Martha Easton • Saint Joseph’s University

Recommended citation: Martha Easton, “Castle Fever,” Different Visions: New Perspectives on Medieval Art 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.61302/IRVH9756.

When I was a kid, I was in love with castles, and so it was probably inevitable that I would become a medievalist. In fact, I spent quite a bit of time in two different castles in my youth. Those castles might have been built in the twentieth century, and in Massachusetts, but they both evoked a fantasy of the Middle Ages that made an enormous impression on me. Then in high school, I spent months making a mosaic of a castle for a high school English project. Finally, just before high school graduation, a friend gave me a work of historical fiction called Katherine; since it revolved around life at the fourteenth-century English court, there were many mentions of castles and castle life. Reading this book directly affected my course selection during my freshman year of college, and ultimately my subsequent academic path.

Elementary School in a Castle

Fig. 1. Bancroft Elementary School, Andover, MA. Opened 1969; demolished 2014. Photo courtesy of Andover Center for History and Culture.

I was part of the first cohort to attend Bancroft Elementary School in Andover, Massachusetts, newly constructed in 1968-69. Bancroft had Tudor-style half-timbering, towers, a moat complete with boats, as well as a wildly dangerous play structure that we called the fort. Upon entering the building, a drawbridge led into a soaring central space (used as both a media center and a place for all-school gatherings), ringed with balconies so that students could watch the activities below as if we were spectators at a joust. We loved our school and felt sorry for the students in the other elementary schools in town, trapped in rows of desks in traditional classrooms while we sat on carpeted floors in our open-plan “lofts.”

The architect was William D. Warner (1929-2012), an instructor at the Rhode Island School of Design who was interested in historic architecture.[1] In a review of Warner’s design for the Pierce School in Brookline, MA, similar in many respects to Bancroft, the architecture critic for The Boston Globe called it a “kind of inaccurate imitation of a Bavarian castle.” He noted in particular that the form of the school didn’t really follow its function, but conceded that “form also has all kinds of symbolic meanings for all kinds of people.”[2] For us students, our school was a magical building that evoked the past, while at the same time its unconventional appearance hinted at the grand educational experiment that was being conducted inside its walls.

Even in the 1970’s, an era of progressive education, Bancroft was radical. We worked on group projects, but we also learned math and reading at our own pace. Our 6th grade production of the musical 1776 featured gender-neutral casting (I played the part of John Dickinson). On at least two occasions that I remember, a small group of us received permission to leave the rest of the class in order to write and rehearse plays on the stage in the “cafetorium” (combination cafeteria and auditorium), which we ultimately performed for the rest of the school. Our teachers encouraged and trusted us to celebrate our own creativity and explore our own interests and strengths, with activities that were the very definition of experiential learning.

Fig. 2: Bancroft Elementary School, Andover, MA. Opened 1969; demolished 2014. Photo courtesy of Andover Center for History and Culture.

Sadly, while my beloved castle-school was beautiful in its form, it didn’t function particularly well and had structural problems almost from the beginning. It was torn down in 2014, and replaced with a building that looks nice enough, and is probably much more functional, but is clearly missing the scope for imagination inherent in the design of the original. I doubt Bancroft students today pretend that they are knights occupying the fort on the playground, or princesses crossing the drawbridge and hanging over the balconies. I’m glad that Warner died before seeing his castle demolished. Somehow the destruction of progressive, playful Bancroft seems like a sad metaphor for the soul-crushing rigidity of contemporary American education.

