounds still bloody, surrounded by angels holding the instruments of his Passion and framed by the Virgin and John the Evangelist (Fig. 14, 14a). Beneath him the twelve apostles are seated. On the spandrels, we see the dead rising out of the tombs. On the north side, angels guide them into heaven, depicted as a contemporary castle. On the south, however, the damned are processed into the mouth of hell. Prior to the somewhat conventional Doom representations of the later Middle Ages, in the twelfth century, there is no one way to represent the end of days. Examples of this variety include perhaps the earliest one, from Houghton-on-the-Hill where a trumpeting angel summons the dead for judgment, and the equestrian Devil at Clayton (West Sussex) drags one of the damned by the hair. Although some of the typical acts of judgment take place in Chaldon’s painting, such as the weighing of souls, it is not the final judgment with Christ arbitrating on his heavenly throne. Instead, the central zone is occupied by the ladder, which souls climb. Christ waits in his heavenly cloud for them but does not appear to be judging—instead, the ladder is a trial by ordeal, where the souls are forced to participate in a dangerous test to judge their spirit.[27] The souls that pass the test manage to climb the ladder, and are rewarded by being welcomed into heaven. The souls appear to have more agency on this ladder than they are typically afforded in a Doom.

Within a broader context, most of the iconography found throughout the mural is found elsewhere. Tristram has explained these smaller vignettes that surround the two main scenes on the bottom register as illustrations of the Seven Deadly Sins—another impulse towards typology which the Chaldon painting resists.[28] The Seven Deadly Sins are often depicted in English medieval wall paintings, and it is logical to suggest that they are present here since there are seven small compositions.[29] However, it is worth querying this suggestion. Most surviving examples of the Seven Deadly Sins in wall paintings are from considerably later than the Chaldon mural, in the fourteenth or fifteenth century. While the Seven Deadly Sins are described by Gregory the Great in his sixth-century Moralia in Job,[30] it wasn’t until the thirteenth century that the Church began to be concerned with ensuring that parishioners knew them so that they were prepared for the sacrament of confession, which was established as a requisite annual practice in the canons of Lateran IV.[31] Venial sins could be forgiven without confession, but the so-called deadly sins needed to be confessed to the parish priest; the location of murals featuring these sins on the walls of parish churches thus serves as a reminder both not to sin, but also what to confess when sin had been committed. Perhaps if the painter or iconographer behind the Chaldon mural was learned, as many commentators have suggested, he would have been familiar with the Seven Deadly Sins. However, it is very unlikely that he would have been prepared to depict them visually. Instead, what seems more plausible is that the painter depicted a variety of torments in the available space, which coincidentally number seven.

Fig. 15. Font, Eardisley (Herefordshire) (photo: Ron Baxter/CRSBI).

Fig. 16. Tiberius Psalter, British Library Cotton MS Tiberius C VI (Photo: Wikimedia, Public Domain).

Fig. 17. Winchester Psalter, Cotton Nero C. IV, f.39 (Photo: British Library, Wikimedia, CC0).

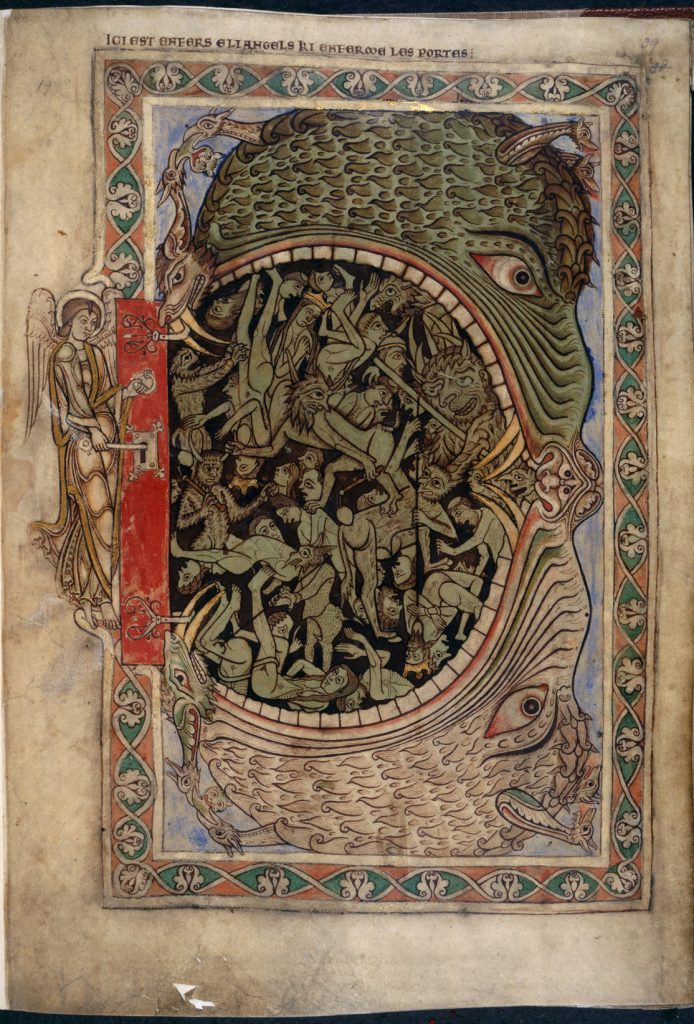

It is not surprising to find a Harrowing of Hell image at Chaldon; in England, the Harrowing of Hell was known from early medieval poetry and sermons.[32] At Chaldon, a standing Christ is shown plunging his staff into the mouth of the recumbent demon to induce vomit to release souls. Perhaps most the most well-known Harrowing was carved on the Lincoln west front frieze, where the massive, yawping mouth of Hell is laid on its side, from which Christ pulls souls. The Harrowing was a subject on baptismal fonts, like at Eardisley (Fig. 15). Baptism offers salvation—a means to escape hell—like the Harrowing. On the Eardisley font, Christ rescues one figure, identified as Adam, to stand in perhaps for a larger group. No hell mouth or devil is present, but swirling lines, then a lion-like creature, follow Adam, the demon apparently swapped for another fearsome beast. Eleventh and twelfth century manuscript illuminations like in the Tiberius and Winchester Psalters make creative use of the demon’s mouth as the frightening entrance to hell (Figs. 16 and 17). As the Winchester Psalter shows, the first two people taken from hell in most examples of this iconography are Adam and Eve. Given the location of the Chaldon Harrowing, just above the serpent in a tree, the implication is that Adam and Eve were once there, but have progressed in God’s timeline. More like the Chaldon depiction, and closer in terms of the parochial context, is the north doorway tympanum at Quenington, where the entire body of the demon is shown (Fig. 18). The presence of the Harrowing on a tympanum, particularly the north, more sinister side, seems to take on a kind of prophylactic quality for those entering the church.

Fig. 18 Tympanum, Quenington (Gloucestershire), (photo: Jean and Garry Gardiner/CRSBI).

The Ladder

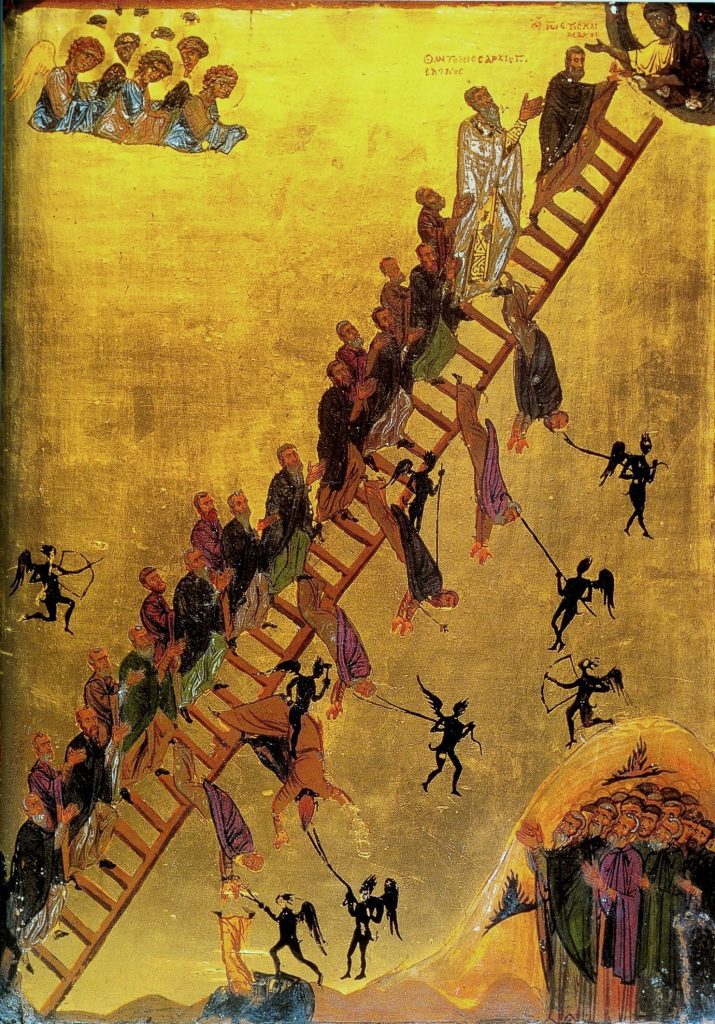

The most unusual part of the composition at Chaldon is the ladder.[33] There is a striking formal resonance between the Chaldon west wall painting and Byzantine representations of the Ladder of John Climacus, iconography that draws from the writings of the abbot of St. Catherine, Mount Sinai, in the first half of the seventh century (Fig. 19). John Climacus’ text describes a monk’s struggles with achieving virtue in the face of vices.[34] The ladder is the metaphor used throughout: each rung of the ladder is a step in achieving spiritual perfection. Climacus teaches that a monk must practice abstinence and be an “abyss of humility in which every evil spirit has been plunged and smothered.”[35]

Fig. 19. Ladder of Divine Ascent, Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai (photo: Pvasiliadis, Wikimedia, public domain).