The Mosaic Castle and the Road Not Taken

In high school, I took a course on British literature with a nonconformist teacher who played Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s song “Jerusalem” on a record player when we read the William Blake poem, and had us memorize and recite huge portions of Hamlet. For the Shakespeare unit, we were meant to complete a creative project in addition to a paper. I came up with the idea of making a mosaic of Elsinore, Hamlet’s castle. I figured I could just go to a bathroom supply store, purchase some small tiles, and knock it out in a weekend, but the materials available didn’t match my vision. Somehow my father located a retired Italian glass mosaicist who had worked in Boston-area churches, and convinced him to meet with me to give me some pointers. That encounter turned into a master-pupil relationship that lasted most of my junior year. Almost every weekend my father would drive me to the mosaicist’s house, who painstakingly taught me how to create a cartoon, transfer the image, cut the tiles, and glue them onto a heavy board. The project was supposed to be due in December, and while I told my teacher that I needed an extension, the months slipped by and he failed me on the assignment. Finally, on the last day of school, my father and I drove up with my 2’ x 3’ mosaic of Elsinore in the back of our station wagon and lugged it up to my English teacher’s room on the second floor. He changed my grade to an A+.

Fig. 3: Martha Easton, Elsinore, 1978. Photo: Martha Easton.

For almost 40 years the Elsinore mosaic hung on the wall of my parents’ house, installed with special bolts since it is so heavy. It now languishes in my basement. I still wince a bit every time I see it; a couple of areas are finished with the wrong color since I ran out of time at the very end and had to finish it quickly with the tiles I had left.

Even in the late 70s, the mosaicist bemoaned the fact that mosaic work was a dying skill, and he tried to convince me to become an apprentice. I told him I might be interested, but I wanted to go to college first. Even though I’m sure he is long gone, I wish I could remember his name.

Castle(s) of Love

Near the end of my senior year in high school, a friend gave me a copy of Katherine, written by Anya Seton and published in 1954.[3] It tells a fictionalized version of the true story of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster and fourth son of Edward III. Katherine became the Duke’s mistress and the couple had four children before eventually marrying; their children were legitimized and their descendants included members of the Tudor and Stuart dynasties, as well as members of British royal family today.

Fig. 4: My old copy of Katherine, copyright 1954. Photo: Martha Easton.

I can’t begin to say how much I loved the book. Although she was not a historian, Seton was known for her extensive research, and her ability to weave both fact and fiction into a credible and evocative narrative. Katherine contains vivid accounts of fourteenth-century events, including the Hundred Years War, the Black Death, the Peasants’ Revolt, and the complicated political intrigues of the period. I was especially captivated by the detailed descriptions of medieval architecture, fashion, and cuisine. Very early on in the book, I discovered that Katherine Swynford’s sister Philippa married Geoffrey Chaucer, and he makes a number of appearances in the novel. Katherine had such an impact on me that when I headed off to college a few months later, I selected as my freshman seminar the History course “Chaucer’s England.” Because of that course and that professor (shoutout to Philip Niles, now retired from Carleton College in Northfield, MN), I ended up becoming a History major, focused on the Middle Ages.[4]

And the rest is, well, history. In graduate school I shifted my focus to medieval art instead, but even so my approach to objects is decidedly contextual rather than stylistic.

In all honesty, I hadn’t given the book much thought in decades before reading the CFP for this volume of Different Visions. It sits on a top shelf, gathering dust with all the other works of medieval historical fiction that people tend to give me as presents, although since I’m generally not a fan of the genre (I like to keep my history and my fiction separate), most of them remain unread. I’ve almost never discussed the book with anyone. Every once in a while, someone will ask how I became interested in the Middle Ages, and if I mention Katherine, it’s rare that anyone has heard of it. But if you search for mention of the novel online, it’s a different story. It is clearly a beloved classic, remembered fondly by those who read it as teenagers, as I did, and its rich narrative based in fact is still appreciated by those who have reread it after the space of decades.[5] Other authors known for historical fiction, most notably Philippa Gregory, have been inspired by it.[6] And in recent years, more scholarly studies of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt have been published, first by Jeannette Lucroft (an expansion of her award-winning dissertation) and then by Alison Weir, who both praise the meticulous research Seton did in order to craft her fictionalized account.[7]