Representations of the Ladder appear most frequently in manuscripts and only occasionally in monumental contexts. The best-known example of the Ladder of John Climacus is on a twelfth-century tempera panel with gold ground located at the Holy Monastery of Saint Catherine where Climacus was abbot. The panel is divided diagonally by a ladder, which reaches from the bottom left of the panel to the top right, where Christ is found bust-length, with arms outstretched, welcoming the monks at the top. The ladder is formed of precisely 30 steps, as prescribed in Climacus’ treatise. Bearded, robed monks climb the ladder as though it were steps, each with hands raised. A haloed choir of angels float in the upper left, looking down at the scene. The angels, wearing blue, pink, and green garments contrast with the winged demons shown in shadowy silhouettes, pulling monks head first off the ladder with chains to hell.

Climacus’ Ladder, is likely derived from Jacob’s Ladder: the ladder from Jacob’s dream in Genesis 28 that connects heaven and earth.[36] Examples of Byzantine-inspired iconography and style were found in twelfth century England, by the time the Chaldon painting was executed.[37] However, given the contextual differences between the monastic context of the Byzantine images and their textual tradition, versus the unusual iconography at Chaldon, a rural parish church, it seems unlikely that the visual similarities are any more than a coincidence.

Fig. 20. Jacob’s Ladder. Douai, Bibliothèque Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, 490 x 320 mm, 372-1, twelfth century, f. 100. Photo credit: IRHT-CNRS.

What is most likely is that Jacob’s Ladder was an available iconographic trope in both contexts. Like John Climacus, the designer of the Chaldon mural may have been thinking about Jacob’s Ladder—perhaps images as early as the fourth century wall painting from the Via Latina Catacomb.[38] In the case of Chaldon, a closer comparison might be something like an Old English Hexateuch depicting Jacob’s Ladder, or a French manuscript containing the writings of St. Bernard which depicts the Jacob’s ladder vision with angels both ascending and descending (Fig. 20).[39] However, while there are significant differences between the Chaldon painting and John Climacus’ ladder, Climacus’ ladder represents personal steps for individual monks, whereas the Chaldon painting is simply a means for its climbers to change spatial location, going from A to B. The monastic ladder exists in earthly time, helping the monks to achieve spiritual perfection in life; the Chaldon ladder helps remediate a bad situation only in death.

Unlike John Climacus’ ladder, the ladder in the Chaldon painting is, as Tristram has noted, “a graphic exposition on the doctrine of Purgatory.”[40] This precocious, experimental depiction of purgatory uses sources already available in England, as well as iconographic creativity, to achieve a new iconography to represent something that hadn’t previously needed representing. Even in Paris, a major center for clerical learning and debate, the addition of lateral chapels at the cathedral for the multiplication of altars did not begin until the late 1220s.[41] How exactly ideas about purgatory made it to English village churches in the last decades of the twelfth century cannot be certain, but it is likely that pastoralia, manuals written by bishops, archdeacons, and other members of the church hierarchy for parish priests, played a role.[42] These manuals were one of the means by which the church sought to remedy the isolation and lack of education for parish priests who were administering pastoral care in village parish churches. Although in 1179 at the time of the Third Lateran Council there were hardly any pastoral manuals available, by the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), there were about a dozen, making their emergence contemporary with the Chaldon mural. While we must assume that parish priests were introducing new ideas about the afterlife to their congregants, the true triumph of the doctrine of purgatory, according to Le Goff, was not with clerics, but with the populace.”[43] Just as the solidification of the doctrine of purgatory changed the imagined landscape of the next world, the spread in beliefs about the afterlife affected life on earth.

Unlike hell, purgatory is not often represented graphically until the later Middle Ages. A search in the Index of Medieval Art finds only 45 images for the term “purgatory,” virtually all of them from the fourteenth century and after, illustrating Dante’s Divine Comedy. For comparison, a search in the Index for hell produces 995 results.[44] Binski has explained the problem, writing: “how… was purgatory to be distanced usefully from the opposition of Heaven and Hell, such that its representation as part of the incentive system of medieval images could be plain and unambiguous?”[45] With this difficulty in mind, Binski describes the Chaldon painting as illustrative of “the spatial incoherence which arose from the synthesis of these diverse and basically independent metaphors which implied no overall spatial or topographical context.”[46] Robert Mills argues that topography of Purgatory is made more clear in this image as it “ties in with the notion of Purgatory as an upper region of Hell in otherworldly texts such as the Visions of Tondal. The ladder has its base in Hell, and passes through Purgatory before reaching Heaven.”[47] In the sixteenth century, Hieronymous Bosch often uses a ladder motif in hell, rather than in between zones; as Lynn Jacobs has argued, Bosch’s ladder is used as a mode of further descent, rather than the spiritual ascent that seems to be offered to the parishioners at Chaldon.[48]

The Architectural Context

The doctrine of purgatory was formalized in Catholic doctrine rather late, in 1274, yet here it is on the western wall of a rural parish church in Surrey, the better part of a century earlier. This testimony to the laity’s early enthusiasm for purgatorial theology is echoed by Chaldon’s architecture. The painting is seldom illustrated in such a way that reveals its architectural context. Beyond that, architecture and the graphic arts are often considered independently of one another, yet much can be learned by assessing them in tandem.[49]

Fig. 21. Chaldon west wall, context with lancet window (photo: Mattana via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0).