Seton filled her nearly 600 pages with historical figures and incidents, but the focus is decidedly on the love story between Katherine and John of Gaunt. Some of the basic facts of their relationship are detailed in contemporary sources, including Froissart’s Chronicles, so we know that Katherine (née de Roët) was the daughter of a knight attached to Queen Philippa of Hainault (wife of Edward III); that she was first married and had children with the knight Hugh Swynford; and that she was brought to court to care for the children of John of Gaunt and his first wife Blanche of Lancaster.[8] Their first spouses died, and John married again, to Constance of Castile (and for a while claimed the throne there). It is not clear when the affair between John and Katherine started; Froissart suggests that it began while Katherine was still married, although it seemed to be important to Seton that she represent Katherine as faithful to her husband until his death.[9] After John’s second wife died, he and Katherine wed in 1396, well over 20 years after their relationship first began. Their children were given the name “Beaufort” and they were legitimized by royal and papal decree. The granddaughter of their eldest son John, Lady Margaret Beaufort, was the mother of Henry VII of England and thus all subsequent English monarchs are descended from the couple.

Fig. 5: John of Gaunt’s Great Hall at Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, England. This was one of 30 castles owned by the Duke, and where the couple often stayed together. Photo: DeFacto, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Seton embellished the basic facts with more titillating and imaginative details. In the novel, despite her desire for the Duke, during a treacherous sea voyage Katherine vows to remain faithful to her marriage, so one of the Duke’s trusted servants poisons her husband. There are numerous scenes of lovemaking, even if they read as a bit sedate. In fact, in an appendix to her book, Alison Weir discusses Seton’s Katherine, and suggests that while the period details are very well realized, in essence Seton imbued the novel with her own viewpoints about sexuality and spirituality, filtered through the moral lens of the 1950s rather than the 1300s.[10]

I decided to reread Katherine for this project, and it remains the page-turner that it was when I first picked it up all those years ago. One of the most exciting passages in the book is Seton’s description of the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt led by Wat Tyler, during which John of Gaunt’s London residence, the Savoy Palace, was reduced to rubble and its contents destroyed. The duke was one of the main targets of the thousands of disaffected people, because in their list of grievances, he in particular was blamed for a devastating new poll tax which only exacerbated the severe economic pressures on the poor. John of Gaunt survived as he was not at the Savoy, but in Seton’s reimagination of the scene, Katherine was there with her daughter and a skeleton staff since most of the retinue had left with the duke.[11]

Seton masterfully mixes the fictional story of Katherine’s chaotic escape with the actual events of the day, describing the crowd running through the castle halls, smashing furniture, ripping down tapestries, pounding jewels into dust, and setting bonfires with the heaped-up debris.

Fig. 6: Pontefract Castle, West Yorkshire, England. This was the possible haven of Katherine Swynford during the Peasants’ Revolt. Photo: Tim Green from Bradford, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

In the novel, Katherine only survives because various men come to her rescue. Seton depicts her as a woman to whom extraordinary things happen, rather than as someone with any particular agency of her own outside the power of her uncommon beauty. Despite the passage of 45 years, I am somewhat chagrined at how well I remember certain scenes that focused on her passive sexual allure, and what an impression they made on me at the time. The first consummation of Katherine and John’s desire for each other takes place in the Château la Teste in Les Landes. When the owner of the castle, lord Captal de Buch, enters their chamber, he sees that

the girl was but half clothed yet so pure was the beauty of her arms and breasts gleaming like alabaster between strands of long auburn hair, and so adoring the expression on the Duke’s face, that the captal saw no lewdness, but felt instead, a bitter stab of nostalgia…[12]

as he remembers a long-ago love of his own who had died. This seemed the height of romance during my initial reading, but I cringe at some of these passages now. On the other hand, Seton’s descriptions of Katherine and her beauty are not so different from the way that women were described in medieval romances, and this may have been Seton’s intention.