At Chaldon, there is a narrow lancet window situated directly above the head of Christ, lighting up the heavenly part of the composition, and leaving hell in relative darkness (Fig. 21). With the sun rising in the west, the effect in the morning would be brilliant. While no medieval glass survives in the lancet, it must have had special glazing to highlight the scene below. The painting also formed a backdrop to the ritual of baptism; while Chaldon does not retain its medieval font, it was likely located on axis with the south door of the church, close to the western wall.[50] The subject of the mural is resonant with baptism, which is often equated with a spiritual death and rebirth.

Fig. 22. Chaldon south aisle respond (photo: author).

The Chaldon painting is located on the western wall of the church nestled between two aisle responds (Fig. 22). The fact that the painting sits comfortably between the responds without any part of the composition interrupted by the introduction of aisles, suggests that it was painted shortly after the addition of the aisles, or once the addition of the aisles was planned. Apparently the mural’s composition may have continued onto the responds, as a figure of a demon on the north respond was apparently noticed, but destroyed, in the nineteenth century.[51] It is not coincidental that the aisle and painting are contemporary; aisles proliferated in parish churches during this era precisely because of a growing belief in purgation, which led to increased demand for chantry masses.[52] The previous iteration of the church, composed of just nave and chancel, would have been insufficient to meet this new spiritual need of extra masses, which required extra altars. A simple piscina (a mural niche that drained below the church on consecrated ground for the decorous cleaning of the eucharistic vessels) has been added to the east end of the north aisle. The presence of a piscina for the decorous disposal of sacred ablutions, proves that there was an altar here. Chantry masses, held in honor of a dead parishioner, would have been said at this altar. These masses were thought to be the most efficacious way to expiate sin and reduce time spent in the purgatorial fires. An individual could arrange for such masses to be held after his or her own death, in order to hasten the ascent of their soul to heaven. It is because of the growing belief in purgatory, systematically depicted on the west wall, that the aisle finds its place in the architecture of the parish church.

Fig. 23. St. Michael on Wyre, exterior south aisle window (photo: author).

In many cases, aisles were introduced to naves in the second half of the twelfth or beginning of the thirteenth century and then further expanded later in the Middle Ages to increase space and light in the church. For example, at St. Michael on Wyre (Lancashire), a lancet window survives from the first, narrow aisle has been filled in to make way for a wider aisle space and larger window in the sixteenth century (Fig. 23).[53] Like Chaldon, Crundale (Kent) survives with its early, narrow aisles, not replaced with a larger aisle in the later Middle Ages like St. Michael on Wyre.[54] Crundale was initially composed of two cells, likely from the eleventh or early twelfth century based on the surviving window high on the north nave wall whose functionality was curtailed by the added aisle.[55] Sometime later in the twelfth century, an aisle was added to the north side (Fig. 24). The foundation date for the church is unknown, but it was given to Christ Church Priory, Canterbury around 1150, according to a confirmation of a gift from Eustace of Mustrel by Archbishop Theobald.[56] It is consistent with the fabric of the church that at least the chancel and nave were standing around 1150 when the church was offered to the monks at Canterbury, but we cannot be certain of whether its north aisle had yet been built by that time. The Crundale north aisle is unusually narrow by the average standards of parish churches: it is less than two meters wide, approximately a third of the width of the nave.[57] Not only is it tiny, but its arcade was constructed by excavating the existing wall, rather than knocking out the wall and erecting new columns. This was the simplest way of adding an aisle to a church; space is gained, but parishioners were spared the endlessly boarded-up church during construction, as the exterior aisle wall was probably constructed before anything was removed (Fig. 25).[58] The roofline was not altered in response to the addition of the aisle, so the single gable causes the ceiling to be very low.[59]

Fig. 24. Crundale nave and north aisle (photo: author).

Fig. 25. Crundale north nave aisle exterior (photo: author).

Unlike Crundale, at Chaldon the decision was made to remove the north and south walls to add an aisle via arcades. This lends more visibility than the Crundale method, but like at Crundale, the aisles are slim: the south aisle is 1.99m wide, and the north is 1.94m.[60] Like at Crundale, the Chaldon roof gable of the central vessel is extended to cover the aisle. We are fortunate that the church remains largely as it was when the painting was executed, because in many places, later medieval wealth and the increased provision of chantry masses and chapels, among other factors, caused churches to be dramatically enlarged and changed. At Chaldon we can envision the setting for contemporary users.

Lay people were meant to attend church at least weekly, plus on numerous other feast days. Even with a very conservative estimate, most Chaldon villagers saw the west wall mural more than fifty times per year. Over the course of a lifetime, this could amount to hundreds or even thousands of views. The Chaldon mural is on the west wall of the nave, which means that it was not viewed during the mass itself, when parishioners would be expected to face the chancel to view the elevation of the host. Most parishioners would view the mural, instead, when they turned towards the west to walk out of the church through the south door. The location on the west wall means that the mural is the last thing seen by parishioners after mass, as if to punctuate the ritual they had just participated in and witnessed. While Christ’s death was reenacted with the consecration of the Host on the altar, behind the parishioners, he waited in eternal life as souls reached him in heaven. Might parishioners have reflected on their memory of the scene behind them while looking into the chancel? Perhaps. But what is most potent about this image’s placement is that it is not visible to congregants during the duration of the mass but becomes visible as they leave the church in a shorter, more intense period, rather than a Doom which amplifies the sense and setting of the mass at the moment it occurs, the Chaldon mural provides a lasting impression as the body of the viewer leaves the building, lingering in their attention.[61] The location on the west wall means that the mural is the last thing seen by parishioners after mass, as if to punctuate the ritual they had just participated in and witnessed. If the contemporary experience of leaving church tells us anything about the Middle Ages, the mural may have formed the backdrop to lingering chats with friends and neighbors.