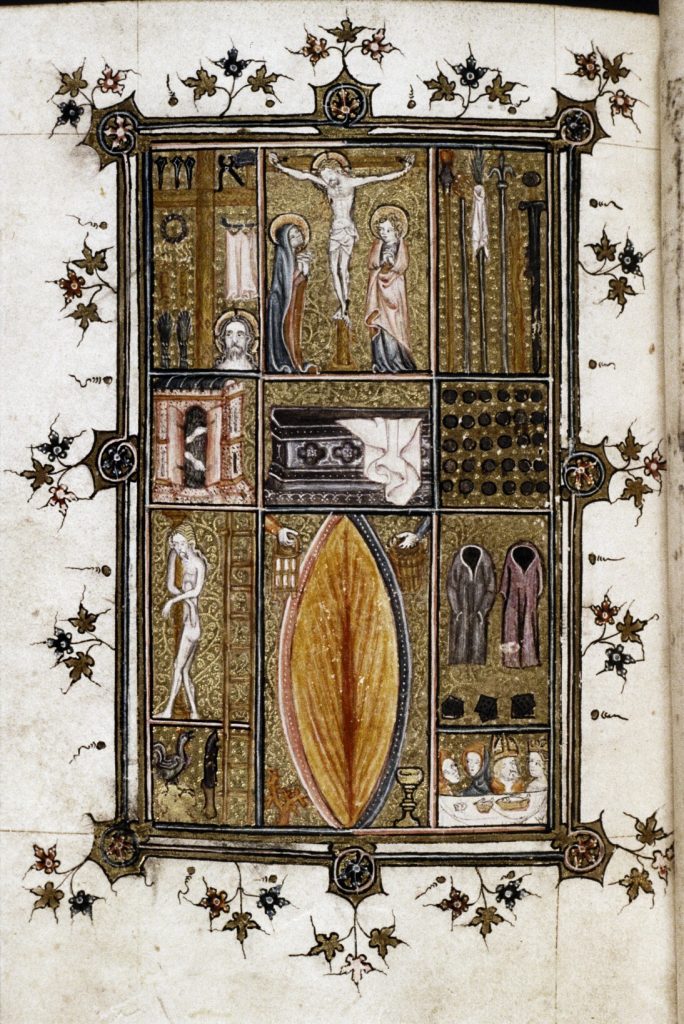

Writing this essay has led me to discover a link between Katherine and my work as an art historian that I didn’t realize I had. In 1387, during a time when Katherine and John of Gaunt were apart, she became a member of the household of Mary de Bohun (1369/60-1394), who had married Henry of Bolingbroke, John’s son with his first wife Blanche. (Henry would eventually usurp the throne from his cousin Richard II to become Henry IV, although this occurred after Mary died.) As scholars of late medieval manuscripts know, between 1350 and 1394 around eleven important manuscripts were made for the Bohun family.[13] Two manuscripts were probably created c. 1380-85 to commemorate the marriage of Henry and Mary; the one that likely belonged to Mary (perhaps started for her father, Humphrey) is now in the Bodleian Library. It is very possible that Katherine would have seen Mary’s psalter and book of hours, complete with a page featuring a series of compartments containing an image of the Crucifixion, along with the Instruments of the Passion. The largest compartment depicts the side wound of Christ, isolated from his body and tipped into a vertical position. Twenty-seven years after I first read Katherine, I published a book chapter on the wound of Christ,[14] although it wasn’t until I read more about Katherine for this piece that I discovered the connection.

Fig. 7: Instruments of the Passion, Psalter/Book of Hours, Use of Sarum (so-called Bohun Psalter and Hours), 1370-80, England, Oxford: Bodleian Library MS. Auct. D. 4. 4, fol. 236v, https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/369c7ccb-4ac4-4b9a-a846-d79889475420/. Photo: © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, CC-BY NC 4.0.

The Castle on the Coast

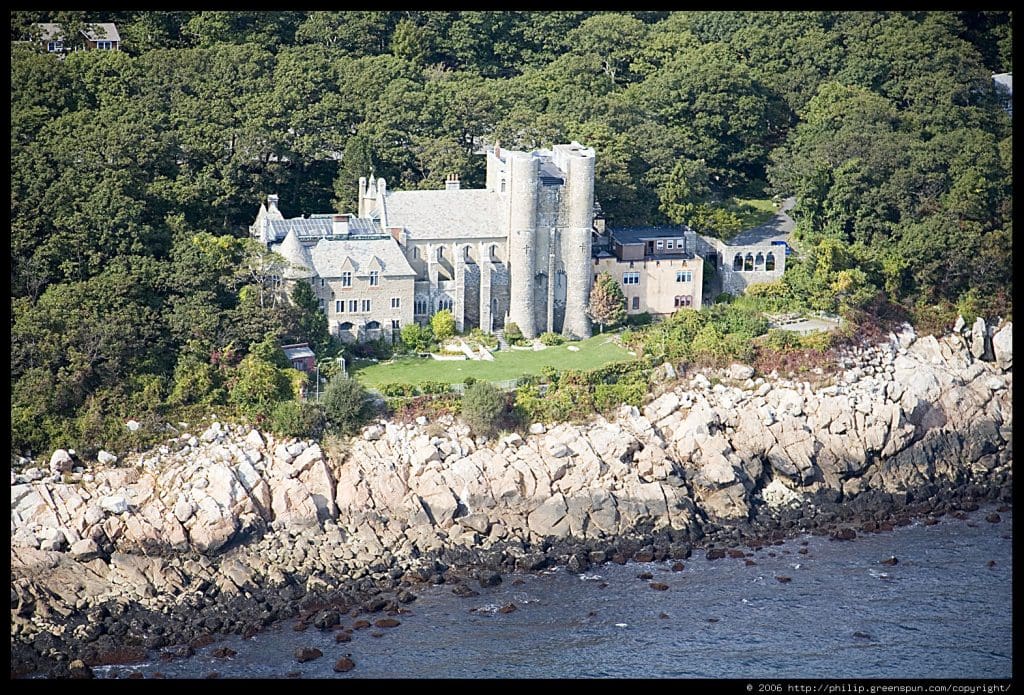

Growing up in Massachusetts with parents interested in history, I visited numerous museums and historic sites. By far my favorite day trip was to Hammond Castle (or Hammond Castle Museum), built between 1926-1929 on the coast of Gloucester, Massachusetts.[15] John Hays Hammond Jr. was a well-known scientist and inventor, with an interest in the history and art of the past that seemingly contradicted his career spent creating the technologies of the future. The building itself is an amalgamation of different architectural styles from both past and present. One end housed the laboratory where he and his staff worked on their cutting-edge projects (radio-controlled weaponry, for one). The rest housed Hammond’s living space, with his collection of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance art and artifacts. As a child, it didn’t really matter to me whether the building was medieval or modern; in truth, I didn’t know the difference. It was enough that it was a castle.

Fig. 8: Hammond Castle, built 1926-29, Gloucester, MA. Photo: Philip Greenspun, 2006 (http://philip.greenspun.com/copyright).

It is a weird and whimsical place. From the outside, one section looks like a castle keep, and another has flying buttresses. There is a drawbridge and a bell tower. Inside, the spaces are small at first, but descending the staircase, visitors emerge into a soaring Great Hall, 100 feet long and 60 feet high. Just beyond there is an interior courtyard with a glassed-in ceiling, with pseudo-Roman columns and medieval house facades surrounding a pool dyed an opaque green, disguising its depth. From the guestbook and photographs we know that Hammond was connected with and visited by the American royalty of politics, finance, and entertainment (John D. Rockefeller Jr.; Helen Clay Frick; Greta Garbo; George Gershwin; and Leopold Stokowski, among many others). There are numerous outrageous stories about life in the castle – some may be true (according to local tradition, Hammond used to dive into the indoor pool from the balcony above), while others are more fanciful (there are several accounts of resident ghosts, and a 2012 episode of Ghost Hunters focused on the castle).