Durational looking at this painting throughout the lifecycle of a parishioner would see the meaning change, shift, and develop for its receivers. While a child might fear the demons and their torments, an adult parishioner might benefit from the reminder to prepare him or herself to prepare for the future—a timescale that, as the Chaldon painter reminds the medieval parishioners, was not limited by the mortal lifespan. As Athene Reiss has argued, English medieval wall paintings should not be thought of as mere “books for the illiterate,” but as presenting a more diverse and complicated multiplicity of messages.[62] In the case of Chaldon, this may have included instruction on the abstract and nascent doctrine of purgatory. This messaging reminded viewers in their adulthood and old age to prepare for the world to come, which may have included seeking indulgences, planning for chantry masses, and confessing their sins. As the parishioner draws closer to death, he or she might take solace in the purgatorial ladder and the agency implied by it—the knowledge the stairway to heaven is a difficult, but not impossible, climb, particularly when supported by familial and social networks within the parish who were also bringing their attention to bear on the scene. In acknowledging the contemporary hypersaturation of image sensitivity in our own lives and engagement with Chaldon, and the significance of durational looking across the lifetime of its parishioners in its own time, which establishes an elongated process of slow looking for the parishioners individually and communally, we see that time, awareness, proximity and attention all amplify the already potent eschatological meaning of the mural.

Fig. 26. Chaldon consecration cross detail (photo: Michael Garlick, CC BY-SA 2.0).

A final element of the west wall composition merits attention here. Located off center to the south, under the caldron composition, it is a circle filled with an internal stylized cross motif created with a compass (Fig. 26). There was likely a second cross underneath the saw-bridge scene, and traces of a third, a simpler Latin cross, survive on the south arcade.[63] These are only a fraction of twelve that would have been inscribed on the church at its consecration. The consecration is a ritual where in the church was anointed with holy oil, first inside, and then outside.[64] By the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, consecrating churches was a solemn duty of the bishops, but complaints reveal that they often shirked this responsibility and needed to be chided for it.[65] Churches often had to wait two years or more to be consecrated.[66] According to the pontifical of David de Bernham, Bishop of St. Andrews, churches are responsible for having twelve crosses painted on the outer walls and twelve on the inner walls, ready to be consecrated by the bishop.[67] A pontifical from Coventry notes that the same words of consecration need to be said at each of the twenty-four crosses—a potentially tedious task that might offer a partial explanation for why bishops were so loath to perform this duty.[68]

At Chaldon, the surviving cross on the west wall is integrated with the whole composition. If this is contemporary with the mural, it reveals that the same painter or painters who limned the back wall mural painted this, and presumably the eleven other consecration crosses as well. Alternatively, an existing, simpler cross could have been expanded here later to integrate with the mural. As it presently exists, this consecration cross forges a link between God’s time on the back wall and earthly time in the parish, where the consecration ceremony took place in the here and now. In the case of Chaldon, the bishop may not have needed help reaching the consecration crosses, but in the depictions of consecration ceremonies—mostly from the sixteenth century—the bishops are shown climbing ladders.[69] It is perhaps a leap to make, but compelling nonetheless, to imagine the ladder placed between the two crosses on the back wall, so the bishop could consecrate both—his earthly ladder would adjoin with the purgatorial one depicted on the wall, forging a link between earthly time and the difficult climb to heaven depicted in the painting. The mural, during this rite, would be enlivened—animated by the bishop enacting the climb, hopefully assisted by angels, not falling to the floor the church!

Fig. 27. Chaldon Church Underground Electric Railways Company of London Poster, by Frederick Charles Herrick, 1931. © TfL from the London Transport Museum collection, https://ltmuseum.co.uk/.

The discovery of the painting at Chaldon was reported in newspapers, and it was a significant enough draw to inspire an Underground Electric Railways Company of London poster to be commissioned in 1931 (Fig. 27).[70] The poster, designed by prolific artist Frederick Charles Herrick, depicts the west wall of Chaldon church, focusing on the mural. In the foreground, two male figures stand—the one on the left holds his head back, revealing his monastic tonsure. His brushes and charmingly anachronistic painter’s palette communicate that he is the artist that has just completed the mural. The second figure, a taller, bearded man wearing a black coat, is more ambiguous. This second man appears to be a contemporary of the poster’s date and the General Bus advertised on it. Suspended in time together on the poster, the past and present meet, joined with the purgatorial image of the wall painting, at the end of, or out of, time. The idea of Londoners making a pilgrimage to the church via the 59 bus to view the mural suggests that it is a sufficiently tantalizing image capable of drawing attention—across (and perhaps bridging) historical eras.