Fig. 9: Great Hall of Hammond Castle, built 1926-29, Gloucester, MA. Photo: Martha Easton.

Fig. 10: Courtyard of Hammond Castle, built 1926-29. Gloucester, MA. Photo: Martha Easton.

Over a decade ago, I decided to explore Hammond Castle as a scholar, and not just as a kid in love with castles. I have now published (in both scholarly journals and in materials for sale in the museum gift shop) a number of things on Hammond Castle, on topics including American medievalism; the authenticity (or lack thereof) of some of the objects; the phenomenological atmosphere that permeates the castle; and the overall ethics of collecting medieval architectural salvage.[16] I’m still not quite sure where this ongoing research is going to end up–hopefully, someday, in a book, although my progress is continually derailed by other projects, and my focus keeps changing as I sift through archival material and think through what exactly it is that I want to say about this complicated, quirky building and collection, and its equally eccentric owner.

In 2013 I wrote an essay for the Material Collective blog about how my personal and professional lives intertwined as this project on Hammond Castle began.[17]

I described a trip that I took there with some medievalist colleagues, including Jennifer Borland, who would be my co-author on the first scholarly article I wrote about the castle a few years after that visit.[18] My father accompanied me; he was born in 1926, the same year the castle started being built, and he remembered it from his own childhood since his own parents typically went to Gloucester for summer vacations. In the essay I suggested that it would probably be the last time I would be able to do such a visit with my father; he was 86 and his declining health and increasing signs of dementia were beginning to take a real toll. As it turns out, I was right, and we lost him in 2017. But every time I return the castle I think of that last visit, and how proud my dad was of me, and how happy he would be that the castle my parents took me to as a child has so profoundly enriched my life.

I have witnessed numerous changes since I started returning to Hammond Castle as an adult. During some of these early visits I was chagrined to see that it had been Disneyfied with pseudo-medieval bric-a-brac. By the time I began my years-long slog through the thousands of uncatalogued documents still housed at the castle, most of the kitsch had been removed, but the museum had also fallen on hard times, with few employees and very light attendance. Fortunately, in recent years the museum has completely rebounded; the wide reach of social media has introduced this relatively unknown local treasure to new audiences, and a far larger staff has renewed the commitment to maintaining the building, expanding the programming, and digitizing the archives.[19] These days the parking lot is always full and the stone walls echo with the happy chatter of engaged tour guides and fascinated visitors. There is no doubt that in this new generation of visitors there will be children who, like me, will fall in love with castles – and perhaps a few of them will go on to be medievalists.

References

| ↑1 | Warner is probably best known for being a 1997 recipient of the Presidential Award for Design Excellence for his work on the reconfiguration of downtown Providence. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Robert Campbell, “Pierce School is an education,” The Boston Globe, September 8, 1974, A7. |

| ↑3 | Anya Seton, Katherine (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1954). |

| ↑4 | If you are reading this footnote, you are getting the privileged information that I actually took the course twice since I had a little bit too much fun during my first term of college. With Phil’s blessing, I decided to take an “F” after I abandoned my initial idea of trying to write five missing papers in a couple of all-nighters. Despite Phil’s initial skepticism, I buckled down and got an “A” the second time around. I went on to take just about every course he offered, and Phil kindly wrote for me for graduate school, despite that less than illustrious start. |

| ↑5 | Sarah Johnson, “Rereading Anya Seton’s Katherine after 35 years,” Reading the past: News, views, and reviews of historical fiction, June 20, 2021, https://readingthepast.blogspot.com/2021/06/rereading-anya-setons-katherine-after.html. |

| ↑6 | Philippa Gregory, “Katherine, by Anya Seton,” March 28, 2013, https://www.philippagregory.com/news/katherine-by-anya-seton. |