While we cannot know the first viewers of this image or be certain of the identity of the painter (perhaps not the tonsured monk of Herrick’s imagination), it is possible to imagine the original viewers of the ladder reacting to the image, which revealed horrors, but also offered hope via their own agency through the concept of purgatory. This painting was executed at the same historical moment in which parishioners were gaining responsibility for the upkeep of the church nave and taking that responsibility with not trepidation but enthusiasm.[71] They inscribed their desires, fears, and concerns upon their churches, and they were developing new strategies for developing community identity. While the names of the parishioners who planned or paid for this image are not known to us, we know that the agency to travel heavenwards felt more and more in their grasp. For generations after it was originally painted on the west wall of the church, community members left Mass under the purgatorial ladder, which prefigured at least part of the eternal life that they anticipated. Perhaps it was the messaging of this painting, the final image seen while exiting through the south door—rather than the Mass performed by a priest in tones of muttered Latin away from the faithful—that impelled these lay people in their actions throughout the week and throughout the seasons of their lives. This message, even with the horrors and indignities depicted, can still be read as largely positive, particularly for lay people. While angels provide some assistance and Christ compels the souls towards heaven, the Chaldon mural shows that the souls on the ladder are getting to heaven by their own steam, actively climbing rather than awaiting a passive judgement. By including this mural on the church wall, the parishioners of Chaldon helped to locate themselves in both early and heavenly time and understand their relationship to the space and time of purgatory.

References

| ↑1 | J.G. Waller, “On Recent Discoveries of Wall-Paintings at Chaldon, Surrey; Wisborough Green, Sussex; and South Leigh, Oxfordshire,” Archaeological Journal (London) 30, no. 1 (1873): 35–58; John Green Waller, On a Painting Discovered in Chaldon Church, Surrey, 1870 (London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1885); George C. Druce, “Some Minor Features of the Chaldon Painting,” Surrey Archaeological Collections 23 (1910): 1–29; E. W. Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Twelfth Century (New York: New York, 1944), 36–39; T. S. R. Boase, Death in the Middle Ages: Mortality, Judgment and Remembrance (London: Thames & Hudson, 1971), 49; K. N. F. Flynn, “The Mural Painting in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Chaldon, Surrey,” Surrey Archaeological Collections 72 (1980): 127–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1873.10851587; Robert Mills, “The Art of Medieval Purgatory: Issues of Non-Representation” (M. A., University of Manchester, 1996), 28–29; Christian Heck, L’Échelle Céleste: Une Histoire de La Quête Du Ciel (Paris: Flammarion, 1997), 137–40. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The literature on the Conques tympanum is vast; much of it is catalogued by Kirk Ambrose in “Attunement to the Damned of the Conques Tympanum,” Gesta 50, no. 1 (2011): 1, fn. 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/41550546. |

| ↑3 | Catechetical Lectures 23:5:9 (A.D. 350). https://www.churchfathers.org/purgatory. |

| ↑4 | Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory (Aldershot: Scolar, 1991); While Le Goff’s book remains the classic text on the development of purgatory, the question of purgatory’s birth in late antiquity and the early Middle Ages has been taken up more recently. See for example: Isabel Moreira, Heaven’s Purge: Purgatory in Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 2010); Helen Foxhall Forbes, “The Theology of the Afterlife in the Early Middle Ages, c. 400–c. 1100,” in Imagining the Medieval Afterlife, ed. Richard Matthew Pollard, Cambridge Studies in Medieval Literature (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 153–75. In spite of the heightened scholarly awareness of purgatory’s earlier intellectual context, as far as the Church, and the mainstream Christian were concerned, the thirteenth century remains the time when purgatory was most solidified and became popular. |

| ↑5 | Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, 233. |

| ↑6 | Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, 154–55. |

| ↑7 | Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, 289. |

| ↑8 | An exception is in Italy, where Dante’s Divine Comedy inspired some visual representations of purgatory—albeit in a predominantly literary context. T. S. R. Boase, Death in the Middle Ages: Mortality, Judgment and Remembrance (London: Thames & Hudson, n.d.), 49; Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (London: The British Museum Press, 1996), 193–98. |

| ↑9 | Robert Mills, “God’s Time? Purgatory and Temporality in Late Medieval Art,” in Time and Eternity: The Medieval Discourse, ed. Jaritz, Gerhard and Gerson Moreno-Riaño (Turnhout: Brepols, 2003), 486–87. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.IMR-EB.3.684. |

| ↑10 | In the Middle Ages, Chaldon was formed of only nave and chancel, with no tower. |

| ↑11 | “Parishes: Chaldon | British History Online,” accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/surrey/vol4/pp188-194. |

| ↑12 | “Parishes: Chaldon | British History Online,” accessed March 29, 2025, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/surrey/vol4/pp188-194. |

| ↑13 | Roger Rosewell, Medieval Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008); Victoria George, Whitewash and the New Aesthetic of the Protestant Reformation (Pindar Press, 2013), 151. |

| ↑14 | Flynn, “The Mural Painting in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Chaldon, Surrey,” 153. |

| ↑15 | J.G. Waller, “On Recent Discoveries of Wall-Paintings at Chaldon, Surrey; Wisborough Green, Sussex; and South Leigh, Oxfordshire,” Archaeological Journal (London) 30, no. 1 (1873): 35–58; John Green Waller, On a Painting Discovered in Chaldon Church, Surrey, 1870 (London: Mitchell and Hughes, 1885); Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting; Flynn pushes against the purgatorial connection at Chaldon accepted by Tristram and many later authors. K. N. F. Flynn, “The Mural Painting in the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Chaldon, Surrey,” Surrey Archaeological Collections 72 (1980): 127–56. |

| ↑16 | There are other surviving wall paintings in the Southeast from the twelfth century, including Witley in Surrey, and the so-called ‘Lewes group’ composed of Clayton, Coombes, Hardham, Plumton, and Westmaston in Sussex, thought to have been executed by a traveling group of painters perhaps associated with the Cluniac priory at Lewes nearby. Chaldon’s mural doesn’t seem to fit in stylistically with any of the other examples in the region, but the issue of survival is likely to play a role here. |

| ↑17 | Waller, On a Painting Discovered in Chaldon Church, Surrey, 1870, 6. |

| ↑18 | Wehlte, “Chaldon, Surrey,” trans. R. Straub, July 19, 1954. |

| ↑19 | Wolfgang Gärtner, “S. Peter and S. Paul, Chaldon, Surrey. Report on the Restoration of the Wallpainting: ‘The Ladder of the Salvation of the Human Soul, and the Road to Heaven’” (Canterbury: Canterbury Cathedral Wallpaintings Workshop, August 1989), 1-3. |

| ↑20 | Gärtner, “S. Peter and S. Paul, Chaldon,” 2. |

| ↑21 | Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting, 82. |

| ↑22 | Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting, 37. |

| ↑23 | BL Royal 10 E IV, f. 99v. |

| ↑24 | On trees in Romanesque iconography, and in particular the fruited nature of the Tree of Knowledge, see: Ute Dercks, “Two Trees in Paradise? A Case Study on the Iconography of the Tree of Knowledge and the Tree of Life in Italian Romanesque Sculpture,” in The Tree: Symbol, Allegory, and Mnemonic Device in Medieval Art and Thought, ed. Pippa Salonius and Andrea Worm (Turhout: Brepols, 2014), 145. |

| ↑25 | Jennifer O’Reilly, Studies in the Iconography of the Virtues and Vices in the Middle Ages (New York: Garland Publishers, 1988), 349. |

| ↑26 | Rosewell, Medieval Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches, 73–74. |

| ↑27 | On the medieval practice of trial by ordeal, see Robert Bartlett, Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal (Clarendon Press, 1988). |

| ↑28 | E. W. Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting: The Twelfth Century (New York: New York, 1944), 37–38. |

| ↑29 | Roger Rosewell, Medieval Wall Paintings in English and Welsh Churches (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2008), 85. |

| ↑30 | Morton W. Bloomfield, The Seven Deadly Sins; an Introduction to the History of a Religious Concept, with Special Reference to Medieval English Literature, Michigan (East Lansing: Michigan State College Press, 1952), 72. |

| ↑31 | Bloomfield, The Seven Deadly Sins, passim, esp. 97–104. |

| ↑32 | The Harrowing of Hell is a common scene in Romanesque painting and sculpture in England. On the history of the Harrowing of Hell, first described as such in the 10th century by Ælfric, see: Karl Tamburr, The Harrowing of Hell in Medieval England (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2007). |

| ↑33 | For a full exposition of the ladder in medieval art, including a recounting of the major literature on Chaldon, see Christian Heck, L’Échelle Céleste: Une Histoire de La Quête Du Ciel (Paris: Flammarion, 1997), 137–39 and passim. |

| ↑34 | Charles Barber, Contesting the Logic of Painting: Art and Understanding in Eleventh-Century Byzantium (Brill, 2007), 43–44. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004162716.i-206. |

| ↑35 | Robert S. Nelson and Kristen M. Collins, Holy Image and Hallowed Ground: Icons from Sinai (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2006), 243. |

| ↑36 | Milada Studničková, “Karlstein Castle as a Theological Metaphor,” in Prague and Bohemia: Medieval Art, Architecture, and Cultural Exchange in Central Europe, ed. Zoë Opačić, The British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions 32, 2009, 174; Lynn F. Jacobs, “Climbing the Ladder: Hieronymus Bosch and the Vision of Hell,” The Sixteenth Century Journal 52, no. 2 (2021): 342. https://doi.org/10.1086/SCJ5202003. |

| ↑37 | Cecily Hennessey, “Winchester’s Holy Sepulchre Chapel and Byzantium: Iconographic Transregionalism?,” in The Regional and Transregional in Romanesque Europe (Routledge, 2022), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003162827-8. |

| ↑38 | On the impact of Jacob’s Ladder on religious texts, see: Jacobs, “Climbing the Ladder: Hieronymus Bosch and the Vision of Hell,” 341–42. |

| ↑39 | Cotton MS Claudius B IV (Old English Hexateuch), f. 43v; Douai, Bibliothèque Municipale, Ms. 372, I, fol. 100. |

| ↑40 | Tristram, English Medieval Wall Painting, 37. |

| ↑41 | Mailan S. Doquang, “The Lateral Chapels of Notre-Dame in Context,” Gesta 50, no. 2 (2011): 138. https://doi.org/10.2307/41550554. |