| ↑7 | Jeannette Lucroft, Katherine Swynford: The History of a Medieval Mistress (Cheltenham, UK: The History Press, 2006); Alison Weir, Mistress of the Monarchy: The Life of Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (New York: Ballantine Books, 2009). |

| ↑8 | Chaucer is depicted in the novel as being devoted to Blanche, who died in 1368, possibly of the plague. In fact, the central figure “White” in one of his earliest major poems “The Book of the Duchess,” or “The Deth of Blanche,” is purportedly about her, perhaps commissioned by John of Gaunt himself. |

| ↑9 | Froissart, Chronicles, ed. Geoffrey Brereton (New York: Penguin Books, 1968), 418. |

| ↑10 | Weir, 307-09. |

| ↑11 | Weir states that it is unlikely Katherine was in London, and suggests that she hid at Pontrefact Castle in Yorkshire (Weir, 187). |

| ↑12 | Seton, 266. |

| ↑13 | Lucy Freeman Sandler has worked extensively on the Bohun Group of manuscripts. For the catalogue entry on this manuscript, see Gothic Manuscripts 1285-1385: A Survey of Manuscripts Illuminated in the British Isles 5, ed. J.J.G. Alexander (London and Oxford: Harvey Miller Publishers and Oxford University Press, 1986), part II, 157-59, number 138. |

| ↑14 | Martha Easton, “The Wound of Christ, the Mouth of Hell: Appropriations and Inversions of Female Anatomy in the Later Middle Ages,” in Tributes to Jonathan J.G. Alexander: The Making and Meaning of Illuminated Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, Art and Architecture, eds. Susan L’Engle and Gerald B. Guest, (London/Turnhout: Harvey Miller Publishers, 2006), 395-414. |

| ↑15 | For more information on the history and collections of Hammond Castle, see Naomi Reed Kline, The Hammond Museum: A Guidebook (Gloucester, MA, 1977), as well as the catalogue of an exhibition held there (Naomi Reed Kline, Castles: An Enduring Fantasy [Gloucester, MA, 1982]), and subsequent book (Naomi Reed Kline [ed.], Castles: An Enduring Fantasy [New Rochelle, NY, 1985]). An early scholarly account of Hammond Castle is James F. O’Gorman, “Twentieth-Century Gothick: The Hammond Castle Museum in Gloucester and its Antecedents,” Essex Institute Historical Collections 117, no. 2 (1981): 81-104. |

| ↑16 | Martha Easton, “Fabricating the Past at Hammond Castle: Alceo Dosenna, Art Dealers, and Deception,” Journal of the History of Collections 34, no. 2 (2022): 335-50; Martha Easton, “Lost and Found: The Missing Flamboyant Gothic Door from the Château de Varaignes,” Perspectives Médiévales: Revue d’épistémologie des langues et littératures du Moyen Âge 41 (2020), http://journals.openedition.org/peme/21255; Martha Easton, Inventing the Past at Hammond Castle: John Hays Hammond Jr. as Art Collector (Gloucester, MA: Hammond Castle Museum, 2020); John Pettibone with Martha Easton, Tales From Hammond Castle: A History and Anecdotal Recollection, (Gloucester, MA: Hammond Castle Museum, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhab024 |

| ↑17 | Martha Easton, “In Search of Lost Time,” Material Collective (January 2013), http://thematerialcollective.org/in-search-of-lost-time/. |

| ↑18 | Jennifer Borland and Martha Easton, “Integrated Pasts: Glencairn Museum and Hammond Castle,” Gesta 57, no. 1 (2018): 95-118. https://doi.org/10.1086/695775 |

| ↑19 | It has also stopped suppressing information about Hammond’s personal life; a rainbow flag flew on the castle grounds for Pride Month in June 2024, and the museum openly acknowledges Hammond’s relationships with both men and women. |