| ↑42 | Boyle, “The Inter-Conciliar Period 1179-1215 and the Beginnings of Pastoral Manuals”; William Hopkins Campbell, “‘Dyvers Kyndes of Religion in Sondry Partes of the Ilande’: The Geography of Pastoral Care in Thirteenth-Century England” (University of St Andrews, 2007), 34–34. |

| ↑43 | Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, 289. |

| ↑44 | “Index of Medieval Art, Princeton University,” accessed September 26, 2024, https://theindex.princeton.edu/. |

| ↑45 | Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation, 196. |

| ↑46 | Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation, 198. |

| ↑47 | Robert Mills, “The Art of Medieval Purgatory: Issues of Non-Representation” (M. A., University of Manchester, 1996), 28. |

| ↑48 | Jacobs, “Climbing the Ladder: Hieronymus Bosch and the Vision of Hell,” 360 and passim. |

| ↑49 | Virginia Chieffo Raguin, Kathryn Brush, and Peter Draper, eds., Artistic Integration in Gothic Buildings (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995), passim. |

| ↑50 | On all possible positions for the font, see J.G. Davies, The Architectural Setting of Baptism (London: Barrie and Rockliff, 1962), 61–63. |

| ↑51 | “Parishes: Chaldon | British History Online”; Further reference to this is made in an author-unidentified document in the “The National Wall Paintings Survey at The Courtauld,” n.d. |

| ↑52 | Meg Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300” (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Los Angeles, University of California, Los Angeles, 2019); Meg Bernstein, “The Parochial Nave in 12th- and 13th-Century Cambridgeshire,” in Medieval Art, Architectural and Archaeology in Cambridge: College, Church and City, ed. Gabriel Byng and Helen Lunnon (Oxford: Routledge, 2022), 115–29. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003244981-6. |

| ↑53 | Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300,” 96. |

| ↑54 | For a brief history of Crundale, see: Mary Berg and Howard Jones, Norman Churches in the Canterbury Diocese (Stroud: The History Press, 2009), 160. |

| ↑55 | Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300,” 94–95. |

| ↑56 | Trans. Crosby: “Et nos consequenter eandem ecclesiam ecclesie Cantuariensis et monachis in cibum conventus ad propriam mensam eorum concedimus et eis in perpetual confirmamus possessionem salva dignitate archiepiscopali.” Everett U. Crosby, Bishop and Chapter in Twelfth-Century England: A Study of the “Mensa Episcopalis” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 18. |

| ↑57 | Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300,” 94–95. |

| ↑58 | Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300,” 94–95. |

| ↑59 | Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300,” 95. |

| ↑60 | Bernstein, “Civil Service: English Parochial Architecture, 1150-1300,” 95. |

| ↑61 | Recent research from MIT has shown that people can perceive images very quickly—it’s only when they are shown for less than 13 milliseconds that respondents were unable to identify what they had seen. I’d offer some caveats to applying this expectation to medieval people viewing the Chaldon mural. For one, the iconography is far more complex than the types of scenes being shown by the MIT researchers like “smiling couple” and “picnic.” Secondly, it is likely that our contemporary brains are more attuned to interpreting images quickly due to our repeated exposure to moving images. Still, the brevity with which the Chaldon viewers might have seen the mural was likely to be in the realm of seconds or even minutes as they departed from the church. “In the Blink of an Eye,” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, January 16, 2014, https://news.mit.edu/2014/in-the-blink-of-an-eye-0116. |

| ↑62 | Athene Reiss, “Beyond ‘Books for the Illiterate’: Understanding English Medieval Wall Paintings,” The British Art Journal 9, no. 1 (2008): passim and 12-13. |

| ↑63 | “Parishes: Chaldon | British History Online.” |

| ↑64 | Laura Varnam, The Church as Sacred Space in Middle English Literature and Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 41–44. https://doi.org/10.7228/manchester/9781784994174.001.0001. |

| ↑65 | E. S. Dewick, “Consecration Crosses and the Ritual Connected with Them,” The Archaeological Journal 65, no. 1 (1908): 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1908.10853073. |

| ↑66 | Dewick, “Consecration Crosses and the Ritual Connected with Them,” 6. |

| ↑67 | Alan Orr Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History AD 500 to 1286, vol. 2 (Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1922), 520–26; Dewick, “Consecration Crosses and the Ritual Connected with Them,” 7. |

| ↑68 | Dewick, “Consecration Crosses and the Ritual Connected with Them,” 7. |

| ↑69 | See the evangelium for Philippe de Villiers de L’Isle Adam (Grand Master of Malta), BL Add. MS 18143, fol. 55b, reproduced in Dewick, “Consecration Crosses and the Ritual Connected with Them.” |

| ↑70 | Two years after the poster was published, the UERL subsumed into the newly formed London Passenger Transport Board, which ultimately, after several shifts and rebrands, became Transport for London (TFL). |

| ↑71 | Carol Davidson Cragoe, “The Custom of the English Church: Parish Church Maintenance in England before 1300,” Journal of Medieval History 36, no. 1 (2010): 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmedhist.2009.11.001. |